Irma and Me: Notes From the Evac Zone

By Mike Miller

After thinking I was stuck in Miami until Monday, I made it out. Here’s the short take.

I awoke from my short sleep at about 12:30. Still a bit groggy, I headed for what looked to be the most comfortable restaurant that was still open. That was the Irish Pub where my Irish omelet was perfect. Given my plan to stay at the airport for the duration of my stay in Miami, I thought this was a good place to start: comfortable seats, CNN TV, good food, good service. One of the waiters even scoured the restaurant to find an electric power outlet so I could plug in and restore my computer battery. He even looked behind the TV screens. No luck. Oh well.

But around 2:00, it was clear they were shutting down. “Can I hang around here?” I asked. “No, sir, we’re closing” “I’ve got no place to go.” “What? You don’t have a place to stay, and you don’t have a fight?” “No, neither one.” “Let me ask.” That was a combination of my waiter and the manager, both of whom are Latinos—so they talked with one another in Spanish that was too rapid for me to do more than catch a word here-and-there. The manager checked with his boss, also in Spanish. “Sorry, sir, but you can’t stay. But let me see if I can make you some sandwiches.” That was encouraging. I figured my safari in the desert of Miami Airport might be well served with an occasional bite to eat. No deal. “The kitchen is closed.”

Down the hallway of Gate D, however, there was still a Hudson Magazine store open with various packaged goodies. I stocked up: two healthy packages, and my sweet tooth won out on the third.

“What the heck”, said I to myself, “I’m going back to AA customer service. Maybe something is breaking there.” Now, instead of last night’s crew of two counter staff, there were eight. And the line was shorter. And when I got to the counter, lo and behold there was one last flight to Dallas, and there were seats on it and a decent connecting flight to San Francisco. Turns out American Airlines made a last minute decision to put passengers on the flight that was taking their remaining staff out of Miami Airport. So, believe it or not, I’m on a plane with a number of pilots, flight attendants, ground crew, who knows who else from American, and a lucky umber of “civilian” passengers. Further believe it or not: there are at least a dozen empty seats on the plane. The decision must have been made at the last minute to let passengers aboard, and there weren’t that many of us left in the airport—at least at the customer service counter, and they weren’t broadcasting availability.

By 3:30, I was on the plane. But I’ve been here before. “Don’t count your chickens before they’re hatched,” says I to myself. To make matters more suspenseful, there were a couple of false starts: first, the doors were shut to the plane—you now the message, “attendants lock your doors and prepare for departure” (or something like that). They did, and they were belted in their seats when they got up and opened the doors. More passengers. Breathe a sigh of relief: people getting on is good; people getting off is bad! More waiting. Pilot announcements that explain: “due to the skeleton air control crew, planes are spaced with 20 miles between them.” Then, “the plane to your left isn’t leaving because it’s too large. But we’re o.k.” Whew! Who knows what “too large” has to do with departures, but I’m glad we’re small.

In the air: I think we took off in an easterly direction, then banked to the south, then headed west. In any case, the sky was beautiful. Puffy cumulus clouds look like marshmallows stacked in the sky. Below, an archipelago: I didn’t realize there were so many small islands of the coast of Florida. Below us, Miami is bathed in sun. Skyscrapers line the east coast, and there’s a lot of water in Miami itself. Who knows what it’s going to look like in 24 hours.

More stories from yesterday.

In the first line I waited on, the one with people who had dogs in kennels and baggage too large to take on board, a woman behind me was scheduled to depart for London in a couple of hours. Initially we were a trio in line having a conversation: a young woman who had a Chloe size dog in a kennel; the London-bound woman, probably in her 60s, and me. When the rate of movement in the line made it obvious she would miss her flight if she waited her turn, she asked us if we minded her moving ahead. It was fine with us. I watched her ask the same question to every couple of people in front of her; nobody objected. She inched up the line to the counter. The kindness of strangers; I’m sure she made the gate on time. I hope the plane left.

“Me First” people

At the gate where we got kicked off our 9:30 pm scheduled San Francisco departure flight, there were American Airlines attendants answering questions from people in their order in the line. Some people thought they deserved special treatment: they looked young and healthy to me, so neither age nor illness appeared to be an issue. But there they were pushing their way to the front. The AA people were firm: “we’re talking with people in the order they are in line.” One guy wouldn’t take no for an answer: he went to the other counter attendant’s line, and pushed himself forward there. Same answer. A different answer might have precipitated a riot; I would have been a rioter! Same thing happened when the sheriff’s deputies arrived—the “me first” people trying to get ahead of the line.

I had my own feel-good story: after two hours in yesterday’s line, my 80-year old feet didn’t want to stand any more. I asked the young lady with the dog if she’d move my suitcase along while I found a place to sit for a while. “Of course,” she replied.

I’m my brother’s and sister’s keeper people.

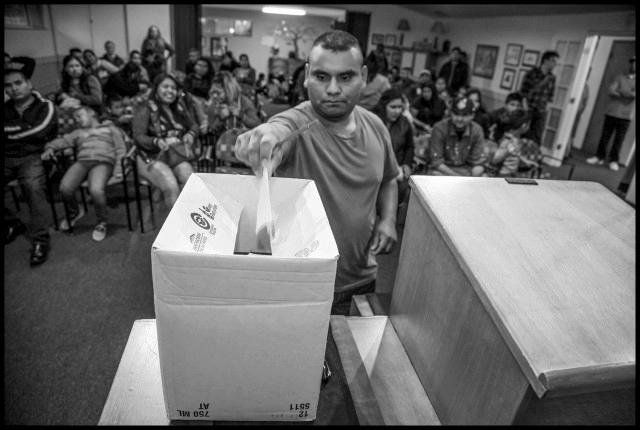

This was told to me by one of the women in today’s line about her experience in the same line yesterday. An older man was desperately looking for his Alzheimer-ill wife who had wandered off while he was dealing with a ticket agent. A scouting party was pulled together, but turned out not to be needed. A young man encountered her at a gate where he had just won the lotto (a drawing of the few available seats for the 50-per-plane standby travelers. (Some people scheduled to be on planes couldn’t get to the airport or for some other reason were staying in Miami). He brought the missing-wife with him to the customer service counter. Somehow it turned out that if he sacrificed his ticket, the couple could get on a flight. I never did figure out how that worked, and maybe it was an airport legend already being born, or I got the details wrong. Anyway, it was a nice feel-good story.

Talented people

In addition to the two people at the counter last night, AA had a roving agent who moved down the line to answer “quick questions”. Nobody had any of those, they all wanted his time. This guy was extraordinary, and obviously fit for his assignment. No story was too insignificant for his sympathy. No detail was too small for his attention. No complaint was without merit. And no matter what the story, the answer turned out to be the same: there are no more seats; every plane has a wait-list; you won’t get any flight out of Dallas before Monday. Go to a shelter. He was made for the job.

There were lots of people like that: flight attendants, ground crew, counter personnel, waiters and waitresses, hotel staff. A lot of people helped make the best of a bad situation.

Today’s line at Customer Service (“Gate D-37” is now indelibly imprinted in my mind) was a totally different story from yesterday’s chaos, frustration and anger. One of the people in the line told me that there was a near-riot here late last night because of the snail’s pace of the line, due to the presence of only two agents at the counter. Today there were eight. And there were fewer people in line. And lo and behold, when I got to the counter there was a seat—the one I’m now sitting in as we head to Dallas!

Ruminations

Everyday people. Stress brings out the best and worst in people. I saw dozens of airport workers stretch to make things work for beleaguered passengers: the waiter and manager at the Irish Pub; the counter people who were infinitely patient with some customers who actually yelled at them; the pilot of this plane who came back to the economy section where I’m sitting and invited a man with his young son to take a look-see in the cockpit as we waited for stragglers to board the plane; a flight attendant on this flight volunteered to work today to make things easier on passengers and fellow staffers; an electric jitney driver re-configured the luggage he was carrying so I could squeeze on his cart for the extra-long trip from one “D” gate to another. (Dallas Airport doesn’t have moving walkways; there’s a skyway that operates overhead, but I wasn’t sure it was working so walked most of the time.)

