Organizing the Unorganized and Union Transformation – An Interview with Jeff Hermanson

By Peter Olney

“It is in the struggle to organize the unorganized and to empower the rank and file that the US labor movement will be transformed.” Jeff Hermanson

I remember hearing Jeff make this statement countless times in discussions of organizing. Hermanson brings a long and impressive bio to the labor-organizing table. He has been the director of organizing for multiple organizations: the International Ladies Garment Workers Union, the Writer’s Guild of America West, the NYC Carpenters District Council and Workers United. His organizing successes cross national boundaries, and he is now working as Organizing Director with the Solidarity Center in Mexico.

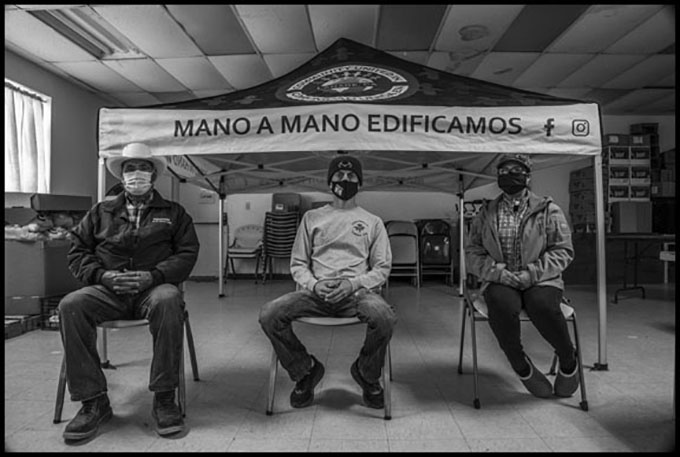

Peter Olney (PO) What does your organizing look like right now in Mexico?

Jeff Hermanson (JH) Working with Mexican unions and workers’ rights organizations, we are planning and supporting a major organizing program to transform the corporatist Mexican labor relations regime dominated by pro-company “protection unions” through organizing with existing independent and democratic unions (most of which are enterprise unions that up to now have shown little desire to organize beyond their factory walls), and by supporting the formation of new independent and democratic unions with an industrial outlook. In the few industries – petroleum, railroads, electric energy, education – where there are national industrial unions, a legacy of nationalized industries weakened by privatization, and for the most part controlled by entrenched and undemocratic leaders, we will support democratic movements within the unions.

Our aspirational model is the CIO mass organizing of the 1930s, which demonstrated the thesis that reform of a labor movement requires new organizing to break the hold of the dominant ideology – craft narrowness in the AFL of the 1930s, anti-communism, protectionism and business unionism in the US of the 1990s, corporatism, corruption, nationalism and enterprise unionism in the Mexican labor movement of today – and create a new paradigm of inclusive, militant, internationalist industrial unionism.

(PO) What about some of your experience in the USA with organizing as the road to union transformation?

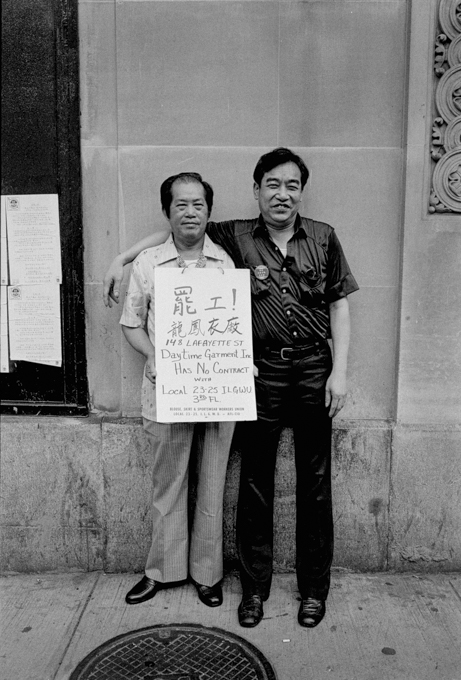

(JH) My own experience in the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU) demonstrates this thesis as well, within limits: How did the ILGWU give up, or at least moderate, its protectionist “Buy American” and “Stop Imports” campaign in the 1980s and 1990s? By organizing the tens of thousands of immigrant garment workers from the Caribbean, Central America, Mexico, and Asia. Then, as the US apparel manufacturing industry passed into history, and the union’s major employers became the apparel distribution centers handling imported goods for brands and retailers, the union, now called Workers United, adopted an activist internationalism to support garment workers in other countries as part of their campaign to organize the distribution centers of firms like H&M, VF Corp., and Gap.

Again, at the Writers Guild of America West, the effort to organize reality television resulted in the election of a militant reform leadership slate, the firing of the business-oriented executive director, a former CBS executive, and his replacement by David Young, a labor radical and “blue-collar” union organizer. The subsequent WGAW campaign to organize “America’s Next Top Model” through a recognition strike, while ultimately unsuccessful, led to a strengthening of the militant leadership and was part of the build-up to the 100-day Writers’ Strike in 2007 that won jurisdiction for the union over writing for the Internet, now the principal source of employment for writers.

(PO) With your emphasis on organizing the unorganized do you mean to say that reform movements are inconsequential?

(JH) This is not to say that reform movements should be abandoned, and all efforts put into organizing the unorganized. Both aspects of struggle are essential, and reinforce each other, and sometimes one becomes the leading aspect, as in the CIO drives of the 1930s, and sometimes the other, as in the Ron Carey campaign of the 1990s that led to the militant UPS strike of 1997. Right now there is a lot of volatility in the US labor movement, with unions like the Bakery Confectionery Tobacco and Grain Millers, International Association of Machinists and United Auto Workers forced by circumstances to confront their declining bargaining power and take militant action as the employers invest billions in Mexico and close plants in the USA. This volatility can be seen in the Teamsters and United Food and Commercial Workers, now confronting Amazon in the logistics and transport sector. The victory of the O’Brien-Zuckerman Teamsters United slate in the recent election reflects this volatility and is an important step toward a more militant and member-driven approach in the Teamsters union, which will have a big impact on the upcoming UPS negotiations and in organizing in Amazon and FedEx.

(PO) One of the Teamster United slate Vice Presidents, John Palmer, was recently quoted in an article in Labor Notes:

“The organizing department needs restructuring too,” said Palmer, who worked there for years. “We waste a tremendous amount of money flying organizers around the country,” he said. “That time and resources could allow us to train people out of locals to do this. We need to have that skill on the ground everywhere; we don’t need a lot of specialists airdropped from D.C. who disappear the minute a campaign is over.” What do you thin k of that statement based on your years of experience successfully organizing in many sectors?

(JH) Of course, it is good to have organizing assets on the ground everywhere, and there should be training for members out of locals; but to take on global corporations and to run national campaigns, you need a centralized campaign headquarters and “specialists” like Andy Banks and directors like Bob Muehlenkamp and John August (who ran the 1997 IBT UPS strike). You also need experienced organizers that can be sent to key locations to mount surprise attacks where they are least expected, as when the Teamsters were able to strike UPS at Paris and other European locations during that 1997 strike.

I am totally in favor of member-participatory strategies; the 2007-8 Writers Strike was totally run by the WGA members, who made all the important decisions through their executive board, composed of working writers, and through strike authorization. But they also had a strong executive director in David Young, an excellent research department, a professional communications department, and a committed staff to meet with small groups of writers, train strike captains, organize events, make sure picket signs got to the right place at the right times, and come up with effective tactics like picketing film and TV locations and shutting down the Golden Globes. It is the combination of intense member involvement and competent and experienced staff that gets the job done and done right; and with a national and international adversary, it is the combination of power on the ground in every locality where we can confront them and a strong centralized strategic direction that will win the day.

(PO) What do you make of the current strike wave, the present political landscape and what organizers should be focused on?

(JH) The current strike wave in food processing, manufacturing, health care, etc., and increasing tempo of organizing in certain sectors – digital media, higher education, and logistics – is a result of forty years of an employer offensive that depressed wages, closed union factories, busted unions and created the greatest economic and social inequality in the history of the world, with two families holding as much wealth as half the population, and with organized labor at its lowest percentage of the working population since the 1920s. The employers’ callous disregard for the lives of workers in the Covid-19 pandemic, notably in the food-processing industry and in healthcare – exposed the brutal nature of capitalist exploitation as never before; and the economic dislocation further exacerbated the declining standard of living of most working people. Pushed to the limit, large segments of the US working class rebelled against the political elites, in some cases in self-destructive political directions, in other cases by electing socialists and progressives; and in the workplaces we see a rebellion against the employer offensive, and in some cases against union leadership that hasn’t gotten the message that their members have decided it’s time to fight back with all we’ve got.

