To: “Daily Princetonian”

By Dr. Jeffrey B. Perry

In 1964 as Princeton freshmen we were told that Woodrow Wilson had been a leading Progressive, a proponent of “Democracy,” and a champion of self-determination abroad. It is good to see students today challenging that picture (“Updated: Students ‘walkout and speakout,’ occupy Nassau Hall until demands of Black Justice League are met,” November 18, 2015).

Wilson’s record was deplorable on the “race question.” He cut back federal appointments of African Americans; supported showings of the white-supremacist film “The Birth of a Nation” for himself, his Cabinet, Congress, and the Supreme Court; stood by silently as segregation was formalized in the Post Office, Treasury, Interior, Bureau of Engraving and Printing, and Navy; did nothing as almost two dozen segregation-supporting legislative attempts including exclusion of Black immigrants, segregation of streetcars, and a ban on inter-racial marriages in the District of Columbia were introduced in the House and Senate; and declined to use any significant power of office to address lynching, segregation, and disfranchisement (which marred the land) and the vicious white-supremacist attacks on twenty-six African American communities including Washington, DC, Chicago, and East St. Louis that occurred during his administration.

Under Wilson the U.S. not only implemented the Espionage Act of 1917, the Sedition Act of 1918, and the Palmer Raids of 1919-1920, it also occupied Haiti, the Dominican Republic, Cuba, and Nicaragua and intervened in Panama, Honduras, and Mexico. Nevertheless, Wilson ran for President in 1916 on a campaign slogan “he kept us out of war,” posed before the world as a champion of democracy, and prated of “the rights of small nationalities,” of “self-determination,” and of “the right of all who submit to authority to have a voice in their own government.” In addition to the awful horrors let loose on small countries pre-war, in the postwar period he also helped to pave the way for partition, occupation, and conquest in the Middle East and Africa and for future wars.

There were contemporaries of Wilson, people like the intellectual/activist Hubert Harrison, the founder of the first organization (the Liberty League) and first newspaper (“The Voice”) of the militant “New Negro Movement,” who saw through the misleading portrait of Wilson so often found in the media and history books. Harrison understood that while lynching, segregation, and disfranchisement marred this land, and while the U.S. brazenly attacked smaller countries, “Wilson’s protestations of democracy were lying protestations, consciously, and deliberately designed to deceive.” At the founding meeting of the Liberty League in June 1917, Harrison posed a direct challenge to Wilson who had claimed the U.S. was entering World War I in order to “Make the World Safe for Democracy.” Harrison’s mass meeting was called, as its organizational flyer headlined, to “Stop Lynching and Disfranchisement in the Land Which We Love and Make the South ‘Safe For Democracy.'” A month later Harrison led a second major Harlem rally to protest the white supremacist “pogrom” (his word) in East St. Louis, Illinois (15 miles from Ferguson, Missouri).

We are glad that the Black Justice League is raising some of these issues, opening the eyes of many, and helping to point the way forward in the 21st century.

___________________________◊◊◊___________________________

THE LEGACY OF SPAIN AND THE LINCOLN BRIGADE

By David Bacon

Speech given at the 79th Annual Celebration of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade in Berkeley, California 11/8/15 by David Bacon

All my life I’ve known about Spain. I grew up singing Freiheit and Viva la Quince Brigada and Los Cuatro Generales, and knew the names of some of the places in Spain where the big battles were fought. I owe a lot to my parents, and to the culture they helped create. They didn’t go to Spain, but they were brave people nonetheless. When Paul Robeson went to sing in Peekskill, my dad was one of the union members from New York City who lined the roads to protect people from the rocks thrown by the fascists of upstate New York. In 1953, the year the Rosenbergs were executed, they brought my brother and me here to Oakland, where I grew up. That’s why I’m an Oakland boy, and not a Brooklyn boy.

When I think about the impact of Spain on my life, I think about the people who went and fought there, and what they taught me. Some of them I knew personally, and some taught me by example. They all taught me about how to conduct a life dedicated, not just to opposing injustice, but to fighting for a different world, for a vision of a just society, a socialist society.

Today I work with California Rural Legal Assistance, as a photographer and a journalist. Growing up in Oakland, I didn’t know much about life in rural California, or who farm workers are and the work they do. But I come from a union family, so when I got back from Cuba in the early 70s, full of revolutionary enthusiasm, the place where I thought I could fight for real change here was the farm workers union. I went to work, learning from people like Eliseo Medina the nuts and bolts of how to organize strikes, win union elections, go on the boycott – the basic toolkit of working class struggle.

There I met Ralph Abascal, who had helped to organize California Rural Legal Assistance. With a nod and a wink, after the lawyers had gone home at the end of the day, our crew of workers and organizers would come in and use the typewriters and xerox machines all night to put together our legal cases against firings and grower dirty tricks. That’s what I loved about CRLA and the way he ran it – it was a part of the workers movement, and its resources were shared. He wanted the union and the workers to fight and survive. It was no surprise to me later to learn that Ralph’s family came from Spain, and that his uncles fought in the Civil War.

I’m not your average photographer. That’s one reason why CRLA and I get along so well, together with our partner in documenting the lives of farm workers, the Frente Indigena de Organizaciones Binacionales. The purpose of our work is to create photographs that are instruments or tools for social change. We document workers living in tents under trees and sleeping in their cars when the harvest comes, in Arvin, Coachella, San Diego and Santa Rosa. But we do more than show abuses. Our photographs show workers acting to change those conditions.

One of my favorite quotes is by Alexander Rodchenko, the famous Soviet photographer of the 1920s and 30s. He said, “Art has no place in modern life,” and that we should “take photographs from every angle but the navel.” What he means, of course, is not just that photographs should have a social purpose, but that the photographer should be part of the movements for social change, for revolution.

The most important photographer who not only shared this idea, but lived her life by it, was Tina Modotti. She had a deep connection with the defense of the Spanish Republic. She was an Italian immigrant, from Udine, but she grew up here, in San Francisco. Today they have festivals in her birth town and a foundation in her name in Italy. Here in the Bay Area, though, we hardly know or speak about her. She grew up in North Beach, wanted to become an actress, and went to Los Angeles where she met Edward Weston. Together they went to Mexico just at the height of the artistic ferment of the 1920s, when the revolution was going strong.

She and Weston developed modernism in photography, but she went a step further. She filled their modernistic style with political and social content. And she did more. She joined the Mexican Communist Party, and helped organise the Union of Painters and Sculptors. She took some of the first photographs of huge political demonstrations, and tried to find a visual language that was simple and could inspire people to act.

And as her political commitment deepened, the Mexican government deported her in 1930 to Germany, and from there she went to the Soviet Union, where she went to work for the Comintern. During that time she stopped taking photographs. That’s one of the things I admire most about her. She said, “I cannot solve the problem of life by losing myself in the problem of art.” There are times when the need to act politically is so important that art has to give way. That’s the opposite of what we’re taught in the corporate culture of today, where “art is everything” – that you can’t let mere social justice get in the way.

When the war came in Spain, she went with her lover, Vittorio Vidali, or as he was know in Spain, Comandante Carlos. Modotti was the organizer for Workers Red Aid, helping to free what prisoners they could, and sustain and keep alive those they couldn’t. She worked with Dr. Norman Bethune. Vidali organized the Fifth Regiment, and today when I hear the words to El Quinto Regimiento, that in the “patio de un convento, el partido comunista (in Oscar Chavez’ version) or el pueblo madrileño (in Rolando Alarcon’s version) formo el quinto regimiento,” I think about Vidali and Modotti.

At the end of the war, Modotti was in charge of helping the streams of refugees that filled the roads along the coast, from Barcelona to the French border, as they fled Franco’s advancing troops. I think about her when I see the roads filled with migrants fleeing the bombing in Syria and Iraq today, trying to find refuge in Europe. If Modotti were alive, she would be there. But she would be the first to say that these desperate people can’t use our pity any more than the Spanish refugees could.

