Saggio da San Frediano #10 – The Fields of Piemonte – Bitter Rice – Bitter Laughter

By Peter Olney

Our friends LoLo and Viviana invited us to spend a weekend in Vercelli in early December. LoLo is “Una Vercellese” and she and Viviana make the town their home in between their epic travel adventures. Vercelli is a town of about 70,000 halfway between Milano and Torino in Piemonte. We thought Vercelli would just be a sleeping spot for day trips into Torino. Al contrario…… I couldn’t resist attending a Confederazione Generale Italiana dei Lavoratori(CGIL) rally against pension cuts on Saturday in the snow and ice of Piazza San Carlo in Torino. Christina visited the Museo Egizio whose Egyptian collection is only rivaled by the British Museum. We also visited the Lingotto production facility that housed the early production of the FIAT (1923-1982), but is now an upscale shopping mall with the Agnelli family museum on the top floor. The only sign of autos is the “Test Track” on the roof of the old factory and the FIAT logo (Fabbrica Italiana Automobilistica a Torino) stamped in concrete over the old administration building. (If you are in Southern California you can see a similar industrial plant to shopping mall conversion of the old Uniroyal Tire Plant in Commerce)

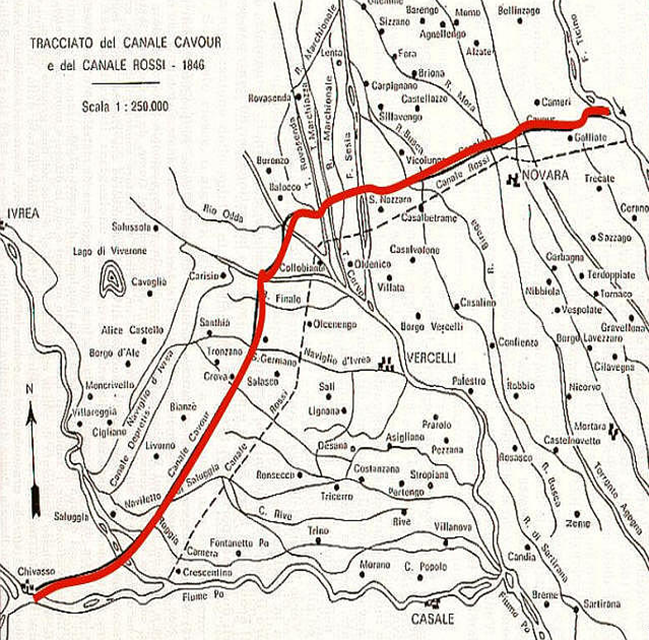

Vercelli turned out to be the highlight of our trip to Piemonte as we discovered the rice industry and the history of the female rice workers, Le Mondine (from the word “mondare” meaning to clean and husk). This rice growing region centered in the towns of Vercelli, Novara and Pavia make Italy Europe’s number one rice producer. As is often the case you have to leave your own “paese” to learn more about it. While working at the International Longshore and Warehosue Union, I on occasion assisted the workers at the giant Farmer’s Rice Mill in Sacramento, California with their negotiations and internal organizing. There were 400 of them working in the Port of Sacramento, processing rice for export on ships that would come up the Delta to be loaded and then deliver the rice to destinations in the Far East, particularly Japan where California rice was prized in the production of sushi. I knew that the rice came from north of Sacramento, cultivated in flat fields flooded with water, but I had no idea of the production process and certainly no idea about the workforce.

Education about the Italian workforce began with retired CGIL and Labor Council leader Giorgio Comella on Friday, December 1 in Vercelli. We met in the Cavour Bar in the main Piazza of the city. He explained that Vercelli was the center of a history-making struggle for the 8-hour day in 1906. He asserted that 250,000 workers, mainly women, were employed in the rice fields of the Pianura, and that many of them participated in strikes and protests that won the 8-hour standard. I asked how many workers total were employed in the fields now, and he responded about 4,000. Technology has had an impact.

This massive scale of female employment, in dramatic environmental conditions requiring young women in short shorts standing knee deep in the water, gave rise to lots of songs and movies. In fact the women were accustomed to sing as they worked and some speculate that the famous partisan anthem, “Bella Ciao” (lyrics here) came out of the rice fields. Nevertheless it is beyond speculation that the song , “Se otto ore son troppo poche”, did come out of the fields and it is a mocking declaration to the rice field owners, “If eight hours are just too little!” There are two famous movies made about the “Mondine” or “Le Risaia”. In 1949 Giussepe De Santis made “Riso Amaro” (a double entendre translated as bitter rice or bitter laugh). This movie starred Vittorio Gassman and Silvana Mangano. Then in 1956 Carlo Pontti made La Risaia starring Elsa Martinelli.

Learning about the workforce needs to be coupled with an understanding of the production process, or knowledge of working class life is limited. And of course changes in the production process have dramatically affected the workforce. On Sunday, December 3 we had the great fortune to dine at Oryzariso part of the Tenuta Castello estate that has a B&B, restaurant and production facility all in Desana north of Vercelli. We were hosted by Eduardo Vercellone whose family has farmed rice for generations. Any good day in Italy always begins with a fabulous meal, and this Sunday was no exception. Risotto was originally a “Primo piatto” eaten by peasants in the rice growing regions where the raw material was rice, not the grain which is used in the production of pasta in more southern regions. Eduardo’s restaurant has made the risotto into a gourmet delite, serving every imaginable combination of risotto with various nuts and vegetables and fruits. My favorite was Risotto with cheese, pear and walnut! Christina couldn’t resist ordering risotto mixed with brown beans. Ole!!!

After lunch we rode to Eduardo’s milling facility and he explained the whole process. Planting takes place at the end of April through the beginning of June. Irrigation has an important dual purpose. After planting, the fields are flooded for irrigation, but also because the water retains the warmth of the sunshine so that the rice plants remain warm during what can be cold nights in the plains. Then in the fall the fields are drained and the harvest is done with giant combines. He explained that the Mondine used to participate in the harvest (now mechanized) where they often encountered snakes and rats who slithered through their legs as they moved forward. And prior to the harvest Le Risaia had to manually trim off herbal infestations from the rice plant. That work has been done by herbicides now although the organic farming movement is pushing the elimination of herbicides in favor of maybe more “mondine”!

Eduardo also showed us his highly mechanized milling equipment (all made in Italia) that takes the newly harvested rice and husks it and dries it for market. While standing outside his mill I spotted the name “Singh” stenciled on the side of a giant harvester. Then an employee of the mill emerged to converse with Eduardo. He was a Sikh. Eduardo explained that there were many Sikhs involved in rice production as farmers, owners and workers. What a small world as Singh is a very common name in the Sacramento Valley and Sikh peoples have been involved in agricultural production in California since the early years of the 20th century. Eduardo promised to ask later if the worker has relatives in California, and he promised to visit our rice fields in the California delta soon.

I am inspired now to return to California and make a field trip to the 4 principal rice growing counties north of Sacramento: Colusa, Sutter, Glenn and Butte. Maybe if I had visited those fields 100 years ago I would have found strong robust women, in short pants singing “Bella Ciao’!?? Unlikely today as the California industry which is second only to Arkansas in rice production is highly mechanized like its counterpart in Italia.

“How Can Political Shift to the Right Be Stopped?”

