Tijuana truly is a sanctuary city

By Myrna Santiago

This is the fourth and last in our current series “Reflections on The Border”

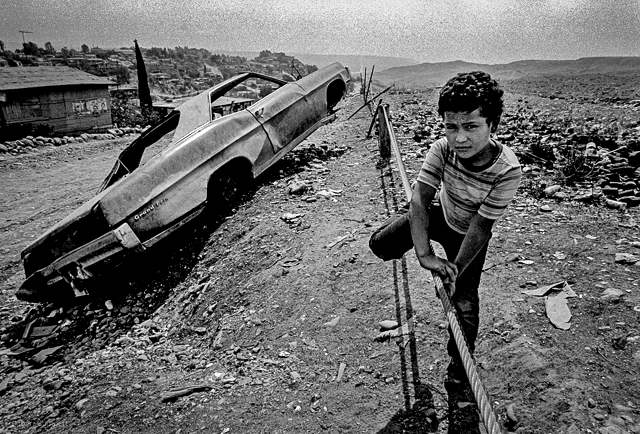

Tijuana was the hometown of my childhood. I was born in the US, but I lived across the border in Tijuana until I was 12 years old. My memories of the city, therefore, are those of a girl: sleeping late because I went to elementary school in the afternoon session, playing with my younger brother and our friends in a dusty yard where not even weeds grew, visiting my aunt and cousins about ten blocks down the neighborhood, enjoying the special aroma of moist earth after the rare first winter rain, feeling sorry for the poor children who lived in cardboard hovels in the dry river channel. We rarely crossed over al otro lado, to the other side, the United States, because immigration officials had refused me entry once, thinking that I was not really a US citizen because I spoke no English even though my mother showed them my US birth certificate. They suspected my mother was smuggling me with a borrowed document and thus they protected the homeland from me and sent me back to where I came from, Tijuana. When I finished sixth grade, my mother decided it was time to migrate for good. As a single mom, she could not afford secondary school for me, so we moved to Los Angeles. After that, visits to Tijuana lasted one day: leaving LA early in the morning, spending the day with my cousins, shopping at one of the supermarkets for our favorite chocolate, cookies, pan dulce, and mole, and returning to East Los late at night when the line to cross did not take hours. I carried that blue US passport and my English was pretty good, so la migra could not keep me outside the country anymore.

Fast forward some twenty-five years later. I return to Tijuana as a professor of history, focused on would-be migrants subject to US immigration policies going from bad to worse, from Obama as the “Deporter-In-Chief” to “Trump the Cruel” who tears families seeking refuge apart and puts the children in cages. And Tijuana is one of the stages where much of this suffering and drama is taking place. Haitians walked to Tijuana from Brazil when their visas to build sports venues ran out in 2016 and they could not return to an island so ravaged by colonialism, earthquakes, hurricanes, and US support for coups and dictators that they ended up in my childhood hometown. Tijuana is home to some 3,000 Haitians now, adding to its diversity, working in restaurants, selling cold agua fresca to motorists waiting for hours to cross the border. The first time I went to Tijuana with a colleague from Saint Mary’s in February 2017 there were signs in restaurant windows along the strip, Avenida Revolución, reading: “Haitians welcome here. Jobs available. Inquire within.” If migrant shelters existed when I was a child, I never knew about them. But now there were two literally around the corner from my elementary school. In 2017 they housed men from southern Mexico heading north and an increasing number of deported Mexicans from California, Oregon, and Washington, not knowing where they were heading, not knowing when they would see the families left behind in the US, not knowing what Mexico meant for them after ten or fifteen years living and working in the US.

But especially bewildered were young men who were my opposite: they were Mexican citizens by birth, but they had grown up in southern California. They spoke no Spanish, but lacking the proper documentation to live in the US, ICE captured them and tossed them over the wall to Tijuana. At my neighborhood shelter there were few people for them to talk to, to pass their wisdom about life in the US, since they shared no language in common. From other deported American Mexicans they heard they had a good shot at getting jobs in Tijuana because they spoke English. The call centers, the American maquiladoras (assembly plants), and the “hospitality industry” all wanted English-speaking employees. The growing foodie scene in Tijuana was eager to test out the restaurant skills deported men brought with them as well. Making some money gave young men hope of finding an attorney who might know enough about immigration law to help them return to their parents, friends, and girlfriends in LA or Orange County. In the meantime, Tijuana welcomed them.

“ICE delivered them to Tijuana–the irony that Tijuana used to be a pleasure center for US servicemen clearly lost in translation.”

Tijuana, too, hosted veterans of the US armed forces who were being deported right and left. They had never had the proper paperwork to live in the US, but the armed forces were happy to take their lives and bodies and deploy them to Iraq, Afghanistan, the war du jour. The service promised them citizenship but never delivered. Instead, ICE ushered them into armored vans if upon their return to civilian life they found the adjustment difficult, slipped, and ended up serving time. When their sentences were done, ICE delivered them to Tijuana–the irony that Tijuana used to be a pleasure center for US servicemen clearly lost in translation. The veterans’ cave in a northern colonia was a slice of Americana: an extra large US flag pinned to the wall, medals and insignia scattered throughout, camo bunk beds, a tight schedule posted on a whiteboard for those staying at “the bunker,” with exercise, prayer or meditation, work, dinner, lights out. Their most pressing demand: access to the VA in San Diego for health care, particularly mental health services. The men were grateful for Tijuana, who honored them with murals painted on the wall that divides both countries and part of the Pacific Ocean at Playas de Tijuana, but they expected the country which they served to take care of them. After all, they had put their lives on the line for the US. Since last fall, 2018, Tijuana has witnessed the arrival of an exodus of biblical proportions from El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala. These are no longer men alone seeking opportunities to send remittances home, but entire families fleeing from unimaginable violence. Tijuana has its share of narco-violence, but it has not become the daily bread for an entire population. Gangs, narcos, paramilitary groups, police, private armies protecting monocrop plantations or cattle ranches—you name it, the Central American countries have all the above in spades. And none of those groups hesitate to kidnap, torture, rape, disappear, and execute men, women, children. So the people flee as far as they can go and Tijuana is the end of the line. There they meet a wall, 30 feet high, with barbed wire on top sometimes. Tijuana does its best to assist. Shelters bring out more cots. Neighbors contribute more diapers. Solidarity groups from San Diego send more clothes. The religious community in Tijuana responds lovingly, asking the citizenry to not give in to donor fatigue, to listen to their hearts, to open up their wallets and donate groceries one more time. They find teachers for the children to learn their ABCs while they await word from the mighty ICE on high. But they are deeply concerned. Local politicians blame the victims, traffickers lurk in wait to exploit the refugees, and corrupt officials try to make a buck off the suffering of the Central Americans. The shelters are terribly overcrowded. A volunteer at a women’s shelter asks, “if the US government carries out the massive deportations it is threatening to do and sends thousands upon thousands of people to Tijuana, where will they stay?” The city is not prepared for them. For now, however, that dusty patch of desert at the farthest northwest corner of Mexico, Tijuana, does not turn away those seeking a manger to lay their babies to rest. My childhood town has indeed grown up in ways it never imagined. Tijuana truly is a sanctuary city. Its people are generous toward the refugees despite their own poverty. That is a story that is yet to be told, a story that merits not only attention but emulation. That all other cities, on both sides of the border, would follow Tijuana’s example.

.

“Open mind, Open heart”

By Nekesha Williams

“This is the third of four in the “Reflections on the Border” a series

“For those migrants that we spoke to, migration was akin to survival.”

Why did I choose to participate in the Migrant Lives Border Immersion (MLBI)? To learn about the lives of migrants on both sides of the border. I wanted to create my own narrative about migrants as I saw it, heard it and hopefully understood it. I didn’t want to be held captive by any type of rhetoric espoused on migration issues specifically regarding individuals from Mexico and Central America. I wanted to see this issue from the perspective of those who are most impacted and those in service of this issue. My personal motto for this trip was “Open mind, Open heart”.

