It is human rights.

By Myrna Santiago

Not all violence is equal. The difference matters. A civilian killing another civilian is a crime. A member of the police killing a civilian is an entirely different question, legally and morally. The police and other similarly armed bodies are direct representatives of the power of the state. Their duties and obligations toward civilians are qualitatively different from those of civilians. So are their actions, especially the violent ones. The armed forces of the state (police, FBI, SWAT team, National Guard, on-duty member of the armed forces, and the rest) are legally (and morally) obligated to protect the people of the country. That is their sworn duty: to protect the civilian population.

An armed representative of the state who kills a civilian, therefore, commits not just a crime like any other person. No, that official commits an abuse of power, a violation of human rights. The act itself is called a “summary execution.” The states who fail to stop violence against civilians on the part of their armed bodies are, rightfully so, labeled as violators of human rights. We are all familiar with the states so considered–repressive states that eliminate their political enemies through violent means (detention without trial, disappearance, torture, execution). But political opponents are not the only category of people who fall victim to state-sanctioned violence: historically, members of ethnic or racial minorities have also experienced violence at the hands of the armed bodies of the state. Guatemala between 1954 and 1996 comes to mind. There the military government carried out a genocidal campaign against the indigenous Maya population. Not all violations of human rights rise to the level of genocide. Not every government who engages in human rights violations is run by men in olive green uniforms. That is the case for the United States.

Police departments across the country routinely execute black and brown men in plain daylight. We do not know exactly how long those violations of bodily integrity have been taking place—until months ago, there was no daily video evidence for everyone to see. The African-American community has denounced “police brutality” for decades (centuries, really) but who listened to their voices? Even today, Americans refuse to believe that the country’s armed bodies commit such violence. Or, when the visual proof is impossible to dismiss, they defend the police, assuming the person “must have done something” that somehow forced the police to open fire until death.

American Secretaries of State echoed the denials — …”

But ask the question: Who deserves execution at a children’s park? Who deserves execution at a traffic stop? Who deserves execution for failing to raise their arms high above their heads? Who deserves execution for selling CDs or cigarettes? Does anyone deserve execution for talking back?

There was plenty of denial about detentions, disappearances, torture, and execution in Guatemala too. And in El Salvador. And Chile, Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay, and Paraguay since the 1970s. The elite of every single one of those countries denied their governments violated human rights.

American Secretaries of State echoed the denials — after all, every single one of those governments were US allies in the Cold War against the “evil empire” of the USSR, the state that embodied violations of human rights in the American imagination. That is to be expected. But many ordinary people throughout Latin America made the same argument. If pushed to admit what was in front of their faces, they murmured, “they must have done something.” Because they were not part of the groups experiencing the violence, they refused to accept that their armed bodies were structurally, criminally, systematically violent against Others in their societies. Because their privilege (class, political affiliation, ideological preference, light-skin) protected them from the men with guns, they made excuses for the violence. They supported their armed forces; some even believed the police were the victims. That is where we are in the United States right at the moment. Without a military regime, without the physical elimination of political opponents. No, in the US the armed bodies of the state execute men of color.

But it need not be that way. In contrast to common crime, violations of human rights can be addressed easily. The government knows who the culprits are. They are easily identifiable; they receive a paycheck from the government every month. All the government has to do to stop such behavior is to prosecute the culprits. And here the US can follow the lead of the governments of Argentina, Chile, and Guatemala. All three have made a turn and brought to justice members of their armed bodies for human rights violations. Even if some were abroad in Britain (remember Pinochet?) or Miami and Los Angeles, those governments are investigating and using extradition treaties to make sure those men face trails in the countries where they committed their crimes. By comparison, the US government has an easy task. No borders to cross, no international paperwork to file. Arrest officers responsible for executing civilians. Bring them to trail. And stop letting officers who execute civilians go free. Demonstrate the state is committed to protecting human rights. Because civilian lives matter. Because Black Lives Matter.

_____________________________◊◊◊_____________________________

Living the Life of an Organizer

By Bill Fletcher, Jr.

UFW co-founders Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez with Fred Ross preparing for secret ballot elections at DiGiorgio Fruit Corporation in 1966. Photo: Jon Lewis

The biographies of icons frequently fall into one of two categories. On the one hand they may be laudatory, in some cases turning the subject into a saint. At the opposite end, they can tend towards tell-all pieces, in some cases aiming to tear down the subject. What makes America’s Social Arsonist: Fred Ross and Grassroots Organizing in the Twentieth Century, Gabriel Thompson’s new biography of the legendary community organizer, unusual is that it presents a very balanced account of the life and work of one of the foremost progressive organizers of the 20th century, while at the same time offering very useful insights into the art and craft of progressive organizing.

In many respects, Ross’s life is the story of a significant segment of the progressive movement in California. He came of age politically during the 1930s; witnessing the great agricultural worker struggles of that era which came in the aftermath of the mass deportation of Chicanos and Mexicans in 1930s which came to be associated with the term, “Los Repatriados,” found himself face-to-face with the imprisonment of Japanese-Americans in concentration camps during World War II and his slow but steady emergence as an organizer and theorist within the Community Service Organization (and later, the United Farm Workers).

Maria Duran, CSO & International Ladies Garment Workers Union leader, with Fred Ross during fight to save Chavez Ravine in 1949. Photo: Don Normark

Although Ross and legendary organizer Saul Alinsky were quite close, and Ross actually worked for Alinsky for a period of time, Ross departed from his mentor in two important respects. First, central to Alinsky’s approach to organizing was the notion of building an organization of organizations. Through the Industrial Areas Foundation, locally-based coalitions were put together, frequently rooted in the religious community. This aimed to guarantee some level of credibility for the organizing effort. But Ross disagreed: He believed in the need to create new community-based organizations that were unencumbered by older leaderships who he frequently believed to be too passive or otherwise obstructive.

The other difference is that Ross recognized the importance of the Chicano movement in California and was prepared to engage in struggles that some organizers, influenced by Alinsky, would have concluded were far too divisive. The Community Service Organization, which he helped to build, was rooted in the Chicano movement, though open to others. It fought against police brutality that was directed at Chicanos and attempted to build Chicano political power in Los Angeles.

Although Ross did not present himself as a person of the Left (probably in part due to the Cold War persecution of leftists), his inclinations were clearly toward the Left. He mostly refused to engage in the sort of red-baiting that was common from the 1940s to the 1960s, even among many progressives.

This fact gave me pause. I have been highly critical of Alinsky and those who have followed in his wake for their de-ideologizing of organizing: an approach that suggests that it is almost unimportant what one organizes around; it is the act of organizing itself that raises the political consciousness of those engaged, and raises it in a progressive direction. This de-ideologizing by many of Alinsky’s followers made its way into the ranks of organized labor, particularly in the 1980s and 1990s and played a counter-productive role in efforts at labor renewal.

The Ross described by Thompson appears to have been a somewhat different sort of character. On the one hand, there is no attention to ideology and leftist political education in the organizing that he conducted. In that sense, there is a consistency with Alinsky. At the same time, Ross’s approach, as demonstrated by the sorts of struggles in which he engaged, seems more akin to a sort of “evolutionary leftism,” that through various forms of progressive organizing, we will naturally achieve the kinds of transformations we need as a society—no larger ideology necessary.

