Migrant Labor-1/4: Migrants Are Who We Are

By John Shannon

In my Jack Liffey mystery, No. 11 titled Palos Verdes Blue, I write about Latino day laborers living rough (as the British say) between the fancy houses in pseudo-rural, wealthy and horsey Palos Verdes in south L.A., living in tents and cardboard camps in the deep canyons. In fact, I have no documentation for this being true in Palos Verdes, but it would not surprise me.

I know that hundreds of Mexicano farmworkers lived rough along the banks of the Santa Clara River in Ventura County as far back as the late 1920s. How do I know this?

Hundreds of their bodies were washed downstream after the catastrophic St. Francis Dam collapse and flood of 1928. Our celebrated city-engineer William Mulholland built this dam at a site that is now several miles east of Six Flags Magic Mountain to hold the Owens Valley water that the city basically stole. The dam was built over a fault line, one wing supported on a red conglomerate so crumbly they couldn’t get core samples to the test machine no matter how carefully they carried them and so water-soluble that a lump of it would disintegrate totally in a drinking glass in 30 minutes. The other wing rested on mica schist fantastically criss-crossed by slippage planes. The dam was up and full for one year—probably a world record in dam-brevity – before it collapsed in 1928.

The frothing 120-foot wave from 12 billion gallons of water released all at once churned at 20 MPH down San Francisquito Canyon toward the sea, obliterating several small towns, killing about 600 “named” people (local Anglos), plus roughly 430 unnamed (except to God) Mexicano farm workers camping near the river. Their bodies were still turning up or washing ashore as late as the 1950s. (I had a big concrete chunk of this dam for years as a souvenir and finally threw it away in disgust.)

And another instance. In the early 2000s, a good friend of mine who was fluent in Spanish worked for the San Juan Capistrano School District down the coast and was sent up into the local hills to talk Mexicano farm families living in makeshift tents and shanties up there to bring their kids down to the school system. Many finally did.

One more: I’ve just seen photographs of Latino workers living in plastic tents in the hills above the famous Carlsbad flower fields that draw thousands of tourists every year to north San Diego County.

Whether or not there are gardeners, houseboys, stonemasons and other laborers living in cardboard jungles in the canyons between the big Palos Verdes homes where they work, they’re definitely living in destitution somewhere nearby, ten to a room, trying to save a few dollars to send home.

We all see jornaleros (day-laborers) all the time at the moscas (labor markets) in front of Home Depots and lumberyards. Or do we see them? Are they invisible if we don’t need their labor right now?

First, why are they here at all? Here’s a big part of it: the best farmland in Northern Mexico is now owned by American agribusiness companies, who of course are underpaying and mechanizing. And American NAFTA corn (subsidized) is much cheaper than theirs.

Not unlike what happened to California’s central valley. Over the last half century and more, perhaps twenty giant agribusiness companies have taken literally trillions of dollars out of this intensively farmed fertile valley, the most productive farming valley on earth, they say. And here’s a surprise for you: it’s almost impossible to find out who most of the owners are, but you could start here and here.

Here’s what I do know: Individual owners, there’s J.G. Boswell and Red Emmerson, probably the two biggest of all. There’s Mobil Oil, there’s the successor to the Southern Pacific – the Tejon Ranch, then the King Ranch, Gallo and other grape empires, and there are a dozen giant combines that masquerade as “co-ops” of family farms but are really dominated by the biggest members: Dole, Provide, Sunkist, Blue Diamond, Foster Farms, Driscoll, etc. If somebody can get me a better list, please do. Virtually all these entities have their home offices in places like West L.A., Beverly Hills, Santa Barbara, San Francisco, and Sacramento. God forbid that the execs have to live near the abject destitution that they’ve caused.

What’s left behind after these massive fortunes are extracted from the dominated and cheap labor in the central valley? Impoverished small all-Latino towns with boarded-up downtowns, swap meets, and failing schools. Many don’t even have a supermarket, none have a tax base to speak of.

Instead of roaring through on Highway 99 and I-5, stop sometime in Maricopa or Buttonwillow, McFarland, Delano, Coalinga, and on and on. Try Chowchilla or Earlimart. Look around; richest farm valley on earth? Why do I see only poverty? You’ll see what rapacious and unscrupulous economic power can do when there’s no countervailing force. (The crushing and collapse of the farmworker unions, from the 1930s through the 1970s, is a story for another day.)

But I’m really talking now about the more recent arrivals, Latinos coming for city work, would-be town workers living at best in repurposed old Hawthorne motels, “hot beds” that swap three times a day in crowded back rooms and converted garages.

I want to talk about their plight later – how they cross the border and what it feels like to be an ignored jornalero – but for now here’s something important that we never consider. This migration north is an economic disaster for Mexico and Central America themselves.

· Who bore the cost of feeding, raising and educating the estimated 11 million Spanish-speakers who are in America without documents? People don’t sprout and grow by themselves, for free. The best estimate I’ve seen is that their upbringing to age 18 cost their national economies, in dollars adjusted over time, about $23,000 per person. Mexico and Central America paid this (you can do the math times 11 million persons) and now all this investment in future labor is lost to their home countries. Quite a gift to America. Okay, I’ll do the math for you: $253 billion dollars. And many don’t even stay to collect the Social Security and Medicare they paid into.

· In addition, because of the difficulty of the trek to el Norte, these are some of the most enterprising of their generations. It’s impossible to estimate what the loss of them means to their home countries.

· Whole villages have been stripped of their young and able-bodied men and become ghost villages of old people where farming continues to deteriorate.

· If the migrants do come home, they have few new skills and little to return to except migrating again to the largest nearby cities where there are jobs. This is why Mexico City has become arguably the most populous city in the world. Metro areas are notoriously hard to compare, but it’s between 17 and 22 million.

· And, ironically, much of the money they remitted home was spent on appliances and other commodities made in the U.S. or used in the U.S. Truckloads of old refrigerators head south every day from L.A., even old garage doors that are used to build shanties.

· I’m not competent to comment on what our banks, the IMF and other forms of international debt manage to extract from these countries for our benefit (or, really, the benefit of our banker-parasite 1% class.)

So what do I mean by the title: “Migrants Are Who We Are”?

Do you work in the town or city or suburb where you were born? I’ll bet you don’t. You had to go somewhere else to find work. It’s only an accident of history if you were able to go to a place that already speaks your language and has your culture. Migration and displacement are the human condition.

Next week, Part 2/4 of Migrant Labor

When I reflect on Labor Day

By Robert J.S. Ross, PhD

When I reflect on Labor Day I think about time – time for work and leisure, and the time that spans the generations. How precious it is, and how time is, after all, all we really have. We celebrate Labor Day in September because we don’t celebrate it when most nations celebrate workers, that is May 1. And May 1 is all about the eight-hour day. Let me unpack that — briefly.

Grover Cleveland signed the federal legislation in August 1894 a few days after he had sent troops to brutally suppress the strike of railroad workers and Pullman sleeping car makers. Though 30 states had Labor Day holiday legislation, at the federal level Cleveland was trying to placate a constituency he had deeply antagonized. The bill chose September in part to avoid May 1 because May Day had become a day in which socialists and anarchists demonstrated their power and commemorated the deaths of the leaders of the Haymarket Strike and riot of 1886. Those 1886 events marked the start of serious agitation for the eight-hour day.

By 1938 that was achieved in federal law, and many unions and employers in fact use standard weeks of 37 or even fewer hours. Pause for a moment and reflect on the “Eight Hour” song from the mid-19th Century:

“We want to feel the sunshine,

we want to smell the flowers

We’re sure that God has willed it,

And we mean to have eight hours”(1)

When we respect work and the people who do it, we respect ourselves and our brothers and sisters.

Another less anonymous poet, James Oppenheim wrote it thus in 1911:

“Small art and love and beauty their drudging spirits knew.

Yes, it is bread we fight for — but we fight for roses, too!

…No more the drudge and idler — ten that toil where one reposes,

But a sharing of life’s glories: Bread and roses! Bread and roses!”(2)

As we reflect on the dignity of labor and importance of decent conditions of work many of our own stories reflect the accomplishments of the generations before us. L’Dor V’Dor (or in English, “From Generation to Generation.”)

