About Those “LA Audio Tapes” and How to Heal Los Angeles: We Have Questions

By Jorge H Rodriguez

The words spoken by several prominent elected Mexican, Latina(@) officials in 2021, and recently revealed on tape, were prejudicial, discriminatory, mean, and hurtful to everyone they were directed at. But they were not expressed by racists, or white supremacists as some people who have written or spoken about this incident have claimed.

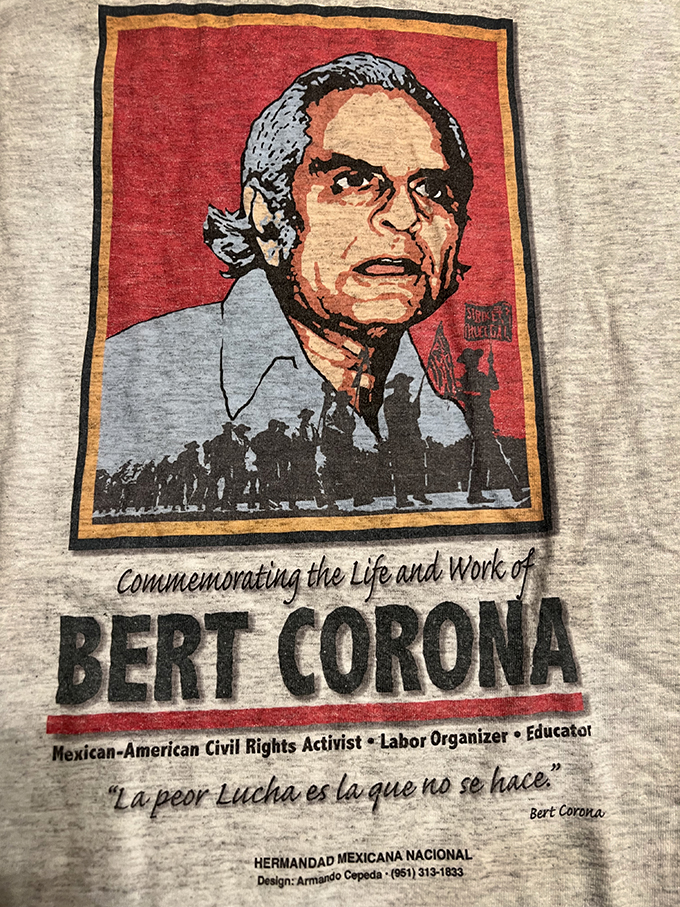

We know the social, political history and the core values of Martinez, Cedillo, De Leon and Herrera. Cedillo, along with former Mayor Villaraigosa, and Senator Durazo were all part of CASA, a national immigrant workers’ rights organization, which fought from 1972 to 1986, to gain amnesty for all immigrants in the US with the passing of the 1986 Amnesty IRCA Law signed by then President Reagan. In1994 Cedillo, then the leader of SEIU Local 660, along with the LA Federation of Labor spearheaded the fight against Governor Wilson’s anti-immigrant Proposition 187. All of the elected Mexican/Latina(@) officials participated in the mega immigration marches in 2006, including the now famous “Day Without An Immigrant” on May 1, 2006 where over 1.5 million people marched in the streets of Los Angeles, joined by millions more across the country, against the racist immigration Sensenbrenner Bill.

Cedillo, once called “ONE BILL GIL”, fought for nine years to pass a law giving undocumented workers the right to drive in the state of California. He made it safe for families to take their children to school, to shop, drive to work, to go to playgrounds, and beaches without the fear of being detained and deported.

Kevin De Leon has been an immigrant’s rights defender since his early days in the late 1980’s working at One Stop Immigration. He has been a tremendous fighter for the environment and workers’ rights in California. During De Leon’s time in the Senate, he took on President Trump and his allies on immigration and helped pass landmark legislation establishing sanctuary in the State of California. He became the target of racists and white supremacists throughout the state. He was constantly receiving death threats.

Martinez rose from the streets of the San Fernando Valley becoming a leading force fighting for environmental issues and inclusion of her neglected community in the west valley. She was elected to the LA Board of Education and finally to the Los Angeles City Council; becoming its first Mexican/Latina(@) president.

Ron Herrera has been a champion for working people for over 30 years. He grew up in the West Wilmington, a working-class union family community in the LA Port area of Los Angeles. He began working as a warehouse employee at United Parcel Service (UPS). Then he became a driver, and a Teamsters shop steward. Ron helped lead the largest strike in U.S. history, the 1997 strike of UPS workers which helped to end low-wages for part-time employees. In 2003 Herrera was elected as Secretary-Treasurer of Teamsters Local 396, the largest UPS local in the country. He later became a national leader as the first Mexican/Latino national vice president of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters. He was a key figure in the “Don’t Waste L.A.” campaign uniting environmental, community and labor leaders to create an innovative franchise that increased recycling efforts across Los Angeles and raised industry standards. It was under his leadership that during the Pandemic the LA FED served up bags of food feeding over 350,000 working families and community members throughout the LA region creating an inclusive and innovative labor movement for all workers.

The ignorant words used in the conversation they were having should not take away from all the important civil rights work and things they have fought for. Fights and programs that have advanced the wellbeing of women, immigrants, and working people in California, the City of Los Angeles, and the country. Cesar Chavez once called immigrants “Illegal Aliens” and “Wetbacks”, “Those Wets” during a congressional hearing.” Chavez later colluded with the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) to deport immigrants during a strike. He is still looked upon with admiration for the things he did. Why should these leaders be treated any different? This incident does not define them.

What key elements have not been written about in the heated debate taking place in the Los Angeles right now?

As Bill Gallegos and Bill Fletcher Jr. Point out in their excellent article: The Racial Volcano Explodes in Los Angeles Portside.org, the issue of representation is still the elephant in the room. The LA Times has framed the issue as one strictly of racism and fomented the idea of division among Angelenos. Yet the demographics of LA show clearly how under-represented communities are in the halls of power; for instance Mexicans/Latina(@)s make up about 48% of the city’s residents and only have 26.6%% representation on the LA City Council. The current three black city council districts, 8, 9,10, were left unchanged during the redistricting process in LA. So all this postering and talk about anti-black is “JUST NOT TRUE”. The discussion centered around the future of these districts where Mexican/Latina(@) and Black populations are heading in opposite directions – Mexican/Latina(@) are increasing and Blacks are moving out – especially in the 9th.

Let’s be honest, all the LA city council members have discussions about their, and their supporters, interests now and in the future. We need to address the issue of equitable representation so governmental reflects the residents and living patterns of LA.

With just four weeks before election day, the timing of this year-old audio is no coincidence. Why did whoever released the audio wait a year to make it public? It’s a calculated attempt to damage the important electoral work being taken up by the LA Federation of Labor. Headed by Ron Herrera, the LA Fed had built, and was about to send hundreds of union workers to phone banks, and precincts to knock on doors to ensure voters could and would vote.

The audio’s release was also a deliberate attack on the Mexican/Latin(@) community, an attempt to undermine the political leadership and influence of their elected officials. Mexicans/Latina(@) are already underrepresented in the city council, board of supervisors and the board of education. The vacancies that are expected in the coming days will leave an even bigger vacuum of leadership over our community while poverty and a lack of services remain, unreported in the media stampede to create inflammatory headlines.

We need to continue to work to combat our community’s prejudices against people of color.

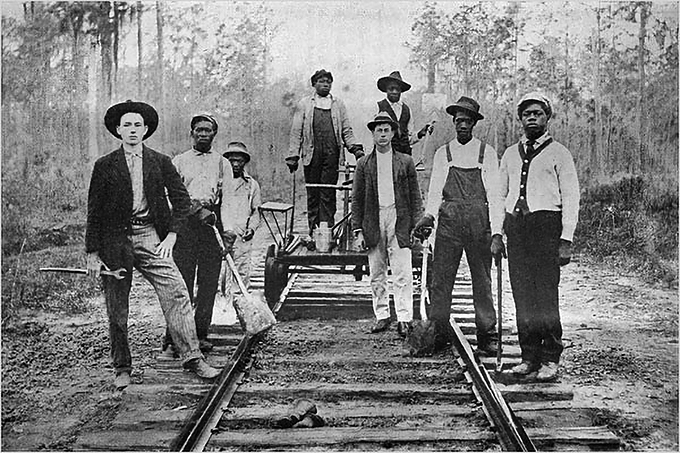

The solidarity of our communities dates back to the times when Mexicans helped enslaved Africans cross Texas into Mexico to escape slavery. In the 1930s Black, Latin@, and white seamstresses where organized by Guatemalan labor organizer and civil rights activist Luisa Moreno. That solidarity is as true today as it was then. We must continue the work of eradicating our own self-loathing of our indigenous people. We can’t permit this type of thinking at all.

