Getting Ready to Fight Mass Deportations (or Whatever Comes Next!):Marshaling Forces to Defend the Haitian Community

By Jeff Crosby

As the Trump administration begins its assault on immigrant communities, it’s crucial that the left organize and get in formation now. We offer this as one example of what that work can look like.

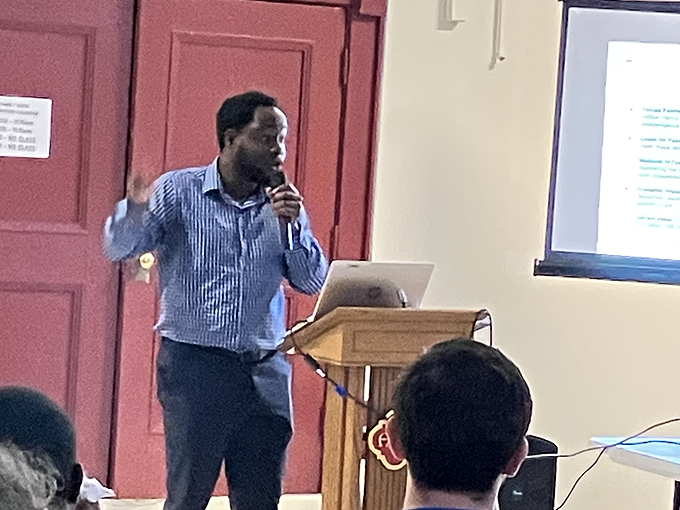

In early December 2024, the New Lynn Coalition and the North Shore Haitian Association rallied an event to counter the racist anti-Haitian lies of the New Confederacy, welcome the Haitian community and direct that community to resources they might need, and begin to coalesce the united front against mass deportations. Initiated in response to Vance and Trump spreading hateful lies about Haitians “stealing and eating cats and dogs” in Springfield, Ohio, it took on a broader significance after Trump won the presidential election. Our goal was to draw a minimum of 50 or 60 people, Haitians as well as people from the broader community. We met that and more with about 100 participants. It was a success—a strong start.

The New Lynn Coalition is made up of over a dozen organizations working together to build a permanent working-class pole in our city around economic, political, and cultural issues—a 12-year-old independent political organization uniting many of Lynn’s diverse working-class communities. The North Shore Haitian Association was formed over a year ago to advocate for the growing Haitian population on the North Shore of Massachusetts.

A powerful welcome in English and French from the President of the New Lynn Coalition, a Congolese migrant, struck home: “I am African! We welcome you to help us build a New Lynn and its united working-class majority, not two Lynns. We don’t care what language you speak, where you come from, the color of your skin, how you worship, or who you love. We are with you in solidarity and will not tolerate scapegoating any of our peoples and will always fight white supremacy and fascism.” This is the basic line of the New Lynn Coalition.

The North Shore Haitian Association welcomed people as well, provided Haitian food (which was well-received, and that is an understatement!) and asked us all to call our congressman to stop any military intervention in Haiti, respect the constitution of Haiti, and stop the flow of arms from the US to the gangs/paramilitaries.

Understanding US Imperialism’s Impact on Haiti

Migration cannot be understood outside the context of US foreign policy, and we centered a presentation on Haitian history and its domination by France and then the US. The main talk by the North Shore Haitian Association described:

- The independence war in 1804 and the French imposition of $21 billion (in today’s dollars) as “reparations” for the freed slaves (that is, ransom to free their own bodies from those who enslaved and profited from them), which has confined the country up to today.

- US support for the bloody Duvalier dictatorships (Papa Doc and Baby Doc, father and son)

- The overthrow of Jean-Bertrand Aristide in 2004, the first genuinely democratically elected President of Haiti, and his forced exile to the Central African Republic.

- The current domination by the CORE group, set up by foreign powers without a single Haitian, and the police force from Kenya.

- The funding of the gangs/paramilitaries—highlighted in mainstream news coverage—by the Haitian elite. Many of that elite are also US citizens, like Gilbert Bigio, the richest man in Haiti, who resides in Florida.

Unions and churches have asked for copies of the presentation to continue the political education of their members.

Uniting Against Deportations

We targeted three sectors for support that we believed were essential and likely elements of building a united front against mass deportations: communities of faith, labor, and local elected officials.

A representative of the Essex County Community Organization, which includes churches and temples on the North Shore, spoke of the Haitian community:

“Organizing across different backgrounds is a way to live out our faith. It’s an opportunity not just to fight for the world we want but to practice living in the world as God intended it to be…As people of faith, we are called to walk alongside them…When we stand together, we embody the power of community and faith. Regardless of where we come from, we all need the same things—to be safe, to be seen, and to see our families thrive.”

A rabbi from Lynn shared a teaching from Jewish tradition that speaks to the moment we are in and the need for solidarity:

“‘God gathered the dust [of the first human] from the four corners of the world [so that] every place that a person walks, from there he was created and from there he will return.’ This ancient text shows us that migration is not new—migration is human, and has happened as long as there were humans on this earth…I am the granddaughter of a Holocaust survivor…It is our obligation to create a world that will accept us all no matter where we end up. And that starts by accepting everyone here in Lynn…Our safety is tied up in one another’s safety. We all belong here together.”

The corporations are falling all over themselves to make peace with Trump – even those who said they would stop funding him after January 6, and who claimed to oppose him before November 5. Capitalists will always follow the money. The North Shore Labor Council responded:

“The labor movement has a particular obligation to fight back against this government tyranny. We may be some of the last genuinely democratic institutions left in the country. We won’t just be on the front lines, we’ll be some of the last lines of defense. We can provide legal support to our members to give them a pathway to citizenship, we can file unfair labor practice charges and go on strike if management invites ICE into the workplace, we can provide aid and be there when disaster strikes and we’re at our lowest, and we can give a voice to working people as our elected leaders abandon us and refuse to listen.”

A Haitian shop steward from SEIU 509 spoke of the resilience and power of the Haitian people. The President of the Lynn Teachers Union, in tears, promised:

“As a Lynn teacher and local leader, one of my chief duties is to ensure the health and safety of all my students. And that includes protecting them, not just from harmful and false claims about who they are and where they come from, but to promote and praise my students for everything they have to offer to this world. The Lynn Teachers Union stands in solidarity with our Haitian brothers, sisters, and siblings.”

The entire Lynn City Council, the Mayor and our two state representatives signed a powerful statement written by New Lynn, which was read by a Haitian/Dominican City Councilor.

“Our city has a proud history of fighting for freedom and inclusion…We welcome migrants and commit to using every available means to prevent the harassment and deportations of migrants and their families, including Haitians who have faced racist dehumanizing insults from high-ranking government officials including President-elect Trump and his VP JD Vance as well as openly fascist groups across the country. The Mayor, the Lynn City Council and State Delegation will work to unify all parts of our community, from the public schools to our businesses and labor unions, to ensure the safety and protection of all our people. We are All Lynn.”

Finally, two Dominicans spoke. This carried special weight due to the history of conflict between Haitians and Dominicans, who share the island of Hispaniola. The long-time Dominican dictator Trujillo “othered” Haitians as a scapegoat for his own oppression of the Dominican people. More Haitians are being deported from the Dominican Republic today than from the United States. A community leader from New Lynn partner Neighbor to Neighbor pledged her support, and a student from nearby Salem State University denounced the attacks on Haitians in her own home country as well as in her new home, the United States. Her remarks, as well as the introductory words in French and especially the history of Haiti, received the strongest response from the Haitians present.

Strengths and Weaknesses of the Event

“Giving a hug to the Haitian community” in a time of fear and oppression was successful. We received good coverage in the local daily paper. It weighs on you when all you hear is how awful your country is: “shithole country,” “eating dogs and cats,” gangs and violence, again and again. One leader of a Haitian group roamed the room, showing videos of the countryside, so those of us who had never been there could see how beautiful the country is – as the history introduction put it, “the most mountainous country in the Caribbean, a hikers’ paradise!” We also provided information tables with help with legal issues, housing, and community gardening. New Lynn is offering free classes in computer basics and English in Creole in our Lynn Community Engagement Program, or “night school.”