Be persistent. Be skeptical. Hope for luck

Had I not returned to the customer service line for a fourth try, I would never have gotten on this flight. Beside a general ornery character trait that arises in these circumstances, I also thought about institutional dynamics. AA didn’t want a repeat of the scandal in Chicago when a United staffer dragged a doctor, who turned out to be Chinese which added the dimension of race, from a plane—all on living cell phone video! Not very good for the bottom line! My thinking about that bottom line told me that by today the AA higher-ups who thought about profits and had a longer term view would have passed the word down: no egg on our faces! I think that’s why there were so many extra people at the ticket counter today, even with far fewer people in the line.

And I had a little bit of luck!

Race

In the line today, I was between two Jamaican women who let me in their conversation. The younger of them was traveling with her older aunt who came to Miami for some medical treatment. Now they were having difficulty getting home. The older one was “going home” after a number of years living in either Georgia or Florida. “At home,” she said, “you can go anyplace on a bus or a jitney or in an inexpensive taxi or by foot. Here, everything is so far apart and it’s so hard to get from one place to another.” And the pace of life was better at home; and the people were friendlier.

As the conversation went on, the older woman said, “Do you notice almost all the people in the line are of darker skin; you don’t see fair-skinned people here.” “I’m pretty pale-faced,” I piped in. “I didn’t mean you,” she said. The younger one was skeptical. So was I. Then I looked at the line: of the 30-or-so people in it, I would estimate that at least 80% of them were black. Could this be? I still doubt it. But in today’s world, I could believe it, and surely I can understand how a black person would believe it.

W.E.B. DuBois had it right: “…the world problem of the 20th century is the problem of the color line…” Add the 21st. And don’t forget, he thought class was real important too. Were he alive today, he’d add gender.

Crippled programs syndrome

In our work together in my Mission Coalition organizing days, my friend Steve Waldhorn developed the “crippled programs syndrome” concept. He applied it to the inadequacies of federal programs that were underfunded, constrained by limiting guidelines, and legislatively designed so they wouldn’t compete with the private sector. Then, when beneficiaries and the broader public complained about the programs, the conservative, anti-government crowd used their inadequacy to argue that government doesn’t work. Remember Ronald Reagan’s, “government is not the solution; it is the problem”?

Applied to the airport situation, I found some parallels:

> TSA—the security agency—has a mandate to prevent terrorism. That, of course, is why we have to go through those horrible lines and screens before we get to our flight gate. Applied to this situation, TSA would not allow baggage that was already stowed to be removed and transferred to other planes via their owners without another screening. That made transfers for checked-luggage people impossible.

> Flight control was on skeleton-crew status because air controllers had earlier been sent home. That meant a slow-down for departures that, in turn, meant planes that might have flown couldn’t get to the tarmac, and the earlier flight I was on couldn’t take off!

> The passenger bill of rights was adopted by Congress because of a horrific incident some years back in which a plane full of travelers sat on a runway for hours before it finally either took off or discharged those on board (I don’t remember which). The result was an outcry from travelers that led to a provision that says an airline is liable for a fine of $35K per traveler if the plane holds you on board for three or more hours without departing. At least that’s what our pilot told us. So, of course, as the three-hour mark approached, the airline had an interest in getting us off the plane if it couldn’t get us in the air.

> Union contracts stipulate maximum hours for pilots to be in the cockpit—for very good safety reasons. Maybe the provision is also in flight attendant agreements as well—I don’t know. That turned out to be another reason for our plane heading back to the gate. “If we don’t leave in four minutes,” our pilot informed us, “we have to take you back to the gate because of contract provisions. We will have to be in the air too long.” “Give them an inch, and they’ll take a mile,” is the standard trade unionist’s response to a query about “a little flexibility”. There’s good reason for the argument.

Add all this together, and you get the mess we had at the Miami Airport. No doubt it would have been messy in any circumstances, but isn’t there a better way?

Radical decentralization and worker control: A better way?

Imagine the airport and airlines organized according to different principles and in different structures.

First of all, while operating in the black is important (and government subsidies could help keep an enterprise in the black if that served the common good/general welfare), the maximization of profit for absentee, concentrated and super-wealthy owners would not be determining decisions. Rather, workers, travelers, managers, airline hub communities, would own airlines and their support services with widely shared stocks.

Second, everybody is organized: customers, workers, communities all have capacity to act on their particular interests so that the general interest/common welfare doesn’t end up screwing anybody. Results are negotiated, not imposed.

Third, site structures have a great deal of autonomy to deal with both routine and extraordinary circumstances. Granted the exceptions noted above, the overall impression I had was of workers who wanted to serve and do a good job, and travelers who were generous in spirit and caring about others who might be facing special circumstances that required special attention. The older Jamaican lady in today’s line put it clearly: there should be recognition of special circumstances like age, health, necessity of getting to one’s destination for important work or health reasons, and so on. Lots of wisdom in that idea, but it implies trust in goodwill rather than reliance on rules. It implies a basic decency on the part of people if they don’t think they’re being suckers. If they had authority, I think those with good will would impose their wisdom on the “Me-First” people. Bullies shrink when faced with opposition that is bigger than they are.

Lord of the Flies?

When I was an undergraduate major in political science, we read the William Golding novel Lord of the Flies. A group of British youngsters, probably sixth graders, is stranded on an isolated island. They organize themselves for self-governance. It quickly declines into rule by the most brutish.

The book draws its philosophical premises from Thomas Hobbes’ Leviathan, in which life is “solitary, poore, nasty, brutish, and short.” There is a “warre of every man against every man…every man is Enemy of every man…” In this circumstance, men give up their freedom to be ruled by a monarch who imposes order on the disorderly. Hobbes is a critical philosopher in the history of conservatism.

I have a different view. The experience at Miami International Airport confirms it. Most people behave toward one another with decency and generosity when they think that’s the rule of the day. Only when they think that’s the way suckers behave do they resort to “me first.”

Heading down to Dallas

The pilot just announced arrival in ten minutes at Dallas. I’m packing up my computer. And I’m tired, so I’ll probably try to get this off at the Dallas Airport then take a nap before getting on my last flight of this trip.

Thanks all of you for your calls and messages. Nice to feel that support from family and friends!

Signing off from 10,000 feet.

Love,

Mike

PS. As my flight was descending into the Dallas Airport, I opened American Way, the AA flight magazine. There I found

“The people of Gander opened their homes to complete strangers,”

by pilot Beverly Bass who on 9/11 (the infamous one) flew her re-routed plane into this small Newfoundland village. She writes,

All told, about 7,000 passengers descended on the small Canadian town, nearly doubling its population…[T]he people on the ground were phenomenal. They delivered everything you could imagine throughout the night to the planes—diapers, formula, nicotine patches. They even filled 2,000 prescriptions for people who had packed their medicine in their checked bags.

When we got off the planes the next morning, tables of food lined the airport. The residents had stayed up all night cooking for us…Gander treated us like family, opening their homes and hearts. The flight crews stayed at hotels and schools, while the town converted churches and gyms into shelters for the passengers. When those filled, the people opened their homes to complete strangers and prepared thousands of meals for their guests.

PPS. It’s now about 11:00. As luck would have it, my Dallas-SFO flight is delayed by more than an hour. I’m really running out of gas. I know I’ll sleep on the plane. And I hope to see or hear from you all soon!

A More Perfect Union: How Labor Paved Way for Employer-Sponsored Health

By Lincoln Cushing

“Are you ship shape?” brochure about ILWU member health testing; 1951. Courtesy the ILWU archive, source of original unknown

And, cousin, I’m a union man” – Warren Zevon, “The Factory”, 1987

For more than 60 years, millions of Americans have gotten health care insurance through their work. Despite employment changes in the American economy, that sort of coverage is still enjoyed by more than half of the non-elderly population. But it wasn’t always that way. The hard work of organized labor was instrumental in making employer-sponsored health coverage a cornerstone of the human services safety net.