The audio release was further intended to open historical wounds of indigenous peoples of Mexico and the US who have traditionally not been represented in the halls of government. The comments about them were mean and a reminder that Oaxacans, like all indigenous people, are objectified and treated as if they are invisible. It is also a reminder that indigenous peoples in the US are rendered invisible in the media, totally omitted on coverage of issues of white supremacy and racism, police brutality, health, the environment, and the current crisis of the disappearance and murder of indigenous women and girls.

This was also an effort to drive a wedge and mistrust between Black and Brown communities who have worked for decades to form strong and meaningful alliances. In the last 20 years the LA Fed has played a historical role, helping build mutual trust and a working alliance around issues affecting both communities. In workplaces where race, ethnicity and gender are often used by bosses to divide workers on the job and off. The LA Fed, through its unions, has pushed for equality of pay and opportunity, strengthening workers’ rights on the job and improving the communities in which they live. Of course, work remains to be done. We still need to strengthen the bonds of our communities and those of other people of color in LA.

While the timing of the release raises questions, we must not forget to ask: Who benefits? Why was it made? Who released the audio? Who made it? What was their goal?

A broader question for LA is: Do we really want to heal? Or do we just want to be punitive?

In order to heal we need to expose the real efforts and intent of those behind the leak. Only when this is done will we be able to regain the trust between our communities and among all Angelenos.

…

Peak Season for Action at Amazon

By Rand Wilson and Peter Olney

Could this November see the biggest coordinated international day of action at Amazon yet?

Although Thanksgiving is a unique U.S. holiday, the day after—known as “Black Friday”—is celebrated in many countries as the opening of the Christmas shopping season. In Italy, for example, merchants offer Black Friday discounts that fill their stores with the same bargain-hungry shoppers as in the U.S.

That’s why three Italian trade union federations chose it as a strategic day in 2017 to strike Amazon’s million-square-foot distribution center in Castel San Giovanni, near Piacenza in Northern Italy.

The San Giovanni facility opened in 2015. Two years later, half of the 1,650 permanent “Blue Badge” employees struck on Black Friday. While there had been some previous job actions at Amazon in Germany, this was one of the first Amazon strikes in Europe, or, in fact, anywhere.

Amazon spokespersons insisted that the strike was only 10 percent of the workforce because they love to undercount and because they factored in the 2,000 “Green Badge” employees—short-term and seasonal workers—who mostly came to work. Nevertheless, the company agreed to negotiate with the unions the following Monday.

Then management canceled negotiations and sought to reschedule the meeting unilaterally for the following January. The unions warned there would be more actions if there were no substantive face-to-face discussions by December 6. In a victory for the unions, on December 5, Amazon management agreed to meet and subsequently bargained improvements in working conditions.

The Italian actions and later Amazon strikes in Germany and Poland were hugely inspirational to us (in fact Peter Olney was in Italy during the Castel San Giovanni strike). We believed they would help motivate more worker organizing in the U.S. and thus began urging young activists to get jobs at Amazon.

COALITION TARGETS AMAZON

Since 2017, coordinated international actions targeting Amazon have increased. In 2019, UNI Global Union and Progressive International launched Make Amazon Pay, a coalition uniting over 70 trade unions, civil society organizations, environmentalists, and tax watchdogs. The coalition’s unifying demands are that Amazon pay its workers fairly and respect their right to join unions, pay its fair share of taxes, and commit to real environmental sustainability.

Last November, peak season actions took place in 25 countries around the world. However, past participation by unions and organizations in the U.S. has been modest at best.

The organizing successes at Amazon facilities—including winning a National Labor Relations Board vote at a Staten Island Fulfillment Center in April—and the numerous walkouts over pay and conditions in Amazon facilities from Maryland to California reflects a new spirit of labor militancy in the U.S. Building on that opportunity, UNI Global recently convened a meeting of rank-and-file Amazon organizers and union leaders to begin planning for Black Friday actions in the U.S. We hope this will lead to high-profile walkouts and rallies targeting U.S. Amazon facilities on November 25.

In addition to the substantial increase in worker organizing at Amazon, other factors could contribute to broader support and participation in U.S. Black Friday actions this year:

- The Teamsters have already begun a contract campaign for their 340,000 members at UPS;

- Members of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU), the West Coast dockworkers union, are working without a contract as negotiations continue with the Pacific Maritime Association;

- Railroad workers are voting on national agreements bargained with the big freight railroads. The membership of the Brotherhood of Maintenance of Way Employees, the third largest rail union, just voted to reject the contract and could strike as early as November 19. Votes in the two largest unions, representing engineers and conductors, are pending. If members vote to reject these agreements, it could lead to a dramatic work stoppage affecting the 40 percent of U.S. GNP that travels on rail;

- The increased support for unions generally—thanks to the courageous organizing by Starbucks and Amazon workers, prominent strikes by Nabisco, Frito-Lay, Kellogg’s, and John Deere workers, and the respect for the role of essential workers during the pandemic—means that Black Friday protests will be perceived as part of a much broader labor movement.

Could these combined developments lead to a “Peak Season” moment when logistics workers at many companies across the entire sector take action together? Imagine Teamster drivers and warehouse workers protesting at UPS barns, then marching to nearby Amazon facilities to support walkouts by workers there. Or dockworkers and railroad workers taking their message to workers at intermodal facilities that handle Amazon freight. Or thousands of warehouse and delivery workers at smaller companies using Black Friday as a strategic opportunity to dramatize their power in the supply chain and begin forming their own unions.

While much of the above may only be a dream for this November, it’s the direction that the labor movement is headed in. For now, it’s realistic to envision U.S.-based peak season actions dovetailing nicely with Make Amazon Pay activities around the world. Logistics workers of the world, unite!

.

This piece is also running in Labor Notes

…

Review: Our Veterans: Winners, Losers, Friends, and Enemies on the New Terrain of Veterans Affairs

By Kim Scipes

This country is really good at sending young people off to war, killing people, animals, plants and the environment overall while destroying buildings and highways, and disrupting people’s lives and societies wherever the US invades. The US has turned this into an art form. What they haven’t done well is taking care of the women and men they send to do their dirty work once these servicemembers return from the field of battle; or even from their term of “service.” This new book by Suzanne Gordon, Steve Early, and Jasper Craven does an excellent job of pulling the covers back and illuminating the governmental disservice to these veterans.

This book gets behind all of the “Yankee Doodle Dandy” bullshit that is propagated throughout our society about military service. The military picks on young people who often want desperately to contribute to the well-being of our society, to make it better, and who think military service is a noble cause, as well as those living in economically devastated areas and who are willing to do almost anything to get out and be able to (ultimately) try to get another shot at life. The key thing to note is the emphasis on young people: they want to get to them before they learn to think critically about what they are being told, and before they figure out that they have options otherwise that they may not have known about or even considered. (Increase the minimum age of enlistment to 21, for example, from 18 or 17 with parental approval, and I’ll all-but-guarantee that enlistment rates plummet; free college education for all would have a similar effect.)

The strength of this book is the clear thinking behind it. Most importantly, for which I’m extremely grateful, is that they recognize that “veterans” are not just a bunch of flag-waving “patriots” that don’t have a brain in their head. Yes, there are some like that. Military service affects each person who survives it; some say it was the best time of their lives, while others recognize they have had their desire to improve life to be distorted, instead causing great pain and suffering to wherever the US sent them. Add in a suicide rate averaging 22 veterans a day, along with massive amounts of alcohol and drug abuse, and you see the human cost to many of the US’s veterans. The key thing to recognize, however, is that “veterans” are not a monolithic group.

And “Veterans of all types experience higher-than-average rates of joblessness, homelessness, chronic pain, mental illness, and substance abuse.” Approximately one-in-three women veterans are survivors of military sexual trauma from their military “comrades.” “These problems,” the authors note, “were particularly acute among former enlisted men and women who returned to poor and working-class communities slow to recover from the great recession of 2007 and 2008.”

This is worse than for previous veterans: 44 percent of today’s veterans are suffering re-integration problems, as compared to 25 percent previously.

