Myth and Reality

By Hardy Green

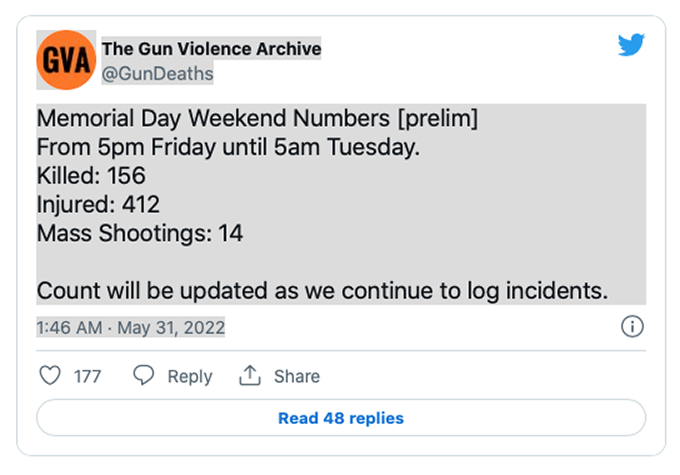

The violence of the Old West has been widely described—and magnified in countless Hollywood productions. But a look at the record of Wild West violence shows that it was nothing like as bloody and horrific as the current spate of AR-15 murders across the U.S.

A little background: In the immediate post-Civil War years, a number of “cattle towns” sprouted up across Kansas, encouraging great drives of the immense Texas longhorn herds to these railheads. Dodge City, Abilene, Wichita, Ellsworth, and Caldwell all came into being and flourished between 1867 and 1885. In 1867, a mere 35,000 head of Texas beef were driven to Abilene, with perhaps 20,000 being shipped to points east. Wichita and Dodge City, each with links to the Santa Fe railroad, rose as important shipping points in the 1870s. In 1882, 200,000 head of cattle were sold in Dodge City alone; by 1910, 27 million cattle had made the trek from Texas to the Kansas towns.

But famously, when cattle drives ended, they unleashed upon the towns dozens of rowdy cowboys—suddenly flush with end-of-drive pay and eager to cut loose. Catering to their wants were legions of prostitutes, gambling halls, and 24-hour saloons. Brawls of every sort resulted: During Abilene’s second cattle season, 1869, one cowboy rode his horse into a saloon, pulled a gun on the bartenders, and upon exiting, engaged in a shootout with numerous other “desperate characters.” The towns were thus compelled to effect a variety of peace-keeping mechanisms—one of the most common being hiring a crew of former gunfighters as a police force.

All the same, in the words of historian Robert R. Dykstra’s 1970 work, The Cattle Towns, there were relatively few fatalities. “Many legendary desperadoes and gunfighters sojourned in the cattle towns at one time or another, but few participated in slayings,” he writes. These notable badmen included Doc Holliday, Clay Allison, and the teen-aged gunman John Wesley Hardin. Nor did badge-wearing gunslingers contribute much to fatality stats: “Wild Bill” Hickok killed only two men during his one term as Abilene city marshal; Dodge City’s Wyatt Earp, only one; and “Bat” Masterson, also of Dodge, killed none at all.

According to Dykstra, between 1870 and 1885, total homicides in the five cattle towns amounted to 45.

Many of the wanton cowpokes were likely no older, and probably no less unhappy, than the Uvalde, Texas killer, Salvador Ramos. But a six-shooter bears no comparison to the AR-15 that in only a few minutes fired off over 100 rounds in Uvalde—or to the other AR-15s used in every recent U.S. mass killing from Pittsburgh’s Tree of Life Synagogue to the Sandy Hook Elementary School in Connecticut to the Buffalo, N.Y. supermarket.

It’s no wonder the Uvalde police were afraid to face the shooter.

…

This article appeared previously on Hardy Green’s blog

Winning (Time) Isn’t Everything

By Byron Laursen

Winning Time (the HBO series) is based on writer Jeff Pearlman’s 2014 book “Showtime: Magic, Kareem, Riley, and the Los Angeles Lakers Dynasty of the 1980s.” I didn’t write that book and remain dismissive of its reliance on gossip-y, horny-porny topics. But the emergence of the series has brought many questions my way, including some from Peter Olney, a long-term friend (and co-editor of the Stansbury Forum), an admirable worker for “la gente,” the common folk.

The book I did write, which was my first, is “Show Time: Inside the Lakers’ Breakthrough Season”, done with and for Pat Riley, the former player who became the Lakers’ coach and guided them through the 1980s, first as assistant coach then as head coach beginning in 1982.

If memory serves, Sports Illustrated called them the best team of the century – in any sport.

When the book behind the series came to my attention, I couldn’t help noticing they’d borrowed the title Pat and I had used in 1988, giving it a minor typography tweak. Since titles can’t be copyrighted, I didn’t begrudge the author for borrowing it. It had been conferred by our publisher anyway, not by us, because it was marketable. And the book became a strong best-seller, for which the publisher paid us a nice wad of bonus money. I’m still grateful to Pat for choosing me to write it.

Winning Time is enormously successful as entertainment, not as documentation, but entertainment fulfills important needs. The first season also covered a time span before I got lucky enough to be a fringe character around the Lakers organization. Still, I have some bones to pick.

Let’s start with the late Jerry Buss, owner of the Lakers. He was angry that we’d used “Show Time” because in his mind he believed he would one day write a book with that title. He didn’t leave behind any book, as it turned out. But he did leave some impressions. My exposure to Buss was limited. In fact, the friendly hour or so I spent interviewing him was more time than I needed or desired. The charisma in John C. Reilly’s performance as Buss exceeds that of the man he portrays by a huge multiple. In my experience, Buss exuded beyond-ripe body odors from the pits of his single-color silk shirts, and in scoring his numerous “dates” had the services of a couple of guys anyone would describe as pimps. They sorted and culled from the female talent hanging around after games in hopes of making it with one or more of the players, found the one(s) willing to settle instead for the rich guy who paid the players’ salaries, and guided them to Buss.

Jerry West I barely met. But I never saw or heard evidence that he was the tantrum-throwing hothead he’s portrayed to be in the series. Still, he was tightly wound. When I asked him a potentially ticklish question – about a trade Buss wanted to make, one that would have proved stupid – he refused to answer. I shelved the question and moved on. Within two minutes he circled back and answered the question at length, as if needing to unburden.

Kareem, Michael Cooper, Jamaal Wilkes, and many other insiders also disagree with how West was characterized. West has threatened the series producers with a suit. I imagine he could win.

Chick Hearn, the announcer, was his own greatest fan and in my experience a miserable s.o.b. I didn’t know about his alcohol habit until seeing the series, but it fits with his personal behavior. His shtick was so tedious that when I watched from home, I turned off the sound. He liked to believe that he was a power in the organization. But when word went around that Hearn said he disapproved of a certain trade and would make his feelings known, West reacted with laughter.

I should add that Riles never spoke ill of either Buss or Hearn, both of whom were instrumental in his career and deserving of his respect.

Pat may feel honored to have a great actor like Adrien Brody portraying him, I doubt he was ever as stylistically clueless as the Winning Time wardrobe department has made him – no doubt to build contrast for the closet full of bespoke suits he began assembling when his paychecks grew. Before the Armani connection was made, he liked his pants with a welted seam on the legs – a flashy choice, but subtle. In more recent years, Pat has acquired a lead-sled customized postwar Mercury from ZZ Top guitarist Billy Gibbons, and some vintage electric guitars, so he remains a fan of the things that were cool when he was a kid.

Kareem has complained that the portrayal of Magic makes him seem like a simpleton easily led around by the sexual honey constantly being offered, and that his own portrayal makes him seem like “a pompous prick.” Kareem is in fact a complex guy, the “brother from another planet” to many of his teammates, and not comfortable with being the focus of all the personal attention that comes with being extremely tall, talented, intellectual, trail-blazing and fame-worthy. There were times when I saw him as a prick, but I’ve also seen the shy guy who would like to be left alone with his headphones and his music.

What else?

In Magic’s first game and first win as a Laker, he didn’t feed Kareem in the post for the game-winning hook shot. That was done by teammate Don Ford, with a long inbounds pass. I’m sure there are plenty of other halfway-true elements from on-court and off. But Winning Time is no documentary. It’s reductionist, slappy, heavy on the gossip, and it pushes limits in order to convey how much excitement Los Angeles felt for their Lakers through the 1980s. In that pursuit, the show needs to be hyperbolic because the reality was that Magic and Company, Riles and staff, gave L.A. fans an amazingly enormous and long-lasting lift through the decade. It was a generous gift. Magic – Earvin to his family and Buck to his teammates – really is a great presence in any room, magnetic and joyful, with a sense of appreciation for his fan support, even when he might wish to have some time off from the adulation.

