What Can Amazon Organizers Learn From Walmart? Dialogue moderated by Alex Han

By Alex Han

“Amazon is the epoch-defining corporation of the moment in a way that Walmart was two decades ago,” said Howard W, an Amazon warehouse worker and organizer with Amazonians United, a grassroots movement of Amazon workers building shop-floor power. What can organizers at Amazon learn from the Walmart campaigns in the 2000s? And what can these two efforts teach us about organizing at scale? Unions haven’t successfully organized an employer with more than 10,000 workers in decades, so getting to scale is one of the most pressing challenges for the social justice movements.

To explore these questions, Howard was joined by Wade Rathke, who, as chief organizer of ACORN in the U.S. from 1970 – 2008, anchored a collaboration among ACORN, the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) and the United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW) that aimed to organize Walmart. Since 1980, Rathke has also served as Head Organizer for Local 100 of the United Labor Union, which represents service workers in Arkansas, Texas and Louisiana. Organizing Upgrade Executive Editor Alex Han facilitated the conversation, with participation from International Longshore and Warehouse Union Organizing Director Emeritus Peter Olney. The 90-minute conversation ranged from the philosophical to the granular. We’re bringing it to you in three parts, beginning with a look at worker organizing. Part 2 focuses on relations with existing unions, and Part 3 on building broader community campaigns.

This 3 Part dialogue is being published jointly by the Stansbury Forum and Organizing Upgrade.

Part 1: One Shop at a Time

Alex: Wade, you worked on a project that approached organizing Walmart from a lot of different angles. Can you tell us a little about that?

Wade: We were trying to determine whether Walmart workers were willing to join a union and whether—just as importantly—they were willing to join a union that was very deliberately not going to file for an NLRB election, and made no promises of collective bargaining. We wanted to go directly to workers in the same way that ACORN would go directly to people in the community and ask them to join the organization to take action on the issues they saw in the community. We would go directly to Walmart workers and ask them if they wanted to take action on issues they saw in the workplace, whether that was hours, scheduling, wages, etc., etc., much in terms of shop-level action.

At that particular time—you’re talking about early 2005—4% of Walmart’s gross came from Florida, so it was one of the strongest states. We chose the I-4 corridor running between Orlando and Tampa-St. Pete, about 21 counties, a whole bunch of stores that they had already planted, but also a serious piece of expansion that they had proposed there. We built an organizing staff. ACORN already had an office in Orlando as well as in the Tampa area. One of my key associates and brothers was based in St. Petersburg so we knew people. We knew the turf. We were able to get established very quickly.

Obviously, we didn’t have a list of Walmart workers. We got the Florida voter list, and then we did a query to pull out all the addresses. At that time, it was populated with addresses and phone numbers, and we pulled out all the ones for families making less than $50,000. We did a simple robo-dialed prompt system where we called people who we thought were likely Walmart workers asking if they had worked for Walmart or had people in their family who worked for Walmart. There might be rights and benefits. If they were eligible, press 2, if they were interested, press 1. They’d press 1, give us their address and we’d come visit with them.

We had about 20 organizers so every night we would collect all the yesses, put people on the doors. The organizers in that piece of turf drove hundreds of miles sometimes to do three or four visits, and sometimes were lucky to actually complete any visit. For all of the union drives I’ve ever done, and there are many, we had the highest percentage of sign-ups on visits that we’d ever had, somewhere near 63% of the people who were Walmart workers who we actually got to visit would immediately sign up, and they were willing to join and pay dues. They signed up for the Walmart Workers Association. It was a membership card much like the ACORN membership card. They agreed to pay $10 US in dues per month, in an open-ended bank draft.

And that was surprising to me, how much interest and heat there was in the workforce about wanting to join this. And, once again, we were saying we’re not going to file for election. There is no collective bargaining. We’re not promising a damn thing other than you come together with your fellow workers. You can take action on the grievances and issues you have.

‘We Run The Place’

Alex: Howard, can you tell us about the concept around Amazonians United, the kind of organizing that you’re doing, and what’s happened as a result of that organizing?

Howard: The concept behind Amazonians United is that building collective power on the shop floor is foundational to changing the circumstances of workers at Amazon. Our power in making Amazon run is the thing that is needed to make any big change. We realize that Amazon is known for its huge size but also its far reach, so to make the biggest and most fundamental changes in it, the work will have to be more complex and involve more people that are touched by Amazon in more ways. But without Amazon workers forming that base, a lot of the rest of that work probably won’t go anywhere because we have the strongest position, because we run the place.

We’ve been organizing Amazonians United for about three years now. There are workers involved in Amazonians United that have been there longer than that, but we’ve been working as Amazonians United for about three years. In that time, Amazon has had a lot of press about its working conditions, its safety record, the intensity of the work, the inhumanity of a lot of the working conditions, and not a lot has changed. But when we in our warehouses have come together and done actions even as simple as a petition, and getting the super-majority of our coworkers to sign on to a list of demands, we’ve seen local management—which pretty consistently across the whole Amazon network is aloof, condescending, treats us like robots half the time and children the other half of the time—immediately sit up and, for the most part, rush to meet our demands, especially when they are demands that are within the warehouse. We’ve found it more difficult to make progress on bigger demands, like demands for a raise or demands for things that are really happening at a corporate level. Our work has been mostly warehouse by warehouse.

One of our very early victories that says a lot about Amazon was a fight for clean drinking water at the Chicago warehouse, where Amazon management had not been providing bottled water. They’d been providing those five-gallon bottled water fountains, but there was visible scum floating in the water. Workers had been demanding fresh water—this is in the middle of a hot summer, working intense shifts. Management had kept putting people off. “Oh, yeah, yeah, we’re working on it, we’re working on it, we’re working on it.”

And so then finally our folks started coming together and forming up as a crew, passed around a petition, got a super-majority of coworkers signed on, and confronted management with it at one of those standup meetings that started a shift. The manager became visibly scared, immediately got on the phone to his supervisor, immediately left to the store to get bottled water. Within the next week, clean water lines were being run throughout the warehouse and fresh water was being provided. In a lot of ways, it’s depressing that we had to fight for it, but it shows the power of workers to turn circumstances around in the warehouse very quickly in these cases.

Safety Walkouts

The New York warehouse that’s organized into Amazonians United was actually the first warehouse where there was an acknowledged case of the coronavirus in Amazon’s network. And the reason it was the first acknowledged case of the coronavirus is not that Amazon came out and said it. Workers there were organized and when one person got the news that they had tested positive on a very thinly staffed afternoon shift, they told a couple of their coworkers as they were leaving. Those coworkers passed it around to the rest of the organized crew, and the night shift that was coming in a few hours later.

A few of our folks showed up early, stopped everyone from coming in, told them what had happened. This was back when we didn’t know how the virus was passed. There was an impromptu rally in the parking lot. Workers refused to go in until serious cleaning had been done. Amazon agreed to shut the place down for two days, do cleaning and pay everybody. And that then began Amazon’s actual serious response to COVID. I can tell you from working in the warehouse that there was a real switch that was thrown at some point, in that Amazon was very clearly pretending it was not a problem and then all of a sudden, they started really taking it seriously.

In Chicago, the crew actually walked out for several days, demanding a serious response to the coronavirus. And that was one of the times a worker organization has been paired with community support, because when workers were walking out and were picketing the workplace, community members organized a car caravan to come by and show support and also create a bit of a jam for all the delivery vans trying to get in and out.

When we start organizing, we build up our organizing committees, we take action, we start changing the narrative in our warehouse. I think a lot of folks in warehouses assume that the problems that we have are unique to us and that everybody else has it better. And that clearly Amazon, leading light of the modern economy, the whole thing couldn’t be run as poorly and be constantly broken and duck-taped together as our warehouse, right?

Building Community

One of the things that we’re able to do as a network is meet each other as organizing committees and bring each other together as workers—not just as the organizers who are talking to each other a lot more, but as everybody who is in some way involved in the organizing in the warehouse. And they come and you can just talk shop.

We’re trying to figure out other things. We have a closed Facebook group for members of Amazonians United and people interested in Amazonians United who work at Amazon. We’re publishing newsletters, we’re trying to figure out ways that we can bring each other these stories in order to forge these connections.