The thing the authors make clear is that military service itself, excluding combat, is dangerous. This begins in boot camp, when the military tries to break down and then re-establish one’s personality; this varies with branch of the military, with the Marines being the most determined to build a “new” you. Again, varying with branch, physical punishment is a key component in this process, whether direct physical attack or the work of “motivation platoons,” where the insistent digging and refiling and digging and refilling deep holes in the ground while incessantly being screamed at by a charming “drill instructor” who helps convey the message that you better get with their program—or you will continue to “pay” for your failure to comprehend.

Beyond that, many of the jobs that service people have to perform are inherently dangerous, whether driving a tank or a truck over imposing physical obstacles, firing artillery, or working on war planes, with screaming jet engines, live ammunition, and active ordinance, including rockets and bombs: what could possibly go wrong? Service at sea also brings additional hazards for those in the Navy and Coast Guard, as well as for those who fly.

And then combat accentuates these dangers to the nth degree: not a single combat veteran I’ve ever met has come out unscathed, and many survivors have taken years to get themselves back together, if they ever do.

The US Government has an agency, the VA or “Veterans’ Administration,” that is supposed to provide medical resources to help veterans overcome whatever they experienced in the military when they present themselves for treatment. The authors point out that, when fully resourced, the VA generally does an excellent job of serving veterans. Their treatment of physical injuries is deemed quite good, and while it varies between facilities, the VA seems to be dealing better with mental health-related issues over time; it took multiple veteran occupations of VA facilities during the Vietnam War to get the VA to begin to address the issues of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Since many of the VA employees are veterans themselves, it shows that veterans in VA facilities can often get more sympathetic help than they can in most “civilian” facilities.

The problem, however, is tied to the phrase “when fully resourced.” The government has never fully funded the VA, and in fact, Congress has been channeling significant amounts of money away from the VA, supposedly to improving services for veterans—especially those physically distant from VA facilities—but have done this in a way that has undercut the VA itself and its ability to provide support for veterans in general.

Challenging the attacks, the authors argue that the VA is so good—when fully resourced that it serves as a model for the entire country, showing how a single-payer system could/should work. This is important. In fact, they point out that something around 70 percent of all medical residencies in the country are carried out in VA facilities today, and that the VA served as a back-up medical system for when our medical system was overwhelmed by the COVID pandemic.

These political attacks have been given “cover” by a number of right-wing veterans serving in the House and Senate, as well as conservatives in office who cannot wave the flag enough, the “uber-patriots,” many of whom avoided serving, but who work desperately to deny the impact of their own decisions, effectively they don’t give a shit about veterans.

Gordon, Early, and Craven deplore this, and detail what is really going on behind the flag-waving. Interestingly, they point out that most of the right-wing veterans were officers, and that we must not conflate their efforts with those of enlisted personnel who have often borne the brunt of officers’ decisions.

The strength of this book is its honesty about the whole field of military service and its effects on those who survive it; as well as, those who don’t. The authors demonstrate through this, and previous activities, their concerns for the well-being of those who have served. Their writing is straight-forward, clear, and honest.

However, I have two criticisms. First, I think they delve into the veterans’ world more deeply than many would on their own. To be honest, it can be very depressing to learn a what goes on with veterans’ groups, many who, despite their stated “missions” and their rhetoric, work against addressing real needs and concerns of veterans. This is even worse when their actions provide “cover” for the right-wing who use veterans’ groups positions to justify their own.

Second, and my larger and more important critique, begins with the cover photo and title of the book, and extends beyond. I don’t like the cover and title! In my opinion, these are not “our” veterans; they are the veterans and victims of the US Empire. “We” didn’t send them to Vietnam, Iraq, Afghanistan, or any of the other place around the world where they’ve been sent, political leaders, both Democrats and Republicans, sent them. These “leaders” bear responsibility for this, as is their failure to care of these men and women after their return home.

I don’t think sufficient attention has been paid in this book to explaining and understanding the US Empire: while these political leaders suggest our country and the Empire are the same, the reality is that they are not. The United States is our country, where we live, but the US Empire includes everywhere in the world that the US seeks to dominate. Our country is not at risk from others, despite all of the propaganda; the US Empire is at risk. If the political leaders want to defend the US Empire, let THEM do it. As Phil Ochs said, “I ain’t marching anymore!”

.

Our Veterans: Winners, Losers, Friends, and Enemies on the New Terrain of Veterans Affairs

By Suzanne Gordon, Steve Early, and Jasper Craven

Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2022. ISBN: 978-1-4780-1854-4 (paper), $24.95

…

Exhibit: Two Years of Heat and COVID in the San Joaquin Valley

By David Bacon

“Two Years of Heat and COVID in the San Joaquin Valley”, Photographs by David Bacon

Opening Reception: Thursday October 13th, 4:30 – 6:00

For more information: Robin DeLugan (rdelugan@ucmerced.edu)

In the San Joaquin Valley, the most productive agricultural area in the world, rural poverty is endemic. That poverty produced COVID infection rates far exceeding, per capita, any urban area in California. Rural communities enduring the pressure of low wages and bad housing became coronavirus hotspots.

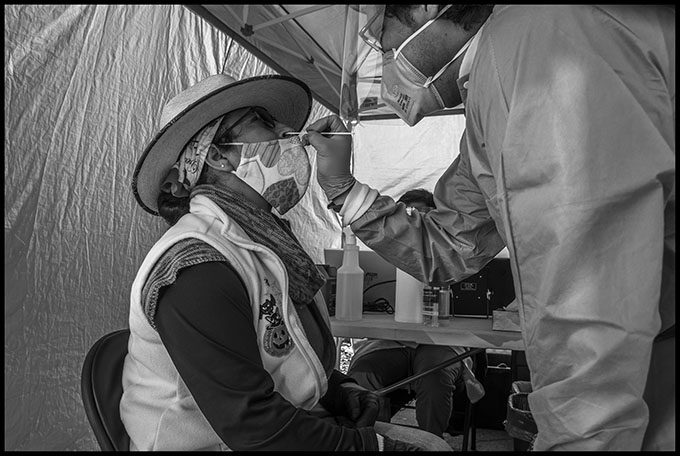

This exhibition presents this complex reality through documentary photographs taken in the course of the pandemic and the past two years’ heat dome crises. They concentrate on the daily lives of farmworkers and their families, including Filipino immigrants and in particular indigenous Mexican migrants, who did the essential labor that ensured that food left the field to supply supermarkets and dinner tables. They also show that while COVID created enormous risks and problems, in many ways people lived in conditions that existed long before the pandemic began.

In these images, farmworkers appear masked and exhausted as they pick grapes, pluots and persimmons. The series documents the crisis in rural housing, and the efforts of local communities to build homes using self-help projects. Haunting night photographs taken in Fresno show the streets of San Joaquin Valley’s largest city empty except for people sleeping on sidewalks, or working in taco trucks into the early hours of the morning. Indigenous farmworkers labor as irrigators in 114 degree heat in the sun all day, while crews pick and toss watermelons into trucks—one of the most physically demanding jobs in agriculture. The growing number of H-2A guestworkers are shown both as they harvest cantaloupes in the harsh temperature, and the rundown motels where they’re housed.

The pandemic and the crisis of climate change threw the problems of social injustice in our society into high relief, and I tried to document this reality as I’ve seen it. In May, 2021, the California Newspaper Publishers Association gave its first place awards to this series of images taken in the San Joaquin Valley, and the Los Angeles Press Club gave it a first place in the Southern California Journalism Awards in 2022.

This exhibition consists of 67 black and white photographs and oral histories giving their context. It is a continuation of previous projects that document the lives of indigenous farmworker communities, including Living Under the Trees and In the Fields of the North.

The photographs are produced as a cooperative effort with the Binational Front of Indigenous Organizations (FIOB), the Central Valley Empowerment Alliance, California Rural Legal Assistance, the Leadership Counsel for Justice and Accountability, and the United Farm Workers. The photographs are used by partner organizations in campaigns for immigrant rights and better working and living conditions. Part of this effort includes using the exhibitions to organize dialogues within these communities about indigenous identity and culture, and ways to advocate for equality and social justice as migrant communities in the U.S., opposing an abusive and dysfunctional immigration system.

Public support is vital to creating a broad movement for immigrant rights, labor rights, cultural respect and the social justice demands of Mexican indigenous migrant farmworkers. This project is part of that effort, at the same time helping documentary photography survive as a medium for advancing social justice.