Theresa Volpe Laursen, my wife, worked in costuming for the 1989 Eddie Murphy film Harlem Nights. At the cast and crew wrap party, Murphy and other celebrities (Arsenio, etc.) had their party in an exclusive room. We never saw them. But Magic spent much of the evening rubbing shoulders with the drivers, costumers, camera operators, and other down-to-earth folk. Asked to pose for photos, he always obliged, and his smile never faded. Just as he did while running the Lakers to greatness on the court, he made sure everybody had their moments of glory and belonging.

Maybe the second season of Winning Time will give him, and all the Show Time Lakers, a more grown-up and truer to life representation.

…

They Built This City?

By Hardy Green

The current issue of MIT Technology Review is focused on so-called cybercurrencies and contains a jaw-dropper of its own: Crypto millionaires have plans to build their own private cities in Central America.

In an article entitled “Cities Built by Crypto,” tech writer Laurie Clarke describes how, in a plan endorsed by El Salvador President Nayib Bukele, that country is selling $1 billion worth of debt in U.S. dollars to fund the construction of Bitcoin City and Bitcoin mining operations.

The Salvadorean project is not alone: Other crypto investors are leaning on governments from Puerto Rico to Honduras to create semi-autonomous enterprise zones that, they say, will stimulate growth and enrich the locals.

Sounds like more enterprise-zone flapdoodle, you say?

Yes, it seems the Ayn Rand-devotee crowd intends to keep plugging its dubious no-downside, rugged-individualist social vision until there’s a real meltdown.

There’s more to the Salvadorean plan: Bitcoin City’s economy will run on that cybercurrency, be powered by geothermal energy from Conchagua Volcano, and be largely free of taxes…if things go according to the plan.

There’s even a non-profit foundation dedicated to the proliferation of such crypto-cities around the planet, the Free Private Cities Foundation. In such cities, as envisioned by foundation President Titus Gebel and former World Bank economist Paul Romer, residents pay an annual fee for such services as policing—and if the services aren’t provided, these “contract citizens” can take the supposed provider before an independent arbitration tribunal.

To me, the author of a book about company towns, it all sounds a bit like a company town…as envisaged by a lawyer. But there’s a lot yet to be disclosed: Would the managing enterprise own all institutions—from the hospital to the newspaper to housing and the company store—as in such company towns as Kannapolis, N.C. or the original Lowell, Mass.? I mean, there’s already company “scrip,” a.k.a. Bitcoin…so why not?

And what happens when the next pandemic hits? I mean, if such towns’ citizens are all just independent free actors, just what entity will tell them there should be curfews or a lockdown? Who would tell people they must wear masks or get vaccinations?

Oh, I see—forget about public health. In this life, you’re on your own.

…

For more reading:

The Conversation

Fortune

Rest of the World on Próspera

This article appeared previously on his blog

At the Border of the American dream: The Hidden World of New Mexico’s Colonias

By Photos/Story by Don J. Usner - Searchlight New Mexico

Rural communities near the border lack amenities, but thousands call them home.

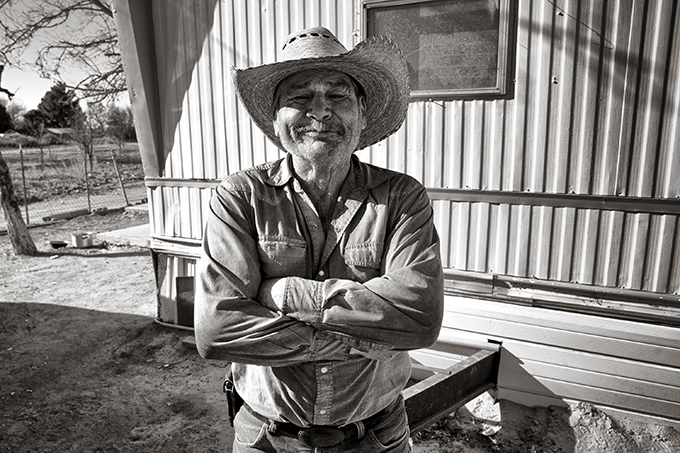

Fidel Pérez made his way from Durango, Mexico, to Juárez and then to Chaparral, New Mexico, in 1970. He was cleaning yards and working in the agricultural fields of nearby Anthony when border patrol officials arrested him. When they asked why he had come to the United States, he replied, “Because I’m hungry! And it’s easier here to make money for tortillas than it is back in Mexico.”

Later, after he’d married an American, he returned to Chaparral. It was one of many informal communities known as colonias, a word that, in the Southwest borderlands, connotes just the kind of place where he’d landed: a rural unincorporated settlement populated almost entirely by Mexican immigrants and lacking such amenities as paved roads, electricity, water systems, wastewater treatment and decent housing.

Right: Pérez, in his kitchen, shows his green card, which he keeps handy in his wallet. After 52 years in the United States, he owns three rental units in addition to his own home.

Pérez is one of the thousands of laborers who’ve traveled north of the border in search of work. Squeezed out of established housing markets by price — and by overt racism — these low-wage workers have sought new places to settle. Landowners and real estate developers in New Mexico, seeing an opportunity, have found ways to offer what the newcomers wanted: cheap land. And the lax laws outside of established municipalities allowed landowners to subdivide property without providing basic infrastructure.

The resulting small, poorly designed subdivisions started as little more than clusters of makeshift houses and mobile homes — often with only a few dozen residents. They grew rapidly, offering people like Pérez the possibility of land and homeownership. Hundreds of colonias soon sprang up along the Mexican border from Texas to California, and today there are more than 2,000 of them. In New Mexico alone, there are more than 140 colonias, home to some 135,000 people.

Lots were often sold using unscrupulous contract-for-deed arrangements and other predatory lending practices. Buyers — who often didn’t speak or read or write in English — had to navigate through loosely regulated real estate contracts in a legal system they may not have understood well. A purchase often left them without a legal title for their small, unimproved lots of land without electricity, gas, a sewage system or indoor plumbing. Some buyers wound up locked into a cycle of debt that exacerbated their poverty.

Appalling conditions in New Mexico colonias prompted local and regional governments to reckon with them in the 1990s. The state attorney general attempted a crackdown and subdivision laws were amended to close loopholes, but by then the colonias were well established.

Today, it’s easy to drive right by a colonia and not even see it. In New Mexico, they are typically situated between towns within a couple hours’ drive of the border — the majority within striking distance of the Interstate 10 and Interstate 25 corridors and smaller feeder roads. Amid the rush of semis bouncing between urban centers, commuter cars carry laborers from the colonias to their jobs in farm fields, factories and service industries in El Paso and around Las Cruces.

Immigrants chasing home ownership can still find relatively inexpensive land in the colonias. Infrastructure has improved for the most part, thanks to local activism and government and nonprofit programs. A few colonias have incorporated and grown to include a few thousand or more residents. Some have gained a measure of status as bona fide towns. But despite their ubiquity and the large numbers of people who live in them, they remain largely invisible to most New Mexicans. I traveled to southern New Mexico this year to bring them into view.

.

Voices from the colonias

“I’ve lived here in Palmeras, maybe about two months. But I’ve been here in the States for a good long while. Like 25 years. I come from Mexico, from Delicias, Chihuahua.

“My woman, she is working now, in Anthony. She is from Coahuila. We are renting here. My landlord was very cool. He was Mexican. He owned all of this, and he just died. Now the one who is in charge is his son-in-law. He’s very good, too. He’s charging me cheap — $175 per month.”

— Cecilio Salinas

“Well, I lived in El Paso, but I am Mexican, from Juárez. And that man next door, he’s from Juárez, too. I am originally from Meoqui, in the state of Chihuahua, but I was actually born in Delicias, Chihuahua. I’ve been living here 10 years.

“A gentleman sold us this property, but it was a fraud. We paid $18,000, and that was because it was a friend of that man and he sold it to him, and now he doesn’t want to give us our money, and he wants to throw us out of here. But he doesn’t have the title. And now we’re not paying rent. We’re just here. We don’t give him any more money.”

— Marisela López

“I’ve lived here almost five months. I was working in El Paso at a tattoo shop and studying to become a professional tattoo artist. But the transportation into town was an issue. So I couldn’t add to my education. I’m from El Paso originally. My parents ended up moving here when I was like, 10. And now I’m 29. I live here in this place, part trailer and part house. And all the way in the back of this property is my neighbor. And then over there, all the way in the back over there, there’s another neighbor. This neighborhood is pretty crowded, but everybody gets along. It’s pretty chill here. There are a lot of Mexicans here. I was born here in the U.S. I guess you would call me, like, a Chicano.”

