Food chains for the un-housed are stressed

By Robert Gumpert and Peter Olney

The unhoused depend on a network of resources for food. CORVIN-19 has severely affected that network and it’s ability to deliver food where needed.

Below is a list current as of the 20th of March of organizations that are serving the un-housed in San Francisco. If you are one of our readers in the Bay Area we urge you to contact one of the places about helping, in whatever way possible, with food. If you aren’t in the Bay Area check around where you are for similar programs.

Thanks. Robert Gumpert/Peter Olney, co-editors of the Stansbury Forum.

.

Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing

Meals and Food Resources Update 2020-03-20

Here are a few updates on food that have been gone over during our Provider calls this week.

Please support and remind participants that getting food is an essential activity even during the shelter in place order in San Francisco. It’s important to stay as up to date as you can of all the free food options that are still in operation across the city for your participants. While many programs have adjusted how they are providing food, they are still operational. Congregate meal programs such as St. Anthony’s, Glide, and Mother Browns are still feeding people by handing out to-go meals. Participants should utilize these options.

Glide and St.Anthony’s 330 Ellis St, San Francisco

Monday – Friday

Breakfast

7:30 AM – Senior and Adults w/ Disabilities

8:00 AM – General Public

Lunch

Clients will be referred to St. Anthony’s at 150 Golden Gate Avenue for lunch

Dinner

4:00 PM – General Public

Saturday – Sunday

Breakfast

7:30 AM – Senior and Adults w/ Disabilities

8:00 AM – General Public

Lunch

Clients will receive additional to-go bag lunches to take with them as they exit the breakfast line

Clients can access lunch at St. Anthony’s

Mother Brown’s (they maybe looking for delivery persons)

Breakfast: 7:00 AM – 9:00 AM

Dinner: 5:00 PM – 7:00 PM

Martin de Porres 225 Potrero Avenue • San Francisco, CA 94103 (415) 552-0240

Tuesday to Saturday : Noon – 2pm

Sunday and Monday: 9am – 10am

Families

In addition families with school age children should be utilizing the free meal

program that SFUD is operating right now, information found here https://www.sfusd.edu/services/health-wellness/nutrition-school-meals

Food Bank

We would like all programs that were operating food pantries at

their sites to continue to do so or if you have stopped to start again.

Food distribution can be done safely by packing and handing out individual bags

of groceries.

Also — please use the Food Bank’s resources. Here is the link to where you can locate their current and expanding food pantries: https://www.sfmfoodbank.org/find-food/ or on their website use their “food locator tool”

If you already have an account with the Food Bank please reach out to your neighborhood representative to talk through your current needs and what resources they have.

Food Runners

Food Runners has been a great resource to support meal drop-offs at sites of

donations they receive, often of perishable foods. Please connect with them by

emailing dispatcher@foodrunners.org.

Finally, one more reminder to reach out to 440turk@sfgov.org with additional concerns and needs when it comes to your food resources. We also understand at this time that many programs are expanding their own food budget and resources for their participants. We greatly appreciate all that you are doing.

…

Why Sunday’s debate left me cold and angry

By Robert Gumpert

Watched as much of Sunday’s “debate” as I could stand. Bernie started well but soon both candidates were back to more of the same and I turned them off.

For Bernie to win, and perhaps for any Democrat to win in November, he needs to be big – he needs to lead, and the times have offered up the opportunity.

While viewing myself as progressive, even anti-capitalist, I have no thought-out political philosophy or clear political line of thought. I come from a mother who fled the Nazis and who was an artist of many disciplines but as a single mom couldn’t raise a kid without a “real” job. She worked for 25 years as a clerk in a grocery store. She was a member of Local 770 in LA, at the time a “business union” in all bad respects of that term. She was on every picket line. I grew up union and working class but, like her, feel split identities. I did not inherit her intellect, nor fully her courage.

Given 40 years of doing photography, and sometimes journalism, I am convinced of one thing: I get along with the segments of society that I work with because, in part, I am like them.

