“Because we can, so we should.”

By Peter Tappeiner

“You can withstand. You will overcome. You will have the voice you need and deserve. You will inspire workers across this country.” Fred Ross, Jr.

I’ve been moved by the wonderful remembrances and tributes to Fred Ross, Jr. As one of many people transformed by Fred during his 50-year career in movements for justice, I remain in awe of the scope and depth of his work. But as any organizer knows, those 50 years are made of daily interactions with other organizers and people struggling to make their jobs, lives, and our world better. I’m sharing my story about working with Fred in an effort to honor what he taught me and some of what I believe Fred’s life and work has to teach all of us.

Fred was an organizer’s organizer. He approached this work with rigor, joy, passion and an unwavering belief in people and our ability to do incredible, seemingly impossible things.

In my time as organizer at SEIU Local 250 and then SEIU United Healthcare Workers – West, I had the joy of working with Fred from 2004 through 2009. I also had the privilege of being led by him throughout 2006, 2007 and 2008.

Fred and I (along with many others) worked together with workers from Santa Rosa Memorial Hospital (“Memorial”) and workers from other Catholic hospitals around California that were part of the Saint Joseph Health System (SJHS). SJHS was the only non-union statewide hospital system in California. I was 22 years old and less than six months into my career as an organizer when I first met with workers from Memorial. In 2004, workers at Memorial had filed for an election to join Local 250 but made the difficult decision to withdraw that petition in early 2005 in the face of a vicious anti-union campaign.

After cancelling the election, we quickly moved to begin a campaign calling on Memorial to agree to ground rules for a free and fair election, like California’s largest Catholic hospital system, Catholic Healthcare West, had done a few years prior.

The campaign became part of a national effort by SEIU to hold Catholic hospital systems to the Church’s stated values and to refrain from the standard anti-union tactics common in any contested organizing drive. We believed that victory was possible at Memorial and SJHS in part because the Sisters of Saint Joseph of Orange – the otherwise progressive order who founded the hospitals – still had a majority of seats on the corporate board and the Sisters had demonstrated their willingness to overrule the lay corporate leadership.

By the time I began working with Fred, I was a green Lead Organizer, responsible for leading a team of other organizers and the day-to-day activities of the campaign. For four years workers at Memorial, undertook a campaign of escalating public actions aimed at building an ever-growing chorus of voices important to the sisters. Eventually Memorial workers were joined by other SJHS hospitals in Northern California and Orange County (Southern California) in demonstrating workers’ unrelenting demand for a voice at work and a fair process for organizing.

Fred took his role as a trainer and mentor as seriously as anyone I’ve ever worked with. Even at the time, it was clear to me that he deeply felt the responsibility of training the next generation of organizers. At each of our – at least weekly – one-on-one meetings, Fred would sit down with his omnipresent yellow legal pad, and I would glance with no small amount anxiety at the list of items we had to discuss in each meeting. That list seemed to get longer every week. (Now that I’ve spent 20 years working in the labor movement, I’ve learned that list never stops getting longer.)

Because he believed in our campaign, and my ability to lead a piece of it, Fred had high expectations of me. I remember my first time leading a meeting of our organizing committee. I had written an agenda that probably wasn’t very good and sent it to Fred. Late into the evening Fred spent over an hour walking me through changes. He was clear about the changes he thought were important; but led me through that conversation by not just telling me what to do, but by interrogating and challenging me to come up with something that met the needs of the campaign.

Fred had similarly high expectations of what the worker leaders who made up the organizing committee were capable of and was equally invested in their development. In any long campaign it’s normal for a certain amount of fatigue to set in, so we were constantly strategizing with workers at Memorial about how to reinspire and motivate their coworkers.

By the fall of 2007, workers had organizing committees in the three Orange County hospitals as well as Santa Rosa and Petaluma and we were planning two consecutive weekends of marches to the hospitals, calling on SJHS to agree to a free and fair election. To ensure strong participation, Fred suggested a series of house meetings led by the committee. I would learn this was classic Fred Ross, Jr. The organizing committee members would invite coworkers from their department to their homes and lead them through an agenda developed by the committee designed to reground them in why they were organizing, inspire them about the progress we had made, and get their commitment to attend the march in Santa Rosa.

One by one, members of the committee did turnout to their house meetings, led the agenda, and got their coworkers committed to attend this march from downtown Santa Rosa to Memorial Hospital. On that day the energy was electric. The march was led by the Memorial workers and joined by other union hospital workers and community supporters. When we started the march, it was like someone fired a starting pistol. The Memorial workers took off at such a pace that I had to run to the front of the march to slow them down so that the rest of the marchers could catch up.

Fred trusted workers to make decisions and know that their power was key to victory. He knew there was no winning without workers driving the campaign. Early in our time working together we organized a majority of workers at Memorial to sign on to a letter calling for a fair process. I remember Fred telling me about a conversation he had with another senior leader of SEIU who was organizing Catholic hospitals who asked, “Fred, why are you wasting time getting a majority in Santa Rosa?” Fred’s response was simple, “Because we can, so we should.” I came to learn that was an important lesson about the centrality of workers to their own campaign. A view I would learn was not shared by all of Fred’s peers at the SEIU International Union.

“They did what good organizers do best, listen and engage.“

By the summer of 2008 we were ready for another escalation, this time focused directly on the Sisters of Saint Joseph of Orange themselves. To pull off an action directed at an order of nuns would require no small amount of finesse. Fred, with leaders like Glenn Goldstein from our local – by then, SEIU-United Healthcare Workers West – and his organizing partner Eileen Purcell, had spent significant time coming up with an action plan that would strike the right balance of militancy and moral suasion. Drawing on his formative experiences in the United Farm Workers, and echoing Cesar Chavez’s historic fast in 1968, Fred proposed a series of fasts at the different hospitals.

Santa Rosa remained our strongest shop, so we knew for this plan to work, the leaders at Memorial would have to embrace it. On a rainy weekend in late spring, we gathered the top leaders, a committee that had been organizing for five years and were the hardest core of union support in the entire company. After a discussion of the progress we had made and where we saw potential to move the company, Fred laid out the idea for the fast.

It went over like lead balloon. Reactions ranged from uncomfortable silence to incredulity, “you want us to do what?!” Eventually, one of the committee members – a phlebotomist who had been one of the first people to contact the union – said “I’ve been on board with everything we’ve done in this campaign and If we decide to do this, I’ll probably do it, but I don’t think it’s a good idea.”

Fred and the other staff didn’t try to force a fake consensus or ram through a decision. They did what good organizers do best, listen and engage, arriving at a plan to hold a week of action outside the Sisters’ Motherhouse, during an anniversary celebration that would be attended by current and former members of the order, several of whom had become allies of the workers over the preceding years.

The week of action was classic Fred. Exploiting decades of relationships and contacts, Fred enlisted those that would carry weight with the Sisters to join the rallies, vigils, and art projects, and even the evening communion on the sidewalk outside the gates to the Motherhouse.

Then Attorney General (and future Governor) Jerry Brown, National Farmer Worker Ministry founder Chris Hartmire and former UAW leader Paul Schrade all joined workers in calling on the Sisters to return to their values and respect hospital workers’ right to a free and fair election. The week culminated in an enormous march with workers making the trip down from Santa Rosa to join their sisters and brothers in Orange County, well over 400 miles south. The power that workers had built was evident when several weeks later the company reached out to begin negotiations for a fair election in Santa Rosa, that would set a pattern for all 9,000 SJHS employees around the state. Unfortunately, those negotiations would not bear fruit for reasons that would only become clear later.

Simultaneous to this campaign, another campaign was being waged by the Andy Stern lead SEIU against the very local that the SJHS workers were fighting to join: SEIU-United Healthcare Workers – West. Stern’s campaign led to the trusteeship of SEIU-UHW in January of 2009 and the suspension of SEIU’s campaign in Santa Rosa. However, the members and leaders of SEIU-UHW founded a new union – the National Union of Healthcare Workers (NUHW) – to carry on the tradition of militant, democratic unionism that had become impossible inside SEIU.

The workers in Santa Rosa were faced with a choice:

1) Wait and see if SEIU would resume their campaign

2) Stop organizing altogether

3) Organize with NUHW, a newly created union with no members and little to no resources, to take on what would inevitably be a fight with one of the largest unions in the US, as well as the employer who had been fighting us for nearly 6 years.

Many of the same core leaders, committee members who less than a year before had gathered to plan a key escalation in a growing and powerful campaign, met in a common room at the condo complex where one of them lived. They made the hard decision to organize with NUHW. Without the principled leadership of organizers like Fred, I don’t know if they would have felt empowered to make that choice.

While Fred had worked with us at SEIU-UHW on the SJHS campaign, he was employed by SEIU International and had deep relationships with SEIU’s national leadership.