One benefit of the Progressive Era (1890s-1920s) was that large companies had to offer some form of industrial health care for workers. That made good business sense, since an injured worker isn’t very productive. But what happened if you broke your arm at home, or your kid got sick? You were at the mercy of fee-for-service medical care.

The first employer-sponsored health insurance is usually noted as 1929, when a group of Dallas teachers contracted with a hospital to cover inpatient services for a fixed annual premium.

The large federal construction projects during the Great Depression boosted support for expanded occupational health care. When industrialist Henry J. Kaiser got the contract to finish Grand Coulee Dam on the Columbia River in Washington in 1938, he also had to care for the thousands of workers in this remote worksite. He brought in Sidney Garfield, MD, who’d finished a successful industrial care program for the Colorado River Aqueduct project in Southern California. At the Mason City Hospital, Dr. Garfield worked with the unions to create one of the first family plans. It wasn’t insurance, it was health care offered for a prepaid amount. For 50 cents a week, workers (spouses and children cost a small amount more) were guaranteed medical care. That comprehensive, voluntary, and affordable health plan would be replicated during World War II for the 190,000 workers and their families in the Kaiser shipyards.

But this was an anomaly. Most American workers had nothing remotely close to a nonindustrial health care plan, even in the booming years after the war. That would change in 1948 and 1949 with two key labor law rulings.

In late September of 1946, the union at Pacific Coast Steel Co., Local 1069, in the San Francisco Bay Area selected the Permanente Health Plan (now called Kaiser Permanente) for its members and requested that employers provide payroll deductions for health care. Bethlehem Steel Company (which acquired Pacific Coast Steel in 1930) disputed their right to make such a decision. The union brought the issue to court, and won. The case of (BOLD) W. W. Cross & Company, Inc. v. United Steelworkers of America, CIO decided June 17, 1948, found the company had violated the National Labor Relations Act by refusing to negotiate on the terms of a group health and accident insurance plan.

That next year the U.S. Supreme Court ruled fringe benefits were an appropriate subject for collective bargaining under the NRLA after reviewing the case of Inland Steel Co. v. National Labor Relations Board, which established a precedent for union contracts regarding hospital and surgical benefits for employees and their dependents.

The Inland Steel case first emerged in late 1947, when the NLRB arranged hearings on two cases involving the CIO-Steelworkers. One case concerns Inland Steel company plant at Indiana Harbor, Ind., and Chicago Heights, Ill.; the other the W. W. Cross and company of East Jaffrey, N.H. In each case, NLRB trial examiners ruled that the employers were guilty of unfair labor practices in not consulting the Steelworkers, with which they held contracts, when they put insurance and pension plans into effect. The examiners in both cases directed the companies to bargain with the union on the type and extent of these plans.

On April 14, 1948, the NLRB ruled that employers are legally bound to bargain on pension plans with unions whose officers have signed Taft-Hartley affidavits that they are not Communists. The United Press news coverage noted:

“…the far-reaching decisions could put CIO President Philip Murray and some other high union officials in an awkward position. Murray and several other top labor leaders have refused to sign the non-Communist affidavits. But they are now engaged in a drive to win pension plans… The NLRB split 4-to-l on its verdict that pension plans are a form of wages, on which the Taft-Hartley act requires employers and unions to bargain collectively. The case involved the Inland Steel Co., and the CIO United Steelworkers, which Murray personally heads.”

The requirement for non-communist affidavits would remain through the Dwight D. Eisenhower administration; in the beginning of 1959 he even proposed extending it to employers. But in the fall of that year he signed the new Labor-Management Reporting and Disclosure Act (Landrum- Griffin Act) amending Taft-Hartley, which included a repeal of the affidavits.

Corporations followed the Inland Steel case closely. Charles E. Wilson, president of General Motors, was quoted as saying:

“The inclusion of health and welfare plans within the area of collective bargaining can only create new and unexplored areas of industrial disputes, difficult —if not impossible—to solve.”

Inland Steel appealed, but on September 23, 1948, the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed the NLRB position [in 170 f(2d)247] and ordered Inland Steel to bargain with the CIO union concerning retirement pension plans, a ruling that applied to all companies in interstate commerce where a union is the recognized bargaining agent of the workers. In 1949 the U.S. Supreme Court declined to review the decision. Although denial of a hearing does not formally constitute Supreme Court approval, the issue was effectively settled.

Labor and health policy scholar Marie Gottschalk noted this breakthrough in her 2000 book The Shadow Welfare State: Labor, Business, and the Politics of Health Care in the United States, the Inland Steel case introduced a period where “labor and management waged bitter battles over how much money employers should contribute to employee benefit plans, the items to include in these plans, and whether dependents should be covered.” But the door had been opened, and hundreds of thousands of working people benefited.

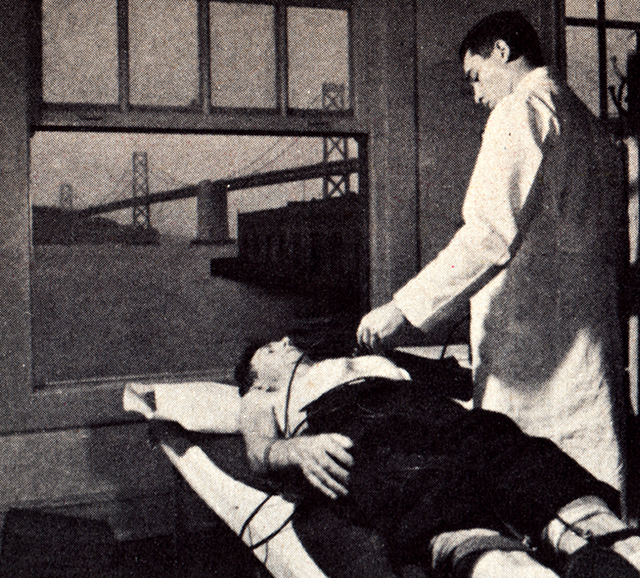

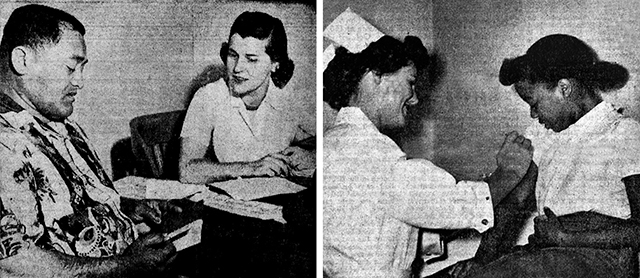

Left: “Anne Waybur of the ILWU Research Department interviewed more than 125 longshoremen, clerks, foremen and their wives in San Pedro, Calif., to find out what they think of the Permanente Health Plan coverage and service.” The Dispatcher, 1/5/1951. Right: Permanente pediatric clinic at 515 Market St, San Francisco – nurse giving Patricia Nisby, daughter of ILWU Local 10 member Wiley Nisby, a shot. ILWU Dispatcher, 1950-10-13. Detail from “Welfare is Porkchops”

In 1949 the International Longshore and Warehouse Union approached the Permanente Health Plan about covering their membership. Permanente and the ILWU had been in discussion since 1945, but the Inland Steel ruling made the leap possible. Permanente was attractive to the ILWU for its racially integrated facilities and labor-friendly record during the war.

The January 6, 1950, ILWU newspaper The Dispatcher announced the new Permanente Health Plan, and by year’s end, 90 percent of eligible members had signed up.

When the plan began, there was a big rush for treatment of such illnesses as hernias and hemorrhoids, conditions the men had suffered with and lived with for many years. They hadn’t been able to pay for medical care on their own. A March 10, 1950, article in The Dispatcher put it this way:

“The Welfare Plan is the greatest thing since the hiring hall.” That’s the opinion of D.N. (Lefty) Vaughn, Local 13 longshoreman, hospitalized here under Permanente. Vaughn told Local 13 visitors last week that if it wasn’t for the Welfare Plan he would have had to sell his home to pay for the major operation he’s getting for nothing through the Plan.

