OO #9 Odyssey Interrupted – Boston Busing 40th Anniversary

By Peter Olney

I had intended to continue to roll out the story of organizing Mass Machine Inc. into the United Electrical Workers in June of 1973, but the 40th anniversary of court ordered school busing in Boston forcefully interrupted me. The Boston Globe in particular has been running a lot of multi-media remembrances of the busing crisis. I decided that OO#9 had to deal with the busing crisis as a retrospective. We will return to the Odyssey chronology in #10, but it is important to mark September 12, 1974 with some commentary.

It was that fall day in Boston that the buses rolled carrying black students from Roxbury to South Boston High School where they were met by mobs of white youth and adults throwing bottles, bricks and stones. The rest of 1974 and into 1975 was consumed with white racist mobs assaulting buses and blacks. The rest of the next decade was marked by outrageous acts. In 1977 Theodore Landsmark, a prominent black attorney was assaulted in front of city hall during an anti-busing rally by a white youth who attempted to impale him on a flagpole carrying the stars and stripes (here and here) In 1979 Darryl Williams a 15-year-old high school football player was shot and paralyzed by a sniper’s bullet after scoring a touch down at Charlestown High School. There were numerous attacks on blacks moving into white sections of Dorchester, and into the white neighborhoods of East Boston and Hyde Park. All these incidents put a spotlight on the racist segregated character of Boston where blacks knew that it was not a good idea to be caught in South Boston, the traditional Irish-American neighborhood after dark or in broad daylight. The Cradle of Liberty was not such a cradle for people of color.

Court ordered busing was not conceived as a broadside against latent Boston racism, although it certainly revealed all of that. It was the result of a lawsuit by the NAACP that alleged separate but unequal schools for black and white children. The concept was to eliminate disparities by breaking the segregation of neighborhood schools that reflected the segregated neighborhoods of the City. Federal Judge Arthur Garrity was an Irish American who made the ruling and issued the court order. In a lengthy finding in June of 1974 Garrity documented the “separate but unequal” character of the schools. No question that the white Boston School Board had funneled resources to the white schools at the expense of schools where the enrollment was minority majority. The documentation in his ruling shows the depth of the segregation. In most cases schools were 90% white or black. Since the 50’s black community leaders like Mel King and Chuck Turner had fought the School Committee to cough up the resources to improve the schools of color and to make logical changes to existing school boundaries that would have naturally integrated schools. Finally the NAACP filed a lawsuit in March of 1972 entitled Morgan vs. Hennigan. Morgan was the lead African-American parent plaintiff and James Hennigan was then the head of the Boston School Committee.

The case was made that there were inequities in the existing quasi apartheid system; blacks schools suffered from the comparative lack of resources. Busing would force a redistribution of resources and equalize the schools. So ordered by the courts. Most of the left and liberal organizations took a position of supporting busing as a way to end segregation.

The opposition to busing was led by the infamous Restore Our Alienated Rights or ROAR. ROAR became the political vehicle for a whole slew of opportunist white Boston politicians. Louise Day Hicks of the Boston School Committee who later was to run for Mayor using the slogan: “Every little breeze seems to whisper Louise”. John Kerrigan, the Chairman of the School Committee. Elvira “Pixie” Paladino from East Boston, a largely white Italian neighborhood and Jimmy Kelly, a building trades guy from Southie who later became a City Councilor. The official appeal to the white community was one of fighting for neighborhood schools, for the right to stay at the home school. Judge W. Arthur Garrity was seen as a pointed headed liberal imposing his rule from his comfortable suburb of Wellesley, Massachusetts. In a famous public moment School Committee Chairman Kerrigan rolled out a chart showing the racial composition of schools in Boston and Wellesley. The comparison was telling; 35% of Boston school enrollment was people of color, 1.8% of Wellesley’s schoolchildren were minorities. In fact there was a busing plan that addressed these inequities called Metco that transported students between wealthy suburbs and urban high schools. But it was a voluntary program and very limited.

“Paper positions on politics are made more powerful by the actual ability to move change in the real world”

The organization that I was part of took a different tack from the rest of the left. We argued that busing was an attack on the whole working class. We looked at the massive inequalities between the suburban schools where Garrity and his family lived and the urban schools for all students white, black and latin. We posited that the busing plan was an attack on workers driving them to fight each other over crumbs rather than fighting for real improvements in the City’s schools. Because of our anti-busing stance we were ridiculed by the rest of the left for siding with the racists. Certainly it was hard to stomach the racist attacks and our position was hard to defend in the emotional moments of that year.

We didn’t shirk from propagating our position at ROAR rallies and wherever people were marching in opposition to busing. The leaders and members of ROAR certainly differentiated our position. One of our members was beaten severely with a baseball bat for distributing a flyer questioning busing but opposing the racist attacks. Several of our members had to be relocated from South Boston under threat of being burned out of their houses. We tried to walk a very difficult and maybe impossible line of opposing busing as an attack on the working class, but also opposing the racist nature of the anti-busing movement. Looking back I think that the physical attacks on us were not so much driven by a quibble with our anti-racist position, but more because we were hated as Reds.

Paper positions on politics are made more powerful by the actual ability to move change in the real world. Our position had little impact except in left wing debates in the new Communist movement. But if there had been a union local or a community organization that united people of color with whites that could have opposed the racism but argued for a radical redistribution of educational resources not just busing kids around then there might have been the basis to advance a position similar to ours. That would have required organization that certainly we and the rest of the left did not have.

One exemplary organization that did grow out of the busing crisis was the Boston School Bus Drivers Union affiliated with the United Steel Workers of America. Prior to forced busing there was a very limited bus driver work force. Children walked to their segregated neighborhood schools. In 1974 hundreds of bus drivers were put on to deal with escalated need for transport across the city. This workforce was a reflection of Boston demographics with major representation from all the neighborhoods and women and men. In 1977 when their pay was cut by 88 cents per hour, organizing began to form a union. The organization became a living, breathing example of multi-racial unity because as one leader of the drivers said, “We were all being stoned together”! They issued a famous flyer that was distributed to children to pass to their parents calling for an end to racist attacks (Link). The Local became a beacon for a multiracial revival of the Boston labor movement in the 1980’s, including playing an active role in supporting the historic Mel King for Mayor/Rainbow Coalition campaign.

“Our correct analysis of the class inequities between suburbs and the Hub led us to downplay the history of racial inequity…”

Dialing forward forty years what was the result of busing? Did it serve to equalize resources and the quality of education in the Boston public schools? Did the forced busing crisis force Boston to shed its veneer of cultured liberalism and come to grips with the deep-rooted racism in its neighborhoods? Busing exposed the racism of Boston, and the Hub was labeled by many as the most racist city in America. Quite a shameful label for the birthplace of the American Revolution. While Boston’s racial profile has improved in the last 40 years, the schools probably haven’t. And because of white flight to the suburbs and the Catholic schools the system is almost completely children of color, 87%, even though Boston remains a majority white city.

Certainly one thing busing did not do was confront the ocean of inequity between City schools and the wealthier suburbs. Those inequities remain to this day as they do in all urban/suburban areas in the USA promoted by policies whereby schools are largely funded by property taxes.

So do these continuing inequities and deficiencies absolve our position against busing? NO. Our correct analysis of the class inequities between suburbs and the Hub led us to downplay the history of racial inequity in the City’ schools and the roiling racism that led many in the white community to follow the demagogic lead of ROAR and the South Boston Marshals. In fact our desire to find a common platform to unite the working class missed the fact that such unity is only built upon the recognition of the inequities in every facet of life. The recent events in Ferguson, Missouri are hugely illustrative. The shooting of Michael Brown has peeled back the outrageous practices of small communities surrounding St Louis, some like Ferguson that are majority black. The municipal coffers are fueled by random traffic stops of poor blacks that lead to arrest warrants and cascading fines. In short there is a new Jim Crow!