Learning of the SEIU’s betrayal of workers in Santa Rosa and that union’s attacks on UNITE HERE, Fred resigned from the SEIU International in March of 2009 to stand with those who had decided to organize with the NUHW. As Fred would write in a December 2009 letter to Santa Rosa Memorial Hospital workers, as they prepared for an election to join NUHW:

“The tipping point came when I learned in February [2009] that the international union had decided in August 2008 to withdraw support for your campaign. This was at a critical moment. We had conducted our week of action in Orange County in July of that year at the SJHS Motherhouse, and won unprecedented national publicity.

How did I find out that SEIU had withdrawn support for you when you needed it most? Last February, SEIU leaders from Washington took over its California healthcare local, SEIU-UHW. The campaign was suspended. Days later, over 200 SRMH workers were informed of impending layoffs. I offered to fight the layoffs alongside an experienced organizer who had spent two years on the campaign. However, this organizer was told by the new SEIU-UHW leadership, installed by Andy Stern, that SRMH workers were no longer a priority.

Several days later, a national leader of SEIU told me that SEIU could probably get a free and fair election agreement from SJHS by that June. I was shocked by what he admitted next: that the International union made a decision in August 2008 no longer to support workers at SJHS or put pressure on the system, because they did not want you to have the opportunity to vote for a union led by Sal Rosselli. SEIU broke faith and trust with you by deserting you when you most relied on them. This misconduct seriously undermined the opportunity you had to win a fair election agreement with SJHS in the fall of 2008.”

These are painful memories of a deeply ugly time in our movement and part of me is reluctant to share them in what is a celebration of the life and work of someone to whom I owe so much. But I know that Fred was motivated by his abiding faith in our ability to do hard and courageous things when we are called to do so. That lesson of integrity in and dedication to building true popular power is one I hope to live up to in my life and work.

But even in that moment of darkness, Fred ended his letter to Memorial workers on a note of hope:

“Keep your eyes on the prize. You can withstand SJHS’s anti-union campaign. You will overcome SEIU’s campaign of smear, fear and futility. By voting for NUHW, Memorial Employees will have the voice you need and deserve for yourselves and your patients. It will also send a powerful message to SJHS and SEIU and inspire workers in the rest of SJHS and in Catholic hospitals across this country.”

It should come as no surprise to anyone who knew him that Fred’s prediction was right. Workers at Memorial won their election, NUHW: 283, SEIU: 13, No Union: 263. And after lengthy legal delays brought by their employer, they won a first contract in 2012. Workers at three other SJHS hospitals in Northern California went on to organize their union with NUHW.

Looking back at the closing paragraph of Fred’s letter, I see a mantra that defines Fred’s attitude towards every campaign, election, strike or fight for justice. Words that exemplify his belief in workers and everyday people: Keep your eyes on the prize. You can withstand. You will overcome. You will have the voice you need and deserve. You will inspire workers across this country.

FRED ROSS, JR, PRESENTE!

.

Fred’s last campaign was organizing financial support for an upcoming documentary about his father, Fred Ross, Sr. Take a minute to visit www.fredrossproject.org and make a contribution.

A memorial for Fed Ross, Jr. is scheduled for February 26th, 2023 at Delancey Street. Time to be determined. Delancey Street is at: 600 Embarcadero San Francisco, CA 94107.

If you would like to attend, please RSVP to: fredrossjrmemorial@gmail.com

…

“We’re the ones who fill the trucks—so Bezos makes a billion bucks”: Global Actions on Black Friday Unite Workers to ‘Make Amazon Pay’

By Peter Olney and Rand Wilson

Over the last 27 years Amazon has grown from a little-known online bookseller to a global sprawling logistics and delivery empire, overtaking brick-and-mortar retailers with its e-commerce offerings and threatening to make serious inroads on last-mile carriers like FedEx, UPS, and the Postal Service. Recently Amazon even established a virtual health services company: Amazon Clinic.

As the company’s tentacles reach around the world, organizing its massive 1.5 million workforce necessitates new levels of international union cooperation and solidarity.

UNI Global Union, a federation representing logistics and service workers headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland, stepped up for the third year in a row to coordinate worldwide actions on one of the busiest shopping days of the year, Black Friday.

Under the banner of “Make Amazon Pay,” Amazon workers and allies organized 140 industrial actions and protests in 40 countries, with the broadest and most militant actions taking place in France and Germany, where union federations jointly led strikes at 18 warehouses, according to Nick Rudikoff, UNI’s campaigns director.

In Berlin, 100 workers and supporters rallied and used a projector to emblazon an Amazon warehouse with the words, “The wrong Amazon is burning!” The workers in Germany were demanding that the company recognize national collective bargaining agreements with their union, covering retail and the mail-order trade sector.

In Delhi, India, 40 workers went on strike at a new facility. Actions also took place in Australia, Japan, South Africa, and South America.

A DOZEN U.S. ACTIONS

Past Black Friday actions have had little participation from U.S. Amazon workers. However, at the Labor Notes conference in June, workers came together from a range of unions—Teamsters, Postal Workers (APWU), Retail and Department Store Workers (RWDSU), the Amazon Labor Union, Ver.di, Carolina Amazonians United for Solidarity and Empowerment, Amazonians United—and vowed to stay in touch to learn from each other.

The planning paid off: a dozen actions led by U.S. Amazon workers, plus many other community-backed protests supported by the Athena coalition and Good Jobs First, took place on Black Friday.

In Alabama, Amazon workers—joined by Starbucks and mine workers—flyered at the fulfillment center in Bessemer—part of the campaign to keep the organizing momentum alive there, after workers lost a second union authorization election earlier this year, with a narrower margin than the first one (though the results still have to be certified by the Labor Board).

A chapter of Amazonians United in Upper Marlboro, Maryland, reported that they wore Make Amazon Pay stickers with 70 percent participation from fellow workers. Workers and allies protested outside Amazon headquarters in Seattle and Jeff Bezos’s penthouse in New York City; protests at Whole Foods stores were organized by Our Revolution.

STRIKE SNARLED PRODUCTION

The most notable action was in the St. Louis suburb of St. Peters, Missouri, where Amazon workers at the fulfillment center STL8 went on strike to demand safer working conditions and better pay. The strike began with a worker chanting, “Clock out, walk out!” They were joined outside by a large group of community supporters.

“We’re the ones who fill the trucks—so Bezos makes a billion bucks,” workers chanted, referring to Amazon’s founder and executive chairman.

“We need safer work,” said Jennifer Crane, a worker at the facility. “Things don’t need to be this way. Amazon can afford to give us a living wage and to provide us a rate of work that doesn’t lead to injuries or death.”

The walkout had snarled production, according to a screenshot from a manager’s text message on the company app, which read, “Its gonna to be a tough day today across the board. HC [head count] is low.”

The workers are demanding $10-per-hour raises, the removal of a 36-month cap on raises, and an additional $1 per hour for each job employees are cross-trained on. They also called for a worker-led committee to ensure better job accommodations for injured workers.

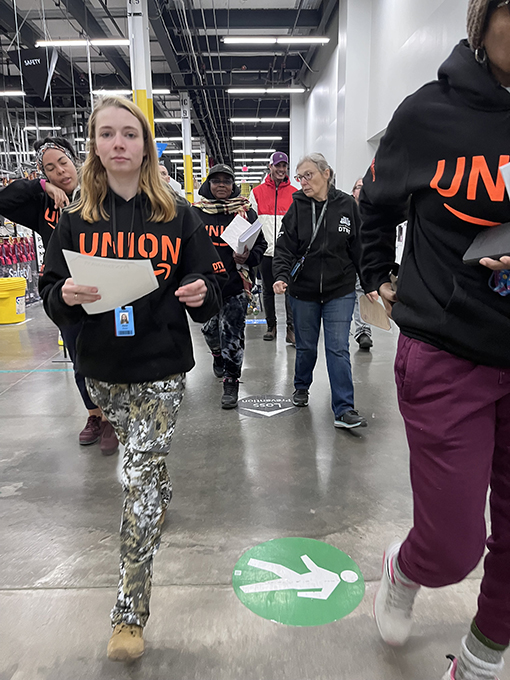

Amazon workers at a fulfillment center in Detroit affiliated with the Postal Workers also staged an action. The “DTW1 YOUnion” organizing committee distributed a special Black Friday edition of its newsletter. Then, wearing bright “UNION” shirts, they marched on the H.R. department with a comprehensive set of demands for better wages and working conditions. Members reported that as they marched, more workers spontaneously joined in.

Since the onset of the pandemic, the price of everything you can imagine has increased,” said Denise Jones, a member of the organizing committee. “The state of our cost of living is soaring! We can barely afford to feed ourselves and our families. Yet we give, we give, we give, and receive little in return.”

PLANNING FOR 2023

While the U.S. participation was still small and uneven, we took a step forward to unite many of the forces organizing at Amazon (unions, nonprofit groups, solidarity union networks). That unity bodes well for nurturing an ecumenical organizing strategy to build Amazon workers’ power.

Each group has its own approach, with some focusing on winning NLRB elections, others on last-mile delivery stations in metro regions, others still on air hubs and fulfillment centers.

