Mass Murder in a Culture of Vengeance

By Terry Kupers, M.D., M.S.P.

Mass murders like the massacre at the First Baptist Church in Sutherland Springs, Texas, on Sunday give us pause. Long pause. What is causing all of these atrocities? In this case, the murderer had a history of domestic violence.

There certainly is a connection between domestic violence and gun violence. Could that connection help us understand the violence?

Or there are extraordinary weapons like the bump stocks Stephen Paddock used to kill 58 people in Las Vegas a few weeks prior.

Is it the easy availability of rapid-fire military-grade armaments that lead to mass murders?

Do we need laws restricting gun possession by perpetrators of domestic violence, and laws restricting the purchase and ownership of military grade rapid-fire weapons? Of course we do. But there is something else about the Texas church massacre that deserves attention. Vengeance. The shooter did not have a rational target, and like most mass murderers killed randomly. But he was clearly acting out of vengeance, as was Stephen Paddock and others.

Vengeance is a quintessential human sentiment. It is one of our capacities, just as generosity and forgiveness are human capacities.

It’s much easier to draft laws prohibiting certain gun sales, such as giving guns to men who beat women, than it is to come to grips with the social problem of vengeance. I have arrived at a very simple formulation about vengeance and problems like gun violence. A backdrop of heightened vengeance in our mass culture is almost a prerequisite for large scale gun violence. I’d better explain. I will begin with a parallel in sexual assault within women’s prisons – stay with me, the relevance will become apparent. Generally, in men’s prisons rape is prisoner-on-prisoner, but in women’s facilities it is more often staff who perpetrate sexual abuse and rape. When I testify as a psychiatric expert witness in court on behalf of women who have been sexually abused by staff, I point out that the sexual abuse would not be so pervasive absent a culture of misogyny in the women’s prisons. Women prisoners, some of whom are older than officers, are regularly called “girls” and are disrespected at every turn. They are searched frequently by male officers who linger over their breasts and crotch. The misogyny is so commonplace it becomes “normalized,” and women feel that unless they are actually raped there is no use reporting the daily sexual harassment. This culture of misogyny is a necessary backdrop for the actual rapes and serious sexual abuse that occur all too often.

Similarly, where it is quite obvious how much vengeance is a part of the picture when a man picks up military weapons and opens fire on a crowd – he is getting back for some past episode that sticks in his craw even if his targets are not rationally connected to those who previously did him harm – but we rarely give a thought to the way a culture of heightened vengeance constitutes the necessary backdrop. Vengeance is a quintessential human sentiment. It is one of our capacities, just as generosity and forgiveness are human capacities. But certain experiences bring vengeance to the fore, for example unfair treatment at work, gross disrespect, the murder of a loved one, or the very high-profile murder of someone else’s child. We have the impulse to kill the murderer in revenge, or in more legal fashion, we may feel driven to seek the worst punishment possible in court, even death. In other words, the pervasiveness of vengeance in our mass culture and the media varies with historical events and the times. I think it’s clear that mass murders, though they remain relatively infrequent occurrences, are on the upswing. Could the upswing have something to do with the fact that vengeance is increasingly prominent in our social interactions and sensibilities today? We have a President who brags about groping women. We have hate crimes on the rise, with less and less effort from the federal government to do anything about their causes. We have openly anti-immigrant, xenophobic and homophobic statements emanating from the President and other leaders in Washington. All of this fuels a culture permeated by vengeance. I often feel I am even seeing it on the freeway. During more friendly and less vengeful times, if I near an exit and need to change lanes the drivers in that lane will slow and let me pass, but today they seem more often to speed up and cut me off, even when they know it means I will miss my exit. This is a very subtle form of vengeance, but it is one tiny reflection of increased vengeance in our culture, and there are many others. It is not only immigrants who are suffering in our vengeful society, there is simply less kindness around; for example there is little will in government to consign funds for programs disadvantaged people need to keep their heads above water. Our President is so vengeful that when a politician criticizes him he ups the ante in crude counter-attacks, and after a mass murder he immediately calls for the murderer to be executed. Of course he errs by disrespecting the separation of branches in our federal government, but also the reflex call for state-sponsored murder of the murderer feeds the general sense of vengeance in our culture today.

For more thoughts on an American way of death:

The Guardian of 6 November 2017: “The heartbreaking stupidity of America’s gun laws” by Richard Wolffe

The New York Times of 6 November 2017: “What Explains U.S. Mass Shootings? International Comparisons Suggest an Answer” by Max Fisher and Josh Keller

Saggio #5 – “Kap e Berni” – Poltica e Lo Sport

By Peter Olney

It would require full time attention to English language media to keep up with all the controversy surrounding Donald Trump’s attacks on NFL players. My heart is warmed to see players from America’s most popular game standing up against the Trumpster and in support of justice not only for African-Americans but all those being abused and left behind. It was heartening to see some white players finally speak out. Meanwhile Colin Kapernick remains on the “blacklist” for his courageous acts. I decided that it was time to find out a little of the political history of sports resistance to Mussolini in Italia. Italy’s biggest sport of course is “Calcio”, what the world calls Futbol and we call soccer.

I rode my bike on September 29 to the neighborhood of Coverciano where the Italian national team has its lavish training center. In the same location there is the National Calcio Museum dedicated to the history of Italian soccer and particularly Italian triumphs in the World Cup – 4 in all. I parked my bike outside the gate and pressed the doorbell as instructed. I was buzzed into a small ticket office where an elderly gentleman in a three-piece suit sold me a ticket and then led me into the museum. I was the only customer, and he spent time with me explaining what was in the museum and how to find different exhibits on its three floors. Turns out this gentleman is Dottor Fino Fini and he was the national team physician from 1962-82. Of course 1982 was the first World Cup post WW II and post fascism. I made the mistake of asking Dottor Fini his name, and I think he was truly offended to think that a calcio fan visiting that museum would not know who he was.

The museum was very extensive with historical exhibits tracing the game’s origins back to the 19th century when Brits brought the game to the seaport of Genova. The early Italian teams were in the industrial north and were often linked to manufacturers like the giant FIAT automobile plant, which sponsored and later owned the Club Team Juventus. (Juventus is a bit like the NY Yankees having won 33 “scudetti” or championships.)

Mussolini and the Fascist party took power in 1922 and realized the potential of calcio as a national unifying force. In fact Italy’s premier league, Serie A, was created under Mussolini’s reign. Italy’s first two world championships, in 1934 at home in Italy against Czechoslovakia, and in 1938 in France with a victory against Hungary. The museum has a grainy photo of Mussolini welcoming the whole team to Rome in 1938 dressed in military uniforms.

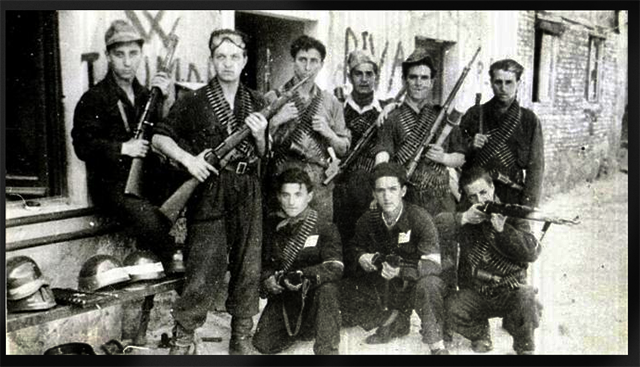

1931: Before the opening whistle it was the custom for the players to salute the dignitaries seated in the “tribuna” with “il saluto Romano” the fascist salute. Bruno Neri refused.

I am not sure that this tradition of political leaders welcoming teams to the capital began with Mussolini, but it has certainly become a point of controversy in he United States as a focal point for protest against administration policies. There is the famous case of Craig Hodges, a journeyman member of the NBA champion Chicago Bulls, who went to the White House of President George HW Bush in 1992 wearing a dashiki. He presented the President with a statement asking him to do more to end discrimination against African Americans and was subsequently blacklisted ala Kapernick. He never again played in the NBA. During the twenty plus years of fascism in Italy there were many examples of political courage and protest by athletes, principally in Italy’s most popular sport of “calcio”. One of the best examples of athletic courage and principle were the defiant acts, and the ultimate sacrifice to the Partisan cause, of one Bruno Neri. This midfielder, who played from 1929-1936 on the squadra la Fiorentina, made a statement ala Kapernick when the new stadium in Florence was inaugurated in 1931 with a friendly between Fiorentina and Admiral from Vienna. Before the opening whistle it was the custom for the players to salute the dignitaries seated in the “tribuna” with “il saluto Romano” the fascist salute. Neri did not raise his arm. He was not the only player to refuse to salute, but he was unusual in that he later went on to become a Vice Commander of the Battalion Ravenna of the Italian Resistance.