Recently Richard Trumka, the President of the national AFL-CIO traveled to St Louis to address the Missouri State AFL-CIO convention. In a powerful speech (here and video here) he explained to delegates, “We must take responsibility for the past. Racism is part of our inheritance as Americans. Every city, every state and every region of the country has its own deep history with racism. And so does the labor movement.” Trumka got what we scientific socialists missed in Boston, that it is only through fighting racist terror and inequitable treatment that the working class can fight together against its corporate enemies. Contrast Trumka’s sharp denunciation of inequity and white racism to the equivocating musings on the 40th anniversary of busing of newly elected Boston Mayor Martin J. Walsh, “ At some point, we need to have a conversation about what busing did to Boston and not be afraid of the conversation. I know black people that are still angry about busing. I know white people that are still angry about busing…. They are angry on all sides”. (Boston Globe September 13)

Busing was a blunt and ineffective instrument in dealing with the historic racism of the Boston School Committee and the white political establishment. The court order arose however in response to years of community advocacy and struggle. We had no freedom to influence the broader question of the inequities between suburbs and urban schools that we pointed to so of necessity we needed to dedicate our selves to opposing the racist attacks, pointing out the inequities and holding up the example of the Boston School Bus Drivers. 40 years hindsight coupled with the events of Ferguson focuses the mind.

Next OO#10 and back to 1973 and organizing the UE at Mass Machine in the heart of Roxbury.

PBO 9-20-14

OO # 8 Mass Machine and the United Electrical Workers (UE)

By Peter Olney

“The litmus test appears to be whether they are perceived as champions and organizers around the rank and file’s basic needs or not”

Massachusetts Machine Shop, Inc. was a small metal stamping factory on Albany Street opposite Boston City Hospital in the heart of Roxbury, Massachusetts. The company manufactured washers, burrs and shims of all shapes and sizes. The Knight family of Marblehead had owned the company for generations. Total employment was 60 workers toiling in an old four-story brick factory building whose parking lot abutted the giant Stride Rite shoe corporation across the street.

Mass Machine was not a citadel of capitalism at the commanding heights of the economy, but a lot happened in the three years that I worked there from 1973-75. Our organizing there generated a lot of lessons and also a lot of illusions. I say our organizing because the factory was “salted” by four of us, all with different political outlooks. Salting is an old term that refers to the practice of politically conscious organizers going to work in a factory, mill, mine, hospital or other service workplace to organize a union or strengthen the existing union. The metaphor comes from “salting” a mine to bring out the richness of the ores or “salting” a wound to exacerbate the sores. Salting is the richest term, but “industrializing” or “colonizing” are oft used descriptors for this political practice which has a long history on the American left. There is a fine biography of Hapgood Powers entitled “From Harvard to the Ranks of Labor” by Robert Bussell, that recounts the odyssey of a Harvard student who participates in some of the most epic battles of labor in the 20’s and 30’s as a worker and an organizer.

My choice of Mass Machine as a place to “salt” was not the product of any deep reflection on strategy or any thought of paralyzing capitalism by striking at key sectors of the economy. At the time if I had been in one of the many Maoist political formations I would have been directed to seek work at one of the three “Generals” in the greater Boston area. General Electric has a massive manufacturing operation (albeit downsized today) that makes giant gears and jet engines in Lynn. General Motors had an assembly plant in Framingham. The Fore River in Quincy was home to the giant ship builder, General Dynamics. All these facilities were well stocked with left wing agitators. At the time I was working at NECCO in the fall of 1972 I was part of the Red Lantern Collective in Cambridge. The collective took its name from the title of a revolutionary Peking Opera performed on May 1, 1970. We were all radicals out of Harvard grappling with how to be revolutionaries. One thing that was respected and exalted was the process of transforming yourself, betraying your class background by becoming a worker and organizing. So when I met up with some left-wingers working at Mass Machine who were committed to organizing a union there, I jumped on board. They were welcoming of me as my command of Italian was considered a big asset, a third of the workforce was from the region of Catania and the cities of Avellino and Benevento.

In late January of 1973 I began my employment at Mass Machine Shop. I was hired as a punch press man. I fed sheets of metal under a cutting tool that cycled up and down when operated by a foot pedal clutch. My press was manual and I was handling heavy metal stock that was cut into washers. Other presses at Mass Machine were automatic, running thinner stock off of coils. The presses all had individual electric motors, but the old overhead belts that had been driven by a universal shaft were still hanging from the ceiling. The problem with the presses was that the clutches were not precise and the cutting tool would sometimes cycle on its own creating the possibility of danger to the digits. My first week on the job, the punch repeated on me when I had my left thumb in the die area. I escaped with a slight wound, but the scar reminds me of Mass Machine to this day. One of my fellow workers was not so lucky. The small factory was abuzz when Pat Caizzi our foreman commanded Salvatore Masi, the long time maintenance mechanic to clean up the blood and skin from the die area after an employee’s finger was chopped off. Sal was upset and let everyone know that he did not like being forced to confront the gore of the unfortunate accident. In an industrial setting, the maintenance mechanics play a key role because workers rely on them to keep their machines running, and they have the run of the factory so they become message carriers. Sal had been a loyal Knight family guy, but now he was talking union.

There were four of us who were the industrial salts all with differing political perspectives, but when it became clear that there was “heat” among the workers, a desire to organize, we had to figure out what union to work with. We knew that the International Association of Machinists (IAM) and the United Steelworkers (USW) represented metal manufacturing facilities. However we found that there was a Local 262 of the United Electrical Workers with small manufacturing facilities in the Boston area. This was an amalgamated local with many smaller to mid size shops in its membership unlike a giant single corporation/single plant local like the unions at the 3 “Generals”. The winter meeting of District 2 of the United Electrical workers was to be held on a weekend in February at a hotel in Framingham. We asked the union if we could attend and were invited to meet the delegates from all over New England. After the usual formal agenda issues of new business, old business and Good and Welfare were dealt with, International Representative Don Tormey was asked to make his report to the District. Tormey was a legendary organizer and leftist who had traveled all over the country and Canada (hence the designation International Rep) organizing and representing workers. Tormey must have known that we, young impressionable leftists, were in the audience. He launched into a denunciation of capitalism and its evils. He linked it to the challenges that UE members were facing in their workplaces. We were heating up! Then he wrapped up his remarks by blasting the control that capital and the government exercise over workers and concluded by declaring that, “We need a dictatorship of the proletariat.” We decided there was no need to interview any other unions. We drove east back to Boston warming to the task of organizing our fellow workers into the United Electrical Workers, the UE.

I have often wondered thinking back on Tormey’s speech as to whether he was regularly accustomed to reveal his politics so openly to all the members of the UE District Council and the rank and file. After all even in the ranks of the UE like any other trade union in the United States there is a huge spectrum of political opinion. Did Brother Tormey fear that being so open about his socialist politics would make him prone to attacks and possible retribution? He certainly must have experienced the challenges of the Red Scare McCarthy period in this country when Communist labor leaders and unions were public enemy number one. In studying history though it appears that many Reds have been open about their politics and still held in high esteem by more conservative union sistren and brethren. The litmus test appears to be whether they are perceived as champions and organizers around the rank and file’s basic needs or not. I have seen other union leaders who have openly displayed their left politics but forgotten to tend to the needs of their rank and file, savaged by worthless opportunist opponents who fill that vacuum in leadership of the day-to-day struggles.

The most famous example of this dynamic in the UE was the case of Bill Sentner (here and here) who was the leader of the UE District based in St Louis during the red scare of the early fifties. Try as they might the local power structure, politicians and employers could not dislodge the open communist, Sentner. The rank and file supported him and was not surprised about his political affiliations because they had never been a secret. It was only when the UE national leadership perceived his presence as a problem that he stepped down. The same is true for the legendary leader of the March Inland in Hawaii that organized all the plantation sugar and pineapple workers into the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU) in the 40’s and 50”s. Crew cut Okie Jack Hall was an open communist and yet no amount of red baiting including directly from the US Senate that was to approve statehood for Hawaii could dislodge him from the favor of ILWU members. There is something to be said for sinking deep roots with the workers, sharing their lives and fighting with them for better conditions of life and work. It does wonders for one’s credibility on a host of issues including socialist ideas.

