ALL WE HAVE IS EACH OTHER – Of Crime and Sports

By Gary Phillips

Hunkered down at home is mostly what me and other fiction writers do most of the time. In my case it’s crime and mystery stories I generally write, making up bad shit all the time. Now unless it’s for research purposes and I need to talk to someone who knows what I need to know, it’s just me and my imagination or lack thereof. That does mean though when I’ve made my word count for the day or simply can’t get the words out of my brain onto the virtual page, I need to decompress. This often translates into watching a sports event on television or the rarity of even going out to see one live. Yet rightly so, both the NBA and pro baseball have had to forgo their seasons during this pandemic. Even as the president held a group call with the sports commissioners envisioning stadiums back to normal in August and September. Meanwhile back in reality, stars of basketball and other pro sports have stepped up in this crisis.

The Golden State Warriors Steph Curry and his wife Ayesha have donated 1M toward providing meals for the Alameda County Community Food Bank. Even that Trump lovin’ Super Bowl winning Tom Brady (who had a mansion out here in Beverly Hills torn down to build one more to his liking) ponied up ducats for a free meals program. So yeah, big time sports stars will weather this shutdown just fine. But what of those folks earning minimum wage selling you hot dogs and beer and the ones who have to clean up those fancy arenas when the fans go home?

Pro basketball stars such as Zion Williamson, Kevin Love, Blake Griffin, the aforementioned Steph Curry and Giannis Antetokounmpo have each pledged $100,000 and upwards to help arena workers who are now out of work due to no fault of their own. But as Dave Zirin, The Nation’s sports writer pointed out, the damn millionaire and billionaire owners of these teams, mostly a bunch of white men, need to step up and do what’s right by these hard-hit arena workers as well. What he wrote is best summed up with his line, “The ownership plutocracy must provide paid leave for these workers, because promises made have to be matched by promises kept.” Some of these owners have come across but it’s clear that across the board all of them can do much more for those not getting paid to throw that rock through a hoop.

Thinking about the sports venues got me wondering about robbing such – in a literary sense of course. For is not the thief what Jean Genet wrote in his book The Thieves Journal, “Repudiating the virtues of your world, criminals hopelessly agree to organize a forbidden universe.” Mindful that Woody Guthrie noted you can rob more people with a pen than a gun, the thief is the representation of naked capitalism who at least if he or she is “honest” splits the spoils with their crew.

In particular I recall heist films of sports venues set in Los Angeles. In the 1950s film The Armored Car Robbery, thieves use tear gas to boost the gate from Wrigley Field. Not the famous one in Chicago, but the one that used to be in South Central where the Triple A Angels once played. In the ‘60s film The Split, based on the novel by Donald Westlake, ex-football star turned actor Jim Brown is a professional thief who masterminds robbing the Coliseum, also in South Central, during a football game. As far as I know, there’s yet to be a heist film about robbing a rap concert though in the novel Deadly Edge, also by Westlake, the thieves cut through the roof of an old arena during a rock concert to steal the receipts.

Maybe it’s not an arena I’ll have my crew rob, given these days too much plastic is used. But what about one of those ultra-swank bunkers the one percenters are buying for three or four million a pop in preparation for doomsday be it a pandemic or the have nots rising up. These are not your grandpappy’s Eisenhower era fallout shelters stocked with canned goods and bottled water in case the Ruskies dropped the Big One. No these bad rascals come with NBC (nuclear, biological and chemical) air-filtration systems, big screen smart TVs (like Netflix will still be operating in the apocalypse?), the bunkers themselves encased in steel and equipped with pepper spray portals. For 8.35M the Aristocrat comes equipped with a sauna, gym, swimming pool and billiards room. Yeah, these bastards plan to shoot eightball while we perish. Certainly these bunkers must come with vaults for the fat cats to put their cash and jewels in what with banks failing as civilization collapses. After all their brokers will be hunting each other down and eating the loser, right?

Stay safe and stay sanitized, y’all.

…

First ran 5 April 2020 in PM Press

It’s totally illegal

By Garrett Brown

Firing workers for raising health & safety concerns is illegal, and yet employers get away with it all the time

Since the COVID-19 pandemic hit the United States this year, health care and other essential workers still on the job have been reprimanded, disciplined, and fired by their employers for expressing concerns about their health and safety on the job. It is totally illegal to do so – yet employers have been getting away with doing exactly that for years before coronavirus.

All workers – union or non-union, documented or undocumented – have the legal right to raise health and safety issues on the job without fear of reprisal or discrimination by their employers. Moreover, all workers have the “right to refuse unsafe work” if they follow the procedures that are set out in national and state law.

Nationally, these rights are protected by the Federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and its “Whistleblower Protection Program.” In California, these rights are set forth in the state’s Labor Code (Here, Here and Here) and protected by the Division of Labor Standards and Enforcement (DLSE) and its “Retaliation Complaint Investigation” unit.

All these laws have been around for decades now. Workers in various industries – facing workplace hazards as deadly as COVID-19 – have also tried to exercise their rights in the past. But the fact of the matter is that these rights have not been effectively enforced by government regulatory agencies, and very few employers have actually had to compensate and reinstate workers that have disciplined and/or fired in violation of the law.

National Non-Enforcement

Federal OSHA not only has the responsibility for investigating worker complaints and enforcing the worker protection section 11(c) of the Occupational Safety and Health Act, but also the anti-retaliation sections of more than 20 other federal laws. Fed OSHA has the responsibility for not only worker safety, but also whistleblower protection in transportation (such as railroads), environmental protection (such as oil spills), financial and health insurance fraud, and also consumer products, motor vehicle and food safety.

Staffing at Fed OSHA, especially the Whistleblower Protection Program, has been on the decline during the Trump Administration. But the program under Democrats also never had the staff and political will required to conduct enough investigations and issue enough decisions to be a deterrent to employers violating these laws.

Under the Trump Administration, especially now that hard-line corporate attorney Eugene Scalia is the Secretary of Labor, whistleblowers retaliated against in violation of two-dozen federal laws are basically on their own.

California Non-Enforcement

As bad as the federal situation is, whistleblower protection in California would be comical if it did not result in job-ending and poverty-producing reprisals, discrimination and firings by Golden State employers.

The DLSE Retaliation Complaint Investigation (RCI) unit has only five (5) investigators for a workforce of 19 million workers in more than one million worksites throughout the state. Retaliation investigations require considerable time and skill to complete because the employers involved tend to lie from the get-go of the investigation, and the investigator must find enough incriminating evidence (such as internal documents and corroborating testimony) that will “prove” retaliation and get beyond the usual “he said, she said” stalemate.

The abysmal performance of the California RCI has been documented annually in the “Federal Annual Monitoring and Evaluation” (FAME) reports conducted by Fed OSHA. The Feds conduct a “comprehensive” investigation in one year, a “follow-up” investigation the next year, and then start the sequence again.

The FAME reports cover federal fiscal years – starting October 1st of one year and ending on September 30th of the following calendar year – and are usually issued six months after the September date. The two most recent FAME reports on California’s whistleblower protection were issued in early 2018 (comprehensive) and in early 2019 (follow-up).

The last FAME report indicated the following head-spinning performance of California’s RCI:

- The percentage of retaliation investigations completed within 90 days (the federal benchmark) = 4%

- The average number of calendar days needed to complete a retaliation investigation in California = 588 days

- The percent of retaliation investigations in California that are closed as “non-meritorious” = 81%

This last FAME report (issued in early 2019) noted deficiencies that were also the subject of repeated earlier reports:

- The RCI “does not have an updated whistleblower investigation manual” that is at least as effective as the federal investigation unit;

- In 68% of reviewed RCI case files, “there was no evidence that DLSE referred the retaliation claim to Cal/OSHA;”

- In 96% of reviewed RCI case files, “there was no evidence that DLSE conducted a screening interview and created a Memorandum of Interview based on information learned during the screening interview;”

- In 53% of reviewed RCI case files “there was no proof of receipt that the Complainant or Respondent received a closing letter;” and

- In 33% of reviewed RCI case files, “there is no evidence that a DLSE supervisor reviewed and approved the decision to administratively close complaints.”

