Grounded in the Movement: Developing a Mindful Orientation Toward Social Justice Work

By Katy Fox-Hodess

The following article first appeared in the Spring 2015 issue of Tikkun

I recently received an infuriating email from a man I used to organize with in my labor union. The email had all the hallmarks of his habitual way of interacting with other organizers (and especially women organizers): arrogance, condescension, and a steadfast belief in the superiority of his own opinions. This time, I simply clicked the delete button and moved on with my day. But it got me thinking about how, a few years ago, an email or interaction of this kind would have set me off on a cycle of intense anger, frustration, and exhaustion that sometimes verged on burnout, before I became more committed to developing a mindfulness practice.

Mindfulness as a secular practice draws from Buddhist teachings and encompasses a range of activities—from meditation to breathing exercises to therapy—meant to help practitioners develop greater insight into themselves and the world around them. In the San Francisco Bay Area, mindfulness practice has become very popular among a wide range of left movement activists, helped in no small part by the work of organizations like the East Bay Meditation Center in Oakland and the Buddhist Peace Fellowship in Berkeley, which share an explicit commitment to radical social justice work.

While mindfulness practice has recently received media attention for its increasing use in corporate and military circles to sharpen concentration, far less mainstream attention has been paid to its use by radical social justice activists seeking ways to make their movement work more personally sustainable. What follows is a short and by no means comprehensive list of some key mindfulness concepts that have helped me develop a more sustainable relationship to movement work over the past ten years.

1. Don’t turn away from suffering.

Many social justice activists have already taken on one of the central tenets of Buddhist mindfulness practice: a willingness to recognize the enormous amount of pain and suffering in the world and a refusal to turn away from it. Rather than distract ourselves with all of the sensate pleasures that surround us in this intensely materialistic society, we’ve chosen to sit with realities that are deeply painful and disturbing—realities of economic inequality, racism, misogyny, heterosexism, xenophobia, war, imperialism, transphobia, ecological disaster, and more. This is not an easy thing to do, and so the other aspects of mindfulness practice can serve to help sustain activists through the difficulties that arise from our refusal to turn away from pain and suffering in this world.

2. As much as possible, try not to let anger consume you.

It almost goes without saying that anger is a healthy emotional response to all of the systemic injustices we encounter on a daily basis. We feel angry when our dignity or the dignity of people we care about is affronted or when those we care about are harmed; this anger is often the initial spark that leads us to become involved in social justice struggles in the first place. Anger can also be a healthy self-protective measure to make us feel a bit more powerful when we are being made to feel vulnerable, as we so often are when we confront systems of entrenched power and privilege.

At twenty-one, in my first job as a young organizer, I was responsible for organizing direct actions to confront the CEO, board members, and top managers of a factory where the workers were trying to unionize. My work week moved between meetings with workers, at which I listened to their stories of harassment on the job and struggles to make ends meet, and visits to the affluent communities where the people responsible for the workers’ oppression and exploitation enjoyed privileged lives. Key worker activists who publicly supported the union were illegally disciplined or fired. Many others lived on the brink of poverty.

The anger I felt at their treatment by the company and at the fact that this is permissible in our society was palpable, fierce, and constant. Ultimately my anger came from a place of fear and guilt that I would not be able to do enough to improve their situation. This propelled me to push myself harder than I ever had before, in ways that helped the campaign and helped me grow in the process. But we were in a losing battle against a powerful and intractable opponent. No amount of greater effort on my part alone would have been enough to turn the tide. I’m grateful for the experience, which profoundly shaped my life trajectory, but I can see in retrospect that I did not make enough room to deal with my anger, fear, and guilt in difficult organizing situations. As a result, I ultimately suffered severe anxiety and physical health problems—in other words, burnout.

At the time, I thought that righteous anger and a willingness to give everything one had to the work were what made an organizer great. Now, nearly a decade after my first experiences working in the labor movement, I can see how limited and damaging this view was. I’ve come to see that, though I believe we have every right to be angry—for the systems and individuals we’re fighting certainly deserve our righteous anger—we ourselves don’t deserve to be consumed with anger all the time.

Finding the right balance with anger is not easy, but I’ve learned over time to simply let myself be angry when I’m angry, and then let go of anger when it’s ready to pass. When I was younger and anger was my only shield against feelings of fear, powerlessness, and guilt, I used to try to hold on to it, as I think many young people in social justice work do. But though feelings of fear, powerlessness, and guilt no doubt will always recur for activists, no matter how long they’ve been in the movement, I’ve observed over the years that the best organizers I know and the ones who are least susceptible to burnout—are also the least angry. The remainder of this essay focuses on some of best methods I’ve found for getting beyond anger as an activist to develop a healthier and more sustainable orientation toward movement work.

3. Make space for the pain underneath the anger and make care work central.

Too often in activist circles, we cultivate an ethos that makes righteous anger acceptable but doesn’t provide space for individual and collective healing and care to address pain and suffering. This is a point that has been made many times over by feminists doing social justice work, but it always bears repeating. Movement work can be intensely painful and even traumatizing (for example, when it involves confrontations with the police or the law) and is often motivated in the first place by experiences of oppression, exploitation, and trauma. Of course, personal healing is not “enough” to transform systems of oppression, but if we don’t make the time and space to care for ourselves and our comrades, it’s very difficult to find the strength to continue doing the work of confronting injustice. We don’t need to choose between interpersonal work and broader structural transformation: we must do both.

4. Learn to be less reactive and accept impermanence in order to cultivate a sense of equanimity.

Doing social justice work often requires dealing with a nearly uninterrupted series of urgent or emergency situations. The normal human response to emergencies is fight or flight—our adrenaline spikes, providing us with short-lived extra powers to deal with the situation at hand. But we’re not built to experience this sustainably, on a regular basis—afterward, we feel depleted, off-balance, and in need of rest. So doing this work for the long term requires finding more sustainable ways of responding physically and emotionally to intensely stressful situations.

Mindfulness practitioners often refer to this kind of adrenaline-driven response as being “reactive.” The answer is not failure to react when a situation arises—as activists, we have no choice but to respond to injustice—but finding a way to react that does not so deplete us such that we’re unable to sustain ourselves in the work.

A whole series of mindfulness exercises focused on becoming more attuned to our bodies and the physical connection to our emotional state are particularly helpful for learning to become less reactive (as well as becoming more attuned to, and able to sit with, feelings like anger and pain.)

Perhaps inevitably, we also develop a greater sense of equanimity in movement work simply through accumulating more experience as activists. Over time, what I’ve come to see is that, even though things are difficult much of the time in movement work, the worst-case scenario usually doesn’t pan out, and even when it does, we have no choice but to find new ways to organize around it. Learning to respond to difficulty without a supercharged shot of adrenaline is critical, not just for sustaining ourselves as activists but also for finding the best solutions to evolving problems.

Conversely, even when things are going well in the movement, we never reach the end of the work. There is always more to do, and dynamics are constantly changing. Movements are called movements for a reason: they are constantly in motion, and whatever the current situation may be, for good or for bad, it is impermanent. Accepting this central truth about the work (and about everything in life, of course) makes it easier to develop a greater sense of equanimity in charged and constantly changing situations. Resisting the temptation to fuel ourselves on the highs that come from wins is the flipside to resisting the temptation to fuel ourselves on anger.

5. Foster a sense of community with comrades and others who support the work you do.

An absolutely critical aspect of learning to be less reactive in movement work is developing a strong activist community. For those of us who are seeking to make social justice work sustainable, there is no better thing we can do than to cultivate a sense of community with our comrades. The work itself can be incredibly intense—anxiety-provoking, depression-inducing, and isolating. Without a like-minded group of caring people around us to offer mutual support, it may be nearly impossible to sustain our work in the long term.

Social justice groups are, of course, not immune to the problems of the larger society, and highly toxic dynamics can develop. Sometimes we need to take a break or leave altogether when faced with an unchangeably toxic situation in an activist setting. If leaving is not an option (for example, in the context of workplace or neighborhood-based organizing), we can still find new people within the same community to organize with.

On a related note, wherever possible, it’s important to hold on to relationships with non-activists who support the work we do and to maintain some interests outside the movement. When things are not going well in the movement, these non-movement friends can help keep activist struggles in perspective.

6. As much as possible, try to keep your ego out of the equation.

Being a social justice activist means accepting that things will go badly as often as, or more often than, they go well. As a result, we can’t count on getting a lot of external approval or even recognition for the work we do. Even when things are going well, there are still many people who disagree with us: that’s the whole point. So in order to make movement work sustainable, we have to find a way to really make it about the movement and not about our own egos. This doesn’t mean being a martyr, but it also doesn’t mean doing the work in order to feel important or be praised.

It helps me to start with the following premise: on one hand, I am just one person and I’m not responsible for fixing everything, but on the other hand, I am still one person with something to contribute—because everyone has something to contribute. The trick is to figure out just what that thing is and to balance it with other people’s contributions. We don’t need everyone to be in the spotlight to make a big impact, and in fact, the most important movement work always happens outside the spotlight. It’s the day-in, day-out stuff that makes the difference in the long run. It’s very unlikely that everything will just fall apart if one person needs to step back. And, in fact, if things were to fall apart just because of one person’s absence, there’s a much deeper problem there that’s bigger than one individual’s ability to solve it.