CALIFORNIA, THE AGRICULTURAL STATE

Migrant farm workers are a highly specialized workforce that play a crucial role in the agricultural industry in California. Without them, it would be impossible to sustain this billion-dollar industry that exports produce to various international markets. The increase restrictions on hiring workers that reside outside of the United States have resulted in worker shortages. As a result, there have been cases where acres of crops are lost due to an insufficient workforce during harvest time.

Farm work is hard work as described by a representative at the Monterey County Farm Bureau (MCFB), one of the organizations we visited on the first day of the immersion. Very few natural born Americans seek out this type of employment. Why? Because it is hard work that is performed often times in unfavorable conditions and long hours in the fields. So, why would someone leave their native lands to do this type of work? Because despite the challenges, this “opportunity” is a step forward for many to build a decent life for themselves. One migrant worker we spoke to was asked “From 1-10, how would you rank your life?” His response, “seven”. Why? He has a car and fridge full of food, things he didn’t believe he would be able to attain in his homeland.

CAN WE LIVE? MIGRANTS SOUTH OF THE BORDER

The stories/lives of migrants on both sides of the border are varied, but the one commonality is the desire to build a decent life for themselves and their families.

We had an opportunity to speak with various sojourners in Tijuana that are temporarily housed at shelters. The two stories that stuck with me even after the trip were from two young men. One, in his early 30s and another only 21 years old. Both had made the months long journey to Tijuana. The young man in his early 30s, originally from El Salvador, shared with us that he is a mechanic by trade and once owned a mechanic shop. However, the gangs took his shop. It was unsafe for him to stay there so he left his partner, young son and mother behind to establish himself elsewhere. The 21-year old male, traveled from Guatemala to Tijuana to escape violence as well. In his case, a foreign mining company came into his community sparking protests. Gang members, allegedly hired by the government, came in and killed all those who protested against the company including his uncle, a local pastor.

The Global Witness, a British nonprofit reported that 164 environmental activists were killed in 2018. About 51% of those murders took place in South and Central American countries with Guatemala experiencing a recent surge. The mining (and other extractives) sector is believed to be associated with the highest number of activist deaths.

THE HELPERS

Who are the helpers? I am in awe and also inspired by the work organizations such as Instituto Madre Asunta (IMA) (Editor note: no link provided because a warning of potential security issues comes up – make of that what you will given what the organization does), Casa Del Migrante (CM), and Border Angels (BA) are doing to meet the needs of migrants. The IMA serves primarily women and children. CM, a men’s shelter, has now opened its doors to women and children and provides a wide range of social services in addition to food and shelter. The BA are at the forefront, advocating for human rights and immigration reform, at the US-Mexico Border. Each of these organizations are using what little they have, stretching it to meet the needs of the most.

It is hard work, but each director we have spoken to is fully committed to the people that come to them for help. Sometimes, at the risk of their own lives and well being.

LINGERING CONCERNS

For those migrants that we spoke to, migration was akin to survival. I am concerned about the criminalization of migration for the sake of those who are seeking better circumstances.

Presently, we are witnessing an exodus of people primarily from Central and South America moving northwards in search of a conflict free life, a life that they believe is untenable right now in their native homes. Compounding this present issue with environmental migration as a result of natural disasters and a changing climate, will governments continue to close their borders towards those that are in need? Will those seeking refuge be criminalized?

.

What Does It Look Like To …

By Alicia Rusoja

This is the second in the current series of four reports from the US-Mexico border.

What I witnessed with my colleagues on our visits to shelters and community organizations during our week-long border immersion trip in Tijuana, Mexico, answered the following questions:

What does it look like to regard the life of another human being as you would regard your own life, your loved one’s own life, your child’s, your mother’s, your brother’s?

What does it look like to view your life as dependent on, and interdependent with the life of a stranger, on the life of a child or parent or sibling of another human being?

What does it look like to have respect and admiration for the life and the strength of someone else, a migrant who is willing to put their life on the line in every conceivable way for the sake of their dignity, survival and their family’s ability to be well?

What does it look like to say: “you have the same rights I have, and whatever resources this earth gifts aren’t my own but instead are equally yours and mine”? What does it look like to view earth’s resources, such as land, water, food and shelter, as communal and not as finite things to be owned and used as commodities, controlled only by a few for a few?

Wherever I sleep, you may sleep, whatever I eat you may eat, whatever I have is ours to have. I do not ignore your death, your struggle, your strength. I do not pity you. I put my life on the line as you put yours.

What does it looks like to say and act upon this statement: Your struggle is my struggle: Tu lucha es mi lucha, as my undocumented friend Olivia says.

What I witnessed in the Instituto Madre Asunta shelter, at the Centro del Migrante shelter, at Border Angels shelter, at Dreamers Moms and Deported Veterans bunker, at Ollin Cali’s tour of the housing, labor and environmental violations experienced everyday by migrants working at maquiladoras (transnational corporations’ factories) in Tijuana, answered all the questions I note above. The immersion nourished in me deep heartbreak and awe for all the ways in which people in Tijuana everyday defy the hegemonic imperialistic capitalist discourse of scarcity and individualism.

Trump has forced migrants aiming to make a life in the U.S. to remain in Mexico and from there follow an unofficial, unregulated, metering system where migrants are assigned numbers that correspond with their place in a months-long waiting line to obtain a U.S. immigration court date. Trump also threatened Mexico with tariffs if it does not ensure a reduction in the number of migrants crossing into the U.S. Forcing migrants to remain in Mexico and follow this unregulated and unofficial metering system known for its corrupt practices (where migrants pay Mexican officials between $700-1000 USD per person to be moved up the list) has directly led to shelters reconfiguring their practices and capacities. Places, like Casa del Migrante, which traditionally have only sheltered single men now accept fathers and even mothers with their young children. They also now offer support to migrants for finding work and rented housing in Tijuana, as well as for applying for permanent residency in Mexico, understanding that most migrants will have to overstay the very short-term humanitarian/migrant visas Mexico now gives out to migrants since waiting for their turn to speak to a U.S. immigration judge through the metering system always takes more than the 40-90 days these humanitarian visas are valid for. We met migrants in early July 2019 whose numbers in the metering system were not expected to come up until October 2019 or even until March 2020. Trump’s pressure on Mexico to completely stop migration into the U.S. has led the Mexican government to choose to completely cut funding for migrant shelters. Lack of funding has caused the closing of many shelters we were told. Against all odds, and defying Trump’s and the Mexican government’s goals, many shelters remain open, with migrants, volunteers, and community members ensuring they work.

Border Angels, a volunteer-run organization supporting the functioning of many smaller unfunded shelters (in churches and other non-registered places), including one of their own, told us of dozens of shelters functioning informally with volunteers (including migrants themselves) doing everything they can do provide migrants with shelter, food, and clothing, without a formal infrastructure.

At Border Angels, we learned of an ongoing practice by the Mexican military: walking around Tijuana asking anyone close to the border wall, including Border Angels staff, for identification papers (which would show whether or not they are migrants and whether they have overstayed Mexican humanitarian visas and are due for deportation), targeting pro-migrant Mexican activists, threatening to take them away for their activism. The Mexican military multiple times has come knocking on the door of the Border Angels shelter to check the papers of those inside, essentially aiming to conduct raids (completely over stepping their role) to decrease the number of migrants waiting to immigrate to the U.S. We learned of Mexican and U.S. citizen volunteers refusing to show their papers to military, refusing to let the military enter the shelters to criminalize migrants.

“Their t-shirts said: “have you seen my child?” or “have you seen my mother?”.

