Gentrification, Homelessness and Elections: When Does a Difference Make a Difference?

By Kurt Stand

The primary elections in Washington, DC and Maryland are over. For many of the down ballot local races in the District, and neighboring Prince George’s and Montgomery counties, that means the outcome is known, given the predominance of one-party rule in much of our area. At the time of writing, the results are a mixed bag. Some genuinely committed activists for social justice, including DSA members, were elected, and there is now a possibility that some too long-delayed social reforms and protections may be enacted in suburban Maryland. Yet institutional barriers blocking those who would challenge existing power remain high. Moreover, more than a few of those elected are content to let business as usual remain unchanged — for even in relatively liberal communities, in which public officials say all the right things, the gap between words and deeds is enormous and too many people go tumbling down that gap. Co-governance, a form of collaborative engagement in which elected officials meet and work with community groups before and after an election campaign, offers one possible way to overcome that reality.

Nonetheless, for many people in and around our nation’s capital and for millions across the country, elections don’t seem to carry much meaning. That is true of federal races, even in today’s polarized political climate, where candidates spew promises unlikely to be fulfilled, appearing, and disappearing like actors on a stage. And this is true on the local level where even office holders who live within shouting distance too often seem uninformed regarding intimate questions of food, transportation, school, jobs, health, public safety, and prices. In both cases, such attitudes reflect an eroding of political democracy that lies in the background of our eroding rights. Withdrawing from electoral activity is no answer; but if we fail to understand why so many feel ready to do just that, if we fail to understand that such attitudes are rooted in experience, we will be unable to preserve existing rights – let alone build a transformative politics rooted in alternative power.

Glancing through the July issue of Street Sense – a newspaper of, by and for the unhoused – one can read multiple reflections on the reality of powerlessness in the face of official hostility. In the aptly titled article “Breaking up encampments is worse in the summer heat,” writer Amina Washington, herself homeless, details the DC government’s practice of destroying shelters set up by those without other housing. Washington makes the simple point that those in power choose to evade: “It is unfair to target homeless people and jail them for trying to survive. Sleeping outside should not be a crime.”

Also in the issue, in an article headlined “Watchdog group finds profits soaring for real estate company facing several lawsuits,” Holly Rusch touches on the reason behind the cruelty in police destruction of encampments: realtors profit by raising rents to a level that few can afford, facing no accountability for legal violations they commit enroute to making even more money. So it is that the rich become richer, no matter what the law says. Unstated is that the poor are unwanted in neighborhoods in which they once lived because, much like unkempt lawns, they might lower the value of overvalued properties. Criminalization of homelessness is simply the reverse side of the gentrification coin.

These articles are reporting on realities that have a multi-year lineage – go back to any past issue of Street Sense DC (and editions of Street Sense in other cities across the country) and similar themes of officially sanctioned police repression and unsanctioned landlord profiteering recur with depressing regularity. Washington’s Mayor Muriel Bowser falls into a long line of those in government who pretend concern for those without, shelter yet implement policies that seek a solution by pushing the unhoused out of sight, rather than housing them. The fact that she was an avid supporter in 2020 of Michael Bloomberg – real estate and news magnate, one-time Republican turned anti-Trump but pro-gentrification Democrat – in his presidential primary campaign reflects the deep-rootedness of the problem.

The paper does try to give readers hope, and so there are articles about hearings and investigations that purport to be looking for solutions. These, too, have an air of familiarity to them, for the problem of lack of housing, of lack of services, of lack of health care, of lack of well-paying jobs, of a lack of government accountability to the overall community which it allegedly serves and in whose interest it allegedly acts, are “problems” endlessly discussed, studied, analyzed, legislated for, and yet ever unresolved. Street Sense’s community speaks with more honesty in poems and bits of autobiographical writing that seek meaning in personal relationships or spirituality – graspable in a way our political system should be but is not.

That is the challenge which newly elected or re-elected public officials now face: how to act in ways that become meaningful for those whose needs are greatest; how to bring about reforms that challenge existing injustice; how to rearrange the current power structure into one that is more fair and sustainable. In both DC and in Maryland, progressive legislation around hours, wages, sick leave for workers and police accountability have all passed in recent years. These matter enormously. Yet the fact remains that for far too many, words on pages have not translated into a difference in conditions of life.

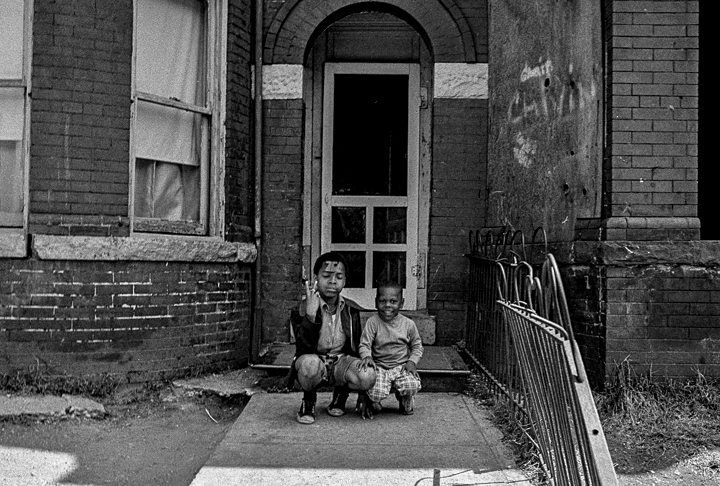

PHoto of young boys on stope 3 blocks from the Capital, 1972 now an area with high property values and well to do residents

That gap is not only experienced by those of us with the least. Renters, homeowners, working people doing better, people defined as “middle class” (in all that term’s ambiguity) continually find themselves navigating changes in the quality of their lives due to fluctuations in the housing market without any meaningful say in the process. Living in a neighborhood that forms part of a community is valuable in and of itself, something most people desire, but it is not a value that market forces put on property. A home that becomes an asset to be flipped loses an intangible quality of what “home” could be.

Unwanted change as a fact of life came through in a performance of Green Machine at Capital Fringe Festival earlier this month (an annual independent theatre program back after two Covid-canceled seasons). Written by Jim McNeill and directed by Catherine Aselford, the one-act play gives voice and dimension to the lived reality of a neighborhood in transition and the accompanying lost sense of community that arrives when real estate interests “improve” an area by raising home prices beyond the beyond. Gentrification is a fancy name for that process; another word for it might be displacement, as those who can’t afford simply “disappear” — forced out of their homes, forced to start over again, moving in with family or winding up on the streets. Other losses occur too, less tangible yet no less real – and such losses are those to which the play’s characters give voice.

Set in D.C.’s Mt. Pleasant neighborhood – a community which had its own vibe as a mixed black, white Central American community with more street life than is commonly found in our nation’s capital. The play is rife with references that speak to an understanding of what was as well as what is, as it depicts a community where a house originally purchased for tens of thousands of dollars might now be worth millions. Upward prices increase the push-pull of high turnover – whether selling is designed to cash in before a price fall, or forced as rising taxes, interest rates, insurance make what has long been home, unaffordable. Winds of change for homeowners hit tenants with gale-like force as their rents and rights are ever less protected. In the process, the vibrancy of what had been disappears. Wealth comes attached with its own bland uniformity and multiple layers of segregation – be it by race, income, age – ultimately enforcing complete homogeneity of lifestyle, as what is or is not “acceptable” narrows.

Those details are implied in Green Machine, which focuses on how longtime residents try to make sense of what has happened to their lives, to the world they lived in. A community where people knew each other, where someone would feel safe enough to lend a stranger a helping hand, where neighbors befriended multiple generations of a family, somehow vanished without any single event marking the beginning (or end) of the transition.

Breathing life into this narrative is that every time someone spins too rosy a picture of the past, someone else brings back a moment of reality with a reminder that it wasn’t just about peace and love, that crime existed, that money mattered. However, problems were community problems. They weren’t brushed aside, ignored or dealt with by moving out or forcing “undesirables” away.

Green Machine‘s plot revolves around the opening of a marijuana dispensary – of questionable legality in the here and now as only regulated medical marijuana dispensaries are currently permitted – aiming to cash in on the possibilities of the likely soon-to-come full legalization without abandoning the sense of trust that was part of the bygone counterculture. Those illusions, too, are shattered: we can’t go back to all the past, all the more so because that alternative culture was itself never able to overcome either the pull of market forces nor the social dysfunction that lies just beneath the surface of our lives. The thin line between drugs as a means of social connection and drugs as a force of destruction is not glossed over, as the fate of ungentrified neighborhoods left behind are noted in the play as a reminder of other, deeper losses. Yet, failure doesn’t deny the fact of what was: the vibrancy, the sense of possibility around which neighbors tried to build a life was real and was lost when neighbors become strangers. One character recalls falling down drunk on a winter’s night and how a neighbor whom he didn’t know took him in, an example of trust in a stranger who was thereafter no longer a stranger. Even when characters differ in memory they share memories of people over time, people without anything else in common but whom they knew because of the community that existed.