When the vets came back from fighting in Spain and from World War Two, California and the Bay Area were very different politically from what they are today.

Just as we know that the advance of fascism was the root cause of people fleeing Spain, we have to look at the root causes of the flight of migrants today. We have to ask what, or better still, who makes poverty and violence so unbearable that drowning in the Mediterranean seems an acceptable or necessary risk. And of course, it’s not just there. What is causing the poverty and displacement in Honduras or Mexico, that makes migration a necessity for survival? And just as the internment in France that greeted the Spanish refugees was a basic violation of their human rights, and a demeaning humiliation, the Karnes and Hutto detention centers in Texas are a crime against working people that we have to fight today.

After the war Modotti and Vidali separated. Vidali eventually returned to the Free Territory of Trieste, and when it became part of Italy he was elected the Communist deputy from Trieste for many years. Modotti returned to Mexico when Lazaro Cardenas was president, but she was so exhausted she got sick and died. She was never allowed to return to San Francisco, and to her family.

So this lesson of Modotti and Spain is that photography and social change are important and go together, but the most important thing is the objective, which is to fight fascism and change the world.

Spain attracted photographers. We all know the Robert Capa photo of the soldier shot just at the moment when he rises to charge the enemy. Capa made his reputation in Spain. The famous Magnum Photo Agency in New York was organized by photographers who supported, and some who participated, in this huge social upheaval. I did a google search of the VALB archive database, and I found 26 photographers who went to Spain, and that’s not counting the other artists. They didn’t go to take pictures or paint. They went to fight. So Modotti was definitely not the only person who thought this way. But she asked the big question about our role as artists – how to make art serve the cause of social justice, and how to make that the main question – not becoming a celebrity or making lots of money.

When the vets came back from fighting in Spain and from World War Two, California and the Bay Area were very different politically from what they are today. Don Mulford was firing teachers for not signing loyalty oaths. The Knowland family ran Oakland. Sam Yorty ran Los Angeles with Chief Parker running the LAPD, including its notorious Red Squad. The growers in the valley had all the power. They had yet to be challenged by the farmworkers historic strike in 1965, the fiftieth anniversary of which we’re celebrating this year.

In my life as a union organizer, before I started work as a photographer and journalist, I met other people who’d fought in Spain. They were part of the unions and movements where I met them. Henry Giler was blacklisted in those bad old days, and became an air conditioning mechanic, before he went back to law school. Then he became a civil rights lawyer, and defended our strikers when I worked for the United Electrical Workers. We were organizing immigrants at the beginning of the huge upsurge that has changed California’s politics so fundamentally.

I met Coleman Persily, because we were both friends of Bert Corona, the founder of our modern immigrant rights movement. Coleman fought in Spain, and then in the 50s he and Bert helped run the campaign for Edward Roybal, the first Chicano elected to Congress from California since 1879. That was a harbinger of the end of the Yorty years, of the hatred of Latinos seen in the Zoot Suit riots and the Sleepy Lagoon prosecution, and of LA’s reputation as the home of the Open Shop. As we know today, much bigger political changes were to come, and people like Henry and Coleman helped set the stage. Coleman went on to help organize the Canal Street Alliance, which today is Marin County’s main immigrant rights organization.

Through organizing immigrant farm and factory workers, I became an immigrant rights activist and organizer, like them. In those days, it didn’t make you popular, in the labor movement especially, to insist that undocumented workers had rights, and that our unions had to include and fight for them.

Both Henry and Coleman had a vision of justice and equality, which took them to fight in Spain, and which they brought back into the movements here at home. They also brought back a love of the Spanish language and culture, which then became a love for the Mexican people. It’s remarkable how many people came back from Spain and wound up in Mexico itself. Some were like Linni De Vries. She went to Mexico because she was hounded by the FBI, but then loved it so much she become a citizen in 1962. The U.S. government took away her U.S. citizenship a year later.

And then there’s Archie Brown. When I was trying to figure out what it meant to be committed to socialism, and to be a union organizer at the same time, Archie was the person who helped me.

When my youngest daughter was little, her favorite movie was “Newsies” – the musical about the newsboy strike against Pulitzer in New York in 1899. Only later did I learn that Archie too had been a newsie, and helped organize a newsie strike here in Oakland in 1928. Archie became a Red very young, as did many people who went to Spain. He was so visible that the State Department wouldn’t give him a passport, and he had to cross the Atlantic as a stowaway.

His attitude was that laws that violate the political and labor rights of working people have to be challenged directly, legally in court, and politically out in the world.

When I was just becoming politically aware, at 12, Archie got called by the House Unamerican Activities Committee. As he started to speak, refusing to name names, demonstrators, many from the UC campus here, burst into the hearing room and disrupted it. Archie was thrown out. It was the opening of the civil disobedience offensive that eventually led to the students being washed down the marble staircase of San Francisco City Hall. That was the beginning of the end for HUAC.

Archie spent his working and political life in Local 10 of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union. In Archie’s book, the most important political work you could do in a union was to educate rank and file workers, and help them become activists for change, in the union, at work, and in the community around them. When he ran for union office as a Communist, his point was first, to get workers to think about more radical ideas, and second, to challenge the Federal government’s prohibition on electing Communists to union office.

He was successful on both counts, I think. The government indicted him, but the Supreme Court overturned the prohibition. This is important for us to think about. His attitude was that laws that violate the political and labor rights of working people have to be challenged directly, legally in court, and politically out in the world. Today the Supreme Court is about to strike down the laws protecting union membership in contracts for public workers. Archie, running for office deliberately to defy the law, is saying to us, we have to fight.

His other objective was as important. One of the most important reasons why the Bay Area, and the cities of the Pacific Coast, have a radical political tradition is because of the ILWU. But it’s not just the union as an institution. It’s the fact that the union brought together and educated a body of workers who then worked in political campaigns, civil rights demonstrations, school and workplace integration, and a myriad of other social struggles. And creating and maintaining that active membership was the job of the leftwingers in the union.

That’s what Archie believed. Power and leftwing politics in the labor movement comes from the bottom up, not the top down, and only if there is an organized left fighting for it. In my own working life, I tried to use every strike, every plant that closed throwing workers onto the sidewalk, as an opportunity for us to learn about the nature of the society we live in.

Today in our labor movement we have a crisis, in part because we represent a falling percentage of the workforce. We face a political structure, Republican and even Democratic, that is more hostile towards us than any we’ve seen since the 1920s. But the crisis is also a result of our unions’ failure to propose much more radical measures to advance our interests, and to educate our members so they understand why that’s necessary.

I don’t think Archie learned this way of being a working class activist and organizer in Spain. But I think he shared it with the people who went to Spain from the surging working class movement of the mid-1930s. This was their style of work, what made them so effective. After all, they left for Spain within just a year or two of the San Francisco General Strike, the greatest labor upsurge we’ve ever had here. They made the same choice that Tina Modotti did. Defeating fascism in Spain was the overarching need of the working class movement all over the world, more important even than the union itself. The Abraham Lincoln Brigade is the product of that idea – what made international solidarity such a force that we celebrate it today, eighty years later.

And what they all have in common – Tina, Henry, Coleman, Archie, Vittorio Vidali – and I think everyone here – is that we fight for a more just world, not merely against the injustice of this one. This is why the living memory of the Lincoln Brigade is so important.

Sergio Sosa, a Guatemalan migrant who now directs Omaha’s Heartland Workers’ Center, says: “People from Europe and the U.S. crossed our borders to come to Guatemala, and took over our land and economy. Migration is a form of fighting back. Now it’s our turn to cross borders.”

