A Plant Closing War, Viewed From Inside

By Steve Early

Editors Note: The interview historian Myrna Santiago, a Stansbury Forum contributor, and immigrants’ rights specialist Alicia Rusoja have done about the border can be heard here.

.

Last winter, protestors wearing yellow vests commanded center stage in France. Their grassroots challenge to the neoliberal regime of President Emmanuel Macron drew on a long tradition of labor militancy, including factory-closing fights. When these protestors still had blue-collar jobs and belonged to unions, they probably looked a lot more like the red-vest-wearing strikers in At War.

At War, a new movie from Cinema Libre Studio, vividly portrays shop floor resistance to corporate power in small-town France. The dialogue is in French with English subtitles. But the cast is largely actual factory workers. And the film opens with a scene familiar to anyone ever involved in manufacturing union bargaining in the U.S.

A workforce of 1,100 employed in a rural auto parts plant has already agreed to 8 million Euros worth of givebacks to keep the place open. The Agen plant is still profitable but, according to management, no longer globally competitive. So now, the fictional Perrin Industries is terminating its local job protection deal that was the quid pro quo for labor concessions. By order from corporate headquarters in Germany, the factory will be closed and production shifted elsewhere.

Before meeting with the company about this sudden decision, union delegates hold a tense caucus among themselves. There is palpable anger and a sense of betrayal. Their principal shop floor leader is Laurent, played by award-winning French actor Vincent Lindon. Laurent, a fiery speaker, tries to lay down initial ground rules that include “no insulting management.” Instead, he urges everyone to “fight intelligently.”

Bargaining table restraint doesn’t last long when the plant manager informs union negotiators that “it’s not bosses versus workers anymore. It’s all of us together in the same boat.” As Laurent angrily points out, the area around Agen is already an “employment wasteland,” with few new job opportunities. Severance packages are not what the workers want. They intend to fight for the jobs they already have.

The rest of this hyper-realistic film depicts a factory occupation and a public campaign to keep the plant open. Few movies have ever done a better job of capturing the rollercoaster ride of a long strike, plus the look, sound, and feel of local union life, viewed from the inside.

Road Warriors

Among the challenges facing workers in any plant closing fight is getting public officials on their side, even in situations where the employer has benefited from past state subsidies or tax incentives. (“The Constitution protects private enterprise,” one French government envoy primly reminds the Perrin workers.)

The strikers in At War become “road warriors,” a group of roving union activists who travel to seek support and put pressure on targets elsewhere. They confront riot police during a mass demonstration at the Confederation of Industries in Paris. They defy an unfavorable court ruling and send roving pickets to shut down a sister plant 500 miles away. They solicit strike fund donations from other embattled union members. “Hello Perin workers,” says one message of solidarity, arriving at strike headquarters with a check enclosed. “We have the same assholes running our firm.”

Throughout their struggle, they seek a face-to-face meeting with the German CEO of the Dimke Group, the parent company of Perrin, which has decided to close the Agen plant instead of selling it, as the strikers demand. Meanwhile, heated exchanges between worker representatives and their management counterparts continue at the bargaining table, as workers and their families face mounting economic pressure.

Two months into the strike, fissures develop between the various labor organizations represented in the plant—the FO, CGT, and a less militant enterprise union. Laurent discovers that the company unionists, worn out and discouraged, have been side-barring with management about “bumping up the check” (i.e. getting a better severance deal in return for accepting the plant closing).

Laurent and his outspoken ally Melanie accuse their co-workers of “licking the bosses’ boots.” But both face wider doubts about the viability of their strike strategy and leadership. “The plant’s closing down. It’s done,” says Bruno, a bargaining committee member ready to throw in the towel. With police and management protection, Bruno and others take off their strike stickers (which proclaim the unity of “1,100 in Struggle”) and return to work.

A “Quality Dialogue?”

Nevertheless, the struggle briefly takes a brighter turn when Martin Hauser, the German CEO, finally agrees to a meeting mediated by the French ministry of employment. Hauser proves to be a world-class corporate smoothie, fluent in French. He mentions that he has a French mother-in-law and a second home in the French countryside. He welcomes what he calls a “quality dialogue” (of the German labor relations sort).

That “dialogue” deteriorates fast when the Dimke Group dismisses a rival firm’s “unrealistic” offer to buy the Agen plant. “French law requires an owner to look for buyers, but does not require them to accept any offer,” Hauser reminds the trade unionists. In exasperation, the CEO accuses them of “refusing to see market reality,” which he likens to “demanding a whole new world, or living in another world.”

It’s not union negotiators who have the final word in this frustrating exchange. After the meeting an angry crowd of strikers make the evening news by surrounding Hauser’s car and over-turning it. The CEO and two bodyguards emerge bloodied and shaken up. In the ensuing media and political backlash, union members are thrown on the defensive, leading to bitter personal accusations and recriminations.

At War pulls no punches about the personal sacrifices and weighty responsibilities of workers who become strike leaders. This film should be required viewing during union training of shop stewards, local officers, and bargaining committee members.

Cinema Libre Studio wants to reach a much broader audience now that the film has opened in New York, Los Angeles and other cities. It’s looking for labor organizations to sponsor showings to their own members. Let’s hope that some unions take advantage of this offer—because the war on workers, whether in France or the U.S., shows no sign of letting up.

For more information on screening the film before a labor audience, contact Jen Smith at jsmith@cinemalibrestudio.com or 818-588-3033.

…

“Who would agree to sponsor them?”

By Jill Stanton

Update: NYT Business of 31 July, 2019 reports the giant public relations firm Edelman dropped the GEO Group account after employees at the firm objected to the contract. In what is perhaps a “choke point” for this business sector the company was afraid the association would damage the very nature of their business, their “public image”, and hurt their bottom line.

.

“In his one-year odyssey, by plane from Congo to Cuba, to Guyana, and thereafter by bus through the American continents, he had learned Spanish by necessity”

In early June, 2019, I was in San Antonio volunteering with RAICES, the largest pro-bono provider of immigration legal services in Texas. I worked alongside RAICES staff and fellow volunteers assisting immigrants at the Greyhound Bus Station and a nearby immigrant resource center maintained by the San Antonio Interfaith Welcome Coalition with funding from the San Antonio City Council, and at an ICE (Immigration & Customs Enforcement) Detention Center in Karnes.

The work at Karnes was grueling for both volunteers and staff. We would leave San Antonio at 8 AM for the one-hour drive to the rural facility, and would not return until around 9:30 at night. When detention officers had the women immigrants available to be interviewed (sometimes we were forced to wait an hour or more as detention protocol required that we could only see the next person on our visitation list, even though a second or third immigrant was already waiting for us), we worked virtually non-stop to complete as many as 10 intakes and interview preps under the time pressure that if we didn’t get through them all, some women would have their asylum interviews before they understood the process and/or legal representation at their “credible fear” interview could be arranged. On my days at Karnes, I returned to San Antonio with the still unfinished task of summarizing my handwritten case notes, and getting them off to the RAICES staff that would represent the interviewed women as their cases progressed. After a week at Karnes, the more relaxed pace of my work at the bus station was a blessing.

One of the deepest impressions of my two weeks in Texas were of the ebb and flow of the massive migrant crossings, & how migrants of particular nationalities by sharing information on social media and through phone communications, were able to meet & group up at certain border checkpoints despite months of traveling alone, or with family, through multiple south and central American countries. This was particularly the case with a group of about 25 Congolese migrants whom I met at the San Antonio immigrant resource center. I communicated in Spanish with one young man, accompanied by his preteen daughter. In his one-year odyssey, by plane from Congo to Cuba, to Guyana, and thereafter by bus through the American continents, he had learned Spanish by necessity.

Shared information helped the Congolese to get to the same border crossing point, but shared misinformation resulted in their being stuck in San Antonio, hanging out at the resource center by day, & sleeping in a church near the bus station at night. Having no family or friends in the U.S., each had provided ICE with the same “sponsor” information–an agency in Portland, Maine where Congolese granted refugee status had been assisted in the past. But the agency only had a government contract to temporarily house refugees—migrants approved by the USCIS (U.S. Citizenship & Immigration Services) abroad for resettlement–and could not accept these new asylum seekers. Who would agree to sponsor them? Where would they be able to settle? No one knew; everyone was scrabbling.

“Karnes’ 2300 oil wells have polluted the water table to such an extent that they took declarations of immigrant inmates who drank, and showered in the local water, developing skin diseases and illnesses.”

