Democratic socialist post-election musings

By Tom Gallagher

Had Bernie Sanders won the 2016 Democratic nomination and gone on to defeat Donald Trump — as most polls suggested he had a better chance of doing than Hillary Clinton, the actual nominee — he would be now entering his lame duck period, and perhaps Donald Trump might not figure in the current discussion much at all. (Alternately, had the party poobahs not closed ranks behind Biden with lightning speed to deny Sanders the nomination in 2020, he might have just completed his campaign for a second term — which he clearly would have been fit to serve.)

Eight years on

Sanders did not succeed in bringing democratic socialism to the White House, of course, but he did deliver the message to quite a number of other households during the Democratic nomination debates. As a result, two presidential cycles on, democratic socialists have now run and won races all the way up to the U.S. House, and democratic socialism has now become a “thing” in American politics. Not a big thing, really, but most definitely a thing. Between the Republicans, right-wing Democrats and the corporate news-media, it’s a thing that certainly draws more negative mention than positive — but given that its critique of American society pointedly includes Republicans, right-wing Democrats and the corporations that own the news-media, we could hardly expect it to be otherwise.

During this time, self described democratic socialists have been elected and they’ve been unelected. They’ve exerted influence beyond their numbers; and they’ve also struggled with the hurly burly of political life. Some have been blown away by big money; some have contributed to their own downfall. In other words, they’ve run the gamut of the electoral political world — if still largely at the margins. Any thoughts of a socialist wave following the first Sanders campaign or the election of the “Squad” soon bent to the more grueling reality of trying to eke out a new congressional seat or two per term — or defend those currently held, with efforts on the other levels of government playing out in similar fashion. But at the least we can say that the U.S. has joined the mainstream of modern world politics to the point where the socialist viewpoint generally figures in the mix — albeit in a modest way.

Lesser of two evils?

The 2024 race stood out from the presidential election norm both for the return of one president, Trump’s return being the first since Grover Cleveland’s in 1892 — also the only other time a president reoccupied the White House after having been previously voted out; and for the withdrawal of another president, Joe Biden’s exit from the campaign being the first since Lyndon Johnson’s in 1968. And, just like Hubert Humphrey in ’68, Vice President Kamala Harris became the Democratic nominee — without running in any primaries. Both of them inherited, and endorsed the policies of the administration in which they occupied the number two office, which included support of a war effort opposed by a significant number of otherwise generally Democratic-leaning voters.

In Johnson’s case, the withdrawal of his candidacy had everything to do with that opposition, and the shock of Minnesota Senator Gene McCarthy drawing 42 percent of the New Hampshire Democratic primary vote running as an anti-Vietnam War candidate. But when Humphrey won the Democratic nomination and the equally hawkish Richard Nixon took the Republican slot, the substantial number of war opponents felt themselves facing the prospect of choosing the lesser of two evils. The dismal choice presented in that race soured untold numbers of voters on the left who came to consider a choice between two evils to be the norm for presidential elections. Over time, the hostility faded, with most coming to judge the choice offered less harshly, now more one of picking the less inadequate of two inadequate programs — until now. The intensity of opposition to the Biden-Harris support of Israel’s war on Palestine has certainly not approached that shown toward the Johnson-Humphrey conduct of the American war against Vietnam. But for a substantial number of people who considered it criminal to continue supplying 2000 pound bombs to Israel’s relentless ongoing disproportionate obliteration of Gaza in retaliation for an atrocity that occurred on a day more than a year past, this was a “lesser of two evils” choice, to a degree unmatched since the bad old Humphrey-Nixon days.

And yet, while we don’t know how many opted not to vote for president at all, we do know that those who did vote almost all did make that choice. Even with a Democratic nominee preferring the campaign companionship of former third-ranking House Republican Liz Cheney to that of Democratic Representative Rashida Tlaib, a Palestinian democratic socialist, third party votes did not prove to be a factor. There was no blaming Jill Stein this time.

Democratic Socialists of America

Organizationally, the greatest beneficiary of the Sanders campaigns has been the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA). Ironically, while Bernie has been the nation’s twenty-first century avatar of socialism — generally understood to be a philosophy of collective action — he himself is not a joiner, being a member neither of the Democratic Party, whose presidential nomination he has twice sought; nor DSA, an organization he has long worked with. With about 6,000 members, the pre-Sanders campaign DSA was the largest socialist organization in an undernourished American left. In the minds of some long time members, their maintenance of the socialist tradition bore a certain similarity to the work of the medieval Irish monks who copied ancient manuscripts whose true value would only be appreciated in the future. But when the post-Sanders surge came, there DSA was — popping up in the Google search of every newly minted or newly energized socialist looking to meet people of like mind. Membership mushroomed to 100,000. Organizational inflation on that order that does not come without growing pains — the sort of problems that any organization covets, but problems nonetheless.

DSA’s very name reflects the troubled history of the socialist movement. In the minds of early socialists the term “democratic socialist” would have been one for Monty Python’s Department of Redundancy Department. The whole point of socialism, after all, was to create a society that was more democratic than the status quo, extending democratic rights past the political realm into that of economics, and the difference between socialism and communism was pretty much a matter that only scholars concerned themselves with. But with the devolution of the Russian Revolution into Stalinism, “communism,” the word generally associated with the Soviet Union, came to mean the opposite of democratic to much of the world. And in the U.S. in particular, “socialism” too seemed tainted, to the point where socialists felt the need to tag “democratic” onto it.

DSA was an organization, then, where people most definitely did not call themselves communists. It was not the place to go to find people talking about the “dictatorship of the proletariat,”“vanguard parties,” or other phrases reminiscent of the 1920s or 30s left. Among its members, the Russian and Chinese revolutions, while certainly considered interesting and significant — fascinating even, were not events to look to for guidance in contemporary American politics.

And then the expansion. A lot of previously unaffiliated socialists, pleasantly surprised — shocked even — to find the idea entering the public realm, decided it was time to join up and do something about it. The curious also came, eager to learn more of what the whole thing was all about, maybe suffering from imposter syndrome: “Do I really know enough to call myself a socialist?” And then there were the already socialists who would never have thought to join DSA in the pre-Sanders inflation era, some with politics that DSA’s name had been chosen to distinguish the organization from. The expanded DSA was a “big tent,” “multi-tendency” organization. Soon there was a Communist Caucus in DSA — along with a bunch of others. Whether the internal dissonance can be contained and managed long-run remains to be seen, but then what is politics but a continuous series of crises? It’s to the organization’s credit that it has held itself together thus far, but for the moment some hoping to grapple with the questions of twenty-first century socialism may encounter local chapter leadership still finding their guidance in reading the leaves in the tea room of the Russian Revolution. Initial stumbles in the organization’s immediate response to the Hamas attack in Israel prompted a spate of long-time member resignations — some with accompanying open letters — but the trickle did not turn into a torrent.

In the meantime, DSA, now slimmed down to 80-some-odd thousand members, has also struggled with the more immediate, public, and arguably more important question of working out a tenable relationship with those members holding elected political office. While the organization encourages members to seek office and benefits from their successes, it understandably does not want to be associated with public figures with markedly divergent politics. At the same time, office-holding members are answerable to their electorate, not DSA. In the light of some recent experiences on this front, Sanders’s non-joiner stance starts to look somewhat prescient. DSA’s long-term relevance will depend on its ability to carve out a meaningful role as a socialist organization that is not and does not aspire to being a political party.

2028 and beyond

Much of the post-election Democratic Party fretting has quite appropriately centered on the degree to which it has lost the presumption of being the party of the working-class. One solution to the problem was succinctly, and improbably, formulated by the centrist New York Times columnist David Brooks: “Maybe the Democrats have to embrace a Bernie Sanders-style disruption — something that will make people like me feel uncomfortable.” By Jove, you’ve got it, Mr. Brooks: Comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable! But Brooks goes on to fret, “Can the Democratic Party do this? Can the party of the universities, the affluent suburbs and the hipster urban cores do this?”

