The Narrative of Change

By Gary Phillips

Trying to get a breath in a time of COVID 19 and knees to the neck.

I belong to several dues paying mystery writer associations. These groups do not have the collective bargaining power for its membership like my white-collar Hollywood union the Writers Guild of America (WGA). The WGA has a past when its members got in the face of the studio bosses and some got their heads knocked in for their efforts and others blacklisted. Different then from the WGA, these aforementioned associations don’t exact a floor for book advances, set a standard pay for a short story of a given length, or seek to establish working conditions for the writer – which in the case of prose writers as distinct from script writing; it’s a solitary undertaking. But not for nothing the Mystery Writers of America (MWA), a national board I once served on as well as past president of the local chapter, does have as its motto, “Crime doesn’t pay…enough.”

To that end the 75-year-old MWA has used the bully pulpit to advocate for a better status of genre writers, intervened in contract disputes, called to task shady publisher practices, and more than anything, provided a way for established pros to interact with first timers or those looking to get published. This through formal talks and seminars as well as bending an elbow at a neighborhood tavern or the bar in the evening during a mystery convention. And like the history of a lot of unions, the MWA wasn’t always diverse. It would be fair to say the MWA was something of a white old boys club for many a year. In fact, Sisters in Crime (SinC) was founded in 1987 by 26 woman crime writers including bestseller Sara Paretsky specifically to address the frustration they had with the obstacles they faced in publishing, and not receiving their fair share of book reviews in a field then dominated by male reviewers.

Today matters are different. There is not only diversity of gender and race/ethnicity on the board of the MWA as well as sister misters on the SinC board, the membership reflects a changed landscape of the types of writers penning these stories. While the police procedural is still told, it could be a story of cop who’s a black woman confronting departmental racism to do her job right. Or about an Asian-American private detective who not only is perceived a certain way by others but is investigating the questionable death of a suspect at the hands of the police or some other so-called authority.

No surprise then when in 2018 the MWA awarded former prosecutor turned author Lina Fairstein its Grand Master award and the membership rose up in opposition. Fairstein to many, me included, helped railroad, along with the police, five black and brown teenager into prison for serious time, convicting them of rape and beating a victim half to death in a “wilding incident” in the infamous Central Park Five case. A case where DNA finally exonerated the now grown men and the city paid out $41m in a settlement. The award was soon rescinded.

Fairstein who has a solid record of pursing justice for years in cases of sexual offenses, maintained the youths were involved in some way in the rape in an op-ed piece she wrote for the Wall Street Journalin June 2019. Really the surprise was the MWA board picking Fairstein and claiming not to know the controversy surrounding her.

Now in the wake of nation-wide protests sparked by the death of George Floyd, captured agonizingly on smartphone video, by fired Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin (now charged with 2nddegree murder), the MWA and SinC (and I’m a sister mister) have both stepped up. The organizations issued statements in support of efforts at reform of the police.

From SinC’s statement, “The murders of Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery and George Floyd are only three recent reminders of the 400-year history of violence visited upon Black people of the United States.”

“Listening leads to understanding, and action leads to change,” the MWA’s statement read in part.

On a listsev I’m part of, Crime Writers of Color, various discussions fly back and forth via email among the loose-kinit group – some of whom are part of the MWA and SinC. The morning following the publishing of these statements, folks on the listserv heard of examples of pushback from the membership, and the nature and character of such was bandied about.

More importantly, reality demands that writers of color and their white colleagues have to re-evaluate what they write and how in they tell the story. There is no getting around the way in which black and brown communities are policed, be the cops white or not or a mixture as was present at Mr. Floyd’s demise. In this time of the virus that too will have to be depicted in some way in our fictions. Yet not every mystery story has to be about that (though I can imagine a story where a murderer kills someone and tries to make it look like complications from COVID) or the use of excessive force and race. But me and my fellow crime writes are challenged to consider the point of view, of who is telling the story and thus who controls the narrative…from the hardboiled to the cozy.

Fiction doesn’t bring about change. Clearly it’s because organizations such as Black Lives Matter, L.A. Community Action Network, Stop LAPD Spying Coalition and others being in the streets and testifying at police commission hearings, let alone what’s happening now, has culminated in the Mayor of Los Angeles proposing a $100-$150m cut in the police budget (not a decrease by the way) and redirecting those monies to “jobs, education and healing.” Fiction can though reflect those changes. It has no choice if it’s to remain relevant and resonate.

…

Washington Farm Workers Become Covid-19 Guinea Pigs

By David Bacon

“The lives of these workers are being sacrificed for the profit of growers”

On March 12 a H-2A visa guest worker living in a Stemilt Growers barracks in Mattawa, Washington, began to cough. He called a hotline, was tested and found out he had COVID-19. He and five of his coworkers were then kept in the barracks for the next two weeks.

A month later three Stemilt H-2A workers in a barracks in East Wenatchee began to cough too. Before their tests even came back, three more started coughing. Soon they and their roommates were all in quarantine. Doctor Peter Rutherford of the Confluence Health Clinic called Stemilt and suggested that they test all 63 workers in the barracks. Thirty-eight tested positive. Then some of those workers who’d tested negative began to test positive too.

Since the H-2A workers infected in the Stemilt barracks arrived in February, and didn’t manifest symptoms until March and April, they must have contracted the virus in the U.S. Guest workers, therefore, are getting infected once they arrive.

The novel coronavirus continues to spread throughout Central Washington. By mid-May rural Yakima County had 1,203 cases – 122 reported on May 15 alone – and 47 people had died. The county has the highest rate of COVID-19 cases on the West Coast – 455 cases per 100,000 residents. For over a week now, hundreds of workers in the same area have been walking out of the apple packing sheds to demand better protections and more money for working in a situation where they may be exposed. Two have now begun a hunger strike.

“Workers are trying to call attention to the danger to the whole community,” says Rosalinda Guillen a longtime farmworker organizer and director of the advocacy group Community to Community. Meanwhile, thousands more H-2A guest workers are scheduled to arrive in the area, first for the cherry harvest and then to pick apples.

H-2A workers (named for the visa program through which they enter the country) are recruited to work in the U.S. on temporary contracts; they can only work for the employer that recruits them and must leave once the work is done.

For the last decade prefab barracks have been springing up in the middle of Washington’s blossoming apple trees, in orchards often miles from the nearest town. Inside, H-2A workers usually sleep in bunk beds, four to a room, and cook their meals in a common kitchen. Some barracks are ringed by a chain link fence topped by barbed wire, while others have no barriers. If workers want to go into town to buy groceries or to a clinic, they depend on the grower to provide transportation.

The fate of thousands of these workers is at stake in a regulation handed down last week by Washington state’s departments of Health and of Labor and Industries that permits housing conditions that could cause the virus to spread rapidly. Sleeping in bunk beds in dormitories, according to these state authorities, is an acceptable risk. Yet according to Chelan-Douglas Health District Administrator Barry Kling, farmworkers are more vulnerable to getting COVID-19 because they live in these very close quarters. “The lives of these workers are being sacrificed for the profit of growers,” Guillen charges.

Washington State ignores the science

The barracks for Stemilt’s infected workers, like those housing thousands of others, are divided into rooms around a common living and kitchen area. Four workers live in each room, sleeping in two bunk beds. Stemilt says that it has 90 such dormitory units in central Washington, with 1,677 beds. Half are bunk beds.

Maintaining physical separation, especially in labor camps, “will be impossible under conditions H-2A workers typically experience in the United States,” concludes a report in April by the Centro de los Derechos del Migrante (CDM — the Migrant Rights Center). There is no testing for H-2A workers as they enter the country, and until the infected group was found in Washington, there was no testing for them here either.

According to Drs. Anjum Hajat and Catherine Karr, two leading epidemiologists at the University of Washington, “People living in congregate housing such as the typical farmworker housing … are at unique risk for the spread of COVID-19 because they are consistently in close contact with others … crowding increases the risk of transmission of influenza and similar illnesses. If individual rooms are impractical, the number of farmworkers per room should be reduced and beds should be separated by 6 feet. Bunk beds that cannot meet this standard should be disallowed.”

