ISRAEL, MY ISRAEL? A POEM-ESSAY

By Gene Bruskin

ISRAEL, MY ISRAEL?

A POEM-ESSAY

ISRAEL

Will never be the same

Its viciousness untamed

Universally shamed

Appropriately blamed

Zionist mythology unframed

And forever stained

People’s souls chained

Hitler’s atrocities

Excusing current monstrosities

At an unimaginable velocity

Never again

Comes again

And again, and again

The victims of the past

Inundated by the echoing pageantry of the government’s traumatizing machine

Become the victimizers of the present

Creating new victims

Whose survivors will turn against them

And create more victims

This is certain among much uncertainty

Young soldiers as monsters

Instagraming their crimes

To a cheering population

Kill them all

Cry the people

Free our precious sons

BACK AT THE RANCH

The tail wags the dog

US leaders smile sternly

Taciturnly

Change the subject

Muttering

Mealy-mouthed

Peace now

Bombs on the way

Rules based disorder

Respect no borders

As our 250th year nears

All the world can see

Our deceitful moral pose

The Empire has no clothes

BACK AT THE RANCH

Our president is of half a mind

To only use half a mind

His bones soaked by 50 years of Zionism

Willing his legacy to the devil

Endangering a nation, disheveled

Ignoring the uproar

From shore to shore

Risking fascism at home

Begging his insidious nemesis abroad

To throw him a bone

Instead, he is humiliated from afar

By this murderer with a Jewish star

Barely exposed beneath his bloody cloak

As he mouths empty shibboleths of

Self-defense, a moral army

While our President humbly bows

Till death do him part

THE SPOILS OF WAR AND EMPIRE

ISRAEL MY ISRAEL

A nation created to replace another people

Herr Balfour

British Lord

Closing the Arab door

Putting in European types

Even Jews that he abhors

The oil is coming

The oil is coming

Spare no cost

Set the impossible in motion

Then exit self righteously

With the damage done

Never to be undone

But alas, today, the Arabs are tamed

While the region is enflamed

All are willing to play the US game

Even the Saudi’s

In their luxury Audis

With so much money to be made

Their greed precedes them

Israel actually impedes them

With endless expanding wars

And yet it goes on

The Palestinians as the permanent pawn

BACK AT THE RANCH

After more than a century of progress

Against the scourge of home-grown antisemitism

Jews shockingly choose

Netanyahu

Who believes in everything they hate

Except the Jewish state

Whose friends are too ugly to contemplate

Breaking from their historic allies against white supremacy

Stoking the fires of antisemitism once again

Hugging Jew-hating Christian nationalist Zionists

Who are waiting for the Second Coming

To wave goodbye while Jews burn in hell

And they go to heaven

With the Z word tattooed in Henna on their Ak47

But the Jewish light survives

With the idealist youth

Who daily defy

Refusing to lie

Valuing all lives

Upholding our great tradition

Tikkun Olum

They are the keepers of the Faith

With odd initials

JVP

INN

NIMN

My generation celebrates

The future leaders of our Jewish community

Welcome my Jewish comrades

Welcome

…

Hope and Heroes – Stewart Acuff’s Poems from the Frontlines of the Class Struggle

By Peter Olney

For four years Stewart Acuff lived in a small Appalachian village called Shepherdstown in West Virginia above the Potomac. There he wrote a poem a day from 2020 to 2022. Many of these short works are collected together in Love is Solidarity in Action. The poems reflect not only on the natural beauty of the town and the region, but the deep and rich experience of Brother Stewart’s organizing trajectory:

“Yeah I stayed pissed off.

Sitting on a hotel room bed in Center, Texas home of Lightning Hopkins listening to women wonder which would be fired first cause we lost the union election

I drank a couple barrels of bourbon getting over that night and I still get pissed off

when I remember

Seeing and smelling the insides of county jails across South Georgia fighting for

Jobs and a life beyond working like a mule

Getting out and getting drunk

Fighting the Ku Klux Klan in East Texas on a picket line of Black women scared

But overcoming with courage ready to fight every night

And I still get pissed off”

May 12, 2020

The collection is best read at the pace of a poem or two a day, which means the 130 pages, may take a while. But read, pause and reflect on the richness of Acuff’s experience reflected in these short works. He has certainly personally been on the front lines of the class struggle in America and particularly the effort to rebuild a vibrant labor movement by organizing millions of new workers. He is retired now, but I first met him when he was head of the central Labor Council in Fulton County Georgia (Atlanta). He was leading an effort to make sure the 1996 Atlanta Olympics meant justice for workers. He also was a force within the movement to reform the AFL-CIO with the election of John Sweeney as President. In 2001, a few years after the the New Voice movement took over the AFL, Acuff was appointed Organizing Director, and I collaborated with him as Organizing Director of the West Coast Longshore Union. We have been friends ever since.

I also have discovered that Acuff is not alone in the aspiration of writing a poem a day. This appears to be a tradition in the form. Anita Barrows has written a poem a day since the beginning of Israel’s assault on Palestine. And then there is the poem a day website

Acuff’s poems resonate with outrage over man made climate change, racism and the treatment of working people. He also teaches history by referencing one simple historical fact or often-unsung heroes of our movement in each poem. Reverend James Orange is a particular comrade favorite of Stewart’s. He is a man brought up in the civil rights movement who worked later with Stewart for the AFL-CIO. Stewart pays tribute to him often in a manner that suggests that Orange gets too little credit for his role in the civil rights movement and labor.

“A night of six of us in Dekalb County custody won medicines for poor, homeless and weak

Reverend Orange leading our sit in at the commissioner’s office winning safe staffing

There is power only known to those confronting wrong with our own bodies”

February 15, 2021

Acuff’s poems send you running to the Wikipedia search engine to unearth the history of heroes and particularly unknown heroines of the movement:

“Sing this weekend for the unsung

Who sang freedom with their actions

Like Carrie Williams in East Texas

Leading her co-workers to justice

Etra Mae and Mae Nell in small towns like Palestine

All the folks across Georgia standing against plantation thinking.”

September 4, 2021

Acuff has great pride in his two children, Sam and Sidney,s and visiting or communing with them is the subject of many poems.

“Hurricane Ida in the magic city of our culture

And fires where son Sam labors

With thousands of others to save our Earth

From human destruction

We did it

Now time to fix it.”

September 9, 2021

Poetry has never been my thing and certainly the free form that Acuff writes in is an acquired taste. But that taste I have indeed acquired out of respect for a comrade brother. I promise to dig deeper into the art form, maybe even read a poem a day! This collection is easy to order and is a great bedtime companion. Acuff reflects on the stakes in the election of 2020 in a poem that resonates again in 2024

“Folks fight for justice and democracy

Folks fight for Hitlerism and white supremacy

Everything good about America at risk

The promises of freedom, democracy, justice

I feel the shift somewhere inside

If we hold up love, that’s what America will decide.”

June 11, 2020

Take Stuart’s collection for evening reading and inspiration as you knock on doors in battleground districts and states!