The depth of ties New Lynn has built over the last 10 years enabled us to rally representatives from the three sectors we targeted within just a few weeks in response to the “cats and dogs” libel. We showed how the issue of “immigration” is tied to US foreign policy and must be explained that way.

We had less participation from local Haitian churches than we had hoped. Haiti is a devout country, dominated for most of its religious history by Catholicism. More recently Pentecostal and Evangelical Protestantism have grown rapidly, as in Central and South America. Historic African religious influences like Voudu have had syncretic impacts on all of these. It is not possible to organize with that community without respecting that background.

Too late we realized that our Sunday afternoon start time, which we thought would coincide with the end of services, was in fact too early, especially since pastors spend a lot of time after church welcoming and chatting with parishioners. The program was held in the basement of a Catholic church, and we drew some people by standing in the parking lot with signs welcoming people to join us. It also may be that the fear that has pervaded the Haitian and other migrant communities inhibited their participation.

The labor participation was stronger than expected, with Haitian union leaders from SEIU and the Boston Teachers Union as well as new Haitian members of UFCW and IUE-CWA joining non-Haitian union members. It may be that union protection made these Haitian workers more willing to step out than, for example, an average parishioner at the Pentecostal church. In any case, Haitian workers are a growing part of the labor movement here and are likely to be a powerful voice against Trump’s xenophobia.

At the same time, we do not suffer from the misunderstanding of much of the left that “immigrants” are somehow a solid progressive bloc. Lynners from Congo and Haiti, the Dominican Republic and Pakistan, all reported some family and friends who were supporting Trump. Reasons given were often abortion and the economy, but also included random false stories, even that Trump had promised to get Pakistan’s Imran Khan out of jail. Many are convinced that Trump will not deport otherwise law-abiding undocumented folks. And they don’t want criminals from whom they suffered in their home countries to follow them across the border to the US any more than any other working-class people do. We expect conflict within and between immigrant communities in our city as well as between them and the power structure at local and national levels.

In retrospect, it may have been wise to reach out to small businesses. The Haitian small businesses depend on that community. Some fear that they will be deported so someone else can steal their business, as happened to Jews in Germany. The most influential people in a new and growing immigrant community tend to be clergy and small business people. They have been strong allies on issues such as winning driver’s licenses for undocumented people. On the other hand, when we added “Ceasefire in Gaza” for our May Day march, we lost the support of some Guatemalan evangelicals. Both sectors are likely to be strong allies against deportations, especially if Trump actually moves to mass deportations.

Looking Ahead

We concluded the meeting by asking people to “Stay Ready” for whatever comes next, like the nickname for the powerful bench of the Boston Celtics. For non-sports fans, the bench is those players who are back-ups, not starters, for the team. They have to be ready to play, never knowing when the call will come or circumstances. We don’t want to be caught off balance from whatever Trump does, and he is deliberately unpredictable—that’s his M.O. But we could have been clearer on the push to make the calls the North Shore Haitian Association asked us to make. We adjusted following the event to set a call day with their message, but that is harder after the fact than if the last thing we had said, with a flier, was “Call the Congressman on Friday!” and perhaps did a role play of the call.

In the main we accomplished what we set out to do: reach out to and comfort the Haitian community, deepen our relationships there, do some clear anti-imperialist political education, and set the table for whatever comes next.

We’re ready.

…

Will the media beat Trump at censoring itself? Industry trends suggest it’s already happening.

By David Helvarg

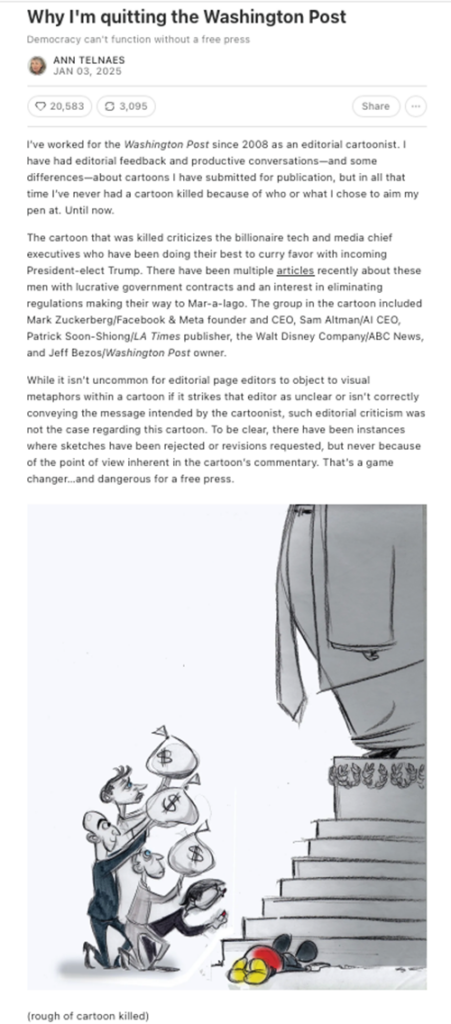

Two billionaire publishers, the Washington Post’s Jeff Bezos and the LA Times Patrick Soon-Shiong, blocked their editorial page editors from endorsing Kamala Harris in the presidential election. If you believe the Washington Post’s slogan that ‘Democracy Dies in Darkness,’ their owner was the first to switch off the light.

Then, Soon-Shiong blocked an editorial asking the Senate to perform its constitutional duty to provide advice and consent on Trump’s cabinet picks. Now ABC News (owned by Disney) has agreed to pay $15 million in a settlement of a Trump defamation lawsuit plus $1 million in attorney fees because George Stephanopoulos said on his Sunday show that Trump was found liable for the ‘rape’ of writer E. Jean Carroll. Actually, he was found guilty of ‘sexual abuse’ because a New York civil jury believed her claim that he forced his fingers into her vagina but was uncertain if he also used his penis. New York law states only penile penetration is considered rape. This was a case ABC could have clearly pursued in court but made a political – really a business – decision not to. Trump is now suing the Des Moines Register and their pollster for a pre-election poll suggesting he would not do as well as he did in Iowa.

It seems likely that top-down self-censorship of the mainstream media may preempt expected legal attacks on critical coverage from the incoming administration that has been promised by Trump’s pick for FBI Director, Kash Patel and by Trump himself.

This is in large measure the result not only of right-wing ascendency in national politics but of a long-term decline and corporate consolidation of American journalism. Also, helping to undermine the public’s ability to stay informed is the rise of the internet as a selective news source that generates revenue by reinforcing existing biases through its algorithmic infrastructure that aims to keep viewers online longer. While billionaire tech ‘bros’ embrace Trump, working journalists are portrayed as part of an elite that Trump has defined as ‘enemies of the people’ mainly for exposing the machinations of those in power including the president-elect.

I’ve worked as a freelance journalist for half a century. According to a study by the job recruitment company Zippia there are close to 15,000 freelance reporters working in the U.S. whose demographics skew slightly more white and female, than the nation as a whole and who earn an average of $61,000 a year compared to full-time journalists who average $86,000. Freelancers make up a third of the 45,000 working journalists in the U.S. so figure your news is coming not from some media “elite,” that promote “fake news,” but working people like myself covering wars, politics, pandemics and the climate emergency.

Earlier in this century I got to train colleagues in Poland, Turkey, Tunisia and elsewhere on environmental reporting. I remember in Turkey going over some of the basics of investigative reporting including always keeping good notes and tapes stored and dated including by year as some stories become beats that can continue over a lifetime. Sergei Kiselyov, a Ukrainian colleague who’d covered the Chernobyl disaster, offered an addendum, “I’d just suggest you also keep your notes and files somewhere other than your home or office so that when the police come to look for them, they won’t be there.” This tip is worth keeping in mind over the next several years. The jailing of journalists has happened too often before in this country and almost certainly will again in the near term.

Or they could just be laid off. Many of my friends and colleagues who worked in newspapers are now freelancers like myself, the newspaper industry being in a near terminal stage of collapse. This is largely due to loss of revenue to online advertising, corporate consolidation and hedge fund predation where operating enterprises are bought up, wrung out (staff layoffs focused on older higher-paid reporters doing complex investigative work), and then sold off for parts (printing presses, data-bases, real-estate). This has resulted in massive job loss. Newsroom employment dropped 26 percent between 2008 and 2020 according to a study by the Pew Research Center and continues today. I know of one Pulitzer-prize winning reporter who agreed to a one-third pay cut rather than see a second wave of layoffs further hollow out their publication.