The play never loses sight that while property values have gone up, the change that came was for the worse – as notes included on the playbill back up:

In 1968, following the violence that erupted in response to the assassination of Martin Luther King, white flight led to Mt. Pleasant becoming a majority black neighborhood. 1980s;

a large influx of immigrants from El Salvador and other Central American countries creates its own beauty, widening the cultural contours of each block, as well as bringing new tensions that burst forth in street violence in response to a 1991 police shooting;

the millennium, housing prices went up, community diversity went down. The 2010 Census uncovered the fact that the Mt. Pleasant/Colombia Heights/Park View zip code ranked amongst the 25 most “whitened” in the country;

and by 2020’s zip code, the black population had fallen to 12%, the white population, now the majority, risen to 52%;

overall – and the raw fact behind these changes – the Playbill notes that a friend of the playwright purchased a home in Mt. Pleasant in 1972 for $22,000 – today the same home is assessed at $1.2 million.

All those numbers don’t tell what the play recounts: that for about three decades a thriving community was built in Mt. Pleasant. Now take those numbers and look at the unhoused, look at the reality facing residents of Congress Heights, of Deanwood or other left-behind neighborhoods in DC where jobs are scarce, social services few, housing dilapidated and violence all too common – or look at the similar disparities in Prince George’s and Montgomery Counties – and a picture emerges of few winners and more losers, of a preponderance of insecurity whatever one’s income, an insecurity made exponentially worse when it is wrapped within a life of poverty.

No one voted for this change – it just “happened.” Or rather, the cash ballot has more heft than the one in the voting booth. Changes brought about by market forces never just happen; public policy set in motion by specific legislation creates or inhibits the cycles of boom and bust that mark our lives, leading to the monetization of all aspects of life that hover around the characters in Green Machine and the vendors selling Street Sense.

Unions, community associations, churches, social justice groups, and socialist and other left-wing organizations exist in Mt. Pleasant as they do more broadly in DC and suburban Maryland. Many were aware of encroaching gentrification and displacement, and tried to push for an alternative. Yet these organizations were too small, too weak to have the needed impact. Or perhaps, better put, they had not been sufficiently integrated into the daily life of the communities within which they work and thus were (and are) relatively powerless. This is a problem for local officials as well –the most principled elected social justice advocate in the world will lack effectiveness if their work is not intimately linked with grassroots organizations that are themselves part of popular daily life.

This is the challenge we face now. Elections matter – legislative and political alternatives can redirect society, reveal conscious choices that lay hidden when the “market” is blamed for the consequences of a system built on greed. Moreover, all we need do is look across the Potomac and see the Republican sweep in Virginia last year to understand that complacency jeopardizes the rights we so urgently need to make life better for all. If we turn back to the 1990s (the midway point in the sweep of time that forms Green Machine’s characters’ understanding of the world), we can see the cost when we are unable to resolve community pain in a human and humane fashion.

That was the time of the crack epidemic and inner-city destruction in our area and across the country. This also marked the Reagan-era devastation of the gains made by civil rights and liberation movement struggles and laid the groundwork for the wave of gentrification and displacement we now experience. After all, the economics of profiteering goes hand-in-hand with the racism that makes it so easy for some to talk of “neighborhood improvement” that drives out those who would most want and need the benefits of the promised change – just as it makes it easy to see the unhoused as a problem to be removed from sight rather than as people with problems that need to be resolved. Writing in 1991, Clarence Lusane took note of connections we still need to make:

“A radical redistribution of wealth and an examination of the prejudices of the capitalist economic system must be at the core of a movement led by people of color and working people for fundamental economic reform. … While economic parity alone will not end either individual or institutional racism, it is the foundation upon which to build the movement for an egalitarian society. None of these suggestions are remotely possible without increased economic and political power on the part of those most dispossessed in our society, particularly communities of color. … Strategies for increased and responsive political power and economic development must come from those communities most in need.”

(Pipe Dream Blues: Racism & the War on Drugs, South End Press, Boston, 1991, p. 220).

Despite often heroic and determined efforts, popular movements in the 1990s were unable to realize such power. So the initiative passed to the hands of those who found a source of wealth in others’ poverty – money making money by undermining community, by devaluating neighborhoods, by raising the cost of housing, thereby destroying the sense of home so crucial to us as human beings. How that can be made different is the dilemma posed by Green Machine, is the moral imperative that cries out from the pages of Street Sense, and is the challenge elected officials face today, as violent assaults on democratic rights in any form loom as a direct threat.

Co-governance, as noted, is one way to create a social justice alternative to the lobbyists who push forward the notion that only incremental change is possible, incremental change only permitted when accompanied by giveaways to those who already have too much. It is a way to ground politics that can build the change people need by creating wider bonds of unity (such as between homeowners and the homeless) rather than new divisions. It is up to us to build organizations of all those impacted, organizations that are part of the fabric of life. It is up to us to create a political culture connected to the rhythms of life, to ensure that we can and do use and expand our rights. It is up to us to create the communities we long for, rather than those imposed by the logic of the dollar. Only if we do so will we find an escape from the atomized, displaced existence that continues to threaten us today.

…

Lessons of 1998: The Fight to Defeat Prop 226

By Peter Olney

As the 2022 midterms near, there is increasing optimism about our ability to stem the white supremacist fascist tide and hold the House of Representatives and increase Democratic margins in the Senate. The vote on abortion in Kansas should give us all heart and cause us to recommit to doing the work of knocking on doors and getting out our vote. Recently I interviewed David Sickler retired Southern California Director of the State Building Trades Council and long time AFL-CIO Western Regional Director. Dave is a working class organizer and a hero and mentor to many.

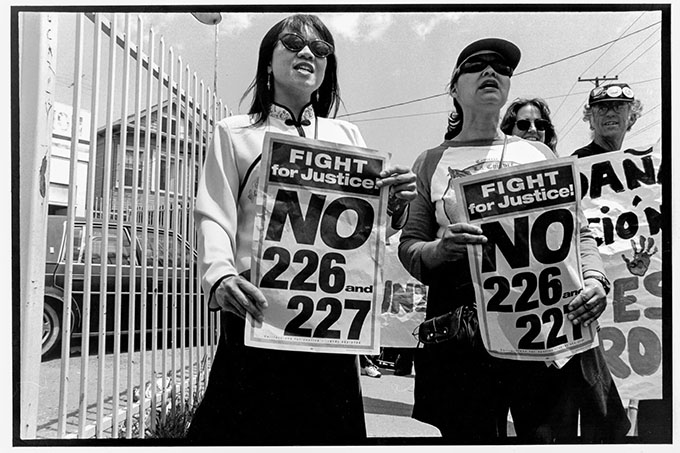

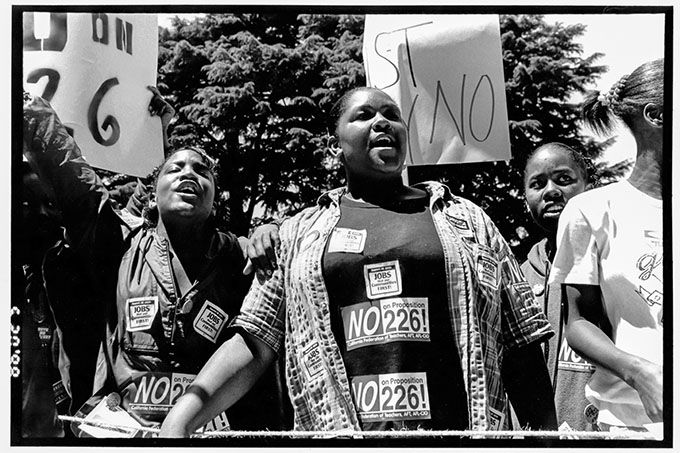

I wanted to learn from the lessons of defeating Proposition 226, the so-called “Paycheck Protection Act” placed on the California Ballot in 1998. I sat down with Dave Sickler.

Q: What was Prop 226? What would it have done to labor and who was behind it?

Sickler: On June 2nd, 1998 Prop. 226 was promoted as the “Paycheck Protection” initiative by the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) an extreme right wing national organization created and backed by the US Chamber of Commerce, National Association of Manufacturers, Koch Industries, Grover Norquist, California Governor, Pete Wilson and other wealthy donors. 226 in California was supposed to be the model for the nation. Grover Norquist said if it passed in California it will pass in every other state in the nation and will reduce labors strength by 80%. Prop. 226 was promoted as a benefit to union members because it required unions to get the approval of union members to spend union money on political campaigns. Unions would have to contact every single union member every year and have them sign a form agreeing to have union money for every campaign and issue facing union members. The goal was to cripple labor’s ability to protect itself by raising money to fight back. The Economic Policy Institute said because of the measure’s excessive and onerous bureaucratic roadblocks it would seriously hamper Union leadership’s ability to protect its members.

Q: What were the polls saying? What was some of Labor saying?

Sickler: Polls showed 226 to be very popular with rank and file union members by 76%. Many labor leaders threw up their hands and said they wouldn’t even waste money fighting it. We in the Building Trades had been fighting Governor Pete Wilson over the prevailing wage issue and his attack on the 8 hr day for a long time, and we were totally against giving him a free pass on #226. We knew we could beat him and his right wing cronies.

Q: What did you do to turn things around?