In the context of rising pressures and tensions in the economic sphere, caused by the decades-long employer offensive and the continuing decline of US capitalism, white supremacist, anti-immigrant, misogynist, anti-LGBTQ and authoritarian political ideologists, funded and supported by the corporate wing of the ruling class, have captured the Republican Party and provided an outlet for the fears and resentments of some segments of the working class and for the owners of small and medium-sized businesses. Other segments of the multi-racial, multi-national US working class have responded to the crisis of capitalism, exacerbated by the pandemic, with a fight-back against racial injustice, gender oppression, xenophobia, and anti-LGBTQ prejudice, and have supported progressive and democratic socialist candidates in local, state-wide, and national elections. I believe it is fair to say that many working people are disgusted with the current political landscape, their declining standard of living, the failure to deal effectively with the Covid-19 pandemic or the climate crisis, and the inability to chart a course forward to restore prosperity and a positive outlook for the future. Perhaps the best, and maybe the only way to turn this disgust into positive action is for the labor movement to aggressively organize at the grass-roots level and take on the corporate overlords in the workplaces and at the ballot box.

My view is that the primary, leading aspect for change in the US labor movement should be recovering the lost bargaining power through organizing the unorganized, including through cross-border campaigns in the supply chains of unionized and non-union firms alike, and through militant strike strategies that use our bargaining power to gain some control over investment decisions and to eliminate the two-tier and other contract terms that weaken our unity and our power. Those struggles can inspire the rank and file to the confidence and self-assurance that will lead to a greater role in the governance of the unions that are the basic instrument of the working class.

(PO) Thanks Jeff. Look forward to tracking your battles in Mexico!

…

Peter Haberfeld (1941-2021)

By Steve Bingham

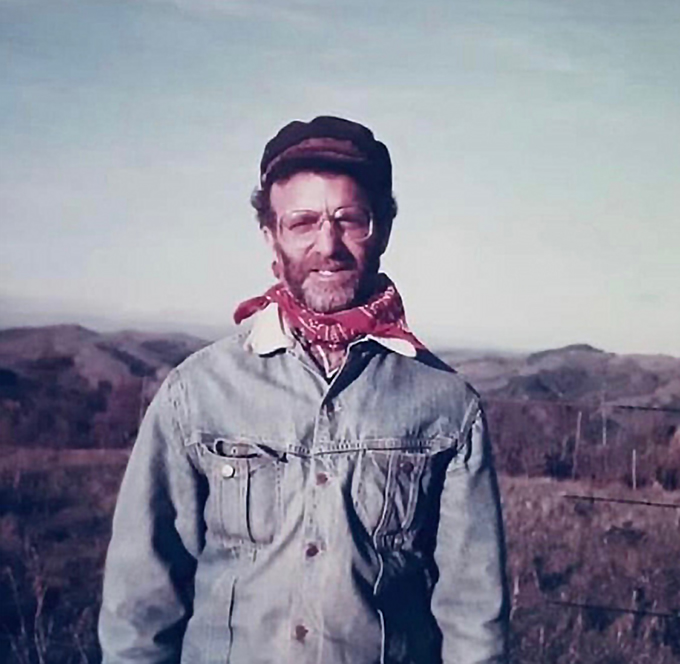

Peter Haberfeld, a lawyer for the people and community organizer, died of a heart attack at his home in Oakland on December 1, 2021. He was 80 years old. After earning a law degree at the University of California, Berkeley, Peter embarked on a life of activism as a lawyer and labor and political organizer.

As a law student in 1966, Peter worked in Albany GA for C.B. King, the pioneering civil rights attorney and only Black lawyer in Southwest Georgia. King deeply influenced Peter, firming up his determination to use the tool of the law to defend those who are marginalized, abandoned and powerless.

Between 1968 and 1975 Peter was an attorney and organizer in the California Central Valley, providing legal aid to Latino youth and farmworkers. In 1975, he joined the United Farm Workers legal staff, part of the legendary battle for farm worker union recognition. He was influenced by iconic leaders Cesar Chavez, Dolores Huerta and his mentor, renowned union organizer Fred Ross, Sr. Peter helped win the landmark, Murgia v. Municipal Court, which successfully limited racially discriminatory prosecution of defendant UFW members.

Peter was the first staff person hired to run the new office of the San Francisco Bay Area Chapter of the National Lawyers Guild. He worked at the Youth Law Center, California Rural Legal Assistance and the Bar Sinister legal collective in Los Angeles. His audacious combination of lawyering and organizing incurred the wrath of the conservative legal and political establishment everywhere he went. When Governor Ronald Reagan tried to defund CRLA, he specifically cited Peter’s legal work, including his involvement with the Black Panther Party in Marysville.

Peter later organized and advocated for back-to-the-land folks in Shasta County. He was a lawyer for the California Department of Industrial Relations, the state Occupational Safety and Health Agency, and the Public Employment Relations Board. He later became a union organizer for teachers in Fremont, Oakland (Oakland Education Association) and Vallejo. He then worked for the Oakland Community Organization, organizing teachers and parents for school reform in Oakland. Peter fought his final court battles at the law firm of Siegel & Yee including an epic case that ensured the survival of the National Union of Healthcare Workers.

Peter was proud of his record of four arrests:

– During the 1964 Berkeley Free Speech Movement

– While serving as a poll watcher during the election campaign of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party to elect candidates to the state’s legislature in 1967

– At People’s Park in 1969

– And with his wife Victoria Griffith in San Francisco protesting the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq

Throughout his life, Peter was always ‘presente’ to ‘fight the good fight’ against abuses of power – in occupational safety, school reform, civil rights and more. Peter worked well into retirement, volunteering on Barak Obama’s and Bernie Sanders’ presidential campaigns as well as helping friends and family with legal needs.

Peter, whose Swiss and Austrian parents escaped the rise of Nazism, was born in Portland, OR on October 23, 1941 eight minutes before his identical twin and grew up on his family’s farms in Oregon and rural Los Angeles. He attended Reed College and the University of California Berkeley School of Law. He was admitted to the California Bar in 1968.

Peter was a lifelong learner — deeply engaged with the world and people around him. In recent years, he and his wife Tory traveled and lived in South America. He wrote until the very end of his life on political issues in Cuba, Venezuela, Ecuador, Bolivia, Argentina, Peru and most recently France where he and Tory spent a very special time together in Montpellier and on a small farm.

Peter, whose early years were spent on his family’s farm, returned to farming in France – harvesting olives, caring for sheep and horses and milking cows while “Wwoofing” (World Wide Opportunities on Organic Farms). Peter and Tory lived off and on in France for the last four years of his life. He spent time with his two daughters and granddaughters there, which delighted him.

Peter summed up why he wrote this past year a detailed unpublished memoir of his lifelong engagement in ‘good trouble.’ With modesty, he wrote: “If [it] …appears as though I consider myself a hero or a major player in any way, I do not. I have described my experiences merely to convey what was happening during the period and how I participated.”

Peter is survived by his wife, Victoria (Tory) Griffith with whom he shared a passion for political organizing, his daughters Demetria (Demi) Rhine of Oakland and Selena Haberfeld Rhine of New York; two granddaughters, Marina and Alexa Escobar; the mother of his daughters, Barbara Rhine of Oakland; his ex-wife Dorothy Bender of Palo Alto; his brother Steven (Rena), living in Israel; his sister Mimi Haberfeld, living in Mexico; many nieces and his mother-in-law Marilyn Griffith of Redwood City.

Peter was dearly loved and will be terribly missed by legions of people who admired his gutsy and creative lawyering and organizing as well as the many who considered him central to their lives, for both personal and political reasons. A memorial will be planned for the spring. Donations may be made to The East Oakland Collective, an organization that Peter supported which addresses the needs of unhoused people in East Oakland.

Peter beautifully summed up what motivated him to be the always-engaged political person that he was in this letter he wrote to the son of one of his oldest friends. It’s well worth the read, especially for young advocates wondering whether anything they do in life will make a difference in people’s lives.

Dear Dylan:

What I say here is not to try to convince you that you and your dad are wrong to articulate doomsday visions of our future. I do not know how things will turn out and I will be long gone as all the evidence comes in. Simply, I will tell you what motivates me.

Something in my background has caused me to be an activist. Perhaps it is because my parents taught us that if an injustice exists, big or small, do something about it.

