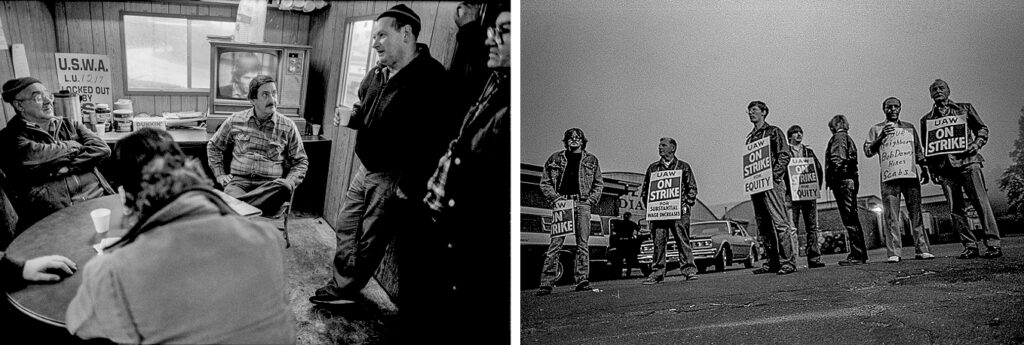

“Labor Power and Strategy” at the People’s Forum in New York

By Robert Gumpert

On Saturday, February 4 the People’s Forum in New York City hosted a discussion of the new book, Labor Power and Strategy from PM Press. Alex Press of Jacobin magazine moderated a far-reaching discussion between Peter Olney, Melissa Shetler and Gene Bruskin, three contributors to the book. The book published in 2022 consists of interviews with Harvard Professor Emeritus, John Womack and then the responses of ten of labor’s best educators and organizers. It is short – 152 pages – and truly a pocketbook that lends itself to discussion and debate. Here is a link to the February 4th panel:

…

Forgotten – an African American Soldier Turned Rebel Leader in the Philippines

By Jonathan Melrod

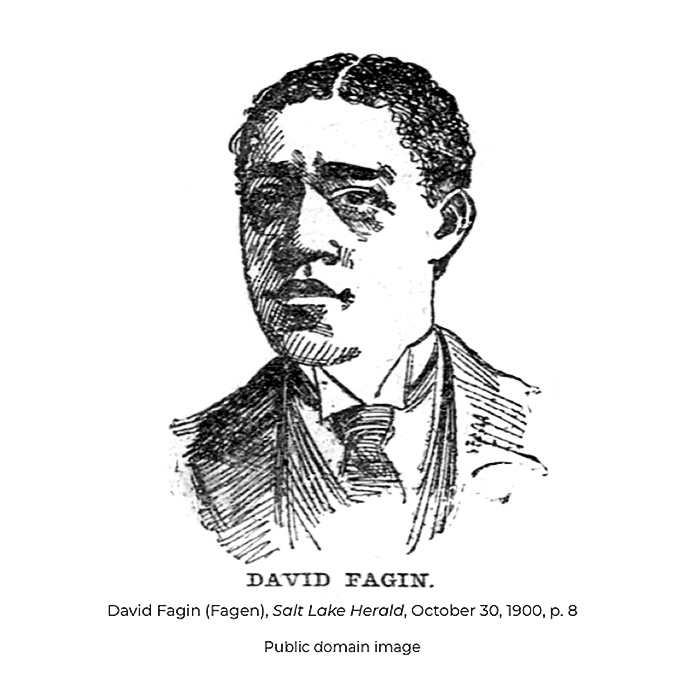

LONG LIVE THE MEMORY OF DAVID FAGEN DURING BLACK HISTORY MONTH!

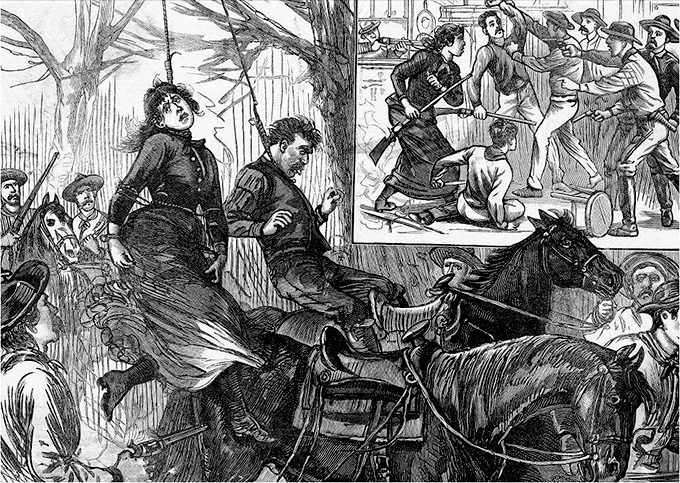

You won’t find this story anywhere else for Black History Month, but you should! By the mid-1900’s, a “Buffalo Soldier” named David Fagen was virtually a household name, particularly in the African American community. Fagen’s story makes myth of the false contention that African Americans offered little resistance to institutionalized racism from the Civil War until the end of WWII.

Was Fagen a hero or mad dog?

The answer is rooted in whether you believe that fighting against U.S. colonialism/imperialism in 1899, in this case the U.S. war of Philippine conquest, is righteous and worthy of giving rise to a true hero, martyr and courageous Buffalo Soldier, who deserted the U.S. side and joined the Philippine Revolutionary Army. The PRA was fighting to establish their own independent republic after the Spanish were kicked out.

In diaries and letters, Black soldiers posted in the Philippines. recounted how racism was endemic in the U.S. military, describing the racist abuses suffered by both African Americans and Filipinos.

Fagen was a native of Tampa, Florida, the youngest of 6 children of former slaves. He grew up where Jim Crow racial segregation laws prevailed. With the specter of lynching, race riots and the chain gang looming over Tampa’s Blacks, Fagen “lived in dread at all times.” Searching for any escape from Jim Crow, Fagen enlisted in 1898, being assigned to the 24th Infantry Regiment, a unit of so-called Buffalo Soldiers.

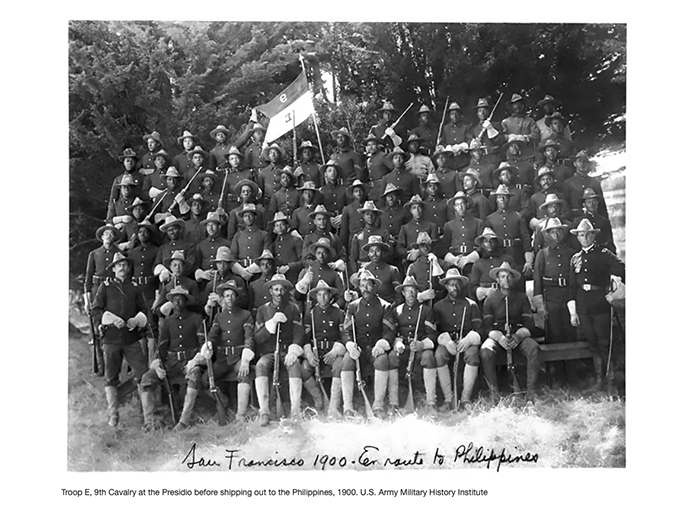

Expansionist America, intent on developing a global commercial empire, dispatched 6000 African American soldiers, including 2100 of the famed Buffalo Soldiers, to the Philippines islands per President McKinley’s assessment that the racial inferiority of Filipinos justified denying them sovereignty and engaging in a bloody war of conquest.

Fagen, now on the battlefield, detested his white commanding officer Lt. Moss, a West Point graduate. Moss and Fagen clashed repeatedly, with Moss eventually fining Fagen more than a month’s pay and sentencing him to 30 days of hard labor. Life was immutably altered when Fagen, after just a few months of battling Filipino rebels, turned his back on the U.S. army and joined Filipino revolutionaries who were fighting against American invaders.

At the time, there was a fierce debate in African American communities on their role in these foreign wars. Many saw the invasion of the Philippines as a ‘race war’, through which white settlers would inevitably repeat in Asia the wave of enslavement and genocide that had been inflicted on Native Americans and Black slaves.

Contrary to enlistment promises, African American soldiers in the Philippines were relegated to second-class status. Officers often ordered them to carry out ‘dirty jobs’ that no white soldiers wanted to do. They were also forced to serve as expendable “shock” troops on the frontlines, where lives were most at risk, while white commanders stayed back at a safe distance from the Filipino rebels.

Filipino insurgents put up posters and distributed flyers with messages encouraging ‘colored’ soldiers to join their cause, appealing to their common suffering at the hands of white Americans.

Historians studying the Philippine-American War estimate that at as many as 15 Buffalo Soldiers decided that their place, rather than helping to suppress the Filipinos’ struggle for independence, was in joining them in revolution. The supposed ‘deserters’ of the 24th infantry proved one thing: systemic racism and oppression by white Americans was enough to forge alliances across vast national and ethnic lines.