The greatest surprise of my time in Texas was that the largest number of incoming migrant women at Karnes were not the expected Hondurans & other Central Americans, but Cubans. Like the Congolese, their shared information had them arriving in large numbers at particular checkpoints at the Texas border. Their staggering presence was new for the RAICES staff and a question was why now–more than two years after the 1/17 end of the policy that had previously permitted any Cuban who made it to U.S. shores or illegally over the border to apply for permanent residency after just one year here? Most of the Cubans had extended family in the U.S. Were their relatives suggesting, or was word going out through social media that it was now or never? Was political repression in Cuba on the rise? (Most of the incidents of personal persecution related to us were reported by the Cubans as having taken place in the last 6 months.) The Cuban asylum claims were in stark contrast to those of the Central and South Americans, as I will explain further below.

This was the first time I ever did immigration work in a private prison, and that was an unwelcome revelation as well. Karnes Detention Center is one of more than 10 immigrant detention facilities in Texas, and is managed by GEO Group, a Florida- based corporation “specializing in privatized corrections, detentions & mental health” both in the U.S. and abroad. GEO Group was a donor to Trump’s campaign, and the recipient of 1.3 billion in federal contracts during this administration. The single story facility at Karnes, with artificial turf and flowers at its entrance, sits amongst pastures pocketed with small active pump-jack oil wells–and the mansions of the ranchers who own them. A RAICES lawyer tells me that Karnes’ 2300 oil wells have polluted the water table to such an extent that they took declarations of immigrant inmates who drank, and showered in the local water, developing skin diseases and illnesses.

The populations of Karnes and other Texas detention centers shifts with the numbers and composition of the crossing migrants, & the resulting policies and politics of the DHS. When I signed on to volunteer at Karnes 3 months ago, the inmates were fathers and sons; since April, 2019, the facility has only held immigrant women.

In a large room with immovable tables meant for prison visits, RAICES staff and volunteers—law students, lawyers, Spanish linguists, and Spanish-speaking academics–met with women inmates and explained the legal representation RAICES provided to prepare them for their “credible fear interview”—an administrative “Q & A” regarding their asylum claims with a San Antonio Asylum Officer.

We explained that during this interview, while the women would relate intensely personal and often traumatic incidents, they would be alone in a detention room with a telephone to connect them with the USCIS Asylum Officer. A translator would also be engaged by phone. If there was sufficient time between the receipt of their asylum interview notice & their permitted call to RAICES to allow RAICES staff & their partner, Project Corazon, to make arrangements with an attorney who could be present at the day and hour indicated, their legal representation would come via phone as well. However, too often interview notices were delivered only a day, or less, prior to the interview time. We urged the women we spoke with to insist on their legal right to postpone the interview to a future date until they were represented, but many, out of intimidation, impatience, or the misplaced certainty that all that was required to prevail was to tell their compelling history, did not. The transcripts of NCFI’s (negative credible fear interview determinations)—cases where immigrant asylum claims were denied by Asylum Officers—illustrated how confused applicants could get during a difficult interview—so much so that they appeared unresponsive, and therefore “not credible.”

And, And, And …

We were tasked with prepping the women for their credible fear interviews, which required that we help them to understand that asylum could not be granted simply because they or their family members had endured horrific persecution. They had to demonstrate that their fear of persecution was “on account of their race, nationality, religion, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group. And that governmental authorities were unwilling or unable to protect them. And they could not safely relocated elsewhere in their country. Thus, the story of a young Salvadoran woman who fled after an unsuccessful robbery because she absolutely believed that she would be targeted by the surveilling robbers in the future, or a Guatemalan woman receiving a very credible threat of future harm from her sister’s rapist after her sister had fled, was unlikely to ground a successful claim. (Details of any asylum case I relate have been changed to protect client confidentiality.) In discussion, we had to tease out further details–were the persecutors members of a local or national gang, was the woman being targeted because of her indigenous or minority background, were the local or national police force in league with the cartel, & if so, how did they know that?

The contrast between the asylum stories of the two largest nationality groups at Karnes — Hondurans and Cubans— could not have been greater. The Hondurans, and also the Salvadorans and Guatemalans, mostly feared being shot & murdered by gangs who had killed family members & threatened to do the same to them. Some had brought the death certificates of loved ones as proofs, and “denuncias”— police reports of being extorted, recruited, or raped & enslaved by gangs & cartels. Few had a significant chance of winning their cases: political asylum cases based on gang violence are rarely granted. Most fled soon after the receipt of death threats, because even though they may have reported these incidents to police, they were too terrified to remain to wait to see if the police, who were often working with local gangs, such as MS-13 which has a multinational presence, would arrest their gang or cartel persecutors. The Venezuelans were more likely to have accounts where they were targeted because of imputed or actual political opinion (e.g. opposition to the government of President Maduro resulting in the loss of government employment and, repercussions for protest activities–beatings, death threats, kidnappings–by the pro-Maduro vigilantes, known as “collectivos.”

The persecution the Cubans reported was very different. It was, by their account, largely for failure to participate in civic and political activities, or for unsanctioned private businesses, and included baton beatings & detentions by local police, exclusion from government jobs & university courses, and surveillance and harassment by officials of the CDRs (neighborhood-based Committees for the Defense of the Revolution). Unlike the accounts of political opponents in other countries who had participated in mass demonstrations or protests, many of the Cuban accounts of persecution were of personal or family targeting as “counter-revolutionaries” due to having relatives who had escaped to the U.S. or had been detained in a thwarted escape attempt, or due to unsuccessful applications for U.S. visas. The reported acts of persecution were frequently sparked by verbal confrontations with low-level officials such as talking back to CDR officers and police & expressing disgust with unjust accusations of theft or illegal business activities, or by deliberately provocative acts—a dissident’s display of a U.S. flag, party music played during the national mourning period following Castro’s funeral.

The San Antonio Greyhound bus station

The San Antonio Greyhound bus station is where asylum-seekers from Karnes and another detention center in Dilley, Texas, are dropped off by ICE if they pass their “credible fear interviews”. But the majority of the immigrants I see during my two days at the bus station have been brought directly from the CBP (Customs and Border Patrol) outposts on the border. These are parents with young children whom the DHS has decided not to detain for initial asylum interviews in large part because of the humanitarian restrictions placed on the incarceration of minors in a 1997 federal court settlement decision (Flores). However, if there were both a mom and dad with the kids at the border crossing, it is likely that the family was separated, and one of the parents was detained.

If the immigrants had no resources for airline or bus tickets to reach to the cities where sponsors awaited, or if they were waiting for sponsor funds, or as in the case of the large group of Congolese, they had no sponsors, the families hung out by day in the make-shift resource center, run by San Antonio’s Interfaith Welcome Coalition, and if they had no place to go, slept in churches at night.

These families were predominantly Honduran, Guatemalan and Salvadoran. In their backpacks and bagged possessions each family had a clear plastic envelope with ICE paperwork indicating the address of the ICE deportation office where they would report at their destination, as well as the Immigration Court address where their asylum case would be heard. Hopefully, though not always, the ICE office and Immigration Court were located near where they would live with family or friends during what would be at least a year-long asylum process. They process culminates in a final court date where most, if 2018 statistics of an 80% denial rate continued, would likely have their asylum cases denied.

“Sometimes sponsors backed out after being contacted by ICE, leaving families with no place to go.”

Volunteers behind a long counter at the resource center tried to figure out how immigrants could get to their destination by bus or plane. Departures for volunteer rides to the San Antonio airport were posted on white boards behind them, as were the bus schedules for the nearby Greyhound station. Periodically volunteers with bullhorns would come through the two large rooms where migrants were waiting and announce departures. Children were constantly underfoot, many happily playing with new toys or coloring books; others napped on quilts and clothes on the floor. Money, largely coming from a Catholic Charities fund, had to be allocated for tickets for families without funds. Sometimes sponsors backed out after being contacted by ICE, leaving families with no place to go. The wonderful RAICES social worker I worked with was unsuccessful in dissuading a young woman not to go to a home offered by a woman she had met on Facebook, or to convince another woman with a baby not to travel some 1000 miles to the town where a distant relative had stopped answering her calls.

Once immigrants were routed to the Greyhound bus station, the Interfaith Coalition volunteers filled out a form called “la mapa” for them. The map grid explained each bus they needed to take to make it to their destination, and its departure time. Volunteers also provided families with a backpack gift with blankets & packed lunches, as well as stuffed animals & toys for the kids. RAICES volunteers like myself went around with a “pink sheet”; we reviewed ICE paperwork to write down where and when migrants were to report to ICE once at their destination. We also made sure they understood how using an 800 number to find out the date and place of their first Immigration Court hearing. This was especially important because there were mistakes: some folks were going to one place, but had ICE appointments in another state far away. We tried to explain how to try to deal with situations like this, as failure to report to ICE would probably result in their future incarceration. Failure to present themselves at a first Immigration Court hearing would result in an in absentia deportation order. But first we had to break it all down by trying to explain the difference between reporting to ICE ( “la migra, la policia, no son amistades”) and the Immigration Court, where they would have to open up and present the very personal details of their asylum case. Explaining this & other essential information to over-stressed immigrants often with limited education who barely knew the name of the town to which they were headed, had to be overwhelming and bewildering for them.