For workers in California, perhaps even more than in states covered by Federal OSHA, their right to protection against illegal retaliation and reprisals from their employers basically does not exist.

Worker protection in the real world

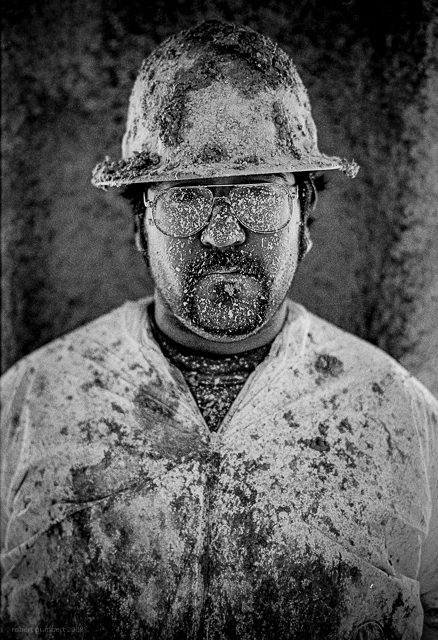

Photo: © Robert Gumpert 2000

Since workers are on their own when it comes to protecting their freedom of speech and right to refuse unsafe work on the job, other strategies have to be explored and adopted to fight the illegal acts against them. This has always been the case, but, in the COVID era, it becomes even more important.

Work with your union: Workers who have a union in their workplace (less than 7% in the private sector now) have the opportunity to file grievances and have the union represent them in grievance and arbitration hearings. Some unions will file legal action on behalf of their members to gain reinstatement and back wages if the grievance and arbitration routes fail.

Notify the news media: As indicated in the articles in the New York Times and Washington Post above, the news media is interested in covering what is happening to health care and other essential workers in the midst of the pandemic. Most articles have been sympathetic to workers still on the job saving lives and keeping people fed and supplied with the basics. “Naming and shaming” employers engaged in violating workers’ rights via the media has proven successful in the past in getting some workers back on the job and their rights respected.

Notify your elected officials: While we all know some federal, state and local officials that have forgotten who they are paid to work for, there are others who have championed the cause of workers who have suffered illegal reprisals and terminations. Public pressure on employers via elected officials has proven effective in cases in the past, and will likely be so now in the midst of so much pain and suffering in society.

So workers whose rights are violated should definitely file retaliation complaints with the appropriate government agency. They should also understand that the chances for success via that route alone are very, very slim, and would take months and months to be realized. But there are other routes – always best working collectively with coworkers in legally-protected “concerted activity” – that workers can take to get their jobs back, to prevent employer discrimination, and protect the rights of all.

…

U.S. Labor in the Time of the Corona Virus

By Peter Olney and Rand Wilson

Union responses to the pandemic reflect the relatively weak state of the U.S. labor movement, but also reveal the potential for new militancy and growth!

President Trump proclaimed on March 24 that the U.S. would be open for business by Easter Sunday with churches filled with devout worshippers. Not only was this a massive slight to the millions of non-Christians, it was fundamentally a toxic recipe for escalating the COVID-19 public health menace. Only a few days later, the reality of the escalating public health disaster got the better of his foolish narcissism: Trump now says that the country must remain on lock down through April 30. It may go much longer.

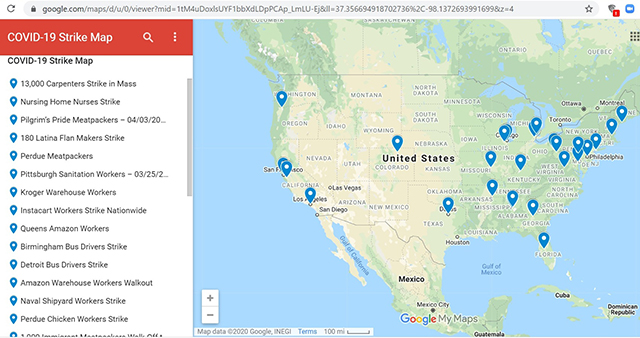

Signaling both growing anxiety and the need for solidarity brought on by the coronavirus pandemic, workers across the country are protesting what they see as inadequate safety measures and insufficient pay for the risks they are confronting. The response by American workers reflects the relatively weak state of the U.S. labor movement, but also reveals the potential for a new militancy and growth.[1]

U.S. unions only unite 7% of private sector workers and some 35% of public sector workers. In the private sector, the structure is characterized by “enterprise” bargaining rather than national sector or “category” bargaining that is seen in Italia or many other European countries. This has meant that instead of U.S. unions acting together under the aegis of the AFL-CIO, the response has been fragmented. Nevertheless, there have been many impressive initiatives both legislatively and by industry and in geographical areas.

When the U.S. Congress passed a nearly $2 trillion financial bailout bill for corporations, labor was able to attach a “union neutrality” clause for companies employing more than 500 workers who seek to unionize.[2] Winning union neutrality has long been one of labor’s major legislative goals. Given the already weak enforcement of U.S. labor laws, this provision will be even harder to enforce, as the National Labor Relations Board has been all but shut down during the Corona crisis.[3]

Where the U.S. labor movement still has membership “density” and particularly in sectors now considered essential because of the virus, unions have been able to achieve some impressive results. Transportation is one of those sectors. The airline unions, led by Sara Nelson, the dynamic President of the Flight Attendants, won a provision in the massive industry bailout to pay all direct airline employees (pilots, mechanics, flight attendants) through September 30. Even more impressive is that airport contract workers like cleaners, food service workers, and other ground personnel will also be paid through the same date.[4]

Bus drivers and train operators in many urban areas have demanded protections from infection while operating their equipment. On March 17, Detroit bus drivers declared that they were not going to work without safety precautions. Bus service was cancelled and within 24 hours, workers won all their demands, including an agreement that fares will not be collected during the coronavirus crisis. Passengers will now enter and exit from the rear entrance — avoiding contact with the operator.[5] Sadly on April 1, Jason Hargrove, a rank and file Detroit driver, died of the virus after being coughed on by a woman entering his bus. His video of that event went viral on March 21 and helped to spread awareness of the need for protection for essential workers.

As the public has come to understand that grocery store workers are essential, it’s put their union, the United Food and Commercial Workers in a good bargaining position. UFCW has won significant raises and protections for its stressed-out members selling groceries. Workers also won additional paid time off (PTO) and generous provisions for sick leave. Los Angeles took the lead by mandating sick leave and other benefits far beyond the usual contractual requirements for grocery workers.[6]

The response by construction unions has been uneven. Boston Mayor Marty Walsh, a former construction union leader, shut down all non-essential construction on March 16 while his counterpart in New York City permitted construction of non-essential luxury condominiums to continue until March 27. On April 6, the Massachusetts Carpenters Union went a step further and walked all of their 10,000 members out in protest of continuing hazardous conditions. The International Union of Painters and Allied Trades District Council 35 followed suit, with the union issuing a stay-at-home order for its thousands of members the next day.[7]

Automobile assembly has been shut down throughout the U.S., however auto parts production continues in many areas supplying assembly plants that continue to operate in Canada and Mexico, a reflection of the United Auto Workers weakness.[8]

One of the most inspiring actions during the crisis was the walkout by thousands of General Electric workers who make jet engines in Lynn, Massachusetts on March 30. Along with a vigorous protest concerning their safety at work, they demanded that their employer convert to making ventilators![9]

The Communications Workers of America (CWA) and the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW) representing 34,000 employees at the telecommunications giant Verizon won paid leave for workers unable to work during the crisis.[10]

These examples are a reflection of the low level (currently under 7%) of union representation in the private sector. In places where unions are still strong, like transportation, communications and grocery, labor is winning victories, but the 93% of American workers without representation have had to make do with valiant initiatives despite having no pre-existing or formally recognized organization.[11]

So often dismissed as low-skilled and now on the frontlines of a pandemic, many not-yet-union workers in the U.S. are discovering the power of collective industrial action. Despite their lack of formal organization, many workers in the so-called stars of the new economy are demonstrating the capacity to rise up. Amazonians United, a warehouse-based organization with strength at distribution centers in Chicago, Sacramento and Queens, NY has waged a long fight for paid time off (PTO) for warehouse workers. As a result of their actions and others, Amazon finally agreed to grant PTO to all employees in mid-March.[12],[13]

