Knocking The Doors #1: Working in CA45th CD

By Peter Olney

Today the Stansbury Forum’s co-editor Peter Olney pens a reflection on door knocking for our future.

Many friends, family and comrades are heading to election work in battleground states where the Presidential election will likely be won or lost. As it was in 2020, the difference between winning or losing will be by a few thousand votes!

I was in Maricopa County, Arizona in 2020 knocking on doors for Joe Biden in 95-100 degrees. He won Maricopa, and so goes Arizona. and so went the Presidential election.

This year, as in the midterms of 2022, I am headed to Orange County, California – the OC – where we have the chance to pick up two House seats: CD 45 and 40. Because Katie Porter (D) (CA) vacated her seat to run for Senate, now we need to defend that seat (CD 47) as well. My principal focus will be on the 45th CD, a seat presently held by MAGA partisan Michelle Steel.

In 2022 we were able to motivate a substantial number of members of my union, the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU) to work on the campaign of her opponent Jay Chen. Steel caught our attention and our ire because she sponsored legislation to put the ILWU and other maritime unions under the Railway Labor Act. She did this during our negotiations for a new contract signaling that union strength should be handcuffed in the “national interest”.

We lost by 6% in 2022 in a district that Biden carried in 2020 by 6%. This time we have new energy at the top of the ticket and a Vietnamese American lawyer and small businessman named Derek Tran as a candidate. This district, which feathers its way down from southern LA County east of the beaches, west of Anaheim and Santa Ana, is the home to the largest concentration of Vietnamese outside of Vietnam.

In November of 2023 and July of 2024 the ILWU sponsored day long trainings on door knocking and direct contact for our members. Now those volunteers will be deployed to the OC as part of flipping the House of Representatives!

One of our retired longshore members was kind and committed enough to provide Christina Perez and I an apartment in the City of Signal Hill. This is a “short” LA commute to campaign HQ in Placentia and Westminster in the OC.. Signal Hill is a fascinating place. As its name suggests it is on a hill completely surrounded by the City of Long Beach. There are a little over 10,000 residents and there are still active oil derricks pumping black crude. The derricks are surrounded by residential neighborhoods, and some of the luxury housing would put Beverly Hills to shame. Oil was discovered here in 1921 and the City was incorporated separately from Long Beach to avoid pesky and bothersome corporate regulation. (For a modern day riff on this idea read “A Libertarian Fantasy in the Tropics” on the Stansbury Forum.)

LA never disappoints. On Labor Day there was a big union/labor march in the harbor with contingents of over a thousand workers from the Carpenters and Laborers unions, both Latino immigrant powerhouses, and smaller yer impressive contingents from the ILWU and Teamsters.

Here is the class and demographic diagnostic. The next day, the LA Times published a photo of SAG AFTRA members marching with a caption and no story. The Spanish language paper La Opinion, a subsidiary of the Times published a giant front page photo of the Laborers’ contingent with a headline: “Fuerza Sindical”. Inside there were three pages of photos and story. Can we guess the demographic targets of the two papers?

The dynamism of LA labor captivates me and of course this is the 2nd largest Metro region in the country and it is an economic and political power house. How ironic that the Governor, the Speaker Emerita, a first class Machiavellian pol, and last but not least, the Presidential nominee, all hail from the small City of 800,00 and 49 square miles by the bay: San Francisco!

We have already scheduled a phone bank for our ILWU retirees to call ILWU members in the OC. (For how it worked in 2022: The Union Difference Behind the Orange Curtain – Working the Mid-terms in Little Saigon.) Two Saturday mobilizations are scheduled for the Tran campaign.The work begins in the midst of a brutal heat wave. Drink lots of liquids, brave the freeways and let’s bring home a victory in November, 2024

…

A Libertarian Fantasy in the Tropics

By Bruce Nissen

Do you find that right-wing proposals to shred our country’s social safety net to pieces and to unburden giant corporations from regulations that protect the environment, worker’s rights, health and safety, and so forth, to be scary? If so, you should look at experiments being tried in Honduras — experiments that make anything being tried here look like half-hearted amateurish measures.

In early January 2024 I joined a delegation of U.S. and Canadian citizens on a nine-day trip to Honduras that was sponsored by the Cross Border Network and supported by other groups that were also members of the Honduras Solidarity Network (also a sponsor). The purpose of the tour was to learn about the effects that our multinational corporations and governments were having on this country, which is the poorest of all the Central American countries.

I learned a lot about Honduras and the perilous existence of many of its residents, be they laid off and injured workers in a local “maquiladora,” racial minorities, trade union leaders (the country recently earned the dubious distinction of having the highest percentage of its union leaders murdered), and in general a country traumatized by a 2009 coup by the military. But nothing I saw or heard left as lasting an impression as something I had never heard of before: special economic zones known as ZEDES (Zones for Employment and Economic Development) that are designed to bypass or evade almost any form of democratic or governmental control over the behavior of those investing in them. We visited and saw up close the country’s most advanced ZEDE, named Prὀspera, on Roatan, a Honduran island off the north coast.

WHAT IS A ZEDE?

How a ZEDE is defined seems to depend a lot on who is doing the defining. Fans of ZEDES describe them as being massive job creators and prosperity generators due to their cutting unnecessary and job-killing government regulations. Detractors tend to define them as the hyper-capitalist embodiment of right-wing fantasies that empower wealthy owners to evade taxes, mistreat workers, and despoil the environment.

The Prὀspera ZEDE is the country’s most ambitious of the three chartered under the previous government. It has the following features:

- While it remains subject to Honduras’s constitution and criminal code, for non-criminal legal matters the ZEDE has its own civil law and regulatory structure.

- The ZEDE civil disputes are handled by an extremely flexible arbitration structure designed to enforce the laws of whatever country a ZEDE business chooses to place itself under (in other words, it could be enforcing the labor laws of Slovakia or any other country from a list of permissible countries to suit the self-choice of any ZEDE enterprise).

- The administrative governance of the ZEDE is handled by a Technical Secretary (TS) who is responsible to and is overseen by a primary governing body known as the Council of Trustees (see below).

- Honduras Prὀspera, Inc. is a private company that owns the ZEDE. It sits on Prὀspera’s Council of Trustees (aka “The Council”) and has veto power over it. The Council is composed of nine individuals, five elected and four appointed by Honduras Próspera Inc. (Those “elected” are chosen by a complicated process that gives landowners more votes depending on the size of their land plot.) Decisions to change any of these arrangements must have a 2/3 majority, or 6 of the 9. (This means that Honduras Prὀspera Inc. holds a veto over any changes.) The Council is the primary governing body; it has a private police force and its own tax system, with extremely low tax rates.

- A non-elected Committee for the Adoption of Best Practices (CAMP) oversees the Council and has the power to approve all internal regulations and to provide policy guidance. It was appointed by the corrupt Honduran government that initially pushed through the ZEDE law (and whose president at the time, Juan Orlando Hernandez, has subsequently been found guilty of narcotrafficking and was sentenced to 45 years in a U.S. jail in June 2024). Nine of CAMP’s members are from the U.S.; only four come from Honduras. CAMP fills its own vacancies, ensuring no political influences can change its orientation or trajectory.

- All basic services that a government normally provides or regulates, such as water, electricity, education, healthcare, etc. are provided by private entities that contract with the ZEDE Council to provide them.

Looking at the above bullet points, it should be obvious that any normal “government” with governmental powers is basically absent in Prὀspera. Virtually everything is privatized. Anything a government would typically do is to be provided through a private contract either between private citizens and private companies or between a “private government” controlled by a for-profit company based in the U.S. (Honduras Prὀspera Inc.).

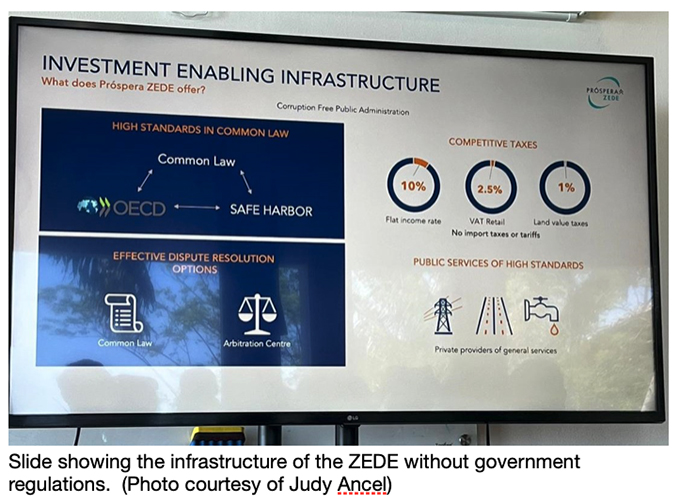

The income tax is nominally 10% but since only 10% of business income is taxed, the effective business income tax rate is 1%. Tax avoidance is a major incentive to invest in Prὀspera. Matters of justice are also addressed through contracts and a private arbitration dispute resolution system. There is no room for any kind of welfare measures of a public nature.

In other words, the Prὀspera ZEDE aims to be the embodiment of an economic libertarian’s dream: almost total absence of government and taxes, with all relationships between people and people-created organizations to be governed only by signed contracts. Market relations and enforceable contracts constitute the entirety of economic interactions. Any kind of governmental intervention to regulate the behavior of private corporations are to be eliminated or at least reduced to the maximum extent possible.