Such an approach eschews the importance of movement-wide strategic objectives, rooted in a larger political vision. Nevertheless, this appears to be a difference between Ross and Alinsky that was overshadowed by their close friendship over the years.

The other aspect of Thompson’s treatment that I especially appreciated revolved around the question of family. Ross’s family life was largely tragic. It is not just that his two marriages ended in divorce. Rather, Ross’s approach towards his organizing life was to put organizing before everything else.

At one point in history such an approach would have been considered noble, if not heroic. Yet, in reading about his ignoring his two wives, and spending limited amounts of time with his children (with the notable exception of Fred Ross, Jr. who followed in his father’s footsteps as an organizer), what was striking was both Ross’ sexism and his blindness to the multi-dimensional side to living the life of an organizer. The sexism was especially ironic because Ross made reaching women a priority in his organizing.

Fred Ross speaking at a nightly mass in Delano, California, during Cesar Chavez’s fast in March 1968.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University

In Ross’ era, it was frequently accepted that men could go off and save the world and the women should take care of the home front. We should be careful about judging a past period based on the norms of our current era. Yet one can conclude that, first, there were alternative courses even during that era, and, second, that the cost, not only to Ross’s two wives and children but to Ross himself, were severe.

In social movements there are intense pressures on organizers—paid and unpaid—to put everything else aside in the name of the cause. There are circumstances where that is necessary, if not unavoidable. I am reminded of a South African activist, Nimrod Sejake, who was exiled due to his anti-apartheid work, spending years in Ireland, the result being his missing out on years in the lives of his children. One cannot second-guess such a decision, made under extreme conditions. Yet the decision came at great cost. His family was very divided over whether his sacrifice had been worth it, a very tragic legacy for a person who committed so much for a greater cause.

For Ross, however, the idea of the organizer prioritizing organizing above everything—including one’s family—rose to the level of principle. It was not only about what one might be forced to do under extraordinary circumstances, but what an organizer should be prepared to do at virtually any point. In Ross’s case, this included ignoring his wife during certain key moments when she was recovering from polio.

The failure to recognize the need for a balance of family and a life committed to social justice inevitably led to dysfunctions in the way that Ross thought and operated. The movement became everything, and this meant, at certain key moments—as we would see when Ross worked with Cesar Chavez—a willingness to turn a blind eye to terrible, abusive practices carried out in the name of the movement. Ross failed to question the actions of someone who, even more than Ross, believed that he was putting the movement before everything else.

Thompson also offers an insightful and emotionally challenging look at the development of the United Farm Workers of America. Cesar Chavez, the legendary founding President of the union, was someone who Ross mentored. Over the years their relationship evolved, such that Ross came to not only admire Chavez, but to see him as the leader who could transform American society. This evolution took very tragic consequences when Chavez himself evolved into a leader filled with paranoia, anti-communism, and quite possibly, some level of anti-Semitism, as Randy Shaw recounts in Beyond the Fields: Cesar Chavez, the UFW, and the Struggle for Justice in the 21st Century.

Because of my family. I realized that if things kept going the way that they were going, I would not be part of the lives of my children as they grew up nor be a good partner for my wife.”

Ross witnessed firsthand the deterioration of the UFW, including the purges carried out against outstanding leaders and activists, such as the purging of two great leading figures in the UFW, Marshal Ganz and Eliseo Medina (the latter going on to become Secretary-Treasurer of SEIU), or the manipulation of a key vote at the UFW convention that led to the departure of many UFW activists, feeling betrayed. Yet he said nothing. Thompson proposes that Ross might have been one of the few people who could have successfully challenged Chavez as he descended into Tartarus, taking with him a union that in so many ways pointed in the direction necessary for broader U.S. labor renewal.

Thompson not only tells an excellent story, but he also, at key moments in the book, identifies certain lessons for organizers, drawing from the life and work of Ross. He does not editorialize as to whether he, in every case, agrees with Ross, but the lessons are clear. One example, noted above, was Ross’ awareness that women are generally the best organizers, and that if one wishes to get any substantial project off the ground, one must win over women. It was not clear, however, the extent to which Ross recognized that winning over women was not just about winning them in the initial organizing efforts, but ensuring that they have a full leadership role throughout the process of the construction and life of an organization.

Ross, additionally, promoted the notion of beginning with where people are, then moving them forward, a truism for organizing whether one subscribes to Alinsky or Mao Zedong. The book lists myriad of additional lessons that Ross drew from his own experiences and which he theorized, to varying degrees.

Ross did not believe in the concept of “burnout”. He believed that an organizer is either an organizer or they have given up and dropped out. In reading about this I was reminded of the famous story of the incident involving General George S. Patton—during World War II—where he hit a soldier who was suffering battle fatigue (an incident dramatized in George C. Scott’s remarkable portrayal of the general in Patton).

In both Ross and Patton’s case, there was a misreading of human beings. These were not simply examples of macho, whether applied to organizing or to war. It was a failure to understand how human beings cope with pressure and particularly over extended periods of time. Organizers do burnout. Some of them leave the movement entirely; others return full swing after a certain period; and others ‘renegotiate’ their relationship to the movement on different terms.

A good friend of mine stepped away from a leadership position in a major local union. I asked him why he did this. He replied: “Because of my family. I realized that if things kept going the way that they were going, I would not be part of the lives of my children as they grew up nor be a good partner for my wife.”

Ross might have described such an approach as what we used to call “half-stepping,” evidence of someone who wasn’t fully committed to the movement. I would look at it as more of an adjustment to the simple fact that involvement in the movement is a marathon. This is a long-distance race during which time one’s speed may vary or breathing may change. But one never loses sight of the final goal. Failing to appreciate the multi-dimensionality to the life of an organizer guarantees that instead of building and reinforcing organizers, we produce Blade Runner-type replicants or androids who may, at first glance, appear to be human, but have actually lost their souls.

In many respects, this is what appears to have happened to Ross. Yes, he was without question great and dedicated. But in failing to appreciate the marathon nature of our journey and the need for balance, he began losing pieces of the humanity for which he had actually been fighting for most of his life.

Gabriel Thompson has produced one of the most thought-provoking books on organizing and affecting social change that I have read in some time. In telling Fred Ross’ life story, Thompson has dared to push the envelope on matters that many progressives would rather ignore.

_____________________________◊◊◊_____________________________

Comment by Mike Miller on 13 July 2016:

Thanks, Bill, for this thoughtful review. Every young person entering the field, and every veteran as well, should read your cautions regarding “the life of an organizer”. As you appropriately warn, the single-dimension organizer, consumed by the work, runs the risk of losing his or her soul. You and I have seen too many who have.

Here I want to comment on the portions of your review having to do with Ross and Alinsky. As some readers know, making comments on Alinsky is something I’ve done rather frequently in the last several years–so first I want to say why I think it’s important.

There are now across the country a number of organizing “networks” that owe their origins to some degree or other to the thinking and organizing of Saul Alinsky. These networks, and the local affiliates or chapters that are part of them, are often viewed with suspicion, criticism and even outright hostility by many on “the left”. That is a tragedy for both parties. Here’s why I think that’s the case.

These groups are engaging in a wide range of significant issue areas, including: immigration reform, police-community relations and police killings in African-American communities, payday lending, affordable housing, environmental justice, education reform, job opportunities and living wages, tax reform, services for the elderly and disabled, gun control, and more. At the national, state and local levels, varying from place to place, SEIU, AFSCME, NEA, ATU and perhaps other unions are, or have been, in alliances with one or another of these networks and/or their affiliates.