The loss of competitive newspapers has resulted in the absence of a lot of good reporting, particularly at the local and regional level where many continue to shut down each year. Since most local TV news stations depend on local newspapers for their hard news this has also had a cascading effect on the public’s ability to access reliable information about those with and in power and how they’re wielding it from zoning boards to local corporations and government agencies. Many people have turned instead to unreliable online social media including bloggers and influencers to get their news.

The proliferation of disinformation, misinformation and incitement to hate on social media or through the use of AI fakes also raises questions about who’s left to mediate what passes for news and to sort facts from fabrication, particularly at a time when much of the public now agree with Donald Trump. An October 2024 Gallup poll found 69% of the public has either “no trust” or “not very much confidence” in the media. When I began working in 1974 over 70% of the public trusted the news media. And with some reason.

When I was covering the wars in Central America I asked my friend photo-journalist John Hoagland how he saw our role. “I don’t believe in objectivity because everyone has a point of view,” he said. “What I say is I’m not going to be a propagandist for anyone. If you do something right, I’m going to take your picture. If you do something wrong, I’ll take your picture also.” He was killed in crossfire a year later. Ironically the best recent movie on how reporters actually behave under fire and under stress is ‘Civil War’ that is set in a future America at war with itself.

With the “legacy” network news operations of ABC, CBS and NBC now under the control of Disney, Comcast and ViacomCBS, major corporations dependent on the regulatory whims of Donald Trump, and with Trump’s talk of eliminating public funding for PBS (and its ‘News Hour’) plus ‘news outlets’ such as Fox and the Sinclair Broadcast Group that owns 294 TV stations covering 40% of U.S. households, acting as propaganda arms of the MAGA movement, the likelihood of much critical mainstream coverage during a second Trump administration is doubtful even before any expected lawsuits, indictments and jailing of journalists.

To paraphrase a quote from a darker time, “First they came for the journalists and then we don’t know what happened.”

For more on this topic check out Status’ piece; “The Atlantic Editor-In-Chief Jeffrey Goldberg warns newsroom decay is how ‘democracy decomposes'”

…

LGW for PBW

By Linda Worthman

I’ve known Pete Worthman for almost 70 years, ever since his family moved him to our small suburban NYC high school (to protect him from the school where he wanted to play ball in the Bronx). His arrival was explosive. Within hours we knew more about Pete than we did about most of our other classmates, and there weren’t that many of us. We knew that he was Pete and not Paul, that he loved NY jazz and the Dodgers, played ball and ran track, and was a master of the shaggy dog story.

Pete and I were off and on friends, off and on more, and it took the two of us 10 years to figure out that we wanted to spend the next almost 60 years together.

Thank goodness we did. I’ve said it before, but in marrying Pete, I Married Adventure, the title of my favorite book in grammar school. The book had me believe my adventure would be in Kenya, seeing wildlife. But Pete was smarter than me, so when I told him I thought I’d join the Peace Corps to get to Kenya, he proposed. I instantly became smarter and accepted.

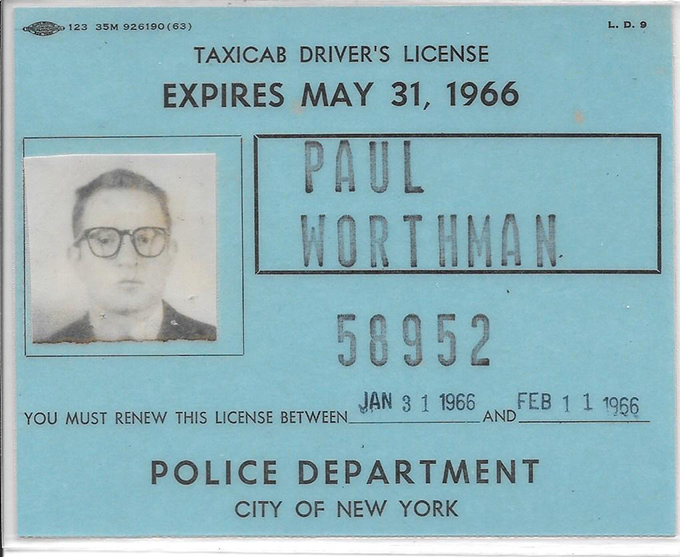

Before he explicitly joined labor activism, Pete trained for it. Gigs included treasurer, concert promoter, athlete, dishwasher, auto worker, postal worker (to the detriment of two trucks), jackhammer operator, hod carrier, taxi driver, grad student, father, professor – to name a few. He also trained to bargain contracts, by listening to his father-in-law’s interminable stories about negotiating for Time Inc. “He said, then I said…” For his first contract, his formidable research skills extended to bargaining with a reference open on his lap.

He loved research, data! data! The summer after our marriage, we were in Alabama collecting data for his work documenting black workers and labor unions in Birmingham at the end of the 19th century. Our noses were in the newspapers and city directories … and the data. Who was a miner? A puddler? Who were the black AFL Local members? (I will happily send the table of Occupations by Race in Birmingham 1900, carefully tabulated from City Directory 1901, should anyone ask.) Over and over his research skills made the difference in his approach to his work. And even much later as the technology improved so that he was offered the option over and over to switch from finger sticks to follow his diabetes, it wasn’t until he realized a continuous glucose monitor gave him !data! that he lighted up.

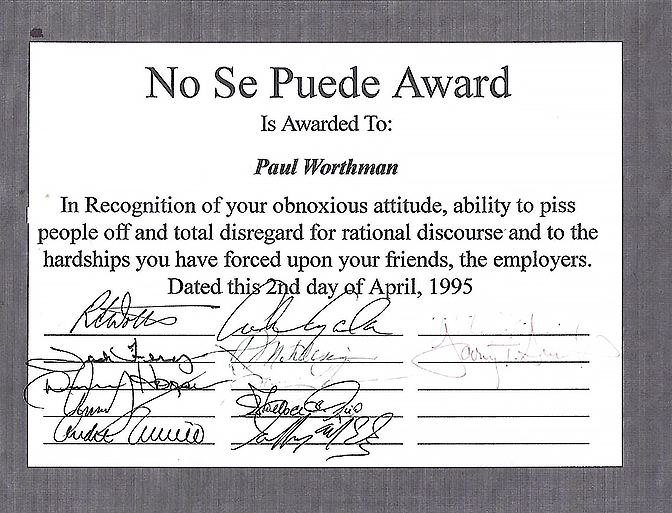

But his métier was as a labor agitator. His friends, the employers, maybe said it best with this award.

Agitate: Take Power: Bring the negotiating team in early to occupy the seats at the table that were traditionally management’s. Know more about the budget than management did. Stay and stay and stay to get the language in the contract exactly right. Wear your Looney Tunes tie. Teach.

Pete’s approach to holidays was – predictably — somewhat unique. No to his birthday, “I celebrate every day that is not my birthday!”. He liked mine because he could tease about how old I was for two months until his. As we grew older, New Years Eve was celebrated on East Coast time. Wedding anniversaries were celebrated thoroughly except the year in England when other adventures meant we forgot until a month later. Our celebrations of standard religious holidays meant bringing two cultures together for Easter, Passover, Christmas, Hannukah. Sweet. We all loved Pete’s playful approach to Christmas gifting and the family tradition of seasonal shopping at our local Pik N Save.

This year at our Christmas celebration we brought out a P&S treasure from long ago, and enjoyed the presence of our own Santa Bear.

Our own adventures I won’t try to summarize except for one or two things. Pete was an activist father. Our girls grew up strong, proud, infinitely capable because of his attention, his teaching. We knew all along they were our best and brightest adventure. And, along the way we gathered so very many good people as our friends. We are fortunate and we (yes, we) thank you.

