BRAZILIANS AGAINST FUTEBOL

By Pedro de Sa

Why has Brazil turned against its religion?

“Pelé is a poet when his mouth is shut”

– Romário

A day before the 2014 World Cup Finals kick-off and São Paulo, the city hosting the first game, is recovering from the longest subway strike in its history. The five-day strike, which was declared “abusive” by the courts, cost the union a bit more than U$200,000.00 a day. The strikers were beaten and gassed in the streets, thirteen were arrested and forty-nine fired.

They are not the only ones taking industrial action. While traditionally militant unions like the teachers were expected to strike, the year was peppered with strikes, from security guards to trash collection to police officers. In Rio de Janeiro, defying both the State and their union, trash collectors stage a massive eight day wildcat strike starting the last day of Carnaval, one of the busiest trash days of the year, winning a 37% wage increase. Even university students had their strikes.

Although the mass protests last year gathered a lot of attention, they faded quickly when the government at first acquiesced to the immediate demand (lower the bus fares), a victory easily lost as a month later all bus fares had gone up again. Much like Occupy in the U.S., the protests were tacitly supported by a great majority of the population, but the actual participants were mainly from the middle-class – in their majority university students.

Brazil winning the Confederations Cup amidst the most violent protests helped calm down the general sense of anger and to cool the protest movement momentarily.

The slogan of the protests also gave a momentary boost to the right-wing in the country. Decrying corruption became a rallying cry of the right against the left-of-center Workers Party government. While their direct influence inside the protests was fairly short-lived, they were successful to bring their particular brand of populism to the mainstream of Brazilian society, with a mix of anti-taxation, anti-government waste and anti-crime (including calls for vigilante justice that led to a woman being lynched to death after being mistaken identified as a child kidnapper.)

Brazil’s endemic corruption, the cost-overrun in stadiums that were either doomed to be abandoned after the cup or, if profitable, immediately privatized (including Maracanã, Brazil’s most famous stadium), while hospitals, roads and other public services continued in their appalling state of disrepair. Popular anger even turned against soccer greatest, Pelé, after he said that Brazilians should wait until after the Cup to protest and that the death of a worker during the construction of Arena Corinthians was “normal.” Ronaldo, another one of Brazil greatest, also felt the popular ire when he said that “You can’t host a World Cup in hospitals” in response to people’s complain that all the spending in the Cup should be used to ameliorate the deplorable conditions of Brazil’s health care system.

One former player, however, emerged as the voice of the disaffected. Romário (The greatest striker I ever seen play), elected in 2010 to the Chamber of Deputies on the Partido Socialista Brasileiro (Brazilian Socialist Party) ticket, has become a vocal critic of the cup’s organization and management. He has gotten in a war of words with Pelé, Ronaldo, FIFA’s Secretary General Jérôme Valcke and FIFA’s President Sepp Blatter (whom Romário called a “thieving, corrupt son of a bitch” on national television). He has tirelessly attacked what he called “the worst World Cup of all times.”

Romário’s criticisms had echo both in FIFA and in those opposing it. FIFA has harshly criticized the organization and the delays of the cup (a worker was quoted in a Monday article saying that only God could get Arena Corinthians finalized before kick-off). At the same time, the criticisms against FIFA stem from the organization’s demands (no taxation in any level, the overturn or adjustment of laws that prohibited the sale of alcohol in stadiums and of for-profit organizations as defined by Brazilian law using volunteer work), and restrictions (many of the traditional items used by fans in Brazilian stadiums will be prohibited, including drums, flares and the really big flags we are very fond of).

The World Cup will happen, and it will be memorable, whether Brazil wins or loses. It has opened the wound of discontent and politicized a whole generation.

Politica di Piazza OO#6

By Peter Olney

Public squares or piazzas play a central role in Italian life. When I arrived in Florence in 1972 I visited some of the small Tuscan towns on the periphery of Firenze and I was a witness to “fare la passegiata”. Literally translated this means “to make a walk”, but in practice is a public ritual in which the townspeople strut their stuff in the public square. Particularly the young engage in ritualized courtship where unattached young men and women parade around arm and arm observing members of the opposite sex. This was not something I had seen on the commons of the cities and towns of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

What happens in piazza is a reflection of the balance of power in Italian society. Poltica di Piazza has its highs and lows. Benito Mussolini was accustomed to addressing huge crowds from a window in Piazza Venezia in Rome during his glory years. Later Il Duce was strung up by his heels in Piazza Loreto in Milano by the partisans at the end of the war of liberation from fascism.

I was mesmerized by a march of 100,000 Italian workers in Rome in 1972 on May Day marching against the war in Vietnam. Workers in their Sunday best, suits and ties, wearing red carnations and carrying flags with the hammer and sickle emblazoned on a red banner filed through Piazza Navona as part of a coordinated nationwide day of protest. I saw in these marchers a physical affirmation of the possibility of radical socialist thinking among working class people. Maybe if history and traditions dictate workers could be won to visions of radical change.

Three personal experiences in “piazza” left strong impressions on a young and ingénue American.

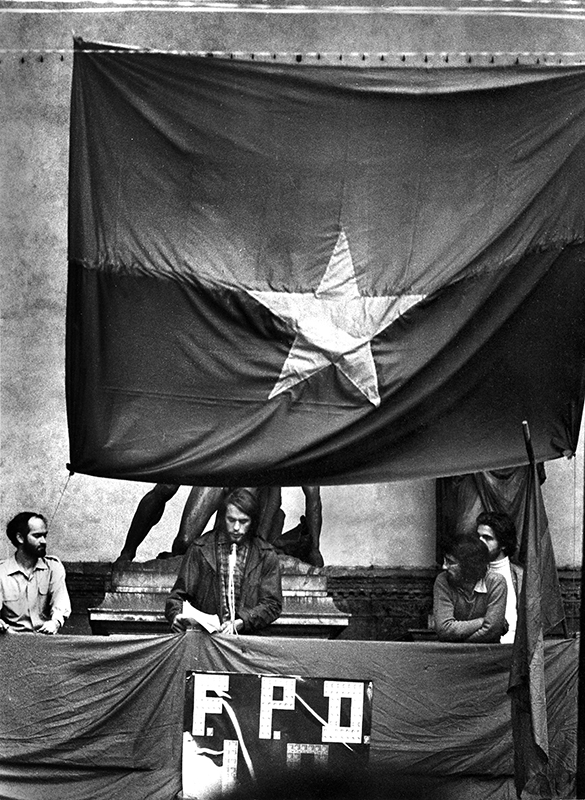

Comizio in Piazza della Signoria – In the spring of 1972 things had intensified in Vietnam both militarily and on the diplomatic front as the talks in Paris to end the war were underway albeit haltingly. In Florence the sizable American ex pat community decided that it wanted to demonstrate publically against its own government’s criminal war. We connected with an array of extra-parliamentary political forces ranging from Grupo Gramsci to Potere Operaio and enlisted their aid to stage a rally in the main square, Piazza della Signoria where the famous replica of the David statue stands in front of Loggia dei Lanzi and the Gli Uffizi. The planning meetings were a spectacle and for us Americans kind of like being a spectator at a tennis match where we would sit and watch the Italians of all different political stripes debate back and forth the merits of including this group or that in the rally.

