Thanksgiving in the Stockton Graveyard

By David Bacon

If you drive straight ahead after passing through the cemetery gate, you soon find yourself among dark stone mausoleums. These are the grey memorials to Stockton’s Catholic elite. Along empty tree-lined avenues leaves blow past the stones and their shadows.

If you turn right, though, you arrive at the corner of the graveyard where Mexicans and Filipinos bury their dead. Innocencio Galedo, who migrated to work in Stockton fields in 1922, is buried here. Next to him is his wife Sotera, who joined him from the Philippines after the war. Once a year one of their kids cleans off the two flat grave markers – picking away the crabgrass and putting flowers in the two holes in each stone slab. This year it’s Lillian’s turn.

On Thanksgiving the graves in this corner are a bewildering cacophony. Many families visit them as a part of the holidays. November comes just after Dia de los Muertos, and grave decorations are a jarring combination of pumpkins, skulls and babies. Plastic flowers combine with real ones. Votive candles bear the image of the Virgin of Guadalupe. A small statue, at first glance a dusky figure from a surreal dream, resolves into a chubby infant holding a bird.

Against the fence at the edge of the cemetery, with warehouses visible through the slats, birthday balloons are the memorials left by families who can’t afford elaborate gravestones. Where the children are buried, dolls sit next to little figurines of elephants or cartoon characters, under photographs of smiling sisters and brothers. The little pony, beloved by six-year olds, has become a blown-up metallic unicorn.

After putting her decorations on the flat gravestone in front of her, a girl sits remembering who’s buried underneath. In one large photograph a father stares out from the past. Other families, unwilling to forget the faces of their buried dead, have set small portraits into the stones.

Many tomb decorations celebrate life, as though the person in the ground is still there to party. A bottle of brandy and a beer, a calacas with a guitar, and even a snow globe, surround a flag, two candles with saints, and the statue of a strangely pensive child. It’s an altar for Day of the Dead, in the campo santo, or the holy field that belongs to them.

Walking away, I notice a new burial. An enormous flower decoration spells out DAD – another father receiving his family’s tribute. People say funerals and burial arrangements are for the living, not the dead. The dead, after all, don’t live to enjoy them. But if they somehow were able to see what’s come after they’re gone, those buried under the flat stones and balloons are probably happier than the respectable folks in their grey mausoleums.

…

Photographs Copyright David Bacon

Farewell to Nicaragua (4)

By Matthias Schindler

Justice and democracy need a completely new start

Onofre Guevara López

If there is one person who embodies the struggle for a free and just society in Nicaragua, it is Onofre Guevara López, who has now reached the age of 92. He is a veteran of the Nicaraguan workers’ movement and currently one of Nicaragua’s most brilliant political analysts. He grew up in the poorest conditions and began learning the craft of a shoemaker at the age of 14. Through this work he was able to get the first pair of shoes in his life. Two of his brothers died of tetanus because they did not have shoes and contracted this cruel disease by walking barefoot. He participated in the building of the first trade unions and workers’ parties in the 1940s. He joined the Communist Party, which was called PSN (Socialist Party of Nicaragua) and became editor of various left-wing newspapers. When, still during the liberation struggle against Somoza, the PSN split, he belonged to the wing that in addition to political and trade union work took up the armed struggle and later united with the FSLN. He became the editor in charge of the political opinion and discussion pages in the FSLN’s party newspaper, Barricada. After the revolution he became a member of the legislative State Council. Later, as a member of the Constituent Assembly, he participated in the drafting of Nicaragua’s new constitution. To this day he is a convinced Marxist, socialist and anti-imperialist, but he leaves no doubt that democratic principles must be guaranteed in every form of society. For this basic stance, he left the editorial board of Barricada in 1994, and later was removed as a commentator for El Nuevo Diario. Onofre is the author of various books and continues to publish his political analyses in the internet magazine Confidencial. He never attended university, but his articles are highly analytical and differentiated, and they are also always a lesson in history and political science.

Once again, in the hour of farewell, we talked about the sad state of Nicaraguan society. It has become lonely around him. The political conditions, dramatically exacerbated by the pandemic, make it almost impossible to meet with friends. He talked about his former communist comrades who have gained property and wealth through the FSLN and have now completely thrown their old ideals overboard. Without the revolution and the benefits that followed, they would never have been able to accumulate their new wealth. For this revolution two sons of Onofre gave their lives as Sandinista liberation fighters, and with the students murdered by the regime in 2018, the mourning for his two fallen sons came up with renewed vigour. Nevertheless, he will not give up and will continue the struggle for his political ideals as long as he has the power to do so. In a few days, he will publish his next article in Confidencial and once again use all his historical knowledge and argumentative persuasiveness to fight for a new democratic beginning in Nicaragua.

Vilma Núñez

Those who deal with the current political situation in Nicaragua cannot ignore Vilma Núñez. She is the president of the Nicaraguan Centre for Human Rights CENIDH, and at 83 she is an icon of human rights defence in Nicaragua. As a lawyer, she defended the political prisoners of the Sandinista Liberation Front before the courts of the Somoza dictatorship. Later, she herself was imprisoned and tortured for her support of the FSLN. During the Sandinista Revolution she was Vice-President of the Supreme Court of Justice CSJ in the 1980s. In this capacity, she also clashed several times with the powerful Comandantes de la Revolución in order to enforce trials under the rule of law, especially for former members of the Somoza National Guard. Vilma has been the president of CENIDH since 1990. Independent of the respective government – whether liberal, conservative or Sandinista – she campaigned with this organisation for the respect of the human rights in Nicaragua. She supported Ortega’s stepdaughter in her trial against her stepfather whom she accused of having sexually abused and raping her for years starting when she was a young girl. Faced with the choice of either remaining loyal to her party, the FSLN and Ortega, or defending the human rights of Ortega’s stepdaughter, Vilma Núñez opted for the human rights. She took on the legal representation of the victim and broke with the FSLN, a fundamental legal, political and personal decision that cannot be overestimated.

Since Ortega’s renewed presidency from 2007 onwards, when the undemocratic measures and dictatorial tendencies of his regime began to intensify, she has become an increasingly important voice in defence of democracy and freedom. Following the wave of state repression in 2018 and CENIDH’s strong commitment to defending the victims of this repression, the CENIDH was illegalised. Its premises were occupied by the police, and the entire institution and all documentary material were confiscated. Many months later, a health centre was opened in these premises with great ballyhoo. Some of the CENIDH staff had to flee abroad, and some her best friends avoided contact because some of their relatives held/hold well-paid positions in the state administration. But Vilma continues her work undeterred. Without an office, without the protection of a legal organisation, and only with the support of a very small circle of confidants, her messages are heard day after day in some news item through Twitter, Facebook, Zoom, or e-mail. She is one of the very few persons who, even during the revolution, clearly criticised the lack of the rule of law. Yet no-one has been more self-critical of not having been consistent enough combating the authoritarian and undemocratic tendencies within Sandinism. I feel it an extraordinary privilege to have been able to carry out some of my Nicaragua Solidarity activities together with this impressive woman. Half-jokingly she once told me she had taken a vow not to die before she could see for herself that the Ortega regime had collapsed. I sincerely hope that she can keep her promise because only then will it be possible for us to meet again.

“They express diverse and profound criticism …”

I cannot mention here all the people I met during my last trip to Nicaragua and whose fates are linked to the Sandinista Revolution and its failure. But in almost all my conversations, the same questions kept coming up at the end: How could it happen, that the once so hopeful Sandinista Revolution became the nightmare that prevails in Nicaragua today? What could and should we have done better? But in particular were all the sacrifices that we made, and what others had to suffer, justified in the light of the terrible results of this revolution? It is remarkable that with very few individual exceptions, none of the people mentioned here have fundamentally questioned the justification of the Sandinista Revolution. They express diverse and profound criticism of the most diverse institutions and episodes of this revolution. They can express this criticism with convincing expertise and authenticity because they have all personally been actively involved in these structures and processes for many years. It is to be hoped that, despite everything, their voices will continue to be heard and that they will also be noticed by the younger generation.