The allergy to government regulation even extends to the ZEDE’s currency: the official currency of Prὀspera is the cryptocurrency Bitcoin. Bitcoin is not issued by any government and theoretically is not subject to any regulation by any government. (This combination of Bitcoin currency, virtually non-existent regulation, and virtually no taxes would seem to make Prὀspera a perfect candidate for money laundering and other illegal financial activities.)

HOW DID ZEDES COME ABOUT?

ZEDES are a product of a military coup in 2009. In 2006 Manuel Zelaya became president following a November 2005 election. Although he came from the landed aristocracy, Zelaya increasingly moved left after his election, increasing the minimum wage by 80%, reducing bank interest rates, providing free electricity to the very poorest residents, and shifting the country’s foreign policy toward allying all Latin American countries into a common block to escape U.S. domination as well as forming friendships with Cuba’s Raul Castro and Venezuela’s Hugo Chavez. During his administration poverty declined by 10% in two years.

The Honduran elite families that owned much of the country’s land and wealth found Zelaya’s policies to be intolerable, as did the military and apparently U.S. policymakers. A military coup in June 2009 deposed Zelaya and deported him to Costa Rica. The U.S. government did not insist that he be returned to power. Instead, the U.S. supported new elections proposed by coup-leaders, and the consequent conservative/right-wing governments that were installed through widely criticized and rigged “elections” brought about the country’s ZEDE law. Porfirio Lobo Sosa, president from 2010-2014 attempted an initial ZEDE law, but it was overturned by the country’s Supreme Court as unconstitutional and a violation of Honduras’s sovereignty. A majority of the Supreme Court justices were then dismissed, and a new more pliant Supreme Court approved a second slightly amended version which was implemented under the rule of Juan Orlando Hernandez (generally known as JOH – pronounced like “hoe”), Lobo’s conservative/right-wing successor who ruled from 2014 to 2022. (As alluded to previously, JOH was convicted in the U.S. of narcotrafficking and weapons-related charges, along with Lobo’s son Fabio, JOH’s brother Tony, and JOH himself but that is a side-story to this brief history of the genesis of ZEDEs.)

After JOH’s National Party lost the 2021 Presidential elections to Xiomara Castro, wife of ousted former president Manuel Zelaya, her new government passed legislation abolishing the ZEDE law and attempted to dismantle the three existing ZEDES. This attempt to get rid of Prὀspera and other ZEDEs is being resisted, as will be related in a later section.

WE VISIT THE PROSPERA ZEDE IN JANUARY 2024

The leaders of our delegation had arranged for us to visit Prὀspera to see for ourselves what a ZEDE actually looks like. Prὀspera carefully guards who is allowed in (the public is not necessarily allowed to enter), so we had to fill out long and detailed questionnaires about our occupations, purpose in visiting, addresses, etc. before we were allowed in. By filling out these forms, we became “e-residents” of Prὀspera – to this day I receive communiques asking me to report the income I made in the last year within the ZEDE (which for me is of course nothing) for purposes of accounting and registration.

My first impression was not all that favorable. There is a very rough dirt road leading to the ZEDE; it certainly did not give the sense that a lot of commerce of a physical variety was entering or leaving the place. I know that a semi-finished resort is being constructed in Prὀspera and that residential and commercial construction is planned, but I didn’t see much of this. On the other hand, it is located on the northern coast of Honduras and has breathtakingly beautiful views of the sea, and for that reason alone could easily be a prime candidate for tourist development.

We got to meet two of the most important people involved in running Prὀspera. Ricardo Gonzalez is the Assistant ZEDE manager. And Jorge Colindres is the Technical Secretary in charge of its overall operations. Both spoke perfect English and were educated in the U.S. They both spoke to us at some length, especially Colindres.

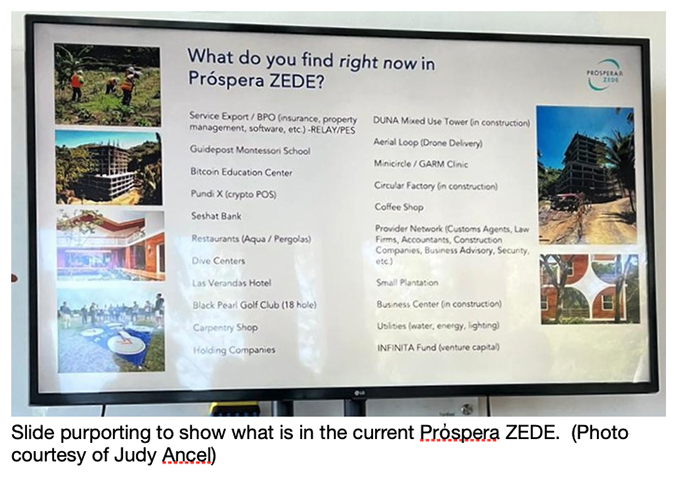

Both Gonzalez and Colindres are fervent believers in ZEDEs and the philosophy underlying them. They claimed that Prὀspera either had already or would soon attract carpentry businesses, export services, private education companies, restaurants, real estate firms, finance tech companies, medical clinics, and much more. Colindres called it a “Hong Kong in Honduras.”

Colindres noted that Honduras Prὀspera Inc. is a private U.S. company that created the ZEDE as a “platform for investment.” And he claimed that those investments would create prosperity for all and lessen or eradicate poverty. He (correctly) noted the widespread corruption in Honduran society and (dubiously) claimed that the ZEDEs would somehow be immune to such corruption. Everything is to be governed by binding contracts that individuals voluntarily sign, and these are enforceable by arbitration proceedings taken to the Prὀspera Arbitration Center (PAC) or else the business-oriented International Centre for Dispute Resolution (ICDR). This he claimed would settle disputes in a clean way that ordinary laws and regulations would not.

When pressed on the need for some form of regulation to prevent harmful “negative externalities” to others, he did concede that some form of controls is necessary and mentioned that according to the ZEDE’s charter ten industries in Prὀspera are not entirely free of oversight. I got five of these down in my notes: banking, healthcare, education, restaurants, and construction. How are these regulated? A company operating in any of these industries can choose its own regulations from those of 36 different countries. Thus, you could have a restaurant operating under the laws and regulations of, say, Estonia, while a restaurant across the street was governed by the laws and regulations of Brazil. It would be up to the owners of each restaurant to decide. Enforcement would be strictly by arbitrators deciding any disputes. Outside of the 10 industries there would be no regulatory control over the behavior of businesses or investors beyond any individual contracts they may sign.

Our delegation peppered Mr. Colindres with skeptical questions about the absence of regulatory control over especially big businesses. The most interesting thing about his answers is that they fell into two categories. The first category was a variant of the “trust me” justification. Since he is the Technical Secretary and hence the chief administrator of Prὀspera, he had the power to see that things were done properly, and he would never allow any violations of human rights or undue power for moneyed interests: we could count on it.

Second, he claimed (oddly enough for someone praising freedom from government) that many of our worries were addressed by Honduran government regulations that do apply to the ZEDEs. For example, he stated that the Honduran minimum wage (currently ranging from $1.94 US to $2.77 US per hour in manufacturing depending on the number of workers) applied to Prὀspera, so workers could not receive egregiously low payment. (He also claimed that Prὀspera’s charter requires payment 10% above the minimum wage.) Finally, he stated that if no other law or regulation applied to a business or industry, the prevailing standard would be “common law” enforced by the arbitrators, so the absence of firm written laws or rules should not be troubling.

A final guarantor of fairness is the fact that businesses operating in Prὀspera have to have insurance, he claimed. Since insurance companies do not like to make big payouts, they will protect worker rights, the environment, and the like, by refusing to insure companies taking shortcuts in these and other areas. (I found this claim to be especially ludicrous given the track record of U.S. medical insurance companies that raise their premium rates if they have to make a big payout, rather than cancelling coverage or pushing a company to reduce risk.)

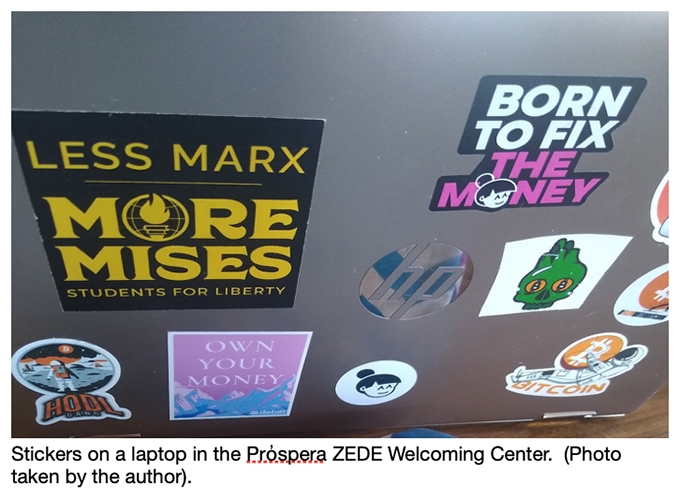

Wandering around the room where we were given the lecture by Colindres, I found some interesting things. One was a money changing machine to convert other currencies into bitcoin and vice versa. (I regret I did not get a picture of this machine.) Also interesting were posters and books for sale that were inside bookcases. For example, here are some stickers photographed from one of the laptop computers sitting around the room:

Note the many stickers boosting bitcoin currency as well as the “Less Marx, More Mises” sticker. Karl Marx is of course well known; the “Mises” refers to Ludwig Von Mises, the libertarian Austrian American thinker who argued that any governmental intervention in the economy would inevitably be for the worse.