Part of our work is building a meaningful community at work and a meaningful project for people to help them stick around. ‘Cause yeah, like the warehouses are very alienated places, a lot of them, right? People cycle through a lot. A lot of times the work is very isolated. People get ground down so much by the work that when you go on break everyone’s on their phone, talking to the people they really care about. In some cases, there is community there; in some cases, it takes people very intentionally being friendly, sharing food with each other, inviting people to cookouts and organizing potlucks and whatnot. Yeah, and building that community that then can be the basis for fighting for our lives.

If you’d like to learn more about Amazonians United, check out their website at amazoniansunited.org/. If you’re interested in joining the movement inside Amazon, you can submit an inquiry here: https://airtable.com/shr5Bq5sTeMweqJ7f.

End Part 1

In Part 2: What Can Amazon Organizers Learn From Walmart?

…

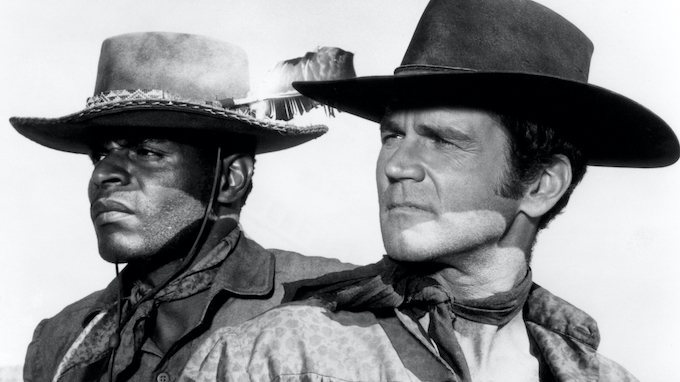

The Harder They Fall – Ruminations on its antecedents

By Gary Phillips

After viewing Jeymes Samuel’s The Harder They Fall stylized western, I got to thinking about when I was a kid watching Have Gun, Will Travel with my dad. This was in the days of a few local channels on television and three network ones. The weekly half hour show was on CBS and in black and white. I really only remember from then the show’s opening sequence. It’s a sideview shot of a black-clad thigh, a silver bishop’s chess head, also called a paladin, on the holster of the Shakespeare quoting gunman who goes by Paladin. He would draw the gun and aim it toward the audience. You’d also hear his voice over, a snippet of tense dialogue from the upcoming episode.

Having years later seen those episodes on the likes of Starz Encore Westers you can’t ignore the racist stereotypes of Hey Boy and later Hey Girl, the immigrant Chinese bellhops working at the Carlton Hotel in San Francisco where Paladin lived. Though to some extent theshow’s creative forces, including the star Richard Boone who had script approval and directed several episodes, were seemingly aware of the cultural landmine they treaded. There was a Paladin outing where he helps Hey Boy avenge his brother who was killed by a racist. While in another episode a character notes, “I have no contempt for the Army, exterminating the Indian nation is a dirty job, and they do it as well as the next.”

There was even an episode with a black outlaw hunted by Paladin, a wanted man with a $5,000 bounty on his head. This Rufus Buck/Deadwood Dick stand-in, played by Ivan Dixon,was called Isham Spruce in the “Long Way Home.” Like several real-world black cowboys including first Black deputy marshal Bass Reeves, Spruce is an ex-slave. He turned to outlawing as his perspective was that was the only viable means of making a living, a way of being free it might be interpreted these days. Initially he tells Paladin he’s no better than a slave catcher. The two develop a rapport even as four other greedy white bounty hunters dog them. But this was early sixties network TV. There was to be no team up of the two, no images of a defiant black man taking up arms against his would-be jailers. Essentially the milk toast ending has Ishamsacrificing his life to save a rattlesnake bitten Paladin. Good grief.

It would be in the late sixties ABC show The Outcasts, premiering in the fall of 1968, where a fully dimensional Black cowboy would finally ride across the small screen. A character owing more to the socio-political climate of the time than Sidney Portier’s well-dressed gunfighter in the 1965 film, Duel at Diablo or jazz singer Herb Jeffries’ Bob Blake, the Bronze Buckaroo in several “B” films made in the late 1930s.

At any rate, the following description from the getTV blog best describes The Outcasts:“Don Murray stars as Earl Corey, a former Confederate soldier – and slave owner – from a once-wealthy, now-destitute Virginia family. Otis Young is his reluctant partner Jemal David, an educated former slave [and ex-Union soldier]. Together, the two men navigate the West, and their own prejudices, as bounty hunters.”

The “My Name is Jemal” episode opens on a familiar scene, men drinking booze and playing poker, one of them sassing a good-looking saloon gal. Only the trope is subverted, the guys playing poker are mostly black, some in their Army uniforms, and the woman is black as well. In the “Night Riders,” the partners’ trust is tested when Corey is recruited to lead a Klan-like group out to terrorize and murder people of color and those who support them.

Otis Young was an unknown actor at the time who brought a freshness to the role. His Jemal David was a man with an edge for good reasons. Yet the relationship between his character and Murray’s deepens over the ensuing episodes. The show only lasted the one season. The claim was the program was canceled for being too violent. Don Murray quoted on the getTV site differed. “Murray told the L.A. Times that the political climate of the times hurt the show. “[A] lot of the audience felt very uncomfortable turning it on and seeing these two guys so hostile to each other,” he said, “even when saving each other’s lives.”

The Outcasts gave way to 1972’s The Legend of Nigger Charley on the big screen. As I noted in a previous piece this film stars ex-pro football player turned grindhouse auteur Fred Williamson. The movie was about escaped slaves becoming gunfighters, spawning the sequels the Soul of Nigger Charley and Boss Nigger. In several ways the Django Unchained of its day.Samuel’s effort is not only in a lineage with these aforementioned films, but also nods to Leone’s and Carbucci’s spaghetti westerns as well as Mario Van Peeble’s revisionist Posse of nearly three decades ago. In that film another western trope is sent sideways when a group of black soldiers, led by Van Peeble’s Jesse Lee, tired of being shot at during the so-called Spanish-American war in Cuba, steal a trove of gold. Pursued, they escape to New Orleans, trying to make it to a place called Freemanville, an all-black enclave started by Jesse Lee’s dad who was murdered by the Klan.

Another pro football player turned actor, Woody Strode is telling us the audience the story in the beginning of the film. Van Peeble’s understood his status in his reconstruction of the West from a Black perspective. In 1962’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valence, Strode had the ignominious role of Pompey, manservant to John Wayne’s gunslinger turned rancher. But he would go on to play better roles such as a bow-and-arrow toting bounty hunter in The Professionals, and an outlaw in the spaghetti western, The Unholy Four.

Yet as The Harder They Fall indicated, Black women such as Mary Fields, known as Stagecoach Mary, were not exactly shrinking violets in those times. No knock on how Mary was depicted in Fall, but the real woman’s story was so much more. Six foot and able with a rifle, she hauled freight for nuns, faced down bad hombres in shootouts and was the first Black woman to have a mail route in rugged Montana terrain in her sixties. Her life and times is a miniseries waiting to happen. The expansion of the Wild West mythos is long overdue, from John Horse and the Black Seminoles to Chinese and Japanese settlers have yet to be reframed on screens big and small.

…

Mostly a crime fiction writer, nonetheless Gary Phillips has written several western short stories including one in the Bass Reeves: Frontier Marshal anthology.

Working the Bay

By Vincent Atos

When I immigrated here from the Philippines never in my wildest dreams had I thought of working on a ferry in San Francisco, California. But I do and often think of Jack London’s book “Sea Wolf.”

“I felt quite amused at the unwarranted choler, and while he stumped indignantly up and down, I fell to dwelling upon the romance of the fog. And romantic it certainly was the fog, like the gray shadow of infinite mystery, brooding over the whirling speck of earth; and men, mere motes of light and sparkle, cursed with an insane relish for work, riding their steeds of wood and steel through the heart of the mystery, groping their way blindly through the Unseen, and clamoring and clanging in confident speech the while their hearts are heavy with incertitude and fear.” Jack London

This is from the first chapter of novel. I did a book report on it over 40 years ago while in English class in the Philippines.