By Immanuel Wallerstein

This is the question people left of center have been asking for some time now. In different ways, it is being posed in Latin America, in much of Europe, in Arab and Islamic countries, in southern Africa, and in northeast Asia. The question is all the more dramatic because, in so many of these countries, this follows a period when there were significant shifts leftward.

The problem for the left is priorities. We live in a world in which the geopolitical power of the United States is in constant decline. And we live in a world in which the world-economy is seriously reducing state and personal incomes, so that the living standard of most of the world’s population is falling. These are the constraints of any political activity by the left, constraints the left can do little to affect.

Increasingly, there are movements emerging that make their appeal on a denunciation of mainstream centrist political parties. These movements call for radically new transformative policies. But there are two kinds of such movements, what one might call a right version and a left version. The right version can be found in Trump’s U.S. presidential campaign, Rodrigo Duterte’s anti-drug campaign in the Philippines, the Law and Justice Party in Poland, and many others. For the left, priority number one is to keep such movements from seizing state power. These movements are basically xenophobic and exclusionist and will use their control of the state to crush movements of the left.

On the other hand, there exist movements of the left that have also been organizing on the basis of radically new transformative policies. They include Bernie Sanders’ attempt to obtain the Democratic nomination for U.S. president, Jeremy Corbyn’s attempt to return the British Labor Party to its historic support of socialism, Syriza in Greece and Podemos in Spain, and many others. Of course, when such movements come near to obtaining state power, the world right (mainstream or radically anti-Establishment) unites to eliminate them or to force them to modify their positions in major ways. This is what happened to Syriza.

So this second priority has its in-built limitations. They are forced to become another version of a center-left social-democratic party. This does serve one function: It limits the short-run damage to the poorer strata, thereby minimizing the damage. But it does not aid in transformation.

The middle-run objective of establishing a new world-system that is relatively democratic and relatively egalitarian requires political action of a different kind. It requires organizing everywhere at the bottom level of politics and building alliances up from there, rather than down from state power. This has been the secret of the recent strength of rightwing anti-Establishment movements.

What will make it possible for the left to gain the upper hand in the struggle over the next 20-40 years to establish a successor system to our existing capitalist system, now in definitive decline, is an ability to combine the short-run politics of alliances to minimize the harm that tight budgets do to the poorer strata, fierce opposition to the control of state power by rightwing anti-Establishment movements, and continuous organization by the world left at the bottom level of politics. This is very difficult and requires constant clarity of analysis, firm moral options for the kind of possible other world we want, and wise tactical political decisions.

This piece was first printed in Commentary No. 434, October 1, 2016. To read more by Immanuel Wallerstein visit Binghamton University Commentaries

Capture the Democratic Party? More Likely Be Captured! Is there An Alternative?

By Mike Miller

A recent analysis and call to action from Bernie Sanders sent to the “Our Revolution” e-mail list is illustrative of the difficulties in “taking over” the Democratic Party. He says:

—“We need a Democratic Party which becomes the political home of the working people and young people of this country, black and white, Latino and Asian and Native American … all Americans.”

—The Democratic National Committee’s Unity Reform Commission must: (1) make the Party more democratic, and the presidential primary more fair by reducing the number of super-delegates; (2) ending “closed primary systems” in which voters have to declare party preference far in advance of the primary election, and; (3) supplement caucuses with some kind of additional procedure that allows those who can’t attend an opportunity to vote.

—And he concludes, “we must institute long-needed reforms in the Democratic Party.

He’s right: if the strategy of progressives is to reform the Democratic Party, they must attend to instituting “long-needed reforms.” Doing that is a lengthy, time-consuming process that requires the commitment of time, talent and money, and attention to details. That’s why he is both right and wrong.

The second difficulty in taking over the party is that having control has little to do with the process of running a candidate as a Democrat—as Sanders’ campaign itself demonstrates. There is nothing in the internal structure of the Party that prevents Joe Blow or Susie Que from declaring him/herself a Democrat, assembling the money, campaign professionals and feet-on-the-street volunteers for a campaign, and then running in a Democratic Party primary.

The idea that Party rules can keep money out of politics flies in the face of both past experience and, more recently, a series of rulings by the U.S Supreme Court that treat the expenditure of vast amounts of money as a matter of free speech.

We need to take over the Party, Sanders says, because:

— “People are hurting in this country…Our job is to create an economy and government that works for all of us, not just the 1%…”, and;

— “The Democratic Party [must be] prepared to take on the ideology of the…billionaire class…who are undermining American democracy and moving this country into an oligarchic form of society.”

Without taking over the Party, he warns that we cannot address the fundamental issues of social and economic justice or climate change.

Other Possibilities

The industrial union movement of the 1930s (Congress of Industrial Organizations —CIO) was organized independently of any political party. The civil rights movement of the mid 1950s-mid-1960s was organized outside the Democratic Party. The same is true of the gay/lesbian, women’s, immigrant rights, disability rights, senior citizen and other efforts that extended rights, power and material benefits to previously marginalized, exploited and discriminated against groups.

For the most part, once having built their power base outside the framework of the political parties, these movements and organizations choose to enter electoral politics and “join” the Democratic Party. Instead of capturing it, it captured them. The lessons to be learned from the cooptation of independent movements and organizations are abundant. If you’re not already convinced of that, nothing I can say will convince you.

In my lifetime, I watched up close and personal how that happened in Mississippi—where in 1963 I was a field secretary for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and continued full-time in SNCC until the end of 1966. From 1961 – 1964, SNCC built from the bottom-up the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP). At the 1964 Democratic National convention, MFDP challenged the seating of the Mississippi racist regular party. It made national news, but lost. At the opening of Congress, MFDP challenged the seating in the House of Representatives of the elected Mississippians. More than 150 members of the House voted for this challenge, but it, too, lost. The MFDP campaigns probably had as much to do with the passage of the Voting Rights Act as did the Selma-Montgomery March.

The Democratic Party concluded that MFDP was too independent, and proceeded to undermine and weaken it by means of a two-part strategy. First, an alternative was created—the Mississippi Democratic Conference (MDC). By the time of the 1968 national convention, MDC controlled three quarters of the delegates; MFDP had the remaining one quarter. Second, the expenditure of poverty program funds had the effect (and intent) of coopting the SNCC-initiated and -led civil rights movement there. The movement was enmeshed in the MFDP. Except in a few counties, it had not built a base sufficiently autonomous from electoral politics to withstand the two-part strategy of marginalization and cooperation.

Just To Be Clear…

This doesn’t mean that the Democratic Party is not an arena for struggle. In many cases, though not all (for example, where a local party is deeply enmeshed in corruption, the Republican Party, a third party or an independent effort might be a better vehicle), I think it is the most likely one. But making it an arena for struggle is different from becoming enmeshed in its internal workings. As Sanders himself demonstrated in his Democratic primary race for the presidential nomination, an apparatus can be built outside the framework of the party. Just as his independent campaign mobilization apparatus used the party as a vehicle, so is it possible for independent ongoing organization to use it to further its agenda, which might include running or supporting candidates.

But there are other ways of entering electoral politics that should be carefully considered as well.

“Fusion,” the strategy of the Working Families Party (WFP), is one. WFP is a third party that endorses Democrats, occasionally a Republican, and in some cases runs its own candidate. If you vote, for example, for a Democrat under the WFP ballot listing you at once play in the “lesser-of-two-evils” reality of American politics but, at the same time, let the Democratic Party know that you are a to-its-left independent, and strengthen a third party.