Most of the U.S. organizers reported that numerous and more militant Black Friday actions at Amazon worldwide really inspired their co-workers and raised new awareness of the global nature of their work.

Even in Italy, where there were no strikes on Black Friday, there were solidarity assemblies and leafleting in support of the actions taken internationally. The Italians launched the first strike against Amazon in 2017, and their national strike in 2021 got Amazon to adhere to their national collective agreement for warehouse workers.

Planning has already begun for Black Friday 2023, as all parties recognize that organizing Amazon will require the broadest possible forces coordinating their actions nationally and internationally. Logistics workers of the world, unite!

…

This article first appeared in Labor Notes, check them out

Miners for Democracy – 50 years on it’s back to the future

By Steve Early

On December 14, 1972, coal miners rocked the American labor movement by electing three reformers as top officers of the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA), a union which at the time boasted 200,000 members and a culture of workplace militancy without peer.

In national balloting supervised by the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL), Arnold Miller, Mike Trbovich and Harry Patrick ousted an old guard slate headed by W.A. (“Tony”) Boyle, the benighted successor to John L. Lewis, who ran the UMWA in autocratic fashion for 40 years. Boyle’s opponents, who campaigned under the banner of Miners for Democracy (MFD), had never served on the national union staff, executive board, or any major bargaining committee. Instead, 50 years ago they were propelled into office by wildcat strike activity and grassroots organizing around job safety and health issues, including demands for better compensation for black lung disease, which afflicted many underground miners.

Today, at a time when labor militants are again embracing a “rank-and-file strategy” to revitalize unions and change their leadership, the MFD’s unprecedented victory — and its turbulent aftermath — remains relevant and instructive. In the United Auto Workers (UAW), for example, local union activists recently elected to national office — and fellow reformers still contesting for headquarters positions in a runoff that begins January 12 — will face similar challenges overhauling an institution weakened by corruption, cronyism and labor-management cooperation schemes. Some UAW members may doubt the need for maintaining the opposition caucus, Unite All Workers for Democracy (UAWD), that helped reformers get elected, but the MFD experience shows that such political breakthroughs are just the first step in changing a dysfunctional national union.

Imagine what it was like for coal miners in the 1970s to challenge an even more corrupt and deeply entrenched union bureaucracy, with a history of violence and intimidation directed at dissidents. When Joseph (“Jock”) Yablonski, a Boyle critic on the UMWA executive board, tried to mount a reform campaign for the UMWA presidency in 1969, that election was marked by systematic fraud later investigated by the DOL. Soon after losing, Yablonski was fatally shot by union gunmen, along with his wife and daughter, as Mark Bradley recounts in Blood Runs Coal: The Yablonski Murders and the Battle for the United Mine Workers of America.

Just three years later, MFD candidates were able to oust Boyle and his closest allies, but without winning control of the national union executive board. As inspiring as it was at the time, this election victory ended up demonstrating the limitations of reform campaigns for union office when they’re not accompanied by even more difficult efforts to build and sustain rank-and-file organization. Of all the opposition movements influenced by the MFD, in the 1970s and afterwards, only Teamsters for a Democratic Union (TDU) has achieved continuing success as a reform caucus, largely due to its singular focus on membership education, leadership development and collective action around workplace issues.

Contested elections are rare

Then and now, contested elections in which local union leaders — not to mention working members — challenge national union officials are very rare. Rising through the ranks in organized labor generally means waiting your turn, and when you capture a leadership position, holding on to it for as long as you can. Aspiring labor leaders most easily make the transition from local elected positions to appointed national union staff jobs if they conform politically.

Dissidents tend to be passed over for such positions or not even considered unless union patronage is being deployed by those at the top to co-opt actual or potential critics. As appointed staffers move up via the approved route, whether in the field or at union headquarters, they gain broader organizational experience by “working within the system” rather than bucking it.

If they become candidates for higher elective office later in their careers, they enjoy all the advantages of de facto incumbency (by virtue of their full-time positions, greater access to multiple locals and politically helpful headquarters patrons). Only a few national unions — including the UMWA, Teamsters, the NewsGuild/CWA, and now, with inspiring results so far, the UAW—permit all members to vote directly on top officers and executive board members.

Different route to the top

On paper, coal miners long had a “one-member, one-vote” system. But, by the late 1960s, there had not been a real contest for the UMWA presidency in four decades. Lacking the stature of his legendary predecessor John L. Lewis, a founder of the Congress of Industrial Organizations, Tony Boyle had become a compliant tool of the coal industry, unwilling to fight for better contracts or safer working conditions. Increasingly restive miners staged two huge wildcat work-stoppages protesting national agreements negotiated in secret by Boyle (with no membership ratification). In 1969, 45,000 UMWA members joined an unauthorized strike demanding passage of stronger federal mine safety legislation and a black lung benefits program for disabled miners in West Virginia.

Despite passage of the 1959 Landrum-Griffin Act, which created a “bill of rights” for union members, Boyle was able to maintain internal control by putting disloyal local unions and entire UMWA districts under trusteeship, which deprived members of the right to vote on their leaders. Jock Yablonski’s martyrdom set the stage for a rematch with Boyle. It took the form of a government-run election, ordered after a multi-year DOL investigation of violence, intimidation, vote-tampering and misuse of union funds by Boyle’s political machine. The standard bearers for reform in 1972 were Yablonski supporters who created MFD as a formal opposition caucus a few months after his death. They also published a rank-and-file newspaper called The Miners Voice as an alternative to the Boyle-controlled UMW Journal.

At MFD’s first and only convention, 400 miners adopted a 34-point union reform platform and nominated Arnold Miller from Cabin Creek, W.V. as their presidential candidate. Miller was a disabled miner, leader of the Black Lung Association and former soldier whose face was permanently scarred by D-Day invasion injuries. His running mates included another military veteran, 41-year-old Harry Patrick, a voice for younger miners, and Mike Trbovich, who helped coordinate Yablonski’s campaign in Pennsylvania. Despite continuing threats, intimidation, and heavy red-baiting throughout the coalfields, the MFD slate ousted Boyle by a margin of 14,000 votes out of 126,700 cast in December 1972.

Propelled by militancy

The union establishment was deeply shocked and unsettled by this electoral upset. Not a single major labor organization (with the exception of the independent United Electrical Workers) applauded the defeat of Boyle, an already convicted embezzler, who was later indicted and found guilty of ordering the assassination of Yablonski. The MFD victory and its tumultuous 10-year aftermath has been chronicled by such authors as former UMWA lawyer Tom Geoghegan in Which Side Are You On? Trying to Be for Labor When It’s Flat on Its Back, labor studies professor Paul Clark in The Miners Fight for Democracy: Arnold Miller and the Reform of the United Mine Workers, women’s studies professor Barbara Ellen Smith in Digging Our Own Graves: Coal Miners and the Struggle of Black Lung Disease, and the late Paul Nyden, a Charleston Gazette reporter, in Rebel Rank and File: Labor Militancy and Revolt from Below During the Long 1970s, a collection of case studies about the period’s labor insurgency.

As Nyden noted, the MFD’s grassroots campaign “channeled the spontaneous militancy arising throughout the Appalachian coal fields.” Before and after their election, MFD candidates had key allies inside and outside the union. Among the former, according to Nyden, were “wives and widows of disabled miners, wildcat strikers, and above all the young miners who were dramatically reshaping the composition of the UMWA.” Among the “outsiders” were community organizers, coalfield researchers, former campus activists, investigative journalists, and public interest lawyers, some of whom would later play influential roles as new national union staffers.

The MFD inherited a deeply divided organization, with internal and external problems that would have been daunting for any new leaders, not just working members suddenly catapulted from the coalfields into unfamiliar union headquarters jobs. In Digging Our Own Graves, Smith faults MFD leaders for deciding to “dismantle their own insurgent organization” because the “skeletal network of rank-and-file leaders” that was the MFD had “basically become the institutional union.”

“Many activists joined the union’s staff or became preoccupied with running for office in their new autonomous districts,” she writes. “The decision to disband the MFD had serious consequences, however. It left the new administration without a coherent rank-and-file base and it left the rank-and-file without an organized vehicle to hold their new leaders accountable.”

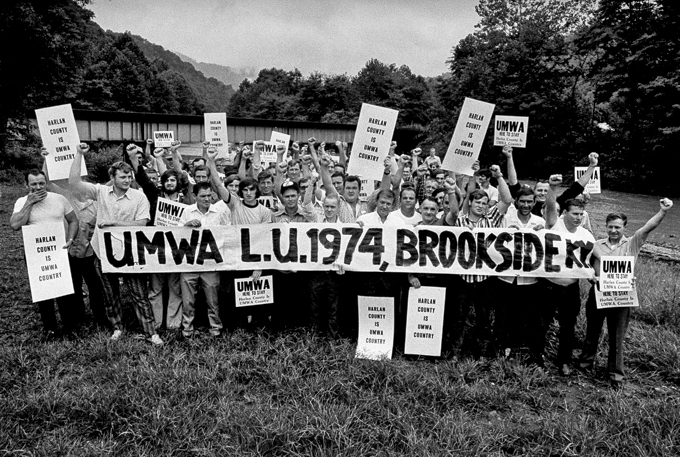

Photo of Harlan

The reformers elected in 1972 did succeed in democratizing the structure and functioning of the UMWA. They also revitalized union departments dealing with workplace safety, organizing, membership education, internal communication, and strike support (see Harlan County USA, an Academy Award-winning documentary, about one early test of the MFD’s commitment to fighting back, rather than selling out).