…

Love is Solidarity in Action – Stewart Acuff, International Publishers 2024

Desert Conversations

By Fred Glass

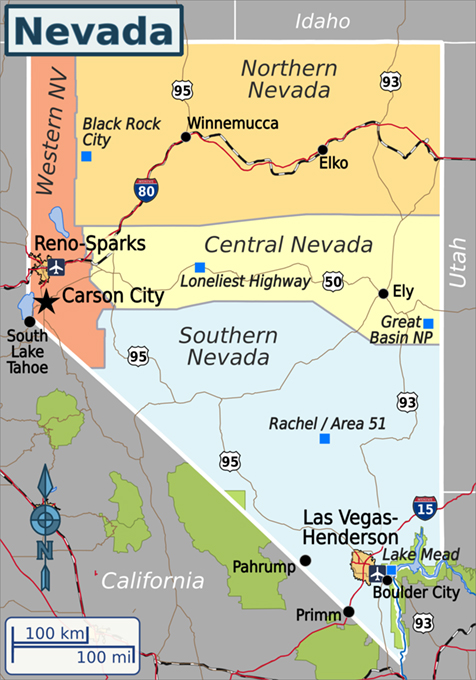

My Reno trip to canvass against Trump

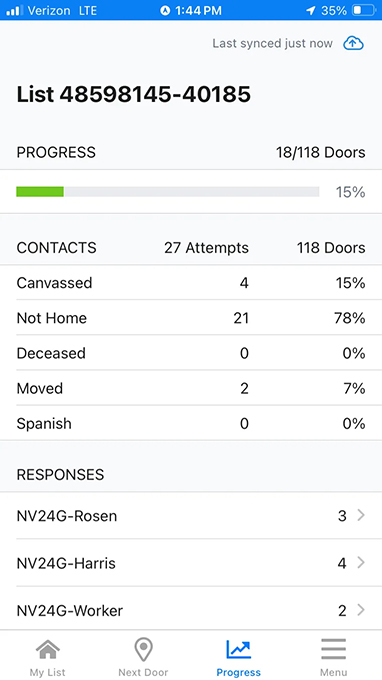

I spent three days last week in Reno, Nevada under the auspices of Seed the Vote, volunteering as a canvasser for the Harris-Walz campaign. Having canvassed in many campaigns over many years my expectations were low. I imagined I’d mostly knock on the doors of empty houses and apartments. That expectation was fulfilled.

Since our lists were of low-propensity voters, I also guessed when I did find people home I’d encounter large gaps where political knowledge should be. This too proved true. My personal goal was modest: stop 2024 in the United States from becoming 1933 in Germany (see my earlier Jumping Off Place article). I am less enthusiastic about the people I’m urging everyone to vote for than the historical function they will perform if elected: stopping the ascent of fascism.

Over seventy-two hours I had about ten actual conversations, including a couple potentially meaningful ones, and one honest-to-god conversion moment. I’m reporting here on three of the more interesting interactions, which occurred on the first day while trudging in ninety-degree desert heat from place to place in a working class suburb.

Conversation One: John, the nice Trumper*

You remember during the first years of the Trump administration when pundits and shellshocked naifs urged us all to reach out to uncles and nieces and former friends on the other side and “just talk” and then we’d find out how much we all really had in common? I found one in a trailer park rental complex, a tall, gaunt white seventy-nine-year-old named John.

When I told him I was a volunteer for the Harris campaign he asked if we could “just talk”, and told me he’s going to vote for Trump no matter what, but he wanted to hear what I had to say, because he doesn’t know what’s happened to this country that people can’t just talk with one another, and is that OK? I agreed to his terms. With each point I made (protection of the American Care Act, which Trump tried to repeal; Trump’s tax cuts for the rich, which meant less money in the federal budget for the needs of everyone else; his declaration that on Day One he’d be a dictator, etc.) John had a ready answer, none of which corresponded with any known reality, and a bottom line—“I trust him to do the right thing.”

When I left he said we’d given each other something to think about and politely thanked me for the discussion. This reception sharply contrasted with ones I received from other Trump supporters, the most civil of which was another old white guy who told me to leave so that he wouldn’t have to insult me. (On the opposite extreme, one of my canvassing partners was told through a smart doorbell to “get the fuck off my property and take your sacks of shit with you.”)

Conversation Two: The anarchists

In front of many homes in this neighborhood motorcycle, bicycle and car parts decorated the dusty yard; this was no exception. When I told Aurora, a thirty something Latina, I was there to ask for her vote for Harris she stepped out from behind the screen door onto the wooden porch and engaged. She said she couldn’t vote for Harris because she hadn’t distinguished her policy from Biden’s on Palestine, where United States bombs have been involved in an ongoing genocide. I surprised her by agreeing with the need for a ceasefire and withdrawing US military aid to Israel until that happens. But, I said, Trump would be no better on the issue and probably worse. Just as she was expanding her voting prohibition from Harris to all Democrats a voice said, “Behind you.”

A man about the same age as Aurora walked up with a machine part in his hand. We introduced ourselves and continued the conversation. Trevor repeated what Aurora had said, adding that he could no longer vote for Democrats after the way the party had treated Bernie; they’re as corrupt as the Republicans. I said while that’s true of the neoliberal half of the Democratic Party, the other half is made up of labor, women’s rights, civil rights, gay rights and environmental groups and sometimes it’s possible to get some progressive things done; meanwhile that’s completely impossible with the Republicans.

I said that what we’ve been talking about is only part of the picture; every US president is imperialist-in-chief internationally and it’s a mistake to think they can easily be persuaded to act differently. But there’s also the national side of the job, which involves important functions like appointments—to the courts and lesser-known agencies like the National Labor Relations Board, which can have an enormous impact on the working class, our rights, and daily life in the country. They listened but seemed unmoved.

I pulled out my trump card (sorry); under a Democratic administration there’s at least the room to move to protest destructive policies like Israel and Gaza. If Trump gets into office along with a Republican Congress, it’s going to be a police state this time around; things could look like Nazi Germany and much harder to mount any resistance. Aurora and Trevor nodded, like they had thought about this before, but didn’t comment on it.

Then Trevor said, “This is off to the side from what we’re talking about, but what do you think about no parties? Parties are how we have these problems.” Putting on my labor history hat, I said, “That’s what the Industrial Workers of the World wanted over a hundred years ago. Society would be run by workers’ committees, elected in each workplace. Their representatives would go to assemblies where decisions would be made.” He nodded. I said, “But unless you can tell me how we do that before November fifth….” He laughed.

Then he said that he knew of things that were going on that might “take Trump out” before Election Day. I asked what he meant. He said he couldn’t talk about it, but when that happened he hoped Kennedy could get back into the race and win. At this point I decided the conversation had achieved all its potential. We parted on friendly if inconclusive terms.

When I reported on this event with one of my canvassing partners she said, “Hunh, that’s different. Usually they kill the Kennedy and then someone else gets elected.”

Conversation Three: The truck driver

There’s no telling beforehand what issue might resonate with someone. Social Security typically works best for older people. But not always. At first, the twenty-seven year old man who came out to the porch after my canvassing partner Ralph and I knocked told us he had no intention to vote; politics didn’t matter; it’s all the same no matter who’s elected.

I said, “I assume you work for a living?” He said yes. What do you do? I’m a truck driver. You pay into Social Security? He nodded. I said, I’m retired, and I’m on Social Security. You’ve heard that they say Social Security might run out of money at some point down the road? He nodded again. I’m guessing you’d like to collect that money back that you’ve been putting into it? I had his attention.

I spoke about how Social Security is funded: payroll taxes. Workers pay in on their wages, and employers pay in a matching amount. But only up to $170,000 a year; anything over that is no longer subject to Social Security taxes. This is what puts Social Security in danger down the road: the many ways rich people have to get around paying their fair share of taxes, including this one. All we have to do is raise the cap so that rich people continue to pay in after $170,000 on all the money they make and Social Security will continue to be here for you, I said.

So who is better on this, and does it make a difference? We know that Trump won’t do that. In his first term he didn’t raise, he cut taxes for the rich. Kamala Harris wants to return taxes on the rich and corporations to higher levels. If you want to keep Social Security vote for Harris. So what do you think?, asked my partner Ralph. Juan smiled slightly: “You convinced me,” he said, and I could tell he meant it.