“Partisan non-partisanship”. In this case, an organization presents its political agenda to candidates, and asks them, “Where do you stand on the people’s issue(s)?” It then demands “yes” or “no” answers to questions that make clear where the candidate stands. Examples might be:

—Do you support Medicare-for-all? Yes or No

—Do you support $15.00 living wage? Yes or No

—Do you support Dodd-Frank? Yes or No

—Do you support a “path to citizenship” Yes or No

A more detailed definition of what “support” means can be part of the process of interviewing or otherwise judging the candidate. But this is crucial: the organization that asks these questions has to be trusted by voters; it has to have roots that go more deeply than social media, paid mass media or even enthusiastic but here-today, gone-tomorrow canvassers. Only a year-round organization that does more than electoral politics can dig those roots.

The organization then engages in a large-scale voter education, registration and get-out-the-vote (GOTV) drive in which voters learn where politicians stand on issues that mean the most to them. If it is respected, and the drive a serious one, vote totals will demonstrate that a politician cannot afford to ignore this organization’s political agenda and win. Efforts such as this were undertaken in past years with success in Chicago (the CAP organization) and New Orleans (by ACT).

Large public accountability sessions are another way of making candidates define themselves in terms that they otherwise might want to avoid. In front of several thousand people, candidates are asked “yes/no” questions on key issues. A candidate who refuses to come to the session is a “no”. These events often gain major media attention. Some years ago, San Antonio’s COPS illustrated the power of this approach. The organization sponsoring the event then engages in the same education/registration/GOTV campaign identified above.

Finally, you can build an officially non-partisan political organization that directly endorses candidates. The Richmond (CA) Progressive Alliance (RPA) did that. Over a careful building process that took roughly ten years, the organization developed sufficient trust among the electorate to take over the Richmond City Council in 2016. In congressional districts where the choice was a clear one, ACORN did that in a number of electoral campaigns across the country by registering and turning out low-to-moderate income citizens who typically don’t vote but who, when they do, overwhelmingly support Democrats.

These approaches can be taken in national, state and local races. The core idea is to retain your autonomy while playing politics in the framework of “lesser of two evils” because that is the realistic framework in which you have to play if you want your vote to count in winner-take-all elections, or even worse if you don’t want your vote to have the effect of electing the worse of the two evils. And note: don’t do any of these unless the numbers you can deliver are substantial and demonstrable. If otherwise, you simply advertise your weakness.

None of these strategies require that you put all your marbles in electoral politics. Quite the contrary, their success depends upon your organization having a life and vitality that is separate from electoral politics. The activities engaged in as part of that independent life make the organization’s name mean something to voters…and to members.

Just as running third party candidates in national elections is a mistake because it is a wasted vote and, possibly, a vote for the greater evil, so is it a mistake to make capture of the Democratic Party the strategy of people interested in bringing about fundamental/transformational/substantive change in American politics. Something has to be built external to the Democratic Party that has a life independent of electoral politics, for which engaging in elections is a tactic to be used along with other tactics.

A Moral and Cultural Struggle

I have elsewhere in Stansbury Forum discussed the character of mass based organizations that I think are the best vehicles to build power external to the Democratic Party. Their building blocks are religious congregations, union locals, and civic, interest and identity groups that are deeply rooted in values that challenge the present dominant culture.

These building blocks contrast sharply with the inevitable character of major political parties in a winner-take-all system. Ideological parties in a parliamentary system can be transformational in outlook and still win seats in the government. Trades take place in parliament. Major parties in the U.S. are transactional. They are forums within which interest groups make trades in order to create electoral and governing majorities.

The struggle in which we are now engaged in the United States is not simply one of political program or collective bargaining issues. It is a deeply cultural and moral one that requires a counter-culture to challenge the existing status quo.

Saggio da San Frediano # 9 – Sheila e La Frecciarossa

By Peter Olney

On September 24 we met our friend and Christina’s colleague from work, Sheila James at the Fiumicino airport in Rome. Sheila was joining us for a week “a Firenze”. What a great week it was as Sheila proved to be a “viaggiatore” not a “turista”. My Italian friends make this distinction between those who arrive and want to see all the guidebook sites and those who want to dig into Italian life. Sheila led us to places we were not aware of, perfected some Italian, met and befriended the local merchants and discovered a direct train from Florence to the airport in Rome. Sheila knows about mass transit. Having grown up in NYC it is in her DNA and is her preferred mode of transportation. She reads timetables and understands connections. In fact she is a “mass transit celebrity” having been the subject of an August 21 Business Day feature in the New York Times, written by Conor Dougherty and Andrew Burton and entitled “Up at 2:15, At Work by 7”.

This New York Times spread complete with multiple fotos detailed Sheila’s time consuming commute from Stockton, California to work in downtown San Francisco. To be at work by 7 AM Sheila catches her first train in Stockton at 4:12 AM (Altamont Corridor Express) to arrive at a bus in Pleasanton for a 4:58 AM pickup that puts her on a BART (Bay Area Rapid Transit) train leaving at 5:55 AM for Civic Center, San Francisco where she arrives at 6:50 AM, and walks to her office. This is a commute of 83 miles if by car and 62.8 miles as the crow flies. Sheila gets up in the morning at 2:15 AM so as to drink her coffee and ready herself peacefully for the commute. The article points out that many commuters are making this same trip or longer (5% commute 90 minutes or more) because of housing costs in the inner Bay Area where median home price in San Francisco is $1.2 million versus $260,100 in Stockton. Rents are similarly skewed. Sheila pays $1000 per month for a three-bedroom home in Stockton. In SF it would probably rent for $4000-$6000 per month!

What the article neglected to discuss, but what was painfully obvious to Sheila when she got to Italy, is the lack of a decent “rapid” transit system in California. When we took Sheila on the train from Rome to Florence on the Frecciarossa we arrived in one hour twenty minutes and traveled an average of 155 miles per hour. This is a driving distance of 174 miles. As our friends and family who travel the Northeast Corridor of the USA know the Amtrak Acela averages 63 miles per hour, making the Boston to NYC trip about a 3 and 1/2 hour ride.

Italy still has a public passenger rail system called Trenitalia owned by Le Ferrovie dello Stato. This system was founded in 1905 and consolidated Italian rail service that had historically been regionally based and reflected the city-states and regional “Ducati” that predated the unification of Italy in the 1860’s. Under fascism in the 20’s and 30’s there was a maniacal obsession with building a national train system and while workers paid the price in increased hours and reduced pay, it is true “Durante il facismo i treni arrivavano in orario”, the trains ran on time, and they continue to run on time. In 2006 with the liberalization of transportation services mandated by the European Union there was the formation of Italo, a private passenger company that provides only train service on the high-speed lines between major cities. Trenitalia provides all the regional services and competes with Italo on the high-speed lines. The workers of both services are represented by Italy’s three large labor federations. Train travel is not cheap but it is far more convenient than air in terms of waiting time and security hassles.