In some networks, the form of organization is a rather tightly-knit together city, county or regional federation of “institutions”–congregations, local schools and an occasional union local; in others, it is a more loose-knit regional, statewide or national coalition; in yet others it is a statewide or national organization made up of individual/family membership local chapters. Some of the groups have broad and deep support, turning thousands of people out for their “actions”; others are just another group in their local scene and have a long way to go before they will affect policy or power relations.

Noticeably absent, at least for the most part, are unions or union locals whose leadership is “left”, religious congregations whose pastors’ orientation is toward “liberation theology” (rather than other theologies that support social change), and individual members who consider themselves “progressive” or “left”. That’s not good. The Alinsky-tradition organizations lose because the talents, commitment and numbers of those who don’t join them are absent. And the left and progressives lose because they are out of touch with an important and growing organizing tradition from which they might learn something as well as make a contribution.

Some comments in your review of America’s Social Arsonist: Fred Ross and the Grassroots Organizing Tradition in the Twentieth Century suggest that you might agree with my observations above. You call Ross a “legendary community organizer…one of the foremost progressive organizers of the 20th century…” You say of yourself, “I have been highly critical of Alinsky and those who have followed in his wake for their de-ideologizing of organizing…”

To square the circle—praise for Ross but criticism of Alinsky—you say Ross “appears to have been a somewhat different sort of character,” and you see his work as “akin to a sort of ‘evolutionary leftism’, that through various forms of progressive organizing, we will naturally achieve the kinds of transformations we need as a society—no larger ideology necessary.”

Ross and Alinsky believed that a deep understanding of democracy—far more than periodic elections in which voters are consumers to whom candidates are sold—was the basis for creating a just society. That, and commitments to social and economic justice and equality, and the freedoms of the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution were at the core of their work. Within the “mass organizations” they created people of different faiths and ideologies could argue about what was required to realize these values.

You also emphasize the difference between Alinsky’s “organization of organizations…locally-based coalitions…frequently rooted in the religious community. This aimed to give some level of credibility for the organizing effort. But,” you say, “Ross disagreed: He believed in the need to create new community-based organizations that were unencumbered by older leaderships who he frequently believed to be too passive or otherwise obstructive.” Others have emphasized this difference as well.

The difference was tactical: it had to do with the fact that Los Angeles Archdiocese arch-conservative Cardinal James Francis McIntyre was, as Alinsky said, “an un-Christian pre-historic muttonhead”. The only credibility he would give to an organizing operation was his opposition to it. He had to be bypassed institutionally, but many a priest and nun provided Ross with the local legitimacy he required to talk with the overwhelmingly Catholic Mexican-American community. That’s quite a contrast with Alinsky’s Chicago experience where Bishop Bernard J. Shiel introduced Alinsky to local priests in the neighborhood adjoining Chicago’s stockyards, and urged them to join in the Back of the Yards Neighborhood Council, the organization that served as the continuing vehicle of cooperation between the Packinghouse Workers Organizing Committee (later United Packinghouse Workers of America), led by Herb March, an open member of the Communist Party, and the overwhelming Catholic neighborhood.

Indeed, Alinsky went international with this approach. Cardinal Montini of Milan (later Pope Paul VI) invited him there to discuss how the Catholic Church could respond to the Italian Communist Party’s power with the working class. Alinsky’s counsel?: Develop an organization where you can work together so that you can demonstrate your commitment to justice in an organization where you’re on a level playing field with the Communists. Alinsky met with Communist leadership in Milan to discuss the possibility as well. Not too different from what various Catholics and Communists in Italy were talking about around that time: a non-Cold War, small “d” democratic way forward. Alinsky concluded that the church was too enmeshed in the Christian Democratic Party for anything like Back of the Yards Neighborhood Council to happen in Italy.

Having directed (1967/68) one of Alinsky’s “organization of organizations,” I can tell you from my experience on the ground that these groups generated new leadership. Older leaders either joined in a mass-based, direct action, negotiations with the powers-that-be approach to change or were left behind. There were three people on my organizing staff. I “staffed” all our church members, a UAW black caucus at the Fisher Body Plant and CORE, among others. Another of our staff worked solely developing tenant associations in two major public housing projects. And the third organizer worked with senior citizen clubs and block clubs in the lower-income portion of Kansas City, MO’s large African-American community.

The economic and social justice traditions of the Catholic and Protestant churches, as well as of Judaism, use a different language than yours. Alinsky and Ross used the language of democracy, the right (and responsibility) of the people to be on going participants in the creation of their destinies, the antagonism to democracy of great concentrations of wealth, income and power to make it possible for people of all faiths, no faith, and Marxist understanding to work together in a common endeavor. Heirs to their tradition (and I’m not talking about the people in the AFL-CIO who call themselves “Alinskyites”—or whatever term they might use) now are building sometimes more- and sometimes-less effective contemporary versions of what Alinsky and Ross created from the late 1940s to the late 1960s. People on the left ought to be part of these organizations.

Mike Miller

Fellow Workers: Read this book!

By Peter Cole

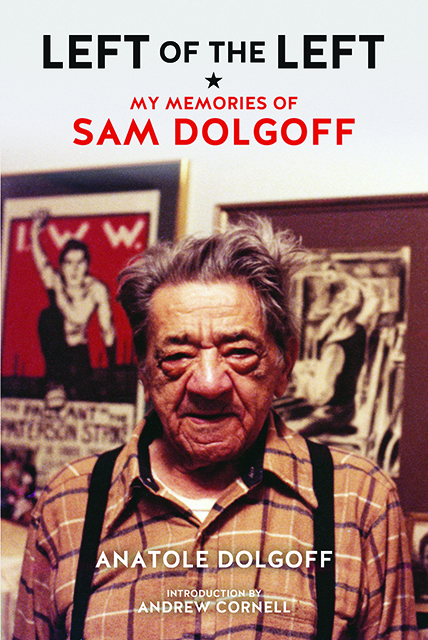

Anatole Dolgoff, Left of the Left: My Memories of Sam Dolgoff, with an introduction by Andrew Cornell. AK Press, 2016. 400 pages.

If you want to read the god-honest and god-awful truth about being a left-wing radical in 20th century America, drop whatever you’re doing, pick up this book, and read it. Pronto! If you’re not crying within five pages, you might want to check on whether you’ve got a heart and a pulse. Anatole Dolgoff’s love, admiration, and memories of his father saturate the pages, making it required reading for folks interested in the Wobblies, anarchists, workers, unionists, New Yorkers, Americans, non-Americans, un-Americans, and every other human being, for that matter. Make no mistake, the seventy-nine year Anatole Dolgoff might be a first-time book author but he’s one helluva a brilliant story-teller.

Dolgoff met or was friends with Carlo Tresca (one of his closest friends before being murdered), Dorothy Day, Bayard Rustin, Murray Bookchin, Ammon Hennacy, David van Ronk, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Michael Harrington, Paul Avrich, and Peter Kropotkin’s only daughter, Alexandra. He had friends who knew Lenin, Mao, and Gandhi.

On the 50th anniversary of the state of Illinois’ execution of the Haymarket anarchists, in 1937, Dolgoff shared a speaker’s platform with Lucy Parsons, the legendary anarchist, revolutionary, Wobbly co-founder, and widow of Haymarket martyr Albert Parsons.