My involvement has always made me optimistic. I stood alongside many of my generation who fought for civil liberties, civil rights, and an end to injustices. I met people who were courageous, who dared speak and fight for a better future. I felt our collective power and saw that positive change can come about without a majority being mobilized. It was sufficient that well-intentioned, hard-working activists took a stand.

The Civil Rights Movement sacrifices led to improvements, growing consciousness, and access by young people to the college education that prepared them to become important scholars, writers, commentators. It is they who are developing a new and improved narrative for the present Movement and that which will come.

The Farm Workers Movement awakened the Chicano Youth. It put in motion the Latino leadership that has taken over in California to make it a Democrat-run State. Our State, as deficient as it is, is still a beacon to the residents of Mississippi and other slave states as well as the fly-over states.

The Women’s Movement has transformed the consciousness about women’s equality. It has led young women to become doctors, lawyers, leaders in all spheres, who have begun to influence how people perceive their living conditions. It still has a way to go to bring about wage equality and an end to physical and sexual abuse. But you cannot deny the progress that came about because people fought for something better.

You can say the same about the LBGT Movement and same sex marriage. The quote from Frederick Douglass about “not getting anything unless you fight for it” is still relevant. The totalitarian control and exploitation of millions of slaves would be with us today if it had not been for the minority of the population who fought it and moved the country to a new, although still unacceptable, stage.

The anti-War movement trained activists to understand the dangers of a fascist takeover of the US, now in police departments. Hopefully, soon they will oppose US Imperialism. We helped stop the imperialist expansion in Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, and other places our misleaders would have taken young US soldiers had it not been for the “Vietnam Syndrome”, had it not been for the people my twin brother now refers to as the “peaceniks” who thwarted the glorious war mongers.

My association with activists has made me an optimist. I have learned to combat my cynicism and pessimism by going to work with people who share my perspective. Recently, for example, as I sat in a meeting of 25 people on a Sunday morning talking about what brought us to go into the precincts to talk with voters about Bernie, I was excited to be connected to intelligent, well-informed, life affirming people who dared to win and risked to lose.

People like us who have grown up in bourgeois settings, satisfying our desires with material goods, embrace a mentality that is less prevalent farther down the economic ladder. We expect that all we have to do is make up our minds and become the person we imagine. We believe that there will always be progress. Our view is very short term. We have come to expect immediate solutions. We have a rough time adjusting to negative events. We have to, instead, see that history plays out over a long period, and that what is important in our lives is to be pushing for change to happen as quickly as possible.

Handwringing gets us nowhere. In fact, it is too often a pastime people use to excuse their lack of courage to fight for something better. It is appealing to reach a negative conclusion. If it is all bad, has always been bad, and will always be bad, only stupid (or unrealistic) people get involved in the struggle for something better. And they miss the exhilarating experiences of joining others who have the courage to face the negative forces by marching, petitioning, talking with others, and organizing collective power among the people to confront the wealth and military power of the fascists.

I have organized teachers strikes among other actions. This takes a long time. People must develop a consciousness about what is bad and what could be better. Then, they must conclude that there is no other acceptable choice but that of fighting for what is right, risking losing, losing pay, being scared, offending people who decide to break the strike. The job of the organizer is to lead people through a set of experiences that develops that consciousness.

It teaches us to view current political events through the lens of an organizer. We have to look at what is going on in the US as a consciousness-building experience. We challenge the police for what they do to unarmed young men and women of color. They respond by revealing their violence-prone nature. A shift is occurring, and the participants see that it is a product of their effort. They want more victories. Their demands become more far-reaching. Their analysis of the problem becomes more profound. Others, initially bystanders, join the effort. There is a payoff from viewing the glass as half filled, not half empty: we see what works, where we have to go from here, and we enjoy being hopeful, even if the next turn in the road is negative.

The only alternative is the unacceptable one of going passively to the slaughterhouse. That does not appeal to me as a fulfilling way to live.

(Have you read “the People’s History of the US” by Howard Zinn and “People’s History of France” by Gerard Noiriel? I think that they make the point much better than I can ever hope to do.)

You have talent and skills to help tell the story that combats the narrative of the forces in power. I look forward to a film that makes that kind of mark and to Jean’s advertising campaign that raises people to a higher level of consciousness and greater readiness to take on the people’s enemies.

Love to you dear comrades

Peter

…

The River, The Workers and The Wall: Las Cruces, NM and El Paso, TX

By David Bacon

The Rio Bravo is the border between Mexico and the U.S. from El Paso and Juarez to Brownsville and Matamoros. Just upriver from El Paso it passes through New Mexico, or it would if there were water in it. Today, though, the mighty river is dry.

There are eight major dams on the Rio Bravo. The big one at Elephant Butte, near Truth or Consequences, controls the flow down through Las Cruces and El Paso. Welcoming the release of the water from Elephant Butte used to be an occasion, when people would come to greet the river as it came alive, submerging dry sand and brush under the new flow.

That flow, fed by the runoff from rains and snow in the Rockies, would begin in February and finally run dry in October. But climate change alters everything. In 2020 water began to course down the riverbed in March and petered out in September. This past year the river only flowed from June through July – two months instead of nine.

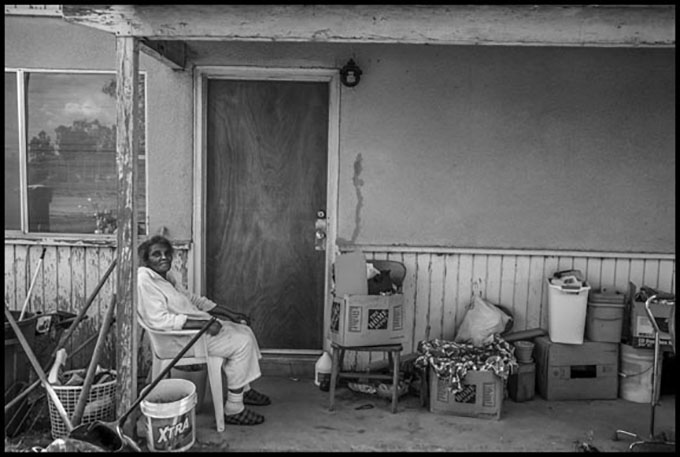

The dry river is the watercourse along Route 28, the old two-lane road that follows it through the Mesilla Valley from Las Cruces south to El Paso, marking the border between New Mexico and Texas. It is pecan country, where rundown buildings line the highway as it runs through old farmworker towns.

Its people may be poor, but pecans are New Mexico’s most profitable crop, worth over $220 million each year. Today Doña Ana County harvests more of the nuts than any other in the country.

From late December through early January alligator-like machines snake through the orchards, grabbing each tree between rubber-coated jaws, shaking the pecans off the branches. Another machine follows behind, sweeping the nuts into long rows.

Then the workers arrive. They clean out branches and debris that would otherwise choke the final set of machines in the groves – the giant vacuum cleaners that suck up the nuts, spit out the leaves, and haul the crop down to the sheds.

Pecan workers were some of the Southwest’s first labor activists. Emma Tenayuca, a young Communist organizer trained at the Universidad Obrera in Mexico City, led twelve thousand young Mexican and Chicana women out on strike in San Antonio in 1938.

This generation of pecan workers, however, may be the last. The trees yield big profits for growers, but they need water, and the river is drying up. The aquifer below the valley depends on river flow, so pumping water is a solution that will only work for a while longer.

According to Kevin Bixby, director of the Southwest Environmental Center, “it’s only a matter of time until people understand that growing pecans in the desert is not sustainable. Water is a resource of public trust, which means that the government has the duty as an administrator to manage this resource for the benefit of all, including future generations.”

Below the Mesilla Valley, just before the riverbed becomes the border between Mexico and the U.S., the new barrier wall stretches through chamisa and sagebrush, across the desert west of El Paso.

In El Paso itself, the city of Juarez is visible through an older section of the wall and its network of wire mesh. Elevated roadways hug the borderline, while underneath it lies an abandoned landscape of empty lots and abandoned buildings from an earlier era.

People arriving from the south produced the pecan industry and its profits. But the wall remains a potent symbol of the hostility of Texas and U.S. authorities towards migrants, wanting their labor but denying their human dignity.

…

“REQUIEM FOR THE WARRIORS”

By Ernest DiStefano

In 2015, after thirty years of experience as a criminal justice professional, of which I spent seventeen years working in a prison, I founded the Comeback Athletes & Artists Network, (CAAN, Inc.), a non-profit organization with the mission of using athletics and the arts to assist at-risk and impoverished communities. My previous work with combat athletes as a co-manager and mental training coach convinced me that these athletes are the most vulnerable and at-risk athletes in the sports world. In this essay, I will use the cause and effect process and medical research to defend this belief. I will also discuss the solutions put forth by others, and our organization’s own solution, for helping to eradicate the oppressive plight of professional combat athletes.