This may have been the very reason Fagen turned his back on the U.S. army, for a new life as a Filipino guerrilla. One night, Corporal Fagen snuck out of his barracks and met with a Philippine ‘insurrecto’ officer, who had arranged Fagen’s escape. The rebel agent had a horse waiting for Fagen outside the garrison, and together, they disappeared into the jungles.

Fagen was never captured or killed. Out of respect and tribute for his role as guerrilla leader, his Filipino compatriots addressed him as El General, although he was a Captain. Despite the wide respect and honor in which he was held by his fellow anti-imperialist insurgents, the U.S. army branded Fagen a deserter and traitor and expunged all memory of him from the annals of history. His racist white U.S. General, Frederick Funston, described Fagen as a “bandit pure and simple, and entitled to the same treatment as a mad dog”.

In this writer’s estimation, Fagen was anything BUT a ‘mad dog’, but a courageous resistance fighter who chose the right side in a battle against U.S. aggression and imperialism. I conclude with the aspirational belief, circulated by many, that Fagen fell in love with a Filipina woman and ran away to the mountains to live a peaceful life with her.

.

For more information on David Fagen, try these sites:

Zocalo Public Square; Wikipedia; Black Past; Esquire; UC Press; WUWF Radio; National Park Service

This piece orginally appeared in CounterPunch

…

21st Century Soldiering: Veterans of Post-9/11 Wars Reflect on Their Experience

By Steve Early and Suzanne Gordon

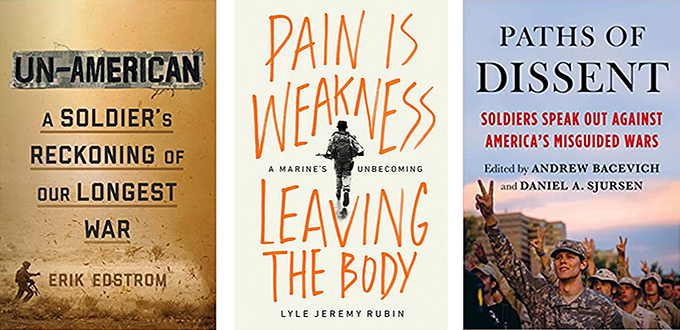

Review of Un-American: A Soldier’s Reckoning of Our Longest War, by Erik Edstrom’s (Bloomsbury, 2020); Pain is Weakness Leaving the Body: A Marine’s Unbecoming, by Lyle Jeremy Rubin (Bold Type Books, 2022), and Paths of Dissent: Soldiers Speak Out Against America’s Misguided Wars, edited by Andrew Bacevich and Daniel Sjursen (Metropolitan Books, 2022).

One frequent casualty of war is the confident belief shared by new soldiers that their cause is just and worthy of great personal sacrifice. After Al-Qaeda downed four civilian air liners and caused nearly three thousand deaths on September 11, 2001, US military recruiters were flooded with eager volunteers. Patriotic fervor, coupled with an urge for revenge and a desire to make the world a safer place, motivated many young men and women to enlist.

As the reality of simultaneous interventions in Iraq and Afghanistan began to sink in, many participants — like Vietnam veterans before them — became angry, embittered, and disillusioned. Some of them have turned to memoir writing that debunks the whole costly and disastrous $8 trillion project known as the “global war on terror.” Three excellent new book-length reflections on military training, socialization, and combat duty in the Middle East definitely won’t end up on the reading lists of college-level or Junior ROTC programs or even the US service academies.

But many civilian readers will benefit from the policy critiques and personal insights found in Erik Edstrom’s Un-American; Lyle Jeremy Rubin’s Pain is Weakness Leaving the Body; and Paths of Dissent, an edited collection compiled by Andrew Bacevich and Daniel Sjursen, bothof whom became historians after serving as career Army officers.

Like Bacevich and Sjursen, Edstrom attended West Point. Afterwards, he served as an Army Ranger, an infantry platoon leader and Bronze Star winner in Afghanistan, and a member of Barack Obama’s Presidential Escort Platoon. The grandson of a World War II veteran and product of a middle-class upbringing in a Boston suburb, he was part of the first post-9/11 crop of applicants to the Point, a place where “you couldn’t help but get excited at the prospect of shooting, bombing, and invading.” His second thoughts about soldiering started when his first-year class was immediately “isolated, separated from families and support networks” so that, during their “initial indoctrination,” they would be “sheltered from anything that could temper or make us question military dogma.”

Pray and Spray

As part of the process of getting “all-American swimmers, pious altar boys, cauliflower- eared wrestlers, nerdy class treasurers, and Eagle Scouts” ready for eventual deployments in Iraq and Afghanistan, West Point cadets were marched in cadence to this edifying chant:

“Left right, left, right, left right KILL!… I went to the mosque where all the terrorists pray, I set up my claymore, AND BLEW’ EM ALL AWAY . . . I went to the store where all the women shop, pulled out my machete, AND BEGAN TO CHOP! I went to the playground where all the kiddies play, I pulled out my Uzi AND BEGAN TO SPRAY!”

At the academy, Edstrom reports, “I was taught to think about how to win my small part of the war, not whether we should be at war.” Sent to Afghanistan, he soon discovered that “fighting terrorism” was a confounding task for soldiers up and down the “chain of command.” Many of his local foes turned out to be “teenagers or angry farmers with legitimate grievances…people tired of our never-ending occupation of their land and contemptuous devaluation of Afghan lives. When I searched my own soul, I couldn’t blame them for fighting back. Had I been in their shoes, I would have done the same.”

Lyle Jeremy Rubin took a more unusual route to becoming a junior officer disillusioned with his own “forever wars” involvement. As we learn in Pain is Weakness Leaving the Body, Rubin was a fervent Zionist in high school and a “pro-war activist” while a Young Republican in college. Skipping service academy training and ROTC at Emory University in Atlanta, Rubin first experienced the Marine Corps as a failed Officer Candidate School candidate who became a boot camp grunt. This gave him considerable insight into what he calls the “lance corporal underground” and “camaraderie of the enlisted ranks that adds up to a latent class solidarity.”

“As enlisted Marines are fond of remarking, they represent the majority of the military that ‘works for a living.’ The Marine officer corps, on the other hand, is made up of strivers, who’ve learned to compete at an early age and [end up] pitted against other in a cutthroat peer-review process and promotional system that follows…There was an earnestness to the enlisted existence, a conviction of collective duty and sacrifice, however barbaric its realizations, that was never allowed to congeal among the brass.”

Rubin was eventually tapped to be a first lieutenant doing signals intelligence work in Afghanistan. This followed a two-month stint at the National Security Agency headquarters in Fort Meade, Maryland, where he was briefed on a surveillance system “designed to make kill-or-capture missions as user friendly as possible.” As part of his training, Rubin learned about the NSA’s “pattern-of-life analysis of random Afghans at a Top Secret watch floor,” where it was hard not to feel suffused with a “god-like omniscience.”

Real-Time Targeting

As Rubin discovered later in the field, the US military’s ability to “eradicate anyone holding an earmarked SIM card” did not prevent tech-savvy Taliban commanders from “switching out their cards as a regular security precaution.” The same “real time” targeting capability was used thousands of times during his deployment “to finish off alleged enemy combatants, many of whom investigative reports have now concluded were civilians.” At the time, however, “battle damage assessments listed virtually all military-aged males as the enemy.”

The disconnect between “war on terror” propaganda and the reality of meddling in the affairs of a country long resistant to foreign occupation took a painful toll on Edstrom and Rubin. Upon his return to the US as an Army captain, Edstrom received “thudding back slaps and free beers from well-meaning civilians” for whom the war had become “elevator music.” Meanwhile, he had to live with the memory of soldiers killed and maimed under his command, and the knowledge that terrorism — in the form of “targeted assassinations, bombings, drone strikes, secret ‘black site’ prisons, torture, and wanton civilian murder” — was central to the “counter-terrorism” mission. All Rubin wanted to do, after coming home, “was stop the war. And short of that, commiserate with those who, at the very least, could see it.”

The fifteen contributors to Paths of Dissent shared that desire as well and often helped create organizational platforms for educating and agitating against US foreign and military policy. In his essay for the book, Jonathan Hutto describes his path from Howard University to the Navy, where he became a key organizer of the “Appeal for Redress.” This 2006 statement, backed by several thousand active duty, Reserve, and National Guard troops serving in ten countries around the world, called on Congress to end the occupations of Iraq and Afghanistan.

Following their military service abroad, both Joy Damiani and Vincent Emanuele found their way to Iraq Veterans Against the War and Veterans for Peace. With their guidance and encouragement, Damiani “learned more and more of the truth whose surface I’d barely scratched as a miserable, demoralized soldier” assigned, as an Army public affairs specialist, to “making PR look like news and an unwinnable war look like a victory.” A Marine who refused a third combat deployment to Iraq, Emanuele took his criticism of the war to Capitol Hill, where he testified in 2008 about mistreatment of prisoners and “rules of engagement” that endangered non-combatants.