An encouraging sign

The three days in the hot sun were exhausting, but we were well-supported by our Seed the Vote organizers, who met with us each morning, gave us our lists, supplied us with water, phone batteries and snacks, and met again at the end of the day to debrief. One recurrent story gave some anecdotal hope for a victory margin in one cohort against Trump—and that’s what it was, less a vote for Harris and more an anti-Trump vote.

We heard this from people on the second day. One, a flight attendant in a more middle class suburb, told me she and her husband had been lifelong Republicans. But the craziness of MAGA plus persuasion from their two daughters, who had gone off to universities and come home politically transformed, put them over the edge. Now she was going to canvass for Harris, despite “some disagreements” that we didn’t get into.

The other, a retired architect in a very upscale neighborhood, spoke with my wife about his disenchantment with the Republican Party under Trump. He was an educated and cultured man, and couldn’t stand the lies and the vulgarities. He was going to vote the straight Democratic ticket. The seven people in our pod of canvassers had a number of similar stories from anti-MAGA ex-Republicans.

I haven’t seen any polling numbers among the old country club Republican ruling class set. Historically, ascendent fascism initially repels, and then reels in this demographic. It seems, however, from these encounters, and the growing number of Cheney types opposed to Trump, that the historic pattern might be abrogated here. We can hope.

.

*All the names are changed.

…

Nevada Unions, Democrats and the Fight for the Soul of Our Nation

By Joe Keffer

Voter Turnout Will Determine The Fate of Democracy

The stakes couldn’t be higher. Freedom and democracy stand in the balance. Union workers could well be the difference in a Vice President Kamala Harris and Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz November election victory.

This year, Nevada is one of seven battleground states that will likely determine the outcome of the presidential election and control of Congress. Since 2008, Nevadans have voted Democrat for president but by razor thin margins. Both U.S. senators and three of four Nevadans in the U.S. House of Representatives are Democrats; all women.

The AFL-CIO — and the affiliated federation of unions — have pledged millions of dollars nationally via donations, phone banks and door knocking to support Harris and Walz and down-ballot Democrats. Grassroots organizing paved the way for the recent victories. The Nevada AFL-CIO State Labor Council have mobilized its 120 union locals and 150,000 diverse members in building, construction and service trades, public worker sectors and more. Numerous other groups, such as Seed The Vote, Indivisible, the Progressive Leadership Alliance of Nevada (PLAN) and the Third Act are spearheading voter turnout.

The politically powerful Culinary Workers Union Local 226, which represents 60,000 hospitality workers, — the largest Latinx/ Black/Asian American Pacific Islander/ immigrant organization in the state — is turning out an army of precinct volunteers in support of Harris and Walz and down-ballot races.

Union President Peter Finn, speaking for 300,000 Joint Council 7 & 42 West Coast members, includingNevada Teamsters, has endorsed Harris, Walz for president and to re-elect Sen. Jacky Rosen. As truck drivers, rail workers and freight handlers, their working class credentials and votes hold importance. Finn says we “refuse to be divided by extremist political forces or greedy corporations that want to see us fail.”

At the Sept. 10th presidential debate, one question posed to Harris and former President Donald Trump squarely placed the strength of the economy as the centerpiece of the election. Voters’ pocketbooks have traditionally played a huge role in the outcome of presidential elections. In 1992, Bill Clinton’s campaign captured this sentiment with the famous quip, “It’s the economy stupid.” Recently, housing costs have had a significant economic impact as fewer people can afford a house or pay the increased rental costs.

A Las Vegas Review-Journal article reinforces the argument that housing is a top issue in Nevada, and nationally. It blames the 2008-2009 financial crash, the COVID pandemic, and corporate investors who have purchased many of the available houses and turned them into exorbitantly high cost rental units. Harris has shown an understanding of the issue’s severity and proposed a detailed remedy.

Rep. Steven Horsford (D-NV), chair of the Democratic Black Caucus and co-chair of House Labor Caucus, blasted the corporate investors’ takeover of the housing and rental markets, and last year sponsored a bill to cap predatory investor home renting and selling practices.

Biden and Harris pledged hundreds of millions of dollars for affordable housing initiatives. Early on, they signed the Build Back Better and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs acts that include rental assistance for Nevadians. Horsford says that the acts “create millions of good paying union jobs, cut taxes for most Nevada families that have children, and lower the costs of essentials like housing, health and child care.”

The infrastructure law earmarks $3.5 billion for Nevada including more than 275 projects for roads, bridges, public transit and airports. This includes funding for Harry Reid International Airport, the high-speed rail line between Southern California and Las Vegas, electric vehicle charging, cost-free high-speed internet, and amelioration of the Lake Mead and Las Vegas Wash drought conditions.

Biden and Harris passed the Inflation Reduction Act that confronts the climate crises by expanding tax credits for clean energy and electric vehicles that will reduce the need for oil and other fossil fuels. Its goal is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions 40 percent below 2005 levels by 2030. More than 100 million people face extreme heat, forest fires and violent storms. Coastal communities are predicted to experience a 10–12-inch rise above sea level. The law provides $52.7 billion for semiconductor research, workforce development, domestic manufacturing, and creation of zero emission technologies. Nevada is well situated with an abundance of lithium, copper, magnesium, barium, and vanadium that are non fossil fuels and “critical” to meet the goals of the Inflation Reduction Act, and a greener future. This has the potential to create whole new industries and jobs.

The problem for Biden and now Harris is whether the benefits of the legislation will come in time to influence voters in November. The law “has undoubtedly been a boon

for Nevada, bringing in unprecedented federal dollars, spurring private investment and creating jobs. But, the gap between its passage and tangible results could be its undoing. If they win in November, Republicans have threatened to revoke many of the law’s provisions, halting progress before it even begins.

Rob Benner, secretary-treasurer of the Building and Construction Trades Council of Northern Nevada, says the union has already secured a project labor agreement to do construction. “We have all these burgeoning industries getting ready to just take off and totally transform Nevada … That could all stop and then we are back to square one…” Experts and industry watchers say a perfect storm of factors makes Nevada poised to capitalize on the laws. Nearly 250,000 clean-energy jobs have been announced in Nevada since the laws’ passage.

Harris and her allies must convince the public that, while voters have a right to feel anxious about the delays, given Republicans threats to revoke the legislation, her election is the only way that they will likely see significant job increases and lower energy prices.

Republicans are well financed. Megadonor, Miriam Adelson, owner of the Las Vegas Review-Journal, is the lead financier of a spending group backing Trump. She plans to do whatever it takes to help him win. Her family gave $218 million (https://www.reuters.com/world/us/republican-mega-donor-adelson-back-major-pro-trump-spending-group-2024-05-30/) in the 2020 election cycle and is expected to give similar amounts this year— all to Republicans and conservative groups.

At the Republican National Convention (RNC), Trump said he supported unions. His pitch, in the 900-pageProject 2025, developed by 140 former staff and associates of his administration, flies in the face of pro-worker and green economy policies for running the country. As Michelle Maese, president of the Southern Nevada SEIU Local 1107, a public employees union says, “Their goal isn’t to fix our government or our country. It’s to break it even more … “It would be an absolute disaster.”

With the nomination of Harris and Walz, Democrats have the momentum. Democrats accuse Republicans of having presented no substantive policies but to base their campaign on hate, fear, lies, gross exaggerations, and past grievances. Commentators report that Republicans appear to be on the defensive and that blunders have damaged their campaign. They believe that crowds at his rallies are down. Plus, questions exist about whether his ticket has the energy, character and mental stability to lead the county, and the free world.