Bruno Neri not only player refused to salute, he later fought with Italian Resistance and was killed in 1944

“Berni” (his nom di guerre) was killed by a German bayonet in 1944. In Italy modern on field protests have mainly taken the form of solidarity with African players who reactionary, racist, and fascist fans have pelted with bananas. Games have been stopped and players from the home teams have made direct appeals to their own home fans to knock it off.

I closed out my visit to Coverciano with a stop as at the exhibit case that celebrated Italy’s amazing World Cup 4 overtime win in the semi-finals against West Germany, in Mexico. That was in 1970 and I happened to be in Italy for the first time that summer, and I have never seen such a sports mad country. Every fountain in every public square in Italy was filled with fans carrying the Tri-Colore in the aftermath of the dramatic semi-final. For the final against Pele and Brazil it seemed like a neutron bomb had hit; all of Italy was indoors watching and cheering on “Gli Azzurri” (the Blues, the color of the Italian team jersey). Italy succumbed in the final 4-1.

I finished my tour of the Museo del Calcio and closed the door behind me. I walked to the “biglieterria” and said goodbye to Dottore Fini and pedaled home.

On Monday, October 23, the politics of racism and anti-Semitism took a bizarre and alarming twist in Italy. Sixteen super fans, or “Ultras”, of the Roman squad Lazio were caught on tape affixing stickers onto the South Curve of the Olympic Stadium that bore a picture of Anne Frank photo-shopped wearing a jersey of their arch rivals, AS Roma. This along with other stickers that said “Romanista Ebreo” was a sick and twisted way of slamming the fans of the other major team from the capital city; a team long associated with the left. The reaction of Serie A, the league, was swift, and a passage of the Diary of Anne Frank was read aloud before the opening of all subsequent matches throughout Italy. Many teams wore jerseys inscribed with “Noi siamo tutti Anna Frank”, “We are all Anne Frank”. I have often vigorously argued that you can’t understand politics or connect with a people, especially the male species without understanding their sports. I must admit however that I was confounded by this incident and had to read the Italian newspapers over and over again to figure out what the Diary of Anne Frank had to do with Serie A. Many of the “Ultras” have long been associated throughout Europe with right-wing, proto fascist politics, but I was pretty stunned by the evil “creativity” of the Lazio fans.

Saggio #4 – Pracchia e Lorenzo il Magnifico – September 14, 2017

By Peter Olney

Our friend Giuliana Milanese from Bernal Heights in San Francisco arrived in Florence on September 12th as part of her month long family and friends tour of northern and central Italy. Giuliana was raised in Oakland by two Italian immigrant parents, and she has maintained her deep ties with family in Liguria, Toscana and Lombardia. Her visit to Firenze was predicated on my willingness to accompany her to Pracchia in the Province of Pistoia, northwest of Firenze bordering on the region of Emilia Romagna. Why Pracchia? My Italian friends for the most part had never heard of this little mountain town, but Giuliana had a dear uncle who lived there for many years, and she was accustomed to visit him on her Italian sojourns before his passing a few years ago.

On September 14th we left for Pracchia. Christina was in her intensive Italian class so Giuliana and I were joined by her two dear friends, Lorella Di Vuono and Viviana Morgante. They are a couple in their thirties who Giuliana had befriended in Bernal. She heard two women speaking Italian, and she chimed in and invited them to spend Christmas with her and her family. LoLo is from Piemonte and Viviana is Palermitana from La Sicilia. They are accomplished world travelers, researchers and raconteurs. LoLo has written a fascinating analysis of the language used in the right-wing appeals of Berlusconi and political groups like Forza Italia and Lega del Nord. This analysis is on a par with the work of George Lakoff, the Berkeley professor who has made deconstructing the strong leader patriarchal appeals of Donald Trump the subject of his linguistic skills.

Left: LoLo, Giuliana and Viviana in the Pistoia train station. Right: An abandoned train station in Pracchia

To get to Pracchia you travel to Pistoia and then change trains. A short ride and you get off at the tiny station. We were the only travelers to get off, and found a deserted waiting room with the exception of two young workers waiting for the train back to Pistoia. They explained to us that now there were only 154 residents of Pracchia, many of them living in a residential home for the aged. They expressed skepticism that we would be able to find anywhere to eat in Pracchia, but off we went for a hike up into Pracchia Alta looking for the old home of Giuliana’s uncle. Giuliana wasn’t able to locate the house, and we hungry hikers were unable to find a restaurant to eat at. In fact there was no commercial establishment open. The only office with public access was the Poste Italiane, and La Postina explained that for food we were in the wrong place. Back to the train station and the next train to Pistoia. However upon arriving at the station the timetable wasn’t accommodating our alimentary needs. There would be no train for another 4 hours!

We saw the COPIT BluBus sitting opposite the train station and climbed on board and asked the driver where we could get some food. He patiently explained that we would have to go to the next town down the road at PontePetri for a meal. He also explained that he would honor our train tickets and get us there. He also explained much of the amazing history of Pracchia and the train system. He told us that the old abandoned station opposite the one where we had got off a couple hours earlier was one of the first RR stations in Italy, on one of the first RR lines in the world, inaugurated in 1864 to connect Pistoia in Tuscany with the major city in Emilia Romagna, Bologna. In 1926 a narrow gauge fully electric service was initiated to connect Pracchia with the small mountain towns of the Lima river valley. This service was under the authority of the La Ferrovia Alto Pistoiese, meaning the railroad serving upper Pistoia, or F.A.P. The service continued until 1965 when it was dismantled, but the old train station where Lorenzo’s bus was parked still carries the initials of the electric railway.

I have been working as a consultant to the Brotherhood of Maintenance of Way (BMW), one of the original US railroad craft unions established in the 1880’s to represent the workers who lay the tracks and maintain them for all the big freight railroads and commuter lines. I have become, in the parlance of the railroad, a “foamer”, that is someone who foams at the mouth over all things railroad. So I saw a railroad yard next to the station and immediately went over to inspect the “binari” and transversini” (the rails and ties) and the track maintenance equipment, the same materials and gear that I would encounter in a train yard in the Bay Area.

Then Lorenzo drove us in his empty bus down to PontePetri where we ate a wonderful lunch at his favorite restaurant, Quarteroni, a Macelerai e Alimentari (butcher shop and food service). He explained that he would pick us up after lunch on his regular run and take us back to Pistoia where we could get a train to Firenze. Like clockwork, he showed up across from Quarteroni and we were in Pistoia within 45 minutes. He insisted on escorting us personally to our track in Pistoia. We thanked him as he left to drive home to his young family in Agliana. We dubbed him Lorenzo il Magnifico, no Medici he, just a big hearted Italian bus driver. I made sure to gift him a lapel pin from the BMW, which he proudly affixed to his BluBus uniform when we said goodbye.

Saggio da San Frediano #3 Poeta Romagnolo – Arnaldo Morelli

By Peter Olney

On the first weekend of September we were privileged to travel to the Camugnano region half way between Florence and Bologna where we were hosted by our dear friends Franco and Marinella at their “Casa in Campagna”. This is a beautiful foothill area in the Italian region of Emilia Romagna, and is north of Tuscany where we are situated. They bought half of an old farm house 14 years ago and transformed it into a beautiful hide away. They are in the village of Carpineta and their neighborhood is called Le Piazze. In Le Piazze they have gotten to know all their neighbors and pass many hours eating, drinking and conversing with a diverse set of friends some of who have roots back generations in Carpineta.