Pathways to Dissent

Among the other notable voices in this outstanding collection are Matthew Hoh, a dissenter within the Pentagon and the State Department who resigned in protest in 2009, continued his anti-war activism, and ran for US Senate as a Green Party candidate from North Carolina in the most recent midterm election. In another chapter, entitled “Truth, Lies, and Propaganda,” former minor league baseball player Kevin Tillman recalls how he and his brother Pat, a National Football League star, became Army Rangers, deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan. Pat Tillman’s death during a 2004 firefight in Afghanistan was infamously covered up by the Pentagon. As his brother recalls, “the Bush Administration didn’t like the optics of a high-profile soldier like Pat being killed by friendly fire…So the government lied to us — his family— and to the American people with a manufactured story about dying by enemy fire and then used him to promote more war.”

In addition to co-editing Paths of Dissent, retired Army colonel and former Boston University history professor Andrew Bacevich and retired Army major Danny Sjursen both helped launch new vehicles for influencing public opinion about military intervention abroad. Bacevich cofounded the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft, a Washington, DC-based think tank that is promoting “ideas that move U.S. foreign policy away from endless war and toward vigorous diplomacy in the pursuit of international peace.” As Bacevich told us when the Quincy Institute was launched in 2019, “I’m optimistic that we’re going to make a dent at least in the foreign policy consensus. That won’t necessarily send the military-industrial complex fleeing or surrendering, but it will have some impact.”

Like Quincy, the nonprofit Eisenhower Media Network, started by Sjursen, is dedicated “to educating Americans about the social, political, and financial destructiveness of the military industrial complex.” Now directed by retired Air Force Master Sergeant Dennis Fritz, the Media Network has assembled a distinguished roster of former service members who can offer media outlets an alternative perspective often missing from mainstream reporting and commentary on “defense issues.” (Eisenhower experts include Erik Edstrom and his fellow Paths of Dissent contributors Dan Berschinksi and Matt Hoh.)

By making well-credentialed Pentagon critics available to podcasts, tv and radio shows, national magazines, and newspapers, the media network is trying to reach “broad cross-partisan audiences,” rather than just activists already opposed to war and militarism. The authors of Un-American, Pain is Weakness, and Paths of Dissent have the same vital educational mission, which their readers can assist by spreading the word about these books and getting local libraries and bookstores to order and display them.

…

“We’re Not Allowed to Hang Up”: Harsh Reality of Working in Customer Service

By Ariana Tobin - Ken Armstrong - Justin Elliott /ProPublica

ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up to receive our biggest stories as soon as they’re published.

<script type="text/javascript" src="https://pixel.propublica.org/pixel.js" async="true"></script>In their own voices, seven customer service representatives reveal what it’s like being caught between abusive callers and demanding employers.

Last year ProPublica wrote about the world of work-at-home customer service, spotlighting a largely unseen industry that helps brand-name companies shed labor costs by outsourcing the task of mollifying unhappy customers.

As we reported on the industry, we invited current and former customer service representatives to contact us. They did. We heard from more than 100 and interviewed dozens. Often, their stories disturbed us. One woman, afraid to take a bathroom break, kept a jar under her desk in case she needed to urinate. Another, afraid to call in sick, paused calls to vomit. A third, afraid to hang up on a customer, didn’t know what to do when she realized a caller was masturbating to the sound of her voice.These accounts captured how agents are simultaneously ubiquitous and invisible. Customers talk to them all the time but know little about their work conditions.

So we’re providing accounts from seven agents, many of whom describe the experience of being caught between abusive callers and corporate directives to appease. These seven are highly representative of the 100-plus agents we heard from, as well as the agents we interviewed in our first article. The agents, including some who told us they love their setups, laid out common themes, describing problems that people at various levels of the industry, including managers, have told us are endemic. We’ve also found echoes of these complaints in lawsuits and arbitration claims. Abusive callers are such a concern that, a few years ago in Canada, a union for telecommunications workers launched a campaign called “Hang Up on Abuse.” Airbnb, recognizing the emotional strain of taking such calls, offered their in-house customer service agents free therapy sessions.The reps we spoke to needed these jobs, which allowed them to work from home even before the pandemic. They included people with disabilities, caretaking obligations or limited opportunities in rural towns. Recruitment ads touted flexibility and the chance to be your own boss. But many agents discovered the roles came with limited hours, close monitoring and strict performance measurements that put them in constant fear of losing their jobs. A Department of Labor investigator concluded that one contractor, Arise Virtual Solutions, exerted an “extraordinary degree of control” over agents.

Most customer service agents are women. Many describe being sexually harassed. One said a caller told her, “I really like the way you type.” Their work belongs to a grim history of women in outsourced roles stretching back to the piecework manufacturing era. A half century ago, temp work exploded, driven by companies hiring women to cut costs compared with full-time employees. These magazine ads from 1970 and 1971 show how women temps were viewed at the time, and the attitudes have certain parallels to how customer service agents are viewed today. While many agents work full time, a growing segment are independent contractors who don’t get paid holidays, vacation time or fringe benefits.

The Kelly Girl “never takes a vacation … never has a cold … never costs you for unemployment taxes,” reads one ad reproduced by University of Buffalo sociology professor Erin Hatton in her book “The Temp Economy.” Credit: Courtesy of Erin Hatton

In the accounts below, most of the agents asked not to be identified, citing nondisclosure agreements that are common in the industry. (To work for some companies, agents must sign NDAs before they can even accept the job.) We’ve condensed for clarity and verified details wherever possible, collecting Facebook screenshots, email exchanges, company performance review forms, tax records and other proof of employment, along with contemporaneous recollections from agents’ relatives or friends. But there were instances in which we couldn’t get such documentation, owing in part to the premium placed on privacy and security by the companies. Some agents said they weren’t even allowed to have their personal phone in their workroom while helping customers. Some lost access to their email and the company platform when they quit or were fired, and they hadn’t made copies or screenshots beforehand. In every case we invited the companies that these agents worked with to comment.

Agent Taking Calls and Chats for TurboTax

Christine Stewart has social anxiety and depression. “I have a really hard time being out in public,” she said. She wanted to work from home, so she became an independent contractor for Sykes from 2017 to 2018. The company bills itself as “a leading provider of multichannel demand generation and customer engagement services for Global 2000 companies.” At Sykes, she helped customers using Intuit’s TurboTax.

“I was actually sick one day, I called, they have a supervisor line, and told them I was going to be [out] sick. And without actually saying it, the lady said, you’re going to be in trouble if you don’t show up. And me, I don’t like to get in trouble at work, I’m a good employee. I went to work. I kept hitting my mute button every time I had to throw up.”

During training, she said, “they told me if you wanted to work nights, you could work nights. If you want to work days, you can work days. Once you finish the training they’re like, ‘This is your schedule.’ I said I can’t work that and they were like, ‘Well, this is the schedule, and if you can’t work the schedule, you don’t want the job.’ I was like, ‘I need the job, I do want the job.’ I said, ‘I can do 8 a.m. to 12 p.m.’ They wanted me to do 12 to 12. I have to get my kids on the bus in the morning, I was like, ‘I need to take a five-minute break when the bus pulls up.’ Even that was a huge problem for them. They would say, ‘You can’t keep taking these five-minute breaks.’”Customers berated her. “One person called me the C-word. I’d call my supervisor. They’d say, ‘Calm them down.’ … They’d always try to push me to stay on the call and calm the customer down myself. I wasn’t getting paid enough to do that. When you have a customer sitting there and saying you’re worthless … you’re supposed to ‘de-escalate.’”

“There can be no background noise, no nature noises or cars passing by. I had a den. I had to insulate my den,” she said. (To confirm the expense, she shared a tax form with ProPublica that showed a $100 deduction.) “I had to turn the AC off; you could hear the AC blowing. They called me out on that. When I was training, the lady said she could hear the air conditioner in the background.”

One time, she said, “my kid broke his hand.” She dropped her call, dropped everything, to help him, but then she needed a story, because, she said, had she told her supervisors the truth — that her kid broke his hand and needed her help — “I would’ve gotten in trouble even if I had a hospital note.”

“I said my internet went down. I pulled the plug on everything, because it was their equipment. … I didn’t know if they had any kind of monitoring software that wasn’t on the webcam or anything. It was better not to take any chances and unplug the whole thing.”

Intuit told us that it “engages with vendors” able to deliver “flexible support,” and that it is “dedicated to providing a safe, ethical, and inclusive workplace for all of our employees and vendor workers.” (See the full statement.)

Sykes did not respond to requests for comment.

Agent Taking Calls for Bath & Body Works

She needed money for a medical procedure, so, during the pandemic, she began working for Liveops as an independent contractor, helping customers for Bath & Body Works. She worked from home.