In the crucial area of national contract negotiations and enforcement, greatly heightened membership expectations were harder to meet. A 1974 settlement with the Bituminous Coal Operators Association (BCOA) provided wage increases of 37% over three years, a first-ever cost-of-living allowance, improvements in pensions and sick pay, strengthened safety rights and job security protection. But the new leadership’s approach to grievance procedure reform did not resolve the greatest point of tension between rank-and-file militants and those among them elevated to top union office.

In the mid-1970s, the underground miner tradition of direct action was still so strong that UMWA members regularly walked off the job over local disputes of all kinds. Their culture of solidarity enabled roving pickets to shut-down mines nearby, in the next county, or an adjoining state, even if a different BCOA employer was targeted and the conflicts involved were unrelated.

These wildcat strikes subjected the national union to potentially ruinous damage suits by coal operators seeking to enforce a much ignored “no strike” clause, which required most grievances to be submitted to binding third-party arbitration. In 1974, new UMWA negotiators did not press for an open-ended grievance procedure that might have turned such quick strikes into a more disciplined and legal tool for contract enforcement. Instead, they agreed to the creation of an Arbitration Review Board, which merely added another frustrating step to a dispute resolution process already back-logged and overly judicialized. As post-contract discontent mounted in 1975 and 1976, an estimated 80,000 to 100,000 miners joined unauthorized strikes for the “right to strike,” while also protesting federal court sanctions (fines or imprisonment) of strikers who ignored back-to-work orders.

A counter revolution

Within the union, the conservative Boyle forces continued to be a strong obstructionist force in some UMWA districts. Frustrated by Arnold Miller’s shortcomings as a negotiator and administrator, the most promising MFD leader — Secretary-Treasurer Harry Patrick — mounted an unsuccessful challenge to his fellow officer in a three-way race for the UMWA presidency in 1977.

Re-elected with a former Boyle supporter as his running-mate, Miller became increasingly weak, isolated and ineffective. His erratic handling of national bargaining with the BCOA helped set the stage for a 111-day strike by 160,000 miners who had to battle both the coal operators and their own faltering leadership. Highlights of that 1977-78 struggle included two contract rejections and a failed Taft-Hartley Act back-to-work order sought by President Jimmy Carter, a White House intervention even more controversial than Joe Biden’s role in the current national rail labor dispute.

UMWA contract concessions in 1978 and 1981 made organizing the unorganized increasingly difficult. More coal production shifted to the West, where huge surface mines required much smaller workforces, which usually remained “union free.” In the meantime, the multi-employer BCOA began to fragment, leaving the UMWA with fewer and fewer companies with which to negotiate an overarching national contract. Even firms operating in the eastern coalfields started non-union affiliates or subsidiaries, in what was becoming a declining industry.

More competent, progressive leadership was not restored until a second-generation reformer, Richard Trumka, took over as UMWA president in 1982. Trumka defeated Sam Church, who replaced Miller when the latter retired, after multiple heart attacks, in 1979. Trumka had gained valuable experience in the UMWA legal department during the mid-1970s. He had been a working miner before going to law school and then returned to the mines in preparation for seeking union office. But even with steadier, more skilled hands at the helm — and an inspiring strike victory at the Pittston Coal Company in 1989 — the union entered a downward spiral of reduced membership and diminished organizational clout.

Long before Trumka’s ascendency, most of the college-educated non-miners, who were swept into key positions by the MFD’s victory in 1972, had left UMWA employment. Some went to work for other unions, including the Teamsters under the TDU-backed presidency of Ron Carey in the 1990s. In 1995, Trumka become secretary-treasurer of the national AFL-CIO and, 14 years later, its president until his death last year at age 72. At the UMWA, he handed the reigns to his vice-president Cecil Roberts, who was part of the generation of recently-returned Vietnam veterans who got jobs in the mines and backed the MFD in 1972. Roberts serves on the AFL-CIO executive council and continues to rally UMWA members and their families against a resurgence of black lung disease due to coal and silica dust exposure among underground miners.

But, in recent years, the UMWA has been much preoccupied with the bankruptcy of leading coal producers, resulting lay-offs, and related political fights to protect the pensions and healthcare coverage of retirees who now far outnumber working members. Since April 2021, more than 1,000 Alabama members have been on strike against Warrior Met Coal, which is currently the union’s most high-profile contract struggle. Four years ago, Roberts — now 76 years old — was re-elected by acclamation to his sixth full term as national president. This makes him the second longest serving UMWA leader after John L. Lewis.

As modern UMWA history confirms, the road to rank-and-file power includes many pot holes and more than a few detours along the way. If union members can create a durable opposition movement and effectively utilize direct election of top officers, even many decades of institutional stagnation can be replaced by uplifting periods of organizational revitalization. But struggles for union democracy and reform often face larger constraints, including downsizing and restructuring of the industry which employs those seeking to revitalize their union and improve its leadership. Auto workers in the UAW have long suffered from a less severe decline of their basic industry but now have a rare and exciting opportunity to turn a union reform victory into a longer-lasting embrace of new organizing, bargaining and strike strategies that would benefit both white-collar and blue-collar members.

…

This article is also running in “In These Times”

Without a Whimper Or a Wail

By Stewart Acuff

Without either a whimper or a wail, the Democratic Party leadership easily, slyly, quietly, and quickly blocked a strike of railroad workers demanding the dignity of caring for themselves and their families.

Bargaining between the freight railroads and the workers’ unions had dragged on with difficulty with workers fighting for decent working conditions and human conditions of life.

Squeezing dignity and respect from the workers is what has enabled the railroad corporations to add billions to their profits. A Presidential Emergency Board (PEB) meeting in September resolved all the issues except sick leave. The railroad companies offered just one day of sick leave per year – up from zero. The workers continued to push for one day of sick leave every two months, a total of seven days a year. Seven days a year was the number Democrats had promised to legislate for all American workers, whether union or not.

But when workers voted down the PEB settlement and began preparing to strike for a contract that included sick leave, the President and Democratic congressional leadership moved, passed, and signed legislation making such a strike illegal.

Of course, they did the obligatory obfuscation. The House passed the legislation with seven days of sick leave in it. Sen. Bernie Sanders did all he could to include sick leave with an amendment to the Senate bill. But it failed with West Virginia Sen. Joe Manchin voting with Republicans to kill it, continuing his long record of anti-worker votes.

So, legislation stopping the strike without seven days of sick leave passed both Democratic-led Houses and was signed by a Democratic President.

IT’S NEVER RIGHT TO BREAK A STRIKE. NOT WITH BASEBALL BATS, TIRE IRONS OR GUNS, AND CERTAINLY NOT WITH LEGISLATION AND GOVERNMENT ACTION.

Of course, Democrats didn’t want a rail strike right before Christmas with freight containers of toys made in Asia and demand forcing up costs even more.

BUT WHAT IS WRONG, TROUBLING, AND DISAPPOINTING, IS THE SPEED, RAPIDITY, EASE AND GREASED PROCESS OF THE DEMOCRATIC LEADERSHIP IN VIOLATING THEIR PROMISES AND CURTAILING THE HUMAN RIGHT TO WITHHOLD ONE’S LABOR. ALL DONE WITHOUT ANY RESISTANCE TO THE FREIGHT RAIL CORPORATIONS.

Railroad profits have increased by billions in this past year. Third quarter profits were up as much as 13% to 15%. The only reason for them to deny sick leave is to make billions on the everyday family struggles of railroad workers. THAT IS OBSCENE!

The least we should be able to expect from a truly labor friendly Democratic leadership would be to publicly challenge the railroads on their dangerous and inhumane demands of workers and families. There are Democratic mayors across America who’ve prevented such strikes by putting the responsibility where it belongs…on the Boss.

I do not believe we should leave the party, but we should demand more than empty rhetoric and dusty policy on a shelf.

I was at the bargaining table when the Mayor of Santa Fe, N.M. prevented a hospital strike by challenging the boss to bargain with us in his conference room in City Hall at all hours till we reached a contract.

When we elected a mayor in Atlanta, GA, during our fight for worker justice in the 1996 Atlanta Olympics, he appointed me to the Atlanta Olympics Executive Council. Our fight went from the streets to the suites and the work was done union, with union wages and working conditions.