It is a psychological novel about Humphrey Van Weyden, a literary critic and survivor of an ocean collision. Wolf Larsen, the powerful and amoral sea captain rescues him, and he is forced to work as a cabin boy on the Ghost, a seal-hunting schooner. Here he experiences the complexities of life and nature.

It is these complexities of life and nature that I feel I am experiencing right now working on San Francisco Bay.

There is beauty when the fog engulfs the bay but also mixed in is a sense of fear of the unseen when working on a vessel.

With all the new technologies and advanced radars, a collision seldom happens. If ever it happens, a dozen other vessels will be ready to help.

My life is not as exciting and adventurous as Weyden’s, but I find similarities in that we are both stuck working in a vessel by circumstances. Both seeking out new adventures and experiences.

From doing police reports and reporting on goings on in the Philippine capital’s international airport, I find myself in a different space. It has been over 25 years now and I still enjoy life on the water.

I started out as a photojournalist in the Philippines. Beginning in a small city newspaper in Baguio City in the northern portion of the main Island of Luzon. I subsequently found jobs in a couple of major newspapers in the Philippines capital of Manila. Grabbed an opportunity to travel to the US and eventually stayed and married.

My first job in the US was a boxer. A totally different job if you are thinking of sports. The job was for Bill Graham productions and involved putting silk screened concert and commercial t-shirts into boxes. It was mostly South American and Asian workers with white managers.

A friend in San Francisco helped me get a job on the ferries. I started out as a bartender. My new vocation involved riding the ferry for several hours serving snacks and drinks to commuters and tourists. Later I made my way as a deckhand.

I have never had an office job. All the jobs I had involved being outside and traveling.

This job involves boat handling, safety, and cleaning. The crew, like the characters in Jack London’s “Ghost”, consist of a wide sampling of humanity who caught sea fever or are in trapped circumstances.

It is a great union job which attracts a lot of retirees, burned out office workers, artists, rebels, sea lovers and lost souls. One worker coined the group “broken dolls” because of their quirkiness and individualism.

One crew member comes to work every day with a huge camping backpack. Rumor is he started doing it after the last big earthquake when crew members were stuck in boats for weeks because of damaged bridges. They ferried emergency supplies and people.

The mix and match of personalities makes or breaks a crew, each crew of three works together for 2 months or more. Tales of crews clashing is always juicy bay-work gossip. These usually result in firings, suspensions or moving those concerned to a different group.

A lot has in changed since the era of steamers and schooners.

Ferry crews do not need to be “shanghaied” these days. The union has a long list of applicants who are waiting to work the boats.

It’s not mind-numbing work. Your senses are on high alert with the constant movement of the vessel and the ever-changing elements of nature.

As a photographer the job is an inspiration to capture moments of grandeur nature presents, the rolling fog, the play of light and the creatures on the bay. I am constantly searching for these, and every day presents a new image.

Being surrounded by the constant changing elements in a great scenic setting makes the day always interesting. Add to that the different commuters and tourists who ride the ferry.

It’s the best job in the bay.

.

You can see more of Vincent Atos’s images from the bay on Instagram: @vincefoto. If you are looking for a calendar, email Vincent Atos at vincefoto@gmail.com.

…

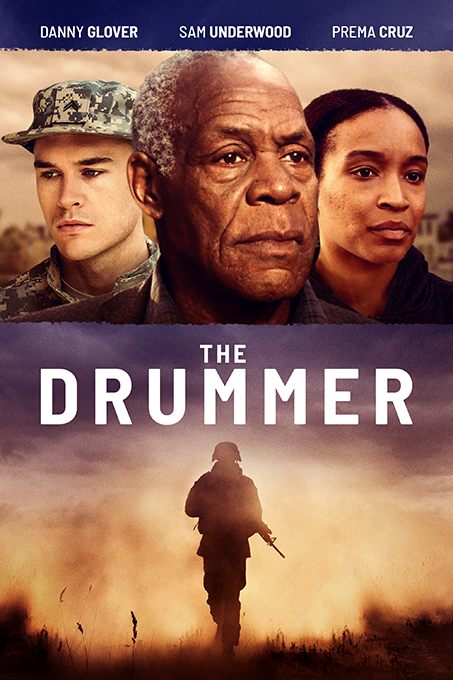

Still Marching to a Different Drummer, The Drummer

By Steve Early and Suzanne Gordon

In recent years, Danny Glover has used his formidable acting chops and Hollywood connections to boost a series of independent films that might otherwise have struggled to find an audience. San Francisco’s most beloved home-grown movie star and political activist appeared in Sorry to Bother You, the widely acclaimed directorial debut of Oakland musician Boots Riley. In 2019, Glover played a key on-screen role in The Last Black Man in San Francisco, the break-through film of director Joe Talbot and actor Jimmy Fails, both San Francisco natives.

Glover is now starring in The Drummer, released Nov. 9, just in time for Veterans Day. It’s a low-budget feature film co-written by Eric Worthman and Jessica Gohlke, who also serve as director and producer respectively. The subject matter is not call center worker exploitation or the gentrification of San Francisco. The Drummer tells the interlinked story of three soldiers who enlisted in the U.S. Army, became combat veterans in Iraq, and then try to avoid being sent back to the same disastrous George Bush-initiated conflict.

All find their way to the Watertown, N.Y. office of Mark Walker, a lawyer, Vietnam veteran, and anti-war activist played by Glover. Walker has joined forces with a younger generation of dissidents in Iraq Veterans Against the War (IVAW) and opened an internet café, near Fort Drum, home of the fabled 10th Mountain Division and other Army units. Called “The Drummer,” the cafe is Walker’s post 9/11 attempt to re-create the atmosphere of GI movement coffee houses located near military bases in the Vietnam era, that welcomed and supported restive draftees like Walker himself.

Unfortunately, as Walker acknowledges, “this is 2008, not 1968.” The all-volunteer army recruits who become his clients lack a mass anti-war movement to provide greater solidarity and political context for their personal decisions to go AWOL and/or seek conscientious objector status. Mike Tanaka, a Japanese-American soldier played by Daniel Isaac, is profusely grateful when Walker helps him navigate a “sanity hearing,” with Army shrinks, which is necessary to secure an honorable discharge. But, with that legal hurdle overcome, Tanaka is on the next bus out of town and unavailable for any press event about his case. “I’m trying to build a soldiers anti-war movement,” Walker complains, after this rebuff. “They need to be part of something bigger than themselves.”

A Different Generation

To avoid another calamitous deployment to Iraq, Cori Gibson, an African-American soldier played by Prema Cruz, has been hiding out with her grandmother, who urges Cori to seek Walker’s help. “The Army gave me a purpose, “she tells her new lawyer. “I signed up to pay for college.” Walker discovers that Gibson, who served as a transportation specialist and gunner on a Humvee, has been raped by her staff sergeant. When she reported this crime to her commanding officer, he told her he had “more important things to worry about in Iraq.” The experience of military sexual trauma leaves her isolated, alone, and nearly paralyzed with depression.

Walker contacts the local Judge Advocate General Corps, and thinks he has arranged Cori’s voluntary surrender to the military, so he can help make her case for a medical discharge, In the meantime, he persuades the anxious young soldier to tell her painful story at an evening press conference at The Drummer, with her grandmother and fellow veterans there for moral support. In an unexpected betrayal, the military police crash the event and haul Cori away in hand-cuffs ahead of schedule, leaving no time for her tell her story.

A Fatal Flashback

The incident is unnerving for a third client, Darian Cooper (Sam Underwood), a white working-class Iraq veteran who is torn between fleeing the military with his wife and baby and returning to the front lines with his squad. Before he is forced to choose, his combat-related PTSD triggers a flashback that proves fatal for him and his family. As a buddy had recently warned him, “the Army eventually eats everybody up.”

These setbacks leave Walker feeling old, ailing, and unable to rally the troops. He counts heads at a peace march and a smaller gathering at a Catholic retreat center, only to find too many of the usual suspects, gray-haired and earnest as always. “Resistance is all I have left,” he confides, while wondering whether he should be working with the environmental movement instead, because “that’s where all the young activists are.” By the end of this dark and moving film, The Drummer is closing up shop. But Walker has reunited with Cori, who boosts his spirits this time and enlists him to become her legal advocate again.