“I got to spend a weekend in Torino and met all of the ten Trotskyists in Italy”

Each planning meeting would open with a salute to the “Compagni Americani” and then degenerate into a heated debate over their domestic differences. It was agreed that an American should make one of the speeches in English and I was designated to speak. I found a poster on the walls of the Universita di Firenze and copied down the demands from the poster and incorporated them into my written speech. My time came and I spoke in English from the stage and looked at a Piazza full of Italians sitting in the square with the American contingent huddled in the back of the square as giant water tanks were massed with helmeted caranbinieri to deal with crowd control. I delivered my speech and arrived at my dramatic climax proclaiming the demands I had pulled off the agitational poster: No more guns, no more bombs, troops out now! There was dead silence from the crowd, which I of course attributed to language difficulties so I awaited the translator’s work and figured my punch line would yield explosive cheering and applause. Instead there was again dead silence even after my words were delivered in Italian. I was befuddled but as I was climbing down from the stage two Italian men approached me. They rushed to me and exclaimed, “Compagno de la Quarta Internazionale”! They hugged me and invited me to visit the headquarters in Torino later that month. Evidently I had purloined my punch line from a Trotskyist poster in the university and they had identified me as an American Trotskyist. I got to spend a weekend in Torino and met all of the ten Trotskyists in Italy. I also learned that the level of Italian political sophistication was way beyond anything I had heretofore experienced. Finally I learned that in public speaking it helps to know your audience.

Festa dell’ Unita – Unita was the paper of the Italian Communist Party (PCI). It was a daily newspaper replete with sports, culture and coverage of world events and local happenings. Each year in the late spring the Communist Party would hold Feste del’Unita to flex their public muscle in piazza and raise funds. That spring I was invited (my political missteps in La Signoria notwithstanding) along with another American to address a Festa event in Pontasieve, a working class suburb of Firenze. Pontasieve like many of the Tuscan towns was as stronghold of the PCI and like many of the comparable hill towns had a street named Via della Resistenza in honor of the partisan fighters against Mussolini. My American companion was asked to sing and broke out “Where have All the Flowers Gone?” I said a few words about the fight for peace. Then an Italian worker and PCI member addressed the crowd and thanked us for our interventions. He then went on to describe in detail the troop movements of the National Liberation Front (NLF) in Vietnam and the military victories they were winning over the over the Americans and the ARVN. Again I was astounded at the level of training and political sophistication and the radically different world view of these Italian workers.

Chain Gang a Roma – In June of 1972 I traveled to Rome to visit some friends who lived near the University. It was a warm Roman day and I was wearing what is referred to as a guinea tee shirt. On one side of the shirt I was wearing a large Lenin pin and I was carrying a copy of the daily paper of Lotta Continua. I was walking in the section of the University where the Law Faculty was located which I l quickly discovered later was a home base for fascist student groups. Evidently the day I found myself at the law school, a communist in Salerno in Southern Italy had attacked and killed a fascist in a street protest. This was a national event and so the fascist gangs were out for revenge. As I walked the sidewalk I was approached by a group of ten Italian men carry chains. They spotted me and began to shout derisively, “Ciao Compagno.! I hurriedly crossed street into traffic to cut off a part of the gang, but when I got to the other side of the Viale there were still five of them coming at me. One of them must have been designated for this assignment as he started to twirl a heavy motorcycle chain over his head as he moved on me. My adrenaline was rushing so I marched right at the man held up my arm and managed to block the chain and wrest it away from him. I was left there standing holding the chain as the carabinieri approached us. The fascists started to shout that the Communist had assaulted them and that I should be arrested. I will never forget watching a young Italian father with his wife and baby in a carriage rush at the police and start yelling at them to pursue the fascists and arrest them because he had been a witness to everything that had happened. The police backed off as a crowd started to gather, and the family man harangued them. I was allowed to go on my way.

My experience in the public square, my politica di piazza left me admiring the courage and potential sophistication of the working class. I was ready to go home and see whether we could add some Italian sugo to the American political mix.

Next: Living with the Lumpen and making NECCO Wafers

Obama’s CTE Concussion Summit and the Future of Football

By Peter Olney

Yesterday’s concussion summit at the White House shows how far the discourse has shifted from 20 years ago when a “bell ringer”, a concussion causing dizziness and disorientation was deemed just a part of the male rite of passage for young players and a job hazard for professionals.

Yesterday’s NYT carries an interesting quote from Steve Tisch, the chairman of the NY football Giants who says, “What I’d like to see in 20 years from now, no NFL players, no rookies playing in 2014, experiencing any head injuries” He added, “We’re taking some of the first steps in that direction.”

The problem that the NFL and all of organized football faces at all levels is that there are no steps except the complete elimination of the helmet that will lead to a drastic reduction on head injuries and Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE). Yes, ironically the protective equipment is the problem. It allows players to put their head in situations where brain matter is traumatized like an egg yolk floating in egg white. It is not so much the dramatic hits that ESPN shows on its highlight reels but the constant concussive activity on every play suffered particularly by interior lineman whose hands, heads and legs are constantly banging hard object on hard object on every play from scrimmage.

A celebratory head butt by a quarterback with one of his own teammates after a dramatic touchdown pass is traumatic! A hand slap to the helmet by a coach to a helmeted player returning to the sideline after an excellent play on the field is concussive activity. In 2000 I predicted that in 10 years football would become a marginal blood sport. Many looked askance at that prediction for America’s most popular and lucrative sport, but as the data accumulates and the parents get preoccupied my prediction increasingly seems less farfetched. Recently the town of Marshall in football mad East Texas outlawed contact football for students through the seventh grade.