Next OO#9 – Winning the UE at Mass Machine and a first labor contract in three languages

THE MOVEMENT Part 2: Peter Olney continues his interview with The Movement veteran and activist Mike Miller

By Mike Miller

“People have too many experiences of powerlessness, and not enough of collective power”

…when you build such power you can get statewide power without having electoral majorities

Peter Olney (P): In most of the states of the Black Belt South African American population hovers around 30%. In many states the presence of new immigrants, Latinos and Asians, mean that “minorities” approach 40% of the population. Why haven’t these demographic groups leveraged their numbers into more statewide power? What would that power look like beyond occupying seats in legislatures and the executive?

Mike Miller (M): There’s a preliminary question to be asked: Has black power been built in Mississippi? I don’t think so. There are lots of black politicians, but for the most part they are mainstream Democrats.* There needs to be a black equivalent of the Tea Party to hold black elected officials accountable to deliver a quality education and economic justice program. Without that, you can change the color of those who hold political office, and that’s a good thing, but you won’t address the daily living issues of everyday black people. Of course the same thing is true for low income Latinos or any other group that is marginalized both on the basis of race/ethnicity and economic justice.

So the first Mississippi step, from my point of view, is building real, as distinct from rhetorical, black power—power rooted in the lives of the vast majority of black people in the state. When you do that, electoral participation is one of its expressions. Equally, if not more, important are direct negotiations with powerful institutions like major employers (private, nonprofit and public), school districts, developers and others. When you don’t get respect at the negotiating table, you use the tactics of disruptive non-violent direct action, strikes, boycotts, corporate campaigns, public shaming and anything else you can come up with. You engage in people power lobbying—thousands of people descending upon the state capitol to push a legislative agenda forward. Another important dimension of power is to create alternative institutions like worker- and consumer-owned cooperatives. Serious black power would support unionization of low-wage workers in the state, if not engage in workplace organizing itself.

In fact, when you build such power you can get statewide power without having electoral majorities. Whether to participate or not in any given electoral contest then becomes a tactical question: can we elect someone qualitatively better than the incumbent? Can we hold him/her accountable after winning an election? What’s the cost/benefit analysis of allocating our time and energy this way compared to, let’s say, a boycott?

From a different slant, Congressman Bennie Thompson, the African-American representative from the Delta’s 2nd Congressional District, had some interesting things to say at the reunion: he bemoaned black politicians who want safe districts (80+% black voters) when by spreading their constituency into adjoining districts there would be the possibility of electing more blacks while retaining their own seats. He noted that a number of elected black politicians aren’t really representing the interests of those who put them in office, and indicated the need for effective organizing to hold them accountable. He is one of not-too-many politicians who understand the necessity for independent organization at the base. On the other hand, the black elected officials who want safe seats often enter into unholy alliances with conservative white Republicans who are only too happy to isolate the black vote.

Sadly, Chokwe Lumumba, the recently-elected mayor of Jackson, died before he could implement what promised to be an economic development and justice program. Bob Moses calls him a “Fannie Lou Hamer Democrat.”

SNCC was an organization of organizers, or so we thought at the time. With the sometimes-diverging guidance of people like Ella Baker, Bayard Rustin, Myles Horton and a few other older veterans of the struggle, we did amazingly well and accomplished extraordinary things. But we really didn’t know how to be an organization of organizers. And our own internal divisions prevented us from figuring that out. One of my hopes at the time was for a relationship between SNCC and Saul Alinsky, who I went to work for after four years on the SNCC staff.

For a very brief period in the mid-1960s, Stokely Carmichael and Alinsky discussed the possibility of a relationship. They shared a platform in Detroit that was originally billed as a debate on black power. Alinsky said, “If you came here expecting disagreement, you’re in for a disappointment. We don’t go into a black community and come out at the end with pastel power.” The relationship did not develop. The field of community organizing still needs to explore ways of pulling together different strands of thinking and practice in order to maximize the people power it promises to deliver.

“An old story comes to mind: a union organizer in a deep-south state was organizing a factory where whites made $2.00 and hour and blacks made $1.00

P: Is such a failure because there is no white bloc of voters or historical white actors who can be allies?

M: There was a brief period in Mississippi during the mid-1960s when SNCC supported a poor whites organizing project. There are examples in U.S. history where parallel organizing of whites and blacks led to unity among them, and greater people power than either might have had alone. I think a pre-condition for such an approach is the kind of black power organization I describe above.

So let’s assume you’ve got that. Two approaches are usually put on the table. One is to woo white “moderates”. While important, on the major poverty-related and economic justice issues I do not think it is sufficient—for two reasons. When these moderates do enter alliances with Democrats, it is typically with “corporate Democrats” and they will not entertain the kinds of proposals that are necessary to address black poverty, poverty in general, and the growing gap between the wealthy few and everyone else. Further, the black Democrats who pursue these alliances are, themselves, unwilling to engage significantly with black poverty. The policy options required to address poverty are now beyond the narrow frame of “realistic” politics in the country. That means major demand “from below” will have to push this agenda to make it realistic.

Another place to look for a break in the now-racist white bloc is at low-to-moderate income whites who view race as a central part of their identity. An old story comes to mind: a union organizer in a deep-south state was organizing a factory where whites made $2.00 and hour and blacks made $1.00. He said to a white worker, “If you have a union, you can both make $3.00 an hour.” “Yeh,” the white worker replied, “but then I’d be making the same as the nigger.”

But there’s another, and opposite, story as well. A 1930s union organizer told me this one. A white worker he was trying to interest in the United Mine Workers said to him, “Ain’t you the union let’s in the niggers?” The organizer pointed to a nearby black worker and this exchange followed:

“See that fellow over there?”

“Yeh.”

“Who’s he work for?”

“Peabody.”

“Who do you work for?”

“Peabody.”

“You think about it. I’ll be back, and we can talk some more.”

In the recognition election, the UMW won. It took white worker votes to win.

You don’t have to go back to the ‘30s to find similar or hopeful stories in this regard. In the late 1960s, former SNCC field secretaries Bob Zellner and Jack Minnis worked in the midst of a strike at the Laurel, MS Masonite plant in which whites struck and blacks scabbed, and had encouraging results. Dottie Zellner wrote the story up. Both Dottie and Bob were at the reunion. As far as I know, no one asked them to discuss this experience.

Fannie Lou Hamer’s earlier described pig coop is another example. That experience is written up in the biographies about her. My understanding is that she was respected and loved by poor whites and blacks.

White Pentecostal coal miners in West Virginia leveraged their status as part-time “jack-leg” preachers to get Pat Robertson, hardly a pro-union clergyman, to endorse a strike. Latino Pentecostals are increasingly engaged in the immigration rights movement as they see the consequences of Obama’s present deportation policies for their member families.

When you start looking there are lots of examples. But you have to look. Historically, Mississippi white Democrats were divided between racist populists and racist plantation owners and their supporters. The former really hated the latter. But they hated blacks as much, if not more. If you start with the premise that this can’t be changed, you won’t change it.

There’s yet another dimension to this. In my SNCC days, it was not uncommon for a field secretary to speak of “crackers,” “honkies,” or “rednecks.” African-Americans who would never utter the negative terms “spik,” or “kike,” and for whom “nigger” (except when used among one another) was a fighting term, thought this negative was o.k. Indeed, it often got a chuckle. Why is that? And can we use the understanding we get from looking at that to look at poor whites? I think so. People want to be “ok.” If to do that they need to be better than someone else, they will. And the someone else is typically lower on the status pole than they are. The reason for that is that those lower are also more powerless. They can’t effectively strike back. It’s risky to say things like that about the more powerful; they can hurt you.