The experiences of workers migrating from country to country for jobs, or fleeing warfare and repression, testify to the impact of free-market economics and the wars they bring about. But at the same time, these migrants are changing profoundly the culture and social movements of the wealthy countries of the global north. They are one reason why we have a greater opportunity to talk about a vision of a society free from exploitation, a socialist society, than we’ve had for twenty years.

The economic inequality and social cost of capitalism haven’t changed – if anything, they’ve become even more exaggerated. The class conflict at the root hasn’t been eliminated by globalization. In fact, it’s been extended and deepened in country after country.

Many people in our movement, at least in the US, see the cost of this system to our people and hate it. We recognize the common interest of many sections of our society in opposing it. Hating capitalism, even by name, has become popular. In my youth, just using the word capitalism was enough to get redbaited and ostrasized. Now we celebrate May Day, thanks to the ourpouring of immigrants, especially from countries where it’s always been celebrated as the workers’ holiday.

The radical vision of those who fought in Spain made the movement here stronger.

But what is the alternative? Can society be managed on the basis of equality? Can economic development provide a full life for all people, not just more efficient commodity production? What is the vision of the future that can bind together a movement of millions of people, which can produce an alternative culture that can last from one generation to the next?

A radical vision runs counter to the prevailing wisdom of our times, which holds the profit motive sacred, and believes that market forces solve all social problems. If we challenge that wisdom, we won’t get invited for coffee with the President. At the beginning of the cold war, the AFL-CIO built its headquarters right down the street from the White House. Maybe it’s time now to move.

For working people to organize by the millions, which is what we have to do, we have to make hard decisions. People must their jobs on the line for the sake of their future. But the unions of past decades, the activists and organizers who went to Spain, won the loyalty of working people when joining was even more dangerous and illegal than it is today. The left then proposed an alternative social vision – that society could be organized to ensure social and economic justice for all people. We were united by the idea that we could gain enough political power to end poverty, unemployment, racism, and discrimination.

Today our biggest problem is finding similar ways to affect consciousness — the way people think. We have to have a much clearer sense that large-scale social change is possible. The radical vision of those who fought in Spain made the movement here stronger. When our movement lost that vision in the red scares of the 1950s, we lost our ability to inspire. It’s no accident that the years of McCarthyism marked the point when the percentage of organized workers began to decline.

Radical ideas have a transformative power – especially the idea that while you might not live to see a new world, your children might, if you fight for it. In the 1930s and 40s, these ideas were propagated within unions by leftwing political organizations. A general radical culture reinforced them. Today we need a core of activists unafraid of radical ideas of social justice, and who can link them to immediate economic bread-and-butter issues. And since good ideas are worthless unless they reach people, we have to be able to communicate that vision to working people as broadly as we can.

We are not at the end of history. We have to reclaim our history, not discard or forget it. Working people have proposed alternatives to capitalism for over a hundred years – socialism, communism, nationalist economic development, and more. Those who went to Spain were fighting for this vision, as much as they were fighting against Franco.

We are told we must allow millions of people to become casualties of the free market, whether as the unemployed, the hungry and powerless, or the victims of war and oppression. It is up to those who say there is an alternative, not only to proclaim it and advocate for it, but to organize the majority of our people to fight for it.

This is the most important legacy of Spain. If there is to be any alternative, it will only exist because those who don’t benefit from the current system fight to bring a new one into being.

___________________________◊◊◊___________________________

Setting the terms of engagement

By John Bowman

Before holding forth on this topic, I should identify myself. As an old-fashioned (and I mean old!) liberal/progressive, my views and general approach on socio-economic/political issues may not be quite as “advanced’ as many of the participants in this forum. Put another way, I may seem like an out-of-date, not to say out-of- touch, compromiser! That said, I am calling everyone’s attention to a longish editorial opinion piece in the Sunday (Nov. 22) New York Times Sunday Review section of Nov. 22: one titled “Who Turned My Blue State Red?”. The writer is an Alex MacGillis, by-lined as a political reporter for Pro-Publico. He writes about the phenomenon now fairly apparent in this country: Increasingly, districts and whole states with populations that are heavily dependent on various government programs (from housing subsidies and food stamps and disability payments to Medicare and Social Security) – in general, favored by Democrats – are electing politicians who do not particularly support them – in general, Republicans. Indeed, he describes some regions and states that are among the greatest beneficiaries of these government programs as now electing Republicans who explicitly campaign AGAINST these very programs. How and why this comes about is what he undertakes to explain: briefly he argues that it is the white population, especially older whites in these regions who may themselves be relying on at least some of these programs. However, they regard themselves as having earned/paid for these benefits and see poorer folks, especially people of color or newer ethnic groups, as freeloaders. And because this latter, relatively large segment of the region’s population does not vote in proportion to their numbers, whites, especially older whites, get to elect Republicans. Although he does not state this, it seems to be implied that this group assume that Republican politicians will in fact retain all programs that benefit themselves [E.g. Social Security, Medicare] but cut back on anything that rewards those “freeloaders” [E.g. food stamps, disability payments]. If nothing else, these people are giving expression to a generalized, “floating” resentment that Republican politicians seem responsive to. That is what lies behind this apparent paradox.

Aside from wishing to call your attention to this thoughtful piece – even if you do not necessarily agree with all of his points – I would like to make my own point. And it is that I feel that Democrat politicians – up to and including Hillary Clinton – and all of us “liberals” should face up to this development in our nation. We should not leave it to Republicans to campaign in this negative way, to make promises about what they will do or not do about these issues when elected. But I would go further – and this is where I may lose some of you – I think that the Democrats, and we liberals/progressives, should admit that there is waste and fraud in these programs and, if elected, they will set about to try to eliminate this.

For starters, there is undoubtedly a top-heavy bureaucracy administering most government programs. There is redundancy, there is inefficiency, incompetency. Every program should have some sort of Ombudsman whose sole duty is to seek out waste and fraud. No need to hire new personnel – rather reassign existent staff to this. It is well known that there are individuals receiving disability payments who are not really deserving. I would be for tracking them down. Thus the Social Security Administration will assign staff and procedures to more closely examine all disability claims. People abuse the food stamps they otherwise deserve. Medicaid and Medicare are rife with fraud, much of which is committed by pharmaceutical companies and upper-income medical practitioners – this is not a campaign just against lower income individuals.

Let me be clear. I accept that the total sums lost in all such instances – that is, involving individuals committing what I’ll lump together as “fraud’ for the moment – would add up to probably far less than what corporations get away with by avoiding taxes. Or what defense contractors get away with by manipulating contracts, not to mention corporations’ own varieties of fraud. And all that, it goes without saying here, should be a major priority of Democrats and progressives. But here’s my point: This other issue should be taken away from the Republicans. We do not need to elect even a “democratic socialist,” let alone some radical third-party candidate to deal with this issue. I know this is perhaps not much more than a cosmetic clean up of our social/economic/political system. But for better or worse we have this two-party system, and I wish the Democrats would take up this particular crusade. Bernie Sanders raving about greed in banking, Hillary carrying on about Wall Street, East Coast liberals questioning hedge funds (“the carried interest loophole”?!): none of this means much to the inhabitants of West Virginia and Kentucky who are voting in Republicans because they see some in their own communities unfairly getting disability checks while still active. Or getting food stamps and yet attending fancy restaurants or expensive sporting events. The Democrats should make it a “populist” issue and provide a reasoned promise to deal with this problem. They might even restore some of those Red states to the Blue column.

___________________________◊◊◊___________________________

Editor’s note:

Related to the NYT’s piece mentioned in this post: The Powder KegThe seething racial resentment of the Obama era is of an altogether different kin, Esquire, 24 November 2015 by Charles Pierce

Why non-profits can’t lead the 99%

By Warren Mar

Warren Mar has written a provocative piece on the role of Community Based Organizations and Worker Centers in the working class movement. He explores controversial issues of the funding and democratic control of these organizations which have filled a vacuum in organizing particularly among immigrant workers.