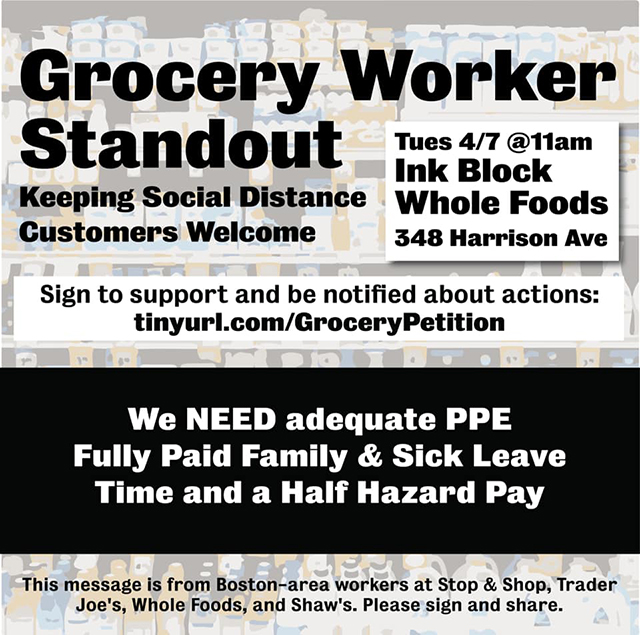

Thousands of drivers for the online grocery delivery service, Instacart also struck on March 30. On March 31, Whole Foods workers engaged in a global sickout to protest their working conditions and publicize their fear of working and contracting COVID 19. In nearly every example of the new militancy, workers have used online organizing tools and social media to reach their co-workers and gain public support. For example, workers at Fred Meyer launched an online petition for hazard pay.[14],[15]

Workers are also showing compassionate solidarity in the midst of the pandemic. For example, the restaurant support group One Fair Wage is providing cash assistance to restaurant workers, car service drivers, delivery workers, personal service workers and others who have lost their incomes.[16]

Along with the presidential campaign of Senator Bernie Sanders, the pandemic is happening at a moment that working-class politics are on the rise. Sanders, and the movement behind him, have introduced a set of bold initiatives into the mainstream of political discourse. Now the public health crisis has added additional credibility to his proposed policies.

In a first for an American political campaign, Democratic presidential candidate Bernie Sanders (who dropped out of the race on April 8) has reached out to his enormous campaign base to raise millions of dollars to support many of these workers. He has used emails and texts requesting contributions to a variety of worker relief organizations and urging supporters to make phone calls and send letters to shame corporate executives.[17]

Labor for Bernie, the trade union support coalition for the Sanders candidacy, is working with its member unions and allies to promote a national program of demands on the federal government regarding health care, sick leave and extended unemployment benefits. At the end of April, as many as 35 million Americans will lose their employer-based health insurance. The scale of that crisis is an opening for legislation to provide emergency health insurance to all Americans who do not have it. The price tag of over one trillion dollars no longer seems extraordinary after the two trillion-dollar bailout for American corporations![18]

Crisis can birth opportunity, and there is the potential for game changing political demands on the state to strengthen the horribly weak U.S. social safety net and build new membership and power for labor. Many on the left in the U.S., particularly the young members of the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) are aggressively organizing. Activists are finding strength, encouragement and support in countless online video hookups that enable organizing nationwide while sheltering in their homes.

American society is getting a large and dramatic lesson in who is “essential” and “non-essential.” The lowest paid workers, often immigrants, women, and people of color make up the ranks of the service and agricultural sectors. Now the public is discovering these workers are far more crucial to the functioning of society than the owners and their professional managerial class. American workers are getting a powerful lesson on the power of collective bargaining and unionization. They are finding that without a union they are employees at will with little right to address their challenges in the workplace.

There is obviously great potential for radical change and restructuring to emerge from this crisis. The need for dramatic federal intervention on behalf of working people has probably not been this keenly felt since the 1930s. But without escalated organizing and action, the end result of the crisis will be another massive corporate bailout, similar to what happened in 2009 after the Wall Street meltdown. We believe the potential for renaissance and revelation has never been greater for American labor: but only if we seize that opportunity and organize!

…

This piece ran April 13 in the Italian publication Sinistra Sindicale

[1] “Strikes at Instacart and Amazon Over Coronavirus Health Concerns,”

[2] “Virus Loans to Come With Union Neutrality Pledge for Companies,” by Jaclyn Diaz, Daily Labor Report, March 26, 2020,

[3] “In Midst of a Pandemic, Trump’s NLRB Makes it Nearly Impossible for Workers to Organize a Union,” Celine McNicholas, ECONOMIC POLICY INSTITUTE, April 1, 2020

[4] “How Labor Unions Won Historic Pay Protection For Aviation Workers,” Ted Reed, Forbes, March 26, 2020

[5] “Detroit Bus Drivers Win Protections Against Virus Through Strike,” Jane Slaughter, Labor Notes, March 18, 2020.

[6] “The Danger We’re Facing: A Grocery Worker Speaks Out,” Chris Brooks, Labor Notes, March 23, 2020.

[7] “Thousands of Mass. Union Members Walk Off Jobs Due to COVID-19 Fears,” Scott Van Voorhis, Engineering News-Record, April 6, 2020,

[8] “Auto Companies Announce Closure Following Outbreak of Wildcat Strikes” Chris Brooks, Labor Notes, March 18, 2020, https://labornotes.org/blogs/2020/03/auto-companies-announce-closure-following-outbreak-wildcat-strikes

[9] “General Electric Workers Launch Protest, Demand to Make Ventilators,” By Edward Ongweso Jr, VICE, March 30 2020

[10] “Verizon Unions Win Model Paid Leave Policy for Coronavirus—Will Other Unions Demand the Same?”

March 18, 2020, Labor Notes, and “Sample COVID-19 Health and Safety Measures to Demand from Management”

By Communications Workers of America Organizers, Labor Notes, March 31

[11] “‘The Strike Wave Is in Full Swing’: Amazon, Whole Foods Workers Walk Off Job to Protest Unjust and Unsafe Labor Practices,” by Julia Conley, Common Dreams, March 30, 2020

[12] “The US’s week of strikes,” BY EMILY TAMKIN, New Statesman, April 4, 2020

[13] “Amazonians United Wins PTO for all Amazon Workers,” by DCH1 Amazonians United, March 22, 2020

[14] “Work strikes at Amazon, Instacart and Whole Foods show essential workers’ safety concerns,” Mike Snider, USA TODAY, March 31, 2020, https://finance.yahoo.com/news/strikes-amazon-instacart-whole-foods-172609317.html

[15] “Fred Meyer associates deserve hazard pay!!” Grocery Store Workers Confront Coronavirus, Co-Worker.com

[16] “ONE FAIR WAGE — Emergency Coronavirus Tipped and Service Worker Support Fund”

[17] Bernie campaign volunteers texted the author on April 2, 2020 “Hi Rand, it’s Sydney with Bernie 2020! Thank you so much for standing with Amazon workers this week by signing their petition and emailing Jeff Bezos. Adding your voice is how we win. Will you amplify our message even further by calling Amazon and demanding that they take every measure possible to protect their workers during this crisis? We can help you with what to say!”

[18] “COVID-19 job losses could drive down employer plan enrollment by as much as 35M, report shows,” by Paige Minemyer, FierceHealthcare, April 3, 2020.