A decade or more after the heyday of the post-9/11active duty resistance, some real-life veterans of that struggle may find The Drummer a bit too gloomy. (For a more upbeat journalistic account of protest activity by soldiers who went AWOL, sought CO status, or even spent time in military prisons to avoid further deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan, see Dahr Jamail’s excellent Will To Resist from Haymarket Books). But any thoughtful feature film about life in the military and afterwards is much welcome these days. The Drummer stands in sharp contrast to the usual Hollywood action film dreck, in which fictional veterans respond to the world of hurt they find themselves in by firing back at foreign and domestic enemies of all types, while on bloody missions of salvation or revenge.

The quieter focus of this film is the lasting physical and psychological impact of military service, under post 9/11 conditions. This is a problem that director Eric Werthman has grappled with, in real life, as a practicing psychotherapist, who has treated veterans. As the brother of a Vietnam veteran, Danny Glover had his own personal reasons for appearing in The Drummer, and serving as its executive producer. As Glover told the press in July, the fact “that there are even more veteran suicides than U.S. soldiers killed in Iraq makes the film more timely than ever.” Now available on major streaming platforms, The Drummer is definitely worth watching on Veterans Day or any other.

.

The Drummer can be viewed via the following platforms. DIGITAL: Apple TV, Amazon, Google Play, Xbox, FandagoNow, Vudu CABLE: iND-EST, Direct TV, AT&T U-Verse, Verizon, Vubiquity, Dish, iND VOD

…

Reflections on the History of the Partito Communista Italiano (PCI)

By Nicola Benvenuti

From Peter Olney, co-editor,

In the fall of 1971 I joined an Italian rugby club in Florence, Italy. One of my smartest and toughest teammates was Nicola Benvenuti. He and I became friends. He went on to become a historian and a member of the Italian Communist Party (PCI). He served on the City Council of Florence and was Council President for a term. The Stansbury Forum is pleased to present his reflections on the PCI and its impact on Italian society.

Upon the 100th anniversary of its founding and the 30th anniversary of its dissolution

The Partito Communista Italiano (PCI) as the largest communist party in Western Europe still arouses interest even if it cannot be said that much remains of that experience. The reasons for this perhaps go beyond the responsibility of the PCI, given that a similar crisis of ideas and political effectiveness today concerns the left as a whole or even the political system that emerged from the postwar period. Here we only want to emphasize some crucial aspects of the PCI’s politics in the period of its greatest success after liberation and until its dissolution in 1991.

The post-war political economic system has certainly changed. Towards the mid-seventies, what has been called the “social democratic compromise” ended. This was a period in which the virtuous cycle of investment in productivity in the context of regulated capitalism and a mixed economy allowed wage increases and fueled the construction of welfare states, modeling in Europe advanced democracies governed by social democratic parties. It was replaced by a liberalism which, cloaked in the promises of economic growth through deregulation, or the minimization of state intervention in the economy, favored social recomposition by reducing the power of the working class, and weakened workers’ organizations rendering left-wing politics less attractive.

The politics of the PCI has roots in the reflections of Antonio Gramsci (Party Secretary until his arrest in 1926) on the causes of the defeat of the labor movement and the advent of fascism, even if his theoretical influence was minimal until Togliatti published the “Prison Notebooks” after WW II. After Togliatti’s return to Italy in 1943, he elaborated a political program centered on the project of a “new party”, a mass party (not a class party in the Leninist sense), which operates in the context of parliamentary democracy, and builds broader political alliances than the United Front with the socialists, and indeed explicitly turns to the DC, a party of Italian Catholics, to carry out “structural reforms”. The democratic parliamentary choice was mandatory in the context of the anti-Nazi alliance throughout Europe and took the form of the participation of the communist parties in popular front governments not only in Italy. The PCI was therefore part of the Italian government and contributed to the Constituent Assembly which produced the Republican Constitution, until the Party’s exclusion after the start of the Cold War. In the Eastern European countries occupied by Soviet troops popular front governments were replaced by the authoritarian centralist model of the USSR.

After the revelation of the crimes of Stalinism at the XX Congress of the CPSU (1956), Togliatti (who never agreed with Khrushchev’s mode of deStalinization) took the opportunity to claim the end of the role of the USSR and PCUS(Partito Communista della Unione Sovietica – Soviet Communist Party) as the “State and the leading Party” of the communist movement. He declared the autonomy of the PCI which supported an “Italian way” to socialism. Following the riots against Soviet domination of Poland and the invasion of Hungary by Soviet troops and the divisions this caused in the PCI, Togliatti continued to focus on the capacity for self-reform of the communist system and the importance of communist internationalism. He accentuated the hierarchical and centralized structure of the PCI, with a clear limit on internal confrontations: thus, delaying the analysis of the nature and contradictions of socialism and eliminating an essential node for the construction of a revolutionary politics in the West. However, even shortly before his death, by re-proposing the principle of unity in diversity in reference to the clash between the USSR and China in international communism, Togliatti kept the democratic political project open, reminding Khrushchev in the Yalta memorial[1] that the fundamental aspiration of communists is “The maximization of freedom”: 1917 remains an “epochal” historical fact, a turning point in history, but – in fact – a historical fact.

Meanwhile, the Italian economic boom of the 1950s, although intrinsically fragile because it was still largely based on low wages and the pressure of unemployment, had an extraordinary impact on the social composition and customs of the country. Industry and services became the main forms of occupation and there was a large internal migratory flow from largely agricultural southern Italy to the industrial north. An attitude that situated the trade union battle mainly in the defense of the workplace was replaced by dynamic bargaining over salary in the context of growing employment and technological innovation. This gave rise to a new profile of the worker, which Tronti called the “mass worker”[2].The centrality of the workers’ struggle emerged as an engine of social change, counter to the vision that the trade union struggle was subordinate to the political project (the transmission belt theory)[3]. The group around the “heretical” magazine Quaderni Rossi, (Panzieri, Tronti), like the trade unionists Trentin and Garavini (PCI)5 or Foa (PSI)[4], underlined the potential of worker’s struggle to confront the new mode of capitalist accumulation which in turn confronts the problem of power in the factory and in society.

The contrast of the modernity and backwardness of Italian capitalism[5] and the effects of the workers ‘struggles, opened up a polemic on the left between an interpretation with spontaneist and anarcho-syndicalist ideas based on workers’ subjectivity (ideas that in the 70s fed the cultures to the left of the PCI ), and the position of many in the PCI who, worried about fueling sectoral corporatism, emphasized the unifying role of the general societal interest achieved by a policy of “structural reforms”.[6]

With the crisis of centrist governments and the electoral decline of the Christian Democrats (DC), the DC Secretary Aldo Moro had opened the door to a center-left politic, that is to the participation of the socialists (PSI) in the government. The socialists, now operating far from any “frontist” hypothesis, had defined a political project based on the intervention of the state as a market regulator through the central role of public industry and economic planning policy. Soon the right of the DC showed that it was able to block the reformist push of the PSI, highlighting for the left the need to increase the pressure. In October 1964, Giorgio Amendola published in “Rinascita”[7] an article with a significant title: “The time has come to reshuffle the cards”, in which he judged both the social democratic and the communist models to have historically failed. He invited the PCI to make a clear criticism of Soviet communism and proposed the reunification of the left parties in Italy (PSI, PSDI, PCI). At the time the article was considered a “provocation” typical of the character of Amendola, and dropped, but in fact it went to the root of the political problems that the PCI and the left would have to face in the years to come.