Dreamers Mothers, a group that partners closely with Deported Veterans, has successfully supported deported mothers living in Tijuana, through grassroots fundraising to hire lawyers to fight custody cases in the U.S. With immense support, some of the mothers have been able to appear in their custody cases by video using Skype (though this isn’t being allowed anymore by courts in the U.S.) and win their ability to remain in contact with their children (having “visitation rights” by phone, for example) even while remaining deported. We heard of cases of deported mothers who do not know where their children are now in the U.S. because the government put their children in foster care and never respected their legal right as the children’s parents, of deported mothers whose partners denied them the right to speak to their children for years (one for over 15 years!), of deported mothers who are now processing U-Visa cases because they were victims of a crime (including kidnaping and rape) in the U.S. and aided authorities in solving such crime yet purposefully were not told they qualified for U-Visas. We were told by the founder of Dreamers Mothers that when we meet children in the U.S. whose mothers have been deported to please given them a big hug and tell them their mothers love them and are fighting to be able to see them again. This was really heart breaking. Their t-shirts said: “have you seen my child?” or “have you seen my mother?”.

Yolanda, the founder of Dreamers Mothers talked to us about art-based healing workshops she and others are co-facilitating to help the migrant children process the trauma they are experiencing, including separation or imminent separation from their mothers and/or fathers. She told us in great detail about puppetry workshop she had just come back from and how very hard it had been for the adult facilitators to prepare migrant children to be separated (in past, now, and most likely in the future if allowed to cross into the U.S.) from their parents.

Through these stories and our witnessing, we saw how the city of Tijuana and its inhabitants (migrants and Mexicans alike) have maintained a pro-immigrant & welcoming stance, continuing to shelter and care for migrants even when the Mexican government has taken away funds to run shelters, when prevalent stigma portrays migrants and deportees as “criminals” who deserve violence, when here and across the world politicians argue that “receiving” cities are full, that there aren’t “enough” resources for everyone.

Tijuana’s inhabitants’ approach to sheltering and caring for immigrants made me consider what it would really mean for all cities to offer sanctuary to migrants, to challenge the capitalist, imperialist and oppressive idea that one’s worth only comes from one’s ability to produce capital. We saw people stretching and sharing all resources; demonstrating humanity and hope are fiercer than the hegemonic discourse and practice of imperialism, xenophobia and the criminalization of life.

.

Border Immersion Reflection

By Zahra Ahmed, Assistant Professor of Politics

In July, eight professors from Saint Mary’s College traveled to the San Diego – Tijuana border on a fact-finding mission to learn about the migration crisis on the border first-hand. Over the course of five days, the group met with multiple organizations and had the opportunity to meet with migrants themselves at several shelters. This project lives out Saint Mary’s College’s commitment to social justice, providing the opportunity for its faculty to go deep into issues of contemporary importance. Four of the participants have written short reflections about their experience on the border, which The Stansbury Forum will feature over the next few weeks. Here is the first one.

When I visited the US-Mexico border as part of St. Mary’s College’s Migrant Lives immersion program, I expected to encounter suffering and chaos. Given the actions of the current presidential administration, which are designed to denigrate and dehumanize immigrants, I expected the migrants I encountered and the people who work with them to be immobilized by the repeating and continuing traumas they have encountered. The horrible stereotypes perpetuated by the current President and his underlings, the violence perpetuated by the state as well as individuals acting out their hatred, the inhumane family separation policy which continues to be enforced despite claims to the contrary – I expected the knowledge of these conditions to permeate the lives and experiences of the migrants I met. However, that was not the case. One of my lasting impressions from this experience was actually a feeling that migrants and refugees as well as their allies and advocates are stronger and more resilient than I gave them credit for.

The migrants I talked with in the camps of the Central Valley and in the shelters in Tijuana had experienced multiple traumas ranging from family members hurt or killed in their home countries to deportation and separation from loved ones in the U.S. The migrants in the Central Valley live hard lives, working essentially from sun up to sun down. The refugees in Tijuana had either been deported from the U.S. or they had recently made it to Tijuana as they fled violence and political repression in their home countries. Yet everyone I encountered had quick and easy smiles, optimistic spirits, and a belief that we can create a more just society. This was especially true of those who work to help migrants and refugees on the Mexico side of the border.

“She spoke about the increasing number of migrant and refugee men who, due to family separation policies and other factors, are now travelling alone with their children”

When we visited Casa Del Migrante (a men’s shelter in Tijuana) and Centro Madre Asunta (a women’s shelter right next door), the two women we met who run these facilities showed a clear and strong commitment to addressing the needs of their communities. Valeria, the administrator at Casa Del Migrante, told us that they had recently changed their policies to allow men travelling with children to stay in the shelter. She spoke about the increasing number of migrant and refugee men who, due to family separation policies and other factors, are now travelling alone with their children. Although this change drastically increased the number of migrants and refugees they needed to serve, they recognized that these men were in need of resources, so they adapted the facility to meet the needs of men and children.

Both Valeria and Hermana Salome, the Catholic Sister who runs Centro Madre Asunta, told us that the local government had recently made drastic cuts to the social safety net system, which affected all of the shelters in Tijuana. Many shelters had to close their doors. But Valeria and Hermana Salome also told us that other shelters responded to the cuts by relying more on one another and forming networks to share resources and advocate to restore the funding to the government’s budget. Their passion and their commitment to working with those who came to their doors needing help in the face of diminished state support was inspirational to me.

I also felt connected to the mission and the work of the Border Angels, a non-profit organization with chapters in both the U.S. and Mexico. I was introduced to this organization through the Migrant Lives immersion program, and I came to admire the organization’s focus on migrant rights, immigration reform, and prevention of deaths along the U.S.-Mexico border. During our trip, we talked with the Co-Directors of their Tijuana office, Hugo and Gaba, who shared the beautiful and painful experiences they’d had while attempting to help migrants and refugees. Gaba told us about her amazing photography project that she created while living with refugees for several months at one of the camps. As she talked, she showed us photos of some of the people she lived with intending to document their stories. Some of the people in the photos had died, either from violence in the camps or from violence when they returned to their home countries. I was honored to listen to Gaba’s reflections about them and her experience in the camps.

Hugo also shared stories of his work helping refugees and deportees. When they deport individuals, the U.S. government drops people off in the middle of the night at an undisclosed location. They are dropped off with no clothes other than what they are wearing, no supplies, and no connections with any social support systems to help them survive and figure out their next steps. Hugo told us how he followed the busses to find out where deportees were being dropped off and then connected with them to share information about services and resources available to them. He told us about being picked up by the police and beaten because of his work helping and advocating for migrants and refugees. He even mentioned that he’d had to go to the hospital after one of the beatings and it took him several months to recover. He told us that he is still traumatized and he feels fear and anxiety now whenever he sees the police. And yet, with his next breath, he told us about how he plans to expand the resources offered by the Border Angels by creating a shelter as well as a social entrepreneurship in the form of a cafe where migrants and refugees can make music, create spoken word poetry, photography, and other art forms as a means of healing and advocacy. Gaba termed this activity “artivism” and both she and Hugo seemed energized by the thought of feeding creativity among the migrant population.

My experience with the Migrant Lives border immersion program was transformative because it allowed me to see first-hand what migrants and refugees are enduring in California’s Central Valley as well as at the US-Mexico border. It also served as a reminder that all human beings are deserving of love, respect, and to be treated with dignity. Valeria, Hermana Salome, Hugo, and Gaba showed me that, as long as we remember this truth and commit to demonstrating it in whatever professions or fields we represent, we will transcend this crisis with our morals and our humanity intact.

.

In a Time of Disparity a Teacher Reflects on community and an encompassing union

By Heath Madom

“are you willing to fight for [someone] who you don’t even know as much as you’re willing to fight for yourself?” Bernie Sanders

1.

A few months ago, one of my former students F, who is now a Senior, came by my classroom before school to ask for help in deciphering some legal documents that had been served on his family. Their landlord, it seems, is trying to evict them because their apartment, if renovated and put back on the market, could be leased out to new tenants for triple the current rent. Over the course of that morning, and many others since, I’ve been doing what little I can to support F through what can only be described as a deeply traumatizing experience: Referring him to legal and housing resources, talking him through his anxiety and panic attacks, letting him just sit in my room and cry. After he exits my room and goes off to class, trying to pretend like he cares about his schoolwork when his family might, at any moment, end up out on the street, I often feel like hurling a chair through my classroom windows.

