The Tragedy, the Drama…and the Hope. An alternative take on the 2018 Italian Election

By Anonymous

Sunday March 4th 2018 was a tragic day for Italy. The political election had no more than a little part in it.

An unexpected loss shook the hearts of the Italians when Soccer Player Davide Astori, captain of Fiorentina Football Team, passed away in the night between Saturday and Sunday due to an alleged heart attack.

The departure of a paradigmatic example of sportsmanship and loyalty on and off the field, a beloved father of a 2-year-old daughter could remarkably tear the attention off the election in both newspapers and (Social) Media.

We might be wondering how this could happen, considering the economic struggles, the still high unemployment rates, the emergency of migrants, and all the other issues and challenges that Italy was and still is to going to face in the next future.

We might discuss at length how was it possible for Renzi’s PD to squander in a few years the trust of the electorate, passing from almost 40% majority in the European Election of 2014 to just over 20% of the voters of National election in 2018.

We could argue that PD suffered from its inability to find a channel of communication between voters (i.e. citizens) and the political establishment.

We might sight underestimated signs of their staggering consensus in the popular music (e.g. in the song “Comunisti col rolex”, very popular among youngsters, liberal artist J-Ax was clearly blaming the hypocricy of – at least a part of – the left-winged Intelligencija) and in the newspapers, sliding comfortably and progressively from appraisal to criticism.

We could debate whom the “winner” of the election was, either the Right-Winged Matteo Salvini, in his role of leader of the coalition recording the relative majority of the votes (together with a steeply declining Silvio Berlusconi), or Luigi Di Maio, in his role of leader of the party which individually recorded most preferences, the populist Five-Stars Movement.

We could raise concerns on their feasibility of both their electoral promises, respectively, an extensive Trump-akin fight against illegal immigration (with no walls, but only because most migrants come to Italy with ships…), and the introduction of a universal basic income that no struggling Country could ever afford.

Conclusively, we could question the promises that few could reasonably believe in and we could even doubt that the PD was the ultimate loser, since its representatives in Parliament are now enticed by the “official” winners looking for “external” supporters.

We could, but it would be pointless.

In fact, in the wake of the election, no party was expected to rise up to 40% of votes and thus to “manage” or “control” the relative majority of the seats in the Parliament, which is the condition to be able to autonomously set a Government.

Indeed, one may even argue that the overall results were largely foreseeable from the beginning.

This let us guess that, if new election took place, the outcome would not be radically different.

Therefore, it is likely that a coalition government is appointed and the position of the parties that today play their role as counterparts will have to be mingled and settled.

Notably, a few days after the Election, the prominent Manager Sergio Marchionne and the President of Confindustria (the main Italian Employers’ Association) Vincenzo Boccia reckoned that the Country had faced worse times in the past and they both expressed their faith in the future.

Their statement immediately reminded me of President Obama’s speech following President Trump elections: “no matter what happens, the sun will shine in the morning”.

The past of our beautiful Country shows that we when it comes down to safeguard the future of our children we can still find the necessary unity, as our political class – which is nothing but our image – is expected to do.

We constantly fall out and bicker over seats, offices or even football games, but we hear that a two-year old girl will not be able to be kissed goodnight by her daddy anymore, we can still find our unity in solidarity, like the thousands gathering in Florence from everywhere to give their tribute to Davide Astori and to his family.

At the very end,

“It is all settled beneath the chitter chatter and the noise, silence and sentiment, emotion and fear, the haggard, inconstant flashes of beauty, and then the wretched squalor and miserable humanity, all buried under the cover of the embarrassment of being in the world, blah, blah, blah, blah. Beyond there is what lies beyond. I don’t deal with what lies beyond. Then, let this Novel begin. After all, it is just a trick.

Yes, it is just a trick”.

From “The Great Beauty”, Final Monologue

The San Frediano People’s Tour – Avanti Popolo! – Lonely Planet be Damned!

By Peter Olney

Flash – In 2017 Lonely Planet designated Borgo San Frediano first on the list of the Ten Coolest Neighborhoods in the world. Most of that content is dedicated to describing fancy bars and eating spots. We can do better than that……. Here is a 4-hour tour that ends in a satisfying lunch or “pranzo”.

For convenience sake the Avanti Popolo tour begins at Piazza Tasso and ends there! Besides being our residence, the Piazza is a very historic part of the neighborhood or “rione” that is called San Frediano. San Frediano is in the “Oltrarno – o “al di la del Arno” as the Florentines say. We are away from the madding crowd of tourists near the Ponte Vecchio and the Duomo and most of the other heavy touristy areas on the north side of the river. San Frediano is a smaller part of one of the 4 traditional “quartiere” of Florence: Santo Spirito. These four sections of the city: San Lorenzo, Santa Croce, Santo Spirito and Santa Maria Novella constitute the core of medieval Florence and to this day are represented by area “football” teams in the Calcio in Costume”, a brutal game that has evolved into a cross between rugby and bare fisted boxing. Santo Spirito’s team is called “I Bianchi” and many of the players come from the San Frediano “rione” and frequent the Giglio Bar on Viale Petrarca south of Tasso. Simone and Luigi are the proprietors and both are hefty competitors in both rugby and Calcio in Costume.

Have a morning coffee at Bar Tabacchi Giglio (Viale Petrarca #2 Red) and then pick up your morning “Giornale” (NY Times if you like!) da Andrea in the storefront with La Nazione written above the entrance. This “Edicola” or newsstand doubles as a bookstore and Andrea is a knowledgeable historian of the neighborhood and also sells bus tickets for the ATAF, the city’s bus system. The tickets are 1.20 Euros or you can buy 10 rides for 10 Euros. BTW if you want to ride rather than walk and do the city panorama from Piazzale Michelangelo, the #12 Bus ATAF leaves from in front of Andrea’s and takes you there. To get back to Tasso you take the #13. But that is a diversion from the Avanti Popolo tour of San Frediano.

Much of San Frediano grew up around the Monastery of the Camoldesi Monks (Thus the name Via de Camoldoli on the west side of Tasso). This handsome building which houses the City branch library named Pietro Thouar, has served many functions over the years including that of a leper colony in the 16th century.

Visit the Pietro Thouar library and go up to the Terzo Piano (our 4th floor) for a spectacular view of the city skyline and also the use of a clean well-lighted bathroom.

Communities grew up around churches, monasteries and convents. San Frediano was home to a huge concentration of artisans and industry.

Walk down Via del Leone and across from the Catholic Thrift Shop at 27 Red, which supports the immigrant and people’s assistance project, Arco Balena, and there is a shop at 28 Red that makes violins and cellos for musicians all over the world. You may have to knock on the door to get access, but go inside and check out the amazing craftsmanship.

San Frediano was once home to much more large-scale industry. Let’s walk to two locations that highlight that industry. Proceed north to the corner of Via del Leone and Via Del Orto and turn left and continue on to Piazza de Nerli where you will turn right and head straight towards the Ponte Vespucci that crosses the Arno. However before you reach Vespucci you will find Il Tripaio Fiorentino at the northern edge of Nerli.

