Organizations and Individuals in the Same Party: Understanding the WFP

By Luke Elliott-Negri

In 2001, the Working Families Party (WFP) was barely two years old. Members of the central Brooklyn political club wanted the party to back their preferred candidate for city council, Steve Banks. When the club met, there were a couple dozen WFP members present. They voted overwhelming for the party to support Banks.

But the other candidate in the race was a party co-founder with many strong relationships in and around the WFP: Bill de Blasio.

The endorsement process in New York has always involved party members interviewing candidates and then making a recommendation to a body of the labor and community affiliate organizations. With a supermajority, the affiliates can override the recommendation – which is precisely what they did with the Banks recommendation, keeping the party out of the crowded race. Some members were understandably angry, but it was not the first or the last time they would grapple with the power dynamics between individuals and organizations in the WFP.

The rest of the de Blasio story is history. He became a city councilor, and a few years later, the WFP ran his citywide campaign for Public Advocate. They ultimately played an important role in his successful bid for the mayor’s office, and many WFP staffers went in to his administration. Whatever his limitations have been, the party gets a real portion of the credit for paid sick leave, universal pre-k, and the hundreds of union contracts that de Blasio settled after Bloomberg’s union-busting years.

Fast forward to 2019, and the process by which the Working Families Party decided to endorse Elizabeth Warren for president has created a great deal of anger and confusion. Of course, some are – understandably! – angry with the substance of the decision, arguing somewhat foolishly that the party has “written itself out of history” by choosing not to back Bernie. Many are concerned about the process. They suggest that the WFP “rigged” the system for Warren, or that it was designed to allow the “leadership” to override the “membership.”

It has been a tense moment to say the least, and as a Bernie supporter, I was not happy with the outcome. But in the best case, the tension, the concerns, the accusations present an opportunity to grapple with a fundamental dilemma for the left with respect to building party and party-like formations: how should such entities balance individual members and organizational affiliates?

From the day it was born the Working Families Party has grappled consciously with this issue. Early internal party memos describe the tensions of balancing individuals and institutions. And these are live questions in other left parties globally. The British Labour Party for example, took its leftward lurch when it gave a more powerful role to individual members, and yet organized labor continues to wield power in the party as organized labor.

If the Left is serious about having hegemony within a majoritarian governing coalition to build a democratized, sustainable economy, and about using executive and legislative power to dismantle racism and other forms of oppression, we must grapple with this essential question of how to balance individuals and organizations in party-building. Having answered the question in different ways throughout the years, the WFP has a lot to offer. It is unique in recent left memory in this regard.

The Power of Labor

As the anecdote that opens the piece suggests, the WFP’s balancing has typically tilted more toward organizations than individuals. The great irony in the immense public frustration with the recent presidential endorsement is that it gives far more power to individuals than has been the case historically.

The founding insight of the WFP was, in many ways, to take the power and resources of the left-wing of the existing labor movement, combine them with activist energy, and put both forces to work winning elections and hammering home policy outcomes. It is hard to overstate how complicated such a project is. Even the most progressive wing of the labor movement has a profound, immediate, organizational need to maintain a productive relationship with elected officials. Unions have a very different relationship to members than, for example, a political organization like Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), whose members are self-selecting. As a baseline structural relationship, union members are covered by a collective bargaining unit where they work, pay dues, and expect material benefits as a result. Union members are of course sometimes willing to support projects that are not in their immediate self-interest, but this presupposes a powerful union that has helped to negotiate a strong contract.

All this means that the decision to primary an incumbent is a big deal. This contrasts in a striking way, for example, with most post-2016 DSA electoral work. Accountable to self-selecting individual members and unencumbered by formal ties to large institutions, primarying incumbents from the left is the raison d’être for DSA’s electoral efforts. The dynamics are just as complicated for organized labor inside legislatures; again, even for the progressive wing of the labor movement, the decision to spend down political capital on broad working-class issues rather than on those that are most salient for members constitutes an actual short-term sacrifice (even if there are obvious long-term benefits, both practical and political).

Against all odds, the WFP managed to execute this model with reasonable success over many years, actually gaining more labor affiliates as they amassed power. The party used resources, for example, to primary a sitting District Attorney, making the campaign a referendum on New York State’s racist Rockefeller drug laws. The party won the race, and a state where two of the three branches of government were in control of the Republican Party began immediately to dismantle the laws. The party has repeated this model – which I think of as “primarying for policy” – in many different contexts over the years.

In the party’s home base in New York, their battle with Governor Cuomo has led many unions to leave the organization. Over 20 years, there has been an arc of increasing and then decreasing affiliation of the major unions. The decreasing side of the arc is a direct product of the governor. But in Connecticut, for example, the party’s second oldest state operation, they have gradually accumulated labor affiliates without the kind of ruptures that happened in New York. In large part, this hinges on state-level electoral law: New York law forces the party to make a choice in the governor’s race in order to have ballot access, while Connecticut does not. Law in the latter state has never forced the party into a battle for which it was not fully prepared.

At the national level as well, labor continues to play a significant role in the party. However, the WFP has also drawn increasingly close to the Center for Popular Democracy (CPD) in recent years – no doubt in part as a result of the bruises in New York, where organized labor has more money than basically anywhere else in the country (excepting perhaps California). There is a “back to the future” story here: the WFP’s predecessor organization, the New Party, essentially functioned as the electoral arm of ACORN in the 1990s, and CPD includes much of the former ACORN network.

Labor unions and groups like CPD are, in some ways, vastly different creatures. But for the WFP – and for the left more generally, I believe – they drive much the same dilemma: on the one hand, if the party gives too much weight to individuals, the organizations have much less reason to engage and fund the party. On the other hand, if the party gives too much weight to the organizations, individuals will take their activism elsewhere. Again, DSA, unencumbered by institutional relationships, responds much more directly to the will of its individual members.

The Warren Endorsement

Some left-wing narratives that have developed around the WFP’s decision to back Elizabeth Warren display confusion about the party’s basic model, its trajectory as an organization, and also the question that drives the party forward and that the whole left must ultimately reckon with – how best to stitch together organizations and individuals in the same formation.

The endorsement was decided by two equally weighted halves, reflecting the party’s long-standing tension: individuals on the one side, and representatives of state and organizational affiliates on the other. Given the history of WFP, a 50/50 split is, to me, totally reasonable. Terms like “superdelegate” miss the mark. The organizational votes – brought together in what the WFP calls its National Committee – represent bodies or constituencies, state committees, affiliate members and the like. The individuals who National Committee members represent are free to vote as individuals and in some cases did. But the point of the WFP model is to engage organizations as organizations and to balance that engagement with individual party members and identifiers.

As party leaders have written publicly, the 2019 process actually weighted individuals more than the last presidential endorsement process. And in general, in recent years the WFP has been attempting to tilt the historic balance of organizations and individuals toward the latter. This is driven by a number of factors, including the expansion of the organization well beyond New York, in places where organized labor cannot provide the same financial resources. In New York, the tilt toward organizations was often worth it because of the financial and political clout the party could leverage.

The National Committee members – like the rest of the organization – voted by secret ballot, so who voted precisely which way is unclear. But by all accounts, the Center for Popular Democracy and its affiliates were key champions of Warren in the WFP process.

The sad reality for Sanders supporters like me is not that the system was rigged, but that we did not organize within it more effectively. Certainly, CPD’s relationship with many institutional members was an advantage in Warren’s effort to garner National Committee support. But Sanders supporters within the party and the campaign itself could have sought those same votes with more rigor. As a very concrete example of how seriously the Warren campaign and her supporters took the process (and of my own failures in this regard), a Warren supporter attempted to whip my state committee vote – and yet I did not do the same individual-level outreach for Sanders.

The process was far from perfect, but it was not, in my estimation, a foregone conclusion that Warren would come out the winner. Sanders could have juiced his support on the individual side (where he likely got more of his vote anyway, but not all of it) encouraging his own lists to register for the process. But the more important work, of course, would have been to organize directly in the constituencies to which National Committee members are responsive, as well as the members themselves.