…

“Two Years of Heat and COVID in the San Joaquin Valley”, Photographs by David Bacon

October 1 – February 10, 2023

Kolligian Library, 5200 N. Lake Road, 5200 Lake Rd #275, Merced, CA 95343

To: Brothers and Sisters of the Railroad Unions

By Bill Bon

Re: The Tentative Agreements

I’ve frequently observed that railroad freight labor contract negotiations are the most politicized collective bargaining regime in the private sector. What do I mean by that? First, there is the structured processes of the Railway Labor Act, which provide for an executive branch agency, the National Mediation Board (NMB), with members appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate. With only the rarest of exceptions, the NMB controls the pace and timing of collective bargaining, with the ability to delay or advance the end of mandatory mediation. That is a critical piece of the RLA ‘map’. The actual terrain of battle is more complex.

Who appoints the NMB matters, as does just who sits on that Board. Who the President appoints to a Presidential Emergency Board (or even if one is to be appointed at all) matters, as does who controls the House and Senate. (And, of course, in the long run, the make-up of the courts, appointed and confirmed in political processes, matters as well.)

Freight rail management has demonstrated a long-term refusal to engage in serious give-and-take bargaining with the organized workforce. Instead, they have sought political fixes to their labor relations, and it has worked so well that they refuse to depart from a system which they have frequently managed to their benefit. For example, they used political mechanisms to relieve the railroads of their collective bargaining agreements with their employees, in the course of undertaking the mega-mergers that resulted in today’s monopolistic carriers. So, too, with bargaining over changes to agreements. By judicially enforcing participation in multi-employer bargaining, the major railroads’ single representative (National Carriers Conference Committee of the NRLC) deals with all of the unions, on the same timeline. Then, the NMB has virtually non-court-reviewable authority to control the pace of bargaining, by controlling the timing of termination of mandatory mediation; only then can the ‘released’ parties move towards self-help (strike, lockout, or imposition of the employers’ final offer.)

Because the threat of a total railroad shut-down has national implications, Congress has sometimes legislated, at endgame. Most recently, back in 1991, they passed legislation that, when signed by the President, imposed a Presidential Emergency Board’s (PEB) formally non-binding recommendations for settlement as the new “agreements” between the carriers and their employees, and prohibiting further ‘self-help’.

So, having some elected and appointed friends sitting at veto points in Washington, DC can make all the difference in the world to railroad workers. Who appoints the NMB matters, as does just who sits on that Board. Who the President appoints to an Emergency Board (or even if one is to be appointed at all) matters, as does who controls the House and Senate. (And, of course, in the long run, the make-up of the courts, appointed and confirmed in political processes, matters as well.)

My first encounter with a PEB was in 1991, PEB 219. The railroads cut train crew size, extracted massive rules concessions without paying for them, instituted health insurance cost-sharing, and enforced wage rates that failed to keep up with inflation, all by persuading the Congress and President G.H.W. Bush to impose PEB 219’s report as the new terms of employment, ending a short national strike.

Understanding that a national transportation emergency was the predicate for a legislated resolution, we refused to shut down the entire country in 1992 (PEBs 220, 221, 222), limiting picketing to CSX. The railroads weren’t having it. They ceased operations nation-wide, locking-out the unionized workforce, including the employees who were already living under the imposed terms of PEB 219. They created a national emergency to force Congress’ hand. There was some grumbling, but they got their way: Congress mandated “baseball” last-best-offer interest arbitration of the open disputes, and an end to the lock-out.

In the ensuing years, no nation-wide shutdown has occurred, but the view that the end game in national handling would lead from release by the National Mediation Board to a PEB and then imposition by Congress became a commonly held belief. Of course, that is not what is in the statute, and there is no reason to enshrine a process that management has manipulated to its benefit, as the inevitable result of a big-table impasse.

Let’s catch up with the current round, commencing before the 2020 elections. Trump was demonstrably an enemy of labor. His Federal Railroad Administration chief Ron Batory pretty explicitly said he was there to serve railroad management (per a talk given at RailTrends). The agency killed two-person crew rule making at the state level and declared that the topic is federally preempted; that is, the states could not legislate or regulate on the subject matter. Trump’s administration demonstrated that they are not the sort of people we would want shaping our collective bargaining outcomes!

When bargaining began, while Trump was in office, the railroads served aggressive demands: single-person train crews, work rule concessions for the non-ops, wage erosion, no back pay (contrary to customary expectations. Remember, these talks get dragged on for years…). I saw the carriers’ demands as an attempt to do a rerun of the film of 1991: cut train crews and extract devastating concessions across the board for free, all with the political connivance of the Republicans then in power.

But, the best laid plans, etc. Joe Biden won!

The railroads didn’t get their way. They complained that a release was premature, when the Democratic-majority NMB pressed for serious bargaining, then proffered voluntary arbitration, the start of the count-down to a PEB and possible self-help. This is exactly what the railroads didn’t want, as it would mean an endpoint while the Republicans control neither the White House (and its administrative agency appointees), or the Congress.

Biden appointed an Emergency Board, as provided for in the Railway Labor Act. PEBs were meant to involve distinguished persons, reporting on who is being unreasonable, in order to apply public pressure on the recalcitrant party. But they have evolved into something like ad-hoc interest arbitrations, although that is not their intended role under the Act. The RLA provides for voluntary interest arbitration, not mandatory litigation of wages and rules, decided by a panel of arbitrators.

This PEB 250 was pro labor. It didn’t go quite far enough on wages and kicked the can down the road on attendance policy reform. But having failed to play out the process in a boss-friendly political moment in Washington, the carriers totally failed to advance their agenda. To top it off, the Secretary of Labor and even the President himself leaned on the employers to address the operating crafts’ non-monetary concerns. So: tentative agreements averted a major transportation/supply chain disruption.

They care nothing for their workers, and, ironically, don’t give a damn about the shippers that they promised to service when they sought support for their mega-mergers. It is symptomatic of finance-driven late capitalism.

Score sheet: Unions got their friends to drag the railroads, kicking and screaming, to the bargaining table. Carriers got bupkis. Workers didn’t get everything they deserve, but made real gains WHILE DODGING THE MASSIVE CONCESSIONS THAT WOULD HAVE RESULTED IF THE RAILROADS WOULD HAVE DELAYED THE PROCESS LONG ENOUGH TO HAVE REPUBLICANS SITTING AT THE VETO POINTS.

This is a huge win. It is time to say “Yes!’, ratify, and celebrate!

But. (There is always a but!) The abusive nature of the railroads has so inflamed worker sentiments that there is a real desire to strike, to get more. The carriers are essentially monopolies that are seeking monopoly rents. They care nothing for their workers, and, ironically, don’t give a damn about the shippers that they promised to service when they sought support for their mega-mergers. It is symptomatic of finance-driven late capitalism.

I’ve led successful strikes, but I’ve also seen my wife replaced by scabs, in a lost strike in the early 1980’s. Strikes are valuable weapons in our arsenal. To be successful, they need to be part of a strategy grounded in concrete analysis of concrete conditions. Done right, they should be based on extensive planning, including structure tests to build and assess member support, participation, and resolve. If mishandled, they can lead to a panic and rout. Strikes are not to be trifled with. You deploy powerful weapons carefully.

So, if the ratifications fail, and we’re out on strike: What happens on Day 2? Day 3? What is the plan? Not to blow off steam, but to move the needle, back at the bargaining table? Will Congress get involved? If so, with a split Senate what mischief will the friends of the bosses play? Does resolution get pushed back to 2023?

We don’t know. I don’t want to find out.

Right now, there are some people urging a ‘no’ vote on ratification. Internet revolutionaries that have never organized a worker or actually led a successful strike manage to show up, play on members’ anger and frustration, and call for rejection and strike. But they offer nothing but magical thinking in how that might translate to a better deal. Check it out: One sect is openly seeking the destruction of the unions, to be replaced by non-existent “rank-and-file committees”. Another website urges a ‘no’ vote. Their agenda? Agnostic on who to support in the 2016 and 2020 elections, saying there was no real difference between the parties, they are promoting yet another dead-end third-party effort. They are offended that Biden acted to prevent a strike. Of course he did! The threat of a strike applies pressure for a deal, and a deal makes a strike unnecessary.