2.

The homelessness crisis in Oakland and beyond just seems to be getting worse and worse. Tent cities have become so common they’re now a normalized part of the landscape. I drive past one every day on my way to school, and it seems to grow larger and larger with each passing week. The injustice of people living in such brute poverty amidst the staggering wealth of the Bay Area fills my chest with an anger I can’t quite fully describe. Still, all I can do as I cruise by in my car is clench my jaw and tighten my fingers around the steering wheel.

3.

In the months and weeks leading up to the Oakland teachers strike, I would often ask myself how we might make the dual crises of homelessness and housing affordability part of our campaign, how we might transform our struggle for better schools into something bigger, something that encompassed everything that should be done to make our society decent and just and right. Whenever I looked through my car window at the homeless encampment’s rows of tents near the high school where I teach, the logic of uniting their struggle with our struggle made perfect sense. Yet when it came to the question of how to actually make that happen, the logic grew murky. I just couldn’t imagine how it would work. I was familiar with the concept of Bargaining for the Common Good from my time working in organized labor; but upon any amount of sustained reflection, the idea of teachers making demands around affordable housing struck me as, at best, a flight of fancy. Because even if we could solve the difficulty of adding in new bargaining demands at the eleventh hour, demands for which we had laid no groundwork, we still faced the problem that everyone was already at capacity trying to prepare for the strike. Getting our own house in order meant we didn’t have the time or energy to advocate for our brothers and sisters living on the streets. As the strike drew nearer and the logistics of preparing for it took up more and more of my own bandwidth, the idea of making affordable housing part of our platform of demands receded from my mind.

Fast forward a few months: the Oakland strike is over, but news spreads that Chicago Teachers are preparing to strike. I read an article from In These Times and am astounded to learn (though not really surprised) that CTU, ever in the vanguard, has done the very thing I had merely daydreamed about: they made affordable housing a major demand of their contract campaign. From a historical perspective, it was not groundbreaking. As Rebecca Burns notes in her subsequent article about the aftermath of the CTU strike, unions have a long history of fighting for laws and policies that benefit the entire working class. It’s why phrases like “Unions, the folks who brought you the weekend” exist in the public consciousness. In the modern era, however, such visionary leadership has been rare. CTU’s extraordinary push for rent control and affordable housing has opened the door to a more ambitious agenda for us all as we move forward.

4.

On Saturday, October 19th, Bernie Sanders was endorsed by Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez at a mass rally in Queens, NY. He ended his speech to the 26,000 attendees by asking “are you willing to fight for who you don’t even know as much as you’re willing to fight for yourself?” It was an inspired and inspiring moment that brilliantly framed the question of solidarity in personal terms. In light of Bernie’s speech, an analogous question we could—and should—pose to unions is: are we willing to fight for everyone in our class just as much as we’re willing to fight for our members? If the answer is yes (and I hope it is), then we have to be willing to risk fighting for things that are not directly connected to our working conditions.

Fighting for affordable housing and rent control in Oakland will not be easy. Teachers don’t bargain directly with the Mayor or the City, like they do in Chicago, and the Costa-Hawkins Rental Housing Act of 1995 blocks local jurisdictions in California from passing rent control ordinances. But as the Chicago experience once again demonstrates, it’s not always about winning in the short term. While CTU did not make tangible gains on affordable housing and rent control more broadly (the major gain on this front appears to be a commitment from Chicago to hire more counselors to address the needs of homeless students) they were able to shift the conversation and lay the groundwork for broader change on housing affordability in the future. All because they had the courage to dispense with the traditional approach to bargaining and instead do what they believed was necessary and right.

We can do the same here in Oakland, where the housing crisis is just as dire and also at the top of people’s minds. As public school educators who witness the damage wrought by the housing crisis every single day, we owe it to ourselves to do so. We also owe it to the casualties of the system who are forced to sleep in tents just blocks from newly constructed luxury condominiums. And most of all, we owe it to our students, people like F, who cannot be expected to learn, let alone flourish in the long term, if they don’t have a stable place to live.

.

Do images of dangerous prison labor expose exploitation or build a myth of boot-strapping redemption?

By Pete Brook

In recent years, there’s been a noticeable uptick in stories about California prisoner-firefighters–features by Bloomberg Businessweek, The Guardian, The Marshall Project and New York Times Magazine among others. Besides a dramatic increase in the number of fires, the uptick can be attributed to the convergence of factors–prison administrators providing journalists with broader access, editors responding to increased public interest in criminal justice (reform), and photographers sating their own curiosity.

For the most part, the photographs in these features reset common assumptions about incarcerated people and reveal elements of this lesser-known strand of modern-day servitude. Absent bars, cells, and razor wire, it’s not immediately obvious that these images depict prisoners. In boots, overalls, and gloves, men and women traipse along hillsides and forested trails. They carry picks, chainsaws, and hose lines. They move through dust, smoke, and shafts of golden-hour light. They are cast as heroes. Make no mistake: for the lands they save and the risks they take, they are heroes.

In one respect, the photographs can be read as redemption in action; prisoners doggedly pursuing self-worth and making sacrifices for the greater good. A hero narrative is always seductive but it can also mislead or allow for complacency. Might this new breed of representations distract us from the reality of the tortured conditions in which hundreds of thousands of other U.S. prisoners exist? If these prisoners are heroes, they must be empowered, no? If they are represented as dignified and productive, can’t only good come of these images? If they are not under the yoke of constant surveillance, are they not somehow free, or freer, than they were?

Prisoner-firefighters account for 2% of the California state prison population. Might the recent prevalence of photographs of this minority skew our perceptions and distract us from the gross abuses, waste, and failings of the prison industrial complex?

Brian Frank’s documentary work uses a mixture of candid portraits and work scenes, relying heavily on grain and an earthen palette to evoke grime, smell, and haze. By comparison, Peter Bohler’s images are shot under clear ocean blue skies that make the orange uniforms pop. Both Frank and Bohler shot crews damping remains or cutting fire-breaks; no raging fire in either’s portfolio. The muddied faces of Frank’s subjects are reminiscent of Don McCullin’s portraits of soldiers, or Earl Dotter’s images of Appalachian miners. By contrast, Bohler’s magazine-y approach turns the women into pin-ups. One lounges in the dirt beside her chainsaw, peering over cocked tinted sunglasses. Another stands against a pink backdrop of flame retardant–covered brush. It looks like a constructed set.

Bohler’s pristine composition of four women meditating, eyes closed, in the lotus position, sits in stark contrast to the baggy, slouching, slumbering men during downtime in Frank’s photos. Bohler raises up his subjects by affording them editorial photography’s best treatment, lighting, and concern, whereas Frank raises up his subjects by baking in the caked-on dirt and sweat. Both photographers turn their subjects into heroes; they just get there by different means.

It is understandable that Americans–who live within a racist, economically violent, and traumatic social reality–might seek solace in images of useful, nonviolent, and pro-social correctional conditions. But the truth is that no other nation in the history of humankind has imprisoned more citizens during peacetime. Over the past 40 years, the U.S. prison system has exploded from approximately 400,000 prisoners to 2.2 million. Men, women, and children are sent down for longer sentences under harsher laws that have come to define America’s shameful failed experiment in mass incarceration. Prisons offer scant and irregular access to rehabilitation and education. They disproportionately warehouse people of color. The vast majority of U.S. prisons are overcrowded. While characterized by very occasional spikes in serious violence, more often prisons are sites of boredom and trashed potential.

Serving time at a fire camp is better than doing time in any of California’s other state prisons. Comparably “the conservation camps are bastions of civility,” wrote Jaime Lowe for the New York Times. “They are less violent and offer more space. They smell of eucalyptus, the ocean, fresh blooms. They provide barbecue areas for families who visit […] They have woodworking areas, softball fields, and libraries full of donated mysteries and romance novels.”