Stop at the Tripaio for lunch and have a tripe sandwich (cow stomach on a bun with seasoning) or if you are really daring try a Lampredotto sandwich made from the last stretch of stomach of the cow or as the Italians say the place “prima che esce l’aire” (before the passage reaches the open air). Lampredotto is like pastrami but a little softer but well seasoned and a Florentine working class lunch.

After you have finished savoring what Florentines consider the third dish in their gastronomical trinity, the other two being a peasant stew made from leftover bread and re-boiled vegetables called “ribollita” and the hearty Bistecca alla Fiorentina, we are heading to the Vespucci Bridge on Via San Onofrio after crossing the street named Borgo San Frediano. On our left we turn to head down Via L. Bartolini which leads to the Poste Italiane but

Before arriving at Le Poste look on your right for the Setificio Fiorentino, a silk factory still in operation. Heading back east on Via Bartolini you will arrive at Piazza Del Tiratoio (Place of the Hanging) not the gallows but a place where silk and other fabrics were hung to dry after production and dying. If you have time you also might want to visit Piazza Piattellina where copper was fabricated to be used on leather goods.

The final leg of the Avanti Popolo tour takes us back to Piazza Tasso. The Plaza gets its name from the 16th century writer who in 1512 penned the masterpiece Gerusalemme liberata that creates a fanciful story of the conflicts between Christians and Muslims. But it is the Piazza’s more recent history that interests us today. San Frediano according to historian Stefano Gallerini, “Was the beating heart of Florentine popular anti-fascism.” In 1944, the allies were moving up the Italian peninsula and the Nazi/Fascists were in retreat. On July 17, 1944 fascists machine-gunned a mass gathering in Piazza Tasso brutally slaying 5 locals including Ivo Poli an 8-year-old boy. 2 days later a massive funeral cortege marched through the streets and Piazzas of the neighborhood: Piazza Tasso, Via del Leone, Piazza Piattelini, Via del Orto, Via di Camaldoli . The crowd chanted: “Morte al Fascismo”!!!

Opposite the Pietro Thouar library there is monument to the 5 victims of the Nazi-fascists and the well-used children’s playground in the park is named for Ivo Poli. Notice that the monument has fresh flowers and there is a commemoration of the event every year carried out by the Associazione Nazionale di Partigiani Italiani (ANPI) whose main office and social club in Toscana is in the same building as the library. Needless to say most of the actual partisans are dead, but the Association continues the work of spreading the anti-fascist gospel. .

You will notice if you look due south from the anti-fascist monument that the Viale is named Viale Vasco Pratolini. Pratolini is famous for his participation in the resistance but also for his writings that chronicled the neighborhood of San Frediano. His most famous book is called The Girls of San Frediano (Le Ragazze di San Frediano). It was published in 1947 post WW II and tells of the amorous exploits of a San Frediano named Aldo whose good looks earn him the nickname “Bob” after the American movie star Robert Montgomery. “Bob” is stringing along five women all at the same time. Each is abused and heartbroken by him until they finally decide to unite and end up giving him a public physical thrashing. The book was made into a movie in Italy in 1954 and a RAI television series in 2007.

Let’s end our tour with a modern miracle. On the northeast corner of the Tasso Square where Via del Leone empties into the Piazza there is the “publiacqua” dispensary. This is a free water dispensary where you can fill all your bottles up at any time with fresh spring water or sparking mineral water or as the Italians call it “frizzante”. This eliminates the need to buy bottled water, and every morning Italians tote big crates of bottles to be filled in the public square. Some say this water system(which is in other squares throughout Florence) has its origins under the mayoral term of ex Premier Matteo Renzi. My friends assure me that it was the term of Leonardo Domenici, an ex Partito Communista Italiano (PCI) militant who originated the idea and its implementation. So be it, but can the Nestles of the world be happy about this? .

That ends our Avanti Popolo tour unless you are hungry in which case you have many choices in the neighborhood. A block north on Via del Leone is l’Brindellone (Piazza Piattelina 10) which serves its customers a fine and economical lunch or dinner at big wooden tables. Tratoria Sabatino is a family style restaurant with great prices near the Porta San Frediano(Via Pisana 2/Red). A little further west on Via Piasan at 140/R is Bar Pegaso. This is a winner for an inexpensive but tasty lunch. You will share it with the local artisans and working class.

But if you want to stay close to Tasso then try the Trattoria BBQ joint at the northeast corner of Tasso 9/10 Red across from PublicAcqua. The food is great, but be careful if you try as our friend Noli did, to cut your taglietelle pasta with a knife. Simone the waiter will surely come out with a meat cleaver and grab your arm and attempt to chop it off. Only “bambini” have their pasta cut with a knife! Oh and gelato? Go next door to Tasso 11/Red and try La Sorbetteria.

Avanti Popolo alla riscossa, Bandiera Rossa la Trionfera'” ENJOY!

So Wakes the Black Panther

By Gary Phillips

“Nobody gives a shit about any of the other Marvel characters. Go back and make a deal for Spider-Man only.” A directive from a Sony executive in 1998 according to Ben Fritz in his recent book, The Big Picture: The Fight for the Future of Movies.

Marvel at the time was exiting bankruptcy and had offered the film rights to a whole slew of their characters for a fast $25 million. Sony passed. Flash forward…post Disney buying the comics company for $4 billion. A slew of those characters from Deadpool, Guardians of the Galaxy, Thor, Iron Man, Captain America and even the C-lister Ant-Man made big box office. Though it is notable Daredevil, Elektra and the Ghost Rider flicks didn’t exactly set any movie going records.

Now comes the Black Panther. He’s a character first introduced fifty-two years ago in the pages of Fantastic Four #52, July 1966, in the wake of Malcolm X’s assassination and the Watts uprising. Depending on which Marvel lore you believe, either Stan Lee as writer and Jack Kirby as artist together came up with the character, Stan Lee by himself as he claims in the documentary With Great Power because he thought the time was right for more black comics characters, or Kirby alone, more or less for the same reason.

For the geek fanboys out there keeping score, I’m in the Kirby camp. Nonetheless, the Panther made the scene, does in fact grace the cover of that FF issue. Though again, like so much of inside comics that is analogous to race relations at any given time period, the initial version of the cover by Kirby had BP in a half mask making it clear he’s a black man. The one that ran, his mask fully covers his face as supposedly the higher-ups at Marvel were worried a brother prominent on the front of the book would hurt sales.

While Black Panther wasn’t a runaway hit, he did make an impression on kids like me growing up in South Central, happy to see the arrival of a black superhero. It took some time for him to get an eponymous title. His first feature run was in Jungle Action, a title Marvel had maintained since the ‘50s. The company was then known as Atlas, and the book featured all sorts of white b’wanna jungle lords in the Tarzan mold.

Yet this is a character who as often as he’s had his own title, has had those titles cut out from beneath his agile feet time and again because of poor sales. The adage in comics like movies that the majority white readership won’t support a black lead. But as of this writing, the 2018 movie bearing his name has earned upwards of $897.7 million worldwide. What is it then about this moment in the United States in particular that the Black Panther, T’Challa, son of T’Chaka, brainy warrior king of the scientifically advanced hidden African kingdom of Wakanda, has struck this kind of chord, invoking pride and optimism like Roots did back when? Folks coming out to the theaters in their African finery, celebs and community organizations buying out screenings for young people, Afrofuturists heralding Black Panther as an agent of a change of perception and some seeing the movie three or four times because they want to inculcate all of its nuances and meaning.