Can students, teachers, suburbanites and hipsters “embrace a Bernie Sanders-style disruption?” Well sure, quite a few have already done so — twice now. The roadblock clearly does not lie there. The real problem is those uncomfortable with the idea of a Democratic Party no longer aspiring to the impossible status of being both the party of the working-class and the party of billionaire financiers. For a look into the void at the core of the Democratic Party we need only think back to that moment in February, 2020 when it began to look like the “Bernie Sanders-style disruption” just might pull it off and the party closed ranks, with candidates Pete Buttigieg, Amy Klobuchar, Michael Bloomberg, Elizabeth Warren, and Tom Steyer scurrying out of the race and endorsing Joe Biden in a matter of just six days. None of this underscored the party’s determination not to turn its back on the billionaires so clearly as the fact that at the time of his withdrawal Bloomberg was in the process of spending a billion bucks of his “own money” in pursuit of the nomination. Obama’s fingerprints were never found on these coordinated withdrawals but most observers draw the obvious conclusions. And we know that the prior nominee, executive whisperer Hillary Clinton, was certainly all in on the move. Herein lies our problem, Mr. Brooks.

But how? And who? The how is the easy question in the sense that Bernie Sanders unforgettably demonstrated how much the right presidential primary candidate can alter the national political debate — even when the Democratic Party establishment pulls out all the stops to block them; and even if succeeds in doing so. At the same time, the difficulty in winning and holding congressional seats shows that, while self evidently necessary in the long run, those campaigns do not have the same galvanizing potential. Who? At the moment, the only person whose career thus far suggests such potential is New York Representative Alexandria Ocasio Cortez. But then a lot can happen in four years. And Donald Trump’s reelection portends four years of American politics bizarre beyond anything we’ve seen before.

…

This piece first appeared on Portside

This Was A Very Close Election, Trump Won, But Got Less Than 50% of The Popular Vote, Now Let’s Act Like That and Build On It – Monroe County, Pennsylvania – A Case Study

By Jay Schaffner

With a much larger population than previously, with a larger youth population, the erosion of vast numbers of voters throughout the country is cause for alarm – for voting rights and for democracy and warrants further study and exploration.

Kamala Harris lost the election, her vote was just under 7-million votes less than that of Joe Biden in 2020. Four million fewer voted nationally than four years ago, due both to a large stay-at-home vote as a protest by voters to the continued war in Gaza, as well as to increased voter suppression by Republicans in many states. Still the turnout of registered voters was higher than it was four years ago.

Donald Trump won, but he did not get a majority of the national vote. This year’s election had the highest voter turnout of eligible voters – 63.68% of the last five presidential elections, according to The Election Lab at the University of Florida, which has tracked data for all elections since 1789. Trump’s winning vote was the lowest since Bush in 2000.

The reality is that Trump is a minority president, polling less than 50% of the national popular vote. In the battle-ground states, Trump won by less than 1% in Wisconsin; and less than 2% in both Michigan and Pennsylvania, the three “Blue line states.” He barely won by two percent in Georgia and squeaked by with just 3% margins in both Nevada and North Carolina. squeaking by with 1% margins in many states.

Voter turnout (percentage of registered voters voting) was higher this year than the pandemic year turnout of 62% in 2020, when most voting was done by mail; then voting was done with Donald Trump in office, and voters were voting against the reality of what another four years of pandemic Donald would be for themselves, their families, their communities and the country.

Voter turnout of registered voters was higher than the then high of 62.17 in 2008, when voters were voting for hope and against the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and with Barack Obama running against the reality of the GOP and George Bush.

In this year’s election, with a larger voter pool than any previous election, Kamala Harris received more than four million more votes than Obama did in 2008 and more than eight million more votes than Hillary Clinton did in 2016.

With a much larger population than previously, with a larger youth population, the erosion of vast numbers of voters throughout the country is cause for alarm – for voting rights and for democracy and warrants further study and exploration.

Racism and misogyny were a factor. But they were not the factor that was predicted by nearly all the pre-election polls. The polls for the most part got it wrong, with the exception that it would be a very close race. There was no major defection of African American men to Donald Trump. Similarly, there was no major machismo swing towards Donald Trump – the Hispanic male vote for Trump was 48%, with 49% voting for Harris, reflected a division in the population as whole.

There was no major massive gender gap between women going for Harris and men going for Trump. The one place where there was a significant gender gap was among youth voters under age 30 – here the gender gap was 30 points with young men breaking for Trump! (Trump sees high number of young voters in the 2024 election (NBC) Post-election data in fact show that there was nearly an even split between men and women nationally going for both Harris and Trump, with some notable exceptions:

- There are more women in the population, and more women are registered to vote, and the reality is more women of all races voted for Trump, except for African American women

- Roughly 53% of white women ended up voting for Donald Trump (only 10% of African American women voted for Trump, white 39% of Hispanic women voted for him, according to the 2024 Fox News Voter Analysis).

- There was a higher youth vote for Trump than was anticipated – 46% of the age 18-27 vote, slightly higher among Millennials, but 51% among Gen-X-ers.

- Seniors nearly evenly divided, with Boomers going 51% for Trump, 47% for Harris, but those Seniors over 79 going for Trump at an even higher rate – 57%.

In all seven of the battle-ground states, the voter turnout of registered voters was much higher than nationally.

Did voters in other states not turn out because their votes didn’t matter? If one looks at the New York State vote going back to 2008, the answer is no. There was a higher turnout of registered voters this year than in any of the previous presidential elections going back to 2008, however statewide

there were 700,000 fewer voters than in the 2000 election. In a heavily Blue state, this can be

counted as voters that stayed home and did not turn out to vote for Harris-Walz for a variety of

reasons.

Harris raised more money than Donald Trump and the GOP, so what went wrong? What happened?

Monroe County, Pennsylvania – A Case Study

I spent ten weeks knocking on doors in Monroe County in Northeast Pennsylvania, NEPA as it is called. Pennsylvania, one of the seven battle-ground swing states with 19 electoral votes, was considered the “prize.” It was supposed to be part of the Blue Wall, along with Michigan and Wisconsin.

Pennsylvania has close to ten million eligible voters, of which so far 7,025,000 ballots have been counted. Everyone is familiar with the population rich anchors of Philadelphia and Pittsburgh. The more than fifteen counties that comprise the NEPA region of the state cast one-and-a-quarter million of those votes. That is why Kamala Harris and Tim Walz, and Donald Trump and J.D. Vance anchored much of their campaigns in this part of the state.

Over those ten weeks I personally knocked on more than 2000-2500 doors in different parts of Monroe Country. Along with my wife, we emailed every friend, co-worker, relative, neighbor, many of the musicians that I had represented for over twenty years, activists that I had known and worked with. The response was incredible – 46 responded and came out to join our group in Monroe County, a group of us that had worked together going back to the 2008 Obama campaign. We worked with the local Monroe County Democratic Organization and the Harris-Walz Campaign. Some came for a day, some for the weekend, some for longer. Additionally, friends helped email more than 5000 postcards to Pennsylvania, Georgia, North Carolina and Michigan voters.

Our country came out of the McCarthy period to end Jim Crow, to pass Civil Rights and Voting Rights legislation, and then to help end the war in Viet Nam. And two years after Richard Nixon swept the 1972 election, this is the country that drove him from office and nearly impeached him the following year.

Can we do this again?

I think we can, but we need to do this working differently, reaching out to those that voted, for various reasons, for Trump, and at the same time, in defense of reproductive rights, to raise the minimum wage and numerous other ballot measures in states from one end of the country to the other.

Some say the Economic Issues Were Not Emphasized – Not Enough – Those some were not in northeast Pennsylvania.

Along state highways there were signs saying, “Kamala Wants to Raise the Minimum Wage.” The minimum wage in Pennsylvania is $7.25. Those some did not attend the mass rally that I did in Wilkes Barre, where both economic issues and reproductive rights were stressed.

Could there have been more signs? Sure. Could there have been better literature? Sure. The message at the rallies from friends who attended the rallies with Tim Walz was that he hit on the same issues. The campaign did not control how the news media covered those rallies.

The campaign did control the message in the ads – these could have been vastly improved on.