Biden and Harris have made major efforts to prove their labor bonafides. They walked picket lines, backed labor legislation and appointed strong worker advocates to the National Labor Relations Board. Biden has been called the most pro-union president in history. Harris has visited Nevada at least eight times. Unions, Democrats and progressives have the power and unity to win.

On the first night of the Democratic National Convention (DNC), Democrats showcased leaders of unions and their allies amidst deafening chants of “Union Yes” and “We Are Not Going Back.” The crowd exploded in response to Harris’ acceptance speech. She called out to go forward with strength, empathy, joy, and unity. Former President and First Lady Barack and Michelle Obama wrapped up day two of the DNC with the admonition that we have to spend all our energy fighting for democracy. In support, the unions have near unanimity on who is on their side. With that thought in mind, convention attendees took up the chant: “When We Fight, We Win!” Labor will be a big part of that fight.

…

“A CALL TO ACTION” – The Case for a Professional Combat Athlete Union

By Ernest DiStefano

Abraham Lincoln said, “If you want to know a man, give him power.” Well, UFC (Ultimate Fighting Championship) President Dana White has certainly made himself and his attitude toward power known to all of us. It’s simple: he abuses it. We need only to listen to his words and witness his actions to know this. Here are just a couple of examples.

- On UFC Fighters’ pay raise and benefits, he said the following about unionization:

“It’s never gonna happen while I’m here…Fighters get the pay they deserve. They eat what they kill.”

“Right now in our society, everybody gets a fucking trophy. Well, this is the fight game, and we don’t give out fucking trophies.”

Professional combat athletes have earned and deserve their so-called “trophies” of fair financial compensation and benefits through the countless gallons of blood they have shed, bones they have in broken, and in many cases, lives they have lost in Mr. White’s octagons and boxing promoters’ rings throughout the world. As long as there are people like Mr. White running the combat sports industry, there will always be a need for professional combat athletes to protect their interests and their families’ interests through union organization. In this essay, I will address the “Why” and “How” for this long overdue undertaking.

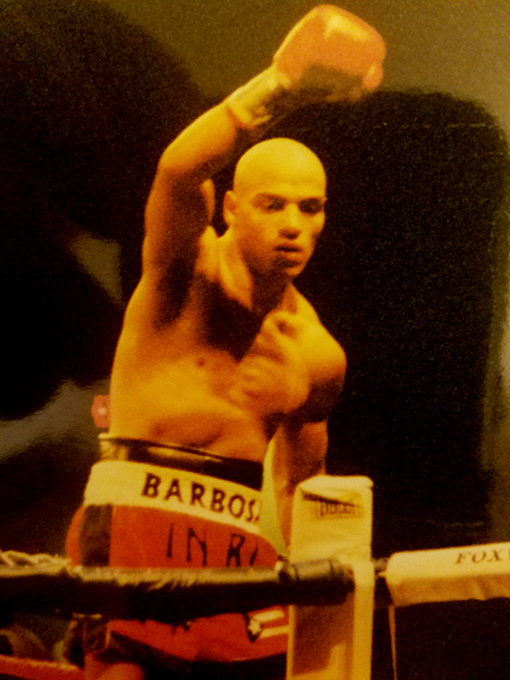

“Because it’s all I know.”

An illustration of this reality is the life of former professional boxing champion, Brian “The Bull’ Barbosa. Through my personal experience assisting Brian, I have come to know the incredible challenges he faced at a very young age. Brian endured extreme poverty and abuse as a child, which drove him to the boxing gym, which in turn resulted in a professional fight career. Although Brian was rewarded for his efforts in the ring with a world championship, he also sustained serious brain trauma and injury, as well as manipulation and mistreatment by the fight professionals who were supposed to be looking out for his best interests. When I first spoke with Brian, he expressed a desire to resume his fight career. When I asked him why, Brian said, “because it’s all I know.”

On September 21, 2021, Brian courageously shared his story on the Dr. Phil Show. Brian continues to battle the inner demons created by his physical and personal trauma and is currently receiving treatment to exorcise those demons.

During my conversations and my professional experiences with other combat athletes, they have consistently identified the following two issues as priorities with respect to their fight careers:

- Brain Health and Brain Injury Prevention

- Fair and Equitable Distribution of Revenue

The following facts will illustrate the importance of addressing these two areas.

Brain Health and Brain Injury Prevention

Brain injuries impact any human being’s ability to function on a daily basis, which in turn negatively impacts one’s ability to make a living for themselves and their families. In the past 131 years, 1,878 boxers have died as a direct result of injuries sustained in the ring. This is an average of more than fourteen deaths per year and more than one death each month. Prior to that, from 1740 to 1889, when boxers fought bare-knuckled (a sport which is currently growing in popularity), there were 266 documented deaths (Source: “Death in the Boxing Ring,” by Rupert Taylor). Since MMA’s inception in the mid-1990’s, there have been sixteen reported deaths among MMA fighters directly related to injuries sustained in the Octagon (Source: “How Many Fighters Have Died in the Ring: Boxing and MMA,” by Ross Canning).

A 2015 research study, “Epidemiology of Injuries in Full-Contact Combat,” written by Reider P. Lystad of Central Queensland University, Sydney Australia, found that the proportion of neck and head injuries for the sport of boxing was 84%; 74% for karate; and 64% for MMA. This research showed that Karate had a concussion rate of 19%, Boxing had a concussion rate of 14%, and MMA had a concussion rate of 4%. Further it showed that MMA had the vast majority of life-threatening or life-changing injuries as a result of heard trauma, while also revealing that professional boxers were: 1) more likely to experience loss of consciousness, 2) more likely to suffer eye injuries (detached retina), and twice as likely to sustain concussions that involved loss of consciousness. This research showed that medical suspensions for boxers were a minimum of twenty-six days, compared to medical suspensions for MMA fighters, which are for an average of twenty days.

On the question of “why,” many non-fight fans have undoubtedly wondered why they should care about the men and women who choose to participate in a sport where the amount of pain and injury they inflict on their opponents are markers of success, well Walter Mosely summed it like this, “poor men [and women] box because it’s the only choice they have. A poor man [or woman], of any color, is fighting for their life in the ring. And the only reason they’re fighting for their lives in the ring, is because it’s a little bit safer than fighting for [their] life on the streets of America.”

My own experiences working with professional combat athletes, criminal offenders, and prison inmates, (three categories that way too often overlap) have taught me that desperate human beings without hope will resort to behaviors that endanger the lives and property of other human beings, including non-fight fans, and THAT is why they should care.

Fair and Equitable Distribution of Revenue

An article published online by Huddle Up Magazine on 5/31/23 convinces me that Dana White has taken his greedy, narcissistic sociopathy to a disgusting new level. In that article, it was reported that although the Ultimate Fighting Championship organization’s (UFC) annual revenue increased from $1.03 billion in 2021 to a record $1.14 billion in 2022, the percentage of revenue that the UFC paid to its fighters decreased over that time from $178.8 million to $146 million in 2022. Huddle Up further reported the following comparison between professional sports leagues of the percentage of annual revenue paid to athletes:

MLB-54%

NBA-50%

NHL-50%

NFL-48%

UFC-13%

There is one glaring difference between the UFC and the other aforementioned professional sports leagues that accounts for this immense discrepancy in revenue distribution: the MLB, NBA, NHL, and NFL all have players’ unions.