How Working Families Party Can Do Better

While I think it is important to clarify misperceptions about the WFP and the presidential endorsement process, the party could have done better – and can yet do better going forward.

The National Committee

While it is the case that Bernie supporters and the campaign itself could have lobbied National Committee members directly and more effectively, it is also the case that it would have taken some basic work. The names, affiliations, and, in my view, email addresses of each member should be on prominent display on the WFP’s website, and yet they are not. Even in my home in New York, where I cast one state committee vote for Bernie (and another as an individual), I actually do not know which two individuals carried the outcome of our state process to the National Committee. I could have easily asked around – and regret that I didn’t organize in this more precise way – but the party could also make such a prospect easier. Even something as simple as making it possible to contact NC members by email would provide a sense of clarity about and connection to the organizational side for individuals in the party.

Defining membership

In my estimation, the WFP is caught between seeing individuals in the party as part of an email list and as dues paying members with a vested stake in the organization’s well-being and trajectory. That these two groups were mashed together into a single 50% of the presidential endorsement vote suggests that the party sees the difference yet is also unresolved on how to proceed with it. Asking people to affirm the party’s values in order to participate in the presidential process was a useful way to bring new people into the party’s orbit. But on the other hand, it seems intuitive to me that someone who pays monthly dues should have greater influence over the party’s trajectory than someone who signed up for the email list two days ago.

As the party eases toward a greater role for individuals, a path that it has been on for several years, defining membership more precisely – and distinguishing it from loose supporters – will be important for the party. To this end, the party can look to its own history of developing WFP members in the late 90s and early 2000s, before building a digital base was on most people’s radar. On the one hand, organizations had much more power then, but on the other, members were individuals who paid dues and/or registered for the party. They met in rooms, and made plans.

LESSONS FOR THE LEFT

As a purely defensive matter, Sanders and Warren supporters will have to come together after the primary, whoever is at the top of the ticket. Trump is very capable of winning another four years in office, and it must be all hands on deck to keep proto-fascism from becoming fascism proper.

But taking a minute to imagine new horizons, there are vital lessons to learn from the hard work, the ups and (yes) the downs of the WFP. Perhaps if we think New Deal liberalism is the best we can do, then maybe the left can avoid the dilemmas that the WFP has faced. We can stumble along with inchoate coalitions and maybe even get legislation as strong as we saw in the 1930s and 1960s. But if we think a more serious democratization of our economy and society is in order, we may well wind up in something like Salvador Allende’s Popular Unity in order to have hegemony in a majoritarian governing coalition. In that case, there is literally no contemporary U.S. model that I know of to study and engage other than the WFP, because no one else has spent 20 years trying to hold together many organizations and individuals in the same party.

We ignore the WFP’s successes, limitations, and dilemmas to our own detriment. On other hand, if we take the organization seriously, grapple with its underlying dilemmas, and learn lessons from both its successes and mistakes, we will be in a stronger position to win the kind of world we must win if we are to keep the planet from burning.

.

This piece was first published by our friends at Organizing Upgrade

Letter from England

By Myrna Santiago

September 17, 2019

Remember when not so long ago there was a proposal to pull Greece out of the European Union as a way to escape the crisis created by millionaires borrowing so much money they bankrupted the country and threw it to the financial sharks? Who would have predicted then that Greece would remain and Britain would vote to leave the EU?

With October 31st looming over the horizon as the date Britain is supposed to exit the EU for sure, the country is alternatively pulling its hair by the roots, mute in shock and panic, or else attacking immigrants because it hasn’t left already.

Having spent four days at a conference between London and Birmingham, my superficial observations confirm what everyone following the story closely already knows: no one knows what Brexit will mean but it has the potential to be truly chaotic.

A Welsh friend, in fact, described this as a “revolutionary situation,” with the possibility of dissolution of the country – thinking that at least Scotland might exit Britain in the post-Brexit era. (There is talk of a unified Ireland as well.) Certainly the political parties are being shaken to the core, with splits and defections and rearrangements taking place on a daily basis. The Liberal Democrats, for instance, a party badly hurt in the last election has now gained seats in Parliament not through votes but because Tories have switched parties and joined their ranks—except that Parliament has been suspended by the Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, (today ruled illegal by the Supreme Court – with Johnson saying from NYC that may not be how he reads the ruling) prompting some television comedians to develop a whole skit asking, without censorship, “WTF???” at every turn. (

Meanwhile, both London and Birmingham are under construction, quite literally. Cranes, closed streets, and construction equipment reveal that someone was betting on boom times and sunk a great deal of money into real estate. A conference attendee with ties to the construction industry, in fact, says that her sector is focused on the luxury market, both million-dollar homes and expensive apartments, many of which already are or will be empty because the owners live elsewhere on the planet and come to London only for a few weeks a year. They bought those properties as investments, but with Brexit, will they be vacationing in England rather than the UK? In any case, she says, those rich homes have created ghostly neighborhoods that do not create or support a local economy.

The HSBC bank, meanwhile, stubbornly clings to the idea that London should remain the financial capital of Europe, reminding people “we are not an island. We are part of something far, far greater.” The billboards don’t say if that greater entity is the EU, but it sure sounds like it, especially when those ads are immediately followed by one paid for by its Majesty’s Government telling everyone “prepare for Brexit,” and giving them a website to visit. Will the website spell out what to put in the earthquake kit? Maybe medicine, food, and fuel—all the shortages that are expected to happen?

There are signs of the economy taking a hit already. In Coventry an important auto manufacturing plant already closed but a train companion explains that the government attributed that to the regular economic downturn, unrelated to Brexit, like the way Category 5 hurricanes in the Caribbean have nothing to do with global warming. The iconic chain Mark & Spencer, established in the late 19th century when department stores first emerged in London to display and sell the fruits of empire, is on the verge of bankruptcy, with more ads asking if the store can be saved by adding prepared meals to the menu. Indeed, the one near my hotel now features food porn as window dressing: a delectable roast chicken to go with your autumn coat this season?

“Chaos” is what the Liberal Democrats predict at their party conference, which parallels the one I am attending, come Brexit. Go with us and we’ll save Britain and the planet simultaneously by ushering “green capitalism,” says some party leader to the faithful. Who knows? Right now the only ones really pulling ahead on this uncertain race are the late night TV comedians. They can’t keep up with the material Brexit generates on a daily basis. How else besides mockery can anyone deal with a Prime Minister who compares himself to the Incredible Hulk, the puke green comic book character who grows bigger and bigger the angrier he gets? But even as they skewer their Prime Minster, the comedians can’t help but ask, in all seriousness, really, people, WTF???

For more:

A good place to start: Jacobin Radio piece on Brexit

Developments from the weekend and today (24 September 2019)

Brexit divisions threaten to plunge Labour party conference into chaos

Corbyn defeats bid by activists to campaign for remain at election

Starmer has ‘mixed feelings’ on Corbyn’s neutral Brexit stance

The Guardian view on Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour: time to come together

Supreme Court: Suspending Parliament was unlawful, judges rule

“Got to see where this stuff comes from, …”

By Peter Olney

On June 21 our friends Giacomo Benvenuti and Wahiba Taouali came to visit us from Austin, Texas. Giacomo is the son of Nicola and Anita, our dear friends from Florence, Italy. Wahiba is married to Giacomo, and she is from Tunisia. Wahiba is an information engineer and Giacomo is a neuro-scientist doing a post doctorate at the University of Texas. They stayed with us for 5 days. I wrote them both this letter on July 4th because I treasure their visit to us and hope they come again. I also appreciate the fresh energy and perspective they brought to my world!

.

July 4, 2019 San Francisco, California

Dear Wahiba and Giacomo,

I decided to write this overly long snail mail after your wonderful visit to San Francisco in late June. I happened to see the enclosed magazine Fast Company at my gym, and thought it might be of interest to you after our visit to Silicon Valley on June 25th. Their annual list of “The 100 Most Creative People in Business” caught my eye, and sure enough some of the “100” are employees of Apple and Google the two companies whose campuses we visited in June.