The volunteers that we brought out came because of the existential threat of fascism. That does not mean that this was the number one issue on the minds of voters. Talking with voters at their doors, the number one issue was prices they paid for goods in the stores, jobs or lack of jobs, and inflation. After the fact polling shows that .as well.

But changing the message when you are canvassing, and when the infrastructure of the campaign is doing something else is a daunting and perplexing task.

The campaign should have championed an economic message of jobs, raising the minimum wage and tying those wages tied to inflation. But would Wall Street and the small businesses that the campaign was pitching to have gone along with that? Did the campaign count who had the votes, not just some of the dollar contributions?

Pitching a $25,000 credit for first-time home buyers when there aren’t homes to buy, when the cost of homes in the NEPA area is from $200,000 on up, amounts to closing costs. People realized it just wasn’t real, or didn’t apply to them, or to their immediate needs. They also realized that $25,000 would merely drive up the cost of what homes were actually on the market.

Similarly, the $50,000 tax credit for first-time businesses, given the cost of starting a business today, and the cost of equipment and capital improvements, was also not real to many.

Harris projected raising prescription caps for all and extending Medicare to include home elder care, but these were raised late in the campaign. Debt relief for teachers and other workers in the public sector should have been a top issue for the campaign and should be still for Democrats in Congress.

Bottom line, the economic issue of jobs, and wages tied to inflation are what should have been forefront – but that is a weakness and limitation of the Democratic Party as it is constituted.

Democrats need to advance an Economic and Social Bill of Rights that they will champion in Congress, even in a Congress that is dominated by Republicans. Such legislation can then be introduced in every state and city.

Minimum wage increases were approved in Missouri and Alaska; both those states and Nebraska passed paid sick-leave statues – all three states gave a majority of votes to Trump.

Too Much Emphasis on Cultural Issues – I Think Not

Voters clearly understood that women’s right to control over their bodies, families right to control over their collective bodies was on the line. This was expressed repeatedly in after-vote comments on why voters voted for Kamala Harris.

Voters approved a state constitutional right to abortion in seven states (Arizona, Colorado, Maryland, Missouri, Montana, Nevada, and New York); and a majority of voters in Florida voted similarly, but it failed to reach the 60% bar imposed by Gov. DeSantis and GOP-controlled legislature. (Missouri, Montana, Nevada and Florida voted for Trump.)

Other state-wide measures of significance passed by voters were:

- Colorado, Kentucky and Nebraska voters rejected school vouchers

- Alaska voters banned anti-union captive audience meetings

- Oregon voters passed a measure to protect cannabis workers’ right to unionize

(Kentucky, Nebraska, and Alaska voted for Trump.)

Strategy of Working the Margins Needs to Be Changed for Reaching Everyone

The national emphasis of the Democratic Party has been to concentrate on the inconsistent voters the irregular voters – registered Democrats who did not vote in 2022, or 2020, or 2018, or 2016 and to reach them, convince them to vote for Harris and get them to the polls.

Add to their ranks similar registered Independents who are inconsistent voters, Greens, Libertarians and even Republicans who may have signed a petition for a democratic cause over the past few years.

Left alone were registered Democrats and Independents who voted regularly. These voters were excluded from the voter call banks; the lists prepared for door canvassing. (In New York City we regularly get calls, or at least my wife does, who is a registered Democrat. This year she did not get one call, none from her union, or from any of our elected Democratic officials, urging her to vote. Since I am registered for the Working Families Party, I can understand why I didn’t get these calls.)

My experience was that the voters identified as “Independents” through this process were really closet Republicans in the main.

Over the ten weeks, I was going to some houses four and five times – once people said they were voting for Harris and the Democratic ticket and had a plan, and were visited in the past two weeks, I didn’t go again, unless it was the weekend before the election. The MiniVan (phone app used by the campaign) history showed that some of these voters were being called or texted as many as 6, 8 and 10 times since the beginning of September. And the message was always the same.

And yet, for the neighbors on the block who we were passing by, who were registered Democrats, there was no door knock, no literature drop, no phone call, no nothing. No finding out what concerned them, where they stood, if they were voting, and who they supported.

There was no training for the hundreds and thousands that answered the call of “come to Pennsylvania.” The message was, read the MiniVan script, tell people why you are for Harris, get them to commit. There was no emphasis on what were the key issues for the area of Pennsylvania we were canvassing in.

Many of the “Democrats” that we visited were not going to vote for Harris. I think the same can be said of the regular Democratic voters.

There was plenty of money in the campaign – it was just not allocated for this – this was not a priority. What was needed was a massive outreach campaign to all potential voters, to reach and educate, and then mobilize them to vote.

The approach of working the margins resulted in all the battle-ground states in a voter turnout of registered voters that was significantly better than the national average of 63.68%, but could more have been accomplished? In order to win, more needs to be accomplished.

No Real Coordination With Local People

There was no real coordination with the local Democratic Committee. No exchange of information as to what the communities were like, what the local issues were, even who the local candidates were (other than read the campaign handouts); and even sending volunteers to communities where they could not gain entry because they were gated.

On the last weekend of the campaign, we finally gained entrance to the largest community in the Poconos – a gated community. I asked why “X” wasn’t contacted; she lives in the community and got us access in previous elections. The response of the area Harris coordinator was “who is that.” My response is “she is one of the candidates listed on the literature that everyone is giving out.”

The people working for the Harris Campaign were hard working people, but they were not from the local area.In previous elections, out of area staffers came into the area much earlier (In 2012 a staffer from Kansas moved into the area in February; in 2016 a staffer from Scranton moved into the area in late May). These people learned about the area, the various communities, met with local people, lived with local people. Such was not the case with the 2024 campaign. Part of the problem was the late start of Kamala Harris’s campaign, but the key staff was here while Joe Biden was the candidate in June.

Some Specifics of the Campaign

Misogyny – Was a real factor and you could see it. So many times, when we knocked on doors and when both husband and wife or boyfriend and girlfriend came to the door together, after hearing what we were there for so often the man stayed and the woman walked away ‘to do other things,’ or the man came out to talk to us. Often the woman would come out by herself and say or whisper: ‘I’m with her and he doesn’t know it.’

Lack of a Trump Ground Game – The media was full of reports that there was no Trump Ground Game in Pennsylvania, that Musk’s efforts were breaking down, and we didn’t really see much evidence of any Trump or Republican literature on people’s doors. In the last two weeks there was literature for local state assembly Republican candidates.

But there was a Trump Ground Game – it was the Catholic Church and the different Evangelical Churches. When you would get repeated answers, and these were from “registered Democrats, “that I can’t vote for that woman because she kills babies,” because she changes children’s sex when they go to school,” because she is for “men playing on girls’ sports teams,” you know that these are organized and indoctrinated responses.

In the more western parts of NEPA there is the added factor of the Amish. The Amish community rallied to Donald Trump, and their vote cannot be underestimated in Berks County and the farms surrounding Reading and Kutztown.

There were fewer Trump signs than in previous years, but there were still fewer Harris signs. It took weeks for us to get a Harris sign, and we ordered and paid for one from the Harris-Walz campaign. The local campaign was stingy giving them out at first, and only had lots of signs the last few weeks of the campaign. In canvassing, the Trump signs were up to intimidate and terrorize neighbors to not put up a Harris sign – that was the atmosphere.

People who took signs said they felt safe doing so this year, that in 2020 the Biden signs in their part of the country had been shot down.

We found some Hispanic support for Trump – and division in families along generational lines that was inconsistent. In some families it was the younger members that supported Harris, in other families the opposite was the case. Reasons for doing so were often expressed as, “our family did it the right way,” or “our family didn’t jump the line.” Then there were the more MAGA expressions that “we are not rapists.” More Hispanic men supported Harris than Trump (49 to 48%) and amongst Hispanic women, Harris received support from 59% of Hispanic women, with Trump garnering just 39%. (2024 Fox News Voter Analysis)

Immigrants of other nationalities in our nation’s past faced similar divisions. In the 1880’s Irish who were already here, were opposed to the entry of new immigrants from Ireland.