Sickler: What I did was to meet with Miguel Contreras Executive Secretary of the LA County Federation of Labor who told me the County Fed. would not fight 226 because most of the affiliates were not going fight it, and many attorneys said it would pass no matter what we did, and we would just piss off the membership. I told Miguel that I knew we could beat 226 and I asked him to support me, and I would at least build him an army. I told him I needed office space and supplies, and I told him I wanted to speak at every delegates’ meeting because I wanted to be invited to every union meeting in Los Angeles County. I knew if I could go one on one with every union member I could convince them that 226 was a direct assault on them.

Q: How did those meetings go?

Sickler: I ended up attending a total of 111 meetings. I also met with many community organizations. What I said to union members was that 226 sounds very attractive and reasonable when you first hear about it or even read it, but the closer you look into it you discover the people behind it don’t care about your paycheck. As a matter of fact they all have a track record of attacking your paycheck. Let’s just look first at Governor Pete Wilson. He had a history of trying to eliminate prevailing wages for construction workers and had just finished trying to eliminate the 8 hr. Day. At every meeting I went to I brought a sign up sheet for volunteers to phone bank and walk precincts. Of course I got permission from the officers to solicit volunteers. The response from the rank and file members was fantastic and once the officers saw the reaction they got excited too and jumped on board. This might sound crazy, but I didn’t encounter a single union member in those meetings who argued with me or said they were supporting 226.

Q: What was the result?

Sickler: We won! We overcame the two-to-one polling in favor of the measure winning the state by 53 to 47 percent. In Los Angeles County we won by 63%. The victory over 226 was hailed as a modern political miracle. I disagree! It wasn’t a miracle. It was union members seeing through the bullshit and fighting back and knowing they could win! The lesson here is you can’t win a fight if you don’t fight.

Q: What are the lessons from 226 going into these critical 2022 congressional midterms. Sickler: The lesson we learned from 226 was that you don’t let fear cripple your will to fight back. In the beginning many labor leaders were paralyzed by fear and believed that there was no way we could win so they didn’t even want to try to fight back. When I met with rank and file members and showed them who their enemies were, and what they trying to do to their union, they got very angry and wanted to fight back. We took that anger and channeled it into a positive, mighty and exciting campaign, and we beat the bastards

…

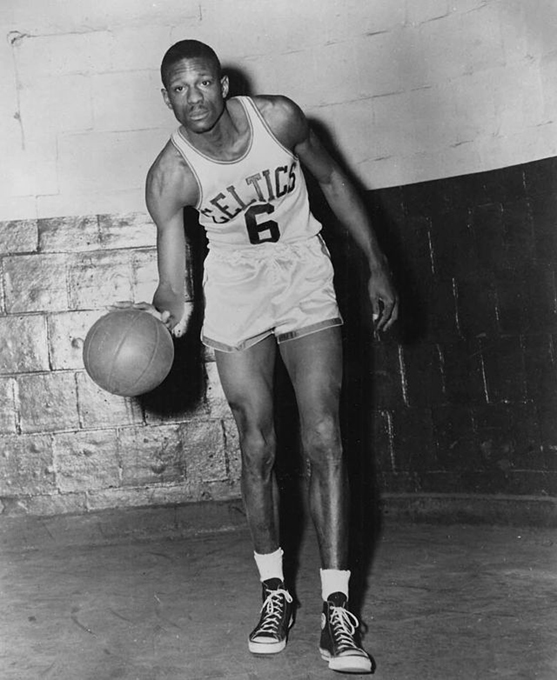

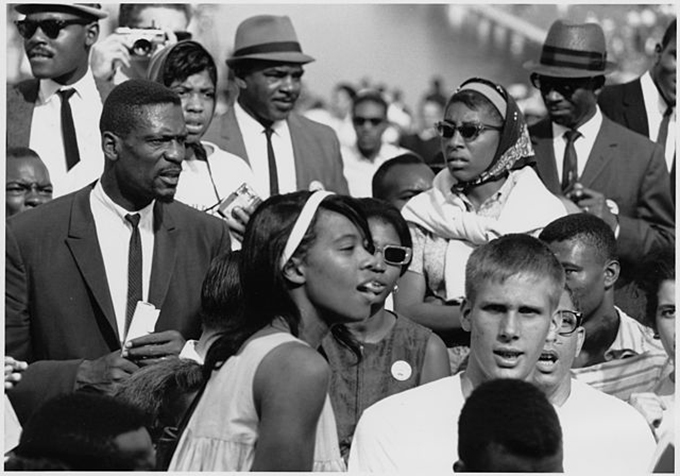

Bill Russell, “played for the Celtics not for Boston.”

By Jay McManus

No one, especially basketball fans, in the Boston area could escape the shadow of Bill Russell and his Celtics in the 1960’s. He and his teams were so good that it was news only when they lost. That greatness has been acknowledged non-stop since Russell’s recent death, but it is still very difficult, even for us Bostonians who lived through them, not to be amazed by his core accomplishments: eleven NBA championships in thirteen years, including eight in a row. Russell was, unmistakably, at the heart of the engine for the Celts, just as he was at the University of San Francisco, where he won two national titles, and on the 1956 gold medal-winning US Olympic team.

He revolutionized the NBA. In stark contrast to today’s play, Russell emphasized defense, leading schemes that were near impenetrable and utilizing a style that epitomized teamwork and selflessness. It’s arguable that no athlete ever, in any sport anywhere, has subjugated his supreme skills for the good of his team like Bill Russell did. Personal accomplishments and glory meant nothing to him. That Russell was able to add to such an incredible legacy by winning two championships as a player-coach—a role virtually unheard of at the professional level of any sport worldwide before or since—underscores the singular talent, intelligence, and commitment of the man.

Many in Boston ignored it all. Despite their historic run, the Celtics often played before a half empty Garden; even the playoffs didn’t guarantee sellouts. No parades, player endorsements, and public clamor awaited these champions. Instead, as another Boston legend, Bob Cousy, put it, a “nice dinner” capped their winning seasons. Meanwhile, their hockey counterparts in Boston, the Bruins, were celebrated by locals notwithstanding their history of losing.

It was difficult back then, as it is now, to believe that race was not the primary reason for the seeming indifference exhibited by Bostonians toward the Celtics. The team was the first in the NBA to start five Black players. Russell was one of the first Black men to play, or certainly star, in the league, and he was later the first to assume the role of head coach for a major professional sports franchise. He also freely expressed his views about the unwelcoming atmosphere in which he and his Black teammates were forced to work.

Russell considered Boston to be one of the most segregated cities in the country, famously referring to it at one point as a “flea market” of racism. On numerous occasions he and his family suffered personal indignities because of their skin color. What ensued in the city only a few years after his retirement in 1969—Black children in school buses being stoned in white neighborhoods, white politicians spewing racist hate, Alabama’s segregationist Governor George Wallace finding a welcome in parts of the city, among other damning indicators—proved his point. It also helps explain another famous sentiment of his that he “played for the Celtics not for Boston.”

That honesty from Russell, his willingness to speak truth to power, led to his assuming a leadership role in our country’s fight for racial justice. Along with several prominent athletes and entertainers he was—at no small risk to his life and career–part of many of the US civil rights movement’s seminal protests throughout the sixties. The man’s integrity and courage, particularly at such a tumultuous time in our nation’s history, were alone worthy of acknowledgement and formal recognition.

Yet, those achievements, like his historic Celtics run, were also largely ignored, if not clearly resented, by many in Boston including, apparently, its power brokers. More than four decades went by before the city gave serious consideration to paying public tribute to the man, and even then it was only at the urging of then-President Obama who, after awarding Russell the Presidential Medal of Honor in 2011, expressed his wish that “one day, in the streets of Boston, children will look up at a statue built not only to Bill Russell the player but Bill Russell the man.”

It’s not as though Boston didn’t have opportunities to pay proper respect to a civil rights champion who also happened to be professional sports’ greatest ever winner. Years before Obama prodded the city, other Boston sports luminaries, all white if keeping score, had gotten their due with sculptures or equivalent tributes. One of them, Red Sox great, Ted Williams (for the record, no championships in his career), had a major tunnel running through the city named for him in 1995, prompting Russell’s late Celtic teammate, Tom Heinsohn, to offer his own unique take on the disrespect accorded by the city to his friend: “Look all I know is the guy won two NCAA championships, 50-some college games in a row, the ’56 Olympics, then he came to Boston and won 11 championships in 13 years and they named a fucking tunnel after Ted Williams!”

A statue of Bruins great, Bobby Orr, was erected in 2010 in front of TD North Garden, the home of the Celtics. In addition to his tunnel, Ted Williams had a sculpture in his honor placed in front of Fenway Park in 2004. Russell’s coach, Red Auerbach, was memorialized in 1985 with a statue at Faneuil Hall. Scores of other notable Boston athletes, from Harry Agganis to Doug Flutie, Larry Bird, and Rocky Marciano, have had their achievements commemorated through statues, or even had arenas named after them. No doubt there will be a likeness of Patriots quarterback Tom Brady soon gracing the front of Foxboro Stadium.

Boston’s monument to Bill Russell, by far the most accomplished and consequential icon of them all, erected at last in 2013, is found off to the side of Government Center Plaza, hardly a hub of activity for people in the city, and especially for tourists; blink and you’d miss the statue. The setting does not befit an athlete and man of Russell’s stature. Worse, it fuels the lingering perception, if not reality, that in Boston only our white sports heroes are deemed worthy of true honor.