As we grew older, we told more and more of our own interminable stories, frequently “correcting” the other’s version of history. Sadly, we will now never resolve whether it was the last spear of broccoli or asparagus I loudly coveted on Frank Gattel’s plate. But, it’s important to point out that the story of two ties already told, was not Pete’s original invention. Pete was following the lead of a classmate of ours, John Kifner of the New York Times, the one who outed the Chicago Police for killing Fred Hampton. Kiff had been told by management that they valued his work but weren’t quite sure if he fit in … Soon Kiff’s wardrobe evolved from the khaki stage to three piece suits. He carried an umbrella rain or shine. And when he was promoted from cub, he celebrated by wearing two ties. Pete was always careful about attributing his sources.

In the olden days, I normally would have passed my draft over to Pete for review. It would return tighter in many instances, and also bearing at least five new subordinate clauses. I miss them.

…

Pete Continues To Inspire Me

By Kristin Ingram-Worthman and Edward Ingram

Kristin Ingram-Worthman

Shortly after I arrived at Lin and Pete’s house, a few days before he died, Pete asked me to get the hat he is wearing, a Brooklyn Dodgers hat from 1915, from the closet so we could take this photo together. This photo, the last Pete took, is so special to me. It brings back so many memories.

From the time I was very young, Pete took me to Dodger games. We climbed what seemed like an endless number of stairs to sit in the top deck behind home plate, because as Pete explained, those were the best seats. From there, we could see the whole field. Pete always bought a program so we could keep score together. He taught me how to note what each player did using letters, numbers and symbols in tiny boxes. Even though we were at live games, someone sitting near us usually had a transistor radio, with Vin Scully calling the game, because as Pete explained, Vinny knew so much about the Dodgers, and no one could analyze plays like Vinny could. The Dodger game was also where Pete taught me not to stand up for the Star-Spangled Banner.

There are two specific games that stand out as memories. I think it was for my eighth birthday that Pete took me to the Dodger game. He told me that he tried and tried to get the Dodgers to print “Happy birthday, Kristin,” on the message board, but he couldn’t do it. It didn’t bother me because I was more than happy with what he did instead. We were sitting in the bleachers during either batting practice or fielding practice, and he yelled to Reggie Smith, a Dodger outfielder, to tell him it was my birthday. Reggie Smith looked at me, smiled, and waved.

The other game I remember was in 1988. I am almost sure it was the seventh game of the playoffs; a game I didn’t know I’d be attending. I was about to walk home from Venice High School when I saw Pete’s cream-colored Tercel. I was so excited when Pete told me we were going. It was a great game! The Dodgers won, and then went on to win the World Series!

Growing up as Pete’s youngest daughter was, as Catha wrote in her tribute, very special. As red diaper babies, the way Catha and I were raised was special. As part of my childhood development coursework, I read about anti-bias education, which is an approach to teaching with four goals, to teach young children to feel good about themselves, appreciate diversity, recognize unfairness and have the words to describe it, and then to act against it. As I read about anti-bias education was exciting because I finally had words to describe how I was raised. It was more than multicultural education. Even more exciting to me was to realize that the book I was reading from, Anti-bias Education for Ourselves and Our Children by Louise Derman-Sparks and Julie Olsen-Edwards, was written in 2009, about forty years after Catha and I were born. I feel like Pete and Lin were ahead of their time.

I have so many memories. From the time we were very young, Pete taught Catha and me the importance of political activism. Catha and I knew all the words to songs like, “Solidarity Forever,” “We Shall Not be Moved,” and “We Shall Overcome.” We went to many, many demonstrations. Some of the demonstrations I remember most were the demonstrations to make Martin Luther King, Jr.’s birthday a national holiday.

After Dr. King’s birthday became a national holiday, Pete helped me get involved with the Los Angeles Student Coalition, a group of junior high school and high school students who led protests at the South African Consulate in Los Angeles on Martin Luther King Day. One year, Pete took me to a breakfast hosted by the Los Angeles County Federation of Labor in honor of Dr. King’s birthday where Jesse Jackson was a speaker. It must have been held on Dr. King’s actual birthday, not the national holiday, because I needed a note for school. Pete suggested that I ask Jesse Jackson to sign my note so that the people in the attendance office would believe me. Pete wrote the note. “Please excuse Kristin for being absent from school on January 15. She was having breakfast with Jesse Jackson.” Pete signed it, and Jackson’s signature was right next to his.

I also have other memories related to school, some of which I will share here. Pete often drove me to elementary school in a 1965 red Volvo that he inherited from Lou, Lin’s dad. The reason I remember the car so much is because it had a loose solenoid, so in order to start it, Pete would have to hold on to the front fender and shake the car. On the way to school, sometimes Pete would talk to me about how cars work. He would tell me how the pistons went into the cylinders, lit sparks, and the wheels turned. As Pete drove, we listened to jazz. Pete would talk to me about the musicians and the instruments they played. He taught me how to identify instruments by the sound they made. He showed me that a trumpet could make a different sound if the musician used a mute.

In 1984, my classroom had a bulletin board of the candidates running for President of the United States. It included Walter Mondale and Ronald Reagan. I remember asking my teacher why Jesse Jackson’s picture was not included on the bulletin board. She told me the bulletin board only included the “major candidates.” When I told Pete about that, he went to school to talk to the principal, an African-American woman who had also been my first-grade teacher. When I was in junior high school, Pete and I went to a meeting to hire a new history teacher. I learned about affirmative action as Pete argued with other parents, insisting that it was not only important to hire a non-white teacher, it was the law.

When I was in high school, I struggled with the advanced math classes I took. Luckily, however, I had Pete to help me. Pete was very skilled in math and would spend what felt like hours helping me. My teacher would sometimes invite me to share the strategies Pete taught me to help other students who also struggled. Pete also taught me how to write a research paper. Together, we wrote a paper on the origins of racism.

Pete’s activism was not limited to attending demonstrations or his work with unions. When I was in high school, someone stayed at our house as part of a South African trade union tour. When Luis Enrique Mejia Godoy and Mancotal were on tour, the members of Mancotal stayed at our house. The place where they were performing was a club where you had to be over 21 to get in. When Pete and I went to ask if they would make an exception, they said no, but encouraged me to get a fake ID. I borrowed an old ID of Catha’s and was able to see them perform.

Pete loved hearing about my work, both as a teacher and a student. He loved when I told stories about the funny things the children did. Right before Pete’s health took a turn for the worse, I began a child development program through the Los Angeles Unified School District. A couple of days before my first class, Pete went into the hospital for the last time. Right before Pete died, he told me he didn’t want me to take time off of work or to wallow in sorrow, but he did want me to do well in this program. I have dedicated my work in this program to Pete’s memory. A couple of weeks ago, I got my grade for the first project I turned in. I worked extra hard on it and received the highest grade possible, “innovating,” I have always worked hard and earned good grades, but this grade means so much more to me.

Pete inspired me to stand up for myself and others, fight for justice, and work hard. I miss him so much. I want to end with a story about something that happened around Christmastime that was definitely Pete-inspired. On Christmas Eve, I went to Starbucks, which was closed due to a five-day strike. The Starbucks I went to was near Disneyland and used regularly by lots of tourists, As Pete and I used to do, I spent some time talking to the two workers sitting outside. I introduced myself to them using my Starbucks name “Union Strong,” which I use to support the baristas in their struggle for fair wages. One of the women told me that thirteen of the fifteen workers voted to strike, and I congratulated them on shutting Starbucks down. Pete is no longer with us, but he is always with me.

.

Edward Ingram: My Memories of Paul Worthman

My experiences with Paul Worthman began with my relationship and eventual marriage to his intelligent, profound, unique, and one-of-a-kind daughter, his youngest daughter Ms. Kristin Worthman. I was attracted to Kristin because of her abilities to be cogent, coherent, intelligent, beyond wisdom for her age, with a political, yet kindred nature, unbelievable for a young woman of her age.