Overall I dug the movie. My wife, a veteran community organizer and director of community action organizations, also enjoyed the picture, and she is no fan of Marvel movies or action-adventure movies in general. For it isn’t like the script didn’t lift from the Panther comics storylines and characters written by the likes of Don McGregor, Christopher Priest and Reginald Hudlin (producer on Django Unchained and Marshall) among several others. All Marvel and DC Comics movies and TV shows have taken from the source material. Certainly the film too owes a good portion of its visual style to that endless phantasmagoric imagery Kirby: populated his comics with over all his years of toil.

This cathartic cinematic super black experience has been building. When streaming service Netflix premiered Luke Cage (created as a response by Marvel to the influence of blaxploitation films in 1972 by Archie Goodwin, writer and George Tuska, artist) in 2016, the site crashed there was so much pent-up demand for a “bulletproof brother” in a time of Black Lives Matter. And the new network show Black Lightning (from DC who got on the bandwagon a little later in 1977, the character created by writer Tony Isabella and artist Trevor Von Eden) has garnered some residual BPness. Witness a recent episode echoing Charlottesville where white supremacists linked arms to encircle a Confederate statue chanting, “You will not replace us,” as multi-racial protestors encircled them.

Nor is Black Panther the first black super hero movie. In 1993 Wesley Snipes had an interest in playing the Black Panther and approached Marvel. For various reasons as Snipes recounts in a recent Hollywood Reporter piece, the movie couldn’t get made. But his dealings with the House of Ideas led him in 1998 to play Eric Brooks, aka Blade, an angst driven, half-vampire, half-human vampire killer created by writer Marv Wolfman and artist Gene Colon in the pages of the Tomb of Dracula comic. The Blade movie made money. That and its two sequels helped pave the way for where we are now – a mix of the hyper ideal and the real.

These black superheroes might face down super villains like Doctor Doom and Lex Luthor, but in civilian clothes driving their car to the next Justice League meeting, they could be stopped by the cops because they “fit the profile.” Reality has even intruded in Metropolis. In Action Comics #987, Superman zooms between a pissed-off white guy wearing an American flag bandana who is distraught at losing his job, and some undocumented workers he was trying to gun down.

Is Black Panther’s appeal then as Jamil Smith observed in his Time cover story, “The Revolutionary Power of Black Panther,” such that “After the Obama era, perhaps none of this should feel groundbreaking. But it does. In the midst of a regressive cultural and political moment fueled in part by the white-nativist movement, the very existence of Black Panther feels like resistance.”

Had Clinton been victorious, and the status quo remained “normal,” would Black Panther have the same widespread resonance? I think to an extent it would have, but there’s no denying Smith’s point. The Wonder Woman movie of last year was viewed through a similar lens, an answer to the misogynism of Trump and his ilk. Added to the mix is the subtext of horror film Get Out (writer-director Jordan Peele won the Oscar for best original screenplay), a metaphor for being woke. Is this then a sign of an awakening of those who stayed home for various reasons in November 2016, answering the theme of standing up issued from the silver screen? Activism is on the move and on the voting front, the dems have been racking up wins for statehouse seats. Some in places where Trump won handily.

If a more reflective pop cultural story can inspire us to stay in or get in the struggle be it organizing or the electoral arena or creating more fictions that like vibranium, the space metal upon which Wakanda was built, absorbs then can redirect hostile energy, then maybe the words of the Black Panther from his first appearance those five plus decades ago still have meaning. “A victory too easily won is too soon forgotten!”

Italian National Elections – Sunday, March 4: An Analysis from Florence, Italy

By Nicola Benvenuti

The Italian elections of March 4, 2018 are novel and important in that they will mark the end of political bipolarism (Partito Democratico vs. Forza Italia) because of the role that two populist parties, Movimento 5 Stelle (Movement 5 Stars) and La Lega (no longer Lega Nord) will play, as well as for the effects they will have more generally both on Italian politics and on European politics.

Sunday is both the day of Italian parliamentary elections and the day of the referendum count in the SPD (German Social Democratic Party) on whether to approve or reject the Schulz-Merkel agreement. This conincidence emphasizes the centrality of the European theme. In Germany approval of the referendum in support of the Grosse Koalition between CDU and SPD could relaunch the European economy after years of financial rigor (just think of the ceding of the Ministry of Finance to a Social Democrat). But a failure will prolong German internal uncertainty and accelerate the disintegration of the EU. To consolidate the shaky agreements on monetary policy and restore popular vigor to the idea of Europe by blocking the development of populism fascistoids, as well as to address the most important issues that can no longer be solved strictly on a national level, a political and democratic architecture must be completed for the European Union and there must be regulatory unification – particularly fiscal.

In the European Union (EU) the agreement Merkel/Macron can open a new phase in the development of the EU and Italy has all the cards to play among the leading countries on this new course, provided that a reliable majority that is pro European prevails in the national elections.

Unfortunately, it seems that in Sunday’s Italian elections for the first time in thirty years we will not see the left and its allies contend for the government. Though the present party of the government, the Partito Democratico (PD), presents, in comparison with the demagogic programs of Berlusconi, Salvini and M5S, a more reliable program, it is in great difficulty, while LEU (Liberi e Uguali), which collects the exiles of the PD and the former Sinistra Italiana (Italian Left), does not seem able to be able to gain ground and collect all the dissatifaction from and disaffection with the Ex Premier and present PD party secretary, Mateo Renzi.

For its part, the PD is suffering from the unpopularity and rejection of Renzi himself aroused by the numerous errors committed by his government (the first of which is having lost the constitutional refendum in December 2016 which seemed on the merits to be winnable), his presumptuous attitudes and his failure to prevent the rift in the party (to the dismay of all the “noble fathers” of the PD, Napolitano, Prodi, Veltroni …). It is no accident that the PD prefers to identify today with Prime Minister Gentiloni and not the “rottamatore” (“Scrapper” of the political establishment) Renzi, the Party Secretary.

At the moment therefore the 2 movements that are contending for first place are the coalition of the Right and the M5S, but it is unclear whether either bloc can arrive at 40% of the vote, the share necessary to trigger the award of additional deputies in order to create a parliamentary majority and a government. The Camera dei Diputati has 630 members so a majority is 316.

The right is thought to be the prevailing alliance (Forza Italia, Lega, Fratelli d’Italia and other small groups belong to it). But this is a fake alliance. The parties that make it up have radically different positions. Let’s take the two main ones: the Lega di Matteo Salvini wants to abolish the Fornero law that brought high health care spending under control. Forza Italia is against the abolishment of Fornero. Forza Italia proposes a flat tax at 25%, which Salvini instead would like to see at 15% (“I’ll give you more” says an old Italian song that summarizes the faulty logic of so much Italian politics, often also on the left). The conflict on the right is clearly about which of the two, Salvini or ex premier Silvio Berlusconi, will lead the coalition (Brothers of Italy (Fratelli d’Italia), Giorgia Meloni’s party takes second seat). And above all, the Lega is anti European (but Salvini is mitigating a bit of his hostility), while Berlusconi has represented himself as of the EPP (European People’s Party), a group of which Forza Italia is part of in the European Parliament, as though FI is the guarantor of Europeanism in Italy. As much as the Italo Right transformation reminds us that even to get money and power you can give up everything and say anything, it seems that especially on Europe the break will be difficult to overcome when the EU has to impose austerity on the easy spending of a right-wing government.

