Anthem to Courage, Antidote to Nativism!

By Peter Olney

Dreams Deported: Immigrant Youth and Families Resist Deportation

UCLA Center for Labor Research and Education, Los Angeles, California is the third book in a series on immigration and the immigrant youth movement

Leave it to Mexicans to find humor in the most tragic and oppressive moments. The “Pelucon Trompudo” has become the nickname for Donald Trump in the wake of his insults directed at Mexicans. Literally translated it is the long nose snout with a wig! In other words a “pig with a wig”! The pollsters and pundits say his remarks resonate with a segment of American society tired of political correctness. But it is a deep-seated fear of the Other that drives this dehumanization of fellow beings. What is an antidote for this narrowness that finds full flower in vile racism and resentment? In my years of organizing breaking down prejudice and distrust is a matter of working together and/or engaging in struggle against a common enemy. Sometimes though stories of tragedy and pathos can open hearts. The recent shooting in Charleston, SC in a black church during Bible study and the dignified and magnanimous response of the victims’ families seems to have rocked the prejudices of many white people and led to the removal of the Confederate flag. This important new book from the UCLA Labor Center is an appeal to the American public’s sense of decency, humanity and fair play.

Dreams Deported: Immigrant Youth and Families Resist Deportation is a new publication from the UCLA Center for Labor research and Education, known as the UCLA Labor Center. Edited by Kent Wong and Nancy Guaneros, Dreams Deported is the third in a series of powerful books that highlight the travails of immigrant students and their families. The cover is a striking photo of Renata Teodoro, a Brazilian immigrant tearfully reaching through the fence at the US Mexican border to embrace her deported mother. Although the personal accounts are largely of Mexican immigrant youth and families there are also tales of Peruvian, Bolivians, Indians and Armenians. One common thread is the horrible plight of families broken up and forcibly separated by immigration status. Another is the deliberate public action of courageous undocumented young people who refuse to remain in the shadows.

One chapter tells the story of Ju Hong, a Korean immigrant, who interrupted a speech by President Obama before Thanksgiving 2013, in San Francisco. He shouted:

“I need your help, Mr. President. Our families are separated on Thanksgiving. There are thousands of people, undocumented immigrants, families that are being torn apart every single day. Please use your executive order to halt the deportations for all 11.5 million undocumented immigrants right now.”

Obama in that moment continued to claim that he did not have the executive authority to stop deportations although he had instituted Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) and soon after would institute Deferred Action for Parents of Americans (DAPA). DAPA and an expanded DACA were both enjoined in February 2015 by South Texas Federal District Court Judge Andrew Hanen, an uber Republican.

Dreams Deported: Immigrant Youth and Families Resist Deportation will not persuade the vicious Pelucones Trumpados of this world to soften their views of immigrants, but for the vast majority of fair minded Americans this book is a testament to the human spirit and a call for radical immigration reform that preserves family unity.

No review of Dreams Deported can fail to mention the leading role of the UCLA Labor Center in fighting for justice for immigrant youth. The Center has served as a launching pad for the Dreamers movement and deserves tremendous credit for being out front on these issues.

There is also a music video by Aloe Blacc a Grammy nominated recording artist entitled “Wake Me Up”. The video features Hareth Andrade one of the immigrant youth featured in the book.

Dreams Deported: Immigrant Youth and Families Resist Deportation can be purchase here through the UCLA Labor Center

Strawberry Jam

By Frank Bardacke

“In the strawberries, one dies alone.”

In April, 1993 Cesar Chavez died. In October, 1995, John Sweeney became the President of the AFL-CIO. Although the Arturo Rodriguez-led UFW was a minor supporter of Sweeney at the convention that elected him, nothing connected Cesar’s death to Sweeney’s election. But without the conjunction of those two events, there would have been no UFW/AFL-CIO strawberry campaign. Its very existence was rooted in happenstance. That should not surprise anyone interested in politics. Machiavelli claimed that half of politics was luck, or as he called it, fortuna. In the case of the strawberry campaign, at first it seemed like good luck, but by the end, for those who hoped for UFW and AFL-CIO renewal, it was surely bad.

In her eulogy at Cesar’s funeral, Dolores Huerta declared that Cesar died so that the UFW might live. It is a dubious claim—there is no indication of a Chavez suicide—but her meaning was not lost on many of the mourners. Under Cesar’s direction, the UFW had backed off organizing farm workers in the late 1970s and early 1980s, had lost most of its contracts by the mid-80s, and was, at the time of his death, no longer a force in the fields but rather a cross between a farm worker advocacy group and a mid-sized family business. As long as Chavez was alive that was not likely to change. Once he was gone, the UFW was free to make an effort to get back in the fields again.

They began, as they had to, by trying to improve their reputation among undocumented workers. Originally a union of mostly Mexican-American grape pickers, they had officially opposed “illegals” in the fields before 1975, championing the use of the Border Patrol against them and even setting up their own patrol on the Arizona border for a few months in 1974. That policy changed in 1975 with the passage of the California Agricultural Labor Relations Act (ALRA), which made all farm workers, including the undocumented, eligible to vote in farm worker elections. But the changed policy never completely undid the original damage, and since the leadership of the union in the early 1990s continued to be Mexican-American and there were, by then, few Mexican farm workers left in the union, the UFW was considered by many farm workers, a “pocho” (slang used by Mexicans to describe Mexican-Americans) organization.

Thus, the UFW’s first step back into the fields was to take a leadership role against Proposition 187, the 1994 California initiative that denied State benefits to the undocumented and their children. Having made their new sympathy for the undocumented clear, the union won a new contract in the Central Valley roses, fought a victorious campaign in the mushrooms, and even signed a vegetable contract with their old nemesis, Bruce Church Inc. (although on close inspection the contract seemed to cover only a small percentage of Bruce Church workers). In 1995, the UFW leadership was lathered up, in the starting gate, and ready to race.

John Sweeney was also ready to go. Having won the AFL-CIO presidency with a rousing pledge to replace the conservative ways of the old bureaucracy with a new aggressive campaign to organize the unorganized, he was looking for an easy early victory. The UFW seemed to promise one. Relying on Rodriguez’s account of UFW popularity in the fields, and with no alternative assessment available, he went all in, put other organizing on hold, and committed his troops to what promised to be an opening victory for the New Voice coalition. As Gilbert Mireles, author of a pretty good (but also the only) book on the campaign, puts it: “It was almost inconceivable [to the strategists at the top] that workers would not be in favor of the union.”

The Not So Hot Shop

Working in the strawberries is not easy, even by farm worker standards. It is not only that people are bent over all day, or down on their knees, or squatting on their haunches. A lot of farm work is like that, and it makes people old in a hurry, and sooner or later ruins most backs. But what makes strawberry picking especially difficult is that people are paid individually according to how much they pick, rather than by the hour or collectively according to how much the whole crew picks. “En la fresa uno muere solo”, a friend of mine once told me, “in the strawberries, one dies alone.” My friend, a celery cutter who worked alongside his wife in the strawberries every year before the celery season began, was contrasting the work of a berry crew with the work of a piece rate vegetable crew. In the vegetables the crew is paid for every box it cuts and packs, and the workers divide the pay equally among themselves. Their work is a joint, collective effort. The crews are well organized, and stay together for years. These crews, known for their intense internal solidarity, were the heart of UFW strength in the 1970s. In contrast the strawberry crews are barely crews at all, as it is every picker for her or himself, and often there is competition over who gets the good rows. Primarily as a consequence of this relative lack of internal solidarity in the structure of the crews, the UFW, even at its height, could never maintain contracts among strawberry workers. But in 1996, Rodriguez and Sweeny, and the people around them, chose to make strawberries the defining fight in the UFW’s attempt to re-enter the fields.

Why?