Bohler’s image of prisoners practicing yoga and Frank’s images of TV and card games speak to this relative freedom. But it is possible to acknowledge the benefits of the fire camp’s relaxed living culture while simultaneously rejecting the wretched economics of the work culture. Mobilized out of 30 CDCR fire camps, 3,700 prisoner-firefighters are paid 32 cents per hour ($2.56 per day) and $1 per hour when they work the fire-lines. They also get 2 days of their time for each day on the job. The number of workers spikes each wildfire season. As our climate crisis advances, drier weather patterns extend, and blazes grow more severe, prison labor will take up more of the fight against fire. CDCR estimates that the fire camp program saves California taxpayers $100 million a year. Arizona, Nevada, Georgia, and Wyoming also use prison labor to fight fire, but no state relies on prisoners as much as California. Continuously on call, prisoner-firefighters are a virtually irreplaceable resource in the Golden State.

Philip Montgomery’s work falls between that of Frank and Bohler. Montgomery captures action among the broken, charred ground but also secures a couple of formal-ish shots of men gazing toward the camera. All of Montgomery’s images are shot at night, and his subjects–rendered either by harsh flash or by digital sensor in muddy lowlight–stare into the dark beyond. If fire is not the prisoners’ backdrop, we know they are on the move, headed toward more flames. Like Bohler, Montgomery channels the fashion-magazine aesthetic, but his on-the-fly portraits always point toward the work the prisoners have completed and the work to which they’ll return.

Frank’s work is gritty, Montgomery’s is stylized, and Bohler’s is sexy. Tim Hussin’s photographs, which are the most recent, forgo any color theorizing and cast the damaged landscape in wider gray scale drama. If Robert Adams were to photograph fire abatement, it might look something like this. Perhaps Hussin deliberately moved away from the textured chromatic work of those who went before.

There are a few contradictory ways in which Bohler, Frank, Hussin and Montgomery’s images may function: Firstly, the state, by furnishing press access, pushes a soft propaganda of a purposeful prison system; secondly, activists, by opposing the prison industrial complex, adopt these images for didactic, targeted, anti-state messaging; and thirdly, the public may salve its conscience with easy-to-stomach images and convince itself that prisons aren’t too bad, prisoners get a fair shake, and we needn’t be concerned. But prisons are bad. And we should be concerned.

My inquiry is cautionary and somewhat speculative. I welcome prisoner-firefighter imagery, but I’d like to see it offset by raw footage of prisons’ tedium, manipulations, assaults and stresses. (Since this writing, there has been a large public debate about the ethics of publishing prison images of extreme violence.)

Each firefighting prisoner in these photos—through luck, will, coercion or a combination of the three—are seen, if only momentarily, as more than his or her worst mistake. Most prisoners are not afforded the perverse opportunity to work for slave wages in order to rehabilitate their lives and their image. Most prisoners are not seen. Most prisoners do not have the chance to work beyond the panoptic prison space. These prisoners working for pennies on the dollar in the great outdoors are outliers. We must applaud their labor but condemn the apparatus it serves. We must see them as individuals outside both the norm and the prison walls. Going forward, we must demand to see the many individuals inside the walls, too.

.

Originally published as ‘Fire Inside’ in Propeller Magazine #3 (The Propaganda Issue) put out by Helice in Lisbon, Portugal Thanks to editor Sofia Silva and to photographers Peter Bohler, Brian Frank and Tim Hussin.

“The Moment Was Now” Needs Wheels!

By Peter Olney

Actors are Julia Nixon, Ari Jacobson, Darryl! LC Moch and Jenna Stein. Photo: Sean Scheidt

I was lucky enough to be in Baltimore, Maryland on September 13 for the opening of Gene Bruskin’s new musical play, “The Moment Was Now”. Maryland Council 3 of the American Federation of State County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) had bought the house at Emmanuel Church on Cathedral Avenue where the play debuted for two weekends. This old staid Episcopal chapel built in 1854 was filled with a toe tapping, largely African American audience, members of AFSCME. The Moment’s message of the struggle for racial solidarity based on recognizing difference and fighting inequality was a great anti-dote to the President’s recent disgusting attacks on Baltimore. It felt good to be there and share in Bruskin’s triumph. I had previously interviewed Gene about his latest work here on the Stansbury Forum

But I have to confess that when I check out the work of a dear friend and comrade who ventures into the arts of writing or drama, I have a certain amount of trepidation. What if I don’t like the work? What do I say given my high respect for their work as an organizer and agitator? I have known Bruskin since Boston in the 70’s when he was organizing bus drivers during the Busing crisis. I know of his work in labor organizing at the giant Smithfield packing plant in Tar Heel North Carolina and as one of the co-conveners of US Labor Against the War (USLAW) after the Bush invasion of Iraq. He could have retired quietly with those signature achievements and ruminated on a sunny beach in Florida. Not Gene Bruskin. I read and saw his first musical play, “Pray for the Dead” about morgue workers who organize. It was humorous and entertaining. But “The Moment Was Now” is in another league, humorous, entertaining, inspiring but oh so topical and, as it name suggests, a perfect political fit for the moment and Trump’s presidency.

It is 1869 during reconstruction in Baltimore. Frederick Douglas convenes a fictional meeting of four historical figures who all have real links to that city:

William Sylvis – The white leader of the National Labor Union (NLU)

Isaac Myers (also spelled Meyers) – Black leader of a black shipyard workers union in Baltimore and founder of a National Labor Union for people of color.

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper – a Black woman and prominent abolitionist and suffragette who was a poet and the first published Black woman novelist.

Susan B. Anthony – Famous suffragette and abolitionist.

The drama unfolds as these four figures discuss, in rhyming verse taken from their actual written remarks and in powerful song, the prospects for multiracial unity and gender equality. It is noted that while William Sylvis himself supports multi-racial unity and equality his National Labor Union has excluded black people from their convention. Susan B. Anthony supports equal rights for black people but because women are excluded from suffrage she opposes the 15th Amendment. Hovering over all these discussions is the menacing figure of Jay Gould the robber baron who is played skillfully by LeCount Holmes in a giant paper mache mask. Holmes also portrays Frederick Douglas.

The musical numbers are catchy with lyrics that don’t fade. “I Want it All”, “Does Your We Include Me?” and “Women Hold Up Half the Sky!” are three of the most memorable. So memorable that a union railroad worker told Bruskin in the aftermath of the second nights’ production that he attended with his wife that, “My wife won’t let me forget that “women hold up half the sky” I have been hearing it from her ever since we saw your play.”

All the actors are excellent, but the show stealer is Julia Nixon who portrays Frances Harper. A couple of her numbers are adventures in the power of Black gospel with her range and stage presence just knocking those numbers out of the proverbial park.

Bruskin is daring to take a form that is often culturally foreign to the working class and use it to convey a powerful political message. This is “Hamilton” with left politics although Lin Manuel Miranda is to be commended for his outspoken defense of Puerto Rico against the attacks and ignorance of Donald J. Trump. While the play is conceived and directed by Bruskin, it is a collaborative effort with able director and actor Darryl! LC Mooch, musical director Glenn Pearson and Chester Burke assistant musical director.

Unlike “Hamilton” Bruskin will need some help to get this play on wheels and out to venues all over the country. Bruskin is a union man who believes in paying scale to his performers and staff so this can’t be done on the cheap. Check out the video of the most recent production and contribute to the production of more “Moments”.

For a more extensive review of “The Moment” see Mike Miller’s review in Social policy.

.

The Irishman Cometh: Teamster History Hits The Big Screen (Again)

By Steve Early

When I was working with the Teamster reform movement forty years ago, truck drivers concerned about union corruption had to proceed warily.

In the late 1970s, too many affiliates of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters (IBT) were run by grifters or autocrats of the usual business union sort. If you crossed them, the result might be collusion with management to get you fired and then blacklisted.

In other locals and joint councils, located in areas of organized crime strength, some Teamster officials were actual associates of the mob. Their reputation for violent retaliation against union rebels, who dared to challenge Teamster corruption and racketeering, was even more intimidating.