An editorial three weeks later further explained:

“Life can be beautiful if you’re healthy is the way the ad men put it. There’s no doubt they’ve got a point, though it’s oversimplified. Health is no fringe issue, not when you are required to make a choice between an operation which will allow you to go on working and living, and the home you must sell to pay for that operation. Longshoremen no longer have to make such choices. More than one home has been saved since the medical coverage section of the Welfare Plan became effective.”

The two rulings fundamentally shifted organized labor’s role in defending and expanding workers’ rights. Gottschalk further describes the impact:

“The myth of the consensus years of labor-management relations in the 1950s obscures how contested an issue benefits remained at the bargaining table. In 1949, health and welfare issues were central in 55 percent of all strikes; in the first half of 1950, 70 percent of all strikes were over these issues.”

While it’s true that the benefits of Inland Steel only applied to organized workers in larger industries, leaving out agricultural labor and smaller shops, it was a major step forward in building public expectations that medical care be affordable and accessible.

Thank you, organized labor – you not only brought the weekend to our regular work week, you brought us the employer-sponsored health plan. And on this particular Labor Day weekend, let’s remember and honor the gains made by unions.

Special thanks to ILWU archivist Robin Walker, who has put newspapers from 1932 to present online.

Theodore W. Allen’s Work On Centrality of Struggle Against White Supremacy Growing in Importance on 98th Anniversary of His Birth

By Dr. Jeffrey B. Perry

Theodore W. “Ted” Allen (1919-2005) was an anti-white supremacist, working class intellectual and activist. He developed his pioneering class struggle-based analysis of “white skin privilege” beginning in the mid-1960s; authored the seminal two-volume “The Invention of the White Race” in the 1990s; and consistently maintained that the struggle against white supremacy was central to efforts at radical social change in the United States. Born on August 23, 1919, in Indianapolis, Indiana, he grew up in Paintsville, Kentucky and Huntington, West Virginia (where he graduated from high school), and then went into the mines and became a United Mine Workers Local President. After hurting his back in the mines he moved to New York City and lived his last fifty-plus years in the Crown Heights section of Brooklyn.

The Invention of the White Race

Allen’s two-volume “The Invention of the White Race” (1994, 1997: Verso Books, new expanded edition 2012) with its focus on racial oppression and social control is one of the twentieth-century’s major contributions to historical understanding. It presents a full-scale challenge to what he refers to as “The Great White Assumption” — the unquestioning acceptance of the “white race” and “white” identity as skin color-based and natural attributes rather than as social and political constructions. Its thesis on the origin, nature, and maintenance of the “white race” and its understanding that slavery in the Anglo-American plantation colonies was capitalist and enslaved Black laborers were proletarians, contain the basis of a revolutionary approach to United States labor history.

On the back cover of the 1994 edition of Volume 1, subtitled “Racial Oppression and Social Control”, Allen boldly asserted “When the first Africans arrived in Virginia in 1619, there were no ‘white’ people there; nor, according to the colonial records, would there be for another sixty years.” That statement, based on 20-plus years of primary research in Virginia’s colonial records, reflected the fact that Allen found no instance of the official use of the word “white” as a token of social status prior to its appearance in a Virginia law passed in 1691. As he later explained, “Others living in the colony at that time were English; they had been English when they left England, and naturally they and their Virginia-born children were English, they were not ‘white.’ White identity had to be carefully taught, and it would be only after the passage of some six crucial decades” that the word “would appear as a synonym for European-American.”

In this context he offers his major thesis — that the “white race” was invented as a ruling class social control formation in response to labor solidarity as manifested in the latter (civil war) stages of Bacon’s Rebellion (1676-77). To this he adds two important corollaries: 1) the ruling elite deliberately instituted a system of racial privileges to define and maintain the “white race” and to implement a system of racial oppression, and 2) the consequence was not only ruinous to the interest of African Americans, it was also disastrous for European-American workers.

In Volume II, on “The Origin of Racial Oppression in Anglo-America”, Allen tells the story of the invention of the “white race” and the development of the system of racial oppression in the late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century Anglo-American plantation colonies. His primary focus is on the pattern-setting Virginia colony, and he pays special attention to the reduction of tenants and wage-laborers in the majority English labor force to chattel bond-servants in the 1620s. In so doing, he emphasizes that this was a qualitative break from the condition of laborers in England and from long established English labor law, that it was not a feudal carryover, that it was imposed under capitalism, and that it was an essential precondition of the emergence of the lifetime hereditary chattel bond-servitude imposed upon African-American laborers under the system of racial slavery.

Allen describes how, throughout much of the seventeenth century, the status of African-Americans was indeterminate (because it was still being fought out) and he details the similarity of conditions for African-American and European-American laborers and bond-servants. He also documents many significant instances of labor solidarity and unrest, especially during the 1660s and 1670s. Of great significance is his analysis of the civil war stage of Bacon’s Rebellion when thousands of laboring people took up arms against the ruling plantation elite, the capital (Jamestown) was burned to the ground, rebels controlled 6/7 of the Virginia colony, and Afro- and Euro-American bond-servants fought side-by-side demanding an end to their bondage.

It was in the period after Bacon’s Rebellion that the “white race” was invented as a ruling-class social control formation. Allen describes systematic ruling-class policies, which conferred “white race” privileges on European-Americans while imposing harsher disabilities on African-Americans resulting in a system of racial slavery, a form of racial oppression that also imposed severe racial proscriptions on free African-Americans. He emphasizes that when free African-Americans were deprived of their long-held right to vote in Virginia and Governor William Gooch explained in 1735 that the Virginia Assembly had decided upon this curtailment of the franchise in order “to fix a perpetual Brand upon Free Negros & Mulattos,” it was not an “unthinking decision.” Rather, it was a deliberate act by the plantation bourgeoisie and was a conscious decision in the process of establishing a system of racial oppression, even though it entailed repealing an electoral principle that had existed in Virginia for more than a century.

Key to understanding the virulent racial oppression that develops in Virginia, Allen argues, is the formation of the intermediate social control buffer stratum, which serves the interests of the ruling class. In Virginia, any persons of discernible non-European ancestry after Bacon’s Rebellion were denied a role in the social control buffer group, the bulk of which was made up of laboring-class “whites.” In the Anglo-Caribbean, by contrast, under a similar Anglo ruling elite, “mulattos” were included in the social control stratum and were promoted into middle-class status. This difference was rooted in a number of social control-related factors, one of the most important of which was that in the Anglo-Caribbean there were “too few” poor and laboring-class Europeans to embody an adequate petit bourgeoisie, while in the continental colonies there were ‘’too many’’ to be accommodated in the ranks of that class.

In “The Invention of the White Race” Allen challenges what he considers to be two main ideological props of white supremacy — the argument that “racism” is innate (and it is therefore useless to challenge it) and the argument that European-American workers “benefit” from “white race” privileges and white supremacy (and that it is therefore not in their interest to oppose them). These two arguments, opposed by Allen, are related to two master historical narratives rooted in writings on the colonial period. The first argument is associated with the “unthinking decision” explanation for the development of racial slavery offered by historian Winthrop D. Jordan in his influential “White Over Black: American Attitudes Toward the Negro, 1550-1812”. The second argument is associated with historian Edmund S. Morgan’s influential “American Slavery, American Freedom: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia”, which maintains that in Virginia, as slavery developed in the eighteenth century, “there were too few free poor [European-Americans] on hand to matter.” Allen points out that what Morgan said about “too few” free poor was true in the eighteenth century Anglo-Caribbean, but not in Virginia.

“White race” privilege

The article “The Developing Conjuncture and Some Insights From Hubert Harrison and Theodore W. Allen on the Centrality of the Fight Against White Supremacy” (Cultural Logic, 2010) describes key components of Allen’s analysis of “white race” privilege. The article explains that as he developed the “white race” privilege concept, Allen emphasized that these privileges were a “poison bait” (like a shot of “heroin”) and he explained that they “do not permit” the masses of European American workers nor their children “to escape” from that class. “It is not that the ordinary white worker gets more than he must have to support himself,” but “the Black worker gets less than the white worker.” By, thus “inducing, reinforcing and perpetuating racist attitudes on the part of the white workers, the present-day power masters get the political support of the rank-and-file of the white workers in critical situations, and without having to share with them their super profits in the slightest measure.”