What if President Biden had said he wouldn’t sign any bill on the strike without seven days of sick leave? Or, until the railroads guaranteed sick leave?

What if the administration had challenged the parties to bargain at the Department of Labor with Secretary Walsh at the table?

What if Senate Majority Leader Schumer had refused to put the legislation on the floor for a vote without seven days of sick leave?

Instead, I watched Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg on CNN debating Jake Tapper, with Tapper demonstrating more good sense and understanding than the Secretary robotically insisting seven days of sick leave is the position of the administration, even as he dismissed working families’ needs.

WHAT IF THE PRESIDENT, HIS CABINET AND DEMOCRATIC LEGISLATORS HAD MADE THE LACK OF SICK LEAVE FOR RAILROAD WORKERS THE HEALTH AND PUBLIC SAFETY CRISIS IT IS?

The railroad corporations can run trains remotely without workers. They think they don’t need human beings. And they have no use for anything that keeps them from maximizing shareholder wealth and stock values at all costs, including human costs.

The response of leaders of a pro-worker political party is not rolling over, tail between their legs, but to fight for workers and the safety of the American people.

It’s painful to see Democratic leaders so remote and removed from our everyday lives that they can’t express empathy, much less strategize with unions to get workers what they need.

All this is exactly why it is time for workers and their unions to re-negotiate the relationship with the Democratic Party. I do not believe we should leave the party, but we should demand more than empty rhetoric and dusty policy on a shelf.

Since Ronald Reagan over 40 years ago and the government/corporate assault on labor, worker wages, benefits, and conditions have flattened out, or stagnated, shrinking buying power, our security, and forcing more workers into poverty. More and more families face the stresses of life with multiple bad, exploitative jobs, and exploding inequality.

Organized labor has struggled to respond with more militancy, national strikes, and much more organizing in the non-manufacturing economic sectors. But the ravages of late-stage capitalism have continued to reduce union density across the economy.

Just as tragedy in World War Two changed the labor market in the 40’s and 50’s, so has the Covid pandemic re-calibrated the American labor market today.

We now find ourselves with more jobs than workers – giving us real, fundamental, organic leverage. It’s past time to use that leverage to rebuild, grow, and win a greater share of the wealth we produce.

Organized labor needs a new strategy that includes a new relationship with the Democratic Party. The party continues to shed white working class folks and they ain’t coming back without unions and a powerful enough economic reason to overpower a history of racism, militarism, misogyny, and the opiate of casual hate.

…

New Film Recounts Latina-Led Fight Over Military Sexual Abuse

By Suzanne Gordon and Steve Early

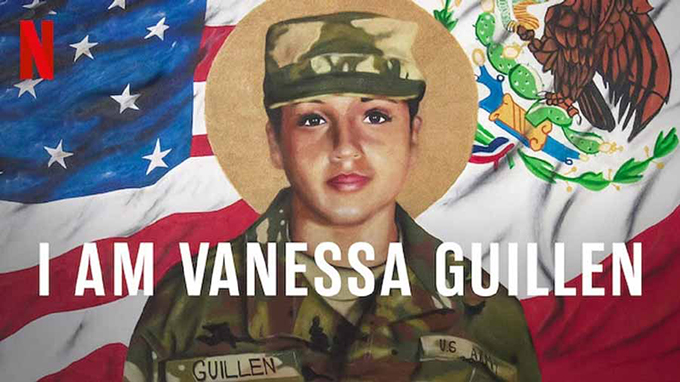

Two years ago, city hall plaza in our hometown, Richmond, CA., was the scene of a protest vigil organized by Estefany Sanchez and her two sisters. Estefany is a Richmond resident and an Army veteran whose experience of sexual harassment in the military led her to identify strongly with the tragic case of Vanessa Guillen, a 20-year old soldier at Fort Hood in Killeen, Texas.

Guillen was sexually harassed by fellow soldiers, at a base with one of the highest rates of sexual assault, sexual trafficking, suicide, and murder anywhere in the military. Her complaints to superior officers were repeatedly ignored before she was killed while at work in an armory on the base. Guillen’s assailant, Aaron Robinson, then secretly moved, dismembered, and buried her body with the help of a civilian accomplice still awaiting trial. After escaping from military custody, Robinson became one of more than 70 suicides at Fort Hood since 2016.

The Sanchez sisters’ Bay Area demonstration was part of a grassroots movement to challenge and change the toxic work environment that many young soldiers encounter, even if they are never deployed abroad or serve in a combat zone.

Protestors around the country demanded Congressional action to better protect victims of military sexual assault and harassment. Some also angrily questioned the targeting of working-class communities by military recruiters, who encourage young people to enlist based on the promise of secure employment, job training, career advancement, and future access to affordable higher education through the GI Bill.

An Oscar Contender?

This Latina-led campaign for military justice reform is now vividly recounted in a new movie called I Am Vanessa Guillen. Produced and directed by Christy Wegener, the film takes its name from a now-viral hashtag created by Guillen’s family to draw attention to her disappearance, which remained an unsolved mystery for several months, in 2020, due to a bungled investigation by the Army.

In the “Me Too” era, Vanessa Guillen’s real-life story will be a strong contender for an Oscar, in the best documentary category. Its Nov. 17 release by Netflix could not be timelier. Despite promising a workplace free from harassment and discrimination, the Department of Defense just disclosed that nearly 36,000 female service members reported unwanted sexual contact in 2021, a 13% increase over the year before and double the number in 2018.

Other studies have found that one in four women in the military have been sexually assaulted. Even former U.S. Senator Martha McSally, the first female fighter pilot to serve in combat and a conservative Republican from Arizona, was subjected to such treatment.

An advocacy group called Protect Our Defenders, reports that 44 percent of the service members it surveyed about their sexual harassment complaints were encouraged to drop the issue. Another 41 percent said that the superior officer to whom they reported an incident took no action. Despite the steady increase in sexual assault cases, conviction rates have plummeted by almost 60% since 2015. In 2018-19, for example, there were 5,699 reports of sexual assault but only 363 (6.4%) of those cases were tried by court martial, and just 138 (2.4%) resulted in convictions.

I Am Vanessa Guillen shows how a vibrant young woman, from an immigrant family, became the human face of such statistics. She was part of a 21st century influx of women into the armed forces that was initially lauded as an unqualified victory for gender equality. During the last two decades, 300,000 women were deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan and, today, female soldiers comprise 16 percent of the active duty military. Women are also the fastest growing cohort of military veterans, representing about ten percent of a total population of 19 million.

Unfortunately, joining the military has proven to be more harmful than beneficial to many young women. Some who experience military sexual trauma (MST) have even been given “other than honorable” discharges which can deprive them of VA healthcare coverage when they return to civilian life.

Despite promising a workplace free from harassment and discrimination, the Department of Defense just disclosed that nearly 36,000 female service members reported unwanted sexual contact in 2021, a 13% increase over the year before and double the number in 2018.

The popular uproar over Guillen’s disappearance and death led then-Army Secretary Ryan McCarthy to create an independent panel to determine whether Fort Hood was living up to the Army’s commitment to “safety, respect, inclusiveness, and diversity.” Investigators interviewed more than five hundred female soldiers and found that ninety-three had credible accounts of sexual assault, but only fifty-nine had been reported.

A Fort Hood Scandal

McCarthy agreed there were “major flaws” in a command structure so “permissive of sexual harassment and sexual assault.” The top officer in charge of the 55,000 troops at Fort Hood was removed and disciplined along with 20 others. But thanks to the tireless agitation of Vanessa Guillen’s mother and her two sisters, Congress was also forced to confront the problem of local commanders covering up misconduct on their watch–a phenomena long criticized by U.S. Rep. Jackie Speier (D-CA), an advocate for military justice reform since 2011.

By May 2021, sixty Senators (including Dianne Feinstein) favored a bill co-sponsored by Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY) and Joni Ernst (R-IA), a retired National Guard lieutenant general and past victim of domestic abuse. It would have transferred decision-making power about a wide range of cases, including some hate crimes, to a specially trained team of uniformed prosecutors operating outside the chain of command.

In the Senate, two military veterans on the Armed Services Committee, Rhode Island Democrat Jack Reed and Oklahoma Republican James Inhofe, fought to narrow the scope of the legislation, limiting it to sexual assault cases only. In I Am Vanesssa Guillen, Reed makes the factually challenged claim that “the basic instinct of the military is to protect your colleagues and subordinates, not to exploit them.”

In December, 2021, after similar pushback from Joe Biden’s Secretary of Defense, General Lloyd Austin, Congress passed a watered-down version of military justice reform. Although it did empower a new cadre of “special victim prosecutors” to handle cases involving sexual assault, rape, murder, and domestic violence, court-martial authority was left within the chain of command. At the time, Gillibrand described this compromise as a “disservice to our service members.”

In the film, Gillebrand explains why further Congressional action is still needed. “Being able to offer discharges, deciding which evidence is allowed, which expert witness is called, and even just deciding judge, jury, prosecutor, and defense counsel—it’s all still sitting with Commander So-and-So.”