The books for sale that were inside wall cabinets were also interesting. I’ll start with two children’s books which are take-offs from well-known children’s books in the U.S.:

Goodnight Bitcoin imitates one of the best-known children’s books of all time: Goodnight Moon. If you Give a Monster a Bitcoin emulates the beloved children’s book If You Give a Mouse a Cookie. I guess it’s never too early to begin inculcating into the mind of a child the individualist libertarian mindset necessary to make a currency free from any government seem plausible.

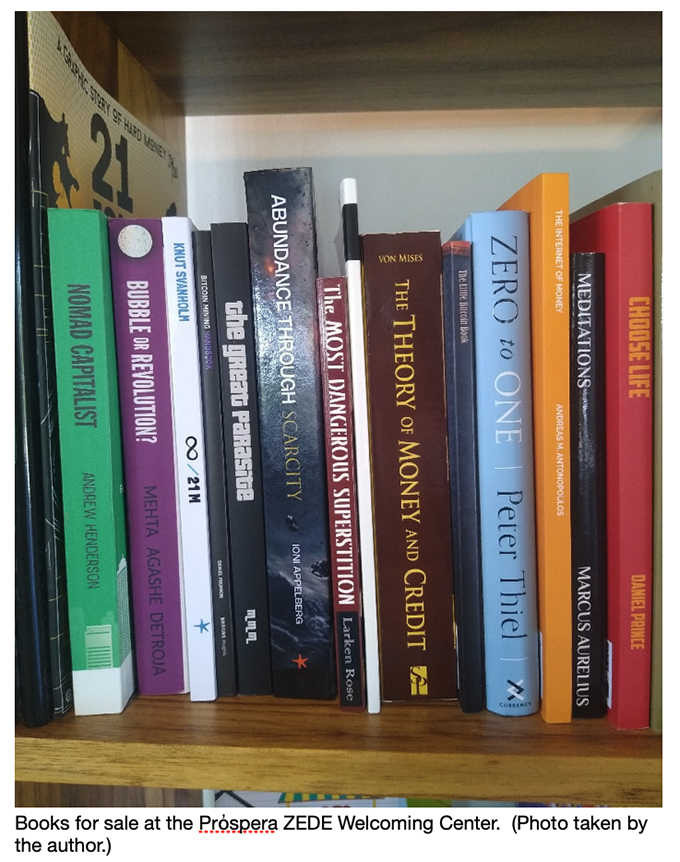

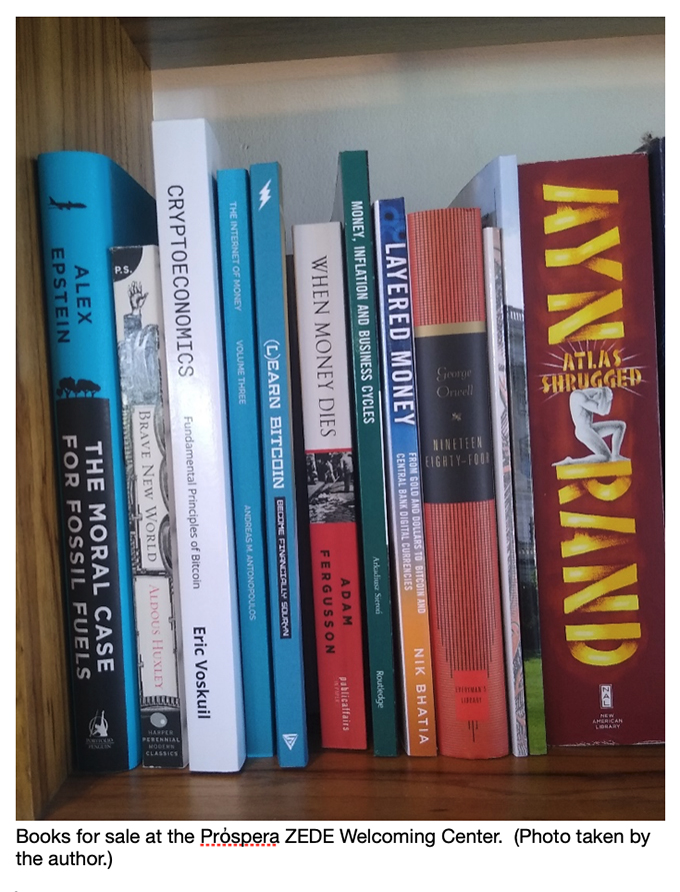

Then we come to the adult books. As you might suspect, they were all right-wing libertarian tracts. Here are a few pictures:

Note especially both the foundational book of this type, Von Mises’ The Theory of Money and Credit and a very recent book by modern billionaire and well-known anti-government crank Peter Thiel, Zero to One.

One more picture gives you the flavor of the books favored by and hawked by the Prὀspera ZEDE:

I had to include this picture because it shows perhaps the most famous individualist/libertarian book of all time: Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged. This book has sold many millions and is still selling briskly 70 years after it was published. I also found the title of the book on the far left to be astounding: making a moral case for maintaining fossil fuels.

Our delegation’s trip into the libertarian paradise came at a time when it was in peril, as it still is. This is the subject of the next section.

NEW GOVERNMENT FOLLOWING A GENUINE ELECTION MOVES TO ELIMINATE ZEDES

As noted previously, a reform government led by former first lady Xiomara Castro took power in January 2022 after a November 2021 election. Castro immediately reversed the trajectory of her conservative predecessors. She stopped a wealthy landowner from evicting indigenous people from land south of the capital, citing indigenous rights. She banned new open pit mining to protect the environment, introduced reforms to the tax system that close tax loopholes for the very richest (these tax reforms have not yet passed Congress), made electricity free to the poorest residents who used small amounts of it by billing the biggest users, and took other measures favoring those less well off.

In May 2022 she presented to the Honduran Congress legislation abolishing the ZEDE law. It passed unanimously, with parties from the left, right, and center all supporting it. This move was immensely popular in the country; mass demonstrations had been held opposing the existence of ZEDEs.

Amnesty International of the Americas lauded Castro’s move because they asserted that ZEDEs threatened the human rights of Honduran residents. But Honduras Prὀspera Inc. immediately filed a charge against Castro’s government with the International Centre for the Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), a business-oriented arbitration mechanism set up by the World Bank to protect foreign investors as an Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) mechanism for cases like this. They demanded $10.8 billion for the estimated loss of expected future profits from the Prὀspera ZEDE. That amount equals approximately two-thirds of Honduras’s annual state budget; it would cripple the country if the plaintiffs should prevail.

Two treaties with the United States commit Honduras to use this ISDS arbitration system to settle disputes with investors: the Dominican /Republic-Central America Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR) and a U.S.-Honduras Bilateral Investment Treaty (BIT). Castro had declared in her campaign that Honduras would withdraw from these two treaties, but the government has not left either CAFTA or BIT to date. She resisted sending a government representative to the arbitration proceedings that were set up to hear the Prὀspera claim before the ICSID. But eventually she was forced to send a lawyer to the proceedings to represent Honduras. This lawyer argued that private companies had to exhaust national legal remedies before coming to the ICSID tribunal, but this argument has not been accepted.

Eighty-five prominent international economists signed a letter in support of Castro’s move to withdraw from the ICSID, stating,

We economists from institutions across the world welcome the decision by the Honduran government to withdraw from the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID). We view the withdrawal as a critical defence of Honduran democracy and an important step toward its sustainable development.

U.S. politicians have weighed in on both sides of the dispute. Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-Massachusetts) and U.S. Representative Lloyd Doggett (D-Texas) rallied over 30 Congressmen to write U.S. Secretary of State Anthony Blinken asking that he intervene on the anti-ZEDE side. U.S. Senators Bill Haggerty (R-Tennessee) and Ben Cardin (D-Maryland) asked Blinken to do the exact opposite.

Legally the case is tangled and murky: Can Castro unilaterally (without congressional authorization) pull out of these treaties? Can the Prὀspera ZEDE lock in its own existence because it signed a 50-year treaty with Singapore while existing Honduran law guarantees protection of such treaties for a decade? While new ZEDEs are clearly illegal since the ZEDE law was rescinded, can existing ZEDEs also be eliminated retroactively? Answers to these questions are ambiguous at the present time.

Even more important, where does the U.S. government stand on the issue? Since the U.S. has almost-complete hegemony over what happens in a small and poor Central American country like Honduras, where it stands is crucially important. The Biden regime has talked out of both sides of its mouth. Former president Biden fulminated against Investor-State Dispute Settlements (ISDSs) and vowed to not include them in any future trade agreements. In contrast, Laura Dogu, the U.S. ambassador to Honduras, has strongly endorsed ZEDEs and Prὀspera in particular. She sharply criticized Xiomara Castro’s abolition of the ZEDE law, stating that such “actions are sending a clear message to companies that they should invest elsewhere, not in Honduras.” The U.S. State Department issued a similar statement, criticizing Honduras for having an uncertain “commitment to investment protections required by international treaties.”

WHAT IS THE LESSON FROM PROSPERA? WHAT CAN WE DO?

Rightwing libertarians around the world are attempting to erode and virtually erase governmental measures that protect both people and the environment from corporate misconduct and unrestrained capitalism. Thus, the most important lesson we can learn from the Prὀspera case is that we must remain vigilant worldwide.