They thought it was a hot shop. They got that idea towards the end of the 1995 strawberry season. Most of the workers at a medium-sized ranch, VCNM farms, had walked out of the strawberry fields in protest against the fact that they were being paid below the industry standard and because of their displeasure with a particularly hateful foreman. They immediately won their wage increase, and with UFW help, they filed for a representation election. Unopposed, the UFW won that election 332 to 50. Ignoring the history of trouble that the UFW had had holding on to strawberry contracts, AFL-CIO and UFW organizers quickly decided that strawberry workers were eager for organization. And besides, strawberries were much like grapes, a specialty crop that would be relatively easy to boycott, unlike the staple lettuce, which had proved hard to boycott back in the UFW’s days of power and influence. Moreover, the institutional wisdom of the UFW was that boycotts and the threats of boycotts—and not the power of the workers in the fields— had been the key to the UFW’s early success.

Even in retrospect, it doesn’t seem like such a terribly wrong decision. Except that it reflected a relative ignorance about the character of farm worker struggle. During the harvest season, when the growers are vulnerable, farm workers will often engage in slow downs, or short walk-outs (paros), to try to increase their wages or in protest against some grossly bad working conditions. Especially in crops that have to be picked quickly when they are ripe (like strawberries) a short walk-out can put enormous pressure on the grower (whose entire investment is tied up in a successful, timely harvest) and often win immediate concessions. But win or lose, the workers usually go back to work quickly. These short protests do not mean that workers can maintain their commitment over long periods of time. In the fields, they are frequent and brief. They are far different from a walkout or protest in a factory which happens with much less frequency but usually is capable of lasting a longer period of time, and is often an indication of a great willingness to organize. The UFW organizers, with little recent experience in the fields, and the AFL-CIO strategists with almost no understanding of the dynamics of farm worker struggle, mistook a relatively common farm worker paro, and an unopposed election victory to mean much more than it did.

Many of the problems that followed were inherent in the structure of strawberry production, another reason that the UFW had had trouble in the berries before. Agribusiness is not a single industry, it is a string of mini-industries, and strawberries have their own special story. They demand great care; people around Watsonville say strawberry production is more like horticulture than agriculture, and therefore most strawberry farms are relatively small. On these farms the owner or manager directly supervises the work to ensure, as far as possible, high production and good berries. These small farmers—a majority of whom are Mexican and usually ex-pickers, themselves—hire their own workers, often employing relatives or people who came from the same small town that the boss came from in rural Mexico. This gives the farmers considerable influence among their workers, but at the same time, the small farmers have very little power within the industry. Power lies in the hands of the people who own the coolers and market the berries. A strawberry is wasted (that is, unmarketable) unless it gets to a cooler soon after it is picked, and so the owners and managers of the coolers have become the directors of the whole production process. (Coolers are multi-million dollar operations and there are about a dozen of them in the Pajaro and northern Salinas Valleys.) The cooler owners usually secure loans for the small growers, often lease them land, and always provide them with essential technical support. They then charge the growers for cooling the berries, shipping them, and selling them. So, no surprise, small growers teeter on the verge of bankruptcy, while the cooler operators keep getting rich.

How this system works against union organizing was demonstrated shortly after the UFW election victory at VCNM farms. Five days after the election, the grower ploughed under about a fourth of his acreage, then stonewalled the obligatory negotiations with the union, and declared bankruptcy. All the workers lost their jobs. The very next year the land was leased to another grower who hired a whole new work force. Hundreds of workers who had voted to be represented by the UFW had to find work at other companies, where some of the most militant were blacklisted. Among the Pajaro Valley’s several thousand strawberry pickers, word travelled fast.

Nevertheless, in 1996, in the season following the VCNM paro and vote, the UFW proceeded on the assumption that they were working in a hot shop. Forty organizers, their wages and expenses paid by the AFL-CIO, went into the fields in what union insiders called a “blitz campaign” arguing that if everyone signed up in the union then the companies couldn’t plough under all of the fields. They hoped to win a bunch of union elections quickly.

It was not to be. The cooler operators and the big growers, fearful of a UFW victory and a return of the high wages and worker control over production typical of the UFW’s golden years in the 1970s, went on a counter-attack. They funded a bogus anti-UFW workers group, they raised wages and improved working conditions, and, most effectively, they hired some of the ex-VCNM workers as “labor consultants” and sent them into the fields to tell other workers how they had voted for the UFW and lost their jobs. By the end of the 1996, despite a massive effort by the UFW, the union was unable to get enough support on any farm to file for a representation election.

Talk of the hot shop ceased.

The AFL-CIO Buys the Company

While organizing was going badly in the strawberries, the UFW was doing very well at what it had been doing ever since they were pushed out of the fields in the mid 1980s: organizing among liberal supporters and Democratic Party politicians. Although they were unable to launch a strawberry boycott—the ALRA forbid boycotts of growers where the union had not already won a representation election—they did manage to generate enough pressure to win statements of support from 14 supermarket chains (including Lucky’s and Ralphs), various State Legislatures, and a few California City Councils. Favorable stories in major publications focused on the poverty of strawberry workers and welcomed a UFW return to the fields. Robert Kennedy’s son, Joseph P. Kennedy, visited the strawberry fields amidst nostalgic accounts of his father’s support for the UFW 31 years before.

But their greatest success was with the notorious Monsanto corporation, owners of one of the larger strawberry companies in the Pajaro Valley, large enough to own its own cooler. Monsanto, infamous for its genetic engineering of staple crops like corn and for the production and a wide selection of dangerous agricultural chemicals, was highly vulnerable to an AFL-CIO style corporate campaign. In a series of high level negotiations between Sweeney, Rodriguez, and Monsanto CEO Robert Shapiro, with direct intervention in support of the UFW by Vice President Al Gore, House Minority Leader Richard Gephardt, and veteran Democratic Party fixer, Mickey Kantor, Shapiro agreed to sell the company to David Gladstone and Landon Butler, whose regular business—investing AFL-CIO pension funds—was completely dependent on the good will of John Sweeney. (The Wall Street Journal reported that Monsanto loaned the money to buy the company to Gladstone and Butler, so that it was actually a silent partner in the new outfit.)

Gladstone (Butler quickly dropped out) changed the name of the company to Coastal Berry, signed a neutrality agreement with the UFW, visited his Watsonville strawberry fields, and both personally and on official company stationery informed his workers that they were free to vote for any union they wanted and that the company would not interfere in any way. Amidst much quiet celebration among UFW and AFL-CIO officials, UFW organizers turned all their attention on the 1,200 Coastal Berry workers. Finally, a year a half into the campaign victory seemed near.

Very soon a new problem surfaced. Although the AFL-CIO could buy the company, they could not buy the company’s supervisors and foremen, the people who managed the picking and packing in the fields. Such people were deeply threatened by a possible UFW victory, as their control over hiring and firing would be either completely eliminated or highly limited by a UFW contract. Supervisors of production, deeply knowledgeable about the intricacies of strawberry horticulture, they had significant power in the fields, independent of upper management. They augmented that power through their ability to assign people to a small number of privileged jobs, like driving the trucks between coolers and fields, or checking the finished work of the pickers.

Moreover, through their ability to hire and fire they also had great influence among the pickers, themselves. Very often a supervisor or foreman would hire his relatives or people who came from his same Mexican hometown, and these groups of workers formed tight cliques within the larger crews. Such groups sometimes owed even more than their jobs to their foremen or supervisors. On occasion a foreman had arranged for them to be smuggled across the border, and even loaned them money to pay the coyote. Familiar with Watsonville, the foremen knew where the new arrivals could find places to rent, and sometimes a foreman was not only the boss but the landlord. Workers dependent in so many ways often could be mobilized against the UFW, and soon after the Coastal Berry campaign began it became clear to UFW organizers that the workforce was badly divided.

David Gladstone couldn’t do anything about it. He knew nothing about agriculture and had to hire someone from the industry to run the company. The man he hired, Dave Smith, came from the Dole Corporation with an anti-UFW point of view, which almost anyone who knew enough about agriculture to run the business would have shared. Smith issued a series of mixed messages that served to enlarge the power of the supervisors and foremen. What followed was a kind of Marx Brothers movie of dispute and division. Fist fights in the fields. Competing paros between anti-UFW forces and UFW supporters: one day the truck drivers would walk out and thereby halt production; the next day UFW workers would walk out and production would also stop. Supervisors would fire workers; Gladstone would have them rehired. Sweeney unable to understand why Gladstone couldn’t follow through on his pledge to keep the company neutral threatened to take away Gladstone’s union pension business. Other growers, delighted by all the problems, and even financing some of the UFW opposition inside the company, sued Gladstone for collusion with the union. Gladstone spun like a top. He joined the UFW in appeals to the ALRB one day, and refused to discipline anti-UFW workers who had attacked UFW loyalists the next.