For online orders, Bath & Body Works allows shoppers to use just one promotion per order. A customer, for example, can use a code to knock down the price of a particular item, but they can’t combine multiple codes. Customers can get upset when this is explained to them.

“We encounter customers who ordered the wrong items and want us to send them the right items for free. We receive calls from customers who have had their packages stolen. And then we get customers all the time who find out we don’t sell a particular fragrance anymore, and they can be just incredibly abusive.”

“I may as well say it out loud. We get called bitches all the time. One woman called me a ‘stupid fucking cunt.’”

“It can wear on you. We’re not allowed to answer back in the same way, nor are we allowed to hang up on them. Nor can we hang up on them after giving them one warning. The policy I am told is, we’re not allowed to hang up on any customer under any circumstances, even if they question our race or ethnic background or anything like that. My understanding is that we’re not even allowed to give people a warning.”

“We have to sit there basically and listen to these people until they run out of steam. It’s like they don’t see us as a person.”

With the pandemic, she said, a lot of agents are young women who lost their jobs and are desperate for anything. A lot of her fellow agents are Black women. “I’ve heard them say they were called ‘stupid n—–,’ ‘you stupid Black bitch.’”

Do You Work in Customer Service? We’d Like to Hear About Your Work-From-Home Jobs.

While some customer service reps are pressed to work more hours than they want, she got too few. Last fall, she signed up to work for four and a half hours during one day. She was paid 31 cents per minute of talking time. So when she wasn’t getting calls, she wasn’t getting paid. For those four and a half hours, she said, she sat there with her headset plugged in.

“No calls in those four and a half hours. Nothing. … I got some personal budget stuff done. Surfed websites unrelated to work. Familiarized myself with products on the website. I hate to say it, but I think I dozed off at one point.”

Were there other days in which you got no calls? we asked.

“Oh, yes.”

“How many?”

“I lost track.”

Liveops has quality auditors who listen to at least four of an agent’s calls per month, she said. They score agents using an audit form, which she shared with ProPublica. It says agents should make a “connected recommendation for each opportunity throughout the interaction” based on the customer’s orders. Say a customer buys soap. The agent should ask, “Did you want a soap holder, too?” If a customer buys candles, the agent should also pitch candleholders.

“A customer calls to say, ‘Hey, I didn’t get my package.’ So I’m supposed to say, ‘Hey, do you want to buy some more products when you still don’t have your package?’ Oh, for crying out loud. Really.”

The audit form has 20 questions. They include: “9. Did the agent compliment the customer’s selections, reassure about the fragrance choices and/or give general positive reinforcement about the items? … 18. Did the agent apologize when necessary, show empathy and/or recognizes customer emotion? 19. Did the agent let the customer know that we have ‘heard’ them, that we genuinely care, and did the agent remain engaged throughout the entire interaction?”

A Liveops document said that if an agent’s scores fall within the “unacceptable” range for three months in a calendar year, “the agent may be subject to removal from the program.”

She said she recently received an email saying she had used profanity on a call, so Liveops was terminating her contract. She didn’t remember saying anything profane. The company provided no recording for her to listen to. She emailed Liveops and called corporate to ask for details or a chance to hear whatever it is she was supposed to have said, but she got no response. (She said she didn’t make copies of these emails before her email account was closed.)

“No appeal,” she said.

Liveops told us that it does not comment on specific clients or agents, but said in a statement that agents choose their client programs and “have the freedom and flexibility to work around their lives.” The statement added: “All client programs have their own unique process for handling and dispositioning unproductive calls and significantly upset clients. There are controls in place to ensure that, to the extent possible, all calls are professional, and no customer or agent is subject to verbal abuse.” (Read Liveops’ full statement.)Bath & Body Works did not respond to requests for comment.

Agent Taking Calls and Chats for Barnes & Noble

She worked as an independent contractor for Arise Virtual Solutions, a company that bills itself as a pioneer in the work-from-home industry.

Customers, she said, “get mad at us. They start cursing at us. They start threatening to report us to the main office.” One customer, she said, told her he was going to keep her on the line until he got what he wanted; he “started with the F-word,” then apologized, then carried on. He “wouldn’t stop and wouldn’t stop” until finally, realizing the agent wouldn’t give in, he gave up.

At one time she handled calls from Barnes & Noble customers. “A lot of cursing, a lot of crying — crying — believe it or not. I’ve been called every name in the book. And I do mean from A to Z. Everything in between. I’ve been hung up on, threatened, told I’m going to lose my job. I had one woman tell me, ‘I hope you have a miserable day.’ You can’t laugh. I can’t laugh. I’m thinking to myself, ‘You ordered the Bible. You’re some Christian person?’ She’d ordered a Bible! Those are the worst! Those are the worst hypocrites! They scream, curse, yell, carry on, threaten. They’re the worst.”

“The women, their mouths are unbelievable. Or they start crying. They’re worse than the men. I’m like, ‘It’s a book, for God’s sake.’”

Arise told us that it does not tolerate harassment of any kind. (See the full statement.)

Barnes & Noble did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Agent in a Call Center Taking Calls for Sprint

She was employed by iQor (pronounced I-core) as a retention specialist and sales agent, taking calls from customers for Sprint (which has since merged with T-Mobile). She worked in a call center.

“If the customer is angry and wants to completely cancel, you have 14 minutes to resolve their issue, get them to stay and sell them a new phone,” she said.

A unit called workforce management would push agents along. One workforce management monitor would sit at a computer, checking the length of each agent’s call. Another would walk the floor. These two would communicate by walkie talkie, one alerting the other to any agent whose call was running long.

“At 10 minutes you had somebody tapping on your shoulder. At 12 minutes you had someone tapping on your shoulder and saying, ‘Wrap it up, wrap it up, wrap it up.’ At 14 minutes, ‘What’s going on? You need to wrap this up. You need to move on.’”

“We had this guy who would run around on the floor yelling, ‘Move it along, people, all hands on deck, move it along, move it along.’”

Agents would have management in one ear and customers in the other. Customers would often be insulting, sometimes shockingly so.

She remembered one customer in particular. “He was very, very upset. And it’s personal. You get called names. ‘I hope you fucking die.’” Another Sprint customer told her: “‘I hope when T-Mobile takes over, you all lose your fucking jobs, your fucking families, your fucking homes, and you all kill yourselves.’”She said she was not allowed to hang up. Only a supervisor could do that. “Where’s the line where you no longer have to take that?” she said. “I spent more than one instance in the bathroom, crying, then shaking it off and going back to work.”

“I’m pretty thick-skinned, and I had nightmares. It beats you down. Everybody is angry. Eight out of 10 calls, they’re angry and they’re cursing by the time they get to you. Usually it’s the men who make it personal. That’s why I coined the term AngryWhiteManistan. ‘I have another resident of AngryWhiteManistan here.’ They’ll say things like, ‘Well, then, you better get me someone who is not incompetent.’”

In her nightmares, she said, she would be doing some mundane task, such as making dinner in the kitchen, when the phone would ring. She’d pick up and hear: “Are you done yet? We need to move on. We need to move on. We need to move on.”

T-Mobile, which merged with Sprint in 2020, told us it wouldn’t comment on Sprint’s prior practices. Since the merger, T-Mobile said, it has taken steps “to align T-Mobile’s Care practices across our team and all our partners to our award-winning Team of Experts (TEX) model, which heavily prioritizes customer and agent experience over more traditional call center metrics.” The company’s statement added, “We have a long-held policy that all of our experts do not have to tolerate abusive speech or behavior.” (Read the company’s full statement.)

IQor did not respond to requests for comment.

Agent Supervising Other Agents Taking Calls for DirecTV

She’s lived in “many, many states” and worked in many call centers. Now she lives out west in a rural setting where jobs, and options, are scarce. A few years ago she found a job that lets her work from home. She started as an agent at Convergys (since acquired by Concentrix), then became a supervisor.

“It’s just enough of a wage that you’re going to be ineligible for most public support. I’m not eligible for any financial aid whatsoever. And yet I go to the food bank every month because I don’t make enough money. … I don’t go to the doctor, even when I should.”

She said the job attracts a lot of new parents. And retirees. And people with medical issues. She said that in her experience, the turnover is “tremendous.” Within months, many people get fired, or “termed,” short for terminated. “We fire more than they resign. A lot more.”

Most firings are over attendance. What counts as an attendance infraction? “Anything. It doesn’t matter if it’s in your control or not. … Your power goes out and, bam, you’re absent. … Doesn’t matter if you had a hurricane.”

“You don’t know if you’re going to have a job tomorrow.”