— Bryant Chacón

“I am from Jiménez, Chihuahua. I’ve lived here about 10 years. … There is not much crime here. It is very quiet. Very nice here. Very comfortable because nobody messes with us.

“We go to Mexico for vacations — when they give us vacations. Because I work, yes, I work, in a dairy. We work 12 hours, from three in the afternoon until three in the morning. Four days a week. That’s why I was asleep, because today I got out at three in the morning, milking the cows, with machines.”

— Celia Rey

“I’ve been here 20 years. In this trailer. I am from Guadalajara. And I came here to work. And I lasted 12 years working, and then I got sick with epilepsy. And then I broke my leg. I didn’t feel good anymore. I am disabled. I’m here in the chair, or just in bed. Due to epileptic seizures and high blood pressure.

“Once I was about to get married, but my woman cheated on me with a friend. There in Mexico. And I was traumatized. The trauma has gone away a bit. But I’m afraid of falling in love. Because they say that people here, the women just want papers. And I have papers.

“But I no longer go out. I get bored, I get sick, I go to bed, it’s my routine. Sometimes I feel depressed or something, I go out, I get distracted with my babies — that’s what I call my dogs, babies. If sometimes I feel like this, I put them inside here, and they see that I feel bad, and they see that I fall asleep, and they see that I don’t wake up, they start crying, they think of cheering me up, they get on my body here. And they let me know when people arrive.”

— Vicente Fuentes

“I came to the U.S. 15 years ago and we have lived here in Milagro for 12 years. I come from Guanajuato, Mexico. Far away, by car, almost 24 hours. My father arranged papers for us. He lives in Hatch. We have resident status. And I started to work the moment that I arrived. I worked in the fields, or in the dairy. There are a lot of dairies here. And there’s lots of work in the fields here. Onions, chili.

“This colonia was really small. Maybe just 12 houses here. Way back then the road was just rough dirt, there was no drainage, and now there’s a good road that drains, and there are more houses. We have potable water, but no natural gas. Just propane. And yes, we have electricity.

“It’s very quiet, peaceful. Relaxing. I come from work, get up on that chair, sleep really well on the trampoline. No problems, no nothing. When I married my wife, I wanted a house, a home in Hatch, but it’s very expensive there. So, I saw this house trailer, already here on this land, and a man told me, ‘Hey, do you want to buy my land?’ And in those years the price was good, it was a whole lot to buy here. ‘Give me this much,’ he said. ‘OK.’ And I paid every month, and now it’s paid off — thanks to God.”

— Miguel Diáz

“I was born in Chihuahua, Mexico, in a little town called Los Garcias, near Meoqui. My mother was born in the U.S., and that’s how we were able to arrange our resident status. She’s Mexican, but she was born in Pomona, Calif. She married my father and they moved to Mexico. They had all their children there, nine in all. And none of us are left in Mexico — we all moved here — my parents, too.

“When we first arrived here, in 1974, we came to La Union, near Anthony, and we worked on farms. Then I worked for nine years in Amarillo, Texas, in the slaughterhouses. And then I found this valley, and I liked it — the climate and the people. It’s really peaceful here.”

— Enrique Garcia

“I was born in El Paso and I grew up in Chihuahua, Mexico. I have citizenship, and so do my kids, who were born here, too, in Las Cruces. I came to the U.S. six years ago, for my kids and the schools. I have three kids, 14, 11 and 9. I drive every day to El Paso, 20 miles, to take them to school. … We have been living here in La Mesa for three years. And thank God everything’s OK, so far so good.

“My husband works. Somebody has to work! We’re a team: He works, and I’m in charge of the kids. He works with livestock, for a company in Del Rio, Texas. It’s seven hours from here. He works with cattle that come across the border. Around 300,000 head cross the border and they’re taken in trucks to feedlots. He comes home on weekends.

“We have a very good life here. We bought this trailer, and the land, and everything is paid off, thanks to my husband. I travel to Texas for the schools, because they’re better there. But we’re very lucky. We’re very happy here. We’re going to stay here.”

— Cecilia Moya

…

The Stansbury Forum is grateful to @SearchlightNM (Twitter) @SearchlightNewMexico (Facebook) who produced and first published this piece. They are an absolutely great site for news of New Mexico and all issues that affect the country whether rural and non-rural. We strongly recommend you visit them on a regular basis.

Searchlight New Mexico is a nonpartisan, nonprofit news organization dedicated to investigative reporting in New Mexico.

Peter and the Peloton!

By Peter Olney

The 105th running of the Giro d’Italia begins on May 5, Friday. The Stansbury Forum is happy to present the cycling exploits of co-editor Peter Olney in Florence, Italy on March 20th of this year.

.

One of the first tasks upon arriving in San Frediano, our neighborhood in Florence, is to rent a sturdy “bicicletta” for our two months in Italy. At the corner of our street, Via del’Orto and Via del Mago di Oro, is Cicleria Iandelli run by Riccardo Iandelli who was an up and coming junior cyclist in his youth. He found me a sturdy city bike, which means no clip ons for the pedals and wider tires for the cobblestones. He threw in a lock and a helmet for 200 Euros for two months.

Each day I would try to ride to explore a new place. I am hoping to mail home “proletarian postcards” from places off the tourist trails. As you can imagine they are places with working class communities, often near manufacturing locations like Sesto Fiorentino, Campi Bissenzi and Nuovo Pignone in the northwest, and hill towns like Bagno a Ripoli and Impruneta to the southeast. These are longer excursions, often 15 or 20 kilometers. But perhaps my most challenging ride is to Fiesole, the hill town just north of Firenze and just ten kilometers from my door. My usual route to Fiesole includes an ascent to Piazzale Michelangelo where the iconic postcard panorama of Florence is the first stop on any guided tour.

On Sunday March 20, I arrived on my “bici” at Piazzale to find cycling team support cars with roof racks full of replacement bikes, chase cars, ambulances, and a ton of motorcycle cops. I even saw a van emblazoned with the azure blue of the Italian national cycling team. They were parked, massing on the piazzale. It looked like a race was to begin shortly. I kept on riding from the Piazzale and descended to the Arno, crossed the river and after a short flat traverse started the ascent to Fiesole, a five-kilometer ride, but at 7% grade. I tooled along in the lowest gear and was passed several times by younger and lighter riders with state-of-the-art racing bikes. When I finished the final climb into the main piazza di Fiesole I rode towards the statue of Garibaldi and King Vittorio Emanuel II, both depicted on horseback. I saw Carabinieri directing traffic and diverting traffic. I saw a mass of spectators look up to see a lone cyclist: me, entering the piazza. A little ripple of chatter: “Oh the leader, there has been a breakaway….” Then the momentary murmur subsided as the expectant spectators realized the oversized rider wearing no colorful spandex and riding a pedestrian city bike was not part of the “gara per onorare Alfredo Martini” (a race in honor of Alfredo Martini, renowned Italian cyclist and coach of the Italian national team, deceased in 2014).

Soon after I dismounted, the real deal “peloton” came roaring around the corner and further up the hill from Fiesole.

The Gara is 172 kilometers and weaves up and down Florentine hills before finishing in Sesto Fiorentino, the birthplace of Martini. My brief moment as a “breakaway rider” reminded me of the wonderful masterpiece movie made by Charlie Chaplin in 1936, Modern Times. This depression era story features Chaplin as the Tramp, an unemployed worker who sees a red flag fall off a construction truck. He picks up the flag and yells to the driver to stop and take back the flag. Just at that moment a march of the unemployed turns the corner and falls in behind Chaplin carrying a red flag. Then the police attack to break up the march and descend on Chaplin assuming he is the leader of the march.

I suffered no arrests or beatings, but for one solitary Chaplinesque moment, I was the leader of the “peloton” in Fiesole.

…

Readers are owed my “proletarian postcards” from those sites in the Metro Firenze area that are off the tourist trail of museums and cathedrals. They will be forthcoming on the pages of The Forum.

Seize the Time: Biden’s Labor Board and a New Workers’ Up-Rising

By Peter Olney and Rand Wilson

The labor world is abuzz with the April 1st certification victory by the independent Amazon Labor Union at Staten Island’s JFK8 Amazon fulfillment center. Despite the election setback for the second ALU vote at Staten Island’s LDJ5 sortation facility on May 2, the momentum for Amazon workers is still very strong.[1] Similarly, the unprecedented string of organizing victories at Starbuck’s cafes across the country is energizing the labor movement. To date there have been 240 plus NLRB election filings at Starbucks around the county. Twenty-eight of those filings have already resulted in victory for Workers United, an SEIU affiliate. The new level of organizing has overwhelmed the NLRB![2]

We are clearly having a wonderful “labor moment.” Observers and organizers have credited the victories and the momentum to the disrespect shown workers during the COVID pandemic, the radicalization of youth by Bernie Sanders and Black Lives matter, and workers turning to unions out of frustration with Washington gridlock.