To fight the good fight only domestically is to leave us all more vulnerable on a worldwide scale to a dystopian future of unrestrained selfishness, ever-growing inequality, and the consequent authoritarianism and militarism needed to hold down the subject peoples and to keep them from emigrating to wealthier countries like the U.S. In addition, Honduras and similar countries are laboratories for what might be done domestically in the future. This battle must be fought especially sharply in those areas of the world most lacking in resources needed to fight for and sustain a more humane cooperative and people-oriented society. Places like Honduras.

Here in the United States an urgent need is to demand that the administration not only vow to keep ISDS measures out of all future trade agreements (as the President has pledged to do) but take them out of all existing trade agreements. Fortunately, there is already action being taken by citizen groups and members of Congress to do just that. This move could use our help.

Congressmembers Linda T. Sanchez (D-California) and Lloyd Doggett (D-Texas) have marshalled 47 members of the House of Representatives to sign a letter to Secretary of State Anthony Blinken and U.S. Trade Representative Katherine Tai demanding that ISDS measures be taken out of CAFTA-DR and other such economic and trade agreements. This letter has been endorsed by Public Citizen, AFL-CIO, Greenpeace, Sierra Club, Pride at Work, Unitarian Universalists for a Just Economic Community, Honduras Solidarity Network, Oxfam America, Progressive Democrats of America, and a number of other groups.

We can aid this cause. If your Congressperson in the House has not signed on to this letter, we can pressure them to do so. If they have signed it, we can thank them for doing so and also write to our Senators to demand that they also sign on to this or an identical letter in the Senate. We can also ask the organizations we know and are affiliated with to endorse this letter, get their members to publicize it and contact their congresspersons, and so on.

Here are the materials you need to take action:

- First, you can go to the webpage that explains the issue and contains the letter: https://lindasanchez.house.gov/media-center/press-releases/sanchez-doggett-call-biden-administration-reform-cafta-dr-trade

- Second, you can download, circulate and publicize the letter itself, which is at this link: https://lindasanchez.house.gov/sites/evo-subsites/lindasanchez.house.gov/files/evo-media-document/ISDS%20Letter.pdf

- Finally, publicize all of this on social media!

I’m enclosing the entire letter below (minus the 47 Congressional signatories), just for those who lack online access and are only able to read from paper copies.

March 21, 2024

The Honorable Anthony Blinken The Honorable Katherine Tai

Secretary of State U.S. Trade Representative

Department of State Office of the U.S. Trade Representative

2201 C Street N.W. 600 17th Street N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20520 Washington, D.C. 20508

Dear Secretary Blinken and Ambassador Tai,

We commend the administration’s commitment to a “worker-centered” trade agenda that uplifts people in the United States and around the world and helps promote our humanitarian and foreign policy goals. We particularly appreciate President Biden’s opposition to including investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) mechanisms in trade and investment agreements, which enable foreign companies to sue the U.S. and our trading partners through international arbitration.

On a bipartisan basis, Congress drastically reduced ISDS liability from the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) because ISDS incentivizes offshoring, fuels a global race to the bottom for worker and environmental protections, and undermines the sovereignty of democratic governments. However, the U.S. has more than 50 existing trade and investment agreements on the books, most containing ISDS, including the U.S.-Central America Dominican Republic Agreement (CAFTA-DR) which entered into force in 2006. We urge you to offer CAFTA-DR governments the opportunity to work with the U.S. government to remove CAFTA-DR’s ISDS mechanism.

While there is no evidence that ISDS significantly promotes foreign direct investment, there is ample evidence that the abuse of the ISDS process harmed the Central America and Caribbean region. Multinational corporations have used ISDS to demand compensation for policies instituted by governments in CAFTA countries, undermining their democratic sovereignty and, often, harming the public good. For example, foreign companies have targeted labor rights, environmental protection, and public health policies.This ultimately works to counteract U.S. government assistance intended to address the root causes of migration from the region.

For certain Central American and Caribbean countries, even a single ISDS award (with some claims in the hundreds of millions or billions of dollars) could destabilize their economy, as limited fiscal revenues are diverted from critical domestic priorities to cover legal defense expenses, tribunal costs and damages. According to public sources, taxpayers in CAFTA-DR countries paid at least $58.9 million to foreign corporations in ISDS awards, with at least $14.5 billionin pending ISDS claims.Notably, the lack oftransparency in ISDS arbitration makes it impossible to know the full extent of ISDS liability. There are also concerns regarding the fairness of ISDS proceedings as ISDS arbitrators can appear as counsel before tribunals composed of arbitrators with whom they previously served in different ISDS proceedings.

Accordingly, we are eager to work with you to remove ISDS liability from CAFTA-DR and all other trade or investment agreements with countries in Central America and the Caribbean. This would send a powerful signal that the U.S. government is committed to a new model of partnership in the region — a model that uplifts and protects democracy, rule of law, human rights, and the environment. We look forward to working alongside you to bring the CAFTA-DR more into alignment with the current trade agenda and prevent harmful corporate overreach in emerging economies.

#

Special thanks to Judy Ancel and Karen Spring for judicious edits and corrections on earlier versions of this article.

###

The Next Voice You Hear…

By Gary Phillips

A well-known crime writer of my acquaintance had recently self-produced several of his earlier novels from decades ago as audiobooks. There are various outlets where writers and small press publishers can find voice talent to narrate a book. ACX, essentially a subsidiary of Audible, is one of those venues, with an interactive online presence. There under its FAQs the potential customer is informed, “You can pay by the finished hour, arrange to split royalties, or opt for a hybrid,” if a narrator, or narrators, are interested in working with you on your book. Not for nothing, as Audible will inform you, it is “the United States’ largest audiobook producer and retailer.” The entity was bought by Amazon more than fifteen years ago.

Meanwhile back to this this old school writer. He hasn’t used humans to narrate his older work, he used an AI outfit – that presumably charged less than real life voice talent. Not only does the raw recording have to be done, but editing and other polishing is done to make an audiobook. There are now quite a number of companies wherein the machine, with some human or another doing the fine-tuning, transforms your prose into a simulacrum’s version of dulcet tones. Narrating text is hard work. I’ve had the opportunity to voice a few of my short stories as well as pay out of pocket to additional human beings to self-produce a collection of my short stories.

No matter the level of experience, humans flub lines, screw up pronunciation, or have to re-record entire passages for whatever failing of flesh and/or technology. That’s why the rate, which varies from who is providing the voice talent, is per finished hour. But advances in the development of synthetic voice production are such that nuance, emphases chosen, the cadence the talent brings to the table, sometimes with the intercession of an audiobook director, it’s becoming much harder to distinguish the robot from the mere mortal.

A good number of folks who narrate audiobooks also work in other areas where ones’ voice is the instrument of entertainment and information – and the source of a paycheck. In addition to audiobooks, voice actors are employed in radio and TV commercials, industrial films, documentaries and the mammoth industry of video games. SAG-AFTRA’s video game workers went on strike on July 26. This after eighteen previous months of frustrating negotiations. The workers held a picket at Warner Bros. Games in Burbank, on August 1. At the heart of the strike was the “existential threat” of generative AI.

As SAG-AFTRA has posted to the membership and the public on its site, “Video game performers are fighting for our livelihoods, and we’re facing a pivotal moment: Employers at some of the largest video game companies want to use A.I. to replace us using our own performances without compensation, transparency or consent.”

Can there really be guardrails put in place regarding the ethical use of generative AI? You don’t have to be an economist, Keynesian or otherwise, to keep in mind those who control the means of pop culture production have and always will be concerned with profits and loss. How to increase the former and decrease the latter. If the electricity doesn’t go out, AI doesn’t get tired, doesn’t show up late and can’t demand fair wages or withhold its labor.

An allied union the Animation Guild, held another rally, “Stand with Animators” on August 10 also in Burbank. The rally was a precursor to the Guild’s negotiations with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP) when the master agreement expired on August 17. From the animators’ point of view, they seek to prevent generative AI being used to replace human art with machine art.

Yet as more out-sourcing, consolidation and downsizing continues, it’s the gig economy manifesting itself in what we collectively call Hollywood. Piece work as opposed to steady work. Not only voice actors, but line producers, editors and on and on aren’t working in their chosen careers but are now teaching middle school, becoming line cooks or have moved out of state to be able to afford housing, looking to start over in some other field.

“This is your opportunity to experience expressive narration, ambient sounds, Foley [sound] effects, and background music tailored to your narrative.” This was part of the come-on I received recently unsolicited in an email. This particular enterprise as part of the sell said I could send them a brief sampling of my writing and they’d produced a five-minute AI version with all the bells and whistles so outlined. I’m not tempted to bite their holographic apple, at least for now.

Reluctantly I’ll admit there’ll be temptation to hear a sample of my work once I get the next generation of this email. The one informing me an entity can deliver full cast recordings, a la radio dramas, incorporating the above-mentioned flourishes as well as multiple voices. Or so the seductive stentorian AI voice will tell me when I click on the link.

###

The Black Freedom Movement and Tradeswomen History

By Molly Martin

I want to take us back in time and imagine a world, a culture, in which job categories were firmly divided between MEN and WOMEN. Women were restricted to pink collar jobs that paid too little to raise a family on or even to live without a man’s support. Even doing the same jobs, women were legally paid less than men. Married women were not allowed to work outside the home. Single women who found jobs as teachers or secretaries were fired as soon as they married. Black people were only allowed to work as laborers or house cleaners.