“How?” – Legal Precedent

With respect to combat athlete unionization, the legal question that must be resolved is whether combat athletes are employees of their promoters or independent contractors. On this question, a legal precedent was established by the California State Supreme Court on April 30, 2018, in the case of Dynamex Operations West, Inc. v. Superior Court and Charles Lee, Real Party in Interest (Sources-CA.gov and Wikipedia). In that case, a class of drivers for a same-day delivery company, Dynamex, claimed that they were misclassified as independent contractors and thus unlawfully deprived of employment protection under California’s wage orders.

In a unanimous opinion, the California Supreme Court held that workers are presumptively employees for the purpose of California’s wage orders, and that the burden is on the hiring entity to establish that a worker is an independent contractor not subject to wage order protections. The Court also held that in order to establish that a worker is an independent contractor, the hiring entity MUST prove each of the three parts of the “ABC” test. The three conditions of this test include the following:

- Part A: The worker is free from the control and direction of the hiring entity in connection with the performance of the work, both under the contract for the performance of the work and in fact;

- Part B: The worker performs work that is outside the usual course of the hiring entity’s business; and

- Part C: The worker is customarily engaged in an independently established trade, occupation, or business of the same nature as that involved in the work performed.

Now, let’s examine the ABC test as it applies specifically to the combat sports industry. This examination is based solely on the observations and assessment of this writer and not on any Court rulings pertaining to the combat sport industry. Remember, under the ABC test of the Dynamex ruling, if the answer to any of these three tests is “No,” the worker is legally required by California law to be classified as an employee of the hiring entity.

Part A:

Is the professional combat athlete (the worker) who is under contract with a promoter (the hiring entity) free from the control and direction of the hiring entity in connection with the performance of the work (i.e., boxing/martial arts bouts) both under the contract for the performance of the work and in fact?

When a professional combat athlete (the worker) signs a contract with a promoter (the hiring entity), said combat athlete is legally bound to perform his/her work (boxing/martial arts bouts) solely for his/her promoter. Furthermore, the promoter has final say over who and when the contracted combat athlete fights, and the amount of the combat athlete’s compensation for the work performed. Furthermore, the contracted combat athlete is not permitted to perform the work for entities other than the promoter.

Answer: NO.

There we have it. There’s no need to go further, but I will.

Part B:

Does the combat athlete perform work that is outside of the usual course of the promoter’s business?

Answer: NO.

Part C:

Is the combat athlete customarily engaged in an independently established trade, occupation, or business of the same nature as that involved in the work performed?

Answer: NO.

What does it mean if fight promoters are the employers of professional combat athletes? It means that promoters are legally required to follow employment laws governing working conditions including minimum wages, and all laws pertaining to conditions of employment. It also means that promoters are required to pay taxes for social security, workers’ compensation, unemployment insurance, as well as payroll and unemployment taxes. It could also possibly require promoters to recognize and collectively bargain with a combat athlete union. This premise will be tested when combat athletes organize and petition for a union with the National Labor Relations Board.

I now ask a question to licensed professional combat athletes-boxers, martial arts fighters, and wrestlers-especially those licensed in the state of California: Based on your experiences in the professional combat sports industry, do you honestly believe promoters would voluntarily pay any of the aforementioned fighter benefits? If your answer is what I think it is, then your course is clear!

…

The Cornel West campaign, third parties and the nature of the moment

By Bill Fletcher, Jr.

The most obvious example of this was the victory of Barrack Obama in 2008 as President. It is not that the victory was without historic significance. Rather, the historic significance dwarfed discussions about program and action, particularly in the first year of his Administration.

I have known Cornel West since 1972 when we met during my first year at Harvard. I have followed him over the years and felt, at points, that I could call him a friend. That said, his campaign for the Presidency raises some very serious questions regarding both his judgement and what seems to pass for strategy, not only for West, but for many others on the Left and in the progressive movements. My views are focused on his decision to run and the campaign that he allegedly is conducting, rather than on personal allegations raised about him, most visibly in Forbes.

Are progressives interested in winning, and if so, what?

Since the late 1970s, progressives have been largely fighting a rear-guard defensive battle against the assaults from capital and the increasingly brazen political Right. The public has observed the morphing of a conservative movement into a rightwing populist movement with fascist or post-fascist tendencies. Though there have been successful defensive fights and periodic offensive victories by progressives, e.g., on LGBTQ, the tendency has remained one of a strategic defensive.

An ideological reflection of the strategic defensive has been the victory of Reaganism through ridicule and dismissing of collective action in favor of individual action and, indeed, individualism and entrepreneurialism. Even in progressive circles, the obsession with “brand” and individual achievement has become pronounced. This has worked its way into non-profit circles, where collective or joint action is rarely championed (or rewarded), whereas the uniqueness of each organization or network is applauded…until it is not. Everyone wants their ten minutes in the Sun, even if it leads nowhere.

In this context, a few things became noteworthy. Victories, when won, became increasingly victories in form rather than substance. The victories of “representation,” in the sense of historically marginalized groups appearing to break through the glass ceiling is a case in point. The most obvious example of this was the victory of Barrack Obama in 2008 as President. It is not that the victory was without historic significance. Rather, the historic significance dwarfed discussions about program and action, particularly in the first year of his Administration.

The net result is that progressives have become used to losing. Losing can be glorious, after all. One can lose by oneself or with others. One can lose ‘speaking truth to power.’ One can lose and be remembered for having taken a heroic stand. Regardless, one loses.

The difficulty with winning, or at least attempting to win, is that it can be messy. Rarely do the advocates for a particular cause, demand, etc., win alone. Normally, victory necessitates alliances, and alliances necessitate compromise. As a result, there is no purity in winning even if one wins exactly what one sought to win.

As such, it is easier and more valiant to lose than to win. In losing, one can hold onto one’s conscience. One said what needed to be said. One need not have made any compromises with those less pure. Nevertheless, at the end of the day, one lost.

Winning necessitates strategy and organization. It is never about pronouncements alone. It involves the cultivation of a base that believes in and is prepared to sacrifice for a particular cause or demand. Winning, except under very unusual circumstances, necessitates the identification of tactical steps necessary to bring about victory. This might range from increasing pressure to building even broader alliances. Victory may come quickly, but normally not. It may, however, come suddenly, sometimes when one least expects it.

And winning must be secured. Once something has been won, it must not only be defended, but used as a launch pad for additional struggles and campaigns, all with the end of decisively defeating one’s opponents and liberating one’s base.

Politics of self-expression and frustration

Which brings us to the Cornel West campaign and other third-party bids during the 2024 election cycle. What is the essence of such ventures?

If one is interested in building a struggle for power, one does not begin by running a Presidential campaign, and certainly not a campaign with no organized base and no possibility of victory. If, however, one is concerned more with asserting one’s beliefs and expressing one’s frustration and antipathy toward the existing system, one can view a campaign for the Presidency as an on-going platform to both hear oneself talk, but also to try to captivate and entertain an audience. Such politics become not the politics inherent in a struggle for power, but the politics of self-expression. The objective becomes expressing one’s views, anger, etc., rather than seeking to achieve anything. In effect, it becomes the politics of defeat, in that one has no plan, knows one cannot win, and therefore cries out in hopelessness.

The West campaign and other third parties will virulently object. They will assert they are taking a stand against the two-party system of the capitalist class; a stand against imperialism; against the criminality of the US support for Israeli genocide. And they will be correct! They are. Yet, they have no plan, nor sufficient organization, to transform their assertions into political power. Thus, they can only rely on magical thinking in the hopes—and this is a best-case scenario—that their plea to the masses will resonate and result in a great wave of revulsion against the system, thrusting them into office…alone.