Frank Sheeran, a 6-foot-4, 250-pound Teamster official in Delaware was definitely in the latter category. After serving in heavy World War II combat, he became a loan shark and mob muscle man, truck driver and labor organizer, and ultimately a convicted felon who served 15 years in federal prison.

Sheeran was once little-known outside of Teamster circles. But then former prosecutor Charles Brandt published a book about his close relationship with Teamster President James R. Hoffa, linking Sheeran to America’s most famous cold case, the disappearance and presumed murder of Hoffa in 1975.

Entitled “I Heard You Paint Houses”, Brandt’s biography was optioned by director Martin Scorsese, who has now made The Irishman, Hollywood’s third major film about Hoffa and the Teamsters. It opens in theatres on Nov. 1 and on Netflix later in the month.

Teamster History Retold

The two earlier Hoffa films were F.I.S.T., a lightly fictionalized account of his career starring Sylvester Stallone, and Hoffa, a 1992 production featuring Jack Nicholson in the title role. Both did well at the box office, while recycling Hoffa’s own factually-challenged explanation for Teamster-mob connections (namely, that workers needed organized crime muscle to overcome management violence against them during organizing drives).

The Irishman has a similar Teamster history narrative; it’s already being hailed, by reviewers, as a “majestic Mob epic” and a candidate for multiple Oscars. According to the New York Times, Scorsese’s latest is “long and dark: long like a novel by Dostoyevsky or Dreiser, dark like a painting by Rembrandt.” The Atlantic calls the $160 million film “a ruminative and rueful viewing experience…an attempt to understand a man who lived in the background of history while apparently having significant influence over it.”

With Al Pacino playing Hoffa and Robert DeNiro in the role of Sheeran, the latter is about to become a far better-known U.S. labor figure. I first learned more about Sheeran during a furtive 1977 meeting with two Teamsters who belonged to Local 326 in Wilmington, Delaware. A decade earlier, Hoffa had personally installed Sheeran as president of this 3,000-member local to reward him for helping the IBT maintain control over Teamsters Local 107 in Philadelphia.

During the late 1950s and early 1960s, many truck drivers in Philly opposed Hoffa’s heavy-handed rule. After the IBT was expelled from the AFL-CIO for corruption in 1957, thousands of them tried to replace the Teamsters with a federation-backed union but failed to win a decertification election.

In Sheeran’s view, this challenge to Hoffa was tantamount to treason. “Once you allow dissension and rebel factions to exist you are on the way to losing your union,” he told his biographer. “You can have only one boss. You can have helpers. But you can’t have nine guys trying to run a local. If you did, the employer would make side deals and split the union.”

As the Local 326 dissidents I met with confirmed, Sheeran was quite adept at making “side deals” himself, as the “boss” of Local 326. Like many other members of the Professional Drivers Council (PROD) and the Teamsters for a Democratic Union (TDU), they sought legal help and organizing advice about reforming the union and ridding it of crooks and gangsters. They suspected, rightly as it turned out, that Sheeran was on the take.

For example, as Sheeran later confessed to Brandt, he liked to grant “waivers” to newly organized trucking companies so they could avoid making pension fund payments normally required under a first contract. This enabled a friendly employer “to put his savings on the table [so] you both share it under the table—and everybody’s taken care of that way.”

Thanks to driver complaints, related lawsuits, and investigative reporting by the Wall Street Journal, we also knew, by 1977, that Sheeran was negotiating sweetheart contracts that undercut the Teamsters’ National Master Freight Agreement (NMFA) in much more damaging fashion.

A Labor Leasing Scam

The NMFA was, at the time, one of the biggest industry-wide union contracts in the country, covering 450,000 Teamsters, including members of Local 326. Its signatories included both inter-state freight haulers then regulated as common carriers and “private carriers” as well.

A private carrier was a retail store chain or manufacturer with a sufficiently high volume of shipping to employ Teamster drivers directly and maintain its own fleet of trucks. Rather than try to keep these employers under the NMFA, some Teamster locals like Sheeran’s encouraged them to use a labor broker named Eugene Boffa, Sr..

Boffa and his son owned labor leasing firms that supplied drivers for big companies like Avon Products, Iowa Beef, Continental Can, Crown Zellerbach, and J.C. Penney. Boffa’s contracts with Local 326 and other Teamster affiliates allowed him to provide pay and benefits far below NMFA standards and shed Teamster drivers as direct employees. At Iowa Beef, then the nation’s largest meat packer, a cut-rate agreement between Boffa and the Teamsters required no pension fund contributions at all and paid drivers 70% less than the NMFA rate.

Outsourcing appealed to Teamster employers forty years ago for the same reason that management likes “flexible hiring” arrangements today. As Journal reporter Jonathan Kwitny wrote, “workers regarded by the company as troublesome can be dumped regardless of legal justification. And a company that hires Mr. Boffa can expect freedom from grievances, picket lines, and bothersome Teamster business agents.”

When Teamster drivers protested this lack of representation, the vocal ones—like PROD member Don Harper—got fired. “These two companies framed me because I was a shop steward,” Harper told me. “I was only doing my job trying to get them to honor our contract.”

Sheeran, meanwhile, was riding high in a Boffa-supplied Lincoln Continental, while enjoying other perks as well. His longtime mob godfather, Russell Buffalino also benefited from being “connected with the two major labor leasing companies that had been allowed by the union to prosper,” according to Steve Brill, author of a best-selling 1978 book called The Teamsters. As Boffa told the WSJ: “I am not averse to doing people favors.”

Rank-and-File Whistle Blowing

PROD tried to blow the whistle on Boffa, Sheeran, and Buffalino in our national rank-and-file newspaper read by thousands of Teamsters. “IBT Freight Workers Sold Out By Deals With Labor Broker, “our front-page headlined screamed. While reform candidates backed by PROD or TDU (which later merged) were able to oust incumbents in other locals, Frank Sheeran was forced out for years later, only after being convicted of labor racketeering, mail fraud, obstruction of justice, and taking bribes from an employer.

At age 61, Sheeran’s prior luck–in beating two labor-related manslaughter raps–had clearly run out. He was sentenced to 32 years in federal prison. Buffalino, the Pennsylvania Mafia don played by Joe Pesci in The Irishman, also spent his dotage in jail, after being convicted of extortion and conspiracy to murder. As recounted in the movie, Hoffa’s own 13-year sentence for jury tampering and pension fund fraud was cut in half by Republican President Richard Nixon, in return for Teamster political backing (before Nixon left office in disgrace over the Watergate scandal).

During most of Hoffa’s time in federal prison, he remained Teamster president, while also collecting salaries for four lesser union positions. When he finally retired as part of his White House commutation deal, he cashed out of the Teamster officers’ pension plan with a lump sum of $1.7 million (in 1971 dollars!). Teamster dues money was also spent on the enormous cost of defending him in multiple criminal cases. As a Teamster retiree, out on parole, Hoffa immediately began plotting his return to power, a fatal move because his longtime mob allies were not in favor of it.

Meanwhile, Hoffa’s major collective bargaining achievement–the National Master Freight Agreement—was on the road to ruin. Today, it covers only 50,000 drivers and loading dock workers. De-regulation of interstate trucking, under President Jimmy Carter, did far more damage to the NMFA than any corrupt scheming by Teamster locals that became “mobbed up,” with Hoffa’s help during his rise to power or under his presidency. But Sheeran-style “sweetheart contracts” definitely helped undermine freight industry labor standards.

Hoffa also created a top-down union structure that still concentrates enormous power and privilege in the hands of the Teamster president. That man is now Hoffa’s son, a 78-year old union lawyer from Detroit, who makes about $400,000 a year. Last fall, he decreed that national contracts covering 260,000 UPS workers were ratified even though a majority of the members voting on them rejected the unpopular settlement he negotiated. (For details, see https://jacobinmag.com/2018/10/ups-contract-rejection-james-hoffa-hybrid-drivers)

TDU members have jousted with “Junior Hoffa” throughout his 20 years in office, in many other bargaining situations where IBT leaders similarly failed to mount an effective contract campaign, thwarted strike action, and then “settled short.” Says TDU co-founder and former national organizer Ken Paff: “The idea that the Teamsters belongs more to the top officials than its working members is a legacy of the mob era that we continue to struggle against today.”