That’s why Gillebrand, Feinstein, and others in the Senate are trying again to honor the memory of Vanessa Guillen. They have introduced the Sexual Harassment Independent Investigations and Prosecutions (SHIIP) Act. It would transfer responsibility for handling sexual harassment cases from military commanders to the new special trial attorneys, who can gather evidence and decide what cases to pursue without political interference.

Hopefully, with or without an Academy Award, I Am Vanessa Guillen will keep the spotlight on members of Congress and the Biden Administration who fail to provide women in uniform with the additional legal protection they so obviously need.

…

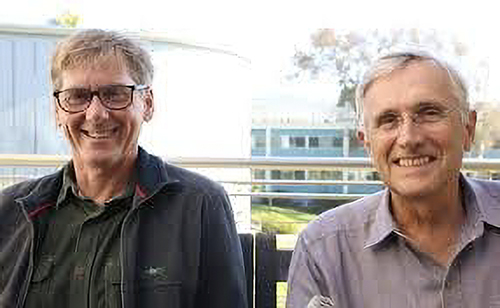

Remembering Fred Ross Jr., One of Nation’s Leading Labor and Social Movement Organizers

By Louis Freedberg

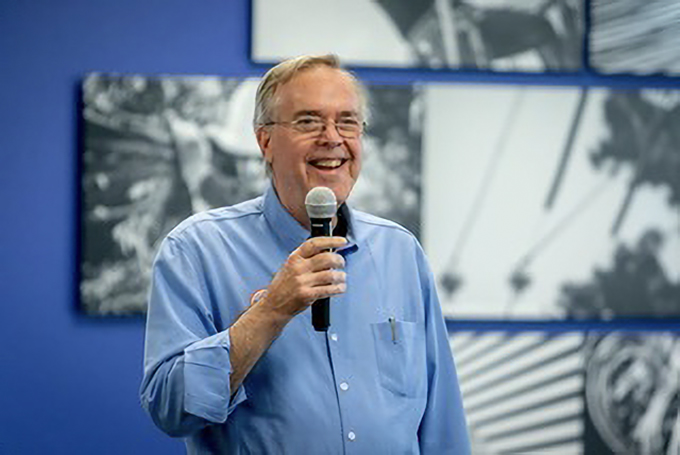

Fred Ross, one of the nation’s leading labor organizers who began his work at an early age in the lettuce fields of California alongside Cesar Chavez, but whose work had an impact far beyond labor organizing on both a national and international level, has died.

He played a pivotal role in successful efforts to propel Congressional action to change policies propping up oppressive governments in Central America, advocating to accelerate the naturalization of legal immigrants in the US, and in getting House Speaker Nancy Pelosi elected to Congress for the first time.

He died of cancer at his home in Berkeley, California, just weeks after celebrating his 75th birthday and receiving tributes from hundreds of friends and colleagues.

One tribute came from former U.S. Labor Secretary Robert Reich. “You have comforted the afflicted, and afflicted the comfortable,” he told Ross. “Your boldness and vision have been a source of inspiration to me and huge number of other people, working for social justice, labor unions, and the hopes and dreams so many people have for a better life.”

Ross’ brilliance was to take what he learned from Chavez as well as his father, Fred Ross Sr., himself a legendary organizer, combine those lessons with a savvy use of the media and field campaigns of local volunteers, to put pressure on state governments and Congress to advance a variety of causes – and when necessary, help elect candidates sympathetic to those causes.

One of those candidates was Pelosi, then a leader in the Democratic National Committee. Using some of the techniques learned in his work with the United Farm Workers, he organized the Get Out the Vote campaign for her first successful run for Congress in 1987 in San Francisco. Ten years later he joined forces again with Pelosi as her district director in her Congressional office in San Francisco.

“I personally benefited from Fred’s organizational mastery: translating his policy goals into effective political action. Without his early support and brilliant leadership organizing the ground operation of my first campaign, I would have never become a member of Congress.” Pelosi said in a statement.

Organizing “in my DNA”

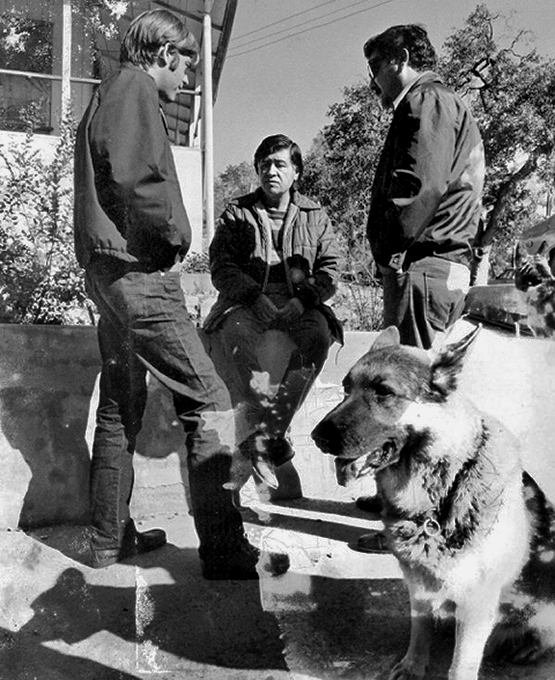

Born in 1947, Ross began work as a full-time organizer with the United Farm Workers (UFW) in 1970, the year of the historic general strike in the lettuce fields of Santa Maria and Salinas in California’s Central Coast,

Throughout his career, Ross employed the house meeting, a hallmark grass roots tactic developed by his father while working with the Community Service Organization, a Latino civil rights group Ross Sr. co-founded in 1948 related to Saul Alinsky’s Industrial Areas Foundation. It involved setting up meetings with small groups of people in their homes to make change happen in their communities or in later years to organize unions.

Years later, Ross reprinted many of his father’s sayings and tactics in a booklet called “Axioms for Organizers”which was widely distributed in English and Spanish throughout the United States and can be found in union halls and community meetings throughout the Country.

His mother Frances Ross, an original “Rosie the Riveter,” was a shop steward in a World War II plant in Cleveland, Ohio. She fought to help Jewish doctors immigrate from Nazi Germany. She was a pioneer in the mental health field and was the first women hired to be a lobbyist in Sacramento, state capital of California.

“So, fighting and organizing for racial and economic justice is in my DNA,” Ross said on many occasions. He acknowledged that he had gotten into a fair amount of trouble doing his organizing work — “good trouble, as John Lewis used to say.”

He recalled being knocked unconscious by a grape grower during a farm worker election and being shot at by a security guard at a supermarket. “Luckily he was a bad shot,” he quipped.

By his own count, he had been arrested 39 times, “mostly for good causes.”

Organizing with UFW

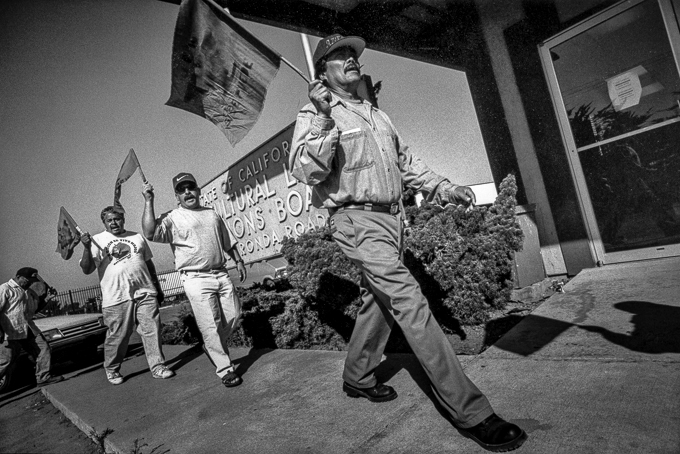

In early 1975 Fred conceived of, and organized a 110-mile march against Gallo wines that began in Union Square in San Francisco and ended with at least 10,000 farm workers and supporters at the company’s headquarters in Modesto in the Central Valley of California. At the time, it was estimated that Gallo Wines sold 1 in 3 bottles of wine in the United States. The UFW had by then been dismissed by some in the media as a “romantic cause” because it was confronting the powerful alliance with the Teamsters union that growers forged to suppress farm workers’ support for the UFW.

“That infuriated me, because I knew it wasn’t the case,” Ross said in an interview in October.

One of the other motives for the Gallo march was to put pressure on then-Gov. Jerry Brown to negotiate and push through the Agricultural Labor Relations Act, which was enacted in June 1975. It was the first law of its kind in the nation establishing the right of farm workers to organize, vote in union elections, and bargain with their employers.