Why am I saying all this? Simply that is how I listen to the debates. In this time of pandemic and total shit storm in DC I am not interested in Bernie’s views on “Health care for All” and income disparity – I know them. I am not interested in hearing Biden drone on about he can get stuff down and how well Obama’s bailout worked (I remember how Not Well it worked and how so many who should have paid, did not. I remember how so many that should not have paid such a price did, and continue to).

I want to hear what YOU are going to do NOW: today, tomorrow and in the weeks coming to put food and supplies back on the shelves. To get hospitals ready for whatever is coming. To distribute nationally the supplies that some states will have in surplus and others will be short of. If those over 70 are confined to their homes, how will they survive? Who will check in on them? What will the country do if armed vigilantes – Trump cultists – begin trying to take power in local areas. What sort of economic protections will be put in place so the working class (poor and otherwise) and those quarantined. Those whose services are shut off. Those that face eviction, loose their homes, or car. And what about the homeless – how can any plan that ignores the public health risks be effective?

As the immediate problem of illness, containment and care are gotten in hand, thinking and planning for the economic effects must be openly debated. (In a sane world there would already be people working on different avenues of recovery.) If, as happened today (16 March), the market continues its decline because of the administration in DC then adults are in danger of losing their belongings and retirement. The young are in danger of losing their futures. Both candidates should be all over this.

Bernie, as a Senator, is in a position to take the lead. Biden is not. Bernie does not have to retire from the race to do this. He does have to announce that he will now be focused fulltime fon working in the Senate, working with Senators from across the board, bringing in experts to advise, and introducing measures that will effectively deal with the virus, health conditions, hospital needs, and economic issues for both caregivers and victims. He, or another Democratic Senator or expert, needs to be on-air everyday with constructive moves to deal with current and coming developments. He needs to take control of the party, to fill the vacuum, while being inclusive with other members of the Senate. He does not need to ask permission, he is one of the last two Democratic candidates, the only one with real power because he is a Senator.

He needs to run by leading, not campaigning. He needs to be the leader we all need now: a person calming the country’s fears, bringing us together so that we can all move forward.

As a member of this society I want to hear from that person – be it Bernie or Biden. Currently the loudest voice is the TV barker selling hate, distrust and disunity.

…

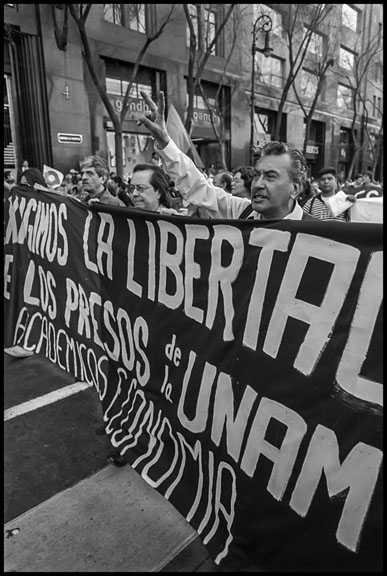

TWO DECADES AGO, MEXICO’S HUGE UNIVERSITY STRIKE DEFENDED FREE TUITION AND ACCESS

By David Bacon

Historic photographs of Mexico’s huge protest over the arrest of students and the invasion of its premier university – all photos David Bacon

Twenty years ago Mexico’s Federal government moved to end the huge student strike at the National Autonomous University (UNAM). The strike, which began in 1999, reverberated far beyond Mexico. Like the WTO protest in Seattle, which took place at the same time, it became a global symbol of resistance to pressure by international financial institutions for austerity policies and the privatization of public services.

Social protests erupting throughout that period adopted radical tactics of taking over public spaces and impeding business as usual. The UNAM strike, however, was not just a brief confrontation in the streets. It lasted almost a year, during which students occupied the campus and shut down the operation of one of the world’s largest universities.

The strike was organized to defend the historic principle of free tuition at Mexico’s premier institution of higher education – with 270,000 students one of the largest and most respected in Latin America. Their key demand was repeal of a newly-instituted tuition in an institution that had always been free. The International Monetary Fund was demanding economic reforms, including ending government subsidies for public services. The government claimed it intended to charge only a symbolic amount – 800 pesos a semester ($85).