Washington’s state agencies decided to ignore Hajat and Karr’s testimony, however. In contrast, the same scientific analysis was the basis for a decision by Oregon’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration banning bunk beds. Its regulation issued in May tells employers: “Do not allow the use of double bunk beds by unrelated individuals,” and “beds and cots must be spaced at least six (6) feet apart between frames in all directions.”

Oregon authorities resisted pressure from employers to change the rule, but after a Farm Bureau survey of 323 growers claimed that it would result in losing housing for 5,000 farmworkers, its implementation was delayed until June 1.

Oregon, however, isn’t even among the top 10 states importing H-2A workers. California growers last year were certified to fill 23,321 farm labor jobs with H-2A recruits, yet no agency keeps track of the number of workers sleeping in bunk beds less than six feet apart. How their health has been impacted, therefore, is basically unknown.

Washington’s growers, however, have become much more dependent than California’s on bringing in H-2A workers. Last year employers estimated that 65,358 people were employed picking apples in Washington, making it by far the largest apple-producing state in the U.S. Its growers were certified for 26,226 H-2A workers. The vast majority worked in apples – as much as a third of the workforce. One company alone, Zirkle Fruit Company, was certified for 3,400 workers, while Stemilt was certified for 1,517.

The state’s new rule for housing those workers says, “Both beds of bunk beds may be used,” for workers in a “group shelter,” consisting of 15 or fewer workers who live, work and travel to and from the fields together. Most Washington State growers would have little trouble meeting this requirement, since their barracks arrangement normally groups four bedrooms in the same pod. Stemilt also has vans that normally hold 14 people, conveniently almost the same number as in the bed requirement. A work crew of 14 to 15 workers would not be unusual.

Who benefits from the new regulation?

By framing the bunk bed requirement in this way, Washington’s Department of Health effectively told growers that they did not have to cut the number of workers in each bedroom, and in each dormitory, in half. The rules of the H-2A program require growers to provide housing. If the number of workers safely housed in each dormitory were halved, growers would have two options. They could build or rent more housing, which would be an additional cost. Stemilt, with 850 bunk beds, would have to find additional housing for over 400 workers, and Zirkle perhaps even a thousand.

Dan Fazio, head of the Washington Farm Labor Association (WAFLA), one of the largest H-2A contractors in the U.S., called restrictions on beds to keep workers safely separated “catastrophic” and “a political stunt by unions and contingency-fee lawyers.” (Attempts to reach Fazio and other grower representatives for comments for this story were unsuccessful.)

Alternatively, growers could bring fewer H-2A workers to the U.S., and instead hire more workers either locally, or attract workers living in other parts of the country. This is what growers did until the H-2A program began to expand rapidly 10 years ago. In 2010 they were certified for only 2,981 guest workers. “Farm workers living in California and other states knew there were jobs here, and they’d come,” explains Ramon Torres, president of Washington’s new farm labor union, Familias Unidas por la Justicia. “Most of them had been doing this for many years. But when growers started hiring H-2A workers, they stopped coming. They couldn’t spend hundreds of dollars to get here, and then find out that the jobs were already filled.”

If the number of H-2A workers were cut in half because of the bunk bed requirement, however, Fazio and WAFLA would lose money, since their income is based on the number of workers they supply to growers. Last year WAFLA brought 12,000 H-2A workers to Washington, charging growers for each worker (although it doesn’t disclose publicly how much).

WAFLA has made the H-2A program very attractive, helping to find contractors to build barracks, taking care of paperwork required for government certification and even pushing for lower wages. In the apple harvest most workers are paid a piece rate that used to reach the equivalent of $18 to $20 hourly. In 2018 WAFLA asked the state Employment Security Department (ESD) and the U.S. Department of Labor to eliminate any standard for piece rates for H-2A workers, effectively slashing wages by up to $6 per hour. The ESD and DoL agreed. Fazio boasted, “This is a huge win and saved the apple industry millions.”

Many of the growers’ H-2A barracks were financed with Washington state funds that are allocated for building farmworker housing. Daniel Ford at Columbia Legal Aid, Washington’s legal service organization for farm workers, protested to the state Department of Commerce that growers shouldn’t be allowed to use public funds, since the state’s own surveys showed that 10 percent of farm workers who are Washington residents were living outdoors in a car or in a tent, and 20 percent were living in garages, shacks, or “in places not intended to serve as bedrooms.” The department, however, refused to bar growers from using state subsidies to house H-2A workers.

Immigration status makes H-2A workers vulnerable

One 2017 case convinced many farm worker advocates that the state had no enthusiasm for protecting the welfare of H-2A workers. Honesto Silva, brought from Mexico to harvest blueberries, collapsed in a field belonging to Sarbanand Farms near the Canadian border, and later died. According to a suit filed by Columbia Legal Services against Sarbanand Farms, Nidia Perez, who supervised workers on behalf of the company’s recruiter, told them that they had to work “unless they were on their death bed.” Yet the Department of Labor and Industries announced that Silva had died of natural causes, and that the company was not responsible. Labor and Industries fined Sarbanand Farms $149,800 for not providing breaks and meal periods, and a local judge even cut that in half.

Unions and worker advocates charge that the immigration status of H-2A workers makes it difficult and risky for them to complain about conditions in the barracks or at work that would expose them to the virus. If an H-2A worker is fired for complaining or protesting, they lose their visa status and have to leave the country immediately, at their own expense. This took place at Sarbanand Farms where 70 workers protested the death of Honesto Silva. They were fired, thrown off the company property, and had to leave the U.S.

Guest workers who complain are often blacklisted and denied jobs for the following season. One large recruiter, Consular Services Inc. (CSI) – a company closely associated with WAFLA, brings more than 20,000 workers to the U.S. every year. It has them sign a pledge that authorizes a blacklist: “I understand that if I don’t follow the rules at work, in housing or conduct, or my productivity on the job isn’t adequate, the boss has the right to fire me and I will lose all the benefit of my work visa, I will have to go back to Mexico, and the boss will report me to the authorities. This will obviously affect my ability to return legally to the United States in the future.”

The Centro de los Derechos del Migrante report casts doubt that the bunk bed regulation proposed by Washington state’s Department of Health, even with its weakened protection, can be adequately enforced. “The problem with protecting workers merely by promulgating regulations,” it emphasizes, “is that regulations cannot overcome the profound power imbalance between employer and worker under the H-2A program.”

That vulnerability, however, makes immigrant labor attractive to employers like Stemilt. Before employing H-2A workers, the company employed others whose immigration status made them easy to pressure. In the late 1990s many of its employees tried to join the Teamsters Union, which lost an election to represent them in 1998. One worker testified to the National Labor Relations Board that she worked without legal immigration papers, with the full knowledge of the company, until the union organizing began. “Before we started organizing Stemilt didn’t mind if we didn’t have papers. It is only now that we have started organizing that they have started looking for problems with people’s papers … and it is only now that they have started threatening us with INS raids … being deported is a very powerful threat.”

Fear rose a year later when 562 apple shed workers throughout Yakima Valley were fired for lacking legal immigration status. The immigration-related threats eventually led to the invalidation of the election lost by the union, but Stemilt never had to sign a contract and remains union-free to this day.

Federal government protects growers, so states must act

In the spring of 2019 Community2Community, Familias Unidas por la Justicia and other farm worker advocates convinced the Washington State legislature to pass a bill to force state agencies to require protections for H-2A workers. The bill, SB 5438, “Concerning the H-2A Temporary Agricultural Program,” was signed by Democratic Gov. Jay Inslee. It funded an oversight office and advisory committee to monitor labor, housing, and health and safety requirements for farms using the H2A program. It also required employers to advertise open jobs to local workers. Representatives from Familias Unidas por la Justicia, the United Farm Workers, legal and community advocates, and representatives from corporate agriculture were appointed to the committee.

When the coronavirus crisis began in early 2020, worker advocates asked the Department of Labor and Industries to issue regulations to guarantee the safety of the H-2A workers. Washington state, however, only issued “guidelines” that were not legally enforceable. Familias Unidas por la Justicia, Community to Community, the United Farm Workers, Columbia Legal Aid and the Northwest Justice Project then filed suit against the state, demanding enforceable regulations.