Bob Ryan, a long-time sports columnist, and former Celtics beat writer for the Boston Globe recently penned a tribute to Bill Russell in which he cited the varied, and incomparable, contributions he made to the city of Boston. Ryan ended his piece with this question: “Did we deserve him”? For many of us Bostonians the answer, sadly, is self-evident.

…

Pro-Israel Lobby Drops Millions to Influence US Congressional Elections

By Larry Hendel

One of the most closely watched races in the May primary cycle pitted Texas conservative Democrat incumbent Henry Cuellar against progressive challenger Jessica Cisneros, an immigration attorney. Cuellar, an eighteen-year incumbent, is terrible on the environment, labor rights and immigration, and the only remaining House Democrat to oppose abortion rights. Cisneros almost beat Cuellar when she ran against him in 2020. In this year’s rematch, Cisneros came up 289 votes short. Cuellar squeaked by with 50.32% of the vote .

Were it not for major infusions of cash from outside organizations, Cuellar would undoubtedly have lost. One such group was AIPAC, the American Israel Public Affairs Committee. This decades-old, Jewish organization has been the primary force in Washington when it comes to pro-Israel lobbying. But this year, for the first time, the organization formally involved itself in the electoral arena, contributing to endorsed candidates and participating heavily in independent expenditure campaigns. According to AIPAC spokesperson Marshall Whittmann their mission is simple: “We are engaged in the democratic process to elect candidates who will support the U.S.-Israel relationship and oppose those who will not.” In other words, they won’t be looking at candidates’ views on the economy, race relations, guns, abortion, the environment, or any other issue important to American voters. Only Israel. This could be devastating for progressives running for office.

Last May, AIPAC, along with its sister political action committees (PACs) the United Democracy Project (UCD) and the Democratic Majority for Israel (DMFI), spent over $10 million on five Democratic party primary races. (For the purpose of this article, I will use “AIPAC” to represent all three PAC’s, since they are definitely partners in crime.) This equates to $2 plus million per election. Besides the Cuellar-Cisneros race, AIPAC was involved in two primaries in North Carolina, one in Ohio and one in Pennsylvania. Their candidate won in four out of the five. Until this cycle, AIPAC didn’t have a super PAC. Now, with millions in contributions from both Democratic and Republican multi-millionaires, it’s on pace to become one of the most influential political funders in the country.

In the Ohio race, Nina Turner, a close ally of Bernie Sanders, was ahead in the polls for most of the campaign. But in the final lap her opponent’s allies bombarded the airwaves with hit pieces. AIPAC was the leading spender, dropping $1.5 million. Turner eventually lost by a two to one margin. The AIPAC money wasn’t the only reason she lost, but it made a huge difference.

As they do in many cases, AIPAC did not make support or non-support of Israel a major topic in the campaign. Often AIPAC prefers their signature issue to remain in the background, so there are fewer fingerprints. In this case they hit Turner by saying she wasn’t a “true” Democrat.

On July 19, AIPAC dropped $6 million to help Glen Ivey beat Donna Edwards in the Maryland’s fourth Congressional District Democratic Primary 52% to 35%. And on August 1, AIPAC invested $4 million in Michigan to successfully defeat Andy Levin’s efforts to stay in Congress. Levin, a Jew, a former synagogue president and a former union organizer, supports the concept of a Jewish state in Israel but is unabashedly in favor of Palestinian rights. AIPAC backed a more pro-Israel candidate, Haley Stevens. Stevens won with 60% of the vote.

AIPAC is not just dabbling. They intend to be players in electoral politics, and they bring major money to the table.

AIPAC’s foray into the campaign world is bad for progressives in three major ways.

First, in general elections, if there is a Republican who is more pro-Israel than the Democratic candidate, whether that candidate is a “progressive” or “moderate” Democrat, AIPAC is likely to back the Republican, probably with major dollars. Whatever we think of the weaknesses of the mainstream Democrats, if we don’t keep a Democratic majority in Congress, this country will move to the right at an even faster clip. AIPAC has already endorsed 37 incumbent Republicans who would not vote to certify Biden’s election, including notorious Trumpers Jim Jordan from Ohio and Scott Perry from Pennsylvania. Perry, by the way, is the Congressman who recently compared the Democrats to Nazis. Apparently the organization is more concerned about Israel’s financial and military wellbeing than with the future of democracy in the United States. This “my way or the highway” approach to politics is about as self-centered and opportunist as one can get, and it’s frightening that AIPAC is creating a situation where our elections will be heavily influenced by people acting, in essence, as agents of a foreign country.

Second, within the Democratic Party, AIPAC’s willingness to pour millions into elections based on the single issue of support for Israel will force progressives to make a choice: support Palestinian rights and risk AIPAC’s wrath, or fight for what they believe in. This will make it harder for progressives, and if the progressive wing of the party doesn’t grow, and there is no left-wing opposition to the Pelosi/Schumer middle of the road approach to politics, we will probably never get, national healthcare, reduced militarism, requisite environmental legislation and other critical reforms. We need Democrats to expand their majority, and we need progressive Democrats to gain power within the party. It’s a both/and situation, not an either/or, and AIPAC’s involvement will make both more difficult to achieve.

Third, if AIPAC’s efforts are successful, the US will be spending even more resources strengthening Israel, an apartheid state that started out as a settler colonial land grab in 1948 and has been grabbing more land every year since. Occupied Palestine is the only area in the world in which millions of civilians have lived for over 50 years both without a state and without citizenship of any country.Palestinian villages are routinely destroyed, houses demolished, and people jailed without due process or probable cause. Close to 700,000 Israeli settlers have illegally established what they view as permanent communities on Palestinian territory, and often attack and terrorize nearby Palestinian villages. Israel possesses state of the art military technology, including nuclear weapons, and has become a dangerous, aggressive, nationalist state. There is insufficient opportunity here to get into details about the history of Israel, its degrading and oppressive treatment of the Palestinians, and its toxic, race based, hierarchical, anti-democratic view of human society. But I recommend the following books: The Hundred Years War on Palestine, by Rashid Khalidi and Understanding the Palestinian Israeli Conflict: a Primer, by Phyllis Bennis.

How Israel has swallowed up Palestinian land since 1947

So why is AIPAC jumping into electoral politics now when it never did before?

In a nutshell, AIPAC sees the “special relationship” between the US and Israel being threatened by the growing American support for the people of Palestine, and it is playing offense in an attempt to reverse that trend.

First let’s talk about that “special” relationship, and then let’s talk about the growing support for Palestine in the US.

After World War II, creating a Jewish state in the Middle East relieved the US of accepting hundreds of thousands of Jewish refugees from post war Europe and provided a western outpost in the Arab world, something the British and the Americans had wanted for decades. On May 15, 1948, the western powers “gave” historical Palestine to the Jews. Immediately armed Israelis attacked Palestinian towns and villages and 720,000 Palestinians, or 85% of the Palestinian population were forcibly expelled from their homes or forced to flee to avoid being attacked.

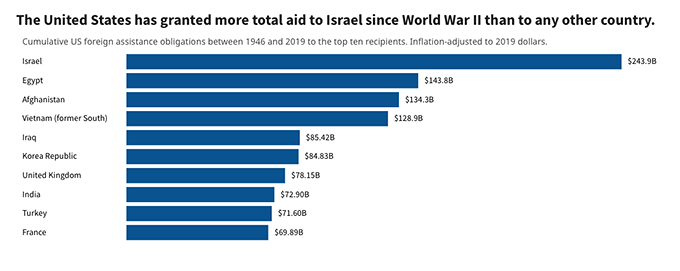

Since World War II, the US has been Israel’s most fervent supporter. From that time until now the US has given Israel $244 billion in military and economic aid, in inflation-adjusted dollars, making Israel the largest cumulative recipient of US assistance by far in that time frame.

Today Israel receives $3.3 billion annually in foreign military financing from the US. Earlier this year, our government decided that wasn’t enough and gave Israel an extra $1 billion to replenish their “Iron Dome” anti-missile defense system. The two countries continue to conduct joint military training and coordination.

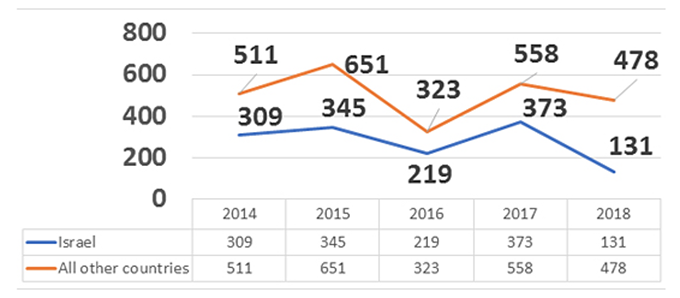

Washington politicians seem to love all this. There are more congressional junkets to Israel than any other country, by far, most of them paid for by the American Israel Education Foundation, an AIPAC affiliate. The percentage of trips made to Israel exceeded any other foreign destination. House members made nearly 1,400 trips to Israel, while total subsidized visits to foreign countries other than Israel were 2,500. See chart below from the Arab-American, July 7, 2022.