I decided it would be interesting to try to replicate Sheila’s commute in Italia and see what her travel time would be like using Italian trains. Stockton is a city of 300,000, 63 miles (101 Kilometers) as the crow flies from SF. I choose Bologna in the region of Emilia Romagna as a starting point for a commute to Firenze. Bologna is a city of 388,884 and is the seventh largest city in Italy. The distance from Bologna to Florence is 104 kilometers and is traveled crossing over the Apennine Mountains. If Sheila were to leave the train station in Central Bologna at 6:05 AM and travel to Firenze Santa Maria Novella she would arrive at 6:41 AM. With all due respect, Stockton is not Bologna, but the distances from point to point are comparable and the differences in ease of travel are extraordinary. It is important to point out that the trip is on the main artery of the high speed lines that enable a traveler to get from Naples to Torino in 5 hours and 25 minutes, a distance of 574 miles! Let’s hope we get high-speed rail in California so the 400 mile commute from LA to SF can become 4 hours in the comfort of a train rather than 6-8 hours on highways. And in Tuscany even commutes on regional lines are shorter at comparable distances, and do not necessitate 3 connections as the Stockton to SF commute does for Sheila.

The passenger train system of the USA is a disgrace. What’s more on most train lines outside the Northeast corridor freight traffic has priority over passenger travel, so one can wait for hours on a single track siding for a long “money train” carrying “precious” cargo to pass by. This was not always so, as there was at one time an extensive passenger system in the US with multiple providers of service. These systems and extensive urban metro systems in surprising places like Los Angeles fell victim to the power of the oil and automobile production lobbies.

Sheila is already ready for a return visit to Italia in 2018. She will probably speak Italian by then, and will spend her time discovering new facets of life in Tuscany. And of course she will ride the rails of Trenitalia and appreciate a modern passenger system. Viva Italia!

Finding Hope

By Brianna Nielson

Health insurance means very little to a person without available and affordable transportation because he still does not have the ability to go see a doctor.”

A couple years ago, I traveled to Rwanda. Winding through the hilly countryside on a bus with my classmates, I would stare out the window and watch the passing towns. I would take inventory of the homes and storefronts. I would study the people. I would ask questions and dream up responses.

What were they thinking? How were they feeling? What were they doing? In other words, how was their head? How was their heart? How were their hands?

At the time, I thought I wanted to be a doctor. I had volunteered for three years at a world-renowned hospital, and I had seen how impactful a single doctor could be on a person’s life. So as we drove, I also wondered what their healthcare system looked like. Were any of these people I observed doctors? Were any of those storefronts medical clinics? What did access to healthcare look like here?

This experience sparked something within me, and over time, my questions have evolved. Now, I not only wonder who has access to healthcare, but question who has access in other areas of life as well. For example, who has access to education? Who has access to travel? Who has access to citizenship? To democracy? To owning property? To freedom of expression? Who has access to solidarity—who is impacted by issues we are willing to stand up and speak out against, and who is impacted by issues we tend to ignore?

As I use this broadened framework to revisit my initial question about access to healthcare, I find myself integrating more nuance and complexity into the discussion. In the United States, for example, when we look at healthcare, we often start talking about insurance coverage. Although universal coverage treats a symptom, it does not cure the disease. Health insurance means very little to a person without available and affordable transportation because he still does not have the ability to go see a doctor. It also means very little to a person working a minimum wage job because s/he still cannot afford to take time off from work to go see a doctor. Even if these barriers are not applicable to a particular individual, s/he still needs the health literacy skills to find a provider and ensure any appointments or procedures will be covered under that insurance. Despite efforts to provide coverage for every individual, access to healthcare is still a system hindered by all the institutionalized barriers and inequalities present in our communities. Those are the same barriers and inequalities that limit access to education, travel, solidarity and the rest.

Increasing access throughout the world requires us to diminish these systems of racism, sexism, poverty, violence, and discrimination. This is a tremendous undertaking, and it often seems one step forward prompts a backlash that leaves us ten steps backwards. In this last year, mixed messages, uncertainty surrounding healthcare, and fear resulting from the federal administration’s stricter immigration policies has magnified the challenges many communities face when trying to obtain health coverage. Recipients of Covered California and MediCal, which in most cases requires you to be a legal resident, are asking to be un-enrolled because they fear the government will punish them for accepting benefits from a federal program, and they would rather go without insurance, risking medical and financial hardships, than risk inviting any unwanted attention into their communities.

I have learned to …”

With each of these un-enrollment requests, my heart sinks; with every effort to repeal or sabotage the Affordable Care Act, my head fills with trepidation. I constantly face the reality that the United States, as an institution, considers healthcare to be a privilege not everyone deserves. For the most part, I remain hopeful we can eventually live in a nation where medicine is not considered a luxury. Through involvement and advocacy, I truly believe every individual has the agency to impact the health and wellbeing of communities throughout the United States.

But remaining hopeful is challenging, and I also experience waves of anger, frustration, cynicism and heartbreak. To move through the obstacles, I have learned to recognize the headway leaders before me have already made. To push for progress in the face of regression, I have learned to adapt in how I approach and address these issues. To promote meaningful change, I have learned to evaluate how I frame the work. This past year has required me to respond with patience, persistence, creativity and passion.

In doing so, I find myself circling back to the questions that brought me here in the first place. Who has access? Who does not have access?

I find myself back on that hilly countryside in Rwanda trying to connect with each individual. What are they thinking? How are they feeling? What are they doing?

I have found human connection to be my source of rejuvenation in this work, and I have found hope in the heads, hearts and hands of those around me.

Saggio da San Frediano # 8 – Lost in Translation – Strike at Amazon in Italia

By Peter Olney

Even though there is no Thanksgiving in Italy, the lack of a “Giorno di Ringraziamento” does not mean that there is no Black Friday. In fact for many years now Italian merchants have celebrated the last Friday in November with discounts that fill their stores with the same bargain hungry masses as in the United States. So Black Friday this year was the day that the three Italian trade union Federations chose as a strategic day to strike Amazon’s million square foot distribution center in Castel San Giovanni near Piacenza in Northern Italy. This was the first strike in Amazon’s history in Italy. There have been some job actions at Amazon in Germany. Italy is a growth market for Amazon and two more warehouses have opened in Northern Italy in Vercelli (mid-way between Milan and Turin) and Passo Corese in the region of Lazio in Central Italy.

The warehouse in San Giovanni is the size of 11 football/soccer fields. The facility opened in 2015. At 5 AM on Friday, November 24 about 50% of the 1600 “Blue Badge” permanent employees stayed off of work and struck. There are however another 2000 temporary “Green Badge”, short term and seasonal employees, most all of whom came to work. Amazon spokespersons insisted that the strike was only 10% of the workforce because of course they were factoring in the temporary employees. Amazon had agreed to sit down with the unions on the Monday following the strike (November 27) but subsequently canceled that meeting. and unilaterally moved it to January 18th. The unions warned that if there were not substantive face-to-face discussions by December 6th that there would be more actions. Amazon on December 5 agreed to meet on December 11th! On December 6th the pressure on Amazon was heightened by a ruling by AGCOM (Autoria’ per Le Garanzie nelle Comunicazioni) the Italian authority charged with regulating all communications. AGCOM ruled that the operations of Amazon were substantially similar to Le Poste Italiane and therefore Amazon was warned that within 15 days they would have to comply with the collective labor contract negotiated for Italian postal workers! Talk about tightening the noose….!

The strike of course received widespread coverage in the world business press. In the United States an excellent article from the left daily Il Manifesto by Massimo Franchi was translated and circulated in progressive labor circles. The issues that led to the strike are certainly universal: pay, health and safety and arbitrary treatment. It is estimated that Amazon workers walk about 20 kilometers on average per day without coffee breaks and with a miserable 30 minute lunch break that is consumed by travel time from one’s work post to the cafeteria: often about 8 minutes. What gets lost in translation are the differences in the industrial relations systems in the two countries.