When I was a boy I would walk to the subway station near the Yankee Stadium to wait for my father to come home around seven pm and we would chat companionably for the three blocks to our apartment. Why seven: because the hours from 4-6:30 were overtime, time and a half: a “good” job for a garment cutter was one in which there was consistent overtime – that’s what made our first car – a Dodge – possible.

I should add that however secular my parents were, on Friday evening my Dad brought home flowers –and to this day so do my wife and I. Setting aside the Sabbath as a day where no work is done is the world’s first labor legislation.

So limiting worktime and rewarding it – is a part of the story of labor and Labor Day from Generation to Generation.

There was a time when there was a Jewish working class. Irving Howe notes that in New York forty percent of Jewish families had someone in the garment industry alone. But then, with Joni Mitchell and Judy Collins, they looked at love from both sides. My paternal grandfather was an organizer and leader in the early years of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union. Comrade Borochowitz once said to my Dad, “the hardest thing to teach Jewish workers was that Jewish bosses were bosses.”

The Jewish working class was central to the building up of the institutions upon which 20th Century decency has rested. The garment workers invented the HMO; the men’s clothing workers were among the founders of the very first industrial union, members of the CIO and leaders in what we now call “social unionism”.

My mother was a New York schoolteacher. When we were young, she was a single mother. We were the working poor. Her marriage to my Dad relieved our penury, but when they grew older, the erosion of his union and industry meant that in his later work years he was in nonunion shops. The wages were ok – but there were no pension contributions.

But aha, in the intervening years New York City schoolteachers had won union recognition and negotiated good pensions. So in their later years my parents were all right. Remember Joe Biden’s great line about the plight of working families: Can you say, he asked, “honey, it’s going to be okay” Well, for so many of us the pressing question has been, Mom and Dad, “Will you be all right?” It was a blessing that mine were. That’s why I will never forgive those who tried to blame New York’s fiscal woes on my mother and her pension! L’Dor V’Dor.

As I reach the end of my academic career, I remember vividly its beginning. At the University of Chicago, we graduate students in Sociology felt the basis on which fellowships and assistantships were awarded was mysterious and we suspected a hint of favoritism. We were, simply, abject, powerless subjects. When we asked that the process become more transparent, we – I – became extremely unpopular with the senior faculty.

I have to laugh; graduate students at private universities have just won the right to be represented by unions.

Should they choose to protect themselves from whim and caprice there is now a means to do so. There are many lessons here, among them, amid looming threats: sometimes Good Things Do Happen! From generation to generation.

In the 1950s American workers achieved what centuries of alchemists and mystics could not: they turned the lead of working class status into the gold of middle class consumption. Or anyhow, that is what the mass media thinks. By “middle class” they mean household incomes that hover in a band around the 50% point, half above, half below. No matter that the half-way point is now way into insecurity, debt, and constant stress. In the Boston metro-area that is about $73,000. An MIT living wage calculator for a family of four is $78,000. How did that working class raise its standard of living, and how did they lose it?

In that era about one-third of the private sector labor force were union members or covered by union contracts; today that is around 7%, but there are higher rates among public sector workers, especially teachers. L’Dor V’Dor.

When Frances Perkins, a veteran of the progressive movement, Hull House and the longest serving Cabinet Secretary and Labor Secretary in history entered Roosevelt’s cabinet, labor issues were at the top of the agenda of her middle class allies. But only recently, through the “Fight for $15 and a union,” have folks re-imagined what is needed to insure decency. But our thinking still has blind spots.

Consider one of the criticisms of Bully Donald Trump’s declared child care “policy” (though I hesitate to grace it with such an elaborately worked word). He said childcare expenses should be deductible. Well, one voiced criticism was that poor people would not benefit because they don’t pay taxes anyhow. True enough and a criticism to note. But in the meantime, millions of families in the middle-income belt certainly do pay taxes and any way of gaining relief will be welcome. Working families need justice and social solidarity just as do poor people. From Generation to Generation.

When 146 women and men and girls and boys were killed in the Triangle Shirtwaist fire this was a searing event for Jews, for workers and for New Yorkers. And they and we have been ever mindful of our obligation of memory and solidarity. I am proud of the work done by the Jewish Labor Committee and the Massachusetts Interfaith Committee for Worker Justice and JALSA – the Jewish Alliance for Law and Social Action who have reached out to support the victims of the killing fires and collapses in Bangladesh and elsewhere.

Today our community is global — as is our understanding of our interests and values. Here is the way I think of it: Our grandparents and parents rose out of the sweatshops; we owe them our love and gratitude for their sacrifice and accomplishment. Around the world the workers of the rag trade still toil in those conditions. We owe them what we owe them.

Owning our time is to live free. After work, after rest, the Eight Hour song put it so succinctly; “Eight hours for what we will.” L’Dor V’Dor.

_______________________________________________________________

Footnotes:

1) Lyrics to Eight Hours

2) Lyrics to James Oppenheim’s “Bread and Roses”

Traveling Grey Dog Style

By Nelson Perez-Olney

In mid July I packed a small backpack with 4 days worth of clothes and hopped aboard a plane to Dallas. I was beginning a two-week tour of the Deep South, my first ever trip to that part of the country. The plan, if it can be labeled such, was to arrive in Dallas and from there zigzag from city to city, spending a few days here and there until I reached Atlanta where I’d catch a flight home to San Francisco. I wanted to see the land of slavery, the civil war, Jim Crow, and civil rights. I wanted to see the states that figured into the worst stereotypes of American backwardness. I wanted either to challenge or affirm my notions of our southern neighbors.

Riding the Greyhound from city to city provided two advantages. The first was extreme practicality. I don’t think any other mode of transportation could have provided the type of flexibility and frequency of service that my plan required. The Greyhound, unlike airlines, trains, or even other bus lines, stops almost everywhere, and it does so at a very low price.

The second advantage was the feeling of actually having put in the miles. There is no “flying over” when you’re riding the Greyhound. I wanted to travel through the South, not over it. I didn’t want to limit my experience to just the cities. I wanted to see Texas flatlands, Tennessee woods, Louisiana swamps and wetlands, houses in the middle of nowhere, confederate flag bumper stickers and prolife billboards.

Some of my friends thought I was crazy. To them a Greyhound trip was a dangerous undertaking. Crazies ride the Greyhound. Someone might cut my head off while I slept. Others thought it would be a cool adventure; romantic in the way a cross-country motorcycle road trip is romantic, full of quiet insights and spectacular sunsets. I admit to feeling a mixture of their concern and excitement. Before leaving I wrote out a list of all the bad things that could happen to me in the middle of nowhere on a bus (dismemberment made the list). At the same time, I felt small stirrings of pride whenever anyone asked me what the hell I was thinking, crazy bastard.

I never lost my head and the only sunrise I saw hurt my sleep-deprived eyes. But the plan worked beautifully. I visited 9 cities in 18 days, and touched ground in every Deep South state except Florida. I saw plantations and battlefields, civil rights memorials, sites of tragic importance. I heard jazz bands in the street and got stuck in four torrential rainstorms. I saw a giant Trump billboard (only one). I even met a Buddhist gun enthusiast. And I was granted a few little insights.

But they didn’t come easy.

Selling Points

I would never recommend a southern Greyhound tour to anyone unless they are seriously committed to boredom and discomfort for a large portion of their vacation. Don’t get me wrong, it suited my purpose wonderfully, but I had already resigned myself to misery before I boarded my first bus. Let me explain.

The Greyhound is slow. The drivers have lead feet and fly down the highways and around turns at speeds that draw your attention to the bus’s top-heavy construction, but they still have to contend with traffic. Also they stop every 100 miles or so to pick up and drop off passengers. There is no copilot who can take over when the driver hears nature’s call. Oh, and god forbid your bus should be a scheduled connection for another bus route. It doesn’t matter how late the other bus is. There are no missed connections. An hour-long airplane trip becomes an 8-hour ordeal on the bus.