There is far more to report than I’ve been able to put into these few pages. For instance at Karnes and other Geo-Group facilities immigrants are “permitted” to perform paid work for $1 an hour cleaning the detention facility.

There are too many unanswered questions about what will happen in the future–not least because of the threat of further cutting of government monies for immigrant services and continued privatization of the incarceration system. From what I observed of the young dedicated staff of RAICES (median age late 20’s), that organization despite an enormously successful Facebook Go Fund Me campaign that raised more than $20 million last year, is struggling to provide the amount of legal and logistical support needed by the immigrants to Texas. For instance, to avoid burn-out from 12 hour days at Karnes Detention Center, RAICES lawyers and paralegals are rotated so that none does the trip more than twice weekly, legal volunteers and linguists flesh out RAICES commitment to the detained immigrants to try to assure each is seen, their story heard, and that they receive future legal representation.

Is this sustainable? What will happen in San Antonio when city council funds run out? What if volunteers–either at Karnes and other detention facilities or the bus station and resource center– no longer assist in their present large numbers? What will happen to the immigrants at their destinations when faced with a lack of legal resources to represent them in Immigration Courts in a system where in 2018 98% show up for their immigration hearings but only 20-35% of their asylum applications were granted?

This border saga will continue…..

…

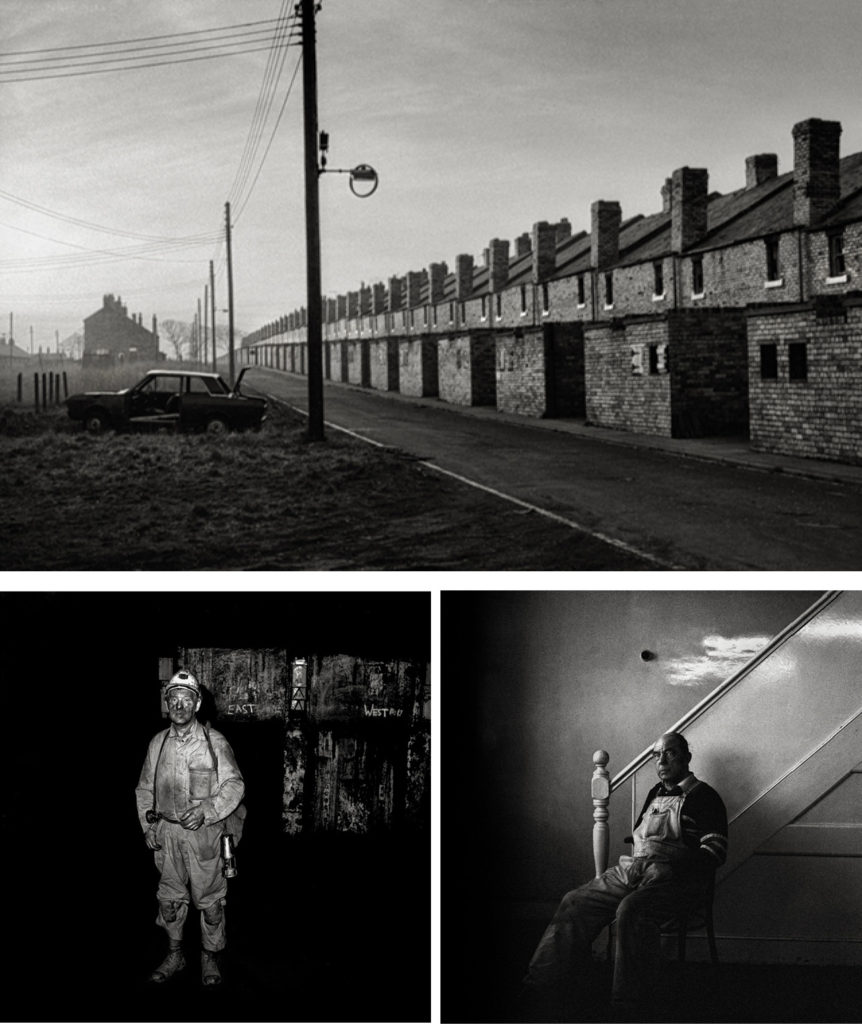

Coal Town

By Mik Critchlow

Editor’s note: Mik Critchlow’s work stopped me cold the first time I saw it. Given that Britain has been a second home for me for the last 31 years and I am both a producer and consumer of images, it buggers the imagination how I failed to know about Mik’s work. All the more so because he has for all that time covered subjects similar to myself. But in fact I didn’t up until about 2 months ago. Mik currently has a Kickstarter campaign for his forthcoming book, ‘Coal Town’ to be published by highly acclaimed documentary photo-book publisher Bluecoat Press. Join me in supporting this book at a very reasonable price by visiting the funding site directly blow.

.

Throughout 42 years of my career as a documentary photographer I have always concentrated my projects on the experience of working class people living in marginalised communities throughout the United Kingdom. It was inevitable really, given that I came from a working class background.

I left high school in 1970 at the age of 15 years without any academic qualifications and went straight into the workplace two days after leaving school, gaining full -time employment as a tailor’s trimmer at a local clothing factory. I immediately joined the trade union and soon became an activist within the factory. I once instigated a one day wildcat strike while there, in support of a fellow worker who had been given the sack by management for complaining about working conditions on the factory floor, he was later reinstated. I didn’t make it full term on my trial employment period and was advised to leave by the management.

From there, I went straight into the Merchant Navy as a cabin boy and worked my way through the ranks to become a Steward/Cook, always active within the National Union of Seamen.

Deciding to leave my life at sea in 1977, I enrolled on two year course at my local College studying Art History and Graphic design as a mature student, I soon became President of the College Union and continued my activism within the education sector. It was while at college that I picked up a camera for the first time and immediately fell in love with the medium and process of photography.

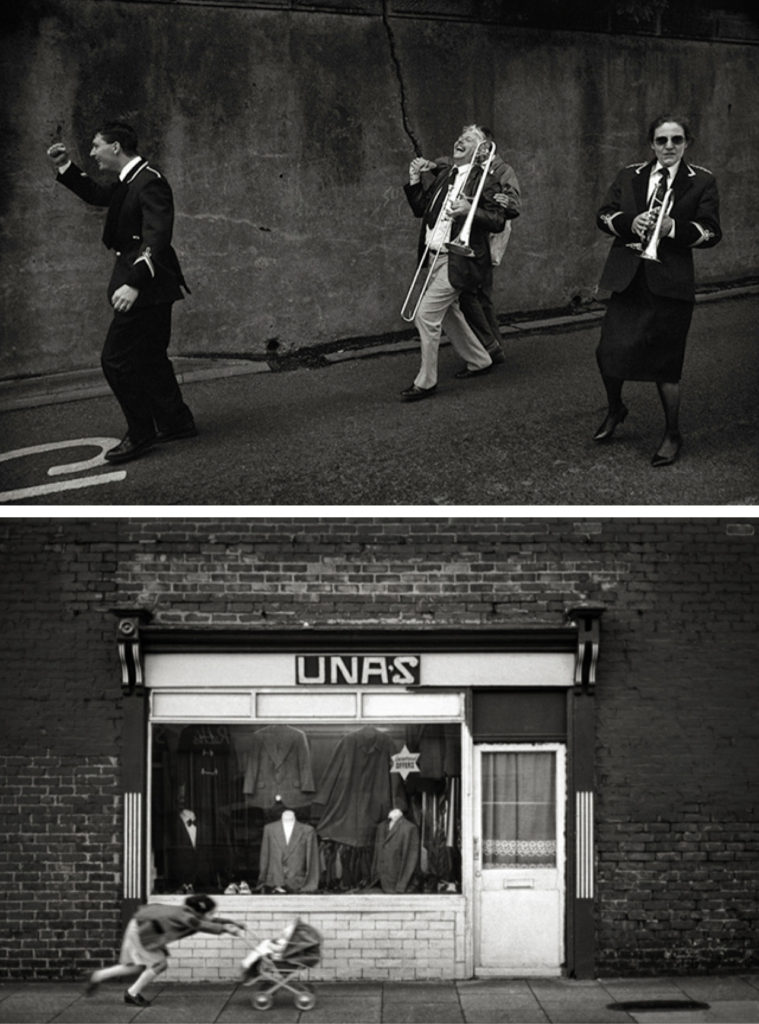

I then began to take photographs in my local area. Everything was beginning to make sense to me in terms of documenting ordinary people within the situations I found myself, I was recording the everyday events and people within my community. Later in 1978 I visited the Side Gallery in Newcastle Upon Tyne who were exhibiting the entire collection of Henri Cartier Bresson’s prints from the V&A Museum. In many ways this was an epiphany to me to continue the work, which I was undertaking. It taught me a great deal about the benchmark for producing a body of work in the wider sense. Shortly after this visit I was awarded an exhibition commission, for a local arts organisation, to develop my earlier work into a more cohesive sequence documenting the lives of people living and working within a mining community. This was continued in 1979 when I received grant funding from Northern Arts (Arts Council of England) to produce more documentary photography work in the area.