As I came to know some things about her father, mother and her older sister I knew I had stumbled into a loving family that excelled in cultivating pure genius ethics into their lives. I learned by the actions of the genius Paul Worthman, through endeavors to conquer inadequate wages and inadequate protections in the workplace. A champion to Teamsters, Farmworkers, Hospital Workers as he worked to organize demonstrations that transformed traffic in major cities and stopping freeways as tens of thousands marched in protest taking a stand for worker rights and the decency and dignity to which every human being is entitled. I recall learning he had the outstanding career credentials to be awakened at midnight by union negotiators asking his presence in the meetings and him being paid from that moment rising to the occasion, taking a cab then a plane, and as he arrived taking over the negotiations, that the opposition were seen taking Excedrin and Advil because it was going to be a longer weekend. I learned to have respect for my father-in-law, both for his intellectual prowess his understanding of the fight over alienation from the means of production, but to know the importance of life with justice, representation and civil rights.

I have found he passed this outstanding quality on to his daughters as I have come to know my wife has the amazing and unique ability to get to the bottom line in any political conflict with equity better than anyone I have ever heard of with maybe one exception, perhaps the outstanding former President Jimmy Carter.

I could go on and on about the wonderful ways in which I became involved in family gatherings, trips, outings to theme parks, but my favorites were always the nature excursions, including hikes amongst the tallest Redwoods on the planet. My life as an African-American is a multitude of life experiences, some good, others things needless to say, horrible. I am more than fortunate to have, accidentally in my lifetime, not only to meet, but spend time getting to know such a profound, vehement, masterful genius of political and social theory. As you see, I came to realize that Paul Worthman is qualified beyond mastery to fix the enigma called the United States. I am sorry for my mother-in law Linda Worthman, as she must endure, and is now without her soulmate of so many cherished years, and this affects every family member. The entire world and thus the universe will be challenged to continue without such wisdom. My father-in-law, Mr. Paul Worthman, will be remembered, and may he forever rest in peace.

…

Pete …

By Scott McCoy and Larry Hendel

Scott McCoy

I don’t have the words to express my love and respect for Pete and everything I write is far, too far, short of the mark. I’m still missing him. He was my hiking buddy, my fellow Premier League fanatic, my father in law, my friend and a life mentor. He was generous in many ways but I most appreciated the generosity with his time which I feel fortunate to have had my share. We had innumerable hikes in the East Bay hills, especially Tilden and Redwood, several baseball games from the nosebleed section behind home plate in the Oakland Alameda County Coliseum (for $2), trips to the first 3 World Baseball Classic finals and a memorable visit to Chavez Ravine. Among my favorite activities was watching early Saturday/Sunday morning Premier League games. We also shared many trips around California: Yosemite, Sequoia, Norden, Tahoe – all with amazing hikes.

Pete’s knowledge about and interest in all things athletic is legendary. I can recall first being impressed with his knowledge of all the runners in the 1992 Olympics. He called the winner most of the races and could recite all the best runners’ times from memory. Later, we started going to the CA state high school track championships and he knew all the sprinters’ times there, too. Of course, baseball was a particular love of his. I can recall many (many) warm words of advice he had for Tommy Lasorda – not Pete’s favorite baseball manager. He was an exacting fan demanding the same level of excellence that he demanded of himself. Woe to his best-loved teams. He favored Barcelona in La Liga, much to their chagrin. I can recall Pete telling me that Barcelona’s defense was “horrible” one year and Gerard Pique was a disaster in their defense. I thought they seemed pretty good. When I looked it up, I found that they were the all-time best defense for “goals against” in La Liga – the best … all-time. Still not good enough.

I enjoyed his famous sense of humor and he found humor in many situations. My favorite story is not about Pete but is, rather, a story he liked to tell. When we visited the Linda and Paul Worthman home in Los Angeles, Pete regularly took Alex to the Santa Monica Pier for a few rides at the amusement park. One weekend in Santa Monica they went to the pier only to find that the Democratic National Convention had rented the pier for the day in the run up to the 2000 presidential election. Alex was 5 or 6 and not entirely clear why the park was closed when he could see people riding the rides.

Pete: Sorry, the park is closed.

Alex: Who are all those people in there?

Pete: Those are the bosses, the rich people keeping the workers out of the park.

Alex: How can we be rich?

Much love Pete. Miss you!

Larry Hendel

Sometimes you meet someone who seems exactly suited for what he has chosen to do in life. Paul Worthman was that way.

I first met him when I was Staff Director for SEIU 790/1021 in Oakland. We were looking for someone with the skills to dissect the budgets for the Port of Oakland and Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART), two employers with loads of money hidden in the weeds of the capital expenditure budget. I contacted Peter Olney, who at that time was with the UC Labor Center, and he recommended Paul. At that point I had no idea they were long time friends and comrades. Paul agreed to help us at the bargaining table. Not surprisingly he was far more than a researcher – he was an educator, a tactician, and a mentor to the bargaining team. I learned later that he was an avid sports fan. I wasn’t surprised. He loved the fight, he loved winning for workers, he loved figuring out strategy and he loved sticking it to the boss. I remember before the internet, Paul had figured out a way to hook up cable stations around the world so he could keep up with international soccer. During the World Cup he’d get up at 3 am to watch games, even when the announcers spoke only Spanish. His appreciation of the game was such he didn’t need to understand the details of the commentary. He probably could have called the play-by-play himself.

The ultimate competition for him, of course, was the class struggle. With his passing, progressives have lost a teacher and a warrior, and I will miss him very much.

…

Anger is “the purest form of care.”

By Catha Worthman

It was a special thing to be Paul Worthman’s daughter. His “favorite oldest daughter,” he called me, and my sister Kristin, his “favorite youngest daughter.”

Pete was all the things you know – brilliant, passionate, funny, a jock (if lapsed somewhere in midlife when he was bargaining around the clock and living on coffee, fast food and cigars), anti-elitist, committed to making a world that wasn’t based on capitalism, racism, sexism, imperialism, or ecological exploitation – and not at all sentimental about it.

Pete also cared deeply about being a father, even if he didn’t go by the label “Dad.” (The reason being, Lin and Pete wanted Kristin and me to see them as people, not as their roles.) In the last month of his life, I was lucky to take time off work and spend long days again with him and Lin. One of the most moving things he said to me during this time was how he valued being able to talk with his closest friends about parenting.

He had a side of him that was deeply wise and generous, and I felt that I was seeing a part of the “real” Pete when that side emerged. It was the side that believed wholeheartedly in me and Kristin and gave us the freedom to take risks and grow, the same side maybe that helped him settle complex and contentious bargaining disputes, loved James Baldwin when he was in college, and sent us all articles that expressed deep grief about the war in Gaza — articles by Judy Butler, Masha Gessen, and one about a swim team in Jerusalem and the divisions that arose between Palestinian and Israeli kids after October 7.

He cared tremendously about Kristin’s and my political education and training. We grew up going to picket lines and demonstrations and were often given jobs to do. We knew how to ask someone to sign a petition or take a flyer just like we knew how to breathe, notwithstanding (at least my) natural shyness. When we drove around L.A. together (often heading to swim practice or a swim meet), he explained L.A.’s racially constructed geography, the history of each neighborhood and its inhabitants and workers, why there were food deserts, and it seemed like he knew everything that mattered.

Pete was for many decades my mentor and closest intellectual collaborator, maybe beginning with first grade when he coached me to ask my teacher why there were two lines (boys and girls): why not three? Breaking down categories from the beginning. When I was in fourth grade, he trained me how to do original source research in the census for a biography of Harriet Tubman. In high school, he tried to teach me how to write about dialectical materialism for a paper on Rockefeller and Eugene Debs. When I worked as an organizer and researcher in the labor movement, he collaborated with me on strategy and shared complaints about the bosses and corrupt union leaders. When I later became a lawyer, I talked with him about my most important cases before I argued them. Some of the best advice I got came from his training union members to present grievances to an arbitrator: Start with a simple, compelling sentence, “This is a case about …”

There are so many stories I want to tell, but since it’s the holiday season I’ll focus on a couple appropriate to this time of year. One is that I gave him the sweatshirt that he wore almost every day for the last three years: a picture of Marx (looking a lot like Santa) with the slogan, “All I Want for Christmas is the Means of Production.” I bought him two new sweatshirts for his last birthday, including a fresh one and one that said “I’m Dreaming of a Red Christmas,” figuring he could use a refresh. But he only wondered why I spent the money on them. (One of the things I realized about him, though, in looking at old photos, was that Paul Worthman had a stylish side earlier in life… maybe we’ll get to post those photos sometime.)