Later in the century, new Italian immigrants faced similar hostility from Italian Americans already here. In the early part of the last century, Jews from England and Germany were hostile to the entry of Eastern European Jews, and even championed quotas, which were later enacted.

Immigrants who were already here have long sought to be “Americanized.” We are seeing this play out once again. There is a new twist, however. This time there is opposition to immigrants coming to the country from Venezuela, Nicaragua Brazil, and Cuba – countries that have taken a socialist or non-capitalist path or have tried to. So, the opposition now is also fueled by good old anti-communism.

I haven’t seen figures for the Asian American vote, but from experiences canvassing, I can say that this was similar. There also needs to be a differentiation amongst the different peoples of Asia and the Pacific Islands, where immigrants have come from, and their experiences.

African American support for Trump – we found this, and nationally it reached about 23-25% of the African American population, up from what it had been in previous elections. (The AP reports that in 2020 Trump got 13% of the African American vote, and in 2016, 8%.) In some homes it was the male member supporting Trump, in fewer, it was the woman.

Surprisingly, contrary to what the polls predicted; on election day a number of younger family members came to the door whispering that they voted for Harris.

Arab American and Palestinian Americans – we found mixed reactions from these voters, depending it seems on their age and how long they have been in the country. Some were going to be voting for Harris, some doing so reluctantly, more were going to sit the election out. None were going to be voting for Trump. Many while they would give us their choices on who they were supporting for President, were not inclined to do so when in came to Senate (Casey) and Congress (Cartwright or Wild, depending which district we were in).

Disconnect between volunteers and those being canvassed – thousands of wonderful people came to Pennsylvania to help “turn Pennsylvania Blue.” They were motivated by the existential threat of fascism posed by Donald Trump and the MAGites. They came as individuals, some in their own cars, some by bus, some flew in; others got on buses organized by Democratic elected officials and Democratic Clubs and the Working Families Party in New York; or similarly organized in New Jersey, Connecticut and Massachusetts. . Volunteers came regularly from Vermont, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Connecticut, New Jersey, Maryland the District of Columbia, some flew in from states to the west, a few, even from Canada. Others came on buses organized by their union – 1199, SEIU, UNITE-HERE, UFT, AFSCME, SAG-AFTRA, AFM and others.

Some of those being canvassed were also moved by the threat of fascism, but not many –remember these were infrequent voters, not regular voters. More were moved by the threat Trump posed to women and reproductive health and a ban on abortion. But canvassers were not prepared to take on the economic issues uppermost on those being canvassed – prices, inflation and jobs. There was no preparation of canvassers.

NEPA is low union density – seeing the busloads of union members coming in was great for this retired union organizer. It was a great pick-up for those of us at the mobilization point when the purple SEIU and 1199 buses rolled in. But when those same buses hit the neighborhoods, it was a different story. Union membership in this part of Pennsylvania is low. My neighbors in Monroe who are union members are often those who commute back to New York City, belonging to unions there, and voting in the city. Teachers here who are in a union are more likely to be in the Pennsylvania State Education Association. Some in our neighborhood are in IATSE, working jobs at venues like the arenas, casinos, stage shows, etc.

Canvassers expecting to hit the doors talking to their union brothers and sisters were disappointed.

The kicker – the last two weeks TV commercials for Matt Cartwright were disgusting. Matt Cartwright was our Congressperson. He was number ten on the GOP hit list. He was defeated.

The commercial starts out with Cartwright standing next to dam wall, saying we need this, it protects us from flooding. Next is a shot of the Texas-Mexico border wall, with Cartwright saying, ‘we need this, it protects us from murderers and rapists.’ Politico quotes Cartwright: “I took on my own party to oppose sanctuary cities and deport immigrants who commit crimes because it’s absolutely necessary for America to work,” said Rep. Matt Cartwright (D-Pa.), as his ad showed footage of the wall.

This is the campaign literature we were handing out! We were telling voters that if Kamala is elected, she needs people in Congress like Matt Cartwright to have her back. Right!

When first elected to Congress, Cartwright supported sanctuary cities and was a member of the Progressive Caucus in Congress. Later he dropped out. Cartwright reminds me of members of the Populist Party in the late 1800s, who while elected as progressives, refused to take on racism, and later even made a pact with the Klan. Hopefully, Democrats like Cartwright won’t go that far. But positions like this are not how we are going to win back support for the Democratic Party.

Both Democratic Congressional Representatives, Susan Wild (PA-7) and Matt Cartwright (PA-8) were defeated.

So, how do we build a movement that combines people that live out here, with people that help and support their work, on issues that reach out to people that voted for Donald Trump?

Writing this I was reminded of movements I participated in many years ago. One such movement was Vietnam Summer in 1967, where we canvassed everyone who lived in the Evanston community, north of Chicago. We were planning to run a peace candidate against Congress member Donald Rumsfeld in the election the following year, and we were trying to get a sense of the community in a non-election year on the issue of the war in Viet Nam, and a halt to the bombing, for negotiations.

My parents had done similar work in their suburban community of Skokie for open housing in 1965 and 1966 while Martin Luther King was leading the open housing marches in Chicago. Skokie later passed an ordinance declaring that the suburban community was ending the practice of Jim Crow housing and the covenants attached to home sales. Similar efforts were undertaken in other Chicago suburban communities.

What if a coordinated campaign were undertaken with peace forces in Monroe County, working with students from local colleges, calling for an end to U.S. military aid to Israel with the money going to fund hospitals, schools, new housing construction and libraries in our country. Elements of a campaign could be a petition, teach-ins, forums, hearings, with the aim of resolutions in student bodies, churches, synagogues and mosques; and the getting of letters to the editor, elected officials to come out in support, etc.

A similar campaign could be undertaken to Save our Social Security and Medicare – We Paid For It.

If such campaigns could get off the ground, could we seek to get progressives once again from other states to “come to Pennsylvania,” stay with Penn Staters for the weekend or longer and help us return Pennsylvania to the Blue? Could we go back to door-to-door canvassing? Could we coordinate with the Monroe County Democratic Committee, and could we use the MiniVan app for all registered Democrats and Independents, regardless of when they voted?

Donald Trump was elected President with 50% of the national vote. In eight of those states, voters in their majorities voted to support women’s right to an abortion, putting it in their state constitution in seven of them. Voters in a number of states that voted for Trump also passed incredible economic measures, aimed at alleviating the pain which working people face. This shows that a cross electoral coalition and movement can be built, if we are smart, that can include Harris voters, Trump voters, and those that didn’t vote.

So, while Trump is president, while Republicans control the Senate and hold a slim majority in the House, we can still pressure Congress, and we must. We can still pressure state legislatures. And we must. We will continue to build a political movement in the streets, in the communities, and to win and take back the legislative halls. We will still defend immigrants and immigrant families, and we must. We will still defend our trans brothers and sisters, our trans neighbors and families, and we must. We will still defend all the gains that we now have and fight against all attempts to cut our basic social safety net, and we must.

…

Photos From The Edge – March and Civil Disobedience Demand a Ceasefire in Gaza

By David Bacon

SAN FRANCISCO, CA 11/11/24 – On Veterans Day hundreds of people, including many war veterans, marched from Harry Bridges Plaza at the foot of Market Street to the office of California Senator Alex Padilla. Marchers demanded that he and Senator Laphonza Butler support a ceasefire in Israel’s assault on Gaza. More than 43,600 people have been killed in the last year, mostly women and children, and over 102,900 others injured, according to local health authorities. Israel faces a genocide case at the International Court of Justice for its actions in Gaza.

Senator Bernie Sanders called for a vote in the Senate to block further military aid to Israel. “The war in Gaza has been conducted almost entirely with American weapons and $18 billion in U.S. taxpayer dollars,” he said. The demonstration was sponsored by Veterans for Peace, the Interfaith Movement for Human Integrity, Jewish Voice for Peace, and others. Speeches called for meeting the election of Donald Trump without fear, demonstrating in the streets popular opposition to war and repression.