Bottom Left: ‘Last Man Out – Last Shift Woodhorn Colliery’ 1981

Bottom Right: ‘Micky Sparrow – Office Cleaner – Woodhorn Colliery’ 1981

Micky was a miner who lost his right arm in an underground accident in the 1960s – promised a job for life on his return to the surface, he was redeployed as a cleaner in the Colliery managers offices. This was to be the last day of his working life as the mine was closed down.

In 1980 I was commissioned by Side Gallery and taken under their wings as a photographer, through this association with Amber/Side I was introduced to Chris Killip, Graham Smith and Sirkka Liisa Konttinen, who were also producing long term projects on the working class communities of the North East of England. They taught me to have faith in the work I was producing and that by being a documentary photographer was a way of life and not just a vocation/job.

Director of Amber Films, the late Murray Martin stated: “Integrate life and work and friendship. Don’t tie yourself to institutions. Live cheaply and you’ll remain free. And, then, do whatever it is that gets you up in the morning”. *

Bottom: ‘Una’s – First Avenue – Ashington’ 1978

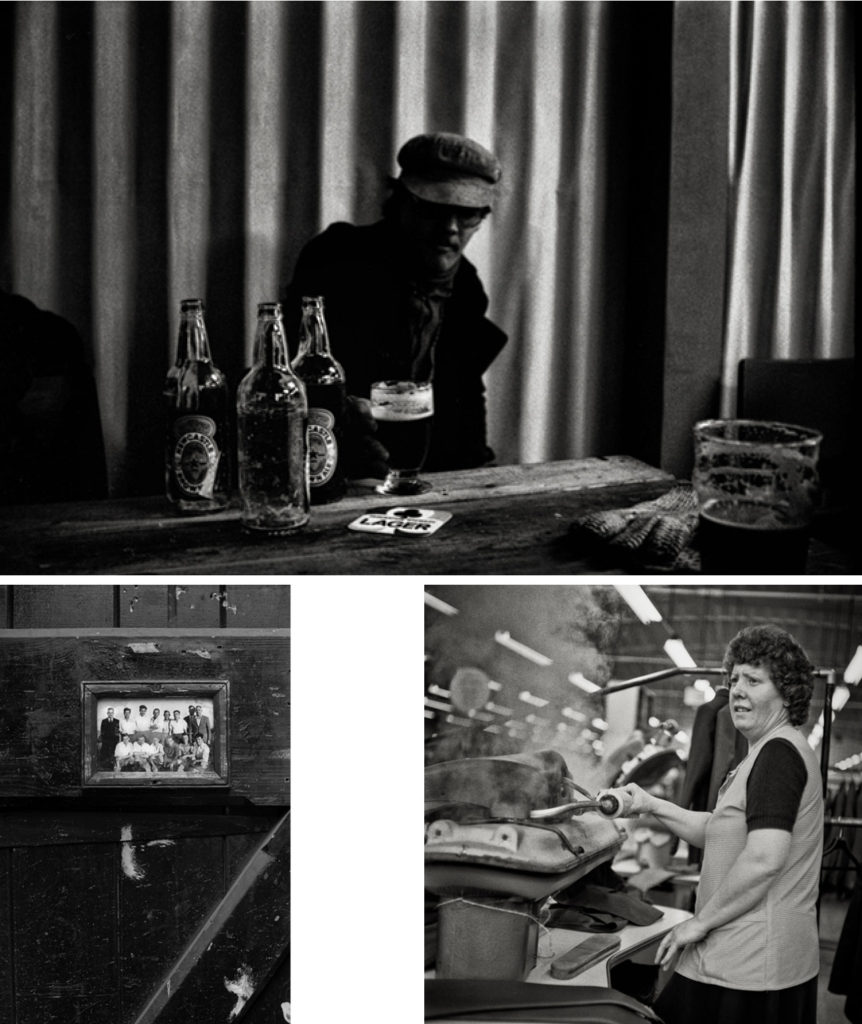

I truly believe that being born and educated in an area gives you a better insight into the lives of people and the environment which you are photographing. Many of the people I photographed were known to me as people with whom I had first-hand knowledge; had met regularly on the streets, went to school with, drank in the same bars and clubs. I was never seen as a threat to their privacy, I was known only as someone who always had a camera. I always made work prints to give to people whom I’d photographed, to continue the relationship further and make other introductions, to enter into other situations/environments that might otherwise have been closed to other photographers who were seen as ‘outsiders’.

I come from a traditional mining family going right back to my Great Great Grandfather who travelled from Cornwall to Staffordshire. My Great Grandfather relocated to Ashington in the 1850’s with his family to begin work in the local mines. It’s a fourth generation thing: my grandfathers, father and my two brothers, as well as my uncles and cousins, have all worked within the coal mining industry. This helped me greatly to gain access to the local collieries and the men and women who worked there. When asked my name I would always be greeted with a smile “I know your Dad/Uncle/Brother”, it helped to break the ice as far as making photographs was concerned, my reasons for being there.

Botoom Left: ‘Detail – Painters and Carpenters Lunch Room’ – Ashington Colliery 1988

A framed photograph of the colliery soccer team from the 1950s. The buildings were later demolished after the closure of the mine.

Bottom Right: ‘Press Operator – Hepworths the Tailors’ Ashington,1979

A long term employer for 800 Ashington women, The factory closed down in the 1990s, new owners of the business moved production to Morrocan factories to maximize profit margins.

People would often ask why I wanted to photograph them; my answer would always be that they were as important to the town’s history as any celebrity sportsman or local politician. I had always wanted to show the town of Ashington in the broadest sense, I would set out to do specific ‘surveys’ in which I would spend a few weeks photographing shopkeepers and trades people around the area. Then I’d move on to factory workers working in a number of the local clothing/engineering factories, and in this way build up a picture of the working lives and environment of the people of Ashington. This was in addition to any of my work in the local collieries at Ashington, Woodhorn, Lynemouth and Ellington. I also wanted to concentrate on leisure activities and traditional pastimes such as my series on whippet dog racing which I did over a twelve month period. This was done at the same time as I was working on paid commissions for trade unions and other projects in the North East of England.

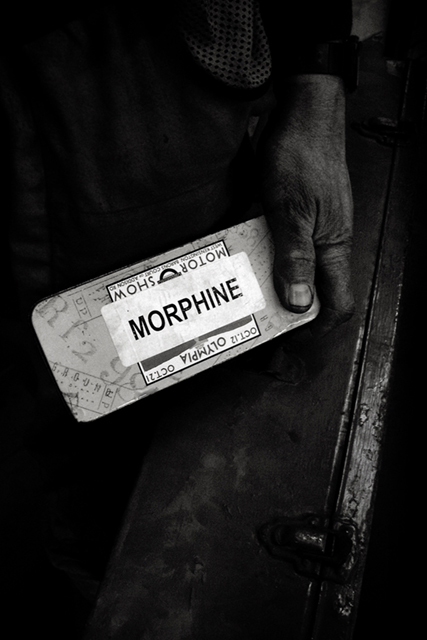

The last working shift at Ellington Colliery, the designated medical first aider carried doses of injectable morphine underground in case of serious accidents. Miners working at Ellington, a coastal mine, worked underground 6 miles out from the shoreline underneath the North Sea.

My work has continued in the intervening years since the demise of the coal mining industries in the area and I have recently completed a series of new images from the neighbourhood where I was born, an area where many of the town’s mining community were housed and is now considered to be one of the most run down and deprived communities in the UK.

This situation is not only specific to my community, but a problem which is widespread amongst many ex-mining communities throughout England Wales and Scotland where the major sources of full-time employment have disappeared without any strategic plan for the future prospects of working class people.

…

*This was part of the original manifesto of the Amber/Side Film/Photography Collective.

The Three Epic Lies that Put Corporate Giants on Top

By Anthony Flaccavento

There’s little doubt that the biggest corporations are on the top, with extraordinary economic and political power in the United States. Levels of corporate concentration in everything from the meat industry to the media are at unprecedented levels; corporate CEOs routinely make two hundred, three hundred times more than their rank and file employees; and the political clout they wield through lobbyists and political donations ensures, as Martin Gilens has shown, that their priorities carry far more weight with elected officials than what the majority of American citizens desire.