On our first night we met Anna Montanari and Arnaldo Morelli, both very engaging human beings. Anna is over 80 and has led a fascinating life of struggle and commitment to the working class and the left. She has worked in the rice fields of Emilia Romagna (Here and Here), among many other jobs. In her latest job she made tagliatelle and we hope to see her again for a taste of this wonderful homemade pasta. While we were with her over the weekend she made “Friggione”, a mysterious but delicious mixture of onions, tomatoes and a small amount of lard with sale-e-pepe.

Arnaldo Morelli, a retired cement mason and active poet. He writes in the regional dialect of Emilia Romagna – Romagnolo. Photo: Peter Olney

Anna’s companion is Arnaldo Morelli, a retired cement mason and active poet. He is a poet in the regional dialect of Emilia Romagna – Romagnolo – His work has been recently published in a book entitled Vosi Da E Bur or in Italiano Voci dal buio (Voices from the darkness). The poems are in Romagnolo with side by side translations in Italian. The translations are necessary for Italian speakers because except for a few words, “non si capisce niente di Romagnolo” (One doesn’t understand anything of Romagnolo) These are beautiful sensual poems that describe natural wonder and are inspired by everyday events. For example, Arnaldo was inspired by Christina’s exotic appearance to write a poem the evening he met her. We would later learn from Arnaldo that Romagnolo is best read aloud because of its natural rhythmic cadence.

The phenomenon of dialects or distinct regional languages within Italy is important to understand. It wasn’t until 1871 that Italy became Italy with the capital in Rome http://www.italianlegacy.com/brief-history-of-italy.html. Until then the peninsula and Sicily and Sardegna were city states with their own language and culture. While national government, commerce and especially TV, radio and newspapers have homogenized language, dialects still remain important and are spoken often, although not exclusively, by the older generation.

Although how old is old? I remember vividly my trip during Christmas of 1971-72 to the region of Puglia in the southeast on the heel of the boot. I was accompanying a fellow student at the Universita di Firenze, Joseph “Pepino” Scarola who was from Dumont, New Jersey. Pepino was born in the village of Grumo in Puglia and at the age of 12 had moved with his family to Dumont. Therefore at the age when he would have begun to study Italian “standard” he was wrested from his village in Italy and began studying English in the schools in the United States. When I met him both English and Italian challenged him. He spoke both well but haltingly with accents, and spoke his dialect, Grumese in the home. Sometimes he found himself the target of jokes and barbs because of his language skills, but when we arrived in Grumo, I saw a man transformed. Whe got out of our VW bus to talk with his welcoming relatives, he spoke perfectly, and with great confidence in Grumese, his home dialect. And if we had gone 10 kilometers down the road, the locals wouldn’t understand Grumese!

Certainly such regional differences in speech exist in the US in Appalachia, the bijous of Louisiana and some islands of the southeastern coast being examples. Not to mention the language variations spoken in different urban areas. However usually there is a common understanding, at least on one side of the conversation.

I will never forget attending a memorial for my dear friend Jim Trammel, who died too young in 2002. Jim was a native of Nashville, Tennessee. I went to a service at his hometown church. I met four of his country cousins, white guys from the hills outside Nashville. I spoke with each one of them individually fine, but when they spoke with each other I was unable to understand a word they said.

On the road to Camugnano in Emilia Romagna. A sign in 5 languages (Italian, French, English, German, Arabic) warning of high water danger. Photo: Peter Olney

While common language remains an important indicator of national unity, the acceptance of different languages is an indicator of societal tolerance and advancement. On our trip to Camugnano in Emilia Romagna I was pleased to see that warning signs of high water dangers were translated not only into four European languages (Italian, French, English and German) but also into Arabic, an acknowledgment of the increased presence of immigrants from Northern Africa and the Middle East.

On our last night in Carpineta, Arnaldo insisted on reading Christina’s poem in Romagnolo which was quite musical and charming. It told of a longing admirer passing below a mysterious woman’s window, inspired by her billowing bloomers drying in the wind… Our adventures continue.

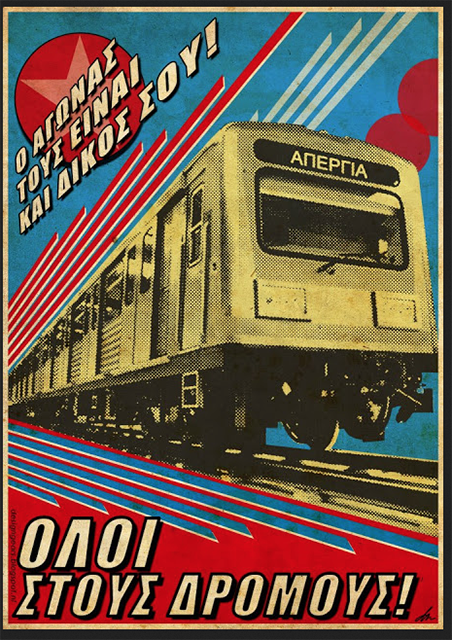

Report from Greece: Preliminary Thoughts 30 September 2017

By Mike Miller

Preface

What I know about Greece and Greek politics can be put in a thimble, and probably a small one at that. So these observations and questions need that preface. As further preface, it is very difficult to apply lessons learned in the United States to anyplace else without contextualizing them in the new setting. That requires intimate knowledge of what is happening on the ground—so what follows are friendly speculations.

All the political Greek people we’ve met have been warm and hospitable in their welcome to us, Americans whose political and economic structures (government, financial and corporate), along with the European Union, European Bank and International Monetary Fund are largely responsible for the mess in which their country now finds itself. To be sure, there is complicity in past behavior and decisions made in Greece. But it’s not these macro questions that I want to consider here.

Local People

We (my partner Kathy Lipscomb* and I) have now met with a public school teacher, taxi driver, waiter (who is also a university graduate in political science), tour guide, night shift security guard and a well known Greek actress ALL of whom blame Syriza (“Who we are” – Syriza) for the current mess, are fed up with politics and politicians (“they are all alike”), and think Syriza (has done nothing for the Greek people or, even worse, point to things Syriza (Here) did (ignore the referendum results), or is doing (see below), that are making things worse.

We have also met with an internationally known political scientist who is active in Syriza, and who is interviewed regularly in various English language left journals, and a Syriza political appointee who is the national coordinator of municipal mayors. The two of them have elaborate explanations for everything Syriza has done or not done. The bad things, in their views, are for the most part the result of constraints imposed upon them by The Troika. They note good things that are done quietly, with no fanfare, under the radar. However, these seem to be so under the radar that none of the other people with whom we spoke mentioned them; indeed they said things that contradicted the claims. Our pro-Syriza informants also indicate that mistakes were made, but they believe these had more to do with Syriza strategy than with decisions that hurt the Greek people.

The clearest example of a bad thing is the story we were told about home foreclosures. There is a high percent of homeownership in Greece. Until recently, we were told, there was an ‘umbrella” that protected a home owner in his/her residence, though it didn’t protect additional property from foreclosure. Syriza, we were told, is responsible for removing the umbrella. Not only that, when the protection was first removed demonstrators appeared at the foreclosure proceedings making it impossible for judgment to be rendered. In response, Syriza made the procedure an electronic one. You now receive an e-mail informing you of the foreclosure as a “done deal”.

Another example we were given, Syriza is further eroding the pensions for which people paid during their work lives. That is a disaster for Greek retirees: there is only a public retirement system. Workers paid 18% of their wage into this system; employers paid 28%. The government has now more than once cut retiree payments.

What is the truth? We are in absolutely no position to tell. I can say with some confidence that not one of these informants was disingenuous; they firmly believe what they told us; none had a pre-disposition against Syriza and, in fact, most of them had been Syriza supporters, and voted for Syriza in the last election. Now, they told us, they either will not, or do not know if they will, vote. And, if they decide to vote, they have no idea for whom that will be.

Is there a way to understand these apparently opposing views of the same facts? There is clearly a participation and perception gap between people we met who were Syriza supporters and those now actively engaged in Syriza. In what follows, I use a framework that I apply in my understanding of what’s going on in the United States. Does the application work? Is it appropriate? I’ll leave that for the reader to decide.

What’s Up?