Skagit Superior Court Judge Dave Needy gave the state a deadline of May 14 to answer the suit, and the Department of Health finally issued the emergency regulation permitting bunk beds the day before the deadline. The unions sharply criticized the new regulation. Ramon Torres, from Familias Unidas por la Justicia, said, “We do not agree with this. They are treating us as disposable, as just cheap labor.” Erik Nicholson, vice-president of the United Farm Workers, said, “We are disappointed that the rules remain ambiguous and don’t provide the scope of protections that farmworkers living in these camps need to protect themselves from the COVID-19 virus.”

Additional news: One farm in Tennessee distributed Covid-19 tests to all of its workers after an employee came down with the virus. It turned out that every single one of its roughly 200 employees had been infected.

The Washington court decision will have an enormous impact, not just on the state’s apple pickers, but on farmworkers nationally, because of the huge expansion of the H-2A program in recent years. Last year growers were certified to fill a quarter of a million farm labor jobs, and the Trump administration seeks to make the program as accessible and inexpensive for growers as possible.

Federal enforcement of protections for H-2A workers is almost nonexistent. The CDM report found that every worker it surveyed reported violations of labor rights and contracts. Nevertheless, of 11,472 employers using the H-2A program, last year the U.S. Department of Labor only filed cases against 431 (3.73 percent), and of them only 26 (0.25 percent) were temporarily barred from recruiting. “It’s deeply concerning,” Nicholson said, “that the federal government has been completely absent in ensuring that the essential women and men who harvest our food are protected.”

States have had to step in. California adopted regulations last year for H-2A housing, barring the use of public funds to build barracks. Washington State passed its law setting up a board to review standards and practices for H-2A recruitment. But the bunk bed ruling effectively makes Washington’s law toothless and leaves H-2A workers exposed to the virus.

California’s anti-barracks law would likely be the next one targeted by those growers intent on keeping labor costs low. They’ve already been promised help by the Trump administration, including a promise on a Federal level to cut the legally required H-2A wages. WAFLA’s Dan Fazio predicts, “If that happens, if it’s lowered to the state minimum wage, growers will bring [more] workers up.” The mandated wage in Washington for H-2A workers would be cut by $2.33 per hour under Trump’s proposal.

In a Memorandum of Understanding on May 19 the US Department of Agriculture and the Food and Drug Administration warned that even regulations like the bunk bed ruling might be too much for the Trump administration. The agencies, they said, may invoke the Defense Production Act to override any state actions that cause “food resource facility closures or harvesting disruption [that] could threaten the continued functioning of the national food supply chain.”

Bruce Goldstein, President of Farmworker Justice, a farmworker advocate in Washington DC, called the MOU a “cold-blooded approach [to] the potential for widespread illness and death of farmworkers.” He added, “The Administration is claiming the right to prohibit states and local governments from requiring workplace safety precautions that might reduce the food supply while saving the lives of people needed in the food system.”

Protecting growers’ profits at the expense of the lives, health and wages of farmworkers has been the historical norm. But in the current COVID-19 crisis, calling farmworkers “essential ” acknowledges not just that the country depends on their labor to eat. It also acknowledges that thousands of people go into the fields every day risking the virus. Farmworkers wonder if they then should be treated as vulnerable guinea pigs.

“The logic of declaring bunk beds acceptable is that some degree of infection and some deaths will happen, and that this is an acceptable risk that must be taken to protect the profits of these growers and this industry,” Rosalinda Guillen charges. “And what makes it acceptable? Those getting sick, and who may die, are poor brown people, and the families and communities who will mourn them live in another country two thousand miles away.”

…

Union-Building for the Long Haul – The Tale of Boston Fine Art Museum Security Guards

By Kurt Stand

“I often used to look at the union work as something like walking on the tightrope backwards while juggling without a net … The wire must be made of grassroots. The moment the union high wire artist feels those grassroots under foot, he or she knows they are safe. No matter how high it might seem that they are, in reality, their feet are on the ground. Conversely, if the wire is otherwise and the union artist fails to feel those good old grassroots under foot, they know (or should know) they are ready for a fall, and a mighty big one.” Michael Raysson (pp 155-156)

In those words, Michael Raysson encapsulates the reason security guards at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts were successful not only in organizing a union but also in keeping it alive. His book, The Art of Organizing: The Boston Museum of Fine Arts Union Drive (Hard Ball Press, 2020) tells the story of how the union was able to survive and thrive – and continues to thrive today – even with a turnover in the workforce, turnover in the core group of active members all the while facing the unending hostility of management with its single-minded focus on the bottom line. A management, needless to say, that would have liked nothing better than to eliminate the union altogether. What gives Raysson’s telling of this story added meaning is that he provides a level of personal detail too often lacking in accounts of union building. This isn’t the story of glorious victories or tragic defeats, rather it is the story of everyday integrity and decency, the true bedrocks of unionism.

Although being a security guard was a low-paying job, the job itself was low-stress. Part-time workers were able to follow other pursuits, full-time workers were able to make ends meet through plentiful overtime. Then in 1988, six months after Rayson began working at the museum, management changed tune – the friendly workplace atmosphere ended, strict rules with no purpose other than harassment were implemented, job security and overtime were threatened. It was in response to that shifting reality that Raysson and a few of the other guards began thinking they might need a union.

Implementing that decision required overcoming a major initial hurdle – none of the guards had any union experience and were unsure of what to do and where to go. The labor movement doesn’t have walk-in centers in shopping malls and housing developments offering advice to those who want to start up an organization – so Raysson and his co-workers had to do their own exploring. They found encouraging help from (the then still new) “Jobs with Justice” and from the long-established, still militant United Electrical Workers. However, in their research they discovered an unanticipated problem: the Taft Hartley Act does not allow guards to be in the same union as non-guards – thus affiliation with the AFL-CIO or even independent unions with members in other sectors was prohibited.

They then sought out a union for guards which did provide help with their initial organizing drive. After they won recognition and negotiated their first contract, they discovered that the union they joined wasn’t interested in truly representing them. Disaffiliation came next, after which they created a new independent union, winning recognition all over again and bargaining a contract worthy of the time and commitment already spent. Management attempted to defeat the union at that early stage by withholding dues check-off during the transition to becoming an independent union, but that step backfired – collecting dues member by member – though time consuming, laid the basis for a strong relation between stewards and officers with the entire workforce, in consequence making the union all the stronger going forward.

Most books might end there, but Raysson takes it a step further by giving a picture of subsequent negotiations which provides insight into nature of labor-management relations as a whole. And because he and his fellow unionists began negotiations as complete novices, his advice about how to set demands; resolve internal union differences around when to stand firm, when to compromise; about how to assess the relative strength/weakness across the table, is particularly valuable. The hostile atmosphere they faced while learning is revealed by the simple fact that each negotiation in which the union was successful in gaining improvements resulted in management’s chief negotiator being fired (the one exception lasted two rounds before being terminated). Clearly, the intent of the Museum’s Board was to keep up pressure. The union was small, without full-time officers, with a dispersed workforce as guards typically worked in separate galleries or areas. And they faced off against a behemoth like the Museum Board whose members came from Boston’s rich and powerful elite – yet the union was able to prevail. The reason was reliance on those grassroots, Raysson mentioned, nourished by their approach from the moment they set out to form an independent union:

“It was our job, as I saw it, to sell the guards on themselves, and ‘ourselves all together’ were the superior force and the better force … We had to convince our members that the problem was not a Union, but the type of Union, and that a new independent union was in our best interests and what we really needed.” (p. 56)

At the heart of the union they created were “communicating stewards,” to make certain that every worker (those who joined the union, those who didn’t) were spoken to and were heard. That didn’t mean that there were no internal issues, personal disputes, seemingly irresolvable differences of opinion, but ultimately trust and a need to work together enabled resolutions even when none had seemed possible. Potentially more damaging, a black-white divide almost undermined the union at its beginning. That was overcome by honesty, by looking at the world through the eyes of another – and by the intervention of one worker who stepped up, helped create a bridge and mutual understanding. That worker wasn’t active in the union for any length of time, but he stepped in at a critical time, providing help for the better when most needed. Raysson mentions others who did the same – people whose “small” contributions were as important as the large contributions of members who were more deeply active in the union. That was important with such a diverse work force, multi-racial, multinational, with political views of members ranging from right to left – for it was the multiple points of views and perspectives, the outlook of patient compromisers and push-the-envelope militants that together created a vibrant, living organization rooted in solidarity.