When in the second half of the 1960s the German Social Democratic party (SPD) launched Ostpolitik, the Italian communists undertook to support it, playing a mediating role with the communist bloc. In the East, détente and the intensification of commercial and cultural relations between the countries of the two blocs strengthened the currents of reform, clashing with the difficulties of the Eastern economic system in sustaining mass consumption. When in Czechoslovakia, Dubcek’s “spring” legitimized forms of the private market, the USSR invaded the country (1968) and stopped the experiment. The repression of “Prague Spring”, a self-reform project that had raised great hopes, provoked the open dissent of many Communist Parties in Western countries and above all of the Italian party, expressed with particular force at the Moscow Conference in June 1969 by Enrico Berlinguer, deputy secretary of the PCI. The dissent, however, was not taken to its extreme consequences. In 1969, after the 11th Congress which saw the moderate current of Amendola prevail over the left-wing of Ingrao, leftists gathered around the newly founded review “Il Manifesto”, were expelled from the PCI. Adherents of Il Manifesto considered the PCI policy towards the Soviet Union too timid. They also differed on the issue of the development model of Italian capitalism and the interpretation of the workers’ struggles of the 1960s.

Taking into account the social and cultural changes in the country of an anti-bureaucratic and libertarian nature, the PCI of Berlinguer, Secretary since 1973, was able to integrate the communist project with an opening to the student movement of ’68 and an acceptance of civil reforms, such as the right to divorce and abortion. Furthermore, Berlinguer altered the condemnation of the European Economic Community as the political equivalent of NATO, whose defensive role he would accept, expressing the need to overcome the bipolar division of the world.

The relationship established with the German Social Democrat Willy Brandt in favor of detente was followed by consultations and exchanges of information, mostly informal and unofficial, on issues of domestic and international politics. The PCI played a bridging role with the communist world, but soon the contact points with social democracy were enriched by a renewed commitment of the Socialist International, and in partcular of the German and Swedish, on the issues of international collaboration between the developed and underdeveloped countries. The origins of the austerity policy that characterized Berlinguer’s approach in subsequent years can be found in the need to review the terms of trade between developed and underdeveloped countries. The PCI’s international politics were above all directed against American imperialsm and support of the struggle for the liberation of Vietnam was an essential component of communist ideology. With the defeat of the Americans in Vietnam (1975), the end of the colonel’s dictatorship in Greece (1974) and the end of Franco’s fascist Spain (1975) it seemed that a fresh wind was blowing.

This took shape as a political direction, later identified as Eurocommunism, which involved the PCI, the French and Spanish, and partly English, Communist parties. Due to disagreements between socialists and communists in France and the political disappearance of the Partido Communista de Espana (PCE) in 1977 with the end of Franco’s dictatorship, that political project remained an aspiration. After the failure of the historical compromise in Italy, and the assassination of Moro, Berlinguer, in 1982 posited Eurocommunism as a “third way” between capitalism and communism.

Togliatti’s strategy had been relaunched by PCI Secretary Berlinguer after the coup d’état in Chile (9/11/73) which put an end to the socialist government of Salvador Allende. Berlinguer concluded that in countries with parliamentary democracy the united left could not come to power through the conquest of 51% of the electoral votes. Rather to prevent violent reactions from the opposing classes and imperialism, as happened in Chile, it was necessary to widen the borders of the progressive front aiming “not at an alternative left but to a democratic alternative “; in Italy, through a” historic compromise “with the Catholic party (DC).

In the midst of the 1977-78 terrorist wave, the PCI had the opportunity to apply the policy of “historic compromise” with the DC. The PCI emerged victorious in the 1975 referendum on divorce and the administrative elections. In the following year’s political elections the Party reached 34.37% of the votes in the Chamber of Deputies. These victories highlighted the fact that the safeguarding of legality and democracy could not take place without or against the PCI. The secretary of the DC, Aldo Moro, was convinced of this, and therefore intended to bring the communists into the government. The PCI therefore became part of the majority, of “national solidarity”, with the DC government and was strongly committed to defending republican democracy against terrorism on the right and left. The kidnapping and assasination of Aldo Moro on March 16, 1978, prompted the DC to end the political alliance and drive the PCI into the opposition. Berlinguer tried to revive the politics of the left-wing alternative, but with little enthusiasm from the PSI[8], because the left-wing alternative would have made the socialists, already reduced to 6% of the electorate, politically irrelevant. The new secretary of the PSI, Craxi, instead aimed to overturn the balance of power in the Italian left and offered political support to the DC for a government without the Communists. The policy of “national solidarity” had failed and not by chance. The American Secretary of State Kissinger was against the participation of the PCI in the government and even the main European governments (including Schmidt’s Social Democratic government in Germany) were negative towards the PCI’s partipation in government.

At the end of the 1970s, the PCI’s situation was problematic. A Second Cold War (installation of missiles in Europe, invasion of Afghanistan by the USSR) had begun. The adoption of Martial Law in Poland, against Solidarnosc, forced the PCI into a new condemnation of Soviet policy which Berlinguer expressed as a failure of the “propulsive thrust of the October revolution” (1981).

However, the PCI was unable to put in place any alternative strategy that would capitalize on the links established with progressive European forces, while the distancing from the politics of the USSR paradoxically weakened the international role of the PCI. Hence the emergence in the 1980s of ecumenical or moralistic tones, embodied in the attack on working class power:

- Firings at Fiat

- The cutting of the wage escalator – desired by the Craxi government, but with the consent of the trade unions

- The politics of austerity, a central theme in the debate on the new world order for rebalancing the economic relations between developed countries and developing countries

- The spread of the state’s tenure by the parties: the exclusion of the PCI, as the largest opposition force and thus the absence of an alternative to the DC, gave the DC and its allies a monopoly in the management of the state and resulted in corruption and inefficiency in public administration.

However the unresolved problems of the ideology of the PCI were not solved:

- The meaning of Soviet communism and the relationship with European socialism:

- The claim of “communist diversity”(Stalin’s term) that characterized the self awareness of the militants, hindered the PCI from clearly occupying the space of Social Democracy (Craxi did his part vetoing the entry of the PCI into the European Socialist Party (PSE), the parliamnetary aggregation of the socialist parties in the European Parliament.

Therefore the PCI was condemned to growing political inconsistency resulting in loss of links also with their traditional social base, although that loss was hidden by the national recognition of the political and moral integrity of the party’s leadership.

Upon the death of Berlinguer on November 6, 1984 there was a great emotional outpouring in the country, but the weakness of PCI politics manifested itself openly. In 1989 after the fall of the Berlin Wall, the new secretary of the PCI, Achille Occhetto, announced that he wanted to take a new political direction, one that foreshadowed the end of the Communist Party and the birth of a new Italian left party (Bolognina turn)[9] At the XX Party Congress, in February 1991, the PCI was dissolved and the Democratic Party of the Left (PDS) was formed, but with no clear poltical direction.

It is clear that the PCI’s standing in the international scene resided, for better or for worse, precisely in the relationship with the USSR and the communist movement, and this explains a lot of the hesitation of the party leadership to sever relations with the Soviet Union (Beyond the extreme concern about the destabilizing effects such a break could have had on the party base). The fact is that the PCI, as a major Communist Party of the West and a critical conscience of communism, enjoyed a wide range of maneuverability albeit full of stresses and expectations. When the Party could no longer capitalize on the political credibility conferred on it by the Soviet leadership (unfortunately a little studied theme), the PCI lost a lot of its international credibility, even with third-world countries. What direction could an opposition party offer from a country that played a secondary role in international events?

All things considered the dissolution of the PCI was a great loss. The PCI was certainly characterized by the vitality of an open mass party that operated as a collective intellectual. It situated itself as a political center for sharing political line debated among political leaders, trade unionists, workers, technicians, researchers and university professors and a myriad of territorial and professional organizations. And at the same time the Party was capable of advancing a pedagogy of civil responsibility that activated the participation of the masses in political life. This is the model that is missing today on the Italian scene.

…

[1] Yalta Memorial was written by Togliatti a few days before his unexpected death in Yalta, in Crimea (August 1964) and was written in preparation for a meeting with Khrushchev

[2] Tronti along with Renato Panzieri founded the “workerist” Marxist journal, Quaderni Rossi (Red Notebooks) and wrote an important book, Workers and Capital

[3] The idea that the trade unions led by Party member would dutifully transmit the political project of the Party to the trade union members

5 Bruno Trentin was general Secretary of the largest Italian trade union federation the CGIL and a member of the PCI until its dissolution in 1991. Sergio Garavani was a leader of the metalworkers federation FIOM and also a prominent PCI leader.