Once, as a supervisor, she listened to a recording of a call that had been made to an agent working at home, answering calls from customers for DirecTV. “DirecTV had a policy, you never hung up on a customer, ever. You simply weren’t allowed to, no matter what they said.” (ProPublica interviewed another agent who also understood this to be the case.)

https://d37c22024108c65aef247958a612fa8c.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-40/html/container.html“There was a guy who called in and masturbated on the phone. It was awful. … Just imagine being a woman in your office in your home, alone. And here’s this guy doing this, and it takes you a few minutes to figure out what that sound is, and when you do you’re horrified, and you don’t know what to do. All you know is, you’re not allowed to hang up the phone. That would be horrible. I felt so terrible for her.”

The agent, crying, asked if she could quit for the day without an attendance infraction. “We had the recorded call, it’s not like it was ever in doubt. My boss was a man, at first he didn’t understand why that was an issue.” He didn’t understand why the agent was so troubled. “I had to go to HR to get them to explain to him why it was an issue.” Only then could the agent stop taking calls.

Convergys was acquired by Concentrix in 2018. Concentrix said it does not disclose details about current or former staff out of respect for their confidentiality, but said in a statement: “We recognize that the work-at-home environment isn’t for everyone. … We take the health and safety of our staff very seriously and do not have a no hang-up policy. Our staff are given extensive training to manage each interaction with techniques to deflect and diffuse situations should they arise. If subjected to harassment or abuse they are trained and empowered to end the conversation.” (See Concentrix’s full statement.)

DirecTV told us: “The allegations are disturbing. We suggest you contact the agent’s employer.” In a written statement, the company said: “We don’t tolerate, and we don’t expect our vendors to tolerate, harassment of any kind. We have policies and procedures in place for our employees to escalate inappropriate customer interactions and the ability to terminate any customer interaction if and when that becomes necessary.” A DirecTV spokesperson said in a phone call that “to the best of our knowledge,” the company has not ever had a no-hang-up policy.

Agent Taking Calls for Home Depot

She’s in her 60s and wanted a work-from-home job to keep her family safe during the pandemic. She saw a company called Arise Virtual Solutions mentioned online, but she was skeptical. She would be an independent contractor, required to absorb substantial startup costs. (ProPublica’s previous article on customer service noted that Arise’s agents often spend more than $1,000 on training and equipment.)

Then she saw Bob Wells, a real-life nomad featured in the movie “Nomadland,” talking about Arise on YouTube. She decided to give it a chance. “I was like, ‘I need work.’ … I’d kind of given up on finding something more legit, frankly, because of the pandemic. So it was a pandemic Band-Aid for me.”

She answered calls from customers for Home Depot. One, a nurse’s aide, had ordered a portable toilet for a client. “This woman was like, ‘I have a 90-year-old lady who needs this thing like, yesterday, and you haven’t delivered it for three weeks, what is your problem?’” To the agent, this was urgent. “When it became a humanitarian issue, and there were plenty of humanitarian issues, especially during the pandemic,” she would send the matter to people above her, who would then send it to Home Depot to do something. The customer’s problem might then be resolved. “But my stats would go down,” she said, because she hadn’t resolved the matter herself. (She shared Arise’s performance metrics with us.)

On days when the phone didn’t stop ringing — and there were many — she couldn’t step away from her desk. “I had a bottle I kept under my desk in case I had to urinate. I never used it, but I had it there if I needed it. I’m in my 60s. … There could be an emergency.”

The work was isolating. She joined Facebook groups (and provided screenshots to ProPublica) and began to talk with other frustrated agents. She realized she was among the few white women in her work cohort. And she realized customers were nicer to her — an immigrant with a British accent. “When I first came to this country, I couldn’t believe people could tell the color of a person over the phone. That was a culture shock. … When people are calling in, I think they find it easier to yell at a Black woman. … I’m not the most evolved person, but I began to look at the work through a racial lens. … I answered the phone, and there were people who called, and right at the beginning of the call, they were full of white-hot rage.” Then they would hear her accent. “Well, the amount of comments I got from people who were like, ‘Wow, they’ve got classy people here!’ … I was born in a British colony. People think I’m a butler or a classy servant.”

Home Depot spokesperson Margaret Smith told us the company uses an escalation process designed to help agents handle difficult calls. “If a customer becomes irate or disrespectful, we ask the associate to either have their supervisor take over the call or transfer the call to the resolution queue,” she said. Agents who use this process are not supposed to be penalized, she said. (Read Home Depot’s full statement.)

Arise provided us with a statement about its network of agents, whom it calls service partners. “Arise does not tolerate discrimination or harassment of any kind,” the statement said. “Service Partners interacting with individual customers through the Arise® Platform are protected by both client and Arise policies and processes that include the ability to disconnect callers without penalty or transfer these calls to support resources if they are unable to de-escalate the situation.” (Read Arise’s full statement.)

Agent Taking Video Calls and Chats for TurboTax

Mara M. was a hairstylist and cosmetology teacher when her health began worsening. “Probably in about 2015, I started sleeping a lot. Any time I would stand up I would get really dizzy, really lightheaded. One of the requirements to teach hair is to be able to stand. I couldn’t stand up. It was a walker and wheelchair for me. … I have postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome.”

Mara eventually discovered Concentrix, a global customer service outsourcing company, while searching for work-from-home jobs on Indeed.com. She signed on at age 23, hoping she might be matched with a company that sold beauty products.

At her orientation three weeks later, Mara learned which account — that is, which of Concentrix’s corporate clients — she would be matched with. She would be working part time, doing video calls and live chats for Intuit. She would be helping people use TurboTax.

Mara didn’t have an office. But she did have a closet. So she turned her closet into an office. (She sent us photographs.) “They sent me a blue screen to put behind my chair,” she says. That way, customers wouldn’t know she was working from home, much less from inside her closet. She bought a computer, a monitor, a headset.

“We were not supposed to hang up. … You’re supposed to hear them out, then empathize with them, then acknowledge that the problem was made. I had tried all that. They say, you know, apologize, but the people stay angry.”

One customer called her, moaning. “I was very uncomfortable. I couldn’t tell if he was sick; I couldn’t tell if he was watching porn in the background. I just tried to get through the guy’s questions.” Afterward she told a friend that she thought the man on the other end of the line had been masturbating. (The friend confirmed this conversation.)

She learned that agents were monitored. “We had a webcam, and [the monitors] can see you through the webcam. … I’m not sure how often you were watched. But the trainer did say you should shut down your computer after your shift because they can still see you. I was like, that’s really Big Brother. … That freaked me out because I spend a lot of time in my room.” And she learned there were no built-in breaks for part-timers. “You can’t step away when you’re on the clock.” She said it felt confining, like her closet was a prison cell.

She struggled to answer questions about complicated tax forms. She would Google for answers in a different window while trying to look confident to the customer, who could see her on the video call. “I had a nightmare so bad that I’d wake up at 6 in the morning over this job. I cried. I’m a sensitive person, so a lot of people probably wouldn’t have cried. … I didn’t know what I was doing. … I was like, ‘I finally have a job, but I don’t know what the answers are.’”

Mara didn’t feel like she could quit. For the most part, she said, her metrics were high. But customers weren’t responding to survey questions about her performance. And her lowest score was her “doc rate” — documentation rate — which penalizes agents for not closing out a chat with a customer. They get credit only when a customer says, “Yes, you have answered all my questions.”

“Some people don’t answer back after they get the answers they need. For those types of chats and everything, we couldn’t close those cases. My doc rate dropped because … I couldn’t close the case on some of them.”

Eventually, Concentrix emailed to say that TurboTax wanted her off the account, citing “a review of stats … done over the weekend.” (Mara shared copies of the exchange with ProPublica.)

“I do apologize for the inconvenience,” a Concentrix representative wrote. “Please feel free to apply for other Concentrix accounts!”

Intuit told us agents are “provided training to end calls with customers should they encounter abusive or threatening behavior.” Its statement also said that Intuit establishes performance standards with vendors such as Concentrix: “Vendors — not Intuit — are responsible for ensuring those workers they engage to support Intuit’s customers or our account meet those standards.” (Read the full statement.)

Concentrix, which said it does not disclose details about current or former staff, told us, “We take the health and safety of our staff very seriously and do not have a no hang-up policy.” (See Concentrix’s full statement.)

…

Ariana Tobin, Ken Armstrong and Justin Elliott – ProPublica

Mollie Simon contributed reporting.

ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up to receive our biggest stories as soon as they’re published.

The Floor

By Robert Gumpert

Two “front of house” workers, a lead waiter and a bartender, speak about their jobs

For fullscreen view, click the little square in the righthand bottom corner next to the magnifying glass

Womack’s Labor Power and Strategy

By John Bowman

Labor Power and Strategy, order from: PM Press

Let me start with a confession. I am not affiliated in any way with organized labor or the labor movement. I have spent over 60 years as an editor of non-fiction works—American history, baseball history, art books, photography books, etc. That said, starting in my early teens I was expected to work at household chores (rolling coal ash can out to curbside, hanging storm windows). On my college vacations, one year I worked at a summer resort, another at the Monsanto chemical plant (then in Everett, Massachusetts, where the Encore casino now is), and another summer at a leather tannery in Woburn, Massachusetts (later charged with pollution—told in the book and movie, A Civil Action). And meantime, as a devoted reader of newspapers all my life, I have certainly kept up with the labor movement in our country.