In the midst of the turmoil the contras established their own union, and filed for an election. The UFW, citing the pressure in the fields, refused to participate. The contra union, called El Comité, won the July, 1988 election 523 for the Comité against 410 for no union. Many legal challenges followed. There were disputes about the inclusion in the election of off-season Coastal Berry workers in Oxnard. Eventually, during the 1999 season, there were two other elections with both the Comité and the UFW on the ballot. The Comité won both of them: the first 646 to 577 with 79 ballots for no union; the second 725 for the Comité and 616 for the UFW. A year later, March, 2000, a judge agreed to separate the Oxnard division of Coastal Berry from the Watsonville division, and awarded the UFW representation rights in Oxnard (where the union had won the vote) while giving the Comité representation rights in the bigger Watsonville division. It didn’t much matter. The UFW had been defeated. The AFL-CIO pulled out. The Strawberry Campaign was over.

Who Were the Outsiders and Who Were the Locals?

The contra victory was not all muscle and bully-boys. They had one argument that seemed to take hold among many strawberry workers. They claimed that the UFW was a group of outsiders with little understanding of the actual situation in the fields, and interests quite apart from the interests of ordinary workers. One of the most difficult problems for the UFW and the AFL-CIO was that the more money and people they threw into the campaign, the more they tended to reinforce this contention of the contras. In April, 1997, when thirty-five thousand people marched in support of the UFW through this town of some fifty thousand people it was mighty impressive. But the overwhelming majority of those thirty-five thousand were people from out of town, and what was impressed upon the locals was not only the strength of UFW support, but the union’s position as outsiders in the community. When the AFL-CIO paid for forty organizers to come to town, and spent about $100,000 a month on the campaign (about $12 million in all) they became the biggest new business in the area, a business that was run by outsiders, by city folk, who had little understanding of this rural place. When the 1996 union summer program brought Chicano college students to Watsonville, it deepened the workers’ belief that the UFW was a Mexican-American organization that had little understanding or sympathy for the overwhelmingly Mexican strawberry workers. In contrast, said the contras, we live and work right here, we are your neighbors and relatives who have your interests at heart. It was to a large extent a phony argument, but it convinced a lot of people.

What were Sweeney and Rodriguez to do? The more they threw into the campaign the more they appeared to be outsiders. It is all so sad. Strawberry workers would have been better off if the campaign would have won. Workers throughout the USA would have benefited if the New Voices organizing drive had not bogged down in the fields of Watsonville. The opportunity was there. Chavez was gone; Artie Rodriguez honestly wanted to bring the union back into the fields. But he couldn’t overcome the burden of the union’s history and culture. Sure, many older workers remembered the UFW’s golden years, and wanted to bring the union back. Many other workers understood the need for a union, and were not fooled by the appeals of the contras, who they could see were led by supervisors and foremen. But the UFW had been out of the fields too long and were not sensitive to the differences between workers in different crops. They did not have a big enough group of local supporters in the fields, and did not have the democratic structure and culture necessary to build such a group. They had been damaged by the blitz campaign. For too long they had spent their time learning the ways of politicians in Sacramento and Washington, and not enough time listening to workers in the fields.

One last story

In the midst of the campaign, I was visited by a UFW staffer who had lived in the union center at La Paz for many years. She wanted to see if I would organize a house meeting. In the midst of the conversation I told my visitor that I hoped that the union won and I would do what I could, but I couldn’t whole-heartedly support the union until they had locals.

“Locals, what do you mean?” she asked.

“You know, where the workers who are covered by union contracts can vote for their own officials, who have control over most of their local dues, and have a certain amount of independence within the union.”, I said

“Oh, that might be a good idea, but the workers aren’t ready for that,” she answered.

Now, in 2015, the union still doesn’t have locals. Every official and staffer in the union is appointed. No farm worker can be elected into a union position. Add up the years. The UFWOC organizing committee was established in 1966. The union was granted a charter as an independent union in 1972. It is now 43 years later. When will the workers be ready?

___________________________◊◊◊___________________________

Of Representation and Power

By Robert Gumpert

On June 20th the Bronx Documentary Center opened “Altered Images: 150 Years of Posted and Manipulated Documentary Photograpahy”. The show has sparked a very public debate in the photo community about what was/wasn’t included and that debate has developed into a discussion of power and representation. While there have been many pieces written and many attacks made, four I thought of interest are these.

Lewis Bush is an English photographer and writer living in London. His piece about “informed consent” touches on many of the issues behind the larger debate of power and representation that often defines the content of journalism and documentary work. The piece can be found here. While you’re at the site you might also read his current pieces on the “Instagram migrant”, a viral marketing campaign that news outlets, including the Huffington Post, thought was real.

Roger May was born and raised in Appalachia, an area all too aware of power and misrepresentation. He too is a photographer and is responsible for the blog “Walk your camera” and the on going project “Looking at Appalachia” (Roger has posted some of my Harlan County work on the site). He has written two pieces recently about the issue:

“Why a Confrontation Between Photographers and Locals Turned Ugly in Appalachia”

“Taking Liberties, Taking Shortcuts, and Taking Advantage of People”

Lastly from the scribblers point of view: on 6 August 2015 Barbara Ehrenreich wrote a piece for the Guardian of London “In America, only the rich can afford to write about poverty”.

All interesting and thoughtful reads on a subject that should be in the mind of all that do this kind of work.

August 1974: Coxton, KY. Retired miner with black lung and the O2 he needs to breath. Photo: Robert Gumpert

Earl Dotter, the labor photographer working out of DC, sent around the following link to the NPR obit of Dr. Donald Rasmussen “Doctor Who Crusaded for Coal Miners’ Health..” Dr. Rasmussen died on 23 July at 87 in Beckly, W.V. where he had spent 50 years treating coal miners.

Olney Odyssey # 14 – Advent Corporation – “On the Line”

By Peter Olney

When Mass Machine closed and ran to Nashua, New Hampshire in 1975 I assumed new duties as the District Organizer for the political organization that I was a member of. The duties of the “DO” included travel throughout New England meeting with comrades in Rhode Island, Connecticut, New Hampshire and Massachusetts. Every month I would Greyhound to the Big Apple and huddle with leaders of the organization from throughout the Northeast. Those regional meetings usually consisted of the leaders from NYC barking signals at the rest of us about how to carry out the work. I felt a little of the Red Sox -Yankees rivalry polluting my perspective on the imperial directions from the New York comrades whose work had seemingly more scale and grandeur than ours.

When our organization fractured and split in 1977 it was time for me to stop being an “organizational man” subsisting on cheesesteaks and glazed donuts, smoking two packs of Marlboros per day and ballooning to almost 300 pounds. It was time to get in shape and go back to work in the factory. To get in shape I remember going to the gym in East Boston where I was living and using the upstairs balcony, which circled the basketball court as my jogging spot in the winter. To run a mile you had to do 22 laps. My first time out I could barely walk one lap without huffing and puffing and exhausting my 26-year-old body. As for work…..

My friend and comrade Bruce had been working at the Advent Corporation since 1974. Advent was the creation of Henry Kloss of Cambridge Sound Works, AR and KLH fame. The company produced quality loud speakers for stereo systems and was a pioneer in the development and manufacture of the first big screen TV’s. In fact, in the fall of 1978 I watched on a big screen, with the rest of the Advent work force, as Carl Yastrzemski popped out to end the one-day play-off with the Yankees that entombed the Red Sox season that year.