But students and university unions feared layoffs and other cost-cutting measures. Even 800 pesos was hardly a symbolic amount for many in Mexico. According to Alejandro Alvarez Bejar, dean of UNAM’s economics faculty, the average 5-member family at the time had an income of 5-6000 pesos (then $625-$750) a month, based on three of the five family members working full time. Millions of families earned less.

Students also charged that tuition and other reforms were part of a larger project to begin privatizing education. And in fact, over the next two decades Mexico’s national government did try to impose corporate education reforms modeled after those in the U.S., much as the students predicted.

In the twenty years following the strike, a virtual war was fought by teachers against the national government, not just over tuition, but to reverse the neoliberal direction of Mexico’s education policies. These battles culminated in the shooting of nine people at Nochixtlan, Oaxaca during a teachers’ strike, and the disappearance of 43 students at the teacher training school in Ayotzinapa, Guerrero. Finally, the conflicts helped fuel the election of Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, eighteen years after the UNAM uprising.

On taking office Lopez Obrador echoed the criticisms and demands of that seminal student strike. “Neoliberal economic policy has been a disaster, a calamity for the public life of the country,” he told the Mexican Congress. “We will put aside the neoliberal hypocrisy. Those born poor will not be condemned to die poor.” And speaking to tens of thousands of people afterwards in Mexico City’s zocalo, he promised that “the so-called educational reform will be canceled, and the right to free education will be established [as mandated by] Article 3 of the Constitution at all levels of schooling.”

The UNAM strike of 2000, therefore, was a class battle, but also one played out in the arena of electoral politics. In the year of the strike, Mexico’s national government was still controlled by its old ruling party, the Party of the Institutionalized Revolution (PRI). The PRI sought to use the uproar over the conflict to prevent a rising leftwing political tide from winning that year’s presidential election.

In two previous national elections the leftwing Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD) almost succeeded in taking power. In 1988 only massive fraud prevented its candidate, Cuauhtemoc Cardenas, from becoming president. In 1994, the ruling PRI campaigned successfully to elect Ernesto Zedillo by identifying Cardenas, who was again the PRD candidate, with the armed Zapatista rising in Chiapas. A vote for the PRI was portrayed as a vote for social stability, against armed conflict and social unrest.

In 2000 the PRI nominated Francisco Labastida, and Cardenas was the PRD presidential candidate for a third time. Labastida called for arresting the students as a response to what he called growing social chaos, much as Zedillo had used the suppression of the Zapatistas. In 1998, however, the mayor of Mexico City, one of the world’s largest urban centers, became an elected position for the first time. The PRD’s Cardenas was voted into this crucial office. After a year he resigned, however, in order to run for president once again. Rosario Robles, a PRD leader, then became mayor – the most powerful woman elected to office in Mexico.

By then the strike had started, and the students had broad public support, especially from the union for the university’s workers (STUNAM – Sindicato de Trabajadores de UNAM). Nevertheless, Mexico’s national PRI government never tried to negotiate with either students or teachers. Instead, it tried to order Robles to use the city police to occupy the campus and arrest students. She refused, saying it would violate the Mexican constitution. Cooperation would also have been viewed by PRD members as a political betrayal.

Instead, after the strike had gone on for nine months, the PRI itself intervened to occupy the campus, using its new anti-drug strike force, as well as army troops in police uniforms. Armed Federal agents arrested and jailed the leaders of the General Strike Committee (CGM – Consejo General de la Huelga), which students had created to organize demonstrations and the occupation of the campus.

After the arrests, Labastida criticized Robles, but in Mexico City the massive repression backfired. People were shocked when the military and police stormed onto the campus, a reminder of the violent and bloody massacre of students in 1968. Mexico, like most Latin American countries, has a tradition of university autonomy, which prohibits presence of government armed forces on the grounds of UNAM. In response over a hundred thousand people marched through the city to protest on February 9, 2000, an event documented in these photographs. During the march, large labor union contingents were interspersed among the students, in an effort to make difficult the arrest of those the government still sought.

The move by the PRI to end the strike killed its chances of winning Mexico City for Labastida. The most popular chant in the huge march was “Not one vote for the PRI!” But the Mexican countryside outside of Mexico City is more conservative, and the government’s message wasn’t intended for chilangos (Mexico City residents) anyway. In small towns and villages, the message of maintaining social stability was intended to keep the continued loyalty of a small, wealthy elite and the votes they controlled.