Pete could be grumpy about “bourgeois holidays,” but there were many years when he channeled the Christmas spirit, like the Marxist Santa he was. Red diaper babies though we were, Kristin and I grew up waking up before dawn Christmas morning excited to see what was in our stockings. Pete would wear the red Santa hat – like Lin’s dad Lou did before him – and hand them out. Inside were funny little items from the discount dollar store Pik n Save, all with witty comments written on the tags. Along with Christmas bathrobes, slippers, books, bikes, and other traditional items, we got gifts like the Class Struggle board game, and – my favorite – one I received as an adult, this tear apart Boss Doll the year I was non-stop complaining about my boss.

When Alex and Tenaya were born, I got to go with Pete to Pik n Save and acquire discount holiday items to try to give them the same experience. He loved his grandkids both so much, of course, and I’m so glad they both got to spend time with him before he died.

Pete was raised Jewish, although decidedly atheist and anti-Zionist as an adult, so some years we also celebrated a version of Hanukkah – a version where the workers triumphed because they collectivized their oil, because it lasted longer that way and everyone had enough when they shared.

Not a holiday story, but one I think of often as a highlight. After the Soviet Union collapsed, like many leftists Pete was depressed. Not that he had ever been anything other than a deeply critical, anti-Stalinist, but at least the U.S.S.R. represented the possibility of an alternative to capitalism and support for such alternatives around the world. But then … the Rangers won the Stanley Cup! Pete was transformed, and his spirits lifted. I saw them lifted again when the Dodgers finally won the World Series just before he died. The Bums finally succeeded, just like he knew they would if they ever listened to his advice.

While Pete was in hospice, I reflected often on the gifts I got from being his daughter. Unfortunately, I didn’t get his talent for ball sports (despite his giving me a baseball glove to sleep with when I was an infant), but I hope I can carry on his vitality, energy, passion, confidence, loyalty to his people and causes, and commitment to making a better world. I see those things in my kids, too.

And I have realized, too, I’m grateful I got to grow up close to Pete’s full expression of emotion, including anger — a gift that can sometimes be hard to appreciate, and may be one of his defining characteristics to the people who know him best. Anger, says the poet David Whyte, properly understood, “is the deepest form of compassion, for another, for the world, for the self, for a life, for the body, for a family and for all our ideals, all vulnerable and all, possibly about to be hurt.” Anger, he continues, is “the purest form of care.” There is no real wisdom, no real commitment to transformation, without anger. “The internal living flame of anger always illuminates what we belong to, what we wish to protect and what we are willing to hazard ourselves for.” If you read this essay, I think you’ll recognize Paul Worthman.. I miss him.

One last thing, although I want to keep sharing more: Pete sent me cassette tapes regularly my first year at college, when I was missing home. He passed on his love of what we could call anti-fascist music to Kristin and me, and we made this playlist. Hope it reminds you of him, too.

…

Exit, Laughing

By Gerry Daley

Irascible. Relentless. Impatient. Hilarious. Generous. Going through my inventory of adjectives applicable to Paul B. Worthman (“PBW” was the invariable email signature during our times of working for the same union), these are the ones that floated immediately to the top. But the theme that runs through all of the memories is teaching. PBW, a natural-born educator, was always and everywhere teaching all of us how to:

- Be good union members

- Be in solidarity with all workers locally, nationally, internationally

- Fight the power of unaccountable, illegitimate bosses (i.e., ALL bosses)

- Fight racists and sexists

- Fight fascists wherever we found them (see “unaccountable, illegitimate bosses” supra)

- Be leaders in a Wobbly sense

- Re-introduce the “C” word (class) to American workers, even those in show business

- Have a lot of laughs

- Teach our fellow-workers how to do all of the above

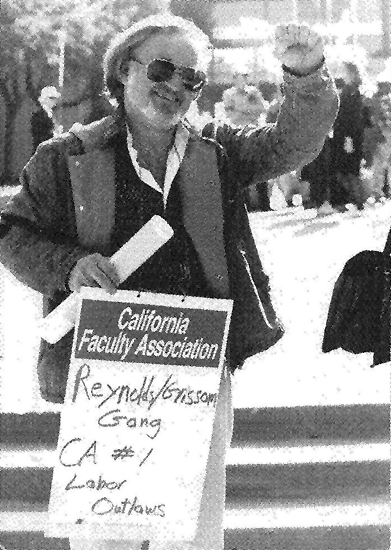

By now I can’t remember how I first met PBW – who it was that introduced us, or on what campaign we first intersected. It might have been through Lou Siegel; it might have been the mid-‘90s iteration of J For J. In any event, when I was part of a small reform movement within AFTRA’s Los Angeles Local in the mid-‘90s, I helped PBW get hired on as an organizing staffer working with both the Local and National Union. We had a lot of fun (and some modest albeit temporary victories) trying to bring AFTRA back to its radical roots.[1] When I left AFTRA for the Writers Guild, PBW took over my job as director of the AFTRA L.A. Local’s broadcast department and continued to torment the networks (and some of the reactionaries in the AFTRA command structure). When I left the Writers Guild several years later, I landed in one of PBW’s old jobs: as representation specialist at the California Faculty Association. It was fascinating to go through their archives (the Union was founded in the early 1980s, and PBW was present at the creation) and see how much of the structure of faculty rights in the Cal State University system was created by PBW and Ed Purcell. Even today, forty years later, CSU faculty still live in a house those two built.

Maybe the most fun we ever had on a project was team-teaching a class at L.A. Trade Tech in 2004 on “U.S. Working Class & Cinema,” combining most of our mutual obsessions (baseball is another one, so we managed to work in “Bingo Long And His Travelling All-Stars and Motor Kings”). Our students were a group of 25 or so workers, members of various L.A. unions from all kinds of trades, who watched some great movies, read some great articles and book chapters (gathering the readings might have been the most fun for both of us), and interacted with a stellar line-up of show-biz guest speakers. We kept looking for a chance to do that class again, but our insane workloads never aligned.

When I left CFA – I seem to use the expression “When I left [Union X]” a lot[2] – wonder what that’s about? – and went to work for the California Nurses Association, I continued to study under the master. He was always available for a consult and ready to offer creative solutions to organizing, grievance or bargaining problems, even after he retired and he and Linda absconded to their beautiful craftsman bungalow in Berkeley. Seems appropriate for a craftsman of contract language and campaign strategies.

In these dark months of the phony war period leading to the coming Anschluss of January 20, it is the laughing that I will especially remember. PBW never stopped laughing at the idiocy and pretentions of the bosses, oligarchs and fascists, and neither should we.

Syllabus “U.S. Working Class & Cinema

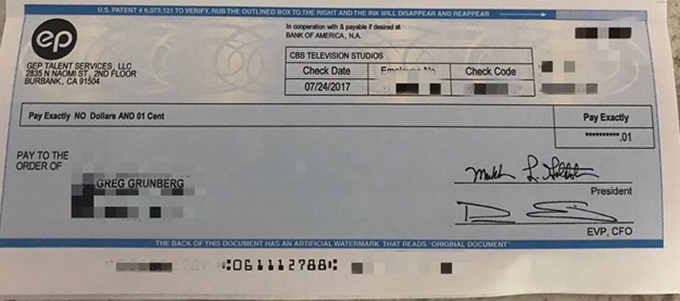

[1] AFTRA, the American Federation of Television and Radio Artists, was founded as AFRA (pre-TV) in the mid-1930s by a cadre of left performers in the radio production hubs of New York and Hollywood. It was, until its back was broken by the blacklist in the mid-1950s, the most progressive and most effective Union in show business. For example, AFTRA negotiated the first industry-funded pension in entertainment, and a 100% residual for ANY re-use of TV programs. If you want to know why so much great LIVE TV was made during the medium’s so-called golden age of the ‘50s, it was because AFTRA made it just as expensive to re-run a Playhouse 90 episode as to produce a new show, thus generating a ton of work for actors. That lasted only a short while, until SAG (under the “leadership” of its then-president– wait for it – Ronald Reagan), as part of its 50-year raid on AFTRA’s jurisdiction in TV, undercut the 100% residual with a descending scale of payments for each subsequent re-use. Thus was born the age of re-runs (and the phenomenon of TV actors receiving residuals checks of ONE CENT, see image below). For anyone interested in AFRA’s great years and the damage done by the blacklist, see Harvey, Rita Morley, Those Wonderful, Terrible Years: George Heller and the American Federation of Television and Radio Artists, Southern Illinois University Press (1996).