Advent was located on Albany Street in Central Square, Cambridge Massachusetts, right down the street from my first employer, NECCO candies. Advent had been “salted” “industrialized” or “colonized” by almost every stripe of Maoists and non-Maoist political organization. In short, the place was full of young Reds working side by side with the largely immigrant Italian, Haitian, Puerto Rica, Azorean, African American and ethnic white work force. That made for some sharp political engagement. Did African-Americans constitute a “Nation of a New Type”? Which Eritrean revolutionary organization had the correct line? The correct position on the Angolan liberation struggle was debated in the lunchroom and dueling newspapers were sold at the entrances to the facility. Interestingly however as I was to discover there were several workers who had actually fought in the Portuguese imperial army whose defeat in Angola, Mozambique, and Guinea Bissau led to the end of the Salazar dictatorship in Lisbon in 1975. So beyond the paper intellectual wars there were real discussions with real combatants who had been shaped, as were Vietnam vets, by their experiences on the ground.

While it may seem obvious that the stage of struggle in a non-union plant is to organize the workers into a union, …”

Another comrade, Barbara, needed work also, and we wanted to see if we could build on Bruce’s base and stature in the facility. We started work in the late spring of 1978. Bruce had been there long enough and won friendships to the extent that he had his own “apodo” in Spanish. His nickname was “Gallo” or rooster because of his physical bearing and his aggressiveness in dealing with supervisors. Steadfast in his defense of fellow workers Bruce was suspended by the general supervisor of the loudspeaker division for 5 days, April 27 – May 1 1978, for speaking up for a woman injured on the assembly line. 21 workers walked out in support of Bruce and were also suspended for three days. While Bruce and the 21 would later recoup their lost pay in an NLRB settlement in November later that year, the working conditions were steadily deteriorating. Many pointed to the fact that Henry Kloss, viewed as a beneficent and brilliant owner, had sold out control of the company to industrialist Peter Sprague of Sprague Electric in 1976. Sprague had made a name for himself by acquiring National Semiconductor and the British firm Aston Martin of James Bond 007 car fame.

When Barbara and I arrived at Advent we immediately formed a strategic collective with Bruce to guide our work. Looking back I am both impressed and astonished at the deliberate and meticulous approach we took to our work together. This is almost 20 years before the widespread use of word processing, and we typed a 6 page legal sized, single spaced sum-up of 4-5 months of work. This “Sum-Up of Advent Work” included the following sections:

1. Key points from the past history of the Company

2. Present stage of struggle – Organize the Unorganized

3. Task of this Stage

4. Advances in the Period

5. Key Questions for the Future.

While it may seem obvious that the stage of struggle in a non-union plant is to organize the workers into a union, this was not always the “center of gravity” for young Reds. Sometimes a campaign to stop a death sentence in Louisiana was made primary over the ongoing issues of economic exploitation and injustice in the factory itself. We sought to correct that approach which we characterized as “left infantilism” and projected our tasks as the following:

1. Expose the Company’s nature

2. Build struggle against the company

3. Tighten up the advanced as organizers

In our sum-up we said that; “To accomplish these things we set a line that we would bring out a workers’ newsletter, On the Line. This would be a militant and hard hitting graffiti and gossip sheet”

On the Line was a monthly publication, which carried news of the goings on among the 600 workers at Advent. We even published worker’s poetry like these prophetic lines:

ADVENT’S HISTORY

The first day you start

They treat you so pleasant

If you last out the week

You are considered a peasant

You work so hard

To make ends meet

And all you have to show

Are two blistered feet

So you ask for paid sick days

And all you get is a laugh

They give you an excuse

That would make you baugh

If you let them do this

Without a fight

Then you don’t know the difference

Between wrong or right!

The poem was a set-up piece for a battle for sick days launched in October of 1978.

Our strategy and tactics took into account the need to ratchet up the pressure, and we employed a company-wide ballot to poll the workforce about their wishes. The ballot was published in Portuguese, English, French, Spanish and Italian. The balloting result was 237 Yes and 3 No. The results were presented to Personnel Manager Art Stewart by a delegation that marched on his office on December 15th. He declined to receive the results telling the workers to go through channels by talking to their supervisors. As a result department-by-department delegations were organized. Even without a union the workers at Advent, partially because of their home country experience, were ready to engage in militant actions. Marching on the boss was not an uncommon practice whether as a whole plant or by departments. Perhaps the most militant workers were the Haitians who had emigrated from the most impoverished country in Latin America and were only too conscious of imperialism and the comprador role of the brutal Baby Doc Duvalier dictatorship. Our focus and activity was on tapping these revolutionary spirits and, with them leading, building broad unity around the “center of gravity”, day to day battles on the shop floor.

We also set out to ally with the community struggle against styrene poisoning. Styrene was the substance that was used in the building on Emily Street where the big screen TV screens were manufactured. For a longtime the community, led by the Cambridge port Alliance and resident Bill Cavellini, had been agitating against the styrene effluent, which was polluting their neighborhood. We met with Bill and began to communicate the concerns of the community in the pages of On the Line.

What care and effort was spent on the minutest of details! In summing up a party we held prior to the launch of the sick day campaign, we noted that, “Even Carmela Calhoun of the fascist caucus brought her hot peppers to work the day before the party. Talk in the shop flew around Santos’ salsa tapes and to who was going to get first dibs on Ernie’s ham hocks. Big Nick, the Hitter, came forward to tend bar and personally sold 20 tickets in advance for the party.” This is the richness of real face to face, “mano a mano” organizing that is required to move groups of workers. Our conscious deliberate approach was beginning to reap benefits.

But in an ominous development both Barbara and I were laid off in November of 1978 along with fifteen other workers. At the time this was seen as a seasonal occurrence and did not affect our battle plan around sick days. We were wrong; it was a warning sign of big doings afoot.

Olney Odyssey #15 – New Hampshire Strikes Again!

An open letter to Congress Members Ros-Lehtinen, Rubio, Cruz, and other concerned Conservatives

By Myrna Santiago

Dear Congress Members Ros-Lehtinen, Rubio, Cruz, and other concerned Conservatives,

About the renewal of US-Cuba relations, you really mustn’t fret so much, honestly. On the contrary, there are many fine reasons for Conservatives to support normalized relations between the two countries. I will give you only three.

First of all, opening an embassy in Havana will be the best thing that ever happened to the cause of overthrowing the Cuban government. An embassy comes with a Political Officer and fulltime CIA staffers. Have you forgotten all the victories our embassies have scored over the years in ridding Latin American countries of leftist governments? Remember Guatemala ’54, Chile ’73, and Nicaragua ’90? In all three cases our embassies were extremely successful: organizing, funding, and directing opposition groups until they ousted the socialists. The Women in White will multiply in droves with an embassy!

Secondly, ending the embargo, an excellent policy option. Why? Because, as we all know, Cuba is a poor country that does not feed itself. If US farmers begin selling foodstuffs to Cubans, in no time we will accomplish a couple of objectives. One, Cuban agriculture, such as it is, will be overwhelmed by the sheer flood of American rice, beans, wheat, and other staples, just as Mexican corn was under NAFTA. In no time Cubans will be dependent on us for their most basic meals. Who can dispute that having a lock on a country’s food supply is not leverage to influence their politics? Furthermore, selling grains to Cuba will mean that the island will have to borrow money to pay for them. Who will make those loans? American banks, of course. You know full well what happens when any country becomes indebted to foreign banks – we don’t have to review the history of the 1980s to figure that one out: just look Greece and what’s coming to Puerto Rico. If we both lend money to Cuba and then get that same money back in food purchases, our banks and our farmers win. And the Cubans owe us more. When they cannot make payments, we can impose conditions on them, like privatization of anything we want, starting with the Cuban banking system. Well, Cuba has no banking system, which will make it even easier for us to own it. In no time, a pile of our t-shirts will bear the “Made in Cuba” label and they will cost, what, five dollars? Because a job that pays one-dollar-a-day is better than no job at all. Just ask the Haitians next door.