In the end, Labastida lost, but not to the PRD. People disgusted with the PRI’s long corrupt reign, but manipulated by its social chaos propaganda, voted instead for Vicente Fox, candidate of the rightwing National Action Party. Students and their supporters paid the price. The charges against them were extreme. While the government admitted there was only minor damage to classrooms, 85 student leaders were charged with terrorism and denied bail. Arrest warrants were issued for another 400.

Nevertheless, the PRD’s own relations with student leaders were often very difficult, although many strike participants were sons and daughters of the leftwing party’s members. But the arrests united a very divided opposition. “While there were many disagreements on strike strategy, the government’s action brought everyone together,” said Jesus Martin del Campo, vice-chair of the PRD delegation in the Chamber of Deputies, and a founder of the radical caucus in the national teachers’ union. “We all agreed that arresting the students and occupying the campus was wrong.”

While the arrests and the police invasion of the campus were the immediate issues that brought together city residents, the underlying reason for the outpouring of support was economic. UNAM had been the place where Mexico’s elite educated its children – the one place in Mexican society where they mixed with children of the working class. That mixing was a product of the free tuition and open access, guaranteed in the Mexican constitution in the wake of the revolution at the start of the twentieth century. Beginning in the 1980s, however, the wealthy increasingly began sending their children to private universities, which grew rapidly. They often went on to postgraduate work in the U.S., a choice unavailable to those without the money to pay for it.

The situation for most UNAM students was far different, however. Explained Alvarez Bejar, head of the economy faculty at UNAM, “Young people, when they get married, still live with their parents since they can’t earn enough to live independently. This was a key argument during the UNAM strike, and the reason why it had so much support.” PRD Senator Rosalbina Garabito, an economist, called the tuition proposal part of a larger picture. “The Mexican government has been enforcing an economic policy using high unemployment and falling wages to attract foreign investment,” she said at the time. “Mexican workers have lost 70% of their buying power since 1982. For every 10 new jobs created, 6.7 have salaries below the level workers actually need to survive. We need to democratize the country, not just change political parties.”

It took another 18 years and three elections for the left to win Mexico’s national contest. And when in 2018 Lopez Obrador, himself a former Mexico City mayor, was elected president, it was still far from clear that he could implement his promised change in direction. The student strike of 2000, however, had shown long before that militant direct action could mobilize broad political support for education as a basic human right.

…

Big Changes Ahead. Let’s Be the Whirlwind.

By Max Elbaum

An acknowledgment of the moment: The intertwined Coronovirus and economic crises are escalating at breakneck speed. The political terrain is changing rapidly and immediate fights (here’s Bernie’s Coronavirus Action Plan) take on outsize importance. The structural and political trends discussed in this column (written 24-48 hours before mid-day today, March 13) remain in force. But as we consider and debate those and gear up for a long haul fight whose immense stakes are underscored by the current crisis, it is urgent to stay up to date, stay healthy and take care of one another.

Now to taking a more step-back look.

However severe the current crisis, and whatever the outcome in November, big changes are coming in how the U.S. economy functions, how this country is ruled and its role in the world.

This week’s jolts are big markers of instability. But the Coronavirus pandemic and Trump’s denialist response, the Russia-Saudi oil price war, the stock market meltdown and possible large-scale corporate debt default are not the reasons major shifts lie ahead. They are symptoms of something deeper.

The political and economic arrangement that has dominated the world for forty years is on its last legs.

What is not determined is what will take its place and the pace at which a transition to some new arrangement will occur.

The gains made and strength accumulated by the broad left in the battle over immediate national priorities in next few weeks, between now and the Democratic Convention, and then between August and November, will determine our capacity to influence what is certain to be a high-stakes, conflict-ridden process.

END OF THE “END OF HISTORY” ERA

Thirty and forty years ago a full-of-themselves ruling elite was proclaiming “There Is No Alternative.” They were boasting that their mode of rule marked “The End of History.” They blathered that “free markets” and “less government” (today termed neoliberalism) were going to deliver the goods to all. They confidently asserted that the Anglo-Saxon model of elite-dominated capitalist democracy was going to last forever. The United States, with a few junior partners, was going to ensure permanent order and peace on a global scale.