The workers didn’t do this alone – they had help from consultants and labor lawyers, from community members and local politicians, from other unions and activists; yet it was help, nothing more – members of the union controlled their own agenda, their own organization, which is what gave it the strength to survive.

Museum security guards are considered low skilled and easily replaceable, exhibit curators are highly educated, highly skilled. – yet the same management crackdown that caused guards to create a union was also directed at those curators – facing management alone, many were fired, others found their working conditions downgraded. There is perhaps no better explanation of the power of collective action, of unionism then that – and the story behind that explanation all the more reason to read Raysson’s reminiscence.

An Aside that is Central to All

My observation of the Museum after the corporate takeover was that for all intents and purposes, it was run like a small dictatorship or a monarchy. If you went along with the program, I suppose it was a ‘nice’ dictatorship. If you didn’t … you were out of there by the seat of your pants. And just forget freedom of speech.” (p. 29)

When growing up I used to enjoy going to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York – it was free, spacious; walking through the halls and galleries, I was able to lose myself in various pieces of art and from there let my mind wander. I was not and never have been an art student, and though I respect knowledge, what mattered to me most when young was seeing works new to me (even if venerable) to challenge my eyes, ease my thoughts, allow space for my own reflections. The experience was always enhanced by the sense of sharing a yearning for quiet with other patrons, whether those more visual, more knowledgeable than myself, or those similarly there just to get away to a place filled with quiet and beauty apart from the hustle and bustle around us.

Going to museums today is a vastly different experience – they thrive on crowds, on special exhibits designed to attract visitors in ever greater numbers. Along with that are high admission costs, fancy gift shops and pricey places to eat. There are exceptions of course, and even in filled to the brim rooms, the art can be affecting, meaningful. Although the change was gradual, it has been real and noticeable. I never fully understood what that was all about until reading Raysson’s book, for he describes the takeover of museum boards by hedge fund managers and corporate executives, pushing aside the old elites that had run museums in ages past. Those elites were themselves guilty of much, museums had much to answer for by way of theft and a host of other sins. Nonetheless, the institutions themselves were designed to be a step removed from the world of commerce – unlike today’s neoliberal world, where nothing is given immunity to the almighty dollar. And part of the worship of the dollar was expressed in the management attack on the working conditions of those security guards at the bottom of the museum employment ladder. That is not the primary value of this short book, yet it is an important part of the story told and a reminder that when we look at the world through the eyes of workers at the “bottom” of an industry, it often reveals hidden truths the institution would rather conceal.

…

Dear Mr Albence and Mr Benner, (Deputy Directors of ICE)

By Myrna Santiago

In response to the migrant crisis at the US – Mexico border, faculty at Saint Mary’s College of California organized a Borderlands project that entailed spending one week studying the problem first-hand. Two cohorts traveled through the Central Valley, Los Angeles, San Diego, and Tijuana in July of 2018 and 2019 on a fact-finding mission. The professors, from multiple disciplines, met with a wide variety of governmental and non-governmental organizations, including Homeland Security, Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the United Farm Workers, growers’ associations, refugee centers, deported U.S. armed forces veterans, human trafficking groups, faith-based organizations and others, to gain an understanding of the issues that drive thousands of men, women, and children to leave their countries and attempt to cross over al otro lado, to the United States. Upon their return to campus, the faculty have continued to meet and to devise ways to incorporate their new knowledge into their curriculum and their lives. The letter below is part of their efforts to bring attention to the policies the U.S. government has implemented through ICE and how they are putting at risk the lives of thousands of people. Dr. Myrna Santiago, History Department, Director, Women’s and Gender Studies

.

May 15, 2020

Matthew T. Albence,

Derek N. Benner,

Deputy Directors,

ICE

Dear Mr Albence and Mr Benner,

We, the undersigned faculty of Saint Mary’s College of California* who have participated in a Borderlands project designed to understand the issues surrounding immigration from Latin America to the United States, protest in the strongest terms possible the inhumane conditions that migrants and refugees are being subjected to in ICE detention camps. As we speak, more and more children, women, and men detained in the prisons you are responsible for are being infected with the deadly coronavirus and at least one person, Carlos Escobar Mejia, has died from it. None of those thousands of unfortunate souls, already traumatized by the violence, misery, or repression they faced in their own countries and the incarceration experience itself, are provided with any meaningful medical services by the agency that you direct.

The treatment those populations under your responsibility are subjected to is in violation of the most fundamental human rights recognized by international law: the right to be free from torture, the right to bodily integrity, the right to asylum, and ultimately the right to life. It is utterly shameful that your office has done little to nothing to remedy the situation, to release those you are holding pending a fair hearing, and to protect the communities where your incarceration centers are located.

It is obvious that the imprisoned are not the only ones exposed to the virus. Every ICE agent, subcontracted or not, is also at risk of infection. Every ICE employee, subcontracted or not, who goes home at night after being in close contact with migrants and refugees who are already suffering from COVID-19 is taking the risk of contagion to their families and communities after their shifts are over. Thus, the mistreatment your agency inflicts upon migrants and refugees places entire regions at risk.

It is the responsibility of ICE, and you personally as the acting director, to put an end to this situation and to protect the health and lives of the thousands of children, women, and men whom your agency has imprisoned. It is way overdue. A shameful and disgraceful policy has now turned into a death sentence for thousands of innocents. Do the right thing. Provide the necessary medical care for all people incarcerated in your prisons, subcontracted or not. Arrange for fair hearings for all. Release all people ICE is holding until their cases are resolved. Nothing less will do in this emergency.

Sincerely,

Dr. Myrna Santiago, History Department, Director, Women’s and Gender Studies

Dr. Molly Metherd, English Department

Dr. Maria Luisa Ruiz, World Languages and Cultures Department

Dr. Caroline Burns, School of Economics and Business Administration

Dr. Michael Barram, Theology and Religious Studies

Dr. John Ely, Sociology Department

Dr. Zahra Ahmed, Politics Department

Dr. Jennifer Heung, Anthropology Department

Dr. Alicia Rusoja, Justice, Leadership, and Community Program

Dr. Rebecca Anguiano, Counseling Department, School of Education

Yolanda Franco, M.A., Organizational Leadership, Saint Mary’s College Alumna

Karin L. McClelland, M.A., Mission and Ministry Center

*The views expressed in this letter are those of the undersigned. They do not necessarily reflect the views of Saint Mary’s College of California, which is mentioned for identification purposes only.

…

The changing response to Covid 19: are the UK and the US moving in a similar trajectory?

By Anthony Goodman and Sue Goodman

On the 8th May, we celebrated, although remotely for many, the 75th anniversary of VE (Victory in Europe) day. The COVID 19 outbreak is the greatest world-wide emergency since World War 2, and Boris Johnson, Prime Minister has been likened to Churchill in the right-wing press but an out of his depth appeaser in the smaller more left-wing press.

This picture of a rainbow kite flying freely on a breezy day is taking place in a sky free of aircraft and with roads having practically no traffic. It is flying in East London in an area called Wanstead Flats. This is common land owned by the City of London and it is being heavily used by the public during the period when we are allowed to walk for an hour to get exercise whilst staying two metres apart from others. It gives a sense of normality in an increasingly abnormal world.

With British weather it is not uncommon for there to be a rainbow over the Flats. The rainbow has morphed in recent weeks from a symbol of gay pride to include children’s positive image of support for our NHS. All is not sweetness and light, television reporters who are from black and minority ethnicity have been abused and other essential workers spat at and attacked. This is rare but regularly reported.