The march stopped to support striking hotel workers outside the Palace Hotel, one of five in San Francisco which have been on strike for weeks. Marchers and strikers both spoke of seeing the close connection between the working class demands for a decent life and a union, and the demands for an end to military support for Israel. At the end of the march San Francisco activist artist David Solnit led many in painting a colorful protest on the pavement of Bush Street, while others chained themselves together, blocking the doors of the building housing Senator Padilla’s office.

Demonstrators march from the Ferry Building to the office of Senator Alex Padilla, protesting the Israeli bombing of Gaza and demanding that Padilla support a ceasefire. The actions were organized by veterans groups, on Veterans’ Day, and the Interfaith Movement for Human Integrity.

All photographs copyright David Bacon.

To see a full set of these photos, click here

…

Glenn Perušek – A Celebration of Life

By Peter Olney

On Saturday November 2, the weekend before the big national election, family and friends of Glenn Perusek gathered for his memorial at the Slovenian National House on St Clair Avenue in Cleveland, Ohio. I was honored to speak at Glenn’s memorial. Here are my remarks:

.

“I am very happy that Gail and Dawn, Glenn’s sisters, decided to hold this memorial in the Slovenian National House. I think Glenn had an office and a living space here for a while. I know Glenn was exploring his Slovenian heritage, and I believe a trip to Ljubljana and greater Slovenia was on his agenda. I know that when I met him in 2005 he was using Perusek, but more recently his name became Perušek. (Sek vs Check) I hope I got the accent right. I called his cell phone the other day just to hear him pronounce it. Christina Perez and I were looking forward to meet up with him in Slovenia on one of our trips to Florence, Italy.

Glenn did visit us for a week in Florence in 2017. He met our Italian friends and engaged with them on everything from food to politics to futbol soccer! We make a point of awarding our guests in Florence some recognition based on their stay with us. For instance do they do the dishes or make their beds? His time with us in Florence was great, and he won “Best Male Guest”!!

In his capacity as Director of the Center for Strategic Campaigns at the AFL-CIO, Glenn safeguarded resources for my union, the ILWU. We waged several epic battles organizing a large Rite Aid distribution center in the Antelope Valley north of Los Angeles and battling an employer lockout in the Mojave Desert at a borax mine owned by the giant multi-national Rio Tinto. Glenn made sure we had the research and staff support to prevail. Because of him, the ILWU, a small but powerful union of 45,000 members, got more support per capita for new organizing than any other affiliate of the national federation.

After I retired from the ILWU in 2013, Glenn brought me on in 2015 to help teach Heat and Frost Insulators how to organize and opened a whole Building Trades instruction world for me. I had no idea what a heat and frost insulator was? We were a great team and made a lot of new friends. Tommy Williams, an accomplished organizer, and at the time Director of Organizing of the Heat and Frost Insulators, who is with us today used to call Glenn “The Professor”, a whimsical term of endearment and reverence.

What made working with Glenn so fruitful was his overall willingness, despite his rigorous traditional academic training, to call “audibles”, sports parlance for employing flexible teaching methods, to draw on the intelligence and experience and creativity of the building trades students. We would engage a student organizer at lunch, and if they had some experience or expertise Glenn would tap that student to be a presenter in the PM session.

We instituted a regular talent show at the end of the 4-day classes where we invited students beforehand to bring their poetry, musical instruments and rap to the closing session. I will never forget a Canadian Vice President of the Cement Masons, and accomplished blues harp player, stepping up in Ft Lauderdale and serenading us with some Latin tunes that he had played previously at the Buena Vista Social Club in Havana, ninety miles away. A dear friend and co-instructor colleague of Glenn’s who was not able to be with us today; Melissa Shetler is an accomplished jazz singer and closed out one of our sessions with a live performance.

Glenn was a great comrade to me and many in our labor world. He opened new pathways in my life. I think one of Glenn’s biggest recent achievements was putting together the John Womack book, Labor Power and Strategy that is very much in play and being read by young organizers everywhere. It was Glenn’s insight that made the book so unique and powerful. I thought of interviewing the Harvard historian John Womack about labor power in production and logistics systems, but it was Glenn who suggested that we get 10 of labor’s best and brightest organizers and thinkers to respond to Womack’s theses. This has generated a rich dialogical work that provokes thought and discussion and healthy controversy. This was part of Glenn’s commitment to the up and coming generation of new organizers – Ride Share Kevin, Noah Carmichael, Deven Mantz, Carey Dall and Taft Mangas. Oh and don’t forget veteran unionists like Chris Scarl who Glenn helped get elected to the City Council of North Olmstead, Ohio.

This memorial of course coincides with the final push for the national elections. Christina Perez and I are in Orange County, CA working to flip several House seats to the “D” column and I know Glenn would be with us in spirit and curious as to our findings on the “doors.” But the Perusek Memorial takes precedence on our calendar because of our love for Glenn and our deep curiosity to learn more about our dear Brother from his family and friends. Our curiosity abides…

We go back to Orange County for the final push and we dedicate our work to Glenn Perusek. Glenn Perusek Presente!”

.

The booklet that is presented here on The Forum was designed and produced by Gail Perusek and Dawn Stang, Glenn’s sisters. It was distributed to all the attendees at the memorial.

To view the booklet fullscreen: Click the symbol on the far right of the line below the image

…

This Rural Political Strategist Says Democrats Need to Learn from Winners

By Justin Perkins - Barn Raiser and Joel Bleifuss - Barn Raiser

This piece was originally published in Barn Raiser, an source for rural and small town news

“The Democrats are stuck on this consultant-driven, top-down approach to campaigns that is not working.”

Johnson teaches political science part time at Monmouth College and lives outside Monmouth in Warren County, Illinois.

Barn Raiser spoke with him about last week’s election and why the Democrats are having such a hard time connecting to rural voters.

What stood out to you about how rural America voted?

I wasn’t sure Trump could do better as far as the share of the rural vote in 2024 versus 2020. But he did.

In my county, Warren County, Illinois, which is an Obama-Trump county, we had a 15-point swing toward Trump, the largest of any county in the state.

This election in some ways matched what’s happened internationally, where incumbent parties have lost everywhere. It’s a global trend that is partly due to the impact of inflation. I’m older. I remember the last time we had bad inflation was in the 1980s, and it was devastating. Trump was very aggressive in making that case on the economy.

But I put a lot of the blame on Democrats who have not invested in rural America. The Democratic Party is focused on doing things the status quo way, running TV ads and making a lot of consultants rich.

Whenever it comes to rural America, you’ve got big city consultants coming in and saying, “We know what to do.” Yet people out here who live in rural America understand the dynamics better, and they’re being passed over. The Democrats are stuck on this consultant-driven, top-down approach to campaigns that is not working.

Why has the Democratic Party become reliant on consultants who lack a track record of success?

I wish I knew. It’s very frustrating to see this happen over and over and over again.

After the 2016 election, I worked with my former Democratic congresswoman Cheri Bustos to visit hundreds of Democrats who had won in rural areas. We asked, “How did you do it?” These were the survivors, and in 2017, we published a 50-page report about their stories.

After I wrote the report, Cheri told me up front, “Robin, one thing I’m not going to do is raise money for PACs off of this.” They wanted her to raise money to give to them to do TV ads appealing to rural voters. It was like flies on shit. (Sorry for the barnyard comparison.) Here were people who had come for the latest trend just to make money.

Right now, a bunch of TV consultants are probably in the Bahamas, drinking tropical drinks from the money they made on the recent round of campaigning. What the Democrats need to do more than anything else is take a long, hard look at this model.

They need to start from the ground up. Sure, you need funders from the big cities. But it’s got to be done by rural folks. It’s been eight years since Trump was first elected, and there’s been no movement to do this the right way.

What does the Democratic National Committee have to do with that lack of progress?

The term I use is “failing up.” We have a lot of people that lose in rural areas, and then they’re promoted to the DNC’s Rural Council and are talking on TV. There are candidates who have actually won in rural America, but you never hear about them.

Here’s your spokesperson for rural Democrats, and it’s somebody that lost their last race. What the hell? It’s like in football. Instead of going to the Kansas City Chiefs to learn how to win, you’re going to go talk to my Chicago Bears.