During your visit we did some of the usual tourist things like our bay cruise, hiking on Angel Island and lunch in Tiburon. But it was your request to see Silicon Valley that intrigued me. As always it takes visitors from out of town to awaken you to compelling things and points of interest in your own back yard. Lonely Planet has a couple of suggested tours of Silicon Valley, but they want you to spend $400 to be chauffeured around. You put together our tour with stops at Apple, Google and the brain center of the valley, Stanford University in Palo Alto. On our way home we made a late lunch stop at Buck’s in Woodside. I have been eating there for many years, but until your tour I never knew it was a favorite spot for tech folks to meet and make deals. Not my world!

Part of the challenge in thinking about such a tour is what defines Silicon Valley? I suppose you could start with the garage startups of Hewlett and Packard and Steve Jobs. Those sites are houses in Palo Alto and Los Altos. But production facilities and HQ’s have spread from San Jose all the way to San Francisco so loosely speaking that is the “Valley”. It is a far cry from 70 years ago when the area around San Jose was known as the “Valley of Hearts Delights” and was a major fruit production zone.

We drove south 42 miles from our home in the Sunset District of San Francisco to Cupertino for our first stop on the tour: the new Apple Headquarters on Tantau Avenue. This giant circle structure that resembles a big donut or a flying saucer houses 12,000 employees. Inside the donut are 175 acres of land with a pond and multiple landscapes. The only way to see the campus is to have business there or know somebody there. I am still kicking myself that I forgot prior to our visit that a high school classmate, with whom I just reconnected at my 50th reunion, is the Chief Vision Scientist at Apple. What a title, and certainly someone who could have given us a tour. I still am not sure whether his title means he is responsible for envisioning the future of the company, or whether he is just responsible for designing Apple apps that relate to the human eye? Or maybe both. Next time you come we will get together with him and his wife who also works for Apple. I would love the title of Chief Vision Scientist for the labor movement!

Even if we had gotten inside the big doughnut we still would not have been able to appreciate its immensity. That requires “googling” an aerial view on line. So we stood outside the gates of headquarters in the Apple store where a security guard told us that the facility was recently opened with a private concert by Lady Gaga for employees only. I love Lady Gaga (Stefani Joanne Angelina Germanotta), but I am not sure how I feel about a private Apple performance.

There was a Labor Dispute at the gates of Apple. A giant banner was displayed with a grim reaper hanging over it: “Stop Hurting Workers, Families and Community” Carpenters Local 405 is in a dispute with Technical Builders, Inc. which is constructing a parking structure for Apple. It was a captivating banner and display, but unfortunately the paid hand biller didn’t know anything about the dispute and couldn’t answer my questions about it. Kinda disappointed in my union brother….

From Cupertino it was a short hop of 9 miles to the Googleplex campus. Google is building a giant new HQ that kind of resembles the Sydney Opera House with its massive shell like structures. The present complex houses 53,000 employees and is situated on the old Silicon Graphics campus. Unlike Apple the campus was very accessible with information booths and friendly Google employees answering questions and pointing out places of interest. We took a great photo in front of that iconic Google sign on one of their main buildings, and we roamed around looking for a bottle of water and found none even in their corporate store. That was kind of inhospitable. However I remembered that Google employees worldwide had conducted a strike at 40 offices with 20,000 employees participating on November 1, 2018 to protest Google’s handing of complaints of sexual harassment. Pretty impressive for employees who have no union representation! Maybe we in traditional labor can learn something from them.

Our final stop before lunch was the campus of Stanford University in Palo Alto, the brain center of much of the Silicon Valley tech business. We couldn’t find parking so I delivered you guys as close as I could get us to the iconic Hoover Tower, the home of the Hoover Institute, an infamous right-wing think tank! Thankfully your walk around was short, and we went on to our lunch at Buck’s!

I have to thank you both for opening my eyes to a reality that exists right at my doorstep. When you first suggested a visit to the Silicon Valley, I thought what for? Why bother? But then I thought wait a minute I use Google everyday for directions; to search out facts and places, and then of course I use Google Translate to hone my email to Giacomo’s parents in Italian! Google plays a major role in my life. So does Apple. I got an Apple desk computer and an I-phone! Shunning knowledge of Google and Apple would be like a Model T car owner shunning the River Rouge Ford plant in Detroit in the last century. Got to see where this stuff comes from, and who is making it and the actions they are engaged in.

Well, as I said when you were both here, please take the time to read the book The Circle by Dave Eggers. It paints a pretty dark picture of the Valley’s culture and groupthink, and it is kind of contradicted by the recent labor unrest at Google thankfully, but nevertheless worth a read.

Hope you come back soon so you can open our eyes to more realties in our own back yard.

Stay cool and dry in the Texas heat!

Love and hugs,

Peter O

…

Different Worlds: Life in the German Democratic Republic A Review of Talks and Writing by Victor Grossman/Stephen Wechsler

By Kurt Stand

“The GDR threw out the Vialons and Scheels, the Krupps and Flicks, the Thyssens and Deutsche Bankers, the Globkes and Gehlens [corporate heads, ideologists, military leaders, lawyers who facilitated and implemented fascist criminality] … My hatred of those who build and ran Auschwitz and Treblinka led me to resolve ‘Never again.’ For me, this included Jews and Palestinian Arabs, Poles and Roma, Congolese and Kurds, Tamils of Sri Lanka, Rohingya of Myanmar, and oppressed people everywhere. Black men or women in the ghettos, gay or transgender victims or Native Americans on the North Dakota prairie: all are my brothers and sisters!”

“There were undeniably blots, far too many, which hastened the final failure [of East German socialism]. I don’t want to prettify the past. Avarice, egoism, envy, and other failings could not be eradicated by even the best laws or most socially conscious system … Humans rarely become angels. But there do seem to have been changes: comparisons shortly after [German] unification showed East Germans on the average less motivated by a craving for more money and laying more value on family life. With little pecuniary rivalry, they tended to be friendlier with one another. Women, despite the burdens of household and family weighing heavier on their shoulders then on men’s, were more satisfied at their independent roles on the job with other people, and better able to defy patriarchal pressures.”

Nearly 30 years have passed since the Berlin Wall crumbled followed quickly by the collapse of the German Democratic Republic. Thus ended the attempt to build socialism on one-third of German soil. Along with that failure came a version of history in which the totalitarian East was inevitably defeated by the liberal capitalist West because of the inherent virtues of free markets. Buried in the Cold War triumphalism of German unification, the questions of what happened, why and what it all meant were left unasked, let alone answered as capitalism – unencumbered by alternatives in the East — was seen as ready to launch into a golden age. In the years since, however, the bloom has fallen off the rose; Germany’s economy has grown but so too has inequality, poverty and dislocation – realities even more apparent in the United States. Unification was supposed to be a step toward peace, but the US and NATO have since been engaged in endless wars of aggression. Germany’s military budget and arms sales have grown too, while engaging in military action around the world, something that had been unthinkable in 1945, something that was not supposed to happen when the Wall came down. Most concerning has been the revival of strength of neo-fascist movements, right-wing demagogues, unvarnished anti-Semitism joined to an especially toxic Islamophobia.

These developments raise the question of why the defeat of Germany, Italy and Japan during World War II did not bury fascism once and for all. So too, the 2008-9 banking crisis – which hit Europe as it did the United States – raises the question of why capitalism, unrestrained by even a flawed or weak socialism, has been so unable to meet popular needs, to provide security or prosperity for working people. Capitalism’s failures has removed socialism from the list of taboo words when looking at political alternatives and has given space for a more honest and nuanced look at what went right, what went wrong, during those years of the GDR’s existence from 1949-1991.