There remain allegations and illusions about the possibility that Renzi and Berlusconi can agree on a sort of big coalition in the name of the EU: after all, it will be remembered that the Renzi government was blessed by the Nazarene pact (Aggrement between Renzi and Berlusconi to mutually support consitutional reform of the Senate and electoral reform) – January 18, 2014 – with Berlusconi! The electoral projections at the moment make this perspective problematic: the PD is at 21.5%; FI at 18%. The PD will hope that its allies do not reach 3%(the threshold for seats in parliament) and then, as the electoral law just approved mandates, give their votes to the PD. Salvini is rising in the polls, and FI will rely on a fringe in the League led by the former President of the Lombardy Region, Maroni.

It is more difficult to evaluate the M5S, polling in the last surveys at around 29%. The fact that the right-wing coalition led by FI and La Lega is the main competitor means that M5S tends to turn to the left to attract votes. On paper it could turn out to be the top vote getter, and the President of the Republic could grant it the exploratory task of the formation of a government, but the M5S refuses to make alliances, in order to enhance its image as an antisystem force, and perhaps it hopes to find agreement in parliament on individual issues. The premier candidate, 32 year old Luigi Di Maio, has started to make public the names of the prospective members of his government, proposing the General of the Carabinieri Sergio Costa, the mover of the investigations on the Land of Fires (the story of toxic waste buried in the agricultural fields of Campania by organizations related to the Camorra ), for the Minister of the Environment. Other names will be made public in the coming days. The program has been refined and made more specific in contrast to the very demagogic initial buzzwords, but the weakness of the M5S remains the unreliability of its precarious process of selection of political personnel through the online network and under the control of the Casaleggio company (Casaleggio Sr. was a computer whiz and the founder of M5S with comedian Beppe Grillo).

Among the many other parties in the running, it is important to highlight above all LEU (Liberi and Uguali) led by Pietro Grasso, President of the Senate, and by the President of the Chamber of Deputies Laura Boldrini. The backbone of this formation is however made up of by exiles from the PD, first and foremost Bersani and D’Alema , and cadres from Sinistra Italiana (Italian Left). The latest polls (after the 17th of February opinion polls can no longer be disclosed) gave them 5.4%. It is difficult to hypothesize their political role after the elections, except in the case of the impossibility of forming a new majority, and therefore in external support of the current Gentiloni government if it were extended by the President of the Republic with the task of making a new (again!) electoral law with which to hold new elections (this was a point D’Alema made in a recent interview).

Another new party that has aroused some interest on the left is Potere al Popolo (Power to the People), a formation born of a lively movement from below to redefine leftist politics and initially led by two civil society personalities, Anna Falcone and Tommaso Montanari: the former then joined the lists of LEU, while the latter is mentioned by some press as a possible Minister of the M5S. Potere al Popolo is polling at 0.8%

The most attentive readers will note the absence in this piece of mine of the immigration theme that also inflames all the “apolitical” transmissions of Berlusconi’s networks and the actions of the League and feeds the aggressive climate enabling the reappearance of fascist violence (see city of Macerata massacre carried out by an ex Lega party candidate against African immigrants earlier this year)). This is a very serious issue, but unfortunately it has been used mainly for political propaganda, although most of the parties, especially those who protest most vehemently, do not have viable positions (only the watchwords: “let’s send them all home, block them at sea”, etc.) . This time the PD, thanks to the Minister of the Interior Minniti, can show the results of the initiation of a policy of departure control from Libya that, although implemented late in the game, nevertheless is the basis for an immigration policy on which the EU also agrees, as evidenced by the recent informal meeting on EU immigration policy in Brussels between Gentiloni, Macron and Merkel.

Now, as is obvious in a predominantly proportional system, all evaluations are postponed until the numbers come out of the March 4 elections. We shall see……

Teacher Walk-Out Will Continue Monday, Union Leaders Say

By Dave Mistich, 100 Days in Appalachia

This piece comes from 100 Days in Appalachia – a site we at the Stansbury Forum recommend taking a look.

West Virginia teachers will continue their strike into next week, the latest response to what’s quickly becoming a deepening rift with the governor and Legislature over pay and health benefits.

Thousands of teachers and school service workers in all 55 counties will remain off the job Monday, union leaders announced at a news conference Friday afternoon.

“It is clear that education employees are not satisfied with the inaction of legislative leadership or the governor to date,” according to a joint statement from the West Virginia Education Association, the American Federation of Teachers’ West Virginia chapter, and the West Virginia School Service Personnel Association. “Our members have spoken and the Legislature has not.”

A loud cheer echoed through the halls of the Capitol from teachers listening to a live feed from the news conference on their mobile phones.

West Virginia Education Association President Dale Lee said county school superintendents are being asked to keep schools closed for a third day because the teachers will return to Charleston. The walkout that was in its second day Friday already has drawn large crowds each day.

A state Department of Education spokeswoman declined comment. State Schools Superintendent Steve Paine said early last week that the work stoppage is illegal and disruptive to student learning.

Missed class time is automatically added to the end of the school year.

“This is not an easy decision to make,” Lee said. “But it’s a decision that our members in every county gave us the authorization to make.”

Senate President Mitch Carmichael said after the announcement that he is disappointed that the union leaders are continuing the work stoppage, calling it an illegal strike that sends the wrong message to students and the state as a whole.

Gov. Jim Justice has signed teacher pay raises of 2 percent next year and 1 percent the following two years. But teachers, who rank 48th in the nation in pay, have said the increases are too stingy. They also complain about projected increases in health insurance costs.

The Public Employees Insurance Agency, a state entity that administers health care programs for public workers, including teachers, has agreed to freeze health insurance premiums and rates for the next fiscal year for state workers.

The House of Delegates has passed separate legislation to transfer $29 million from the state’s rainy day fund to freeze those rates and to apply 20 percent of future general fund surpluses toward a separate fund aimed at stabilizing the employees’ insurance agency. Both bills are now pending in the state Senate.

Teachers are worried the proposed solution is only temporary or worse, especially if the state surplus turns out to be minimal.

Earlier Friday, Senate President Mitch Carmichael addressed the Capitol crowd briefly, telling them that “your points are well made. You have every right to make them and we hear you. We’re taking steps to address your issues.”

The crowd quickly interrupted him with chants, and he thanked them and left.

Before the Senate adjourned for the day, Greenbrier County Democrat Stephen Baldwin said he understands that tensions have been high and that “there’s a sense that trust has been broken over the years. But I believe we’re in a pivotal moment where that trust can be repaired now if we show each other some respect and we show each other some human decency.”

The Associated Press contributed to this article.

This article was originally published in West Virginia Public Broadcasting.

The Women Behind the Black Panther Party Logo

By Lincoln Cushing

All graphics have a story to tell. Some logos of 20th century political movements have become recognized the world over – the peace symbol, designed by Gerald Holtom; the United Farm Workers logo, created by organizers Cesar Chavez and his cousin Manuel; and the Black Panther Party logo, designed by…whom?