.

PART I: CAUSE & EFFECT

Cause: Poverty

Writer Walter Mosley said, “Poor men box, because it’s the only choice they have. A poor man, of any color, is fighting for his life in the ring. And the only reason they’re fighting for their lives in the ring, is because it’s a little bit safer than fighting for your life on the streets of America.”

Effect: A willingness to risk one’s own life to alleviate those circumstances

In the specific case of boxers and other combat athletes, the risk involved is potential brain injury and/or death from the violent nature of their chosen professions.

Effect: Combat Sports-Related Deaths

In the past 131 years, 1,878 boxers have died as a direct result of injuries sustained in the ring. This is an average of more than fourteen deaths per year and more than one death each month. Prior to that, from 1740 to 1889, when boxers fought bare-knuckled (a sport which is currently growing in popularity), there were 266 documented deaths (“Death in the Boxing,” by Rupert Taylor, April 29, 2021). Since MMA’s inception in the mid-1990’s there have been sixteen reported deaths among MMA fighters directly related to injuries sustained in the Octagon (“How Many Fighters Have Died in the Ring: Boxing and MMA,” by Ross Canning).

A 2014 study by Eastern Michigan University, which examined professional wrestlers who were under the age of sixty-five and active between 1985 and 2011, found that the mortality rates for professional wrestlers were up to 2.9 times higher than the mortality rate for men in the wider United States Population. A separate report in 2014 by John Moriarty of the University of Manchester and Benjamin Morris of FiveThirtyEight found that the mortality rate for professional wrestlers is higher than that of athletes in other sports. It is suggested among experts that a combination of the physical nature of the professional wrestling industry, no off-season, and the drug culture of the 1970’s and 1980’s contributes to the aforementioned high mortality rates for professional wrestlers. The former two factors of the physical nature of their sports and no off-season also applies to other combat sports. Another study credits the higher death rate among professional wrestlers to cardiovascular disease.

Effect: Head and Brian Injuries

A 2015 research study, “Epidemiology of Injuries in Full-Contact Combat,” written by Reider P. Lystad of Central Queensland University, Sydney Australia, found that the proportion of neck and head injuries for the sport of boxing was 84%; 74% for karate; and 64% for MMA. This research also showed that Karate had a concussion rate of 19%, Boxing had a concussion rate of 14%, and MMA had a concussion rate of 4%. It also showed that MMA had the vast majority of life-threatening, or life-changing injuries, coming as a result of head trauma, while also revealing that that professional boxers were: 1) more likely to experience loss of consciousness, 2) more likely to suffer eye injuries (detached retina), and twice as likely to sustain a concussion that involved a loss of consciousness. Further this research showed that medical suspensions for boxers were a minimum of twenty-six days, compared to medical suspensions for MMA fighters, which are for an average of twenty days.

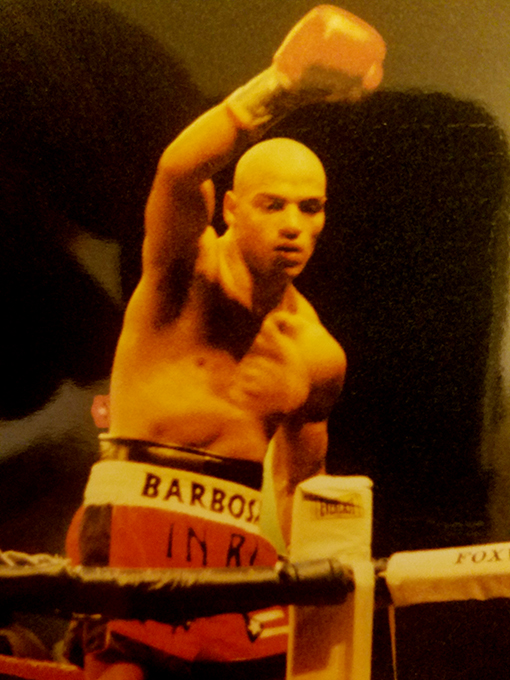

“because it’s all I know.” Brian “The Bull’ Barbosa

The life of former professional boxing champion, Brian “The Bull’ Barbosa, is an illustration of this cause and effect dynamic. Through my personal involvement in assisting Brian, I have come to learn his life story. Brian endured poverty and abuse as a child, which drove him to the boxing gym, which in turn resulted in a professional fight career. Although Brian was rewarded for his efforts in the ring with a world championship, he also sustained serious brain trauma and injury along the way. This, combined with his life experiences, affected his decision-making abilities and left him vulnerable to the less than honorable elements in the fight game. When I first spoke with Brian, he expressed a desire to resume his fight career. When I asked him why, Brian said, “because it’s all I know.”

On September 21, 2021, Brian courageously shared his story on the Dr. Phil Show. Brian continues to battle the inner demons created by his physical and personal trauma, and is currently receiving treatment to exorcise those demons.

PART II: SOLUTIONS

There have been several possible solutions put forth to address the aforementioned issues. Those I have heard expressed most often are these:

- Outlaw Combat Sports. The frequency of brain injuries and death in the sport of boxing has motivated some to call for making it illegal. I firmly believe, however, that if combat sports are outlawed, it will drive those sports “underground” and make it even more dangerous for combat athletes. Instead of outlawing boxing, we should work harder to remove illegal and unethical behavior from the combat sport industry.

- Do Nothing. There are many who, in fact, believe that the sport of boxing should remain unchanged, that the brutality and violence of the sport is what makes it appealing to the public. They also cite the concussion issues in other sports like football and soccer. Those points are undeniable; however, we must also remember that professional football is structured under one central governing authority, The National Football League (NFL). Soccer is governed internationally by the Federation Internationale de Football Association (FIFA), which is comprised of 211 national associations worldwide. The central governance paradigm allowed American football and soccer, and other sports with the same structure, to address the issue of concussions and head injuries and eventually establish one unified set of concussion and head injury protocols.

Our Solution

Based on my work with Brian Barbosa and other combat athletes, we believe that the solution to the current predicament faced by professional combat athletes should include their access to information, services and assistance that enable them to make independent career decisions driven not by desperate life circumstances, but in the best interests of themselves and their families. In other words, we believe combat athletes should not fight to survive, but fight to thrive. Our organization provides access to assistance, and is currently developing additional avenues of access, that promote the aforementioned objective, such as:

- Banking, Financial Investment, and Financial Planning Assistance:

Such assistance can provide combat athletes with a pathway for ensuring financial stability and security for themselves and their families, as well as a happy and secure retirement. I recently established a partnership with the Del-One Credit Union and our organization to provide combat athletes with access to savings and checking accounts, financial management assistance, financial investment assistance and opportunities (including retirement accounts), and insurance. We hope to be able to expand these services upon acquiring sufficient funding to do so.

- Independent Contractual Review/Consultation:

Combat athletes should have access to affordable legal assistance on issues relevant to the fight game and their professional fight careers; specifically, promoter contract review and consultation. Combat Athletes should also educate on the Muhammad Ali Act, a federal law that was passed in 2000 to provide boxers with legal protections against unlawful practices within the boxing industry (at the time of this writing, the Ali Act pertained to the sport boxing and bouts of ten rounds or longer). Our organization has reached out to licensed attorneys to request their pro bono assistance to combat athletes, when requested by the fighter(s), with contract review and consultation assistance. I ask any licensed attorneys to contact us who are reading this essay and are interested in offering such services to combat athletes.

NOTE: CAAN, Inc. does not provide legal services of any kind, as we are not a licensed law firm, but merely provide referrals to combat athletes for outside legal consultation and assistance, upon the combat athlete’s request. Any additional professional arrangements made between the combat athletes and the attorneys are strictly between said combat athletes and attorneys. CAAN, Inc. serves no role in said arrangements whatsoever.

- Educational/Vocational Training: Combat athletes should have access to educational programming and vocational training that will give them the opportunity to establish additional revenue streams for themselves and their families. This will, in turn, provide combat athletes with leverage to make better decisions with respect to their professional fight careers.

- Clinical Treatment: Combat athletes should have access to affordable treatment interventions to address any physical, neurological, psychological, emotional, or substance abuse issues.I recently brokered a partnership between GoodRx and our organization to provide prescription discount cards to professional combat athletes. We hope to expand the available GoodRx discount services offered to combat athletes upon acquiring sufficient funding to do so.