Dolgoff met Eugene Debs. He knew the writer Eugene O’Neill and the artist Diego Rivera. He was great friends with Dr. Ben Reitman, Emma Goldman’s on-again, off-again lover known as the “clap doctor” for treating street prostitutes who had sexually transmitted diseases in an era when no “respectable” doctor would.

Anatole Dolgoff’s middle name is Durruti, after Beunaventura Durruti, one of Spain’s greatest anarchist fighters who died defending Madrid from the fascists during the Spanish Civil War (more on Spain, later). The Soviet Union, China and Mexico, the Dominican Republic and many parts of North America figure into Sam’s life and Anatole’s telling of it.

The book is worth reading simply for the opening chapter. Set sometime in the 1940s, Anatole recounts walking with his father and older brother, Abe, from their Lower East Side apartment across lower Manhattan to get to the Marine Transport Workers Industrial Union 510 (MTW) hall in a decrepit, now-razed loft where they spent many Sundays with old-time Wobbly sailors. I’m a historian of the IWW but in this vignette, as in many others in the book, Dolgoff captured the essence of the Wobblies better than I ever have (I’m ashamed to admit).

Full disclosure: it is because I researched and wrote on the Wobblies that I met Anatole Dolgoff. A few years after my Wobblies on the Waterfront, on Philadelphia’s interracial longhsore union, and an edited volume on Ben Fletcher, their “Black Wobbly” leader, I got an email from Anatole. He had known—as a young boy—Fletcher. Here was a man who could tell me stories about the most prominent African American in IWW history because his father and Fletcher were close friends. As a child, Anatole spent quality time with Fletcher and remembered him fondly and well. But let me also confess, and meaning no disrespect, that I had no idea that Anatole’s stories were this good or that he could write so damned well!

In addition to capturing the history but also—harder—the feel of many of the Wobblies and other anarchist/left individuals, organizations, and moments, this book is wonderful for those simply wanting to open a window into the past.

Take New York City, an incredible city that justifiably has received countless authors’ attentions. Dolgoff poignantly captures the feel of 20th century working class New York, a “lost New York.” Lower Manhattan, parts of Brooklyn, the occasional foray into the Bronx. New Yorkers and those who love New York will find much to love about this book as he walks “through lower Manhattan streets not to be gentrified for fifty years” along with the Puerto Rican, Italian, Jewish, and other residents.

Moreover, the language is, well, of a time and a place. Where else, these days, can one read words like “floor moppers” and “sonofabitch”?

As Dolgoff declared near his memoir’s start: “What I can do is tell stories: of my parents and their world, which spans seventy years of revolutionary activity…Hopefully it will add up to a history of sorts…Do not look for ‘objectivity.’ To hell with it. I have read many such ‘objective’ accounts of the anarchists and Wobblies, and few of them bear any resemblance to the flesh-and-blood human beings who broke bread with us or snored on our sagging couch. I’ve opted for the truth instead.”

Like so many others, Sam Dolgoff was the son of desperately poor Jewish immigrants from tsarist Russia. Like so many others, they ended up on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. As the oldest child, Sam went to work at the tender age of eight, delivering milk off a horse-drawn wagon before dawn. A few years later, his father apprenticed him to a house painter, a trade at which he worked for the next sixty years.

Dolgoff was working class through and through and proud of it, as were nearly all the Wobblies who toiled as Jack tars and timber beasts, gandy dancers and harvest stiffs. First drawn to the Socialist Party and the Young People’s Socialist League (YPSL), he abandoned their vision of evolutionary socialism and electoral compromises for the anarchists. A while later, he found his ideological home, the IWW, the great anarcho-syndicalist union founded in Chicago in 1905. Dolgoff believed that revolutionary industrial unionism was the only path to Socialism—at the point of production where workers, people, had real power. He committed himself for the next seventy years to that belief. Anti-capitalist and unrepentant, he never took a job that required him to fire or hire another fellow worker. Supporter of the underdog and the little guy. Hater of the 1% before such a phrase existed. Humanist. Wanting to build a society from within the ashes of the old. Willing to fight for it, strike for it, suffer for it, go hungry for it, help out someone who’s even hungrier.

To Dolgoff, capitalism, the State, and organized religion caused most of the world’s suffering which was why he became an anarchist. He hated hierarchy, oppression, and the institutions that both caused and perpetuated it so loved the Wobblies. He also loved to sing Wobbly tunes like “Halleliuah, I’m a bum,” “Solidarity Forever,” and countless other gems.

This historian of the IWW found it especially interesting that Dolgoff’s time in it began in the early-mid 1920s. That is, after its so-called hey-day, after the government had arrested and imprisoned most of its most important leaders and deported others, after many states had made belonging to the IWW illegal under unconstitutional “criminal syndicalist” laws, after many local and state police and vigilantes had further beaten and imprisoned Wobblies and shut down their halls, after the lynchings of Frank Little and Wesley Everest, after the Bisbee deportation and Everett massacre. And after the rise of the Soviet Union and Communist Party (CP) that did all in its power to undermine, co-opt, and destroy the IWW for presenting an alternative view of what socialism looked like.

We read about Wobblies in the interwar years, organizing the Unemployed Union in Chicago in the early days of the Great Depression. Anatole actually makes an argument that underneath, behind, to the side of many great Left actions, events, and organizations in the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s were Wobblies. While perhaps overstating his case, undeniablely many unions, most obviously in the newly-founded CIO, and other progressive organizations were influenced by the IWW.

A great deal of this book is about anarchism, an ideology that attracted Dolgoff. Over time, he became a much-in-demand speaker, brilliant author, and even theoretician of anarchism.

Though only finishing eighth grade, Dolgoff evolved into a great intellectual, schooled by some of the greatest anarchists of the early 20th century. Familiar to precious few, the legendary Russian anarchist Gregorii Maximoff made Dolgoff into the man and reader he became. Anatole describes Maximoff this way: “a man who had faced down the power of Lenin; had come within hours of a ring squad; had conducted a successful hunger strike in the Cheka dungeons; had organized steel mills and peasant collectives; had served as an editor of important journals and, while in Berlin, helped found an international anarchist organization comprising—it may surprise you—several million people.” Maximoff and his fellow Russian anarchists who lived in permanent exile made Dolgoff read Bakunin and Kropotkin but also Marx and Lenin as well as Shakespeare and Twain. He read constantly—even after a full day of work and despite having a wife and two sons.

One of the pivotal times in Dolgoff’s life, as well as for others on the left was the Spanish Civil War. Recall Anatole’s middle name, Durruti. Predictably, Sam was not just a kindred spirit with the National Confederation of Labor (CNT), the anarchist union and spiritual sibling of the IWW. The CNT stronghold of Barcelona proved the high point, early in the Civil War, of the cause. Dolgoff was a leading supporter, propagandist, and fundraiser for the CNT and Spanish Republicans. For those interested in this tragedy and its long shadow, this book offers much.