Of the 3900 privately funded Congressional visits to foreign countries between 2014 and 2018, nearly one third were to Israel. This past February twenty-seven Democrats and fourteen Republicansvisited Israel.

Under Trump, the Republicans embraced Israel like a long-lost brother. Traditionally American support for Israel has stemmed from the Jewish community, but over the last few decades, white evangelicals have made Israeli domination over the Palestinians a major objective for the Republican party.

But the tide of public opinion is starting to turn.

Over the last few years, young Jews and young evangelicals have been backing away from Israel and towards the Palestinians. A poll of American Jewish voters revealed that a quarter of them now agree that Israel is an apartheid state – a number that shoots up to thirty-eight percent among those under age forty. Twenty-two percent of Jewish voters overall agree that Israel is committing genocide against Palestinians, a figure that rises to an astonishing thirty-three percent among the younger group.

In the evangelical community we see the same trend. Among evangelicals between the ages of eighteen and twenty-nine, rates of support for Israel have fallen from 69% to 33.6%!

The primary reason for this change is, of course, the steadfast organizing efforts of Palestinians, in the United States and internationally. Publicity around the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS)campaign, launched in Palestine, has provided an excellent vehicle for explaining Israeli apartheid to an American audience. True, it has engendered a backlash, but the backlash just heightens the contradiction and keeps the issue on the front burner. The movement for Palestinian rights in the US has taken hold on college campuses, particularly under the leadership of Students for Justice in Palestine. Inspired by Palestinian resistance, progressives have organized in non-evangelical churches, such as the Presbyterians and Baptists, and many church groups now condemn Israeli apartheid.Over the last fifteen years more communities of color have been won over to the Palestinian cause. Palestinian flags were displayed at many Black Lives Matter demonstrations and at Standing Rock. George Floyd’s image can be seen throughout Palestine. Activists have been stressing similarities between settler colonialist conquest in Israel and in the United States, exposing Israel’s lie that it is a democracy. Also, media coverage of Israel’s brazen brutality and arrogance towards the Palestinians is changing somewhat. Coverage is still very biased towards Israel, but the Palestinian side of the storyis beginning to creep through. The raw footage of the bombing of Gaza, the house and village demolitions, the military intrusions into the Al Aqsa Mosque, and most recently the murder of Palestinian-American journalist Shireen Abu Akleh are enough to make any honest person realize that Israel is an occupying power and is doing terrible things to the Palestinians. The attack by the Israeli military at Abu Akleh’s funeral made the whole world gasp.

This brings us back to Congress and why, after all these years, AIPAC wants to start investing in electoral politics. For the first time, there are now people in Congress willing to speak out against Israel’s oppression of the Palestinian people, and they are getting some traction. At this time, it’s a small group: The Squad, Bernie Sanders, and several dozen others, depending on the issue. But it’s growing. Minnesota Congressperson Betty McCallum has thirty-two cosponsors on her bill prohibiting the use of US funds for unlawful detentions of Palestinian minors. Rep. Stansbury (D-NM) (not related to this site) and Senator Merkley (D-OR), obtained signatures of over eighty members of the House of Representatives and nineteen Senators on a letter calling on Secretary of State Antony Blinken to convince Israel to halt the planned expulsion of over 1000 Palestinians from Masafer Yatta, a small area of villages in the West Bank. Fifteen progressive House Democrats, led by Cori Bush (D-MO), sent a letter that was more forcefully worded, calling the expulsion of the villagers a “war crime.” Recently twenty-four US Senators, almost half of the Democrats in the Senate, called on President Biden to launch an investigation into the killing of Palestinian journalist Shireen Abu Akleh after the Israeli government determined that Israeli troops had nothing to do with it, in spite of overwhelming evidence to the contrary.

By themselves these are small, mostly symbolic actions. But as young people become more conscious, and the contradictions in Israel/Palestine continue to intensify, the movement will grow. The Israel lobby does not want this ember to burst into flame, and it is using the new PAC’s to try to stomp it out before it gets to that point.

Additionally, around the same time as AIPAC made its move, another leading Jewish organization, the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), upped its level of jingoistic rhetoric against those standing in solidarity with the Palestinian people. This past May, in a major speech ADL CEO Jonathan Greenblatt denounced three prominent groups that support Palestinian rights –the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR), Students for Justice in Palestine (SJP) and Jewish Voice for Peace (JVP) – and said they contribute to the spread of antisemitism as much as white nationalists. He described them as “the photo inverse of the extreme right,” and said the ADL plans to bring the full scope of its capabilities to bear upon left-wing opponents of Israel. Even though it has been well documented that antisemitism is far more prevalent on the right than the left, the ADL is so fixated on Israel that they are often willing to forgive the right-wing’s antisemitism because of its support for Israel. And both AIPAC and ADL equate criticism of Israel as antisemitism, by definition, in an attempt to discredit any criticism of the state’s actual attitudes or practices as “antisemitic” and therefore invalid.

What should we do about all this?

It’s a cliché but nonetheless a truism, that all things are connected. We can see that as Israel moves further to the right, its leaders will continue to unite with the right- wing in the US, and try to move both countries to the right, possibly towards fascism. Just look at the bromance between Trump and Netanyahu. Conversely, as working people and people of color become increasingly conscious of how they are being screwed over, they will move to unite with other oppressed people, here and in Palestine. The best way to stop AIPAC’s efforts, is to: 1) demand that the Democratic party do something to stop this theft of democracy. Their silence so far is deafening. And 2) work like hell for the candidates who are pro-Palestine and beat the machine. It’s critical that all progressives move Israel/Palestine closer to the top of their priority list. We have to educate liberals and moderates about the nature of the Israeli state and normalize the Palestinian narrative among the general population. We have to fight for justice in Palestine to counter the efforts of right-wing, racist, settler-colonialists in both countries.

But it’s not all bad news. Summer Lee, running for congress from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, was able to withstand AIPAC’s attack. In 2018 Lee was elected to the stage legislature. She continued to build her community and activist base, supporting Medicare for All, the Green New Deal, strong environmental protections, Palestinian rights and other progressive programs. When the local Congressional seat opened up, she and anti-union lawyer Steve Irwin, competed for the Democratic nomination. In March, Lee was 25 points ahead in the polls. At that point UDC dumped $1 million in negative campaign ads against her. This was on top of the $1.3 million they had spent earlier in the campaign. Irwin gained rapidly in the polls. But Lee’s solid base in the district helped her beat him by a fraction of a percent. Her reputation and her organization were key to her withstanding the onslaught of negative ads, and points to how we can win in future elections.

Ilhan Omar had it partly right. Sometimes it is all about the Benjamins. But candidates with a strong community base, and solid, progressive politics can prevail over deep pockets if movements can be built around them. As progressives, building these movements must be one our primary tasks.

…

ELVIS: A Study in Talent Mis-Management

By Byron Laursen

Baz Luhrman’s recent movie, Elvis, was on my Maybe list, but never jumped into Must-See. Watching his Moulin Rouge (2001) had left me feeling like I’d binged on custard-larded pastries. His The Great Gatsby (2013) didn’t win me back. When a friend wrote that Luhrman seemed to have dumped a load of Elvis lore into a Cuisinart and pressed Puree, I quit thinking about seeing it.

I was far more interested by a quote I came across recently, John Lennon saying that none of the Beatles’ recordings could equal Presley’s “Heartbreak Hotel.” (I agree.)

While perceptions of Elvis, if we’re playing fair, can include his Glittering White Vampire attire from the Las Vegas years, it needs to be said that his early work – when he was an expression of racially different yet congruent strands of old American traditions – constitute the Elvis movie most worth watching. All of it was shot before mismanagement, greed, and bad contracts sapped the best out of a great American star. As they have long done for far too many workers in our dog-eat-dog society.

My own Elvis movie was conceptualized around the time I lived on the eastern outskirts of Fresno and was waiting for puberty to hurry up and assert itself. Courtesy of a big brother I entrusted with a folding dollar, whose friend had a car that could travel to downtown Fresno, I bought the two-sided monster, “Hound Dog” b/w “Don’t Be Cruel,” just as it was climbing the charts.

For years my teachers had sent my parents notes like this: “Byron responds to music and should have an instrument of his own.” They were on the right track, but surely had no idea how powerfully I’d respond to a musical guy who no girl could possibly reject. I wanted to be cool, or at least to fake it successfully. I wanted girls to like me a whole bunch. Elvis Presley seemed to have the opposite-sex-attraction thing going, effortlessly, with no end in sight. So when he released his second album, Elvis (March 1956), I invested the $2.95. It had a country crooner vibe, not the raw and visceral personality of his first album (Elvis Presley, October 1956), and nothing as powerful as, say “Blue Moon” on the essential collection called The Sun Sessions, recorded when he was only 19 and not released until 1976, five months before he kicked from multiple forms of overindulgence. Which, again, I blame on mismanagement, greed, and bad contracts.