This was the world we fought to change.

Tradeswomen who have jobs today must thank Black workers who began the fight for jobs and justice.

The Black Freedom Movement has advocated for workplace equity since the end of the Civil War.

The movement gained power during and after WWII. A. Philip Randolph headed the sleeping car porters union, the leading Black trade union in the US. In 1940 he threatened to march on Washington with ten thousand demonstrators if the government did not act to end job discrimination in federal war contracts. FDR capitulated and signed executive order 8802, the first presidential order to benefit Blacks since reconstruction. It outlawed discrimination by companies and unions engaged in war work on government contracts. This executive order marked the start of affirmative action.

The fight to desegregate the workforce continued.

In the early 1960s in the San Francisco Bay Area, protesters organized successful picket campaigns against businesses that refused to hire Blacks, including the Palace hotel, car dealerships and Mel’s Drive-In. Many of the protesters were white students at UC Berkeley.

In August 1963, the march on Washington brought 200,000 people to the capitol to protest racial discrimination and show support for civil rights legislation. The civil rights act of 1964, signed into law by President Johnson, is the legal structure that women and POC have used to put nondiscrimination into practice.

But change did not come quickly or easily.

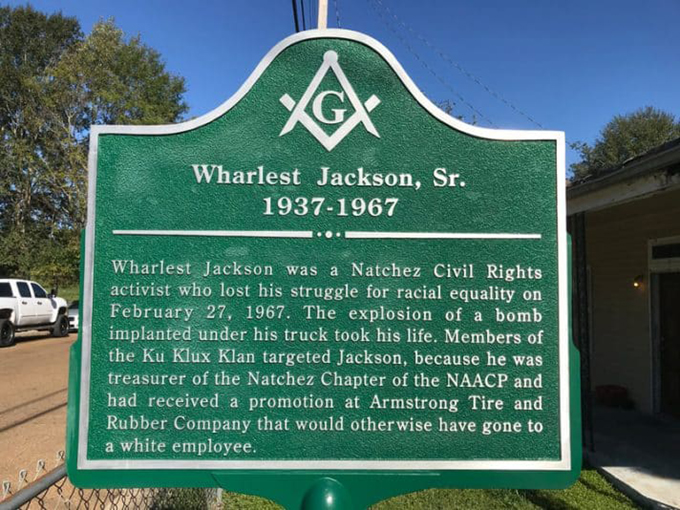

Black workers at a tire plant in Natchez Mississippi were organizing to desegregate jobs. The CIO, Congress of Industrial Organizations, supported them in this fight. In 1967, three years after the civil rights act became law, a Black man, Wharlest Jackson, who had won a promotion to a previously “white” job in the tire plant, was murdered by the KKK. They blew up his truck as he was driving home from work. No one was ever arrested or prosecuted for this crime.

Wharlest Jackson was the father of five. His wife, Exerlina, was among those arrested for peacefully insisting on equal treatment during a boycott of the town of Natchez’s white businesses. She was sent to Parchman penitentiary.

Jackson was just one of many who died for our right to be treated equally at work.

Tradeswomen are part of the feminist, civil rights and union movements. We continue to seek allies because we are few.

Discrimination has not ended, but, because of decades of organizing, our work lives have improved. We owe much to the Black workers who sought equity in employment for decades before us.

…

Two Bay Area natives honor their ancestors with public art

By Lincoln Cushing

Recently a Bay Area artist colleague of mine presented a powerful public sculpture honoring her mother. At Berkeley’s Juneteenth celebration Mildred Howard unveiled “Delivered, Mable’s Promissory Note” near the Ashby BART station. The large metal sculpture, based on West African jewelry currency, is a shout-out to Mildred’s mother who fought – and won – to underground the light rail line that would have otherwise disrupted her predominantly Black neighborhood in the 1960s.

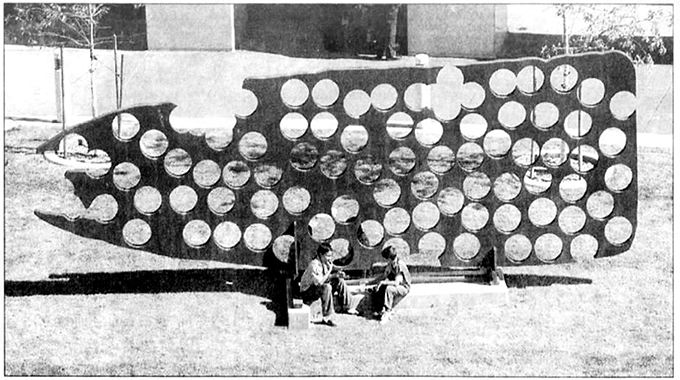

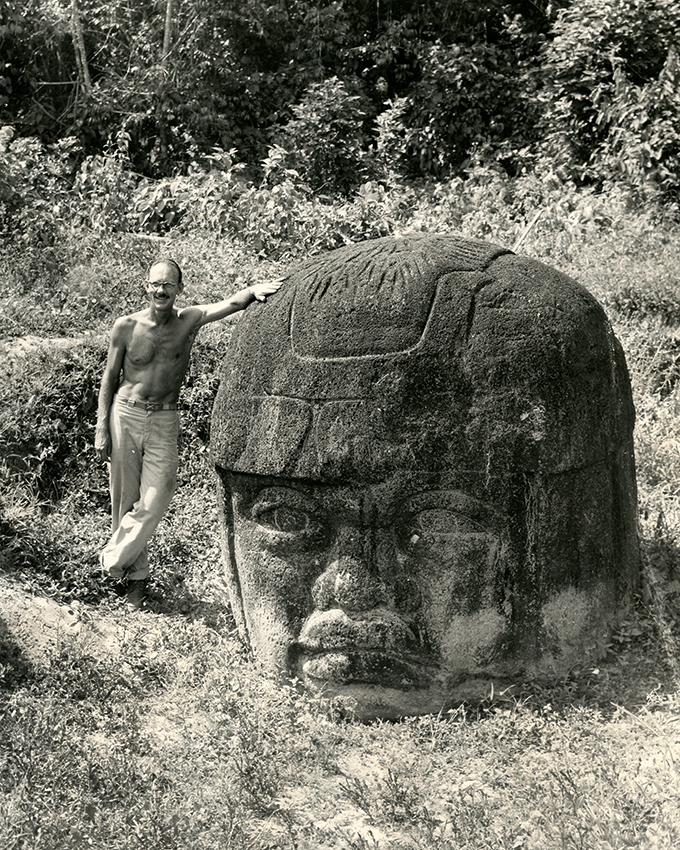

Another Bay Area artist did something very much like that in 1996 when Berkeley-born Michael Heizer (1944-) presented a commissioned metal sculpture at the Bruce R. Thompson Federal Courthouse in Reno, Nevada. “Perforated Object #27” was inspired by a Shoshoni artifact created over 1,500 years ago, carved from the horn of a bighorn sheep and perforated by 90 drilled holes. It was discovered in 1936 as part of an excavation led by Michael’s father, U.C. Berkeley anthropology professor Robert F. Heizer (1915-1979) at Humboldt Cave, 100 miles northeast of Reno. Michael’s massive sculpture, like Mildred’s, is a dramatic physical enlargement – 27-foot-long “Object” is 450 times bigger than the 4½” long original. Positive and negative space is a common element in Michael’s works, so the sculpture is accompanied by a rough line of 90 steel rings. Robert was my maternal uncle, who like Mildred’s father, had worked in the WWII shipyards.

Michael’s work did not always formally make historical references. “Platform,” a 30-ton pile of rusty steel commissioned by the Oakland Museum in 1980 and installed at Estuary Park, was purely abstract. Yet even that was described by art critic Allan Temko as “avowedly symbolic, or mythic, recalling the Mayan ceremonial platforms of Chichen Itza, which he saw as a child with his late father.”

Michael began formally connecting his earth work sculptures with indigenous iconography in 1982 with a commission at Buffalo Rock State Park in Illinois. “Effigy Tumili” deliberately evoked Mississippian Culture with mounds and embankments representing a catfish, a frog, a snapping turtle, a water-strider and a snake. He later began producing sculptures of oversized artifacts in 1989 with a series of immense concrete copies of prehistoric hand tools; in 1993, foreshadowing Mildred’s “Delivered,” he made “Small Pendant.”

Anthropology has seen a severe and legitimate reckoning in the past few years. Robert Heizer wasn’t an activist, yet after beginning as a glorified grave robber – as did most of his colleagues – he was inspired by the spirited demands of the Free Speech Movement and evolved to push the boundaries of his academic field in the right direction. Critic Tony Platt’s recent book The Scandal at Cal gives this nod using a word very much in the news today: “Heizer was among the earliest academics to use the g-word when describing the state’s efforts to exterminate Native peoples in the nineteenth century. ‘No one troubled to name what was happening in California a hundred years ago genocide,” he wrote with Theodora Kroeber in 1968.’”

When Michael articulated his goals for his 1982 “Effigy,” he expressed the same respect with the same term: “The Native American tradition of mound building absolutely pervades the whole place, mystically and historically in every sense. Those mounds are part of a global, human dialogue of art, and I thought it would be worthwhile to reactivate that dialogue [ … ]. It’s an untapped source of information and thematic material, it is a beautiful tradition, and it’s fully neglected. And it’s from a group of people who were genocided. So, in a lot of ways, the Effigy Tumuli is a political and social comment.”