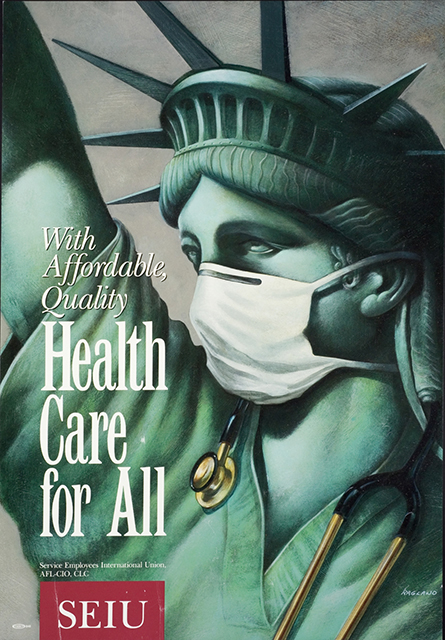

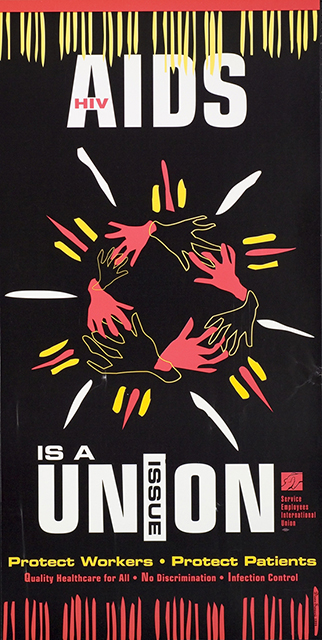

Health Care posters

By Lincoln Cushing

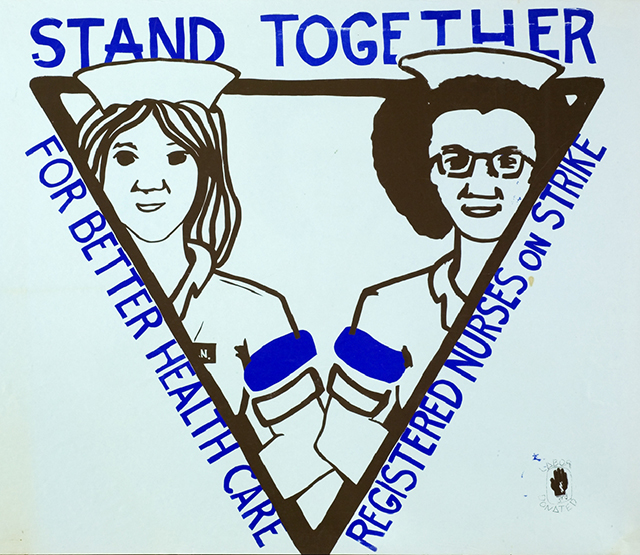

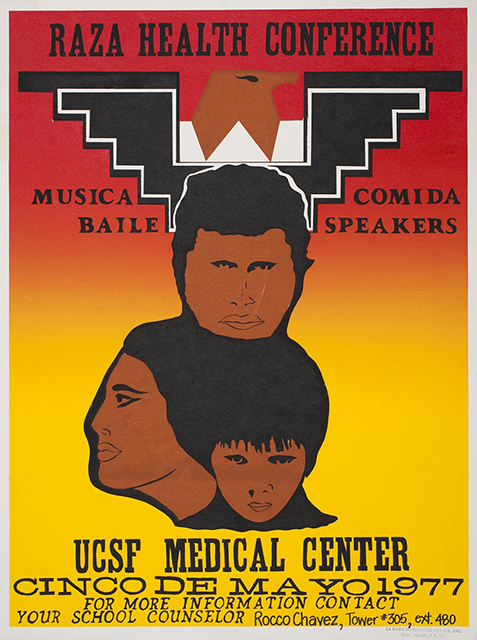

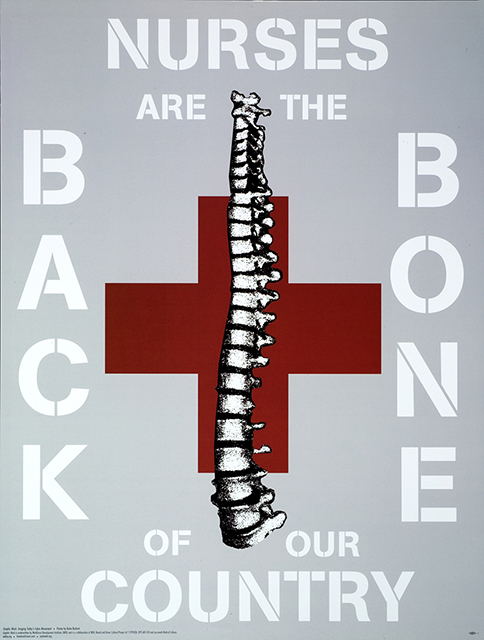

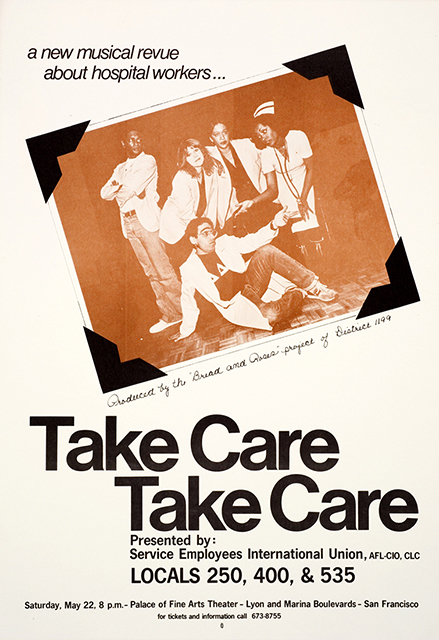

The COVID-19 pandemic hit us in the middle of a presidential election in which health care is a central issue, so it’s an opportunity to review some of the images that the labor movement has produced. In 2002 my colleague Tim Drescher and I surveyed dozens of archives and collections for the first comprehensive book on posters of the American labor movement, Agitate! Educate! Organize! American Labor Posters. Some of these are from the important Los Angeles collection of the Center for the Study of Political Graphics, the rest from my own physical and digital archives at Docs Populi (Documents for the Public).

For the current crisis, I’ve pulled some of those, and more, for this brief display of health care images.