He parks his old red truck, a 1999 Dodge Ram, on the side of the road and has a handmade sign that says, “Stop and Talk with Senator Jeff Smith.”

It’s not that hard. Go talk to people who win and ask them how they won. In 2022, I wrote a piece for Washington Monthly with the idea of putting people front and center that won their rural districts.

Take Jeff Smith, for instance. He’s a state senator from rural Wisconsin. He parks his old red truck, a 1999 Dodge Ram, on the side of the road and has a handmade sign that says, “Stop and Talk with Senator Jeff Smith.” There needs to be more examples like that. What Jeff Smith did didn’t cost a lot.

The problem with consultants is they don’t see any way to make money out of this unless it’s a TV ad. So they’ll come in and do your TV ads for you and get their 15% commissions.

What else needs to be done? Going out and training local people to knock doors—that’s a minimal cost. Buying some radio spots year-round. Doing more with social media and weekly newspapers, although there aren’t as many of those, that’s going to cost a little bit.

Instead, the Democrats’ current approach to rural has been, “Well, the election’s over, let’s turn the lights off and lock the door.”

That’s not what the Republicans do. They’re going every day, 365 days a year.

Would that dynamic change if Democrats, say, held their first primaries in battleground states or in rural states?

It was a mistake to take it away from Iowa. That sent a message: “We really don’t care about rural states.” I know Iowa’s not necessarily representative of the country, but it’s a rural state, and it prizes retail campaigning, which is what the party needs. With the caucus system, candidates to have to go out and meet people in their homes, in the American Legion Halls and churches and small groups.

Barack Obama won that way. It’s not perfect, but moving it to South Carolina wasn’t the best move. If they switch it to a state like Michigan, or even Illinois, which is more representative of the country, the temptation would be to do more TV ads.

TV has to be part of the equation, but Iowa forces candidates to have a ground game and person-to-person contact, which is ultimately the key to doing better in rural areas.

Is it true that what campaign consultants earn is dependent on how much money they decide to spend on TV ad buys?

It varies, but consultants typically get 10% to 15% of the TV buy. If they spend a million dollars on TV, then they get 15%, $150,000. That creates an incentive for consultants to tell you to use TV.

People might not remember Paul Wellstone. He was a Senator from Minnesota with a progressive populist appeal in rural areas. His TV guy was named Bill Hillsman. His theory was that if you do a really creative TV ad, you don’t need to run it a million times because people will remember it.

Nowadays, they run this mind-numbing bullshit on TV that you see 50 times a day. It drives the cost up and the fees up.

Trump had better ads this time, honestly. I don’t remember Kamala’s ads. I don’t remember Hillary’s ads. If you see Bill Hillsman’s work, you don’t need to see it 10 times a day to remember it. But Hillsman was frozen out of the Democratic Party because he represented a threat to the system. And that’s why we have what we have. We’re either about winning elections or making the consultants rich.

How do you think Democrats can best bridge the divides among the electorate?

The Democrats have basically kicked away a key component of the New Deal coalition.

I live in an area where a lot of factories have gone overseas and we lost jobs. I remember listening to Trump on satellite radio in 2016, and he was talking about trade and the disaster of shipping jobs overseas. And I’m thinking, boy, he’s going to appeal to a lot of people with that message.

But it’s not just economics anymore. It’s culture. It’s our whole attitude and how we talk to people.

Too many Democrats have a condescending attitude and basically call people stupid if they vote for a Republican or a Trump-type candidate. That’s the message that was delivered this time to Black voters. We’ve lost an ability to really listen to people and meet them on their own terms.

Here’s exhibit A of how damaged the Democratic brand is in rural America: look at what just happened in Missouri.

Missouri passes two statewide referendums, one on abortion rights and one raising the minimum wage. And several years ago, Missouri defeated a right-to-work amendment. Now, if you’ve got a candidate in Missouri like Lucas Kunce with those same policies, who is running for the Senate against Josh Hawley, how does Kunce end up with only 42% of the vote?

Don’t tell me voters in rural areas don’t back progressive policies. They do. But look at the numbers. When you put a D next to the name, they vote against it more. Why? Because they don’t like Democrats.

And I think it’s got a lot to do with the attitude of the party and a lot of these cultural issues that we’re forcing down people’s throats. I talked to so many people who said they didn’t really like Trump, but the Democrats have driven them away.

So, what is to be done?

Part of the solution is going to be remaking the face of the party. If the Democrats are going to rise back, it’s going to have to be local. The Democrats are going to have to go out and organize again and find people locally to be the face of the party instead of Nancy Pelosi or Kamala Harris or Joe Biden. That’s where it’s got to start.

One of the keys to people winning in rural areas is nonstop door knocking. In our 2017 report, people that won told me that not only is door knocking the best strategy to get to know people, it also provided inoculation against negative attacks.

When somebody hits you for being the antichrist or whatever in a TV ad, people would say, well, I know this guy. He came to my door. The key is to start from the ground up and make the effort year around.

Former congresswoman Bustos used to do a variety of events. As a member of Congress, it’s hard to go knock doors. And town halls became circuses with the right wing disrupting them. So she came up with new ideas.

One idea was a supermarket Saturday where she would go stand in supermarkets and talk to people. She also did job shadowing where she would go work different jobs and learn about people and how hard they work.

When’s the last time somebody did that?

I admire Jeff Smith up in rural Wisconsin. He’s making sure he stays in touch the old-fashioned way with people, face to face. We’re losing that through social media.

One of the biggest surprises in the last several years is a congressman from Silicon Valley who connected with me.

His name’s Ro Khanna. Here he is, an Indian American representing Silicon Valley. He took an interest in what was going on out here and wanted me to set up meetings the last couple of summers in factory towns in the Midwest. He flew out on his own dime. He wanted to hear from these people. And he listened.

This guy really gets it. He gets it better than a lot of Midwestern public officials do.

He came up with an idea of investing in American steel plants and putting them in these towns like Johnstown, Pennsylvania, or Youngstown, Ohio, that have suffered. He calls our trade policies one of the biggest avoidable policy mistakes Democrats have ever made. I agree. And we need to own up to it and try to invest more in these towns, places where people feel left behind. So Ro Khanna is someone I admire.

Believe it or not, someone who is never mentioned is Tammy Baldwin. She did well in rural Wisconsin in both of her elections. That was a shock to me.

I’m thinking, this woman is gay and you never hear her name. Did anybody ever go to her and ask, “Senator, what did you do? What’s the secret sauce in rural Wisconsin? How did you do so well?”

Prior to becoming chair of the Democratic National Comittee in 2021, Jaime Harrison was a corporate lobbyist. In 2020, Harrison, who has never held elective office, raised more than $130 million in his challenge to Republican Sen. Lindsey Graham and lost by more than 10 percentage points.

No. Instead, the media was chasing around Stacey Abrams, Beto O’Rourke and Jaime Harrison. And I’m looking at the numbers. They got killed in rural parts of their states.

But the media portrayed it as if they did really well. They didn’t. Not unless you define 30% of the vote as doing really well.

How do you see the current constellation of the Democratic Party—on the one hand the Clinton free traders who gave us NAFTA, and on the other those who are more radical on social issues—relating to rural America and their policies?

I don’t look at it that way. I look at who wins. Do you win or lose? I don’t want to hear about somebody who agrees with me on everything but loses. The Democrats need to rise above these ideological battles. If somebody needs to be pro-gun, pro-life and win a rural district, the party should welcome them. The party says it’s a big tent. It’s not. You’re not going to do well in rural areas unless you welcome candidates that may not agree with you on a lot of these issues. Identity politics is killing the party. I know that won’t make me popular in a lot of places, and that’s fine.

If a far-left progressive wins in a rural area, then great. Learn from it, see how it adapts to your local area. If the party can’t welcome diverse views, then you’re looking at semi-permanent minority status. A lot of people don’t want to hear that.

What do you think of Rep. Marie Gluesenkamp Perez in Washington State?