7. Remember that it’s all connected and that you always have more to learn.

Because of the way that social justice work is often organized, along single-issue lines, it’s easy to forget that all our struggles are connected. Intersectionality, which recognizes the multiple, overlapping layers of oppression and privilege that each of us experiences, is a helpful tool for thinking through our connectedness. Divide and conquer is the oldest trick in the book, and unless we can find ways to deal with internal oppression and divisions in our movements, the forces of oppression and exploitation will keep winning. It’s a question of the pragmatic realities of organizing as much as it is a question of principle.

This is yet another reason it’s so important to keep our egos in check in movement work and to learn to really listen to comrades with different backgrounds and experiences. Assuming that any individual can have all the answers is both damaging and wrong. More fundamentally, the really liberating thing about doing movement work is not just fighting for liberation itself but also the experiences we have along the way: collective process and collective action can be powerful antidotes to the alienation we experience, individually and collectively, in our daily lives.

Ultimately, both movement work and mindfulness practice share not only a commitment to stringent intellectual honesty when it comes to the nature of our lived reality but also a profound commitment to radical love and compassion for the people around us. Together these values can provide us with a great deal of meaning and purpose in a world that too often leaves us feeling empty and alone. In other words, social justice work, when done in a healthy and sustainable way, can be profoundly therapeutic, not only for our communities but also for ourselves.

Two Rubes in Gotham in ‘67 – Extra Innings Revisited

By Peter Olney

On Friday night I got home at 10 PM Pacific Time to my house in San Francisco. Just in time to dial up my beloved Red Sox playing the Yankees in the Bronx in the top of the 17th inning. The Sox didn’t score and I went to bed. I googled Red Sox Nation next morning and found that they had won in 19 innings on a dynamite double play initiated by Red Sox stellar second baseman Dustin Pedroia from Woodland, California. This game was the longest, 6 hours and 49 minutes in the very long rivalry between the Bronx Bombers and the Bo Sox. But it is not the longest game in innings between the two teams. I was at the longest game; a twenty-inning marathon on August 29 and the following wee AM hours of August 30, 1967.

We were after all both suburban boys, and not real attuned to rustic customs and mores. We were able to bond with Jack over the Sox however.

First though a little background for non-fans and Sox die hards alike. I will always remember the summer of 67 as the “Impossible Dream” season when the Sox climbed out of mediocrity and against all odds won the American League pennant. It was also the summer between my sophomore and junior year in high school. To make some summer money and to prepare my self physically for football season, I worked on Earl Foster’s dairy farm in North Andover, Massachusetts. Mr. Foster had 150 head of Ayrshire milking cows and he and his wife Bea managed the farm and employed two year round hired hands, Earl and Jack. Earl Woods was a wizened old Down-easter who spoke in gruff barely discernible tones and smoked a smelly pipe. Jack Hamill was a young Vermonter who had grown up on a farm and had been indentured to the Fosters. I worked on the farm picking up bales of freshly cut grass and loading them on a truck to be delivered to the cow barn. Then I sat up in the boiling hot barn receiving the bales on the conveyor and dovetailing them together into neatly packed rows to be stored for winter consumption.

Earl Foster needed more help that summer so I recruited my older cousin Mark to work with me. We worked as hard as we ever have, and we were covered with sweat and hayseed at the end of the day. Foster regaled us with barnyard tales and used a lot of animal metaphors to describe common human activity. Bea fed us steak with killer potatoes. My cousin sheepishly asked one day to gales of laughter from all the hands, “What do the bulls do?”

We were after all both suburban boys, and not real attuned to rustic customs and mores. We were able to bond with Jack over the Sox however. He was a huge Sox fan, but had never been to the bandbox of a stadium in the Fens. My cousin Mark and I were big sports nuts and had been to Fenway Park before so we invited Jack Hamill to join us in seeing a game. We decided that we would go to Fenway for a night game on Friday, August 19th. Earl Foster agreed to milk the cows that evening so Jack could escape early and drive in to Boston with Mark and I.

Turns out we picked a very historic game. Jack Hamilton of the Los Angeles Angels beaned the Red Sox slugger Tony Conigliaro, Tony “C” to the Fenway faithful. Conigliaro was a local hero from the North Shore and had played at Swampscott High School and signed with the Sox upon graduating. He was what we call today a “four-tool player”: hit, slug, field and run the base paths. He had led the league in homers with 32 in his second season in 65 and was an All Star in 1967. That night a Hamilton fastball caught him high and tight and his cheek was shattered. While he would return and play again for the Sox and the Los Angeles Angels he never regained his all-star form. Tony C would die young from the kind of head trauma after effects that so many pro-football players are experiencing in the 21st century. The beaning put a big damper on the evening, but Jack was still happy to have been there, and Mark and I felt pretty worldly for having taken him to the Hub.

Later that summer after finishing our work at Fosters farm, my cousin and I decided it was our turn to go to Gotham, New York City, home of the hated Yankees to see the Sox play in the closing days of a wonderful season. We chose Monday August 29th to see the Yankees at the “House that Ruth built” in the Bronx. My Uncle John and Aunt Fran hosted us at their apartment in Tompkins Square in the East Village, and we trained out to the game, a day night doubleheader, on the IRT, the New York inter borough subway. Day night doubleheaders are extinct in this day and age, but we got to the ballpark ready for a full day and evening of baseball.

Gentleman Jim Lonborg, the brilliant Stanford educated pitcher who would win the Cy Young in 1967 pitched for the Sox in game 1. He won 2-1 and completed the game striking out two in the ninth, throwing as hard as he had in the first. The second game made history. It went on and on into the evening and the night. Around midnight my cousin and I started to sweat it. In Boston the MTA closes down at around 12:30 so we figured we were stranded in the Bronx if the game continued, but we decided to stay and were comforted by watching the IRT elevated train zip by beyond the center field fence throughout the game. We didn’t know the NYC system ran all night. The Yankees broke through in the 20th inning on a single by Yankee center fielder Horace Clark off Red Sox pitcher Jose Santiago and won the game 5-4. We got back to Tompkins Square circa 4: 00 AM.

The record of time duration was shattered on Friday April 10-11, 2015, but the inning totals from 1967 remains a record and my memory of the old Yankee Stadium and watching that IRT train is clear. The magical season of 1967 went from summer into late fall. On Saturday, September 30, my high school football team was playing the Tufts College Freshman team in Medford, Massachusetts. I was standing in the huddle listening to our quarterback call the next offensive play when the spectators filling the bleachers on both sides of the field exploded into clapping and uproar. Wow, we hadn’t even run a play, and they were going bonkers. But there was no gridiron action to observe. The Sox had beaten the Minnesota Twins. All the football fans were glued to their transistor radios and listening to the Red Sox broadcast. The Sox would beat the Twins again on Sunday (There were no divisions then) and moved on to the World Series against the St Louis Cardinals.

That was a summer of resurgence for the lowly Sox who despite losing to the Bob Gibson redbirds in the World Series would go on to great heights and great disappointments in 1975, 1978 and 1986 before finally breaking through and busting the curse of the Bambino in 2004. Who knows what would have happened if the brilliant Tony Conigliaro had not been beaned on that Friday night that my cousin and I took a Vermont farmhand to the park?

Cataloging as political practice

By Lincoln Cushing

“Looking back, immediately behind us is dead ground. We don’t see it, and because we don’t see it, there is no period so remote as the recent past. The historian’s job is to anticipate what our perspective of that period will be.” Professor Irwin in The History Boys, 2006.

The “recent past” that has occupied my own current work is the long 1960s. I came of age in Washington, D.C. between 1968 and 1972, diving deep into a profound social movement as only a naïve and invincible high school student can. I went to major demonstrations and fought with riot police. I went to Mobe Marshal trainings with my sister. I helped put out our underground student newspaper. I counseled students about draft resistance, saw grainy films about Vietnam, and made my own poster about the generation gap. I lived it, I knew it – right?

Wrong.

I began to realize how shaky our historical foundation was when I was visiting Cuba in 1989. I was with some other artist friends visiting OSPAAAL, the legendary Organization in Solidarity with the People of Africa, Asia, and Latin America. I knew of them as the publishers of fantastic political posters, and I asked them how many different titles they had produced. I was shocked when they said they didn’t know. That got me motivated, so I began to work with a colleague in the U.S. and we tracked down all known OSPAAAL posters, shot high-quality slides of them, then proceeded to research who made them and when. After several trips to Cuba, lots of faxes and late night calls, and countless hours of work, by 1996 I finally compiled the first catalogue raisonné of OSPAAAL’s output. I shared this with the Cubans in the then-new digital format of CD’s. For the first time, a poster image could be immediately paired with artist name, date of publication, country represented, and other major data points.