Sectoral bargaining happens because of the historical power of the largely Communist led labor movement (coming out of the anti-fascist struggle for liberation) which included large scale strikes against the Nazi Fascists.

Three labor federations with their particular sectoral affiliates all calling and leading a strike of their members in one company? Striking without winning certified majority support among the workers? What are we on the moon here? Italy in the aftermath of WW II and mandated by Article 39 of the Constitution has a national system of sectoral negotiations coupled with a very detailed and complicated system of labor jurisprudence. Labor is even sanctified in Article 1 of the post WW II Constitution that states: “L’Italia e’ una Repubblica democratica fondata sul lavoro”! Sectoral bargaining happens because of the historical power of the largely Communist led labor movement (coming out of the anti-fascist struggle for liberation) which included large scale strikes against the Nazi Fascists. Originally in 1947 there was one labor federation, but the interests of the Christian Democrats and the Western capital led to the founding of an additional two major federations (CISL and UIL) in the late 40’s. The employer associations in different sectors meet with the unions and establish a national contract that regulates basic wages and conditions for all the workers in a particular industry. Such is true for warehousing and logistics, and Amazon is not exempt from such basic provisions even if not one Amazon worker is a member of one of the unions in that sector. Our US system of course is enterprise based, and it is a ferocious struggle particularly in the private sector to win a union in one location and apply the basic terms of a contract. It can often take years and much grief and heartbreak for a union to prevail even with the support of 100 % of the workforce. Conceptually the idea of sectoral bargaining resonates with many American trade unionists looking for a way out of the isolation and powerlessness of company specific organization. The Italian sectoral agreements apply to 85% of all Italian workers in companies large and small. Our private sector contracts only cover 6.7% % of the workforce down from 35% in 1955. Such sectoral agreements of course don’t come out of a “good idea” or “an enterprising thought”, these agreements and this system are the product of some of the most violent and militant struggle in the Western world. Thinking doesn’t make it so…

However the Italians while representing most of the workforce in their national agreements only have 30% of the workforce signed up as members (all 3 Federations). This is not good news as the Amazon case illustrates. The unions are free to demand meetings with Amazon to discuss improving on the national agreement. Such improvements are needed. For instance Amazon has basically instituted a permanent Sunday shift. The national agreement calls for a 5% shift premium, but given that this is a permanent shift not an occasional interference with the Sabbath, the unions are demanding a 40% differential for those who regularly work that day. But Amazon feels no compulsion to meet, let alone agree to such conditions unless the workers can flex their muscles in strikes, slowdowns etc. So when the Piacenza facility first opened about three years ago there were initially 23 members of the CGIL. Through patient organizing meetings at work and away from work etc.; all tactics American organizers would recognize, the membership has grown and the strike can go forward. The Vercelli warehouse has just opened and there are only a handful of members among the 500 employees, and there is no capacity to strike, but the organizing continues there and at Passo Corese.

Italian law does not permit the firing or “permanent replacement” of strikers that US law allows in many situations, but nevertheless on the job retaliation and favoritism are not unheard of even for employees who have “permanent” employment under Italian labor law. For instance often employees prefer to pay their union fees on a monthly basis direct to the union rather than having the employer deduct them from their checks. This is protective anonymity in workplaces where the union is still nascent and struggling to build power.

Amazon has become a symbol of the new economy in Italy and the unions are determined to make these new workplaces, union fortresses. While the Italian system has many advantages and represents a far more developed system than our own, patient worker based organizing remains the fundamental building block of any “sectoral strategy”.

Stay tuned, negotiations and maybe more strikes and job actions to come; good organizing permitting….

Links of interest:

Amazon, dipendenti in sciopero durante il black friday: “lavoro usurante. vogliamo condizioni migli – YouTube

Sciopero ad Amazon nel giorno del Black Friday: fischi a chi non ha aderito – YouTube

Saggio da San Frediano #7 – Construction Unionism Italian Style

By Peter Olney

Tourists marvel at Italian construction from ancient times to the Renaissance. Thousands flock the streets of Florence fawning over miracles of construction like the Duomo, the Baptistry and the Belltower. But I am more interested in another side of the construction equation; the workers themselves and the structure of their unions and their practices. I know little of the early guild structure in Italy although I suspect it is similar to the craft structures of England and our own colonial America with young men apprenticed to a master craftsman to learn a trade. In Rome Mercedes Landolfi, the International Affairs Director of FILLEA, graciously offered to discuss Italian construction unionism. FILLEA is the construction section of the CGIL, which, with more than five million members, is Italy’s largest trade union confederation.

FILLEA’s headquarters building was once a hospital and, in 1925-1926, the residence of Antonio Gramsci just prior to his arrest and imprisonment by Mussolini. As a union headquarters, it is modest by American standards—small, cramped rooms, and few staff. But the staff was warm and immediately welcoming. Our informal discussion was capped off by lunch at the Limonaia in Villa Torlonia up the street.

American and European unionists often talk past each other because our labor relations systems are so different. In the United States, 13% of construction workers are represented by unions, particularly in public works, heavy highway and big commercial jobs. In Italy all constructions workers — over one million in all — are covered by national union agreements. There are three major union federations, the CGIL, the CISL and the UIL, all of whom have construction affiliates. They represent building trades workers under master national contracts that all three federations sign. There are about 1,404,000 construction workers in Italy. The CGIL has approximately 25% (353,975) of constructions workers signed up as members, but that figure is more impressive when you recognize that membership is voluntary. There are no “agency” or “union shops” in Italy where membership is a “term and condition” of employment by contract. Workers join the union based on agreement with its mission, presumably with certain clarity and consciousness. This is true throughout the system of Italian industrial relations whether manufacturing or service or construction. Overall union membership in Italy as a percentage of the total workforce is 35%. In the US we are at about 6.7% in the private sector.

The other distinguishing feature of Italian construction unionism, compared to the United States, is that the unions are industrial and not craft-based. All constructions workers regardless of skill, be they electricians or laborers, are in the same union organization. Their skill differences are recognized in their pay categories but not by having a separate union. Mercedes explained that to deal with seasonality a “Cassa Edile” (Construction Fund) exists, financed by the employers, to deal with out of work stipends and medical leaves. Training is done in the same joint fashion as stateside with labor/management training funds and institutes.

In the United States, protecting the rights of immigrant workers, often used as a low wage pool to undermine the unionized crafts, is a vital issue. In the Italian agreements, specific articles protect the rights of immigrant workers. The day after our meeting, Mercedes was headed to Milano to meet with a giant Italian-owned construction multinational that is part of the consortium building the soccer stadiums in Qatar for the 2022 World Cup. She said the FILLEA was pushing that company to sign an international accord to protect the rights of the workforce in Qatar. How does FILLEA convince Italian union members of their interest in such work? She said it was all about raising the floor worldwide for construction workers. Unspoken were the rich, underlying left-wing traditions of internationalism that permeate Italian unionism and transcend workers’ immediate material self-interest.

We discussed women in the trades. In the United States, the numbers are widely recognized to be low—typically below 10%. She said Italy’s numbers are similarly low. However, she mentioned that the majority of the workers on archeology crews are women, and that every major construction company has an archeology staff. Often in Rome, and elsewhere, ground is broken but projects have to halt when invaluable archaeological sites are unearthed. For instance, when construction of a third major subway line in Rome, the Linea C, was stopped when ruins dating from ancient times were found and the archaeology team swung into action. These are workers represented by FILLEA. Women Archeologists of the World Unite!