However, there is a larger political context for this organizing upsurge. As a result of President Biden’s appointments to the NLRB, the Starbucks and Amazon victories along with many other organizing campaigns, have been aided and abetted by very positive rulings from a reinvigorated national board. NLRB General Counsel Jennifer Abruzzo, a former union-side attorney also appointed by Biden, has adopted an aggressive enforcement stance towards employer unfair labor practices.[3] And as we have noted before[4], the Board’s legal rulings have been accompanied by the bully pulpit of pro-union pronouncements from “Union Joe.”

Starbucks sought to force its employees into regional elections arguing that the appropriate “community of interest” for the bargaining unit in Buffalo should not be the individual stores that workers petitioned for. The NLRB ruled that each individual store constituted a separate bargaining unit, enabling the union to roll up individual victories at the sites where the union was ready to go.

In another significant ruling, after finding significant Unfair Labor Practices at Amazon’s Staten Island Fulfillment Center, the Board ordered management to allow workers to campaign in non-work areas – break and lunch rooms – while they were off shift. This was a huge boost to Amazon Labor Union supporters that enabled round-the-clock meetings with workers.

In a recent shocker for corporate management, the General Counsel issued a memo deeming mandatory “captive audience” meetings to be an unfair labor practice because they constituted coercive behavior in violation of the NLRA. What a wonderful paradox that organizers are now debating whether this is a good thing in light of the fact that where workers have a strong organizing committee such meetings afford in plant organizers a forum to challenge management in front of their coworkers showing the power of on-the-job union leadership.[5]

In a rousing speech to the North American Building Trades Unions’ Legislative Conference, President Sean McGarvey gave effusive praise to the Biden administration for regulatory action and appointments on enforcement of Davis Bacon laws and support for apprenticeship training.[6] Both of which were under attack from the Trump administration. McGarvey’s speech was also extraordinary because he began it with strong support for the protests against the police murder of George Floyd and a condemnation of the January 6th insurrectionists. McGarvey hailed the appointment of former Boston mayor and Laborer’s union leader Marty Walsh as Labor Secretary. Leaders of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union have similarly heaped praise on the Biden administration and Secretary Walsh for their defense of worker interests in the supply chain.[7]

Just as history tells us that working class uprisings happen in spurts and often come from unexpected quarters, history also teaches us that such surges are prodded and sustained by good politics.[8] The National Industrial Recovery Act which passed in 1932, while later invalidated by the Supreme Court, set the tenor of the times and helped spur the 1934 west coast maritime strike that led to the formation of the ILWU. Similarly, the passage of the Wagner Act in 1935 helped spur workers’ struggles for union recognition and collective bargaining in the auto, steel and electrical industries.[9]

The political opportunity of this moment gives workers who are organizing an opportunity for some creative thinking. But it will require concrete analysis of current conditions and assessment of the balance of power. Based on what we have seen at Staten Island: the workers are ultimately in the best position to make the callThe JFK8 victory on Staten Island was not anticipated by most labor “experts” because the ALU filed for an election with only a 30% showing of support — the minimum qualifying threshold on authorization cards. The rank-and-file organizers defended their decision on two counts:

1: Churn and turnover at Amazon means that getting to 70% is nearly impossible

2: Getting to 30% is an amazing achievement and we built our strength from there to win the vote.

The victory at Staten Island’s JFK8 has rocked the labor relations world. The disappointing vote at LDJ5 doesn’t change that. For the foreseeable future, any walkout, work stoppage, or NLRB victory at Amazon is going to be big news. Imagine the reverberations if Amazon workers and their organizations were to file and win elections at multiple facilities around the country — especially in giant metro and logistics markets like NY/NJ, Chicago, or Southern California’s Inland Empire.

It’s not often there is a strategic opening created by the confluence of a favorable NLRB, a supportive presidency, a tight job market, and a roiling economy. This is not a time to cling to paradigms wedded to past conditions and stale practice. Now, at long last, we have an opportunity to “Think Big.”[10]

…

[1] ALU is likely to file unfair labor practice charges challenging the outcome of the election. “Amazon Labor Union stumbles as workers vote down union at second NYC facility,” by Mitchell Clark, The Verge, May 2, 2022, https://www.theverge.com/2022/5/2/23053665/amazon-ldj5-union-vote-results. Also see our, “Viewpoint: Amazon Win Shows We Need an Eclectic and Class-Wide Approach,” by Rand Wilson and Peter Olney, April 08, 2022, https://labornotes.org/blogs/2022/04/viewpoint-amazon-win-shows-we-need-eclectic-and-class-wide-approach

[2] “Starbucks Store Unionizing Surge Tests Cash-Strapped Labor Board,” by Ian Kullgren and Robert Lafolla, Bloomberg Daily Labor Report, April 27, 2022, https://news.bloomberglaw.com/daily-labor-report/starbucks-store-unionizing-surge-tests-cash-strapped-labor-board

[3] “The Memo Writer, Jennifer Abruzzo, general counsel of the National Labor Relations Board, has outlined an agenda that would transform the American workplace,” by Harold Meyerson, American Prospect, March 30, 2022

https://prospect.org/labor/memo-writer-jennifer-abruzzo/

[4] “Wake Up, Everybody! Midterms are Almost Here,” by Rand Wilson and Peter Olney, Convergence & The Stansbury Forum, February 25, 2022, and “The Message from the Amazon Union Defeat in Alabama Is Clear: Keep Organizing,” by Rand Wilson and Peter Olney, In These Times, April 9, 2021, https://inthesetimes.com/article/amazon-union-defeat-alabama-bessemer-rwdsu-pro-act

[5] The General Counsel’s decision on employer mandatory meetings still must gain the national board’s approval. Employers would still be allowed to hold “non mandatory” meetings and just “encourage” workers to attend which by itself would be coercive. which would have to be challenged w ULPs (happening in LDJ 5)

[6] 2022 U.S. Legislative Conference: Remarks by NABTU President Sean McGarvey, https://youtu.be/ENJ3fsRNsWk

[7] https://www.ilwu.org/labor-secretary-marty-walsh-meets-with-ilwu-members-in-seattle-and-tacoma/

[8] “Amazon Workers Are Organizing, and Elected Officials Are Supporting Them,” by Eric Blanc, Jacobin, 4/25/2022

[9] “Organizing, Politics, Mood: Reflections on the 1930s,” by Glenn Perušek, Convergence magazine, May 2, 2022

[10] “Think Big: Organizing a Successful Amazon Workers’ Movement in the United States by Combining the Strengths of the Left and Organized Labor,” by Peter Olney and Rand Wilson, in The Cost of Free Shipping: Amazon in the Global Economy, Edited by Jake Alimahomed-Wilson, Ellen Reese, 2019, https://www.plutobooks.com/9780745341484/the-cost-of-free-shipping/ and “Think Bigger: New possibilities for building workers’ power at Amazon,” by Peter Olney & Rand Wilson, Stansbury Forum, October 1, 2021, https://stansburyforum.com/2021/10/01/think-bigger-new-possibilities-for-building-workers-power-at-amazon

How Border Deployment Led To Union Organizing in Texas

By Steve Early and Suzanne Gordon

When a group of Texas workers started discussing job problems and what to do about them a few months ago, their list of complaints would have been familiar to Starbucks baristas, Amazon warehouse staff, or restive young journalists at new and old media outlets.

With little notice, their employer changed work schedules and transferred employees to a new job location. Some of those adversely affected applied for hardship waivers, based on family life disruption, but many requests were denied. Meanwhile, access to a major job benefit—tuition assistance —was sharply curtailed. Even paychecks were no longer arriving promptly or at the right address. When a few brave souls called attention to these problems, management labelled them “union agitators” who were trying to “mislead” their co-workers.

Operating outside the national media spotlight on recent labor recruitment in the private sector, key activists were not deterred. In mid-April, members of the Texas State Guard, Army and Air Force National Guard declared themselves to be the “Military Caucus” of the Texas State Employees Union (TSEU), an affiliate of the Communications Workers of America. Taking direct aim at Republican Governor Greg Abbott, who has ordered thousands of them to police the U.S.-Mexico border, these TSEU supporters called for greater legislative oversight of such open-ended missions so that Guard members are called up only to “provide genuine service to the public good, not posturing for political gain.”