Our organization is so committed to our mission that we offer our time and efforts as volunteers, receiving no financial compensation of any kind. We have established a CAAN, Inc. Facebook Group through which we are gaining momentum and support for our cause. One such supporter is well-known and well-respected boxing promoter, Roy Foreman, who is also the brother of former world heavyweight champion George Foreman. Mr. Former agreed to partner with our organization and allow his fighters access to our services. I call on professional combat athletes, and other professionals of the fight game, to join our cause and help us move it forward. You can go on Facebook and send a request to join our CAAN, Inc. Group. You can also email us at happyathlete24@gmail.com or visit our website at www.caangroup.org. We are happy to answer any questions. Thank you.

…

Olney Odyssey # 19 California, Christina and Beyond

By Peter Olney

While I had traveled to England and Italy in my early twenties, I was basically a Massachusetts guy. Worcester – 60 miles from Boston- was the West for me. An occasional trip south to New York City or north to Maine and New Hampshire were the limits of my domestic adventures. California was Hollywood and the telecast of the Rose Bowl on New Year’s Day. Imagine going to a football game on January 1 wearing shorts and a T-shirt and basking in the sun while denizens of the Northeast froze.

My dear friend and Boston City Hospital co-worker, Steve Eurenius, had visited California and had New Hampshire friends in Lake Tahoe so he was down for a road trip to the West Coast. Neither of us had cars that would make the trek so we decided to do a “drive away”. My old buddy from the Lewd Moose Commune Buck Bagot had relocated to California a few years back and was living in San Francisco so that was determined to be our final destination.

A “drive away” car was not a new concept. My father had driven some wealthy businessman’s wife and daughter across country from New York to California when he got back from WW II. My Dad had memories of visiting the Biltmore Hotel in Los Angeles and going up the coast to Santa Maria and visiting the Norwegian parents of his brother-in-law, Winston Johnson. He then drove Winston’s car Back East.

“We were hungry but not takers!”

Steve and I found an Italian American retiree from Framingham, Massachusetts who was relocating to the “warmer” climes of Scottsdale Arizona, at the time the Spring Training home of the Boston Red Sox and the city where the BoSox slugger Ted Williams’ brain has been cryogenically frozen and preserved. We drove out to Framingham and encountered Angelo Fosco sitting on his shaded porch surrounded by grapevines and wearing a classic sleeveless T-shirt, known in some circles as a Guinea T. Angelo seemed very happy in Framingham, but his children had encouraged him to retire to Arizona to avoid the New England winters. We found Angelo through a service that paired up soon to be Sun Belt retirees with drivers desiring to get somewhere without the expense of air or bus or the wear and tear on your own car.

The “Captain” and I packed our bags into Angelo’s car and headed off to Maricopa County, Arizona to deliver the car in Scottsdale where he would be flying to shortly. We left Boston in mid-August and the trip across country was pretty uneventful. There was a stop in Nashville to visit some friends and hear my cousin David Olney play music. Before arriving in Arizona we stopped in Amarillo Texas and had a meal at the Big Texan restaurant. This is the home of the Famous 72 oz. steak. The way this works is you just tell your wait staff person that you want to take the 72 oz. steak challenge. They escort you to a table on a small stage at the front of the humongous main dining room. Beside you on the table is a large digital count down clock. If you consume the 72 oz. steak and all the trimmings that go with it in 60 minutes (one hour) the steak is free. If you fail, you pay $70.00. We were hungry but not takers!

We arrived in Scottsdale in the scorching summer 100 plus degree heat of the Arizona desert. This was travel before GPS so we needed help finding Angelo’s new residence. There was no one on the street to ask directions so we found a fire station and rang the call button, and a fireman came out to point us on the way. We were not in Boston any more! I’ll never forget finding Angelo sitting in his air conditioned living room looking miserable –confined to the indoors and without his community of friends in Framingham. He was physically altered and ruing the move to Arizona. It probably hastened his passing.

While I have since come to appreciate Arizona and particularly Maricopa County and the greater Phoenix area – I spent two weeks there helping to get out the vote for Biden/Harris in 2020, we were not interested in spending any more time in the air conditioned desert. Even liquor stores or “packies” as we called them in Massachusetts had drive thru windows so that customers did not have to get out of their cars and face the extreme heat. We got on a Greyhound bus bound for San Diego and California. Most of our trip was on Interstate 8, which in the California section hugs the Mexican border. At one point the bus was stopped by the Immigration and Naturalization Service border patrol, and we were boarded by their agents asking everyone on the bus for their papers.

“… it was a Friday evening September 3rd encounter that would be life changing”

Greyhound left us at their downtown San Diego terminal on National Boulevard. At that time downtown San Diego was a gritty entertainment center for the Marines and Navy. We stayed at a fleabag motel and the next morning we got ourselves a car from “Rent a Wreck” and started our drive north to San Francisco. We traveled north on Interstate 5 and just south of downtown Los Angeles we encountered a stretch of highway enclosed by high concrete walls and a citadel like building in the style of an Assyrian palace. This was an empty factory building that had been closed by Uniroyal in 1978. This stretch of concrete was very intimidating and suggested to me that Los Angeles was not worth stopping to see so we kept on trucking until we got over the Grapevine into the San Joaquin valley. We steamed northward on the 5 freeway and then crossed over westward on Lost Hills Road to Paso Robles where we encountered a huge gathering of cowboys on horseback participating in the San Luis Obispo County fair. Then it was further west to Pacific Coast Highway (Highway 1) which took us up to Big Sur traveling north and finally arriving in the picturesque resort town of Carmel where in 1986 actor Clint Eastwood was elected mayor on a no growth platform, serving one term. The Italian Communist party in Rome celebrated Eastwood’s no growth stand when they did battle against the siting of a McDonald’s fast food restaurant. Strange bedfellows!

From Carmel it is a short 121 mile hop – in California terms – to San Francisco our ultimate destination. I was at the wheel when we crossed the Bay Bridge from Oakland to The City. I can still remember being dead tired but transfixed by the iconic view of the San Francisco skyline as we crossed the span from Yerba Buena Island to the Embarcadero. We had arrived, and I found my friend Buck Bagot and his house on 400 Gates Street in the Bernal Heights neighborhood on Wednesday, September 1, 1982. Buck caught me up on his community organizing exploits and led me around the neighborhood introducing me to some of his close friends and allies. We visited Jean Hamer at San Francisco General Hospital. She was on oxygen and suffering from emphysema, but still outspoken and a dynamic community force. She was Native American and married to a 300 lb. Tongan. She was the first Board President of the Bernal Heights Community Foundation, which Buck helped to found. We also connected with Sharon Johnson on Clayton Street. Sharon was a long time aide to the legendary State Senator John Burton, and was a single Mom raising three challenging teen-agers. All of these encounters were interesting and stimulating, but it was a Friday evening September 3rdencounter that would be life changing.

That afternoon Buck and I went out jogging in the neighborhood and were relaxing in our shorts in the basement apartment in advance of his departure for Cleveland on the red eye that evening. There was a knock on the door and Buck yelled, “Come in Christina!” In walked the most stunning looking woman I had ever seen. She had jet back hair, brown skin and high cheekbones and indigenous features. I wasn’t in Boston any more! Buck later told us that the “mutual attraction was scaldingly obvious.” The moment calls to mind the wonderful Sinatra tune, “Strangers in the Night”. While many can critique “Ole Blue Eyes” for his rightward political drift in old age, it is important to remember his early stands on civil rights and the fact that he almost alone among the Italian American crooners kept his original Italian name at a time when the assimilation bias changed the names of such notables as Tony Bennett and Bobby Darin. This about sums up our meeting on September 3, 1982 one night before I was scheduled to return to Boston and my job at Boston City Hospital:

“Strangers in the night exchanging glances

Wond’ring in the night what were the chances

We’d be sharing love before the night was through

Something in your eyes was so inviting

Something in your smile was so exciting

Something in my heart told me I must have you

and

Ever since that night we’ve been together

Lovers at first sight, in love forever

It turned out so right for strangers in the night”

That chance encounter, Christina Perez just happened to be visiting Buck on the same weekend, completely changed the course of my life. Do opposites attract? Can a New England Yankee blue blood find love and happiness with a Southern California Mexican American with Chichimec indigenous blood? Stay tuned as a transcontinental romance blossoms in Olney Odyssey # 20.