Vilma Núñez and Onofre Guevara embody the noblest aspects of the Sandinista Revolution like hardly anyone else. They are distinguished by their personal modesty, their absolute incorruptibility, and their intellectual quality. They are among the very few people who are not prepared to leave Nicaragua and who nevertheless express their criticism of the Ortega-Murillo dictatorship. But beyond that, the continuity, coherence, and consistency of their positions over more than half a century are testimony to their unwavering political and moral integrity. In particular, they embody two fundamental pillars that must never be forgotten when it comes to building a new society; Vilma Núñez for human rights and the rule of law, two principles of order that must always be respected, completely independent of the respective concrete form of a society. And Onofre Guevara for the inseparability of social justice and democracy because one can never be realised without the other. Despite, or perhaps because of their advanced age, they represent cutting-edge, and forward-looking positions, on these fundamental issues. If the fundamental principles they uphold could be realised in Nicaragua, and other places, a great deal would already have been achieved!

¡Adiós Nicaragüita!

One might object that the testimony presented here has no value because it is strongly subjective. Yes, this text is essentially based on my own subjective impressions and experiences in Nicaragua. But no, this does not diminish the value of its statements. They take their significance precisely because no one can dispute the personal experiences I have recounted here. All the political events mentioned here are easily verifiable and have been publicly documented many times. All the people mentioned here are currently living in Nicaragua, even if many of them for security reasons can only be mentioned with a pseudonym. One may not agree with some of my political interpretations, but no one can take away my experiences, my conversations, my joys and my disappointments.

Political circumstances did not allow me to invite all my friends, some of whom are mentioned in this report, to a joint farewell evening. Therefore, I invited my closest neighbours, who had also become very dear to me over many years, to a barbecue. They are simple people, pensioners, domestic servants, workers, clerks, a doctor, artisans and some of their family members. They all used to support the FSLN. Nowadays, they are bitterly disappointed. Only one of them went to the “election” on 7 November because he is employed in the public sector and would have risked his job if he had not participated. That evening, they represented the Nicaraguan people for me, the people to whom I have been committed since 1979. It was a very moving and very beautiful evening.

In 1969, I took part in a demonstration for the first time. It was directed against Nazism, which was gaining strength again in Germany. Then I took part in the protests against the war in Vietnam. Since then, I have been involved in trade union and civil society activities against exploitation and oppression in the world. For over forty years I was active in Nicaragua Solidarity. All the events described here are true and based solely on what I perceived with my own eyes and ears.

This text expresses how much the current situation in Nicaragua depresses me and how much I suffer from not being able to currently change these conditions. But I am only a temporary spectator. How much worse is the situation for those who live under this dictatorship every day? Who currently have relatives in prison, or who are imprisoned themselves? How must those feel who have made great personal sacrifices for the revolution and now stand before the shambles of their former dreams?

Nicaragua, Nicaragüita[1] does not exist anymore. Nor will it come back. But history goes on, a new Nicaragua will emerge. For that to happen the country will need a new political generation that can breathe new life into the concepts of freedom and justice. However, a new beginning always starts with the past from which it emerges. Analysing, and critically reflecting on one’s own history is indispensable for shaping future emancipation processes, ones better and more sustainably than have been achieved so far. If this text can make a small contribution to this, then it has already fulfilled its purpose.

¡Adiós Nicaragüita!

…

[1] “Ay Nicaragua, Nicaragüita” is the title of the most famous song of the Sandinista Revolution, written and composed by Carlos Mejía Godoy, who is currently in exile because of the political repression in his country. It is a declaration of love to Nicaragua and the Sandinista Revolution.

Farewell to Nicaragua (3)

By Matthias Schindler

“If such living conditions are the result of a revolution, doesn’t this revolution have to be questioned as a whole?“

The Many Faces of My Farewell

My farewell to Nicaragua has many personal faces. When I said goodbye to my friends in November 2021, it was in all likelihood a parting forever. Firstly, I can no longer bear to stay in Nicaragua under these conditions, and secondly, it is also quite possible that the regime would not let me return to the country. I had come to appreciate and love my friends over the course of four decades. I learned a lot from them. The memories of our shared experiences in building grassroots projects, in critical reflection, in philosophical discussion, as well as in enjoying Nicaraguan cuisine or some glasses of Flor de Caña Gran Reserva will accompany me for the rest of my life. I have dedicated most of my political life to Nicaragua, and I wouldn’t want to miss a second of it. It was a struggle for freedom and justice, and we must honestly admit to ourselves that we have lost that struggle at this moment. Every single time we said goodbye, the question arose: Was it right to throw ourselves into this struggle? Were the sacrifices we made for this project worth it? Was all our commitment completely in vain?

María Isabel

When I visited María Isabel, we once again let all the important stages that shaped her life pass us by. She kept telling the story of how during the uprising against Somoza, as a young girl, she held a heavily armed National Guardsman at bay from behind with a broomstick and then arrested him. She came from the countryside and only learned to read and write through the Frente (FSLN). Later she became involved in the trade union movement and still works in an independent women’s centre. But in the 1980s she also denounced her sister Juana, whose husband supported the Contra, to the Sandinista authorities. Juana was then thrown into prison for six months. María Isabel still suffers from the fact that she did not visit her sister once during her time in prison. At the same time, it is at least a certain spiritual comfort to her that she could ask Juana for forgiveness and that her sister was able to forgive her before she died. Was it right to participate in a revolution that called on its rank and file to behave so cruelly within their own family? It is an irony of history that nowadays a police officer, loyal to Ortega, lives across the street from her house so she is no longer allowed to speak her mind aloud in the street without risking arrest. Even in her own house we had to talk in a low voice because she had – without knowing it beforehand – taken in a young Orteguist as a lodger and now doesn’t know how to get rid of her. If such living conditions are the result of a revolution, doesn’t this revolution have to be questioned as a whole?

Ingra

Ingra comes from Sweden and went to Nicaragua in the early 1980s to support the revolution. Since then she has lived and worked there. She has initiated and helped to set up various projects. She has created dozens of jobs and organised training in various manual and administrative professions. She has supported guerrillas from El Salvador who had sought refuge in Nicaragua, or had to recover from war injuries. She has also played a leading role in various women’s projects over many years, and still does today. For all these activities, she has organised and handled large sums of international funding. All these projects have been harassed and bullied by the Orteguist state bureaucracy during the last year to such an extent that some of them have already had to stop their activities. Ingra no longer has any deep roots in Europe. She is set on spending the rest of her life in Nicaragua. However, the Ortega regime spends a lot of energy on destroying any grassroots initiative not controlled by it. Ingra’s life dream – a self-determined life serving those most in need in Nicaragua – is in danger of collapsing under these conditions. She is at an age when other people in Europe have been living a comfortable retired life for years. She is a passionate anti-fascist and anti-imperialist. It is unbearable to see this modest, thoroughly altruistic woman being cold-heartedly treated as a “foreign agent” by the Orteguist bureaucracy. Recently, she was urged by a good friend to refrain from making political comments in public. Ingra replied that she was in no danger because it was common knowledge that she had never done anything against the Nicaraguan government, or the FSLN. But her friend – a staunch supporter of Ortega – tearfully repeated her plea for restraint, saying she knew very well how the FSLN would also falsify information if it served their interests.

Luis Felipe Pérez Caldera

In the 1980s, twinning between cities in Nicaragua and many other countries, especially in Europe, was established as an expression of solidarity. The Sandinista mayor Luis Felipe Pérez Caldera was one of the central figures in establishing such a partnership between León and Hamburg (Germany). It is said of him that he had a good relationship with all social and political groups in León. He promised everyone that he would work for their interests. But if he was not able to keep his promises – which often could not be prevented – this in no way diminished the esteem in which he was held by the people.