[2] I don’t think I got to use this expression quite as often as PBW did. Union work is notoriously precarious for shit-stirrers, and PBW’s list of one-time employers is truly impressive. But he left the kind of trail that all of us strive for: universally beloved by his members, universally hated by the employers, universally feared by timid union bureaucrats. The Wobbly Trifecta!

Paul Worthman, Presente!

By Glenn Rothner

“Who the hell is Della Bahan, and what the hell is her name doing on my brief?” Paul, then Director of Representation for the California Faculty Association, left that message for me. I had represented CFA since its inception many years earlier, in 1979. To my embarrassment, I had forgotten to tell Paul that due to the press of other urgent matters, I had asked my highly capable then associate Della for help with a brief.

Paul’s message was a not so gentle reminder that our by then longstanding relationship had blossomed because, our different but overlapping roles in the union’s work notwithstanding, we treated each with respect, as colleagues and as comrades. This minor incident was but a blip in a 45-year relationship that began as client-lawyer but grew into as continuous and fast a friendship as I’ve ever had.

I met Paul when he worked for AFSCME Council 36. My first impression was unfavorable. It wasn’t his clothes. (In fact, his determined lack of style grew on me over the years.) He seemed harried, mostly deflecting my questions with questions of his own. I wondered later whether he was testing me, trying to decide whether it was worth his time to teach me about organizing and representation strategy and tactics, in return for any legal assistance I might offer with a mere three years of lawyering under my belt. Perhaps he took a chance on me because I had spent those first few years as a lawyer with the UFW, because he had a generous spirit, or because he loved teaching.

And what a teacher. I don’t remember Paul ever using the phrase “leadership development,” but he shared his valuable experience unsparingly, without patronizing, not only with existing leaders but with members and potential members alike, because his abiding default premise, despite the occasional mismatch or disappointment, was that greater leadership, or greater involvement, could indeed be developed. And as is true for any skilled mentor, he knew well when to remain silent or to step aside.

At some point I passed the test. I can’t say when, but I knew it had happened because we continued working with each no matter where Paul’s peripatetic path took him – AFTRA, UWUA Local 132, CFA, SEIU, the LADWP Load Dispatchers, and so on – sometimes at his invitation and sometimes at mine.

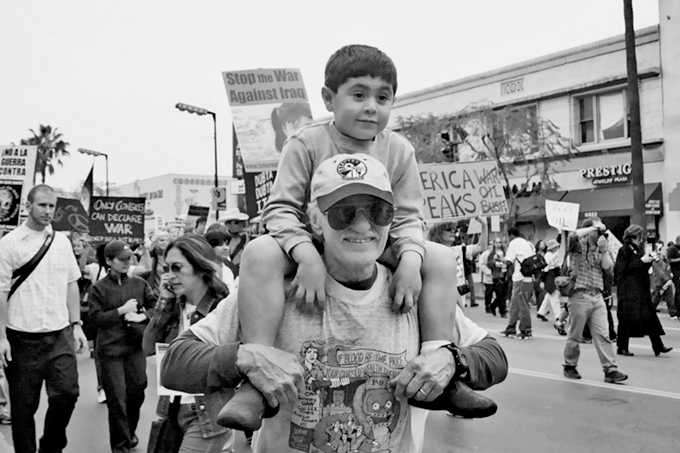

Along the way, our friendship took on the characteristics of family – vacations together in the Pyrenees and British Columbia, coming together for holidays, lifecycle events, and for support in times of need. At the top of this page, sitting on Paul’s shoulders during an Iraq War protest march down Hollywood Boulevard in 2003, is our son Jacobo, who was born on May Day in 1997. When Jacobo was born, I called Paul from the hospital. It was a test. I asked him, “What is the most auspicious day for the child of a union lawyer to be born?” He failed the test, initially. But by the time he called me back he had figured it out. Like the rest of us, he wasn’t perfect, but he was pretty damn good!

…

Paul, You were a great friend, comrade, and pal

By Steve Brier

“What always came through in Paul’s teaching was his abundant intellect and sheer passion for working-class history”

I met Paul in 1970-71 when I was a doctoral student in U.S. history at UCLA and Paul had just started teaching in the department as an instructor. I was soon assigned as his teaching assistant in an undergraduate U.S. history course (it might have been on southern or post-Civil War history; I can’t recall). Paul had his own distinctive teaching style then: He was a provocative lecturer, always challenging his students; he tended to favor flannel or work shirts and blue overalls as his professorial “costume.” But what always came through in Paul’s teaching was his abundant intellect and sheer passion for working-class history. Paul taught me how to be a better labor historian and how to think about the conflicted relationship between issues of race and class in U.S. history. I also learned a lot from watching Paul teach, reading his work, and listening to him engage with and encourage students (including me). He even let me lecture in his class (an “honor” for a grad student) about my own research work, which paralleled his work on interracial unionism in the coal industry (he wrote about Alabama; I did West Virginia). When I set out to do my first coal miner research work back East in 1972, Paul made a point of introducing me to the distinguished labor historian David Montgomery, his dear friend, and encouraged me to make a pilgrimage to visit with Montgomery in his Pittsburgh home and to tell him about my work. I like to think I carried over many of those lessons that Paul taught me in my own subsequent writing and teaching in what has turned out to be my four-decade long academic career.

My daughter Jennie was born in January 1971 soon after I met Paul. Since Paul and Linda had already had Catha (who is a few years older than Jennie), and were about to have Krissy, we all gravitated to the struggle to create and sustain the UCLA Child Care Center (CCC), which was an unrealized and much needed institution at UCLA in those years. One of the hallmarks of that student- and faculty-led struggle that the Briers and the “Worthpeople” (as we called them then so as to clearly indicate our opposition to patriarchy!) helped to lead was that the CCC needed to be open to all members of the campus community: students, faculty, and staff; that it be formed as a co-op in which all parents had to put in a minimum of 5 hours of work a week, not only to reduce costs for students and staff but also to encourage buy-in by the parents; and that the center accept babies as young a few months old, an important concession to young students who were starting families and going to school. The UCLA administration refused to accede to our non-negotiable demands for the CCC, including for a dedicated campus space for the center and provision of necessary support funding to pay unionized staff. When the UCLA chancellor, Chuck Young, refused to negotiate with us we decided to stage a sit-in in his office. After we took over the office we discovered that Young collected very expensive what were then called “Oriental” rugs, which covered the floors of his substantial office space. We quickly decided to reach out to student parents involved in the child care struggle who had young babies and recruited a handful of babies who were known to “projectile vomit” their formula. We brought them to Young’s office where they “did their thing”; the rugs looked polka-dotted after half a day of babies lolling on the floor! Young caved in soon after and authorized the child care center, which is still going more than half a century later. Paul, Pam Brier (my wife then) and I remained actively involved in steering the CCC through difficult times over the next three years as members of the parents’ steering committee. Paul and I even resigned in principled protest over some outrage (the exact nature of which I can’t quite seem to recall at this point). We submitted our joint letter of resignation to Pam Brier, who was then serving as the chair of the board. One thing that you learned when you did politics with Paul was there was no compromise or room for sentimentality, even when it involved a member of your own family!

That both the Brier and Worthman families had girl children was another basis for our bonding. I always admired the way Paul and Linda had raised Catha, who always acted smart, self-assured, and independent, and how they carried that approach over after Krissy was born a few years later, despite Krissy’s medical issues. Paul and Linda were my models as parents of how to raise smart, tough, and independent girls. My daughter, Jennie, is indeed that kind of adult, a fact that I attribute to the model that I observed Paul and Linda living.