That would be Dorothy Zeller.

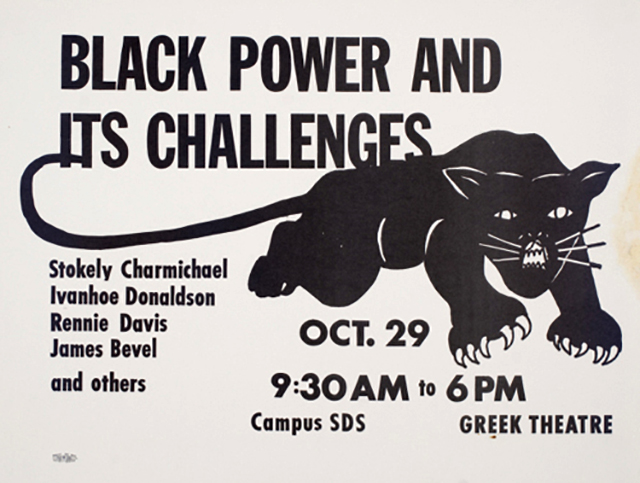

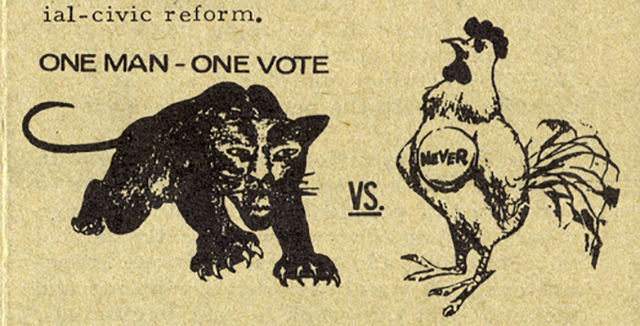

The Black Panther Party logo’s roots go back 1966, with the Lowndes County Freedom Organization in Alabama (also called the Black Panther Party). It was a political party running progressive African Americans for office, and state electoral law required such groups to have a logo on their ballot to make it easier for illiterate voters. Although there was no formal organizational relationship between that Black Panther Party and the subsequent Black Panther Party for Self Defense organized in Oakland, California, several figures – including SNCC field organizer Stokely Carmichael – served to bridge these two key organizations in the Black power movement.

In a speech delivered at the 1966 S.D.S.-sponsored “Black Power and its Challenges” conference at U.C. Berkeley, Carmichael said:

We chose for the emblem a black panther, a beautiful black animal which symbolizes the strength and dignity of black people, an animal that never strikes back until he’s back so far into the wall, he’s got nothing to do but spring out. Yeah. And when he springs he does not stop.

The all-white Alabama Democratic Party’s graphic was a white chicken. According to civil rights veteran Scott B. Smith, Jr., a clenched fist had also been proposed as a graphic for the LCFO – but was rejected in favor of a “black cat” with superstitious powers.

But the graphic first used in that campaign bears little relationship to the streamlined, powerful graphic associated with the BPP. Enter Dorothy “Dottie” Zellner. I interviewed Dorothy in 2016 and she explained how it happened:

I was working in the Atlanta office of Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee when I was approached by Stokely Carmichael because he knew I’d gone to the High School of Music and Art. He’d gone to a sister school, Bronx High School of Science. He asked me to draw a panther for the Lowndes County Freedom Organization campaign. I said no, I wasn’t that capable an artist.

Stokely asked my then-husband Bob Zellner to go to the local zoo and take some photos of the panther there, but they weren’t any help.

Bob Zellner was a minister’s son from Alabama, and he reflected on this event in a 2006 listserv discussion of veterans of the civil rights movement:

One day [James] Forman told me to get a SNCC photographer and go with him to the Atlanta Zoo and take a picture of a black panther. “He is lazy so you may have to poke him to make him growl,” Forman said. “Bob, you poke him and the photog can get a growl, maybe. See what you can do.” We got several shots and returned to the office. Forman took the film into the dark room and came back with wet photos. He asked everybody in the office, “Who can draw?” Dottie said, “I went to art school, I’ll take a shot at it. Forman, what kind of picture do you want?”

Forman said, “Make him growl and show some teeth.” I don’t know why we always referred to the panther as “he.” He could have been a she, as far as we knew. Dottie refined the first rough drawing of the now famous Black Panther. Dottie drew it so it would reproduce well in black and white — a panther with curled tail, bared teeth, and pronounced whiskers, ears perked up.

Dorothy further explained:

The next time Stokely asked, he showed me a rough line drawing of a panther – it really looked more like a cat – and asked if I’d try again, so I did. I cleaned it up, added better whiskers, and made it black. at his request.

The next time I saw it, that image was on TV sometime in 1967 – I was shocked!

Many years later I learned that the drawing Stokely had given me was done by Ruth Howard, and was based on a school mascot of one of the HBUC’s in the Atlanta area. [That was Clark College, now Clark-Atlanta University]

The panther name and logo was then taken to the San Francisco Bay Area by community activist Mark Comfort when he formed the Black Panther Project of the Oakland Direct Action Committee.

Bob Zellner concluded his recollection:

The symbol became smoother and more stylized with age. When I wrote about this… I commented on the irony that Dottie, a white northern woman, [was one of the artists involved in drawing] the first black panther.

Even after the panther entered the Bay Area, it remained restless. Although it was used widely in its current form, it was also modified depending on graphic needs. Movement graphic scholar colleague Lisbet Tellefsen and I had noticed that several “official” panthers were… different, and began to track down the artist.

That would be Lisa Lyons. In a 2016 interview, Lisa explained her role:

We chose the Lowndes County Freedom Organization panther for Black Power Day materials since it was already widely recognized nationally as a symbol of black power by the fall of 1966. My husband Kit and I were active members of the Independent Socialist Club in Berkeley, and we also made use of the panther symbol in ISC publications at the time of our work on the 1966 SDS Black Power Day conference. For example, see the cover of an SDS position paper published by the ISC for distribution on Black Power Day and a later ISC leaflet we distributed in Berkeley in the immediate aftermath of the Panthers “inaugural” demonstration in Sacramento.

We used the standard panther in a variety of other ISC and Panther publications in 1966 and 1967. For example, a poster for an ISC/Black Panther Party rally in defense of the ghetto uprisings and a label used for cans for fund raising for the Panthers, and a variety of Panther-related buttons.

I did make various small modifications of the panther symbol from time to time, depending on the size of the publication, etc., (including inadvertently changing the number of claws at least once.).

From ’67 through ’69, we also published other cartoons and buttons that morphed the basic design in more substantial ways.

I thank these three women – Ruth Howard, Dorothy Zellner, and Lisa Lyons – for their heretofore untold role in creating one of the most powerful icons of community self-defense and empowerment of the 20th century.