The value of this research was evident several times over; at one point I was asked to provide digital prints of Che Guevara posters from U.S. collections that the Cubans themselves no longer had. I realized that I was onto something.

As I became a politicized human being I adopted the practice that part of daily life includes “political work.” That can mean staffing a bookstore, or running a printing press, or writing an essay. I’ve done all of those, but my primary contribution now is as a professional archivist.

In the old days – e.g., over 20 years ago – an archive was usually a staid institution that was responsible for stuff – books, photos, correspondence, videotapes, and such. Access to that stuff for research was often tedious, the result of a meticulous and expensive set of processes involving many library and technical professionals.

That scenario has changed considerably, and it’s transforming what an archive is, how it’s run, and how it’s accessed. The OSPAAAL catalog described above is an early example of that shift, with important implications for scholarship in social justice studies. A democratization is taking place in archival practice.

Here are some of the key elements of this archival revolution:

1. Inexpensive digitization. Images beg to be seen as clearly and completely as possible. When I first started this kind of work the archival standard for 35mm slides was Kodachrome 25. It was very stable, had good color balance, and most importantly, had very fine grain. That’s important when you blow up a poster with tiny type. But just as silver-based film began to slip from the scene, it also became clear that simply having good slides wasn’t enough. At some point they needed to be digitized, and that additional step also took a toll on resolution. Big institutions were able to jump on the high-resolution digital bandwagon early, but at a high price. The cameras were expensive and slow, and a good image would cost as much as $25. Around 2002 affordable consumer cameras became available that produced digital images as sharp as the scans I could get from scanned slides. I bought one and never looked back. I now shoot thousands of crisp images and don’t worry about the cost.

High-resolution scans fulfill several functions in this new archival world. First, a really good image can be used to make very acceptable and affordable digital surrogates that can be passed around a classroom table or mounted for an exhibition. Second, and perhaps more revolutionary, the images can be easily shared globally. I can send an image or a Web link to a scholar instantly anywhere in the world for free, asking if they’ve seen it.

2. Embedded metadata. Geeky enough for you? All this means is that it’s easy to add content information to a digital photo. You already do this now and don’t know it – your cellphone photos are time stamped, and some settings even record location. Ramp that up when you are scanning a conventional print on a flatbed scanner – who shot it, where was it, where is the original photo. These are all vital parts of the puzzle, and are best captured at the moment of digitization.

3. Consumer-grade image databases. For the past 15 years I’ve used an off-the-shelf, cheap, powerful digital asset management system that was originally designed for stock photographers. I can keep track of thousands of images, create galleries based on research requests, add data (and import the data along with images I import, taking advantage of item #2 above), export images at smaller sizes, and produce mini catalogs. Major institutions use very big, expensive databases that are way beyond the range or skill level of ordinary civilians, but that gap is vanishing.

4. Efficient processes for cataloging. Here’s an example of how what I do could not have happened a short time ago. I’m handling a long-term project of building out good catalog records for a huge collection of social justice posters at the Oakland Museum of California (OMCA). First, I shot all 24,000 of them, before the collection even was turned over to the museum. The next step was a crew of initial staff entered basic obvious information about each item as they were physically processing each poster – size, medium, full text, and so forth. My job involves pulling up those records and correcting/amplifying them – when was it made, who made it, why should one care about the ten-year community struggle for the International Hotel – all without looking at an actual poster. This is a process that goes a lot faster when you don’t have large and fragile sheets of paper all over your desk. At some point I’ll be able to do it remotely. One could even have an offsite team doing this.

And – here’s where I feel like I’m living in the future – as I’m cataloging each item I can readily use the enormous power of the World Wide Web. Having trouble nailing down when it was printed? (You’d be surprised how often we don’t know the date of publication, and in the historical record, that matters). Between a reverse calendar for day/date concordance and some event searching, I can usually draw a year. Who was that obscure labor leader, or in what year did Patty Hearst rob that bank? Keystrokes.

5. Community building. The best part is asking questions. Sometimes during a single cataloging session I can identify a person connected to the poster, track down an email address, send them a query with a link to an image, and get a reply. Here are a few examples:

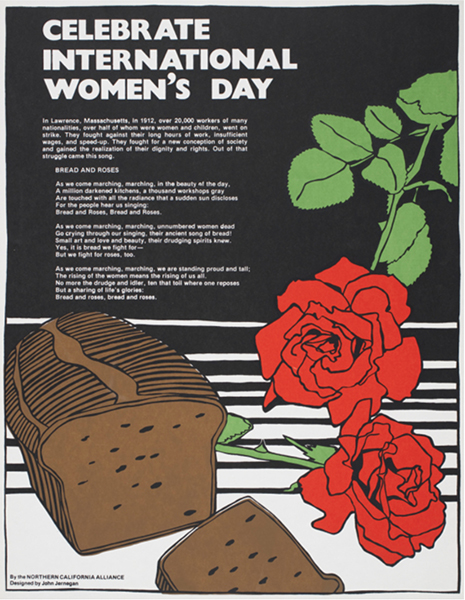

Your question of the year the Bread and Roses poster was printed has sent me down memory lane (not that it is very clear anymore). I started reading many interesting histories of the period that have refreshed my memory a little. I think you are right that it was 1977; probably for the Women’s Day celebration that year. I think I used the graphic in our newspaper, Common Sense so I will see if I can locate a past issue to verify.

Best regards,

John Jernegan

Oakland, California

![Query to Jess Baines [a British poster scholar I know] Reply: “I'll ask the model!” Reply from her contact: (Pru Stevenson): From the 'wife': "1981 it was in response to the Prince Charles and Diana wedding we also did Don't Do It Di stickers."](https://stansburyforum.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/YBA.jpg)

Query to Jess Baines [a British poster scholar I know]

Reply: “I’ll ask the model!”

Reply from her contact: (Pru Stevenson):

From the ‘wife’: “1981 it was in response to the Prince Charles and Diana wedding we also did Don’t Do It Di stickers.”

What an interesting email.

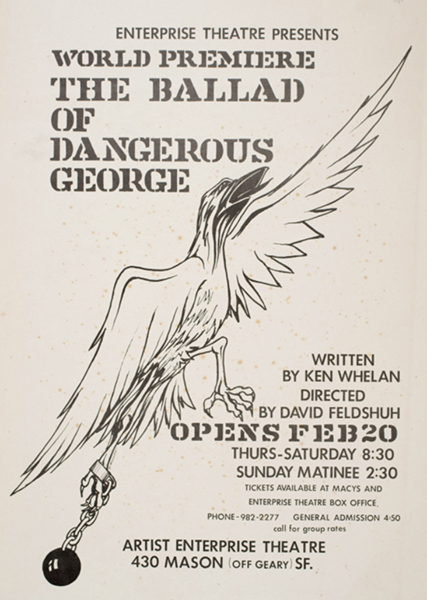

I don’t exactly remember the details but what I can remember from that far off time that might be of interest:

The play was written by an ex-convict from San Quentin. It was based on George Jackson, and 1974 was what I remember.

It was performed at a time of heightened racial tension in SF; specifically, the “Zebra” killings. The cast was roughly half white, half African American and we did various exercises to capture the feeling inside the prison within the rehearsal process; it became uncomfortable at times because the outside world felt just as racially charged when you walked out of the theater. George White, I think I have his name, was one of the leads and became a successful actor in SF; an excellent actor.

That’s more than I thought I could remember; hope this helps.

David Feldshuh, professor, Theater

Cornell University

6. Improved access to collection content. It’s very hard to share physical collection content with researchers. Not only does it have to be seen on site, but it usually requires the work of several staff and the exposure takes a toll on the object itself. Digital representations of content, however, have none of those limitations. Researchers from the public can usually find what they want through searching the database and retrieving usable items. This does not replace the skill and expertise of a professional archivist, but in most cases it’s good enough. OMCA has put almost all of the posters I’m processing online, some with incomplete or inaccurate records, under the policy that “best is the enemy of good.” Digital records can be easily fixed, and several important facts about posters have resulted from the public seeing items online.

So, how does this affect our own knowledge of our own history, much less help share it with the world? Hugely.

In the course of my cataloging research I’m digging into events that, in most cases, have not entered the digital domain yet – and perhaps never entered the analog one either. I’m turning up artists of previously anonymous posters, compiling complete collections of digital items that do not exist together in real space, and confirming production dates so that we know which event happened before or after that one. I’m assembling facts that are the building blocks of our history. These online catalogs are used by artists, academics, and activists for inspiration, confirmation, and validation.

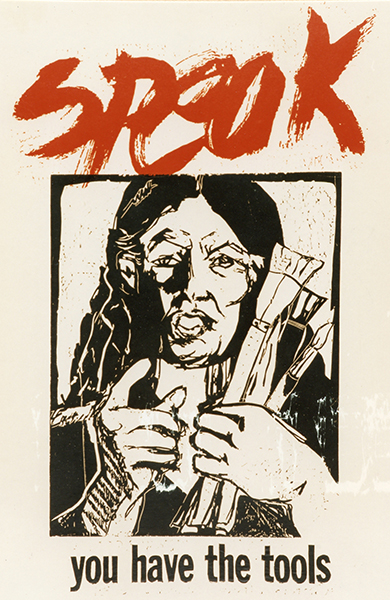

I’ll end with one of my favorite posters about social justice self-expression, “Speak! You have the tools,” the first poster printed by the San Francisco’s Noe Valley Silkscreen Collective, 1972. The graphic was by Carol Mirman, a student at Kent State who was present during the tragic 1970 National Guard shooting. The people have spoken, and now we finally have the tools to really share those messages with the world.