At that time, there was no internet, no WhatsApp, no e-mails. We wrote letters by hand or with a typewriter with several carbon copies for the archive. The answers sometimes took six months to arrive. Phone calls barely worked and were almost unaffordable. When we visited León, he made it possible for us to talk to whomever we wanted. When the FSLN lost the presidential elections in 1990, León remained firmly in Sandinista hands. But in the political struggle that followed, Luis Felipe took a clear stand against the FSLN’s verticalismo and authoritarianism. Because of his critical stance, his house was later branded with the graffiti “Death to the traitor”. With his inclusive and conciliatory nature, he was the exact opposite of the exclusive and repressive Orteguism that characterises the FSLN today. When I visited Nicaragua, it was an indispensable part of every trip to meet with him and talk for hours about current developments or reflect on historical issues. There was hardly anyone with whom I discussed Mikhail Gorbachev’s book Perestroika as long and intensively as I did with him. Although I knew that he currently was severely limited due to his age, I would never have forgiven myself if I had not said goodbye to he and his wife, in person. He no longer speaks and is largely living in another world. But our last handshake was so strong that I am convinced that he still recognised me, and perhaps deep inside even remembered our times together. Maybe it is good for him not to have to witness all the horrors of Orteguism with full consciousness.

Rigoberto Sampson Granera

His good friend and successor in the mayor’s office, Rigoberto Sampson Granera (affectionately called Rigo) long ensured that an open and free atmosphere prevailed in León while in Managua nepotism, corruption and secret pacts were gaining the upper hand in political life. Twice Ortega visited him personally to dissuade him from running for mayor, and instead imposed one of his henchmen as the FSLN candidate. But Rigo stood firm. He was elected with large majorities in the primaries and then in the municipal elections of 1997. Later he became a deputy in the National Assembly. He never accepted any personal advantages for himself. While Ortega gives his children radio stations, or sends them on state visits to other countries, Rigo has never put a single relative or friend into any well-paid position. When he passed away in 2009, at the evening vela,[1] his entire neighbourhood was blocked by the multitude of mourners. I have not the slightest doubt that today’s obsequiousness inside the FSLN would have provoked deep aversion in him. And I am absolutely certain that he would never have participated in, nor backed, the violent crackdown on the civil protests of 2018. Since he is no longer with us, it was all the more important for me to say goodbye to his family in person.

José Antonio

On the civil society level, the priest and teacher José Antonio was a central hinge in organising the twinning process of the up to 30 schools that had established partnerships between Hamburg and León. He understood better than anyone how important communication was between the partners on both sides. He was not only a living expression of the connection between the Sandinista Revolution and Christianity, he was also an example of the importance of people’s civil commitment in that period. These grassroots twinnings functioned completely independently of the state administrative structures. The mayor’s office of León made an effort to support these activities, but there were no regulations, or even restrictions, on the connections that had grown from below. In this framework, donations in kind and money were organised for many years and on a large scale, not only for school projects in León. However, all this is now a thing of the past and has largely been forgotten. Currently, not a single dollar can be transferred from abroad to Nicaragua without first being checked and approved by the state bureaucracy in Managua in a complicated and tedious procedure. José Antonio was also active in the movement of Christian based communities, but can only continue to do this to a very limited extent for health reasons. But even in this grassroots movement, the idea of solidarity has been partially displaced by Orteguista nepotism and corruption. When we took stock of our joint activities over four decades, we agreed that it was right to have supported the unique project of the Sandinista Revolution with all our strength. But we both also came to the frustrating conclusion that this project has been destroyed by the current prevailing Orteguism. As I left his house into the evening darkness, I looked around again from a distance, I saw him sitting in his wheelchair, and we waved to each other once more. That was probably the last time I would see this great friend and comrade in struggle.

Manuel

Manuel is one of the group of young Chileans who went to Nicaragua to support the Sandinista Revolution after the suppression of Unidad Popular. He has built one of the most comprehensive historical archives on Nicaraguan political developments from 1979 to 2021. He has written, edited, transcribed, and made available to the public hundreds of documentary texts. There is hardly a scholarly work on Nicaragua that does not draw extensively on this archive. The salient feature of this collection is from the beginning it was compiled organisationally and politically independently of the FSLN. This meant that the respective state of the criticism of the policies of the Sandinista leadership was documented since very early on. From today’s perspective, the depth of this criticism may appear inadequate. But the publication of the relevant texts alone has created a rich archive based on which the recent history of Nicaragua and Sandinism can be critically examined in an outstanding manner. The FSLN has not yet opened any of its archives. No one knows whether there are any at all and where they might currently be. But precisely because of the independent character and critical continuity of his archive, Manuel is nowadays very afraid of being kicked out of Nicaragua. He too is now over 70 years old. And where on earth would he be able to once again build a new existence for himself? He made Nicaragua his adopted home country, putting down deep roots, because of the Sandinista Revolution. He has devoted most of his life, strength, and commitment to Nicaragua. But the only thing he can do now is to keep a low profile and hope that Ortega’s ray of banishment will not hit him. This is also the option of almost all the other critical voices that have not yet gone into exile because Nicaragua is their home. Of course, at the moment of our departure our deep political disappointment, our powerlessness in the face of the brutal current conditions, and the sadness of our definitive separation, again began to gain the upper hand because it was clear that I will not travel to Nicaragua again as long as the Ortega regime is still in power. But he replied that we should not cry now. Instead, we should have new hope because Ortega’s speech the day after the so-called elections was the speech of a loser. Although the Supreme Electoral Council awarded him a majority of 76 per cent due to his massive manipulations, he knew that no-one would believe him, not abroad, not inside Nicaragua, not even in his own party. He had to insult the political prisoners as “hijos de perra” (sons of dogs) in his unusual outburst of rage on 8 November. And afterwards, even letting himself be embraced and celebrated by some of the selected guests for this disgusting speech whitewashing the disgrace of the people’s successful boycott of the elections. Ortega, Manuel assured me, is already on the decline and as soon as he has finally gone, we will meet again. He wanted me to promise him that, and so I did.

Mildred

When Mildred had the chance to go to a safe foreign country during the uprising against Somoza, she decided to stay in Nicaragua and take part in the revolution. While she was involved in the Sandinista Revolution, her brother, an elite National Guard fighter, remained loyal to Somoza until the final day. After the triumph, he was captured by the new revolutionary forces and shot dead by his guards in circumstances that have not been fully clarified. Mildred had to organise his funeral. For this, however, she was not only viewed with suspicion by her Sandinista comrades, but on top of that she had to endure her mother cursing her and chasing her out of her house because she blamed her adherence to Sandinism for her son’s death. Much later, Mildred became reconciled with her mother, but the scars of such experiences remain for a lifetime. Mildred worked for many years as a journalist in various Sandinista media. She was also involved in the women’s movement and later became a fierce critic of Ortega. If she had left the turmoil of the revolution in 1979 with her companion and sought refuge in a safe foreign country, she might now be living the life of a highly respected writer, or a well-off professor in Germany or the USA. Instead, she has to stay hidden, living in constant fear of being arrested and thrown into prison as has been the fate of more than 150 political prisoners in Nicaragua.

Nidia

If you have been involved in Nicaragua Solidarity for more than four decades, it would be very unusual not to develop good connections, even very close friendships, with people who, more or less, support the current regime. Nidia’s family is traditionally pro-Sandinista. Her grandparents supported the revolution out of a deep Christian faith. For this, they were first brutally tortured and then murdered by the Contra. Their family history is part of the FSLN’s revolutionary history. It is an expression of the deep roots of the Sandinista Revolution in the poor and largely religious population. And it is also a testimony to the suffering that thousands of devout Christians had to endure because they supported this revolution. Nidia says of herself that she is not an Orteguista, but a Sandinista. Of course, she was shocked when police and paramilitaries used weapons of war against the students in 2018. Her house is just a few metres from where one of the universities came under fire. She knows my critical attitude towards the Ortega regime. But given her political and family history, she feels a loyalty to Nicaragua and the FSLN that is almost unshakeable. It is not possible for her to share her unease, and also her inner criticism of the current conditions with a foreigner, no matter how many years he has been active in solidarity with Nicaragua. When we, as was our habit, went out to share some pleasant moments in a good restaurant it was an unwritten law not to talk about the political situation in Nicaragua. Of course, I could not tell her it was no longer possible for me to meet with friends in a public restaurant if they were critical of the regime or were regarded as such.