Union Demands

Their own mission statement announced that they will seek meetings with legislators, the governor’s office, and the state agency known as the Texas Military Department. Union goals include a guaranteed end date for all Guard members on state active duty, full restoration of tuition assistance slashed by Abbott, and immediate access to the same healthcare coverage as other state employees, along with state subsidized coverage “for our families while on Texas Military state mobilization.” To achieve these objectives, they pledged to “build a union which gets stronger with every new member we sign up” and coordinate with other state employees who have a “proud history of organizing” as part of the 8,500-member TSEU.

Hunter Schuler, a Texas Guard member and medic who helped initiate the effort, was one of those labelled an “agitator” for doing so. “None of us would be unionizing if our jobs didn’t suck and without all the negative aspects of the mission,” he says. “There’s not great mechanisms for getting problems to the attention of the top leadership any other way.”

Thanks to a U.S. Department of Justice court filing in January, Texas is not the only state where National Guard members are now organizing. District Council 4 of the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME), which is headed by Jody Barr, a veteran of the Connecticut Guard, is also opening its doors to Guard members called up for in-state duty. AFSCME was one of four public employee unions that sought to clarify that a 45-year-old federal prohibition against unionization by uniformed employees of the U.S. Department of Defense, does not apply to Guard members like Christopher Albani, when operating under state control.

As a member of the 103rd Civil Engineer squadron, Albani helped his home state respond to natural disasters, public health crises, and other emergencies. But, as Barr points out, when Connecticut Guard members were involved in setting up field hospitals and distributing medical supplies as part of the state’s pandemic response, they “were not able to bargain over COVID-19 safety precautions, even though state employees they worked directly alongside were able to have a voice in COVID-19 testing and other necessary precautions.”

Operation Lone Star

It’s often said in the field of labor relations that unions don’t organize workers: bad bosses do. While the validity of that old saw is questionable, it’s certainly been true of a bad boss named Greg Abbott. Last year, with an eye toward his 2022 re-election campaign, Governor Abbott launched Operation Lone Star. This $2 billion a year attempt to police the U.S.-Mexico border with Texas Guard members was necessary, he claimed, because the Biden Administration was failing to do so with the Border Patrol.

Viewed by many as a political stunt, Abbott’s sudden mobilization of 10,000 Guard members took them away, with little notice, from their regular jobs or shorter-term duty in pandemic relief efforts. Nearly 1,000 of the citizen soldiers affected applied for hardship waivers, citing family responsibilities or their civilian work as first responders. A quarter of these requests were denied because, as one Army National Guard veteran explained, “for this mission, if you had a warm pulse, they were sending you to the border. They didn’t care what your issues were.”

Adding insult to injury was the seemingly pointless nature of border duty itself. Its main initial risk was COVID outbreaks among troops packed together in trailers in groups of 30 each. As TSEU reports, “members reported being assigned to 12-hour shifts, which they spent sitting in a Humvee or walking around near an observation post, waiting for something to happen.”As one soldier assigned to a post near Brownsville explained, “If someone comes up, we ask them to stop and wait, we call the Border Patrol. If someone runs, we call the Border Patrol. We’re basically mall cops at the border.” On April 22, Abbott’s mission resulted in its first direct fatality. On a treacherous stretch of the Rio Grande river, Specialist Bishop Evans saw several migrants struggling in the water. The 22-year old African-American from Arlington, Texas, stripped off his body armor and dived in to save them. They survived but Evans was swept away while trying to do, without proper training or equipment, what a local mayor called a “good deed.” At least four other deaths—in the form of suicide—have been reported among soldiers whose mental health problems or financial pressures were exacerbated when they were sent to the border or faced deployment there.

Meanwhile, Abbott’s administration has sharply reduced one of the main incentives for young people like Evans to join the Guard. While the governor was boasting about Operation Lone Star on Fox News and fending off a Republican primary challenge from two other right-wing Republicans, he cut the budget for tuition assistance for Guard members in half, from $3 million to $1.4 million. Previously Guard members, working full-time toward a graduate or undergraduate degree, were eligible for tution reimbursement amounting to $4,500 per semester. That award was reduced to $1,000 for only about 714 Guard members. In addition, as TSEU Organizing Coordinator Missy Benavidez explains, the state’s involuntary, year-long call-up order was highly disruptive for soldiers trying to be part-time students. Some were forced to withdraw from classes in mid-semester; others had paid to pay out of pocket for courses they planned to take, or take out loans.

Second Coming of the ASU?

If the U.S. Army ever reneged on the education benefits–much touted by military recruiters as a reason for young men and women to enlist—any soldier agitating for a union in response would face criminal prosecution. That’s because workplace organizing among active duty GIs during the Vietnam era, became so potentially disruptive of “good order and discipline” that Congress outlawed membership in any “military labor organization,” with the penalty being five years in jail. Before that crackdown, one organizational expression of widespread discontent among draftees fifty-years ago was the American Servicemen’s Union. The ASU issued membership cards, formed local chapters on military bases and on naval vessels, and published a national newspaper. Among its organizational models were already existing soldier associations in Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Belgium, West Germany and the Netherlands (where a union of conscripts won higher pay and reforms of the military penal code). Among ASU’s own demands was the right to elect officers and reject what soldiers might deem to be illegal orders.

TSEU volunteer Hunter Schuler is definitely not in the mold of Army private Andy Stapp, founder of the ASU, who was court-martialed twice for his radical activism at Fort Still in Oklahoma during the late 1960s. Guard member organizing by TSEU and AFSCME follows more in the footsteps of the American Federation of Government Employees (AFGE), which voted in 1976 to amend its constitution to permit the recruitment of active duty service members, helping to trigger the Congressional ban enacted the following year (with the bi-partisan support of Senators Strom Thurmond and Joe Biden). Schuler’s civilian job is deputy clerk for the Supreme Court of Texas. He has a master’s degree in statistics and plans to pursue a doctorate program in that subject at Southern Methodist University.

“I don’t really have any prior experience with unions,” he told me. “Ideologically, I think of myself as pretty conservative, leaning to the right.” In that respect, he has much in common with other “young, adult males who join the military” and “are pretty unfamiliar with unions in Texas.” As a recruiter for TSEU, Schuler has had to reassure some new dues-payers that the union was “not just a bunch of Democrats who want to get Beto O’Rourke elected” (although TSEU has endorsed O’Rourke’s general election challenge to Abbott in November).

Strike Breaker Protection

In Texas and other states, the Guard is typically called out, with much popular appreciation, to help with disaster relief efforts or public health emergencies. On other occasions, it gets drawn into policing. In 1986, for example, a Democratic-Farm Labor governor sent Guard members to protect strike-breakers at the Hormel meat-packing plant in Austin, Minnesota. Thirty-four years later, another DFL governor in the same state deployed Guard members in Minneapolis and St. Paul during Black Lives Matters protests over the killing of George Floyd. And a year ago, the Guard was again posted on Twin Cities street corners, along with local police, in anticipation of renewed civil unrest in the event that former police officer Derek Chauvin was acquitted of Floyd’s murder. When CWA Local 7250 President Kieran Knutson learned that one unit, with 50 soldiers and 15 armored vehicles, was operating out of the St. Paul labor center last April, he decided that “our union hall should have no place in those militarized efforts against the Black community, activists, and working-class people.”

A group of concerned trade unionists from CWA, the Minnesota Nurses Association, and United Brotherhood of Carpenters gathered at the labor center to demand that the Guard members leave. According to Knutson, they spoke one-on-one with the soldiers based there, who were mainly white and from rural areas of the state. The union activists urged them “to break ranks and join the anti-racist movement sparked by murders of Black people by the police.” Guard officers ended the fraternization quickly by ordering that the armored vehicles be loaded up and the labor center evacuated.

Knutson has friends, relatives and fellow CWA telephone workers who served in the Guard, the Reserves, or active duty military. His national union, headed by Air Force veteran and former New York telephone worker Chris Shelton, has promoted membership participation in a Veterans for Social Change program, which collaborates on political education and training with Common Defense, a progressive veterans’ group. As a Teamster member, working for UPS in Chicago twenty years ago, Knutson saw Vietnam veterans who belonged to IBT Local 705 strongly support a resolution against the war in Iraq, introduced by left-wing activists in the local. “I think we need to engage with people in the National Guard,” Knutson says. “Because who they are and the role they play is different than full-time police officers and prison guards even when they are called out to defend the status quo.” His hope is that unionization efforts like TSEU’s might lead to “more potential solidarity between the Guard and people on the street or on strike.”