Though many people aren’t happy about the current level of corporate dominance, we tend to see it as just a side effect of a global economy that rewards the most innovative and efficient businesses. But it is much more than that.

The truth is that Three Epic Lies, concocted at different times over the past century and a half, have paved the way for this corporate aristocracy we are now living with. In different ways, they’ve been codified in law or risen to become the conventional wisdom, dominating how institutions, academics, politicians and the courts view the limits and responsibilities of corporations in our nation.

Three huge, Epic Lies, each one of profound importance; taken together they’ve made corporate control of our economy and politics almost inevitable. So, let’s take a look, starting with a Supreme Court Clerk more than a hundred years ago.

Number 1: “Corporate Personhood”

In 1881, Leland Stanford was ticked off. California had just passed a tax on property owned by railroad lines and Stanford wasn’t going to let his company, Southern Pacific Railway, pay any more than they had to without a fight. So, he pushed the claim that the new tax was discriminatory because his giant corporation was protected by the 14th Amendment to the US Constitution, enacted in 1868 to establish the personhood of African Americans. This case came to be known as Santa Clara County v Southern Pacific Rail Line (UCLA law professor Adam Winkler details this history in a March 5th, 2018 piece in The Atlantic).

Stanford had friends in high places, including Supreme Court Justice Stephen J Field. In the Santa Clara decision, notes from the Justices’ deliberations show that the high court declined to rule whether or not corporations should be granted ‘personhood’, enraging Justice Field. But no matter. The Court Clerk, JC Bancroft Davis – himself a former Rail Line company president! – wrote in his summary that the Court had decided that “corporations are persons… within the 14th Amendment.” They’d done no such thing, but this was how the decision was characterized. By the court clerk.

A few years later in a separate case, Justice Field stated that corporations are persons, saying that “It was so held in Santa Clara v Southern Pacific Rail Line”. The Court’s clerk had said this, not the Justices; Field knew it, but he ‘cited’ the decision regardless. And courts have been doing so ever since then, building on the logic of “corporate personhood” all the way to the culminating case of Citizens United in 2010. A wealth of legal precedent at the highest level, all founded on a lie. That’s the first Big Lie.

Number 2: “…for the profit of the stockholders”

About four decades later, the second Big Lie was born, arising out of the Michigan Supreme Court’s settling of a dispute between Henry Ford and the Dodge brothers. The latter were shareholders in Ford Motor Company. When they decided to start their own car company, Ford attempted to withhold paying their dividends, as he didn’t want to help capitalize a competitor. Ford Motor Company, which was not publicly traded at that time, argued that they needed the money to lower prices to consumers and pay better wages to their employees (In truth, they had plenty of money for both).

The Michigan Supreme Court sided with Horace and John Dodge, ordering Ford to pay the dividends owed. The court’s official opinion – the “holding” – was quite limited in scope. But in a tangential comment they opined that “…a business corporation is organized and carried on primarily for the profit of the stockholders. The powers of the directors are to be employed for that end.” Tangential observations such as this – mere dicta, they’re called – are neither a necessary part of the court’s ruling, nor are they legal precedent, as Lynn Stout makes clear in her remarkable book, The Shareholder Value Myth. They are musings, a sidebar. Nowadays we might call it a rant.

But guess what? That’s exactly what this sidebar observation from 100 years ago has become: The foundation for the widely held view that publicly owned corporations have the legal duty to maximize returns to shareholders, trumping all other considerations, from employee well-being to environmental stewardship. In fact as Stout observes, “There is no solid legal support for the claim that directors and executives in US public corporations have an enforceable legal duty to maximize shareholder wealth. The idea is fable.” And it’s the second Big Lie.

Giving corporations the rights of people has helped corrupt our politics, making a mockery of “one person, one vote” and enabling similar legal absurdities, such as equating unlimited expenditure of money with unlimited free speech. Insisting that corporations are legally bound to maximize profits – short term profits, no less – above all else has further concentrated wealth and power among a tiny group of investors and CEOs. And it has helped create an economy of collateral damage, to people, communities and the land.

Number 3: “consumer welfare”

But wait, there’s more. One more Big Lie that has greased the skids for corporate dominance of our economy and politics. This one started in the 1960’s, coming to fruition in the 1980’s, the result of the relentless drive of Supreme Court wannabe, Robert Bork. This third Big Lie has pulled the rug out from under anti-trust laws and their enforcement, enabling seemingly endless merger mania and corporate concentration in nearly every sector of our economy.

The Sherman Act of 1890 was the first significant piece of federal legislation to tackle monopolies. Named for Senator John Sherman, the law sought to stem the growing power of Standard Oil Company and other huge “trusts” of that era. It took some time before the federal government began to implement the law, but by the early years of the 20th Century, enforcement led to the break-up of behemoths like Standard Oil, and the preclusion of corporate concentration through mergers and buyouts. This was the norm for the ensuing 70 years, where a consensus held that monopolies were bad for the economy and dangerous for our democracy.

As Tim Wu describes in The Curse of Bigness, Bork set out to re-write history, beginning with his 1966 article, “Legislative Intent and the Policy of the Sherman Act”. In this piece, and his arguments over the next two decades, Bork declared that the original intent of the Sherman Act was simply to protect “consumer welfare” and nothing more. In other words, mergers could be stopped only when it was determined that prices to consumers would likely rise. Bork made the case that this is what Senator Sherman and Congress had intended. But as Wu makes clear, nothing could be further from the truth. In fact, Sherman had spoken of the “inequality of condition, of wealth, and opportunity” that arose from monopolies, stating further they created “a kingly prerogative, inconsistent with our form of government”.

Undaunted by history and truth, Bork pushed on, moving his simplistic argument from the margins of the debate to the Supreme Court, which cited Bork in a 1979 decision declaring that “consumer welfare” was to be the standard by which corporate concentration should be judged. Over time, this new – and false – understanding of Congress’ original intent became the accepted measure by which mergers and monopolies would be judged. Stop them if they will likely raise prices, otherwise there’s nothing the government can do. The third, very Big Lie had prevailed.

The corporate takeover of the US economy and, to a large degree, American politics was not inevitable. Neither was the notion that corporations, which are granted a public charter, after all, are legally obligated to maximize shareholder wealth, subordinating any and all responsibility to the public. We are where we are, rather, because of Three Big Lies that have enabled the extreme concentration of economic and political power that is our status quo. Let’s name those lies – that corporations are people, that their sole purpose is to enrich their shareholders, and that we can’t stop them from getting bigger unless they’ll raise prices – for what they are: false, absurd and un-American. Let’s unravel the misleading claims that gave rise to them, and then let’s fight like hell to take them down and begin to restore our economy and our democracy.

…

The Hidden History of the Arnautoff Mural

By David Bacon

I respect the feelings of the students who testified at the San Francisco Board of Education meeting about the mural at George Washington High School, and their desire to have their communities and histories treated in a respectful way. They deserve, not just respect, but solidarity in fighting the pervasive racism and exploitation in our society. The mural was painted in solidarity with that fight. I think it is a mistake, therefore, to interpret it as a symbol of colonialism, white supremacy and oppression.

The mural was created in 1936 by Victor Arnautoff, a Russian immigrant and a Communist, who painted it as a critique of the racist boosterism that was the way high school history was taught in that era (even when I was in high school in the early 60s). The 1930s were the years when the left and the Communist movement were strong in San Francisco. These were the years of the General Strike of 1934, which broke the color line on the docks – the reason the longshore union created in that strike, Local 10 of the ILWU, is a majority-African American union today. These were the years of the organization of the Chinese Workers Mutual Aid Association in San Francisco, many of whose members belonged to the Communist Party.

Arnautoff

belonged to the Communist Party as well. In

that party African American and white longshore and Chinese laundry and garment

workers and red painters like Arnautoff would have undoubtedly known each other

and talked about the politics they shared. Fighting racism and class

exploitation, and supporting revolutionary movements against imperialism, was

the common ground among those radicals – the basis of their politics. For

an artist like Arnautoff, painting was therefore a political act, a

responsibility to oppose racism and class exploitation in the art he produced.

The mural he painted in the high school was a critique of earlier murals

produced for the Pan American Exposition, an imperialist celebration and

world’s fair on Treasure Island, paid for by San Francisco’s wealthy

elite. That “official” artwork showed California history as the

advance of “civilization” triumphing over “savagery.”

The Admiral Dewey statue in Union Square, celebrating the colonization of the

Philippines, was the same kind of art produced in that earlier era. An

even uglier example is the art shown in the Forbidden Book, a book and

exhibition of racist and imperialist cartoons collected by Abraham Ignacio and

published a few years ago. This is what Arnautoff was reacting

against. When the WPA, that is, the New Deal, began paying unemployed

artists, it meant that artwork could be created that didn’t have to please the

Crockers and other elite San Francisco families, and could therefore tell the

truth about U.S. history. Arnautoff’s murals were a product of that

short-lived political space.