The moment

Leaving aside, for a moment, that minor parties in the USA have rarely been successful due to the undemocratic nature of the US electoral system, the actions of the Cornel West campaign and other third parties would be comical if less were at stake. And there have been times when comedians have run for President to make a satirical statement, e.g., Pat Paulsen.

Current third-party candidacies, including West and Jill Stein, either ignore or deny the dangers inherent in the current moment. West, for instance, acknowledges the dangers of a Trump victory but asserts, in part due to the Israeli genocide in Gaza, there was no difference between Trump and Biden and, apparently, no difference between Trump and Harris. Stein’s views carry on from the historic and, unfortunately, dogmatic stand of the Green Party on the need for formal political independence from the two-party system.

None of them are coming to grips with the dangers over the horizon. There is nothing, for instance, on the Harris side that is comparable to the plans of the MAGA movement such as Project 2025, the Heritage Foundation’s hatched idea for a rightwing authoritarian overhaul of the US government. There is nothing comparable on the Harris side to the proposals that the American Legislative Exchange Council’s ongoing work to advance a Constitutional Convention to alter the US Constitution in favor of business and the Christian Right. Nothing.

One cannot conclude ignorance on the part of any of these campaigns. One cannot imagine that any of these campaigns believe that progressive politics and policies will survive a second Trump presidency. Or perhaps they do? As many of us have heard over the months, there are those who believe that Trump will not be but so bad and, yes, there will be suffering, but we will come through it.

Who is “we”? Those picked up in military scoops of immigrants and placed in concentration camps? Those assaulted or killed should Trump utilize the 1807 Insurrection Act against protesters? Those killed through the use of paramilitary extrajudicial violence by fascist supporters of Trump? Workers who lose out when the National Labor Relations Board regresses to the anti-worker animus, or when the National Labor Relations Act is eviscerated? Women, whose bodies increasingly become the terrain of rightwing, male politicians? Or, is the “we,” those from the professional-managerial strata who believe they can hunker down and wait for the turbulence to subside?

The choice has never been between an enemy and one of us

The politics of self-expression makes three mistakes. First, it assumes that we can reject the two candidates and, by doing so, a third will ultimately emerge. Second, that an enlightened leader can emerge without an organized social base and, in the absence of support in Congress, introduce dramatic changes that will bring us closer to utopia. Third, that the two main candidates will demonstrate the corruption of the current system and will encourage the masses to turn in a revolutionary direction. Fourth, a Trump victory will allegedly punish the Democrats so that in four years they will pick a better candidate.

What is striking about each of these notions is that there is no historical basis to see any of this happening. There are, however, plenty of examples where abstention, for instance, has created an opening for a nefarious political force to emerge and win office. In fact, one can look at Germany in 1932 and see one of the results of a failure to build a broad front to oppose the Nazis because, in that case, the Social Democrats and the Communists so hated each other, they lost sight of what could happen should the Nazis win.

The second and fourth mistakes, though, are the ones that are the most interesting. The assumption that a third-party candidate, in the absence of organization at the base and any support in Congress could do anything is mind-boggling. Consider the Obama administration and the difficulties it had in its first two years—when it had majorities but believed it could play adult with Republicans—not to mention what succeeded that after 2010. This thinking evidences the absence of any conception of a fight for power. It is either magical, or it is yet another example that the politics of self-expression is the politics of defeat.

The fourth mistake is one that is heard frequently. It is less the politics of self-expression and more the acceptance of the permanence of the system and the inability to conceptualize that a strategy can be constructed that goes beyond pleasing or punishing the existing parties, and instead offers an alternative based on real mass work, organization, and strategy.

Going forward

It is less important to get inside Cornel West’s head, or the heads of the other candidates, than it is to question not only their intent, but why they garner any attention. The answer is simple. Frustration with the system; the fact that the lives of the majority of people are miserable; and a belief that regardless of what we do, nothing will change, leads to treating the November 2024 elections as if it is an election in American Idol, that is, entertainment where the result will be completely irrelevant to the daily lives of the viewers.

Those of us who appreciate the stakes in 2024 must use the coming weeks to point out precisely what the possibilities are. This is not an election between a hero and a demon. This is an election where a semi-fascist mass movement, MAGA, seeks to upend constitutional democracy in order to introduce rightwing authoritarianism. And this upending will be paradoxically quick as well as spaced out over time. That is the way authoritarians operate. They almost never clamp down on everyone at once, even in military coups. There are always parts of the population who believe—hope—they are exempt from repression. At least until there is that knock at the door…

…

Profiles in Political Cowardice

By Max Elbaum

“Throughout the socialist left – and more broadly in almost every sector of the electorate – people are wrestling with what to do when they enter the voting booth. There is a choice to be made.“

Fighting effectively for social transformation is hard. Socialists and revolutionaries don’t square off against our class enemies on any kind of level playing field. The country’s political structures are formidable barriers to radical change. We don’t have the luxury of determining the terrain on which we fight or the timetable on which battles will be waged. We have to deal with the specific circumstances shaped by forces far more powerful than we are.

So, we make the best assessment of the landscape and balance of forces that we can, choose a course of action, and then throw ourselves into implementing it. When a particular campaign or stage of struggle wraps up, we look at the choices we made, learn from what we got right and what we got wrong in both conception and execution, and make the next set of tough choices.

In 2024 the tough choices facing U.S. socialists are front and center. An authoritarian MAGA bloc that incorporates openly fascist elements at all levels of its apparatus is bidding for enough power to impose its white Christian nationalist agenda on the country. The most powerful current in the opposition offers an alternative agenda on numerous important issues but is complicit in Israel’s genocidal war in Gaza and has caved to right-wing fear-mongering on immigrant rights. A general election is approaching whose outcome – especially at the presidential level – will be decisive in determining whether MAGA or anti-MAGA holds federal power for the next four years. Throughout the socialist left – and more broadly in almost every sector of the electorate – people are wrestling with what to do when they enter the voting booth. There is a choice to be made.

Tempest: Ready, Set… Punt

The Tempest Collective was formed largely by former members of the International Socialist Organization (ISO) soon after the ISO disbanded in 2019. Tempest describes itself as “an organizing and educational project. Our goal is to put forward a revolutionary vision that is clear and understandable, that weighs in on strategic and tactical questions, and that offers concrete guidance about how to put a consistent set of working-class politics ‘from below’ into practice today.”

Tempest has published two articles by Collective members on the 2024 elections this month. Let’s see what “concrete guidance” is offered in those pieces. Author Ashley Smith writes:

“…we must be crystal clear: The two candidates and parties are not the same and it is an ultra-left mistake to characterize them that way. The greater evil is obviously Trump and the far-right GOP. He, not Harris, is threatening the deportation of 13 million human beings and the criminalization of queer people. Harris and the Democratic Party are lesser evils by comparison. But that does not exonerate them of being evil.”

Smith’s article also asserts:

“In this epoch of political instability, socialists must develop a strategic approach to elections. We are not anarchists; we do not dismiss elections as irrelevant to the class struggle. Electoral politics are one of the battlefields of the class struggle.”

Putting those ideas together, the article says:

“…what should the Left do? First of all, we should not argue with individuals about what they do at the ballot box. That is not the key question and debate to have. Instead, we must argue that activists, social movements, and unions should not spend our time, money, and energy campaigning for Harris as the lesser evil.” (The other Tempest article, by Collective member Natalia Tylim, offers the same punchline: “I want to stress that I’m also not going to spend my time or resources arguing with individuals about how they vote as individuals out of their fear of Trump.”)