The author entered community and labor organizing in the late 60’s and early 70’s during the second resurgence of a left alternative to capitalism. Many new left activists entered the labor movement during this time, hoping that American Unions would finally represent the entire working class, and not only those workers under a specific work place contract.

Even at its peak in 1953 the AFL-CIO unions only represented 33% of American workers. This year coincided with continuing legal Jim Crow segregation in the South, excluding African Americans from unions, and years of Asian and Latino exclusion from unions on the West Coast. Therefore the 33% reflected on longingly by union old-timers may have represented a majority of white males concentrated in heavy industry and the skilled construction trades of the Midwest and Northeast. This was the geographic concentration of the majority of union members during the height of the AFL-CIO. Not until the late 60’s and early 70’s when public sector unions were formed and – and public sector civil service jobs were integrated – did large numbers of women and minorities become card-carrying AFL-CIO union members even in the most liberal of northern cities.

The above serves as a context to what we are seeing in liberal urban areas today. Unions, even those that survive, are too insignificant to have a large impact on organizing and popular culture. At 6% density in the private sector, most young workers have no chance of stepping into a union job, so the benefits of union membership is an ideological abstraction. In contrast, many baby boomers were able to step into private sector union jobs, fresh out of high school in the early 1970’s. My first union job allowed me to rent my own apartment, in San Francisco, by making five times the minimum wage. I also had a full medical plan, paid vacation and holidays off, something my immigrant parents never obtained in the era when they were excluded from most unions and specific industries. While I fought against the racism and cronyism of unions I never faltered in my support of them. Even in liberal San Francisco, the difference between a union job vs. a non-union job meant a real living wage. I learned to work union whenever I could right out of high school because it allowed me to pay the rent and later carry the mortgage on my first home in one of the most expensive cities in the United States.

What has stepped into the void with the demise of unions?

It would take another long article to discuss the demise of unions in this country and in particular urban areas. That is not the purpose of this article. Rather, I want to look at the rise of Community Based Organizations (CBO’s), all of whom are chartered as Non-Profit Organizations. They have stepped into the void left by unions as the main and sometimes only organizers of low wage immigrant workers. Some organize workers explicitly through the moniker of being a “workers center”. Many started by representing workers that traditional unions would not touch such as transient immigrant workers who moved from industry to industry or who lacked documentation. The day laborer programs come most readily to mind and they have sprouted up in all urban and agricultural areas where a concentration of Latino or Asian migrants seek casual work, without the benefit of documentation. Others have arisen to redress violations of local progressive workers ordinances such as increases in the minimum wage, paid sick days, private contributions to health care, etc. These progressive policies, usually enacted in left-leaning urban areas, came into being without any enforcement mechanism and when there were written regulations they were remanded to municipal departments woefully understaffed and often with a history of civil service staff lacking the bi-lingual or bi-cultural ability to serve immigrant workers, the most likely victims of non-compliance by intransigent employers.

How have CBO/Non-profits done in representing the most exploited among the working class?

Many progressives and leftists, who did not come from the working class, saw the importance of working in unions in the 60’s and 70’s. Many did so by taking jobs in factories, hospitals or in the service sector, after their tenure as campus activists came to an end. Campus activists who leaned towards socialism saw the need to become workers themselves, “integrating with the masses”, moving into inner city neighborhoods to work and live amongst the working class. They often sacrificed the earning potential of their college cohorts and the high hopes of their middle class parents. Ironically many of their middle class professional ambitions were fulfilled when they rapidly transitioned from the shop floor to positions of paid union staff and full time officials in the inner sanctums of the American labor movement. A number of the top leaders of the union affiliates which led the ascension of John Sweeney and Richard Trumka in the “New Voice Movement” taking over leadership of AFL-CIO in the mid 90’s had entered the union movement in the 70’s fresh out of college. The rapid rise of college educated radicals in the leadership of unions raised many contradictions for those who believed that the working class should and indeed could run their own organizations. This was especially true if one professed an adherence to socialism – where workers were supposedly able to run all of society. In practice, this meant the working class should be able to run their own union, if the goal was to give them power over an entire country.

But the inequalities of capitalism are not so easily overcome. In most of the first unions I was a member of in lower level service work — warehousing, garage work, retail, the phone-company, restaurant and hotel work — many of the workers who came directly from the rank and file spoke English as their second language. Some could not read and write English, many could read only at the primary school level in their native language, the result of class inequalities in their countries of origin. Others had never typed a letter and with the advent of computers they were the least acquainted with these new contraptions. So, while some unions conspired to hire college educated non-workers as a means of controlling their staff, who had no ties to the rank and file other than their staff positions, the harsher reality was that even for the most democratic unions the increasing bureaucratic legal codes and the increasing corporatization of Human Resource Departments in firms coinciding with the formal assault on unions in the 1980’s meant that the ability of rank and file members to rise in staff positions became limited by their formal education. It was easier for unions to have representatives with a college education sit across the table from their equally educated counterparts representing management. Whatever we want to think about working class democracy in a highly industrialized society such as the United States, most people learn how to read, write and compute by attending school. In post-industrial America attending better schools or a better university or college made a big difference.

California, which had the best public post-secondary education system in the United States in my adolescence, reflected the class tiers in the three public higher education systems represented in the Master Plan. Community colleges, started out as trade schools, where some licensed workers (nurses, real estate agents, and accountants) could get better working class jobs or transfer to a Baccalaureate institution. State Colleges (formerly referred to as teacher’s colleges) were the first rung on the professional ladder, emphasizing the training of school teachers, social workers and later middle management in the private sector. Finally the University of California system or their private counter parts like Stanford University trained the elite representatives of the ruling class in the sciences, law and business, including the children of the ruling class.

Today, most professional union staff who do not originate from the shop floor and the core staff of non-profits come from these elite universities, not the first two tiers of community and state colleges. This has widened the contradictions among workers and the staff who purport to represent them. Historically progressive unions have had to deal with the racial divide as working class demographics changed the labor force to a significant number of women and people of color. Today’s non-profits have huge class divides between their staff and member/clients.

The problem is further exacerbated in the non-profit sector because at least in unions the staff and officers are financially accountable to the members. Unions after all are still membership organizations. Union members pay dues for officer and staff salaries. In theory, if not practice this meant that the membership is the highest decision making body and while there have been reams of articles and books written about how unions often try to subvert their membership by fixing elections, general meetings, conventions etc., the point is they still need to hold these gatherings. Sometimes, conventions, elections, and meetings don’t go as planned and radical changes may occur. This means that there is still some structure which allows for working members to wield power in a truly membership based organization. Unfortunately most non-profits today do not have the structural requirements most unions must adhere to. There is little in the way of by-laws governing non-profits, for membership election of leaders and oversite of executive directors and staff.

Many non-profits founded as mass based organizations no longer exist – The example of the Chinese Progressive Association

A mass based organization was the term coined in the 60’s when community based organizations were first formed, mostly in communities of color to fill a void where, most of their working class immigrant members lacked union representation. They also formed to deal with issues that unions considered off limits at the time, such as tenant protections when many communities of color where faced with bull dozers at the height of urban renewal, lack of public services in their communities, and lack of access to jobs both private and public which had the best chance of earning a living wage and moderate working conditions. As an example of this type of mass organization, the Chinese Progressive Association (CPA), which formed in San Francisco in late 1973, existed without outside funding well into the 1980’s. It had a large membership base of several hundred, which was dues driven. But the main source of sustainability was the in-kind contributions of the active membership. There was no paid staff. Rent was paid through weekly Sunday dinners where members and non-members alike gathered and paid a few dollars for the meal. Other contributions came in for movie showings and annual celebrations. Regular storefront hours were kept by retired members who, also helped clean the premises, and performed a wide array of handy-man repairs. More important, all of the organizing campaigns were led through volunteer committees which included direct participation of the affected residents of Chinatown. Longstanding committees included a women’s committee, workers mutual aid committee, tenants committee, youth committee, pro-China support committee and cultural committee. I may have forgotten a few. The committees were led by chairpersons and represented on the steering committee, led by English and Chinese speaking co-chairs. We incorporated a Chinese speaking co-chair to guarantee immigrant representation.