Welcome to San Francisco! – The Jimmy Herman Memorial at Pier 27

By Peter Olney

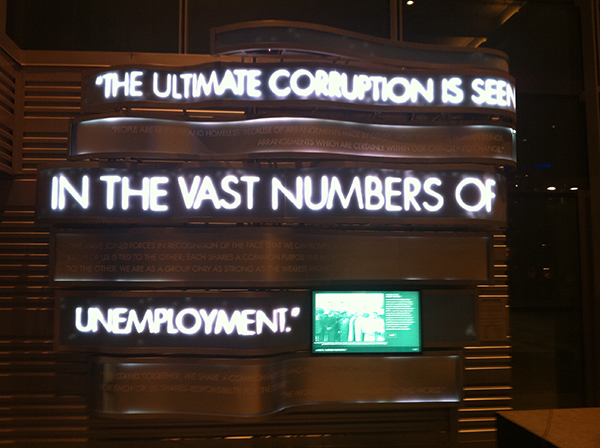

Passengers disembarking from luxury cruise ships at San Francisco’s Pier 27 will be greeted by radical commentary on unemployment, housing shortages and racism delivered in multi-media and interactive fashion by a wonderful piece of public art, called the James R. Herman Memorial Wall Sculpture. The whole terminal is dedicated to Jimmy Herman, a legendary San Francisco leader who was President of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU) from 1977 until his retirement in 1991. Herman had big shoes to fill. He succeeded the legendary Harry Bridges, a founder of the ILWU and its 1st President who served from 1937 until 1977. Herman did not live in Bridge’s shadow however when it came to oratory and his vision of the ILWU as part of a broader labor and people’s movement. He had a powerful voice and delivered compelling speeches in three-piece suits wearing his trademark coke bottle thick glasses.

On the evening of March 26th a ceremony was held in the new cruise terminal to dedicate the wall sculpture. Tides of Change was unveiled to the public by a cast of labor, political and community dignitaries headlined by ex San Francisco Mayor Art Agnos, who led San Francisco through the trying times of the 1989 earthquake and who was a tenant in Herman’s house on Portrero Hill when he first arrived as a young man in the city decades ago from Springfield, Massachusetts. Tides of Change is a multi-media exhibit with interactive video and film that profile Herman’s life in labor. The surface is an undulating wave that carries some of Jimmy’s most memorable quotes in neon lights: “Racism runs deep in this country. We must be committed as a union in the struggle against it.”

I can only imagine an elderly retired couple from Middle America coming down the escalator after leaving their cruise and being confronted with Herman’s social commentary. To paraphrase Dorothy, “We are definitely not in Kansas any more!”

The exhibit is designed by an art collective based in Brooklyn New York, Floating Point. The artists are Genevieve Hoffman, Jack Kalish and Gabriella Levine. Their work needs to be seen by all San Franciscans and all visitors to the well-traveled Embarcadero. It is one of the most stunning examples of political public art that I have ever seen. It is on a par with the Museum to the Martyrs of Liberation in Algiers, which I visited in October of last year.

We however have a problem. The exhibit is inside a cruise terminal that is only open when a cruise ship is in, and then only to terminal workers and cruise passengers. The Port of SF also advertises the facility for public events; mostly corporate galas also not open to the public. The Port of San Francisco needs to open this art to the public with a regular schedule. It is too critical to the education of the SF populace. The origins of the City as a Port city not a high tech playground need to be understood and the inspirational life of James “Jimmy” Herman cannot be forgotten. Visit Pier 27 to see the exhibit and if it isn’t open call your County Supervisor so that we can get regular hours and public access.

Jimmy Herman Presente!!! Open the Exhibit to the Public!

Why Jesus “Chuy” Garcia Should Look to Anton Cermak’s Chicago Mayoral Campaign for Inspiration

By Peter Cole

The parallels between Cermak and Garcia—and Chicago’s political moment in the 1930s and now—are striking.

During his campaign, in 1931, Cermak was told he could not win because of his background. Instead, he turned his heritage into an advantage by effectively organizing the city’s many ethnic groups including Poles, East European Jews, Italians and African Americans—a kind of “Rainbow Coalition” long before similar efforts by Washington and Rev. Jesse Jackson.

When considering Jesus “Chuy” Garcia’s impressive run to become Chicago’s next mayor, many cannot help but make historical comparisons. Understandably, Harold Washington’s historic victory in 1983 springs to mind—not the least because Garcia served as a key Washington ally during those years. However, Washington did not run against a seemingly unbeatable incumbent, nor was he an immigrant.

Perhaps a better comparison is to 1931, when Anton Cermak built the original multiethnic coalition, shook up the city’s entrenched politics and won the mayor’s race. Cermak asserted that the government needed to help ordinary people rather than corrupt business elites and sought to reduce the violence then plaguing the city. Sound familiar?

During his campaign, in 1931, Cermak was told he could not win because of his background. Instead, he turned his heritage into an advantage by effectively organizing the city’s many ethnic groups

Cermak—yes, there’s a street, formerly 22nd, named after him—pulled off an incredible victory by defeating William “Big Bill” Thompson. The parallels to the current election are striking.

Cermak arrived in the United States as an infant with his Czech parents from the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Like most immigrants, they came with next to nothing. First, they lived in a small town south of Joliet where Cermak, just a child, worked with his father in a coalmine. When Cermak was 12, his family moved to Chicago’s South Lawndale neighborhood, home to a large and thriving Czech community—the same neighborhood Garcia lives in today, more commonly referred to as Little Village and the heart of the city’s Mexican population.

As a teen, Cermak worked as a railroad brakeman and teamster, earning the nickname “Pushcart Tony,” before entering politics. He was elected to the state House of Representatives, City Council and Cook County Board of Commissioners before announcing his intention to become mayor. Incredibly, Garcia also was elected to the state legislature, City Council and County Board.

During his campaign, in 1931, Cermak was told he could not win because of his background. Instead, he turned his heritage into an advantage by effectively organizing the city’s many ethnic groups including Poles, East European Jews, Italians and African Americans—a kind of “Rainbow Coalition” long before similar efforts by Washington and Rev. Jesse Jackson. Among Chicago’s diverse working people, Cermak saw himself: fellow immigrants and Americans not represented by entrenched and rich political elites.

Rahm Emanuel looks a lot like an earlier incumbent, “Big Bill” Thompson, who ignored the needs of the people he was elected to serve. Thompson’s reign was so awful that even the Republican Chicago Tribune described his time as mayor as filled with “filth, corruption, obscenity, idiocy and bankruptcy.”

In 1928’s “Pineapple Primary,” for instance, Thompson supporters used hand grenades (“pineapples”) and other violent means to intimidate and literally kill political opponents. After Thompson’s 1928 re-election, gangsters like Al Capone made a mockery of the city and its police—most notoriously in the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre. Meanwhile, most Chicagoans suffered hard times during the Great Depression and became fed up with a mayor who ignored the needs of the people and failed to reduce crime.

While Cermak ran against an actual Republican, the current mayor brazenly acts like one: privatizing schools and parking meters, turning school teachers and unions into villains, serving the interests of big finance and earning the nickname Mayor 1%.

When Cermak challenged Thompson, he disparaged Cermak and, by extension, all immigrants and poor people: “I won’t take a back seat to that Bohunk, Chairmock, Chermack or whatever his name it. Tony, Tony, where’s your pushcart at? Can you picture a World’s Fair mayor? With a name like that?” Cermak’s famous response epitomized many Chicagoans’ feelings: “It’s true I didn’t come over on the Mayflower. But I came as soon as I could.”

There’s telling comparisons, as well, assuming Garcia wins the runoff. After his victory, Cermak faced concerted opposition from the city’s wealthier elements, who fiercely resisted any hikes to property taxes, making it that much harder for the local government to help those most in need during the depression. Along with assistance from the federal government, however, the city was able to reduce economic hardship and put Capone behind bars. (What else Cermak might have done remains a mystery as he was murdered at an event in Miami, Florida when an assassin’s bullets missed their intended mark, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and killed Cermak instead.)

Of course, there are differences between the 1931 mayor’s race and this one. Most importantly, FDR supported Cermak whereas, as Chicagoans know all too well, Obama repeatedly has stumped for Emanuel. And, in 1931, the race pitted a Democrat against a Republican unlike the non-partisan election now, in which both contenders belong to the Democratic Party—even if Garcia, to quote Paul Wellstone, “represents the democratic wing of the Democratic Party” and Emanuel’s endorsements include Republicans Sen. Mark Kirk and Gov. Bruce Rauner.