P: What is the potential for an alliance of people of color and poor whites in southern states? How do you build it? What are the issues?

M: The potential for true majority constituency alliances, so long as constituent parts have their own power to protect their own particular interests, is vast. We have to look back to the industrial union movement of the 1930s to get a glimpse of what that might look like.

In a period like the one we’re now in, it’s built patiently, piece-by-piece, no magic just careful organizing. We’re now swimming upstream when we try to build people power. Periods of social movement, on the other hand, are magical; you’re swimming downstream. You can’t keep up with the demand for organization. That existed in the 1960s in the black community. It appeared in the immigration reform movement recently, and maybe is still there. I’m not close enough to know.

As to the issues, beware of magic bullet single-issues. You learn the issues by listening to the people. From an organization building point of view, you need lots of little but meaningful ones because those can be won by guerrilla bands—which is what you start with. When you have a standing army (sorry about the military metaphors, but they’re easy and graphic), you can fight bigger battles. But the big battles can also wear you down and send your people back home to their TVs and private lives. (Use as title above photo)People have too many experiences of powerlessness, and not enough of collective power. It’s the latter that build for the long run.

In Mike Miller’s third piece on The Movement and legacy, he asks: “What makes you think we (California) have Latino empowerment?”

For further reading: The New Racism in The New Republic

40 days and 40 Nights: A Most Unusual Victory at Market Basket

By Rand Wilson and Peter Olney

After a weekend of last minute haggling and prolonged negotiations, a settlement of the Market Basket dispute was announced Wednesday night bringing to a close one of the most dramatic and inspiring labor struggles in the United States in many a year. The settlement was not immediately about wages or benefits or job security language. These employees don’t even have a union! The settlement was about who would be their boss and CEO. In a highly unusual management-led action, they paralyzed the company’s 71 stores and promoted a devastating consumer boycott to get previously fired CEO Arthur T. Demoulas back and they won.

Most of the 25,000 workers from part-time checkers to big shot regional managers will be returning to work immediately. In fact, during most of the dispute, most of the checkers and in-store personnel worked, converting their stores and parking lots into protest platforms where the few remaining customers were engaged in intense discussions about the MB dispute. Where once the walls of a store were adorned with promotional ads, now they were decked-out with signs extolling the virtues of “Arthur T.” and their desire to maintain his business model over his cousin Arthur S. The strike was a strategic one by a combination of key workers in trucking and warehousing and top and middle managers whose industrial actions prevented any perishables from reaching the stores. Market Basket became nothing but a big dry goods chain.

Threats of firing and numerous “drop dead” days for employees to return to work came and went, virtually ignored by the workforce that was out. The power of a united and strategic workforce acting forcefully with broad consumer support rocked the whole of Eastern Massachusetts and its 30 stores in New Hampshire and Maine.

Would the workers have been better off in a union? Yes, of course. There is no substitute for the power and voice that collective bargaining provides for workers. Yet, the great irony here is that if Market Basket workers had been in a union, it’s nearly impossible to imagine them striking to restore their fired boss and defeat the Wall Street business model of his cousin Arthur S. A no strike clause and the narrow post WW II vision of our labor unions would surely have prevented that.

We should also point out that warehouse and trucking is usually with the Teamsters in unionized grocery stores. Often the decision to respect UFCW picket lines is not always forthcoming or impossible because of contract language.

An NLRB charge was filed by several employees arguing that the company’s threats against them constituted a violation of their Section 7 rights to protest and redress their “wages, hours and working conditions.” If a settlement hadn’t been reached, a National Labor Relations Board Administrative law judge would have had to rule on whether the discharge of the CEO constituted a “unilateral change in working conditions!” The employees certainly saw that it did — and put their own lives on the line because they saw their own conditions inextricably bound up with who was their CEO.

Below are some lessons from this extraordinary struggle that we draw for the rest of the labor movement:

● Not all workers pack an equal punch – Strategic workers in trucking and warehousing are crucial to interrupting the flow of goods, particularly perishables. Current labor laws (especially in the private sector) exclude many of the most strategic workers making meaningful strike activity much harder.

● Management rights are workers’ rights – Unfortunately not since the UAW’s Walter Reuther has the U.S. labor movement sought any real say over operating and management decisions. Instead, we’ve surrendered to the narrow “management rights” clause written into virtually every union contract. Yet, these decisions, as the MB workers demonstrated, are crucial to the livelihood of workers.

● A real strike stops production – Campaigns at Wal-Mart and in fast food have called the exit of a handful of workers from stores and fast food outlets “strikes.” But most have failed to stop production. Market Basket workers (management and labor) engaged in a true “strategic strike” and the camera shots of empty shelves and empty stores were a compelling image that needed no virtual enhancement or Facebook ‘likes’ to be real.

● Community support is key – The depth of support in the massive boycott where customers taped their receipts from Stop and Shop, Whole Foods and Hannaford’s to the windows of Market Basket was an essential part of the victory. For many customers this was a deep hardship, but the passion and energy of the workers and Market Basket’s low prices underlay consumer’s commitment to stay away until victory.

Union or “not-yet-union,” one fundamental lesson is that there are no shortcuts to deep organizing at the point of production. Labor strategists and organizers who are impatient with that process and believe that social media and corporate leverage can substitute for the basics are doomed to failure.

Following this monumental struggle, Market Basket and its workers will never be the same. To reach a settlement, Arthur T. enlisted the notorious private equity firm, Blackstone Group to buy one third of the company. As a result, the Market Basket culture and its manager’s paternalistic practices may significantly change. Meanwhile, Market Basket’s workers expectations have never been higher and the sense of their power – even without the managers’ support – can’t be denied. The vast majority of workers are part-time and low paid. The UFCW is actively reaching out to enlist support. Stay tuned because there is undoubtedly much more to come!

When a strike is a strike: The saga of Market Basket in New England

By Peter Olney

What has been big regional news for four weeks is breaking into the national consciousness with extensive coverage in the New York Times, NPR and the Today Show.

It is the story of the fight for Market Basket/Demoulas supermarkets in Maine, New Hampshire and Eastern Massachusetts. The employees are on strike and are waging a colorful and creative community-based struggle to keep their CEO Arthur T. Demoulas. Arthur T. was thrown out by the Market Basket Board of Directors in June. The coup against Arthur T. was led by his cousin Arthur S. Demoulas. The forced exit of Arthur T. is the culmination of a long family struggle for control of the three generational family business founded by Grandfather Demoulas in Lowell, Massachusetts.

Truck drivers, warehouse workers, deli counter attendants, top level managers, checkers etc. are all on strike and have been for four weeks. The 71 stores are empty of all but dry goods, and even though the stores are open they are empty of customers who are loyal to Demoulas (This was the name of the market when I was growing up in Massachusetts!) because of the low prices and the customer service. My mother is one of those customers who are not shopping at Demoulas in solidarity with the strike. Customers are taping their receipts of money spent at other markets on the windows of the empty DeMoulas stores.

This is one of the most sweeping and captivating labor struggles in the private sector in years. There is no union and the employees are striking and protesting, at one rally 25,000 strong, for the return of their CEO Arthur T. False consciousness, confused workers bamboozled by their CEO and mangers, many of whom are also on strike? NOT! Demoulas workers are loyal because they can read the handwriting on the Wall Street wall. The new board is about cutting costs, squeezing assets and raising profitability on the backs of the employees. The employees correctly foresee a Bain Capital takeover ala the Mittster.

Long time Boston-based advocate for worker ownership and decision making, Chris Mackin, commented in a recent TV interview that the workers are specifically “challenging the business model” being proposed by the Market Basket board.