[4] Vittorio Foa was a prominent leader of the CGIL labor federation and the Italian Socialist Party.

[5] Expressed in the contrast between the development of the industrial north and the backwardness of the agricultural south to which was added in the context of the economic boom the persistence of backward and authoritarian labor relations, which accentuated differences in productive sectors and geographical areas.

[6] Structural reforms were intended as reforms able to effectively reunite the interests off the popular masses with objectives of social progress, Structural was the term used to distinguish such reforms from social democratic reformism.

[7] Theoretical magazine of PCI

[8] Partito Socialista Italiano – The Italian Community Party was formed in 1921 by members of the Second International PSI

[9] On November 12, 1989 Achille Occhetto then General Secretary of the PCI announced at Bolognina (a section of Bologna) his intention to lead a change in the name and direction of the PCI

Shelter From the Storm

By Brian Edwards

Ooh, a storm is threatening

My very life today

If I don’t get some shelter

Oh yeah, I’m gonna fade away

“Gimme Shelter” -Jagger/Richards

Last weekend, San Francisco endured record rainfall during its first major rainstorm of the year, receiving over 4 inches of rain within the roughly 48 hours that it lasted. The storm had been forecast for over a week and was all over television, internet, and radio. For most locals, news of upcoming rain was good news, as the Bay Area was in the middle of a lengthy statewide drought. The raging wildfires that razed through entire bone-dry North Bay communities in recent years are still fresh in many people’s memories, and a prolonged drought would likely have multiple negative impacts on a state economy already hit hard by the extended pandemic. We needed the water, and the sooner, the better. The rain was forecast to begin on Saturday and subside by Tuesday, and by Friday afternoon before the storm, most San Franciscans had resigned themselves to prepare for a weekend spent indoors with little fuss or fanfare. Slow cooker recipes were downloaded during lunch breaks, Instacart grocery orders were placed, and Netflix queues were added to.

But the city’s homeless people and advocates, along with staff at the Department of Emergency Management (DEM), the Department of Public Health (DPH) and the Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing (HSH), were getting nervous. The storm was expected to bring high winds, flooding and near-freezing temperatures to the Bay Area, a combination which can be deadly for anyone caught outside and is always absolutely miserable. The first rains were projected to start falling around noon on Saturday, with the heaviest rains and winds beginning on Sunday morning and lasting through Tuesday morning. Advocates and service providers tend to estimate San Francisco’s unhoused population to be 10,000 or more, though the Point-In-Time (PIT) count offers a more conservative estimate of 8,000. Many of these folks lack access to TV or radio. Internet-enabled mobile phones tend to get lost or stolen easily on the street. Mother Nature was about to blow some serious chaos at SF’s most vulnerable residents, and many of them might not be aware she was coming. Even those who did had little chance of getting out of her way and members of the Homeless Outreach Team (SFHOT) along with the City’s service providers had already spent days and nights focusing efforts on spreading warnings of the upcoming storm to folks in encampments and doorways all across the City, along with distributing emergency food, water, ponchos, blankets and socks. With the storm less than 24 hours away, City leaders had elected to try to open the first inclement weather shelter expansion in over a year that weekend but were still scrambling to nail down staffing and logistics. It was almost 9 p.m. on Friday by the time HSH was able to announce the emergency expansion of shelter to their email list, long after most of the City’s service providers and outreach workers had gone home for the weekend.

Shelter from the storm was available, along with hot meals and opportunities to link up with services, but how the hell were people going to find out? The City hadn’t had an inclement weather expansion for two years, and no one outdoors was expecting one to come. HSH’s Twitter feed doesn’t exactly trend, and online efforts to reach folks only go so far. Many of those who weren’t lucky enough to be able to ride the storm out in one of the City’s FEMA-funded hotel rooms, which had been doled out months before, had learned to expect little in terms of meaningful relief from the City over the last year and a half, and few were going to spend much time looking for any. If the City wanted people to know help was available, the City was going to have to bring that message to them in person. They wouldn’t be easy to reach, years of

enforcement against public encampments had taught them to spread and scatter in order to escape the City’s police cruisers and crusher trucks. Many had hunkered down in out-of-the-way places in advance of the storm. The City would have to find them first. SFHOT had the advantage of already knowing where many folks had hidden away, but there were only six out-reachers scheduled to work on Saturday, and only four on Sunday. The team members also had survival gear to distribute as well as word to spread, and both tasks seemed daunting.

SFHOT weren’t alone. SF’s advocates and service providers are long used to filling in the gaps and finding ways to collaborate and complement the efforts of a frustratingly under-resourced City. Many of us also have blurred work-life boundaries and social lives that barely exist, so weekends mean little. By Saturday morning, Signal groups and inboxes began filling up across the City with messages notifying friends, neighbors and co-workers of the additional resources available. Some nonprofits also had staff scheduled to work over the weekend and began to join the efforts. The rains began on time Saturday afternoon, though, and by the time SFHOT ended its shift on Saturday evening and went home, thousands of unhoused San Franciscans hadn’t been reached, and fewer than a dozen people had elected to take advantage of a mat indoors away from the rain.

It didn’t look good.

“I can’t wait until I can shout down whatever City employee says in a Zoom that the empty rain shelters during this storm prove that homeless folks don’t want help or resources,” I texted a friend on Saturday night. San Francisco has a history of failed attempts at messaging and communication with its unhoused residents, and it looked like this storm was going to add to that pile.

But Sunday was a new day. Case managers and hospital social workers who had been forwarded one of Saturday’s emails or text messages began calling and advocating for clients and patients. Unhoused residents and volunteers from Coalition on Homelessness workgroups and mutual aid organizations joined staff from local nonprofits, including Glide, Mother Brown’s and Urban Alchemy in the push to get the word out. The rain and the winds kicked up harder, but SFHOT’s skeleton crew of outreach workers battled downed trees and flooded streets throughout the afternoon to connect with more people, and at 5:31 p.m., I got a text message from the SFHOT manager: “Moscone Full.” I was going to have to wait for a different opportunity to shout at a City employee on Zoom.

In the end, 100 San Franciscans were able to get relief from the wind and rain at an Urban Alchemy-staffed emergency pop-up shelter located inside the Moscone Center, plus 40 more at ECS’s Sanctuary shelter in SoMa. Filling a pop-up shelter to capacity is difficult even outside of a pandemic and with triple the amount of time and resources available. Last weekend, with a fairly sizable assist from the community, SFHOT knocked it out of the ballpark, and Mayor London Breed and HSH Director Shirleen McFadden owe them a round of drinks.

For thousands more last weekend was just like any other during the last 18 months, and they were screwed — left outside to freeze and soak. Dozens of beds at the City’s regular congregate shelter sites were empty on each night of the storm and weren’t available to be filled. And unless the City makes a major change to the way they allot and fill shelter beds, anyone living outside on whatever day you’re reading this has a tiny fraction of the chance of getting a shelter bed that they would have had during any night of the storm.

With multiple emergency shelter sites closing down at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the rest reducing capacity by 50% or more, San Francisco’s shelter-in-place order almost immediately translated to “stranded in place” for those forced to sleep outdoors. Homelessness is never easy, but it was especially challenging for anyone experiencing it in 2020. Service providers reduced or eliminated hours, and drop-in facilities closed. Mobile pop-up sites and outreach operations at those providers also halted, sometimes for months. Residential and commercial buildings instituted strict no-visitor policies. San Franciscans were told to limit physical contact and exposure to a handful of people in their social “bubble.” For the better part of 2020, homelessness instantly became a 24/7 lockout for thousands of San Francisco residents, with no opportunity to escape indoors for even a moment of relief. Last December, it was not at all uncommon to run into folks who hadn’t been able to shower for nine months and who had given up trying to find places to charge their phones.