Victor Grossman, on a national tour discussing his book, A Socialist Defector: From Harvard to Karl-Marx-Allee, spoke with such honesty along with sympathy for what the GDR accomplished and attempted. At age 91, he was not, however, only concerned with the past; he addressed GDR history with an eye to contemporary relevance in well-attended talks in Washington DC. He spoke at the progressive event space Busboys and Poets 14th & V location (May 15), and at the German government-sponsored Goethe Institute (May 17) with Washington Post Senior Editor Marc Fisher moderating the latter. In addition, he addressed the Nation reading group meeting at the Cleveland Park library on May 18.

Victor – whose given name is Stephen Wechsler – has a unique vantage point for he defected from the US to the GDR in 1952, lived and worked there until its collapse, remaining thereafter in reunified Germany, retaining his socialist convictions. Victor’s uniqueness may be noted by one simple fact – he is the only person to have graduated from both Harvard and the Karl Marx University (and given that the latter no longer exists, it is a club of which he is likely to remain the only member). The politics and commitment to a better world that lay behind the decisions which brought him both degrees form a central part of his story.

Born in 1928, growing up observing the ravages of the Depression, the rise of fascism and anti-Semitism in Europe, the struggle to defend and advance the ideals of the New Deal, Victor became a supporter and subsequently a member of the Communist Party while a student at Harvard. That commitment remained and was expressed in support of Henry Wallace’s Progressive Party campaign in 1948 around demands for economic justice, an end to racism, a commitment to peace in the last attempt to give expression to the goals that seemed to realization during the labor-led progressive gains of the 1930s, especially after the World War II defeat of Hitler. Times, though, were changing, the world-wide, war-time anti-Nazi alliance was breaking up as was the New Deal Coalition domestically. Reaction set-in, anti-Communism became almost a state religion and the era of Joe McCarthy witch-hunts began. Congress passed legislation that made the Communist Party a semi-legal organization, the enforcement mechanism being ubiquitous loyalty oaths.

“… this comparison is not to excuse repression as it existed in the GDR, it nonetheless should give pause to those who uncritically accept the too-often promoted Cold War democracy vs. totalitarian framework.”

The Korean War soon took center stage, and with it, military conscription. Victor was drafted and made the fateful decision to sign on the dotted line the statement that he was not a Communist Party member. Sent to serve in Austria, an FBI informant led to a scheduled hearing about the affidavit. Fearing criminal charges for perjury, Victor instead decided to flee to the Soviet-occupied sector of Austria and announced his willingness to defect. Within a year he was living and working in the GDR and there he would make his life (it is a story he recounts in greater detail in an earlier volume: Crossing the River: A Memoir of the American Left, the Cold War, and life in East Germany). It is that unusual double-sided life that enables Grossman to give a fuller, more balanced perspective than most commentators — stressing the positive, to be sure, but without ignoring the negative; the genuine meaning in daily life of the degree of social security and equality the GDR attained as against the social and personal consequences of the narrowness, lack of openness, the democratic deficits the country suffered.

The latter, however, is all that most people know; the Berlin Wall transformed by the media into an image of East Germany as one large prison. Victor asked at the Goethe Institute talk how many people had seen the film, The Lives of Others – most raised their hands. He then pointed out the distortions in its image of a GDR in which all lived in fear. Police surveillance and political repression did indeed exist, and were among the reasons the GDR was unable to survive. But the picture of the film of an all-seeing police state was an exaggeration that had little to do with the actual circumstances of life people lived – moreover GDR actions could not be separated from the real-life attempts to destroy what was being built by West Germany and the US. Grossman added that most commentators failed to note that the film itself could have been a film of McCarthyism in the US (including an accidental, ironic, or wholly unintentional, similarity to aspects of the Alger Hiss case – a notorious early instance of witch-hunting that proved to be the launching pad for Richard Nixon’s national political career).

The point Victor was making in that respect was the need to see developments in relationship to each other. His journey West to East was very much a response to the repression that gripped hold of the United States in the late 1940s early 1950s, repression that resulted in arrests, black lists, deportations, repression that stirred up racist mobs, expanded FBI power and surveillance, repression that weakened democratic institutions within the US. While adding that this comparison is not to excuse repression as it existed in the GDR, it nonetheless should give pause to those who uncritically accept the too-often promoted Cold War democracy vs. totalitarian framework.

Commonplace contrasts between the two systems can instead be turned when it comes to making a comparison between West and East Germany. Victor eventually became a journalist in the GDR and, as such, served as a writer for the Democratic German Report in the early 1960’s publishing the results of research that showed that former Nazis – often high-ranking ones with direct involvement in the promulgation and implementation of ant-Semitic laws, war crimes in occupied territories, placing anti-fascists in concentration camps, overseeing gas chambers – dominated amongst West German diplomats abroad, in the courts, universities, schools, police, other administrative posts and in centers of political and business power. The facts could not be denied, yet the consequence of the exposures had relatively little impact: former Nazis remained over-represented in national leadership and the civil service in the new “democracy.” This passage from an authoritarian to a democratic system did not represent any break with the thinking of the past – the policies and practices of German industry and banks, of Germany’s renewed bid for dominance in Europe and military aggressiveness outside Europe’s borders, in the post-1991 world shows the continuities left over from a lack of confrontation with the past.

West German officials and media attempted to charge the GDR with the same, but the difference was striking – no equivalents could be found in the higher reaches of the government in the East, and those few administrators discovered were not the policy makers and ideologists of the fascist regime. Rejecting those who had set the stage and implemented the policies of the Nazis had widespread consequences. As Grossman explained (and details in his book) it necessitated a rapid process of training people to teach, to serve in the diplomatic corps, to form a new police force and military, to join the civil service. Most of these were working-class people whose upward mobility would have otherwise been sharply limited; they formed the core of support for the new society along with Communists and other anti-fascists who survived the years of terror.

But, as Grossman pointed out, this was not an unmixed blessing – the lack of experience, the swiftness of the training, contributed to the dogmatism and rigidity that was to hamper the GDR throughout its history. Moreover, those who became part of the new society in this way often failed to understand the needs, thoughts, dreams of the generation which came after them, contributing to the alienation of many young people that became so evident in the 1980s. This, in turn, reinforced undemocratic practices, to limitations on popular initiatives, that were at the root of the GDR’s failure – though, he also pointed out that these lay too in a degree of distrust of the population, many of whom, of course, had gone along with the Nazi terror.

Adding to the GDR’s difficulties was the obligation to pay almost all of Germany’s reparations to the Soviet Union, while West Germany was receiving support from the United States in rebuilding its economy. Yet as Grossman points out, despite the flaws and rigidities of socialism as it was being developed in the East much improved over time – incomes rose, housing improved, social amenities became better, there was greater choice in consumer goods, and the quality of life became richer in many respects. Quite to the contrary of the image projected in The Lives of Others, people had privacy and freedom in their personal lives. But democratic input remained limited and in some respects moved backward and with that came a sense of freedom being constricted – especially with the allure of the West which seemed (and, in some respects, was) more dynamic, especially as the insecurity and inequality that underlay that growth was not appreciated by a younger generation who had not experienced the boom and bust cycles of capitalist life.

“However, when it comes to the third freedom –freedom from want – socialism had the stronger argument as it reflected the system’s values.”

Victor noted that his political convictions developed under the influence of the New Deal and felt that FDR’s four freedoms serve as a way to envision a better world – and so as a way to compare the GDR with both West Germany and the United States. Of course, the first freedom is that of speech, and there he reaffirmed that East Germany’s record left a lot to be desired and was the Achilles Heel that played an outsized role in the system’s demise. Though the extent of repression is exaggerated, the repression was real and costly. At the same time, political repression has a long history in the United States as well – being the reason for his decision to defect – and alongside racist repression continues to this day (and repression had a history in West Germany and still does in re-unified Germany today). As to freedom of worship, the GDR’s record was again mixed – churches were open, religious practice was permitted, manifestations of anti-Semitism were illegal – but there is no doubt that main line churches were often the victim of petty repressive measures in a game of tit-for-tat with West Germany which itself was an aspect of the GDR’s never fully overcame democratic deficit.