The outcome remains uncertain, but the power of 25,000 workers in motion and united with their customer and community supporters should not be lost on labor organizers. It is refreshing to see a real S-T-R-I-K-E in retail that paralyses production and commerce with the support of the customer community. I showed a video of a news clip of the Market Basket struggle to a training for union bus drivers and the reaction was surprising to me. I expected the reaction to dote on the fact that the workers were without a union and misguided in supporting their boss. Instead the participants in the training took inspiration in the passion, creativity of the workers and their close ties with their customer base. It was a great lead in for a healthy discussion of building a driver-rider alliance.

Strikes require deep roots and ties with the work force and their issues to be effective. In retail, there needs to be a solid alliance with the community customer base to be successful. Organizers taking on industry giants like Wal-Mart or organizing fast food workers at McDonalds would be well advised to study the lessons of Market Basket.

Links to checkout:

“Market Basket stalemate continues as cousins fail to reach agreement on terms of sale”, Masslive, 25 August 2014

Minor league team wades into Market Basket fight

What the Heck Is Happening at Market Basket?

Market Basket workers, customers rally around beloved CEO after firing

The Rubbed Balloon On The Ceiling: A Few Thoughts About Robin Williams

By Michael Yonchenko

August 11, 2014

Robin Williams’ death was reported in the NY Times as an, “apparent suicide”, and that he was suffering from, “deep depression”. When I have spoken to some friends about his death, and from the many comments that I have read in the press, the nature of his death seems to have surprised some people. Those who know anything about his personal history, as well as the nature of bipolar disorder, easily understand how this happened. It was a terribly tragic, but logical end to a life that was inhabited by an illogical psyche. I’m certain that my fellow manic-depressives are nodding as they read this.

When I watched him perform I reacted breathlessly as he would comically pound his way through a manic storm. He had an astounding ability to extemporize comedic commentary, edit it on the fly, self-reflect, and then seamlessly connect to another topic all completed within a gulp of air. I could sense how much fun he was having and how much pain it caused him simultaneously (Did I go to far? Did I hurt someone’s feelings? Did I just harm myself?). But that’s the nature of a manic storm. It is tremendously exhausting and ultimately ends with the pendulum swinging into depression.

His stand-up routines, as manic and improvised as they appeared, were mostly well-rehearsed routines. My wife Lea and I had the rare privilege of seeing him at a comedy club in San Francisco in 1990. It was a private event that had been set up for him and Bob Goldthwaite to try out new material on a live audience. Here was a rare opportunity to watch him corral that intense improvisation, to catch the lightning and bottle it. And he did. He would get rolling, the way a Formula One car rolls, driving it up on the sidewalk, back onto the road, spinning some donuts, idle, write some notes, step on the gas by repeating what he had just said and taking it in a new direction. We were sitting at the front of the stage and were able to see him work close up. His eyes never stopped observing the audience, even in those moments when he would stop to think, to make notes. He took my overcoat from my chair, put it on, and drenched it in sweat as he improvised as Al Capone, then a wino, then a flasher. (He later offered to pay for dry cleaning).

To call his routines improvisations doesn’t give him enough credit. Indeed, they were routines based on improvisations that he would then improvise upon when performing. A routine was a springboard for improvisation in subsequent performances. He harnessed his manic-depression and channeled it unlike any comic I have ever seen. He created remarkable comedy as an antidote to the maelstrom inside. It must have been exhausting.

I once asked my psychiatrist to give me medication for my depression, but not the mania. He laughed because he understood why I was asking. Manic episodes can be intensely creative, fun, exhilarating, sexual, evocative, soaring, in-your-face-funny and outrageous. But too often they are terribly draining, expensive, destructive to others with displays of inappropriate behavior. For me they are also self-destructive. I suspect he had similar experiences. After all, these are the most common aspects of bipolar disorder. Maybe I’m projecting my own feelings here, but I suspect not.

Years ago, I ran into to him on a Sunday afternoon in Golden Gate Park. He was with his kids. I was skating. Actually I was falling forward on eight wheels, helmeted, gloved and padded. I said hello and he asked me how I was doing. I rubbed my belly, patted my head and said, “”Depressed”. He laughed his big, loud, life-loving guffaw. I think he understood what I was saying. Nothing else needed to be said.

Robin Williams let us mortal bipolar people seem, well, mortal. He showed us that we can function in a world that rages around us as we rage within. His mania was reassuring to me. I am sorry and very sad to see him succumb to the demon within. I will miss him.

Editor’s note: Current events have delayed publishing of Mike Miller’s second and third pieces on THE MOVEMENT and what it means today. The next post will be on the labor situation at Market Basket.

Mike Miller on Freedom Summer and Beyond, Part 1

By Mike Miller

Long time organizer Mike Miller recently journeyed to Mississippi for the 50th anniversary gathering of Freedom Summer. Peter Olney interviewed Mike for The Stansbury Forum on his return. Here, running in three parts, are his thoughts on the reunion, his trip and the relevancy of the Freedom Summer experience to today.

Peter Olney (P): Mike, you recently returned from the 50th anniversary gathering of the Freedom Riders in the South. Please tell us where you went on your trip and what were some of the activities you participated in?

Mike Miller (M): On the way to Mississippi, I stopped at the National Civil Rights Museum, a fantastic place. You can stand on the balcony where Martin Luther King was assassinated, and look across the way at the window through which his assassin fired the fatal shot; then you can cross the street and visit the assassin’s spot as well. I didn’t stand on the balcony; too painful. I wondered how history might have been different had King, Malcolm X and Robert Kennedy not fallen to assassin’s bullets. Might a different political configuration have led to something other than the country’s turn to the right?

Making a left turn in one of the halls, I saw a well-known SNCC brochure photo of Martha Prescod, Bob Moses and me (along with some unidentified local people) on the wall and said to a friend, “There I am!” Martha was in Greenwood, MS when I was there in 1963. She became a Movement historian, and is a co-editor of one of the SNCC women’s books. Bob, of course, is the legendary organizer who was SNCC’s Mississippi Project Director.

Hearing my “There I am,” a guy next to me wanted to know the story. One thing led to another. He wanted a picture with me. Then about 20 black kids making a museum visit together did as well–so I did it one-by-one. Their faces and comments showed a feeling of standing next to a piece of history. It was a touching moment.

The rest of the museum is a terrific collection of visual and narrative material about “THE MOVEMENT”—which we always wrote in capital letters. It, along with the one in Birmingham and, hopefully, a soon-to-be opened Mississippi civil rights museum, should not be missed.

The Delta counties had black a population 70% to 80% with five percent registered to vote at the maximum; in some it was closer to zero. Fear was deep. People were fired, evicted, denied credit, refused cotton ginning, beaten, their houses fire-bombed, and at the brutal worst, murdered. Internalized oppression led many to consider politics “white folks business.” By and large, none of that exists now. Blacks now work where they never could before; there are local towns and counties with black elected officials, cops and sheriffs. Ebony, a 31 year-old black woman, picked me up at Tougaloo for my car rental. We chatted. While she insisted on the southern “sir,” there was none of the deference that characterized black-white interactions 50 years ago.

But conditions now are in many ways what they were then, and in some ways worse. The schools are still largely segregated, and awful; poverty for the majority is still a fact of life; un- and under-employment are widespread; drugs have penetrated the area, and form an underground economy. Together, these elements create the school-to-prison pipeline, which is alive and well in the state. Mississippi is the poorest state in the country, and no place is poorer than the Delta.

In Indianola, two black students told us about their schools: old books, a strict dress code, suspension for slight infractions of the rules, inadequate staffing. “It’s like a prison,” one of them said. They are part of a school reform organizing effort, whose organizer Betty Petty was our host. Southern Echo is the organization that carries on the MOVEMENT’s organizing tradition in the state. Its full-time President is Hollis Watkins, who was one of SNCC’s first Mississippi recruits. It describes its “underlying goal [as] to empower local communities through effective community organizing work…to create a process through which community people can build broad-based organizations necessary to hold…systems accountable to the needs and interests of the African-American community.”