“… when artists believed that art had to take sides with workers and oppressed people, and tell social truth.”

When the mural shows the grey hordes of settlers advancing past the body of a dead Native American, it was a powerful truth for that time, especially because these settlers are being urged onward by George Washington. The school was named for Washington, so Arnautoff’s message to students was to take a hard look at who he was. Showing that the wealth is being produced by Black slaves, for the rich white colonial merchants who owned them, is telling the truth again. It doesn’t glorify slavery – it attacks it, and even more important, it shows who got rich from it. Washington was a plantation slave-owner.

The mural shows Native Americans with arms, which is also a historical truth – that many Native people fought against the American Revolution because they had suffered massacres by the settlers. In this depiction, Arnautoff goes beyond the radical murals of Anton Refregier in the Rincon Annex post office. Refregier shows native people doing the work for a California mission, with the Spanish padre who enslaved them in the background. That in itself contradicted the stereotype of the missions as happy places that brought European religion and culture to native people (for which Father Junipero Serra was recently beatified, when he should have been condemned).

But Arnautoff goes further. He shows native people as active resisters to colonization, in their war-dress, ready to battle the settlers. Such resistance was the key to survival. Indigenous historian Roxanne Dunbar Ortiz, speaking of this resistance in California, says, “Without this resistance, there would be no descendants of the California Native peoples of the area colonized by the Spanish.”

Exposing

the resistance by both slaves and native people to the rebelling colonists in

the American Revolutionary War is not just correcting history, but helps

understand the present. Marxist historian Gerald Horne, in “The

Counter Revolution of 1776”, charges, “Despite

the alleged revolutionary and progressive impulse of 1776, the victors went on

from there to crush indigenous polities, then moved overseas to do something

similar in Hawaii, Cuba, and the Philippines, then unleashed its

counter-revolutionary force in 20th-century Guatemala, Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia,

Indonesia, Angola, South Africa, Iran, Grenada, Nicaragua, and other tortured

sites too numerous to mention.”

Arnautoff painted a critique of George Washington because of that history of

slavery and genocide, so you can imagine how much opposition there was to

it. It was the art of social realism, the same approach to art by artists

in China and the Soviet Union after those revolutions, when artists believed

that art had to take sides with workers and oppressed people, and tell social

truth. Many artists who created socially committed art in the U.S. were

later blacklisted in the 1950s for what was then called “subversive”

art. That kind of art was suppressed – you won’t find it in the San

Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

Arnautoff

belonged to the American Artists Congress, which was put on the Attorney

General’s list of banned Communist/subversive organizations, and the San Francisco

Artists and Writers Union. At the height of the Cold War in the 1950s he

was called before the House Un-American Activities Committee. This was not

long after the Committee sent ten screenwriters to prison for their radical

politics, and the Hollywood blacklist denied work to many more. Arnautoff

had a job teaching art at Stanford University and rightwing politicians tried

to get him fired, which Stanford refused to do. At the end of his life

Arnautoff returned to the Soviet Union, where he continued his work as an

artist, and died in Leningrad.

The school district, which is responsible for the mural, should have taught

students about its politics – who it was defending and who it was

attacking. If the students weren’t aware of this history, it’s in part

because the school district didn’t do its job. Maybe it was afraid of the

work’s radicalism, or simply didn’t know or understand the mural itself. The

left in the Bay Area should also be self-critical for not having talked more

about the mural and its message, helping to make students and their communities

feel like they were being defended, rather than being alienated by the work, as

so many said in their comments to the school board.

But painting over the mural doesn’t redress the historical crime that the mural shows – if anything, it covers up the critique of it, a goal the McCarthyites and their committees were never able to achieve. Painting it over robs the students themselves – of the chance to discover and evaluate for themselves this history of struggle in the arts, of the chance to appreciate progressive art that tells the truth about our history, and of the chance to respond by making art and critiques of their own. If students are critical of Arnautoff himself, and point out blind spots he had, I’m sure he would have liked the idea. He certainly didn’t consider his work some untouchable sacred object, but a tool to move forward the fight against racism and class exploitation, a fight in which he stood up for justice.

…

Company Union 2.0: Is Organized Labor Helping to Unmake the New Deal?

By Dr. Brian Dolber

The passage of the National Labor Relations Act in 1935 not only gave workers the federally protected right to form unions and collectively bargain, it also banned employers from supporting “company unions.”

Company unions had emerged during the reactionary 1920s as part of the so-called “American Plan” to break the power of organized labor. By providing workers with some small benefits that resembled those of trade unions, while not exercising any real power, and promoting loyalty to the employer, these sham organizations would help control and contain militant, democratic movements.

Today, the need for, and potential success of such movements has never been more clear.

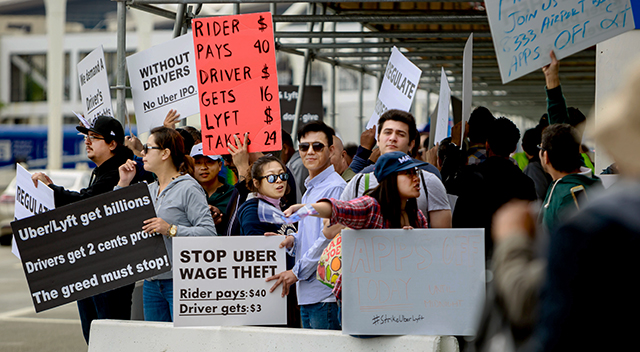

When rideshare giant Uber announced it would cut driver pay rates by 25 percent in Los Angeles, its second largest US market, in March 2019, members of the fledgling Rideshare Drivers United – Los Angeles, knew they had no choice but to take action. Having built a membership of 2,500 drivers over the course of one-and-half years, RDU-LA called a strike for March 25. Members picketed in front of the Uber “Greenlight Hub” office for most of the day, effectively shutting it down. Garnering favorable media coverage and the support of presidential candidates Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, their membership nearly doubled to 5,000 in the next six weeks.

So when the RDU-LA Organizing Committee voted to call a second strike on May 8, they had the ear of the media and more importantly, independent driver-organizations across the country. The strike was soon billed as a National Day of Action, and ultimately went global with protests on every continent. Two days in advance of Uber’s much-hyped IPO on the New York Stock Exchange, the strike was credited with tanking the so-called “unicorn,” and transforming the conversation around the gig economy.

But while such efforts might provide much needed momentum for revitalizing the labor movement, companies like Uber and Lyft are using legal loopholes– classifying workers as independent contractors rather than employees– to constrain worker democracy and revitalize the company union.

While the company union had been a feature of labor’s nadir, the tragedy that the historian David Montgomery termed “the fall of the House of Labor,” it re-emerges today as a farce– Company Union 2.0– developed in partnership with legitimate trade unions.

“That is a legacy no union should want.”

The Uber-funded company union “Independent Drivers Guild” (affiliated with the Machinists) in NYC is the prevailing model. Under this model, labor bureaucrats start by making backroom deals with gig company executives. Companies make minor concessions (like the ability to message drivers and deduct dues through the company app). In exchange, bureaucrats give up the right to strike, the right to collectively bargain, the right to just-cause termination, the right to fight for reclassification– the rights that workers have largely enjoyed, for 80 years.

In the California context, the Dynamex court case and the bill AB5 (Here and Here), which recently passed the Assembly, would grant gig workers all rights guaranteed to employees. This has spurred a handful of business unionists to seek exemptions for Uber/Lyft while giving established labor the right to collect dues and leaving workers with little.

Rideshare Drivers United- Los Angeles and affiliated organizations around the country, are offering an alternative to the IDG model. They have refused to take any resources from Uber and Lyft, or any labor organization that receives such support, and they are allied with the independent, militant NY Taxi Workers Alliance (NYTWA, @NYTWA). The campaign to regulate Uber & Lyft in NYC that NYTWA spearheaded, with the powerful and progressive SEIU 32BJ selflessly playing a supporting role, exemplifies the labor solidarity needed to stare down the gig Goliaths.

RDU-LA has developed a Drivers’ Bill of Rights, democratically voted on by thousands of workers through regular surveys. They want open, worker-led negotiations with the boss, not backroom deals between gig companies and labor bureaucrats. They want bargaining for the common good, helping drivers and the larger communities they service, not just for membership dues. And as they have shown, they can grow their organization by flexing a union’s most powerful muscle– the strike– rather than agreeing to contracts with no-strike clauses without a membership vote.

The demands are clear, but to meet them, gig companies will have to fundamentally alter their business models to make them more fair to workers. And the gig companies know this. That’s why they’re so eager to find willing partners in labor who will sell out drivers to the lowest bidder.