Pedro

I have a very close friendship with Pedro that has grown over decades. We may not hear from each other for a year, but when we meet again it is as if we had seen each other the day before. There is no topic we won’t talk about openly with each other. He works on various projects and teaches at university. He is not a formal member of the FSLN, but he supports President Ortega and his policies. During the first protests in 2018, he was pelted with stones by students when he tried to protect a monument to freedom fighters who died fighting Somoza. But he has never taken part in violent actions against opposition members. When I told him at our meeting that this would be my last visit to Nicaragua and that I would never return, it was a great shock to him. He was deeply affected by this and did not understand why I had come to this decision. I tried to explain my decision to him with some concrete examples, without entering into a general ideological debate, or making political accusations against him. So, I told him that I had met many people who feel great fear at the moment. Who no longer dare express their opinions publicly, fear losing their jobs if they do not participate in the political activities demanded of them and who fear being spied on by their neighbours. He replied that he couldn’t understand that at all, and literally added: “I don’t feel any fear at all.” I have not the slightest reason to doubt this, and it may be one can live quite unconcerned as a supporter of the government. But even though some of his family members are highly critical of Ortega, the idea that opposition members would be afraid of being arrested and thrown in jail was completely alien to him. I know that he holds Vilma Núñez in high regard. However, he also reacted with incomprehension to my pointing out that the Human Rights Centre, of which she is president, had been deprived of its legal status by the government. Instead, he pointed out that such things are more likely to be discussed in Managua and not so much in the cities on the periphery. When I then added that it was unacceptable that world-renowned writers like Gioconda Belli or Sergio Ramírez did not return to Nicaragua because they were afraid of becoming victims of repression, he replied thoughtfully that there were indeed some things that were not going so well in Nicaragua and that no country in the world could develop without freedom.

Jaime

In 1984 I met Jaime, a young teacher and trade unionist and since that moment we have been in regular contact with each other. He is highly educated, has studied in different countries, has obtained various academic degrees, and is highly qualified in both sociology and technical disciplines. He has supported the FSLN since a young age, but according to his own statements, he was not involved in any repressive measures during the 2018 clashes. He is prepared to take part in any discussion, is a good listener and openly states his own opinion, forms of communication that not everyone in Nicaragua masters. When we got to talking about the 2018 protests, he showed me the death threats against him and his family that he received on his mobile phone. He told me quite openly that – independently of whether the criticisms of the government may be justified – he cannot forgive the perpetrators of these threats. Nevertheless, he tries to keep in touch with some old political acquaintances who nowadays belong to the opposition, because he knows that at some point, a dialogue between the government and the opposition will have to take place and it will require people who can re-establish the relevant contacts. We spent many hours together discussing all possible aspects of the current political situation in Nicaragua. He did not deny that there are democratic deficits, nepotism, and corruption under the current government. But in order to justify why he considered Ortega’s presidency to be the better alternative compared to the opposition candidates he kept talking about the new asphalted roads, the new hospitals, and the electrification of the country. He considered it right that people like Dora María Téllez or Hugo Torres, among many critics of the regime, are currently in prison.[2] Although no evidence has been presented publicly, he is firmly convinced that these two outstanding former commanders of the Sandinista liberation struggle have attempted to organise an US supported military coup d’état to overthrow the Ortega-Murillo government.

…

Farewell to Nicaragua (4) Justice and democracy need a completely new start

[1] Mourning service at the home of the deceased on the evening of his death.

[2] Hugo Torres died in prison on 11 February 2022.

Farewell to Nicaragua (2)

By Matthias Schindler

Stages of Alienation

My estrangement from Nicaragua was a long process that stretched over several decades. It was not my intention to go down this path, but now I have come to its end. It began with a deep identification with the goals of the Sandinista Revolution and a great ignorance of Nicaragua and the people who live there. It ended with many people in Nicaragua being closer to me today than ever before, while my connection with the FSLN has reached absolute zero. However, I am firmly convinced that it was not I who distanced myself from the revolution, but the FSLN itself that first forgot, and later betrayed, its own roots and its original goals.

Of course, political conditions and convictions have not remained static on either side from 1979 to 2022. But while the once revolutionary Sandinism developed further and further in an authoritarian and finally even dictatorial direction, I have become increasingly convinced that democratic structures and methods have an essential meaning for all social development. Without them, every emancipatory claim is just smoke and mirrors.

At this point, I can only mention a few significant stages that were important for this process of separation. More detailed explanations can be found in my book From the Triumph of the Sandinistas to the Democratic Revolt: Nicaragua 1979 – 2019,[1] which unfortunately has not yet been published in English.

In the beginning, there was an almost unadulterated enthusiasm for the revolution. The sacrificial struggle against Somoza’s dictatorship, and no death sentences for the former oppressors after the triumph. The construction of a self-determined Nicaragua and the coming together of Marxism and Christianity. Political pluralism, the expropriations of the former dictator, and more found broad support within Nicaragua and internationally, including mine. When the USA started to attack this revolution politically, economically and militarily, I did not hesitate to get involved in the worldwide solidarity movement for Sandinista Nicaragua. From the beginning it was clear that we, as solidarity committees, did not see ourselves politically or organisationally as an extension of the FSLN, but as an independent movement in support of the revolution.

The first serious test came in 1981 with the armed conflicts between the Sandinista army and the ethnic group of the Miskitos on the Atlantic coast of Nicaragua. Important parts of the German solidarity movement publicly criticised Managua’s repressive measures. However, this criticism was still accepted as solidarity-based criticism by the FSLN leaders at the time. Furthermore, after more conflicts and even forced relocations, an internal discussion process among the Sandinistas eventually led to a dialogue with the Miskitos, and later even to the elaboration of an autonomy statute for their settlement areas, which was internationally regarded as exemplary for the rights of ethnic minorities in their states.

Later we heard of the arrest of leading representatives of the PCdeN, one of two communist parties in Nicaragua, and its affiliated trade union CAUS. We did not agree with this either, but it was seen as a minor issue.

During the 1980s I travelled to Nicaragua many times. I conducted educational tours, organised solidarity projects, visited grassroots projects, collected information material for solidarity work in Germany, provided translation services, and even participated in international political activities. During this time, especially in León, I was able to immerse myself deeply in Nicaraguan society and get to know the Sandinista Revolution from the inside. However, despite all the sympathy with the people and all the support for their revolution, it became clear in many situations that Sandinism suffered from a lack of internal democracy, and that it was strictly vertically organised from top to bottom.

This was combined, especially in the second half of their government, with an ever-increasing personality cult regarding the nine Comandantes de la Revolution, the FSLN’s highest governing body. This became especially clear through the repeatedly chanted slogan: “Dirección Nacional: ¡Ordene!” (“National leadership: command!”).

After the FSLN’s 1990 electoral defeat, the so-called piñata[2] occurred before the government was handed over to the newly elected president, transferring many companies, lands and other properties from state ownership to the private ownership of high FSLN officials. This was the birth of a new “Sandinista” capital group in Nicaragua. However, I did not realise until many years later that this was one of the decisive turning-points through which the quest for wealth and power on the part of the party leadership became more and more prominent, coming into ever clearer contradiction with the original social and political goals of the FSLN.

Pulled quote: Since this incident the solidarity movement has been divided between those who feel justified supporting a rapist as president, and those who reject this as an inadmissible crossing of boundaries.