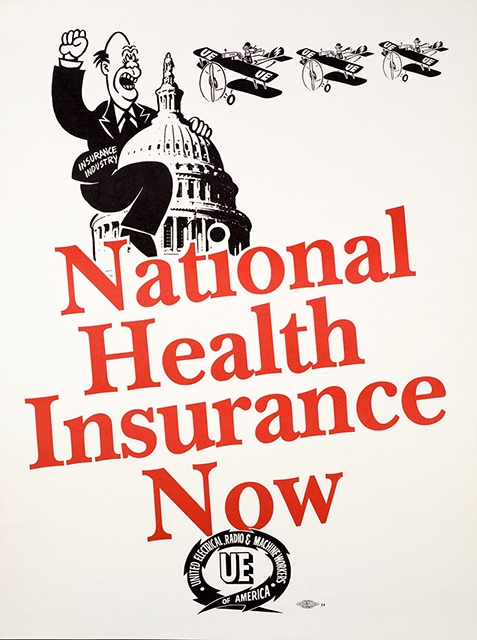

Some of these [Photos 1, 3, 8] are the polished products of large

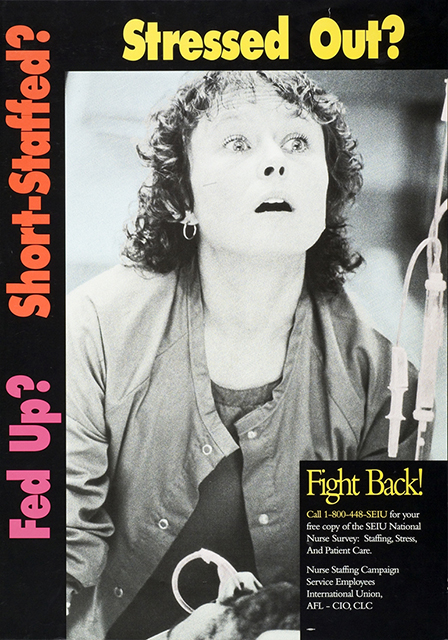

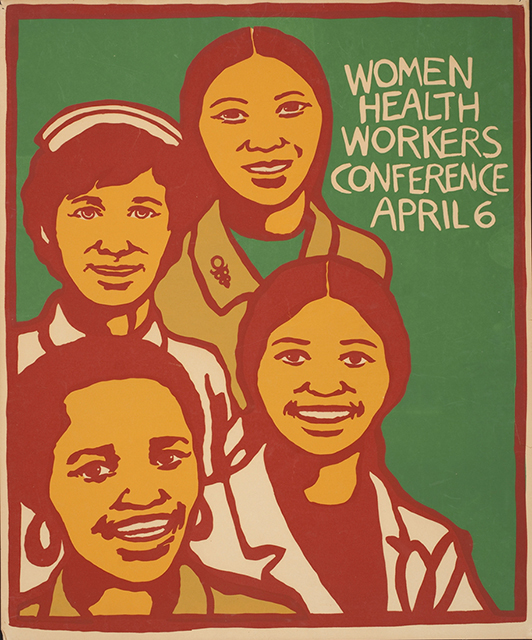

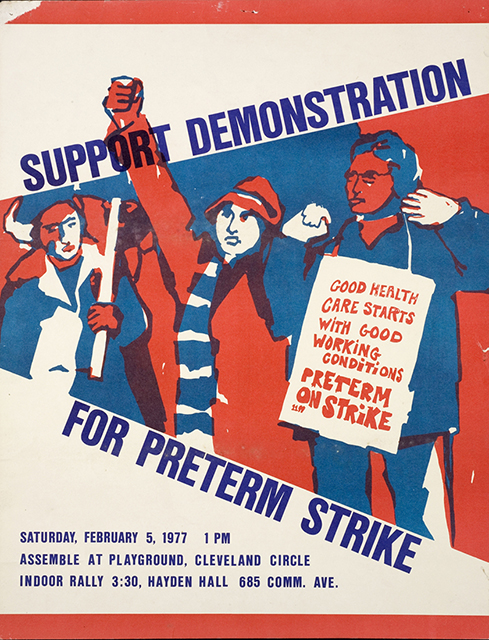

international unions, others [Photos 2, 4, 5, 9] are spirited local media

supporting community-based programs and labor actions. Artists and cultural workers have lent their skills to this messaging – [Photo 10] is by a

member of the decentralized artist’s cooperative Justseeds, and [Photo 6] is

admittedly a stretch for health care, but a great safety mask graphic. It’s an homage to the classic 1975 labor book Detroit: I do mind dying: a study in urban revolution, updating it to be a more inclusive “WE.” The artist explains: “It’s a portrait of myself or anyone as an industrial worker. The mask is about worker protection today, same as it was 40 years ago.”

And a huge shout-out goes to New York’s SEIU District 1199, the National Union of Hospital and Health Care Employees. During the late 1970s and early 1980s they committed resources to the Bread and Roses Project, perhaps the most comprehensive labor arts program ever in the US, supporting art exhibitions, Labor Day street festivals, poster art, and theater [Photo 11].

Progressive labor unions aren’t shy about taking on broad health care policy issues, such as national health insurance (sound familiar?). Fred Wright (1907-1984) the prolific labor cartoonist pits the embattled insurance industry Kong against waves of UE pilots [Photo 3]. And when a previous virus was ravaging the world, the role of frontline healthcare workers was honored in print [Photo 7].

Posters may not make us healthy, but they certainly can help the workers and unions that do. Support our frontline staff. Support our health care institutions.

…

Letter from a London Emergency Department

By Caitlin Jones

.

This is an email I received a few days ago from London, UK. She’s working difficult hours at the moment and very front line.

.

Dear Robert,

I am a staff nurse working in the Emergency department of a large London hospital. I thought I could share some thoughts about how things have begun to change on the frontline in the past few weeks.

In the beginning we were aware of more patients arriving at the emergency department (ED) although these patients were tending to self-refer and were well. The hospital set up a hello system whereby it became much more organised. Patients presented to nurses outside the hospital and described their symptoms in a streaming service. Without banging on the doors and windows which was a little disconcerting!

As the weeks have gone on our whole department has had to evolve to try and cope with the growing number of attending patients who are presenting with covid19 symptoms and all the London Ambulances (LAS) arriving as Blue lights with symptomatic patients from their homes.

Initially our resuscitation area was designated ‘dirty’ ( = cover 19) along with our waiting area which was split in half, cold and dirty areas. Soon I think they realised it was a bit like segregating smokers on a plane and entire areas had to be designated as ‘Hot’. We had to progress to all of the waiting area being “Hot’ and now all of our ED using our paediatric areas to cope with the growing demand.

In these times our nursing duty of care really does remain the same. We have always cared for poorly patients and that is exactly who we are still seeing. If I think too hard about the sudden increase in this one symptomatic type of patient then it can become overwhelming but essentially I am still doing the same job that I have always loved.

The donning and doffing of our PPE wear was a bit challenging in the beginning but we’ve all become very quick at donning and although some times there is not all the right equipment this has improved and we have always had the correct facemasks for the areas where our patients are being ventilated. I know that our team of management really are doing their best to ensure we have all the right equipment.

When working the other night we were expecting another resuscitation blue light call. All staff were prepared and wearing our PPE, resembling a little like the scene in ET with the tents and forensic suits. We have taken to writing our names and roles on each other’s gowns (some nurses are now Lords and Ladies) importantly so we can tell who is who and give the patients a chance to know our positions. I realised as I greeted a new patient that they could not see any of us smiling. It’s terribly difficult to hear us talking through the face masks and that we couldn’t make them feel instantly better by smiling was a real low point. Of course we all do our best and talk and care but this lack of human contact is so scary.

I understand how crucial the protection equipment is and the lockdown but it has made the importance of human contact even higher in my world. I really look forward to when I can be close enough to someone in the street to rub shoulders and to be able to smile at everyone without worrying.

Many smiles!

Caitlin Jones staff nurse

…

What Should Bernie Do?

By Mike Miller

Tom Gallagher says “…We Need Him Now More Than Ever.” Need him to do what? That is the question. I don’t think Tom’s answer is the best one.

Responding to Tom

To begin with, conflating “mainstream” with “establishment” puts together in one category what are clearly two. “The establishment” is the power structure and its allies in the Democratic Party. “The mainstream” is those voters who stayed home when Bernie thought he could turn them out, and those voters who cast their ballot for Biden despite their support for most if not all of the Sanders’ program because they believe Biden is the better choice to beat Trump—which must remain our principal concern. That way of understanding the problem is different from Tom’s “the party’s ‘mainstream’ or ‘establishment,’ depending on where you stand. It doesn’t matter where you stand to see the facts of who turned out, who voted for whom, and who has how much money to continue campaigning. Bloomberg’s limitless money didn’t help him much with voters.

Nor do the litany of ills facing the country, the nature of the current power structure, or the consequences of neo-liberal policies tell us what Bernie should do. Gallagher provides us a recital of what readers of this forum already know and agree upon.

His analysis of why Bloomberg and other challengers dropped out of the race doesn’t mention that they didn’t do very well in places and with constituencies they needed for them to continue running. Thus it was not only Establishment Democrats who dropped out, it was also Warren, Steyer, Yang, Gabbard, Castro, de Blasio and Williams. Candidates drop out when a combination of money and votes necessary to gain a significant number of Convention delegates isn’t there. He says, “a principal reason for…dropping out…has generally been the inability to continue to raise money,” omitting the fact that diminished funding is in large part a function of how many votes a candidate is getting.

“The rationale of the Sanders campaign,” Tom tells us, “has always been that Donald Trump should not be allowed [to] win…by painting the Democrats as the business-in-Washington-as-usual-party.” Were the Democrats simply that, Sanders should have run as an independent—a third party candidate. But things aren’t that simple. Indeed, as Tom has persuasively written elsewhere, the nature of this system is that we are stuck with “lesser of two evils” politics. That the Democrats are lesser is daily demonstrated by the fights between the Democrat-controlled House and the Republican-controlled Senate, and by the Democrats versus Trump over how to respond to the Corona virus-caused health care and economic crisis. That’s what Black voters in South Carolina understood when they overwhelmingly voted for Biden despite their support for, to take just one example, universal health care.

The Corona Moment

The health, employment, housing, income and other crises for hundreds of millions of Americans posed by the Corona pandemic is an opportunity for qualitative leaps forward in both program and organization. Good strategists say, “never let a crisis go by without using it.” But note this: crisis encompasses both danger and opportunity. How are the causes of universal health care, living wage, workers’ right to organize, small business support, tenant and homeowner protection against eviction and foreclosure and others, and the organization that moves them forward, strengthened and expanded in this crisis moment?