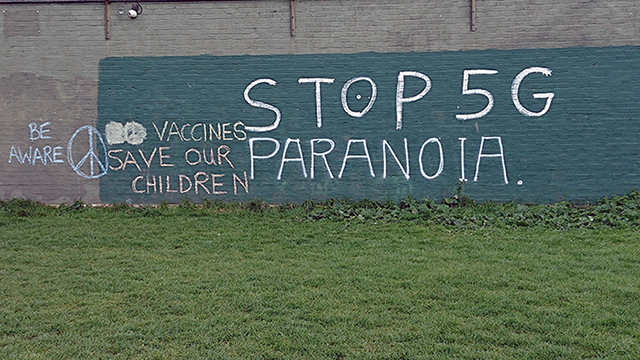

We have a degree of paranoia with anxiety about whether 5G masts have contributed to the spread of the virus. On the wall of the school sports changing rooms on the Flats an interesting exchange has taken place. It started with STOP 5G, then PARANOIA was added below, followed by an exchange over vaccines. SAVE OUR CHILDREN. Amen to that!

We have a new national hero, in the shape of a centenarian ex-soldier who has inadvertently raised £30 million for the NHS by walking around his garden 100 times to represent his hundredth birthday. His initial aim was to raise £1000. A marvellous modest man, they promoted him from Captain to Colonel.

We here may not have a Trump, with 50 States, each with their own local government, but we do have a Boris who is presently trying to create a path out of our COVID 19 lockdown. In the process, Johnson is busy creating a divide between the four nations which make up the UK. Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland each have their own elected devolved parliaments, BUT Westminster is overall the government for the whole of the UK. The First Minister of Scotland was incandescent when Johnson declared that the mantra of ‘Stay at Home’ could be changed to the vague ‘Stay Alert’, stating that this could have catastrophic consequences for Scotland. Johnson pondered whether it would “soon be the time” to impose quarantine on people coming into the UK, begging the question if this was needed, why had it not been imposed at the outset?

“Did he have a carefully, thought through plan? Had this been discussed with anyone with an ounce of logic?”

Johnson is trying to walk the narrow path between the “lock down” for people to stay at home and the right-wing press who want people back at work, whether it is safe or not. Last night, Sunday 10th May, Boris Johnson made a statement to the entire nation. One of the prime suggestions that he made was that those who could not work at home, could go back to work starting the very next day. He had not thought to consult employers about the feasibility of this nor transport managers. Instead, workers were to avoid public transport as far as possible, suggesting that walking, cycling, driving would be an alternative wherever possible.

Schools may be reopened, for a small number of children. Where will safe distancing fit in, who will staff the schools? What about all the other children still at home? Will parents feel that their children will be safe from COVID 19 in such settings? The National Association of Head Teachers said that the planned date of 1 June was not feasible.

Did he have a carefully, thought through plan? Had this been discussed with anyone with an ounce of logic? So many questions arise, not only in parliament, but in many homes around the country. If large numbers of workers were supposed to return to work, did the workplaces know of these plans, and had they had opportunities to prepare their changes in work practices? How were they to travel if the Prime Minister’s suggestions were not possible. What about safe distancing on public transport, especially in towns and cities where the capacity for passengers is about one fifth of the normal available to them? Who looks after the children of these workers, as schools are not open? Many more questions than answers.

Another point made was that people are to be allowed to drive anywhere in England to get exercise. The devolved governments have not made for such a change and will not allow English people across their borders without good reason. There have been examples of English people driving into Wales to go to seaside resorts who have been fined and sent back immediately. Public facilities, such as cafes and pubs are unlikely to be opened for many weeks. Even public toilets will be unavailable.

One of the better policies put forward by the government was to provide 80% funding of wages of those unable to work and some employers have made up the other 20%. This will continue, with some changes until October when it will allow employees to start back on a part-time basis. Known as being furloughed, the goodwill has been tempered by government talk of workers becoming “addicted to the scheme”, as if it had been their choice. A minister talked of needing to wean workers off and the contempt for the workers leached out.

There are serious and deeply worrying aspects that should be the subject of a formal public enquiry. The scandal of the level of deaths in care homes, nearly 10,000 has been shocking. Many are elderly and highly vulnerable but COVID 19 has also killed those with mental health and physical disabilities. Staff in these places have been seriously failed by the lack of personal protective equipment that they needed. The lack of this equipment has been highlighted too in the national health service.

According to the Guardian newspaper, quoting figures from the Office for National Statistics, men in low-paid manual jobs are four times more likely to die from the virus than men in professional occupations. Black people are more than four times more likely to die from COVID 19 than white people. Some of this can be accounted for as the result of economic disadvantage, but not all. This needs to be researched. As this is being written, there has been the tragic case disclosed of a black woman who was working at Victoria Station who was spat at, on the day of the lock down, by a man who said that he had COVID19. She has just died. She had underlying health problems but why was she working out on the concourse?

The government made great score of building up daily testing for the COVID19 to 100,000 per day. This was theoretically achieved once when 40,000 were posted out to individuals on one day to add to other tests. Last week the government admitted that 50,000 tests were sent to the US as there had been ‘operational issues’ in the UK. The advanced warning the UK had from the experience in other European countries was squandered. Will the country be able to move on to a ‘track and trace’ strategy? Time will tell.

…

Nursing home for COVID-19 patients to be run by firm with history of safety violations and lawsuits

By Ed Williams and Rachel Mabe

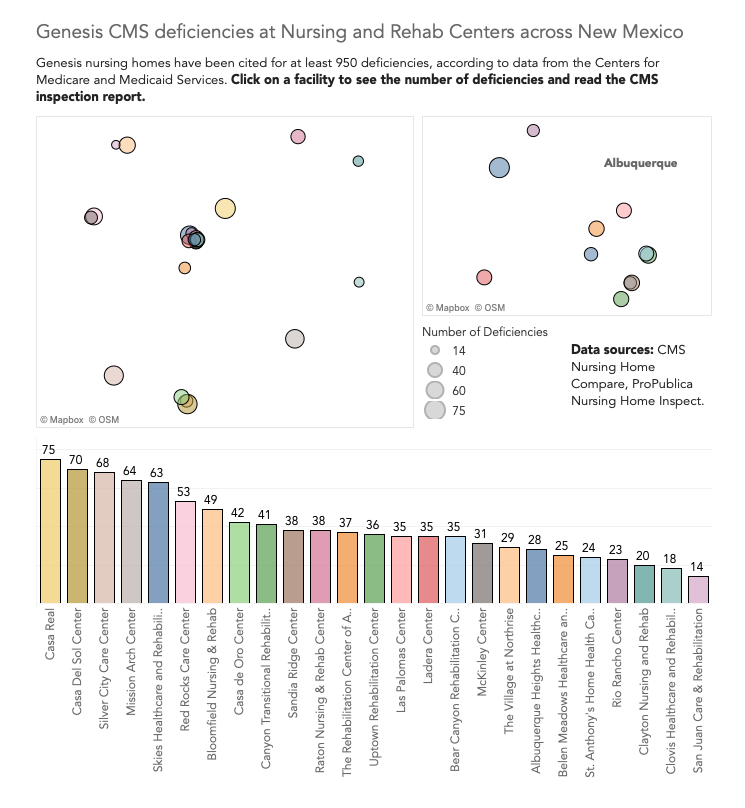

As cases of COVID-19 mount in New Mexico’s nursing homes, Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham has announced that the state will partner with Genesis Healthcare, a for-profit chain that has been denounced by the U.S. Department of Justice as an “unscrupulous provider” that routinely provides “grossly substandard nursing care.”

The plan, announced April 10, calls for elderly nursing home residents who test positive for the virus to be transferred to Canyon Transitional Rehabilitation Center, a 73-bed Genesis-owned facility in Albuquerque with a history of sometimes life-threatening health and safety violations.

In the last four years and as recently as this January, inspectors uncovered a pattern of deficiencies so severe that the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS) assigned Canyon a one-star health rating — the lowest possible score. The facility has also been cited for a complete lack of infection control, massive staff shortages and staff incompetence. Canyon has been named as a defendant in at least 13 lawsuits in state court, alleging negligence, fraud and wrongful death.

Gov. Lujan Grisham did not respond to numerous requests for comment.

The decision to place coronavirus-positive nursing home patients at Canyon — where they will be cared for by Genesis employees — has been lauded by the secretaries of the Aging and Long-Term Services Department and of the Department of Health, who said the move will protect nursing home residents and staff who have not yet been exposed and provide the “treatment and quality of care necessary to give them the best possible opportunity to recover and rehabilitate from COVID-19 infection.” In an email to Searchlight, DOH said that the facility is now in compliance with all regulations.