However, when it comes to the third freedom – freedom from want – socialism had the stronger argument as it reflected the system’s values. People in the GDR did not suffer from homelessness, unemployment, poverty or hunger. Victor writes of how when his wife visited the US (her first time in the West) after the Wall came down, she was shocked at the sight of beggars, for she had never before seen people so desperate for a meal. Quoting FDR that “necessitous men are not free men,” Victor argued that this fundamental right is all too often forgotten and that in this the contrast between capitalism and the socialism they were trying to build in the GDR are most clearly to be found. So too was the final freedom – freedom from fear – which meant that humanity should no longer live under the cloud of war. Grossman again quotes from FDR this too little remembered admonition: “freedom from fear … means a worldwide reduction of armaments … in such a thorough fashion that no nation will be in a position to commit an act of physical aggression against any neighbor — anywhere in the world.” Several months after Roosevelt’s death, the US launched nuclear bombs over Hiroshima then Nagasaki, after which our arms spending and military interventions and wars abroad have been unending, unrelenting and on a scale beyond any other nation of the world. Grossman recounts those wars, that violence, and comments that there is no freedom from fear in the world. In fact, in his talk he noted that climate change has added a new source of fear in the world.

Although attitudes can’t be legislated, social policies can be implemented and here too Victor brought to light positive measures the GDR took to ensure that whatever progress was made, was made for all. The racism and forms of stratification everywhere to be found in the US were banned in the GDR as were the kinds of hate speech that now finds expression in White House orchestrated mass rallies. Victor gave a picture of daily life that, notwithstanding its limitations, was in some aspects freer, more humane than our own, and certainly not the unrelieved grim experience that is often portrayed. In this he challenged the view of the United States and our full-blown capitalism as natural, normal, and inevitable with the contrast of the conscious attempt to create an alternative. Even if the experiment failed the fact that an alternative was tried proved that what exists need not always exist. Others can learn from the GDR’s failure and perhaps do better in the future to come. Questions at both the formal talks he gave in DC touched on this, with a receptivity that might not have been there thirty years ago when socialism appeared buried forever and capitalism on the cusp of a new beginning.

Many (but by no means all) attendees at the Goethe Institute event came with a perspective more critical of the GDR to begin with – and some questions stressed the centrality of individual freedom and as a freedom more respected in the West – but all were asked and answered in a spirit of openness. Some questions were the same at both events, including one that often figures in discussions: with full employment and a relatively narrow gap between lowest to highest pay scales withholding both the fear of job loss and the hope of riches that serve as a productivity engine in capitalist society, can socialism “work”? And, indeed, Victor granted that the question was legitimate. He responded that workplaces were centers of socialization, that a line might be shut down for a number of different reasons even if it meant slowing production. People did their jobs but often did not push themselves beyond that. It is a complex problem and genuine difficulty, Victor agreed, but he added that work need not be oppressive, that it isn’t always necessary to make the maximum effort, that life exists beyond the capitalist imperative of ever more. The real question here is the cost to quality of life by a system of exploitation, the question still to be discovered is what would be valued in a world free of exploitation and war. As much as FDR’s four freedoms, Victor’s explained that his political convictions – his opposition to what capitalism is, his vision of what socialism could be — found expression in Martin Luther King’s 1967 speech against the Vietnam War, his call for a revolution in values “… [for] when machines and computers, profit motives and property rights are considered more important than people, the giant triplets of racism, extreme materialism and militarism are incapable of being conquered.”

Victor’s talk was not meant as either an exercise in nostalgia nor as an idle look at what might be. He was clear on stressing the needs of the moment – his political commitment when young was fired by hatred of fascism and so today he stressed the need to combat the growing strength of neo-fascism in Germany, the need to combat Donald Trump’s racism and authoritarianism. When young, he was inspired by the promise of the New Deal and the politics that sought to ground it in workers’ struggles and deeper structural change. Today, he takes heart from the wide support Bernie Sanders has generated – his popularizing of socialism in the context of a militant challenge to corporate power has its roots in the same New Deal ideals. So too does the proposal of a Green New Deal authored by Rep. Alexandria Cortez-Ocasio and other newly elected representatives in Congress on behalf of a younger generation committed to a different and better future.

Being attuned to current progressive initiative contributes to a spirit of optimism that runs through Grossman’s book and talks. This stems from a life of commitment that learns from defeat rather than using it as an excuse to turn away from life. That is best expressed in the closing lines of A Socialist Defector:

I believe that what I wrote, said, or did was for a good cause, and despite occasional mistakes I have no real regrets. And I still have great hopes for a happier future for everyone, everywhere! They are expressed in two of my most cherished songs. One is the fighting miners’ sing “Which Side Ae You On?” The other, full of hope for tomorrow’s man – and definitely woman: “Imagine no possession, I wonder if you can, no need for greed or hunger – a brotherhood of man.”

.

Note: All quotes are from A Socialist Defector From Harvard to Karl-Marx-Allee by Victor Grossman/Stephen Wechsler (Monthly Review Press, New York, 2019)

…

A GI Rebellion: When Soldiers Said No to War

By Steve Early

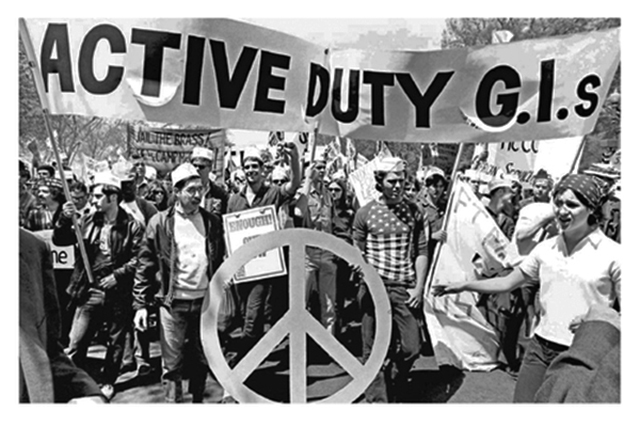

Fifty years ago this fall, a campus upsurge turned opposition to the Vietnam War into a genuine mass movement.

On October 15, 1969, several million students, along with community-based activists, participated in anti-war events under the banner of the “Vietnam Moratorium.”

A month later, 500,000 people came to a Washington, D.C. demonstration of then-unprecedented size, organized by the “New Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam.”

As we approach the 50th anniversary of both the Moratorium and Mobilization, it’s worth recalling one critical anti-war constituency whose role was less visible then and remains little acknowledged today.

While student demonstrators and draft resisters drew more mass media attention at the time, many military draftees – reservists and recently returned veterans – also protested the Vietnam war with equal fervor and often greater impact.

Fortunately, three Vietnam-era activists have just published Waging Peace (New Village Press, 2019), which gives long overdue credit to anti-war organizing by men and women in uniform, and their civilian allies and funders.

Labor organizer Ron Carver, Notre Dame professor David Cortright, and writer/editor Barbara Doherty have crafted a beautifully-illustrated 240-page tribute to the GI anti-war movement. Waging Peace includes fifty first-person accounts by grassroots builders of that movement, plus photo documentation of their work by William Short, a Vietnam combat veteran.

As Cortright notes in the book’s introduction, social science researchers hired by the military (and later academic experts) concluded that one-quarter of all “low-ranking service members participated in Vietnam-era antiwar activity.”

This percentage is “roughly equivalent to the proportion of activists among students at the peak of the anti-war movement.” In the rural and conservative communities, which surround most military bases then and now, “the proportion of anti-war activists among soldiers was actually higher than in the local youth population.”

The Anti-Warriors Today

Now in their late 60s and 70s, many anti-warriors profiled in Waging Peace are long-distance runners in the field. Some remain active in Veterans for Peace (VFP), which held its lateste national convention in Spokane. One highlight of that annual gathering was the unveiling of archival material and photos that appear in Waging Peace.