The Blues were born in the 1920s in the shacks and “juke joints” of the Delta. In Clarksdale, a Delta Blues Museum celebrates that history.

I stopped to talk with the museum custodian, a man in his 60s who remembered the bad old days, and whose father was part of THE MOVEMENT. I gave him a poster (I brought about a dozen of them with me for this purpose) that includes the photo of Bob Moses, Martha Prescod and me. He shook my hand for what seemed like minutes, excitedly thanking me for coming down to his state some 50 years ago. “You all did good things back then,” he exclaimed.

“Mrs. Hamer,” as we all called her even when we knew her pretty well, is a legendary leader of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party. She electrified the country with her speech to the Democratic Convention’s Credentials Committee in 1964 (here and here). Here’s her conclusion: “Is this America, the land of the free and the home of the brave, where we have to sleep with our telephones off the hooks because our lives be threatened daily, because we want to live as decent human beings, in America?” At the time, the TV networks were angered by a last minute, no-content, news conference called by President Johnson with the obvious purpose of pulling the cameras from Mrs. Hamer’s speech. So they re-played it several times. Delegates on the convention floor cried when they heard her.

Mrs. Hamer was one of the early people to go down to the courthouse to register to vote. She was told by her plantation owner to remove her application or she would be fired. She didn’t, and was. Her house was fired into a few nights later; luckily, no one was killed. She refused to budge, and went on to become a nationally known leader. She is a heroine of THE MOVEMENT.

She later established a pig farm coop, and provided food to both black and white people in and around her country who were living on the edge of starvation. The pig farm was run in an interesting way. Hungry families were given two piglets, a male and a female. When these pigs had a litter, the family had the responsibility to give a male and female pair to another hungry family. Both whites and blacks were beneficiaries of this program, and I’m told the relationships among them were often good—indicating that the wall of racism can be broken relatively quickly if the circumstances are right.

The Fannie Lou Hamer Museum is small, but its collection includes graphic documentation of those earlier times. Photos of Mrs. Hamer, a reconstruction of the shack she lived in, flyers and other documents from the period are all there. We were fortunate to show up when the curator was there on other business. (The museum was officially closed.) She took us on a personal tour. A few hundred yards away there is a Fannie Lou Hamer shrine and burial place. It brought back vivid memories of the times I was with her. In 1963, I went through Ruleville and visited her after purchasing the 1963 memorial issue of Ebony Magazine that celebrated the Emancipation Proclamation. She loved going through it with me as we sat in her house. I bought it for myself—and on my $10 a week income it was pretty pricey. I left it with her as a present. Seeing her joy at reading that history was a far greater satisfaction than having the magazine.

I also remember Mrs. Hamer at the infamous Peg Leg Bates SNCC staff meeting of December, 1966. (Bates was an African-American one-legged tap dancer who supported good causes.) I arrived to bid adieu to my friends; I was on the way to Kansas City, MO to direct Saul Alinsky’s black community organizing project. When the vote to exclude whites from the SNCC staff passed, Mrs. Hamer was in tears. “Mike,” she said to me, “I just don’t understand what they’re doing.” Her deep Christian faith told Mrs. Hamer we are all children of God. It was the last time I saw her. She died of cancer about 10 years later.

I rented a car in Jackson, and drove to Diamondhead, which is on the Gulf, and visited a friend there. There are still foundations with nothing standing on them–testimony to the power of Hurricane Katrina. My friend lives back from the water, and about 40 feet above sea level, so her house wasn’t touched.

We talked a bit about the recent election. A Tea Party candidate was defeated in the Republican run-off because blacks “crossed over” from the Democrats and voted for his opponent in sufficient number to affect the outcome of the election. An unusual provision in Mississippi law let registered Democrats (which is what most blacks are) vote in the run-off election between two Republicans.

The nominated Thad Cochran is better than the candidate he defeated. But the Mississippi potential is for someone and something much better. I hope the potential will be realized. The pieces and the legacy for something strikingly different are there.

“Of course you need programs and issues to build power. But these are two distinct things, and need to be understood in their own terms.”

(P): Mississippi summer was such a seminal time in our movement history for issues of race and class. What is the legacy of Freedom Summer for these issues, positives and negative?

(M): As your question suggests, there were positives and negatives. On the positive side, the Mississippi Summer Project (MSP) (here and here) broke the back of legal discrimination in Mississippi. Barriers to voting, equal access in public accommodations, state and private-violence against blacks who in any way spoke up, hiring in many areas and other features of what had been an apartheid state ended soon after MSP. Of course nationally there was a climate of support for civil rights. In 1965, Martin Luther King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) led the Selma-Montgomery march which was another major pressure to get the national government to enact voting rights, and implement those rights by sending federal marshals to the south to implement them. MSP brought about 1,000 people to the state. Three hundred of them were volunteer legal, health and other professionals; the rest were predominantly middle-to-upper middle class northern white students from major colleges and universities. Within days, a couple of them, along with a local black activist, were murdered by Klansmen operating in conjunction with law enforcement personnel (here; here). The national pressure that resulted forced federal action. It is possible that without the MSP Mississippi terror might have broken THE MOVEMENT—as it did in the 1955-60 period.

There were negatives as well, and they are more difficult to measure. In some projects, newly emerging local black organizers were unintentionally pushed aside by self-confident northern whites. Local organizing and organizers got lost in the “big picture.” Voter registration and other “programs”* became ends in themselves as distinct from interim objectives that contributed to building power to address more recalcitrant problems, particularly economic and educational opportunity.

*(freedom schools, community centers, the Democratic Party’s convention challenge to seating the Dixiecrat racists by the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party’s (MFDP), and the challenge to seating the elected Mississippi racist congressmen at the January, 1965 opening of Congress)

(P): There was focus on the MFDP challenge at the Democratic Convention in 1964. Was such a focus to the detriment to or complimentary to more grass roots power building?

(M): The slow, patient, work of building local units of people power was absorbed in the highly visible Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party’s challenge to the seating of the racist Dixiecrats at the 1964 Democratic Party convention. (here and here): The discussion is generally cast as a moral one. As Fannie Lou Hamer put it, “We didn’t come here for no two seats.”

More broadly, “programs” (voter registration, community centers, freedom schools) trumped organizing for power. This subtle distinction is lost on most people. Of course you need programs and issues to build power. But these are two distinct things, and need to be understood in their own terms. When you look at things from a power-building perspective, you are interested in questions of capacity—can we do this and grow stronger as a result? You can, for example, win a major campaign on an issue and leave nothing on the ground afterward. Or, you can run a wonderful Headstart program (as the Child Development Program of Mississippi was) but find all your energies absorbed in it with none left to continue on the road to greater democracy, freedom, equality and justice. You get a big win, or build a great program, but there’s no organization and movement left.

And you have to be wary of the downsides of good, big programs. Here’s a comment from a local black Mississippian:

“[W]hen Head Start got into the county, that split up everything. When they got the pre-schools…our leaders all jumped out of our organizations, our Freedom Democratic Party, and went for those jobs. That left the peoples that were following. Y’know how that is when something happen to a leader and nobody else can really just go on. They had peoples to take over, but didn’t have nobody strong enough to know the issues and follow them up…Then those poor peoples who had all interest in these leaders, they started saying, “They using us to get everything for themselves!” Which it was true. It was sure enough true.”

The answer to your question is not an unequivocal one. Things might have been done differently. What disappointed me about the reunion was the absence of a critical look at what we did then that might have informed what is being done now by a whole new generation of organizers, activists and leaders.

What if MFDP had asked for half the seats instead of all of them—i.e. a split delegation? Granted, that would have been an implicit acceptance of the racism of the “regulars.” But wouldn’t that have made an interesting proposal? Had it been granted, and had the regulars remained at the convention, they would have found themselves in an “integrated” Mississippi delegation—more accurately one characterized by equal voting rights. Of course they wouldn’t have stood for that, and would have walked out—as they did anyway even after MFDP rejected the two seats at large offer. Would the split delegation proposal have won additional credential committee votes? Might it have blunted the fear of white voter backlash expressed in now-released private tape recordings of Lyndon Johnson rounding up votes to deny MFDP’s challenge? Would it have made a difference with labor, liberal and other allies? We have no way of knowing. But on the face of it, I think it might have been a better proposal.