But now is not the time for workers to lower our expectations. If Uber drivers were properly classified, the company would be the largest private employer in the world, just behind the U.S. and Chinese militaries. And the need and potential for organizing rideshare drivers will only increase, as Uber’s IPO prospectus predicts drivers will experience growing dissatisfaction.

To cede this sector to capital’s business unionist partners would not only be a grave missed opportunity for those who are committed to reviving the labor movement; it would set a precedent for other sectors to reclassify workers, effectively voiding some of the most important achievements of the New Deal.

That is a legacy no union should want.

…

Under Guise of “Choice”: Trump Launches D-Day Assault on Veterans’ Care

By Suzanne Gordon and Steve Early

On June 6th, the Trump Administration launched what it calls a “revolution” in veterans’ health care.

If that date rings a bell, it’s because, on June 6, 1944, American soldiers and their allies stormed ashore in Normandy, establishing a critical beach-head in the campaign to defeat Adolph Hitler and Nazism.

In the aftermath of that and other World War II battles, tens of thousands of injured veterans were treated, back home, in a nationwide network of hospitals and clinics run by the federal government. Most patients of what’s now called the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) appreciated the specialized, high-quality care they received from our nation’s best working model of socialized medicine.

But, on this D-Day anniversary, Donald Trump is rolling out a program, favored by his right-wing backers, that directly attacks public provision of veterans’ healthcare. On June 6, the VHA’s salaried care-givers will be required, by law, to refer many more of their nine million patients to private doctors and for-profit hospitals, even when the VHA could serve them better and at lower cost.

This expanded out-sourcing creates a beach-head for the health care industry, which hopes to expand its market share to 40 percent or more of all VHA patients. Trump’s “counter-revolution” in veterans’ care will divert billions of dollars from a national healthcare system uniquely equipped to serve the poor and working-class veterans who qualify for VHA coverage.

Empowered Patients?

In typical Trump fashion, this scheme is being deceptively marketed. On Fox News and other media outlets, White House appointees, like Veterans Affairs Secretary Robert Wilkie, claim that giving veterans greater “choice” will “empower” them as patients. (For more on Wilkie see here.)

“… few realize that, every dollar spent on private sector care will be taken from federal budget allocations for direct care in veterans’ hospitals and community clinics.”

In Wilkie’s rosy scenario, veterans can stick with VHA care, if they want it—but also get the same access to private sector providers that other Americans have through their private insurance, Medicare, or Medicaid coverage.

In reality, the list of “community care” providers hastily assembled since passage of the VA Mission Act last year, includes many with little or no experience treating the complex service-related problems of many veterans. Wait times for appointments outside the VHA will, in many cases, be no shorter than inside—and sometimes longer. Plus, few hospital systems outside the VHA treat mental and physical problems in a systematic, coordinated way—a necessity for veterans whose substance abuse or suicidal thoughts are a product of traumatic brain injuries and chronic pain.

Veterans are not being warned that, if they enroll in private practices for primary care or mental health treatment, they may be dropped from the VHA rolls and find it difficult to get back into the system. And few realize that, every dollar spent on private sector care will be taken from federal budget allocations for direct care in veterans’ hospitals and community clinics.

First starved of resources and then patients as well, more VHA facilities will become targets for down-sizing or closure by the Trump Administration. Where this occurs, it will eliminate the first choice of most veterans and force others to remain outside the VHA system, whether they want to or not. Already, the VHA has more than 40,000 vacancies, which the White House refuses to fill, creating stressful conditions for remaining care-givers, many of whom are paid less than their private sector counterparts.

Anti-Privatization Protests

On June 5, members of the American Federation of Government Employees (AFGE), the largest union of VHA employees, National Nurses United, and Veterans for Peace did their best to blow the whistle on what Senator Jon Tester (D-Montana) now warns may be a public policy “train wreck.” Their “National Day to Save The VA” included protest rallies, press conferences or informational picketing in San Francisco, Portland, San Diego, Long Beach, Milwaukee, Boston, Albuquerque, Tucson, Minneapolis, Rochester, St. Louis, and Las Vegas.

Unfortunately, Tester and almost every other Senate Democrat voted in favor of the VA MISSION Act, which mandates the far wider out-sourcing that begins this month. Only Vermont Independent Bernie Sanders, former chair of the Senate Veterans Affairs Committee, two Democrats and two Republicans voted “No.” In the House, 70 Democrats including Nancy Pelosi opposed MISSION.

But that leaves many other Congressional Democrats who should not be allowed to get away with vague claims that they’re against VA “privatization” when, in fact, most of them went along with Trump’s “bi-partisan” plan to implement it.

As Vietnam veteran and VHA patient Skip Delano points out, “the private sector healthcare system does not have the capability or the capacity to meet the needs of veterans. They will be sent to providers who may know little or nothing about their special problems and may fail to diagnose critical conditions like PTSD, Agent Orange, or burn-pit exposure, or military sexual trauma, to name only a few.”

A former postal worker, coal miner, and New York City teacher, Delano has decades of experience with good, union-negotiated, job-based medical coverage. Nevertheless, he believes that, for many patients pushed out of the VHA, “private sector care will be less veteran-centric, of lower quality, require longer wait times, and end up with many veterans getting lost in the system because of poor care coordination and lack of accountability.”

A key organizer of this week’s Veterans for Peace “Save Our VA” protest in Manhattan, Delano also spends a lot of time reminding his fellow veterans about the need to be labor allies. The Trump Administration is currently seeking major contract concessions from VHA workers, one third of whom are veterans themselves.

According to Delano, if this effort succeeds, VHA staff will be stripped of the union protections needed to be effective patient advocates and more active foes of privatization. “Without that collective voice, doctors, nurses, and other healthcare professional will have far less ability to speak out on behalf of veterans,” he warns.

…

The Challenges of Organizing Precarious “Gig” Workers

By Wade Rathke

When we think about organizing precarious “gig” workers, the task may be biblical. The workers may be ready, or not, but the spirit and the flesh are weak. We all bemoan the rise of gig workers. Low pay, few hours, no benefits are some of them, worsened by the uncertainty of a position where you can only work to deliver something being demanded by consumers at a premium you are powerless to control. App companies misclassify workers as independent contractors rather than employees in order to pass on all of the maintenance and capital costs, aside from web work and marketing, to the workers, avoiding the personnel benefit and equipment costs that are routine and inescapable for regular employers. Worker conditions seem to cry out for a union, but unions have to be wary at answering the call no matter how loud.

A recent “strike” by Uber drivers in Los Angeles illustrates the problem. The company had triggered the strike by increasing its percentage of the fare, thereby decreasing drivers’ pay. In response, the drivers turned off the Uber application on their phone and by doing so did not respond to any calls or inducements to drive. Stated more plainly, they went on strike.

Did it work? Who knows? How would any of us, whether organizers, curious observers, or company officials, know how to measure the number of drivers protesting in this way versus those who just decided not to drive on any given day or got ticked off and responded to Lyft instead or whatever? ACORN tried a similar approach in the early 1970s when we were fighting increases by the Arkla Gas Company in central Arkansas. Our “Turn Off Arkla Day!” action got a bit of press, as the Uber drivers did in Los Angeles. But in both cases, the company yawned since there was no way to measure whether the strike affected their cash flow at all.

Organizing gig workers can be challenging, but there’s some good work going on for bicycle deliver drivers in Europe, where companies like Uber Eats, Deliveroo, and others have become ubiquitous. Last fall one of ACORN’s affiliates organized a meeting in Brussels that brought together union activists interested in organizing European bicycle delivery drivers with fledgling groups of drivers from a dozen countries from the UK, Netherlands, Germany, and others. That meeting highlighted several active organizing projects:

– Bike Workers Advocacy Project (BWAP), a new group seeking to organize cycling workers and, eventually, lead to some kind of unionization or union-style representation. Drivers at Postmates and Caviar in New York City and some bicycle shops seemed to be stirring the pot in 2018, but nothing seems to have emerged formally to date.

– Bike delivery workers at Foodora and Dilveroo in Germany have raised issues about low wages and their independent contractor situation while advocating for a union.

– In 2016, London gig workers for delivery services Deliveroo and Uber Eats organized protests and strikes for higher wages. There was also an outcry in Philadelphia when a rider for Caviar was killed while working.

– Legal action has managed to win back employment rights, such as a recent ruling in Spain that declared that a Deliveroo rider was in fact an employee and not an independent contractor, as the company claimed. Caviar is in mandatory arbitration in California on the same issue. As importantly, riders in London struck for three days in 2018, and joined with striking McDonalds’s workers to demand higher wages, largely organized by a chapter of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW).