Who else wants you to vote ‘no’? Industry pundit Frank Wilner has been bellyaching that the NMB released the parties too soon, before the November election. (Yes, Frank, we screwed up the carriers’ plan!) In his Railway Age column, he features remarks of Mark Mix, president of the National Right to Work Committee, that long-time enemy of the organized labor movement. Mix opines that, even if the tentative agreements are rejected by the membership, the union leaderships may impose it anyway. How touching, that he would suddenly show up, just now, to fan rank-and-file suspicions. No, they don’t come out and say ‘vote no’, but they clearly relish the disruption failed ratifications could cause.

These people have their own agendas. The ultra”left” winds up in an unholy alignment with the ultra-right and the bosses. When people tell you who they are, believe them…

Take the win. Ratify. A system that can be manipulated by the railroads to allow them to avoid serious give-and-take bargaining and, if the political winds blow their way, to transfer wealth from the workforce to their bloated coffers is not one that should go unchallenged. That is a heavy lift that should be, must be addressed. But a strike, now, won’t advance the ball, and runs the risk that the rail bosses will get a do-over.

You won. You deserve it, and more. And think about thinking strategically: how best to approach the next round? First identify the sources of the problem. Then, consider how we might work to reform a system that the railroads have held onto for decades because they often got politicians to give them labor concessions, concessions they can’t win at the bargaining table. You don’t have to be an elected officer to think about the big picture!

In Solidarity – Bill Bon

…

Long Live Jeff Perry

By Gene Bruskin

Jeffrey B. Perry died this morning, Sept 24th at around 8am.

For 58 years Jeff was one of my closest friends. The intertwining of our lives from our first meeting is most remarkable.

My memory, part imagination, was wandering around the Princeton campus on the first day of my freshman year in 1964, feeling lost and totally out of place and walking right into Jeff.

That instant “collision”, turned into an instant connection – two working class guys at Princeton on basketball scholarships feeling alone. We traveled a long way since then, together, in parallel, mutually inspired, in solidarity, in touch, buddies, changing and challenging, in each other’s corner, on the phone, on the streets of Manhattan, always within reach. You couldn’t help but like Jeff, love Jeff. He had that type of charm and genuineness.

Now he is gone—but his life and work touched so many I couldn’t even begin to do that justice.

But I do know how he touched mine.

We struggled with our basketball careers and our studies at Princeton, eventually both transformed by the winds of change in the 60s as the counterculture and the anti-war movement seeped into us both and began to radicalize us.

We both majored in Psychology; I think it seemed like an easier major than the sciences.

We hitchhiked to Vassar and other women’s colleges, desperate, but unsuccessful, at meeting someone, to bring to all male Princeton for a weekend date, like all the prep school guys seemed to be doing

We worked at Camp Tonset on Cape Cod the summer of 1966 as counselors, and with Jeff’s encouragement, I made an unsuccessful (at first) attempt to pick up a beautiful woman on the beach who would eventually become my first wife.

We joined SDS our senior year, I think Jeff signed up first, and marched against the war in our first demo, in Newark.

While I taught in the South Bronx in 1968 to avoid the draft, I remember Jeff leaving the country and somehow, in Che style, hitching around South America for several months.

By the fall of 1969 Jeff was selling the Liberated Guardian on the streets of New York and visiting me regularly at my apartment on 190th St. in Manhattan. Jeff landed in Hoboken working with the Puerto Rican socialist party. We kept moving left, together.

In this tumultuous “Ocean Hill Brownsville” era in NYC, Jeff helped me figure out how to navigate the heated-up city politics surrounding the union strikes, antisemitism, race and class. Then, as I struggled in my second year of teaching, he gave me some clear advice that once again changed my life:

“Gene’” he said, after spending a day in my classroom at a neglected elementary school filled with poor and wonderful children of color, “You are part of the oppressive system by teaching here. This school is not here for learning – just for keeping these kids off the streets. You are losing the battle to be useful and helpful. (I had actually slapped a kid on the head for misbehaving, only to find that one of his parents had shot the other that morning). “You need to quit.”

Boom. It hit me in the gut – he was right. I quit shortly after that.

Jeff then had an answer to my next question: Now what? The draft was looming. “Come with me to Cuba on the March 1970 Venceremos Brigade to cut sugar cane in solidarity during ‘The Year of the Ten Million Tons.” While you are there send them postcards every day – they have to put them in your file and won’t want you after that.”

Going to Cuba changed the political trajectory of my life. We were exposed to revolutionaries from Africa, Vietnam, Uruguay and beyond, including meeting with Fidel. Our commitment to socialism and internationalism were permanently solidified.

Meanwhile, if I remember correctly, Jeff avoided the draft by disrupting his induction ceremony, jumping up and yelling about the war and handing out literature in support of the NLF.

Somehow in the 70s Jeff managed to get into the Harvard Ed school but left because of the elitism and liberal hypocrisy.

After that Jeff started working at the giant bulk mail center in Jersey City and became part of the historic wildcat national postal strike in 1978. He launched a 33-year career in the National Postal Mail handlers Union (NPMHU).

While his scholarly work was emerging, he stayed with Local 300 and by 1989 was part of a Black-led national rank and file insurgency to take over the union. (Part of LIUNA, the Laborers Union).

Not satisfied with helping to build a strong anti-racist rank and file local as Secretary Treasurer, Jeff was on an continuous mission to publicly expose the corrupt president and leader of LIUNA, Anthony Fosco, a man very few people ever choose to challenge.

Once again, Jeff changed my life, convincing the new NPMHU national leadership to hire me and my good friend Bill Fletcher to build a contract campaign for the 1990 national postal negotiations. That brought me to DC which led to many other jobs organizing with national unions, and became my home until today.

Backing up to the late 70s and eighties, while working part time at the “Bulk” as it was called, Jeff remarkably got his PHD at Columbia. During this period, he built a close relationship with Theodore Allen and invited me into Ted’s world, again a life-changing event for me.

Ted was a working-class self-educated scholar, former WV miner and union leader, who spent decades developing his research that led to the monumental, pioneering two-volume work on The Invention of the White Race. He broke new ground, starting in the 60’s, with a deep understanding of white skin privilege from a class perspective and the origin and centrality of white supremacy in understanding the history of the US working class. Knowing and loving Ted, a sweet and unpretentious man, changed my life and forever enriched my understanding of the profound connection between race and class.

When Ted died in 2005, Jeff became the executor of his works and his tireless efforts got Ted’s extensive writings out deep into the world, and his papers placed at the University of Mass, Amherst archives; appropriately, where WEB Dubois archives are preserved. (Here’s a link to Jeff Perry’s Stansbury Forum piece Ted Allen’s work: Theodore W. Allen’s Work On Centrality of Struggle Against White Supremacy Growing in Importance on 98th Anniversary of His Birth)

While at Columbia Jeff discovered the under-appreciated voice of Hubert Harrison, a brilliant early 20th century Caribbean-born writer and leader, known in his day as the Father of Harlem Radicalism, who electrified NYC during his short life. Harrison’s brilliant insights into the connections between race and class went unnoticed by history until Jeff decided to make it his life mission to find out about him and tell the world. He worked on this project until he died after completing a groundbreaking two volume work on Harrison’s remarkable life and ideas in 2021.

Not surprisingly, Jeff remained an internationalist and went with me and others in 1988 on a labor delegation to the West Bank sponsored by the Arab American Anti-Discrimination Committee. We returned and gave testimony to the Commerce Department challenging the GSP (trade preferences) given to Israel due to the extensive labor violations against Palestinian workers and trade unions. The images of Palestinians and their mistreatment by Israeli authorities were seared into our minds forever.

To say that Jeff was a central player in my life is an understatement of an understatement. One other crowning joint achievement happened in 1994 when Jeff and his wife Becky adopted their daughter Perri from China and my wife Evie and I followed shortly, adopting our daughter Nadja from Russia. Both girls were four years old. Being a father was a huge addition to both of our lives and Jeff spent decades, until his death, committed to his wonderful wife, Becky Hom while Evie and I have loved and lived our lives together to this day.

Jeff was a glorious model of a human beings. Not a man without flaws, but a man with great passion, intelligence, determination, caring, humility, generosity, and an unwavering drive toward justice. Those wishing to honor Jeff need only to read his works on Harrison and those of Jeff’s mentor Theodore Allen and follow the powerful insights they contain to help guide our struggle.

There is a song (by ‘Just Keith and Evelyn’) “May the work I’ve done speak for me.” I would add about Jeff, “May the life I have led speak for me”

Jeff Perry has passed. Long live Jeff Perry.