In fact, indulge me in a personal tale that involves two items on my cv above. For some reason the tannery workers seemed to belong to the United Electrical Workers union (UE), then regarded as one of the more leftish, more radical unions. Every Friday a big stack of the union’s newspaper would appear. I watched to see if the workers would take an interest in the paper, but no—they grabbed a copy and wrapped their dirty clothes in it to take home to be laundered. I seemed to be the only guy who read it. So let’s say I write this as a fairly well informed American with a more than passing interest in the subject matter of the book under discussion.

The book is Labor Power and Strategy by John Womack Jr.—the highly respected Harvard professor and authority on the Mexican revolution. But although he is credited as the author, its two editors—Peter Olney and Glenn Perusek—played a major role in assembling the book, first by interviewing Womack for his contribution. Since the interviews took place in the Foundry, a restaurant in Somerville, MA, they are sometimes referred to as “The Foundry Interviews.” The editors then enlisted the ten individuals who contribute their responses to Womack’s extensive thoughts on the book’s subject—how to identify union power and use it—almost all with firsthand experience as union organizers and union actions. And by the way, not always agreeing with Womack—which is what makes this book especially engaging–and relevant. It is not just some Harvard professor’s highfalutin theoretical treatise.

It is a relatively small book –both in its page-size and page-numbers—but it is full of stimulating–and often provocative–ideas about the labor movement in our country over the last century and—above all– where it should be heading in the present century. If the book can be briefly characterized, I can do no better than quote the words of the historian Nelson Lichtenstein in the front of the book, where he poses the question at the heart of the book: “Are workers with vital skills and strategic leverage the key to a labor resurgence, or should organizers wager upon a mobilization of working people whose relationship to the economy’s commanding heights is more diffuse?”

In the course of the book, this is sometimes compressed to the structural vs. associational approach, and if Womack comes down on one side, it is the former. Structural in this instance refers to labor activists, union organizers, primarily going into the actual workplaces and seeking out what are called “choke points” — those crucial locations or processes that if stopped would bring the entire factory, workplace, delivery service, whatever, to a halt. The most prominent example of this is actually cited by one of the responders to the book—Gene Bruskin, who headed the campaign to advance the union’s demands at the Smithfield pork processing plant in Tar Heel, North Carolina. He describes how they identified a particular “choke point” in the process of converting live pigs into pork products and by ceasing to work there, a contingent of workers brought the whole operation to a halt. Their secondary demand focused on another “choke point” – where the trucks delivering the live pigs had to be unloaded.

A ”Womackian” analysis of the Smithfield case would stress that what was at work here was a structural approach: you just go straight into the workplace and disrupt the operation. But Bruskin explains that he also involved elements of the associational approach, launching a field campaign in the surrounding communities, seeking broad public support. And in fact, neither Womack himself nor any of the ten responders is an absolutist—all concede something to the opposing approach. Bruskin’s account of the Smithfield case—2005-2009—is the most detailed account of a specific union action, but numerous examples of such are cited, from the 1919 steelworkers strike to the 1930s automakers strikes, to the more recent strikes by West Virginia teachers and organizing among Nissan workers in Canton, Mississippi, and casino workers in Las Vegas.

I myself have a minor quibble with the book—or rather to Womack’s responses to the interviewer. He does go on, despite what I say above, with his theoretical ideas. And I might have wished that he discussed in a bit more “grounded” detail five of the factors that I, at least, see as bearing greatly on the labor movement in the decades ahead: the role of the waves of uneducated immigrants, the role of robots, the role of the Chinese, the role of electronification of work, and the role of the “gig” economy. But that’s for a different book–and perhaps a different author. This is Womack’s book. And if I, the individual described at the outset, can find it so enlightening and so engaging, then I think that anyone should appreciate reading it

.…

Please join us at one of a number of Labor Power and Strategy upcoming events with John Womack Jr. and contributors

ACORN: Alive and Kickin’!

By Wade Rathke

ACORN is the Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now, founded in June 1970, more than fifty years ago. Throughout its history ACORN has been a multi-issued, direct action, membership organization of low-and-moderate income families and lower-waged workers organized in their communities, housing blocks, and workplaces, both formal and informal. Originally begun as pilot project, and an affiliate of the National Welfare Rights Organization (NWRO) in Little Rock, Arkansas, the organization, ACORN International, is a federation of affiliates in more than fifteen countries with over 250,000 members.

If you’re surprised at the news of ACORN’s continued vigor and vitality, you may be an American, middle-aged or older, who knew ACORN as the half-million-member community organization and powerhouse winning bank agreements that facilitated homeownership for millions, living wage agreements covering tens of millions in more than 100 cities and states, registering more than one-million new voters each cycle, and winning countless victories at the local level in thirty-four US states, more than 100 cities, and countless neighborhoods. If you’re a millennial American, you may have a vague memory that ACORN was something big “back when” and was caught in some video firestorm, though the details were fuzzy. If you’re a Gen Z American, you may have read something about ACORN in a political science, sociology, or urban affairs course if you were college-bound, but, basically, you’re clueless.

But, if you are a tenant anywhere in England, Ireland, Scotland, or Wales, you know ACORN as your union in the community fighting to cap rents, improve conditions, win security of tenure, and put the brakes on letting agencies. If you live in Grenoble, Lyon, or the Paris suburbs, you not only know ACORN as your community organization, but if you are also a Muslim woman you know ACORN as your civil rights union that won access to you to participate in sports teams wearing a hijab and to swim with your children in public pools. If you live in Canada for the last two decades, you know ACORN at the community level from coast to coast in the dozens of cities where ACORN works and the six offices there where not only has it won community and tenant issues, but where it has fought payday lending, won internet access in national agreements, targeted housing financialization, blocked gentrification and “demovictions”, pioneered living wage victories, and more. If you live in Mumbai’s Dharivi

slums or are an informal worker in Delhi, Bengaluru, or Chennai, you are one of 50,000 ACORN members fighting for basic survival and your livelihood through the organization on a daily basis. The same can be said as members wave the ACORN flag and wear the ACORN buttons in Kenya, Cameroon, Honduras, Peru, Liberia, Tunisia, and other countries, including the United States as well.

Lowering the Predatory and Unregulated Cost of Remittances

ACORN has come together in campaigns that join our members across countries. One example is lowering the predatory and unregulated cost of remittances from North America and Europe to the countries in the Global South where we organize and have members, and have fought with actions and engaged in negotiations with MoneyGram (based in Dallas) and Western Union (based in Colorado). Campaigns against private equity housing REITs have linked ACORN affiliates in Ireland and Canada in actions and campaigns. Organizing originally in India to protect the livelihoods of hawkers, street vendors and others in India against the expansion of big box retailers like Walmart, Carrefour, Tesco, Metro and others found ACORN fighting continually against the expansion of foreign direct investment modifications in multi-brand retail, where in our India FDI Watch coalition, we both delayed adverse impacts and won significant restrictions to any expansion, while working with labor union partners in North America and Europe.

The Strength and Resilience of Community

ACORN’s strength as a grassroots membership-based organization was tested by the crisis of Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans in 2005 where we had 9000 members and our headquarters. That crisis proved the strength of our resilience and the value of a national community organization that could rally and respond to existential crisis effectively. The COVID-19 pandemic played a similar role in the growth and development of the multinational organization. In crisis, the members had to find support, and they found it together in collective response. Members stepped forward to help each other get groceries, make pharmacy visits, fight evictions, and more. Several thousand members volunteered for mutual aid in England alone in the first months of the pandemic. Membership growth soared across the organization, even though the door-to-door core of the ACORN organizing model was impossible for months, just as it had been in Katrina, recording record growth in France and Canada, and a doubling of the membership in England, Wales, Scotland, and India. This was not a campaign any of our members, leaders, or organizers wanted or designed, but in classic organizing fashion confronting the situation once again proved the ability of the organization to adapt to crisis, meet our membership’s interests and issues fully, and by doing so grow in reputation, numbers, and power in response to the challenge.

Currently, ACORN’s major international campaign on housing retrofits unites most of our countries around both their housing needs and their concerns about climate change and its terrible financial burden on our members. With victories and commitments already won in France mandating housing upgrades for housing units judged in the worst two categories, ACORN is now expanding the effort to upgrade housing along the same lines to prevent the loss of heat and lower energy costs throughout the United Kingdom and the European Union. ACORN in Canada has won some retrofit resources, though Ontario’s prime minister Ford vetoed some of our initiatives when he took office. The Biden administration’s recovery bill also included some need support for retrofits.