In Texas, TSEU has long been a vehicle for solidarity among state workers of all types that is not limited to legally defined “bargaining units” of the sort found in states where public sector unionists can engage in formal contract negotiations. Formed 43 years ago, TSEU was a pioneering “non-majority union” in the open-shop environment of the South and Southwest. Its members learned to build workplace organization, based on voluntary payment of membership dues and rank-and-file activism, long before the U.S. Supreme Court, in its Janus decision five years ago, put all public sector unions to that new stress test.

Both white-collar and blue-collar state workers of any rank can join, in any state department, agency, or the Texas university system campus. (When longtime progressive activist and writer Jim Hightower was Texas Agriculture Commissioner, an elected position, he was a card carrying TSEU member). As former TSEU lead organizer Jim Branson explains, “We have a voice on the job because we are an active and growing movement that puts a lot of emphasis on organizing. We have agency caucuses, made up of union activists, who meet regularly to formulate goals and plan actions for winning those goals. From time to time, members of the caucus will meet with agency heads to discuss our goals, and when the legislature is in session, caucus members will speak directly to lawmakers…If a united group of workers act like a union, they can have a voice on the job. It’s not easy, but it can be done.”

One of the things that makes Guard member recruitment a particular challenge is the nature of military service and the degree of management control over this particular group of state employees. “The Texas Military Department is not like a 9-to-5 employer,” Schuler notes. “When soldiers are on state active duty, TMD controls every aspect of your life. Even if they don’t do something that’s obviously retaliatory, there’s a lot of things they can do to make your life miserable, without overtly breaking the law or demoting you.” So far, he notes, “we don’t have union stewards or representatives you can call.” Yet, by forming a statewide solidarity network and generating much favorable publicity, Schuler and others have already demonstrated that military-style teamwork and “esprit de corps” can be put to better use than the border guard duty that led them to organize. “The idea [of unionizing] started as joke,” he told Military.com. “But now we have a real opportunity to make the lives of soldiers better.”

…

This article appeared first in Convergence, a site well worth a visit for articles of interest to thinking people.

A UK War Resister Reflects On Troubled State of “Veteranhood”

By Steve Early and Suzanne Gordon

“life was hard, we were poor, and this took its toll”

Military service in the U.S. and the U.K. promised more than it ever delivered for many post-9/11volunteers. As sociologist and Vietnam vet Jerry Lembcke observes, “this generation of veterans went off to Iraq and Afghanistan with more hoopla than any generation since World War II. But a lot of them, particularly the men, came back deflated and disappointed with the experience they had. It did not live up to the mythology of what war is supposed to be, because there is no glory in these inglorious wars.”

Adding insult to moral injury, hundreds of thousands of modern-day veterans developed long-term medical or mental health conditions that were service related. If these afflictions affected their job performance while still on active duty, the Department of Defense (DOD) thanked many of them for their service by drumming them out in punitive fashion. Depending on their discharge status, many became ineligible for free healthcare provided by the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) or access to free higher education via GI Bill benefits. Under the rules of most old guard veterans’ organizations, they were not even welcome at their local post of the American Legion or Veterans of Foreign Wars.

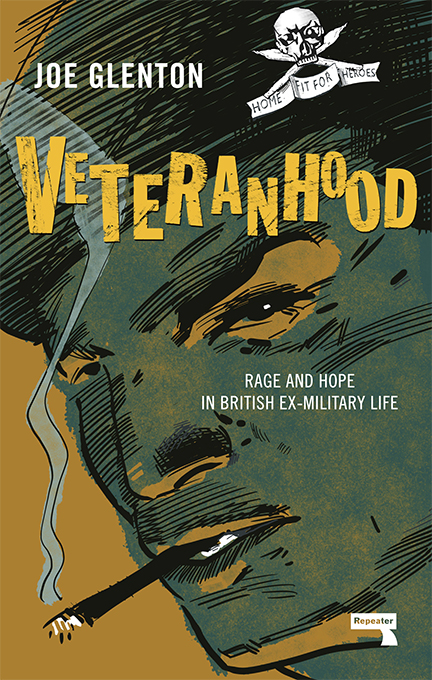

Close readers of Joe Glenton’s new book, Veteranhood: Hope and Rage in British Ex-Military Life (Repeater Books) will be surprised to learn that any Brit who served for even a single day is considered a veteran. Medical care is, of course, less of a concern to former military personnel in a nation where a VA-style National Health Service covers everyone, plus higher education remains far more affordable than in the U.S. And even someone like Glenton–who went AWOL to avoid a second tour of duty in Afghanistan and then was court-martialed for it—later received a package in the mail which welcomed him to the brotherhood and sisterhood of former squaddies. It included, he reports, “one of the small enamel veterans’ badges widely worn among the ex-forces community and a bundle of brochures about getting on in post-military life.”

This UK peculiarity aside, Glenton’s account of how post 9/11 veterans in his country are “getting on” in civilian life reveals many striking parallels with the readjustment problems of their counterparts in the U.S. Now a free-lance military affairs correspondent for the Guardian, the Independent, and other papers, Glenton first wrote about his experience in uniform and afterwards in Soldier Box: Why I Won’t Return to the War on Terror (Verso). In that 2013 book, he confessed that his own enlistment decision was made by “a chump ready made for the army, indifferent, apolitical, and working class.” In rural Yorkshire, “life was hard, we were poor, and this took its toll,” via teenage drinking, drug use, housing insecurity, and minimum wage work.

After Al Qaeda recruits toppled the twin towers in Manhattan, Tony Blair’s Labour government rallied to the side of the Bush Administration. For Glenton, and many other working-class lads on both sides of the Atlantic, this terrorist attack was “the call to arms of the age; of my age.” As his recruiting station officer promised, he “would be paid and there would be ‘three meals a day and a roof over your head’ and girls would queue to swoon over me and my soldier friends.” There would be other opportunities as well, including one stressed on a ‘leaving card’ from his co-workers, on his last day in a restaurant job: “Make sure you kill some ragheads!”

Invaders, Not Guests

During Glenton’s subsequent year-long deployment in Afghanistan, he never got a chance to do that personally, confined as he was to a “logistics park” at Kandahar Airport. As an ammunition store man in the Royal Logistics Corps, he doled out Hellfire missiles and other high explosives “at an astonishing rate,” to fellow soldiers who were not being welcomed as “peacekeepers” outside the wire. Even through Glenton had limited contact with Afghan nationals, the nature of the war began to sink in. “We were not guests, but invaders. We were not friends of the Afghan people, we were occupiers…Insurgencies of the scale we were seeing cannot happen without popular support. I did not have to be a general to recognize this.”

“I had joined the army half meaning to help people, to do something to improve the conditions of other people’s lives, not to occupy other people’s countries under the pretext of securing my own.”

Three years into his military career and recently promoted to lance corporal, Glenton found himself back in England but resolutely opposed to doing another tour in Afghanistan. “I had joined the army half meaning to help people, to do something to improve the conditions of other people’s lives, not to occupy other people’s countries under the pretext of securing my own.” To avoid another combat deployment, he went into exile in Australia. Returning home after two years away, he faced charges of desertion which carried a prison sentence of ten years or more.

The rest of Glenton’s first book tells the story of how his court-martial backfired on the Ministry of Defense (MOD). While awaiting trial but initially not confined to the brig, he became a high-profile peace campaigner. He spoke at Stop The War Coalition meetings, did TV, radio, and newspaper interviews, and personally delivered a letter to then PM Gordon Brown, at #10 Downing Street, which called for the withdrawal of all British troops from Afghanistan. As part of a deal with the prosecution, Glenton eventually pleaded guilty– to the lesser charge of going AWOL—and served four months of a nine-month sentence in a military prison.

Veterans of World War II “were far more likely to come from communities with a powerful sense of their role in the economy, with traditions and experiences of class solidarity and trade unionism.”

On his first night there, “alone and locked in a single cell,” he nevertheless felt liberated. He had found his calling as “an anti-imperialist activist,” and, after his release, completed university studies that helped him become a journalist, film-maker, and award-winning author. In Veteranhood, Glenton returns to the subject of how ending up in the “soldier box,” as he calls it, can have a lasting personal and political impact. In the UK, as in the US, military training “discourages critical thought” and “promotes antagonism” between those who serve and the vast majority of civilians who don’t. Even the author finds himself straddling the resulting “civilian-soldier” divide. After a decade of involvement in left-wing politics, including general election campaigning for Jeremy Corbin, Glenton still finds “dealing with civvies a trial. In moments of regression, they appear to me as ponderously slow, indecisive, dithering, governed by unmanly levels of self-doubt.”