As one example, to support his position, Allen provided statistics showing that in the South where race privilege “has always been most emphasized . . . the white workers have fared worse than the white workers in the rest of the country.”

Probing more deeply, Allen offered additional important insights into why these race privileges are conferred by the ruling class. He pointed out that “the ideology of white racism” is “not appropriate to the white workers” because it is “contrary to their class interests.” Because of this “the bourgeoisie could not long have maintained this ideological influence over the white proletarians by mere racist ideology.” Under these circumstances white supremacist thought is “given a material basis in the form of the deliberately contrived system of race privileges for white workers.” Thus, writes Allen, “history has shown that the white-skin privilege does not serve the real interests of the white workers, it also shows that the concomitant racist ideology has blinded them to that fact.”

Allen added, “the white supremacist system that had originally been designed in around 1700 by the plantation bourgeoisie to protect the base, the chattel bond labor relation of production” also served “as a part of the ‘legal and political’ superstructure of the United States government that, until the Civil War, was dominated by the slaveholders with the complicity of the majority of the European-American workers.” Then, after emancipation, “the industrial and financial bourgeoisie found that it could be serviceable to their program of social control, anachronistic as it was, and incorporated it into their own ‘legal and political’ superstructure.”

Allen felt that two essential points must be kept in mind. First, “the race-privilege policy is deliberate bourgeois class policy.” Second, “the race-privilege policy is, contrary to surface appearance, contrary to the interests, short range as well as long range interests of not only the Black workers but of the white workers as well.” He repeatedly emphasized that “the day-to-day real interests” of the European-American worker “is not the white skin privileges, but in the development of an ever-expanding union of class conscious workers.” He emphasized, “‘Solidarity forever!’ means ‘Privileges never!'” He elsewhere pointed out, “The Wobblies [the Industrial Workers of the World] caught the essence of it in their slogan: ‘An injury to one is an injury to all.'”

Throughout his work Allen stresses that “the initiator and the ultimate guarantor of the white skin privileges of the white worker is not the white worker, but the white worker’s masters” and the masters do this because it is “an indispensable necessity for their continued class rule.” He describes how “an all-pervasive system of racial privileges was conferred on laboring-class European-Americans, rural and urban, exploited and insecure though they themselves were” and how “its threads, woven into the fabric of every aspect of daily life, of family, church, and state, have constituted the main historical guarantee of the rule of the ‘Titans,’ damping down anti-capitalist pressures, by making ‘race, and not class, the distinction in social life.'” That, “more than any other factor,” he argues, “has shaped the contours of American history — from the Constitutional Convention of 1787 to the Civil War, to the overthrow of Reconstruction, to the Populist Revolt of the 1890s, to the Great Depression, to the civil rights struggle and ‘white backlash’ of our own day.”

Strategy

Allen also addressed the issue of strategy for social change. He emphasized, “The most vulnerable point at which a decisive blow can be struck against bourgeois rule in the United States is white supremacy.” He considered “white supremacy” to be “both the keystone and the Achilles heel of U.S. bourgeois democracy.” Based on this analysis Allen maintained, “the first main strategic blow must be aimed at the most vulnerable point at which a decisive blow can be struck, namely, white supremacism.” This, he argued, was the conclusion to be drawn from a study of three great social crises in U.S. history – “the Civil War and Reconstruction, the Populist Revolt of the 1890s, and the Great Depression of the 1930s.” In each of these cases “the prospects for a stable broad front against capital has foundered on the shoals of white supremacism, most specifically on the corruption of the European-American workers by racial privilege.”

Groundbreaking Analysis Continues to Grow in Importance

Ted Allen died on January 19, 2005, and a memorial service was held for him at the Brooklyn Public Library where he had worked. Then on October 8, 2005, his ashes, as per his request, were spread in the York River (near West Point, Virginia) close to its convergence with the Pamunkey and Mattaponi Rivers – the location where the final armed holdouts, “Eighty Negroes and Twenty English,” refused to surrender in the last stages of Bacon’s Rebellion.

Allen’s historical work has profound implications for American History, African-American History, Labor History, Left History, American Studies, and “Whiteness” Studies and it offers important insights in the areas of Caribbean History, Irish History, and African Diaspora Studies. With its meticulous primary research, equalitarian motif, emphasis on the class struggle dimension of history, and groundbreaking analysis his work continues to grow in influence and importance.

Those interested in learning more of the work of Theodore W. Allen can see: 1) writings, audios, and videos by and about Theodore W. Allen; 2) comments from scholars and activists and Table of Contents for “The Invention of the White Race Vol. I: Racial Oppression and Social Control”; 3) comments from scholars and activists and Table of Contents on “The Invention of the White Race Vol. II: The Origin of Racial Oppression in Anglo-America” [Verso Books]; and “The Developing Conjuncture and Some Insights from Hubert Harrison and Theodore W. Allen on the Centrality of the Fight Against White Supremacy.”

Why Charlottesville?

By John Edwin Mason

Note: During and after last weekend’s terrorist attack on Charlottesville, I received dozens of texts and emails from friends. They were immensely comforting in a difficult time. But besides offering words of love and sympathy, my friends wanted to know Why? Why was Charlottesville the target of this assault? Why did Heather Heyer have to die?

Here’s what I wrote to a South African friend a couple of days after the attack. I’ve edited the letter to remove personal details about my friend.

It’s been awful. Physically, I’m fine, but I’m battered emotionally — we all are, I think. This is a city full of people who are in mourning, people whose sadness is inexpressible, people whose anger is suffocating.

I’ve been on the verge of tears, off and on, for the last couple of days. When I read an open letter from black University of Virginia alumni to incoming first-year students, my eyes got wet again. The alums told the class of 2021 that although “each of us… has experienced or witnessed racism and prejudice [at UVA]… racism, prejudice, and discrimination are not values honored by the University of Virginia.” Platitudes, of course. Aspirations, not facts. But we cling to them and want them to be true of our city and our university, especially now.

We’ve been terrorized. It’s as simple and as awful as that. Well organized, well armed bands of white supremacists, eventually totaling in the hundreds, invaded our city and our university, intending to spread terror. And they did. Some wore military-style clothing and carried assault rifles (legal here if not concealed). Others, dressed in white shirts and khakis, marched through the university’s grounds, on that Friday night, carrying torches (tiki torches from Lowe’s). Downtown on Saturday, they strutted and menaced. They shouted racist, sexist, Islamophobic, and anti-semitic slogans. They attacked counter-protesters. They killed Heather Heyer, a young activist. And they seriously injured many others.

Meanwhile, the heavy, militarized police presence that was supposed to keep the peace and protect the city utterly failed to do so. Piling tragedy upon tragedy, two Virginia State Police officers, who had been working as aerial observers, died late in the day when their helicopter crashed.

I don’t mean to say that all of this has left us cowering. It has not. Even during the white supremacists’ rally, the counter-protesters never left the streets. Clergy members and ordinary citizens attended protest meetings, interfaith prayer services, and outdoor vigils for the victims. Local members of Black Lives Matter led chants of “Whose Streets? Our Streets.” Anti-fa activists protected the clergy from white supremacist thugs.

But, still, we were terrorized, even if most people don’t want to use the word. We were reeling — anxious, angry, distracted, disoriented, and impossibly sad. To some degree, we still are. Just as we think we’re doing better, the monster in the White House finds a way to pour salt on our wounds.

On Sunday, the day after, the streets were still eerily quiet. People largely stayed close to home, close to family, church, and friends. Things began to seem more normal on Monday. You had to go to work, after all. In the evening, several hundred people — black and white, young and old — packed the auditorium at the Jefferson School African American Heritage Center to talk about where the city should go from here. More importantly, we wanted to gather as a community to assure ourselves and the world that we’re still here, and we haven’t been defeated. Solidarity.

Journalists have been calling and emailing. They all want to know — Why Charlottesville?