ACORN’s global reach continues in earnest though we struggle to keep up with the invitations and demands. We were on the brink of additional expansion as the pandemic intruded on fledgling efforts in Belgium and the Netherlands. Now, coupled with the retrofit campaign, the energy poverty provoked by the Russian invasion of the Ukraine, and the ongoing housing crisis, these initiatives have gained urgency with committees forming in Brussels, Liege (both in Belgium), Amsterdam, and Heerlen (both in Netherlands) that seem ready to mature in these two countries in 2023, with Germany likely in 2024 as part of the “just transitions” program. Early work has also begun in Melbourne, Australia, and Wellington, New Zealand, as the organization’s work and reputation continues to spread and provoke interest.

In the United States

Of course, in the United States, ACORN is both the same and different. Different in the sense that after the video scam and coordinated rightwing attack on the organization in 2009, in 2010 the US organization reorganized from one centralized organization into independent statewide formations that reconstituted themselves. They sometimes coordinated but were mainly dedicated to local and statewide issues in the dozen of places where they survived in alternate formations with reconstituted the membership in California, New York, Texas and elsewhere. Founded and supported twenty years ago in response to demands from ACORN members who had immigrated to the USA but wanted the organization to make a contribution in their home countries, ACORN International continued to organize without interruption as a multinational federation carrying the torch and tradition forward.

ACORN is the same in the sense of still maintaining and developing many pieces of the longstanding, historic ACORN family of organizations with continuing direct community and labor organizing work among low-and-moderate families and workers. The ACORN headquarters remains in New Orleans, with our new building cattycorner to our old building, still at Elysian Fields and St. Claude Avenue, where the stoops face each other across the intersection. This location continues to be home to our Louisiana affiliate, A Community Voice, as well as Local 100, United Labor Unions(originally ULU and for 25 years part of SEIU) working in Arkansas, Louisiana and Texas with offices in Little Rock, Dallas, Houston, and Baton Rouge as well.

New Developments

There’s nothing like volunteer-run, member-supported community radio working as a megaphone for the dispossessed to speak truth to power and support progressive organizational forces for change

One new development can be seen from the street as you look up and see an antenna rising at the back of the building’s second floor, where the Affiliated Media Foundation Movement won an FCC license and built a low-power station, WAMF, which went on the air four years ago. WAMF joined 100,000-watt KABF in Little Rock, managed by AM/FM, KOCH that we co-manage in the Nairobi Korogocho megaslum, our internet membership station acornradio.org, and our newest internet license radioacorn.org in Uganda which is preparing to go on the air. Since we first went on the air with noncommercial radio in the early 1980s in Tampa, Little Rock, and Dallas, now by sharing software across the affiliated stations the New Orleans studio can assist in programming all of these stations. Our long-held dream of a “Voice of the People” network of stations devoted to giving a platform for low-and-moderate income families on-the-air achieved a breakthrough winning approval for the construction of seven full-power terrestrial stations (50,000 watts to 7500 watts) early in 2022. The one in southeastern Arkansas (KEUD in Eudora), once on the air, could link to the central Arkansas station’s coverage in Arkansas, as well as much of the Mississippi Delta counties and Greenville, where we also managed a station. The other licenses in development include: three in Colorado and three in New Mexico. Under the FCC rules, we have another two years to put all of them on the air, but that will depend on whether or not people understand the importance of organizing and giving voice to people in many of these strongholds of “red” America. There’s nothing like volunteer-run, member-supported community radio working as a megaphone for the dispossessed to speak truth to power and support progressive organizational forces for change, but sometimes we wonder if anyone other than conservative evangelicals continue to understand the tremendous power of the medium?

Research, Reporting, Reactions

Labor Neighbor Research & Training Center is also headquartered on St. Claude, where LNRTC publishes the quarterly journal, Social Policy, for academics, activists, organizers and other progressives, as well running Social Policy Press. Labor Neighbor also continues to house the Organizers’ Forum, as it has for the last twenty-years. Despite a pandemic hiatus, Organizers’ Forum is planning for a delegation to reprise our first international dialogue, by returning this fall to Brazil to evaluate the second act of Lula de Silva. We will meet with other progressive organizations to update our understanding and their experiences, since we were there on the eve of his first election. LNRTC also has joined with ACORN and Local 100 ULU, employing our “volunteer army” of interns from Tulane University, University of Ottawa, Denver University, and other institutions to jointly undertake and publish research reports valuable to our membership and undergirding our longstanding campaign commitments.

We have done several reports on healthcare in recent years, largely focused on the failure of tax-exempt, nonprofit hospitals to provide charity care, both as required in the special amendment to the Affordable Care Act (Obamacare) and their 501c3 status. Most of this work has been within Local 100’s organizational footprint of Arkansas, Louisiana, and Texas, where we have found that an additional billion dollars of free health care to lower income families could be made available by nonprofit hospitals if they simply hit the average, though inadequate, percentage nationally for charity at less than 4% of gross revenues. Recent work by the New York Times and Wall Street Journal has echoed our work and verified our conclusions. Hospitals need to either provide substantial free care or the IRS needs to withdraw their tax exemptions worth billions to them.

Another key joint report which has had significant, though not comprehensive impact, has been on diversity and governance in rural electric cooperatives through ACORN’s Rural Power Project. In 2016 and again in 2021, we reviewed IRS 990s for all of the co-ops in the twelve-state area of the South and found that in all of the states, regardless of the demographics, these ostensibly membership-run, democratically-elected bodies were governed inordinately by older, white men with women and minorities (often majorities) rarely having even 10% of the seats. There was only marginal change five years later. We have developed a mammoth organizing proposal to focus on these issues and the cooperatives resistance to alternative energy sources. Currently, we are making slow progress in list building and geo-mapping in preparation for a field, communication and organizing program in the South and West.

With a history of voter registration and electoral participation of our membership dating back to 1971, ACORN has been especially concerned about voter suppression efforts in recent years. Beginning in 2019, in partnership with the Ohio Voter Project, ACORN organized the Voter Purge Project (VPP) after achieving restoration of 40,000 voters to the rolls based on an error by the Ohio Secretary of State’s office. In the run-up to the 2020 election, we had acquired voter lists and regularly processed a dozen states to monitor purges, both routine and worse. We implemented a texting program to hundreds of thousands of voters in these states before the 2020 election alerting people that they had been purged, and linking them to re-registration, if appropriate. In the Atlanta area we put a team of 15 canvassers in the field to get voters out before the January 5th runoff in Georgia where purges had been a critical issue. In 2022, we entered a partnership with Catalist, the DC-based liberal data operation. The VPP has now processed more than thirty-five states on our way to building a voter database list that we can constantly renew and monitor for all fifty states.

Having built this kind of database operation in New Orleans, we are now doing tests on phone matches and texting programs from voter lists with phone numbers to areas where unorganized workers are concentrated. We are doing the same within the service areas of rural electric cooperatives in order to see if using these lists can spawn organizing opportunities among those interested and unorganized. ACORN and Local 100’s project the Workers Organizing Support Center, are implementing a test in central Florida to determine interest in organizing to gauge the viability of this movement moment. ACORN and WOSC have been supporting dollar store workers efforts to organize and win their rights with these low-wage companies in that area, as well as in metro-Atlanta. We have a joint project with Georgia State University to assess stores and their workers in the 170-dollar stores in the area. On the co-op front, we are implementing a similar test among members of rural electric cooperatives on the questions of alternative energy and current utility pricing, to gauge the interest in governance changes from the membership base in Arkansas and North Carolina.

The Future

In addition to the rebranded old ACORN affiliates, there are activists around the United States looking to ACORN’s history and successes internationally, and domestically, as models for moving forward. In 2023, we’re taking our decades of shared lessons to create the ACORN Organizing School: a program that trains organizers in the elements of the ACORN model. In Memphis, Atlanta, Philadelphia, Boston and Baltimore, we’ll be preparing students, organizers, and activists to launch ACORN organizations of their own. As part of this effort, we’ve also launched ACORN Advocates. ACORN Advocates are monthly sustainers who meet quarterly with ACORN leaders to discuss opportunities and developments in our affiliates around the world. People want to organize here and around the world, so we are trying to scale up to meet the demand, and it takes a deep bench to sustain and grow the organization.

Using the time-tested and effective ACORN model in countries around the world, ACORN is still doing what it has always done: campaigning in the US for workers’ rights and concerted action, voting rights, cooperative diversity, governance to achieve alternative energy objectives, access to healthcare, building ground up community, tenant, and worker organizations.

It’s going on 53-years and we’ve changed with the times to meet the demands of our constituency and membership in different organizing environments. Every community, every city, ever state, province, and country are different, but lower-income and working families have issues. They want to build organizations wherever they live, to win power and make change against all obstacles.

This has always been ACORN ‘s mission, and it continues to be ACORN’s work. Support and join with us in this struggle!