The overarching strategy Sanders should pursue is uniting progressives, and joining with centrists to beat Trump. In that framework, he could negotiate substantial victories that build upon the gains his campaign has already made: the candidate for vice-president, party platform planks and their implementation, executive orders to be issued on Day One of a Democratic President’s term, appointments to Federal Courts, ambassadorships and the President’s Cabinet and sub-Cabinet positions, appropriations for massive infrastructure programs and transition to a climate-friendly economy, and others. You can’t form a united front while you’re daily attacking your major partner in that front. And that doesn’t mean you abandon your platform, principles or campaign; it simply means you are strategically and tactically wise.

The risks of a Sanders campaign based on continued attacks on Biden (which, for example, a face-to-face debate would require) and his neoliberalism are:

- decline in Sanders primary votes as more-and-more people conclude Biden is the one to beat Trump (or even someone else who might be drafted—who knows what the recent sexual abuse allegation will mean for Biden’s campaign);

- divisions (already appearing) in Sanders’ coalition;

- decisions of importance made in his absence (as Biden is now doing in his search for a VP), and;

- increased numbers of people who dismiss Sanders as a sour grapes candidate.

Sanders can negotiate a powerful united front and nominally remain in the race, “nominally” being the key word. Staying in or bowing out becomes a narrow technical/tactical question if a different strategy is adopted—one that focuses on the Corona opportunities, avoids personalizing attacks on Biden, and pushes Establishment Democrats to adopt a program that meets growing demands from everyday Americans for help in this crisis.

That strategy can be pursued by:

- deploying the powerful organization that has been built to critical races in critical states thus demonstrating a capacity to both elect progressives and make a difference in the presidential race;

- supporting emerging workplace, housing and other on-the-ground efforts as people struggle to stay alive and economically afloat, and;

- negotiating with centrist/establishment Democratic Party decision-makers (Biden and his campaign organization and the Democratic National Committee) to create the united front required to defeat Donald Trump.

The broader goals embodied in Sanders campaign will not be won this year or next. At least a ten-year timeline is required to achieve them. Defeating Trump in 2020 is a prerequisite to wider victories. Radical patience is required now; it is the long-distance runner who will win this race.

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez

On April 7, 2020’s Democracy Now, Amy Goodman asked AOC “What is happening with [Sanders] campaign right now?” Her response is interesting both for what it says and what it omits: “…I do know that…the senator and I have both been focusing very heavily on COVID relief…We need to make sure…there are very strong concessions and accommodations made for a progressive future in our country…we need to see very serious movement toward a single-payer healthcare system, a living wage, towards justice for incarcerated people and justice for our immigrant populations…[W]hen it comes to the specific things, ultimately, that is up to the senator. (emphasis added)…we must continue pushing to make sure, particularly on climate change, what kind of agenda is being formed right now, and not only what that agenda is, but who is going to be making those decisions and really administering and executing on that agenda in a potential administration.” (Does that look a lot like what’s above?)

It’s not only what’s said that’s important. The only question that is “ultimately up to the senator” is “running”, and she says not a word about it.

After describing her criticism of some left-wing activists, a March 30 Politico article title reads, “AOC breaks with Bernie on how to lead the left.” (Grant at the outset that media like to emphasize conflict.) It concludes, “Bernie is the first leftist politician who has received a national platform in a long time in this country, and so some people say that every leftist politician has got to be like Bernie,” [Justice Democrats spokesman Waleed Shahid] said. “But AOC is a different person with a different set of life experiences. So how she leads will be different. I don’t think it’s a difference in ideology — it may be a difference in approach.”

Sanders needs to pay attention to that “difference in approach”.

…

Note:

Today, 7 April 2020 at 9:00 p.m. EST Joe Biden will have a news conference on CNN. Had Bernie been following the strategy outlined above, he could have been part of that news conference to announce the united front to defeat Donald Trump.

Bernie Sanders in the Age of Coronavirus: We Need Him Now More Than Ever

By Tom Gallagher

Bernie Sanders threw his hat in the 2016 Democratic presidential ring in order to wage a campaign highlighting the need for a universal national health insurance system and, more broadly, a government run in the interest of the common person, rather than the melange of billionaires, mega-corporations, and their campaign donors and political action committees that currently dominate. In 2020, with the entire presidential primary process halted by a pandemic that profoundly challenges the nation’s health care system—and the entire economic system—you don’t have to like Sanders’ chances of actually winning the nomination to recognize that his campaign message has never been more to the point.

Can Sanders somehow recover from the very effective unity effort on the part of his Democratic Party opposition? Can he come from behind and catch Joe Biden? Well, we do know that in 2016 candidate Sanders famously did the unprecedented—and previously assumed impossible—many times over. He introduced the idea of democratic socialism to mainstream politics, rejected corporate backing, raised previously unimaginable amounts of money from people who—for the most part—didn’t have all that much of it. And, oh yes, he did this as the longest serving independent in congressional history.

But we also know that thus far in 2020, it has been the opposition—which you might call the party’s “mainstream” or “establishment,” depending on where you stand—rather than Sanders, that has notably accomplished the unprecedented, with a three-day unity tsunami that saw three of five major contenders withdrawing in favor of the one remaining who was not named Sanders. How badly did these folks not want Sanders to be the nominee? Enough for Michael Bloomberg—who had just spent a billion dollars on his own presidential campaign in only three months—to drop that effort and sign on to the anti-Sanders program. Granted, this was not Bloomberg’s last billion, but still you would have to say that this was definitely one billionaire who really doesn’t want to see Bernie Sanders become president.

This move proved quite successful, with Biden handily winning the March 17th primaries (with Ohio postponed and Illinois participation cut by a quarter) before the whole shebang went on hold, leaving him leading Sanders in delegates 1215-909, with another 93 pledged to candidates now supporting Biden, and 83 to Elizabeth Warren. And 1751 yet to be elected.

But so far as the unprecedented goes, it has been nature that has set the pace this time around, with the unprecedented coronavirus hiatus, which has started a race of another kind—the disaster capitalism feeding frenzy. Even before the Senate as a whole got into motion, four U.S. Senators—Republicans Kelly Loeffler (GA), James Inhofe (OK), Richard Burr (NC), and Democrat Dianne Feinstein (CA), a Biden endorser—had set personal examples for the rest of us, so far as not relying solely on government assistance, by taking the personal initiative in avoiding financial harm by selling off hundreds of thousands of dollars of their stocks following an administration briefing on the impact of coronavirus. And, by the way, we will all be assured that we can and must take comparable steps of personal responsibility. For instance, even as I wrote this article, Barron’s magazine was kind enough to post me a Facebook ad on the “18 Stocks to Buy Amid the Coronavirus Carnage, According to Barron’s Roundtable Experts,” along with the kicker: “When the going gets tough, the tough go shopping.” (And no hand sanitizer necessary for this shopping, either.) Of course, disaster capitalism’s real financial killings aren’t marketed to Sanders donors. They’ll come out of the $500 billion slated to go to American corporations in the government stimulus package. Corporate lobbyists will likely do the heavy lifting there—that is unless we can somehow thwart business as usual in D.C.

“So while it may be a logical proposition for the other candidates to throw in the towel when they decide they won’t be able to grab the ring themselves, it does not follow for Sanders“

Which brings us back to the presidential race again and the not unexpected call for Sanders too to step aside for Joe Biden. Which in turn brings us to our first question for the reader: Does anyone here seriously believe we’d be hearing a loud call for party unity if it were Bernie Sanders leading in the delegate count? Or would the story of the moment instead be the mainstream/establishment machinations to thwart him at the convention?

The logic behind the withdrawal call is clear and simple—the other candidates put aside their own ambition and united behind Super Tuesday’s big winner, so why not Sanders? The answer is also clear, although you’ll seldom find it addressed in the major news media. The candidates who dropped out did so in favor of another who shared their basic presuppositions, e.g., that we shouldn’t immediately try to extend health insurance to everyone currently uninsured, but only some portion of them; that the relationship between government and the nation’s powerful corporate interests does not require major overhaul; that our foreign policy is basically on the right track; that fracking should not be banned, etc. Sanders and his supporters are running a campaign that at its heart contests those presuppositions.