The Untold Story

The deadly feuds and personal betrayals recounted in Scorsese’s 3 and ½ hour film took place during the union’s scandal scarred heyday, when Teamster clout could have been used for many good purposes, like improving truck driver safety.

Once again, Hollywood fails to show how Teamster members were the most betrayed in that era—by lax contract enforcement, frequent violations of the Landrum-Griffin Act, outlandish Central States pension fund fraud, the looting of local union treasuries, and corrupt but perfectly legal practices that persist to this very day (like Hoffa’s awarding of multiple salaries to already over-paid full-time Teamster officials to secure their political support).

Also missing from The Irishman is any hint that threats, intimidation, and physical violence failed to deter the development of a Teamster reform movement, which is still alive and kicking today. That singular organizational achievement will be on display in Chicago, Nov. 1-3, when several hundred leaders and activists from TDU chapters around the country gather for their 44th annual strategy session on union democracy and reform struggles in the IBT.

In 1996, a low-budget independent film called Mother Trucker: The Diana Kilmury Story showed what it was like to be part of this brave rebel band during TDU’s early years, when repression by the Teamster officialdom was particularly intense.(It’s viewable, in its entirety, at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6ljgFnp3tC4 ) DSA member Dan Labotz’s 1990 book, Rank-and-File Rebellion covers much of the same historical terrain, as does his essay in Rebel Rank-and-File: Labor Militancy and Revolt from Below During the 1970s (Verso,2010)

Forty years ago, most Teamsters cared far more about their own working conditions and union representation than who killed Jimmy Hoffa in a mob plot to prevent his political comeback. The same is true today, when the only Hoffa many Teamsters know about is the son of the one went missing.

Nevertheless, that unsolved mystery has long been a subject of mass media fascination and looms large again in The Irishman. Viewers should remember that the mob influence, once present in America’s largest private sector union, manifested itself in far more ways than a former leader’s disappearance. And it was always most malign in its impact on rank-and-file Teamsters, who need leaders they can trust and a labor organization they can control.

.

From Yellow Green to Yellow Red! Italian Politics in Turbulence

By Nicola Benvenuti

Try as I might to comprehend the turbulence in Italian politics at the end of August, I was confused. So I asked my dear friend Nicola Benvenuti of Florence to clarify things. He wrote this piece in mid-September, but it took all my Italian chops and several back and forths with Nicola to get a worthy translation. Sorry for the delay, but it remains timely nevertheless. – Peter Olney

.

After his party’s victory in the European elections with 34% of the vote (from 17,4% in the previous national election of 2018), Matteo Salvini, secretary of Lega, was in a hurry to convert these results into greater domestic parliamentary power. He had achieved this success as Interior Minister of the “yellow-green” government (Five Star Movement (M5S) + Lega) thanks above all to anti-immigrant propaganda, a security policy that played on people’s fears and his ability to establish a direct emotional connection with Italians. So he provoked a government crisis hoping for early elections; but this proved to be a fatal error. The M5S had fallen from 32.7% in the Italian elections of 2018 to 17.1 in the European ones, and therefore had the opposite problem and wanted to avoid new elections. This made the party willing to seek an alliance with its archenemy, the Partito Democratico (PD), the second party in Parliament at 19%. Salvini was therefore a victim of his own political arrogance and of the populistic policy that made him forget that in a democratic regime it is the Parliament that decrees the need to call new elections and not those who at that time have the support of the masses! For his mistake he was excluded from the government.

“… thus was born the “yellow red” government M5S-PD”

It was the former secretary of the Democratic Party (PD) and former Prime Minister, Matteo Renzi, who took advantage of the situation promptly, even bypassing his party secretary with an interview in the newspaper La Repubblica that called it a crime against democracy not to take the opportunity to stop Salvini’s rise! The party could only follow him (agreeing to vote for a populist and anti-political measure to decrease the number of parliamentarians as proposed by the M5S): thus was born the “yellow red” government M5S-PD.

The first thing that was striking was the international favor that greeted the new Italian government. Europe was relieved to see the removal from Italian government of Matteo Salvini, one of the best known “sovranisti”. (Term for right wing-nationalists in Europe who denounce the loss of “sovreignity” of the national government because of the intrusion of foreign strong powers – e.g. EU Commission). The “sovranisti” were defeated in the recent European elections but not in Italy though, where they virtually became the first party. But they are still a significant force and likely to regain momentum if European policy continues to prove incapable of true integration, and incapable of correcting the growing national, economical and social divisions of recent years. The prudence of other European “sovranisti” such as the Hungarian Orban who did not openly take the field against the EU, and on the inextricable mess created by the Tory leader Boris Johnson in the management of Brexit, has reduced the appeal of anti-Europeanism.

President Trump himself, who looked favorably on Salvini’s anti-European policy, changed his attitude because of Salvini’s open sympathy for Putin’s Russia as a political model. Russia was suspected of supporting with fake news and targeted messages the popularity of the Lega in recent years. These suspicions are supported by the revelation of negotiations in the Metropol Hotel in Moscow for a large bribe to Salvini’s party in exchange for a contract for the supply of oil to Italy. This was revealed by the US social media/news site Buzzfeed and is currently being brought to the attention of the Italian judiciary.

The “yellow red” government, however, has also raised displeasure on the left. Some on the left would have preferred to go to elections given the collapse, as reflected in the polls, of the M5S from 32.7% in 2018 to below 20% opening the possibility that the PD would be able to recover the many voters who had defected to the M5S. However in the Italian situation that has seen the disappearance of the center (Berlusconi’s Forza Italia has lost most of its voters to the Lega), the moderate electorate would have been pushed, according to the polls, towards the Lega and only in part towards the PD. The Lega would surely have suffered negative repercussions because of the mistakes of its leader but as the polls seem to confirm, it would not have lost significant support. But then if the Lega had, as Salvini asked with anti-democratic and threatening tones, “full powers” to get rid of the M5S constraints on its program, Italian democracy could have been in danger; in any case a spiral of political uncertainty would have been created with very uncertain results. Furthermore, the elections would have blocked the approval of urgent and non-postponable economic measures, including the Budget Law.

“ … A new climate seems to be emerging in the EU that could be a prelude to greater collaboration in the management of the flow of immigrants and”

Doubts have existed and continue to exist over the competence, but above all over the political reliability, of the M5S. All the more considering the very sharp tensions that have characterized relations between the M5S and PD dating back to the origins of Five Star led by comedian Beppe Grillo. Regardless of historical tensions the M5S has every interest in not letting this government fail on pain of its own disappearance from the political scene. Furthermore, it seems credible that a new political orientation of the M5S has been developed in its approach to the EU, directed by Prime Minister Conte (purposefully chosen again as the head of the new government) during the negotiations to support the Italian economic position; an approach that culminated in the support of the M5S for the election of Ursula Von der Leyen as President of the European Commission: those votes proved to be decisive for her election.

This evolution explains why the Italian Paolo Gentiloni (PD) was assigned the Presidency of the crucial Economic Commission of the European Parliament, after another Italian, David Sassoli (PD) was elected President of the European Parliament. A new climate seems to be emerging in the EU that could be a prelude to greater collaboration in the management of the flow of immigrants and in the design of an expansive economic policy (obstinately opposed by Germany, but to which Germany itself may have to agree to).

However difficult, the program of the new government may have a future. But not so fast! On September 17 Matteo Renzi left the PD accusing the current management of the party of stale and losing policies. He is setting up a new formation with the deputies of the PD who follow him, to be named “Italia Viva”. He also maintains that his new formation will support the Giuseppe Conte government and that it would only participate in the elections when the legislature ends. Renzi’s intention seems to be to occupy a vacant political center due first to the successes of Salvini’s right-wing (which in the polls would drain the centrist party Forza Italia), and the radicalization of the left position of the PD which the decimated M5S has accentuated in their attempt to stand up to the League. His group will have about 30 PD deputies and probably will be enlarged by deputies from the Forza Italia area. Italia Viva is therefore in existence only as a formation born to condition the “yellow red” government effectively making Renzi the determining force in Italian politics.