In 1998, Daniel Ortega’s stepdaughter, Zoilamérica Narváez, publicly accused him of having sexually abused and raped her over many years, beginning in her early childhood. However, this was either strictly denied by every possible instance of the FSLN or merely considered a pardonable peccadillo (minor sin). The FSLN saw no reason to remove him from the party leadership or even to withdraw him as their presidential candidate. I found this matter an unacceptable political and ethical scandal. Nevertheless, at that time I was not prepared to sign an appeal demanding that Ortega be stripped of his parliamentary immunity so that he could be held accountable in court. My argument at that time was that such an appeal could also be signed by right-wing opponents and politically misused against the FSLN. Only years later did I realise that this was the biggest political mistake I ever made in Nicaragua solidarity. It was only much later that I understood that elementary human rights, such as the right to physical and mental integrity, apply unconditionally and must not be subordinated to political interests under any circumstances. Since this incident the solidarity movement has been divided between those who feel justified supporting a rapist as president, and those who reject this as an inadmissible crossing of boundaries. But it also revealed a split between the solidarity movement and the FSLN that could never be healed.

New political shocks were caused by the 1999 pact between Ortega and Alemán, in which both agreed not to touch the parliamentary immunity of the other to protect each other from prosecution; Ortega for the rape of his stepdaughter and Alemán for the embezzlement of over 100 million dollars of public funds.

Only a few days before the 2006 presidential elections, the parliament passed an absolute ban on abortion with the votes of the FSLN to win over the official Catholic Church under Cardinal Obando y Bravo and various Protestant sects. While some Sandinistas initially touted this as a clever electoral manoeuvre, the increasing openly fundamentalist and pseudo-religious appearances of the president’s wife, Rosario Murillo, made it clear that women’s right to self-determination would remain profoundly violated by this ban in the long term.

Nevertheless, many activists of the solidarity movement associated Ortega’s re-election and his assumption of office in 2007 – despite all the criticism – with a cautious hope for an improvement of the situation in the country. He had run a very moderate election campaign, but at the same time he had also campaigned for a departure from the neoliberal policies of the three previous liberal-conservative governments and announced a fight against corruption. I decided not to accept the invitation to attend his inauguration. After all, he had only been able to win this election with barely 38 percent of the vote because of his pact with Alemán. Moreover, it was known that the highly corrupt Alemán had also been invited as a guest of honour – for me, a situation I could not accept. It would soon become clear that my scepticism was completely justified. Already in the local elections of 2008, there was massive electoral fraud in favour of the FSLN and violent attacks against political rivals, especially in the capital Managua, as well as in León and many other cities. The system of electoral fraud has been perfected since then by the FSLN’s ever-growing control over the electoral authorities from election to election.

In 2009, some judges of the Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Court declared Article 147 of the Nicaraguan Constitution, which prohibited the re-election of the president, unconstitutional. This means that the highest state authority for the defence of the constitution did exactly the opposite of its actual mandate and partially declared the constitution invalid. This allowed Ortega to run again in the 2011 elections, which he subsequently won. Only much later, in 2014, was the possibility of presidential re-election legalised by a corresponding parliamentary resolution. In other words, the facts were created first, but the legal basis was only established with hindsight. This process was a major milestone in the abolition of the rule of law in Nicaragua.

Between 2007 and 2017, Nicaragua received almost four billion dollars in economic aid from Venezuela. These funds were not channelled and controlled by Nicaragua’s state budget, but by the private company ALBANISA whose board was under Ortega’s direct control. In addition to social and infrastructural projects, large amounts of these funds ended up in the pockets of his family and closest friends. This not only promoted an unprecedented level of corruption in the state and society, but also brought the second major capital boost, following the 1990 piñata, for the newly emerged “Sandinista bourgeoisie”.

What is particularly repulsive is how Ortega-Murillo’s children, who have never had a serious education, are given entire business enterprises by the state, are entrusted with the highest state functions, or host state-financed luxury fashion shows. Depending on the mood of the presidential couple, they are sent on diplomatic missions around the world, or are allowed to live their lives as third-rate rock or opera musicians at state expense. Nicaragua is still the second poorest country in Latin America, but its ruling family lives in feudal opulence.

In 2013, the planned construction of an inter-oceanic canal through the middle of Nicaragua was the focus of public interest. This project was to be realised in cooperation with the Chinese swindler Wang Jing. It was to have a cost of 40 billion dollars and be paid off over 100 years. From the beginning, there were massive political, economic, ecological, and social objections to this project. To pave the legal way for this, a corresponding law was whipped through parliament, in a fast-track procedure, within 72 hours. Later even the Constitution was amended for this purpose. The legendary freedom fighter Sandino had a clear position on the question of such a canal through Nicaragua, which had already been discussed 100 years ago: Firstly, he strictly refused to put such a project in the hands of a foreign international superpower, and secondly, he declared that such an undertaking could only be carried out – if at all – as a joint Latin American project.

The Last Illusion

In April 2018, there were largely peaceful mass demonstrations against the Ortega-Murillo government. But the regime responded with extreme brutality under the slogan “¡Vamos con todo!” (“Now it’s all or nothing!” or “Any means will do!”). This destroyed even the last illusion. The last taboo had fallen. The regime’s armed formations were shooting at their own people. Military snipers, police and paramilitaries wreaked havoc. There were over 300 deaths, over 2,000 injured, over 600 political prisoners and over 100,000 people seeking refuge abroad. The independent judicial commission GIEI[3] concluded that the government had committed crimes against humanity.

As Ortega’s political power increasingly asserted itself within the FSLN, and from 2007 onwards in the Nicaraguan state system, the character of the town twinning arrangements, which had developed primarily between Germany and Nicaragua, also changed. Political solidarity with a social emancipation process and help for self-help, gradually became a business model to organise external funding for local development projects. The authorities loyal to Ortega profited from this in two ways: On the one hand, they were able to present themselves to the ordinary population as benefactors, and on the other hand, this left the Nicaraguan state with more funds to expand its repressive apparatus. In return, the local Nicaraguan rulers patiently listened to the German side’s references to the importance of democratic structures, without ever responding to them or taking them seriously in any way.

“The Cybercrime Law makes all statements critical of the government, made publicly or privately, in any medium, or on any platform on the internet, punishable by one to ten years in prison.”

Since September 2020, the Ortega regime has passed four laws legalising state repression. The Foreign Agents Act puts international solidarity organisations on the same level as arms dealers, spies, and terrorists. In addition, employees in projects that receive financial support from abroad automatically lose their right to stand for election. The Cybercrime Law makes all statements critical of the government, made publicly or privately, in any medium, or on any platform on the internet, punishable by one to ten years in prison. Under the Act against Hate, any criticism of the government is treated as spreading hate and carries a maximum penalty of life imprisonment. For this, even the Constitution was amended because the maximum sentence up to that moment had been limited to 30 years in prison. Finally, the Sovereignty Law stipulated that people who advocate outside interference, or support sanctions against Nicaragua, or Nicaraguan citizens, are traitors to the fatherland and thus also lose the right to run for any public office.

On 20 June 2021, the left-liberal internet magazine Confidencial was raided by the police, its production rooms occupied, computers and other work equipment confiscated and some of its staff arrested. Its editor-in-chief, Carlos Fernando Chamorro, had already been forced to take refuge in Costa Rica for security reasons. On 13 August 2021, the editorial offices and printing press of the conservative newspaper La Prensa were occupied by the police, and the publication of its printed edition was banned after 95 years. However, both media continue to appear via the internet.

The “elections” of November 2021 were the culmination of electoral manipulation and at the same time the definitive end of the illusion that democratic conditions still existed in Nicaragua. At that moment, there were 150 political prisoners, including persons who wanted to run for the presidency. All public meetings and rallies were banned. The election campaign was limited to internet activities and social media messages. All parties that participated in the voting process ran directly in alliance with the FSLN or had other links to that party. Independent election observers from home or abroad were not allowed. Under these conditions the vast majority of the population stayed at home on election Sunday. Those who had participated had to have their right thumb marked with a non-washable paint. In the following days I looked at people’s hands everywhere I went, and only about one in ten people had their thumbs marked. Afterwards the hand-picked government-invited acompañantes electorales (electoral companions) – not “observers” – from friendly organisations of other countries, praised this voting process in the highest terms, agreeing completely with the Orteguista propaganda media not only concerning the technical procedures but also in their choice of words.