So while it may be a logical proposition for the other candidates to throw in the towel when they decide they won’t be able to grab the ring themselves, it does not follow for Sanders, particularly when 43 percent of the primary electorate has yet to vote. The primaries of New Jersey, New Mexico, District of Columbia, Montana, and South Dakota were originally scheduled for June 2, and Connecticut, Delaware, Indiana, Maryland, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Rhode Island have rescheduled for that date, with others postponed to an even later time. In announcing the changes, governors have spoken of protecting their states voters’ “constitutional right to vote.” Presumably they also have some right to cast a meaningful vote. And certainly when a campaign challenges the status quo and conventional wisdom, while winning remains the main goal, it isn’t everything—as it is when the campaign aims to answer only the question of “Who?” and not also “What?”

Some will grant that, yes, the Sanders message is important and, yes, the Biden campaign should adopt some of it, but maintain that it’s no longer appropriate for Democratic candidates to argue publicly. These things should be dealt with in the party platform. Unfortunately, as a past member of the Democratic National Platform Committee, I can assure you that while contesting the content of the platform is a worthy endeavor, a candidate actively campaigning on, for instance, universal health care coverage will be immeasurably more helpful to the cause than the issue’s inclusion in the generally unread and ignored platform.

And back to that unprecedented coronavirus crisis. The rationale of the Sanders campaign has always been that Donald Trump should not be allowed win another term in the White House by painting the Democrats as the business-in-Washington-as-usual party. Which leads me to my second question for the reader: With a half trillion dollar corporate give-away in the offing, does anyone here really believe that Joe Biden is the candidate to challenge the Wall Street way of doing business—either in perception or reality?

Sanders does seem to have now sloughed off the invitation to go home and decided to carry on. Remember that a principal reason for presidential candidates dropping out of the race has generally been the inability to continue to raise money. Final question: Does anyone here not think that Sanders supporters will continue to fund the race?

If the candidate is willing, huzzah! We’re in it to the end.

…

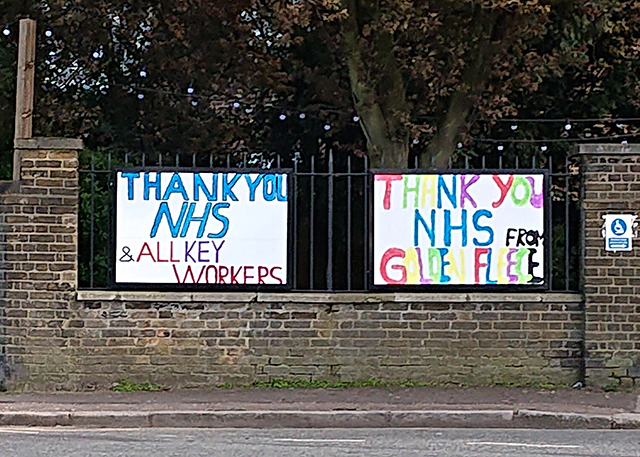

Letter from London: The NHS in the UK 2020. What does it mean to people?

By Anthony Goodman and Sue Goodman

Margaret Thatcher famously said that there was no such thing as society. The current coronavirus and the magnificent recent response of the majority of people in the UK demonstrates that this very selfish and narrow view of society is very wrong. Indeed, on 30 March 2020 the current Prime Minister, recovering from the coronavirus, commented that “One thing the coronavirus has proved is that there really is such a thing as society.” How times change!

The NHS is an important icon for all that is best in British society and no political party would dare to try to end it. Having said that, in recent years under different conservative governments, there has been a move towards hiving off elements into the private sector. Perhaps now this will be rolled back or will not continue. With the ending of European Union membership and moves to move closer to other countries, including the United States, there has been discussion whether this would open up the NHS to competition, whether it is ‘up for sale’? This, and the importing of chlorinated washed chicken, would generate much media attention.

At 8 pm on 26 March 2020 after a tweet went viral, many members of the British public went to their front doors and windows, or to their balconies, with saucepans and spoons, or just their hands, to applaud the work being carried out by NHS staff throughout the UK. The response to a government request for recently retired and newly qualified staff to join the NHS has also been remarkable.

Both of Sue’s parents were doctors, and she can recall her mother telling her of her joy at the foundation of the NHS on 5th July 1948, less than a month before she was born. Healthcare for everyone, taking away, for example, the need for parents to choose which prescribed medication they could afford to buy for their sick children.

Every day, during the COVID 19 pandemic, there has been public praise for the work of all healthcare staff. There has been severe disruption of normal operations. Regular outpatient appointments have been cancelled, although for some, phone consultations have replaced them. Routine operations have been postponed. Concentration is being put into supporting people who are seriously ill. Anthony’s brother, recently diagnosed with non-hodgkin lymphoma has started chemotherapy, a sudden temperature spike and emergency call for an ambulance resulted in instant hospital admission and treatment. The system is under serious pressure but is functioning.

It does appear that, much as it has been felt, before this emergency, the NHS was at breaking point, with successive governments continuing to encourage outsourcing and privatisation of services, the present situation has brought the nation together to provide as much support as possible for NHS staff.

In 2019 Sue had prolonged treatment for non-hodgkin lymphoma. We are unable to think of any shortcomings in the care and professional support she received, or in the technology employed in diagnosing and treating her. We have nothing but praise for the NHS, as we watched very busy staff, at all levels, politely, professionally and passionately supporting and caring for her. In any consultation, when members of her family were present, they were always included and consulted. Sue was treated with dignity and compassion, especially when she was severely ill, and her needs, both medical and personal were met at all times: x-rays, biopsies, CAT scans, PET scans, stem cell transplant etc. all were made without heed of cost. It is free at the point of delivery.

Some ten years ago Anthony experienced some mild symptoms of chest discomfort when running and immediately after a GP visit was offered an ECG, a stress ECG and very quickly an angiogram. Two hours later he was told that an artery was completely blocked and immediately he had a stent fitted. There were no questions of cost, or waiting, it was an emergency and treated as such. That is the NHS at its best and how it has operated in the UK.

We asked a GP for their experience of working in the NHS at this time and these are her comments

I am a salaried GP (so employed by a practice) in the NHS in a big UK city. I’ve been working as a GP for about 18 months. We are currently in unprecedented times with the COVID-19 outbreak and facing problems that none of the staff at my practice have known in our lifetime.

We are a large practice so are lucky that we haven’t been as affected as some by current issues with staffing levels. Currently, any staff member who is unwell with possible CV symptoms has to be off work and self-isolate at home for 1 week but any household member has to self-isolate at home with them for 2 weeks. Many of the staff at my practice have young children with the usual coughs and colds common in this age group at this time of year, so they are having to stay off work for 2 weeks even if they feel completely well. We are able to do some things from home e.g. telephone consultations and look at blood results etc. This week we have been informed that testing is now available for some NHS staff locally – I think first for A&E, intensive care workers and paramedics. We are told that these may be available for GPs next week.

I have been lucky enough to not yet get ill and I live alone so no chance of needing to self-isolate due to a household member, so have been able to attend work on all my usual days. We are doing as many consultations as possible on the phone or on video consultations. Sometimes we are triaging patients on the phone but still needing to bring them in for physical examination. We are currently advised to wear PPE if the patient has had any cough or fever but if not, we are just advised to see them in usual clothing and not take any unusual precautions (apart from the usual hand washing and just being generally careful). The concern at the moment is that many asymptomatic patients are walking around so we are maybe seeing these patients about other issues and not realising. Unfortunately, we are not currently able to wear PPE with ALL patients as there is a worry that supplies will run out.

Most patients have been extremely understanding about the current situation and so we haven’t been overwhelmed with calls as I think many patients are postponing routine queries and problems. This is a worry as well as ‘after COVID-19’ (whenever that may be) we are expecting then a huge influx of people needing consultations about routine issues. Many of these may not actually end up being routine as they may be things that need referring urgently for suspected cancer but patients were not aware of the seriousness of symptoms or did not realise that suspected cancer referrals are still being seen at the moment. Therefore we are worried that cancers diagnoses may be delayed.