Those pre-fame tracks re-engineer the DNA of American music. They press the Black and white elements closer, until a few diverse chromosomes bond onto the same strands. Some have said that Elvis got famous because he was a good-lookin’ white guy who copied Black artists. That’s just as shallow as saying Chuck Berry was a Black guy who got over by borrowing from white country artists. (Note: You can sing “Promised Land” over the chord changes for “Wabash Cannonball.” So Chuck and Elvis did much the same thing from opposite starting points.)

Elvis did much more than copy. Cherokee and Jewish genes helped shape his soulful looks, along with both old-style blues shouters like Big Boy Crudup and postwar jump-blues shouters like “Good Rockin’” Roy Brown, Wynonie Harris, and Elvis’s go-to R&B songwriter, Otis Blackwell.

But as William Carlos Williams wrote in 1923, and Greil Marcus quoted to kick off his essay on Elvis for The Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock & Roll:

“The pure products of America

go crazy – ”

Elvis went crazy because he was thwarted as an artist by a terrible contract with a greedy manager, “Colonel” Tom Parker. Luhrman tried to make Parker more palatable, casting Tom Hanks, but the facts of his life are these: He was a carney with exceptional sucker-fleecing skills: painting sparrows yellow to sell as canaries, shorting hot dog buyers with sleight of hand. He saw Elvis as a cash machine, and induced him to sign a contract that lasted for way too many years, and which gave him half of everything Elvis brought in. Such contracts are no longer legal, but tricking up-and-coming performers remains a strong tradition. Which explains why Steve Stills (of Crosby, Stills and Nash) wrote:

“Somebody tell me – Have I been gifted or robbed?”

Being effed by his manager allowed Presley to experience something well known by the Black artists who inspired him.

When Parker was asked if he took 50% of everything Elvis earned, he said “That’s not true at all. He takes fifty percent of everything I earn.” It gets worse. Earlier, he had failed as a manager to register Presley with BMI, losing his songwriting royalties on 33 songs. When Parker in 1973 sold RCA the rights to 700 Elvis songs, he got $6.2M and the guy who’d sung them to the world got $4.6M. In the three years after Presley died, Parker took an estimated $7-8M rakeoff.

A 1982 suit by the Presley estate recouped some but was settled out of court.

A couple of years before Parker’s death he was seen standing in front of a slot machine in Vegas, a cigar in his jaw and a fistful of silver dollars in his right hand, which rested on his full belly, facilitating insertion of money earned by others into the slot machine for the amusement of an epic greedhead. A fitting final scene for the old bandit.

What happened between Presley and Parker is parallel with all exploitation of workers. As Woody Guthrie wrote:

“Some rob you with a six-gun, some with a fountain pen.”

The researches of Dr. Paul Zak, a founder of the neuroeconomics discipline, have shown conclusively that inequality destabilizes nations. Lack of trust rips a nation’s social fabric.

America’s current passage through Trumpian/Repuglican hell is only one of several examples around the globe. It’s too late to turn around Elvis’s degradation, but America may recapture its promise – to the extent that equity replaces “trickle down” mythology. But if you’re reading The Stansbury Forum, you already agree, and are probably doing plenty to restore American integrity.

So, as a bonus, here are my suggestions for reflecting on the Elvis legend. “Just Like New,” by Jesse Winchester, a songwriter who decamped to Canada during the Vietnam war and returned following Carter’s granting of amnesty, and “Elvis Presley Blues,” by Gillian Welch, whose haunting songs exemplify the “No Depression” category of America’s musical traditions.

…

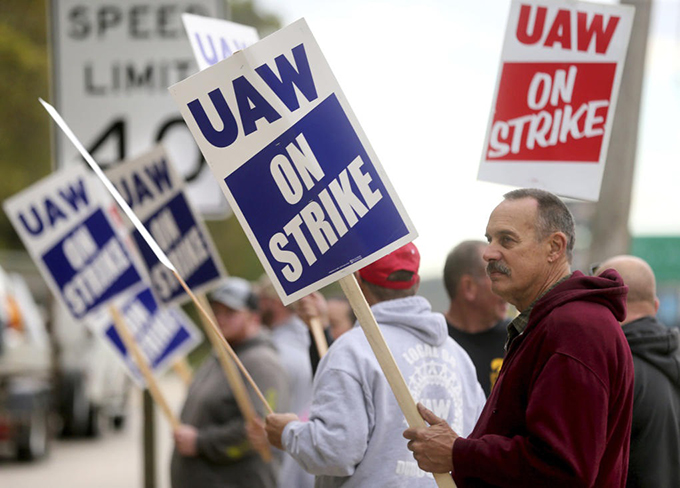

It’s a “Movement Moment” In the U.S.

By Peter Olney and Rand Wilson

During the worst moments of the COVID pandemic, employers and the public recognized front-line workers as “essential.” Workers were given special “hero” pins and sometimes hazard pay. But far too often, “essential” did not mean proper safety equipment, or increased dignity and respect on the job.

Since the start of the pandemic nearly 8 million workers left the labor force, according to federal statistics. It’s a phenomenon known as the Great Resignation. So now as employers compete for staff in a tight labor market, wages have risen by about 5.6 percent in the past year.[1]

U.S. workers are discovering their power.

An uptick in private sector strikes at companies like John Deere, Kellogg’s, and Nabisco last fall — termed “Striketober” — indicated renewed willingness by workers to participate in workplace actions. Stephanie Luce, a professor of labor studies at the CUNY School of Labor and Urban Studies observed, “As someone who’s studied labor issues for the last 30 years or so, I’ve never seen anything like it in terms of the level of interest and excitement from people who want to fight back at the workplace.”

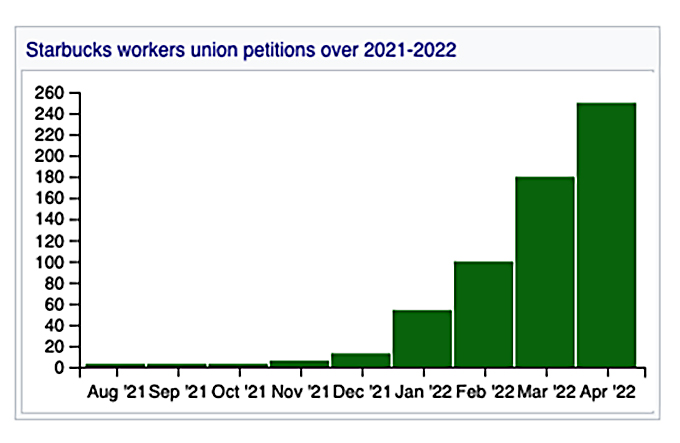

And workers are organizing new unions at an unprecedented number of companies. The NLRB is overwhelmed with petitions for union representation elections.[2] Amazon and Starbucks workers have upended the old common sense for how to organize unions.[3] Now is the time for union leaders to retool their organizing tactics to fit a moment when — finally — workers are leading the way.[4][5]

At the time of this writing, workers affiliated with Starbucks Workers United have filed for union elections in nearly 300 stores across 35 states and have won more than 150 of them. [6]

As long-time labor organizer Wade Rathke recently noted, “Amazon workers have not only organized in Alabama and New York, they have already won one election and more are pending. Groups like Amazonians United have agitated in another dozen locations on issues inside warehouses, distribution, and delivery centers. Starbucks workers have filed for election in hundreds of stores and are winning most of the elections held to date. Apple retail workers are organizing, as are tech workers at game companies, on-line news platforms, and elsewhere. Google workers have kicked up their heels.”[7]

More than a tight labor market

Workers’ experience in the COVID pandemic, the job resignations, a tight labor market, and the increasing popularity of unions have created the conditions for this “movement moment.” But so has the political context.

US President Joe Biden declared his intent to be the “most pro-union president leading the most pro-union administration in history.”[8] It’s proved to be more than rhetoric. Under the Biden administration, the NLRB is finally protecting employees’ rights to engage in protected concerted activities by issuing 10(J) injunctions.[9] The board has already issued twelve 10(j) injunctions in federal district courts against employers to stop unfair labor practices.[10] The Labor Board’s more aggressive support for workers’ rights has emboldened workers to take action.

A note of caution

Despite so many positive signs for the movement, labor in the US remains relatively weak and faces a number of political and economic challenges. A sobering reminder is that union density has continued its decline. Membership is down to 10.3 percent of the workforce in 2021, from its peak of 35 percent in 1954.[11] Private sector membership is hovering at 6.7 percent, down from a high of 35 percent in 1955.

Will labor take advantage of this “movement moment?”

At its recent convention in June, the AFL-CIO committed to organize one million new workers in ten years.[12] One million per year would be ambitious, but only organizing one million workers over ten years means labor’s density (the percentage of total eligible workers), would continue to drop dramatically.[13]

Ironically while labor’s membership density is dropping, its treasuries are booming. A union researcher has calculated that the labor movement is sitting on a huge multi-billion dollar surplus. Now is the time for unions to spend their money on the massive task of organizing giant corporations like Amazon, Wal-Mart and Starbucks.[14],[15]

However, if these organizing initiatives are to be successful, they will need a strong presence of internal workplace organizers. Unions must cultivate and support young people to take jobs in key industries with the sole purpose of organizing. There is no better experience for recently radicalized socialists than participating in labor’s organizing renaissance than from the ground up.[16]

The national collective bargaining agreement between the Teamsters Union and United Parcel Service covering over 350,000 workers expires on August 1, 2023. Amazon is an existential threat to the wages and workplace standards that Teamsters’ union has negotiated at UPS and many other warehouses and transportation companies. Teamster organizers are urging that the contract campaign (and possible national strike) be tightly linked in support of the workers organizing at Amazon.