Michael’s life’s work, the massive southern Nevada desert project “City,” has been criticized for lack of environmental and cultural sensitivity. But he’s a major artist who understands that all art, and culture, draws from the deep well of our ancestors.

Thank you, Mildred and Michael, for your work.

…

Olney Odyssey #21 LACAPS

By Peter Olney

In Olney Odyssey #20 I arrived in Los Angeles and found employment with the Los Angeles Coalition Against Plant Shutdowns, LACAPS, a labor/community coalition that really enabled me to enter the LA scene in very rapid fashion and gave me access to a lot of wonderful people, some of whom have become lifelong friends.

The offices of LACAPS were at the First Unitarian Universalist Church of Los Angeles off of Vermont, at Eighth Street. A very famous institution, this church. It previously had a pastor named Stephen Fritchman who during the Red Scare was a friend, confidant and supporter of many of the people being persecuted by Joseph McCarthy. Fritchman was subpoenaed twice to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee, also known as HUAC, a body that eventually was closed down because of its abuses. My office was there, and this was nice for me because it was going home: I was raised in the Unitarian Universalist Church.

In 1981 General Motors worker Kathy Seal launched LACAPS alongside Al Belmontes and Gary Peoples from UAW Local 216 in South Gate California where their GM Assembly plant was under threat of closure. LACAPS was strengthened by a very successful conference in 1982 on factory shutdowns and runaways entitled: Western International Conference on Economic Dislocation. The principal conference organizer was an Episcopal Priest named Dick Gillett who became a family friend and later officiated at my marriage to Christina Perez in 1985. Goetz Wolff was his right hand man and served as the director of the conference.

The organizers of the 1982 conference constituted themselves as the Board of Directors of LACAPS. Kathy Seal was the staff organizer of LACAPS, and I was hired to work with her.

Similar coalitions of impacted labor unions and their community allies were being established all over the country to combat massive economic dislocation in basic manufacturing. The Bay Area Plant Closures project was the Northern California sister project to LACAPS.

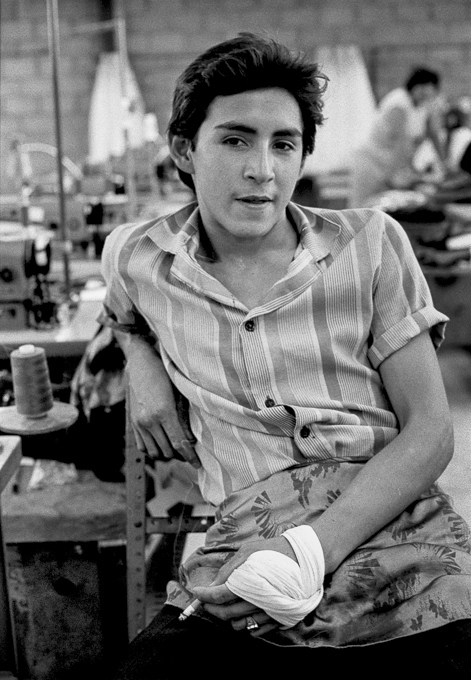

One of the partners in this Coalition Against Plant Shutdowns was the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU). Many people don’t know this, but LA was always the second center of garment production in the country after New York, and at the time I moved to Los Angeles there were about 100,000 garment workers in Los Angeles County. The union represented probably five or six thousand of them.

One of my first assignments was to go out and provide support for a strike at a company called Southern California Davis Pleating. It was a shop, as its name suggests, that supplied pleating services for fashion designers, interior designers, home dressmakers, fashion colleges, film companies, advertising, theatrical costumiers, and milliners.

I went out to their picket lines on 10th Street just east of downtown. And I vividly remember this picket line with about 150 women, mostly Mexican, carrying the red and black flags, “Banderas Rojinegras,” which in Mexico symbolize a strike. Red is the color of the international proletariat and black is the color honoring the martyrs in the fight for the eight hour day. I had never seen such banners before and I think they are a particular Mexican and Latin American tradition. This was another of many moments where I realized “I’m not in Boston anymore.”

The Davis Pleating strike lasted for seven months. It was triggered when the company demanded that its workers take a 20% wage cut, yield four paid holidays and two weeks’ vacation time per year, and give up cost-of-living raises and some medical benefits, as well as give up seniority rights and the right to reject overtime work. Ultimately the strike put the company out of business.

I remember going to the headquarters of the International Ladies Garment Workers in Los Angeles, which was on South Grand, and meeting the organizing director of the union, an amazing man named Miguel Machuca. He became a real mentor to me in terms of organizing and particularly in organizing Latino immigrants. He was from the State of Jalisco, Mexico. Miguel had crossed the border with the clothes on his back and had become a garment worker and a skilled cutter. From that position he successfully organized California Swimwear Co. in 1972. In 1982, one year before my arrival, he became the Western States organizing director of the union.

There were approximately eight to ten people working in the organizing department, all bilingual, and all Spanish speakers. In fact, the ILGWU was the first union in Los Angeles tohave a Latino organizing director and a staff that all spoke Spanish, many of whom were of Mexican descent. So, the ILGWU at that moment in history, in the early- to mid-Eighties played kind of a vanguard role in the labor movement because it was a union with the capacity to organize Spanish-speaking workers. Many other unions did not.

I had graduated from the University of Massachusetts in Boston with a degree in Spanish and had organized in many workplaces in the greater Boston area where the workforce was Puerto Rican or Dominican, or Cuban. Even though I had learned Spanish pretty well, I never really mastered it until I came to Los Angeles. Spanish became the language of all the work I did in Southern California.

The ILGWU was a very important seminal force for the revitalization of LA labor.

It’s interesting because one of the unions now that plays a major role in organizing is the Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees Union (HERE). They have approximately 20,000 members in LA County. Their members are largely Spanish speaking. But at the time I came to LA, the head of that union did not speak Spanish and refused to allow translation at his membership meetings. This was mainly because he felt threatened by the possibility that these workers would know what was going on and would get rid of him. And that eventually happened. A very skilled organizer named Maria Elena Durazo, who had trained at the ILGWU with Machuca, ran against him and beat him later on in the 1980s. She’s now a State Senator in the California Legislature.

Working with the ILGWU was a wonderful experience. Miguel Machuca was a brilliant tactician. I remember after I won a union representation election, I went to him chagrined because I had mistakenly inflated the earnings of the owner of the newly organized garment shop. The inflated numbers were printed on leaflets distributed to the work force in advance of the election. I found out subsequently that there were two garment shop owners with the same name, and that I had gotten the wrong one. I was worried that the results of the election would be nullified by my false propaganda slandering the boss. Miguel assured me that that was not a danger and that, “Peter, look at the positive. You just acquired a new skill!!”

I also got to know the other organizers, some of whom have remained friends to this day. All of them had their own talents: translation, leading chants on the bullhorn, singing, providing logistical support for a strike kitchen, and all the various detailed tasks necessary to win a labor struggle. ILGWU Presente!

Through working at the LA Coalition Against Plant Shutdowns I got the opportunity to take my first trip to Mexico. I went as part of a delegation of Southern California unionists invited to Mexico to participate in a conference at the Centro de Estudios Económicos y Sociales del Tercer Mundo (Center for Economic and Social Studies of the Third World), founded by Luis Echevarria, the President of Mexico in the early Seventies. The Center was in the hills outside of Mexico City. I was invited to go to this conference to represent LACAPS.

I went to Mexico City with two very historic figures in Los Angeles’s labor movement – Bert Corona and Soledad “Chole” Alatorre.

They were the leaders of Hermandad Mexicana, the Mexican Brotherhood, a fabled organization that organized and represented Mexican workers. So I was on a delegation with them, and that was a real experience to meet these legendary labor organizers and community leaders.

Corona had gone to USC from his hometown of San Antonio, Texas, in 1936, on a basketball scholarship. He ended up working in a warehouse represented by the International Longshore and Warehouse Union Local 26 and later became the first Latino President of the local, which at the time had 12,000 members. Today there’s a San Fernando Valley middle school named in his honor.

Alatorre was born in Mexico and, after emigrating, went to work in the garment industry of Los Angeles, where she became a prominent organizer.

Later on Alatorre, Corona and other left wing labor activists and Mexican émigrés founded CASA (Centro de Accion Social Autonomo), which played a key role in fostering Latino labor organization nationwide. CASA’s alumni/ae association includes many of the best and brightest in the California and Chicago labor movements.

One moment I’ll never forget in that visit to the Echevarria Center was when we were walking on the cobblestones at the Centro. Luisa Gratz, who remains to this day the president of ILWU Local 26, was wearing stiletto heels. As we walked across the cobblestones she got stuck. She couldn’t move. So, I gallantly swept her up from out of the cobblestones.

At the conference I met two people – a man named Jorge Carrillo and a woman named Norma Iglesias. They were a couple, and they were university-based researchers at the University of Baja California Norte, based in Tijuana.

They became friends to me, and together we hatched the idea of publishing a cross- border newsletter called Puente, The Bridge, that would link the struggles of workers in Southern California with the struggles of workers in Northern Mexico – given that there were a lot of commonalities in terms of the workforce, language, culture, and corporations that were crossing the border and locating production in this “maquiladora” region.