This hotel ballroom exhibit included many striking examples of underground press work–mimeographed newspapers for GIs with names like Last Harass, Up Against the Bulkhead, Attitude Check, or Fun, Travel and Adventure (whose acronymic double message was “Fuck the Army!”

Among those viewing younger portraits of themselves in Spokane – along with documentation of their own anti-war activity – were ex-Marine Paul Cox, Army veteran Skip Delano, and former Navy nurse Susan Schnall. In Waging Peace, each one shares a memorable tale of personal transformation, due to their wartime experiences at home or abroad.

A native of Oklahoma, Cox served as a platoon leader in Vietnam’s Quang Nam Province in 1969. There he witnessed a massacre of civilians, “smaller scale but no less barbaric” than the mass killings at My Lai which occurred a year earlier.

After completing his combat tour, Cox was assigned to Camp Lejeune in North Carolina. He and several Maine buddies decided it was “our duty to put out a newspaper and print the truth about Nam.”

Over a two-year period they, and later recruits, produced thousands of copies of a clandestine publication called RAGE. As Cox says today, “RAGE was definitely not an example of great journalism.” But it did allow him to redirect his own anger and disillusionment into an effort “to warn others who were about to be deployed.”

In Vietnam, Skip Delano was assigned to a chemical unit attached to the 101st Airborne Division. After his return to Fort McClellan in Alabama, he believed he had earned the right “to comment on the war to other people”—an opinion not shared by his base commander.

Delano helped write and edit a GI newsletter called Left Face, whose distributors faced six-months in the stockade if they were caught with bulk copies. In October of 1969 he and 30 others bravely signed a petition supporting the Mobilization scheduled for the following month in Washington, DC. This deep South expression of solidarity with civilian protestors up north triggered Military Intelligence investigations and interrogations, loss of security clearances, and threats of further discipline.

Protesting in Uniform

A year before Delano’s dissent, Susan Schnall’s dramatic acts of Bay Area resistance drew heavy military discipline. She was court-martialed, sentenced to six months of hard labor, and dismissed from the Navy for “conduct unbecoming an officer.”

Schnall grew up in a Gold Star family; her father, who she never knew, was a Marine killed in Guam during World War II. As a Navy nurse in 1967, she toiled among “night time screams of pain and fear” that came from patients badly wounded and recently returned from Vietnam.

In October, 1968, Schnall became involved in a planned “GI and Veterans March for Peace” in San Francisco. To publicize that event, she and a pilot friend rented a single engine plane, filled it with thousands of leaflets, and dropped them over local military facilities like the Presidio, Treasure Island, the Alameda Naval Station, and her own workplace, Oak Knoll hospital in Oakland.

Then, in full dress uniform, she joined 500 other active duty service people, in a march from Market St in San Francisco to its Civic Center, where they were cheered by thousands of civilian protestors.

Fifty years after Cox, Delano and Schnall rallied their uniformed comrades against the Vietnam war, all three are still engaged in causes like defending veterans’ healthcare against privatization by the Trump Administration.

Later this fall, they and other VFP members are helping to bring the Waging Peace exhibit to Amherst and New Bedford, Mass, New York City and Washington, DC. Next Spring, this book-based display will reach campus or community audiences in Seattle, San Francisco, and Los Angeles.

Red State Resistance

Activists today, particularly those involved in working class organizing, should buy this book or see the exhibit based on it. Local-level leaders of the GI movement displayed courage, creativity, and audacity when rallying their own “fellow workers” who had been conscripted by the hundreds of thousands.

Much rank-and-file education and agitation about Vietnam occurred on or near heavily guarded military bases located in what are now called “red states.” They became unexpected incubators for homegrown (and imported) radicalism.

Some forms of GI resistance, referenced in the book, involved sabotage of equipment, small and larger scale mutinies, rioting in military stockades, and deadly assaults on unpopular officers, known as “fragging.”

The national network of GI coffee houses described in Waging Peace became places where soldiers and sailors could relax, socialize, listen to music, read what they wanted, and have fun with each other and their civilian supporters. This helped break down the military vs civil society divide that is far wider today–due, in part, to the post-Vietnam creation of a “professional army” to replace the rebellious conscripts of fifty years ago.

Thanks to their low morale – and heroic Vietnamese resistance to foreign aggression – U.S. ground forces were no longer “an effective fighting force by 1970,” according to Cortright. “To save the Army,” he says,” it became necessary to withdraw troops and end the war. Their dissent and defiance played a decisive role in limiting the ability of the U.S. to continue the war…”

In an era of “forever wars,” it may be hard to imagine such impactful organizing among active duty military personnel or newly-minted veterans. Let’s hope that the many examples of grassroots activism in Waging Peace prove inspirational and instructive for younger progressives today.

This valuable book might even stimulate some new thinking about how the left can better relate to the 22 million Americans who have served in the military or continue to do so – to their own detriment and that of people throughout the world.

…

Beyond the Waterfront!

By Peter Olney

Editor’s Note: Just as I was sitting down to read Peter Cole’s excellent book, a dispute broke out in the Port of Los Angeles over automation and the future of work.I couldn’t avoid commenting on that dispute and much of my review examines the challenges facing the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU). But as an activist historian I am sure that Peter will not mind the fact that his work inspired me to think about the future of workers on the waterfront and beyond. Solidarity!

.

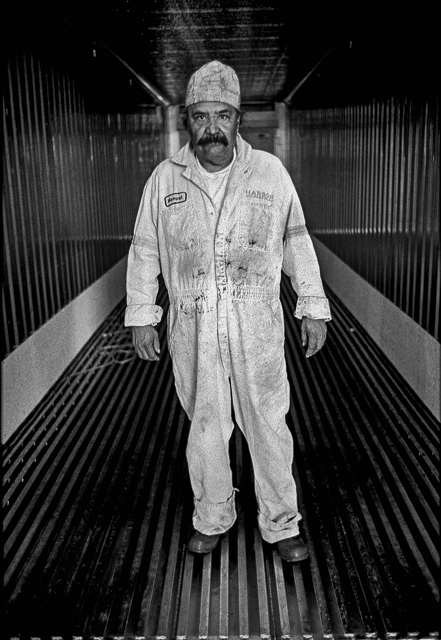

Photo: ©1983 Robert Gumpert

Book Review: Dockworker Power Race and Activism in Durban and the San Francisco Bay Area, Peter Cole, University of Illinois Press 2018

Almost alone among unions, the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU) employs a full time librarian and archivist. In my 17 years as Organizing Director I would often take my lunch down to the third floor of the union’s headquarters in San Francisco and gab with Librarian Gene Vrana or his successor Robin Walker. Beyond maintaining the union’s archives, books, newspapers, clippings and oral histories, they were both a treasure trove of knowledge about the union’s history and traditions. Perhaps no other union in the United States besides the United Auto Workers has been the object of so many histories, articles and speculation. Peter Cole has added a fine volume to that pantheon with his comparative study of dockworkers in the Bay Area with their counterparts in the Port of Durban, South Africa. His book recently won the Philip Taft Labor History Book Award for 2019.

Cole’s Contributions

Cole focuses his examination of the two dockworker groups on their often unheralded contributions to the struggle for racial justice. He also examines their responses to port automation – the introduction of containers. And finally he draws out their participation in international solidarity actions.

In two very interesting observations Cole contextualizes working class power in time, place and socio-political conditions.

First he draws out a discussion of the process of casualization and how it can serve or inhibit the working class struggle depending on social and political context. As many American readers know the “shape up” was the classic casual labor relationship on the waterfront prior to the great maritime strike of 1934 on the West Coast. The ship’s boss would come down to the docks looking for labor and pick a crew arbitrarily from workers “shaping up” on the waterfront. This was a system prone to extreme favoritism and discrimination based on caprice or the boss man’s strategic discrimination against troublemaking labor activists. The 1934 strike and its subsequent settlement put in place a hiring hall that was controlled by the union with a non discriminatory dispatch system. The hiring hall ”low man out” was a powerful weapon that eliminated the day-to-day power of the employer over the workforce and spawned much of the independence and political activism of the ILWU.