On 1 February 2022, political trials began against prominent opposition representatives who had already been in pre-trial detention, or under house arrest, for up to 9 months. On 2 February 2022, 6 private universities were illegalised by depriving them of their legal personality. Opinions may differ on how to assess the information in these newspapers, or how to think about the teaching in the universities in question, but the suppression of a free press, free university teaching, and the persecution of political dissenters, can only have one result, the further intellectual impoverishment of Nicaragua.

If there is one overarching phenomenon to be observed at present, it is this: There is fear in Nicaragua. There is fear on the street, in the restaurants, on buses and taxis. Fear of one’s neighbours, fear of colleagues at work, of superiors. Fear of police checks on the roads, and even fear in the family, or one’s own circle of friends. Of course, many people can be seen sitting quietly in a rocking chair in front of their houses, children playing exuberantly in the street, or families enjoying loud music and cheap food at the Salvador Allende amusement park, as if everything was fine. But if you know the people better, if you speak to them in their language, and if you have been able to build a real relationship of trust with them, then you can experience how great people’s fear is. Fear of saying something wrong somewhere, of being overheard, of ending up on one of the black lists or even of being arrested. At the same time, the presence of the police in public is currently much smaller than it was one or two years ago. But the brutal repression of any critical movement in public during the last three years has left deep scars on everyone. Everyone in Nicaragua knows that even the slightest attempt at public protest would have the police on the scene within minutes to crack it down.

“In this way he gradually expanded his position of power, by ostensibly democratic means, in order to then further destroy the democratic functioning of society from within.”

Ortega only came back to power in 2007 through a pact with his corrupt accomplice, Alemán. With the municipal elections of 2008, the FSLN expanded its power through massive electoral fraud. Ortega was only able to win the 2012 presidential elections because the Supreme Court overruled the constitutional ban on re-election. Before the November 2021 elections, Ortega had many potential presidential candidates thrown in jail, and had all opposition parties banned to enable him to celebrate his own “election victory” afterwards. In this way he gradually expanded his position of power, by ostensibly democratic means, in order to then further destroy the democratic functioning of society from within. This finally led to the “democratic” abolition of democracy and the establishment of the full-scale dictatorship that Nicaragua is currently suffering.

If you want to travel to Nicaragua nowadays, you first have to fill out a digital entry application form, in which you not only have to enter your name, passport number and travel dates, but also who invited you, their email and postal address, why you want to travel to Nicaragua, what “special reasons” you have for going there, whom you want to visit there, and more. Once you have sent this application to the Ministry of the Interior you will receive an acknowledgement of receipt, but no information as to whether your entry has actually been approved or not. On the corresponding homepage, the status of this entry application remains frozen as “in process” until long after the journey has been completed. Whether someone is really allowed to enter Nicaragua in the end is only decided immediately, on the spot. Only half an hour before departure, at the last transit airport, will the passenger know whether or not he/she will be allowed to board the plane bound for Managua. This was the way in which the journeys of many international journalists ended at the airports of Panama, or Mexico City, before the “elections”. They had to turn back without having achieved anything because the Nicaraguan authorities had forbidden the respective airlines at the last minute to let them travel on to Nicaragua. If I had written on my entry application that I wanted to see for myself the situation of democracy and human rights in Nicaragua I would certainly have been refused entry as well. But I got through because I had given “tourism” as the reason for my trip. Finally arriving in Managua I had to undergo another interview at passport control, which was more like a political interrogation, and where I had to avoid any impression that I was travelling to Nicaragua out of political interest. After 43 years of active solidarity work with Nicaragua, I was now treated like a drug trafficker or an imperialist spy! It is true that – unlike many others – I managed to enter Nicaragua once again. But I am not prepared to get used to such a treatment. The idea of having to endure such a humiliating situation once again is unbearable for me. As long as the Ortega-Murillo regime is still in power, I will not return to Nicaragua.

Chickens vs. democracy?

Supporters of Ortega often do not know how to justify his dictatorial regime. That is why they keep coming back again and again to the hospitals and new roads built under his rule. They try on the one hand to distract from the debate on freedom and democracy, and on the other they want to show how good his government is despite existing criticisms. Since Ortega took over the presidency again in 2007, there have certainly been some improvements in the country’s infrastructure as part of the capitalist modernisation of the country. These are not Ortega’s benefactions, but basic tasks that every state has to fulfil. Moreover, the financial resources for this did not come from Ortega but from abroad. On top of that, large parts of these funds did not flow into these projects but ended up directly in the pockets of Ortega’s closest relatives and friends. But above all – and this is the crucial point – asphalted roads, or new hospitals, are no argument at all when it comes to freedom and democracy. After all, the motorways built under Hitler, or the industrial progress of the Soviet Union under Stalin, are not acceptable justifications for their reigns of terror. Whoever thinks that social progress justifies violations of human rights and military oppression of the people should then also clearly, and unambiguously, do the maths: How many kilometres of newly built highways justify the abolition of democratic elections? How many new health centres can be a justification for trampling the country’s Constitution underfoot? How many wind turbines must a president approve to be allowed to give his ignorant children television and petrol stations? How many new sewage pipes justify throwing political dissidents into jail? How many electricity connections does a government have to lay to be allowed to banish human rights organisations into illegality? How many zinc plates must a ruler give away to be allowed to keep a highly equipped private army of paramilitaries? Or how many chickens must the ruling couple distribute to the poor before they may order protesting students to be murdered by snipers?

One has nothing to do with the other? Then, dear supporters of the Orteguista dictatorship, please do not start connecting these issues! You are the ones who bring up the roads and the hospitals because you don’t want to talk about the undemocratic conditions in Nicaragua. And you don’t want to talk about them because you know very well that there is unbearable political repression in Nicaragua, and that in you can’t present any acceptable justification for it.

At the same time, you should never forget one thing: dictatorships come to an end. All dictatorships come to an end. Hitler’s ended. Stalin’s ended. Somoza’s has ended. The Ortega-Murillo dictatorship will also come to an end. We don’t know when, and we don’t know how. But it will end. Then, at the latest, you will have to think about how to go on. And you will have to think about whether you want to be treated in the same way as the current regime treats its critics and opposition members – when government power and all state authority is no longer controlled by Ortega.

Sovereignty vs. Human Rights?

As a second important issue in defence of the Ortega-Murillo regime, its supporters often point out that every state has the right to regulate its internal affairs freely, according to its own ideas. This is absolutely correct. However, this principle of sovereignty, which originated in the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, was supplemented after the Second World War by the obligation of governments to respect human rights. The experience of fascism under Hitler led to human rights becoming a core component of national and international law. Accordingly, no government has a right to violate human rights in its own country and to oppress its own people. This is why human rights have become an integral part of many of the constitutions written after 1945.

This is also the case in Nicaragua. The Nicaraguan Constitution clearly declares that every person living in Nicaragua enjoys the full protection of human rights, as enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights by the United Nations. Yet in real life there is hardly any article of this declaration that is not massively violated in Nicaragua.

Article 46 of the Constitution reads: “In the territory [of Nicaragua], every person enjoys State protection and recognition of the inherent rights of every human person, the full respect, promotion and protection of human rights, and the full validity of the rights set forth in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights of the United Nations, and the American Convention on Human Rights of the Organisation of American States.”

…

Next: Farewell to Nicaragua (3) The many faces of my farewell

[1] German: https://diebuchmacherei.de/produkt/vom-triumpf-der-sandinisten-zum-demokratischen-aufstand/; Spanish:libros.matthias@gmail.com; French: https://www.syllepse.net/nicaragua-1979-2019–_r_74_i_843.html

[2] A piñata is actually a game played at birthday parties in which children have to grab as many sweets as possible for themselves.