The Greyhound is uncomfortable. It’s not a cattle car like modern airplanes where the seats might as well be stacked on top of each other. There are usually fold down footrests, and there’s no seatbelt requirement. Most of the time everybody has a whole row to themselves. This doesn’t mean there’s really any room to stretch out. Even those who are flexible and small enough to curl into the fetal position and lie down are denied much rest by the constant bumping and lurching; the unending vibrations sent rippling across the bus frame by the powerful engine. For the most part, people sit up for the full trip, listening to music or staring out the window, heads bobbing with every dip in the road. Yes, planes are uncomfortable, but at least a flight only lasts a few hours. Most legs of my trip were over five hours long. Given enough time, even cushions will bruise an ass.

The Greyhound smells. I don’t care how clean people are when they start their trip. A lot of riders are making journeys over multiple days, camping out on station benches overnight, waiting for a connection, unable to do little more than wash their faces in a sink you wouldn’t want to wash your hands in. We all smell bad and the bus bears constant witness to our odors, carrying them for unending miles.

The Greyhound doesn’t really get you all the way there. In most of the places I visited the bus dropped us off far outside of downtown, so far that you can hardly be said to have arrived anywhere at all. Often I had to catch a cab or get on another bus to complete my trip. Only in the big cities was I dropped anywhere near an urban center, and usually it wasn’t exactly the kind of place you wanted to be as you took your first steps in a new town.

The bus drivers are… not always pleasant. Who can blame them? What I did for two weeks they do almost every day of every week, month after month, year after year.

No rave reviews. No two thumbs up. In spite of that the busses continue to roll down the highways 24/7.

Making Trail Ends Meet

In Dallas, the night after the police shooting, a huge section of downtown was cordoned off. The Greyhound station fell just within the bounds of the yellow tape. Everyone trying to catch a bus there had to travel ten miles to a remoter, smaller station southwest of downtown. The staff, tough to deal with even on normal nights, was mobbed with confused and panicking passengers. None of us really knew what was going on, where we were supposed to stand, what the status of the busses was. There was no point waiting in line to find out. It was too damn long. Calling Greyhound customer service didn’t help either since all they could do was recommend talking to the station agent. Plenty of people were waiting for busses that had not arrived yet, their delays stretching several hours. I didn’t know if my bus would be on time or even whether it would ever arrive at all. It was about 3 in the morning. A college aged white kid cast a tired, frustrated glare at everyone and everything. “I was trying to save money. My friends are already in San Antonio, but at this rate I won’t be there until noon. Next time I’m just buying a plane ticket. What a waste of a weekend.”

It was a totally understandable attitude. I’ve been in plenty of airports and experienced my fair share of air travel hiccups. I’ve stood around with fellow fliers as we shake our heads, cross our arms, and mutter “I cant believe this shit,” while airline employees scramble to extricate whatever wrench has been thrown in the works. Airlines lose baggage, over-book flights, lose reservations, and cancel flights. Customers complain and employees do their best to placate their angry clients, throwing in upgrades or not charging for bags. Because even though you’ll probably get gouged no matter which company you fly with, airlines compete for your business by making air travel as pleasant and smooth as possible. Customers talk, customers write reviews, and customers switch carriers.

The white kid in Dallas was making his dissatisfaction felt, casting it into the air where it would mingle with other people’s anger and hover over the ticket counter like a storm cloud, inspiring the staff to action. At least, that’s what might have happened in an airport. But it didn’t happen here.

Everyone else bore his or her frustration in quiet resignation. For them, there was no other option, nothing else they could have done. If they could have flown, they would have. If they could have driven, they would have. I remember a tired looking woman in Houston trying to remain upbeat and excited for the benefit of her young son. They were traveling to New Jersey to visit the boy’s father, a trip that would take a few days at least. She didn’t seem too excited to see the man. And yet they were going. This wasn’t a vacation for her. It was life. They weren’t the only ones in for long rides. Some people in New Orleans were Chicago and New York bound, on their way to visit sick family members or old friends they hadn’t seen in a long time. Passengers in Memphis were making trips to the coasts, to destinations in Florida and California, their reasons for travel unspoken. I saw college students leaving small towns, whole families on their way to Mexico, boot-camp bound recruits, grandparents nervously studying the connections listed on their tickets, disappointed looking European backpackers.

The Greyhound is the way to go for poor people who need to travel. Greyhound knows it. Poor people know it. There are no bus attendants, no drink service or in-drive entertainment. The most a passenger can hope for is an empty row, mellow travel companions, no traffic, a good-humored driver, and a beautiful view here and there. It’s not cruel or mean spirited. It’s bare bones. They cant promise that the world will cooperate with your plans, and they wont move mountains should it decide not to. But if you need to get from A to B, and you need to do it on a budget, you cant go wrong with the Greyhound.

The Origin of the Species

By Mark Dudzic

First published 14 August 2016 in:

First of the Month: A Website of the Radical Imagination

Back in the day, two knucklehead members of my old union local at a Union Carbide plant in New Jersey fashioned KKK hoods out of chemical filtration paper and paraded through the lunchroom on Halloween. The corporate HR executive sent to investigate summarily terminated both workers within hours of arriving at the plant. She loudly proclaimed the company’s “zero tolerance” to racial harassment.

Now this was very interesting considering that her employer was the prime suspect in the unpunished industrial murder of 764 mostly African American workers on the Hawk’s Nest Tunnel in the 1930’s and its current corporate chairman, Warren Anderson, was a fugitive from justice wanted by the Indian government in connection with the 1984 criminal manslaughter of at least 15,000 Indians in Bhopal. Over the next 15 years, the same HR exec who showed Phil and John the door was the point person in the shutdown of all three unionized Union Carbide plants in New Jersey, leaving behind a series of toxic waste sites contaminating communities throughout the state and 2,000 black, white and Hispanic workers, many suffering from uncompensated industrial diseases.

This episode comes to mind while contemplating the detritus of the Republican and Democratic conventions and the growing trope that the rage of the white (male) working class has propelled both the Trump campaign and the critique of the Clinton campaign from the left. The politics of race and gender often obscure much more than they reveal. It is true that individual white workers can be horribly racist and misogynist. But it is also true that the worship of “diversity” often serves as a cover for gross hypocrisy and ruthless class rule.

At the Democratic convention, diversity was rolled out in service of the status quo. Stripped of the soaring rhetoric of the Obama years, the neoliberalism of the Clinton variety fails to inspire or move people to action. “There is no alternative,” she proclaimed time and again during the campaign and at the convention, “so we might as well make the best of it and do what we can without upsetting the apple cart.” All of the energy inside and outside the convention hall came from the Bernie delegates who came prepared to fight for the issues and concerns of the people who sent them there. Even the concessions that the Clinton campaign made on platform issues had no real effect. No one really believes that Clinton will seriously oppose the Trans Pacific Partnership or work to institute a $15 living wage. Already she is moving to the right in an attempt to capture the refugees fleeing the new Trump-branded Republican Party. In more normal times, the rants of General Allen or, god bless them, the patriotic evocations of the bereaved Khan family, would have been much more at home at a Republican convention. Despite the deliberate celebration of diversity, we all left Philly knowing quite well what to expect over the next four years.

In Cleveland, the party of Trump was an altogether darker affair. Here diversity and it’s cousin “political correctness,” played the role that marginalized communities always play in right wing populist and revanchist movements: as a focal point for anger that would otherwise be directed against a social and economic order. Trump has mastered an appeal that combines Munich beer hall fascism with a kind of post-modern shock jock sensibility that doesn’t take itself all that seriously. It allows him to get away with the most outrageous statements that would have been the end of any traditional politician. He will never be president but he may succeed in destroying the modern Republican Party, which advanced a fundamentally pro-capitalist, neoliberal program by fanning racial and gender resentments, religious fundamentalism and populist anger at elites. To borrow a metaphor from Tom Frank, a whole lot of people don’t want to live in Kansas anymore.

It is interesting that many in the Republican establishment blame the white working class for the destruction of their party. The vitriol and sense of betrayal of the National Review crowd are truly remarkable. Trump certainly enjoys considerable working class support. For some workers, Hillary Clinton probably reminds them of that HR rep who forced them to attend “everyone is awesome” sensitivity training while secretly assisting in plans to move the plant to China (of course Trump not only symbolizes, he actually is that type of dickhead boss in the Frank Lorenzo-Jack Welsh-Carly Fiorina-Carl Icahn mold who runs the business into the ground while personally enriching himself and screwing everyone around him).