A maquiladora is a factory in Mexico operated by a foreign company. Maquiladoras export the majority of the goods produced in Mexico to the USA. Through this program, a foreign company may import raw materials, components for assembly, and equipment necessary to produce its goods without paying the 16% value added tax on these imported materials and equipment. US corporations were taking advantage of these tax breaks from the Mexican government to produce goods to be imported into the United States. So, we established this newsletter and published several issues of it.

One thing I remember vividly – and I have a picture of this man speaking – is going to a meeting in Tijuana, an editorial meeting to publish an issue of Puente, and getting invited to a small conference room on top of a bar/restaurant. An older man was holding forth there, speaking in very dramatic terms. He spoke for two hours without notes. I asked somebody, “Who is that?” They said “Oh, that’s Valentin Campa.” I didn’t know who Valentin Campa was, but it turned out he was a legendary figure in the Mexican labor movement, a leader of the Mexican Communist Party who ran for the presidency of Mexico in 1976, and who also led a very famous long and bitter railroad strike in Mexico.

So, I got to hear him speak and I guess two hours in Mexico is long by some standards, though I’m told that Fidel Castro used to speak for eight hours without notes. But it was quite an impressive thing to see somebody hold forth like that, in a completely coherent way for two hours without looking at a single note.

On the board of LACAPS there was a man named Goetz Wolff, who was an academic researcher based at the Urban Planning School at UCLA. I remember in 1984, about a year into my assignment with LACAPS, he suggested to me, “You know Peter, you might benefit from studying at UCLA at our School of Urban Planning” (which was a very pro-labor program) “And maybe you’ll want to do a joint Urban Planning/Masters in Business Administration, an MBA.”

This intrigued me, and I thought “Well, I’m at kind of a moment in my life (I was 33 years old) where I wasn’t really sure where I was going, but I certainly could use additional skills.” So I thought, “I’ll take a shot at that.” I applied to this joint degree program in the Spring of 1984 and, to my surprise, got accepted to study for a Masters in Urban Planning and a Masters in Business.

In the fall of 1984 labor radical and proletarian fighter Peter Olney entered the Anderson School of Management at UCLA.

More to come in the next installment on that particular undertaking, which was interesting, exciting, and very useful. I called it studying behind enemy lines!

.

“Again, as in Olney Odyssey #20, I benefited from the able and professional editing of my friend Byron Laursen”

…

Letter From London

By Wright Lewis

Yes, the riots are bad but – and I’m not trying to be smart here – they are entirely predictable.

Fifty years of neoliberalism coterminous with the decimated economy of a former empire, sold off to global capital. The result is a largely under-educated, de-unionised, self-identifying ‘white’ working-class, prey to fascism via the Murdoch/Rothermere media empires and the simultaneous thinly-disguised scorn of the liberal establishment. This isn’t new. It was the Blair government, Thatcher’s heirs, that began the demonisation of the working class and was responsible for the adoption of draconian anti-migration policies.

Currently, one of the most worrying confluences is the nexus between – Far Right figures and the Israeli state. So, we have fascists on the streets here marching under the same flags as the IDF against Muslims. You can see where this came from and is going. And why the British state, in hoc to Netanyahu and the Israeli government, could never allow an internationalist who supported a Palestinian state anywhere near power. Into that vacuum created by charges of antisemitism championed by people like Jonathan Freedland et al at the Guardian has rushed a really well organised pan-European fascist movement (Italy, Hungary etc etc).

It’s framed by the Right as a civilisational conflict – (see for example, Modi’s India,) but then also reflected in the liberal establishment media still drenched in Cold War-isms that is being played out in proxy wars like Ukraine (which was already stuffed with real Naz*s). The issue of course – as demonstrated especially by the Guardian’s coverage of Gaza – is that the Overton Window has moved significantly rightwards on both sides of the Atlantic. This is possibly the end game of Globalisation in its current form, and I’m not sure where we’ll end up.

Starmer, an establishment asset by any measure is shitting it. I’m hearing that only hysterical voices in his party have stopped him going abroad on vacation and making a puerile statement (I’m not making this up). This is what happens to ALL liberals that cloak themselves in nationalism (see the SDP in 30s Germany). They get eaten.

I’m going to bed. It’s up to Gen Z now to fight this. I have confidence they will. But having lived through the NF in the 70s I can’t pretend I’m not worried. We learn from the past – just not necessarily fast enough.

…

For more information on what is happening in Britain:

Ella Baker School of Organizing: After nearly a week of racist violence across the country, the School has produced a statement based on our analysis of the causes and the steps that need to be taken to defeat the narratives of division which have fueled these shocking scenes.

Politics: With Whom and For What

By Mike Miller

Preface

Wilson Carey McWilliams, mentor, teacher and friend during my days in the early UC Berkeley student movement, said, “Politics is with whom and for what, and in precisely that order.” [paraphrased] (The full quote: “The political process is an effort to unite [people] in the pursuit of a common goal and vision. Politics, then, involves two questions: the question of ‘with whom’ and the question of ‘for what.’ Furthermore, it involves these questions in precisely that order.”)

My appreciation for that thought’s importance has steadily grown over the years. It is especially relevant to the times in which we now live. Here I apply it to the angry reactions to Teamster Union President Sean O’Brien’s speaking and speech at the Republican National Convention (RNC).

I don’t write to support what he did—but to attempt to explain it from an outsider’s perspective so that the energy condemning him is better spent.

What He Said (in brief)

O’Brien gave the Republican National Convention a militant defense of working class interests and organized labor as the best vehicle to fight for them. He declared himself a “life-long Democrat” and noted that past labor trust in Democratic Party politicians had been misplaced—(he didn’t acknowledge Biden’s strong support for unions and ignored the deeply anti-union history of the Republican Party in general, and Trump and Vance particularly). He added criticism of “backlash from the Left” that attacked him for being there.

The 1.3 million Teamster membership appears equally divided on the presidential race, with many of them having voted for Trump in earlier elections, and committed to him again in 2024. That membership is now engaged in an internal process—a small “d” democratic one—to determine whether, and if so who, to endorse. From what I understand, this process was initiated by O’Brien and his allies and is the most small “d” democratic one that has taken place in the Teamsters for many years, if ever. That O’Brien wants that process to take its course seems a welcome sign to me.

O’Brien sought favor with Trump by calling him “one tough SOB,” and thanking him for opening Republican doors previously closed to the Teamsters. He gave the impression that the Republicans might actually support unions. I think he could have gotten where he wanted to go without doing that. Harking back to Abraham Lincoln would have been a better way to go.

What His Critics Say

Criticism of O’Brien has been widespread among labor, left, progressive and liberal observers. Among the most thoughtful of these are Larry Cohen’s Nation article, “Donald Trump Is Not a Friend to American Workers”, and Labor Notes Alexandra Bradbury‘s July 18, “O’Brien Speech Played into Republicans’ Phony Pro-Worker Rebrand”.

The criticisms are widely noted, and don’t need repetition here. But there are other things in the articles that deserve both mention and emphasis. Clear clues to why O’Brien might have done what he did are to be found in these critics’ articles.

Bradbury/Labor Notes

“Union leaders, though, should lead. They owe it to their own members—and to every member of the working class who would be harmed by a second Trump administration—to fight to keep anti-worker politicians out of office.

“We get why union leaders want “access”; they’ve been shut out of real influence for so long.(emphasis added) But it’s delusional to think that Trump might swap out his anti-worker—really, anti-humanity—policies; they are at the core of his being. One more person kissing his ring won’t change that.”

When leaders and organizations don’t have the power to win something, they seek access to insiders to help them get it. That may be part of what O’Brien is doing. Certainly in the long-term it doesn’t work, and often it doesn’t in the short-term. But it does give “consumer members” the idea that leaders are trying to represent their interests. He may also be taking his pro-Trump members through a process that leads them to conclude for themselves that Trump isn’t their man. That would be very good.

Cohen/The Nation

“For too many of us in labor, we confuse our individual journeys in life with a collective one. We all echo the rhetoric of an “injury to one is an injury to all,” but too often our own immediate fame, or even our own organization, takes precedence over the needs of working-class Americans. With just 6 percent of collective bargaining covered here in the United States—the lowest, by far, of any democratic nation—we need to focus on outcomes, not our individual value as a messenger.

“We can’t condemn O’Brien for speaking at the RNC unless we commit to working together in a much deeper way, and building a movement for economic justice and democracy, and a political movement that delivers results, and not just promises.” (emphasis added)

What Cohen confirms is that the labor movement we would like to see is not the labor movement that is. “Unless” is the key word here. The “movement” Cohen has worked for remains an ambition to be realized, not yet a fact on the ground. We have labor organizations, not a labor movement. The question is: how to build one.

Perhaps the sharpest indictment of O’Brien comes from a fellow Executive Board member of his union:

“We have been used enough! If O’Brien is going to satisfy his ego, if he’s going to pander and beg for the Republicans to abandon their anti-union policies, then the Teamsters’ membership would be better served if O’Brien stayed home.” John Palmer, a Teamster Vice-President, “Teamster President Sean O’Brien Should Not Speak at the RNC,” writing in New Politics (7/10/24).

Much as I appreciate and have learned from New Politics over the years, I feel on firm ground when I say not many Teamsters read it. It reads like the thought of someone positioning himself to oppose O’Brien in the next IBT election.