In a democratic and participatory union, workers may decide to strike because the offer being placed on the table by their employer is inadequate. They might conduct an effective strike, and still be stonewalled as far as any improvement in the employer’s offer. At some point, the workers might decide they’ve put up as good a fight as can be waged, and their own economic circumstances are such, or the increasing presence of scabs is such, that they have to end the strike, return to work, build their strike fund again (if they have one), and wait until the next round of contract negotiations to return to the negotiating table from a position of strength. These workers are not likely to blame their leadership for the failure of the strike. The 1948 Packinghouse Workers Union strike is probably a good example of what I’m talking about.

As every American trade unionist who cares about the future of the labor movement knows, what I just described is, for the most part, a memory of the past. It has been replaced by what people call “insurance policy unions”. You buy your insurance policy (pay your dues) and expect your benefits (advocacy—contract negotiations, and services—grievance representation). Thus the common phrase, “What’s the union going to do about ‘x’?” as if the union is a third party—separate from the member asking the question.

What’s all that got to do with Greece, Syriza, and electoral politics in general? It seems to me in the nature of politicians and political parties in formally democratic systems that the party adopts a program, selects its candidates, and then determines a strategy by which to convince citizens to vote for it and them. But “convince” in the modern era is a tricky word because what it really means is to sell buyers (voters) a product (candidates and their program—which might have little to do with what they actually do if elected). At best, during an election a door-to-door mobilization takes place in which the candidate’s volunteers ask voters to support their candidate. Reasoning is not what takes place at the door because the canvassers are instructed not to waste time with opposition and, at best, to spend limited time with the undecided. Campaign imperatives demand this kind of behavior: there is an election that will take place on an already specified date and a majority of voters is required if the candidate is going to win. This imperative makes mobilization necessary and organization unlikely once campaign season has begun.

It is not by accident that this kind of campaigning takes place. The gap between the political parties and their candidates, on the one hand, and the voters, on the other, is huge. More likely than canvassing, it is direct mail, social media and television advertising that are used to reach the voters (the market). In national campaigns this approach is built into campaign structures: campaign consultants, who are the principal operators of campaigns, are paid by a percentage commission on the cost of the medium used for reaching to voters. Door-to-door work gets almost no money because most of the workers are volunteers!

Even in a campaign that is heavily dependent upon volunteer effort, the contact with the citizen is a fleeting one, and the follow-up is typically electronic, not personal except for election-day when the favorable voter is contacted to insure his or her turnout.

Potential voters do not say about the candidates they support, “What are we going to do about ‘x’ (unemployment, student debt, immigration, etc)?” They want to know what the candidate is going to do about ‘x’. The very nature of the campaign process tends toward the separation of “the campaign”—candidates and their inner-circle, donors, leaders of key interest groups (whose members already think of their organizations as third parties), and activists.

The question then becomes, “How deeply rooted are these activists in the day-to-day lives of the various constituencies addressed by the candidate?”

My friend Herb Mills was chairman of a “stewards’ council” in the International Longshoremen’s & Warehousemen’s Union (ILWU). There developed under his leadership a widespread system of elected stewards at worksites. The stewards worked alongside other workers. There was little-to-no gap between them. They were the point of connection between a worker or a “gang” (a working group that unloaded cargo) and “the union”. There was no gap, no “what’s the union going to do about ‘x’?” question.

In my experience as an organizer, “the activists” typically lack the rootedness in constituencies in whose behalf they believe their candidate will, if elected, act. Frequently they are sociologically very different: young, instead of spread across the age spectrum; “Anglo”, rather then reflecting the racial/ethnic diversity of the constituency; college educated, etc. They are people with whom I might agree on a very high percentage of things they believe. But they aren’t people upon whom I would rely to engage in a continuing conversation with the voters after the election, especially if the person elected had to make a compromise that appeared to violate the platform on which s/he had run as a candidate. Thus the activist isn’t likely to be able, over the long haul, to “deliver” at the base.

Greece Application

Is any of this applicable in Greece? People who know that situation far better than I will have to draw those conclusions. I hope the questions and observations are useful.

I suspect that Syriza and its activists lack the kind of rootedness that is required for everyday voters to say about their plight, “What are we going to do to solve the mess we are now in?” Both our Syriza informants told us nuanced examples of how the organization is now supporting things like soup kitchens, community gardens, homeless shelters and other programs and activities to solve the problems of poverty. They also claimed that Syriza had expanded funding for education, and stopped some bad things from happening to pensions. They see Syriza as having an organic connection with the “social movements”. Yet the school teacher and her security guard husband made no connection between their volunteer time spent in a soup kitchen and Syriza. Similarly, other activities we heard about from our other Syriza-critics (retiree organizations and mobilizations, campaigns to save peoples’ homes, worker strikes, etc) do not seem to be viewed as an aspect of a larger movement of which Syriza is a part. Quite the contrary, Syriza is seen as part of the problem, not the solution.

In the U.S. I think there needs to be a vehicle for “we”, and it is not a political party because the dynamics of parties don’t lend themselves to the effective creation of “us”. Is that idea relevant in Greece?

One of our informants said that when her son arrived at the university to begin his studies there, nine different political parties had registration desks where he could join one of them. But there was no registration desk for a student union that enlisted the vast majority of students around a lowest significant common denominator program that represented their values and interests—for example their indebtedness and the almost 50% unemployment rate their age group faces. Similarly, there is no organization in the community that includes mothers’ clubs, soccer teams, retiree organizations, unions, interest groups of various types and others, and new groups that could be formed among the marginalized. Various interest groups engage in protest demonstrations, but only political parties seek to bring them together. Thus there is nothing outside the electoral politics process capable of defending and advancing a program, and effectively demanding of politicians that they implement it.

Is something like that possible and/or desirable in Greece? I’ll wait to hear from them on that question.

*Disclaimer: My partner Kathy doesn’t agree with all that’s said above. These are my views alone.

Readers of Stansbury Forum might want to look at my earlier post, “Syriza Prompted Musings”. For readers who would like to dive further into Mike’s thinking about Greece, write him @ mikeotcmiller@gmail.com and ask for “Reflections on Greece”.

Saggio da San Frediano #2: Renzi a Firenze

By Peter Olney

Amid the food booths serving everything from Gyros to Brazilian Churrascaria with plenty of pizza intermixed, the Teatro Falcone was the staging area for a public “chiacchierata”, or chat by Matteo Renzi, the ex Prime minster of Italy, now National Secretary of the Partito Democratico (PD), the largest Party in Italy with 283 seats in the Chamber of Deputies. The PD coalesces with other mostly center left parties to garner 394 seats for a secure majority in a Camera of 630 total.

Christina and I were at the Festa de L’Unita to hear Renzi. In many ways the gathering was extraordinary by US standards. The ex Prime Minister (PM) appeared without the presence of armed guards and without any sophisticated pre-screening for a crowd that numbered over five hundred. He spoke alone from the stage without notes or teleprompter to a home crowd of Fiorentini. He engaged the crowd spontaneously with “battute” impromtu and banter with the audience. At one point he compared the improbability of his becoming the youngest Prime Minister at age 39 in 2014 to the seeming impossibility of the home team Fiorentina winning the “Scudetto”, the Italian championship of Serie A soccer/Futbol. His ease with the microphone and back-in-forth reminded me of the skilled and crafty Bill Clinton at his best.

Who is Renzi? Renzi is a local boy made good. Raised in Rignano sull’Arno, a small town in the outskirts of Florence, he was brought up in a strong Catholic political tradition and was a Catholic Boy Scout. A brilliant student, he was also a contestant at 19 on a high profile game show and won 48 million lire (about US$30,000). He also was an accomplished futbol referee in Serie “B” of the Italian Calcio league. At a young age he was elected Governor of the Province of Florence. Than he became Mayor of Florence and by most accounts did some very good things. One among them is the provision of fresh mineral water in many public piazzas. Here in Piazza Tasso we can refill our bottles every day with both “regolare” and “frizzante or gasata”. Renzi became a high visibility leader of the newly constituted PD and wrested control of the party apparatus from Enrico Letta and became PM. In December of 2016 after his first 1000 days he bet his career on the passage of a controversial referendum (Stansbury Forum) that would have reformed the structure of Italian government. In effect he told the voters if this referendum loses, I resign. The referendum lost and as promised he resigned the job of PM. However, now he is campaigning full bore in advance of the regional elections in Sicily that will be a bell-weather for the national elections in 2018.