…

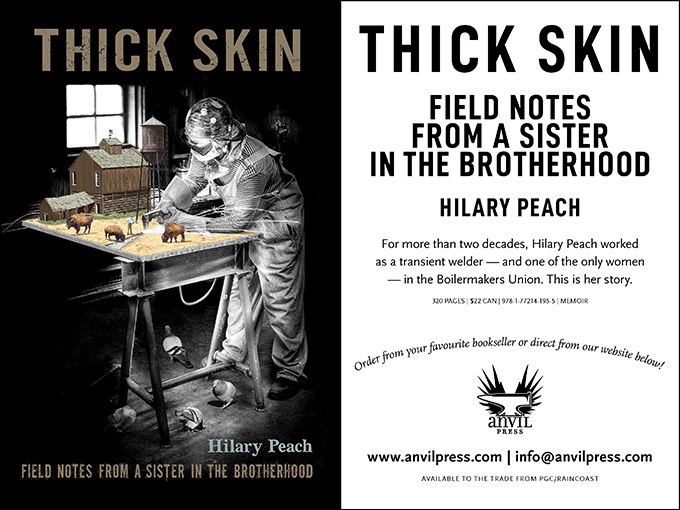

Thick Skin – A Review

By Molly Martin

A woman navigating the challenges of the male workplace makes a good story and Hilary Peach does the genre proud in her new book, Thick Skin. A Canadian from BC, Peach writes of working for twenty years as a boilermaker on big projects in Canada and the U.S. She has worked at coal fired power plants, the tar sands in Alberta, pulp mills, gas plants, shipyards—big industrial power generating companies of all kinds, often staying in their company towns.

I enjoy reading about the work people do, especially hard dirty jobs like construction. In this book Peach tells us about the world of boilermakers, a subculture all its own. She describes the often-difficult working conditions while she schools the reader about the intricacies and art of welding.

Most stories center on the men she works with, the psychopaths as well as the nice guys.

She encounters sexism and discrimination regularly as might be expected as the only woman among hundreds of men. But Peach always finds humor in the stories and often had me laughing out loud. Tradeswomen who go through the same challenges in our workplaces will delight in her creative comebacks and her various inventive ways of responding to harassment.

“How do we know it’s sexual harassment?” asks an apprentice.

“Just stop talking about your penises. That’s 80 percent of it,” say the women in the break room.

I loved this book. It’s well written and an engaging read with truly general appeal. And, of course, it reminds me of my own experience working construction.

Electricians, too, have a subculture of travelers, boomers, tramps, journeyworkers—those who travel around to different jobs—and my sisters and I used to dream of traveling. We thought it would be the greatest thing—that is until we heard from others who were on the road, mostly because they couldn’t get work in their own union locals. Sandy said she had to wear so many layers of clothes working in the Boston winter that her arms stuck straight out at her sides. Barbara of NYC told about burning refuse in high rises to keep warm and to help the concrete set, risking the hazards of smoke inhalation. Betsy complained of the Texas heat and miles of smelly porty potties.

Maybe we didn’t want to travel after all.

Hilary Peach does it for two decades—driving hundreds of miles, often in the driving rain or snow, to get to a job. Staying in work camps whose last century accommodations have been condemned and then reopened without remodel. Working 12 hour shifts happy for the overtime, working nights, working in cramped quarters in the freezing cold and boiling hot.

As the hard hat sticker says, “If you can’t stand the heat get the fuck out of the boiler.”

Peach does indeed develop a thick skin. A favorite maxim, repeated often: “You don’t bleed in the shark pool.”

Later, as more women begin to come on to the jobs, they tell her conditions have improved. She writes, “When other women were on the job it made a remarkable difference. One other woman and you are no longer the freak, the anomaly. You have an ally. Three or more, and everything changes. We can no longer be isolated and targeted in the same way…Someone has to organize a second bathroom.”Thank you, Hilary Peach, for making women look good out there and for paving the way for more women to enter this industry. A published poet, she’s now working on a novel. As boilermakers say at the end of a job, “See you on the next one.”

…

“Yellowstone” Is a Conservative Texas Rewriting of the American West – And Also Great Television

By Steve Chapple

Democrats Best Take Heed

I wrote a political opinion piece on the hit TV series “Yellowstone” for the newspapers, (see below,) and then “1923,” the sequel to “Yellowstone” debuted, and so here we go, HOT GLOBE™ high-tails it into the tremulous world of movie criticism.

OK, first episode of “1923.” Wow. Age 77, Helen Mirren as Cara Dutton slaughters some immigrant sheep herder with a double-barreled shotgun. Cut to Kenya. A Dutton progenitor fires what I guess is an elephant gun at a charging lion which in death falls upon him. Things do not slow down. Back to the Yellowstone. The stalwart cattlemen heroes led by Harrison Ford tell the immigrant sheepherders to get their stinking, close-cropping sheep off the cattlemen’s leased and drought-stricken land.

It’s “The Sheep Wars,” which I’d never heard of, so I did a little digging, since I was born in Billings, Montana, along the Yellowstone River, myself, as was my father, in 1893, and my grandfather was the mayor in 1882, with Liver-Eating Johnson (recall the Redford movie?) his sheriff, and Calamity Jane helping out during outbreaks of tuberculosis. (When you read about Montana in the East Coast or LA press, you are following someone who wouldn’t know a quarter-horse from a wombat. See my Harper Collins NYT Notable, Kayaking the Full Moon.)

First, there were no sheep wars along the Yellowstone, to speak of.

In Montana, the real money was in copper and gold mining. It still is, along with software. However, I discovered “The Sheep Wars,” were very much real, just more of a Texas, Wyoming, Arizona thing, and they happened long before 1923, more like the 1870’s to about 1909. Native herders were beheaded, ISIS-style. Tens of thousands of sheep were driven over cliffs. Lots of people got shot, mostly by the Harrison Ford side. Interestingly, the sheep owners were often not small-potatoes immigrants, at all. Sheep ranchers lost tens of thousands of dollars, worth millions now, in these depredations by masked cattlemen killers. The fights came to an end in Big Horn County, Wyoming, where to the surprise of all, sheriffs arrested a group of murderers, and they were sent to jail. Resource wars. Now we just invade other countries for their oil.

Up in Montana, along the Yellowstone River, it was homesteaders vs. the ranchers. The early ranchers made their money grazing on the open range left after 30 million bison had been slaughtered in order to starve out the plains Indians and force them onto reservations. Homesteaders under federal law were allotted some 160 acres, which they fenced in. In their war upon immigrant farmers, not sheep ranchers, the members of the Cheyenne Cattleman’s Club in Wyoming proceeded one drunken night to hang a woman sodbuster and started out to gun down families. But in Montana, the farmers and miners stopped Ford’s killer crew, who simply did a My Lai on any small farmer they could find. That’s why until recently—that is until Donald Trump and “Yellowstone” came along, Montana was as different from Wyoming as Vermont is from New Hampshire.

Caveat: the sequences in “1923” in the “Indian Schools,” from my knowledge, are harrowing and all too true. Director Taylor Sheridan’s earlier feature “Wind River” is one of the strongest movies ever made about racism and rape.

“Yellowstone” is superbly written, filmed and acted television, great entertainment for those who have never heard of it since, alas, they are too busy binge-watching “White Lotus” (also great television) and it celebrates some true non-Trumpy conservative values like hard-work and patriotism. The Ankler.

But it’s not Montana.

There’s some brilliant borrowing, “The Ghost and the Darkness”, “Heaven’s Gate”; “Legends of the Fall”, “Dances with Wolves”, “Leopard George”, a whiff of the “Snows of Kilimanjaro”—the best stuff ever, even “Heaven’s Gate” which is worth a rewatch of the director’s cut–and some others I’m not filmic enough to whiff out.

But face it HOT GLOBE™ historians, who’s going to watch a series about the real “Yellowstone” of 1883-2023? Unarmed copper miners fighting Pinkerton goons and Boston banks? I mean, where’s the fantasy in that? That’s real life. Some complain about all the gun violence in the series but, hey, Manhattan and Santa Monica, it’s fun to wear a pistol on your hip and pling away with a Glock at the target range even if—

and this is extremely difficult for American viewers to wrap their heads around, but nobody ever carried guns in the old West except maybe way down in Texas, and is Texas the West? Really? Bang-bang is all dime-novels, ‘50’s western reels, John Wayne, the “Hateful Eight”, ad nauseam.

My father had an original 1911 model Colt .45 from his days in WWI and we had a Sharp’s rifle from earlier buffalo massacres hanging in the library, so one time I asked my dad if people wore pistols on their hips like in all the tv shows and movies.

“No, of course not. Once in a while if someone was riding across open prairie he might take a long gun for snakes, but pistols in those days were too inaccurate.” My father never saw anybody wearing a pistol, he said. He was born in 1893, which would have made him 30 years old when the pistol-packing Duttons, Harrison and Helen came along.

The day Hollywood makes Westerns without guns will be the same day they shoot the movie about miners fighting for better wages. Where’s the romance in that? Ain’t gonna happen.