Wobblies of the World

By Peter Cole

Pluto Press recently published an anthology I co-edited examining the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), whose members frequently were nicknamed and still proudly declare themselves “Wobblies.” In recent years, it may seem that any and all challengers to neo-liberalism have been utterly decimated as its grasp on the world economy continues to tighten. We created this book with that in mind, as we believe the history of the IWW provides lessons necessary for people today. That does not mean to say that we, historians who claim to know History’s trajectory, could have predicted how chaotic and horrid the present moment would be: Donald Trump’s presidency unleashing all sorts of fascist, racist, homophobic, and other hateful forces; a narrow majority of British voters supporting Brexit to divorce themselves from fellow Europeans; Turkey’s leader, Recep Erdogan, doing as best as he can to turn his nation into an authoritarian regime. With Jacob Zuma, in South Africa, utterly betraying the revolutionary potential of the struggle against apartheid; with Venezuela teetering and unrepentant sympathizers of fascism rising in Japan. With economic inequality soaring, union density plummeting, the list of troubles and trouble spots the world over can spin one’s head around and make one wonder if we are, to quote AC/DC, “on a highway to hell”.

The early 20th century, when a few hundred committed radicals founded the IWW, also was a time of great economic suffering and political conflict. As industrial capitalism ascended, hundreds of millions were pulled into its system but the great majority of workers struggled to make ends meet. Inequality on a scale previously unimaginable was unleashed into the world—what the IWW soon called the “Pyramid of Capitalism” in a famous 1911 poster. At that time, reformist labor unions and social democratic parties did not seem capable of challenging the ever-growing power of corporations and their tightening grips over governments. Already, of course, governments had proved ready and willing to dispatch police forces and armies to suppress radical dissent, labor unions, and strikes.

Enter the IWW which, along with anarchist and syndicalist organizations, quickly became a massive and influential presence the world over. The IWW was founded in 1905, in Chicago, Illinois—the United States’ greatest industrial city. Chicago also was the site of the infamous Haymarket Massacre of 1886 in which the reasonable demand for an 8-hour workday died on the gallows along with Albert Parsons and three other working-class activists and anarchists. Not coincidentally, Lucy Gonzalez Parsons, Albert’s widow, was among the several hundred who launched the 20th century’s first great labor union, the IWW. Wobblies quickly fanned out across the United States, northwards to Canada and southwards into Mexico. Down into Central and South America and into the West Indies they went. They sailed across the Atlantic Ocean to the British Isles and then to continental Europe. Wobblies found their way to southern Africa, across the Indian Ocean to Australia and New Zealand, up to Japan, and back again to the America’s Pacific Coast.

Not a socialist nation surrounded by capitalist ones. The IWW always has been internationalist in its vision

Within a decade, the IWW had become a global phenomenon with members and branches in dozens of countries. Wobblies brought with them their fierce commitment to a better world—one in which the benefits of industrialization and technology helped the many rather than just the precious few. To build “a new society out of the ashes of the old,” Wobblies believed the best and only option was organizing on the job. The rich controlled the government and courts despite the hope that, in a democracy, the masses of working people would be able to elect representatives to serve the majority.

On the job, by contrast, workers held tremendous power if only they did the simplest of things—stopping work—for then the entire economy literally would stop. Before radical transformation, Wobblies organized strikes and initiated other tactics “at the point of production” to “get the goods,” i.e. more money, fewer hours, and safer conditions. In the long term, Wobblies hoped to engineer a General Strike that would put workers in the proverbial driver’s seat with the next stop being a socialist world. Not a socialist nation surrounded by capitalist ones. The IWW always has been internationalist in its vision. And not Soviet-style socialism. Before and after the formation of the Soviet Union, Wobblies—along with millions of other syndicalists and anarchists—were skeptical, to put it kindly, of bestowing too much power on a single political party, even one committed to the working class. Hindsight seems to have confirmed their fears of an aptly-named dictatorship of the proletariat.

Although IWW members, literature, and ideas spread to the far corners of the earth, historians and other scholars have had a hard time comprehending that seemingly simple fact. Of course, the union’s name—Industrial Workers of the World—should have been a clear signal but, alas, it was not. Historians are hardly the only ones of course, to fixate on (their own) individual nation-states. And, so, for the better part of a century, historians, workers, students and others interested in the IWW generally focused upon narrow slices of this organization’s history. The IWW in Chile or Oklahoma were studied but not in tandem, not via comparison, and quite rarely considering transnational connections.

Fortunately, historians—forever looking backward—do have the ability to change the present and, possibly, future. This book signals the dawning of a new era in the study of the IWW. While this statement may seem overly audacious, we believe it true. This anthology includes contributions from twenty people who live around the world and have researched the IWW in countries across the globe. Never before have so many different Wobbly histories been told in the same volume. Some chapters focus upon a single individual or group of Wobblies in a specific place. However, what quickly becomes apparent to a reader is how global the IWW truly was. Wobblies were footloose, as Americans sometimes said in the 1910s. That is, they moved around. They rode the rails (often without paying for their tickets) looking for work or to support an IWW strike, free speech fight, or other causes. They also boarded ships and sailed the seven seas. As they did so, they brought with them Wobbly newspapers published in more than a dozen languages (and contributors to this anthology read many of those).

Wobblies and Wobbly publications delivered Wobbly ideals to fellow workers, men and women, in many lands. How else to explain the popularity of the IWW motto, “An injury to one is an injury to all”? This most basic explanation of the Wobblies’ core value, solidarity, is in direct opposition to capitalism which preaches individualism and encourages people to think of each other as competitors rather than fellow workers or even brothers and sisters. It’s true, 112 years after the birth of the IWW, capitalism is still here—perhaps stronger than ever. But, then, so are the hopes and dreams of billions of people who want to share in the wealth they produce rather than allow it to be accumulated by the privileged class. For those people, the Wobblies offer both cautionary tales and useful lessons.

This essay originally appeared on the website of Pluto Press. Thanks to Pluto for agreeing to reprint.

Saggio da San Frediano #6 – Elezioni Regionali – Sicilia – Bellwether for Italia – 2018?

By Peter Olney

Progressive USA is abuzz over the elections that took place on November 8th. Do the victories in New Jersey and particularly Virginia point the way towards a massive reallocation of House of Representative seats in favor of Democrats in 2018? Let’s hope so, and I will be returning from Italy in early 2018 to do my little part in trying to make that happen. But in the meantime ever since we got to Italy in September, the talk has been that the Sicilian regional elections will be indicative of what happens in the national parliamentary elections in 2018. Most of my Italian comrades and particularly the Florentines say that “Sicilia non e’ Italia” (Sicily is not Italy) but nevertheless some of the things that happened in the regionals while we were in the capital city of Sicily, Palermo, are instructive and revealing.

Sunday, November 5, was Election Day in Sicily. All elections in Italy are on Sunday, a very civilized practice, but probably one that has its origins in the Christian Democrats wanting to have a final word with the voters in Mass before they headed to the urns. Sicily is one of 21 Italian regions which elects a President and a regional parliament. The Sicilian Regional Assembly (ARS) meets at the Palazzo dei Normanni, as its name suggests the home of the Norman conquerors of the 1100’s, but also the home (1130) of the first parliament in European history. The Sicilian post war and post fascist parliamentary system of 1947 actually predates the parliament of the Italian 1st Republic (1948) and has its own features, one of which provides for the election of a regional President (Governor) separate from the parliamentary majority.