His commanding performance was in Le Cascine, which is the major recreational park of Florence. This is a public space that borders the Arno and would make Frederick Law Olmstead proud. The Festa de l”Unita is a remnant of the annual festivals in celebration of the Partito Communista Italiano (PCI) whose newspaper was entitled L’Unita. The PD has appropriated much of the old membership (especially demographically) of the PCI and also its annual festival. But no longer are there speeches in support of workers struggles and third world liberation; only cultural presentations and dry discourses from local, regional and national PD figures. Renzi was certainly not a dry presenter. The crowd was partisan to him and warmed to his remarks. The demographics of the crowd however were indicative of the challenge of the PD. Christina and I were about the median age of the crowd. I looked around and figured that 45 years ago when I last lived in Firenze, these would have been the “compagni’ presenti” at a demonstration against the war in Vietnam in the main Piazza della Signoria. The crowd was also exclusively white; no immigrants from Africa or America Latina. My wife experienced the lash of an Italian journalist’s racism and sexism when he tried to dislodge her from a press perimeter that was full of Italian men, none of whom were with the media.

The message from Renzi, while spirited, was a defense of his premiership and the premiership of his successor Paolo Gentiloni, also of the PD. There were facts and figures on growth and jobs, all positive, to combat the slanders of the know nothings of the right. While “fake news” or “alternative facts” are problems in Italy, the problems with economic growth, the environment, youth unemployment are also pressing and daunting. The speech was a defense of the status quo somewhat similar to Hillary’s defense of Barack’s record and that of her husband, Bill. The polls are showing that while Gentiloni is the most popular political figure in Italia, the Movimento 5 Stelle (Five Star Movement led by political outsider and comedian Beppe Grillo) probably will win a plurality of seats in the Camera unless things change radically between now and 2018. The fact-based critique of anti-establishment populism was one major theme of Renzi’s speech.

The other theme was a call for left unity. In February of 2017 a group of PD deputies left the party to form the Movimento Democratico e Progressista (MDP). MDP has 43 deputies in the Camera and still coalitions with the PD and other smaller parties to form a government, but the MDP is refusing to coalesce with a united list in Sicilian regional elections threatening the center left and potentially throwing the election to the right. Many view the MDP’s abstentionism as a shot at Renzi. If the PD loses in Sicily then Renzi’s brand is damaged, and he will not be in position in 2018 to make another run at the Prime Minister position.

This is a delicate dance that recalls the Sanders ballet within and without the Democratic Party. Certainly the 2018 Congressional midterms pose a similar challenge. To recapture the house for the Democratic Party 24 seats need to be flipped from Republican to Democrat. Many candidates may run on platforms that stand for social justice and anti-corporate values, but not all Democrats will be 100% up to snuff on the progressive measuring stick. Is control of the House worth holding one’s nose and voting for an imperfect Democrat? I say yes. Many Italians of the left face similar choices and challenges.

Next in Saggio #3: A poet in Emilia Romagna writes in his native dialect, Romagnolo.

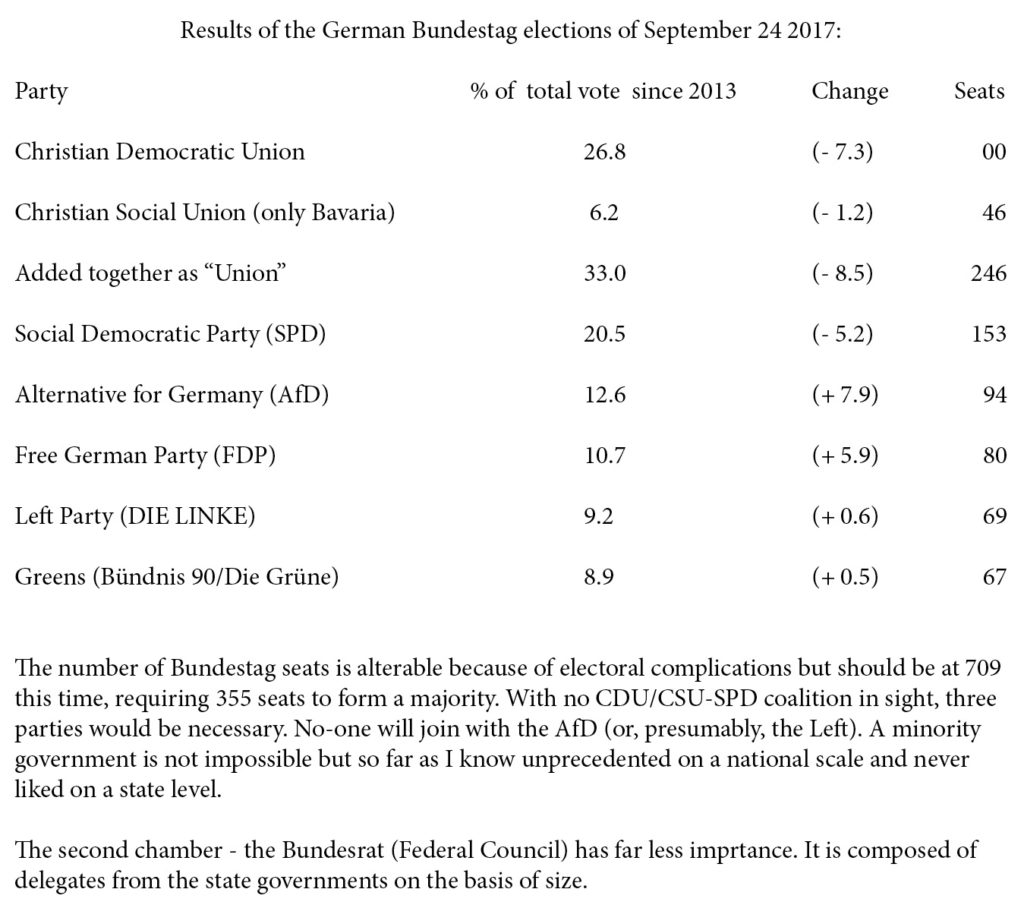

Berlin Bulletin No. 134, September 25 2017: MERKEL CLOBBERED WHILE RIGHTISTS THREATEN

By Victor Grossman

A key result of the German elections is not that Angela Merkel and her double party, Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and Bavarian CSU (Christian Social Union), managed to stay in the lead with the most votes, but that they got clobbered, with the biggest loss since their founding.

A second key result is that the Social Democrats (SPD) got clobbered too, also with the worst results since the war. And since these three had been wedded in a coalition government for the past four years, their clobbering showed that many voters were not the happy, satisfied citizens often pictured by You-never-had-it-so-good-Merkel, but are worried, disturbed and angry. So angry that they rejected the leading parties of the Establishment, those representing and defending the status quo.

A third key story, the truly alarming one, is that one eighth of the voters, almost 13 percent, vented their anger in an extremely dangerous direction – for the young Alternative for Germany (AfD) party, whose leaders are loosely divided between far right racists and extreme right racists. With about 80 loud deputies in the new Bundestag – their first breakthrough nationally – the media must now give them far more space than before to spout their poisonous message (and most media have been more than generous with them up till now).

This danger is worst in Saxony, the strongest East German state, ruled since unification by a conservative CDU. The AfD has pushed into first place with 27 %, narrowly beating the CDU by a tenth of a percentage point, their first such victory in any state (the Left got 16.1, the SPD only 10.5 % in Saxony). The picture was all too similar in much of down-at-the-heels, discriminated East Germany and also in the once Social Democratic stronghold, the Rhineland-Ruhr region of West Germany, where many working class and even more jobless looked for enemies of the status quo – and chose the AfD. Men everywhere more than women.

It is difficult to ignore the history books. In 1928 the Nazis got only 2.6 %. In 1930, this grew to 18.3 %. By 1932 – to a great degree because of the Depression – they had become strongest party with well over 30%. The world knows what happened in the year that followed. Events can move fast.

The Nazis built on dissatisfaction, anger and anti-Semitism, directing people’s anger against Jews instead of the really guilty Krupps or Deutsche Bank millionaires. All too similarly, the AfD is now directing people’s anger, this time only rarely against Jews but rather against Muslims, “Islamists”, and immigrants. They have been fixated upon these “other people” who are allegedly pampered at the expense of “good German” working people, and they blame Angela Merkel and her coalition partners, the Social democrats – even though both have been hastily retreating on this question and moving toward ever more restrictions and deportations. But never quickly enough for the AfD, who use the same tactics as in past years, thus far with all too similar success. Over a million CDU voters and nearly half a million SPD voters switched allegiance on Sunday by voting for the AfD.