…

An Injury to One is an Injury to All

By Jay Youngdahl

Editor’s Note from Peter Olney: In early December 2021 I was invited to do a training for the Industrial Division of the Central South Regional Council of Carpenters. The Council is headquartered in New Orleans and has over seven thousand working construction carpenters in Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Oklahoma and Texas. The Council also has an industrial division of over a thousand members at paper products manufacturers like Boise Cascade. This was the quarterly meeting of the Council and delegates were present from all five states and all industrial facilities. My friend Jay Youngdahl is the attorney for the Council. For the last post of the year, The Forum has elected to run a very inspiring portion of his remarks from his speech of December 11th, 2021 to the Council delegates. We think it speaks of where we come from, who we are and where we can go, of possibilities for the labor movement, and the country.

.

Jay Youngdahl

Now, when I speak with you at our meeting, I always like to just take a couple minutes and talk a little philosophically about our union movement. I’m passionate – to use an overused word now – about what we do in our union.

I got some of this at birth. I’ve got two middle names. My name is Jay Thomas Armstrong Youngdahl, and that’s kind of a long thing. The only time I ever used it all was when I was in the Army. Armstrong is after Louie Armstrong because my parents were jazz fans. But Thomas, you know there’re a lot of people named Thomas. But I’m named after this guy named Norman Thomas, who was a politician in the thirties and forties. In fact, he ran for President one time, though he did not get many votes. The reason my parents named me after him was that he came to Arkansas to try to help out the farm workers who worked on tractors and in the fields. He spoke to them in East Arkansas outside of Memphis, at a meeting of the Southern Tenant Farmworkers Union. When the sheriff and all the growers heard he was coming they told Thomas, “You can’t have this rally. We’re not allowing labor unions in Eastern Arkansas.” And Norman Thomas said, “Wait a minute. You know, this is the law,” we have rights. And they said, “Mr. Thomas, you don’t understand what we’re talking about.” So, the sheriff and all the people got him and rode him out of the county, even though that was an illegal thing to do under the law. Norman Thomas talked about this incident, which happened in our Council area, for years. My dad and mom were so impressed. They said, “One of the middle names for our first child is going to be named after Mr. Thomas.”

Today the main point I want to make is about what it means to be in a union. We live in a country today where we can’t even agree on what it means to be American. Of course, we all want America to be great but what’s it means to be great? You know, we have differences of opinion. We think about the history in all kinds of unusual ways, I think. So, how do we respond if we care about each other? How do we decide what’s great? How do we decide which of the stories told about our history we should believe?

You know, I was a teenager during the Vietnam war period, and grew up in Little Rock during the struggles for civil rights at Central High School there. How do I think about American greatness or this history when I grew up then? It’s tough and I’m not here to say that it is going to be easy to get to a better place in this country. But I believe that in the union movement we’ve got an answer and a place to start. Because what we do in unionism is we work for the group. We work by the slogan, “an injury to one is an injury to all.” You have heard me say before, I worked as a machinist some between high school and the time I was drafted. I was a terrible machinist, but I was trying, and the union helped me. I was going to get suspended for bad work, but the union representative went to the boss and said, “Well wait a minute. He didn’t grow up with machines that much in his life, but he is trying.” Of course, some of us have skills in one area and don’t have skills in other areas. The union works to protect all who are honestly trying.

And so, from unionism there’s a philosophy. A philosophy of community, even for those of us who aren’t good with machines. And we understand the larger community. We care about our community because you can make a big ol’ salary. You can have good benefits. But if the schools are terrible or if your community’s terrible, it’s terrible for your family. Because the idea of unionism is to think about everybody as a whole, we’re ready when there are threats to individuals and to the community. We’ve got an answer.

Let’s talk about another issue in our country. As we know, relationships among different ethnic groups and nationalities and colors do not seem very good today. But look around this room. What group do you participate in which is as diverse as the people in this room? I mean, maybe Wal-Mart stores in some places but – I have been thinking about this as I look around the room. Think about ages. We have older and younger, and I am the oldest. We have a significant number of women, especially for a union whose members are in construction and manufacturing. Let’s give a round of applause to our union sisters. And, we’ve got people from downtown Houston, one of the third biggest cities in the United States, and we’ve got people from some of the most rural parts of Mississippi, Louisiana, and Arkansas. We’ve got African American people; we’ve got Hispanic people. We’re starting to put more and more material into Spanish. We’ve got our Asian brother who’s here, and we’ve got white people like me.

And we’re all about the same thing and nobody is better than anybody else. We’re putting up that drywall. We’re standing side by side. We’re taking that big ol’ tree, whittling it down to a little tree by cutting it into boards. We’re all doing the same thing. And there just are very, very few places in the United States today where you have this kind of thing where people work together like this. And for me, that’s what America’s about.

That’s what – you know, we called it a melting pot at one point, and that’s what we’re about. But you’ve got to have an initial seed to make the tree grow, and our seed is “an injury to one is an injury to all.” We work together for the common good.

So, thank you very much, brothers and sisters. It’s an honor to work with you. It’s the most prideful thing I do. Talk with you all later.

…

ROOTED IN EXCLUSION, TOWNS FIGHT FOR THE RIGHT TO WATER

By David Bacon

.

SAN JOAQUIN VALLEY, CALIFORNIA — Alberto Sanchez came to the United States without papers in the 1950s. After working for two decades, he found a home in Lanare, a tiny unincorporated community in the San Joaquin Valley, where he has lived ever since. “All the people living here then were Black, except for one Mexican family,” he remembers.

Lanare is one of the many unincorporated communities in rural California that lack the most basic infrastructure. According to PolicyLink, a foundation promoting economic and social equity, there are thousands of unincorporated communities throughout the U.S., mostly Black and Latino, and frequently poor, excluded from city maps – and services.

PolicyLink’s 2013 study “California Unincorporated: Mapping Disadvantaged Communities in the San Joaquin Valley” found that 310,000 people live in these communities scattered across the valley.

They are home to some of the valley’s poorest residents in one of the richest, most productive agricultural areas in the world. Today, their history of being excluded from incorporated cities affects their survival around the most critical issue facing them: access to water.

Lanare: A History of Racial Exclusion

Lanare has its origin in land theft and racial exclusion, like many similar colonias. The land on which it sits was originally the home of the Tachi band of the Yokut people. It was taken from them and given by Mexican governor Pío Pico of California as a land grant to Manuel Castro, two years before California was seized from Mexico in 1848. Castro’s Rancho Laguna de Tache was then fought over by a succession of owners until an English speculator, L.A. Nares, established a town and gave it his own name. From 1912 to 1925 Lanare had a post office and a station on the Laton and Western Railway.

One such covenant, written in 1952, said, “This property is sold on condition it is not resold to or occupied by the following races: Armenian, Mexican, Japanese, Korean, Syrian, Negros, Filipinos or Chinese.”

Lanare drew its water from the Kings River. The larger town up the road even changed its name to Riverdale to advertise its proximity to the watercourse. But big farmers tapped the Kings in the Sierras to irrigate San Joaquin Valley’s vineyards and cotton fields. Instead of flowing past Lanare and Riverdale, in most years it became a dry riverbed. By the 1950s Tulare Lake, the river’s terminus, had disappeared.

With no river, people left. The families who stayed in Lanare, or moved there, were those who couldn’t live elsewhere. Paul Dictos, Fresno County assessor-recorder, has identified thousands of racially restrictive covenants he calls “the mechanism that enabled the people in authority to maintain residential segregation that effectively deprived people of color from achieving home ownership.” One such covenant, written in 1952, said, “This property is sold on condition it is not resold to or occupied by the following races: Armenian, Mexican, Japanese, Korean, Syrian, Negros, Filipinos or Chinese.”

Excluded from Fresno, 30 miles away, as well as from Hanford, 23 miles away, and even from Riverdale, a stone’s throw down the highway, Black families found homes in Lanare. For farm laborers, truck drivers and poor rural working families, living in Lanare was cheaper. By 2000 Lanare had 540 residents. A decade later, 589. Most people moved into trailers and today are farmworkers in the surrounding fields. A third live under the poverty line, with half the men making less than $22,000 per year, and half the women less than $16,000.

With no river, Lanare had to get its water from a well. And in the late 1990s residents discovered that chemicals, especially arsenic, were concentrated in the aquifer below this low-lying area of the San Joaquin Valley. They organized Community United in Lanare and got a $1.3 million federal grant for a plant to remove the arsenic. When the plant failed, the water district they’d formed went into receivership, leaving families paying over $50 a month for water they couldn’t use.