UPS Teamster Anthony Rosario, a member of New York Local 804 said, “When Amazon workers see us fighting for a good contract [at UPS], they will have a better understanding of what the labor movement is. And when we win a good contract, we’re helping them too. By taking on UPS, Teamsters will be setting the standard for the entire warehouse and delivery sector. We can show the world what a labor movement really looks like!” [17]

UPS Teamster activists are taking time off to enlist their coworkers at UPS to help Amazon workers’ organize and giving aid and support to Amazon workers who are building their union.[18]

Already workers from the Amazonians United network have engaged in coordinated strike action in geographic areas like the Northeast corridor and Chicagoland. These strikes, while small and short term, are great proving grounds for building solidarity and worker confidence. More strategic strikes are likely in the future at key nodes of the Amazon supply chain.[19]

The midterm elections of 2022 and the quadrennial Presidential election loom large for the future of American democracy. The growth of unions, particularly in key nodes in the economy is one of the best antidotes to the fascist appeals of Donald Trump and his acolytes.[20]

…

[1] “Worker-led win at Amazon warehouse could provide new labor playbook,” by Jacob Bogage, Aaron Gregg and Gerrit De Vynck, Washington Post, April 2, 2022,

[2] “The NLRB is overwhelmed with petitions for union representation elections,” NLRB Office of Public Affairs, April 06, 2022

[3] “Staten Island workers vote ‘yes’ for first Amazon union in U.S.,” by Rand Wilson and Peter Olney, Stansbury Forum, April 6, 2022

[4] “How Amazon and Starbucks Workers Are Upending the Organizing Rules,” Chris Brooks, May 31, 2022

[5] “Three Paths Forward for Labor After Amazon,” by Harmony Goldberg and Erica Smiley, Boston Review June 6, 2022, Boston Review

[7] “A Movement Moment and a Real NLRB,” by Wade Rathke, Working-Class Perspectives, May 9, 2022,

[8] “Remarks by President Biden in Honor of Labor Unions,” SPEECHES AND REMARKS, SEPTEMBER 08, 2021

[9] “Protected Concerted Activity“

[10] “NLRB General Counsel Launches New 10(j) Injunction Initiative When Employers Threaten or Coerce Employees During Organizing Campaigns,” February 01, 2022, NLRB Office of Public Affairs,

[11] “Union membership rate declines in 2021, returns to 2019 rate of 10.3 percent,” Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor, The Economics Daily, January 25, 2022.

[12] “AFL-CIO committed to organize one million new workers in ten years,” Ian Kullgren, Daily Labor Report, Bloomberg Law, June 13, 2022

[13] “The AFL-CIO’s Official New Goal: Continued Decline,” HAMILTON NOLAN, In These Times, JUNE 14, 2022

[14] “Now Is the Time for Unions to Go on the Offensive,” by CHRIS BOHNER, Jacobin

[15] “AFL-CIO Budget Is a Stark Illustration of the Decline of Organizing,” By Hamilton Nolan, Splinter, May 16, 2019

[16] “Socialists Can Seize the Moment at Amazon,” Jacobin Magazine, , and a second suggestion for young socialists in 2020, “Amazon Workers Desperately Need an Insurgent Union Campaign,” Jacobin Magazine

[17] “THE UPS CONTRACT AND ORGANIZING AMAZON“, Teamsters for a Democratic Union, JUNE 24, 2022

[18] “HOW WORKING TEAMSTERS ARE HELPING ORGANIZE AMAZON,” Teamsters for a Democratic Union, JUNE 24, 2022, and TEAMSTER AMAZON ORGANIZERS SPEAK OUT, Teamsters for a Democratic Union, JUNE 24, 2022

From volunteer organizing to solidarity rallies, members are stepping up to meet the Amazon challenge.

[20] “Winning Back The Factory Towns That Made Trumpism Possible,” by Mike Lux, Jun 7, 2022

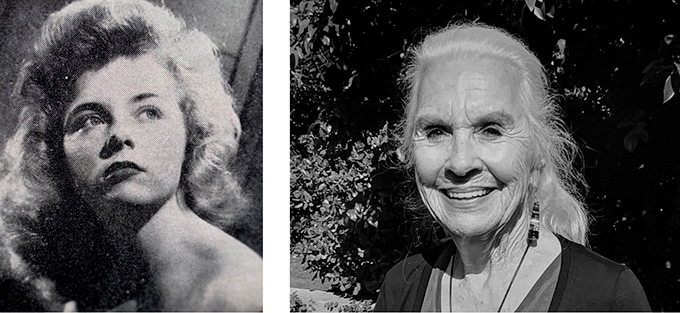

Solving a WWII-era mystery – My mother kept her abortions secret

By Molly Martin

The most personal most shocking secret my mother never told me I had to find out from my cousin Sandy.

In 1974 Sandy had just returned from a decade working for the U.S. Army in Germany. She came home and she came out, returning with a female lover and a seven-year-old stepson. Sandy is ten years older than I, and so represents a generation of lesbians different from mine, women forced to live in the closet before the gay liberation and feminist movements burst upon our scene. Running away to Europe had been a good way to keep her secret.

Sandy and I hung out together in Seattle and one night after a bit too much whiskey (she’s been sober now for many years) she asked me if I’d ever heard the story about my mother’s trip to Paris during the war. My mother, Flo, had told me many stories about working for the American Red Cross as a “donut girl” during World War II in Europe, but I’d never heard that one.

“What was so special about a trip to Paris?”

“Did you know Flo had an abortion?”

“Wow! No kidding! She never told me. How do you know?

“Mom told me. I guess she was sworn to secrecy, but she couldn’t keep the secret. She had to tell someone.”

Sandy’s mother, Ruth, had told her that my mother had traveled from the front lines to Paris, where their sister Eve was working as an Army nurse, to get an abortion. This would have been in the fall of 1944. I had many questions, but Sandy couldn’t answer most of them. We speculated about who the father was and whether Eve had been involved in the abortion.

I was shocked. Flo and I were close and I couldn’t believe she hadn’t told me, her only daughter, about this significant part of her own history.

When Sandy told me the story of the abortion, my mother was still living and she still had three living sisters. I had time and abundant resources. I resolved to find out the answers.

There were times during my childhood when Flo talked about her experiences in Europe. She showed us kids the big scrapbook she had made after the war and I remember looking through it often. Our favorite part was a series of colored pencil drawings made by Liz, one of the Red Cross gals she traveled with in the Army’s Third Division. They showed the “girls” washing their hair in helmets, peeing by the side of the road, driving big trucks, and roughing it in tents. It wasn’t until I opened the album again as an adult that I looked more carefully.

Flo did a pretty good job of documenting her time in Europe, taking photographs with a tiny Minox camera. She had traveled on a hospital ship to Italy in 1943. Her Red Cross unit followed General Mark Clark into Rome as it was liberated by the Allies. She was in France, Germany and Austria as well. She was the only person to photograph the field ceremony honoring war hero Audie Murphy and the photo from her album was later used in the making of a movie about him. She got lots of street cred from that, and several post-war newspaper stories about it are included in her album.

She hated Nazis and that translated into a hatred of Germans, whom she called Krauts. She distrusted Germans as a people, and believed they were all culpable for war crimes, even and maybe especially, those who claimed ignorance. She had witnessed the liberation of Dachau and took pictures, which were “lost” by a German photo shop. But she didn’t really talk about that part of the war until the 70s, sparked by a TV show, QBVII, based on a novel by Leon Uris. That discussion of concentration camp life allowed her to start thinking and writing about her experiences again. But until then she didn’t talk about the Holocaust and of course her album contained no pictures that might have induced questions from us kids.

She did tell us about her fiancé who was killed by a mortar shell, but she didn’t say much. Most of what I know I learned from the album, which includes photos of her and her fiancé, Gene, and letters from his mother in Oregon. There are also letters from other paramours, but she was clearly heartbroken by Gene’s death and not interested in settling down with any other, at least then.

Was she pregnant when he was killed? Did she have an abortion in Europe? Why wouldn’t she ever tell me about it? Why couldn’t I ever bring myself to ask her point blank?

In 1979, Flo and I traveled to Sweden and Norway together to visit our relatives and visit the town in Norway where her father was born. We felt particularly familial. This seemed like a good time to ask and I put some thought into how to approach the question. I didn’t think she would give me a straight answer if I asked her directly. I would have to work up to it.

Me: It must have been difficult to avoid getting pregnant while you were with the Red Cross. Did they issue you birth control?

Her: What!!

Ok, poor opening line, I know. I guess I was implying that she had sex with lots of men. Which would have been understandable. That’s what I was doing.

I felt her withdraw and knew, I think, that she would not have told me the truth even if I’d asked point blank. I didn’t have a Plan B.