Some chapters in the book, vignettes really, are amazing stories of people few ever knew about. Dolgoff knew I.N. Steinberg, the “Peoples Commissar of Justice in the Soviet government from December 1917 to March 1918 and a central figure in the drafting of the Soviet Constitution, [who] came to tell us of his private, face-to-face meeting with Lenin in that sparsely furnished Kremlin room where he [literally] forged the communist state. Steinberg had been there to protest the vicious crackdown of the Cheka on all dissent and suspected dissenters. Vanishing people, torture, murder—all without trial or even a hearing.” Steinberg was one of many anti-CP leftists who pepper this book.

Dolgoff never gave up on his beliefs nor stopped organizing. For instance, during the height of the Cold War, Dolgoff helped found the Libertarian League that proclaimed: “The ‘free’ world is not free; the ‘communist’ world is not communist. We reject both: one is becoming totalitarian; the other is already so.”

Anatole is not uncritical of his father, particularly his father’s drinking problems as well as poor treatment of his devoted, loving wife and life partner, or his falling out with his older son. Anatole also discusses, briefly, his own life and travails though he would be the first to admit that his life mostly has been a good one, greatly enriched by his father.

Anatole wrote this book, after retiring, because friends “urged me to put my ghosts and shadows down on paper. And so I have. I leave behind a record of my parents’ life and through them a history of sorts, the history of a culture, and of a chapter of American radicalism that few people know about. It is an incomplete and inadequate record no doubt.”

I cried at the beginning of this book and again at its end. Since its so wonderful, I will not reveal more details—no spoilers here—but suffice that the last few years of Dolgoff’s incredible life were as honest and compelling as his first eighty-five. Truly, there is no other way for me to end this essay than Sam Dolgoff, Presente!

_____________________________◊◊◊_____________________________

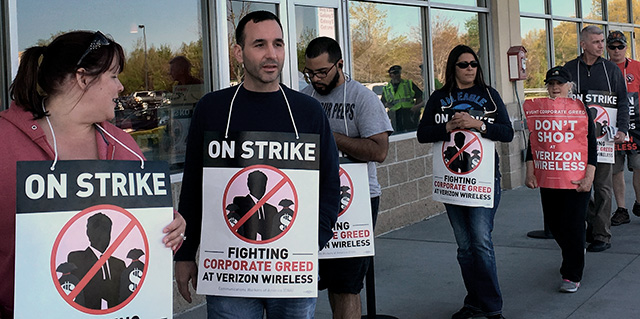

Verizon Strike Shows Effectiveness of Strike Tactic

By Peter Olney and Rand Wilson

On April 13, 39,000 union members struck to defeat company proposals that would have wiped out their job protections, security, pension and health care. The two Verizon unions, the Communications Workers of America (CWA) and the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW) had been working under an expired contract since August of 2015.

The company, although incredibly profitable ($39 billion in profit over the last three years) wanted deep cutbacks and concessions such as:

• Higher employee costs for health care;

• Reduced retirement benefits;

• Outsourcing of 5,000 jobs;

• Right to force workers to travel out of state for work;

• Company unilateral scheduling power.

Verizon workers are some of the most militant workers in the United States. Negotiations for the last contract in 2011 resulted in a two-week strike. This strike lasted 49 days.

“This was our fifth strike at Verizon [and its predecessor telecom companies] in 30 years,” said Matt Lyons, a Splice Service Technician with 29 years of service who is Chief Steward at IBEW Local 2222. “We’ve won every single strike because of our numbers and experience: we know what we are doing.”

The strike was fueled by anger at the company demands and the arrogance of a CEO, Lowell McAdams, whose annual compensation is $18 million — 208 times that of an average Verizon line worker at $86,000.

Over those 30 years, the Verizon workforce has been greatly reduced due to new technology and outsourcing. However, in some ways the remaining workforce is stronger and now more essential than ever to the company.

“We actively disrupted business at Verizon Wireless stores up and down the East Coast and in California,” said Lyons. “It impacted the wireless side of their business which is their most profitable. I work in wire line special services with large corporate accounts. They were having a lot of trouble finding managers or scabs who could do my work.”

Union members have strong preservation of work language and make sure that managers don’t do bargaining unit work. “That left us in a strong position. They don’t really know how to do our jobs'” added Lyons.

Lyons and other Verizon strikers picketed aggressively at hotels and motels housing replacement workers. Some evicted the scabs after union pressure.

Lyons believes that getting Thomas Perez, the United States Secretary of Labor involved helped expedite a settlement (HERE and HERE). On May 24, Perez and the two unions announced that a tentative agreement (subject to ratification by the membership) had been reached.

The unions succeeded in beating back all but the increased cost sharing in health care. The tentative deal includes unionization for workers at several Verizon stores in Brooklyn, NY and one in Everett, Massachusetts. The company also agreed to hire 1,300 new call center workers.

Solid strikes like this one are still an effective strategy for defeating corporate greed if waged with total solidarity and strategic smarts.

“We achieved a crucial first contract at the Verizon Wireless stores,” said Lyons. “Now it’s up to us to leverage our strength in the landline side of the business and build on that victory to organize the rest of the stores. It won’t be easy but the wireless side of the business is where all the future growth will be.”

“We couldn’t have won without the strong support of the rest of the labor movement and the communities where we live and work,” concluded Lyons. “Solidarity has become our lifestyle. Hopefully it spreads.”

_____________________________◊◊◊_____________________________

This piece originally in Italian appeared in Lavoro e Societa’ a newsletter of the CGIL – Confederazione Generale Italiana dei Lavoratori

Alabama Rising

By Joe Keffer

Some “Raise Up for $15” workers and family unwind after rally outside Birmingham City Hall. Photo: Joe Keffer

On June 6th, North Carolina NAACP President and Moral Monday architect, the Reverend Doctor William Barber, captivated a racially and ethnically mixed crowd, approaching 1000, at Birmingham Alabama’s New Pilgrim Baptist Church. Reverend Barber called for a revolution of values similar to those of the Civil Rights days. He admonished, “There comes a time when silence is betrayal.”

Alabama is one of the most anti-worker states in the country but the combination of a fight to increase minimum wages, a lawsuit, and the commitment to work in upcoming elections signals the kind of commitment called for by Reverend Barber and the possibility of a turnaround.

Alabama’s Well Deserved Anti-Union/Anti-Worker Reputation

Since 2010, the Republicans have held the governorship and a super majority in both state legislative branches. Alabamians have suffered greatly. The State has the fourth lowest median household income in the country: nearly 20% of residents live below the poverty line and the state’s unemployment rate – 6.1%.

The industry publication, 24/7 Wall Street, reports that Alabama is among the five worst run states. Controversy runs rampant among elected officals as the Republican governor, Speaker of the House, and State Supreme Court Chief Justice have been involved in scandals, convicted of crimes, or removed from office. The wrongdoing could go much deeper.

But the glitz of the scandals and corruption should not divert us from the legislative majority’s callous disregard for worker’s well being.

Alabama is one of only five states that refuses to enact a minimum wage law; defaulting to the federal minimum rate of $7.25. This low wage threshold plays a big role in the State’s poverty and misery.

Alabama is also staunchly a “right to work” state and recently incorporated the law into the State Constitution. The Economic Policy Institute and others say the law’s real goal is to undermine unions, and only provides a “right to work” for less. AFL-CIO research documents that the average worker in “Right to Work” states make $5,971 less in wages, have fewer or no health benefits, and the risk of workplace death is 45% higher. “Right to Work” states have much higher poverty rates.