But the plan has been met with dismay from attorneys, families and elder care experts, who say the facility is woefully unprepared to meet the needs of the state’s most vulnerable patients, even as the federal government scales back nursing home inspections.

“It’s a disaster,” said Charlene Harrington, a professor at University of California San Francisco who researches the business practices of Genesis and other for-profit nursing home chains. “They’re going to get away with bloody murder because they’re going to get top dollar for these patients and with no oversight.”

The state is currently in negotiations to pay the all-COVID nursing home a rate of $600 per patient per day. That money would likely be in addition to high-tier reimbursements from Medicare.

“This is a big business opportunity” for for-profit chains, Harrington said.

Canyon is one of 25 for-profit nursing homes in New Mexico owned by Genesis, a Pennsylvania-based chain that has come under increasing scrutiny by federal investigators in recent years. In 2017, the Department of Justice forced Genesis to pay a $53.6 million settlement after investigators uncovered alleged violations of the False Claims Act.

According to state court filings, Genesis’s New Mexico nursing homes have regularly been tied up in civil cases — at least 65 in the past four years alone. Many of those suits accuse Genesis of “maximizing profits by operating Nursing Homes so that they were underfunded and understaffed.”

Filling the beds

In recent weeks, nursing homes across the country have emerged as hot zones in the coronavirus pandemic, with more than 7,000 deaths of nursing home patients reported nationally as of Tuesday.

In New York, an astounding 2,800 nursing-home residents have so far died amid outbreaks — a death rate made all the worse by chronic understaffing. In early April, CMS officials issued a $611,000 fine and threatened to withhold Medicaid and Medicare funding to Life Care Center in Kirkland, Washington — the first epicenter of coronavirus in the U.S. — after finding a slew of deficiencies that allowed the virus to spread, killing dozens of residents.

An aide in a nursing home facility in Los Alamos makes a call while a resident sleeps on her walker, 2002. Photo by Sam Adams, courtesy of the Palace of the Governors Photo Archives HP.2012.18.734.

The risks are especially acute in New Mexico, which has by far the highest rate of serious deficiencies per nursing home in the entire country, according to a national database compiled by the nonprofit investigative news organization ProPublica. Nearly half are concentrated in the facilities owned by Genesis Healthcare.

In the past four years alone, CMS cited New Mexico’s 25 Genesis-owned nursing homes for nearly 1,000 violations of health and safety standards, according to the database. Forty-one of those deficiencies were issued to Canyon, inspection reports show — double the average number of health citations in other New Mexico nursing homes.

Those federal inspection reports reveal a catalog of dangerously substandard care.

In May 2018, inspectors arrived at Canyon to discover an elderly man with a known history of respiratory problems gasping for air as his legs turned blue from a dangerous drop in oxygen. The nursing home, which at the time was understaffed by 18 positions, had no protocol for responding to such an emergency. Inspectors watched as employees stood by, unsure what to do before finally picking up a phone to call 911 for help.

When the inspectors later quizzed staff on how they should have responded, they were met with a “long silence,” according to CMS documents. Canyon was cited for employee incompetence over the incident.

Authorities have discovered even more egregious violations at other Genesis facilities in New Mexico. Among those violations: catheter tubes lying on the floor; employees reusing dirty syringes; the dealing of illegal drugs (“small bags of white powder”) throughout one nursing home. Inspectors documented infection control and nursing care practices so deficient that residents have developed gangrene or had limbs amputated from untreated wounds.

Indeed, 80 percent of Genesis homes in New Mexico have been cited for substandard infection control, according to a Searchlight analysis of federal inspection data. Among those is Uptown Rehabilitation in Albuquerque, where 16 staff members and 10 residents have so far tested positive for coronavirus. Inspectors had previously found that Uptown failed to properly disinfect equipment, perform regular “IV dressing changes,” or avoid “unnecessary exposure to bacterial organisms,” according to CMS documents.

“There is just a huge lack of lack of training,” said Melanie Bossie, an attorney whose Phoenix-based firm filed several dozen wrongful death and negligence suits against Genesis facilities in New Mexico. “If I walked into a deposition of [a Genesis employee], I can guarantee you they would not be able to tell us appropriate infection control practices.”

Genesis Healthcare declined to comment for this story, stating in an email: “We are not granting interviews at this time.”

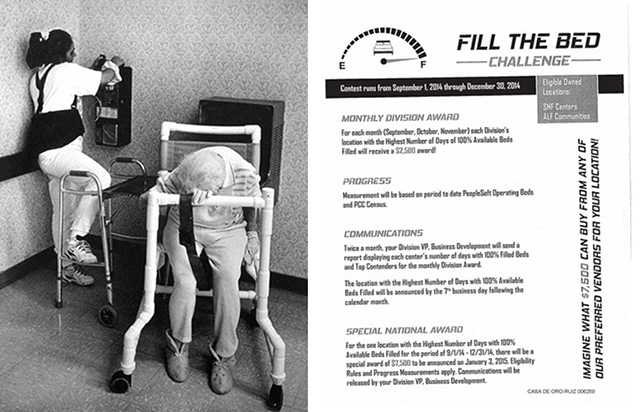

But internal corporate emails obtained by Searchlight show a preoccupation with nursing homes’ “census” counts — the number of residents in each nursing home — with Genesis management directing homes to bring in as many new clients as possible. In 2014, the company went as far as to hold a “Fill the Bed Challenge” contest for its New Mexico and Arizona homes, emails show, offering a cash prize for the nursing home that maintained full capacity for the longest period.

An ongoing case against Canyon alleges that in 2018, a 77-year-old resident was sexually assaulted by another patient and had to wait more than 20 minutes with the “problem patient” before staff responded to her call light. Excessive wait times for staff to respond to call lights has been well documented. In 2019, a CMS reportdescribed a patient complaining that, “The other night a man fell out of bed and was left on the floor for many hours screaming for help.”

Although inspections are overseen by the federal government, states are accorded the right to levy penalties. The average fine in New Mexico is $37,100, compared to $120,000 in Maryland and $199,000 in West Virginia.

Even when a facility receives a fine, follow-up is inconsistent, said Dusti Harvey, an Albuquerque lawyer who for years was an in-house attorney for a major nursing home chain. “Basically they have to come up with a plan of correction for deficiencies: ‘We promise to fix these things in the following ways.’ Sometimes inspectors come back to check and sometimes they don’t. It’s a lot of lip service.”

That’s been the case for Canyon. After CMS inspectors determined that it failed to “provide and implement an infection prevention and control program” in 2018 and 2019, the facility received only one modest fine of $13,605from New Mexico.

Canyon’s record of infection deficiencies has continued unabated. Reports from the previous two years cite a slew of issues, including poor ventilation between the biohazard storage room and the laundry room, equipment not being disinfected between use and residents sitting in soiled clothing for hours.

“Regulators have for years taught nursing homes that infection control just isn’t that serious an issue,” said Mike Dark, a staff attorney at California Advocates for Nursing Home Reform, a nonprofit elder rights organization.

“Now we find ourselves in the middle of a viral pandemic, and in six weeks we’re trying to turn around three decades of lax regulation. It’s just not possible,” he said. “This was a tinderbox and it was ready to go.”

.

Are you a nursing home employee? Do you have a loved one in a nursing home? We want to hear from you—text ‘nursing’ to 505 427 2777 or email reporter Ed Williams at ed@searchlightnm.org.

..

This article comes through the wonderful work of Searchlight New Mexico where is was originally published. It is a source we hope to use again and highly recommend our readers to add to their sources of information.

Searchlight New Mexico is a nonpartisan, nonprofit news organization dedicated to investigative reporting and innovative data journalism.

In a landscape of shrinking media resources, our mission is to focus high-impact journalism on topics of local, regional and national interest in order to allow the public to see into the remote recesses of government and to expose abuses of power.

We believe great reporting empowers people to demand honest, effective public policy and to seek appropriate remedies.