Indeed, it is arguable that even the two seats at large might have presented MFDP with a wedge into 1968 recognition as the official party from the state. Instead, the labor-liberal-national civil rights leadership alliance bypassed MFDP, and created a new “moderate” Democratic Party in the state.

I don’t have a firm view regarding these options. I am convinced of the importance of learning by evaluating the past.

In part 2 a Mike Miller addresses the question:

Harvest of Children

By Myrna Santiago

Make no mistake about it: the children detained on the US-Mexico border and those winding their way north from Central America are the legacy of US intervention in the region in the 1980s and beyond. Guatemala was left in shambles in the wake of the genocidal war successive military regimes waged against its indigenous population with Washington’s blessing since the US government overthrew the Guatemalan president, Jacobo Arbenz, in 1954.

El Salvador’s attempted revolution stalemated the military regimes after the United States poured a million dollars per day into counter-insurgency for a decade. The result was not only the death of tens of thousands and a shattered economy, but also a country awash in weapons of war. That armament became readily available to young men deported from Los Angeles who took home a new modality of social organization: the “maras,” the gangs they formed in exile to negotiate the mean streets of Southern California and that now terrorize El Salvador.

Honduras was likewise affected. The Reagan administration used the country as a massive military base throughout the 1980s to battle the Sandinistas in Nicaragua and the FMLN in El Salvador. In the process, the United States government weakened Honduras’ institutions even further, the coup de grace finally arriving in 2009 with the ousting of President Manuel Zelaya. Honduras became ripe for the double plague its people can endure no longer: a transfer point for drug shipments going from Colombia to Mexico and a breeding ground for youth gangs engaged in the trade, in addition to other criminal activity.

In both El Salvador and Honduras, the gangs have created mayhem of all sorts, inflicting violence upon the population with no apparent end in sight, always hungry for new, young recruits. It is that violence, with its roots in US foreign policy toward the region, that has pushed parents to do the unthinkable: to send their children to the United States unaccompanied by family members. The fear of having their children snatched by the gangs and inducted into them (under threat of death) is greater than the fear of human traffickers.

As a consequence, the US government now faces a compounded immigration problem and the human tragedy of the massive incarceration of children. And given the Republicans’ determination to oppose, deny, and derail every single policy proposal coming from the White House, it is hard not to be pessimistic about the future of those children. President Obama is asking Congress for more funding to do more of the same: to use his executive powers to deport immigrants by the millions. That might be the only proposal he will find bipartisan support for in Congress. After all, can anyone really expect that those who created the problem in the first place would be willing to fix it in a humane, just way?

00#7 Making NECCO Wafers – Fall 1972

By Peter Olney

“All-day suckers and lolly pops

Maple fudges and chocolate drops!

Wares that satisfy; goods that please!

Who sells lovelier things than these?

Who among all of our working clan

Has a happier trade than the candy man?”The Candy Man by Edgar Guest

I arrived back in the USA in late August of 1972 deplaning at JFK in New York City where I had started my Italian adventure the previous year. I had one small bag, and stuck my thumb out and hitched to Boston. I checked in with my parents in Andover and then headed for The Hub and my friends from the Lewd Moose commune of the summer of ‘71. Two of them, Buck and Steve had bought a house on Pine Street in the same Central Square neighborhood where we had lived together. I was invited to stay, along with half of the street lumpen kids from East Cambridge. My bedroom was in a dank basement that would flood occasionally and I would wake up and stick out my hand for a depth reading before trying to climb out of bed.

Steve and Buck, being movement entrepreneurs, had the idea that they could fund the movement by raising money with events featuring progressive rock stars and cultural icons. The initiative was called “Entropy” and they became mildly successful promoters. One day I remember being told not to barge in on the master bedroom because Allen Ginsburg was using it for some pre performance meditation. There sat the rotund rollypolly Ginsburg oohming in the upstairs bedroom. I think I was the only one in the house with a regular job, which conveniently was a stone’s throw up on Massachusetts Avenue at Albany Street at the New England Confectionery Company (NECCO). NECCO is famous for NECCO wafers and for the Whitman Sampler chocolate assortment box gifted on Valentine’s and Mother’s Day.

My decision to work at NECOO was not the product of deep scientific analysis. I needed a job to support my self, and my Italian experience inspired me to want to be a part of the US working class. I thought that any radical change in America would come from building a strong workers movement, like the one I had seen in Italy.

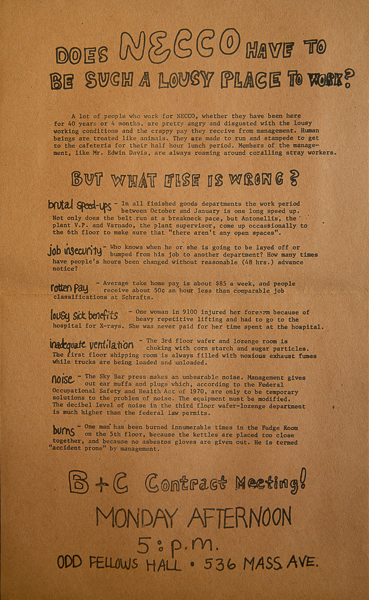

Like so many other workers in my experience they referenced the good old days when working at NECCO was like being part of a family.

My job at NECCO was to start work early at 5 AM, just when the frequent all night party was winding down at 51 Pine Street. I was the freight elevator operator, and I received a license from the Commonwealth of Massachusetts to operate. My job was to carry raw materials and workers, mostly older ethnic Italian, Portuguese and Irish ladies up to the production floors. I enjoyed practicing my Italian with the ladies who mostly spoke Sicilian and Neapolitan dialects. I soon became attuned to some of their issues in the workplace. The clanging noise of “Rolo” and “Skybar” molds being hammered to release the product drove the noise decibel levels over 90, unsafe for human ears. The cold storage area for the filberts and peanuts used in the chocolates was infested with rats. There was a human element to the pestilence also that tamed any desire for milk chocolate on my part. Manny, an older Portuguese worker from the Azores loved to stand in front of all the other male workers in the early AM, and relieve himself into the chocolate vats. I started to talk issues with the women as we rode the elevator, and of course I had a captive audience because I could stop between floors and hold forth with my opinions about their working lives. Like so many other workers in my experience they referenced the good old days when working at NECCO was like being part of a family. Change started to happen in 1962 when NECCO was purchased by the United Industrial Syndicate (UIS) out of New York. UIS was a publicly traded conglomerate that was in the business of picking up manufacturing companies and squeezing their assets for super profits. The women were victims of that drive for increased profitability. The plant manager, Tom Antonellis, a former Boston College football star, would come down on the assembly line and fill up the line with Whitman Sampler boxes so that the ladies had to work even faster during the holiday season.

My employment at NECCO was short lived because of a classic moment of youthful idealism. The Vietnam War continued to rage, and I continued to have my strong feelings about US imperialism. At one point I came to work early and scrawled “Victory to the NLF’ on the elevator walls. I am not sure that Victory to the National Liberation Front, the Viet Cong, was an educational and teachable moment for my elevator passengers most of who didn’t speak or read English let alone know who the NLF was. But there it was penned in magic marker on the wall. It did catch the attention of management, and I was summoned to the Personnel Director’s office. The director was an old blue-blooded Bostonian who probably was given the job as a life cushion after graduating from Harvard. He wore a natty bow tie and proceeded to lecture me calmly about the offense I had committed, defacing company property. He said however, “I understand people have strong feelings about these issues, and if you will promise not to do it again you can keep your job.” I immediately expressed my strong feelings, “Absolutely, I will NOT promise never to do it again”, and I swiftly exited the chocolate factory in December of 1972.