But the extent of Trump’s working class support is greatly exaggerated. Those workers at the Carrier plant in Indiana that Trump promised to stop from moving to Mexico? They’re members of the Steelworkers union who voted overwhelmingly to have their local endorse Bernie Sanders. Same with the Chicago Nabisco workers, primarily black and Latino and members of the Bakery Confectionary union. In fact, Trump voters have an average income about 20% above the median. I like to envision the typical Trump voter as an upwardly mobile fast food shift manager: making a crappy salary and working lousy hours with little hope for real advancement, but glad to be wearing a tie and away from the deep fryers, desperate to please the main office, envious of the life style of the local franchise owner and resentful and contemptuous of the lazy slugs they supervise who are constantly whining for more hours and better conditions.

Likewise, many in the Democratic establishment blame backward white workers for the success of the Bernie Sanders insurgency. Joan Walsh, among many others, opined that Sanders’ substantial support among white workers (who overwhelmingly supported Clinton in 2008) is because “she has been damaged by her association with the first black president”. And Paul Krugman, that eternal guardian of the left gate of the ruling class, pontificated that the Sanders campaign failed to understand the importance of “horizontal inequality” between groups. What the fuck does that even mean?

The “white working class,” like the “black community,” is an abstraction that does not exist anywhere in the real world. The U.S. working class is broad and diverse. It’s not even all that white any more and certainly not all that male. Its conditions are determined by its position within a political economy but, like everyone else, the experience and consciousness of individual workers is formed by a whole series of contingent relationships and experiences. The recent use of the trope of the angry white working class attempts to extract white workers from these class dynamics and present them as a demonized and marginalized natural group.

Adolph Reed has written extensively about the ideological and epistemological machinations that legitimize and stabilize regimes of hierarchy by transforming social relations into natural conditions. In the U. S., race, and its various ethno-subdivisions, has always been the great tapestry upon which this story has played itself out. Race science developed as an efficient sorting and control mechanism for capitalism and, in the 19th Century, embraced Darwinian and Lamarckian evolutionary theory to lend legitimacy to the ideology (late 20th century racialists incorporated more modern genetic theories into the mix). While the old racialist model persists to this day, the integration of various ethnic groups into the great American middle class and the successes of the civil rights movement compelled most mainstream ideologists to move to a newer version that incorporated speciation theory. This new model emerged in the 1980’s with the discovery of the black underclass. Just as Darwin’s finches evolved into unique species on their isolated Galapagos islands, so did social Darwinists identify a black underclass culturally and economically isolated from the rest of us (Trump, by the way, had a bit to do with naturalizing this new model. He made his bones as a rabid proponent of the “wilding” hysteria that, in 1989, helped to frame 5 black and Hispanic youths for the rape of a female investment banker who was jogging in Central Park.)

In the U.S., class relations per se have rarely been naturalized. Instead, the ideological consensus was that most Americans become subsumed into a broad middle class with the exception of a few culturally marginalized populations. But now we are witnessing the evolution of a new species: white, blue-collar workers unable or unwilling to transcend their dead-end jobs/communities who are acting out in self-destructive and dysfunctional ways that undermine the very foundations of political stability. The underclass descriptors are remarkably similar: OxyContin for crack, social security disability for welfare dependency, family dysfunction and sexual profligacy (Kevin Williamson’s stunning invective against a “white American underclass in thrall to a vicious, selfish culture whose main products are misery and used heroin needles” engaged in “the whelping of human children with all the respect and wisdom of a stray dog” could apply equally to either species).

Then there’s J. D. Vance’s best-selling memoir, Hillbilly Elegy. In a style that fans of every racial uplift story since Manchild in the Promised Land will immediately recognize, Vance relates the massive dysfunction of his working class Ohio background and his personal overcoming through pluck and hard work. As the New York Times points out in its review, Vance subscribes to the Obama “brothers should just pull up their pants/stop feeding Popeye’s to your kids for breakfast” school of thought that “hillbilly culture…increasingly encourages social decay instead of counteracting it.”

This new species has an irrational fear of globalization, a perverse sense of entitlement and a worldview colored by racial and sexual resentments. In the conservative account, they have only themselves to blame–social programs will just exacerbate the culture of dependency and only a strong dose of religion or family values backed by the punitive and carceral powers of the state can nip this inferior species in the bud, reintegrating its more robust members into the great American phenotype. In the liberal view, it is actually the evolved racism and other entrenched attitudes of this species that prevents progressive change. It’s as if my two knuckleheaded union brothers were actually the ones responsible for Union Carbide’s legacy of racist industrial homicide. There’s no real solution to this problem because this racism and sexism is actually part of the DNA of the species rather than embedded in a political economy. We can only hope that the species self-extincts as its more enlightened members move to Seattle and Silicon Valley to become baristas and uber drivers as the others obliterate themselves with drugs, alcohol and guns. Either way, one thing is clear. They. Are. Not. Like. Us.

The Sanders campaign was so disorienting to both conservatives and liberals because it did not embrace these naturalized categories but, instead, revealed them as social relationships established by real human beings and, thus, open to change through the application of political and economic policies. After stumbling a bit in the early months around how to give voice to the outrages of police violence and mass incarceration, it laid out a working class politics of hope that was both visionary and practical. In the process, it helped lay bare the actual mechanisms of capitalism that drive inequality. And it exposed the fault lines created by decades of neoliberalism that are impeding real change in the labor, racial justice and other social movements.

The tasks ahead should be clear: first decisively defeat Trump and everything he stands for. Then immediately pivot to attack the neoliberalism that will be at the core of the new Clinton Administration. Failure to do so will doom us to decades more of a politics of cynicism, divisiveness and corporate rule over every aspect of human existence.

One thing for sure, it’s going to be an interesting ride…

The Fight for $15 and a Union – A movement in the making?

By Peter Olney and Rand Wilson

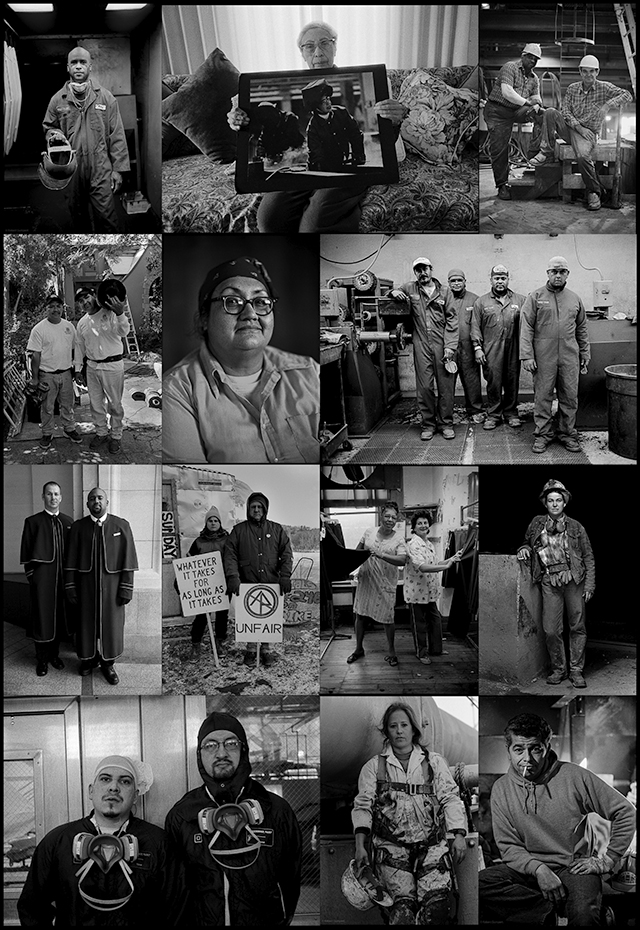

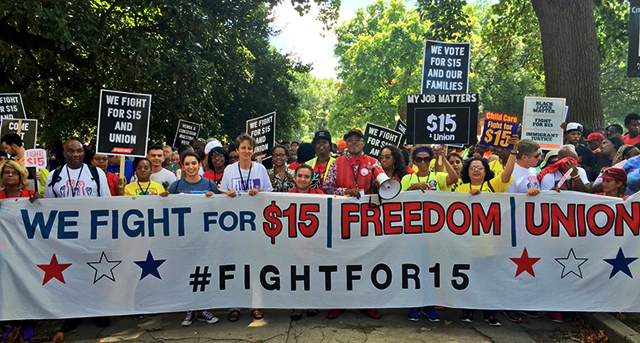

“Fight for $15” convention closed with a march on the Robert E. Lee monument that symbolizes racial supremacy. Photo: SEIU

After both the Republican and Democratic parties nominating conventions, there was a convention of a very different kind in Richmond Virginia on August 12 and 13. Thousands of low-wage workers and activists from all over the United States gathered for a Fight for $15 convention. The convention highlighted the links between the Fight for a $15 minimum hourly wage, economic equality and the struggle for racial justice. The selection of a venue in the capital of the Confederacy was no accident, and the convention closed on Saturday with a march on the Robert E. Lee monument that symbolizes racial supremacy.