Here for a reprise is the Stansbury Forum piece I wrote in the fall of 2012 entitled “For safety sake let’s play rugby”

OO #5 Italy – Rugby with Frontisterion G.S. Firenze

By Peter Olney

In September of 1971 I showed up at the pre-designated assembly point at New York’s Kennedy Airport. All the students from the Rutgers Junior year abroad program were there with their Italian instructor who would be our program’s director in Florence. Most of them already knew each other from the campus in New Brunswick New Jersey. They were Italian American working class students from ethnic neighborhoods of New Jersey like Dumont, Patterson, Vineland and Jersey City. I was probably the only student without a vowel at the end of my name. I wasn’t in Italy yet, but I certainly wasn’t on the Harvard campus any more.

We all flew to Roma and then rode a train to Florence where we quartered in a Pensione or boarding house in downtown Firenze. Before we were to enter the University of Florence we had been assigned an Italian boot camp to sharpen our skills so we could handle the lectures and classes in Italian. That meant spending intensive time with my fellow students from New Jersey. One of them, Alfonso Gilliberto, knowing that I had played American football announced to me that he was huge fan of “La Juve” and that he would be watching every game they played on TV while in Italy. “La Juve” is short for Juventus, the soccer team owned by the Agnelli family, the founders of FIAT, the giant Italian automaker in Torino.

Sports was then and remains today a big connector for me with other people, especially other men. Some of my comrades in the labor movement have said that Marx’s famous assertion about religion, that “it is the opium of the people”, could also apply to sports. Every time I find myself in a giant stadium filled with over 50,000 people watching a sporting event I close my eyes and wish I were at a rally for workers rights or raising the minimum wage. It would be a great day to see our labor actions consistently draw the giant crowds that even a dismal franchise like the Oakland Raiders is able to pack into the Coliseum for home games. I can certainly see the dulling effect of spending one’s time rooting for the home team rather than dealing with society’s problems. I can also be critical of the rampant racism and sexism of pro sports and supportive of the courageous athletes who stand up against it. But I have chosen to make sports a way to connect with workers. I have chosen to use it as an idiom for teamwork, unity and preparation. In every organizing job that I have had, I have sought out the social networks created by soccer and softball leagues as a way to reach and proselytize among workers.

One day in the fall of 1971 I was out jogging near the Stadio Communale where the Florence futbol team, AC Firenze plays its home games. I jogged around a field where Italians were practicing a sport I recognized as rugby. I heard a voice shouting at me, “Americano, vuole giocare?” I guess they spotted me as someone who could bring some size to their team so I jumped into their practice and started to learn the basics of rugby. This proved to be a very fortunate encounter because I now had the best formula for language comprehension, total immersion among Italians in a sports venue where there is no option but to master the street idiom and even the Florentine accent.

Frontisterion G.S. was the name of the team. Frontisterion is Greek for “ a school for young males” and as its name suggests was originally a training team for fascist picchiatori, goons who were kept in good shape in between “political” assignments. The other team in Florence was CUS Firenze and their ranks were made up historically of very large marshals and enforcers from the PCI, the Partito Communista Italiano. One of the biggest players on their team was nicknamed “Bambino.”

The coach of Frontisterion was an officer in the national Italian police force, the carabinieri, and he was assigned to the political squad. However over the years the team had evolved away from its fascist origins and now all the players were members of the Italian Communist Party, their sympathizers and some students who were sympathetic to the extra parliamentary left, Lotta Contina and Potere Operaio.

I was sympathetic to the extra parliamentary forces and would often go to their rallies and demonstrations. Inevitably in the back of the plaza I would spot our coach, Sr. Bilota. He would beckon to me and I would go find out from him when the next rugby practice of la squadra was taking place. I am sure some of the Italian compagni concluded that the American “comrade” was really a police agent after seeing him consorting with a Calabrian carabiniere assigned to the red squad

“it has become necessary to partially partake in different forms of capitalist mass culture…”

But the team fully embraced me and because of my training in American football, they decided to employ me as a hit man assigned to brutally tackle an opposing team’s best players. I am not sure if I ever fully understood the rules of rugby, but Coach Bilota would give me an opposing player’s number before every game and suggest that I take care of business. I remember playing a game in Ferrara in Emilia Romagna and after a particularly vicious hit hearing the crowd chanting “Yankee go Home’ and “Fuori il codino”, or “Throw out the player with the pony tail”.

But I got my comeuppance. My rugby career ended prematurely in the early spring of 1972 when we played a game against a team of big brawny dockworkers from the Port of Livorno. I made the mistake of using my head in a collision with a large opponent and wound up lying unconscious under a cold shower in the locker room. I could not remember where I was and my Italian deserted me. That following Monday I went to see a medico in Firenze and he examined me and concluded that I could no longer play rugby because I might endanger my brain if I was involved in another violent collision. That was actually my third concussion as I had suffered two in American football. That Italian doctor is probably responsible for the relatively full retention of my faculties to this day. I imagine that medico with his sharp diagnosis and strict orders could have saved a whole generation of American professional footballers from the plague of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) that they are now facing. Viva Italia!

With my brain still intact and not yet suffering from CTE I prefer to take the 1998 perspective of the Austrian Marxist Eric Wegner on the role of sports in capitalist society: “it has become necessary to partially partake in different forms of capitalist mass culture in order not to become completely isolated and to avoid psychological breakdown. Futbol has historically not only served the distraction from political and social problems, but also the creation of collective pride and class consciousness [….] with a more than average progressive potential.”

Next Installment #6 – Politics in the Piazza

Two poems

By Lluvia Carrasco

Mentally disturbed

Mentally disturbed, Mujer Soy.

Words already set me up to fail.

Oh, how language and words forevermore, will never keep up.

Una mezcla de mundos, no? Una mezlca de tiempos,

de sangres,

de historias,

construiendo mi lengua de vivir.

Ahh.. And still, I am not nearly articulate enough; And my mind races…

Infiltrating the language

my soul already carries

With the whispers that my ancestors speak, As they swim within my young blood,

My young, naive, 19 year old

American – Mexican

Chicana – Activist

Educated – Latina

And still, young, naive, 19 year old blood…

Swimming,

Exploring -

The whispers trail upstream Where my mind soars,

As if this human shell

can dare to clip my wings?

And there, My disturbance begins The internal battle of what is true and what is advertised as truth, That there, that is my madness.

My wicked Madness, My womanly Madness, My beautiful Madness.

Nevertheless, it is MY madness.