There are many parallels elsewhere in Europe, but also on almost every continent. The chosen culprits In the USA are traditionally African-Americans, but then Latinos and now – as in Europe – Muslims, “Islamists”, immigrants. Attempts to counter such tactics with counter-campaigns of alarm and hatred of Russians, North Koreans or Iranians only make the matter worse – and far more dangerous, when countries with giant military might and atomic weapons are concerned. But the similarities are frightening! And in Europe Germany, in all but atomic weapons, is the strongest country.

Were there no other, better alternatives than the AfD for opponents of “staying the course”? The Free Democrats, a polite bunch with ties almost exclusively to big business, were able to achieve a strong come-back from threatened collapse, with a satisfying 10.7 percent, but not because of their meaningless slogans and clever, unprincipled leader, but because they had not been a party to the governing establishment.

Neither were the Greens and DIE LINKE (the Left). Unlike the two main parties, they both improved their votes over those of 2013 – but by only 0.5 % for the Greens and 0.6 % for the Left, better than a loss, but both great disappointments. The Greens, with their increasingly prosperous, intellectual and professional trend, offered no great break with the Establishment.

On the national level dramatic developments may well be in the offing.

The Left, despite unceasingly bad media treatment, should have had a big advantage. It opposed the unpopular national coalition and took fighting stands on many issues: withdrawal of German troops from conflicts, no weapons to conflict areas (or anywhere), higher minimum wages, earlier and humane pensions, genuine taxation of the millionaires and billionaires who rip off Germans and the world.

It fought some good fights and, doing so, pushed other parties toward some improvements, out of fear of Left gains. But it also joined coalition governments in two East German states and Berlin (even heading one of them, in Thuringia). It tried hard, if vainly, to join in two others. In all such cases it tamed its demands, avoided rocking the boat, at least too much, for that might hinder hopes for respectability and a step up from the “disobedient” corner usually assigned to it. It found too seldom a path away from verbal battles and into the street, loudly and aggressively supporting strikers and people threatened with big layoffs; or evictions by wealthy gentrifiers. In other words, engaging in a genuine challenge to the whole ailing status quo, even breaking rules now and again. Not with wild revolutionary slogans or shattered windows and burnt-out dumpsters but with growing popular resistance while offering credible perspectives for the future, near and far. Where this was lacking, especially in eastern Germany, angry or worried people viewed it, too, as part of the Establishment and defender of the status quo. Sometimes, on local, even state levels, this glove fit all too well. Its almost total lack of working-class candidates played a part. Such an action program would seem the only genuine answer to menacing racists and fascists. To its credit, it opposed hatred of immigrants even though this cost it many one-time protest voters; 400,000 switched from the Left to the AfD.

One consolation; in Berlin, where it belongs to the local coalition government, the Left did well, especially in East Berlin, re-electing four candidates directly and coming closer than ever in two other boroughs, while militant Left groups in West Berlin gained more than in older East Berlin strongholds.

On the national level dramatic developments may well be in the offing. Since the SPD refuses to renew its unhappy coalition with Merkel’s double party, she will be forced, to gain a majority of seats in the Bundestag, to join with both the big business FDP and the torn, vacillating Greens. Both dislike each other heartily, while many grass-roots Greens oppose a deal with either Merkel or the equally rightwing FDP. Can those three join together and form a so-called “Jamaica coalition”- based on the colors of that country’s flag, black (CDU-CSU), yellow (FDP) and Green? If not, what then? Since no-one will join with the far-right AfD – not yet, anyway – no solution is visible, or perhaps possible.

The major question, above all, is all too clear; will it be possible to push back the menace of a party replete with echoes of a horrifying past and full of its admirers, who ever more openly want to reincarnate it, and are ready to employ any and every method to achieve their nightmare dreams. And can, as part of the defeat of this menace, such looming dangers to world peace be repelled?

*A possibly interesting side note:

The Left improved its percentage standing in every single West German state, by between 1.4 and 3.4 points, and achieved the 5% mark in every one, often for the first time.

The Left lost in percentage points in every single East German state (by between 2.9 and 6.1 %), especially in the two states where it is the coalition and the one where it had hoped and tried to be.

In Berlin the Left lost 1.0 points in East Berlin (from 29.5 to 28.5), but gained in West Berlin (from 10.8 up to 14.1%) which meant a general gain of 1.3 % (from 18.5 to 19.8%).

A Portrait to Flatter

By Lewis Bush

This piece ran originally in Witness, which is published by the World Press Photo Foundation, and receives support from the Dutch Postcode Lottery and is sponsored worldwide by Canon.

A little over a year ago, the United Kingdom voted to leave the European Union. For some this was a cause for jubilation, the successful end point of years of campaigning. For others it was a disaster, the triumph of a dark, xenophobic streak in British politics. Whichever it was, the vote was also an undeniable reminder of how fractured the United Kingdom has become, with analysis of the results revealing stark demographic divisions in who voted to leave, and who opted to remain. Shortly afterwards, I was waiting at London’s St. Pancras Station to board a Eurostar to France and pondering how the referendum result was likely to affect even this simple act of travel. As I waited, my eye was drawn to the rows of digital displays hanging throughout the departure lounge. Normally displaying advertisements and train departure times, instead these boards were illuminated with a series of photographic portraits.

This was part of Portrait of Britain, a collaboration between the British Journal of Photography and the digital billboard operator JCDeaux, who came together to display 100 portraits of contemporary Britons on digital signage across the country. The subjects of these portraits last year ranged from representing the well-known to the anonymous, with the likes of Don McCullin and Nadiya Hussain alongside ordinary Britons. Watching them change from one to another, I felt a sense of discomfort with the image of Britain that was emerging from the screens, one which I found difficult to explain. One year later, as a new iteration of Portrait of Britain launches and the Brexit negotiations continue in earnest, that feeling returns strongly enough for me to now attempt to dissect it.

For even a casual student of photography, it is hard to miss the reference Portrait of Britain makes in both title and form to one of the seminal works of documentary photography, August Sander’s People of the 20th Century, published in 1929 as the book Face of Our Time. A commercial studio photographer by trade, in 1911 Sander began this multi-decade project to document the people of inter-war Germany through portraits grouped into a series of thematic portfolios. In the process, he produced a work of social documentary which combined an aesthetic beauty with a remarkable scale. Sander recorded a deep cross-section of German society, from the obviously noteworthy figures of politicians and industrialists, to people at the bottom of the hierarchy, including wounded war veterans, circus performers, artisans, and peasants.

While sometimes seen today as almost naïvely humanist, Sander’s undertaking was not seen in such a light at the time, with the ascendant Nazi regime regarding this expansive image of Germany as dangerously in conflict with its own. The Nazi vision for Germany had little space for the existence, let alone the representation, of many of the ‘types’ that Sander felt it important to document. Consequently, his book was banned in 1934 and many of the negatives were destroyed. Sander spent the next decade undertaking less contentious work, while also compiling a final, secret portfolio titled The Persecuted. Perhaps the most poignant, but least well-known, section of Sander’s project, this addendum includes a photograph covertly taken of Sander’s own son Erich in his cell at Siegburg prison, where he had been interned and would later die for his involvement with left-wing political groups.

Sander also continued to take commercial portrait photographs in his studio, including many commissioned by members of the Nazi hierarchy. One of these taken in 1937 shows a Captain of the SS, standing in front of the Cathedral of Cologne, the city where Sander’s studio was located. Amongst Sander’s oeuvre it is again an image far less seldom displayed than his photographs of pastry chefs or amateur boxers, perhaps because it is one of the most challenging and confrontational of the images he produced. The captain is a perfect representation of Nazism, presenting himself unashamedly before the camera, safe in the knowledge that he and his kind are in the ascendancy. The brazen gaze of this man, and the knowledge of Sander’s own persecution, often make me wonder what inner resources it must have demanded of the photographer in order to take this picture.