Here’s a different spin on O’Brien, after reading a number of the negative ones: He is walking a tight rope between where his membership is, where the rest of organized labor is, and where the country is. I hope he walks it safely. In any case, the deluge of criticism is hardly a fraternal one, and it is fraternal conversation that is required to build a movement not a number of separate organizations and separate individuals jockeying with one another for position in the labor and political worlds.

The “Labor Movement”

It is widely recognized among radicals that most unions are service and advocacy organizations. “The union” is a combined insurance company and law firm. Elected leaders and staff do things for not with members. They deliver services for them and speak in their behalf. They “turn them out” for internal and general elections. At best, union democracy imitates national political democracy: honest elections are held; a few leaders develop a following among activists; together they seek to sell their candidate as the best person to act for the members.

To expect the leader of that kind of organization to take a position that is deeply divisive within his own organization is asking too much. The expectation of these leaders that they will “educate” the rank-and-file is dangerous—in practice it means leaders tell members what they ought to think and do, sometimes by lecturing to them, other times using participatory techniques without their liberation principles, and speak on their behalf without representing what they think.

With whom

The country in general, and workers in particular, needs a strong labor movement whose participating unions act powerfully for their members, the communities in which their members work and live, and the common good. They can best do that by building their own people power and acting in concert with other people power organizations—both at the workplace and in communities. Characterizations of newly elected reform leaders as “kissing [Trump’s] ring” aren’t helpful. In my experience, they turn regular people off, insuring that they will remain the consumers of what others claim (and sometimes hope) to do in their behalf.

Fraternal debate and deliberation are what is now needed. It is needed in face-to-face forums, not in the mass media. It needs to reach deeply into the rank and file of all the organizations and constituencies required to build a base for transformative politics in the United States.

Self-righteous characterizations of rivals (as distinct from adversaries) are not helpful.

For what

We agree on a lot, but not so much on the means to get there. In recent times, the Left hasn’t been particularly good at the latter—i.e. fraternal discussion and debate. It has to cross this bridge before its common good program of equality, liberty, solidarity, community and justice for all can take concrete shape that will convince majorities.

Conclusion

Eugene V. Debs got it right:

“…I do not want you to follow me or anyone else; if you are looking for a Moses to lead you out of this capitalist wilderness, you will stay right where you are. I would not lead you into the promised land if I could, because if I led you in, some one else would lead you out. You must use your heads as well as your hands, and get yourself out of your present condition; as it is now the capitalists use your heads and your hands.”

I can conclude no better than to quote from a leader in Teamsters for a Democratic Union (TDU) who doesn’t support the indictments of O’Brien and wishes to remain anonymous:

“Trump is a master peddler of hate and division and a lethally dangerous front man for Wall Street, employers and the ruling class. TDU members are some of the best leaders I know to organize workers away from the Trump disaster. They’ll be in this fight, just not in the name of TDU.”

…

To learn more about Mike Miller and his work, visit: www.organizetrainingcenter.org

Labor Organizer Chyanne Chen Runs For SF Board of Supervisors

By Katie Quan

In the November 2024 election, Chyanne Chen is running for the Board of Supervisors in San Francisco’s District 11, an area that includes the neighborhoods of Cayuga Terrace, Crocker Amazon, Excelsior, Ingleside, Merced Heights, Mission Terrace, Oceanview and Outer Mission. I first met Chyanne in the early 2000s when she was organizing homecare workers for the Service Employees International Union (SEIU), and she impressed me as a scrappy young immigrant organizer who was deeply committed to the workers she was organizing. Ten years later we met again in China when she represented her union to establish relations with unions in China, and where she articulated the need for workers to build solidarity across borders. Now ten more years later she is running for political office, a transition which is unusual among Asian Pacific Islander labor organizers. To understand what she was thinking and what kind of support she has, I spoke with Chyanne and two of her supporters, Dr. Albert Wang and Rebecca Miller. This is what they had to say.

Katie Quan (KQ): Chyanne, what made you decide to run for political office?

Chyanne Chen (CC): It’s about my kids. I want them to be able to live here in a San Francisco that is safe, affordable, with a good quality of life.

But we have some problems. My family has experienced hate crimes–my daughter has been spit on three times and my aunt got pushed because they are Asian. During Covid the message out there was if you were Asian you were the virus. No one should experience this kind of hate, not Muslims, Blacks, Jews, or anyone. And if you called the police, nothing was done, so people stopped calling. But when they stopped calling there was no record of incidents, so the police wouldn’t have the data to send officers out. It is frustrating.

These days it’s hard to survive as a working class immigrant. The cost of living is so high that most people can’t afford to live in San Francisco. And cutbacks in services like mass transit deeply impact them. Recently I spoke to a man in my district who told me that an employer in Chinatown wouldn’t hire him because he didn’t think the worker could get to Chinatown by 7 am to open his shop, because the buses don’t start until 6 am, and often they are not on time. The only way the employer would hire this man was if he moved to Chinatown. This is unacceptable!

Even those with their own cars have issues with quality of life. Traffic is slow, and finding a parking spot is a headache.

The biggest drive for me to run this year is that there is a risk that there will be no Asian Pacific Islander (API) representation on the Board of Supervisors. That would be terrible–there is a lot at stake. Since a number of long-time community leaders have urged me to run for political office, I began to consider running. If I ran, it would be an opportunity for our working families’ voices to be uplifted–immigrants, Asians, women, moms. I would ensure that policies and actions to enable families to stay in San Francisco are enacted. Even though I would be elected as a District 11 Supervisor, many other API residents outside my district would likely feel that I could represent their voices.

I have never run for public office, and the pressure has been really intense. But my family is totally supportive, and I am going to give it my all.

KQ: What do you want to accomplish?

Safety is the #1 concern for our community right now. It means personal safety, but includes making sure that we invest in first responders, including police officers, firefighters, 911 dispatchers, and front line essential workers like nurses. It also means making sure that we support people who have already been impacted by the system, meaning those who are incarcerated or formerly incarcerated, so they have housing, jobs, health care, and so on, and have pathways to becoming meaningful members of society.

“When we know neighbors really well, we get stronger and are resilient in the face of adversity.”

When talking about safety, prevention is really important. We have to especially make sure that our young people bond with their communities, and receive loving, caring, and uplifting from others. When I walk the business corridors in the Mission, around Geneva and Ocean, the merchants talk about robberies by young people, like grabbing cell phones and running away. There might be many causes of this, like poverty, but if we have programs for youth early on to find meaningful things in life to do, we can prevent them from harming themselves and members of their community.

We have to invest in our youth so they have a path to hope in the future, with skills, housing, basic medical care and fine values. They have to “own” their community. I myself was loved by others and uplifted by many, and I benefited from youth programs when I was a teenager. I was cleaning graffiti, helping at the library, talking to merchants, all the while bonding with residents in the community. This is what builds support systems and a safer community. When we know neighbors really well, we get stronger and are resilient in the face of adversity. We understand that individual acts of bad behavior do not reflect on an entire race of people.

In this context, it’s important that the City’s government agencies distribute services equitably. I’m all about investing in education, including after-school programs. You know that the west side of the city (Sunset and Richmond) schools have better after-school programs, so a lot of Asian families travel far to send their kids to these schools. But how can we make sure that all neighborhoods have good-quality schools? As Supervisors we cannot directly impact that, but we can make sure that after-school programs provide enrichment that will complement basic education.

“Right now there are 1000 vacancies in the Department of Public Health, so they are vastly understaffed.“

Of course, there is the issue of government administration. Right now there are 1000 vacancies in the Department of Public Health, so they are vastly understaffed. What suffers is programs like ones that I participated in as a teenager. As I said, these programs help young people to find a sense of purpose in life, meaning, and accountability. But these programs are being cut back because of staffing issues.

The number two part of my platform is making sure that people have secure jobs in the city. With my background at the union, I am obviously concerned about workers. The workers providing care to our kids and parents need a pathway to providing quality care while working good jobs. Homecare workers in San Francisco only have 40 hours of paid sick leave, and they don’t have pension benefits. They deserve much more, and there is a long way to go. We need to have training for low wage service workers like them, so they can get higher pay and more job stability. We need to invest from kids to elders.

The next part of my platform is about supporting small businesses. I think we should hold the government accountable to residents and continue business corridor revitalization. These will help build community and resilience. In the Mission/Geneva/Ocean area, a lot of small businesses are owned by immigrant women, and they don’t know how to access resources, and they don’t trust the government. The Office of Small Business might have grants available, but these business owners don’t know about them, and when they find out, they might not think that it’s worthwhile to fill out a 20 page application for $5000. Some agencies, like one in the Excelsior district, don’t have the staff to reach out to small businesses in the languages that the business owners speak. These community relationships take a long time to develop, and because I’ve built those relationships over many years, I feel that I can bridge that gap.

There are many needs for services for kids and seniors, but part of the problem is that there is no one like me who has the organizing skills to reach the community, build alliances across different communities, and then advocate at City Hall. I started being an active volunteer in the community at age 16 at the library, supporting small businesses, SRO seniors, fire prevention, tutoring kids, putting on earthquake workshops. Now I am active in the PTA. In my last 24 years, it has been nonstop volunteering and supporting the community.

What is unique about me as a candidate, is that I have strong experience working with diverse coalitions, including Latino, Black, LGBTQ and Asian communities. I am a good listener and communicator. I go to budget hearings to make sure that budgets reflect the needs of the communities, and are equitably distributed.

“You have to imagine outside the box“