This meeting was another movement-building step in the fight for a $15 per hour minimum wage. The Reverend William Barber, who only a few weeks before ignited the Democratic convention in Philadelphia with a blistering speech during prime time television, spoke at the closing rally and talked about the legacy of slavery and its connection to lingering poverty and other social problems.

The United States federal minimum wage was first established in 1938 at $.25 per hour. Over the years since, the minimum wage has been increased to $7.25 per hour, a totally inadequate living standard anywhere in the United States.

States (and some municipalities) are free to enact higher minimums, and states and cities with strong labor unions and progressive politics have done so. For example, the minimum wage in Massachusetts is now $10 and hour and in Michigan it is $8.50. The City of San Francisco has a $13 minimum wage. The states of the old Confederacy have the lowest minimums and have resisted grassroots efforts to raise them. Birmingham, Alabama recently raised its minimum to $10.10 but the raise was preempted by the Republican-dominated state legislature.

Both California and New York have recently raised their minimums to $15 per hour; phased in over 7 years to 2023 in California, and in greater New York City by 2021 and in the rest of the state in graduated fashion after 2021. While even these minimums are still a paltry income for struggling working class families, the change in minimums and the societal recognition of the need to drastically raise wages is a long overdue and welcome development.

The Service Employees International Union (SEIU) with almost 2 million members, mostly in the public sector, has been responsible for funding and leading the Fight for $15. Without its backing and national coordination, the one day strikes against McDonald’s and other fast food outlets would not have happened. One-day strikes began in 2012 and on August 29 of 2013 there were walkouts at fast food outlets in over 60 cities. The walkouts usually were by only a small percentage of the employees in each outlet, but members of SEIU and other unions along with community groups bolstered the strikes with large public rallies and demonstrations of support.

The actions were often characterized by observers as a “march on the media” rather than an actual march of the fast food workers themselves. Nevertheless, these actions generated a public “buzz” and put pressure on McDonald’s and the other fast food employers to raise wages. In early 2015 McDonalds’ announced that it would raise the company minimum for thousands of its employees.

the key to securing power for workers in this industry (as in other retail organizing) is building strategic power higher up in the industry’s supply chain

The Fight for $15 campaign has not yet been able to compel McDonald’s or any of the other fast food restaurants to recognize the union as the bargaining representative of its employees. It is often unclear how many workers actually remain involved in the day-to-day union organizing. Employee discipline and terminations in retaliation for supporting the union are rampant, and it is hard to defend discharged workers under U.S. labor law. Turnover in employment is high. Actual worker organization is thin. But the Fight for $15 driven by SEIU and supported by significant community-based forces has had a remarkable role in shifting consensus on US wage policy. No longer do the neo-classical supply side economists dominate the debate arguing that a rise in minimum wages will destroy jobs and the economy.

Historian and labor organizer Marty Bennett has pointed out that prior to the Fight for $15, there is a history of initiatives which have contributed to this sea change in public opinion:

• In 1996 the City of Baltimore, pressured by labor and community organizations, passed one of the first “Living Wage” ordinances mandating that businesses receiving city contracts pay more than the minimum wage. Los Angeles did the same in 1997.

• In 2011 “Occupy Wall Street” protests in cities throughout the U.S. targeted the growing economic disparity between the top 1% and the rest of the 99%.

• In 2012, the Fight for $15 and a union was launched with strikes at fast food outlets throughout the US.

• In 2013, SeaTac, a small city halfway between the cities of Seattle and Tacoma that encompasses the Seattle airport, passed a $15 minimum. In 2014 and 2015, San Francisco and Los Angeles followed suit.

• Bernie Sanders’ campaign for President explicitly called for a $15 federal minimum wage and pressured Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton to adopt $15 in the Democratic Party Platform.

As Fight for $15 advocates gathered in Richmond, Virginia for their convention, they celebrated the remarkable advances they have made in shaping the national dialogue; moving it away from austerity and to a focus on economic inequality. They also celebrated their part in a larger movement to significantly raise the minimum wage, impacting millions of low wage workers through state and municipal increases.

SEIU has made a remarkable commitment, putting enormous resources behind the fast food workers so they can pressure their employers for higher wages. But despite its short-term impact and success, the campaign has yet to build sustainable worker organization. Clearly the high turnover and the huge number of scattered franchised job sites make an enduring worker organization extremely difficult to maintain.

From the standpoint of union organizers committed to building strong worker-led, democratic unions, the key to securing power for workers in this industry (as in other retail organizing) is building strategic power higher up in the industry’s supply chain. The better off workers in company-owned and third-party warehouses and trucking companies who supply the goods to fast food outlets may make for more sustainable organizing even if they are far less glamorous. In turn, these “pinch points” in the supply chain are where key workers once organized can exert the strategic leverage to win organizing rights for the millions of workers who labor in the fast food restaurant industry.

Our Revolution is just getting started

By Peter Olney and Rand Wilson

Now that the Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia has ended with Hillary Clinton as the party’s nominee, Bernie Sanders’ campaign for “political revolution” moves to its next phase.

Everyone who supported Labor for Bernie is very proud of the of the unprecedented grassroots effort to rally rank-and-file members on his behalf. A network of tens of thousands of supporters (largely recruited via the Labor for Bernie website and social media), campaigned in nearly every union to get trade union organizations to endorse Bernie.

By the end of the campaign, six national unions and 107 state and local union bodies endorsed Bernie. Just as importantly, Labor for Bernie activists kept many Internationals and the AFL-CIO on the sidelines during the primaries; enabling their members to more actively support Bernie.

But it wasn’t just about endorsements. Labor for Bernie was an all-volunteer army; a movement of members and leaders who took on the labor establishment. Labor for Bernie activists formed cross-union groups in dozens of states and many cities. They generated strong working class support for Bernie’s candidacy and carried his message into thousands of workplaces. They worked independently of the Sanders campaign, but in tandem with it.

Particularly in the later primaries (WI, IN, PA, CA) workplace outreach helped to identify new Bernie supporters and get them to turnout on Primary Day. In many states, the majority of union households went for Bernie, often accounting for his margin of victory.

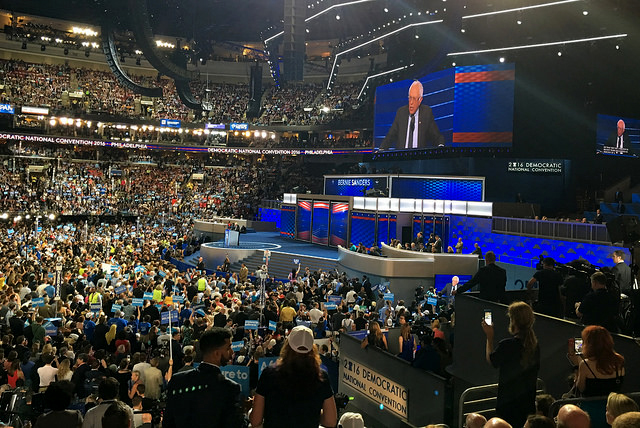

Democratic National Convention

More than 250 Labor for Bernie delegates from 37 states attended the Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia (and undoubtedly there were many more). Labor for Bernie leaders played a key role in fighting for a more progressive platform and for changes in the rules that could make the Democratic Party a more open and populist party in the future.