Short answer. White supremacists capitalized on the city’s decision to remove a statue of Confederate hero Robert E. Lee from a park in the center of the city.

Longer answer. The presence of the statue in a park that’s downtown Charlottesville’s most important gathering place has been an issue off and on for years. When the controversy came to a head in 2016, city council appointed a commission to make recommendations about the fate of the statue and a statue of Stonewall Jackson, another Confederate general. I was vice-chair. We were also charged with suggesting ways to tell a more inclusive and accurate public history of the city. That meant, in essence, finding ways to tell the story of people that public sculptures and markers ignored (or, in the case of Native Americans, depicted in defeat.)

Among other things, we recommended that the park in which the Lee statue stands should be renamed (it’s now Emancipation Park) and that the Lee statue should either be removed from the park or physically transformed to sap its visual power and open it up to reinterpretation. The statue, we said, was and is a symbol of both the myth of the Lost Cause, which glorifies the slaveholding South, and the triumphant white supremacy of the early-twentieth-century Jim Crow, when it was erected.

City council then voted to remove the damn thing. (The process has been delayed by a legal challenge, brought by people who want the statue to remain, untouched.)

I saw a headline the other day that said something like “Charlottesville Is Us.” Hell, yes. These last few days have held up a mirror to America.

When Jason Kessler, a local white nationalist blogger, called for a “Unite the Right” rally in Emancipation Park to protest the decision to remove the statue, he understood that many of the white supremacists know fuck-all about Lee and the Civil War. But he also saw that the statue was a symbol of white male supremacy around which a diverse constellation of racist, neo-Nazi, neo-Confederate, and white nationalist groups could coalesce. It was a clever ploy and an effective one.

Kessler is small potatoes. But his plans received a boost when Richard Spencer, a UVA graduate, who’s a celebrity in the world of white nationalism, joined the campaign. And it struck a chord nationwide.

The fact that Charlottesville is a small city with and even smaller black population also matters. After all, it’s hard to imagine similar terrorist attack happening in, say, New Orleans, which very publically got rid of its Confederate memorials last spring.

But there’s a second question that that’s even more to the point. Why Not Charlottesville?

I saw a headline the other day that said something like “Charlottesville Is Us.” Hell, yes. These last few days have held up a mirror to America. We’re a nation still defined by white male supremacy. In 2016, a majority of white voters — male and female — elected someone to the presidency who they knew is deeply and unapologetically racist and sexist, someone who demonstrated those truths time and again in the most grotesque ways imaginable. During his campaign and in office he has surrounded himself with people just like him.

Those people, and his enablers in Congress, help us see through the comfortable illusion that white supremacists are only the folks who burn crosses or carry tiki torches. Jeff Sessions and Paul Ryan might never have worn Klan hoods or shopped for torches at Lowe’s, but they’re doing the work of white supremacy every day of the year.

Fact is, Trump isn’t the aberration. Obama was.

DSA National Convention 25,000 and Counting

By Kurt Stand

“We will not achieve a democratic socialist society in the immediate future. We will not uproot sexism, nor will we achieve a full employment economy. Neither will we experience the creation of a viable black “nation within a nation.” What we all can dare hope for, and work for, are the beginnings of the process of change, Gramsci’s “war of position,” which will advance the material and social interests of the oppressed of all ethnic groups, sexes, races and cultures. We can change the world, only if we find the courage to challenge ourselves. We can change the world, only if we begin to overturn the patterns of our own history.” Manning Marable, 1981

”The challenge that faces the Left in the future – if it is to have a future – is to base itself on the knowledge of what collective action by human beings can mean, rather than on faith in the infallibility of either its dogma or its leaders. If I were allowed just one piece of advice to give a new generation as to how to sustain a life-long commitment, I would suggest the cultivation of those two essential virtues of a revolutionary, patience and irony.” Dorothy Healy, 1990

DSA’s phenomenal growth – from 6,000 to 25,000 in less than a year – was registered at the just concluded National Convention in Chicago. Over 700 Delegates took part in debates and discussions, August 5-7, that led to political resolutions and bylaw changes reflecting the perspectives of those newly joined. And it is not just membership growth – it is growth in political credibility and influence, growth as part of something much bigger. A sign of the seriousness of the change may be noted by the fact that there was no large outreach event with well-known speakers – a staple of past Conventions. The reason is, in part, because there was no need as DSA’s Convention was a public event in and of itself.

But rapid growth is no guarantee of long-term success and stability. SDS is the obvious example of an organization that experienced a massive increase in members at a pace that it could not assimilate and so soon collapsed in division and acrimony leaving a vacuum that was left unfilled. Other organizations suffered a similar fate, notably SNCC, the Black Panther Party, La Raza Unida. Drawing a slightly longer arc of rise and decline, we can note the same phenomena with the pre-World War 1 Socialist Party, with the Communist Party during the New Deal era – both of which faced repression shortly after reaching a peak of influence followed by losses from which neither ever fully recovered. Repression, however, is never the only, or even most significant, reason for decline or collapse. We live in a repressive system; a challenge to its power is bound to result in reaction. Rather more fundamental is finding a way to function politically on a larger stage of society, of maintaining and solidifying roots within working-class communities, acting within society’s institutions while maintaining a radical politics that contests for power. It is the challenge inherent in asserting what Michael Harrington referred to as “the left-wing of the possible,” bearing in mind that defining left-wing and ascertaining what is possible is never something fixed and is always subject to debate.

Certainly, the notion of the left and the sense of what is possible have been radicalized – as seen by Convention resolutions some of which speak to continuity with the past and some of which speak to substantive change. Examining Convention resolutions from the standpoint of what went before, can give a clue whether DSA will continue its growth in membership and influence.

Resolutions

Medicare for all – DSA reaffirmed a position supported by a majority who responded to a pre-Convention national survey by making a commitment to prioritize the demand: Medicare for All – with the specific inclusion of full access to women’s reproductive rights and to meet the needs of transgendered people. This reflected continuity; DSA had played a major role in organizing for single payer during the Clinton Administration health care debates and in the immediate aftermath of that initiative’s defeat. It was a commitment that grew out of traditional socialist values; failure to establish a national health care system in the aftermath of World War II was amongst the early signs that the forward progress of New Deal legislation had stopped – thereafter, support for national health remained a goal for progressives and labor. It also grew out of the role of socialist feminism in DSA for focus on health was not simply as a matter of national legislation, but was also about organizing to create women’s health centers, to defend abortion clinics, to act in solidarity with AIDS activists.

Yet, over time, the potential of the early 90s was lost. A divide grew within the social justice movement (mirrored in DSA) between local activism which dealt with the range of health justice issues in their immediate impact on individuals and advocates focused more on seeking an overall solution to the health care crisis. In consequence, left wing alternatives were politically marginalized despite having popular support, as was demonstrated during debates around Obama’s health reform proposals. The situation has now changed: the Republican attack on health care, in its very extremity, is emblematic of the dangers of the moment, the successful movement to defend Obama Care a sign of the possibilities if we act. At the same time, the demand for Health Care for all and defense of abortion rights draws a clear line of demarcation within the Democratic Party – and so enables DSA to put forward a distinctive independent perspective within the broader campaign, flowing naturally as a continuation of the politics around Sanders campaign.

Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) endorsement – in the midst of national and state legislative initiatives by both Republicans and Democrats to ban BDS compliance, this resolution came at a politically important time. In the past, defining a position around Israel and the Palestinians was a point of internal division, including during the negotiations between Democratic Socialist Organizing Committee (DSOC) and the New American Movement that led to the formation of DSA. The fact that the BDS resolution passed overwhelmingly is a sign of how much the organization has changed, and a sign of how much the political environment has changed. Israel’s repressive policies toward the Palestinians has become ever harsher and less constrained, while Israeli use of its “counter-terrorism” expertise to train and supply US police departments has made the domestic connection all the sharper.