Being membership driven in the early years meant that elections of co-chairs and steering committee members were at times contentious, as were decisions to support other nationalities and engage in support work outside the community. Even on international issues and pro-China work, the membership was often at odds, especially when China entered into a border dispute and war with Vietnam in the late 70’s. None of these issues could be dictated and decided by the leadership without many contentious meetings. In hindsight I think this was a fair price for being membership based. Throughout this period we remained critics of local government and shied away from government based funding.

In San Francisco many public sector unions and skilled private sector craft unions fought affirmative action hiring programs initiated by CBO’s at a time when the demographics and language needs of the city were changing, and the people of African American, Asian, and Latino’s were woefully under-represented in government jobs as we became the numerical majority in the city. Organizers realized that local government was the protector of the status quo and whatever discriminatory policy or services were allotted at the state and national levels usually fell on local government to implement. This was true of dishing out low rent housing, summer jobs for youth, government building contracts, etc. In San Francisco, as in many large urban cities, local government was also the largest employer. CBO’s who wanted a share of good civil service jobs knew local government was the historical arbiter of political cronyism and nepotism.

Post mass base CBO’s: From government challenger to government sub-contractor

During the 1980’s when unions were under major assault and public services started sliding into privatization, CBO’s that survived and thrived underwent two major changes. First they negated their membership base to the back burner, no longer relying on their financial or in-kind contributions, and second, became increasingly reliant on local government funding as the primary sustainer of their organization. The rest is supplanted by corporate donations or foundation grants. They may have a paper membership, but this membership is not empowered to have direct elections or financial oversight. In most non-profits you will be hard pressed to find a governing board that looks like their constituents/clients. Most non- profit boards are made up of professionals and often representatives of private corporations who are major donors. Second, there are few non-profits that are member supported financially with any significant dues base. This has transformed many grass roots CBO’s founded in the 60’s-70’s from local government critic and watchdog to local government sub-contractor.

Many CBO/Worker’s Centers receive the lion share of their funding from liberal foundations. Ironically they are enforcing worker’s rights through donations from the heirs of the wealthy. Today, local government contracts have replaced foundation grants as the largest source of funding for many CBO’s in liberal enclaves such as San Francisco. Workers Centers are the recipients of these contracts because local worker rights ordinances such as living wage ordinances, sick day ordinances and medical care contributions are relatively new local policy initiatives. But the lion’s share of non-profit funding comes not from protecting workers rights but from subsidizing housing for the poor, which has gone through decades of privatization. The majority of money granted to CBO’s originates from municipal government, through housing grants. Non-profit CBO’s receive huge grants to build housing but they have also been given grants as property managers on government owned property that was managed publicly in the past. Ironically in pro-tenant San Francisco, the majority of tenant rights have fallen on groups with direct funding from the Mayor’s Office of Housing (MOH). Sometimes the same group can serve as both landlord and tenant rights advocate, both sides funded by the Mayor’s office. There has been more than one local news article where non-profits have turned on their own tenants. In one of the most audacious examples a non-profit church tried to sell off its low rent housing to a private developer, who wanted to transform these low rent housing apartments to market rate units in rental hungry San Francisco. With government pulling out of its responsibility to serve the poor, non-profits have stepped in as a private sector alternative of choice. This is especially true of housing where, just last year Mayor Ed Lee in San Francisco turned over all formerly HUD federal housing to private non-profits.

Staff and Member Class Divide

Some unions put up barriers for non-rank and file staffers by creating rules against professional staff holding elected office. Some unions liked the separation of staff from rank and filers, because if they fired a college-educated staffer these outsiders could not return to the shop floor to foment dissent against a sitting officer.

The class divide among professional staffers in CBO’s, are even wider than they were inside unions who had staff from mixed backgrounds? Few if any of the non-profit staff and leadership reflect the class background of their member/clients. Today, we would be hard pressed to find an Executive Director of a non-profit, program or lead organizing staff without an elite college education. Even the contradiction of a wide class and educational divide between staff and membership felt by unions is not at play in non-profits, because they don’t have any pressure from an active membership. Most of their funding comes from foundations or now local government contracts. If they have a board of directors, it is usually a self-perpetuating board of like-minded professionals. Like corporate boards in the private sector many CBO/Non-Profit boards share members. There is also an easy transition from staff to board membership. Most non-profit CBOs function under the authority of a strong Executive Director model, where the entire staff is hired by the Executive Director. Many board members also serve at the pleasure; explicitly or implicitly of the Executive Director. So unlike unions there is ultimately no membership to answer to.

This separation of staff, board and member clients has had a chilling effect on the ability to really build a grass roots movement. It definitely has a chilling effect on trying to sustain a movement. Rather mobilization has taken the place of empowerment and organizing. Mass demonstrations have become a prop for media coverage. Turn-out is a lobbying effort to impress city hall. Nowhere is this more evident than in the tenant’s rights work in San Francisco. San Francisco has one of the most stringent rent control ordinances in the country. But to get relief from the local rent board, both tenants and landlords by necessity need to show up with a lawyer. All hearings eventually come before an Administrative Law Judge (ALJ), making any direct participation a fool’s journey. There are now no real tenant unions or collectives although one group still holds the name. A web search of their board will show a preponderance of attorneys. They lobby city hall, sometimes by turning out their tenants/clients whom they manage. Even if the eviction fight is righteous, the tenants are more their clients than the ones empowered to sit down and discuss housing and land use issues with the government or their landlord. Often the CBO-Non-profit groups lobby not only city hall but for-profit developers about whether or not they will support a project. In exchange the developer agrees to a fee which goes into a pot for low income housing which city hall can then transfer to the appropriate non-profit.

San Francisco’s main Non-Profits involved in housing gave up on a demand that housing developers build a percentage of affordable housing on-site long ago. Rather developers can legally not build a single unit of affordable housing in a project for in lieu of fees, which the non-profits are then reasonably confident City Hall will remit to them. This had the effect of re-segregating entire neighborhoods. It also had the effect of allowing non-profits in Chinatown and the Tenderloin to benefit off fees by developers in the Dog Patch/Mission Bay and the South of Market neighborhoods that wanted 100% market rate condos. This gentrification has depopulated African Americans Latinos and Filipinos from these two neighborhoods. It was legal bribery and City Hall and the larger non-profits were happy to play. Much of the current gentrification ravaging the East Side neighborhoods of San Francisco started with these policies hailed by progressives as a victory in extracting monetary concessions from for profit developers.

Conclusion

While unions have often been estranged from their members through undemocratic officials and a technocratic unaccountable staff, the potential of the membership to take back power is inherent in their financial contribution (dues), and their codified right to exercise direct power. These two factors are not in play for a majority of non-profit CBO’s currently working with lower paid workers and immigrants. More troubling is the move from direct fundraising and foundation grants to local government contracts which serve as the back-bone of organizational viability for many non-profits today. This has served to allow local government, like federal and state government before them, to privatize previous government services to the poor, at the same time creating a huge client base for the expanding non-profits. Led by People of Color educated from elite universities, many non-profits can avoid the intentionality of dealing with the class question. It also ties many non-profits to neo-liberal Democrats such as Mayor Ed Lee in San Francisco. They can no longer serve as the watch-dogs and critics of government abuse of low income working class residents. This does not serve grass roots organizing, nor does it train the poor and working class on how they should manage their own institutions and maybe some-day the world. If CBO’s and workers centers want to build a long term grass roots movement, they must be able to sustain themselves with a real membership based on dues and volunteer activism. Most importantly they must cut their umbilical cord of government funding, or they will never be able to challenge the state representatives of the ruling class.