These changes were negotiated between the Sanders and Clinton campaigns just prior to the convention. As a result, there was little for the Sanders’ delegates to do at the convention. Yet despite the compromise agreement on the platform, there was widespread concern among delegates that the platform didn’t have strong enough language opposing the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP).

A Labor for Bernie leader from Illinois printed up 2,000 “No TPP” signs. The printer folded them twice so that our network of delegates could more easily smuggle them onto the convention floor.

When the platform came up for a vote, Labor for Bernie helped orchestrate “No T-P-P” chanting by the delegates that briefly brought the convention to a standstill. It captured the attention of the national news media.

Outside the convention there were spirited mass rallies in support of Bernie’s candidacy and the environmental and labor issues brought forward during the campaign. National Nurses United organized a forum on Medicare for All. Union supporters held a forum on organizing to stop passage of the TPP during the Congressional “lame duck” session after the November 8 election.

The small but feisty Working Families Party hosted a forum with speakers discussing ways to build an autonomous and independent faction inside the Democratic Party. Democratic Socialists of America had a standing room only session on the lessons of the Sanders campaign.

Delegates were grouped by their state both on the convention floor and in their hotels. There were obvious and deep differences in the political perspectives of the Sanders and Clinton delegates. One group apparently satisfied by the status quo in the Democratic Party, the other determined to change it. Sanders’ delegates often felt they were “crashing” someone else’s party.

Just prior to the start of the convention, WikiLeaks revealed emails showing widespread favoritism and manipulation by the Democratic National Committee to assist Clinton in the primaries. This confirmation of what many already suspected enraged many Sanders delegates and at times tensions flared in arguments both about the conduct of the party and debates on the issues.

The shared experience among the 1,900 Sanders delegates may be the one of the most important lasting outcomes of the convention.

The political revolution doesn’t end in Philadelphia

Union members allied with Labor for Bernie now face the dual challenge of decisively defeating Donald Trump and stopping the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) treaty.

Yet, as Bernie argued at the Convention, we can’t allow this election to become only about the differences between Trump and Clinton. Wherever possible, we have to continue to inject our issues into this general election campaign.

And that’s where “Our Revolution,” a new organization that is emerging from the Sanders’ campaign, comes in. It will continue to bring together a new majority for economic and social change by supporting candidates at the local, state, and national level who support the mission, issues and values of the Sanders campaign.

Sen. Sanders will provide more specifics in a “live stream” video presentation set for the evening of August 24. Many of Bernie’s volunteers in the labor movement will be hosting events in their union halls or living rooms to help kick off “Our Revolution” and lead this effort.

The Sanders’ campaign showed how unions might engage in politics in ways that enhances membership involvement and organizational clout, rather than reducing it. When labor organizations decide to endorse candidates, after a democratic process open to the entire rank-and-file, it changes the whole dynamic of union-based political activism. As a labor network strongly in favor of this approach, there will be a continuing need at the local, state, and national level to back electoral campaigns inspired by Bernie’s run for president.

Wilson’s pictures from the convention are online here

Looking back, looking forward Resolving the left impasse over elections

By Kurt Stand

Prologue

“The policy of “the lesser evil” strengthens the feeling of power of the reactionary forces and is supposed to create the greatest of all evils: the passivity of the masses. They are to be persuaded not to make any use of their full power outside of Parliament. Thus the significance of Parliament for the class struggle of the proletariat is also diminished. If Parliament today, within limits, can be used for the workers’ struggle, it is only because it has the support of the powerful masses outside of its walls.

…

The most important immediate task is the formation of a United Front of all workers in order to turn back fascism. … Before this compelling historical necessity, all inhibiting and dividing political, trade union, religious and ideological opinions must take a back seat.”

Fascism Must be Defeated; Opening Address to the German Parliament, August 1932, Clara Zetkin, Communist Party of Germany (KPD).

Differences

Organizing success requires establishing a framework that enables individuals to express their distinct voices in combination with others in an expanding circle of mutual support. The goal – to form a union, stop police violence, prevent off-shore drilling, cut military spending – brings people together around a particular goal even though personal motives, immediate concerns, long-term aims will vary greatly. The success or failure in any given campaign resides in how close it gets toward its principle objective, and, crucially, whether people remain engaged after an initial effort meets with success or failure. Win or lose, the next step almost inevitably entails reaching out to those who stayed on the sidelines, advocated a different approach or stood in opposition in order to build strength for whatever follows.

Few activists would dispute the above – except when it comes to elections. Then the tendency is for activists to see those charting a course different than their own as opponents or roadblocks rather than as individuals or communities whose outlook and participation is needed for success, however measured. It is a blindness well in evidence this campaign season.

Bernie Sanders’ endorsement of Hillary Clinton is viewed by some as a long overdue acknowledgement that he lost the primary battle and as the needed last step to unify the Democratic Party and progressive opinion in order to defeat Donald Trump come November. From this perspective, those who refuse to go along are opening the door to the most dangerous right-wing demagogue we have faced in our time. The hateful speeches that characterized the Republican Convention only amplified that view. From another perspective, Sanders’ endorsement is a betrayal of his program, and of the voters who supported him. Such critics charge that he succumbed to a pragmatic opportunism which will reinforce corporate neo-liberalism. Clinton’s pick of Tim Kaine as her running mate, underlines her Wall Street agenda and give credence to those who argue that she is not a progressive alternative to Trump.

From either point-of-view, the need to create a “united front” across ideological lines, while rejecting politics of the “lesser evil,” remains not only unmet but barely acknowledged. Curiously, one salient fact is often ignored: Sander’s success in reaching millions, putting inequality at the center of politics, bringing the term socialism back into public discussion and generating widespread enthusiasm for a “political revolution” grew from working within the Democratic Party without being beholden to it. This inside/outside organizing helped establish a genuine unity (that is unity between those with clashing perspectives), without sacrificing principles.

It is a lesson lost when the valid point that there needs to be the widest possible unity of working people in order to confront and defeat Trump is joined to the argument that Clinton has now adopted the social justice policy positions she refused to previously advocate. An example of this thinking can be seen in an article by Sanders supporter Gene Grabiner:

“Hillary cannot run a center-right campaign. If she does, she will lose. And she knows that. And if she wins the election, she cannot govern as a center-right president. That’s because she’ll need to govern on a program which is substantially Bernie’s, and which responds to the needs of the masses of the people and the movement that Bernie’s candidacy has built. That being the case, Bernie will campaign for her. And she will have to deliver.” (To All My “Bernie or Bust” Friends: Worse Is Not Better)

Certainly there is nothing progressive about her projected foreign policy. Moreover, Clinton’s insistence that she would achieve the domestic aims outlined in her acceptance speech by reaching across the aisle to Republicans calls into question any guarantee of a progressive campaign or Administration. Sanders made a different argument – legislative progress on a progressive agenda is only possible through mass pressure. By contrast, Clinton undervalues the groundswell of activism by Sanders supporters and replaces it with a passive politics dictated by professionals. Beyond speculation as to how she might govern lies the reality that people were inspired by Sanders as an alternative to Clinton, so it is making a huge leap to expect them to see her now as the embodiment of their hopes.