Such estrangement didn’t exist, to the same degree, during the heyday of 21st century “citizen armies,” which included many volunteers and draftees with higher levels of class consciousness. As Glenton notes, “the modern British military has little in common with the military of WWII. Structurally, technologically, ideologically, and morally, these are two different organizations. One was a vast conscript army built…to fight fascism. The other is a small, rather backwards, and culturally separatist professional force.” Veterans of World War II “were far more likely to come from communities with a powerful sense of their role in the economy, with traditions and experiences of class solidarity and trade unionism.”

Some even participated in the so-called “Cairo Parliaments,” a series of quickly shut-down gatherings of active-duty British troops stationed in Egypt. There, under left influence, they debated and voted on proposals for post-war reforms like nationalizing banks and mines, increasing pensions and access to higher education, and building four million affordable homes. In contrast, modern day vets exist in a world, shaped by Thatcherism and individualism, “in which traditional working-class organizations and communities have been diminished and replaced with a kind of warrior-ideal-meets-neoliberalism” As a result, too many ex-soldiers “cling to the only strong identity they have—that of the veteran.” And, as Glenton documents, that’s “an identity concocted by the very institutions that have wronged them”

Blazers or Something Better?

The resulting form of “identity politics” manifests itself, in often negative but some positive ways, across the spectrum. In his own book-writing quest to find “a better way of being a veteran,” Glenton bridles at the facile assumption that his former comrades constitute a solid “right-wing bloc whose politics do not extend much beyond braying racism and lagged-up squadrismo.” Instead, his journalistic portrait of the more than 2 million UK citizens who served in the military reveals them to be “a divided, fractious, and politically divergent group.”

The author does acknowledge that “far right gatherings always seem to include military veterans—bitter men, wraiths in berets,” like those who joined the militant defense of Whitehall statuary about to be targeted by Black Lives Matter protestors. Seven months later, ex-military personnel were disproportionately involved in storming the U.S. Capitol to prevent Donald Trump from being toppled. As Glenton observes, that event—which featured former soldiers stacking up in tight formation to breach the building–became “an upscaled and vastly more lethal American version of our July 2020 anti-BLM riot.”

Glenton devotes a whole chapter to critiquing what he calls Blazerism”— mainstream vet culture, with its hosts of “sartorial signifiers—berets, medals, regimental ties, and blazers.” While Blazers may be vocally anti-socialist and anti-liberal in their social media barrages and voting patterns, they are, as Glenton reveals, quite collectivist within their own “ex-forces community.” For example, many are devoted to British Legion backed charitable work, while always ready “to play homeless ex-serviceman off against migrants and civilian rough sleepers,” who are not among the deserving poor. The century-old Legion soldiers on “as a monolithic, highly political corporate charity and ultimate custodian of Remembrance.” At the other end of the spectrum, Glenton lauds the public education and organizing activity of Veterans for Peace UK. With far fewer foot soldiers, VFP-UK tries to counter “the revanchist nostalgia of Blazerism” by fostering a veteran identity based on broad left values. According to the author, members of the group also tap into what one ex-military nurse calls the “positive experience of their service—the camaraderie, being part of team, and having a sense of purpose.”

Playing The Veteran Card

Glenton is a fierce and hilarious critic of special operators who’ve turned themselves into celebrity vets. Special Forces veteran Ant Middleton is among those, on both sides of the Atlantic, who have “monetized” their military service by peddling books, apparel, or other products under a newly acquired personal brand. Thanks to his second career as a television personality, best-selling author, and “positivity guru,” Middleton raked in four million British pounds in 2021 alone, according to the Sun (which employed him as its “Ask Ant” columnist). As Glenton asks: “Are the people who lost the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan really the people to dish out life advice? Can they supercharge your Bitcoin scam? Can former Navy SEAL Hank McMassive’s ten-point warrior code get you through a long shift at a Nottingham call center? Should you buy their new brand of Predator Drone Coffee.”

The author’s answer is a resounding “No” but that hasn’t stopped major parties in Britain and the US from marketing more veterans themselves as a new breed of politician, somehow better than the rest. The distinct brand of these “service candidates” is their unassailable patriotism and demonstrated past devotion to a cause greater than themselves. Nevertheless, as Glenton reports, “the ex-military people who have found their way into Parliament are mostly conservative former officers,” like Captain Johnny Mercer, Tory Minister for Veterans (until his April 2021 sacking) and “the sullen personification of a failed officer corps.”

Mercer’s counterparts in Labour can be found in its Friends of the Armed Forces. Resurrected in 2020 by Sir Keir Starmer, this group provides little counter-weight to “reactionary ex-servicemen’s dominance in public life” because it’s essentially “a stage prop for the Labour Right.” And, as we document in a forthcoming book, the same is true of the corporate Democrats who play the veteran card in US politics. As members of Congress, they rubber-stamp ever bigger Pentagon budgets, and even betray other veterans by trying to privatize the NHS-style health care system that serves nine million former enlisted personnel.

Not surprisingly, Glenton faults New Labour for initially importing the “American model of soldier-worship.” When the author joined the army in 2004, “soldiers were not popular, and veterans were barely mentioned in the press.” In the period since then, the British state, its generals, MPs, the media, and military charities have engaged in what Glenton calls “a conscious campaign to re-popularize the military.” This “militarisation offensive” was necessary because millions of UK citizens were not big fans of the disastrous foreign interventions backed by Tony Blair. Labour’s response to that domestic opinion problem was outlined in a 2018 “Report of Inquiry into National Recognition of Our Armed Forces,” which included a foreword by then PM Gordon Brown himself. According to Glenton, the report became “an instruction manual for militarists looking to secure public support for war or reduce, to a tolerable level, active public opposition to military occupations” of Iraq and Afghanistan.

The fruits of this long-term project–embraced even more wholeheartedly by the Tories—are often on display. They included mandatory professions of support for the troops by “any parliamentarian broaching a defense topic; the Sun’s cretinous annual military awards and Turbo-Remembrancing; the careful positioning of uniformed service personnel at sports matches; and ardent poppy nationalism(Remembrance poppies worn and displayed on Remembrance Day).”

Arrayed against this mainstream celebration of “veteranhood” (and the universal “heroism” in uniform that always precedes it) is the small cohort of “critical veterans” championed by the author. Those interviewed by Glenton and profiled in his book remain engaged in various forms of left activism—BLM, the climate movement, renter’s unions and trade unions, the Northern Independence Party, Irish and anti-monarchical Republicanism, anti-fascism, and advocacy for Scottish independence. If nothing else, he concludes, they are helping to inform the left’s own “outsider perspectives on war, the military, and veterans” by dispelling harmful but popular myths about all three.

…

(Steve Early and Suzanne Gordon are co-authors of Our Veterans: Winners, Losers, Friends and Enemies on the New Terrain of Veterans Affairs (Duke University Press, July, 2022). They can be contacted at Lsupport @aol.com. For more information about the book, see ourvetsbook.com.)

The March Across the Shenandoah Valley

By Stewart Acuff

Part 1

Walking up yet another hill on the march across the Shenandoah Valley in a hailing rainstorm, organizer Clinton Wright asked: “How does this make sense, walking uphill toward the thunder?” laughing with the 20 or so soaked other marchers on the third morning of the walk.

The 23-mile, four day march the first week of April from civil rights sacred space, historic Harpers Ferry to de- industrialized struggling Martinsburg, West Virginia came from a request to Bishop William Barber that the Poor People’s Campaign join local folks in a protest against the toxic Rockwool factory polluting the valley.

Progressives and activists across West Virginia have been working intensely in our communities and with Bishop Barber and the Poor People’s Campaign pushing hard on WV Senator Joe Manchin for more than a year, since he locked himself down to prevent federal help for poor and low wage working West Virginia families.

As Manchin first blocked $15 minimum wage in Biden’s first Covid bill to his single-handed destruction of the child tax credit, to his determined defense of the racist filibuster killing voting rights, to his rejection of new union jobs building clean and green energy, West Virginians have become increasingly outraged.

We have rallied at Manchin’s offices, marched at the nation’s Capital, engaged in nonviolent civil disobedience and been arrested, sent letters and made phone calls , steadily escalating tactics in a real life and death fight for democracy, for workers and the poor and for the health of the Earth and her climate.

On a chilly, drizzling wet Tuesday morning April 5 Bishop Barber gathered 60–70 of us in front of the gates of Storer College, the history filled former college for Black students built right after the Civil War where Black scholar W.E.B. DuBois had brought the second meeting of the Niagara Movement while creating the NAACP; in the town where John Brown and his men tried to start a rebellion of the enslaved.