While these examples seem promising, unions clearly lack any real commitment to organize these workers, and the workers have limited leverage. David Chu, who directs the European Organizing Center, a joint project between European unions and the US-based Change to Win federation, told me recently that he hears a lot of talk about organizing gig workers but sees little action in that direction, but perhaps the spirit – and many workers – are willing to organize, but the flesh-and-bones unions are not?

Serious organizing efforts in the United States have been contradictory and embryonic. Uber in New York City and San Francisco reacted to organizing efforts by attempting to coopt the organizations into agreeing that the workers were not employees in exchange for consultation rights on rule changes and other issues like receiving tips. More concerted efforts to create a mini-National Labor Relations Board representation mechanism were launched at the municipal level in Seattle, but the organizing effort is currently mired in litigation over preemption by the National Labor Relations Act and the question of employee status.

Local efforts reflect the way companies keep changing their practices, as Marielle Benchehboune, coordinator of ACORN’s affiliate, ReAct, noted recently in Forbes. “What will make the difference,” she suggested, is workers organizing “on the transnational scale.” Perhaps her analysis is correct. Perhaps a rare global organizing plan could create enough pressure and leverage among these competing companies that could weld a workers’ movement together from the disparate pieces of independent worker mobilizations that are cropping up around the world.

Given the challenges, how much should we invest in organizing gig workers? Labor economists in the US caution that despite all of the hype from Silicon Valley and even some labor officials about the emerging gig economy, it involves a very small percentage of the workforce. Others, like Louis Heyman in the recent book, Temp: How American Work, American Business, and the American Dream became Temporary, argue that gig workers are just the pimple on the elephant’s ass of contingent and temporary labor that has been hollowing out the American workforce for decades, just as consultants have chipped away at management jobs as well.

I heard something similar fifteen years ago, when I asked a leader of the Indian National Trade Union Congress if they were doing anything to organize call center workers in India. He answered that they estimated that there were 30,000 such workers, but there were 450 million workers in India at the time and hardly 9% were organized. He then shrugged. That’s all he said, but we got the message. There’s much to be done in organizing the unorganized, and resources and capacity are always restrained, whether in India or Europe or North America.

Is that a reason for not finding ways to organize workers who are attempting on their own to find justice on their jobs? Or is it just another rationale for doing little or nothing? The one thing that seems clear is that if unions are going to be relevant to the modern workforce and the irregular and precarious forms of work that are being created by technology married to avarice, we must debate and address these challenges. It may be difficult, but unions and organizers need to devise practicable strategies that allow workers to organize, win, and build enough power to force companies to adapt and change.

I wish we had the answer now, because the workers seem ready, but one way or another, we need to figure this out quickly!

…

This article orginally appeared on the blog Working-Class Perspectives

The Immigration Issue & The Politics of Deceit

By Harry Brill

It is certainly a challenging problem for progressives on how to address the gap between themselves and conservatives. The difficulty is not just due to the immense ideological differences. Progressives have to confront the considerable deception employed by many conservatives.

Apparently conservatives have persuaded a substantial number of Americans that illegal immigration is bad for Americans. According to the polls not only Republicans accept this rhetoric, so do a majority of independent and Democratic Party voters. In fact about two-thirds of the public believes that the U.S. military should defend the southern border from the “invasion” of immigrants. Not only Caucasians but also a majority of Blacks and non-white Hispanics share the same perspective. Generally speaking a CBS poll found that 72 percent of those who watched President Trump’s State of the Union address agrees with his ideas on immigration.

President Trump’s interest in building a wall on the southern border of the U.S. is wrong. It is a deceptive effort to convince working people that he wants to protect their interests.

Yet according to the Southern Poverty Law Center, at least 60 percent of the country’s farm workers are undocumented. The Trump administration has not made any serious effort to crack down on the Agricultural industry’s employment of illegal immigrants. In California there are about 2 1/2 million undocumented immigrants, man work on the fields as well as construction and manufacturing.

The Trump administration has engaged in raids of enterprises that employ undocumented workers – always touted in his tweets and Fox News – to convey the impression that the government is seriously attempting to curtail the employment of undocumented workers. However the real intent is not to discourage use of undocumented workers, these raids are intended to discourage efforts to engage in labor action that workers might use to improve their conditions and protect their rights.

In reality while Trump urged that a wall be built to discourage illegal immigration he has employed undocumented workers at his golf course and his private clubs.

What elected officials in both the Democratic and Republican parties have failed to acknowledge is the important role government has played in encouraging illegal immigration. For example, soon after the North American Trade Agreement (NAFTA) was adopted, the federal government subsidized American corn growers so they could sell corn in Mexico at an artificially low price. As a result, Mexican corn growers could not compete and went out of business. So not as a matter of choice but to survive, they attempted to cross the border to find jobs. In the case people from Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador to migrate to the U.S., it is in large part a result of their dictatorial regimes that were installed or supported by the United States. Yet the Trump administration claims that their decision to flee from many of these countries has been entirely voluntary.

Progressives must continue to find opportunities to reach out to the public. The country deserves nothing less.

…

The Classic Organizer – Bob Moses

By Mike Miller

Bob Moses was the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) “field secretary”(organizer) who in 1962 began the voter registration and community organizing work that broke the wall of Mississippi segregation. Moses became a legend, but he refused to become a public spokesman for “The Movement”, insisting on the classic organizer role of developing and projecting others. An initial dozen African-American young people, many themselves local Mississippians, began the patient work of encouraging local people to go to the county courthouse to register to vote. By 1964, almost 1,000, mostly northern white, students, and legal, health and other workers, had joined them in the Mississippi Summer Project that was directed by Moses. One result was the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) challenge at the 1964 Democratic Party Convention to the seating of the State’s racist “regulars”. The rejection of that challenge, led by President Johnson and the leadership of the Party, was a key event in the radicalization of the student movement.

Moses refused to be drafted to fight in Vietnam. He left the country, quietly returning after a sojourn working in Africa. More recently, he has developed a pedagogy for teaching algebra to lowest quartile students. That work led to a McArthur “genius” award and The Algebra Project.

Mike Miller

.

Bob Moses on “Earned Insurgency”. (From YouTube, 2007)

“My point about insurgency is that we need to have insurgencies to have democracy. In the ‘60s, the sit-ins were insurgencies; the sit-inners were insurgents; they earned their insurgency by people beating up on them, by dressing up in suits and ties so that they could present themselves to the country so that the country could see them.

“Like it or not, if we’re going to have an insurgency that’s going to be effective we have to figure out how we earn our insurgency. We earned the insurgency of the right to vote in Mississippi by adopting nonviolence as a way to go on the offensive. That’s actually what I think happened.”

“You have to earn the right [to speak]. You have to figure out how to mount such a movement… You have to pull together the numbers of people, and the way in which you pull it [together], so that the people in power can’t ignore you; they have to go along with you.

“In Mississippi, we earned our insurgency with local people: we’d get knocked down, and we’d get back up; we didn’t run; we didn’t abandon the local people. We earned our insurgency with the country: the children of the country came to Mississippi for the Summer Project of 1964. And we earned our insurgency with the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division by carefully developing the case for their intervention. That intervention was based on a provision of the 1957 Civil Rights Act that said the Justice Department could act if local authorities were denying people the right to vote. That provision was the “crawl space” that gave us a way into the Justice Department. Without their intervention, we would have been rotting in jail.”

“I think, basically, we ran what I think of now as an earned insurgency. And we had to earn it at three different levels. One was the actual farmers and sharecroppers that we were working with. We had to earn the right to ask them to join us in this work, ’cause they were threatened, they were murdered.

“The way we earned their respect was every time—we, as organizers, had to get knocked down enough times and stand back up.

‘We were asking people to risk their lives, so we had to show them that we were actually also willing to do that ourselves. So we did that just by getting knocked down and standing back up. So every time we got knocked down, we stood back up. So you do that enough, then people think you’re real, it’s not just talk.

“[We also had to earn the respect of] the Justice Department, they didn’t have to, they weren’t required to turn the jailhouse key. …They were permitted to do it, but they weren’t required…And so we had to be disciplined ourselves to work on the voter registration, so that every time we got arrested, there was the presumption that that’s what we were arrested for. They were not going to interfere around something other than voter registration, this little legal crawlspace of the ’57 Civil Rights Act.

“And then we had to earn the right to call on the whole country to come take a look at itself in Mississippi, ’cause, yes, we were asking white students to come down into this danger, but we had earned the right by risking that danger ourselves and thinking this is an American issue, this is a constitutional issue, this is not just black people’s problems.”

On responsibility

“You’ve got to take responsibility for your government. In the end, you are the government. If you are not involved in this government, it will take you places where you do not want to go.

“The government can take us where we don’t want to go only because we don’t see ourselves as the government.

“We have to develop a culture in which we can have conversations about what we want to do about our condition.”

.

You should also read Mike Miller’s review of Keri Leigh Merritt’s Masterless Men.