Others argue that Trump can’t win or that it is a matter of indifference whether he or Clinton is in office next year. Behind this lies the disempowering notion that a candidate’s relationship to corporate power and elite opinion matter far more than popular opinion. An example can be found in an article by Steve Bloom (and signed by a number of other activists) who writes:

“A victory, with our support at the ballot box, for someone who espouses a less-blatantly racist imperial agenda still strengthens the hand of the imperial rulers of this country, and of the state which upholds their interests. This electoral tactic/strategy has been tried often. It has not once led to a leftward shift in the establishment political discourse as its proponents consistently insist that it will, not even when the candidate they call on us to vote for wins and takes office. Indeed, any such “victory” tends to simply compound the problem by making the calls by the rabid right even more strident. Note, as a clear example, the emergence of Trump after eight years of an Obama Administration.” (After Bernie – Electoral Strategy for the Left in 2016)

Of course, those eight years also saw the emergence of Occupy and Black Lives Matter –and Sanders garnering the support of millions. More important, this line of reasoning ignores the impact on whole communities – now as well as in the potential future – of his open racism, xenophobia and misogyny. Trump’s candidacy relies on mobilizing white voters to the exclusion of all who look, think or act differently; Clinton’s campaign relies on mobilizing a multi-racial, multi-ethnic coalition of women and men of different sexual identities, different backgrounds. Trump’s proposals on domestic and foreign policy, while within the standard right-wing frame, add a call to “defend” (white) workers against workers in other countries, against the interests of black and Latino communities in the US; whereas the Democratic Party platform, for all its limitations, puts forward a defense of existing social programs as providing security for all. These are distinctions that should matter to proponents of social justice, of socialism.

Moreover, Trump demonstrates open contempt for civil liberties with his advocacy of torture, of violence against opponents. Beyond the “liberal”/ “conservative” business as usual divide in US politics, Trump’s campaign needs to be confronted as a threat to democratic rights in and of themselves. To treat such rhetoric in a cavalier fashion reflects the liberal illusion that our rights – however limited they may be – can never be truly imperiled. And it treats concerns that might be raised by voices within communities targeted as a matter of secondary importance, an outlook unlikely to build a movement reflective of the working class in its full diversity.

Yet such criticism should not be taken as a dismissal of the legitimate anger behind the argument – to say that Trump needs to be defeated is not sufficient reason to ignore Hillary Clinton’s militarist assertion of US power abroad, her ties to Wall Street, her support for the death penalty, or her consistent opposition to universal New Deal type social programs in favor of means-tested plans that deepen inequality. Moreover, and a key difference between her and Sanders, is that Clinton rejects independent initiatives or critical opinions. Support from unions and other social justice organizations is welcome only so long as they stay “on message,” as though elections were sales campaigns. This has nothing to do with democratic participation or democratic accountability. Of course Trump is more dismissive of democratic norms, mobilizing people on the basis of fear, hatred, and his “infallibility.”

Defining a social justice agenda primarily in reaction to Clinton (oppose her, back her), or Trump (fight him, ignore him), allows the dominant two-party system to set the tone, reduces independent politics to slogans without substance. Failure to look at the whole political environment rather than any one aspect of it, has led to lost opportunities in the past.

Germany 1933

Oft-repeated as a warning sign of what to avoid was the inability of Social Democrats and Communists to unite to stem the Nazi march to power. The value of such unity is so obvious that it might behoove us to look deeper into the matter as to why it didn’t happen. Calls for joint action were made at the time by some leading Communists and some left-wing and simply open-eyed Social Democrats. So too independent left parties and publications in Germany called for unity as soon as the fascist danger became manifest. But such calls failed to gain traction as a political force because they were unconnected to existing popular currents.

Whereas, though flawed — and ultimately fatal — both the KPD and the SPD pursued reasonably coherent strategies that made sense to their supporters (reflected in the consistency of their respective areas of pre-1933 strength in the immediate aftermath of World War II). Communists focused on building a broad base of support through organizing mass public rallies and demonstrations, by establishing workplace and community organizations. The denunciation of Social Democrats as social fascists was a particularly short-sighted, self-destructive aspect of this, but the KPD’s tactics in the early 30s was consistent with their tactics in the early 20s when they sought agreement with the SPD and all other worker/Marxist parties in the country. During most of the Weimar years, no matter what the “political line,” German Communists acted on the belief that the working-class could be brought together across lines of division by maintaining the maximum degree of flexibility in action, flexibility unencumbered by limitations inevitable if parliamentary compromise was given equal weight.

Campaigns against rearmament, to end the nobility’s remaining privileges, for abortion rights, to prevent evictions or prepare militant strike action were practical applications of a strategy designed to mobilize around reforms of immediate consequence to working people. In practice, this entailed recognition of the need for compromise, for effective action in parliament. What they failed to recognize is that even success in particular struggles would not lead people in their majority to abandon those institutions and political parties of which they were a part. KPD calls for unity became hollow because the legitimacy of other perspectives and thus of other loyalties was denied. Over-estimation of the strength of mass action in a vacuum left them unable to effectively resist loss of the institutional space within which organizing took place – left them unable to see that those who worked strictly within the limits of constitutional order had a logic that needed to be acknowledged if a genuinely radical alternative was to prevail.

The Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) charted an opposite course. They believed that defending the Weimar Republic was necessary to protect or extend practical reforms enacted at its founding – improving public education, constructing working-class housing, providing unemployment relief, establishing union rights. But fearing the fragility of the parliamentary system, they rejected calls for popular mobilizations on behalf of their programs as they came under attack by big business interests, conservative and middle-class parties and “popular” fascist forces. The box they were already in narrowed once the depression hit. Bowing to the logic of the system they defended, the SPD pursued a politics of trying to limit rather than resist cuts. Even this was undermined for defense of social reforms without social upheaval led to their casting a blind eye at the danger (and fiscal cost) of renewed militarism. Thus the SPD became complicit in the process that undermined them as evidenced by their support of Hindenburg (who was to make Hitler Chancellor) in 1933.

Ultimately, the decision to compromise with existing power under threat of the destruction of Weimar made them intractable opponents not only of Communists but of all others on the left seen as furthering instability at a time when stability had become a goal in and of itself. But support for the then existing Constitution and the rights enshrined in it would have only been possible by uniting with those engaged in extra-parliamentary struggles. Joint action would not have made the profound differences with such groups vanish, but joint action to defend rights under threat could have allowed the parliamentary system and civil liberties survive. Privileging the existing order over all else meant condoning reactionary German nationalism, condemning other workers’ parties, it meant isolation. For the SPD a united front became undesirable, the only supporters wanted were those with shared politics.

The failure on each part did not lie so much in the pursuit of distinct strategies. Instead their mutual failure lay in the inability to include within their particular strategies the perspectives of each other. An understanding of the interdependence of parliamentary and extra-parliamentary politics could have created the basis for recognizing that the frequent contradiction between the two did not make their proponents enemies of each other. The retreat into a politics of either-or not only meant an inability to unite, it also meant an inability to break into the broad support the Nazis were able to gain within sections of the working-class and amongst broader sections of the middle-class – for the insularity of Communists and Socialists (even with their millions of supporters) left each without strength to make meaningful an alternative to those outside their circles of influence. Unity means not allowing real differences prevent solidarity and it means building outwards from whatever points of convergence do exist.

United States 1968

Divergence instead of convergence was found everywhere in 1968. One of the many dilemmas those opposed to the Vietnam War faced early that year: support Robert Kennedy or Eugene McCarthy. Kennedy had a base in the labor movement and the black community that McCarthy did not have – a clear reason to prefer him. But McCarthy was running largely outside the apparatus of the Democratic Party, opening up space for independent politics in a way Kennedy wasn’t.

In New York City, for example, a reform Democratic Party movement was challenging the entrenched machine over local issues ranging from low-income housing to school integration, but with an added dimension because reform/establishment lines also reflected division over the Vietnam War. Contra-wise, Kennedy’s past ties with that machine meant that he received their support. Most reformers therefore backed McCarthy, connecting the dots between local political corruption and the corruption of national politics.

But that was a logic that did not hold everywhere – one of the many counter-examples that can be cited was Kennedy’s clear and unequivocal support for the United Farmworkers, still in the midst of a national grape boycott. Farmworkers and their supporters saw Kennedy’s campaign as providing an opportunity to build progressive coalition politics in California, an opportunity McCarthy’s campaign did not afford as he stood largely aloof from movements of dispossessed communities (a history that gives context to Dolores Huerta’s support for Clinton this year).