Community United in Lanare banded together with many of those unincorporated settlements suffering the same problem, and began to push the state to take responsibility for supplying water. California Rural Legal Assistance (CRLA) filed suit on their behalf, saying California’s Safe Drinking Water Act required the state to formulate a Safe Drinking Water Plan. Then former CRLA attorneys set up a new organization, the Leadership Counsel for Justice and Accountability, which filed more suits.

“We organized to make the state respond,” says community activist Isabel Solorio. “We got stories in the media and took delegations to Sacramento many times.” State Sen. Bill Monning, who gained firsthand knowledge of California’s rural poverty as a lawyer for the United Farm Workers, wrote a bill to provide funding for towns like Lanare. SB 200, the Safe and Affordable Funding for Equity and Resilience (SAFER) Act, finally passed in 2019, providing $1.4 billion over a decade to fund drinking water projects, consolidate unsustainable systems and subsidize water delivery in low-income communities.

Matheny Tract: Fighting for Water and Basic Services

For many unincorporated towns, however, funding for water service alone is not a complete solution. A history of exclusion has left them without other services, near the towns and cities that excluded them. One is the Matheny Tract, just outside Tulare city limits. Vance McKinney, a truck driver who grew up there, recalls that his parents, whom he called “black Okies,” couldn’t get a loan for a home when they came up from the South in 1955. They bought a lot from developer Edwin Matheny, who’d subdivided land just outside the city limits and sold lots to Black families.

Four decades ago, Tulare County’s General Plan even proposed tearing down the community. Matheny Tract, the plan said, had “little or no authentic future.” After the Matheny Tract Committee organized to pressure the state, in 2011 the city and county of Tulare agreed to connect city water lines with Matheny’s Pratt Mutual Water Company. The city then backpedaled, claiming it had no water during the drought. At the same time, however, it was providing water to its own, higher-income subdivisions and industrial developments.

Finally, the state Water Resources Control Board issued an order for the voluntary consolidation of Tulare and Matheny’s water systems. When the city still dragged its feet, the state issued a mandatory order, and the systems were connected in 2016.

But Matheny Tract also has no sewage system, and discharges from septic tanks sometimes even bubble up in the yards of families like McKinney’s. Tulare’s wastewater plant is a stone’s throw away, but Matheny residents can’t hook up to it. According to activist Javier Medina, “On some days it smells really bad here. I went to a city council meeting once, and one of their experts said it was probably because they were using the waste to irrigate the pistachio grove next to it.”

Medina says he invited Tulare Supervisor Pete Vander Poel to come to Matheny to experience it. “He said he’d only meet with us in the cafeteria in the Target store in Tulare, because Matheny was very dangerous,” he recalls. For Reinalda Palma, another committee member, the reason for Tulare’s reluctance is simple. “There’s a lot of discrimination against Mexicans,” she charges. “We have to mobilize if we want anything to change.” Finally, a threat to sue from the Leadership Counsel got the city to agree to begin planning a sewer consolidation as well.

Tooleville: “They Think We’re Nothing”

Even less cooperation has been forthcoming in Tooleville, less than a mile from the Tulare County city of Exeter. In 2001 residents of this unincorporated community began asking Exeter to extend its water lines to provide service. The city refused, thus beginning one of the longest fights for drinking water in the valley’s history.

Ironically, Tooleville’s two dirt streets end at the base of the Sierra foothills, where the Friant-Kern Canal carries millions of gallons of water from the Friant Dam on the San Joaquin River to fields at the valley’s south end. The canal was built with taxpayer funding by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation in the 1940s, as part of the Central Valley Project. It diverts so much water that the San Joaquin River disappears in areas below the Friant Dam during dry seasons. With no river water, farmers in the river basin pump water from the aquifer below, leading to land subsidence in many areas of the San Joaquin Valley. Even the canal itself has lost up to 60% of its delivery capacity because the land is sinking under it.

While Tooleville residents can watch the water flow by on the other side of a chain-link fence, they can’t touch it, much less drink it. The community gets its water from two wells. One has already gone dry. “We only have water in the morning,” says Maria Paz Olivera, secretary of the Tooleville Mutual Nonprofit Water Association. “When workers come home from the fields in the afternoon there’s no water, and they have to wait until late before they can shower.”

The state has discovered hexavalent chromium in the water as well, and people fear drinking and cooking with it. It currently supplies bottled water to residents.

Tooleville is surrounded by grape vineyards and citrus groves. “The growers beside us have sunk 400-foot wells, while our wells only go down 200 feet,” Paz Olivera says. “Growers run Exeter, and they’re all Trump people. When they look at us, all they see are poor Mexicans. They think we’re nothing.”

Roughly 80% of the water used by all California businesses and homes is taken by growers to irrigate 9 million acres of farmland.

Blanca Escobedo, a Leadership Counsel organizer working with the Tooleville community, agrees. “The Exeter City Council members are all white, while half of Exeter is Latino,” she says. “You see this in their comments. One councilmember said they wouldn’t connect with Tooleville because people there wouldn’t pay their bills. When the community invited the Exeter mayor and council to tour, they wouldn’t talk with residents. In one meeting the mayor said consolidation was a waste of money and he wished Santa Claus was real.” When Tooleville residents attended a meeting in 2019, Escobedo says councilmembers asked to be escorted to their cars by security.

After negotiating for a year and a half with Michael Claiborne, the Leadership Counsel attorney representing Tooleville, the Exeter City Council adopted a water master plan in 2019 with no consolidation. Mayor Mary Waterman-Philpot said, “We have to take care of Exeter first,” and was “not interested” in Tooleville.

Under previous laws the state water board could only request a voluntary consolidation in a case like Tooleville’s. But this year the legislature passed SB 403, authorizing mandated consolidation where a water system is at risk of failure. The water board has told Exeter that it is prepared to issue an order, and according to Leadership Counsel co-director Veronica Garibay, the city has agreed to begin planning a consolidation.

Canaries in the Coal Mines?

Perhaps these small communities, vulnerable due to their history of exclusion, are like canaries in the coal mines. Even the large cities of the San Joaquin Valley now have burgeoning problems finding water. Roughly 80% of the water used by all California businesses and homes is taken by growers to irrigate 9 million acres of farmland.

While state legislation has given unincorporated communities more power to negotiate for their tiny portion, the system is structured to serve the needs of agriculture. And as the land sinks in many areas, and wells go even deeper, the aquifer itself is in danger.

For African Americans who began many of the valley’s unincorporated settlements, state legislation comes late. Ten years ago, Vance McKinney showed me the place where sewage welled up in front of his house. Now he has moved his family into Tulare and just comes for visits to the place where he grew up.

In another colonia, Monterey Park Tract, the community finally won a water connection to the nearby city of Ceres (itself facing rising water contamination), but the Black families who settled here are mostly gone. Betty Yelder, still on the local water board, remembers that her father came from Biloxi, Miss., in the 1930s, “when we couldn’t live in most parts of Modesto. But I’m retired now, and the rest of our family doesn’t live here anymore.”

Mary Broad, one of the last Black residents of Lanare, died a few years ago.

In the middle of the Matheny Tract, a dry canal bisects the community. It’s empty except for a few windblown papers and dead tumbleweeds. Javier Medina says residents still pay $50 a year for the privilege of having it run through town. “We have better water now,” he admits, “but I wonder if the canal is also a warning of what’s in store.”

…

Supply Chain Pain

By Molly Martin

With poverty on the rise, a dearth of affordable housing, climbing infant mortality, and a pandemic crisis that our failing healthcare system struggles to confront, it’s starting to seem like the U.S. is sliding into the status of a “Third World”country. Now comes the specter of economic hardship as we face unprecedented shortages and price increases amid a perfect storm of events, including COVID-related labor issues, extreme weather and surging consumer demand.

At the center of this expanding debacle is the bottleneck at two major container ports in California. Some ships have been forced to wait up to a month to unload their goods, leaving everything from food and household products to toys, electronics, clothing, and cars sitting in limbo. The delays have been compounded by a trucker shortage, leading to an enormous and growing backlog of containers.

When I read about supply problems that are emptying store shelves all over the U.S., I confess that I hoped Americans might connect a few dots, might get a taste of the misery we have imposed on the country of Cuba for six decades.

Do Americans even know that our government prevents trade with Cuba, the most enduring trade embargo in modern history?

Do Americans know that this year 184 countries voted in favor of a resolution to demand the end of the US economic blockade on Cuba, for the 29th year in a row, with only the U.S. and Israel voting against?