Let’s face it: With Democrats like Emanuel—who the entire business and media elite along with the Republican Party openly support—Chicago has the most pro-finance, anti-union mayor that Republicans and rich Democrats could hope for. Garcia can inspire Chicago’s many demographic groups that largely have been disenfranchised and taken for granted by Emanuel—who, ironically, inherited the machine that Cermak built.

So what does this history lesson on Cermak offer Garcia and Chicagoans today?

First, Chicago is a wonderfully diverse and cosmopolitan city—a city of immigrants, especially of Mexicans and other Latinos. Garcia should model his campaign after Cermak’s, widely credited with creating the coalition that became the hallmark of Chicago’s Democratic Party. Cermak proved that a multiethnic coalition can win the Chicago’s mayor race, even against a powerful incumbent with the backing of the city’s economic elite. Garcia seems to have pursued such a strategy, uniting many of the city’s grassroots movements and drawing a growing number of endorsements by prominent African-American leaders.

Second and even more importantly, Cermak reminds us that this election is not primarily about electing Chicago’s first Latino mayor. Rather, Garcia—as Cermak (and Washington) did before—must (re)build a cross-class, multiethnic alliance of the working poor and middle classes to shake up a deeply entrenched and corrupt machine.

Whoever wins the mayor’s race will owe a debt to Cermak. If Emanuel wins, he will have had the good fortune of inheriting the political machine built by Cermak. But if Garcia can pull out a victory, then this city’s first Mexican-born mayor will be walking in the footsteps of a now-largely forgotten Czech mayor elected against the odds.

This is a reprint, with permission, which ran in In These Times on 18 March 2015

Olney Odyssey #13. Stay or Pay – Fighting the Runaway Shop

By Peter Olney

In November of 1974 when we met with the Company’s management team and their attorney, Alan Tepper, we had a sense of something ominous. Tepper was a tall slender man with a huge head of silver hair. UE Organizer, Michael Eisenscher was accustomed to call him the “Silver Fox”. Wily fox he was indeed, because while we thought we had got the best of the company in our collective bargaining for a first contract, Tepper had skillfully protected his client’s ultimate interests. Our labor agreement provided that if the Company moved within a 30-mile radius of the Roxbury site that the union and its agreement would be honored. Tepper announced the company’s impending move at the end of the year to Nashua, New Hampshire exactly 45 miles away.

The New England area had been racked by capital flight. Lawrence and Lowell had been decimated post WW II by the desertion of the textile industry to the South. Lawrence has never recovered, and Lowell only experienced a renaissance because of the growth of the University of Massachusetts-Lowell and the federal largess of hometown boy, US Senator Paul Tsongas.

“… but I do know that the question of my own agency has tempered my approach to organizing ever since.”

And New Hampshire shouldn’t have surprised us as the destination. It was the “South of the North” for runaways. Lots of Massachusetts manufacturing capital was seeking low taxes, no unions and cheaper real estate in New Hampshire cities like Nashua, Keene and Portsmouth-Dover. The threat or actual closure can paralyze and incapacitate the will, but our reaction to the company’s announcement was our program of “Stay or Pay”, either stay on Albany Street or within the 30-mile radius or pay dearly in wage and benefit severance. Eisenscher, our resourceful UE Rep immediately began working the politics of the City and the State in seeking locational assistance offers ¬¬and tax packages that would force the Company to reconsider and stay. I took charge of the public pressure campaign and pulled together a committee to Fight the Runaway of Mass Machine, and of course in keeping with the revolutionary fervor of the times to Fight all Runaways!

The shocking announcement of the relocation so soon after our union vote and first contract gave me pause to reflect on a couple of bigger questions. Was the company moving in response to our frequent and militant actions over everything from health and safety to management’s right to employ temps? If we had been a little less active, would they have made the move? Bottom line, were they moving because of me?!! After all here I was a young college educated kid raising hell and Cain in line with my ideological commitment to radical revolutionary change often with no regard to personal consequences. Was that admirable courage and commitment, or rather a sense of entitlement that meant I could always do something else if the job got eliminated? The same wasn’t true for Ernesto from Benevento, Campania, Italia and Juan from Ponce, Puerto Rico, or Eddie Murphy from Southie. I’ll never know the answer to these questions, but I do know that the question of my own agency has tempered my approach to organizing ever since. I’m always trying to check my self out and evaluate whether the strategy and tactics I am proposing are more about my subjective needs than that of the workers I am working with either as a comrade in the shop or as a staff organizer.

Fighting the Mass Machine move became a minor cause celeb in the left labor community that had grown up around UE Local 262. On October 23 we held a rally at the loading dock in the company parking lot in Roxbury. We were joined by a large contingent from the newly organized Cambridge Thermionic Corporation (Cambion). 400 manufacturing workers from this facility had voted UE in July earlier that year. They brought with them signs in English and Portuguese because there was a particularly large Cape Verdean and Azorean workforce. I emceed the rally and Charles Lowell, a UE Vice President and leader of the GE production facility in Ashland, Massachusetts was the featured speaker. Things moved fast after the rally. On November 6 the company announced that the move would happen in January 1975, and later in November they began to lay off the least senior workers. When those lay-offs happened the workers informed us that they had not received the contractually agreed upon Supplementary Unemployment Benefits. We gathered the small group of workers together with our stewards and barged into the executive offices to confront Vice President Jim McGrath about the payment of the differential to the layed off workers. We met with McGrath in his office and demanded the payments that would bridge the difference between unemployment and a worker’s regular take-home. McGrath was so flustered that he panicked and turned to the company safe behind him and pulled out a wad of cash that he proceeded to dole out to the layed-off and anyone else who stuck their hand out, if only we would leave his office immediately.

“I’ll never forget watching a health and safety … explain to a room full of punch press operators that machine oil … could eventually cause sterility in males.”

On January 8th, in the dead of a Boston winter, we rallied on Albany Street at the company’s main entrance. The public pressure was mounting and Eisenscher had successfully gotten the State of Massachusetts to weigh in and show the company several vacant facilities nearby that could be used for manufacturing. The City of Boston even prepared plans, which would provide the Company with land and a new factory built to specification, which then would be sold to the Company and financed with low interest bonds or leased by the City to them. On February 12 the company informed us that they had decided to postpone indefinitely its move. Our mood was one of cautious celebration, but on April 18th, 1975 the company announced that the final day of production at Mass Machine in Roxbury would be July 1, 1975. We held one final rally against the shutdown on June 17th and we did receive a considerable severance package, but the deed was done and the factory moved to New Hampshire. Some of the workers relocated, particularly the Italian immigrants, but most of the workforce had to look for new jobs.

I know that in the final months we openly discussed the tactic of occupying the factory and seizing the equipment ala Flint, Michigan 1936-1937 as a way to deter the runaway. I am not sure why we didn’t. Certainly factory occupations run in the UE gene. In light of Republic Doors and Windows campaign in Chicago in December of 2008 I wish we had. The UE membership in that facility, facing an impending closure, barricaded themselves inside the factory demanding that the company remain open. Their battle became a national story and captured the support of then President-elect Barrack Obama. They were able to find another buyer for the company and keep the plant open. The tactic can resonate and garner broad worker and public support.

Mass Machine was a great learning laboratory for me. Among other things I learned the power of the health and safety issue to motivate workers. I’ll never forget watching a health and safety expert from Urban Planning Aid in Cambridge, Massachusetts explain to a room full of punch press operators that machine oil, if not prevented from splattering on our laps by oil guards, could eventually cause sterility in males. When that was translated into Spanish and Italian the room groaned, and all were immediately united on the need to fight for the UE’s health and safety platform.

Next: Organizing at Advent Corporation in Cambridge, Massachusetts

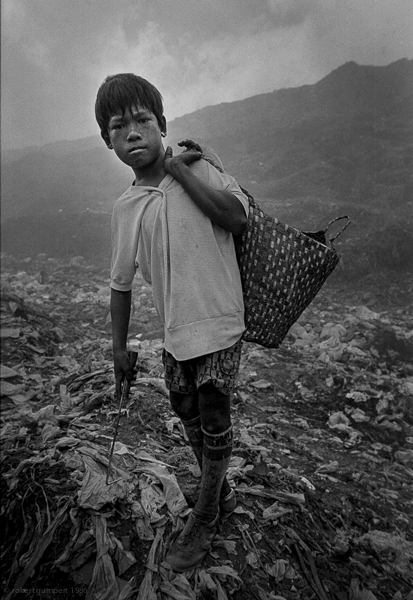

International Day of the Recyclers – Convention March 1

By Peter Olney

Manila, Philippines 1987: Recyclers working on Manila’s Smoking Mountain dump collecting material to be recycled.

May 1 has long been celebrated by the working class world wide as International Workers Day in honor of the Haymarket martyrs executed in Chicago in the aftermath of the national strike for the 8-hour day of 1886. However on March 1 at the union hall of ILWU Local 6 in Oakland, a new International holiday is a specter haunting the emerging “green” economy. March 1 has been proclaimed International Day of the Recycler and was inaugurated in 2008 at a gathering of recyclers from 34 countries in Bogota, Colombia to memorialize the brutal slaying of 10 recyclers in Barranquilla in 1992.