And they say I am Too Mexican for the Americans, Too American for the Mexicans.

Too bohemian for the hommies,

Too gangster for the hippies.

Too free-spirited;

such as the Hummingbird Goddess of our Aztec Mothers.

Yet Too raw, Too real, Too roughened by life

Such as the piercing wisdom, the warrior spirit of our Native American Fathers.

Treating knowledge as if I am enmeshed Or madly obsessed,

Never missing the kernels of truth, Refusing to lead a misspent youth.

The appetite of curiosity inside, Hunger, that I refuse to let die.

With sight of the light waiting to ignite. And the hands of the mind,

Never tied.

Too politically aware for the youth,

Too grounded for the drugs,

Yet way too high on life & culture to conform, Or maybe too humanly frightened,

To let the fuck go.

Into this White Wonderland, Paradox of a Wonderland.

Such as a passing butterfly would be

As she migrates through the summer breeze, With the rays of the sun,

Shining through the fibers of her wing’s. Beaming through the whiskers of her antennas.

Just as she would be, when the summer warmth Hits

It’s first Winter Flake.

Gazing over the flawless, powdered blanket of a wonderland. And oh, what a wonder it is..

What a wonder it truly is..

Pero asi camino en mi tierra,

Cada paso lo lleno,

De las melodias de mi oscuridad. Del espiritu de mis lagrimas, Con colores de fe,

Con colores de ser humano.

Asi camino en mi tierra…

The unorthodox path that she migrates through Is Simply her bittersweet burden.

Again, this is my Madness.

My wicked Madness.

But Blessed Madness,

And oh so beautiful of a Madness.

hmmm…mentally disturbed; Is simply to be Educated. As A minority of The minority. Womanly Disturbed; Is simply to be Revolutionary Again, as A minority of The Minority.

To struggle with your political depression, academic racism,

cultural dichotomy.

and STILL – find presence in the present.

For this wonderland of a land, is seasonal. And carved with each colorful footprint, With each lining of your toe,

As it marks your skin’s signature –

Leading & Leaving.

Like the artist that you are. Painting & Printing.

I continue to draw on this wonderland, of a Wonderful Land.

And in my hand, My Brush. My Paper, My World.

And for my paint, My Love.

Disturbed with a beautifully tortured, humanistic soul; I will continue to paint,

I will continue to migrate,

I will continue to fuel the ember in me.

Mentally Disturbed, Mujer Soy.

And that is the butterfly soaring in me.

Whatever happened to Humanity?

Whatever happened to Humanity?

When Man’s gentle touch,

Would spark the crawling-tingling sensation of a kiss.

As it would be,

Should be,

The permission already given

By my lip’s caressing embrace.

And Man,

Woman,

Could be entrusted

with one simple stare.

For you knew the language in which my kisses would breathe,

And even if you did not know,

such womanly ways,

or womanly language,

I, HUMAN,

spoke the same.

Ahh, but it was your dominance,

that wouldn’t listen.

Whatever happened to humanity?

When it was in fact,

The melody of my voice,

That sang words you respected.

And No meant No,

But Yes,

meant ahh yes, yes, yes.

Because it was the word,

that you respected,

that would transmit a heart’s desire.

And my mouth,

Became more than a physical vessel

Of instant pleasure…

Taming the selfish needs of your primitive human nature.

Deprived,

Untamed,

& Wild

You feast to surpass satisfaction.

Nooo,

My mouth instead,

Spoke the art of my soul’s language.

And voice,

was heard.

Because it was my existence,

you listened for.

Since the waves of my curving body,

created a siloutte of ever-lasting mystery.

In which you awed for,

Hunted for,

Praised for,

Humbled for,

Explored for,

Patiently waited for my blessing.

Whatever happened to humanity?

When as a human race,

We shared the same land,

the same air,

the same hand,

the same world.

You & I,

shared the same bed.

When as a human race,

To lay with one,

was only to confirm a common truth.

Oh you see,

For when she opens herself

It is as if Spring

Turns to blossom its first flower,

And with your rain,

To bring the first shower.

For really,

Just as any force in the Universe

-This shared world did not birth

From only its waters.

But rather,

The love that was made

When the raindrop reached the land’s seed,

And quenched such a parched thirst.

And Equilibrium is reached.

Ahh,

but again,

It was your dominance that did not listen.

The Human,

Disillusioned.

By one’s own self-perpetuating lies.

The Human,

Therefore governed,

By one’s very own despise.

The Human thus cultivated,

By one’s very own silent cries.

What happened to Humanity?

When in being humanistically human,

Our tolerance becomes perfectly imperfect,

When living by our vile virtue,

We become legally illegal.

Whatever happened to humanity?

When Man’s gentle touch,

would spark the crawling-tingling sensation of a kiss…

As it would be,

Should be.

Dealing with the Donald – Direct Action to Remove Sterling as LA Clippers Owner

By Peter Olney

The media is all-abuzz with the Sterling Scandal. The 80 year old attorney and real estate baron from Los Angeles, Donald Sterling appears to have been captured on tape telling a girl friend that he doesn’t want her hanging out with black people or bringing them to his basketball team’s games. He is the owner of the Los Angeles Clippers who for first time in their history may make the second round of the NBA playoffs. He has even explicitly said that he doesn’t want the revered Earvin “Magic: Johnson at his arena with her. Nor does he want her posting images with Blacks.

What to do?

The league as Charles Barkley has said is a “Black League”. 80% of the players are African American. Kobe Bryant says he wouldn’t play for an owner with those racist views. Talk is swirling about the Clipper players boycotting their games with the Warriors in the first round of the playoffs. But unfortunately it looks like “cooler” heads are prevailing. The crisis reveals the innate conservatism of the leaders of most of the sports unions who have been seduced by the myth of attorneys as the best choice for union leader. Too often the sports unions and more broadly many of the entertainment unions choose “smart” attorneys to represent them because the producers or the owners have smart attorneys. What they need instead are organizers and union leaders not attorneys. They need to break out of the innate conservatism of legal training and be willing to take the risks necessary to win. The great Marvin Miller who led the Major baseball players out of servitude in the early 70’s was formerly a leader with the United Steelworkers union.

In the case of the Sterling scandal we have the NBA Players Association seeking counsel and guidance from the Mayor of Sacramento and former NBA and Cal guard Kevin Johnson. KJ is a corporate Democrat. But there is another course of action to be taken rather than playing for the good of the league as Doc Rivers and his LA Clippers have decided to do at this juncture.