Homeless shelters aren’t perfect anywhere and aren’t for everyone. They never have been, but they’re still an integral part of any community’s efforts in tackling homelessness and reducing some of the harm of living unhoused. Before the pandemic, San Francisco’s single adult shelter system had the capacity to offer over 2,000 San Franciscans the safety of being indoors on any given night, or a little over 20% of its unhoused residents, according to the 2019 PIT count. COVID-19’s effect on the system, along with the safety and respite it offered was almost immediate and has been devastating. New intakes at sites were halted within days of the March 17, 2021, SIP order — if you weren’t already in the system, you weren’t getting in, and subsequent outbreaks at multiple sites soon showed that “in” didn’t necessarily mean “safe.” With intakes halted, the City quietly eliminated the single adult shelter waitlist and moved the shelter sites onto a new occupancy management database. Unhoused residents could no longer call 311, drop into Glide, or check in with a County Adult Assistance Program worker for a shelter bed. In fact, all self-referral pathways to a spot at one of the City’s alternative emergency shelter sites were gone, and nearly a year and a half later, the City shows little sign of any intent to restore a low-barrier self-directed pathway from the streets into a traditional or Navigation Center shelter bed. The system that could once accommodate 2,000 is now limited to 962 as of this writing.

For most of the first year of the pandemic, shutting off congregate shelters to self-referral made sense. Outbreaks at shelter sites across the country and in Europe showed that congregate settings were not safe places to be. Through the Healthy Streets Operation Center (HSOC), the City pivoted to mainly offering two new forms of emergency shelter for a while — hotel rooms and Safe Sleep sites, where individuals or pairs of people live in separate tents. Both were wildly popular among homeless residents, with rooms in San Francisco’s SIP hotels having a 97% acceptance rate among those who were offered one, according to a presentation made by former HSOC director Jeff Kositsky. But new intakes to the SIP hotels ended earlier this year, and several sites have already closed down, with about 1,400 people remaining inside, according to testimony shared at the Board of Supervisors Budget and Finance Committee meeting on October 27. More sites are scheduled to close later this year, and advocates and providers are currently locked in a battle to get the City to extend and expand the program beyond its September 2022 sunset date. Safe Sleep sites fill up fast, and once filled, reservations at all City sites are now open-ended instead of limited to a maximum of 90 days. That means more security for the folks placed inside of it, but also leads to less turnover, and openings at Safe Sleep sites are extremely rare. These openings are managed directly through HSOC and offered almost exclusively to folks facing immediate displacement during an encampment sweep.

While the lifting of the statewide and local SIP orders earlier this year have allowed providers and businesses to reopen and offer unhoused folks more opportunities to seek relief indoors during the day, SF’s push to get folks off the streets into hotel rooms and sanctioned encampments largely ended after the first 3,000 were placed. Current data on how many people remain outdoors doesn’t exist — the 2021 PIT count was cancelled due to COVID safety concerns, and the City’s own data has been focused on tents instead of individuals for years. But even conservative estimates project a significant rise in homelessness nationwide after the first year of the pandemic. As COVID-related national and local eviction moratoriums expire along with unemployment and other financial assistance, the number of people forced out onto San Francisco streets is sure to rise before it falls, and thousands of San Franciscans will have no other option than sleeping outside at night in tent encampments, parks, sidewalks and doorways.

That’s not to say that there isn’t space for more folks to seek relief from the streets. San Francisco’s congregate shelter system hasn’t had a major outbreak since last year, and by my estimate has had a 20% vacancy rate since July. But spots at those shelters are still offered a handful at a time, with SF General Hospital often getting the majority of any day’s available placements for unhoused residents who are being discharged. HSOC has priority for much of what’s left over, and, as with Safe Sleep placements, offers their allotment exclusively to those facing displacement during encampment resolutions. Anything left over — frequently fewer than five beds per day — gets given out by SFHOT, who have multiple other priorities to juggle, including locating folks outside of the SIP hotel system who are eligible to receive housing and responding to calls about people in distress. One might think that a City with more than 10,000 unhoused residents would have an outreach force of hundreds, but SFHOT numbers just about 60. The City asks a lot of them in the best of times, but the expectations and responsibilities for SFHOT during COVID can be overwhelming and exhausting to even watch. The 311 waitlist remains offline, and workers at drop-ins and other community-based nonprofits are still without direct access to reservations at any of the City’s shelter sites. Unhoused San Franciscans seeking shelter or those advocating for them can leave a voicemail with SFHOT, and if they’re lucky enough — and early enough —, they can connect with an outreach worker to land one of the few spots that HSOC makes available on any given day. SFHOT’s commitment to following up on calls they receive is genuine, and other advocates and I have worked with them successfully dozens of times this year to get folks off the streets into alternative shelter. But many folks have been on the streets for years, and SFHOT hasn’t always been so diligent. Those folks often have little faith in follow-through, and most unhoused people aren’t even aware that there is a voicemail to call. Also, there’s no guarantee that there will be a spot. Often, the surest way for an unhoused person to get into one of the City’s vacant shelter beds is to be in an encampment HSOC targets for displacement. SF is burning out one of its best key resources, while shutting out its community partners and letting 20 percent of its shelter beds go unused each night.

That’s nuts, and it’s also a step backwards towards a system that worked for no one. Before a phone system to reserve beds went live in 2014, people could spend hours each day lining up outside of shelters or waiting in drop-ins hoping to secure that night’s shelter. Code Tenderloin founder and Local Homeless Coordinating Board co-chair Del Seymour told me that when he was homeless, he would often have to waste half a day in one spot waiting, just to see if there was a spot available for him that evening. Many evenings there wasn’t. “It was bullsh*t,” he said.

That system changed in 2012 when former SF homeless czar Bevan Dufty convened the Shelter Access Workgroup, which included providers and unhoused residents from across the city. “With extensive input from unhoused shelter users, lines and waiting rooms were eliminated, and the system changed to the 311 call-in system that made it simple to request a bed that fit your needs,” said Coalition on Homelessness Executive Director Jennifer Friedenbach. “Just a few years later, there is not even a line to wait in, let alone a toll-free number. There’s no way to get in beyond the sheer luck of being in the right place at the right time when a City outreach worker happens to both run into you and have a bed to offer. Unhoused people absolutely must have a way to request shelter themselves.”

The good news is the City already has that way — it’s simple, has worked before and can work again — which brings me back to the storm at the beginning of this article. During the storm, folks were able to walk up to the sites at Moscone and Sanctuary without a reservation, and as long as there was space available, they got in. That’s key. Homeless folks should have as much agency and authority over the resources they accept as the city employees and nonprofit workers who offer them. When you give folks the ability to get into a bed without having SFHOT handle the reservation, you allow folks to make their own decisions at their own speed and on their own terms, and that leads to better outcomes for everyone. Beds fill up fast. The City already has some of the best nonprofit, public health and outreach workers in the world — seriously, they fucking rock. And it has shelter beds. By unburdening SFHOT from being the lone gatekeeper and including community and provider nonprofits in the shelter allocation and distribution process, everyone involved can better use their own resources to complement each other’s efforts, and beds end up being occupied by folks who want them, instead of folks being pressured into them under the shadow of an SF Public Works crusher truck.

Most things aren’t this simple, but this is. I doubt that Mayor Breed or Director McFadden will read this, but just in case:

Restore the single adult shelter waitlist. Let folks call 311 or walk back into Glide or Mother Brown’s to get on it, and start filling those vacant beds, and give ‘em shelter like The Rolling Stones advise. Let service providers and SFHOT each do the things that they’re best at, so they can collaborate and function together as a true community/government partnership. Bring unhoused residents back to the center of the policies and procedures that impact and service them and restore a bit of the sanity we all lost during the pandemic back to the system we live, work or advocate in.

And buy those outreach workers from last weekend a beer.

If you don’t listen to me, listen to Hospitality House director Joe Wilson: “There’s no excuse for people being without shelter in San Francisco. None. We should make it easier — not harder — for people to come inside from the cold. We can do better, and we must, in the City of St. Francis.”

Cheers, Joe.

.

Gimme Shelter originally appeared in Street Sheet, A Publication of the Coalition on Homelessness on 2 November 2021

Personal note from Robert Gumpert, co-editor of the Stansbury Forum:

Brian Edwards was an outreach volunteer and member of the Human Rights working group with the Coalition on Homelessness here in San Francisco. It was on the street that I meet him about 4 or 5 years ago. Committed, resourceful and deeply human, Brian died in the early hours of 4 November 2021, just two days after writing this piece. He will be missed by all those he chanced to meet.