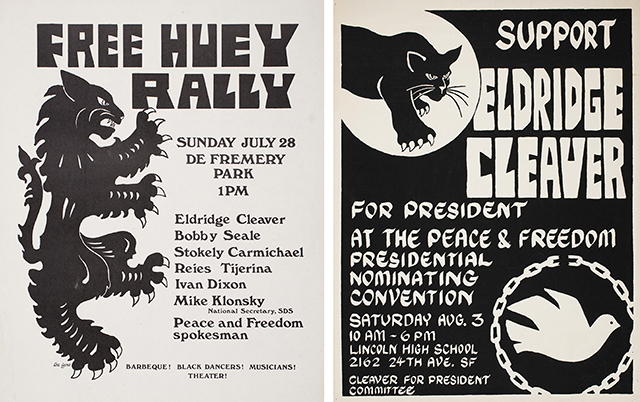

Images:

Detail, interior panel of brochure for the Lowndes County Freedom Organization, circa October, 1966; image courtesy H.K. Yuen Social Movement Archive collection

Flyer for SDS “Black Power and its Challenges” conference at UC Berkeley, October 29, 1966; image courtesy H.K. Yuen Social Movement Archive collection

Poster for SDS “Black Power and its Challenges” conference at UC Berkeley, October 29, 1966; poster courtesy Lisbet Tellefsen collection, image by author.

Poster for rally for Eldridge Cleaver for President, San Francisco, August 3, 1968; Docs Populi digital archive

Free Huey Newton rally, Oakland, July 28. Poster courtesy Lisbet Tellefsen collection, image by author.

A version of this piece first appeared in Design Observer 01 Feb 2018

Saggio da San Frediano – Ben Tornato a San Francisco

By Peter Olney

On January 4 Christina and I returned from our 4 month epic adventure living in Florence and traveling all over the Italian Republic and managing side trips to Dubai and Greece! It is good to be home and back with our son Nelson Perez-Olney and both our extended families, comrades and friends. I told my Italian friends that the reason we were going home was to work on flipping the House of Representatives to the Democrats in November of 2018. Only then, I promised, could we return to Italy. We have work to do…but we can do it!

What kind of baggage political and other wise did I bring home from Italy? In this case the metaphor works. Christina and I traveled to Italy with one checked bag and one carry on apiece. After four months in Italy we sent home 14 boxes packed with mostly clothes, books and written publications and magazines! WOW! “Dio Buono” as the Italians might say politely! I still can’t explain this phenomenon, but the act of mailing the boxes using the Poste Italiane and the act of receiving the boxes via USPS deserves a telling.

Da Firenze

In anticipation of our return I began the process of interacting with Poste Italiane on December 11 by toting 2 full and big cardboard boxes from our house in Piazza Tasso to Via Lorenzo Bardolini near the Arno in our neighborhood of San Frediano. The post office is right next to a silk factory – “Il Setificio Antico Fiorentino”–, which is still in operation and has its origins in the Renaissance.

Outside the Poste Italiane there is an automated machine (what we would call an ATM) but it is a Postamat for Italians to access at all hours for cash, credit and bill pay among other services.This is because the Poste Italiane, a state enterprise with 40 percent private investment offers a myriad of services to the Italian public: banking, insurance, bill paying, credit cards, telephones and of course mail. Therefore when you enter the lobby you pull a number for the service that you want: Spedizioni, Finanzi, Pagamenti etc. Then when your number is up over the appropriate “Sportello” you begin your interaction with a postal clerk. On December 11 I interacted with Clara at Sportello #1. She was very kind in explaining to me that there were no proper forms available for international delivery and that they were on order. I would have to come back the next day when the “schede” arrived. She did explain that even on a slow boat (that would take 30 plus days) the cost was going to be considerable: 5-10 Kilos – 60 Euros, 10-15 K’s 75 and 15-20 – 90 Euros. A both heartening but disturbing posted notice in the lobby explained that Poste Italiane might be subject to strike actions between December 15th and January 5th. Good to see the Italian labor movement flexing its muscles, but not at a good time for “viaggiatore Pietro”!

I returned the next day and “le schede” had arrived and I dutifully filled them out. This time Laura waited on me and sent the packages on without any hitches. I have learned not to create hitches by questioning any of the procedures at Poste Italiane. If the clerk decided to label a box incorrectly as to weight and number of items on the manifest I ask no questions. A year ago the packages had arrived safely in the USA from Rome, and I knew the same would be true for this mailing. One interesting sidelight was that the number of “schede” that Laura had would not be sufficient for my estimated 12 boxes. When I asked for more they suggested that I go to another office. So off I went to the Via Senese office outside the Porta Romana, still in our neighborhood. I got the “schede” and was able to mail my boxes out with Laura and Clara! No strikes occurred, and in fact when I asked the employees about a strike, they claimed no knowledge of such an action and asked all their colleagues who also said they knew nothing. My Italian was fine for everything. The only challenge was when my hearing aid died, and I was left having trouble distinguishing words; a nightmare when speaking a foreign language.

San Francisco

The boxes started arriving on January 16th at our home in the Sunset District of San Francisco. This was about a month out from our first mailing and the predicted time via container ship. If I happened not to be at home when the driver from USPS showed up I went to the Taraval Station to pick up the packages.

This station is one of several stations serving the Outer Sunset, a neighborhood that is 60% Asian. The clerks are almost all native Chinese speakers. The service is excellent, and they explained the situation with my boxes simply and coherently in heavily accented English. However when the clerks spoke amongst each other I was in a foreign land, lost because I couldn’t speak Cantonese. So the tale of two post offices is that in Italy I understood the primary language, in my own post office I did not. I celebrate this and only wish that I could speak Cantonese because I can imagine the world that would open up to me. In fact the one neighborhood in San Francisco that reminds me of our Italian neighborhood for street life and banter is San Francisco’s Chinatown. People milling about in public markets and cafes speaking with friends and family…Seems like San Frediano except in Cantonese not Fiorentino.

Both post offices are often reviled and criticized by their citizens. I happen to be a big defender of the PO in this country given the stresses and duties placed upon them, and in terms of delivery times they are far more reliable than Poste Italiane.

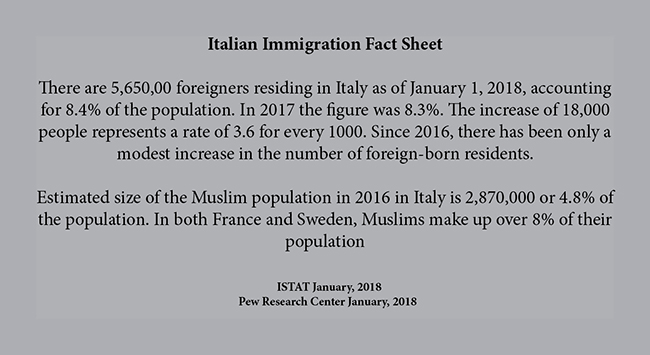

I can’t imagine however finding a post office in Italy where the principal language is anything but Italian. Italy relative to the United States is a very homogenous country. The immigrant population (born outside Italy) is estimated to be 14 %. Yet and still the hot topic in Italy leading up to the national election on March 4 is immigration, an issue that the Right is playing very unashamedly ala Donald Trump.

My next installment will be on Italian immigration issues and what if any lessons they hold for our battles here in the USA. We are bringing our baggage home……

A presto.

THE RICH AND THOSE TAX BRACKETS

By John Bowman

To get right to the point: Why should “The Rich” pay so much in taxes? In all the recent arguments about the provisions of the new tax law, no one ever makes a reasoned case for the high brackets.

Those protesting that they’re too high simply argue that any taxes are effectively “taking money I’ve earned.” Those claiming the percentages are if anything too low simply state “The Rich” deserve to be heavily taxed. Neither side provides a rationale for its position. I propose to try to do so.