___________________________◊◊◊___________________________

“Labor for Bernie” Network Building New Approach to Union Politics

By Rand Wilson

This piece was originally publish in Social Policy, Fall 2015

Labor for Bernie was initiated in June 2015 by trade unionists who have worked closely with Senator Sanders for many years. The network now includes thousands of elected officers, shop stewards, organizers, and rank-and-file members from 50 states and all of the national labor organizations as well as many independent unions.

These labor activists signed an on-line statement embracing Sanders as the only declared candidate, in either major party, “who challenges the billionaires who are trying to steal our pensions, our jobs, our homes, and what’s left of our democracy.” The first 5,000 union supporters may be viewed on the Labor for Bernie website.

More than a quarter of these Sanders supporters belong to building trades’ unions, (with more than 1,000 coming from the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers alone). Members of other unions who have showed significant membership support for Sanders’ presidential campaign include the Communications Workers of America, American Federation of Teachers, the National Education Association, Service Employees International Union, International Union of Operating Engineers, United Auto Workers, and International Brotherhood of Teamsters.

Of course, social media has played a major role in helping to quickly build a strong grassroots network. The Labor for Bernie Facebook page has more than 10,000 “likes” with daily posts frequently reaching over 100,000 people.

The national AFL-CIO’s decision not to make an early endorsement in late July was a reflection of the then surging union support for Sanders’ bid for President. An important early victory for Labor for Bernie! That delay created more space for national affiliates and local unions to support Bernie. Sanders soon won support from the energetic National Nurses United and picked up endorsements from many local unions, including unions like Iron Workers Local 7 and IBEW Local 2222 where members have had previous experience with his strong commitment to workers’ rights.

Larry Cohen, past president of the Communications Workers of America and now a volunteer working on the Sanders campaign said, “Our strong and growing grassroots movement shows that workers are fed up with business as usual. This campaign is about building new power at the grassroots to put a stop to the corporate assault on working families.”

When the American Federation of Teachers national executive board voted to endorse Clinton with little membership input in July, the endorsement caused a huge uproar on social media and led to a major spike in sign-ups by teachers on the Labor for Bernie website. Today, more than 1,000 members of the AFT or the larger NEA have joined the network. Similarly, when the Machinists Union made a Clinton endorsement there was a strong membership reaction.

“The IAM is a great union and I am very proud to be a member, but the leaders went about this endorsement the wrong way,” said Al Wagner a Local 701 journeyman auto tech out of Chicago. “I cannot describe how disappointed I am with the IAM endorsing Hillary. Bernie Sanders is clearly the “pro Labor” and pro middle class choice who can’t be bought by big business.”

The top-down and premature endorsements by AFT and IAM spurred members of Labor for Bernie to make support for Sanders even more visible. By networking the large number of signups by union, Labor for Bernie organizers have encouraged members to begin grassroots campaigns within their unions to generate pressure on leaders for “no endorsement” and/or for “broad membership debate and discussion about the candidates and their stands on the key issues for working families.”

After a broad internal effort within the IBEW, new International President Lonnie Stephenson replied to members who emailed him, “In recent years, the IBEW International Office has made a practice of not endorsing a presidential candidate early in the primary process. We do not intend to do so this year…I encourage all IBEW members to study each candidate’s positions on the issues and to get involved in their local union’s grassroots political efforts.”

A similar effort supported by Labor for Bernie is ongoing to convince the SEIU International Executive Board not to make an early endorsement.

Bernie’s long track record has given his campaign great credibility with union members.

“Telephone workers in New England know Bernie well because he has walked our picket lines and supported our organizing efforts for years,” said Don Trementozzi, president of CWA Local 1400, based in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. “In our union’s recent campaign against the Trans-Pacific Partnership, Bernie was not on the fence—he was helping us lead the fight against a job-killing trade bill backed by Democrats and Republicans alike.”

“Bernie is running on a record of real accomplishment for workers, farmers, veterans, and millions of other blue-collar Americans,” said Erin McKee, President of the South Carolina AFL-CIO. “But here’s the real difference between him and all the rest: he’s the candidate who truly believes in the power of grassroots organizing. Bernie has been to South Carolina over the past few years and some of our members got the chance to see that first hand when he met not only with labor unions but with the fast food workers fighting for $15 an hour and a union.”

“I think everyone is just sick and tired of hearing promises from politicians who say they’ll fight 100 percent for people but then act for Wall Street,” said Mari Cordes, an RN from the University of Vermont Medical Center and Vice President of Healthcare for AFT-Vermont. “Bernie Sanders has never strayed from his working class roots. Not only has he been true to his word in Vermont for the last 35 years, he has rallied real hope across the country—as a four-term mayor, eight-term Congressman, and now two-term U.S. Senator. I stand strong for Bernie for President in 2016.”

“Bernie has a long track record of supporting workers and their right to unionize,” said John Murphy, a Carpenter’s Local 40 steward from Lowell, Mass. “Just recently he was standing with Fair Point workers on their picket lines and offering them aid and support. When members ask me if Bernie can win, I tell them, that’s up to us!”

Union members across the country were out in force on Labor Day promoting Bernie Sanders’ campaign for president and his vision of putting people before profits.

At Labor Day union gatherings, supporters passed out “Why Workers Support Bernie” flyers, held signs, marched in parades, and signed up hundreds of more members to be part of the grassroots “political revolution.”

“By showing the depth of grassroots support for Bernie, we hope more local and national labor leaders will seriously consider his candidacy,” added Cohen who barnstormed for Bernie at Labor Day events in eastern Iowa.

Already tens of thousands of union members have embraced a call for “political revolution” and the “socialist” ideas that Bernie is making the cornerstone of his campaign. They are also implicitly challenging the legacy of “blank check” support from many unions for corporate Democrats who have not stood with the working class on the key issues of our time. They want to elect new leaders who can’t be bought by Wall Street or the billionaire class of “One Percenters.”

Whether or not Bernie gains the Democratic nomination and/or wins the presidency, the challenge will be to create new political structures in the labor movement – perhaps even a new party – capable of continuing the “political revolution” in contests for elected office in tens of thousands of municipal and state level races. If that is the legacy of the Sanders’ campaign, we will owe him a debt of gratitude for many years to come!

Labor for Bernie 2016 is a volunteer effort neither funded nor directed by the Sanders for President campaign. To join this grassroots mobilization, download useful organizing materials, or learn more about Bernie’s past and present support for workers and their unions, go to: Labor for Bernie.

___________________________◊◊◊___________________________

Book Review: The Primary Route: How the 99% Take on the Military Industrial Complex by Tom Gallagher Coast to Coast Publications

By Peter Olney

Democratic socialist, longtime political activist and past Massachusetts state legislator, Tom Gallagher has written a stunningly clear and concise book about American politics. It is self-published and he calls it a “pamphlet” in the tradition of George Orwell, “It is written because there is something that one wants to say now, and because one believes that there is no other way of getting a hearing”(1). Tom Paine wrote a pamphlet called “Common Sense” that inspired the American Revolution. Let’s hope that Gallagher’s common sense manifesto will inspire some clear thinking on the American left.

“The Primary Route” is both prescient about the Sanders candidacy and predictive of some of the benefits of that campaign and the reaction of the political establishment.

As a member in the 1970’s of one of the groups that Gallagher characterizes as “the various revolutionary parties structured for operating in a czarist dictatorship” I found Gallagher’s arguments resonating exactly with my own present perspective on the need for a viable American political strategy. We have all grown up a little, but fortunately maintained our desire for global change.