[3] Grupo Interdisciplinario de Expertos Independientes (Interdisciplinary Group of Independent Experts), a commission invited by the Nicaraguan government to investigate the events of April and May 2018, which published a 463-page report.

Farewell to Nicaragua: Part 1

By Matthias Schindler

From total enthusiasm to complete disappointment

Farewell to Nicaragua, part 1 of 4, running over the next two and half weeks

On 21 December 1983, I set foot on Nicaraguan soil for the very first time. Although I had been active in the solidarity movement with Nicaragua since the fall of the dictator Somoza and the coming to power of the Sandinistas, this was the day that changed my life and linked me to a revolutionary liberation movement in the Third World for several decades. On 21 November 2021, I left Nicaragua for the last time. I was saying goodbye to a country to whose liberation and development I had dedicated over forty years of my political life. I left behind a country whose revolution had been betrayed and irretrievably destroyed by some of its own former leaders.

Both dates had deep political and emotional significance for me. The first date meant connecting with a living revolution, also referred to here as Sandinism. As part of an international solidarity movement, I wanted to contribute to defending it against the brutal attacks of US imperialism, to support it with the reconstruction of the country, and to accompany it critically. Since then, I have spent a total of more than two years in Nicaragua in the context of various tasks and projects. I met many people who left a lasting political mark on me. Deep personal friendships also developed with some of them over this long period of time. The second date meant acknowledging that the Sandinista Revolution had definitely, and irreversibly, failed. On that day, I left some of my best friends behind and will probably never be able to see them, let alone hug them, again. However, this inevitably poses the task of coming to terms with this failure, explaining how it could have come about, recognising one’s own errors and, if possible, outlining alternatives that will finally make it possible for social revolutions to become long-term success stories.

In the following text, I will try to present some essential insights that I gained during my solidarity work with Nicaragua between 1979 and 2022. This is primarily neither a historical account nor a political analysis, but a summary of my most important personal experiences, including everything I have read and written during this period. Personal encounters and relationships with people that have developed over many years also play a major role.

The purpose of this text is to help me and others involved in this process to understand how Nicaragua, and the international solidarity movement with Nicaragua, developed during this period. I would also like to present how I have positioned myself in this context and how I position myself today. At the same time, I will try to make clear the reasons why I took certain positions in various key situations and why my political assessments have, in some cases, also changed. With a pointed statement, I would like to contribute not only to looking at the current situation in Nicaragua, but also to reflecting on important milestones in Nicaragua’s development, which ultimately led to the current situation.

International Work Brigades

In 1983, I flew to Nicaragua as a participant in the first German International Work Brigade. It was called Todos juntos venceremos (Together we shall win). We wanted to express our solidarity with the Sandinista Revolution through our presence and through our peaceful work. We also wanted to make it as politically difficult as possible for the US government to take military action against Nicaragua. Only two months earlier, US President Ronald Reagan had sent US airborne troops to the small Caribbean island state of Grenada, sending a clear signal regarding the plans he had for Nicaragua.

The Nicaragua Information Office in Wuppertal had chartered an entire Russian passenger plane to take 180 mostly young men and women from West Germany and the Netherlands across the Atlantic. When we got off the plane in Managua, we were all greeted individually on the airfield with a handshake by the Minister of Culture, Ernesto Cardenal. This poet, priest and revolutionary was one of the most famous representatives worldwide of the Sandinista Revolution. Besides us, other brigades came from more than twenty other countries, mainly from Latin America, but also from the USA and elsewhere, to participate in this international campaign. Many of us felt that we were taking part in an activity with world historical significance and that we were helping to shape the history of humanity’s emancipation in a small way.

Following its defeat in the Vietnam War in 1975, in the 1980s the USA wanted to reassert its military supremacy in the world. We opposed this using civil and political means. We even hoped that after Nicaragua the military dictatorships in El Salvador and Guatemala would also fall and a self-determined and independent Central America could emerge. This was also expressed in the slogan chanted everywhere at the time, “Si Nicaragua venció – ¡El Salvador vencerá!” (“If Nicaragua has won, El Salvador will win too!”).

The Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional (FSLN, Sandinista National Liberation Front) was founded in 1961 as a political-military organisation, inspired in particular by the Cuban revolution and the national liberation movements in the late 1950s, as well as by its most important inspirer Carlos Fonseca Amador. It named itself after the Nicaraguan freedom fighter Augusto C. Sandino, who fought against the US occupying forces from 1927 to 1933. In the 1960s, the FSLN was a small organisation composed mainly of students and peasants operating in remote mountainous areas with very few weapons and weak logistical support. In the cities they carried out sporadic urban guerrilla actions, but as an armed group they posed no real threat to Somoza’s powerful National Guard. In the mid-1970s, there were three political currents within the FSLN that differed on issues of struggle strategy to overthrow the Somoza dictatorship. In 1978, when a broad popular movement of an insurgent character was already developing under the leadership of the FSLN, the three currents joined forces and elected a common leadership instead of an all-powerful general secretary. The FSLN pursued a skilful policy of alliances and enjoyed great popular support which, combined with a favourable international balance of forces, made possible the victory of the Sandinista revolution on 19 July 1979, after the last Somoza to rule Nicaragua had left the country and Somoza’s National Guard and the state apparatus had completely collapsed.

In Sandinism, Marxism and Christianity were united. It had a common leadership, composed of different political currents. There were various political parties both to the right and to the left of the FSLN. The liberation movements of El Salvador and Guatemala were each composed of several parties. We had every hope that a new political chapter would be opened in Central America, in which socialist, democratic, and humanist ideals would merge into a new social model that could become a credible alternative to both capitalism and fossilised Soviet-style socialism.

In our places of work, picking coffee or building houses, we saw a true Sandinista popular mobilisation. We were captured by the authentic enthusiasm of the people who wanted to participate in the construction of a free and self-determined society. We witnessed small grassroots activities in the neighbourhoods, mostly organised by women, and large mass demonstrations, often resembling exuberant celebrations. And we witnessed with admiration and emotion how thousands of young people volunteered to take up arms, risking and in many cases losing their lives for this revolution. A large part of the population and the vast majority of the youth actively supported the revolution and had a deep trust in the Sandinista leadership. What a contrast to the German Democratic Republic (GDR)! Many of us West Germans had experienced the grey and repressive Soviet-style “real socialism” in the GDR. There, people only dared to express their opinions freely when they were within their own walls or walking in the forest. The Stasi was in fact, or at least in people’s minds, omnipresent. In Sandinista Nicaragua, on the other hand, it sometimes seemed as if we were at a permanent popular festival.

Clouded view

What many of us did not see in that phase of great euphoria and almost unlimited hopes was the fact that part of the population – especially in the countryside – that did not agree with the revolution. For some, the Sandinista project did not go far enough, for others it went much too far. But the FSLN was a small guerrilla group, whose core consisted of a few hundred fighters, who in the last months of the uprising had gathered around them at most two thousand armed men and women. The FSLN was not an established party with a clear programme and an experienced and tested structure. From one day to the next, it suddenly had the entire state power in its hands and had to govern the country. This almost inevitably led to authoritarian mechanisms also being applied, probably having to be applied, from the first moment of its rule.

But it was hardly possible not to be caught up in the general spirit of hope and optimism that prevailed in the country at that time. Several tens of thousands of people inspired by solidarity – mainly from the USA and Western Europe – flocked to that small country in Central America to support the building of a free and self-determined society through their work. Out of 100 of these internationalists, 99 enthusiastically returned to their home countries and supported the expansion of solidarity there. However, these immediate social and emotional impressions clouded our critical view of the dark sides of the Sandinista system.