Paul and Linda’s house in Mar Vista was a magnet for progressive UCLA faculty and graduate students, who gravitated to their home for meals, music and political and ideological conversations. Paul also recruited his graduate students to help with home improvement projects. He once put me in charge (or perhaps I foolishly volunteered) to build a low brick wall in their backyard that may have had something to do with creating a dedicated space for Linda’s keen gardening skills. I plunged in to the project (not knowing what the hell I was doing) and though I managed to build a “wall” with brick and mortar I can say that my one true regret is that I didn’t build a better, straighter wall in the Worthmans’ backyard, lo those many decades ago!

I was also involved with Paul in what proved to be the tumultuous politics of the UCLA History department, which were endless and frustrating. One moment is illustrative of how Paul approached dealing with his fellow UCLA faculty members and why he ultimately ended up leaving academia for a far more important career as a union organizer and negotiator. The department always had pretensions of becoming the Harvard or Yale of the West. In one key moment in the early 1970s the department big-wigs decided to try to recruit the old school historian and Lincoln scholar David Donald from Harvard to join the UCLA faculty. Because Paul had a well-deserved reputation as a contrarian among his faculty colleagues, they dispatched Frank Gattell, a friend and senior faculty mentor of Paul’s, to make sure that Paul would “behave” in the faculty gathering to welcome Donald to the department. Gattell was especially concerned that Paul shed his work shirt and overalls and be sure to wear a tie to the meeting. Paul assured him that he would indeed wear a tie to meet Donald. And when the time came for Paul to enter the faculty lounge late for the meeting with David Donald, he was not wearing one tie; he was wearing two ties! This was Paul’s way of assuring his faculty colleagues that he knew how to behave like a proper faculty member. Needless to say, Paul didn’t last too many years after that before he made the absolutely right decision to switch careers to his first love: labor organizing.

Paul: You were a great friend, comrade, and pal and I was glad I was able to tell you before you died how much I admired you and what you stood up for in your entire life and career. You will be missed and remembered by me and legions of other family, friends, fans, and comrades.

Your comrade in peace and power,

Steve Brier

…

In memory of Paul B. Worthman – November 11, 1940 – November 3, 2024

By Peter Olney

On Sunday, November 3 Paul passed away at his home in Berkeley surrounded by his family. Always a thoughtful planner he timed things just right. His beloved Dodgers won the World Series against the hated Yankees on Wednesday, October 30 and Paul checked out on Sunday, November 3, 2 days prior to the election of Donald J. Trump.

Paul was a dear friend and comrade to many of us throughout the country and particularly in the labor movement in California.

We at The Stansbury Forum want to remember “Pete” Worthman. We have reached out to family, friends and colleagues for their memories. We decided to dedicate several episodes of the Forum to our friend. We start with my tribute to Paul at his 60th birthday party in Los Angeles in November of 2000.

The Measure of the Man: Worthperson at Sixty

On occasions like this it is customary to look for essence, or that one defining characteristic that captures the honoree. When I think about Paul “Pete” Worthman I think about the quotation: To afllict the Comfortable and Comfort the afflicted.

Paul has won our everlasting respect as a tireless advocate for working people. He has been the principal spokesperson for thousands of workers seeking justice at the bargaining table and in the streets.

When Worthman goes to the table you get a first class organizer, lawyer, researcher and accountant all rolled into one. Artistes in Hollywood, utility workers at the gas company, healthcare workers at Kaiser, 8000 janitors in commercial office buildings, California state university faculty, airline pilots and all kinds of public employees have all benefited from Worthman’s smarts, skills and toughness.

Bargaining committee members and union members wherever Paul has worked remember him for his ability to dispel the boss’s logic, and their fuzzy numbers. In short he has been a first class afflicter of the powerful and the comfortable.

But what I love about Paul is his dogged irreverence and his capacity to afflict all of us too:

- How about those outrageous neckties? Is he wearing one tonite?

- How about the wordplays that transform venerable LA educational institutions from USC and UCLA to USK and UKLA?

- His own surname was transformed to Worthperson as a playful gender equality statement. A Dodger utility infielder named Mike Sharperson followed Paul’s lead.

- I can never forget Paul’s actions at my wedding in 1985 after my wife’s cousin Eddy went out and bought some extra beer for the guests. Cousin Eddy liked Coors. No sooner had the beer been delivered to the kitchen at the Grace Simmons lodge in Elsysian Park than I heard Worthman cursing “phony liberals” and pouring all the cans down the sink!

- His etiquette and breeding at dinner are also an experience. I remember a Southwest nouvelle meal once replete with all the presentation perfection and lack of chow that those cuisines thrive on. A little dash of ketchup substitutes for a hearty helping of vegetables. After Paul feasted on medallions of beef that looked more like dimes, it was time for dessert. The waiter asked Paul what he wanted for sweets and Paul promptly and boldly replied: “the biggest thing you have on the menu”.

- You have heard Fred Sollowey’ s tale of Paul’s politique encounter with a Soviet political commissar and Rene Talbot’s story of Paul eloquent upbraiding of the City of Santa Monica.

- You all no doubt have your own story of Worthman afflicting you with some irreverent remark or aggressive action. I value those memories and we love him for them.

One of the great puzzle’s of Paul has been solved for me in the process of organizing this tribute. When I first met Worthman in 1983, and started going over to his place in Mar Vista, I was perplexed by the fact that Linda, Catha and Kristin all called him Pete. I never asked why, I just assumed it was some intimate family thing that was none of my business. Turns out, as many of you know, Pete is a nomer that Paul chose in junior high because he liked a Brooklyn Dodger named Harold Patrick Reiser, nicknamed and known to the Dodger faithful as Pistol Pete, or just Pete. He was a St. Louis native born in 1919 who in his first year with the Dodgers, one year after Paul was born in 1941, batted .343 and won the batting title. He was 5’11” and weighed 185. He played third base and the outfield and was known for his fearless playing style. Sound familiar? Many say he could have been one of the all-time greats, but he was injured running into outfield fences, and walls.

He along with Pee Wee Reese refused to sign the petition circulated by Dodger outfielder Dixie Walker that asked Dodger players to declare their unwillingness to play on the same team with the first Black ballplayer in the majors, Jackie Robinson. Paul adopted the name Pete in junior high and carried it all through high school forcing friends, and family alike to call him Pete and not Paul. It wasn’t until noted historian C. Vann Woodward at Yale called him Paul that he permitted folks thereafter to use the name most of us know him by.

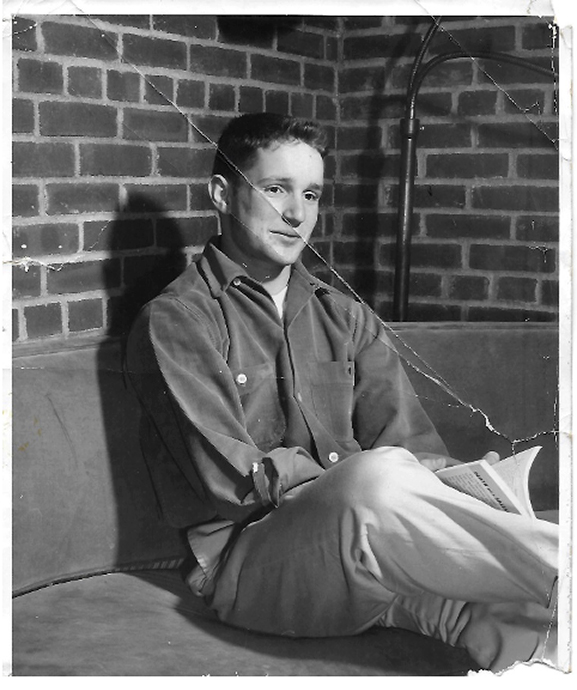

Paul was not an armchair fan of the Brooklyn Bums. Many of you may not know that Paul was a fine athlete in many sports. He was a basketball guard, a track sprinter and a third baseman. He was invited in the summer of 1959 to play ball in the Cape Cod League in Massachusetts. Baseball fanatics know that this has become the premier summer baseball league for college players, and many pros have caught the eye of their first pro scouts in this league because it is the only amateur league that uses wooden bats. Paul worked as a shipyard worker in that summer and played third base for the Chatham A’s.

So, I want to call Paul “Pete” Worthman, a very worth person, to come up and cap off this evening by saying a few words himself.

Happy Sixtieth Paul!

…