Wait a minute. The left, and those paying attention to what left groups and leaders think, is debating electoral strategy. That strategy is not limited to – but certainly is commonly understood to include – a stance on who to vote for or against. An electoral strategy that refuses to take a position on who people should vote for is not a strategy; it’s a refusal to make a tough choice. Or in Tempest’s terms, to offer “concrete guidance” to those you seek to influence.

What we have here is a new twist on an old adage:

When the going gets tough, the tough…. change the subject.

DSA Leadership Redefines the Word “Bold”

The new “Workers Deserve More” program for 2024 recently announced by the national leadership of DSA is similar in essential respects. In a vein similar to Tempest, the program declares:

“We recognize that a second Trump victory would be catastrophic for the international working class. Relying on the Democrats to defeat Republicans isn’t working.”

In the preamble, the DSA leadership lays out their view of dilemma US voters face and offer their guidance as to how to proceed:

“In the 2024 elections, working people have few good options. In most races, Americans will have the choice between far-right Republicans and corporate Democrats. In both cases, workers lose, and our politicians will remain controlled by their corporate donors, not the ordinary people who voted for them…. Neither major party is capable of advancing a positive program for the 2024 elections that meets the needs of the majority of Americans. That’s why the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) is presenting a bold alternative course of action. In our 2024 program, “Workers Deserve More,” we hope to bring together millions of people throughout the U.S. to fight for a true democracy where working people have control over their own lives, their government, and the economy.”

What follows is a list of 18 demands/programmatic goals (Medicare for All, Tax the Rich, Free Palestine, etc.).

Again, wait a minute. Isn’t something missing? That list of programmatic goals is good. But aren’t similar lists put forward by many progressive and left organizations? And is fighting for them really an “alternative” to taking a stand on who people should vote for in 2024? Doesn’t the DSA text imply that prospects for making headway toward those goals would be immeasurably more difficult under a Trump administration than a Harris one? Isn’t calling it an “alternative” just another way of saying we don’t like the options so we’re taking a pass on making a choice? What is “bold” about that?

And how about some candor about why no recommendation is being made? Pretty much everyone in or anywhere near DSA knows that members of the organization – including members of the national leadership body – are badly divided on who to vote for in 2024. Is there a reason not to come out and say so? Isn’t one of the hallmarks of “democratic socialism” supposed to be that it rejects the practice of a left organization or party projecting an image of monolithic unity to the working-class public when that is not the case? Where is the credibility in an organization saying it hopes to “bring together millions of people across the US to fight for a true democracy” when it won’t offer any guidance on who workers should vote for two months from now or explain one of the reasons it is sitting this one out?

“Revolutionary Phrase-Making”

It’s no secret that I advocate a vote for Kamala Harris in 2024 to prevent the MAGA authoritarians and fascists from taking control of the federal government. I’ve argued in numerous articles and webinars that advocacy of abstention or a third-party vote is a profound error that underestimates the danger of MAGA, misunderstands the way working-class and revolutionary organizations can build political power, and does nothing to strengthen our immediately urgent or long-term Palestine solidarity efforts. (See here, here, here, and here.) But a certain respect is due to those who advocate abstentionism or third-party voting: they put their politics out there and fight for them. That’s a serious way to do politics.

Respect is also due to most issue-based and constituency-based organizations that do not offer a who-to-vote-for recommendation. Matters regarding the specific issue which is their main focus, the sentiments within their base, and/or internal differences in groups whose main focus is not electoral need to be taken into account. And the main thing is that such groups do not promote themselves as offering a revolutionary vision for the US working class or as building a new party that will lead the working class to socialism.

Organizations that do self-identify that way and issue pronouncements about the tasks of socialists in today’s class struggle have greater responsibilities. They need to be held to a higher standard. Part of their responsibility is to make tough choices, or in cases when they cannot make a choice, straightforwardly explain why.

There is an unfortunate history of organizations not doing so and, like Tempest and the DSA national leadership today, substituting “bold” radical pronouncements for biting the bullet and making a difficult choice. There is even a term for this practice – “revolutionary phrasing-making” (or “the revolutionary phrase”) – coined by none other than V.I. Lenin:

“Revolutionary phrase-making…is a disease from which revolutionary parties suffer…when the course of revolutionary events is marked by big, rapid zigzags. By revolutionary phrase making we mean the repetition of revolutionary slogans irrespective of objective circumstances at a given turn in events, in the given state of affairs obtaining at the time. The slogans are superb, alluring, intoxicating, but there are no grounds for them; such is the nature of the revolutionary phrase.”

“Superb, alluring, intoxicating…” – perfect for battles on twitter or Facebook and the publication of “bold” programs. Unfortunately, outside of actual revolutionary situations, practicing working class politics usually involves making choices between less-than-ideal options. No radical organization or party will get those choices right every time. But organizations with an aversion to choosing, and especially those that encase their taking a pass in clouds of radical rhetoric, are avoiding rather than engaging with objective circumstances and are traveling a dead-end road.

…

Book Review: Ground Wars – Personalized Communication in Political Campaigns Rasmus Kleis Nielsen – 2012 Princeton University Press

By Peter Olney

“the deciding factor is “not the margin of error but the margin of effort”

Friends and comrades are deploying to battleground states that will be determinative in this year’s Presidential race

Harris will win the popular vote, as Biden did in 2020, but the undemocratic electoral college means that the election will come down to a few thousand votes in states like PA, MI, NEV, AZ, GA and Wisconsin. Therefore, the anti-MAGA majority needs to be motivated and mobilized to vote. The always insightful political analyst Michael Podhorzer keeps saying that the deciding factor is “not the margin of error but the margin of effort” That means that the difficult and often distasteful work of phoning and door knocking is crucial to victory.

Guidance and insight for this work comes from a remarkably surprising place: a Danish Sociologist named Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. In 2008 he embedded himself in two Congressional campaigns: New Jersey Democrat Linda Stender and Connecticut Congressman Jim Himes. Hours of door knocking, phone banking, letter writing and observation of the mechanics of a campaign are reflected in the most evocative description of my own experience in on the ground electoral politics. The book is peppered with episodes describing phone calls, encounters on the doors, or discissions with campaign staff and volunteers.

The book describes three important factors necessary to understanding the “Ground Wars”:

- Temporary Infrastructure – In the earlier days of “machine politics” there were permanent functionaries at the local level, often patronage jobs, who functioned as frontline communicators. Today’s local party apparatus is called into being for a fixed time leading up to the election, often including a primary contest and then the general. By definition and necessity these short-term positions are filled by recent college graduates and folks who can afford committed short term employment.

- Coalition forces – There are the official campaigns of the Party and then there are the Independent Expenditure (IE) operations and the work of organizations like labor unions. The IE work cannot cooperate or coordinate with the campaign by law, and the unions are forbidden from using paid staff and resources to reach anyone but their own members – a limited pool when unions represent only 6% of the private sector workforce.

- Volunteers – Every campaign wants volunteers en masse but coordinating them and dovetailing their often spotty and uneven efforts with that of paid staff is very challenging. Sometimes they think they “know best” and they can be a major irritant.

“… pain in the ass prima donna second guessing the work of the campaign structure”

I thank my longtime friend Henry Hardy from Greenfield, MA for turning me on to Ground Wars. He will be deploying to PA for 5 weeks during the general election. He said the book helped him to avoid becoming a “pain in the ass prima donna second guessing the work of the campaign structure” I came away feeling the same way after reading the book.