The presidents of both Jefferson County and Berkeley County NAACP joined the gathering with three local clergy, working families and environmental activists.

After the welcomes and prayers Bishop Barber with his disability and Rev. Dr. Liz Theoharis led the crowd down the hill, up Washington St. and out onto Highway 340 West toward Martinsburg and Joe Manchin’s office 23 miles away.

Much more to come.

Part Two

We walked five miles that first day all on the shoulder of federal highway 340, the highway that runs north-south on the bottom of the historic and beautiful Shenandoah Valley. I was amazed that first day and every day after at the strength and stamina, singing voice, chanting and positive perspective of Rev. Dr. Liz Theoharis. Radio host and longtime friend Rev. Mark Thompson walked the whole way with us that day and every day. Rev. Mark interviewed most of the folks who walked every day getting a wonderful down to the ground very real story of the march. Rain drizzled on us off and on during the day.

At the end of the day our support bus took us to back to our cars to sleep at home.

Wednesday was our hardest, longest day but very sweet for those of us who’ve been fighting for four years against a poisonous and toxic insulation factory owned by a global colonial corporation called Rockwool from Denmark. All day while we walked, we sang and chanted against Rockwool for seven and a half miles till we saw their filthy burnt carbon pouring from twin smokestacks smoking.

We marched into a rally against Rockwool timed to greet the march with more than a hundred residents of the WV Eastern Panhandle determined to shut down Rockwool. One by one local residents told of its negative health, environmental and economic effects……

And Rockwool’s ugly contribution to climate change.

Presbyterian minister Gusti Newquist prayed and spoke as did the veterinarian from the race track that drives much of the local economy, a pulmonary scientist from the National Institute of Health, mothers, a beekeeper and a couple farmers, education advocates warning of the dangers to kids at the elementary school only a half mile away.

When we went home toward dusk, we had taken another step toward saving our valley.

Part 3

It stormed off and, on all day, — a cold spring rainstorm or thunderstorm with thick, heavy rain, even hail.

And we kept walking, pausing only briefly under a bridge when the raining was its heaviest.

The most indefatigable of all the beginning to end marchers were the two strong women clergy leaders: Rev. Robin Tanner and Rev. Dr. Liz Theoharis, neither of whom wavered ever over the entire week. I got a close look at the extremely competent, kind and strategic staff and leadership of the Poor People’s Campaign. They were all extraordinary. And fun.

Rev. Dr. Liz led us in a brief service of prayer and reflections our fourth morning outside the Eastern Regional Jail where so many inside are victims of opioid pushing by big pharma and grinding poverty and Joe Manchin’s attacks on the poor.

Leaving the jail, we marched into Martinsburg with pride all the way to Courthouse Square, the middle of town in rural America where we leafletted about the Saturday rally.

We ended our March Across the Shenandoah Valley with a last mile march to Joe Manchin’s Martinsburg office Saturday morning where Bishop William Barber, nonviolent holy warrior for love and justice, charged Joe Manchin with his assault on the poor and low wage workers, on the economy and the environment. Then he lifted us up again with a vision of the future where the world is more just and our earth more healthy and our people more secure and life sweeter.

Stretching his massive hands and arms reaching out in solidarity, about 20 us with the Bishop roared out of Martinsburg to drive 200 miles across West Virginia mountains to the only power plant that burns the waste coal that Joe Manchin’s company sells. There near Fairmont we joined a demonstration of environmentalists at a plant gate in the rain still falling, our feet in the black mud of Joe Manchin’s filthy coal and heart.

We ended our week of walking across the Shenandoah Valley and challenging Manchin at the very place his corruption begins with an all souls worship service Sunday morning at the Manchin dirty power plant in reverence and protection of creation.

…

On June 18th there will be a gathering from all over the United States, for information on the “POOR On June 18th the “POOR PEOPLE’S AND LOW-WAGE WORKERS’ ASSEMBLY AND MORAL MARCH ON WASHINGTON AND TO THE POLLS” will gather from around the country, for more information click here.

Staten Island workers vote ‘yes’ for first Amazon union in U.S.

By Rand Wilson and Peter Olney

Against nearly impossible odds, the Amazon Labor Union (ALU) a new, independent union has won the first NLRB supervised, union certification election at an Amazon warehouse in the US.[1]

On Friday, April 1 (no April Fools these workers!) the vote count was 2,654 in favor of the union and 2,131 against at “JFK8,” Amazon’s Staten Island Fulfillment Center.

Several excellent accounts of the vote with interviews of the workers leading the campaign have already been published by Labor Notes[2] and Jacobin.[3] The New York Times also published an excellent article.[4]

Prior to the vote, there was plenty of skepticism about the campaign in the labor movement and among the pundits. With only a small organizing committee, no budget, and no experience up against management’s ferocious anti-union campaign, most predicted a lopsided vote against joining ALU.

What the winning vote makes clear — is that after the Covid pandemic — there is a much broader uprising occurring among workers. Starbucks baristas[5], gaming companies’ programmers[6], the New York Times digital team[7], etc. have all recently formed new unions. The current “union moment” is having a broad impact.

The win shows that when it comes to a company of the size and scale of Amazon, the typical organizing tactics and strategies may not apply. We need to have an eclectic approach, recognizing that there will be many successes and failures in a long-term effort to build a strong union at Amazon.

“Workers responded militantly to the company’s scare tactics and began supporting each other as if they already had a union in the workplace.”

At the same time that Staten Island workers’ ballots were being counted, the votes were being tallied for the NLRB ordered re-run election at Amazon’s huge Fulfillment Center in Bessemer, Alabama. The outcome looks less promising there: support for the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU) union fell short: 993 ‘No’ votes to 875 ‘Yes’ votes. Nevertheless, the union did much better on the second attempt — and there are 416 challenged ballots which makes the final result still uncertain.[8]

There is one obvious difference between Staten Island and Bessemer Alabama: the high concentration of union members in the New York metropolitan area (6% in Alabama, 20% in New York state).[9]Higher union density leads to a positive “word of mouth” message about unions in working class households that is far more convincing than any leaflet or ad. The organizers of ALU also broke out of traditional organizing approaches. Workers responded militantly to the company’s scare tactics and began supporting each other as if they already had a union in the workplace.

The Staten Island vote supports what some union organizers call the “metro strategy.”[10] Amazon facilities are highly concentrated in metropolitan areas like New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles where there is broader support for unions. In these areas, besides having giant fulfillment centers like the one on Staten Island, there are also dozens of “last mile” delivery stations with a smaller workforce. Coordinated actions at the delivery stations in just a few cities with a pro-union environment could have a huge ripple effect.

Undoubtedly Amazon will use every legal maneuver possible to avoid ALU being certified as the exclusive bargaining representative for the Staten Island workers. Management will likely file objections to conduct of the election with the NLRB seeking to have the vote reversed. And now the antiunion pressure will be even stronger for the upcoming union vote at LDJ5, a nearby Amazon sort facility where workers will vote between April 25- 29.

Conducting bargaining as “theater”

Assuming the ALU survives the legal obstacles to certification, all eyes will turn toward the process of negotiating a first collective bargaining agreement for the Staten Island workers. Traditionally bargaining is a button-down legal process with long arduous table talk and legal maneuvering.

Hopefully ALU will recognize that its negotiations for the Staten Island facilities will take place in a fishbowl: the Amazon workforce and the entire labor movement will be watching! That environment necessitates breaking out of the traditional legal straight jacket and conducting bargaining as “theater”– heralding the cause of justice for Amazon workers to the entire New York metro community, the broader labor movement, and Amazon’s customers.

United Parcel Service (UPS) and the U.S. Postal Service (USPS) are Amazon’s closest competitors. Amazon’s business model of super-labor-exploitation poses an existential threat to both the Teamsters and the postal workers’ unions. Similarly, its acquisition of Whole Foods threatens standards at UFCW organized supermarkets.[11]

These more established unions have already been quietly organizing at other Amazon facilities. Will they have the humility to learn the lessons from ALU’s approach? The initial signs are positive: After the election results were announced, Teamsters newly-elected president Sean O’Brian said, “I commend anybody who tries to take on a schoolyard bully like Amazon.”[12]

Postal Workers union president Mark Dimondstein proposed that, “The organized labor movement should unite and build a multi-union crusade to help organize Amazon workers throughout the country.” Dimondstein further stated that his union is, “Ready to assist the newly organized workers at Staten Island in any way we can in the coming and challenging battle to win a good first union contract.”[13] Let’s hope that other unions and the entire labor movement will adopt a similar ecumenical and class solidarity approach!

…

[1] Amazon Labor Union, https://www.amazonlaborunion.org/