Portrait of Britain is clearly making no claim to such comprehensive documentation as Sander, although given that it is drawing on the works of multiple photographers one might think that depicting a truly broad representation of Britain would be a more achievable goal than for one acting alone as Sander did. And yet in contrast to the breadth of Sander’s project, the people who have made it into Portrait of Britain constitute a noticeably narrow cross-section. They are predominantly young, beautiful, multi-cultural, aspirational. This is not in itself problematic, the people depicted are certainly part of the complex patchwork that makes up Britain today. But if these are the people who, to borrow a phrase from JCDeaux’s copywriters, are worthy of being ‘given noble status’ by their elevation to electronic advertising billboards, it seems we should also ask who are those implied to be unworthy of such ennoblement.

One of the privileges of teaching documentary photography is experiencing the world somewhat vicariously through one’s students, learning from them as they return with stories about people and places I have not myself encountered. My students frequently remind me how little I know of my own country, and through them I also become aware of the gaps we have as a nation in our collective, imagined image of ourselves. To speak only of a few of my fellow countrymen who my students have helped me become better acquainted with, I must ask where in Portrait of Britain are the disabled, quietly starving in freezing homes because of cuts to social security? Where are the refugees living on tenterhooks at the expectation of imminent relocation or deportation? Where are the fishermen rendered unemployed by globalisation, marking time by drinking themselves into oblivion? Where are the racists and xenophobes, gathering to unite in their shared hate?

The answer is that these people, like the English Defence League member depicted in Ed Thompson’s photograph above, are largely absent. Some of the selected photographs might touch indirectly on such issues (Claudia Leisinger’s photographs of a Billingsgate fish porter for example, speaks to me quietly of the onward march of globalisation and its impact on ordinary people), but presented on the Portrait of Britain website or on digital displays in shopping arcades and railway stations, they are shorn of such vital context. The reason ultimately being that while it might be clad in the guise of social documentary photography, Portrait of Britain is a commercial exercise for the organisers, and commerce fears nothing quite like a controversial opinion clearly stated. Yet whether we like to acknowledge it or not, these people are as much the face of Britain in 2017 as Stephen Hawking and Dizzee Rascal.

What Portrait of Britain really represents is a problem across the arts at large. In the wake of Brexit and the election of Donald Trump, with the right seemingly on the ascendancy across the western hemisphere, there has been much discussion of the ways that we have insulated ourselves from reality in echo chambers which resound with reassuring noises, and blanket us from the fact that the alarmist rhetoric of the right finds many receptive and attentive ears. Rather than engage with enormously complex problems like globalisation and immigration, to which there are few simple answers, it has often proven easier for the left to ignore or dismiss those who are disquieted by them. In the process, the arts and even the supposedly mass, democratic medium of photography all too often become echo chambers of their own, perpetuating a comforting but ultimately misleading image of the world, which under the appropriated banner of documentary masquerades as an objective truth.

Photography has a potentially important role to play in helping us to rediscover the sometimes uncomfortable contours of our country, and perhaps also helping to heal some of the scars of the last few years. But such incomplete images of Britain cannot do that, and the tendency to deny and overlook sections of society has played no small part in the fractures and fissures that wrack our country and drive people to the empty promises of the political extremes. August Sander, in the introduction to a post-war reprint of Face of Our Time, wrote that ‘I have been down good paths and bad paths, and I have acknowledged my mistakes…so allow me to be honest and tell the truth about our age and its people.’ Today it seems we could badly do with some of the same honesty.

Detroit, the movie

By Mike Miller

Talking about Detroit the movie, Kathryn Bigelow’s devastating and deeply moving film on the city’s violent summer of 1967, begins with the difficulty in naming the story it tells about the city. In an interview about the film, Bigelow calls it an “uprising”. Among many of my friends and acquaintances it is politically incorrect to call it a “riot”; their preferred terms are “revolt”, “rebellion” “insurrection” or “uprising”. Neither “riot” nor the latter four options work for me, so I’ve invented a few alternatives: “riovolt”, “reviolution” or “uprioting” – take your pick. If Detroit was an uprising/revolt/insurrection/rebellion, then we need different terms for what Nat Turner, Denmark Vesey, Jemmy, Gabriel and hundreds of other slave leaders did. At a minimum, there is a dimension of planning and targeting in the latter that is absent in the former.

Detroit begins at a party, at an unlicensed after-hours club, celebrating the return of two African-American Vietnam war veterans. In the wee small hours of the morning, the cops raid the place and begin arresting the party-goers. Probably most of the people had more than a few drinks by that time. In any case, initially they were in good humor, trying to tell the cops they weren’t doing anything wrong. Things get out of hand. The cops rough-up some of the arrestees. A crowd gathers around the paddy wagons. A bottle is thrown at the cops. Glass is broken. The cops leave, looking for reinforcement, but the crowd remains. Pent up hostility toward the 95% white and widely known-to-be racist police force is expressed. Windows are broken, looting begins, alarms go off, fires break out, sirens are heard in the distance.

From there things quickly escalate. To reveal them will take nothing from the drama of the movie, so, briefly, here are some: Congressman John Conyers appears and addresses a crowd, acknowledging the legitimacy of their anger but urging them to cease their activities. Windows continue to be broken. In one case, a man runs from a store with stolen property; he is shot in the back. He manages to get away, and crawl under a car. There, blood running from his body, he dies. At police headquarters, a supervising cop calls what happened “murder”. That is the only time we see a specific cop on the side of law enforcement. (While the National Guard, State troopers, U.S. Army paratroopers and Detroit Police are backgrounded as bringing the uprioting under control, the main character cops are engaged in lawlessness.)

Another harrowing scene: a young black girl opens the window curtains in her living room. Scared cops see a gun rather than rustling curtains, and open fire. She is killed.

There is an interlude: The Dramatics, an up-and-coming male gospel turned R & B quartet, is about to perform in a Detroit auditorium when the cops arrive and shut the concert down. The four young men make their way to The Algiers Motel where they join with other young blacks and two young white women. The why of the women’s presence isn’t totally clear: the cops later call them prostitutes (they weren’t); they describe themselves as visiting from western Michigan. One of them says her father is a judge. But how they ended up at a mostly-black motel should be made clearer. One of them helped in the making of the film, and says they were following “a band, an R & B group” they met in Columbus.

An African-American security officer, Melvin Dismukes, is an enigmatic figure in the film. What makes him tick is never made clear. It should have been. On the one hand, he at times appears to go along with the cops at their worst. At other times he’s a careful calculator of the possible in an impossible situation and does what he can to diminish the evil, including saving the life of one young black man. He is so disgusted by the not-guilty verdict in the criminal case against the cops that followed the events at the motel that he vomits.

But, according to the post-incident Citizens’ Action Committee, formed by a group of Detroit black leaders, Dismukes played a role in the murders. In an interview 25 years later, he said, “I had nothing to do with what they [the cops] had done. And to this day I still say the only reason my name was linked with them was to get them off. It would put less pressure on them if they could tie a black person in with it. Now you can’t make it a racial issue.”

“The Algiers Motel Incident,” as the events there came to be known, is a horror story of police intimidation, brutality and murder. I won’t go into the details here. Suffice to say that the Dramatics make their way there from their cancelled concert. Initially, the motel is somewhat removed from the unfolding riovolution. That soon changes. A toy or starter gun (no bullets) is used by one of the men there in a pretended shooting of another man in the room. He falls to the floor in a pretend-to-be-wounded moment. When everyone realizes what’s taken place they laugh. Edgy cops across the street don’t. They assume they’re being shot at. The Algiers Motel Incident follows. It is a grueling, unrelenting, example of law enforcement at its worst. It also captures the power of the worst racist in the group of law enforcement people (state and local police, national guard and a security guard) who invade The Algiers to impose his will on those (except for one) who might otherwise have been unlikely to do what they did to totally innocent people. Three young black men end up murdered by cops.

Bigelow puts human faces on the huge scale of the events that are here summed up statistically: 43 civilians killed, 33 of them African-American; more than 1,000 people injured; over 7,000 arrested; thousands of buildings destroyed, many never rebuilt; millions of dollars in damage.

“It was as if God was saying, ‘I’m going to give you this test, Ike, and let you see how bad people can be, but I’m going to let you live through that,’ ” said McKinnon, who returned to work the next day. “I was never so afraid as those days in July during the riots.”