Cuban Foreign Minister Bruno Rodríguez Parrilla, present during the vote in the UN General Assembly Hall, said that the blockade is a “massive, flagrant and unacceptable violation of the human rights of the Cuban people.”

He added that the embargo is about “an economic war of extraterritorial scope against a small country already affected in the recent period by the economic crisis derived from the pandemic.” Mr. Rodriguez estimated 2020 losses to be $9.1 million. He said that the sanctions have made it harder for his country to acquire the medical equipment needed to develop COVID-19 vaccines as well as equipment for food production.

I am horrified and embarrassed that my own government seems to revel in overthrowing governments that fail to put U.S. interests at heart. That many of these were democratically elected has not saved them.

The U.S. has been trying to overthrow the Cuban government since it first formed in 1959 and we are still at it. The blockade is meant to economically squeeze the island and create enough discontent within Cuba to force the ruling Communist Party to step down.

Following historic protests in Cuba where thousands took to the streets, Cuban officials have repeatedly blamed the six-decade U.S. embargo for Cuba’s food, fuel and medicine shortages.

Our problems are First World problems, but of course the poor in the U.S. will be affected disproportionately as prices rise. That Apple watch and that 65-inch TV might still be sitting at the port on Christmas but we will survive. I just hope our continuing supply chain mess might impress upon Americans the ways our economic embargoes affect actual people (and not just governments) around the world.

…

What Can Amazon Organizers Learn From Walmart?: Dialogue moderated by Alex Han

By Alex Han

This 3 Part dialogue is being published jointly by the Stansbury Forum and Organizing Upgrade.

“Amazon is the epoch-defining corporation of the moment in a way that Walmart was two decades ago,” said Howard W, an Amazon warehouse worker and organizer with Amazonians United, a grassroots movement of Amazon workers building shop-floor power. What can organizers at Amazon learn from the Walmart campaigns in the 2000s? And what can these two efforts teach us about organizing at scale? Unions haven’t successfully organized an employer with more than 10,000 workers in decades, so getting to scale is one of the most pressing challenges for the social justice movements.

To explore these questions, Howard was joined by Wade Rathke, who, as chief organizer of ACORN in the U.S. from 1970 – 2008, anchored a collaboration among ACORN, the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) and the United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW) that aimed to organize Walmart. Since 1980, Rathke has also served as Head Organizer for Local 100 of the United Labor Union, which represents service workers in Arkansas, Texas and Louisiana. Organizing Upgrade Executive Editor Alex Han facilitated the conversation, with participation from International Longshore and Warehouse Union Organizing Director Emeritus Peter Olney (co-editor of the Stansbury Forum). The 90-minute conversation ranged from the philosophical to the granular. We’re bringing it to you in three parts. Part 1 focused on worker organizing, Part 2 on relations with existing unions. Here we look at building broader community campaigns.

Part 3: Engaging the Community, Building a Movement

Alex: I’m actually really struck, Howard, in hearing you lay this out after Wade’s talking about his history and some of that Walmart work. I’m a little bit more struck in a deeper connection to the kind of community organizing that ACORN and a host of other organizations do, working in neighborhoods, working in different locations to build power sometimes in a symmetrical way, sometimes in an asymmetrical way. I’m just really struck by some of those parallels.

We have two employers that were the primary employer in a lot of places. I think of Amazon right now as the default employer like in my neighborhood, in Humboldt Park on the West Side of Chicago. Amazon is a default employer and they’re building a distribution facility about a mile from my house, which will strengthen that. So I just wanted to ask the two of you what you think are keys to building community support around Amazon workers, and how do we link some common interest there?

Wade: The community support was directly aligned to their ability to see their workers leading that fight. And without it, I mean, we just couldn’t make much happen.

We did geo-targeting that we learned from some folks at Gainesville at the University of Florida. We would guess where big box operators wanted to go, and every week we would have a researcher calling all the Planning Departments in those 21 counties to see if there was any activity on those corners so that we could then come up with a preemptive strike against their expansion. In that way, we were able to stop 32 straight stores from being built. Now sometimes they were putting them in wetlands and sometimes—I mean, you know, they were pretty greasy about the whole thing. They were in a hurry but so is Amazon in a hurry.

It was an open campaign compared to Amazonians United. As I said, we surfaced the leaders early. They were able then to be involved publicly in the site fights and in the public hearings with city councils, planning commissions and allies about why we needed them to put the arm on Walmart to give us more protection and authority in the workplace.

If Amazon keeps going the way it goes, in five years probably, 10 certainly, you’re going to have an Amazon location in virtually every community in the country of any size. To get that same-day delivery or next-day delivery, there are just going to be so many locations, and that could be a way to look at a different geographical plan.

Looking at geography allows you to get more density where you have active committees or people who are coming together, and to then build a bridge to real community support, which I think is very possible to move at this point. Amazon has not had good press the last couple of years. There’s a reason Bezos is trying to go to the moon, I think. At the point we were organizing Walmart, Walmart was public enemy number one on the corporate side, and they look good now compared to Amazon. Who would’ve believed that was possible? But yeah, I would try to narrow the focus in order to get more pressure on them. I think it’s hard for a fly to be noticed by the elephant.

Howard: We are aware of the need to also build strength geographically as well. As they try to build out this next-day delivery, same-day delivery promise, they have to locate in the major metropolitan areas, right? They cannot run away there. They have to then concentrate in that way, and their network becomes shaped by the ways that people live, because they are a retailer. So that’s the next horizon that we have to be looking at, and that we are looking at and figuring out how to work on. How do you build that strength on a metro scale to be working as Amazon workers, you know, in New York City or in Chicago and not just in DBK1 or DCH1, which are the codes for the warehouses.

The scale is difficult, and it is something that we think of a lot. What we’ve managed to do so far is very exciting. The power that we’ve been able to build, particularly in a company that a lot of people say is an impossible place to organize at, is very encouraging. But then every now and again you step back and you realize the true scale of Amazon and you think okay, this is a good start, and it’s going to have to pick up and it’s going to have to expand. We are going to need to find allies, we’re going to have to find ways to reach more people, to bring in more folks in order to transform this company that has such sway over so much of our lives.

But there’s another thing that we think about, which is that in the epic struggle between labor and capital, the whole point is that one of the sides has the money and the other side has the people. One of the things that we think about is that if we’re going to make really big, epochal change in this world, not just for workers at Amazon, but for the whole working class, for working people in the U.S. and around the world, Amazon is a huge chunk of that. And right now, it is a chunk that has incredible power and incredible reach and incredible stature, right?

And I think that’s what makes it a particularly important place to make change. But if we’re going to make those sorts of big changes, we have to figure out how ordinary people and extraordinary people are going to make time in their lives and become that movement and become the organizers and pull themselves together. And that is something that drives us fundamentally: thinking of this as building a movement.

.

If you’d like to learn more about Amazonians United, check out their website at

amazoniansunited.org/. If you’re interested in joining the movement inside Amazon, you can submit an inquiry here: https://airtable.com/shr5Bq5sTeMweqJ7f.

…

Part 2: What Can Amazon Organizers Learn From Walmart? Dialogue moderated by Alex Han

By Alex Han

“Amazon is the epoch-defining corporation of the moment in a way that Walmart was two decades ago,” said Howard W, an Amazon warehouse worker and organizer with Amazonians United, a grassroots movement of Amazon workers building shop-floor power. What can organizers at Amazon learn from the Walmart campaigns in the 2000s? And what can these two efforts teach us about organizing at scale? Unions haven’t successfully organized an employer with more than 10,000 workers in decades, so getting to scale is one of the most pressing challenges for the social justice movements.

To explore these questions, Howard was joined by Wade Rathke, who, as chief organizer of ACORN in the U.S. from 1970 – 2008, anchored a collaboration among ACORN, the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) and the United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW) that aimed to organize Walmart. Since 1980, Rathke has also served as Head Organizer for Local 100 of the United Labor Union, which represents service workers in Arkansas, Texas and Louisiana. Organizing Upgrade Executive Editor Alex Han facilitated the conversation, with participation from International Longshore and Warehouse Union Organizing Director Emeritus Peter Olney (and co-editor of the Stansbury Forum). The 90-minute conversation ranged from the philosophical to the granular. We’re bringing it to you in three parts. Part 1 focused on worker organizing. Here in Part 2 we turn to relations with existing unions. Part 3 will look at building broader community campaigns.

This 3-Part dialogue is being published jointly by the Stansbury Forum and Organizing Upgrade.

Part 2: Acting Like a Union—With or Without One?