Changing U.S. Policies on Central America

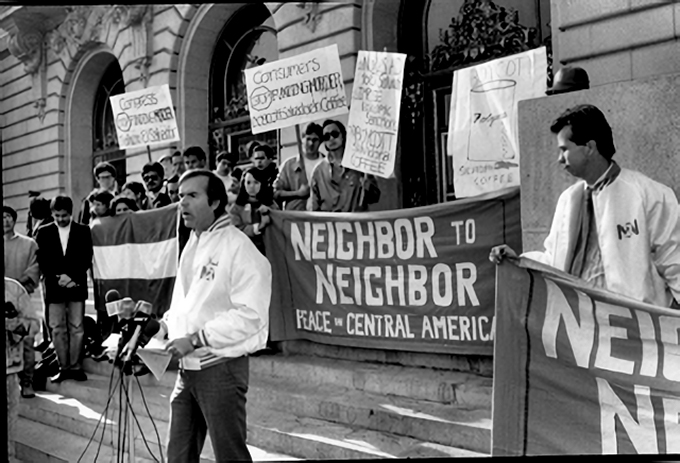

In the 1980s, Ross led Neighbor to Neighbor, a grassroots organization initially focused on dealing with the plight of refugees from El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Guatemala. It grew into a much larger effort to address U.S. policies in those countries that contributed to the refugee problem in the first place. “No one had developed a successful political strategy to challenge these policies in Congress, “ Ross recalled.

Neighbor to Neighbor sent organizers to swing congressional districts around the country to elect representatives critical of the Reagan administration policies in Central America, and to put pressures on incumbents to change their positions. These efforts played a part in ending aid to the Contras, the U.S. backed rebel forces in Nicaragua, and helped elect three women to Congress backing those changes. Rep Louise Slaughter, D-NY, served in Congress from 1987 until her death in 2018. Rep. Anna Eshoo, D-Palo Alto, also elected in 1987, is still in Congress.

Helps Elect Pelosi to Congress

The third woman was Nancy Pelosi, who asked Ross and Neighbor to Neighbor to run her get out the vote campaign. She was familiar with Ross’ work around Central America, as well as his leadership role in then-Mayor Dianne Feinstein’s successful defeat of a recall campaign against her in 1983.

Again, using tactics honed during his farm worker organizing days, Ross helped organize 118 house meetings, and enlisted over a thousand volunteers. As Ross recounted it, Pelosi’s father Thomas D’Alesandro, a former mayor of Baltimore who knew the value of neighborhood-based precinct organizers, sent Pelosi’s brother Thomas, generally called Tommy, to San Francisco “to make sure that Ross and this crew knew what they were doing.”

On one Sunday, Tommy, who also had served a term as mayor of Baltimore, tagged along with candidate Pelosi to 17 house meetings held over a 12-hour period. Ross also brought out a chart indicating that the campaign needed to identify 5,000 more voters and get 3,500 of them to vote.

At the end of the day Tommy called his father back in Baltimore to report that “Dad, they’re doing it better than we did. Nothing to worry about.”

Pelosi won her race by a narrow margin, embarking on a decades-long career that led her to historic terms as House Speaker. “You will always have my deepest gratitude as one of my earliest and most significant supporters,” Pelosi told Ross on his 75th birthday.

After the defeat of Contra aid, Neighbor to Neighbor shifted its focus to El Salvador, to pressure the government there to withdraw its support of death squads. To that end, Ross led a drive to boycott Salvadoran coffee, one of the country’s most lucrative exports, which he argued helped underwrite the military regime there.

A key turning point was when the International Longshoreman’s and Warehousemen’s Union under its president, Jimmy Herman, endorsed the boycott. Longshoremen refused to cross picket lines set up by Neighbor to Neighbor up and down the West Coast, including at its last stop in Long Beach. As a result, the Ciudad de Buenaventura ship was unable to off-load its cargo of 34 tons of Salvadoran coffee and was forced to sail back to El Salvador with the coffee still in its hold. That effectively sealed off the West Coast to Salvadoran coffee imports for the next two years.

The threat of further economic damage played a part in forcing the Salvadoran government to the negotiating table, and in 1992 the counterinsurgency war against the FMLN, a leftist guerilla organization, came to an end.

Helping Legal Residents Become Citizens and Voters

In the 1990s, Ross embarked on a campaign to shorten to six months the time it took legal immigrants to become citizens after they applied, and then to register them to vote. In the aftermath of Prop. 187, the anti-immigrant initiative backed by then Gov. Pete Wilson, he helped launch the Active Citizenship Campaign which, with the intervention of then Vice President Al Gore, successfully put pressure on the Immigration and Naturalization Service to speed up the naturalization process.

“We not only played a tangible role in putting pressure on the INS to help thousands become citizens in time to vote in that next election, but more importantly, to become a lot more engaged in the whole political process,” recalled Ross. “That was the beginning of a real breakthrough in continuing to build Latino voting power in California in the aftermath of Prop 187.”

Training “Organizing Stewards”

In 1998, Ross returned to his labor roots by organizing health care workers for the Service Employees International Union, working closely with Eileen Purcell, whom he described as “my organizing partner of a lifetime.” For 13 years with the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers Local 1245, he developed a nationally recognized program to train union members to go beyond being stewards that handled union affairs, but to be organizers while keeping their regular jobs at Pacific Gas and Electric. These “organizer stewards,” as Ross called them, would volunteer on non-work time to fight anti-union right-to-work legislation or work in electoral races in their own states or elsewhere. If necessary, they would take a leave from their regular jobs while being paid by the union to do so, but always return to their regular jobs with PG&E. Among the races these organizers participated were the Senate campaigns of Rev. Raphael Warnock and Jon Ossoff in Georgia two years ago. Their election returned control of the Senate to Democrats after a half dozen years with a GOP majority.

Most recently, Ross was working on producing a documentary film on his father that underscored the critical role of organizing, with an emphasis on one-on-one relationships that could be forged to build collective power. Even after being diagnosed with a terminal illness, he worked tirelessly to raise funds for the film, which is being directed by Ray Telles.

As the United Farm Workers said in a tribute, “His father Fred Ross Sr. had remarkable accomplishments. But perhaps his best legacy was Fred Jr. Colleagues over many decades said Fred Jr.’s organizing talents matched anyone’s, including Cesar and Fred Sr.”

“As with his father, Fred Jr.’s labors were never about himself,” the UFW tribute stated. “He was always about empowering others to believe they were responsible for the progress they won. Fred Jr.’s nature was ceaselessly positive; he always thought things could be done.”

Throughout his life, Ross exemplified the principles of organizing he wrote about in an introduction to Jacques Levy’s Cesar Chavez: Autobiography of La Causa. “I learned from Cesar Chavez and my father that the organizer works behind the scenes, patiently asking questions, listening respectfully, agitating, teaching new leaders, pushing them to take action, and creating hope con ánimo, with great enthusiasm. The organizer finds people one at a time, teaches them to develop their own powerful voices, turns their anger about injustice into hope by encouraging them to take action, raises hell, stirs up trouble and has fun doing it.”

Ross, a longtime Berkeley resident, is survived by his wife, Margo Feinberg, a prominent labor attorney, counsel to many significant labor organizing campaigns and author of innovative local legislation geared to enhance the rights of workers; their two children, Charley and Helen Ross; brother Robert Ross and sister Julia Ross; and a legion of friends and family members and generations of organizers.

In lieu of flowers, the Ross family asks that contributions go to the Fred Ross Project. Written condolences to the family may be sent to FredrossMemories@gmail.com

.

For more information, or questions, please email Louis Freedberg at: louisfreedberg@gmail.com

…

Jon Melrod – Labor Lessons Learned

By Peter Olney

I reviewed Jon Melrod’s book, Fighting Times: Organizing on the Front Lines of the Class War, for In These Times—but I wanted to draw out more of Jon’s important lessons for the new generation of working-class organizers, so I sat down with him at his home in Northern California and interviewed him. Jon is a friend and comrade who continues to fight the good fight by advising young comrades on how to do working-class organizing. He has made connections with young organizers at both Starbucks and Amazon. He has much to say about how to conduct daily battles over the countless workplace abuses of capitalism and how to make the linkages between those skirmishes and the broader battle for democracy and against capitalism.

“you’ve got to be there for the long haul and you’ve got to be willing to roll with the punches.”

Jon Melrod

Peter Olney (PO): After your time as a student militant at the University of Wisconsin you decided to take a working-class job and organize up the road in Milwaukee. Tell us about the plant where you landed in 1972.

Jon Melrod (JM): I went to work at American Motors in 1972. In 1969 there had been 14 wildcats in one week at the Kenosha and Milwaukee American Motors plants. So I mean, you know, every time there was a grievance the Chief Steward, who was the Chief Steward of the whole factory, would say, “Let’s go on out until we get it settled.” And I have a great picture from 1973 of all these middle-aged white guys in Kenosha holding signs saying, “Wildcat strike,” “Paint Department on strike.” So I said this is the right place to be. If you wanted to be a rebel and you wanted to fight for something to change the world, you went to work at American Motors.