I have worked elections every two years since 2016 and as a long-time labor organizer have had certain criticisms of campaign functioning involving basic training and logistics issues. Campaign staffers with little direct experience to lean on train up door knockers, and phone bankers on endless scripts that will not last a minute out on the hustings. Logistics planning can also often be lacking. In 2022 I drove 21 miles for a literature drop in Fullerton, California at 5:30 AM and found out I was the only one there and that the staffer who had sent me there had forgotten to tell me that the drop had been called off. I have learned however to keep my mouth shut in most instances, and Ground Wars was a big help for my psyche in avoiding carping on the campaigns.

Here is Henry’s brief excellent roundup on the book:

“This is a great nitty-gritty description of the contemporary “ground war” in American electoral politics. Nielsen likes to refer to it as “personal political communications” because he likes to view it as one of the main political media (along with direct mail, broadcast/cable advertising, internet advertising, social media communications, and free media coverage). He sees it as making a comeback since the early 90s (volunteer activity up from 2% of the adult electorate to 4%), and as working (estimates one in every 14 door knocks brings an additional voter to the polls). He also makes it clear how boring and stressful the work is for most involved, consisting as it does almost exclusively of cold-calling and door knocking to persuade the persuadable and get the “lazy faithful” to the polls. He also does a great job of outlining the complex improvised organizational “structure” of the ground game, which (in order to be most effective) requires the coordination of various parties, campaigns, allied activist groups, and differently motivated volunteers and wage workers”

It is not too late to get a copy of Ground Wars to read at night after a long day on the doors beating Trump and fighting for democracy.

.

For more on working and working on the elections, read the series on the Stansbury Forum:

Why I Keep Coming Back, There Are Many …, and Knocking The Doors #1: Working in CA45th CD

…

Why I Keep Coming Back

By Katie Quan

“Some might think I’m crazy, but to me it’s thrilling, because it’s one of the best examples of what a union can do.”

This year I am spending several months of my retirement with the UNITE HERE election campaign in Reno, Nevada, heading its volunteer operation, something I have done now for four election cycles. Why would I volunteer for 12 hours a day, in 100 degree weather in the summer, and snowy conditions in November? Some might think I’m crazy, but to me it’s thrilling, because it’s one of the best examples of what a union can do.

UNITE HERE in Nevada, known as the culinary union, represents more than 60,000 hotel and food workers in the Las Vegas area, and several hundred in Reno. By all accounts, its canvassing operation is a game-changer in Nevada politics. While the Las Vegas area is reliably blue, and the state’s rural counties are reliably red, the Reno area is roughly a third Democrat, a third Republican, and a third independent. So the Reno area swings the state. Every vote really counts.

UNITE HERE’s canvassing operation in Nevada is second to none. I’ve participated in and even led political campaigns in past decades in battleground states, but none compares to the strategy and rigor of the culinary union’s operation. UNITE HERE targets certain voter populations and mobilizes its members to knock on doors. The members are housekeepers, waiters, cooks, and bartenders, and most of them are people of color. Many of them are already leaders in their workplaces, but some are rank and file workers who have been selected by their union as future leaders. They come from as far away as Alaska, New Jersey, and Texas. When they reach Reno, the union trains them to step out of their comfort zone to speak to total strangers, tell stories about what matters to them personally, listen to different points of view, and then advocate for working people’s best interests.

In the Reno environment, this is not always easy. In certain neighborhoods Trump signs create a hostile environment where some residents are scared to open the door and say what they think. African American canvassers may encounter harsh racism, and have been threatened by gun-toting residents. Latino immigrant canvassers may be treated as if their voices are not as valuable as those of native-born people. When these kinds of problems arise, they are brought up in morning and evening team meetings, where canvassers analyze the problem and recommit to build strength together.

Though I sometimes help with training canvassers, my main role is to coordinate the volunteer effort, where friends and allies of the union knock on doors in a parallel effort to the union’s. For the past two cycles we have partnered with Seed the Vote, a network of progressive groups that sends volunteers to battleground states. This year more than 1000 volunteers will knock on over 100,000 doors in Reno. You can join us and donate to our effort by going to “Donate to Seed the Vote”.

Over the many years that I have spent volunteering with UNITE HERE in Reno, I have witnessed many members come forward and take on increased leadership, both on the campaign and in their workplaces. They go home and treat their workplaces like their political “turf,” using the organizing skills they learned in Reno. As individuals these members have become empowered, and collectively these new leaders have made the union more powerful.

That’s why I keep coming back.

…

There Are Many …

By Tom Yankowski and Trinidad Madrigal

It is time to stand up and take action this year more than ever to stop Maga extremism. Even if you have never engaged in electoral politics before, there are many easily accessible options available for everyone.

1) Door to Door Canvassing

Direct person to person to contact has been shown to be the most effective means of convincing people to vote. There are many grassroots organizing groups, like Swing Left and Seed the Vote, that will help you find the best fit for you. I need specific answers to the issues below before I make a commitment to canvass:

- Is the race winnable for the Democrats? Will it be a close election? Is the race in a swing district that could have national implications?

- Does the candidate have positions that are aligned with my politics?

- Is the location close enough to my home to make it affordable for my budget? Is transportation provided? Do I have family or friends who could provide lodging for me?

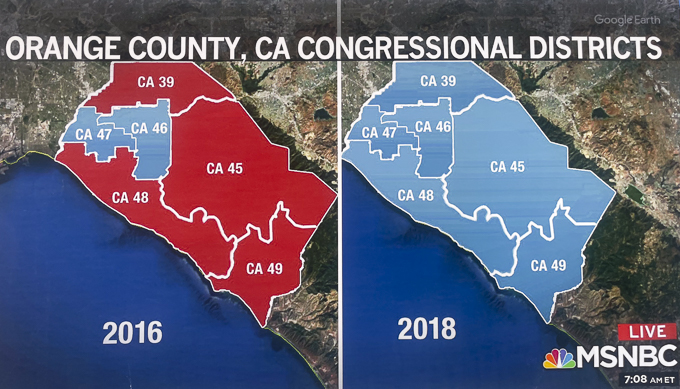

Personally, I will be canvassing for Josh Harder in Congressional District 9, Rudy Salas in Congressional District 22, Derek Tran in Congressional District 45, and Harris/Walz and Senator Jacki Rosen in Nevada.

2) Phone Banking or Broadcast Texting

I actually enjoy phone banking a lot. It takes just one positive interaction with a potential voter to “make my day!” All the campaigns use predictive automatic dialing now so you no longer need to wait endlessly for someone to answer. It can be done virtually on Zoom or in person in some locations. Training with an easy to follow script is always provided beforehand. Volunteers are needed who are multi-lingual…

I also have friends who do not feel comfortable speaking directly to voters. So, they choose to send blast texts to people’s cell phones that can reach thousands of voters. For more information, check out: http://www.mobilize.us/

I try to participate in phone banking 1-2 times a week for a couple of hours each time.

3) Postcard Writing

My wife, Trinidad Madrigal, has been prolific in organizing postcard writing parties with her friends every other week. She enjoys the camaraderie that occurs naturally as people share their stories while writing personalized invites to voters to become engaged. Given all the junk mail we receive, it is amazing that a handwritten postcard will always be perused. Sometimes, the postcard parties are held in people’s homes, and other times, a local brewery or taqueria agrees to host the event. Regardless, food and drink are always involved. If you want to attend or organize such a party, go to: http://www.mobilize.us/

4) Make a Donation

There are so many close races that need your support. We decided to send money to Democratic candidates in close races who need to win in order to maintain control of the Senate and create a firewall just in case. Go to: Swing Left, Seed the Vote

The bottom line is we all need To Do Something! Just think how we will all feel when we wake up on November 6th!

In Solidarity

…