…

Historic. Irrelevant? Sunday’s Italian Election

By Matt Hancock

On September 25 Italians go to the polls to elect a new parliament, following the collapse of Mario Draghi’s “government of national unity.” Polls point to two alarming results:

– The victory of a rightwing coalition led by the Brothers of Italy (literally the direct descendant of Mussolini’s “National Fascist Party”); and

– Levels of abstention never before seen in Italian democracy. In fact, many journalists speak of abstention as the true “victor” in the upcoming elections.

How did we get here?

Clean Hands

The context for understanding what’s happening today has to be “Tangentopoli” (Bribesville) and the consequent collapse of the mass parties that dominated Italian politics since the enactment of the modern Italian constitution. For all of their faults, the Christian Democratic Party, the Italian Communist Party and the Socialist Party inspired millions of ordinary Italians, involving them in the construction of a new society. These parties did not chase public opinion, but rather represented a political home for ordinary Italians (and of course in the case of the Christian Democrats and—later—the Socialists also for elites) that engaged millions in the construction of public opinion and an agenda that was translated—for better or worse—into the work of successive governments.

Inherently unstable, this is the system that nonetheless created one of the world’s highest union densities, an economic miracle, the strongest cooperative movement in the world, a workers’ bill of rights second-to-none, a national health system that, in certain regions to this day, produces some of the best outcomes in the world.

Organized into mass parties, ordinary Italians were not just voters, they were participants in the construction of their new society. That all ended in 1992 when activist prosecutors uncovered an elaborate system of bribery involving politicians, members of parliament, ex-prime ministers and members of the judiciary. Between 1992 and 1996 in the famous “mani pulite” (clean hands) trials, judges investigated and prosecuted thousands. Some committed suicide in prison awaiting trial. Others, like Socialist Party leader Bettino Craxi, fled to Tunisia where he died in 2000.

In the wake of this earthquake, new parties emerged on the national stage, like the separatist “Northern League” which went from receiving less than 1% of the vote to over 8% following the initial arrests. Most famously, billionaire entrepreneur Silvio Berlusconi created his “Forza Italia” (“Go Italy”) party which would come to dominate Italian politics in the 90s and 2000s, ushering in a new era of personality and media-driven politics. One of the results of this tumult was to fuel distrust in politics and political institutions, a deep cynicism among average Italians in government and the institutions of the state, which paved the way for the appeal of anti-establishment parties, like the “Northern League”, the “Five Star Movement” and, today, the post-fascist “Brothers of Italy”.

Vaffa!

Beppe Grillo is a George Carlin-esque, highly popular Italian comedian. His comedy revolves around denouncing the absurdities of Italian bureaucracy and economic and political elites. He was most famous for his punchline “vaffa” (literally “f you”) with which he would liquidate members of the elite through his comedic routine. In the mid 2000s, Grillo began encouraging like-minded Italians to run for office. In 2009, in a move derided by party leaders as a mere provocation, Grillo attempted to join the “Democratic Party” (PD) and run in their primaries. The PD’s then leader, Piero Fassino, infamously said “if Grillo wants to get into politics, he should start his own party, run for office and then let’s see how many votes he gets.”

Following the PD’s refusal to let him join, Grillo officially founded the “Five Star Movement” (M5S), based on the five cardinal points of connectivity, environment, water, development, and transportation. The party, often described as populist, was essentially progressive and anti-establishment, committed to direct participation of its members via a blog and online voting platform. In reality, the party is rigidly controlled by Grillo whose punchline “vaffa” became the semi-official slogan of the party. The M5S attracted thousands of young and disaffected voters, including many older voters from the left, who saw the PD move further and further away from an unabashed pro-worker, left agenda.

In 2013, the M5S participated in parliamentary elections—independent of any coalition on the right or left—and garnered just over 25% of the vote, edging out the PD by just over 1/10th of a percent. (Talk about instant karma.) That year they elected 109 members of parliament and 54 senators. Luigi Di Maio, “political leader” of the M5S, then 26, became the youngest ever vice president of parliament. Following Matteo Renzi’s hostile takeover of the PD in 2014 and his party’s hard right turn, the M5S chose to remain in the opposition.

In the 2018 parliamentary elections the M5S won in a landslide, beating all expectations, and obtaining over 32% of the vote to become the top-voted party in Italy. The M5S did so well that year that they won more seats in parliament than they had candidates for. (To resolve this dilemma Italy’s Supreme Court assigned party members to empty seats in parliament, one of whom became the much derided minister of education.) Many factors account for the unexpected M5S victory, including being the only party that could legitimately claim to be anti-establishment, their focus on an internal process of direct democracy through online discussion and voting which at least created the illusion of popular sovereignty. They also were advocates of broadly popular policies, including a swift transition to a 100% renewable energy economy and the “citizenship wage” — a type of universal basic income for the long-term jobless. This last policy was highly popular in the south of Italy and is often credited as the single reason for their unexpected performance in that year’s election.

On the right, the coalition of right parties won 37% of the vote, this time with the “Northern League” the top coalition partner, with 17% of the vote. (By the 2018 elections the party had dropped “Northern” from its name to become the “League,” in an opportunistic and effective move to appeal to voters in the South, as the party shifted the focus of its racism from southern Italians to immigrants). The center-left coalition led by the PD won just 23% of the vote. These numbers meant that the Five Star Movement was in the driver’s seat for the formation of the new government.

While the most obvious coalition partner in 2018 for the M5S would have been the “Democratic Party” (PD), mutual distrust prevented this from happening and the M5S entered into a “governing contract” (a term invented by the M5S to justify the move) with the right-wing League who’s anti-immigrant, pro (Italian) worker discourse obscures a fundamentally neo-liberal platform (flat tax, less regulation, etc.). At that time the “League”, led by racist, anti-immigrant Matteo Salvini, commanded over 17% of the vote, while the post-Fascist Brothers of Italy amounted to a paltry 4%.

The early days of the “yellow-green” government, headed by the improbable and completely unknown law professor Giuseppe Conte (who termed himself “the people’s lawyer”) included the introduction of the citizenship wage after which the M5S announced, while uncorking a bottle of champagne, “the abolishment of poverty;” while Matteo Salvini, the leader of the “League” and then Minister of the Interior, promulgated a set of “security decrees” and refused to allow boats carrying sick and starving refugees from docking at Italian ports (a move that has landed him in court on charges of kidnapping; that case is ongoing).

Matteo Salvini, in a Mussolini-esque move, sought “full powers” as minister of the interior to combat Italy’s real and imagined threats. This precipitated the fall of the yellow-green coalition and convinced the center-left that it was in their, and Italy’s, interest to form a government with the problematic M5S. This gave rise to the second government headed by Giuseppe Conte, this time termed the red-yellow government. This government, which included the M5S, the “Democratic Party”, former prime minister Matteo Renzi’s breakaway “Italy Alive” party (essentially a neo-liberal party for young members of the PMC), along with minor left parties like Article One and the Italian Left.

In many ways the red-yellow government was remarkable, especially given the instability, inexperience, and immaturity of the M5S: they made legitimate efforts to combat abuses against farmworkers (conditions that often amount to modern day slavery) and led Italy’s initial reaction to the Covid-19 pandemic, intervening with redistributive policies aimed at supporting employment, wages and families, including a ban on layoffs during the pandemic. Most remarkable was Giuseppe Conte’s leadership within in the EU. Conte succeeded in convincing the EU’s fiscal hawks to create a Covid-19 rescue package for member states, backed by debt issued in common by all EU member states (a first in the supra-national body’s history), which included a mix of debt and grant financing to help EU member states recover from the impact of Covid 19 through investments like funding for healthcare and the green transition. Receiving these funds was not predicated on more austerity measures.

Also significant was the experimentation that the “Conte 2” government led to on the local and regional level in the form of the construction of broad alliances among the M5S, Democrats and minor left parties in municipal and regional elections: a model that members of “Article 1” and the Italian Left had fought for and saw as a type of 21st century popular front, capable of limiting the right and advancing pro-worker, pro-environment redistributive politics.

Conte’s government was perhaps too family and worker-friendly for Italy’s ruling class. In the winter of 2019 Matteo Renzi, whose miniscule “Italy Alive” party commands just enough votes in parliament to make a government fall, began to warn of Giuseppe Conte’s unsuitability to administer the EU rescue package (despite his deftness in negotiating the passage of the historic aid package). Conte’s detractors warned that keeping him in power meant risking access to the 222 billion euros Italy was entitled to under the EUs post-Covid recovery package. On January 26, 2021 Giuseppe Conte tendered his resignation, marking the end of the red-yellow government and what “Sinistra Italiana” leader Nicola Fratoinni deemed an “experiment” at “dialogue between north and south, between the productive forces and the world of work, a coming together between those in need of protection and those that can offer it during the difficult crisis, that is between public institutions and politics as service.”