It looks like she’s going to win again. And Jared Golden won in Maine. There are a few Democrats left who represent rural areas. A lot of the ones Bustos and I talked to who won in 2016 have now lost. You can’t build an enduring majority just winning cities, university towns and some progressive suburbs.

Nobody inside the party wants to hear this message.

That Senate race in Nebraska was interesting. I can’t wait to get the final numbers. That guy, Dan Osborn, ran without a D behind his name, and he outperformed the other Democrats on the ticket by six or seven points. There’s something to be learned there, if the party’s willing to listen.

Last year, I was listening to a session with some Democratic group, and they bring on this guy, and he’s trying to coach candidates in rural areas how to talk to voters. Think about that: teaching rural candidates how to talk to rural.

If a candidate came to me for advice and said, “Robin, what should I say to voters?” I’d say, you’re not knocking enough doors. Go knock on some more doors. You’ll be okay. Listen to what people say and how they say it.

The pollsters come in and test language to see if it resonates, and use that language in TV ads and print pieces. “Build Back Better”? Are you kidding me?

Here’s an idea:Deep canvassing. Why don’t we do more of that?

There’s not much money to be made by political consultants in canvassing, is there?

Bingo. That’s why it won’t happen.

People, not just rural voters, but all voters, have had it with the poll-tested language. That’s part of why Trump was popular—as well as Bernie Sanders. When people heard Bernie Sanders speak, they knew he didn’t have a pollster whispering in his ear. And Dan Osborn in Nebraska—watch him talk. That’s not a guy talking with poll-tested language. He came across as authentic, and that’s what people are wanting.

When I hear Kamala talk I didn’t know what she was saying. Hillary, I think, fell victim to that, as well. There’s value in just talking directly to people. As much as I disagree with Bill Clinton on NAFTA, he had that gift of being able to communicate complex policy issues to voters in a way that made sense.

I live out in the country. I have neighbors here who are Trump voters. I listen to them, how they talk. It’s not how the politicians talk.

My next-door neighbor is a Trump voter. He’s very conservative, a gun owner. We get together and have a beer on his porch about once a week and talk. When I go out of town, he comes over, checks my house out, helps himself to a beer. That’s the way it should be, but we’ve gotten away from that.

As a society, we’ve got to try to get that sense of connection back where politics isn’t everything. I remember a time when politics was boring, and I wish we’d get back to that.

Jaime Harrison, who is stepping down as the chair of the Democratic National Committee, is one of those Democrats who ran for elected office, the U.S. Senate in South Carolina, and lost and is now a rural expert. Do you have any advice for whoever the next chair of the DNC is on how to approach rural voters?

Jaime Harrison is a nice guy, but a lot of money was sent down to South Carolina, and he got clobbered. The Democrats, every cycle, have somebody they fall in love with and spend an inordinate amount of money on, and they don’t even come close.

If the DNC is serious about trying to do better in rural America, find somebody who actually won out there. The motto needs to be that of the old Oakland Raiders football teams of the 1970s, when Al Davis ran them. His motto: “Just win, baby.”

…

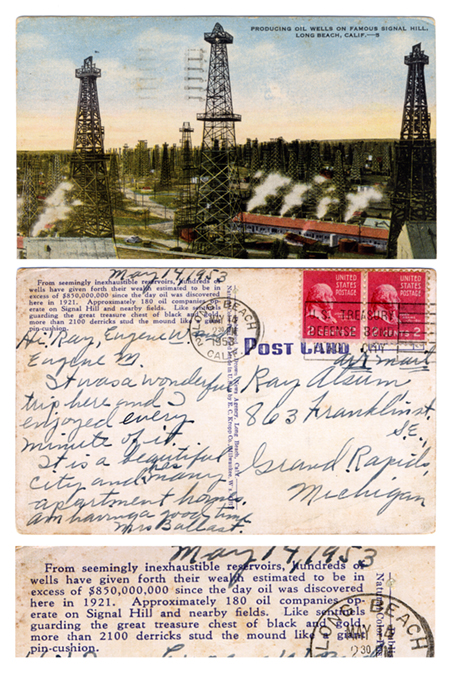

Oil in them there hills! Signal Hill and Beverly Hills no less!

By Peter Olney

When I took up residence at the end of August on Signal Hill to work the Congressional elections in Orange County I had little knowledge of the history of this little city of 2.2 square miles completely surrounded by the City of Long Beach. I had heard of Signal Hill because of the infamous police murder of CSULB football player Ron Settles in 1981. The fight for justice for Ron Settles was ongoing in 1983 when I arrived in California and worked in Long Beach on a battle to keep Long Beach Community Hospital open. Finally in 2022, over 40 years later, the City of Signal Hill issued a public apology to the Settles family for Ron’s death.

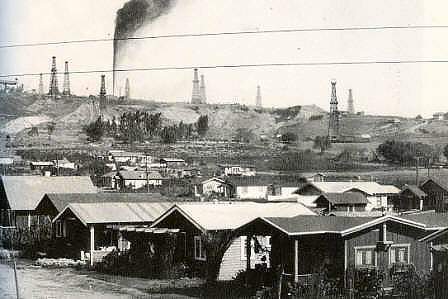

But living on the Hill has pushed me to learn more about the history of the whole LA basin. It is often forgotten amid the glitz of Hollywood that LA is the largest urban oil field in the country. Oil was discovered in the 1890’s and powered the early economy. Oil continues to be pumped in many parts of LA County and the industry recently bristled at Governor Newsom’s support for legislation that would require capping wells near residential areas.

Oil was discovered in 1921 in Signal Hill and huge geysers some 300 feet high were not uncommon. The City was incorporated separate from Long Beach in 1924 to protect the oil barons from regulation and taxation. Oil was discovered in Venice, California in the 1930’s and even to this day “pumpjacks” can be seen dotting the LA landscape in often the most unexpected places. Several wells in Beverly Hills are camouflaged by cosmetic tower structures. In the long running 1960’s TV sitcom Beverly Hillbillies Jed Clampett struck oil in the Ozarks in Missouri and moved his family to Beverly Hills. Turns out there is an active oil well next to Beverly Hills High School

Signal Hill features an amazing Promenade Park on its summit that has some of the best panoramas of the LA basin. It is one of the unknown gems of SoCal with views that rival anything from Griffith Park or the Getty It also features some crazy juxtapositions of oil pumps with luxury residential housing and retail businesses. You can eat excellent food at Curley’s Café on Willow and sit outside under a parasol as a silent pumpjack brings up more black gold.

My good friend Neal Sacharow obtained some vintage Signal Hill postcards online and discovered even more at this link.

Now he has staked out his camera on the Hill and captured some current images of this little corner of the Los Angeles basin

…

The Grassroots Electoral Movement Reshaping Rural Politics

By Mason Adams - Barn Raiser

This story was originally published by Barn Raiser, your independent source for rural and small town news.

In many rural areas, races go uncontested. That’s changing in 2024 thanks to grassroots efforts to contest every election

Wenda Sheard became a candidate for public office not because she thought she’d win, but because nobody else was willing to run.

The self-described grandma, attorney, former teacher and trained mediator is running for state representative as a Democrat in a rural district near Athens, Ohio. She’s running for an open seat after her representative, Jay Edwards, a Republican, reached his term limit. The district’s partisan tilt—Edwards regularly won by a 60/40 split—scared potential Democratic challengers away. After a trip to Guatemala during which she saw widespread protests against the government’s efforts to overturn the presidential election there, Sheard came back fired up and filed to run for office the Friday before the state deadline in December.

“We have to contest every race,” Sheard says. “Otherwise, instead of elections, we have coronations.”

Sheard is one of a growing number of progressives across the United States whose work is supported by a network of political groups targeting small towns and rural communities. These organizations vary in their structure and tactics, but they all intend to generate enthusiasm and spur engagement from political progressives in areas the Democratic Party given up on since 2000.

Many of these rural places were once an important part of Democrats’ coalition, but they’ve trended Republican over the last generation. That trend was accelerated by a GOP push to fund candidates in state house races ahead of the 2010 Census and midterm elections, which allowed states to redraw district lines for state and federal elections for the next decade. Republicans that year took control of 29 state governorships (a net loss of six for Democrats) and gained more than 690 seats in state legislatures—the largest gain for Republicans since 1928. Such wins allowed the GOP to control redistricting in 17 states.