And Alabama politicians don’t pull any punches when it comes to unions. In the middle of a recent union organizing drive, Republican Governor Bentley claimed that the state had to keep unions out and wages low in order to create a business friendly environment. Understandably, Golden Dragon workers (HERE and HERE) in Wilcox County ignored Bentley’s advice and voted to join the Steelworker’s union.

Birmingham Takes The Lead

Birmingham is 74% African-American and 47% of its children live in poverty. In August, 2015, seven of nine Birmingham City Council members and the Mayor supported a local ordinance that made Birmingham the first city in the Deep South to adopt a $10.10 minimum wage increase. Pegged to the consumer price index, it included raises for tip workers and strong enforcement language. It was to become effective in March 2016. It gave other big Alabama cities the resolve to move forward with similar ordinances.

When the legislature reconvened in 2016, it took Alabama Republican lawmakers a little over a week to squash Birmingham’s local efforts. The hasty legislative action allowed for virtually no public notice or input. The law passed prevents local jurisdictions from enacting any labor ordinances that impact workers. Within two hours, the governor signed the law into effect.

As a result, 42,000 Birmingham low-wage workers lost hourly increases of up to $2.85. In total, several hundred thousand workers statewide lost out.

Workers Fight Back

Rally in Mountain Brook, one of the wealthiest cities in the country and home to David Faulkner, attorney legislator and the point person for the state anti-minimum wage legislation. Photo Joe Keffer

The Greater Birmingham Ministries (GBM) led the coordination for Reverend Barber’s event. The NAACP, GBM and individual plaintiffs have sued. They allege that the state, in its haste, failed to adhere to mandatory procedural protections, equal rights and other violations.

Lawsuits can pay big dividends but litigation is traditionally slow and tends to substitute the judiciary for community involvement and on-the-ground organizing. To avoid this trap, workers have launched an aggressive campaign to gain not only a higher minimum wage but also fight for: voting rights, Medicaid expansion, immigrant and LGBT rights, prison and pay-day lending reform.

A public outcry followed the state’s intrusion into local control. With an effective media strategy, the story picked up coverage locally, nationally and even internationally.

Education leads to activism. From the beginning, “Raise Up For $15 Alabama” put a human face on their campaign as it pressed for $15 and a union. The National Employment Law Project provided invaluable legal and research assistance. Rallies have been held and more are planned.

As we head into a general election year, Jim Price, Co-Chair of “Move to Amend Tuscaloosa”, a group dedicated to election and campaign finance reform, says that communities need to get involved in electoral politics. “More so than ever before, the well-being of our communities, state and country depend on it.” says Price.

For questions, comments or to get involved, call: Alabama Coalition for Economic Justice at 334-587-0507

____________________________◊◊◊____________________________

Workers

By Robert Gumpert

Walk On, Walk On: Obituary: BARBARA WEARNE by Phillip Wearne (Son)

By Phillip Wearne

“Keeping walking! That’s it! Keep walking, BarBara!” my mother remembered her father calling as she edged her way, arms outstretched, down the two walls of the hall dragging the unyielding deadweight of the leather and steel calipers on her legs. Walk she did. Indeed, she ran, marched, swum, cycled, surfed, sailed and scuba dived all over the world for a very full 89 years.

BarBara Wearne, a 36-year resident of Instow, died peacefully, quickly but very unexpectedly in her own armchair in her own house on December 3rd 2015. Her last words as she sat down to “take a bit of a rest” and read the paper were: “I feel like I’ve climbed a very steep hill.” She had. It was a perfect epitaph – and true to form — her very own.

BarBara overcame the worst effects of polio as a child in the 1930s. Without her determination and the skill of some unorthodox surgery she might have been in a wheelchair or in calipers for life. The experience totally moulded her character and philosophy. She remained committed to the underdog, the disabled, the poor and the marginalized. And she worked tirelessly for what she saw as the obvious antidotes to their condition: greater equality, more justice, real human rights and meaningful sustainability.

She was active on and angry with the state of the world to the very end. She braved the driving rain to join the climate change protest march in Bideford four days before her death and died with an appeal for donations of clothing and equipment for refugees reaching the Greek islands on her front gate.

Born in 1926, BarBara left school in 1942 to work for the Library Association, evacuated from London to her home town Launceston in Cornwall. When the first blitz was over, they returned, with BarBara now an employee and, at 18 she enlisted, becoming an air raid warden. She vividly recalled typing leaflets for the Labour Party’s 1945 election landslide in south London and went onto qualify as a primary school teacher with a speciality in, somewhat incredibly, Physical Education.

She became a primary school teacher in Mevagissey, Cornwall, where in 1952, she met my father, the local priest and a former Far East Prisoner of War (FEPOW). By the early 1960s, they had four children, Phillip, Jane, Sue and Liz and had settled in Hills View, Braunton. Her life was totally transformed however when Edwin “Ted” Wearne was diagnosed with a brain tumor, dying a protracted death, punctuated by long hospital stays and painful treatment, in June 1966.

Winning the struggle to keep her family together over the next 15 years, whilst teaching full time, paying a mortgage, and caring for four children, the youngest of whom was barely two at the time of my father’s death, was probably an even greater feat than overcoming polio. This was an age when married women working, let alone mothers and widows “abandoning” their children to do so, was considered dangerously subversive.

She never forgot the solidarity, support and sense of those who rallied round to support her right to work – and make that possible. She always said that we would not have survived as a family and perhaps as individuals without Braunton’s Iris Sandercock, “Cock-Cock” to us children. Cook, childminder, cleaner, second mother, agony aunt, there was nothing Iris Sandercock was not to our family for so many years.

With all her children in higher education or careers, BarBara took early retirement in 1981 and began a third life, one of travel, fundraising, campaigning and political and health service activism. South and Central America, East and Central Africa, everywhere in Asia from Japan to Turkey were the locations of her 25 years of winter backpacking adventures. But she always returned for spring and summer, relishing the surfing, sailing and swimming she loved in North Devon.

The highlights of her travels? Oh, so many.

Lecturing John Paul II in Belize on his treatment of the radical Catholic priests in the Sandinista government in 1983; being detained with Aung San Suu Kyi under house arrest in Yangon (Rangoon), Myanmar (Burma) in 1995; raising £4787 for leprosy treatment by cycling more than 500 miles around Malawi at the age of 70; visiting the AIDS belt of Central Africa to show villagers a film I had made with them in 2000. Finally, in 2005 and 2006, we enjoyed two trips to Japan and South East Asia in an effort to piece together my father’s wartime story, so little of which he had revealed to her while alive.

In recent years, many in Instow will remember her best for village hall fund-raisers for the victims of the Haiti (2010) and Nepal (2015) earthquakes. Her growing and eventually profound deafness spawned another vigorous campaign – for digital hearing aids on the NHS and much greater awareness of the social exclusion of those with hearing impairment.

BarBara’s four grandchildren, Thomas, Elliot, Lottie and Asa were always being encouraged to follow her example and in their music, sports, travel, theatre production and above all voluntary work. At the time of her death, the eldest Thomas, and his wife Mohua, were following in her footsteps in Asia. BarBara relished reliving her adventures through their travel blog in her last weeks.

“Aren’t we lucky? We’re going into our 89th year,” an old schoolfriend wrote to her in a birthday card in 2014. “Aren’t we lucky! Aren’t I lucky!” she would repeat to me throughout her last year. Yes, you were, mum. But you not only knew it, you understood it, never forgot it and determined to do as much as you could for those who were not so lucky.