The challenge for DSA is to concretize awareness of that connection into more general opposition to US overseas policy. Solidarity with Palestinians – and others who suffer from US-backed military power – is also a means of defending civil liberties at home, and a critical part any meaningful program to redirect resources away from war and toward meeting domestic needs. If the purpose of the statement was simply to establish a litmus test of radicalism, it will have no political meaning. If, however, it is integrated with DSA’s overall work and serve as a challenge to what was arguably the weakest aspect of Sanders campaign it will prove significant. That is the challenge still to be met.

Withdrawal from the Socialist International – The question to remain a member (observer) or withdraw was debated in locals throughout DSA in the months before the Convention. The level of interest on this was due to DSA’s longstanding SI membership, going back to the Socialist Party’s origins. Membership had been internally challenged in the past due to the SI’s anti-communism, complicity in the Cold War, and unambiguous support for Israel. But at the same time, positive reasons existed to remain. DSA served as a counterpoint to the late unlamented SDUSA (Social Democrats USA) another SI affiliate with Socialist Party roots. With close ties to the George Meany and Lane Kirkland leaderships of the AFL-CIO, SDUSA argued that their support for the war in Vietnam, the subversion of Salvador Allende’s government in Chile and CIA inspired coups there and elsewhere had the support of US workers and socialists; a position DSA always contested. Furthermore, Michael Manley in Jamaica, Julius Nyerere in Tanzania, were amongst several Third World leaders active in the SI as a vehicle to build support for progressive development policies (concretized in the Brandt-Manley Report). And finally, around the time of DSA’s formation, SI affiliates in Spain, Greece, just emerging from dictatorships, were developing policies that went beyond the limits of traditional Social Democracy. SI Women, in particular played an important role in advancing global women’s rights and DSA was part of that work.

But the moment passed, the parties of the Second International embraced wholeheartedly the politics of neoliberalism identified with Tony Blair in the UK, moving away from traditional support for universal social insurance and full employment. SI parties have given up the pretense of being parts of political movement, concerned instead with office holding and little else. So DSA’s membership had become an anachronism. What is lacking, however, is a clear sense of what a meaningful international policy might look like. Rather than identifying with the specificity of any single stream of left thinking abroad, DSA needs to find a way to develop more formal ties with the European Left Party, the Sao Paulo Forum in Latin America and other regional/global left bodies which in their respective attempts to build unity while embracing ideological heterogeneity are more akin to DSA’s multi-tendency nature.

Afro-Socialist Caucus formed and Black Youth Project 100’s Agenda endorsed – no weakness has proved to be a more critical in inhibiting DSA’s growth than its weakness in black, Latino and Asian communities. In particular, the lack of a base of African American members has undermined any attempt to root DSA amongst working people, given the centrality of racism and slavery to the development of US capitalism and to the formation of the working class. The creation of the Afro-Socialist Caucus is a hopeful sign that with the new spurt of membership, the possibility of overcoming that weakness may be at hand. The endorsement of the Black Youth Project 100’s Agenda, the support for reparations, the call for an end to mass incarceration, for prison abolition speaks to the understanding that change will not happen of itself. DSA’s program around universal demands for social and economic justice must be joined to demands that address the specific needs of dispossessed communities.

More though is required. An Afro-American Commission was established at DSA’s formation, together with the Asian-Pacific American, Latino and Native American Commissions, which jointly put out a journal, Third World Socialists. A small core of African-American activists (including Cornel West), together with the Anti-Racism Commission spurred the internal push within DSA to participate in the Rainbow Coalition and to support Jesse Jackson’s presidential campaigns. Yet although some outstanding local and national leaders continued to play a role in DSA’s organizational life, identified themselves with or joined DSA, DSA never came close to being sufficiently multi-racial in its membership or activist core. Part of the reason is that program and coalition building is insufficient – DSA must become more rooted in communities and workplaces if it is to develop an internal life that reflects the working-class in its full diversity. The steps taken in Chicago point in a positive direction; much more needs to be done.

Democratic Socialist Labor Commission created – The creation of the DSLC was the product of the initiative of mainly younger labor activists. As always, the challenge has been to engage in several arenas simultaneously: – to defend unions from attacks by business and government; to democratize unions and strengthen membership participation; to support development of a union agenda that connects workplace bargaining with a wider social justice agenda. Potential tensions exist in every aspect of doing so, because emphasis on one arena may come in conflict with emphasis on another arena. DSA’s success or failure in doing all three will go a long way toward informing how successful DSA is in its work overall.

Here too, a good deal can be learned from the experience of DSA’s Labor Commission in the 1980- 90s. The organization played a significant part in Central America/South Africa solidarity fights, in union reform movements including those of the Steelworkers and Teamsters, developed wide ranging strike support networks and took part in efforts within labor to develop progressive industrial policy with a focus on conversion from military to infrastructure production. DSA labor activism was part of the discontent that came to a head with John Sweeney’s successful reform candidacy for AFL-CIO President in 1995. The results were mixed: the AFL-CIO did change and change for the better – but the changes did not go far enough. The “organizing model of unionism” became dominant and while it opened up some pathways to activism, it closed others – especially as it evolved to be ever more staff-driven. Lack of attention to the inner-life of union locals undermined the independent base of the labor left. The half-victory, half defeat outcome made DSA’s future role unclear. The DSLC represents a positive step toward a new beginning. Future success will depend on remembering that networks of left union activists cannot replace those networks being fully a part of union life; without membership roots in workplaces, gains made will be fleeting.

What next?

Discussion took place at the Convention around other areas of engagement – immigrant rights, environmental justice, gentrification, and student debt amongst them. The socialist feminist commission with a national framework and local committees has been building a network to both change DSA’s internal dynamics and public program. Education and training programs to develop skills and understanding took place at the Convention – and are slated to continue. For all that DSA has changed with growth that is consistent – members work on national priorities, but locals develop their own focus based on assessment of local conditions. Doing so is a strength and, at the moment, crucial to build a sense of stability and trust.

But the big question that has yet to be defined has to do with electoral strategy. Over the past several months DSA has formed an electoral committee that has been engaged in supporting candidates – either DSA members or progressives open about DSA’s endorsement. Most of these have been running in Democratic primaries, challenging incumbent Democrats, and in that sense have been acting in a manner consistent with Our Revolution and other formations connected with of Sanders’ presidential campaigns – working to build an anti-corporate majority within the Democratic Party. This is in line with DSA’s orientation since its origins; nonetheless divisions exist as they always have between those who seek political realignment and a mass progressive movement through the Democratic Party, those who see progress as possible only through electoral action independent of the Democratic Party, and those who want to emphasis social movement activism over and above electoral work.

Though by no means co-extensive, these reflect underlying strategic differences. One approach is toward building coalitions – this was the traditional approach laid out by Michael Harrington in “Toward a Democratic Left”, and has the strength of seeking points of common ground across a wide spectrum of viewpoints. It has, however, the weakness of creating stop points which allows one perspective or another to be dropped for the “good” of the whole. Another perspective privileges independence: setting out a demand or group of demands and defining support or opposition to that as the basis of alliance. It is a perspective that allows for a clear enunciation of principles – “Medicare for All,” “No Concessions” – but suffers by drawing too sharp a line against potential allies. And both outlooks also tend to inhibit local action for fear in the one instance of disrupting a coalition, or in the other, of weakening the clear position being articulated. A third approach tends to favor local activism in which a variety of perspectives and approaches reinforce each other in a program that doesn’t require full agreement on any one point. The collective becomes the glue that might work with a union in one spot, a housing group in another, and local elected officials in a third. This allows maximum flexibility and integration in local movements, but it is typically unable to develop a sustained program able to overcome limitations or unpalatable compromises of local political power.

There is no iron wall between these and, at best, they are mutually reinforcing. When made absolute, however, they undermine each other. With growth comes greater visibility and influence – which makes maintaining this multiplicity of approaches all the more important and all the more difficult. It is a difficulty that will intensify over the coming years particularly as elections approach where the need to declare and engage will only grow. The divides over these perspectives are by no means generational – rather they reflect the imbalance of power between popular movements and the ruling circles of society and so constantly re-emerge and have to be constantly re-evaluated.