Here we go with a daisy chain boycott strategy

The Clippers refuse to play in the next game, Game 5 of the playoffs against the Warriors. What does the league do? Default the game to the Warriors? Default the series to the Warriors? Then the Warriors refuse to play in the next series and you get the idea. The other owners would quickly see to it that the daffy and racist Donald is removed by the league as an owner. This is peak season for their TV revenues and earnings. Instead we will see a “thorough” investigation and maybe fines for Sterling, but he will be allowed to continue as an owner.

This is an industry where the players are the game, and this is a moment where the crisis and public opinion would support such a daisy chain direct action approach to removing Sterling. James Earl Jones said it in the great political baseball movie. “Bingo Long and his Traveling All Stars and Motor Kings, “ WEB Dubois says we have to seize the means of production.” This is one of those situations where strategic workers through their actions can force dramatic change.

Time for action, not civility and docility!

#4 Summer of 1971 – Lewd Moose Commune

By Peter Olney

In early May, 1971 200,000 veterans, youth and students converged on Washington DC to “Stop the Government and Stop the War” as the call to action said. Peaceful protests of millions had not changed the minds of the rulers about the Vietnam War so many felt more aggressive actions were needed. On Monday morning, May 3 we organized ourselves into affinity groups and sat down at key intersections in Washington to block morning traffic and keep the government from functioning. While at the ground level all we seemed to be doing was pissing off angry commuters it appears in retrospect that the protest had impact. National Airport was closed as an emergency precaution due to the level of traffic disruption. President Nixon called the Army’s 82nd Airborne in with helicopters and 12,000 of us were arrested-the largest mass arrest in US history.

Several of my comrades from Harvard who had been jailed together in DC decided that we should all live together that summer. We recruited other friends: a total of eight in all to rent an old ramshackle house at the end of a cul-de-sac called Fiske Place in the Central Square neighborhood of Cambridge. We had a vague sense that we would function as a community and at least for the summer share resources and chores like cooking and groceries. The “Commune” was named Lewd Moose from the Seuss story, “Thidwick the Big Hearted Moose”. One of my sister communards thought I was big like Thidwick, generally good hearted, but “lewd” in that I failed to wash my dishes and clean up after meals.

Most of us had gainful employment. My two Harvard friends Buck B and Tom F were working on the assembly line at the General Motors plant in Framingham. My roommate Nucci and I worked at the New England Produce Center in Chelsea. We rode our bicycles every night about 5 miles to work the graveyard shift unloading giant trailers loaded with fruits and vegetables. We were members of the Teamsters union, but never saw a union representative. All we saw was a weekly deduction from our paycheck for union dues. We would unload trucks in from North Carolina loaded with cucumbers, watermelons or frozen crates of corn on the cob. It was hard, hot and sweaty work, but a piece of cake for two ex footballers. Watermelons were the best cargo, because every load would have a “damaged” melon that we would be obligated to take home to the commune. In fact we kept the Fiske Place household stocked with produce all summer!

Nucci and I would arrive back at Fiske Place in time to see some of our cohabitants leaving for their day jobs. Weekends were the only time when we would all hang out together. We took trips to Maine, to the beach and to the North End for the feast of Saint Anthony, but most of the memories I have of that summer are working with Nucci in the back of an icy trailer digging out crates of frozen corn.

The FBI seems to have thought the name Lewd Moose Commune implied a deep level of political commitment. They took us seriously enough to reference Lewd Moose in some of our files, but it was more a gathering of folks who shared some vague cultural and political and personal attachments. Some of us however have remained life long friends, and we even convened a couple of Lewd Moose reunions.

The most vivid memory I have of the summer occurred late one morning after I returned from lumping freight. My lifelong friend Jeff was living with us that summer with his girlfriend M.J.. Jeff’s brother was a big shot in the Progressive Labor Party (PLP), which dominated Harvard SDS while I was there. PLP was distinguished by its rigidity and workerism. Cadres always had short hair, got married and lived the idealized and imaginary life of the workers they so desperately were trying to rouse to revolution.

Jeff’s’ connection meant that the Party was interested in recruiting our Commune. That morning in July of 1971 we received a visit from two earnest looking PLPers asking for Jeff. Buck B answered the door and without hesitation led the two cadres upstairs to Jeff and M.J.’s bedroom. He opened the door to find them in bed together. The PLPers recoiled at the door, but Buck jumped into bed and gathered his communards in his arms and exclaimed, “Don’t worry we are one big happy family here.” Needless to say that was the last recruitment visit we received from the PLP that summer!

#3 Football, La Fiorentina and Archibald Cox

By Peter Olney

Many of the radicals who helped to form and shape my old union, the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU), were merchant seamen before they worked “along shore”. They had traveled to exotic places around the world and been confronted with different realities and turbulence and revolution. The union owes much of its glorious past to these pioneers whose worldview was expanded by world travel.

Consciousness is often elevated by a radical change in one’s environment.

My life was radically changed by my experience of a year abroad in Florence – Firenze, Italia. Many Americans end up in the Tuscan cradle of the Renaissance because of a professed urge to study art history. I got to Florence because of language and then love.

I had studied Latin since the 7th grade. During my five years of classical study, I had read the Odyssey and the Iliad in Latin and performed in Latin theater. Deciding I wanted to be able to watch Italian movies without subtitles I took a course in Italian as a senior elective in the fall of 1968.

That was the first year Italian was offered at Andover. Taught by Mr. Markey, a French instructor who had never studied Italian, he stayed one lesson ahead of the students. The class was three of my Italian American teammates from football and a 6 foot 2 Brit who later became a Labor Member of Parliament. On the last night of class the Professor invited us all to ride into the North End, the traditional Italian neighborhood of Boston for an Italian meal. He dined us and maybe wined us at a white tablecloth Italian restaurant on Parmenter Street off Hanover, the main street of the district. Quite a sight; the diminutive Mr. Markey escorted by 4 hulking footballers and a big Brit.

That summer, 1969, I returned volunteering at the North End Neighborhood Center where I was hired to tutor young Italian kids in English. Soon the kids discovered that I was trying to learn Italian and spent the rest of the summer tormenting me with their rapid fire Neapolitan dialect. One day in June we chaperoned the children to Scusset beach just north of Cape Cod on the South Shore of Massachusetts. On the beach I met another tutor in the program, Marinella, an Italian from Firenze. We talked all the way home on the bus. She tolerated and teased me about my Italian. She had a warm smile and a seductive laugh. I was smitten, and I insisted on walking her home to the family she was living with on Beacon Hill. With that began my almost two year courtship of La Biava, la Fiorentina.