You knew and understood that the exhausted refugee swimming ashore in Greece, the polio victim unable to walk in Sierra Leone, the young Indian mother murdered for forming a weaving co-operative in Guatemala, could have been you — or any one of us. I know, those who knew you well will know, that you will not rest in peace unless many more of us match your commitment to those you always understood could so easily have been you in a wheelchair longing to walk, run, cycle and swim the world.

BarBara Wearne donated her body to medical science in the hope that a new generation of surgeons might achieve for others what those of the 1930s had done for her. So no funeral. A memorial service will take place at St. Peter’s Church Fremington, North Devon at 11.30 am on Saturday June 25th. In death, as in life, all welcome.

_____________________________◊◊◊_____________________________

Edior’s Note: Phillip Wearne and I meet when the London Sunday Times Magazine sent us as a writer-photographer team to Haiti to do a couple of stories: Mother Teressa’s “death house” and the election of Jean-Bertrand Aristide. We have been friends ever since. Phillip is a Journalist: tenuous, curious, loves fieldwork, the chase and has the distrust/disrespect of authority needed to do the job well.

On one of my many trips to London I had the fortunate pleasure to meet his mom. She would have been a great Journalist. She was an inspiration to all who came in contact.

These are, to say the least, interesting and difficult times but reading about BarBara Wearne gives hope and joy. This obit ran originally in the local Parish News.

Reato Regionale Toscano- Getting Busted Tuscany Style

By Christina Perez

On our month-long trip to Florence, Italy my husband and I bought the CARTA ATAF&Linea Pass-the local regional transit ticket with ten rides on each CARTA to get us on as many trains or buses within the limits of Firenze. Being a walkable city, we barely used the CARTA the first three weeks. Like the MUNI Pass in San Francisco, CA., the CARTA is a money saver as 10 rides costs 10 Euros at 90 minutes per ride versus 1.2 Euros for a single ride. Also, like the Muni Pass the CARTA is very easy to use: one places the CARTA over a CARTA reader on a bus or train which beeps and registers VALIDO and, as they say in Italia, Ecco, ready to go!

Allora (so) one afternoon I took a solo trip on the train from the Alamanni-Stazione to Nenni Torregalli, which is 9 stops, or approximately 20 minutes one way to Scandicci where my Italian-speaking husband and I had been the night before to look at a CoOp shopping center. To safely return by daylight I hopped back on a return train repeating the swiping ritual of the CARTA and hearing the familiar “beep” and settled-in for the picturesque ride through the outskirts of Firenze and the town of Scandicci. I was momentarily distracted by a man and woman who entered the train with me and sat chatting in a language that I could not make out. Not being conversant in Italian I was hoping they were speaking Spanish and were travelers like me so we might have a casual exchange. Needless to say, by three weeks, I was hungry for spontaneous and casual conversation of my own making. But I didn’t get to figure out what they were speaking.

Out of the corner of my eye I noticed a Train Officer walking the length of the train asking passengers for their tickets to check for validity. The only difference I noticed between the Italian and San Francisco train experience was that there was only one Italian officer where in San Francisco there are always two, if not three on a train working together, and the Italian officer didn’t wear a revolver or stungun.

Finally the Train Officer got to the end of the train where I and the couple were sitting and their tickets were fine. But when he checked my CARTA Pass in his hand-held ticket reader he said “senza credito.” After demonstrating to him that the reader read my CARTA “valido” he said “no, “senza credito.” I told him that I didn’t speak Italiano and tried to explain in Spanish and pantomime how I had boarded the train, but he only asked me for “documenti” and “vivenda”- passport and where did I live in Firenze. After I provided him with both he proceeded to write me an “infrazione” a fine for $55 Euros, that I could pay on the spot, or “il ufficio”- I opted to pay in some elusive ATAF ufficio as he handed me my pink copy before he departed at the next stop.

I shrugged my shoulders in disbelief as the couple in front of me looked on compassionately- apparently they didn’t speak enough Italian to vouch for me. After hearing my story and feeling the Euro shock my husband had a good laugh and said “just another adventure; next we go to the ATAF ufficio for the real fun!”

Within a couple of days we are at the main office of the ATAF in Firenze. We decided in advance that my husband would not participate in the discussion because he knows enough Italian to get us into more trouble, and I would only speak to clarify or if specifically asked a question. Since I did what I was supposed to, that is pay my fair share when boarding the train, our goal was to have the $55 Euro fine cancelled. Our local friends of over 45 years Marinella and Franco explained my situation to an ATAF bureaucrat in the ATAF lobby. The woman administrator from the ATAF was pleasant enough but she wasn’t willing to consider the possibility that I did nothing to warrant the CARTA infraction.

Back and forth Marinella and Franco went, each becoming more agitated and outraged, but restrained as they confronted the ATAF administrator raising their voices, raising their arms, moving each other out of the other’s way to get ‘in the face’ of the administrator and emphasize their specific point- pure Italian theatre! In the meantime, the ATAF administrator coolly dismissed all facts, including that there were still two rides left on my CARTA, that the Officers Ticket Reader could have malfunctioned, or that I the passenger could have been right all along. To add insult to injury, the ATAF administrator told us that even though the CARTA reader read VALIDO and Beeped when I swiped it, I should have known to double-check to make sure it was correct!! Incredulously Marinella and Franco said, “even as Italians we would NEVER double-check if the Reader said it was Valido- how is anybody supposed to know that, there are no signs, that is ridiculous!”

In the end, under unofficial protest to the ATAF administrator, I paid the “multa” rather than risk being told at Customs before returning home there was a police record for failure to pay an ATAF fine.

Minutes later over remarkable cannoli’s and cafe lattes, I said to Marinella, Franco and Peter “its like contraception, I did what I was supposed to do but got caught anyway!” Marinella translated this to Franco who jokingly pantomimed blowing up a reliable condom, then as if betrayed by the condom, with arms extended, eyebrows arched and lips pursing, he is asking “what happened?!”… Viva Italia!!

Lotta di Classe o Lotta di Generazione?!*

By Peter Olney

Firenze 7 Maggio 2016

Italy has been a point of reference for me because of the historic strength of its labor federations. When I lived here in 1971-72 (here and here) the unions were at the apex of their power and central to all discussions of radical societal change. That power has declined but the percentage of workers in unions remains at 37.2% of the entire workforce. This is more than three times the “density” of US unions at a paltry 11%. The Italian number is more impressive if one takes into account that membership in the various labor federations is a matter of personal choice not a “term and condition of employment” as it is for most US union members. The percent of Italian workers covered by collective negotiations is 80%! This means that the great majority of Italian workers are covered by contracts negotiated by unions that they don’t even have to belong to.

The Italian union federations and political parties (more on the “parties” in a future installment) have been under great pressure to loosen the terms of employment to make it easier for employers to hire and fire. They have also acceded to “two tier” employment contracts as have their American manufacturing counterparts like the UAW. For the generation of those born prior to the January 1, 1970 pensions will be 90% of their last earnings as long as they have 18 years of work credit. For those under 40 today the pension will only be 36% of salary.