The guardians of empire really believed these things. They were feeling their oats after vanquishing the 20th century effort to build a socialist counter-system. Capitalist profits were up again after the serious slump and stagnation/”stagflation” of the 1970s.

Resistance from grassroots movements certainly existed, and sometimes won victories for specific constituencies. But the opposition was not nearly strong enough to pose a systemic challenge.

That bubble has now burst. The global financial crisis of 2008 exposed the system’s dysfunction. Bailing out the finance capitalists who caused the crisis while leaving the working and middle classes to fend for themselves was a jolt to public opinion worldwide. The steady rise in inequality since has turned that jolt into a deep well of anger against the powers-that-be. Demographic changes, especially in countries where whiteness and Christianity have long been components of the majority’s “national identity,” spurred powerful racist and nativist movements. Washington’s inability to win any of its endless wars revealed the limits of U.S. power and added to large-scale skepticism about the competence of the political establishment.

The escalating crisis of climate change now hangs over everything.

The Coronavirus pandemic, whose impact is still in its very early stages, does too.

It’s end times for the “end of history/there is no alternative” era. The fight is on over what will replace it.

BITTER POLARIZATION

In the U.S., the tumultuous character of the transition underway has already produced a political polarization unmatched since the Civil War. The Trump coalition is on one side, an anti-Trump camp on the other.

As in the 1840s-1860s, race and racism are at the pivot. But the divide is especially sharp because racial polarization now almost completely overlaps with partisan political polarization; with geographical (urban-suburban-rural), separation, and with a basic information polarization whereby the two camps live in two different factual realities.

The reactionary side of this polarization is united on what they want to replace the current structure of the country.

The driving class force in the Trump coalition — a set of right-wing billionaires, the fossil fuel industry and the military industrial complex — envisions permanent U.S. global dominance based on military force and an even more de-regulated and anti-labor economic model. White supremacy serves as the main lever mobilizing layers of middle- and working-class whites behind this program. To ensure the dominance of this bloc against the will of the U.S. majority and the growing clout of rivals across the globe, authoritarian rule and a strengthened “imperial presidency” is required.

It’s not exactly the fascism of the mid-20th century, but its function and the danger it poses are essentially the same.

The camp opposed to the Trumpists does not share a common vision. At one end of the anti-Trump spectrum is a wing of the U.S. elite whose agenda might best be termed “neoliberalism with a human face”: U.S. society pre-Trump is considered basically sound, all that is needed is to address some unfortunate flaws that produce “too much” inequality, bigotry of various kinds and inaction in the face of climate change.

At the other end is a dynamic insurgent movement fighting for radical change to a “people before profits” society. Some in this movement aim for a New Deal-type capitalism or think in terms of an updated social democracy; others foresee such arrangements as intermediate stages on a road to democratic socialism or revolutionary transformation. The boundaries between these visions and the specific outlines of each are, at least for the moment, very blurry to all except each one’s most fervent ideological partisans. It could hardly be otherwise given the complicated experience of the 20th century radicalism and the wide divergence in left evaluations of what happened and why.

WHAT A TRUMP RE-ELECTION WOULD MEAN

The battle between these warring political forces and agendas is fierce and will go on well into the future. But the outcome of the 2020 election will be decisive in determining which force holds the initiative and on what terrain the next phase of battle will play out.

If the Trumpist camp keeps the White House and retains its Senate majority it will be able to entrench additional elements of a Jim Crow 2.0 authoritarian state. Trump will follow the path already trod by Modi in India, Orban in Hungary and Putin in Russia. The process is already underway here: the lockstep Senate acquittal green-lighting presidential impunity; the installation of toadies and conspiracy theorists in key government positions; deploying large numbers of elite ICE agents to Sanctuary Cities; Erik Prince of Blackwater-notoriety hiring ex-spies to infiltrate progressive groups; tackling the Coronavirus crisis using the information-management playbook of authoritarian states.

A second Trump term means even worse.