…

A Candidate For Mixtecos in the Republican Heartland

By David Bacon

As national attention focuses on the Virginia gubernatorial election on November 2 or the New York City runoff for Mayor, David Bacon takes us to Madera County in the San Joaquin Valley of California for a report on an important and path breaking effort to elect Elsa Mejia to the City Council of Madera, the county seat. Mejia is the child of Mexican immigrants from the state of Oaxaca in Mexico. They are indigenous peoples mostly farmworkers who speak Mixteco and make up a sizable portion of Madera’s population.

As Bacon points out, Kevin McCarthy, the Republican minority leader in the House of Representatives, would be toast if immigrant farmworkers could vote in the Valley. Tuesday’s election is worth watching in Madera. If Mejia succeeds, it will be one small step towards the empowerment of the majority working class communities of the Valley. The Latino immigrant upsurge in labor and politics in Los Angles had a transformative impact in the 1990’s on the whole state of California. Might Madera be the beginning of a new politics in the traditionally “red” zones of the Central Valley?

Peter Olney, co-editor of the Stansbury Forum

.

Madera County has been a stronghold for decades for the Republican Party in California’s San Joaquin Valley. Billboards this fall lined rural highways, urging the recall of Governor Newsom, pasted over peeling Trump/Pence posters. If Newsom’s fate had rested on Madera County he would no longer be governor – sixty percent of county voters went against him. Fifty six percent went for Trump in 2020, slightly more than 2016. In fact, the last Democratic Presidential candidate to win the county (barely) was Jimmy Carter in 1976.

But in the city of Madera, the county seat, changing demographics are producing political challenges to a conservative order. That seemingly solid majority does not reflect the demographic reality of the county’s 156,000 residents. Almost 60% of county residents list their origin as Hispanic. African Americans, Native Americans and Asian Americans make up another 10%.

That challenge is colorful and young in the city’s District 5, which combines a dilapidated downtown with a large eastside barrio. Here California’s growing community of indigenous Mexican migrants has put forward its first candidate – Elsa Mejia, who is running for an open seat on the city council.

Mejia was born in nearby Fresno, to parents who’d come to the Valley from the Oaxacan town of Santa Maria Tindu. A decade ago, the Leadership Council of Santa Maria Tindu, an organization of town residents now living in the U.S, carried out its own community census. They wanted answers because the government does no count indigenous migrants, even in the Census. The Council found that migrants from just this one Mixtec hometown, living in Madera, already numbered 2,500. Together with migrants from other Oaxacan communities, Mixtec-speaking people now are a sizeable part of Madera’s people.

California communities of indigenous migrants maintain their ties with their Mexican towns of origin. Growing up, Mejia would return with those family members who could cross the border to visit her grandfather in Tindu. He would try to teach her Mixteco. “But we didn’t stay long enough, so I just learned a few words,” she laughs. Later she lived in Oaxaca for a year, working for Rufino Dominguez, a revered migrant leader in California who went back to Oaxaca to head its state Institute for Attention to Migrants. Mejia later worked for a decade as a reporter for the Madera Tribune, and then edited Fresno’s progressive monthly, the Community Alliance. Today she works in the communications staff of Service Employees Local 521, the Valley’s union for many public workers.

“It’s very important for people to have access to public services in their own language,”

Mejia’s laugh belies the many things her parents, and Mixteco parents like them, did over the years to make sure their children know and enjoy Mixtec culture. They formed organizations to carry that torch, from dance groups to language classes.

Every year the Binational Fronte of Indigenous Organizations (Frente Indigena de Organizationes Binacionales – FIOB) mounts a dazzling festival showcasing the dances of Oaxacan towns, called the Guelaguetza. Its Fresno festival is just one of several. California’s indigenous Oaxacan population is so large there are more Guelaguetzas organized here than in Oaxaca. In Madera itself FIOB has organized a yearly basketball tournament, the Copa de Juarez, on the birthday of Benito Juarez, Mexico’s first indigenous president. It organized protests against the celebration of Christopher Columbus’ arrival in the Americas, accusing colonizers of trying to destroy indigenous culture and people.

Culture is a principal basis of organization in Mixteco communities, a key understanding for winning an election in Madera District 5. Even if she has problems with the language, as many second-generation immigrants often do, Mejia understands its importance in mobilizing her community. “It’s very important for people to have access to public services in their own language,” she explains. “We still don’t have equal access, even in Spanish. You can’t take a driving test in Mixteco. Everybody should have access in the languages they speak.”

FIOB fought over many years for language rights in the Valley. It won interpretation in Mixteco and other indigenous languages in California courts before that right was recognized in Mexico. But Fidelina Espinoza, FIOB’s state coordinator who staffs its Madera office, says she supports Mejia because language is still a huge problem tied to the lack of city services in general. “When our parents go to school for a conference with teachers, there are no interpreters, and sometimes even no conference,” she charges. “We have no translation to help us access what we need, and the city doesn’t support cultural programs or even community gardens for our young people.”

“The city has abandoned downtown. Those little stores and restaurants were hit hard by COVID, but where was the help?”

Downtown Madera could use a lot of community gardens. The main street, Yosemite Avenue, is lined with small businesses, mostly with Spanish-language signs, that are clearly having a hard time. One star attraction is Sabores de Oaxaca (Oaxacan Flavors) where a stream of Mixteco-speaking customers find a small cool restaurant. Many come inside still in sweat-stained clothes from a day in the fields, in 115-degree heat.

Nevertheless, other businesses on Yosemite Avenue could clearly use city support. Across the freeway chain stores and malls get a lot more attention. Downtown homes are mostly modest rentals, many in need of help as well.

“The city has abandoned downtown,” Mejia charges. “Those little stores and restaurants were hit hard by COVID, but where was the help? People in District 5 have the lowest incomes in Madera. A lot of people have no homes and there’s no city program to build housing. The subsidies in the Federal bills for renters never got here.”

“Things are going to change if Elsa is elected,” promises Antonio Cortes, Central Valley Director for the United Farm Workers. Cortes also comes from Tindu, and today works in the union’s Madera office. “Oaxacans are very numerous and important here,” he says. “We’re always struggling with the city for resources, and we deserve representation. She comes from a farmworker family, and has that commitment.”

Out of an economically active population of 85,000, about 23,000 Madera County residents work in the fields, according to demographer Rick Mines. His studies show that the median income for a farmworker is between $10,000 and $12,499 while for a family, the median is between $12,500 and $15,000.

In the pandemic, poverty translates into illness and death. Madera County has had over 22,000 COVID-19 cases (14% of the population) and 266 deaths. Only half of its residents are vaccinated. Reporting Area C, which includes downtown and the eastside barrio, has the most cases, almost a third. By comparison, in Silicon Valley’s Santa Clara County, while it has more cases, only 7% of residents got the virus, and over three quarters are vaccinated. Everyday activists in FIOB go out to the fields to sign people up for shots. UFW organizers visit members in the almond orchards, bringing masks, sanitizer and other protective equipment.

Mejia’s chances of winning come from her connection to these campaigns and organizations, working on concrete community problems. She’s running for an open seat, and her opponent is another Latina, Matilda Villafan. But in challenging the economic priorities of the San Joaquin Valley, Mejia doesn’t have an easy path to election. For instance, she believes that “farmworkers who work during the pandemic should be paid better since they’re risking their lives. And not just them, but their families as well. This should be part of treating them with dignity as workers.” The growers who put up those Trump signs can’t be happy about that.

Elsa Mejia represents the new generation of the children of these families, born here, and therefore citizens.

She thinks there are about 2000 eligible voters in her district, but there’s no precise number for those who come from indigenous families. It is a complicated question for several reasons. In the huge migration of people out of Oaxaca, the first wave of migrants to reach California arrived in the mid-1980s, and the arrival of people has continued ever since. Because the last immigration amnesty in 1986 had a cutoff date of January 1,1982, most of these migrants have been undocumented. For them, citizenship, the ability to register to vote, and the political rights that come with that, are out of reach.