This reminds us, from the point of view of the left, that the common thread that characterizes Italian political uncertainty of this decade is the crisis of the main force of the left, the Democratic Party born only in 2007 from the merger between the Left Democrats (DS) heirs of the Partito Comunista Italiano and the Margherita, heir of the left wing of the Christian Democrats. The new party experienced a new deal: following the primaries won by Matteo Renzi, the “scrapper” of the leadership group with roots in the PCI; the party then suffered in 2017 the split of some former leaders from the DS, which led to the birth of Liberi E Uguali (LEU), a formation that, far from picking up the votes of the old DS party, remained barely qualified to be in parliament with just over 3%. Since then the policy of the Democratic Party has focused on exhausting discussions between political currents pro or contra Renzi. It has revealed itself incapable of speaking to Italian society and effectively confronting the 5S on the program to revive economic development and support economically weaker classes. Furthermore the PD was slow to realize that after the European elections of 2019, a new climate of collaboration had been established between 5S and EU, and was caught off guard by the crisis of the yellow-green government.

Matteo Renzi, on the other hand, understood this as he demonstrated with his proposal to ally with M5S. But his alleged political ability brings him closer to his right-wing namesake, Matteo Salvini. In fact Matteo Renzi in his propensity for improvised moves motivated by too much self agrandisement resembles the Matteo head of the Lega! Renzi declared in 2016 that if the referendum on Constitutional Law agreed to with the center-right did not pass, he would resign: a clear invitation for those who wanted to resize his role and the reform was rejected. So if Matteo Salvini underestimated parliamentary relations, Matteo Renzi has in the past underestimated the strength of the masses, with the same disastrous results! It would be good to remember it.

…

New California Regulations Strengthen Workers in the Ride Share Industry

By Peter Olney and Rand Wilson

For several decades, corporations have sought to undermine labor rights by turning more employees into “independent” workers, and foregoing any responsibility for paying Social Security, unemployment compensation, workers compensation or other benefits like vacation and sick time. These costs are shifted to workers and eventually to taxpayers as well.

A new California law, Assembly Bill 5 (A.B. 5) reverses this trend, which will have a profound impact on the so-called “gig” economy best exemplified by the ride share companies Uber and Lyft.

A.B. 5, signed into law on September 18 by California Governor Gavin Newsom, codified an earlier decision of the California State Supreme Court that established a simple and clear test for determining whether a worker is an “independent contractor” or an “employee.” The Supreme Court “Dynamex” case established a simple “A, B, C” test:

A. The worker is a contractor if he/she is “free from control and direction of the hiring entity;”

B. The worker is a contractor if he/she “performs work that is outside the usual course of the hiring entity’s business;”

C. The worker must be in an “independently established trade, occupation, or business.”

Under the Dynamex test, drivers for Uber and Lyft are clearly employees and not independent contractors. This decision was welcome news for workers and unions in many other sectors of the economy as well. For example, the Teamsters union has sought to organize the thousands of truck owner-operators who transport ocean containers to and from major U.S. ports. There are over 15,000 drivers in Southern California who service the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach where 40 percent of Pacific Rim traffic comes into the United States. The union and its allies have sought largely unsuccessfully to reclassify these workers as employees. Now the Dynamex decision — and the passage of A.B. 5 — hold out hope that this strategically powerful workforce can be united in unions and finally win collective bargaining rights.

Nowhere was the impending passage of A.B. 5 met with such controversy as in the ride share economy dominated by the two publicly traded behemoths, Uber and Lyft. These worldwide multi-billion dollar companies see Dynamex and the new state law as threats to their business model and their very existence. The ride share giants argue that drivers love the flexibility of choosing to work or not work by simply turning on or off their smart phone “apps.” What they don’t publicize is that many drivers are working 70 hours a week just to make ends meet. After paying their expenses for car maintenance, fuel and leasing, their earnings often fall below the minimum wage.

“Reformers and trade unionists argued that the solution was not to perpetuate child labor, but to organize powerful unions in the coalmines and elsewhere.”

Too many business and labor commentators have accepted the emerging independent contractor employment model as an inevitable feature of technological progress. But while the Uber apps may be wonderful, the “uber” exploitation of workers is unacceptable!

The argument for the preservation of flexibility and the benefits to workers and their families harken back to the opposition to child labor law restrictions in the early part of the twentieth century. It was said that some parents in their desperation to bring in more income aided their children in falsifying documents so that the little ones could work in the coalmines. The earnings from child labor often enabled impoverished families to survive – but at a frightening social cost. Reformers and trade unionists argued that the solution was not to perpetuate child labor, but to organize powerful unions in the coal mines and elsewhere.

Uber and Lyft fought hard to be exempted from the provisions of A.B. 5, arguing that the well-being of their drivers depended on it. Labor leaders from the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) and the Northern California Teamsters opportunistically have sought an agreement with the companies to exempt them from the provisions of A.B. 5.[1]

However, as a result of an heroic grass roots organizing network, that back door deal is dead for now. Rideshare Drivers United (RDU) which represents over 5,000 drivers, fought against the exemptions as a betrayal of the drivers. RDU has led several strikes and job actions in Southern California and has been the most high-profile force in the country organizing at Uber and Lyft. They are aided by some cutting-edge apps of their own that enable drivers to communicate, organize and figure their hourly earnings after expenses.

Fortunately, Lorena Gonzalez, the legislator who authored A.B. 5 is an ex-labor leader who once headed the San Diego Central Labor Council. Gonzalez said of RDU, “Any union that wants to be the voice of ride-share drivers has to be inclusive of that group (RDU) and others.”[2] Assemblywoman Gonzalez understands a fundamental principle of trade unionism: no deals should be made without workers being directly involved in decisions about their work life.

Unfortunately, Governor Newsom appears to be interested in getting a “deal” between the high-tech sector and some unions that will exempt ride share drivers from the newly passed law. He has stacked a newly appointed Commission on the Future of Work with Silicon Valley executives and representatives of the same labor unions that tried to cut a deal with Uber and Lyft prior to the passage of A.B. 5.

The fight over A.B. 5 has revealed significant splits in organized labor. Supporters of a sweet deal with Uber and Lyft are also champions of “sectoral bargaining” — meaning all the corporations in a particular industry would be obligated to negotiate with labor and government representatives to determine pay and working conditions in that sector.

The attempt by these unions to reach a deal with Uber and Lyft deal was wrapped in this vision of sectoral bargaining in the ride share industry. The Italian and other European countries experience with a sectoral approach is often positively cited – without any understanding of how the particular features of sectoral bargaining in these countries arose out of workers’ movements and their struggle for power. The U.S. has had sectoral bargaining in the auto and steel industries, but only after dramatic confrontations with management by thousands of organized workers with General Motors, US Steel, and the other major manufacturers in the 1930s and 40s.

The campaign to reclassify so-called independent contractors as workers is far from over in California. However, an important victory has been won in what will be a long war for dignity and justice for ride share drivers and many other gig economy workers.

.

This piece first appeared in Sinistra Sindicale Numero 14-2019

…

[1] “Reform of the Gig Economy A Wonderful Thing: The California legislature’s passage of rights for gig workers is biggest blow against poverty in years,” By Jay Youngdahl, East Bay Express, September 17, 2019 www.eastbayexpress.com/oakland/reform-of-the-gig-economy-a-wonderful-thing/Content?oid=27574578

[2] “Uber and Lyft Drivers Gain Labor Clout, With Help From an App,” by Noam Scheiber and Kate Conger, New York Times, September 20, 2019 www.nytimes.com/2019/09/20/business/uber-lyft-drivers.html