So the decision to back an “uncorrupted” outsider or a liberal who could be “effective” wound up being defined more by local than national needs – choices that became absolute and thus exclusive. A decision to support Gene McCarthy would have been more meaningful if joined to a determined critique of the limitations of his program, of his base of support. So too, a decision to support Kennedy would have had more value if joined to an effort to unhitch his campaign from the Democratic Party regulars who sought to dampen independent initiatives. But there was no popular basis anywhere for such a scenario. Supporters of the two were not interchangeable and there was never any synergy between their campaigns – and only a very uneven connection to protest and resistance movements unconnected to the primaries.

The cost of organizing against each other became evident when the general election provided a different set of choices. Kennedy was assassinated and McCarthy’s single note anti-war campaign became ever more marginal. Their supporters splintered in a thousand different directions, some mainstream, others radical, many back into a non-political life. Police violence at the Democratic Party Convention in Chicago, the culmination of a season of growing reaction (which had already taken Martin Luther King Jr.’s life), added to the confusion over which way to turn.

A fearful Democratic leadership choose Hubert Humphrey as the candidate against Republican Richard Nixon. To support Humphrey meant accepting Lyndon Johnson’s anointed successor – a Johnson who looked much different at the time then today because of the Vietnam War, because of his attempt to control the civil rights movement. Humphrey’s anti-Communist liberalism, a liberalism that feared and decried grassroots mobilization, had the support of a labor movement under arch-reactionary leadership and a narrow crust of civil rights leaders unwilling to oppose the war. They formed a coalition that sought to stifle reform possibilities within the Democratic Party that opposed all manifestations of radical dissent.

Humphrey was the last expression of a liberal “consensus” that had completely fallen apart. He was unable to match the malevolence of Nixon who set into motion the break with post-war Keynesianism, laid the groundwork for weakening hard-won civil liberties/civil rights gains and helped create the legal and ideological framework for what would become, decades later, our system of mass incarceration. The roots of the Republican Party transformation into the party of Reagan was as much a consequence of Nixon’s six years in office as it was of Goldwater’s failed 1964 campaign. The drift to the right was also apparent in George Wallace’s independent bid for President. Running on a pro-war, segregationist, “law and order” platform he won 13% of the vote – anticipating in its own way the appeal of Trump.

Left independent candidates ran presidential campaigns as well: Peace and Freedom’s Eldridge Cleaver, Freedom and Peace’s Dick Gregory, the Communist Party’s Charlene Mitchell, the Socialist Workers Party’s Fred Halstead. Though each was associated with the surge of radical protest at the time, none came close to being an expression of that protest. Yet electoral insignificance notwithstanding, protest and liberation movements, in their challenge to the imperial system, to racism, to capitalist exploitation and alienation were able to advance the cause of reform and set in motion a process of social (and personal) transformations upon which subsequent movements – including those of today – stem. The radical left, however, failed to establish an institutional framework able to survive setbacks or changed social and economic conditions.

For the left and liberals alike, a failed opportunity that has come at a steep price.

A Return to Today

Choices on display in 1968 have been replicated ever since. Some work in the Democratic Party as an alternative to Republican misrule, others aim to reform the Democratic Party. Those who judge such reform impossible strive to build a progressive Third Party, or, instead, stay focused on workplace, community or issue-based organizing.

Yet, unlike 1968, those differences have been largely artificial, rarely spilling over into social movements. Even the Gore/Nader divide, for all the intensity of the argument between supporters on either side, did not lead to splits, internal upheaval or leadership challenges within social justice organizations. That reflects the arid quality of election time debates as they become repetitive. Such arguments trap people in time and inhibit the ability of progressive working-class politics to take the initiative away from neo-liberalism in its liberal or right-wing guise; contributes to our inability to go beyond resistance to social injustice toward social transformation. Politics are only effective and radical if they address society’s complexities and changes.

In today’s moment this means confronting and defeating Donald Trump; all sophistries aside, that can only happen by electing Hillary Clinton as president. Trump normalizes overt racism, and if nothing else, that is sufficient reason for taking seriously the choices for November. But support for Clinton should be combined with opposition to any part of her program that reinforces corporate economics, military interventionism, undemocratic policies and practices – opposition to TPP, support for Palestinian rights, a ban on fracking, solidarity with Honduras, should not be put on hold.

Saying this doesn’t make an enemy of those concerned that criticism of Clinton will help Trump, nor does it make an enemy of those who back Jill Stein. That logic, however, goes both ways. Supporters of Stein who aim their fire at Clinton supporters undermine any project for building a sustainable social justice movement, Clinton supporters who condemn all who don’t embrace her undermine their objective of unifying to defeat Trump.

We will find a path to organize against the neo-fascist danger posed by Trump without surrendering to Clinton’s neo-liberalism when we link election activity to ongoing activity within and through existing popular movements and social justice organizations. Doing so can also allow us to speak to some Trump supporters without making any concession to his racism, with according any legitimacy to his politics. Choices we make depend on circumstances not of our own making; independence flows from what we do with those choices — build solidarity rather than proclaim it, speak to popular intelligence rather than in slogans, connect our work toward improving life in the present to a strategy for a future that is free because equal, democratic because inclusive, secure because just.

And Tomorrow

A strategy to realize that vision, to contest for power, to sustain the “political revolution” long-term requires a national organizational form – a framework that combines seemingly opposed currents of activism, give unified scope to multiple voices, link multiple levels of engagement. Too often work in election campaigns dissipate almost as soon as concluded, win or lose – unlike in other kinds of organizing for reasons noted above. This time may be different, especially if Sanders’ planned initiative to maintain the network of supporters of the “political revolution,” can maintain a balance between independence and connections beyond itself. A small step in that direction was taken at the People’s Summit in Chicago this past June. Beyond that central to whatever takes place next must be an ongoing connection to the organizations that supported Sanders – the National Nurses Union, Communications Workers of America, Working Families Party, USAction, Democracy for America, MoveOn.Org, Progressive Democrats of America, Democratic Socialists of America and scores of other organizations, local and national, large and small.

Turning to the more recent past, we have an example of what such a formation could look like in the Rainbow Coalition, built around Jesse Jackson’s 1984/88 presidential runs which anticipated Sanders’ inside/outside strategy. The political self-conception of the Rainbow was defined by Jack O’Dell, a leading Jackson (and previously, King) advisor:

“The Rainbow Coalition represents the Peace and Justice movements for social change entering the electoral arena, as an independent force.

The Rainbow Coalition is a mass political movement, committed to an expansion of the definition and practice of democracy in our country including the realization of economic justice. As such it has to be bold enough to perceive itself as the historic replacement for the existing two-party system: one prepared to act as a “dual authority” carrying out political education, developing the public’s insights into the systemic character of many of the nation’s problems, and consequently proposing solutions to these problems that are germane.

The Rainbow should be guided by the strategic objective or goal of effecting a basic political realignment favorable to the ascendancy of the progressive trend and its political program.” (The Rainbow Coalition Organizational Principles, 1985).

Though not fully realized it achieved an enormous amount on the basis O’Dell articulated – reform within organized labor, gains for the women’s movement, expanding support for peace and global solidarity, new linkages for environmental organizations, connections to farming communities. Such impacts were beyond any reverberations flowing from Nader’s campaign, beyond the impact made by mainstream Democrats like Bill Clinton and Al Gore.

Yet the Rainbow didn’t survive, in large part because the changes which it helped further were still at too early a stage of development, thus individual leadership choices loomed too large in its growth and decline. The process of internal change within social justice movements and links between them have, however, become more rooted in subsequent years. Meanwhile, layers of inequality are more marked, more rigid, in the 21st century than in preceding decades, leading a new generation to understand that change to be meaningful must be systemic. And waves of activism since Obama’s election have demanded positive changes, a contrast to the Reagan era when such activism was on the defensive. Thus there is a stronger base within society as a whole to carry forward Sanders’ politics, as compared to what Jackson supporters faced during the 1980s.

But the Rainbow had strengths that Sanders lacked – it was truly multi-racial and multi-ethnic in its leadership, electoral support, activist base. This was not a matter of program – in many ways the Rainbow’s was similar to Sanders, centered on universal programs to advance economic justice and democratic rights. Rather it has to do with the fact that African-American, Latino, Asian-American, Mid-Eastern, Native communities were full participants in setting the Rainbow’s agenda and defining the movement.