In South Africa on the other hand the “togt”, a labor system based on the causal labor of Zulu tribesmen who worked day to day with no permanent relationship to the employers, ended up benefitting the workforce in its struggle over wages and conditions. Unions were banned, and there was no permanent employment system so Zulus would just not “shape up” in effect striking but with impunity because they had no permanent employment relationship that they were severing. The employers later instituted an employment system in order to dominate and control labor.

A second example of the two unions and their comparative histories yields another historical irony and a deeper analytical point. The ILWU throughout the long struggle to end South African apartheid had played an active role in support of liberation. Nelson Mandela saluted the ILWU on his 1990 visit to the US after being freed from 27 years in prison. At a rally before 60,000- in the Oakland Coliseum he declared, “We salute members of the ILWU Local 10 who refused to unload a South African cargo ship in 1984….” Fast-forward to 2008 post apartheid and the South African Transport and Allied Workers Union (SATAWU) refused to unload arms from a Chinese ship docking in Durban. The arms were destined for the repressive regime of Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe. As Cole points out the South African constitution legally protected the SATAWU action in 2008, and a South African judge ruled in favor of a potential freight boycott, whereas in 1984 a San Francisco Federal judge slapped the ILWU and boycott leaders with injunctions.

This difference spotlights a more profound point, one very artfully articulated by sociologist and researcher Katy Fox-Hodess, “These economic and material dimensions of worker power only tell part of the story. A narrow focus on these dimensions without consideration of the broader social and historical forces shaping the terrain of struggle in the industry leads to an overestimation of possibilities and the underestimation of challenges”. (Presentation at Historical Materialism Conference, London November 2018) Fox-Hodess, who worked for the ILWU as an organizer before beginning her academic career, forces us to remember that social and political context can lead to very different results in the class struggle. I have often made this point by suggesting that while dockworkers in Singapore may have a very similar structural power at a choke point node in the economy to their counterparts in Durban in 2008 or Oakland in 1984 for that matter, their ability to act is limited by a military dictatorship and the possibility of extreme physical repression.

At 221 pages Cole’s book is a very worthwhile read. It taps a lot of exciting scholarship and oral histories to make some important observations in addition to those mentioned above. Six chapters unfold his story of the fight for racial justice in both ports, the struggles around automation and international solidarity actions. The book relies heavily on secondary and tertiary sources because most of the original combatants are deceased. As with many treatments of the ILWU it tends to highlight, but not uncritically, the glorious history. In fairness to Cole he does not pretend to make prognostications or give strategic guidance for the future, although such guidance is latent in the history of the union. That is why I found very telling the quote from Clash front man Joe Strummer that Cole uses in the opening of his concluding chapter: “The Future is Unwritten” This is the title of an album that Strummer and his band did, and the title of a movie about Strummer made in 2007 three years after his death. How does the union’s history help us to write that new history? This new history would be a new course of action that can overcome the union’s increasing isolation on the docks and the existential challenge of automation.

History as a Guide to Action

The early leaders of the ILWU recognized that their docker power was not an island. Seeing that their work was interconnected with warehousing that often took place right across the Embarcadero they conducted the famed “March Inland” of 1934-38 that is well documented in Harvey Schwartz’s book The March Inland: Origins of the ILWU Warehouse Division which is mentioned in Cole’s volume. This “March Inland” resulted in the union covering its strategic flanks along the supply chain, and it resulted in creating a warehouse Local 6 whose numbers rose to 20,000 in the early 50’s far outnumbering Local 10 and the longshore division. This local and its numerical superiority meant that the International Secretary Treasurer of the Union until very recently was elected out of the Warehouse ranks. It also rooted the ILWU in the broader working class preventing if from being an isolated aristocracy of “Lords of the Docks”. The numbers in the Warehouse Local alone created a presence in the community that meant that Longshore Local 10 was not isolated socially and politically from the broader community but swam in the working class sea. This was also true in the Puget Sound and Los Angeles where Locals 9 and 26 provided an anchor into the broader working class. Interesting to note that the first Latino President of Local 26 was Bert Corona the legendary Chicano leader and founder of Hermandad Mexicana.

No one grasped this lesson more profoundly than Lou Goldblatt, the longtime Secretary Treasurer of the International union who came out of the “March Inland” in the Bay Area. When he was sent to Hawaii to help the organizing effort of the longshoremen there, he observed, “One of the conclusions I reached was that longshoring played a different role in Hawaii than it did on the mainland. Instead of being a general industry of longshoring, in Hawaii longshoring was just a branch of the Big Five (Sugar and pineapple giants like C&H, Dole, Del Monte)”” The docks could not be held without controlling the chain, the flanks. This led to the ILWU’s organization of the thousands of sugar and pineapple workers. When the sugar and pineapple plantations were phased out the new resort hotels were organized by the ILWU using the power of its numbers and its political reach so that the ILWU to this day remains the largest private sector union in Hawaii and a statewide political power. This is political power that sustains whatever actions the 900 long shore workers may take on the docks. Having a union with 25,000 members on the Hawaiian Islands with a total population of one million people means a density that permeates community and politics and makes everything easier especially the new organizing of workers. All the solidarity actions and support for racial justice are grounded in a reality of a broader community that both benefits from docker power but bolsters it and strengthens it.

Employment Trends Away from the Docks

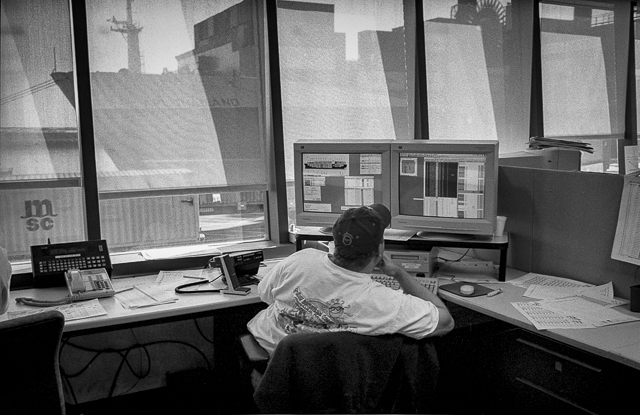

Photo: ©2000 Robert Gumpert

In the glory years of the “March Inland” in the Bay Area the targets were very apparent, often across the Embarcadero in a coffee warehouse or manufacturer or other storage facility or processing plant with geographic proximity to the docks. While the proximity may not be the same the relationship between docker work and inland employment is easily understood. The ILWU is well aware of the studies that have been done by industry observers and academics on the growth of maritime logistics employment away from the waterfront. Nobody has better documented these employment trends than Professor Peter V. Hall at Simon Fraser University. (page 251-252 Choke Points, Pluto Press 2018) He details the massive growth in container traffic through the West Coast ports. In 1980, 2.1 million TEUs were handled in the ports of the West Coast. In 2010, 14.9 million units were handled. This is a 620 percent increase. In this same period of dramatic cargo growth the growth in long shore, or on dock employment, has grown but at nowhere near the rate of cargo trends. It is important to remember that in 1960, prior to the advent of containerization, there were 26,000 longshore workers on the West Coast docks. In 1980 after the establishment of containerization as the dominant mode of cargo movement, there were only 10,245 workers left on the docks. In the period that Hall details from 1980 to 2010, employment grew to only 13,829, a rise of only 35 percent, and puny when compared with the 620 percent increase in production. There is no mystery to this disparity. Containers and massive capital equipment have replaced longshore gangs in the United States and around the world. Before containerization a ship would call for two weeks to be loaded and unloaded. Today the process can take less than 24 hours. While these increases in employment keep pace with regular employment trends, the real job growth action is off dock on the West Coast in three areas:

Photo: ©2000 Robert Gumpert

- Logistics information services: from 1980: 12,816 to 2010: 47,890. This is 274 percent growth. These are information service workers who track the flow of cargo and equipment worldwide. Often they work at inland office centers far from the docks. For example Evergreen, the giant Taiwanese carrier, has a massive information center in Dallas, Texas, far from any port, and purposefully so.