…

Trump and the Militias Consummate Their Marriage

By Max Elbaum

Donald Trump tweets so many outrageous things and tells so many lies, it’s easy for any particular statement to get buried in the shitstorm.

But a presidential call to “liberate” states led by elected officials of the opposition party while Trump supporters carry guns into their state capitols shouldn’t be one of them.

A CALL TO ARMS

In the last three weeks the country has seen a series of “anti-lockdown” protests in states with Democratic governors. Two protesting Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer’s COVID-19 emergency stay-at-home order received the most media coverage. Rifle-carrying members of the Michigan Liberty Militia entered the statehouse, some carrying signs saying “Punish treason by hanging.”

Republicans legislators, instead of condemning these threats of violence, voted to authorize a suit against the Governor for exceeding her authority.

And Trump tweeted “Liberate Virginia,” “Liberate Michigan” and stressed the “Second Amendment” (read: “Bring Your Guns”) dimension of the protests.

Alignment between Trump, the GOP establishment and armed confederate flag-wavers isn’t surprising or new. But these demonstrations saw a level of coordinated action and messaging that went beyond their previous associations.

At Charlottesville, for instance, Trump saw good people “on both sides” of the fascist violence. Numerous Republicans attempted to distance themselves from the naked white supremacists. And the Charlottesville right-wing rally was not organized out of the White House or by top GOP donors and lawyers.

This round was different. The anti-lockdown rallies were part of a coordinated campaign anchored by former White House officials, a number of state-based conservative policy groups, and a coalition of high level GOP donors. Attorney General William Barr has aligned the Justice Department with the protesters’ goals. From Fox News to talk radio the entire right-wing media machine promoted the actions.

Most important, Trump’s tweets signaled that the White House itself backed the rifle-carrying militia component of the protests. His message was a call to defy legal authority and to oust elected officials not to Trump’s liking.

Trump’s tweets were immediately embraced as a “call to arms” throughout the insurrectionist right wing. There was an immediate surge in twitter posts about the President and the “boogaloo” (a term denoting armed insurrection in the world of the conspiracy-theory infused right).

It’s the new normal: armed fascists intimidate elected officials who oppose the President as Republicans either stay silent or – like Trump himself – egg them on.

WHY NOW?

The tightening of the Trump-GOP-Militia embrace is rooted in the way the COVID-19 crisis has affected Trump’s re-election plans and, beyond that, the underlying agenda of the ruling class faction his administration represents.

Pre-pandemic, Trump and his team were confident they had a formula that would win the President a second term. Run on racism and a “humming economy.” That the economy was far from humming for the majority was of little concern. It was benefitting enough sectors in battleground states that – combined with those roped in by MAGA-brand bigotry and with aggressive voter suppression – he would win a majority in the racially skewed electoral college.

COVID-19 has thrown that plan up in the air. The economy is in shambles and all but certain to be in trouble through the election. Trump’s China-bashing resonates in many sectors, but so far hasn’t proved sufficient to erase awareness of Trump dismissing the danger of COVID-19 and doing nothing about it for eight crucial weeks. And his rally-substitute daily press briefings have been a disaster, putting his self-centeredness and bleach-injecting ignorance on display.

PIVOT TO AN “ANTI-LOCKDOWN” MESSAGE

A repackaging of the racism, xenophobia, and all-wealth-to-the-rich core of Trumpism was required. The result, insightfully dissected in a recent column by Thomas Edsall, puts “anti-lockdown” at the center:

“…offers something for everyone: small-business, concerns for the working class, anti-elitism for resentful rural whites, fetishism of guns for NRA, dislike of government for traditional conservatives…. anti-quarantine protests will distract the electorate. If the election is a fight between Trump vs governors who refuse to open their economies, Trump doesn’t have to defend his record on Covid-19. He’s an advocate for liberty! [He] will frame the 2020 election as a choice between the pro-open economy Trump versus the Washington insider #BeijingBiden who is complicit in China’s efforts to hurt working class Americans.”

It is a powerful message with the potential to influence large numbers well beyond Trump’s base. With the economic crisis deepening millions have to worry about how to feed, clothe and house themselves and their families as well as keeping them healthy. Government assistance is totally inadequate, and even if our side makes the maximum gains possible under the current balance of forces, it is likely to stay that way. So sentiment in favor of “getting back to work” – even with major health risks – is likely to grow.

NEED FOR SHOCK TROOPS

But Trump’s problem is that his inaction and blunders – combined with effective messaging by public health experts, Bernie Sanders, and a host of progressive, labor and community-based organizations – means the majority is still concerned about “reopening too soon” and favors protecting people’s health. After an initial bump, the President’s approval rating has started to sink, even in battleground states.

So the Trumpists’ looked for a way to jump-start their adjusted message. For that Fox News and twitter are not enough. Drawing from their anti-Obama Tea Party playbook, they decided it was time for actual physical demonstrations to gin up their base, grab headlines, and infuse every news cycle with their frame on the 2020 contest.

But who is going to go out there in a crowd with no social distancing, no masks, and a message that, at least initially, is not going to be popular? Certainly that’s not a risk big funders, GOP lawyers and elected officials are going to take!

Who do you turn to? How about blatant white supremacists, conspiracy mongers, confederate flag-wavers, anti-vaxxers, and armed militias? These are the people willing to defy public health regulations, pose for cameras brandishing weapons, and carry signs that say, “Sacrifice the Weak.”

So the welcome mat was put out for them by the President himself.

Juan González drew the appropriate conclusion on Democracy Now!:

“I’d like our viewers and listeners to ask themselves a question: If hundreds of African Americans or Latinos showed up in cities around the country brandishing automatic weapons, what would be the response of the country to this? Why is this being almost accepted and normalized now as a method of protest? …we should make no mistake, that this country is edging closer and closer to neo-fascist authoritarianism.”

A DEEPER LEVEL: STAVE OFF RADICAL CHANGE

There is a deeper level as well. Unlike the narcissist in the White House, the people in the top echelon of the fossil fuel industry, the military-industrial complex and the leading right-wing billionaires have bigger concerns than what happens to Trump individually. To them, he’s just the best choice for implementing their agenda of transferring more wealth to the 1%, more austerity for the 99%, doing nothing about climate change and maintaining U.S. global hegemony through military might. Trumpism is also their ideal vehicle for suppressing opposition to this unpopular program by smashing the labor movement and undermining the power of communities of color through large-scale disenfranchisement, incarceration and deportation.

These parasites aren’t haters on Joe Biden. He’s not their first choice. But they could easily live with a President who carried out the “back to the old normal” program that Biden often indicates is his vision of the future.

But the heavyweights in the Trump coalition do not believe a Biden administration could pull it off.

Those who guide Trump to power are closely attuned to the political winds and they can count. They recognize there is growing support for Medicare for All, a Green New Deal, and an end to mass incarceration. They see that that the pandemic is sparking tenant organizing, rent strikes, job actions, and worker strikes that demand protections for renters, workers and the poor way beyond anything that existed pre-COVID-19.

They know that even before the pandemic people under 30 were the most left-wing generation in decades. They see that COVID-19 fightback efforts like Bernie Sanders’ post-campaign stance, The People’s Bailout (whose principles have over 100 congressional endorsers), and many others are pushing demands for structural change into the mainstream. They notice that even the major liberal media are carrying critiques not just of the disparities in the way COVID-19 is impacting different populations but of longstanding inequalities in U.S. society. They see handwriting on the wall as labor organizations support incarcerated people, domestic workers ally with LGBTQ organizations, climate justice activists rally for immigrant rights and a general spirit of “social solidarity” builds among a host of vulnerable and less vulnerable sectors.

They observe the New York Times running a major piece titled “The America We Need” which more or less promotes Bernie’s program without Bernie. They monitor demographic change and know that their core base among older whites is declining while the country’s proportion of people of color is growing.

THEIR NIGHTMARE IS OUR DREAM

They add it all up and see a Biden win not as a safe harbor but as a dangerous open door. They believe coming out of the pandemic there will be irresistible pressure on a new administration to provide universal health and economic protection for working people, tax the wealthy, tackle climate change and restore voting rights.

They fear even small steps in those directions would start an avalanche capable of toppling their already shaky neo-liberal order.