Super Mario

Long before Conte tendered his resignation, the name Mario Draghi was being tossed around in the halls of power as an appropriate replacement. Super Mario, as he was called after his famous declaration that under his leadership the European Central Bank would do “whatever it takes” to save the Euro following the subprime crisis, was seen by his supporters as someone with an impeccable reputation in Europe and throughout the world, someone who commanded respect and enjoyed the kind of reputation needed to guide Italy in the spending its portion of the recovery package. Most of all it was Draghi’s credibility in the halls of power that appealed to his supporters. As if to prove his supporters right, the cost of Italian debt plummeted after Draghi formed his government.

Draghi was chosen to serve as prime minister by Italian president (the head of state, elected by parliament) Mattarella, on the condition that he could form a government of national unity. Draghi was sworn in on February 17, 2021, supported by a broad coalition of nearly all the major parties, from the right to the left. It was unclear whether or not Beppe Grillo would be able to convince his M5S to support this new, clearly establishment government. In the end, the Genovese comedian was able to convince party militants to support Draghi by assuring them that Draghi would create a “super ministry” to guide the green transition (he would end up doing nothing of the sort), and through the use of manipulative wording in an online referendum to garner support among party members.

In a politically deft move, Giorgia Meloni, leader of the post-Fascist “Brothers of Italy Party”, chose not to support the new government—a move that would earn her significant credibility among anti-establishment voters and rocket her party to number one in the polls. Members of the Italian Left decided as a party to urge its members of parliament to vote against the new Draghi government. Fratoiannia, SI’s leader, eloquently argued that the threat of an authoritarian turn had subsided after the fall of the M5S-League government and that the Draghi government, which objectively represented a shift to the right at least in terms of the ministers he chose, amounted to a “restoration” following the prior government’s attempts at introducing more boldly redistributive policies. The best role for the left was to oppose such a government. (In practice, individual SI MPs voted to support the new Draghi government, arguing they could best influence the shape of the government from the inside rather than from outside.) “Article 1”, the other notable left formation in parliament, chose to support the new Draghi government. Matteo Renzi gloated that Italians happy with Mario Draghi as Prime Minister should thank him.

Initially, Mario Draghi enjoyed widespread support, with a majority of Italians viewing him favorably. Markets rewarded Italy by lowering the cost of its public debt, and Draghi began to carry out a series of reforms required in order to receive Italy’s portion of the EU recovery funds. Draghi was so popular initially that members of his governing coalition, especially the PD, seemed to be vying for the spot of “party most supportive of Draghi.”

Both Draghi’s supporters and detractors seemed to be correct about him: Italy gained from his reputation within the EU, and he was successful in pushing through some difficult reforms. At the same time, his government did represent a shift to the right: key posts influencing the economy and labor relations (the ministries for public administration, economic development and tourism) were occupied by politicians from the Italian right, while the highest profile position given to a labour-left party (“Article 1”) meant the left’s most visible role was to require Italians to get vaccinated, wear masks, and quarantine if you came into contact with someone with Covid.

The Draghi government was to have been a “technical” (as opposed to political) government. But even the “technicians” appointed to important positions, for example the Ministry for the Green Transition (what Beppe Grillo promised members of his party would be a “super ministry”) was highly political: Roberto Cingolani, a physicist-entrepreneur and former Ferrari board member, has been a staunch opponent of EU efforts to transition away from fossil fuels, advocating specifically for carve-outs for Italian luxury automakers like Ferrari. His detractors have named him CingolEni (Eni being the main Italian oil company). The PD received the post of Labor Ministry but has been unable, despite the minister’s best intentions, to achieve much for labor in concrete policy terms. Under the Draghi government unions found the door closed on consultations, and key reforms like a reform of Italy’s tax system provided more relief to the wealthy than to working people. The green transition, if stalled prior to Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, is now moving in reverse, with efforts underway to increase the use of coal to produce energy domestically, expanded drilling off Italy’s coasts and increased imports of petrol products to prevent rationing in the winter. Meanwhile, the government has made no progress in easing up on regulations that make large-scale solar and wind projects costly and time consuming.

Government of National (dis)Unity

On July 21, 2022 Mario Draghi tendered his resignation, unable to garner enough support to keep his government of national unity together. The Draghi government’s crisis was sparked by the M5S’s leader, former prime minister Giuseppe Conte. Conte was responding to internal pressures following the high profile split from the party by Luigi Di Maio, who took with him 51 members of parliament, to form a competing party, “Together for the Future”. Conte then met with Draghi, on July 6, to announce nine policies which constituted the conditions which the M5S required to continue to support Draghi, conditions which Draghi refused. The “Northern League” seized on Conte’s move to demand the formation of a new government with all the same parties, but excluding the M5S, a move that Draghi refused on the grounds it was inconsistent with his mandate from President Mattarella (the M5S is after all the largest single bloc in parliament).

It Pays to Yell from the Sidelines

A quick look at the latest polling might explain the behavior of both the M5S and the “Northern League” in precipitating the crisis: participation in government, despite Draghi’s high approval ratings, has not translated into better polling for parties in the governing coalition. The M5S has seen their support drop to just under 14% (recall in 2018 they won 32% of the vote), and the “Northern League’s” support has fallen to 11%.

Meanwhile “Brothers of Italy”, who have remained in opposition since 2018 and became vocal opponents of the widely loved Mario Draghi, are now polling above all other political parties at 24.6%. While the rest of the world seems to be worrying about her roots in Italy’s post-fascist political movements, Italians seem far less worried: 36% of Italians report trusting her, while only 23% say they trust Enrico Letta, the leader of the PD. At a recent conference, the Meeting in Rimini sponsored by the mainstream Catholic movement Communion and Liberation (an event considered a bellwether of Catholic voter sentiment), the only politician to receive a standing ovation was Giorgia Meloni.

The “Democratic Party”, which had tried to position itself as the party most faithful to the “Draghi agenda,” has not benefited from the Prime Minister’s coattails nearly as much as Meloni has through her opposition: the latest polls place the PD at 22.6% (compared to the 18.7% of the vote they received in the 2018 parliamentary elections).

Finally, from the Right’s position there was not much downside to precipitating the government’s fall: while the center-left is fragmented (more on that later) the center-right will participate in the upcoming elections as a coalition, polling at over 40%.

So, Now What?

The State of Play

Initially, few expected the drama of the summer to lead to early elections. Italians, in their history, have rarely voted in the fall since the summer is a time when most tune out and turn off the television, making a summer electoral campaign highly problematic. There is also the fact that normal elections would have been held in the spring of 2023, in just a few months. In fact, when Draghi initially tendered his resignation, President Mattarella refused to accept it, asking him instead to try and patch together another government of national unity, on the hope that his government could last until the regular elections in 2023, to continue to push through the reforms necessary to receive the EU Recovery funding, and to begin to spend that funding. Neither the M5S nor the “League” seem to have shared Mattarella’s concerns.

From the very beginning, Giorgia Meloni was the frontrunner as next prime minister, given her unusually high approval ratings for a post-Fascist, and the fact that years of opposition and deft maneuvering to make her seem more mainstream and moderate to those outside of her core of support had propelled her party to number one. The center-right, despite being split over supporting the Draghi government of national unity, remained highly coordinated throughout and will present itself in the elections as a coalition. This is important, since the current electoral law combines proportional voting with winner-take-all, and this ensures that in the winner-take-all elections, the right doesn’t dilute its vote.

On the other hand, the center-left has never been more divided, with the “Democratic Party” essentially running alone, against the M5S, a united right, and an extreme left grouping. This despite years of careful work, in municipalities and in the regions, to create a broad, “popular front” grounded in the alliance between the “Democratic Party” and the M5S. This strategy produced, in the recent municipal elections in Bologna for example, a city council that included the Democrats, M5S and the leftwing formation “civic coalition,” which had prior to 2021 acted as a left-opposition to the majority within city government. Proponents of this strategy saw this as the best way to block the right and advance a progressive agenda throughout Italy.