I intend to define “The Rich” in terms of those brackets and I’m going to argue that at the very least the top three brackets comprise – “The Rich”: 32% for taxable income of $157,500-$200,000, 35% for taxable income $200,000-$500,000 and 37% for $500,000 taxable income and over.

For starters, most Americans—or so I contend—do not understand that it is only the income at and above each bracket that is taxed at that percentage. That is, no one pays 32%, let alone 37%, on their entire income. In fact, “The Rich’s” income up to $157,500 is taxed only at 24%. Moreover, all these percentages refer to taxable income—what’s left after all legitimate expenses, itemized deductions and other questionable deductions have been taken.

And there’s the rub. The higher one’s income, the greater the certainty that people will have used accountants and tax lawyers to exploit every possible provision and/or loophole to bring their taxable income down to the minimum. (And by the way, deducting the pay to these individuals as an expense.) Don’t for a minute imagine that when you read of someone being paid $1 million a year that he or she is paying anywhere near 37% of that sum in taxes. In fact, many of the richest people, like many of the largest corporations, pay little or even no income taxes.

Still, I’m willing to accept that this leaves a relatively small percentage of Americans paying the large percentage of the country’s income taxes. So let’s return to their complaint (and that of most Libertarians and Republicans): “They’re taking money I’ve earned!”

But really, can anyone honestly claim that—in an America in which hundreds of millions of people work hard for 35-40 hours a week just to make, say $35,000 a year (let alone $20,000)—can people sitting at desks and manipulating numbers really be said to be “earning” such sums as $500,000? Even a university president or college basketball coach who is paid $500,000—have they “earned” that when the janitors in their buildings work 35 hours for 50 weeks a year to earn $35,000?

Which brings me to my rationale for why “The Rich” not only should, but actually deserve to pay those large taxes. I contend that there is no one earning $157,500 (for that matter, $57,500—but more about that later)—no one in the top three tax brackets who does not depend greatly on large numbers of Americans who earn, say, $35,000 a year or less. People who live from paycheck to paycheck, who can’t come up with even $500 for a sudden emergency, whose net worth doesn’t even come close to $10,000.

Where to start? Virtually all the food eaten by everyone depends on people who earn pitifully low wages—often below minimum and sometimes even cheated out of pay. Not just the primary laborers in the fields and food processing plants but most workers along the chain that brings food to all our tables. Yes, the great chefs and maitre’ds, and sommeliers in “The Rich’s” favorite restaurants are well paid, but much of the staff earns minimum wages. As do store clerks and delivery personnel, and just about everyone else in the food chain.

As do most employees in the other two basic survival sectors—clothing and housing. Again, “The Rich” can tell us of the well-paid dress designers and tailors they frequent but these are only the visible top of the clothing pyramid. From the makers to the sellers of clothing in America, the vast majority of workers are low paid.

Then there is housing. Yes, the owners of grand residences and of the large construction firms and the strongly unionized trades—electricians, plumbers, carpenter etc.—are well compensated, but once more, large numbers of poorly paid Americans toil to build and maintain both residential and commercial buildings.

How about that janitor in your building? And the doormen? Then there’s the cleaning lady. Maybe a maid. Probably a nanny. Those taxi drivers. The daycare workers. The school teachers.

Do you pay a small fortune to your private schools? Yes, but the staff—including teachers—probably works for less than in the public sector because they, too, value the privileged environment you want for your children.

The children to whom you want to leave your “hard earned” savings. Thus, in addition to complaining about the high tax brackets, you object to the ”death tax.”

My point is simple: “The Rich”—and ALL of us who have been paid well over the nation’s median income—have greatly profited from all those low-paid hard-working people. And note that I have not even referred to the millions of “illegals” in America—working with sub-minimum wages and contributing to Social Security that they cannot receive–—let alone the billions of low-paid people around the world who also support our lifestyles. This is why I think there is nothing unfair about the high tax brackets. They simply are a way for “The Rich” to give back a bit of the money they were paid—not earned—at the expense of the underpaid.

So why not expect—demand!–that everyone with an income, say, over the median household (now about $59,000) pay taxes to support Medicaid and CHIP and food stamps and subsidized housing and school lunches and all such programs that basically return some of the money we owe the recipients for working for us at low wages.

Fighting “Right to Work” in Missouri again: 40 years later!

By Sonny Costa

The Forum is particularly proud to run an article on the Missouri Right to Work fight written by Sonny Costa out of Heat and Frost Insulators Association Local 1 in St Louis. As many of our readers know The Forum is named after Jeff Stansbury, a longtime labor and political activist. In his capacity as a reporter for the United Autoworkers’ magazine “Solidarity”, Jeff covered the anti RTW fight in Missouri 40 years ago. In an article published in Solidarity in 1978 soon after the defeat of RTW, Jeff said: “How did the New Right lose? The keys to its defeat is found in the coalition organized and led by workers, which included small farmers, students, environmentalists, who saw they had as a mutual interest the struggle against “right-to-work”. The pivotal force was the rank and file worker. Since the organizing days of the 1930’s, Missouri had not seen the outpouring of working class (activities)…that it saw this fall” Maybe history will be repeating itself in Missouri this November.

On September 4th 1978 I remember my sister and I sitting on a curb and my father, a proud member of the Heat and Frost Insulators local in St. Louis, handed us a black shirt with white letters that read “RIPOFF”. “Right to Work is a RIPOFF” was the slogan used by labor leaders and rank and file union members in Missouri during the campaign against Constitutional Amendment No. 23, the GOP’s first attempt to pass a Right to Work law in Missouri 40 years ago. On November 7th 1978, Constitutional Amendment No. 23 was soundly defeated by a three to one margin, marking an important victory for the labor movement across the country.

Since 1978 I have many memories of the Labor Day parade. Walking with my mother, a now retired member of the Communications Workers Union and my father as a child. Walking with my brothers and sisters as a member of the Heat and Frost insulators. Walking with my wife and children. And most recently I have marched as part of the current Anti-Right to Work movement.

The 2016 elections in Missouri went like the rest of the country. The GOP gained a super majority in both the house and the senate. They won all the open seats except the state auditor. The most damaging news for union members in Missouri came when newcomer and Republican Eric Grietens beat Chris Koster for the Governors seat. As Governor his first act was to fast track a Right to Work bill through the legislature. On February 6th he signed SB 19 making Missouri the 28th Right to Work State in the country effective August 28th. That same day Mike Louis, head of the Missouri AFL-CIO and Rod Chapel of the Missouri NAACP filed a petition initiative calling for a citizen’s veto of SB 19 to be placed on the November 2018 ballot.

In Missouri for a petition initiative to be certified you must collect five percent of the votes cast in the last governor’s election in six of the eight congressional districts. With the numbers we were given that meant we needed 100,126 signatures total to qualify the petition. In March Mike Louis laid out the plan for us: train a few members from each union on how to properly gather signatures. Then use them to train that union’s members. From there we wanted to gather signatures from each member’s family and friends. The next step was to go to public gatherings such as County Fairs, 4th of July celebrations and high traffic areas like malls.