But a generational divide does exist in DSA and that has to do with a change of internal culture and language – smaller organizations with long histories develop informal procedures and a level of trust even within disagreement that comes out of people knowing each other. Newer members don’t participate in that, but have their own networks, their own modes of communication, their own frames of reference – and so between the two a lack of mutual understanding can emerge. The ability of DSA to build upon its successful conclusion, to resolve controversial questions, depends on being able to overcome that gap.

And that, in turn, depends upon using a broader measure to gauge internal divides. Such a measure would look at ideas and movements from outside DSA’s ranks that can help center internal discussion. From all accounts, this was somewhat lacking at the Convention. The focus on ideas generated from within is, of course, the whole purpose of a national convention and that purpose gains added meaning when rapid growth means finding new ways to cohere. Nonetheless, a more expansive view can sometimes help find a path forward when disagreement seems to block all roads. And here, it might be useful to look at the Moral Monday Movement in North Carolina led by Rev. William Barber II for the concept of a “moral, fusion coalition,” which, in essence, provides a framework that can bring together the various lines of divide expressed within DSA, strengthening unity in difference in the direction of social justice.

Establishing Roots

“The original idea of feminism as I first encountered it, in about 1969, was twofold: that nothing short of equality will do and that in a society marred by injustice and cruelty, equality will never be good enough.” Barbara Ehrenreich, 1986

“Worker rights mean civil rights, minority rights, women’s rights outside in our work-a-day world and inside in our workplace world. Worker rights mean economic rights on the job and in the community. Worker rights mean jobs with justice.” William Winpisinger, 1983

And this returns us to our beginning. One reason for the rapid rise and fall of US left organizations has been lack of roots. When a movement or organization has such, it is able to survive repression, defeat and political mistakes, because its members are known for who they are by neighbors and co-workers. Moreover, political decisions and actions taken with reference to a community give context to organizational initiatives otherwise absent. Any group can make decisions based on sitting around and discussing it – it takes on a whole different dimension when that discussion goes back to thinking what people in a given neighborhood, school or place of employment think. DSA’s new membership clearly is part of the broader stratum of the population emboldened by Sanders, angered by Trump, political positions and decisions which reflect a relationship to that community – a genuine strength. But, by the same token, the new membership does not, for the most part, come to socialism after participation in a strike, or because of a defeated organizing drive, or after going through an eviction. That too was evident in how issues were discussed and how decisions were made – this is a weakness that must be overcome to reinforce the source of strength.

To underscore that point, it is critical to keep in mind the reasons for DSA’s growth. The obvious answer, Sanders/Trump doesn’t say much – for the next question is why they had such impact in 2015-2016. Behind the upheavals during the elections lies something deeper – the general crisis in a system no longer able to paper over the lack of solutions for capital as Reagan did in one form in the 1980s and Bill Clinton did in another form in the 1990s. The ongoing war in Afghanistan, and Iraq, the revelation of government incapacity, environmental crisis and the human face of racist induced poverty revealed by Katrina and then the 2008 financial collapse are the outward signs of a system incapable of solving its own problems, let alone addressing (even inadequately) public need. This crisis is the cause of political instability in the US and abroad, it is an instability that will only be addressed by transformational politics, by a socialism that challenges existing power. If DSA is able to remain focused on that crisis and its manifestation in racist violence, mass insecurity, inequality, and a society wide sense of loss of hope, it ought to be able to consolidate its strength, build strong locals engaged in numerous arenas, maintain an open, self-critical spirit. In other words, be part of the needed response to a country drifting toward barbarism. The Convention was a step toward that end – the future will tell where further steps will lie.

In conversation Stansbury Forum co-editor Peter Olney asked the following questions:

1. Is the whole greater than the sum of its parts? In other words is there unity of action for the 25,000 that can impact society?

2. You mention the lack of experience in “running a strike” etc. Should the DSA privilege or encourage such experience as we did in the 70’s?

Kurt:

Hi Peter – and thanks for wanting to run the article. Your first question is the cardinal one and I really don’t have an answer yet. But my tentative answer at the moment is no the whole is not yet greater than the sum of its part. The potential is there, but whether it is realized or not is another matter. Part of the problem is an old one – people think that they have an answer because growth seems constant, yet they are riding a wave without realizing it. And with that comes a narrow focus that sees victory in the size of an action rather than in whether it moved the process forward. DSA was very much part of the action at Charlottseville, if I was 40 years younger I would have wanted to join them – but still nobody is asking the question of whether the counter protests could have been better organized, with a more massive turnout. I don’t have an answer, what is bothersome is not asking the question. That said, the jury is still out; people are streaming into DSA who are serious, dedicated, looking for a way forward – I just hope our leadership is up to the task. Part of the challenge is for those of us who have been around to not be impatient – remembering how out of touch older radicals once seemed to us. I always recall the Phil Ochs line, “I know you were younger once, because you sure are older now,” and am determined not to fall into that trap (Dorothy, by the way, was incredible in that respect for she had one other necessary quality in a revolutionary: she knew how to listen.

As to your second question – it is amazing to me how little people coming into DSA know about unions – which is really a reflection of how much unions have declined in size and influence. In DC, and I don’t say this critically, we have a number of people in federal jobs, in a union for the first time, who have no context in which to put their union activity. But the other side of the problem is that so many people in union leadership these days have never worked in industry or for an employer other than on campus or for the movement. Unlike our generation that felt a necessity to “join the working-class,” this just isn’t part of the consciousness. One of my favorite Winpisinger anecdotes was his explaining that in a proposed labor-management industrial planning board he inserted the provision that the union reps should have “hand on production experience.” That way, he explained, Kirkland (then President of the AFL-CIO) couldn’t serve. His fundamental point – union leaders should come from the rank-and-file. It will take a long struggle for the labor movement to regain that understanding.

U.S. coal production rose in 2016. Now it’s falling again

By Mason Adams, 100 Days in Appalachia

This story was originally published by 100 Days in Appalachia, a collaborative project from West Virginia University’s Reed College of Media, West Virginia Public Broadcasting and The Daily Yonder. It’s a great site and we encourage all to take a look.

A national bump in coal production that started in mid-2016 may be pausing or even coming to an end, although overall job growth and production in Central Appalachia continues to grow.

The downtick in production figures was reported Thursday by SNL Energy, a publication produced by S&P Global Market Intelligence. SNL analyzed major producers reporting second-quarter figures to the U.S. Mine Safety and Health Administration. The decline in production from the first quarter was felt across most regions but especially in the Powder River Basin in Montana and Wyoming, which produces by far the most coal in the country.

Appalachia produces only about a quarter of the coal in the U.S., but fetches substantially higher prices.

Even with the drop from quarter to quarter, however, coal production is up substantially from the same quarter one year ago. The second quarter of 2016 marked the bottom of a sharp if short-term decline in coal production from 2015.

Both steam coal, used for generating electricity, and metallurgical coal, used in making steel, saw growth over the past year, driven largely by a growing export market. Coal exports grew by more than 50 percent from the first quarter of 2016 to the first quarter of 2017.

“The increase in production from Central Appalachia mines paired with increased overall employment suggests coal companies may be going after more labor-intensive production as international pricing for metallurgical coal has improved,” wrote SNL reporter Taylor Kuykendall.

*Drumroll*

….

Most data is in and it points to coal production falling again, even as jobs nudged upward: https://t.co/SljpxD7XfX pic.twitter.com/tGprivwLlJ— Taylor Kuykendall (@taykuy) July 20, 2017

Industry associations remain optimistic despite the quarter-to-quarter decline in production.

Luke Popovich, the National Mining Association’s vice president of external communications, noted in an email that China restricted its metallurgical coal production last year, which increased prices and led to more demand for U.S.-mined coal. Steam coal benefited from international demand as well.

“The export picture has really picked up,” Popovich wrote. “Met coal exports through May of this year are up 27 percent [according to commerce department data]. Meanwhile, steam coal exports have nearly tripled this year—and like met coal they’re up in all regions. And surprisingly, our steam coal exports to Europe have risen 120 percent through May.”