Currently we are being informed that all routine outpatient appointments and operations are being delayed locally (indefinitely) so we are getting lots of patient contacting us who are in pain and not sure what to do – difficult as we can only do so much! Referrals for suspected cancer are all running as usual as far as I am aware.

We are having meetings at work every morning to update each other on any changes to guidelines and advice and support each other. We’re a close team. In a lot of ways I feel lucky to be able to still be going in to work and having some sense of normality and contact with colleagues! I’m expecting things to be all change this week as our hospitals become saturated and there is overspill into the community. We have many elderly housebound patients who we’d usually visit regularly and we’re not really seeing at the moment – I worry about them!

I’m always proud to be part of the NHS but even more so at the current time as everyone is coming together and showing the best of themselves and their devotion to helping others. In our surgery we have all had a bit of a ‘calm before the storm’ feeling for the last few weeks and I expected the storm to hit us in the next 1-2 weeks. Everyone is keen to do whatever we can to help at the moment.

This sums up the current state of play that has seen the best and worst of the human condition. Empty shelves in supermarkets due to panic buying but overwhelmingly, a sense of altruism that we need to be thinking of each other at this time. Medical staff have come out of retirement to support the NHS and the public will be prepared to pay for its continuation as a public service. There would be a puzzled response to the question why the richest nation on earth has so many people without public health cover? The NHS may be under resourced and stretched but it holds a special place in the UK amongst its population and this will not change.

…

Another article of interest:

An often overlooked region of India is a beacon to the world for taking on the Coronavirus – The Southern Indian state of Kerala has led the way in the fight against the coronavirus pandemic enacting key public health measures as well as economic and social measures to protect the population

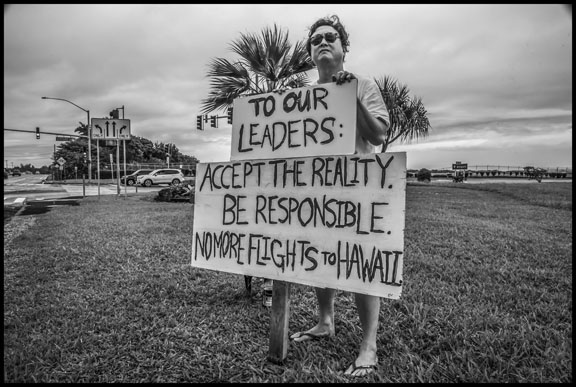

“Be Responsible. No More Flights to Hawaii.”

By David Bacon

James

“Jiro” Yuda holds a sign at the entrance to the access road to the

Hilo, Hawaii, airport. It reads, in part, “Be Responsible. No More

Flights to Hawaii.” Yuda, 44, is the former deputy public defender on the

Big Island, and now works in the Family Law Division of the Hawaii Department

of the Attorney General. “I’m doing this,” he tells Capital

& Main, “because someone has to. Our leaders have to accept the

reality of this situation, and what has to be done. We face an existential

threat.”

Yuda says his protest was motivated by the

inactivity of the Big Island’s political leaders in the face of the Covid-19

crisis. On March 20 Hawaii Lt. Governor Josh Green, an emergency room

physician on the Big Island, urged the state to suspend “all non-essential

travel” in and out of the islands. Some airlines have stopped or

limited their service, including Hawaiian Airlines, which suspended its nonstop

service between Maui and Las Vegas.

In the meantime, the Big Island’s County

Council urged Governor David Ige and island Mayor Harry Kim to impose a 15-day

lockdown with a mandatory “shelter-in-place” order if conditions

deteriorate, a move the mayor continues to oppose. In the meantime, another

council resolution urged a limited restriction allowing only “essential

businesses” to operate. Hawaii has a state government, and each

island is a county with a mayor and council.

Kim has argued that it is sufficient for the

island to help businesses use preventative practices and for the county to

sanitize its public areas. In a broadcast statement last Tuesday Kim

announced, “The County of Hawaii will maintain all of its services and

operators as normal.” He called a state directive on restaurant and

church closures “a guide” and declared, “Within this county,

restaurants, bars and places of worship may make their own decision as to open

or close.”

Some Big Island restaurants have begun serving take-out food only, while others still have table service. In the island’s numerous farmers’ markets, booths selling items other than food are now banned, while others selling fruit and vegetables from local farms continue. Hilo’s Farmers’ Market, normally thronged with people, has seemed virtually deserted, while other markets have closed entirely.

Yuda feels more urgent measures are necessary, like those imposed in California by Governor Gavin Newsom. “We can’t carry on like this,” he warns. “Look at what’s happened in Italy.” Hawaii’s economy is more dependent on tourism than any other state’s, and stopping travel to and from the islands would have an enormous impact, especially on workers in the tourism industry. While stringent measures will cause sacrifices, he acknowledges, “You can’t work if you’re dead. We have to put life before the economy.”

Yuda is one of 10 candidates who have filed papers to run against Kim in the next mayoral election-a primary on August 8 and general election on November 3. Yuda says his priorities are public safety and climate change.

…

All photos copyright David Bacon 2020

Fear at Work

By Kurt Stand

Worry slowly mounted over the past few weeks – but worry about what? I work at a bookstore that is part of a restaurant and event space. Since the New Year there has been – like the spread of coronavirus itself — growing concern about the disease, slight at first, then becoming deeper and more profound. For some, the danger has seemed exaggerated, for others danger signs were seen everywhere. By contrast, simultaneously a fear spread shared equally by all my co-workers – fear of loss of income, loss of job. That economic insecurity, more palpable, more familiar, easier to grasp and discuss, joined the nameless fear of illness. Taken together, we have lived a life of nervous anxiety.

All this contributed to an odd sensibility about customers, those coming in for a meal, to attend an event, to buy a book. After all, unlike a grocery store or pharmacy, no one “has to” go to a restaurant and so we wondered why folks might risk their health by going out to eat. Yet of course, we all wanted them to come, because if they didn’t our jobs would be gone. Initially, despite the looming threat, people came. Then, overnight, there was a drop off. Events were hit first, with attendance down and then cancelled. As news reports announced the virus’ arrival in the vicinity, numbers eating out fell more. And with that, so too did book purchases – even though some bought in case they should have time on their hands, others said, quite sensibly, now might be the time to read books that for too long have been sitting on a shelf at home. Servers, reliant on tips, were most impacted. Each day, more staff had shorter hours. Each day there was the hope people wouldn’t be sensible, they would come in, mixed with the fear that someone infectious might enter too and infect us. Both the reality and what we thought about that reality became unsustainable as the news worsened hour by hour.

New rules were set – groups seated at a table had to be of six or less, booths and tables where diners sat had to be separated by an empty one; people should not sit or stand at the bar. All rules that proved hard to enforce. What do you say to two couples with three children who come for a meal? With a sense of foreboding, loud, boisterous crowds drank away at the bar one evening. The next, according to the rules, no bar service. Finally, the announcement: the governor declared all restaurants closed until the public health crisis passed. The last day, our regulars who come by themselves either to work with a cup of coffee or to have breakfast alone but not alone, all showed. Then the curtain closed.

The Governor’s decision was the correct one, no doubt. Public health is another way of describing taking care of each other. But it is not an easy road. While it is true no one has to eat out, it is also true that a shared meal outside of one’s home has an intrinsic value that can’t be easily measured. So too does browsing through a bookstore before making a purchase. The loss of such, when added to all the other closures involved in a quarantine, is real. It is a loss those of us who worked at this restaurant share in our own private lives.

I began by writing that I work at a bookstore, I now have to add an “ed” to that word. At the stroke of a pen, we were unemployed. For some the loss is harder than others – one co-worker was laid off from another job, her husband’s hours were cut on a job that won’t last much longer either. I wished her luck as she left with her child, blithely unaware of what’s going on because of the brave, friendly face she wore. I have my own challenges, as do we all living within that palpable, familiar territory of unemployment, of income loss and just the sense of loss.

And meanwhile, the nameless worry about our health, the health of our family, friends, neighbors, remain. As does the unanswered question: what will we do about it?

…

If you have thoughts about “Life in a Pandemic” please let the co-editors of the Stansbury Forum hear from you by using the “Share you opinion, leave a reply” below.