Third, allowing free travel between the US and Cuba will also be good. Who can resist American culture? Imagine the island flooded with US movies, music, clothing styles, fast food (there goes the much touted Cuban national health system), sports (every Cuban baseball player will be swinging for one of our teams!). And for all you young Conservatives: can you say Spring Break??? Cuba has the healthiest coral reef in the Western Hemisphere, why stop at Varadero? Unfortunately, there will be some downsides to normal relations with Cuba, including prostitution, drugs, and money laundering. But even these will provide new opportunities and markets for our public safety private sector. When all the above is in place, how long before Cubans take to the streets, protesting and staging strikes and the rest? And guess who will be out there to repress the mobilized? The Cuban army, of course! Anyone ready to sell rubber bullets, water houses, personnel carriers, and tear gas? When the Cuban army turns on the people, what Democrat or liberal anywhere in the United States will defend the Cuban government? How long after that do you think anyone remotely related to the Cuban Communist Party will be ruling anything?

So, you see, the normalization of relations with Cuba really is a Conservative dream come true.

Myrna Santiago

___________________________◊◊◊___________________________

Obama and Castro traded letters confirming plans to reopen permanent diplomatic missions on July 20

A blindspot that crippled

By Bill Fletcher, Jr.

“The New Voices campaign of 1995 was one of the most important efforts within organized labor to respond to the crisis afflicting the movement. There are two issues that are regularly ignored in analyses of this effort, specifically, the Left and the issue of the union/community relationship. The following is a modest note on these and a suggestion that there is need for further exploration of these issues.”

The New Voices reform effort was very significant in many ways. There was a deep commitment to building a revitalized trade union movement. But one feature of this was a strange and select view of labor history and its lessons for contemporary labor. A classic example of this was the recognition that unions needed to place more resources into organizing. It was noted how much–in terms of resources–the United Mine Workers had devoted to organizing. While this was true, and while it was also true that the contemporary union movement needed to redirect resources toward organizing, what was ignored was the role of the Left in helping to move the resurgence of organized labor.

The Congress of Industrial Organizations was built through a combination of factors. One of those factors was the role that the Left had played in building the union movement in the 1920s and 1930s. Communists, Trotskyists, Independent socialists, and Muste-ites all played a major role, in part through the dedication of cadre who were deployed to build various movements within the working class. Leaders of the CIO were willing to admit their need for the Left, at least during the 1930s. The Left played a major role in sustaining efforts, e.g., the unemployed movements, providing leadership as well as leadership training.

In the 1990s the much weaker US Left did not exist as such a force. Additionally, the leaders of the New Voice movement placed no attention on playing any role in rebuilding the Left. While, in many cases, leftists were hired as staff and/or tolerated in certain elected positions, there was little effort to acknowledge a role for the Left, let alone to advance a discourse shaped by the Left. Thus, the history of labor’s various efforts at resistance and resurgence almost never mentioned the significance there was to the existence of a Left in the building of a trade union movement.

The second, but related factor that was largely ignored by the New Voices movement was the question of the role of the union/community alliances. Although in the early 1990s there was renewed attention to building ties with community-based organizations and movements, such relationships continued to be dominated by a transactional and tactical approach. Specifically, unions would turn to community-based organizations when they felt that they–unions–were in trouble but there was no sense of building strategic ties between the two sectors. This contrasted with efforts that could be found in the 1930s where there was a more open recognition of the need for such relationships, at least on the part of a segment of the union movements. The ties built between segments of the CIO and the National Negro Congress, for instance, were very significant and played a major role in the successful unionization of Ford Motors. Yet this history has been largely forgotten or, when remembered, ignored.

The New Voices ignored or dismissed these two very important legacies. In doing so they operated with a blindspot that crippled, if not doomed their reform efforts. This does not mean that the other factors were of no or little importance. Rather, these points noted here are more aimed at completing the circle.

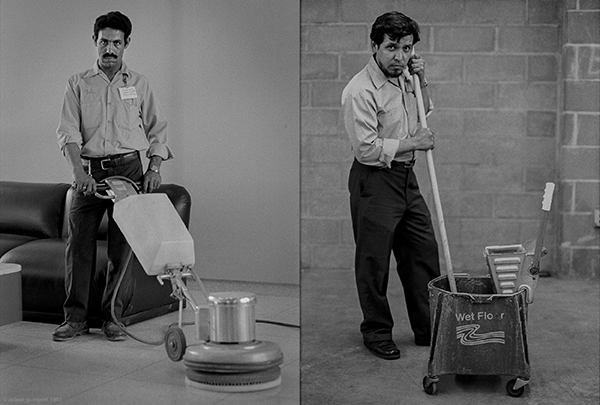

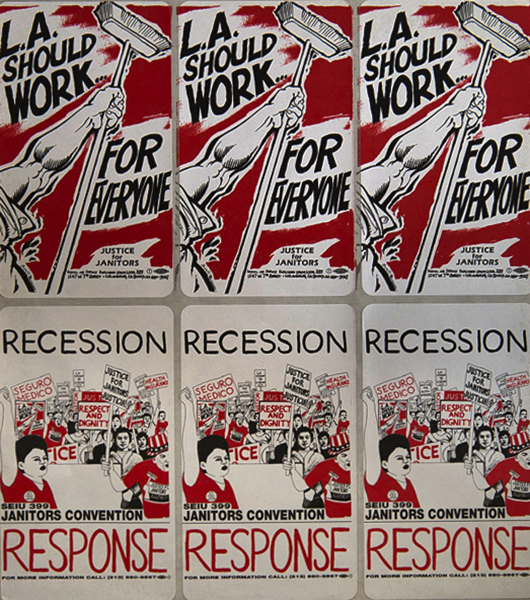

Justice for Janitors: A Misunderstood Success

By Peter Olney and Rand Wilson

Part two of a series looking back on the 20th anniversary the AFL-CIO’s New Voice movement

John Sweeney, his officers, and their staff team came into office with high expectations and great optimism. A good part of their inspiration was drawn from SEIU’s Justice for Janitors campaign that many had directly participated in or saw as a model of success. After all, Justice for Janitors had succeeded in mobilizing members, winning better contracts and organizing thousands of new, mostly Latino members while garnering broad public support.(1)

Founded in 1921, the Building Service Workers was a Chicago-based janitors, window washer and doormen’s union. George Hardy, the predecessor to John Sweeney as International President, was a San Francisco native and organizer who took his comrades from Hayes Valley to Southern California after World War II to organize janitors in Los Angeles. From his base at Local 399 in Los Angeles, Hardy launched the campaign to organize Kaiser and health care that would transform the Building Service Workers into the Service Employees International Union.(2)

By the 1980s, much of the union’s market power among urban janitors had eroded as the industry restructured to a cleaning model that relied on outsourced contract cleaners instead of permanent staff. When Justice for Janitors was launched in the late 1980s however, the union still retained tremendous power and thousands of members in its traditional strongholds of New York City, Chicago and San Francisco.

In these cities, the union had excellent contracts with good wages and benefits for doormen and cleaners. These were the “fortresses” that played such a crucial role in the success of the janitor’s campaigns in Los Angeles, San Jose, Oakland, Denver and San Diego where the battle was to reorganize weak and degraded bargaining units and organize thousands of new members.

The early janitor organizers in Los Angeles recognized the importance of first rebuilding and re-energizing their base. One of the first campaigns undertaken was the contract campaign for downtown janitors. Cecile Richards(3) skillfully directed a winning contract fight for the approximately 1,000 janitors in the core market of LA. The contract struggle gave the union a new core group of supporters; many of whom became the front line soldiers in the campaign to organize the vast non-union market outside of downtown.

A key to the membership mobilization was “market triggers” that Local 399 inserted into its collectively bargained agreements. The triggers provided for automatic increases in wages and benefits if the janitors union succeeded in organizing 50 percent or more of the commercial buildings in mutually agreed upon geographic areas. Thus, when rank and file union janitors marched for “justice for the unorganized janitors” it meant marching to increase their own wages and benefits and to gain a more secure future.

In Los Angeles long-time union signatory contractors like International Service Systems (ISS) were operating non-union or in the case of American Building Maintenance (ABM) double breasting by creating new entities like “Bradford Building Services” to clean non-union in LA.(4) On May 29, 1990 the SEIU janitors boldly struck non-union ISS buildings in the entertainment high rise complex called Century City. When the Daryl Gates-led police department brutally attacked the striking Los Angeles janitors on June 15, the shocking news footage traveled around the country.(5) With some prompting, SEIU Local 32 B-J leader Gus Bevona threatened ISS with a shutdown in New York City if the company didn’t settle in LA. That strategic solidarity contributed to victory and the nearly immediate organization of thousands of new members for SEIU Local 399.