Recycling is the essential green component of the effort to get to Zero Waste, meaning no more landfills. The basic work of the recycler is sorting along conveyor belts extracting different materials like plastic, wood, paper and metals for recycling and often encountering waste, syringes and even human skulls.

Local 6’s recycling membership first met in convention on February 3, 2013 to affirm their commitment to creating a new “standard” for recycling workers in Alameda County. At that convention, 142 workers employed by three different companies, BLT in Fremont, Waste Management Inc.(WM Inc.) in San Leandro, and California Waste Solutions(CWS) in Oakland, united in their resolve to get to $20.00 per hour by 2016. The workers at a fourth company, RockTenn (which has since gone out of business), were also present and inspired their co-recyclers at the other companies with their unfair labor practice strikes that led to a new contract in the summer and fall of 2012

At the time hourly rates at CWS, WMInc. and BLT hovered around $12-13 per hour for the sorter work. Pundits, policy experts, union “leaders” openly derided the $20 per hour goal as unwinnable. Yet after over 2 years of street demonstrations, strikes, political maneuvering, and building alliances in the community, a new standard of 20.94 by 2019 was achieved at WM Inc., BLT and CWS and Local 6 is on the verge of signing an agreement to reach the standard for the newly organized Alameda County Industries (ACI) in San Leandro.

“The political victories were all driven by worker action.”

In the interim the campaign’s leaders, almost exclusively Latina immigrant women, were inspired by the work of the Associacion de Recicladores de Bogota, Colombia and their charismatic leader, Norah Padilla, the 2013 recipient of the Goldman environmental prize. A solidarity greeting was read at the convention from the Colombian recyclers. Shouts of “Si Se Pudo'”(Yes we did!) resonated throughout the cavernous Local 6 hall on Hegenberger Road as workers celebrated their advances. The convention honored politicians from Oakland, San Leandro, Fremont and Alameda who stood with the campaign and mandated franchise increases to cover the tiny marginal costs of advancing the hourly rates to the Alameda standard. Other honorees included Valeria Velasquez, Suzanne Teran and Dinorah Barton-Antonio from the Cal Berkeley based Labor Occupational and Health Program who provided the invaluable health and safety training that liberated the workers to fight for better conditions.

The political victories were all driven by worker action. When BLT balked at approaching the City Council of Fremont to boost franchise fees to cover the standard, workers struck at BLT. When it was time to pressure the Oakland City Council to do the right thing, workers at CWS and WM Inc. struck for a day and camped out in front of City Hall. When WM Inc. workers, the largest group of 130 workers tired of years of delay, they struck WM Inc. for a week despite the Teamster’s official refusal to respect their picket lines.

ACI workers, the newly organized group, braved immigration firings and IBT strong-arming to join the ILWU. All these workers and their families packed Local 6 on the first Sunday in March for International Recyclers Day.

It is refreshing to see a campaign that relies on the united strength of the workers, organized on masse to drive policy and contract changes of significant benefit to them and their families. The Campaign for Sustainable Recycling is worker driven and its power lies beyond any narrative or creative messaging, but in the willingness of workers en masse to sacrifice their sunny Sunday for the greater good. Si Se Pudo!

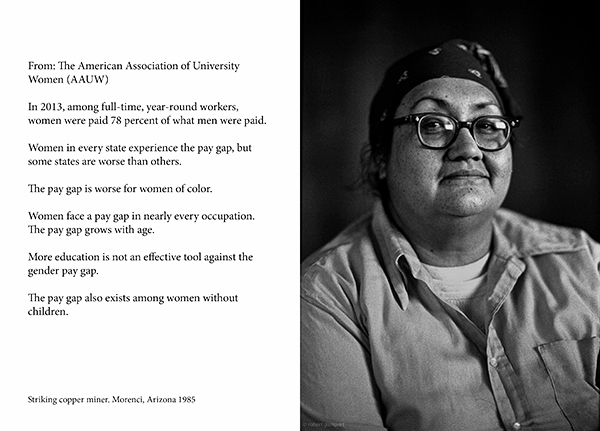

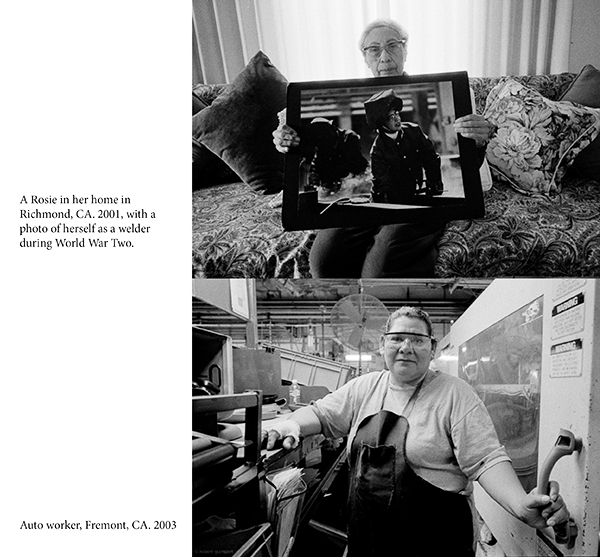

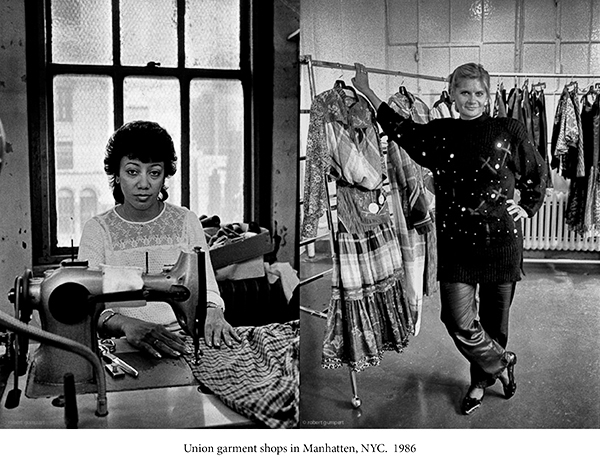

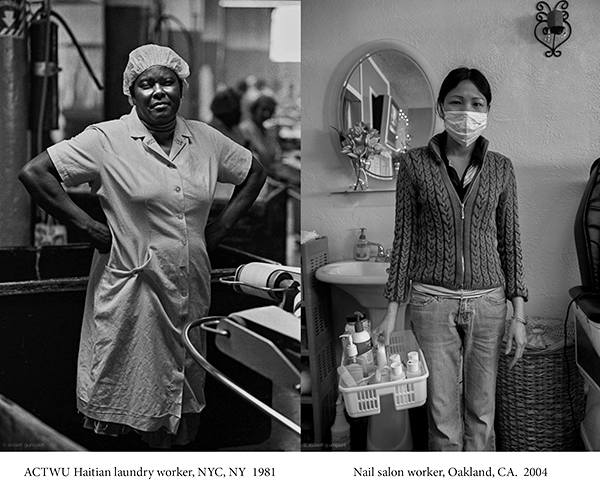

All photos by Robert Gumpert.

Workers

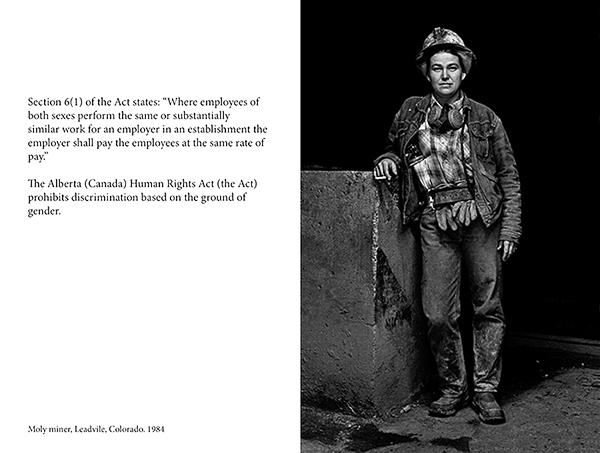

By Robert Gumpert

Over a photo career dating back to Harlan County in 1974 I have always concentrated on labor, work, unions and social issues.

For years I was lucky enough to work for a number of progressive US labor unions, progressive politically and progressive in their view that the union’s publications should serve as an alternative news source to corporate media and not a PR device for leadership.

When that changed, and it did, I moved on to other clients. But my commitment to wanting, as Lewis Hine, the great social documentarian and activist of the early 20th century, “to show the thing that had to be corrected: the things that had to be appreciated” has never changed.

Over the 40 years or so that I have been doing this work my work-life situation has changed numerous times. In January of this year, no longer finding the work justifiable, I declined to continue contract work with my main client and instead have began looking for new avenues, sometimes on old roads not traveled in many years.

In that vein I will from time to time, starting with the collection here, move from behind the screen at The Stansbury Forum and post up small galleries of work and worker photos from my archive. And perhaps, some brand new material as well.