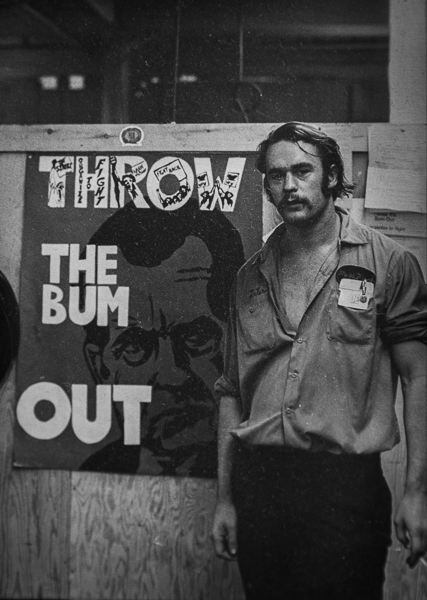

I arrived early and was chatting with some of the Italian ladies when two giants in leisure suits from the BCT approached me.

Even though I was on the street my involvement with NECCO and its workforce was not over. I had earlier connected with an organization called Urban Planning Aid (UPA), headquartered in Central Square. This was a movement consortium specializing in technical expertise in communication, health and safety and other organizing skills. I was particularly interested in health and safety issues given some of the deplorable conditions at NECCO. The labor contract was expiring at the end of January, 1973 for the workers. They were in union Local 348 of the Bakery Confectionery and Tobacco Workers Union (BCT). I decided with the help of UPA to do some street agitation about the health and safety conditions hoping that the union would be spurred to address them with the company. I call it “street” agitation because I was out on the street handing out flyers calling out the noise and the rats in the peanut bags. I got a nice welcome from my ex-elevator passengers who appreciated seeing me in the biting winter cold handing out the newsletter. The BCT was not so hospitable.

I went to the first union meeting of my life on January 22, 1973. The meeting was scheduled in order to update the members on the BCT contract negotiations with NECCO. It was on the second floor of the Odd Fellows Hall at 536 Massachusetts Avenue in Central Square. I arrived early and was chatting with some of the Italian ladies when two giants in leisure suits from the BCT approached me. I was no small lithesome guy, and still they proceeded to pick me up in a fireman’s carry, dragged me down the stairs and deposited me outside on Mass Ave. The contract was ratified and didn’t deal with any of the issues I was agitating about. I have learned that health and safety issues are often of utmost importance to workers, because while pay and benefits are fundamental, the breaking point that often spurs action are issues of human dignity that involve life and limb and safety and health. That was true at NECCO and has been true in every workplace I have organized since.

Of course in retrospect I might have been more effective at NECCO if I had told Mr. Blue Blood, the Personnel Director, that I would promise of course never to deface company property. Then there would have been no legitimate basis for the BCT goons to throw me out of the meeting and I would have had the daily ear of the workers on my elevator. But those were times of high idealism and little political seasoning. I chose principle over pragmatism and who paid the price?

Writing in my journal on December 22 I characterized my decision as “Stupid honesty” and reflected that I had let “Pride and a moral code that you have rejected intellectually, determine the decision”

Next – OO#8: Mass Machine Shop and the United Electrical Workers (UE)

Lillian R. Rubin – On Tuesday, June 17, my friend Lillian R. Rubin died. She was 90 years old. I was scheduled to have lunch with her on Friday, June 20 at Garibaldi’s restaurant on Presidio in San Francisco. I would arrive there for my monthly luncheon with her and ask for Dr. Rubin. The maître de would usher me to her favorite table at a corner spot in the back of the restaurant. Lillian was a sociologist, psychotherapist and doctor in psychology from Berkeley and an accomplished writer and commentator on matters of class, race and family in America. I had read her most famous book, Worlds of Pain: Life in the Working Class Family, as a young organizer in Boston almost 40 years ago so I was thrilled to meet her through a mutual friend in SF. Lillian was a woman who led an extraordinary life, and I will leave it to others who knew her longer and better to tell her story.

Here is her daughter Marci’s tribute and here is the obituary published in the New York Times

Lillian was a writer/mentor constantly challenging me to begin each essay with a paragraph telling the reader what I was going to write about. She would admonish me to go deeper and stop with the bland “encomiums”. I will miss her sharp edits of my essays. I hope that I have improved a little bit because of her coaching. She is missed in my life.

Recycling Workers in Their Own Words.

By David Bacon

The following stories, told to David Bacon, first appear in the San Francisco Bay Guardian Online 10 June 2014

Cristina Lopez and her two sons. (Lopez’ name has been changed to protect her identity)

I first applied for a job at the Select agency in 2000. I’d just arrived from Mexico, and a friend explained to me about the agencies, that they’ll quickly send you out to work. They sent me to some other places before ACI. Then I was out of work for awhile, and I went down to the agency to ask them for another job. They said the only job they had for me was in the garbage.

A lot of people had told me that this job was really bad. The woman at the agency told me, go try it for a day, and if you don’t like it you can come back here. So I went. At first they put me on the cardboard line. That didn’t seem so bad because it’s not so dirty. It’s just that the cardboard stacks up so fast. But then they put me on the trash line, which was a lot dirtier. But the thing is, I needed the job. So I worked hard, and the years passed, and I was still there.

All day every day the trucks arrive, they unload and a machine starts pushing the trash onto the line. Down below, we start sorting it. The line brings all the trash past the place we’re standing, and first we separate out the cardboard. The next line takes out the plastic. Then the metal and aluminum gets taken out on another line.

The worst position — the one with the heaviest and dirtiest work — is the trash line. It’s really ugly. All the really terrible things are there. Things like dirty diapers. There are dangers too. Broken glass. Rusty iron.

I got punctured twice by hypodermic needles, and they sent me to the hospital. I was really scared, because you don’t know where the needles have been. You could get HIV. They kept checking my blood at a clinic in Castro Valley for eight months afterwards, for AIDS or hepatitis or other illnesses.

Afterwards Maria at the agency said the company had checked my papers and found out that they weren’t any good. I wouldn’t be able to work anymore if I couldn’t give them new papers within a month. I told her I wanted to see this in writing, and I’d take it to a lawyer before I signed anything. I told her, “With the lousy wages you’re paying us, do you think you’re going to find people with good Social Security numbers?”

After the month was up they didn’t say anything. I knew three people after that who were called into the office after they’d been punctured by a needle, and the company then checked their papers. But they lost their jobs because they didn’t speak up the way I did.

The heaviest job is separating out the metal and taking it to the containers. Once I was sorting on the line and a heavy piece of equipment fell on me. It really hurt me bad, but they didn’t pay me anything for that or send me to the doctor or the hospital. Last November I slipped and fell while I was putting a cylinder on the forklift, and it hit me in the stomach. They didn’t do anything for me that time either. They just sent me home. They always look for a way not to send you to the doctor when something happens.

We don’t have any medical insurance. They tell us that because we work for the agency, we don’t have a right to this benefit or anything else. No vacations. Nothing. They call us temporary workers because we work for the agency, but we’re not really temporary. Many of us have been working at ACI for many years. We are permanent workers there. But ACI doesn’t have any of its own employees on the sorting lines. Down there we all work for the agency.

When I started at ACI they were paying me $8 an hour. They made us work ten or twelve hours every day, standing in one place all that time. If we got sick and asked for time off they’d deny it. Every Saturday was mandatory. If we stopped the line to get a drink of water because it was so hot they’d get angry. If we went to the bathroom, they’d look at their watch to see how much time we were taking.

Then in 2012 they started two shifts and raised the wages to $8.50 for nights and $8.30 for days. I don’t think that’s a fair wage. The job is very heavy and the pay is really low. In one safety meeting I asked them to give us a raise. Then the manager yelled at me and called me a grossera because I said the company was greedy. Afterwards he told me I had to go apologize in the office.