Marinella had witnessed the devastating flood in Florence in 1966 and the whole situation had so depressed her that her mother and her older brother decided it would be best if she got out of Italy and went to the USA as a nanny. She started out in Evanston, Illinois caring for young children of a family there, and then moved to Boston to live with a wealthy old Brahmin family on Beacon Hill. We were a couple by the time I began my freshman year that fall at Harvard University. It was my relationship with her that would lead me to live in Italy in 1971-72.

“Many of my teammates were ethnic Italian and Irish working class kids from the greater Boston area…”

But first a little of my experience at Harvard. I was assigned to live in Strauss Hall right on the edge of the Harvard Yard in Harvard Square. I took Italian and a lot of courses in Political science, which I thought, might become my major and kind of befitted the turbulent times. I remember taking a course with Carl Friedrich, a Professor and German national who had written the post war constitution of West Germany. I would sit in the front row of a giant hall to listen to his lectures; inevitably falling asleep only to awake in an embarrassed start, feeling like the whole lecture hall was looking at me. The fatigue was not just the product of his boring lectures, which consisted of him reading chapters from his book. I was tired because I was playing football and worn out from practice and the endless meetings and film study sessions.

Football was an intense experience even at a non-powerhouse like Harvard. It was also the place along with the hockey team where Harvard sought to infuse the ruling class with some new blood, some toughness from the other side of the tracks. Many of my teammates were ethnic Italian and Irish working class kids from the greater Boston area who were there to play football or hockey. Many of them had brothers and friends who were in Vietnam. Some of them were not real enthused by my anti-war attitudes and politics. Long bus rides to games were often punctuated with intense and emotional discussion over the war and the protest against it sweeping across college campuses. I managed to hold my own in those discussions because I had held my own on the gridiron. I remember being charged by multiple teammates in the “bull in the ring” drill during practice. I fended off the charges of my line mates and emerged standing bleeding profusely because the bridge of my nose had been broken. One of my teammates slapped me on the helmet and said, “Not bad Prep”. The “bull in the ring” drill has since been banned from all levels of football.

The war even bled onto the field. I’ll never forget the head football coach telling us in my sophomore year that if anti-war protestors invaded the field during a game, we were to dutifully retreat to our dressing room under the stadium.

I participated in most of the public protest on campus against the war and Harvard’s complicity in it. Shrill rhetoric about the leading roll of workers in revolutionary struggle was never much substantiated by actual blue-collar participation except for the occasional presence of a few Harvard custodians. There was no lack of debate about the issues however, and there were plenty of “bull in the ring” intellectual encounters in which my clever and intelligent classmates would spar over the issues of the day and spread their oral genius. I was never much for these discussions because they reminded me of prep school sparring that was predicated on wit and clever remarks, not grounding in real experience.

The most dramatic moment in my time at Harvard occurred in the spring of 1970. The US began to bomb the dykes in North Vietnam and protests escalated throughout the country culminating on May 4, 1970 when the National Guard gunned down four students at Kent State. Eleven days later at a Mississippi black college, Jackson State, two protesting students were killed without much of the national anguish over the four at Kent State.

But prior to Kent and Jackson a major protest was called for the Boston Common on April 15th. I went to the protest on the MTA Red Line from Cambridge to Park Street station. I stayed for the whole rally. Abbie Hoffman, the leader of the Yippies (Youth International Party) gave a stirring speech in which he pointed at the John Hancock building, then the second tallest building in Boston and shouted, “See that hypodermic needle, John Hancock was a revolutionary not a fucking insurance salesman.”

After the rally I climbed up over Beacon Hill on my way to Marinella’s. Four or five hours later I decided to ride the MTA to my dorm in Harvard Square. As we approached the square the train stopped unexpectedly several times. Finally the train pulled into the station and the few of us still on, got off. I rode up the clackety old wooden escalator and emerged into a darkened eerie square with fires burning everywhere. The Cambridge Trust and the Harvard Bank’s windows were both smashed in and trashcans burned throughout the square. I looked north along Massachusetts Avenue and saw Cambridge riot police massing to charge down into the square to clear the area. A group of Weathermen had marched back from the Common along Massachusetts Avenue and smashed store windows, trashed banks and gutted two police cars with fire.

“…“impaled” on the Yard fence.”

Well the Weathermen were no longer in the square but I was, and I was all alone. My roommates and friends were inside the Yard and the giant metal gates had been shut and chained. They yelled for me to climb over the fence. The fence was over ten feet tall and the wrought iron bars were capped with metal spikes. I started to scale the fence and got one leg over the spike when my back foot slipped. I was wearing dress shoes with slippery soles. The knee of my right leg became caught on the tip of the fence. Fortunately my friends were able to raise me up and over the fence to safety just before the Cambridge cops swarmed into the area. They would have most certainly pulled me backwards and done severe damage to my knee.

My adrenaline was rushing so I felt very little pain in my leg, but then I examined the tear in my pants and discovered a gaping wound. My knee had been impaled on the Harvard Yard fence!

Friends escorted me thru police lines to the student infirmary where med students took turns looking at my wound, which was deep enough to offer them an opportunity to study human anatomy up close. Finally they stitched me up and sent me back to the Yard.

Among all the news radio reports of the Harvard Square riots one story emerged of the Harvard freshman that had been “impaled” on the Yard fence. Harvard’s attorney at the time was a law school professor named Archibald Cox, who had been Solicitor General for four years under Presidents Kennedy and Johnson. He would later be one of the casualties of the “Saturday Night Massacre” of October 20, 1973 when he was dismissed by President Nixon from his post as Special Prosecutor during the Watergate scandal.

At a press conference later that evening Cox was asked by the media about the impaled freshman. All imagined a human body run through front to back by the sharpened spikes of the yard fence. Cox calmly faced his questioners and demonstrated his acute legal mind and attention to detail by saying,” Let’s find out where he was impaled.”

Needless to say I remember very little of academics from my two years in Cambridge. I was absorbed by my relationship with Marinella, who was my first serious girlfriend and love. I would visit Italy with her in the summer after my freshman year. She stayed in Italy at the end of the summer, and I returned to the USA alone. Our relationship continued in unsatisfactory fashion via snail mail letters and strained phone calls at odd hours because of the time difference. I decided that if we were going to make it I would need to move to Firenze. I applied and was accepted into a junior year abroad program with the State University of New Jersey, Rutgers. The program was attractive because rather than isolating American students in a Villa with each other, the Rutgers program inserted its students directly into the Universita di Firenze.