Please note, the work is not free for use.

Olney Odyssey #12 – Big Battles in a Small World

By Peter Olney

With the labor contract settled at Mass machine I was not only able to buy a brand new lime green Ford Pinto, but I got myself a couple more pairs of elastic polyester pants made popular in the 70’s disco theme movie, Saturday Night Fever. One pair I had was my pant of choice in public gatherings, parties and union meetings. It was an alternating plaid brown and black that you might see today on the legs of a cruise ship octogenarian playing shuffleboard. I’ll never forget trying to impress my aunt Amy, who had decided to visit me and see how I was doing. She came to my run down and filthy apartment on Dorchester Ave in Savin Hill . To show her that I was doing fine I proceeded to pull out my ironing board and begin to iron my polyester. I paused to talk to Amy and withdrew the iron. I had burned a huge hole in my best dress pants. The polyester clung to the face of the iron in the shape of the gaping hole.

While my automotive purchase and haberdasher decisions might be called into question, I had done enough right in the organizing campaign and contract negotiations to be selected union shop chairman at the factory. That meant I was responsible for making sure the contract was enforced and representing our small unit at UE Local 262 meetings and at UE New England District Council meetings. The action however was on the shop floor and even though we had signed an excellent labor agreement, the turmoil and battles did not cease.

Visionary leader of the Oil Chemical and Atomic Workers, Anthony “Tony” Mazzochi. (Photo: Robert Gumpert 1981)

1973 was only three years after the passage of the Federal Occupational and Safety Act (OSHA). This was a huge breakthrough for working people and was championed by the visionary leader of the Oil Chemical and Atomic Workers, Anthony “Tony” Mazzochi. (See a biography of Mazzochi by Les Leopold called “The Man who Hated Work and Loved Labor”)

OSHA, although lacking teeth then and now, is a wonderful organizing tool. The penalties are not strict enough and enforcement capacity is limited and often completely lacking but OSHA remains a wonderful organizing tool for a union that is on its toes and has the power to enforce the standards.

We certainly used it that way at MMS. The loud clacking of the metal stamping presses meant that the noise on the floor of Mass Machine was often higher than the acceptable OSHA standard of 90 decibels. We told Mass Machine that it was their responsibility to engineer that noise out of the production process.

The company at a certain point installed a buzzer system with an alarmed door and a Plexiglas window like those at all night convenience stores in a high crime neighborhood.

In April of 1974, the company hired a new Vice President for labor relations, Jim Moran who was tasked with taming the UE juggernaut. Moran approached me and told me that I would have to wear earplugs and recommend that all the press operators wear earplugs. I told him that we wanted the noise engineered out, and that earplugs were not a solution. I said that I would not wear them. He fired me on the spot for insubordination and told me to leave the factory. I passed the word to all the workers to meet in the lunchroom on the second floor to discuss the company’s actions. Just as the meeting started the Boston Police Department entered the lunchroom, called by the company to evict me from the premises. The workers decided that if I was being escorted out that they would all go out with me. The plant was shut down, and we were on the street. Within 2 hours the Company was in negotiations with Mike Eisenscher our UE Organizer and they agreed to put me back to work with no recriminations against the other members, and they would explore the engineering solution to the high decibels. So while we had a grievance procedure that provided for no strikes during the term of the contract I had quickly learned an important lesson. When production is halted and the employer has no effective means of restarting it any time soon, we had a lot of power. This was the first of many episodes of MMS workers flexing their muscles.

In June we struck again. The Company brought in two Labor Pool workers to do our work. They were paying them $2.00 per hour, $.75 below our start minimum, and no benefits. We shut down production and negotiated a $2.75 per hour rate for them for all work they had done and an agreement that the company would not try again to bring in Labor Poll workers.

During that summer of 1974 the workers at Baltimore Brush, a facility adjacent to us on the corner of Albany and Northampton Streets decided to organize into the same union, UE Local 262. Baltimore Brush employed about 65 workers and I knew the main organizer at the “Brush”, a Puerto Rican brother named Julio. As their organizing drive opened up and got more aggressive, the company responded by firing Julio. This was the pre-cell phone era so Julio came over to our lunchroom to tell us what had happened. We rounded up our members from Mass Machine, particularly the Puerto Rican brothers, and we all marched into the Executive Offices at Baltimore Brush demanding Julio’s reinstatement. Two days later he was back, and soon the workers at Baltimore Brush voted in the same union, the UE.

We had a habit of barging into executive offices, a tactic we had employed successfully on many occasions at Mass Machine. The company at a certain point installed a buzzer system with an alarmed door and a Plexiglas window like those at all night convenience stores in a high crime neighborhood.

These were pretty heady times. Young red agitators like me were anticipating big societal change and often intoxicated with our small successes. I think the most amazing moment and the one that pushed the company to a fateful decision was the Bill Buckley incident. Bill Buckley was a popular supervisor who was often supportive of our issues. One night in a Marxist study group I discussed Lenin’s “What is to Be Done” which describers the tasks of communists in a pre-revolutionary period (Guide; Study questions) . He exhorted us to be fighters not only for the interest of the working class but also for the interests of all classes in opposition to the Tsar. Taking this exhortation completely out of historical context, I headed to the factory the next day determined to implement my new understanding. The company chose to fire Bill Buckley. I chose to “fight for the interests of all classes”, and save the job of a low level supervisor, and I led a walkout to protest his firing. We were out on the street and I thought I better call the union hall and talk to our union rep, Mike Eisenscher before the company did and explain the situation. I explained what we had done and he said, “you did what????###%%^^&&! He ordered us back to work immediately.

On November 6, 1974 the company announced that they would be closing in Roxbury and moving to Nashua, New Hampshire sometime in January 1975. Nashua just happened to be outside the 30-mile radius clause (in post #11 the number was incorrectly printed as 60) we had negotiated in our new labor agreement. Nashua was 45 miles away and that meant that the contract and the union would not be going to Nashua with the company.

This decision set the stage for our battle against the runaway.

Olney Odyssey #13 Stay or Pay Fighting the Runway Shop

The Spiritual in the Struggle-Book Review

By Peter Olney

UPDATE:

Victor Narro’s book has recently been translated into Spanish, here is a Spanish version of Peter’s review:

Living Peace: Connecting Your Spirituality with Your Work for Justice (Vivir con paz: la vinculación de su espiritualidad con su trabajo por la justicia), por Victor Narro 2014.

Living Peace, el nuevo libro de Victor Narro acerca del aspecto espiritual de la organización apenas consiste de 100 páginas. Este pequeño volumen aborda un tema que podría provocar sorpresa entre los cínicos en ciertos sectores de nuestro movimiento sindical. Su tesis me intrigó y con afán de ampliar mi propio entendimiento leí el libro y luego reflexioné sobre una reciente experiencia que tuve.

El 24 de enero, Agustín Ramírez, un talentoso líder de organizadores de ILWU en el norte de California me invitó junto con mi esposa a participar en un levantamiento en Merced, California auspiciado por sus padres. Yo había participado antes en las posadas navideñas, pero desconocía lo que era el levantamiento o presentación. Las posadas son un ritual en el que la comunidad va de puerta en puerta por la vecindad cantando villancicos y recreando la travesía de José y María en busca de alojamiento o posada. El levantamiento o presentación del niño Jesús ante el Señor en el Templo se dio 40 días después de su nacimiento y la comunidad también lo celebra el Día de la Candelaria haciendo una procesión para recrear dicho levantamiento. Ambas de estas costumbres son parte de la temporada navideña en América Latina y son parte de la formación de Agustín como organizador. Estas son las conexiones culturales que permiten organizar la base amplia que se requiere en su trabajo en la comunidad de inmigrantes latinos. Merced queda a un mundo de distancia de la zona de la Bahía pero no muy lejos de las vidas de los trabajadores inmigrantes latinos.

“… el sostener el activismo toda la vida por el cambio social requiere más que la estrategia clínica y las exhortaciones políticas”

He tenido el privilegio de participar con Agustín en una maravillosa campaña de sindicalización en el condado de Alameda a lo largo de los últimos tres años. La Campaña de Reciclaje Sostenible ha logrado elevar la dignidad y las tarifas salariales de los clasificadores que espulgan los desechos y basura en correas de transmisión inmundas a tempranas horas de la mañana antes de que la mayoría de los residentes de la zona de la Bahía siquiera se despierte. ¡Los afiliados del Sindicato Internacional de Trabajadores Portuarios y Almacenistas (ILWU) y su Local 6 han logrado aumentar sus salarios hasta conseguir $21.00 por hora para 2019! Todo este progreso para una fuerza laboral que en un 65% son mujeres y principalmente inmigrantes latinas se ha conseguido con una combinación de acciones laborales, huelgas y paros, además de presión política ejercida en ciertas municipalidades tales como San Leandro, Fremont y Oakland, ya que es allí donde se fijan las cuotas de la recolección de basura y reciclaje.