In 1983, my mother died without ever giving up the story. But there were still two living sisters, Eve, the nurse, and Ruth, to whom she had told the story. Ruth wrote me a note after a story of mine was published in an anthology about the deaths of our mothers. The story was about Flo’s funeral. Ruth took issue with some of the “facts” of my story. I wrote back to say, essentially, this is my story and I get to tell it my way. If you want your story told, write it. Ruth responded with a wonderfully detailed descriptive story about her childhood. This made me hopeful she might “remember” other details about the family. Might she tell me something more about Flo’s trip to Paris?

After I got Aunt Ruth’s letter, I considered how to respond. Should I start with trivia and slowly up the ante before she caught on? Should I just blurt out what I wanted to know and hope for the best? I decided on a compromise strategy. I did come right out and ask the Paris question, mixed in with a few other family history questions. I don’t believe I ever heard from Ruth again, except she did send me Xmas cards every year, filled with trivia. Then she died.

Aunt Eve must know something, I reasoned. After all, she had been in Paris when Flo visited right after her fiancé was killed. Eve, the nurse, was terribly practical. She also had a knack for talking non-stop over anyone about her boys and her cats. I didn’t think she would lie to me. She asked me to edit a personal history she had written about her time as a nurse in WWII and I used that opening to question her.

When I finally asked the question Eve seemed genuinely perplexed. She knew Flo had been pregnant. Was she pregnant by the fiancé who died? No, Eve didn’t think so. Well, who was the father then? She thought it might have been another guy Flo was dating. Really? I’m thinking: your fiancé dies, you are disconsolate, and then you get pregnant by another guy? I didn’t think so. But Eve remembered that Flo had told her she had miscarried while carrying heavy packages when moving to a new camp. She didn’t think Flo had had an abortion at all. My assumption that Ruth had gotten the information from Eve did a back flip. Flo hadn’t told Eve! She had only told Ruth, her closest sister, and sworn her to secrecy.

Flo and I got feminism together. As every new book came out about the movement, we rushed to the bookstore to buy it. I still have my copy of Sisterhood is Powerful, which she inscribed to me. She got angry about how she was treated at work. She was paid too little for what she did. When I went through her things after she died, in her jewelry box was a little pad of notes that could be pulled off, licked and stuck on something. They read “This Insults Women.” So many things then insulted women. We were sticking stickers on the world.

In 1972 the first Issue of Ms. Magazine was published. Flo had kept it and I found it in her collections. In the very first issue was a section about abortion. Famous women, so many of them, admitted publicly to having had an abortion. It was liberating! Until then abortion was not talked about. I didn’t imagine at that time that my mother had had abortions. I myself had been very careful not to get pregnant. But by the time I became sexually active, birth control pills had become available and I made sure I was on them before I chose to have sex with men. It seemed to me that getting pregnant would be the end of my world. In high school (before I ever had sex) I once asked my parents what they would do if I got pregnant. They said they would find an abortionist. Later, when I became a feminist activist in college, I realized this was not so easy.

I wondered if my dad knew about Flo’s trip to Paris and the abortion. After Flo died, he came to visit me in San Francisco with one of his many girlfriends.

“Hey, tell me something. Did you know Flo had an abortion when she was in Europe?”

He said he hadn’t known, but, he said, “I bet I know something that you don’t.”

“What?”

“She had an abortion before you were born. We had just gotten married and we didn’t see how we could afford kids. I drove her to Portland for the abortion.”

I was flabbergasted. Here was another secret she had kept from me! Now I wonder if my parents were even married then. In 1947 you didn’t go around telling folks you were pregnant and unmarried. Also, we could never believe anything Dad said; he was full of blarney.

Later I learned of Ruth Barnett, the abortionist who ran her business in Portland from 1918 to 1968. After she became pregnant in 1911 at 16 and had an abortion, she was convinced that all women should have the opportunity to receive an abortion if they wanted one. Barnett was the target of frequent raids, and was in and out of jail, but she kept it going for 50 years, retiring only after being convicted and sent to prison.*

Flo had kept the story of both her abortions secret from me, and she’d kept the Paris abortion secret from her husband all her life. Was she afraid of having to talk about Gene, the love of her life, to her husband? Maybe, like the concentration camps, she just didn’t want to go there again. Or maybe the shame was too deep.

World War II was a global conflict on an unprecedented scale. Women all over the world were recruited to serve the armed forces in many different roles. Approximately 400,000 American women served in the armed forces. What did the Army do when they got pregnant? Logic would indicate the military had some sort of policy, written or informal, to handle pregnancies for women who didn’t want to bear children. I hope so. I hope my mother didn’t have to seek an underground abortion in Paris.

…

*Ruth Barnett memoir: They Weep on My Doorstep. Also The Abortionist: A Woman Against the Lawby Rickie Solinger

Zero Population Growth Starts Here

By Eve Goldberg

The following stories are true. The first two are the memories of friends – which I recorded and edited. The final story is my own.

— E.G.

1 – DONNA

When my aunt found out that Aaron was Jewish, she told me to move out of her house.

It was 1951. I was working as a probation officer in Cleveland, Ohio. It was my first job after college. I had been dating Aaron, a reporter for the local paper, for about a year.

After I left my aunt’s house, I rented a room on the second floor of a house nearby where I had my own bathroom and tiny kitchenette.

Then I missed my period. I had been using birth control, a cream called Norform, but my periods were usually very regular, so I was worried. I told Aaron about it and we went to see a doctor who was a friend of his. The doctor gave me a pregnancy test and it came back positive.

So there I was. I was pregnant, unmarried, and 23.

In that time and place, my friends and family would have considered it shameful if I got pregnant without being married, and also shameful to get married just because I was pregnant. But more to the point, I just plain didn’t want to get married. I wasn’t ready for it. And I definitely didn’t want to have a baby — it was the furthest thing from my mind.

So we asked Aaron’s doctor friend if he would do an abortion. “Oh, no!” he said. “I’d lose my license.” He did tell us, though, that if a psychiatrist vouched that an abortion was necessary for my mental health it could be done legally.

I remember the psychiatrist vividly. He was tall and skinny and kind of bent over, and he and wore glasses with thick black rims. He listened while I told him the full story about my relationship with Aaron, that I’m pregnant, and not only did I not want to get married under the gun, I didn’t want a baby. Period. I told him that I didn’t think I could handle having a baby. I remember so well what happened next. This psychiatrist looked at me and said, “I think you can handle it.” And you know what? That’s when I really came into my own. Because it’s true, I probably could have “handled it.” But it wasn’t what I wanted. He didn’t give a flying fuck about me. It made me mad. Really mad. That’s when I knew I’d have to get an illegal abortion.

So Aaron checked around and found a doctor who’d had his license revoked for giving abortions. We made an appointment and drove out to his house which was in a suburb of Cleveland. The street was lined with maple trees, and it was autumn, so the trees were full and bright red. The doctor lived in a two-story white house with a deep front porch.

We knocked and the doctor let us in. He was a middle-aged man, probably about 50. There were a couple of chairs set up in the entry area where we sat, and the doctor asked me questions like: Why did I want an abortion? Was I sure about this decision? Things like that. I told him the truth. Aaron stayed in the entry area, while I followed the doctor into a room which might have once been a study. It was setup with one of those high examination tables and stirrups. I was way too nervous to really check it out. I was scared. I wasn’t scared about it being illegal, but I cared about my body. I didn’t want to be hurt or injured. I put my feet in those stirrups, and I remember feeling very vulnerable. I didn’t know what he was going to do. The details after that are a blur. Afterwards, the doctor told me to expect passing some blood clots within the next 24 hours, at which time the abortion would be complete.

The next day nothing happened, no blood clots. I called Aaron that night and told him that nothing was happening, I wasn’t passing anything. So, he called the doctor and we went back the next day and he did a second abortion. I was feeling fine, so Aaron dropped me at the place where I was living, and he went home. This time, though, I started to cramp and bleed — lots and lots of blood, for hours — so much that I got really scared. I thought I was going to bleed to death. I felt isolated and afraid. Other than Aaron, I had nobody to talk to about it, nobody to turn to and ask questions. I frantically called Aaron and told him what was happening. He called his doctor friend — the one who did the pregnancy test.

That doctor came immediately that night to my place. He examined me and gave me a shot and some medicine, it might have been antibiotics, I’m not sure. The profuse bleeding stopped, but I kept spotting for six weeks. I knew I’d better go see to a regular, legal doctor. I went to an ob-gyn. I was nervous about telling him that I’d had an abortion because I didn’t know if he’d report it to the police, or what. But I felt like my health and maybe my life was at stake, so I told him the truth. He examined me and told me I needed a D&C, which would clean out my uterus. He arranged for me to go to a hospital to have it done.

So, I had the D&C in the hospital, and that was finally it.

The whole abortion ordeal definitely influenced my life. To cut to the chase, after Aaron and I broke up, I married the next man I dated — Jack. I thought to myself: You sleep with him and you’re going to get pregnant again. Then what are you gonna do? I didn’t want another illegal abortion. And I was also thinking, I need to get married. All my high school girlfriends were already married. I was the last one. I was 24. So, we got married. I never regretted marrying Jack — he was a very sweet and decent person — but there was also that pressure I felt, it was definitely part of the picture. Jack and I had three children, and I was so relieved that they all came out healthy and whole.