Soon after my acceptance however my relationship with Marinella fell apart, but I decided to push on to Firenze anyway. In the fall of 1971 I set out for Italy

In the next installment I describe my year in Italy; on strike at the University, giving an anti-war speech in the Piazza della Signoria, playing rugby and being attacked by a fascist gang in Rome.

Olney Odyssey #2 – Grandmother Anne S. Bowman and My Life’s Path

By Peter Olney

Correction: After the Forum posted Olney Odyssey #1, Jeff Crosby, the retired President of IUE local 201 in Lynn Massachusetts, wrote in to say that Al Coulthard Sr. played a key leadership role in the early days of Local 201, but he noted that as far as he has discovered in his research, Coulthardt was a socialist not a communist. Thanks to Brother Crosby for the correction and thanks to him for his years of service to the working class.

“External causes are the condition of change and internal causes are the basis of change” On Contradiction, Mao Tse Tung 1937

Some baby boomers were propelled down the road to working class radicalism by the clash between the values that the “greatest generation” nurtured in us and the external social realities of racism and war. Each of our journeys is unique and yet each is the same.

My father, Peter B. Olney Jr., was one of those young men who in 1943, fresh out of high school, enlisted. He was a medic and while he saw much, he said little but for one story. He told me of an incident when the driver of a flatbed truck popped the clutch lurching the truck forward and throwing the soldier standing on the fantail to the ground. That soldier was Black and the white driver roared with laughter. My Dad rushed the cab, grabbed the driver by the neck and punched him in the face. “Don’t you ever f…ing do that again,” he said. I will never forget that story and what it taught me.

Through sports my father taught us a lot about values. As manager he enraged Little League parents when he insisted on playing all the team members even if it meant losing a close one. He made sure the football was equally distributed to all ages in the family touch football games. My youngest cousin, Sarah, would always be dramatically escorted into the end zone by a phalanx of the biggest males that warded off any members of the opposing team. My Dad would vex and perplex other fathers who were obsessed with winning even in family touch football.

At home honesty and integrity were taught by example and never compromised. My mother, Elinor Bowman Olney is the same as my Dad, although she could be tougher. I remember her actually threatening to wash out my mouth with soap for uttering some cuss words. She is a no-nonsense New Englander who revels in telling me on the phone every time it snows and ices over in Massachusetts that, “We will survive, we are a hearty people and used to it”. She also has a great sense of irony and humor. I think it was three Christmases in a row in the early Seventies that she received a Mao Tse Tung calendar from me and each year with a twinkle in her eye she exclaimed that, “How did you know I needed this calendar. What a wonderful surprise.”

“She had marched with Martin Luther King in Selma and with King and Walter Reuther in Washington, DC in August of 1963”

Values in the home led us to challenge hypocrisy in the world and to seek big answers. These were the bases of change fostered at a very young age, but ironically it was my Grandmother’s choice of Sunday school that sent me on my path to the working class.

Until 1963 when I went off to a summer camp for two weeks in Ferry Beach, Maine, my connection with my grandmother, Anne Stewart Bowman was very traditional. Sundays and holidays were a time to visit the Bowman house at 87 Cedar Street in Malden, Massachusetts. Grandmother always put out a fine traditional meal topped off with a homemade baked pie. The house was big. It was great to roam around in with a wooden standup bowling alley in the back room that my sister Anne, my brother Steve and I entertained ourselves on…. and fought over. The Malden house had a tell tale aroma to it that followed Grandmother and Grandfather all over the world so that when I visited them in 1972 on Via Sistina in Rome I could close my eyes and imagine with my nose that I was back in their Malden house and a child again. Grandfather enjoyed listening to his vast classical and opera LP collection and took particular relish in playing my sister, brother and I the first Beatles album before we even knew who the British mop heads were.

But during those two weeks in ’63 at Ferry Beach at the mouth of the Saco River I experienced something that was to happen to me many times in the more than thirty years after. I was introduced to a woman named Alice Harrison who was a friend of my grandmother’s and the Director of Youth Programs for the Unitarian Universalist Association on Beacon Street in Boston. Alice puzzled over my last name and she asked if I was Elinor’s son. I said yes. She then exclaimed, “Why you are Anne Bowman’s grandson.”

Those summers in the mid sixties at Ferry Beach were discovery days filled with the fervor of the civil rights movement as Unitarian Universalist (U-U) ministers returned from the the South to tell us of their adventures and spur us on to activism. One of those ministers, James Reeb (here and here), was murdered by a white racist mob in 1965 in Alabama. I discovered that my grandmother knew Reeb and all of these activists. She had marched with Martin Luther King in Selma and with King and Walter Reuther in Washington, DC in August of 1963. In later years I loved listening to her recount her stories of marching and protesting for civil rights and justice. But her mentoring always included the stern admonishment to “Be sure and get your degree.”

In 1995 just before my grandmother passed away I attended a service at the U-U church in San Francisco. I was browsing in their study after church and I came across a book entitled, The Larger Faith, a Short History of American Universalism by Charles Howe. I rushed quickly to the chapter on the 1961 merger between the Universalists and the Unitarians and there found a reference to my grandmother: “Anne Bowman, who had been elected secretary of the new association, had done such an excellent job that in 1965 she won the denomination’s highest honor, its Award for Distinguished Service to the Cause of Unitarian Universalism.”

“My grandmother’s simple and practical decision to enroll her children in a Universalist Sunday school, her skills as a nutritionist and her basic sense of fair play created the environment within which I found my life’s path.”

How did the daughter of a Scots Irish immigrant to Pittsburgh Pennsylvania become a top leader of America’s most liberal and socially active church denomination? Anne Stewart grew up in a strict Presbyterian household in Beaver Falls. Her father, David Stewart, was the superintendent of the Jones and Laughlin Steel mill. If suitors came calling for Anne or her sisters, the first question from her father to the young man would be, “What parish were you raised in?” Needless to say the local Catholic parish was the wrong answer and entrance was denied.