Most successful organizing is not done in a vacuum, existing members have to be front line apostles.

The campaign even had a movie made about it; “Bread and Roses” directed by the Scottish filmmaker Ken Loach.(6) It did a fine job of presenting SEIU’s strategy to organize industry-wide and build a campaign that resonated broadly in the community particularly among Latinos. It also portrayed the challenges organizers always face in holding the unity of the working class. The deep divisions and contradictions among workers are often the biggest obstacle that needs to be overcome in order to have a shot at beating the boss.(7)

The Justice for Janitors campaign was often showcased by New Voice supporters as a premier example of “new” organizing. But what many union leaders and key staff strategists have missed is the fact it was not a “blank slate” campaign disconnected from the sources of SEIU’s membership and contract power. As we have shown above, it was a campaign (as William Finnegan also pointed out in an excellent New Yorker article) deeply rooted in the existing power, base and history of SEIU.(8)

Herein lies an important lesson: It takes members to organize members! While obvious and hardly a new concept, it was embraced as part of the New Voice strategy of “bargaining to organize” in 1996. But sadly the importance of worker-to-worker organizing, building strong committees and using our bargaining power with employers got lost. As a result, we’ve seen a multitude of costly “Hail Mary” passes being thrown in the labor movement with little chance of success because there is not the power of the market or the members in play.

Justice for Janitors was a brilliant campaign that wisely by-passed the NLRB election process and leveraged better contracts and growth through an industry-wide strategy that relied heavily on creative confrontation and community alliances. It was not however a campaign out of whole cloth. It had the power of the existing membership in major markets, leverage with many of the employers who were operating non-union in new markets and the loyalty of many members who had seen the union’s power in making a better life for themselves and their families. Bargain to organize remains a successful starting point for real organizing, member-to-member.

Most successful organizing is not done in a vacuum, existing members have to be front line apostles. Can United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW) supermarket members be expected to support the organization of Wal-Mart workers if national supermarket chains are weakening their labor contracts, and the union is not responding with a national bargaining strategy?

This is the dilemma so often faced by trade unionists in thinking about bold new initiatives. For example, in the aftermath of the success of the Janitors campaign in Los Angeles the union succeeded in organizing many new janitors, raising their wages and in some markets, winning health insurance. The contractors responded by cutting staffing to recoup their margins. SEIU Local 399 engaged in several dramatic strikes against staffing cuts. These were strikes by workers under contract. One strike led to the arrest of all 55 janitors in the largest office building in Los Angeles in 1993. While the strike led to victory in the staffing conflict in that building, it created tension with the external organizers who saw any deviation from focus on new organizing as problematic and any disruption of union signatories as a problem. Never an easy dilemma, but if existing members are not confident in the union’s power to deal with their lives then their support for external campaigns becomes more limited.

Several years ago, the new “Our Walmart” campaign was rolled out and previewed at a strategic organizers retreat in California with an impressive power point presentation on Walmart’s markets, finance and vulnerabilities. The presentation projected the organization of one percent of Walmart’s workforce by the end of the campaign’s first year: 12,000 workers. As the presentation came to a close, a veteran organizer from the Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees Union (HERE) very respectfully made two points with respect to his organizing experience:

•It has taken HERE 20 to 25 years to build an organizing culture in some of its locals among its existing membership base

•In the hotel industry the “big dog” is Marriot and the union did not think it had the power and resources at this moment to take that company on.

The HERE organizer had just effectively deconstructed the Our Walmart effort. This from an organizer with a union that successfully waged a “bargain-to-organize” campaign with the Hyatt Hotel chain that resulted in organizing rights in new Hyatt’s in selected markets. This is another example of the effective use of the “union fortress” to grow.

The urgency of organizing millions of workers to reclaim the union density levels of post-World War II led the ambitious “New Voice” apostles to steer the labor movement away from emphasis on long, patient organizing drives and deep worker-based organizing. What an irony that a campaign whose very success was based on the strength of its existing membership base was — and continues to be — misconstrued into an example of how large scale organizing can take place without the fundamental imperative of engagement with our existing membership.

Footnotes

(1) “Justice For Janitors: A look back and a look forward: 24 years of organizing janitors”

(2) For information about George Hardy and for the history of the Building Service Workers

(3) Richards is the daughter of Texas Governor Anne Richards and now director of Planned Parenthood.

(4) International Service Systems and American Building Maintenance

(5) “Janitors Suit Settled,” Sonia Nazario, Los Angeles Times, September 4, 1993

(6) “Bread and Roses”

(7) Scottish screenwriter Paul Laverty came to Los Angeles in the early nineties to march and hang out with the janitors and their organizers. His screenplay was made into “Bread and Roses” staring a young unknown actor named Adrien Brody cast as the SEIU organizer. George Lopez, later of TV sitcom fame, played a vicious cleaning company supervisor.

(8) Finnegan’s showed remarkable insight in his article, “Dignity” about the “Fight for $15” in the September 15, 2014 issue of The New Yorker where he points out the fundamental difference between the Justice for Janitors campaign and Fast Food organizing: “The Justice for Janitors campaign of the nineteen-nineties offers a good precedent for the current fast-food campaign, [SEIU President Mary Kay] Henry said. The janitors were fissured by the broad move of commercial property owners to subcontracting, much as fast-food workplaces are fissured by franchising. Their nominal employers, small cleaning companies, had no power and thin profit margins. The tactics of the janitors were unorthodox, and included mass civil disobedience: closing freeways in Los Angeles; blocking bridges into Washington, D.C. Their goal was to get building owners to the table, and in time they succeeded, in some cases nearly doubling with their first contract the compensation they had been earning. The movement was largely Latino, and crucially strengthened by undocumented immigrants who stepped up, risking deportation. But big-city janitors had been unionized, historically—and in some cities, like New York, still were—so the fight was really to reorganize and rebuild. There is no comparable history in fast food. More important, the fast-food workforce is just under four million and growing, and the main companies are so rich and powerful that the stakes are higher than in any labor struggle in recent memory.” (Emphasis added)

_______________________________________________________________

Previously in the series looking back on the 20th anniversary the AFL-CIO’s New Voice movement

Part One: Just a whisper now: a look back at the AFL-CIO New Voice after 20 years

The Elections in Chicago – A View From Chuy’s Base Area

By Bill Drew

Chicago hasn’t seen such electoral contention since the days of Dick and Jane – and Harold. Even in defeat, the Jesus “Chuy” Garcia challenge brought a familiar spirit back to the city by the lake. No one expected the immigrant from Durango to challenge the abrasive Rahm in a run off. Nor could we have predicted the surprising synergy that would result from over a dozen insurgent ward campaigns and Chuy’s crusade. In the 12th ward on the Southwest side, we learned that politics is local.

Following a spontaneous and wildly successful petition drive which netted 62,000 names in less than a month, passion in wards north, south and west threatened to ignite a city-wide blaze.

To our chagrin, the wind in our city could not propel enough burning embers across the Dan Ryan and the Eisenhower. In the posh areas of the new economy, condo dwellers stamped out the sparks with their tony boots. They rushed to the polls as if panicking in a lakefront fire drill. Municipal employees and pensioners tried to nurture the flame out southwest and northwest. But suspicious property owners turned on their sprinklers in spite of distaste for mayor’s one percent. Constant TV attack ads paid for with Rahm’s millions were the showers that fell harder on some neighborhoods than others.

Jesus “Chuy” Garcia awoke long dormant alliances. Young activists stepped forward and exchanged skills with veteran organizers. Hundreds worked to create new mechanisms for electoral struggle. Aldermanic candidates emerged to give leadership to progressive ward organizations. Terms like “privatization”, “community policing”, “progressive taxation”, “participatory budgeting”, and “the neighborhoods” became familiar topics.