This retirement income disparity is enormous. The annual earnings gap across generations is also enormous: a 24 year old worker makes on average 19,217 Euros per year vs. a 55 year old worker’s 31,873 Euros. No wonder that the discourse in the “dailies”, “I Giornali” is all about the generation gap and not the class struggle. The former Prime Minister of Italy Mario Monti was quoted as asserting that the youth of Italy born in the 70’s and 80’s were a lost generation and that Italy could only hope to limit the damage to them and provide better for subsequent generations. Our friend Enrico, born in the 80’s, hipped me to an article on a blog called “Medium Italy” written by Maurizo Pittau and entitled, “The Lost Generation of the 70’s and 80’s“. Pittau says young Italians of his generation have only two choices: Accommodate a corrupt system and work precariously or leave the country. He has chosen the latter as have many young Italians. Youth unemployment is 35% nationally and over 50% in the historically underdeveloped South.

Pittau cites a figure of 8 million workers in the precariat: the underemployed, temps, self- employed. Of that number he calculates that 4 million are the in the black market economy. The discussion of the precariat and the verification of the numbers is as my friend Nicola put it, a “Tower of Babel”, lots of numbers and lots of definitions and lots of confusion. This is certainly true in the United States where whole industries are characterized as “precarious” with no reference to solid research and numbers. The best figures I could find for Italy and employment on a web site called ItaliaOra.org indicates the following:

Italian population: 62, 375, 215

Total Italian workforce: 24,820,424

Precariat: 3,488,940

Unemployed: 3,267,950

The precariat then represents 14% of the total workforce. This is a growing number and a preoccupation of the labor federations who see their power slipping as enrollment declines and the younger generation is increasingly skeptical of trade unionism and the two tier deals that impact their cohort.

“Common sense” has it that unions are antiquated self-serving protection rackets for the older generations with fixed employment contracts and generous pensions. However one respondent to Pittau’s blog, Daniele Dellafiore, said that he thought there was a “third way” to deal with the challenges to the “lost generations”. Rather than accommodate the injustices or flee the country, he has chosen to stay and changes things. Stay tuned as my discussion with CGIL (Confederazione Generale Italiana dei Lavoratori) leaders and activists will hopefully paint a picture of what staying and changing things looks like here in Italy.

La lotta continua….

*Class Struggle or Generational Struggle?!

_______________________________________________________________

In response to my post entitled Class Struggle or Generational Struggle, Nicola wrote:

Firenze 9 Maggio 2016

Dear Peter,

Generational conflict or class struggle? There are four fundamental points:

1. On the crisis of the unions caused by their membership losses in key sectors of the economy and the excessive power of the associations of the pensioners, an article in La Repubblica of August 19, 2015 by Matteo Pucciarelli details how profound the change in the composition of the unions is. (Olney summary: Pucciarelli writes about an extensive report prepared by the CGIL, Itay’s largest and historically Communist led union federation. The report includes many details but the fundamental and startling fact is that in the period from the end of 2014 until August of 2015 the federation lost 723,969 members. This is a 13% loss in a year from a total of 5.6 million members. This membership is voluntary unlike most membership in the United States. The largest losses in membership come in growth sectors of the economy like retail. The other stunning fact is that over half the membership of the CGIL are pensioners, therefore the political weight of the retired plays an outsize role in determining the future of the union with respect to the newly employed. For readers of Italians here is a link to the article in La Repubblica: )

2. The “dualism” in labor rights between workers who work in enterprises with more or less than 15 employees means a diversity in pay and rights.

3. Union policy that punishes the young. The newly hired cannot enjoy the same rights with respect to salary, holidays, job protections and least of all to pensions even though they do the identical job of more senior workers. I emphasize that I am not talking about the plethora of numbers in contract precarious work invented in the last twenty years, nor those covered under IVA (Imposta sul Valore Aggiunto – Tax on Value Added) the fiscal management of those “professionisti” who work not for a salary but for a fee. There is no fixed deduction on a salary (which they don’t have) but they pay IVA on the total compensation received in the fiscal year (a total often very high but varying from year to year). Given they are compensated with a fee their employment can end at any time.In fact these workers work for an enterprise but are paid less than employees doing the same work.

4. The pensions are a symbol of how slow the unions have been to take into account the changes in the labor market (and the general political situation); until the reform of 1995 it was possible to retire with 35 years of service regardless of your age. In other words someone who went to work at 14 years old after finishing minimum mandatory schooling could retire at 50 years old. After the reform two scenarios exist to activate the pension:

a. One needs 35 years or more of service and an age of at least 57 or;

b. 40 years of service independent of age.

These conditions were not sustainable in the long run because of increasing life expectancy. Salary and regulatory concessions were made primarily by governments of the left but also by the Alema government which tried to make reforms that were blocked.

Nicola

Italia: McDonald’s and Starbucks??

By Peter Olney

We had not been to Italy in almost 30 years and to our delight we found the neighborhood quality of life to be strong and vibrant: people walking everywhere with whole families, children crying in the street unashamed and unrestrained by their always-doting parents. Our neighbors freely introduce themselves to us and tell us their life histories in the hood. The world moves on bikes and Vespas. Whole families on rusty old bikes. Stores remain specialized: Panificio (baked goods), Ortolano (Greens etc.) Macelleria (Meats) etc. Life in our neighborhood of San Frediano remains sane and engaging.

But change is there too. My wife and I arrived in Florence on the train on Sunday evening and emerged from the station in the Piazza across from the church of Santa Maria Novella. While the lettering was discreet and there were no billboards, a whole block was taken up by a Burger King and a McDonald’s. 29 years ago on our last visit Burger King and a McDonald’s were not in Florence. In fact this is the 30th anniversary of the arrival of the first McDonald’s in Rome, Italy. That opening in Piazza di Spagna was met with a citywide mobilization. A protest in May of 1986 featured Italian politicians and intellectuals carrying signs with giant blowups of Clint Eastwood with the inscription, “You should be Our Mayor”. This was a reference to the fact that Eastwood as Mayor of sleepy and upscale Carmel in Monterey County, California, had moved to outlaw fast food joints as a rude incursion on the quality of life in the quaint resort town. Today there are 530 McDonalds’s restaurants in Italy and 270 McCafes serving 700,000 patrons per day. That is a significant number, but France has over 1300 outlets.

The new and perhaps deeper cultural challenge to the Italian way is the prospect that this year a Starbucks will open in Italy. Rome and Milan are slated to have the first outlets of the Seattle based coffee giant this year. What may seem amazing is that while Starbucks is ubiquitous in much of the rest of the world and is certainly everywhere in France, 39 in Paris alone, to date there has been no Italian market penetration.

Howard Schultz’s original inspiration for his cafes was the Italian cafe, which is more than a dispensary of coffee and pastries, but a neighborhood center and community-meeting place for small talk, big ideas and catching up. Schultz’s first outlets were called “Il Giornale” (the Daily) a reference to the Italian word for daily newspapers. In many corners of the United States and the world, Starbucks have become the centers of neighborhood life that their Italian counterparts are.

The cafe society is alive and well in Italy. Furthermore the bars also are licensed by the state to sell tobacco and vapor products, bus tickets and postage stamps. Will Italian youth flock to Starbucks and plug in their laptops and iPads for work and play? If they don’t and Italians reject Starbucks, is the model and brand severely damaged with consequences worldwide?

We have a whole month here to figure out the complexities of Italian politics and cultural interactions in dispatches to come. For now though life is good in Italia. Ciao a tutti!

______________________________◊◊◊______________________________