My grandmother studied nutrition at Carnegie Institute of Technology and graduated and then met my grandfather J. Russell Bowman at a summer session at Edinboro State College, where he was a teacher and she the campus nutritionist. They moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts where he received his doctorate in English at Harvard and then relocated to the working class suburb of Malden during the depression. Grandfather became an English teacher at Malden High School, and grandmother a homemaker raising her children, the oldest of whom was my mother born in 1927. In 1934 it was time to find a Sunday school for the children and there was no room at the Presbyterian Church so grandmother made a practical decision to enroll my mother and my uncles in the nearby Universalist Church. She became active in the women’s federation as she cooked the meals for the Sunday Socials and rose to a national leadership position before the merger of the U-U in 1961 when she became the national secretary of the association’s board of directors.

My grandfather Bowman, the descendant of Pennsylvania Deutsch immigrants, grew up in Lebanon PA. He was a brilliant man who did not suffer fools and ideologues. He had a particular distrust of the Catholic Church, partly because a priest in Malden had launched an attack on his “Good Reading and Discussion Group”. This was a great books discussion group that he led from 1948 to 1965 when he retired. During the height of the McCarthy period in the early fifties this priest questioned whether the readings were sufficiently patriotic and loyal. In 1965 my grandmother was honored at the Statler Hilton Hotel in Boston at the Unitarian Universalist Association Annual Banquet. She received “the annual award” on the occasion of her retirement for her service to the church. The theme of the evening was the newly emerging “ecumenical” movement and many other leaders of other faiths were honored also. But his eminence, Richard Cardinal Cushing, the Archbishop of Boston paid eloquent tribute to my grandmother. My grandfather Russell had to sit thru the Catholic tribute to his wife and stew over his stew.

My grandmother’s simple and practical decision to enroll her children in a Universalist Sunday school, her skills as a nutritionist and her basic sense of fair play created the environment within which I found my life’s path. As I wrote when she passed in 1995, “Anne Stewart Bowman was a mover and shaker and a delicious pie maker!” Thank you grandma.

In Olney Odyssey #3 I will recount my two years at Harvard playing, football, protesting the war and studying Italian.

Kettle Bell Karma – These Are Not Your Daddy’s Building Trades

By Peter Olney

Recently on a Sunday morning I sat on the infield of the track at Piedmont High School. I was exhausted from a brutal kettle bell workout devised by our coach and master trainer Roy San Filippo. I had done 1 440-meter lap, 10 reps of plank push-ups and 40 reps of 35-pound kettle bell swings repeated three times in a span of a little over 17 minutes. I was the senior guy at age 63. The energy all flowed from the youth, one of who, my son Nelson, shamefully lapped me during the training routine.

I listened in on a fascinating exchange between Nelson and a journeywoman union electrician named Emily, a Taiwanese-American in the East Bay International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW) Local 595. She was advising Nelson, a newly minted first year apprentice in the San Mateo local, on handling lay offs and lack of work. She told him, “When I get asked to sit at home I prefer to take the layoff and then I go back to the hall and sign up for work with a new company. I don’t wait around and hope that my present employer will call me back. My attitude is that I work for the Union not the Company, and I have learned the hard way that this is the best way to get work”.

The Business Manager of Emily’s local is Victor Uno, a Japanese American who as a young apprentice was initially barred entrance from a union meeting by the Sargent at Arms, who tore up his dues receipt, refusing him entry. When he finally was able to get into the meeting, a member commented “hey Fred, are we allowing Chinese in now?” Indeed we have come a long way from the Chinese Exclusion Act passed in 1882 and championed by the old American Federation of Labor and its leader Samuel Gompers. This was a measure that the barons of labor of the SF Building Trades Council supported and that Dennis Kearney, the mayor of SF on the Workingmen’s Party ticket fought for.

“We would be false to them and to ourselves and to the cause of unionism if we now accepted privileges for ourselves which are not accorded to them…” J.M Lizarras, 1903

Victor Uno gave me a great bit of history that dramatizes the conflict between class solidarity and race bigotry: “When the Japanese Mexican Labor Association tried to affiliate with the AFL in 1903, Gompers directed the union to bar Japanese and Chinese from membership. J.M Lizarras, the association’s Mexican President refused, stating: “We would be false to them and to ourselves and to the cause of unionism if we now accepted privileges for ourselves which are not accorded to them…We will refuse any kind of charter, except one which will wipe out race prejudices and recognize our fellow workers as being as good as ourselves.” Gompers never responded when Lizarras returned the AFL charter.”

My son’s IBEW apprentice class of 30 in San Mateo is majority people of color with 7 women. The SF Ironworkers have taken in over 100 Chinese workers as journeymen in order to deal with the growing non-union ironworker sector. What would Dennis Kearney say about that? The trades when I came into labor in 1972 were lily white and in my home City of Boston a new union of African American workers, United Community Construction Workers, was created to combat the exclusivity and racism of the construction unions. They would march on to all white job sites in Boston and shut down the project seeking a commitment to hire black construction workers.

Perhaps the most common image of the building trades emblazoned in the consciousness of young radicals like myself in the early seventies was of the mobilization of hard hats on May 8, 1970 to beat up peace protesters in lower Manhattan. The march was led by Peter J. Brennan of the New York City Building Trades Council, later to be appointed by Nixon to be US Labor Secretary. Almost 42 years later in March 2002 on the day that the bombs started falling on Baghdad as Bush initiated the war on Iraq, the California Labor Federation and State Building Trades opened their annual legislative conference at a hotel in Sacramento. The assembled leaders were abuzz with talk of the war. The speeches from the podium however were about workmen’s compensation reform and other dross labor matters. Then Bob Balgenorth, an IBEW member and the leader of the State Building Trades approached the dais. He launched into a stirring and memorable speech entitled, “Badges? We don’t need no stinking badges” in which he, denounced the impending criminal loss of life and treasure in Iraq. Here is a lengthy quote from Balgenorth’s speech:

“In a memorable scene from the classic western, Treasure of the Sierra Madre, Humphrey Bogart demands to know if the men about to rob him are bandits or lawmen as they claim. Their response is the famous, “We don’t need no stinking badges!”

Might makes right.

Bush will have his war, Congress will have to give him the $90-100 billion he demands for the cost of war. The billions to rebuild Iraq will add to that sum. And, underlying all of this is the current $400 billion deficit projected for this year alone. We support our troops anywhere in the world in which they are in harm’s way. We pray for their safety particularly in Iraq and the hornet’s nest that will develop around that doomed region. In the turmoil that follows we can only hope the loss of life will be minimal. But wars have a strange habit of getting out of hand”

Balgenorth was so prescient. Some things indeed have changed. These are not your daddy’s building trades!!

The kettle bells wiped me out, but the conversation between Nelson and Emily rejuvenated me. I’ll be back for more.