This is an easy read, 187 pages with great photos and tons of wry humor. Gallagher shrewdly puts the prologue in the back so that his own personal political history doesn’t prejudice you against his argument. “He supported who for President..;;???!!!” There is no peeking, please start from page 1. The subtitle of Chapter 1 is “To be or not to be? The American Left’s Hamlet complex.” The first sentence clearly states the thesis of the pamphlet: “This book is all about a simple argument that a group of people that I’m rather generically calling the American left absolutely has to figure out how to work its way into presidential politics if it is to be taken seriously” I couldn’t agree more, and Gallagher lays out the primary route, the Democratic primary as a way for the Left to be active in the biggest most spotlighted arena of American politics.

Gallagher argues that the “primary route” is an additive rather than a subtractive process: participation in the primary adds to the power of the Left and does not subtract its power electorally as a third party effort potentially does in helping to elect a candidate further from the interests of the supporters of the third party. In making his argument he details the history of third parties back to the 1800’s and tells us the story of the origins of the modern primary system, ironically in the year 1912 when the Socialist Eugene Debs got over 6% of the vote. He tells us the recent history of an independent Green Party effort by Ralph Nader and the Democratic primary efforts by Jesse Jackson and Dennis Kucinich. He even mentions the forgotten entrant in the 1992 primaries, the Mayor of Irvine California, Larry Agran. I remember Larry because I negotiated two labor agreements for the public employees of Irvine in the 80’s and because Larry was dramatically arrested for showing up at the Democratic primary debate that had excluded him.

There is a fascinating chapter that compares our electoral system to other countries in the world where third parties have been more viable, notably Germany. Here is the history of the Greens die Grünen and the Left party, Die Linke. I asked the author for permission to use unpublished chapters with my friends and comrades in the left to encourage them to engage in the Democratic primaries so that there would be a challenge to the corporate candidate, Hillary Clinton. Gallagher said wait for the book as he was seeking a publisher. No publisher ever picked up the book and by the time the book emerged, Bernie Sanders had announced.

Gallagher is almost prophetic. Over and over again his advice and analysis presages phenomena we are witnessing now because of the “Feel the Bern” candidacy. Post October 13 debate we were told by the NYT and other pundit paper and media outlets of the status quo that Hillary won the debate even though polls and focus groups resoundingly supported Bernie. Here is Gallagher: “On the conceptual level, the argument will be made that the more intense the ideological gauntlet we force the presidential candidate to run in the nominating process, the more we threaten the viability of the ultimate nominees in the final election. Implicit in this is the argument that we will be better off simply accepting the candidates that recognized “opinion leaders” present us with.”

The question about Bernie and any primary route challenges is what is left behind? How do we build on the excitement and momentum and grow it and sustain it? Here is Gallagher on “Beyond”: “Eventually we could imagine or at least hope, that if presidential candidates of the left were ever to become a routine and expected thing, the ad hoc, self-selecting aspect of the current nominating process might come to be seen as insufficiently democratic. We might envision a desire for something of a more participatory candidate selection process down the road, perhaps some form of organization that could maintain a measure of continuity from one presidential cycle to the next.” Gallagher does not preclude action on the local state and regional level, he just suggests and the Sanders campaign confirms the importance of entering the big tent and putting socialist ideas on the front burner.

The Primary Rout is a pamphlet that Antonio Gramsci would have been proud of, a simple articulate and humorous discourse that challenges status quo and “common sense” (usually ultra left) thinking on the American left.

I hope that we can drive sales so that a publisher picks this up and disseminates it throughout the country as part of Bernie mania.

Gallagher can be reached at TGTGTGTGTG@aol.com.

___________________________◊◊◊___________________________

(1) George Orwell, Introduction to the British Pamphleteers Vol. I

Olney Odyssey # 16 Sintered Metals, Softball and Somoza

By Peter Olney

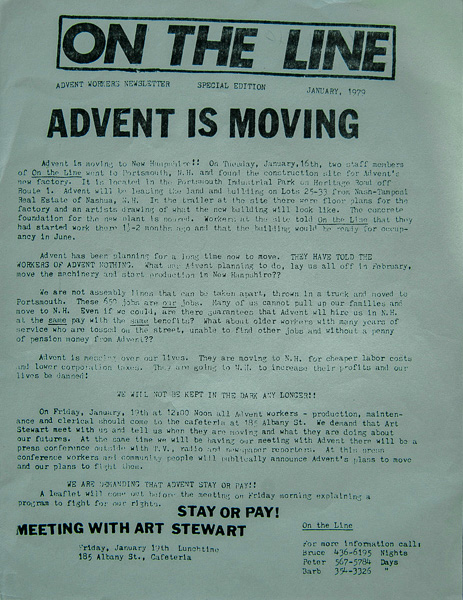

In mid January of 1979 as the Advent battle publicly heated up I took a job at a metal parts manufacturer in Jamaica Plain (JP) called Sintered Metals Inc. I had been laid off by Advent in November of 1978 and had lived on unemployment and the adrenaline rush of the organizing. Now it was clear the plant was closing, and I had located a job at SMI, which was on Washington Street at the old Green Street stop on the then elevated Orange Line of the “T”. I could walk to work because my apartment was on Williams Street near Doyle’s Cafe, the famous JP watering hole featured in the movie, Mystic River.

What do 2 years of college in history and literature have to do with reading mikes, indicators or verniers?”

I was assigned to the third shift, 11 P.M. -7 A.M. I was a press operator running a machine similar to my press at Mass Machine except that this operation was not cutting pieces out of sheet metal. Sintering refers to a work process in metallurgy in which fine powdered metal particles are pressed together in the shape of a part, then sintered or hardened at high temperatures in an industrial oven. (Details here) It is an obvious advance over the laborious process of machining individual parts and has become quite common in the industrial world. The part I remember us making night after long night was the metal casing for a Zippo cigarette lighter (here and here). In 1979 there was talk in the plant that giant pressed metal operations would soon be making even automobile engine blocks, but I don’t think that ever came to pass because of the intense strength requirements. However sintering can be considered a precursor of 3-D printing/fabricating, which appears on its way to replace many traditional fabricating methods and applications.

I was interested in the production process but not stimulated enough to stay awake on the graveyard shift. I tried to combat my drowsiness with smoking and coffee. That didn’t work so I decided that the mental stimulation of crossword puzzles would help. Puzzles run in our family. My mother still does the NY Times puzzle from Monday through Sunday in lightning speed without Google search aids. She has even designed crosswords for magazines and makes up Acrostics for her nieces and nephews as birthday gifts.

I never really acclimated to the night hours. Some workers really like them and certainly getting off work on Friday at 7 AM gets the weekend going early, but my biological clock just never let me sleep in the day (here).

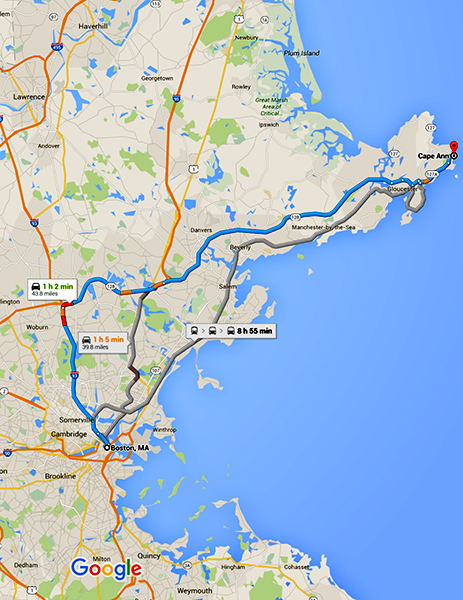

SMI was a family owned company founded in 1943. Myron “Mike” Jaffe was the owner. There weren’t more that 75 employees in production and maintenance in JP. The company had acquired another pressed metals firm in Gloucester called Sinterbond in 1978 and renamed it SMI North. They had the higher tonnage presses and JP handled the lighter work. We in JP were SMI South and the factory was a two-story brick building with 30,000 square feet of production space. In 1977 the workers in the South had voted on union representation with the United Steelworkers (USW) (here and here) and lost by 6 votes.