When the M5S decided to no longer support the Draghi government, the PD announced it would not run in the elections in coalition with the M5S. Giuseppe Conte counter-attacked by announcing days, before regional primary elections to determine the center-left candidate for governor in Sicily, that the M5S would no longer support the winner of those elections and instead would run on their own against the PD. The PD reacted by taking the M5S to court for violation of contract. As a result, the two single biggest parties on the center left are running against each other in the September 25 elections.

Following the PD-M5S split, PD party leader Enrico Letta began a series of public negotiations with Carlo Calenda, the leader of the party “Azione” (yes, that’s what it means: “action.”), to run in partnership in the upcoming elections. Calenda, a protege of businessman Luca Cordero di Montezemolo best known perhaps as the former president of Ferrari, had served in various roles in different governments, including as Minister for Economic Development where he won wide praise for his policies to encourage the adoption of “Industry 4.0” technologies in the Italian economy. At the time of negotiations with the PD, Calenda’s party was barely polling above the threshold to win a single seat in parliament. Days after negotiating an agreement wtih Azione, Letta also negotiated an agreement with the Greens and the Italian Left (who had not supported the Draghi government). Following this opening to the left, Calenda publicly announced he was backing out of the deal with the PD, on the grounds that the opening to the left would lead to an alliance with the M5S, and within days had formed an alliance with Matteo Renzi’s “Italy Alive” party. They called it the birth of the “third pole.” Not right, not left, but center. (Calenda has since publicly spoken of the idea of a new “government of national unity” including his party and the post-fascist Brothers of Italy, while his partner, Matteo Renzi, is promising voters that a vote for their coalition is a vote to return Mario Draghi as prime minister.)

“Article 1”, the group that broke away from the PD following Matteo Renzi’s rise, which is likely in the process of rejoining the Democrats will run on the democratic party ticket.

To the extreme left there is “Unione Populare” (Popular Union), an attempt to combine forces among smaller left parties. But it is unlikely that UP will garner enough votes to be assigned any seats in parliament.

So What’s the Big Deal?

The divisions on the center-left would not matter so much if Italy had a purely proportional system. Everyone runs for office, and you get the number of seats that correspond to the percentage of the vote you received. Then after the election we can form a government. But Italy doesn’t have a purely proportional system.

The current electoral law, just like the one before it, was written to benefit the parties in power, and assigns 60% of the seats in parliament on a proportional basis, and 40% of the seats based on winner-take-all. This means that different parties must run on the same “list” (as is the case with the breakaway Labor-party Article 1 and the PD) or at least have an agreement not to run against each other (as in the agreement with the Greens and the Italian left).

Americans will immediately understand the bind that thoughtful, left voters are in: if I vote for a candidate or party whose values I prefer, but that is not in coalition with or have a formal agreement with the Democrats, I risk splitting the vote and turning the winner-take-all districts over to the right wing. At a minimum, this means running the risk of giving the right a significant enough majority that the next government could last the full five-year term. But if the right, through outperforming in the winner-take-all districts, is able to win a super-majority, that means that they can pass constitutional reforms on their own. Top on their list of reforms: the merging of the head of state and head of government through direct, irrevocable, popular election of the president.

On the Left

Disaster is certainly an appropriate term for the state of the left. The two biggest progressive parties, the PD and the M5S, are at war with each other. And the PD is running a campaign focused on abstract ideas that appeal to a narrow portion of the electorate (“more discrimination or equal rights,” “fossil fuels or renewable energy”). Enrico Letta, the PD’s leader, is fond of talking about his party being the only thing that can stop Italy from becoming like Hungary; an odd campaign premise considering that his Orban-friendly opponent, Meloni, is far more trusted by Italians than he is.

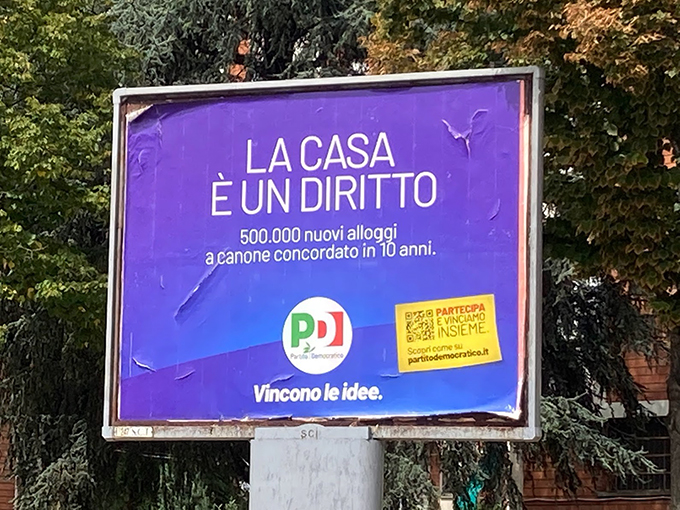

The right’s messaging, instead, is much clearer and more straightforward, speaking in concrete terms about how they will defend Italians and Italy from real and imagined threats. A good example of this are two billboards, placed near each other, in Bologna:

- The PD billboard says “Housing is a Right: 500,000 More Affordable Housing Units in 10 Years through Agreed Fee.” (Agreed fee is a process by which the tenants union negotiates rent maximums with the landlords’ union; in exchange for lower rent and better terms to the tenant, the landlord gets a tax benefit. It’s a great system that few voters are likely to know anything about!) “Below the PD logo it reads: Ideas win.”

- The billboard for the League, on the other hand, reads: “No sales tax on bread, pasta, rice, milk, fruits, vegetables. We believe that no Italian should be left behind.”

The extreme left, despite laudable efforts and a solid program, is unlikely to achieve any seats in parliament since they probably won’t meet the minimum threshold. That leaves Article 1 (essentially re-absorbed into the PD) the Greens and Italian Left to carry the banner in parliament. At best they may receive 4-5% of the vote.

Labor appears to be divided as well. The most popular party among working class Italians, at least until recently, has been the League. This should not be too surprising, as the League was born in the industrial, highly unionized northern regions and is the only party that continues to have some semblance of the kind of rootedness in communities once characteristic of the PCI. Among labor activists, there appears to be a split, primarily among those supporting the PD, others supporting the Green-Italian Left coalition, and still others the M5S. Officially the position of labor’s leadership is to remain neutral, while encouraging Italians to vote in droves, and to vote against parties proposing a flat tax and presidential system (i.e., the right).

All of this, of course, is symptomatic of the deeper crisis of representative democracy in Italy and the disconnect between Italy’s popular classes, their movements, and electoral politics.

Conclusion

Working parents, raising kids in Italy have an extremely long summer. School gets out on June 3 or 4 and doesn’t start up again until September 15. Parents rely on a patchwork of grandparents and summer camps to survive until school starts again. In places like Bologna, despite the attempts of policy makers to make summer camp more affordable through public subsidies, camps can run up to 200 euros a week, for one child. For a family without grandparents nearby that can amount to 1,800 euros or more for the summer, nearly 300 euros more than the average salary. This year, miraculously, my two kids and I survived the summer through a combination of different camps, time off from work and patience and help from loved ones. I don’t know about my kids, but I was counting down the days until September 15. No sooner had my daughter started school than we learned that her school would serve as a polling location for the September 25 elections. To prepare the school for the Sunday polling, they would need to send kids home at 1 PM on Friday September 23. School would remain closed on Monday September 26 to allow workers to remove polling equipment and sanitize the building, with the kids not returning until Tuesday September 27. I’m lucky, because we have grandparents nearby who can help, and as freelancer my work is flexible. But not everyone has the same flexibility and support I do.

One commentator recently wrote that the upcoming elections, which will end up causing actual disruption in my life through the closure of my daughter’s school, are both historic and irrelevant. The elections are certainly historic: they are the first to occur after a popular referendum slashed the number of seats in parliament and happen at a time when war rages in Europe, poverty and inequality increase, the climate crisis deepens, and we continue to face a global pandemic.

The elections are also historic because, for the first time since Italy’s liberation from Nazi-Fascist occupation, the party that is the direct descendent of Mussolini’s Fascist Party is the frontrunner. Of course, the historic conditions that gave rise to Mussolini are today absent (his rise was preceded by two years of terroristic attacks on the Left and sieges of cities by fascist squads while the liberal government and state stood by and did nothing) and the threat of actual Fascism is low. However, the relative wide popularity of Meloni is troubling. It is an indication of the distress of ordinary Italians, the level of comfort among a portion of elites for a post-Fascist party, and the increasing distance in time and spirit of the Italian people from the memory of the anti-Fascist resistance.