This was a very historic plant, the first auto plant organized in the United States. In 1933, a chief steward, a very left-wing militant named Paul Russo, went off his job to collect money for a worker whose house had been burned down. The foreman ordered him back on his job. And he said, “No, I’m taking a collection for a union brother who lost his house.” So they fired him. When they fired him, the whole Trim Department sat down. It was the first sit-down in auto, before Flint.

After that, the strike spread to Racine and Milwaukee and the Kenosha plant shut down. At that point, the company was forced to recognize officially the first union in auto and it was the first written contract in any auto plant in the United States. It was a one-page—basically just recognizing the union. But the way the union ran the shop was it was all past practice. So whatever we had established as past practice became the way that the relationship between management and the union functioned.

PO: How did you begin to establish your credibility at the plant?

JM: One of the things for new organizers today—and we’ll talk about this more—is people respect somebody who works hard, who’s willing to stand up for themselves, who’s not afraid of physical challenges. I’m not a very big guy and that really worked to my detriment. You know, the first leaflet we put out at the plant gate I was standing out in front of the door and fucking all of a sudden this bucket lands on my head full of cleaning fluid. And I’m covered in cleaning fluid. My eyes are stinging. And you know, I ran up – I knew where it came from because on the fourth floor in the Cushion room where they used to make the seat cushions, that was where the union hierarchy worked because it was easy. It was off the line and it was all white and they were all Korean War vets and they were all very conservative.

I came running up four flights of stairs and I ran into the Cushion room and I was, “Which one of you mother fuckers is chicken shit enough to dump something on my head when you can’t be seen?” And of course, everybody shut up and nobody said anything. But the fact that I stood up to them and that I was back out at the gate that afternoon handing out flyers to the second shift showed them.

It’s a rough and tumble world in the working class, you know? You’re not a student any longer writing papers for a living, you’re working for a living and you’ve got to stand up for yourself. And that became an important lesson many, many times from then on.

PO: So here you are in an auto plant and correctly focused, I think, on the battles that these workers are confronting day-to-day in their factory lives. How is there a connection between fight over drinking water and socialism?

JM: Well I think in every struggle in a factory, no matter how small or how large, there’s much larger implications. Because it’s really part of a class war. The title of my book is actually Fighting Times: Organizing on the Front Lines of the Class War. For example, they came around one Saturday and they said the president of the union has said that we need to get a Saturday of overtime in—there’s not enough cars in the dealerships. So mainly the young guys and I, we used to party hard every Friday and Saturday night. And we said damn, if we have to work on a Saturday, that’s the end of our partyin’ life. And I went and looked back at the contract, which was really this thick black book of probably 300 pages of codification of work rules, and it said you have the right to refuse overtime.

So, I went to the guys and I said, “Look, we don’t have to work overtime.” And we ran off copies of that page in the contract and handed it out. Next morning when they came through to tell everybody, “You’re coming in on Saturday; just want to make sure you know it; this is your notice,” everybody said, “We’re not coming in. We’ve got the right to voluntary overtime.”

And the word spread, and they couldn’t get a workforce, okay, and they were threatening to discipline people, they were threatening to fire people. People were saying we’ve got a right to voluntary overtime. Here again you have this class struggle that’s always at work. The company wants cars; you want a decent fucking life where you’re not a slave to your job. Capitalism means you’re a slave to your job, you know. With a militant union, at least you can put up a hell of a good fight. And they had to cancel the overtime.

PO: That’s a pretty rich tale Jon. Can you give us another example?

JM: Sure. The company announced they were going to speed up the assembly line. They were going to add about three cars an hour and not change our work assignments at all. Three cars an hour is a huge addition to the amount of work you have to do. And we put out a leaflet. Didn’t know what we were doing. We got an old mimeograph machine and we wrote up a leaflet that said, “Speed up kills. Fight speed up.” We handed it out and all of a sudden the factory was in an uproar, ’cause this woke up the old timers.

And the old timers said, “Do you know how we fight speed up? We ride the line.” I said, “What does it mean you ride the line?” They said, “That means you work to contract. You work no faster than the normal pace,” which was what was in the contract. “You can only be expected to work at a normal pace.” So, they taught us younger guys stay in the car until you finish your whole job, even if it pushes you two work stations down the line and that pushes four more people down the line. And meanwhile, it means that nobody’s getting their job done and everybody’s throwing the parts in the car, so there’s no cars that are getting built as a completed car. They’re all on the repair areas, stocked up.

You realized in doing that that there was a tremendous power that people had, that without your giving them the right to control your labor power you in fact have the power and that’s an important lesson that applies to society in general. You begin to realize that it’s workers that make all of society run and it’s capitalism that exploits workers to the benefit of the owning class.

PO: You got fired several times for your union work. In 1973, you ended up going to the NLRB. What happened?

JM: So, I went to the National Labor Relations Board and luckily the officer doing the interview was actually quite sympathetic. And I said all right, well we’ll see what happens. But even while I was fired I kept going to the plant basically every week to keep working with people, to help them with the 1974 auto contract. I stayed active. You know, I didn’t go home. The union told me go home and wait and we’ll see what happens. But I stayed active.

And about nine months later, the morning newspaper had a big article, “AMC ordered to rehire two fired workers,” and the Labor Board had ordered them to rehire me but in really strong language. The Labor Board blasted them for using McCarthy-like tactics to spread rumors that we were communists. And in fact, we had been engaged in protected activity.

So, they ordered me to be rehired. I now have a memo that the company and the FBI had collaborated on that they were not going to rehire me. They said, “No matter what the court says, we’re not rehiring Melrod. He’s too much trouble.”

But after two and a half years, the Seventh Circuit—that’s the Court of Appeals, the Federal Court of Appeals—ordered American Motors to rehire me. And at that point they really had no choice and they put me back to work.

PO: You said something that caught my attention when you said, you know, “After I was fired, I didn’t disappear. I’d show up at the plant.”

JM: One thing that I think is really important for young people to understand, particularly in this world where tweets are like 200 words and everything moves fast and there’s immediate satisfaction, you’ve got to be there for the long haul and you’ve got to be willing to roll with the punches. When I first ran for steward, I drove three guys in my car out to the voting in the union hall and I was the fourth. And the next morning I went to look at the bulletin board where they listed the returns on the steward election, and my name was on the very bottom. I only had gotten three votes. One of the guys I drove didn’t even vote for me.

And it was pretty demoralizing. I mean, I kind of slunk away, you know, from the crowd looking at the returns and I had a day to think about it. And it led me to a lot of important conclusions. ‘Cause you’ve always got to be thinking about what you did right and what you did wrong. And one of them was that I had not been involved enough in the day-to-day fights. In other words, I was always at the gates with the Milwaukee Worker and political flyers. We organized people to go to May Day. We organized people to march against the Ku Klux Klan in Tupelo. And that’s all good and that’s important to bring in those political issues. But if you want to represent people, they’ve got to see that you’re going to stand up to the company.

And from that day on I said I don’t care if it’s a spill of grease on the floor, I’m going to make a fight about it or I’m going to start a petition about it or I’m going to get a group of workers to go confront management on it. Because it doesn’t happen overnight. You don’t get elected the first time. You don’t always win the union vote the first time. You know, I mean, this is serious business and if you’re trying to fight a serious class enemy that’s determined to keep unions out and to keep wages down and to keep people working for as many hours a day as they can, you know, then you’ve got to be ready to throw down and take that on.

PO: When you were in the UAW, you began what would be a long fight for “one member, one vote” in the union. Leaders of the union were historically chosen at convention by delegate votes rather than direct election by the members: one member one vote.

JM: In 1983 we were running a slate for the convention, International UAW convention, and we looked around to figure out what was the most important issue that broadly affected locals around the country. And we decided it was the issue of democracy in the union, because if you don’t have the right to vote for international officers, you have an autocracy. And [UAW President Walter] Reuther was able to build something called the Administration Caucus, and everybody who made it to the top leadership had to be a member of the Administration Caucus and even to be an international rep. At that time there were about 350 full time international reps in the UAW had to be a member of the Administration Caucus.

PO: And even regional directors, right?

JM: And even regional directors. So we took that issue to convention. Earlier we had helped form Locals Opposed to Concessions, LOC, with militant locals in Detroit. And those locals had opposed concessions at Chrysler and at GM and at Ford. And we had developed relationships with the leadership of those locals. So we really went out to them to build this movement for one member, one vote. And for them it wasn’t just a matter of winning the rank and file’s right to vote, but it was also a way to punish the International Union for having granted concessions.

So, we took it to a membership meeting and everybody in the local supported it. There were a thousand members at that meeting who voted to write a resolution to be delivered to the convention Resolutions Committee supporting the concept of one member, one vote. With that vote of the membership was also an endorsement that Local 72 out of Kenosha lead a national push to establish one member, one vote.

Once it became the official position of the union, the local gave us a budget of $100,000, which in ’83 was a lot of money. And we forced the International to give us a mailing list of all the locals in the country, and we spent hours and hours sending out letters to every local, to every convention delegate, local—the head of their delegation would receive a letter asking them to pass resolutions supporting one member, one vote.