When the votes were all counted, we were not the kind of movement that could topple Rahm Emanuel’s coterie of global power brokers. We are a populace fragmented by the cunning of the one percent. We rose up to fight back. We lost. And yet we gained a lot.

At the risk of over simplification, the mayor’s tactic was to arouse suspicion of a Mexican American populist. To whites, the message, encoded in “dog whistles”, was that Chuy is a “nice”, but “naïve”, Mexican “boy”. His call for audits of city corruption was spun as an evasion of fiscal responsibility. At a more sinister level, the unspoken message called for unity to keep the burgeoning Latino community in its place – at the precarious margins of progress. Fearful of dire warnings of municipal bankruptcy, many white voters sided with the one percent. Chuy’s biggest strength is his unapologetic compassion and his defense of the undocumented. In the minds of a beleaguered middle class, this roughly translated as “keep them in their place, scrambling at the bottom alongside the blacks”.

And to African Americans, many of whom have been pushed even beyond the margin, there was not a deep enough reservoir of solidarity. Competition for jobs and economic opportunity between blacks and Latinos has created a divide. The rivalry, often downplayed in polite discussion, is nonetheless real. It’s the most recent iteration of the age-old scenario – not unlike the divisions set up at the turn of the previous century when southern sharecroppers were imported as replacement workers in the stockyards.

More than anything else, the race hinged on race.

Significantly the Latino community in Chicago supports a relatively vibrant commercial class.

Yet we gave them a scare, flexed some political muscle, won a handful of new aldermanic seats, learned a lot, increased our numbers, and projected an example for similar coalitions and struggles nationwide.

The key was a grass roots approach. Some purists missed this important dynamic. They stood on the sidelines calling Chuy a corporate neo-liberal in disguise. They predicted that Chuy would enact austerity budgets. They feared that his campaign was not radical enough to energize those who have lost hope. They jumped on weaknesses in outreach to African American communities as a deal breaker. The campaign’s call for hiring of 1000 police officers was cited as an indication of treachery.

In the near southwest 12th ward, we didn’t even try to influence the citywide campaign over which we had little control. We felt that, if everything fell into place, we might be able to replicate the minority-led Harold Washington inter-regnum of thirty years ago. But, more realistically, we were fighting for power at the ward level and to defend our people. As things stand, neo-liberal schemes define the political landscape. Rahm Emanuel personifies this perfidy along the predominantly Latino Archer corridor. Transfer of wealth proceeds apace.

The elevation of Commissioner Garcia as our standard bearer at first seemed accidental – driven, as it was, by Karen Lewis’ brain tumor and County Board President Toni Preckwinkle’s refusal to accept the challenge.

But it is not random chance that reform’s most credible and trustworthy candidate arose from the Latino political movement. Commissioner Garcia has positioned himself as an honest independent. He has been steady in opposition to each successive re-incarnation of machine politics. He got his start as a pioneer for Chicano empowerment in the late seventies. The ward organization, which he helped form in Little Village, is the only opposition precinct apparatus which has stayed intact over this span. The man has displayed courage several times in his career – from his willingness to stand in for his assassinated compadre, Rudy Lozano, to his recent acceptance of the torch from Ms. Lewis, the outspoken leader of the teacher’s union.

Chuy’s campaign meme was that Rahm takes from the neighborhoods and rewards the rich. The gleaming center versus decaying ghettos and barrios was a fundamental metaphor. Specifics in regards to safety, education, revenue generation, and services were plentiful. Problems with the mix of issues, the way they were broadcast, difficulties in creating a citywide campaign, and missed alliances do not alter the key point – Chuy was articulating a broad populist message.

With regard to Chuy’s strongest base of support, critics should own up to their own blind spot. He unapologetically spoke for a large, multi-class base in a Latino community that is marginalized and becoming more so. It is almost too obvious to state that Latinos are overwhelmingly members of the working class. The dynamism of the Latino fabric in Chicago is hard to ignore.

Correctly and in keeping with his longstanding approach, Chuy subsumed his Chicano politics within a call for class justice. Unions were his financial bedrock. Class was a unifying blanket. Good government was a broad appeal. But the speakers of Spanish, the people whose names end in “ez” and “ño”, the Latinos of Chicago, were his reliable electoral base.

In our work in McKinley Park, we were struck by the Latino solidarity. Every precinct produced vote percentages coinciding almost exactly with the percent of Latino voters. Of course there are small remnants of the discredited Hispanic Democratic Organization (HDO). In my own precinct, there are four reliable Rahm votes in the household of machine-backed State Senator Tony Muñoz. And, of course, we know white and Chinese voters who went with Chuy. But the general pattern holds.

Significantly the Latino community in Chicago supports a relatively vibrant commercial class. Their interest is strongly with the economic well-being and the secure residency status of all Spanish speakers. They along with Latino professionals – both public and private — were totally on board. It was never hard to solicit botanas and comidas for Garcia events. Rahm Emanuel photo ops with Latino elected officials, who called themselves the Rahmtinos, elicited derision in all Southwest side barrios.

In the run off, Latino turnout, while elevated and enthusiastic, did not cascade to the mighty levels that we experienced with African Americans voting for Harold Washington or Barak Obama. Social and historical reasons prevail. A huge cohort of noncitizens intermingles with many who are not registered or feel culturally and linguistically alienated.

Similarly, the hoped for re-unification of the Black-Brown alliance of the 1980s, was not spectacular. Emanuel’s money produced saturation attack ads, street level pay offs, misleading promises, and appeals to racial divisions by proxy publicists. Some lingering loyalty to Rahm as an emissary from President Obama depressed the African American turnout significantly. Rahm pulled down majorities in the mid-50s to mid-60s in African American precincts.

Long known as a united voting bloc, African Americans were divided and confused. Could the Garcia campaign have said the magic words and repaired a historic divide? Weaknesses in the commissioner’s campaign were a reflection of something broader. He could not create on-the-ground leadership and proof of good faith for such an alliance in a matter of weeks. Stubborn realities of segregation, alternating tactics of favoritism and neglect, gerrymandering, and economic competition have chilled the dialogue among the two communities.

Chuy’s history is replete with efforts to reach out and champion the black agenda. He was a swing vote for Harold Washington in council wars. He has stood against discriminatory landlords and segregated high school boundaries. More so than any current elected official in Chicago, he has worked to create working multi-ethnic and multi-issue coalitions. When he was in the Illinois Senate, he was a member of the Black caucus. In contrast, the incumbent one percenter used guile to fashion relatively cheap and insignificant gestures as a lifeline to African Americans.

… we had such a large base of volunteers that we were able to approximate the old style machine structure

Several African American leaders and activists were prominent and instrumental. For every compromised clergyman there was a Jesse Jackson. For each Bobby Rush there was a Danny Davis. For every charter hustler there was an education activist like Kenwood’s Jitu Brown.

In the 12th ward, Pete DeMay’s aldermanic campaign intermingled with Chuy’s mayoral crusade. Like Chuy, Pete stepped forward when no one else was willing. He entered a one-on-one bout with machine regular, George Cardenas.

Pete was an anomaly – a white guy with credibility as a United Autoworkers organizer, fluent in Spanish and with organizing experience in Puerto Rico, Mexico, and Tennessee. He was a hard-working and combative campaigner. He united with an existing core of activists in the McKinley Park neighborhood and attracted an expanded following. His platform centered on education, end to regressive revenue measures, as well as more equitable public safety and ward services.

It is here, at the deepest level of political activity, that the elections of 2015 are interesting and instructive. In the precincts, we mixed the battle for local accountability with the broader, city-wide effort. We went toe to toe against a well-funded, entrenched machine. We stood upright in the middle of the ring. We were surprised to see a Latino cheering section for the güero against a man who has a surname evocative of Mexican radicalism. So effective was the challenge, that Cardenas appealed to a hometown referee – Rahm’s Chicago Board of Elections. Ruling on preposterous legal pretexts, the board declared a technical knockout. Pete was stricken from the ballot. We were down for the count before we could finish the first round.