The mid-to-late 1960s was a season of riovolts. The assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1968 prompted dozens of them across the country. I was working in the Kansas City, MO African-American community when one erupted there—clearly provoked by local cops who tear-gassed non-violent marchers. They are scary!

Predictably, none of the cops is convicted in the criminal trial that follows. A civil court case produces compensation for two of the families of murdered young men.

As might be imagined, Detroit provoked strong reactions. Many were positive, and appeared in mainstream media. One white critic is incapable of seeing that an explosion like Detroit’s could happen today. Writing in The New Yorker, Richard Brody is offended that the film “suggest[s] that, in the intervening half-century since the events depicted in the film took place, little has changed.” Sad to say, there are still cities where police brutality is a continuing problem, and where similar riovolts might well take place. Bigelow sums it up: “These events seem to recur — this is a situation that was 50 years ago, yet it feels very much like it’s today.”

Another, Angeleica Jade Bastien, is angered by what she saw and deserves to be quoted at some length:

“Detroit” is ultimately a confused film that has an ugliness reflected in its visual craft and narrative. Bigelow is adept at making the sharp crack of an officer’s gun against a black man’s face feel impactful but doesn’t understand the meaning of the emotional scars left behind or how they echo through American history. “Detroit” is a hollow spectacle, displaying rank racism and countless deaths that has nothing to say about race, the justice system, police brutality, or the city that gives it its title.”

Here are some facts about the “rioters” from a study done shortly after the events by the Detroit Urban League and the Detroit Free Press: “Rioters are different,” begins a survey-based article, “What Sets Him Apart?” Most striking, “Fifty-nine percent of the rioters were between 15 and 24 years old,” and, “60% were male.” They were twice as likely to have experienced long-term unemployment, though there “was no pattern to directly link rioting and low income.” The report finds deep alienation: “rioters profess to shun the American dream.” “Their attitudes “represent a bitter reservoir of resentment…” but there are contradictions: about three-quarters of the respondents “accept the traditional American belief that people with ability and drive get ahead and that people who are unsuccessful in the conventional sense should blame their own mistakes.” The grievances “that were associated most strongly with rioting were of a notably short term nature: Gripes against the local businessmen, mistreatment by police, lack of jobs, dirty neighborhoods, lack of recreation facilities.”

The survey sums up its findings: “These, then, are the rioters: Young people, raised in the North, with little concern for their fellowmen and a frustration in meeting near-term goals—people susceptible to the black nationalist philosophy that the law and order of a white-built society is not worth preserving.”

Editorially, the Free Press concluded, “…if the attitudes of alienated young Negroes are to change, the attitudes of the rest of society must change.” (The entire document is worth careful reading, and can be found here).

These findings fill in blanks missing from the film. It does not provide context for what it so dramatically portrays. Perhaps it is too much to ask from a gripping moment-by-moment account of a brutal series of events. But the viewer who is not already convinced is unlikely to fully appreciate why these riovolutions take place. They are more likely to be viewed as riots, an insufficient concept to understand the events.

An Eyewitness Story:

Ike McKinnon, a Detroit policeman at the time, reminisced about those 1967 events in a Detroit News account of an incident he experienced. He was in full uniform, completing a 16-hour shift, when he was stopped by a pair of white cops. This is what ensued:

“I said ‘police officer. I’m a police officer,’ “They had their guns out. I remember one officer so vividly. He was probably in his late 40s. He had brush-cut, silver hair. He said ‘today, you gonna die (racial slur).’”

It was as if things were unfolding in slow motion, McKinnon said, as he watched his fellow officer pull the trigger. He dove back into his car.

“With my right hand, I pushed the accelerator, my left hand I steered my Mustang, and they were shooting at me as I drove off,” he said.

McKinnon escaped uninjured, drove home and reported the shooting to a sergeant. It was never investigated.

That was McKinnon’s first brush with death during those tense July days, but he said it wasn’t his last.

“It was as if God was saying, ‘I’m going to give you this test, Ike, and let you see how bad people can be, but I’m going to let you live through that,’ ” said McKinnon, who returned to work the next day. “I was never so afraid as those days in July during the riots.”

McKinnon would later become Detroit’s chief of police in the 1990s as well as more recently deputy mayor under Mayor Mike Duggan.

Letter from Florence #1: Saggio da San Frediano

By Peter Olney

September 7, 2017

From La Repubblica: It is logistically impossible to host the Nazi Fascists in Roma All the dumpsters are are completely full

My wife Christina and I have settled in to our life here in the San Frediano neighborhood of Florence, Italy. San Frediano is Oltrarno or on the other side of the river from the famous Duomo and the major tourist center of the city. However San Frediano, once a working class neighborhood of artisans and craftsman, was just voted the “coolest” section of Florence by Lonely Planet. The proletarian quarter that gave rise to the post World War II novel of Vasco Pratolini, “The Girls of San Frediano” is now an ascendant super hip zone. This transformation is not unlike the change that has overwhelmed the Mission District in our home city of San Francisco.

Other parallels here in Italia are more disconcerting. Forza Nuova, in shades of Charlottesville, has announced a Marcia dei Patrioti” (March of Patriots) to be held on the 28th of October. That is 95 years from the day in 1922 that 25,000 black shirts from the Partito Nazionale Fascista marched on Rome, forcibly taking power for Mussolini, beginning the twenty-year reign of Il Duce.

Forza Nuova has already been designated twice by the Supreme Court as “nazi-fascist” but continues to gather strength even winning a seat in the European Parliament. The march is being promoted on the internet and financed using PayPal. Fascism is formally outlawed in Italy by the Scelba Law of 1952 so the staging of this march/rally may be in doubt. For example Prato, a working class city in Tuscany, and not far from Florence, just passed a new regulation forbidding demonstrations “that violate national laws against propaganda that instigates racial hatred and the reconstruction of the fascist party”. Fascist demonstrations per se then are violations of the postwar constitution. But groups like Forza Nuova skate close to the edge by disavowing explicit references to a fascist party but nevertheless promoting the values of racial hatred and anti immigrant venom.

Every day the newspapers, particularly those owned by ex Premier Silvio Berlusconi dramatize alleged attacks by immigrants, usually Africans, on Italians, and particularly assaults on Italian women. One recent incident involved the death of a 4 year old Italian girl of malaria because off supposed contamination of a hospital treating refugees from Burkina Faso. Tragedies become opportunities for the far right to denounce the waves of immigrants “assaulting us on the streets and even now in the hospitals.” Here in Tuscany this summer, Samuel L. Jackson and Magic Johnson were vacationing at the beach at Forte dei Marmi. They were captured on film lounging on a bench with bags of Gucci and Louis Vuitton. Social media exploded with angry denunciations of “two African migrants taking advantage of the daily 35 Euro stipend we give them” A new twist on the old Ronald Reagan “welfare queen” slander.

Very sad News arrived in Italy on Tuesday of the Trump decision to eliminate the “dreamers” or DACA program. DACA gives children born in foreign lands but brought to the United States at a young age the right to remain and eventually apply for US citizenship. The Italian Chamber of Deputies passed an immigration reform law in 2015 that would grant “ius soli temperato” to thousands of immigrant children. “Ius soli”, Latin for a right linked to territory or soil, is the existing constitutional right of a child born in the United States to become a citizen. This right does not exist in any country in the European Union. In Italy the latest immigration law of 1992 gave automatic citizenship by “ius sanguinis” or by blood meaning that if one of two parents is Italia then the child is a citizen. The new law of 2015 that must be passed by the Senate would give citizenship to a child born in Italy of at least one parent who has been living in Italy legally for at least five years. However if the legal parent is not from the European Union then there are further qualifications of income, lodging and language.

The new law if passed would impact about 634,592 young people according to estimates from the Leone Moressa Foundation. This is a not insignificant number in a country of 61 million. Passage is not assured however. The law is supported by the Partito Democratico, the largest party in Italy, but the aforementioned neofascist Forza Nuova, and the right wing Lega Nord, both oppose the law in very visible fashion – on June 8th the Lega Nord staged a very raucous demonstration inside the Senate chambers against the “Ius soli temperato”.

More to come as October 28th approaches. Will the march be outlawed? Will the left mount a counter protest? Saggio da San Frediano will continue on The Stansbury Forum

Ciao