I had not heard of that union drive before starting at SMI, but I was there to organize. I soon found a soul mate in Normand Brown, a young worker about my age, who was a fluent Spanish speaker from Long Island who had spent time in Cuba. He was a Mechanical Inspector on the second shift, but soon after I got there he moved to third shift. We bonded immediately and started talking about bringing in the USW. The Company handed us a couple of issues. On February 20, 1979 they posted an opening for another Mechanical Inspector. This was a job that they had already posted to the outside public in the pages of the Boston Globe. Finding no takers at their poverty wages, they decided to bring the posting in house. Just the reverse of any decent union job bidding system that provides that incumbents get first crack. Ten of us applied on the third shift. The company offered me the job because of my two years of college. They passed over the applications of more senior and experienced workers in favor of the Liberal Arts college dropout. As I told the personnel manager when I refused the job, “What do 2 years of college in history and literature have to do with reading mikes, indicators or verniers?” The company failed to offer the job to any of the other ten employees. The issue of job postings was a sore point.

On April 26, 1979 the company gave a measly profit sharing check. No raise, just a bonus. Normand calculated that in order for our wages to keep pace with inflation we needed a 10% increase. I was being paid $3.40 per hour, (Minimum wage for all covered, nonexempt workers in 1979 was: $2.90. US Department of Labor) which even at the time was way below the average US manufacturing wage of $5.63. These were the issues that we decided we would campaign on. We started a newsletter called the P/M Worker. The first issue came out in May of 1979 with a blaring headline: “Bonus is Bogus-Cash on the Line in ’79”. Normand did an excellent translation of the 5 legal sized pages into Spanish and we started after shift meetings with workers at Doyle’s Cafe.

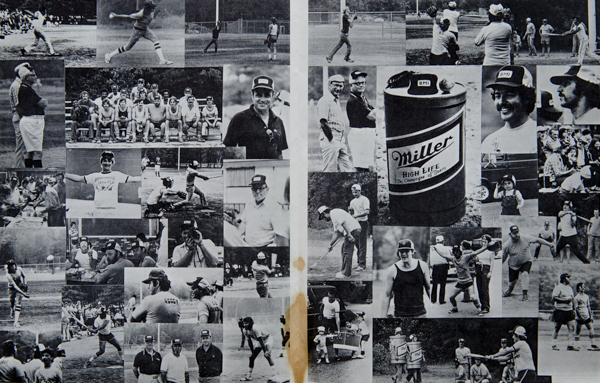

We soon realized the obvious that we needed unity with the workers in Gloucester or unionization would be foolhardy because production could be readily shifted in the event of a job action or prolonged strike. There was no SMInc North Facebook page and no cell phones so we needed a way to meet the Gloucester workers up on Cape Ann, 40 miles away. Sports again came to the rescue of the working class organizer! Normand and I had heard that Gloucester had an industrial league softball team. In fact we heard that they were pretty good, and that they had a player named Kevin Goodhue who had had a tryout with the NY Yankees in the spring. Normand was a decent shortstop, and I had played first base until I was 15 and then switched to lacrosse. We decide the best way to fraternize with Gloucester was to challenge them to a softball game.

We assembled a team from SMI South, a multinational group of white, Black and Puerto Rican players to challenge the self described Gloucester Guzzlers. We called ourselves the Supremos or Boston’s Supreme Team, and we practiced in Franklin Park up the street from the plant. The game was played as part of what became a larger company picnic at Ross Park in Peabody on Sunday, July 15th. The owner of the company Mike Jaffe decided that he was going to umpire the game. This proved to be a fateful and interesting decision.

In mid June the company had disciplined me for wrecking parts and a die worth upwards of $1500. I admitted fault but protested that the punishment did not fit the crime as I had investigated how similar offenses had been handled in the past. No one had been disciplined. I issued a denunciation of the discipline as a slam on the union and an unfair labor practice. The owner responded with a letter laying out a whole list of my offenses including that of doing crosswords on the job. He argued that I was not telling the truth and linked it to my leadership role in trying to bring in the union. The implication was that Olney is lying about his work, and will lie to get you to join the union. So by the time we got to softball in July, Jaffe knew who I was and why I was at SMInc.

Back to softball. Gloucester had a far superior team and Kevin Goodhue, the Yankee prospect, hit several towering home runs out of the park, which in softball is not an easy feat. We were down by eleven runs very quickly. We only scored once in the first 4 innings while North piled it on. Then in the top of the 5th we staged a rally. Six runs came in, and I hit a double to drive in three more. I was the potential tying run on second when my buddy Normand singled to right, and I came around third to try and score even though I knew Kevin Goodhue had a rocket of an arm in right. I slid into home plate ahead of the throw, but I had violated a no sliding rule that had been explained before the game to both teams. So I beat the throw but I should have been called out. What would Jaffe, the owner and the home plate umpire rule? Maybe he thought I would run to the National Labor Relations Board if he ruled me out so after some hesitation he signaled safe with his hands held out flat. The Gloucester side was outraged as lowly Boston had tied the score. If we couldn’t agitate them about pay and benefits maybe we could get them to unionize over the owner’s blown call??!! But they scored one more run in their half and ended up winning 12-11 so their honor was preserved.

We did meet and talk union issues with some of the Gloucester guys but they seemed far more satisfied than their Boston brethren. The following month I got a chance to move to Boston City Hospital and become once again an elevator operator. When it came time to get a letter of recommendation from Charlie Gilman the SMInc personnel manager, he wrote a most bizarre letter of reference. In his final paragraph, he said, “I recommend Peter Olney for whatever job he thinks he is qualified for”. Something to be said for union activism and trouble making when it is time to go.

I have since lost touch with Normand Brown although I believe he ended up being a union leader with the International Association of Machinists (IAM). I’ll never forget the hot humid night of Tuesday, July 17th when he introduced me to the Sandinistas and the Nicaraguan revolution that would so much dominate the Reagan years and our activism as anti-imperialists. Norman came running up to me on the night shift to announce jubilantly that, “The Sandinistas have taken over. Anastasio Somoza is gone”. Before that moment I didn’t know who Somoza or the Sandinistas were and where Nicaragua was located. Worcester was West to me.

___________________________◊◊◊___________________________

Next: Boston City Hospital: Going Up!

Mexico’s Energy Reform: National Coffers, Local Consequences

By Myrna Santiago

This article originally ran in ReVista the Harvard Review of Latin America Fall 2015

… as the men and women felt comfortable and before the temperature in the classroom reached sauna stage, the tone changed…”

The small, white-washed classroom at the University in Minatitlán, Veracruz, was packed with people who, although neighbors, had never met. They included members of a fishing cooperative, a pediatrician, a toxicologist from Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex), a biologist turned environmental activist, a couple of retired oil workers, a Pemex engineer, two medical students, neighbors of the local refinery, and community activists. They squeezed around tables set up with tiny voice recorders at the invitation of my colleague, the historian Christopher Sellers from Stony Brook University, who organized a witness seminar for a project on relations between Pemex and surrounding communities. I was in a supporting role, helping to manage the meeting and translate if necessary. I was also thrilled to visit for the first time Minatitlán and its twin down the road, the Port of Coatzacoalcos, the hubs of the oil and petrochemical industry in southern Veracruz and two of the most polluted cities in Mexico.