So their faction of big capital goes all in for Trump and the GOP, and deploys fascist militias as the shock troops of their campaign.

Historical experience shows that when a powerful wing of a ruling class throws in with grassroots fascists, a fascist or fascist-like regime moves from back-drawer possibility to imminent danger.

We need to be as clear-eyed as our enemies about the stakes in the current polarization, the possible roads ahead, and where the pivot point of battle lies.

They think November will mark a choice between two roads.

I agree.

…

First ran in Organizing Upgrade

GUEST WORKERS ON FARMS STAND IN THE EYE OF THE COVID STORM

By David Bacon

No to family immigration, but yes to guest workers

On April 21 President Trump announced in a tweet that, while stopping almost all kinds of legal immigration for at least two months, he was placing no limits on the continued recruitment of H-2A guest workers by growers. Trump claimed the spreading COVID-19 pandemic made his order necessary, but he cited no evidence to show that a ban covering all forms of family-based migration would stop the virus’ spread, while leaving employer-based migration unchanged would not exacerbate the pandemic.

Trump has repeatedly declared his support for the guest worker program. In a 2018 Michigan speech he told a grower audience, “We’re going to let your guest workers come in, because we have to have strong borders, but we have to let your workers in … They’re going to work on your farms … but then they have to go out. But we’re gonna let them in because you need them … We have to have them.”

Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue explained the apparent contradiction. He wants Trump “to separate immigration, which is people wanting to become citizens, [from] a temporary, legal guest-worker program. That’s what agriculture needs, and that’s what we want. It doesn’t offend people who are anti-immigrant because they don’t want more immigrant citizens here. We need people who can help U.S. agriculture meet the production.”

This promise is more than election-year politics. It is a big step towards creating a captive workforce in agriculture, based on a program notorious for abuse of the workers in it, and for placing them into low-wage competition with farmworkers already living in the U.S.

It is also a step into the past. Family preference migration, in which immigrants can get residence visas (green cards) based on their family relationships, was won by the civil rights movement. Bert Corona, Cesar Chavez and others convinced Congress to end the bracero program in 1964. They fought for an immigration policy based on family unification, instead of one based on growers’ desire for a low-wage labor supply.

Especially for immigrants coming from Asia, Africa and Latin America, this new system made it possible to unite families in the U.S., settle down and become part of communities. Before that watershed step, people could come from Mexico to work as braceros, but not to stay, and not with families. Immigration quotas favoring white migration from Europe made it very hard for families in general to come from non-European countries.

When President Trump said, in a 2018 meeting with Senator Dick Durbin (D-Ill.), “Why do we want these people from all these shithole countries here? We should have more people from places like Norway,” he was voicing his nostalgia for that pre-civil rights past.

Trump has now suspended the family preference system. Whether it will be reinstated at some point is anyone’s guess. And the H-2A program, which is growing rapidly, is a direct descendant of the old bracero regime. It will continue, given its support in a Congress that is much more conservative than the one in 1964, which abolished the bracero program and established the family migration system. Even Democrats in the current Congress have introduced legislation that would greatly expand H-2A.

Although growers have claimed the coronavirus has created a labor shortage making the H-2A program vital, the program was mushrooming long before the pandemic hit. Last year the U.S. Department of Labor gave agribusiness permission to fill 257,667 jobs with workers brought almost entirely from Mexico, with H-2A visas. That amounted to 10 percent of all the jobs in U.S. agriculture.

The program is five times bigger than the 48,336 jobs certified under George W. Bush in 2005. In some states H-2A certifications now make up more than 10 percent of farmworker jobs. In Georgia growers fill a quarter of all farm labor jobs with H-2A workers.

An agricultural system in which half the workforce would eventually consist of H2-A workers is not unlikely. Florida, Georgia, and Washington are already heading in this direction. Rosalinda Guillen, director of Community to Community, a farmworker advocacy organization in Bellingham, Washington, charges that this expansion “shifts agriculture in the wrong direction, which will lead to the eventual replacement of domestic workers and create even more of a crisis than currently exists for their families and communities.”

The problem with H-2A

H-2A workers are given contracts for less than one year, they can only work for the company that contracts them, and they must leave the country at the end of the contract. If they protest abusive conditions they can be fired and deported. And because they must reapply to come back for the following season, they are uniquely vulnerable to blacklisting.

Investigators from the Centro de los Derechos de Migrante (the Migrant Rights Center, CDM) reported in a detailed study released in March, “Ripe for Reform,” that “many believed that they would not be allowed to return to work in the U.S. at all if they did not complete a contract, regardless of the reason.”

One large recruiter, CSI Visa Processing, with 12 offices in Mexico, brings more than 25,000 workers to the U.S. every year. It has them sign a pledge that authorizes a blacklist: “The boss has the right to fire me and I … will have to go back to Mexico, and the boss will report me to the authorities. This will obviously affect my ability to return legally to the United States in the future.”

“The vast majority of workers start their H-2A jobs deeply in debt,” the CDM reported, some paying bribes as much as $4,500, despite legal prohibitions on such “fees.” They are often housed in barracks on the grower’s property, miles from the nearest town, surrounded by barbed wire fences. “Some workers stated that they needed permission to leave the housing. Others indicated they were prohibited from leaving other than to buy groceries,” the CDM study found.

One worker, Mario, said he was charged $1,000 a month for a bunk bed in a barrack with 30 to 40 other workers. When some workers tried to leave, the boss illegally took their passports. “They didn’t want us to leave or go anywhere,” Mario said.

All interviewees in the CDM report suffered violations of basic labor laws, including receiving wages less than the minimum for H-2A workers and the denial of required breaks. Eighty-six percent reported that companies wouldn’t hire women or paid them less when they did. Half complained of bad housing, and a third said they were not provided needed safety equipment. Forty-three percent were not paid the wages promised in their contracts.

“Fraud and misrepresentation about wages were very common,” according to the CDM.

One worker reported getting paid $1.25 per hour after illegal kickbacks. Another got $400 for a seven-day week, working 11 hours a day. Underpayment over the lifetime of his contract was $11,000. Multiplied by the dozens of workers in an average crew picking fruit or harvesting vegetables gives an idea of the illegal profits available to employers who seemingly have little fear of consequences.

That lack of fear is understandable given the virtual absence of enforcement. In 2019, out of 11,472 employers using the H-2A program, the Department of Labor filed cases against only 431 (3.73 percent), and of them only 26 (0.25 percent) were barred from recruiting for three years, with an average fine of $109,098.

After one H-2A worker, Honesto Silva, collapsed in a field in Washington State three years ago, and later died, 70 of his co-workers refused to go into the fields. The company, Sarbanand Farms, fired them, and threw them out of the labor camp. Because the H-2A regulations require workers to leave the country if they are terminated, firing effectively meant deporting them.

Washington’s new union for farmworkers, Familias Unidas por la Justicia, supported that protest and others by H-2A workers – in 2018 at Crystal View farm and in 2019 at the King Fuji apple ranch. According to Edgar Franks, organizer for Familias Unidas, most of the workers who participated in the Crystal View and King Fuji strikes were not working for the company in the following season.

Favors for growers, COVID for workers

Since his election, Trump has continually tried to make the H-2A program more accessible and profitable for growers. Earlier this year the government dropped a restriction to allow growers to recruit only workers who’d been recruited in the past. Then it suspended a regulation barring growers from keeping workers in the U.S. beyond the end of their old contracts.

Another promised rule change would relax the requirement that companies advertise jobs first to local residents before applying for H-2As. The most important promise was to cut the wage that growers must pay H-2A workers, the Adverse Effect Wage Rate. Set high enough, in theory, not to undermine the prevailing wages of local farmworkers, it actually puts a ceiling on them. If local workers demand wage increases, growers can hire H-2A workers instead.

Low wages put enormous pressure on all farmworkers to go to work, even during the coronavirus crisis. Farmworker families are among the poorest in the U.S., with an average annual income between $17,500 and $20,000-below the official poverty line. Increasing that pressure during the COVID-19 crisis is the fact that half of the country’s 2.5 million farmworkers-those without legal status-were written out of all the relief programs passed by Congress. A quarter of a million H-2A workers were written out of the relief bills as well.