Meanwhile, Democrats debated how much emphasis to place on rural America. Howard Dean, then-chairman of the Democratic National Committee, argued for a “50-state strategy” to bolster the party’s support in areas where it was losing races. Dean clashed with Senate and House campaign committee heads Chuck Schumer and Rahm Emanuel, who wanted to focus on swing districts. Schumer and Emanuel ultimately won out as Democrats saw more success winning suburban areas, and the Party placed less effort into winning more sparsely populated regions.

That began to change again after the 2016 election, when Donald Trump spiked GOP margins in rural America. In the aftermath, a slate of left-leaning organizations formed to organize rural communities through a variety of tactics.

According to Matthew Hildreth, the founder of Rural Organizing, and current rural vote director for the Harris-Walz campaign, the push to organize rural Democrats began years earlier, during the lead-up to Barack Obama’s 2012 reelection campaign. Hildreth grew up in South Dakota, got into advocacy and politics in 2007, and moved to Iowa in 2011. Hildreth had seen the Obama campaign run a sophisticated rural operation that was built from its 2008 push to win the Iowa Caucuses.

However, the Obama campaign is better remembered for its sophisticated approach to voter contacts. And folks drew the wrong lessons, Hildreth says.

“The problem is we’ve become over-obsessed with predictive analytics,” Hildreth says. “By 2012, digital took over all of our campaigns and told us they know this house will be Democratic, this one Republican. If you live in Raleigh-Durham and move out to a more rural area, the voter file will penalize you for moving. The assumption is a person living in rural North Carolina is more conservative than a person in urban North Carolina. That’s what we’re fighting against. There’s a whole group of people who have been made invisible by analytics. That algorithm has cost us more votes than racism.”

In 2012, Hildreth launched a website, RuralOrganizing.org, to connect rural organizers. He saw its contact list swell to more than 600,000 addresses and by 2018 was able to make it a full-time job. Rural Organizing built out multiple operations that included a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, a 501(c)(4) social welfare organization and a super PAC to spend money on elections.

Rural Organizing’s (c)(3) nonprofit is focused on flipping stereotypes about rural areas.

“So much of what happens in small towns is decided in places other than those small towns, whether it’s state capitals or Washington, D.C.,” Hildreth says. “Rural people solve local problems. Rural folks know what their communities need—the solutions to economic decline, population loss, opioids and all the things should come from rural folks.”

The (c)(4) leverages lobbying and grassroots activism to press for rural-centric policies, including the RECOMPETE (Rebuilding Economies and Creating Opportunities for More People to Excel) Act that authorized more federal funding for economically distressed communities. Other priorities include the Child Tax Credit, health care, child care and lowering the cost of living.

Finally, the super PAC has distributed over 62,000 rural-related yard signs across five battleground states ahead of this year’s presidential election, including non-partisan issue-only signs, Harris/Walz signs, and Senate signs to support Democratic incumbents Jon Tester in Montana and Sherrod Brown in Ohio.

In September, Kamala Harris hired Hidreth as her rural engagement director. Campaign officials said his goal is to trim Republican margins in rural areas, which in highly-contested swing states like Arizona, Georgia and Pennsylvania could be enough to tip the state in the 2024 election.

‘We need someone on the ballot everywhere’

Other organizations take a different approach. Contest Every Race recruits candidates in races that otherwise would be uncontested, a feature all too common in rural politics. The group launched in 2018 and has recruited or helped support more than 7,500 down-ballot candidates in 45 states, says executive director Lauren Gepford. Contest Every Race primarily targets candidates at the local level for offices that often prohibit party labels.

“The majority of the candidates we’ve recruited have been in nonpartisan races,” Gepford says. “We start by getting in touch with state and local Democratic parties to get their analysis of which candidates are on the right or wrong side, generally which ones are progressive and they support.”

The group’s working theory is based on the idea of “reverse coattails”—that supporting progressive candidates to contest more county-level, down-ballot races will lead to better margins for Democrats at the top of the ticket.

In recent years, Contest Every Race has turned its attention toward school boards, which have been targeted by conservative activists and so-called “parents’ rights” organizations like Moms for Liberty and Parents Defending Education who want to influence curriculum, restrict books in school libraries and otherwise set school policies. Contest Every Race is also working with candidates for state legislatures across the United States.

“This is the first time I’ve ever run for office,” says Rick Delaney, a Democratic candidate in northwest Arkansas running for the state House of Representatives. “Contest Every Race is what spurred me along. We need someone on the ballot everywhere.”

In Ohio, Victoria Maddox grew increasingly frustrated over increasing costs and the U.S. Supreme Court’s reversal of Roe v. Wade.

“I wondered why our representatives are not doing anything, and then I did some research and realized, ‘Oh, because they’ve been in office for 50 years, and there’s no one running against them,’ ” Maddox says. “If I’m not running, I’m a bit of a hypocrite.”

Contest Every Race also worked with Wenda Sheard, the Ohio State House candidate near Athens.

“I went into the race thinking I’d simply be a name on the ballot,” Sheard says. “Then, I realized people were excited.”

Since entering the campaign in December, Sheard’s been on the go, doing all the things it takes to run a campaign. She knocks on doors, speaks to groups, seeks endorsements, raises money.

Regardless of the outcome, Sheard says, “I’m winning. I am winning because all of my people, everyone who talks about my race and other races — we are providing hope, we are providing a choice, and we are informing voters.”

But she’s also learned some hard lessons about campaigning.

“It’s sad,” Sheard says. “I’ve learned you need money to run, and the people most likely to win are the people who have the rich people supporting them. Most of the people the rich people support are the people continuing making sure they’re rich, who will pass policies that will continue benefits to the wealthy.”

Contest Every Race’s Gepford says that’s a common sentiment.

“We’ve more and more heard, ‘I was excited to run but didn’t receive any support when I was running,’ ” Gepford says.

So far, the group has relied on local and state party committees to fund candidates it helps recruit.

Down-ballot races get a boost up

Although many groups offer support in the form of phone banking, canvassing and other in-kind contributions, most don’t offer direct financial contributions for anything other than hotly contested races in seats considered flippable and those in battleground states.

Determining how much financial support rural candidates have received versus those in metro areas is tricky, both because of the lack of clarity in how rural areas are defined and because of variance in cash contributions and in-kind support. Every State Blue has funded 121 Democratic candidates in statewide races in Missouri, Ohio and Tennessee through mid-October, beginning with those who have the least resources, according to Executive Director Michele Hornish.

One of Every State Blue’s affiliate organizations is Blue Missouri, which concentrates on financially supporting rural candidates regardless of competitiveness.

“Just last Friday I was on phone calls all day long, we gave away $173,000 to 43 down-ballot candidates in Missouri,” says Blue Missouri Executive Director Jess Piper. “We fund the neediest first. We call it the bathtub method: we start from the bottom and fill it up. Because we did that, there’s no Democrat running in any state or state senate race with less than $6,500. It’s a massive shot in the arm to the reddest, the most rural, the most difficult districts in Missouri.”

Piper joined Blue Missouri after her own experience as a candidate in 2022, when she left her job as a teacher to challenge an otherwise uncontested state representative Jeff Farnan. Although Piper lost the election, she raised $275,000. “It made a light click on for me,” she said. “I know money can’t buy a race, but it sure does help a message get out.”

Today, Blue Missouri has built a network of nearly 900 donors who make monthly donations. The organization holds monthly meetings with candidates and party nominees, and builds them up with campaign contributions—more than $550,000 in Missouri since the organization was founded in 2017.

Importantly, Blue Missouri does not base its contributions on a race’s competitiveness. “The way we do things just flips everything on its head,” Piper says. “We focus on nominees who are in really tough places to get them to run and hopefully build a bench.”

It will take Democrats longer than a single election cycle—much longer in some cases—to start winning back rural districts they’ve ceded for the last decade-plus. Building a bench of candidates and providing them sustained support is a key part of that, Piper argues.