On April 9th we began training and collecting signatures. Everyone was on-board and ready to fight. As we started gathering signatures, the support we were receiving from people who did not belong to a union was overwhelming. These were the people who understood that weakening unions is a detriment to everyone. Stripping a union’s ability to collectively bargain effectively would mean stagnant pay and weaker benefits for everyone not just union members. These people understood that without unions, pensions would be weakened and overtime pay would be lessened. They know that to keep their wages high union wages have to stay high. They know that stronger unions help grow the economy. Stronger unions help put money back into local stores and restaurants. Union members buy American made products and help not only the local economy but also the nation’s. Stronger unions help strengthen the backbone of the middle class.

Through the summer of 2017 the working-class people of Missouri stood up and fought back against billionaires named Koch and “Americans for Prosperity”. They stood up against multi-millionaires named Humphries, Sinquefield and Hoberock. We stood up and fought back against the people who had poured millions of dollars into the coffers of politicians to get their way in the implementation of anti-worker legislation. We stood up and showed the “1 percent” we were done being attacked and not fighting back.

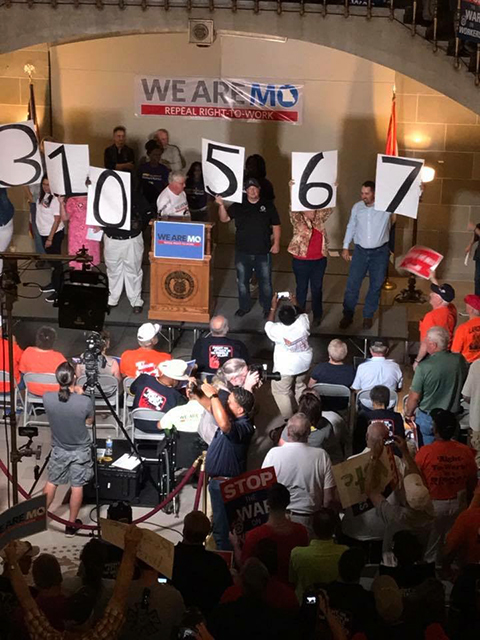

On August 18th 10,000 Missouri citizens filled the Capitol Building in Jefferson City to show the GOP led House and Senate that we were ready for a fight by turning in 310,567 signatures to repeal SB 19. This was more than triple the amount needed, and we qualified a petition in all eight congressional districts for the first time in the state’s history. Also we delayed its effective date until after the people vote on the initiative on November 6th 2018.

The September 4th 2017, Labor Day parade in St. Louis had a special feeling as just sixteen days before we had landed the first significant blow in this new fight against Right to Work. We have made this a promise to those who fought before us that we are ready to pick up where my father and his union brothers and sisters left off forty years ago.

Saggio da San Frediano #11: i’Bandito, or how il Trippaio Fiorentino stole my heart

By Christina Perez

“I had been hearing contradictory stories from local Florentines about lampredotto regarding its taste, texture, quality, cleanliness, and even the people who bought it and made it!”

In Southern California, El Monte to be exact, I grew up eating with abandon hot, spicy menudo, tripe soup. My dad, David E. Perez, had the well- deserved reputation in our large extended family as being perhaps the best menudo “cocinero” in our menudo-loving brood. And for good reason. Dad was a perfectionist when it came to preparing this popular Mexican dish. As with any great cook, his process started with buying the best ingredients from the Mexican butcher: clean honeycombed, or flat chambers of the cow’s gut, chunky marrow bones for added flavor, dry but fragrant oregano, hominy corn, yellow onion, and hot red chilies which produced the spicy sauce that made his menudo blood red.

The next part of the process is what Dad said made his menudo the “best.” The cubed white pieces were cleaned and re-cleaned, and soaked in water and onions until he was satisfied that his manual scrubbing and soaking had removed all “organic” material from the bite-sized chunks. No matter the amount of cleaning, when menudo is cooking it has a signature aroma that takes over the environment; it is the gut cooking after all. You either like the fragrant touch or you don’t. But, like Dad, some of us at home got excited when he got into gear and created his hearty menudo masterpiece, smell and all! Dad didn’t need an excuse like “the cruda” (hangover) to make this meal, but a cold or rainy day might stir him into action. Within hours, large bowls around the dining room table, a set of relatives dropping in to partake, a stack of hot corn tortillas, fresh chopped onion, cilantro, dry oregano, lime, dry red chile peppers, and beer, “Orale”- lunch was served. And what a lunch it was!!!

So it was when Peter and I were driving home on the cold rainy strada from Piazzale Michaelangelo in Firenze with our friends Marinella and Franco that we all made a beeline to the nearest trippaio to chow down on the Florentine favorite, lampredotto, or the so-called “last stomach” of the cow. Up until that moment, I had not been able to wrap my head around the idea of eating this “delicacy” despite having grown up eating “guts” up to my ears, so to speak. In the months being in Italy, I had been hearing contradictory stories from local Florentines about lampredotto regarding its taste, texture, quality, cleanliness, and even the people who bought it and made it! Not an anti-immigrant statement, but a not- so-subtle dig at families with limited means who could least afford the best cuts of meat. I think what felt like uppidity and snobby attitudes finally turned my head “ma dai”, or “come on!” In an instant I realized, lampredotto and menudo are like sorella e fratello (sister and brother) along the stomach chain- che vuoi che sia”, what’s the big deal? The biggest difference is that lampredotto meat is darker than menudo and it is the last stomach of the cow, or as put by our food guide a year ago “the last stomach before air escapes the cow’s body.” You get the picture.

Like menudo, lampredotto, requires focused scrubbing and soaking before being boiled to a tender consistency and chopped much like the tender, juicy pastrami that Americans have grown to love. i’Bandito, the trippaio at Piazza Pier Vettori in the Zona Ponte alla Vittoria did not disappoint. An eclectic tripperia, i’Bandito also made hamburgers and paninos. The menu featured specialties with names well known to Americans – “Billy the Kid”, “Jesse James” and “Calamity Jane”. We chose to wolf down the “Davy Crockett”, which was a hollowed-out panino (a fist-sized crunchy bun) ladled with hot, juicy lampredotto brood (juice) followed by mounds of hot chopped lampredotto meat, fragrant green salsa picante, optional greens, sal and pepe, and a bichiere (glass) di vino rosso to top it off – bravissimo! The large palm-size treat took about five bites to finish off, and each bite-ful was tender, spicy, hot, juicy and molto delicioso!

As I watched the trippaio prepare lampredotto for other customers, I was reminded of the cuts of meat my eyes feasted on when shopping with my Dad for tripe at his local butcher. Like the Mercato Centrale in Firenze, Dad’s butcher had the tripe and the necessary ingredients and required contorno for the finished product close at hand. Looking back however, Dad’s local butcher was poverty stricken in comparison to the variety of body parts sold by butchers at the large Mercato Centrale. For example, in Firenze expect to find every imaginable part of the animal’s body sold, not least: whole chickens and rabbits with heads, spleen, pancreas, kidneys, brains, eyes, ears, hoofs, heads, thymus, lymph nodes; all the stomachs and intestines of the cow, and not to be left out, the bull’s penis! Shopping in Firenze markets has sensitized me to how prudish the American “diet” has allowed itself to become in many parts of the U.S. (my own home included!).

Buon appetito!