- Warehousing: from 1980: 12,738 to 2010: 86,737. This is 581 percent growth. These are inland warehouses and 3 Party Logistics centers that provide warehouse and order fulfillment services to giant retailers that are clients of the giant carriers that employ dockworkers in the ports.

- Trucking: 1980: 156,808 to 2010: 257,673. This is 64 percent growth. The increases in these off-dock sectors are much more in keeping with the triple-digit increases in cargo volumes. These drivers are often called “owner operators” or “independent contractors,” and therefore their wages and conditions are eroded because they are treated as pieceworkers and paid by the load, especially in short-haul trucking. Many of them, particularly doing short-haul trucking, were once members of the Teamsters. After deregulation on 1981 the Teamsters lost control of this short-haul cargo “drayage” sector.

These growth sectors are the inland flanks of the ILWU, and in order to preserve its power and viability the union must organize these workers and/or assist other unions in doing so. The surprisingly close relationship between Bridges and Teamster leader Jimmy Hoffa was based on a mutual understanding of the linkages between maritime freight and trucking.

Fighting Automation or Growing Union Power?

In Chapter 4 Peter Cole deals with the question of automation. This chapter rehashes the debates around the historic M&M agreement of 1960, and whether it was the right move or not by Bridges. The 1971 strike is studied again as rank and file reaction to the M&M and containerization and steady man provisions that weakened the hiring hall. Bridges is again second guessed for his consideration of a merger with the IBT, although it could be argued that he correctly saw that the ILWU long term could not exist as an island isolated from other workers in the supply chain – like truckers and warehouse workers.

Photo: ©2000 Robert Gumpert

There is only one scant mention by Cole of the Container Freight Station (CFS) supplement of 1969 that was the union’s belated attempt to deal with the issue that haunts the ILWU to this day. The CFS agreement provided that longshoremen would stuff and unstuff the freight from containers, meaning that the work that was formerly being done in the hull of a ship would be done in loading and unloading a container filled with goods for multiple consignees. This work was required to be done union or the employers would be fined $10,000 per container. The language of the CFS agreement provided for a 50-mile radius from the port within which the CFS language would be in effect. This was the Union’s half hearted and ineffectual way of capturing the “functions” that used to be part of loading a traditional cargo ship. The National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) and the Courts have clearly held that this provision is unenforceable, but this continues to be the Union’s feeble and unsuccessful response to a vast increase in inland employment in the supply chain. Nowadays there are not multiple consignees to a container. In the case of Wal-Mart or Amazon they import thousand of containers annually and unload them in third party warehouses or their own distribution centers. This is where there has been massive growth in employment so while the union can bash on dock automation the Employers are running for touchdowns inland.

I played defensive tackle in high school. I was big and strong and loved physical contact. When an opposing player came out to block me I loved to pound the blocker into the turf with sharp blows from my forearms. I was often effective in doing that, but I’ll never forget my defensive line coach rolling an embarrassing bit of game film forward and backwards showing me devastating my immediate opponent but also showing the offensive ball carrier running right by me for a big gain. The coach would say, “Nice job on the blocker Pete, but the point is to tackle the ball carrier.”

This is a good metaphor for the struggle going on now on the West Coast with respect to the marine supply chain. Let’s keep our eye on the ball carrier and the future of the supply chain. It has been amply demonstrated that growth in employment in the marine supply chain for a long time has been away from employment on the docks.

Photo: ©2015 Robert Gumpert

Automation in the Port of Los Angeles

Recently the ILWU has been engaged in a massive battle in the Port of Los Angeles with Maersk over the automation of Pier 400, which will cost the ILWU dozens of jobs and lots of work hours. Powerful mobilizations of the San Pedro/Wilmington community and the workforce have taken place attempting to stop through the political process the introduction of those robots, which were agreed to by the ILWU in a 2008 Memorandum of Understanding with the Pacific Maritime Association, the employers group. The settlement of this battle has resulted in the ILWU getting a commitment from Maersk to fund training for ILWU members to do robot maintenance and repair, pretty much what the union negotiated in 2008. The merits of this settlement can be debated, but two things are clear: The robots are coming, and Maersk has its eye on the ball and its corporate future and is engaged in its own “March Inland”. In a fascinating recent article in the Wall Street Journal Maersk reveals its plans to achieve a company makeover from 80% of their earnings coming from container shipping to “Hopefully a couple of years from now will be much closer to a 50-50 scenario between ocean and non ocean services” Chief Executive Soren Skou says. Maersk already runs 20 warehousing and distribution centers in California, New Jersey, Texas and Georgia. Five of them operate in the Southern California basin.

Maersk realizes that to meet the needs of Wal-Mart and Amazon they need to focus on a streamlined factory-to-store door or warehouse door service. Amazon is already in the Non Vessel Operating Common Carrier (NVOCC) business whereby they buy space on ships for their own use, but also sell unused space to other customers. They could soon contemplate buying and operating their own ocean carriers. Maersk is not alone in this strategic approach. Other major carriers like the French company CMA CGM are engaged in the same strategy extending their employment reach inland. CMA CGM acquired CEVA Logistics in April.

Imagine if the resolution of the dustup in the Port of Los Angeles had been Maersk granting organizing rights to the ILWU in all its subsidiary warehouses and information service centers? This would result in hundreds if not thousands of new members and jobs, and it would solidly root the union beyond the waterfront and in the broader community. Most of these warehouse workers are low wage non-benefited immigrant workers. The rising demographic tide of Southern California would be embraced by the “Lords on the Docks” breaking their political and community isolation from the broader working class of the Southern California basin and establishing a long-term future for the union.

Peter Cole has done us a great service in his comparative history. He has demonstrated that the social and political context of unions is important in determining their course of struggle, and he has highlighted the great impact that dockers have had on social justice struggles.

The future can be written, not by doting on the docks but instead by embracing the ILWU’s history of the “March Inland”. The union must conceptualize itself as a logistics union and move beyond the waterfront to make new history! The survival of the union and its power depend on such a strategy, and the union’s history teaches that.

…

Fighting Trump/Building Socialism

By Luke Elliott-Negri

After Bernie lost the Democratic nomination in 2016, much of the Left felt that it was in a bind. Trump was a proto-fascist nut bag, but Clinton was a neoliberal hack. Many took their line from the liberal commentariat: Trump can’t possibly win (just look at him!). Therefore, the argument went, the Left is under no obligation to campaign against him, and hence for Clinton.

Adoloph Reed Jr., Arun Gupta, and Nelini Stamp were among those on the Left to make passionate public pleas to “support the neoliberal warmonger.”

The labor left, of course, made a clearer calculation. The Communications Workers of America, fresh on the heels of successfully striking Verizon and being the largest trade union to support Bernie Sanders in the presidential primary pivoted to fight Trump, pouring its ample resources into swing state efforts for Clinton. The composition of the courts alone makes the general election fight vital to the labor movement. The Working Families Party and Labor for Bernie did the same.

The effort of course, fell short. Donald Trump has now been our president for three years, and it’s not good.

I find myself constantly torn by how to characterize this administration. Living in a society that has put more people – disproportionately Black – in cages than any other in human history, it’s hard to see Trump as a rupture per se.

But on the other hand, he is a qualitatively different president than any we’ve seen in the past century. I’ve settled on the term “wanna be fascist” to describe him, but I increasingly wonder if I should drop the “wanna be.”

I hardly need to list the behaviors: child separation, concentration camps at the U.S.-Mexico border, U.S. troops used for civilian policing. And the “send her back” hate rallies, leading to death threats of a sitting Congressperson.

Lest we be calmed by Trump’s obvious incompetence, it turns out that Adolph Hitler was incompetent too.

So, what is the Left to do in 2020?