We’ll never know if Pete’s aggressive campaign could have ridden Chuy’s coat tails to victory against a Latino apologist for neo-liberalism. His spunk and organization touched a nerve. Even without his name on the ballot, we netted an unprecedented 20 to 25 percent write-in count in the municipal general election.

The use of legal shenanigans to derail Pete’s challenge was as obvious as it was odious. The required number of nominating signatures was 473. We collected over 2100. Of these, 1400 were invalidated in challenges. The majority were stricken based on overly precise requirements that the signatures match exactly with their original applications. One hundred and fifty names were ruled “out of district” by a computer program that was obviously flawed. Each in-district address that was rejected was clearly within the boundaries.

Then, with a remaining cushion of 300 above the needed level, Cardenas’ election lawyer submitted witnesses and affidavits supposedly proving a pattern of fraud. The alderman’s staff had gone around the ward during work hours to badger signers into recanting their names on Pete’s petitions. On the basis of 47 coerced affidavits and 3 suspect witnesses, the hearing examiner declared all sheets turned in by Pete himself to be inadmissible. Our signature total fell to 407 and we were off the ballot.

Activists and constituents understood the cynical use of a municipal board to protect a favorite of Mayor Emanuel. The commissioner is a lawyer who has received over $200 million in municipal fees for billable hours in recent years. We made common cause with other campaigns who had suffered similarly egregious rulings. We rallied voters who saw these maneuvers as a sign of weakness by the incumbent and an affront to democracy. The commitment of the core tightened and the drive for write-in votes picked up steam.

Chuy had surpassed all expectations and held Rahm to only 45%. With none of the five candidates receiving more than half, the mood at our 12th ward election night gathering was mixed. We had brought home landslide numbers in all our precincts for Chuy. We knew that write-in votes were accumulating in astonishing numbers but Pete’s defeat was seen as unavoidable. The obstacles were too great.

Looking around the banquet room, the majority of Pete’s active campaigners where Latinos. They were union members. They were young people gaining their first taste of politics. They were from each section of a gerrymandered district. We all saw this cause as inseparable from the city wide crusade to “Take Back Chicago”.

Precincts were the critical unit of geography. The goal was to staff each precinct with people who live there. Typically in our southwest campaigns, the stability of such teams has been uneven. Most often – especially when the turf is larger than a ward — volunteers show up for canvassing. They are handed walk sheets based solely on the areas that have not yet been covered. In Pete’s campaign – because we had the added dynamism of working in concert with the Chuy mobilization – we had such a large base of volunteers that we were able to approximate the old style machine structure.

Democratic ward armies of the past have been based on captain and patronage loyalists. These teams are in decline nowadays because of a shift from hiring clout to sub-contracting and privatizing. Our home grown teams were able to match up favorably with the diehards. We held precinct meetings, put out specific flyers by neighborhood, and were able to allocate crews of watchers, passers, and runners at every polling place. Just as our ward was a battleground in the mayoral, the precincts were key for Pete’s challenge.

To grab and hold some power even at the ward level, this must be a continuing emphasis. We forged cooperation by local people of good will – from recreation and cultural leaders, to teachers and librarians, to retired and current union people, to the youth and the unemployed. Links to citywide issues and to the concerns of other neighborhoods are a priority. Of particular importance will be creating unity with African American communities.

Here in the Latino southwest side, the progressives fought five aldermanic battles in addition to the overarching Garcia effort. Though they were not arrayed as an official slate, there was an informal alliance which benefited each local race and contributed to Chuy’s organizing.The various teams picked up tips from each other. Those which didn’t survive the first round joined in to help out those still in the field and to work side by side in the mayoral. Marching bands from two of our high schools led parades to early voting.

The teams from various ward struggles and from the Chuy field offices now have an opportunity to forge tighter working unity. We face stiff challenges as Rahm begins his next four year reign. We expect renewed attacks in ever changing forms. That’s what it’s all about — learning from electoral efforts, gearing up for the next one, and directing a united front against inevitable attacks.

Baltimore’s Implosions

By Len Shindel

“A city wakes up in pain amidst the billowing smoke of deceit and dreams incinerated.”

How many times have I heard it? “I just love what they have done to Baltimore—the stadium and the inner harbor.” No doubt, many of same folks would say they love The Wire, too. But if they were asked to match the devastation of deindustrialization with a single city, Detroit would win hands down.

Baltimoreans share these bifurcated allegiances. Who doesn’t love a coliseum that so ably represents a city’s history of industry and hard work, even as one wonders how the metropolis will survive its gentrification?

I should have known my Facebook musing on a smoldering city would be touched by our schizophrenia about the cause of Baltimore’s troubles.

I listed a chain of legendary industrial workplaces that have long been shuttered, beginning with Bethlehem Steel’s Sparrows Point Plant, where I spent 30 years, most of them as an activist and representative of the United Steelworkers.

The plant, which, after Bethlehem’s bankruptcy in 2002, had been traded off in a corporate poker game between several owners, has been shut down for two years, idling more than 2,000 workers.

Just a few weeks ago, the 3,200-acre facility’s towering blast furnace –one of the world’s largest when it was built, a landmark that carried a star seen for miles each Christmas, one I memorialized in a poem–was imploded, spreading as much pain as finality.

So, I asked my Facebook friends what happens when dozens of legendary plants that employed hundreds of thousands, workplaces like General Motors, Western Electric, Armco Steel and Lever Brothers shut down.

I asked what happens when apologists for the outsourcers and “free” traders and financiers say not to worry. Good, clean jobs will open up. Young people locked out of opportunity will find bright futures. A rusty city will gleam. What happens?

My answer: “A city wakes up in pain amidst the billowing smoke of deceit and dreams incinerated.”

The “likes” poured in. In the narcissist vein of Facebook, I felt important and persuasive.

It took a former co-worker only a few seconds to burst my boast. Rob accused me of “making excuses” for rioting groups of inner city residents who “won’t take accountability for their own lives.”

I responded to him civilly. I said accountability for a polarized, suffering city should be expansive, encompassing the decisions not just of the folks at the bottom, but those of the wealthy and powerful, with a bit of introspection on the part of the rest of us.

“Accountability for their own lives.” I thought back on the struggle that had already been raging in the courts over discrimination in the steel industry when I was hired in 1973, one brilliantly preserved in a video, “Struggles in Steel,” by Braddock, Pa., steelworker sons Tony Buba and Ray Henderson.

Black workers had always been assigned to the dirtiest, most dangerous jobs in the mills. And they would lose their seniority if they transferred out to majority white departments, starting out at the bottom again, at the beck and call of the boom and the bust.

Years of lawsuits, rallies and lobbying had finally resulted in a consent decree that provided for reforming seniority systems and opening up trade and craft jobs to minority workers and women.

The Civil Rights Movement had spread into basic industries.

Black steelworkers from Birmingham, Ala. to Lackawanna, N.Y. and Baltimore took “accountability for their own lives.”

They didn’t always fight alone. One of my proudest recollections was accompanying 300 coke oven workers, mostly senior black workers from the hell hole of the mill, but accompanied by a notable infusion of more recent hires, many of them white guys who had come home from Vietnam.

Decked out in overalls and safety shoes, they blew through the doors and security of the Shoreham Hotel in Washington where their union leaders were meeting to demand support in winning cleaner conditions and higher incentive pay. And, after a brief wildcat strike when they returned home, they won.

Skilled jobs had been off limits to black workers for decades. For a time, while attending the local community college, I interviewed some of these co-workers as part of a co-op curriculum toward my paralegal degree.

Their stories were heart-rending. A Korean War veteran related how he worked as a plane mechanic in the Air Force, but was flunked when he took the millwright’s test at the Point, even while less-qualified whites entered that department.

So he became a laborer, stacking up ungodly hours of overtime on man-killing assignments to equal and surpass the paychecks he could have made had he been able to move into a skilled position.

I’ll never forget the words of Francis Brown, one of the leaders of Steel and Shipyard Workers for Equality, a leading organization of black workers at the Point:

“When a white guy needs an electrician or a plumber, he calls his brother or brother-in-law,” said Brown. “Black workers call the white contractor.”