Furthermore, the USA waged a brutal war of destruction against Sandinista Nicaragua. It contradicted all the rules of international law and was even condemned by the International Court of Justice in The Hague in 1986. The political anti-imperialism of a large part of the international solidarity movement made it even more difficult for us to see that there were also internal conflicts in Nicaragua that led to dissent and criticism. A part of the rural population joined the Contra,[1] organised and led by the USA, to wage an armed struggle against the Sandinista government. These campesinos were by no means just puppets in Washington’s hands. They also had their own interests, which were not properly understood nor answered by the FSLN leadership for a long time.

Within the Sandinista Revolution, there was a conflict from the beginning in which freedom and democracy on the one hand were opposed to authoritarianism and oppression on the other. For many years, however, this second side of the coin was not seen, or at least not paid sufficient attention, by the international solidarity movement. This dark side grew in the FSLN in a long, complicated and sometimes contradictory process until it fully asserted itself within the last three years. Absolutely nothing remains of the original democratic goals of the revolution in Nicaragua. The autocratic dictatorship of Ortega-Murillo is the sad conclusion of this development.

All hopes dashed

Since my first visit, I had visited Nicaragua many times on various missions. When I left the country for the last time in 2021, all the hopes associated with the Sandinista Revolution, both within Nicaragua and internationally, had been completely dashed. Socialism was not built. Today, Nicaragua is further away from democratic conditions than ever before. There is almost no article of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights that is not massively trampled on in Nicaragua. The FSLN that attracted the attention and sympathies of the international left has long since disappeared. Instead of a collective leadership of the FSLN, there is an autocratic leader who has concentrated all the levers of state power in his hands. The revolution has not spread in Central America, but the virus of dishonesty and corruption has also destroyed the Salvadoran liberation movement Frente Farabundo Martí. Gioconda Belli and Sergio Ramírez were forced to go into exile. The Casa de los Mejia-Godoy no longer exists. The editorial offices of the newspaper La Prensa were occupied by the police, so that it had to cease publication in printed form and limit itself to its internet presence only. Police forces have also occupied the production premises of the internet magazine Confidencial for the second time in a few months and robbed it of its means of production. The best Nicaraguan artists and intellectuals were either driven out of the country or forcibly silenced.

Any independent grassroots initiative is viewed with suspicion by the state. If they seek international support, they are suspected of espionage or terrorism. Internationalists who once came to the country to help build a self-determined society are now harassed and boycotted by the government. Grassroots projects in which they work are deliberately driven to ruin. Instead of a reconciliation between Christianity and Marxism, there is no sign of either under Ortega-Murillo. Their regime is more politically isolated than ever before. If the Sandinista Nicaragua of the 1980s had looked like the regime in power today, not a single work brigade would have gone to Nicaragua and there would never have been an international solidarity movement with Nicaragua.

Then, in April 2018, the last little – albeit extraordinarily important – hope proved to be a mere illusion. Even the harshest critics of the current ruling system, which I call Orteguism in this text, were convinced that the Nicaraguan police and army would never turn their weapons against their own people. However, when peaceful mass demonstrations against the regime caused Ortega-Murillo to fear for their power, they ordered a bloody repression of these protests. This led to more than 300 deaths, which have never seriously been officially investigated and whose perpetrators enjoy total impunity.

The large-scale electoral fraud of 7 November 2021 completes the circle. Sandinism has been shattered from within both as an idea and as an organised political force, and Orteguism has fully asserted itself as the political regime in Nicaragua. The liberation process that began in 1979 with the overthrow of the Somoza dictatorship as a truly popular revolution came to a sad end in 2022 with Ortega’s fourth consecutive presidency in a renewed patrimonial dictatorship.

…

Next: Farewell to Nicaragua (2) Stages of alienation

[1] A civil war army, the vast majority of whose members were small farmers and whose leadership included many members of Somoza’s former National Guard. It was financed, equipped and led politically and militarily by the USA and sought to overthrow the Sandinista government.

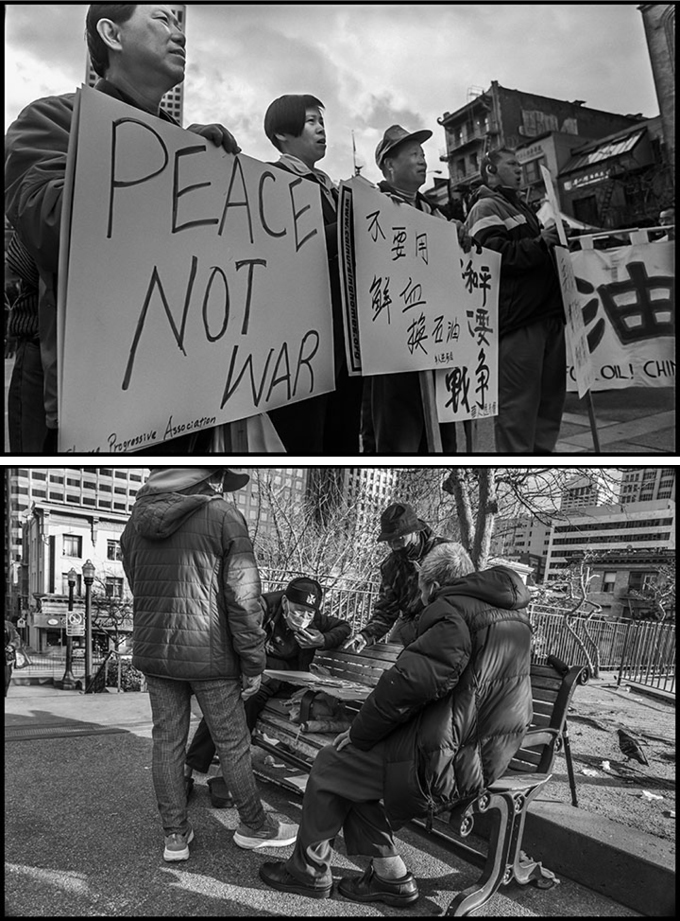

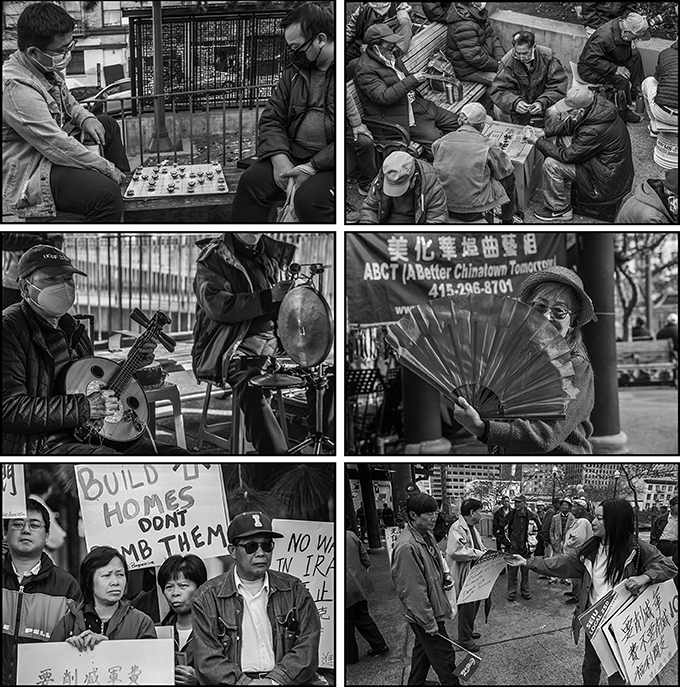

Photographs of Portsmouth Square

By David Bacon

In presenting these images of Portsmouth Square, in San Francisco’s Chinatown, I’ve tried to keep in mind some of the ideas of Paul Strand, the great modernist and realist photographer.

Strand was a radical, a founder of the Photo League in New York City in the 1930s, and a teacher who guided its work. After World War Two, as McCarthyite hysteria gripped the country, and especially the world of media and the arts, he was put on a blacklist (along with the Photo League itself) by the U.S. Justice Department. He went into exile in France, never returning to live in the U.S. For the next three decades he photographed people in traditional communities, and in newly independent countries during the period of decolonization and national liberation.