These elections were seen as the first big battle between the two forces that are predicted by the national polls to battle for power in 2018 on a national level – Centro Destra (Center Right) and Movimento 5 Stelle (Five Star Movement). The Sicilian and national governing party the Center-left Pd is struggling with internal divisions and those too were on display in Sicily. While Sicily is seen as a right-wing region historically, The Pd has governed in Sicily for 5 years since the elections of 2012 brought it to power because of divisions in the Center Right.

The final results were the following after vote counting was completed on Monday, November 6:

· Nello Musumeci of the Center Right – 40% of the vote for President – He himself is from a small Sicilian party but ran in alliance with Forza Italia, Berlusconi’s national party so he was the candidate of five parties.

· Giancarlo Cancelleri of M5S – 34.6% of the vote and all the votes were for his M5S, which as a single party was the largest vote getter in Sicilia.

· Fabrizio Micari – CenterLeft and a member of the Partito Democratico which was the top vote getter in his coalition of 4 parties

· Claudio Fava – Candidate of the Left 6.20% enough to get over the 5% threshold and get a deputy in the Assembly.

In the end because the Presidential vote is not synonymous with the parliamentary vote (people can split their tickets), the Center Right ended up with at least 35 seats out of 70 in the Regional Assembly, enough to cobble together a ruling legislative coalition.

Many in the Western press saw Musumeci’s victory as the reemergence of Mr. “B”, or Il Cavaliere as Silvio Berlusconi is referred to in the Italian press. While he is barred by a 2013 court decision from serving in government, he is seen as a kingmaker and is still the de facto leader of Forza Italia, the party he founded in the 1990’s in the wake of the bribery scandals that rocked Italian politics.

In looking at the leading candidates we can get a flavor of the race and the features particular to Sicily.

The winner is Sebastiano “Nello” Musumeci, an ally of Berlusconi who served in his last cabinet. A very polished politician with a past that would be disturbing even in the United States of Donald Trump and the candidacy of Roy Moore in Alabama. Musumeci came up in Giovane Italia, the youth group of the Movimento Sociale Italiano (MSI), the post war fascist party led by Giorgio Almirante. Musumeci named one of his sons after Almirante and wrote a book in 1991, entitled “Return of the Flame” that celebrated fascism and declared his pride in the culture of Catania, known as the “blackest” (most fascist) city in Italy. Now he speaks of himself as “Fascista per Bene”, a fascist for the good.

The M5S candidate – Gian Carlo Cancelleri – He highlighted his history as a businessman and in grass roots organizing although it appears that his first such grass roots activity was to rally citizen opposition to mandated recycling programs. Cancelleri’s M5S was projected by many to win outright in Sicily, and his party got the single largest number of votes but was beaten by the Center Right coalition. The defeat was stunning because the mercurial leader of the M5S, the Italian comedian Beppe Grillo, had promised victory in Sicily. Because the M5S defines itself as a non-party citizens movement it cannot ally with parties, therefore it is left with the most number of seats (21) in the Sicilian Regional parliament but is resigned to being in the opposition. This scenario could well play out in 2018 on a national scale because again the M5S will not be in coalition or shared electoral lists with other parties and therefore triumph at the polls, but be left out of government

Fabrizio Micari, the candidate of the Center Left was lifted out of the ranks of the Academy with no experience in elected office. He is the rector of the University of Palermo and was chosen as a sacrificial lamb for whom none of the “bigs” of the Partito Democratico were willing to come and campaign. His defeat and ignominious third place finish is more a reflection of the challenges of the left than of his own personal failings as a candidate. The left in Sicily, as in the rest of Italy, is split. This is a dangerous, but not new development, that signals big challenges in 2018.

Claudio Fava, who ran as the left candidate in Sicily and who will matriculate into the Parliament as the one deputy of the left, is part of the national left that split off from the Pd in February, 2016, taking 43 formerly Pd deputies out of the party’s parliamentary constellation. These forces, allied with some of the historic leaders of the old Partito Communista Italiano, (PCI) and the largest Italian Labor Federation, the CGIL, remain critical of ex Premier Matteo Renzi and his 1000 days in office. A time that saw passage of Article 18 of the Jobs Act, which gave employers more flexibility in hiring in small firms but according to the CGIL increased the ranks of the precarious. Fava, himself an accomplished water polo player and excellent speaker, ran a valiant race in Sicily but was doomed from the start to the 6-7% of the vote he ended up getting.

Finally, as with elections in many western countries, those who abstained among registered voters outnumbered the voting electorate. Less than 47% voted in Sicily. This in the context of a 72% turnout in the last national election, a stunning number in light of our low turnout but concerning because between 1948-1976 the Italian turnout was about 92%.

Weinsteins in the Workplace: Will Unions Be Part of the Solution Or the Problem?

By Steve Early

The exploding national debate about workplace harassment of women by powerful bosses or male co-workers is a great opening for unions to demonstrate their importance as one form of protection against such abuse.

Unfortunately, when unions are not pro-active on this front in their dealings with management or, worse yet, allow bullying or sexual harassment among staff or members, their credibility and appeal as a sword and shield for women (or anybody else) is greatly reduced.

Unions don’t exist in a vacuum. They reflect the workplace or occupational cultures of their members, and the latter are a product of social conditioning often unsupportive of solidarity on the job, collective activity, or sensitivity toward women and minorities.

So the task of forging a united front, for purposes of mutual aid and protection in the workplace, is easily hindered by union dysfunction and internal divisions based on race, gender, ethnicity, age, and other membership differences.

It takes continuous organizational effort—in the form of training and recruitment, new leadership development, and structural change–to insure that the bullying, harassing, divide-and-conquer behavior of bosses, big and small, doesn’t infect and weaken the “house of labor” too.

Locker Room Talkers

One of my local union assignments, in a 27-year career representing the Communications Worker of America, illustrates some of the complexities, and ironies, of this challenge at the micro level.

The CWA unit in question had several hundred members, all factory workers in a depressed mill town in central Massachusetts. The union “brothers” greatly outnumbered the “sisters” in this blue-collar workplace. What President Trump calls “locker room talk” was fairly widespread; the culture was rough, definitely not PC, and, in fact, included some vocal Republicans more in love with their guns than the liberal causes or candidates championed by their national union.

When I inherited this local in the early 1990s, I was struck by how many people in the shop seemed to have been bickering with or picking on each other since grade school. The rank-and-file was dispirited, divided, and prone to self-blame, for lagging wages and pension coverage. The union leadership was seen as a do-nothing little club, with no women in it, either as elected officers or appointed stewards.

Members resented their local president for spending dues money on trips to CWA meetings and conferences that benefitted no one else. If workers had a problem or complaint, grievances might be filed on their behalf. But there wouldn’t be any follow-up pressure on management to secure favorable settlements. Everything took place behind closed doors.

The local union president, whose nickname since high school was “Pinky,” sang in the choir of a local church. He was a Navy veteran who acted superior to his blue-collar workmates, and often displayed a hostile attitude toward female co-workers. He believed in issuing orders, tightly controlling information, and liked to end poorly attended membership meetings as quickly as possible, due to “lack of a quorum.”