Esta es un historia que confirma que “Si Se Puede” para 300 trabajadores pese a todos los factores en contra. Los encargados de elaborar las políticas, los expertos y ciertos supuestos dirigentes sindicales dijeron que no se podía hacer. Este año los trabajadores celebraron el 1 de marzo los tres años de lucha y sus logros en la Convención del Día Internacional del Trabajador del Reciclaje en Oakland, California. El 1 de marzo fue designado como el Día Internacional de los Recicladores por la Asociación de Recicladores de Bogotá, Colombia. En ese país se celebró el 1 de marzo el año pasado con una marcha en la que participaron más de 17,000 recicladores. Ninguna hazaña de organización de esta magnitud se logra sólo o principalmente con fríos cálculos de expertos en políticas o con las estrategias de los sindicalistas para uso de la palanca política. La organización de gran magnitud como esta requiere de una sublime espiritualidad. Lo recordé recientemente cuando asistí a una reunión del comité directivo de la campaña. Agustín acentuó la reunión y la historia de la campaña con una historia asombrosa de los retos afrontados por una de las mujeres del centro de reciclaje de ACI en San Leandro.

Pero primero conviene dar unos antecedentes. ILWU empezó a trabajar en 2013 con un grupo de recicladores de ACI. A los trabajadores que laboraban allí se les había robado tres dólares por hora por tres años al no cumplirse la ley del salario digno de la Ciudad de San Leandro. Con varias latinas al frente, los trabajadores se organizaron para presentar una demanda judicial para recuperar el pago perdido. La Compañía se desquitó despidiendo a varios trabajadores que no tenían la documentación migratoria en regla. Los trabajadores se pusieron en huelga para protestar por estas represalias. Ellos perseveraron y finalmente se organizaron para afiliarse al Local 6 de ILWU. El Sindicato de los Teamsters, que representaba a los choferes de los camiones de recolección de basura que ganaban mejores salarios, junto con el empleador, trataron de presionar a los trabajadores para se afiliaran a su sindicato. Los trabajadores votaron 49 a 9 por ILWU, lograron un aumento inmediato de tres dólares por hora y resolvieron una demanda judicial obteniendo una indemnización de más de $1 millón, y ahora están a punto de celebrar su primer contrato colectivo que aumentará los salarios hasta cumplir la norma establecida en Alameda de $21 para el 2019.

Ramírez habló de una de trabajadoras de ACI, una inmigrante latina que había sido despedida como parte de la represalia inicial. A pesar de esta experiencia humillante y los sacrificios que representó para su familia, ella siguió apoyando la demanda judicial y la sindicalización. Yo sólo me puedo imaginar el gran valor moral que se requiere para hacer frente a esta sarta de retos, lo cual nos lleva de nuevo al tema de Victor Narro y su refinado libro sobre la vinculación de lo espiritual con nuestro trabajo en pro de la justicia.

La fe espiritual que tiene Narro en “el bien común” es el resultado de su propio trabajo extraordinario como organizador laboral y comunitario en Los Ángeles por treinta años y su estudio de las enseñanzas de San Francisco de Asís y un espiritualista y maestro vietnamita, Thick Nhat Hanh. Living Peace es un manifiesto escrito con elocuencia e ilustrado hermosamente con fotografías tomadas por Narro y su compañera de vida Laureen Lazrovici. Cada capítulo lleva en su introducción una cita de San Francisco, y cada uno termina con preguntas para la reflexión y espacio para apuntes personales. Este es un libro que los organizadores pueden llevarse consigo como acompañante espiritual mientras realizan su trabajo. Esta fina obra de Narro reconoce que el mantener el activismo a lo largo de la vida para hacer el cambio social requiere más que estrategias clínicas y exhortaciones políticas. Ofrece una guía espiritual para los organizadores que se han comprometido con la lucha a largo plazo. Ramírez reflexionó sobre el coraje de una trabajadora de ACI al relatar las dificultades que ella enfrentó, pero esa historia no es singular. La cita que precede el último capítulo de la obra de Narro podría aplicarse a muchas situaciones que se presentan cuando la gente se organiza:

“Al estar rodeado de mil peligros, no nos descorazonemos, sino abramos un espacio en nuestros corazones para aceptarnos unos a los otros.”

Para obtener una copia de Living Peace, favor de comunicarse con Victor Narro en vnarro@ irle.ucla.edu

Living Peace: Connecting Your Spirituality with Your Work for Justice, by Victor Narro 2014

Living Peace, Victor Narro’s new book on the spiritual side of organizing is just over 100 pages long. His little volume is broaching a topic that might raise cynical eyebrows in certain quarters in our labor movement. His thesis intrigued me and in the spirit of self-mindedness I read the book and then reflected on my own recent experience.

On January 24th Agustin Ramirez, the gifted ILWU Northern California Lead Organizer invited my wife and me to participate in a levantamiento in Merced, California hosted by his mother and father. I had participated in “posadas” at Christmas season before, but I was ignorant of the “levantamiento” “Posadas” is a ritual whereby the community marches door to door in the neighborhood singing carols and reenacting the quest of Joseph and Mary for room at the inn, lodging or “posadas”. “Levantamiento” comes 40 days after the birth of Jesus and is also a community procession in which the baby Jesus is raised up and presented. Both these rituals are part of the Christmas season in Latin America and part of Agustin’s formation as an organizer. These are the cultural connections that enable the deep base building involved in his work in the Latino immigrant community. Merced is worlds away from the Bay Area but not from the lives of its immigrant Latino working class.

“…sustaining lifelong activism for social change requires more than clinical strategy and political exhortations”

I have had the privilege of participating with Agustin in a wonderful worker organizing campaign in the County of Alameda California over the last three years. The Campaign for Sustainable Recycling has been successful in raising the dignity and the hourly wage of the sorters who pick through garbage and waste on filthy conveyor belts in the wee hours before most residents of the Bay Area are even awake. The workers of International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU) and its Local 6 have succeeded in raising their hourly wages to $21.00 per hour by 2019! All this progress for a workforce that is 65% female and mostly Latina immigrants has come through a combination of worker action, strikes and stoppages coupled with political pressure in particular municipalities like San Leandro, Fremont and Oakland that set the rates for garbage pickup and recycling.

This is a “Si Se Puede” story for 300 workers against all odds. Policy makers, pundits and certain “union leaders” said it couldn’t be done. This year on March 1, the workers will celebrate three years of struggle and their achievements at an International Day of the Recycler Convention in Oakland California. March 1 was designated Dia Internacional de Los Recicladores by the Associacion de Recicladores de Bogota, Colombia. In that country last year’s March 1 was celebrated with a march of over 17,000 recyclers.

No organizing achievement of this magnitude happens solely or mainly because of clinically detached policy wonks and labor strategists figuring out leverage. There is a transcendent quality of spirituality in this powerful organizing. I was reminded of this when I attended a recent steering committee meeting of the campaign. Agustin punctuated the meeting and the history of the campaign by telling an amazing story of the life challenges of one woman at the ACI recycling facility in San Leandro.

But first a little background. The ILWU started working in 2013 with a group of recyclers at ACI. The workers there had each been bilked out of almost three dollars per hour for three years under the City of San Leandro’s living wage. Led by several Latinas the workers organized to file a lawsuit under the living wage. The company retaliated by firing workers whose immigration papers were not in order. The workers struck and protested against this retaliation. They persevered and finally organized a union with ILWU Local 6. The Teamsters who represented the higher paid garbage truck drivers acted in concert with the employer and tried to bully the workers into joining their union. The workers voted 49-9 for the ILWU, got a three dollar per hour immediate raise and settled a law suit for over $1million dollars, and are on the precipice of a first contract that will bring wages to the Alameda standard of $21 by 2019.

Ramirez told of one ACI worker, a Latina immigrant who was fired in the initial retaliation. Despite this humiliating experience and the sacrifices it imposed on her family, she has remained a loyal supporter of the lawsuit and the organizing. I can only imagine the inner strength needed to face this maze of challenges, which brings us back to Victor Narro and his fine book on connecting the spiritual to our work for justice.

Narro’s spiritual faith in a greater ‘Good” is the product of his own amazing work as a labor and community organizer in Los Angeles for thirty years and his study of the teachings of St Francis of Assisi and a Vietnamese spiritualist and teacher, Thich Nhat Hanh. Living Peace is a manifesto, skillfully written and beautifully illustrated with photographs by Narro and his life partner Laureen Lazarovici. Each chapter is introduced by a quote from St Francis. Reflection questions end each chapter and there is space for personal notes. This is meant to be a book that an organizer can take into the field as a spiritual companion.

Narro’s fine work recognizes that sustaining lifelong activism for social change requires more than clinical strategy and political exhortations. He provides a spiritual guide for organizers who are engaged for the long haul. Ramirez was reflecting on the courage of one worker in his telling of the challenges of the ACI worker, but her story is not unique. The quote that precedes the final chapter of Narro’s work could apply to many organizing situations:

“When surrounded by a thousand dangers, let us not lose heart, except to make room for one another in our hearts.”

For a copy of Living Peace contact Victor Narro at vnarro@irle.ucla.edu