“Jewing Us Down”?

Since we had begun wage negotiations with the company, I pressured President Pinky to call a meeting, with or without a quorum, to highlight our lack of progress. I entertained the hope that this rare bargaining update might spark some rank-and-file activity he would be unable to quell.

The company’s HR director at the time was a non-gentile from out-of town named Sheldon. And Pinky, despite his own aspirations for a salaried position (which he later got) did not like this particular management negotiator. So Pinky began his bargaining report with the news that Sheldon was “trying to Jew us down” at the bargaining table. The head nodding and muttering throughout the gloomy VFW hall suggested that Pinky, for all his leadership flaws, did know his local audience.

I was a newly assigned union rep not yet known or trusted by anyone in the room, but felt compelled to call Pinky out on this. My interruption began with a reminder that everyone present worked for a big corporation. Local management’s lack of enthusiasm for paying them better had nothing to do with Sheldon’s ethnicity or religion, I explained. Furthermore, as someone married to a Jew, I was not a fan of the phrase Pinky had used because it was part of evil stereotyping that helped murder millions of people during World War II, a slaughter of innocents not ended until VFW members and others helped defeat the Nazis responsible.

Since there were no Jews (or African-Americans) present, I asked how many other people had ever been offended at some point in their life by the slurring of Italians as “Wops,” Puerto Ricans as “Spics,” Irish-Americans as “Micks,” French-Canadian New Englanders as “Frogs,” women as “sluts,” or gay people as “fags”—all in the context of attributing some unflattering characteristic or behavior to everyone in the group so labeled.

A few hands went up. I then noted that talking about other people like this—even if they were in management—did not help us address the problem of how to build the internal unity necessary to win a good contract. Nobody would be getting a decent raise unless everyone in the shop pulled together, stood up, and fought back.

Pinky did not welcome this personal reproach, my related call for collective action, or reality check on where negotiations were headed without it. True to form, the meeting was gaveled to a close quickly. Members left with the assurance that their local officers would handle everything.

Unwanted Personal Contact

Not long afterwards, I got my first opening to help plant the seeds of a better approach, which took another decade to flower. An hourly worker I’ll call Sally—a single-mother, mistreated by men in her past—was threatened with disciplinary action by the company because of her alleged “sexual harassment” of a supervisor! In her version of their interaction, confirmed by co-workers, the married manager who complained about her was actually the initiator of unwanted personal contact.

With the local leadership’s grudging assent, we not only filed a grievance, but also circulated a petition throughout the shop to support Sally. A special meeting was called to discuss her case, an unprecedented approach to “grievance handling” in the local.

Women never active in the union but sympathetic to Sally got the petition signed in every department and shift. Nearly half the membership showed up on a Sunday morning to show solidarity with the grievant. At her first union meeting ever, Sally got a big round of supportive applause, from men and women alike.

Management grumbled, of course, about the creation of such an unexpected and unwelcome ruckus. Despite the murky details of Sally’s actual relationship with the supervisor, disciplinary action against her was dropped. One of the female leaders of the petition drive volunteered to become a union steward and, a few years later, in the post-Pinky era, Peggy was elected vice-president of the local.

She and others became part of a new, younger, more militant leadership of the local, which restored rank-and-file confidence in CWA. This union revival occurred just in time because, by 2001, the company was owned by the Pritzker family, billionaires from Chicago, who were seeking health care give-backs. (Fortunately, Pinky wasn’t still around to link that all-too-common management objective to the ethnicity of the new owners.)

By now, a once sullen, isolated, and dispirited union body was filing group grievances, calling in OSHA inspectors, conducting informational picketing, making allies in the community, and defending good medical benefits in the local media. During contract talks, any member could attend, as an observer, and written reports were distributed, plant-wide, after every bargaining session.

To resist concessions, the local responded with its first strike in 37 years. During that month-long work stoppage, no one crossed the picket-line and women played prominent roles on the strike and bargaining committees.

Left: Leadville, CO., 1984: Moly miners waiting to start work. Right: Long Beach, CA., 1983 Workers at the Long Beach McDonnel-Douglas plant. UAW members. Photos: Robert Gumpert

SAG & SEIU: “Zero Tolerance?

The lessons of this story are several, and hopefully relevant to unions facing virtual extinction today, due to mounting legal and political attacks. A big part of labor’s comeback strategy must involve bottom-up rebuilding of local unions. Greater militancy, internal democracy, and transparency are key elements of that strategy, plus new, more diverse leadership. Challenging retrograde attitudes about women, blacks, Jews, Muslims, Latinos, or any foreign-born workers is an essential part of that task. Replacing labor officials who are obstacles to inclusion is a necessary, if not always sufficient, step toward real union reform.

Among the many job-related concerns that can help build unity–among union members and workers seeking collective bargaining rights –is bosses who bully and harass people. However, unions can best stop such behavior and hold repeat offenders accountable if they have their own act together and avoid complicity with similar misconduct.

In the Toronto Globe And Mail last month, one outspoken Harvey Weinstein victim—Canadian actress Mia Kirshner—accused both of her unions, the Screen Actors Guild (SAG) and the Alliance of Canadian Cinema, Television, and Radio Artists (ACTRA) of offering “inadequate protection” against “sexual harassment and abuse in the film industry.”

Kirshner’s blistering critique was seconded in Jacobin by Morgan Spector, a New York-based television, film, and theater actor. He also faulted SAG, which has a female president, for not being aggressive enough on behalf of aggrieved members– despite an official union policy of “zero tolerance” for sexual harassment.

Worse yet, in Bloomberg News, a former hotel union staffer-turned-journalist, Josh Eidelson, just blew the whistle on misconduct by a top Service Employees International Union (SEIU) leader, in charge of its “Fight for 15” campaign among fast food workers. The career of Scott Courtney, Executive Vice President of SEIU, had previously been promoted by Mary Kay Henry, the union’s national president. But, in mid-October Henry suspended him from his $250,000 a year position because, as Eidelson reported, “people working for Courtney had been rewarded or reassigned based on romantic relationships with him.”

Courtney has since resigned, before he could be fired, as demanded by UltraViolet, a women’s group which called his conduct “wholly unacceptable.” And, as Buzzfeed News has reported, two male SEIU staffers who reported to Courtney have also been fired or put on administrative leave in Chicago, based on allegations that he protected them, despite co-worker complaints about their bullying behavior involving women.

Press coverage of this union scandal is tainting SEIU’s reputation and credibility as a defender of fast food workers, who are often subjected to similar harassment by low-level managers in their industry. It’s a propaganda gift to anti-union employers everywhere, from McDonalds to your local manufacturer. Already, neo-liberal media outlets like The New York Times are writing unions off as a contributor to any “real and lasting transformation” of American workplaces, “in the wake of Harvey Weinstein’s expulsion from Hollywood” and the outing or toppling of other high-profile predators.

In a lengthy October 29 editorial about next steps toward “lasting change,” The Times called for safer work environments, more enlightened and transparent management, and stronger anti-discrimination protection. While marveling at “what a difference it can make when women join together—and men join with them—to confront harassers openly,” the editors failed to note that collective action, of this sort, is best organized and sustained by a well-functioning union.

When labor organizations like SAG or SEIU don’t quickly confront Weinsteins in the workplace, particularly in the situations referenced above, they’re just confirming management claims that unions are weak, irrelevant, and hypocritical as well.