THE FIGHT WITHIN THE ANTI-TRUMP CAMP

What will happen if Trump is defeated is far harder to predict. It depends in large measure on a struggle within the anti-Trump camp that is still in progress.

One thing about that struggle is already clear. Unlike the Republican old guard, the Democratic Party establishment has not folded up in face of an insurgent challenge. There are important lessons for left strategy in understanding the reasons for this difference.

Going into 2016, the Republican establishment had no serious program for addressing the economic anxieties and hardships within their political constituency. They had no ideas about how to maintain U.S. global hegemony other than to continue increasingly unpopular endless wars. The allegiance of their mass base had been secured largely by dog-whistle racism for decades, and they were faced with a right-wing populist force that — buoyed by talk radio and Fox News — had been organizing and winning down-ballot elections for years.

So when a demagogue feeding red meat to their already-primed base appeared, the GOP leadership was vulnerable. After a relatively brief and ineffective effort to resist, they calculated there was plenty of upside and little downside in letting Trump take over. His economic policies were going to advance rather than hurt their interests. His racism and sexism would secure the needed mass base. And they believed (their one miscalculation!!) that they could keep his lunacies under control on matters where he might blunder into disaster.

WHY THE DEMOCRATIC “CENTRISTS” HELD ON

The Democratic establishment also had — and still has — no workable plan for building a viable “neoliberalism with a human face” or a stable world order under peaceful U.S. hegemony. They have no compelling narrative to inspire deeply felt mass support. The result in 2016 was the lackluster Clinton campaign, in 2020 it has been the inability of all the “moderate” candidates to stimulate much enthusiasm.

But the dynamic in the Democratic Party differs from that in the GOP in three important ways.

First, the progressive insurgency represented by Bernie and Elizabeth’s Warren’s campaigns had far less infrastructure to build upon than Trumpism had in 2016. These campaigns ran well ahead of, not behind, a buildup of progressive power at the local and state levels (elected officials and their political operations, community organizations on the scale of white Evangelical churches, anything to compensate for the steady decline in trade union membership.) Combined with real weaknesses even in an impressive effort like Bernie’s, this meant we insurgents have less strength relative to the Democratic old guard than Trump had in the GOP.

Second, the Democratic establishment is eager to get the votes of progressives but has no material incentive to embrace us as partners (much less leaders) like the GOP elite had in relation to Trump. The policies we advocate threaten, not advance, the interests of key factions in the Democratic Party: the health care industry and high-tech capitalists, developers and real estate profiteers, the Israel Lobby and more. So the Demoratic elite’s determination to resist insurgency is much greater.

And third is the fear of Donald Trump. This factor pushes the “electability” argument to the forefront of the campaign. There was always a case that Bernie or Warren were at least as likely to defeat Trump as any of the “center lane” candidates, and both candidates consistently argued it. But there were counterarguments too, and with fears of Trump being both intense and well-grounded, the idea of a “safe” choice had the edge. And the appeal of familiarity and risk avoidance was reinforced at a key moment in the primary season by the Coronavirus outbreak and stock market gyrations.

The upshot is that even without a compelling narrative, strong candidate or viable governing plan, the Democratic establishment has been able to maintain its edge.

Joe Biden, a poor campaigner whose only assets seem to be that he is considered a nice guy, evokes the “old normal” of the Obama years, and is the last moderate standing seems on track for the nomination.

Yet as pundits across the spectrum have conceded, the animating ideas in the Democratic campaign – especially those that galvanized younger voters — all came from the left. Polls show that large numbers, in some cases even majorities, who voted for “center lane” candidates support a Green New Deal, Medicare for All and other changes pushed first and foremost by Bernie Sanders. As Bernie said in his press conference acknowledging that he was “losing the debate over electability”: “Our campaign is winning ideological debate.. and winning the generational debate.”

WHAT THIS MEANS FOR A POST-TRUMP PERIOD

The balance of forces within the anti-Trump camp — and how much it can be shifted over the next eight months — will shape the contours of a new administration if we manage to beat Trump. A future column will offer opinions about how matters might play out if Bernie turns things around — a best case scenario for us that we must fight for as long as there is any possibility of winning. But since we have to plan for worst case as well as best case scenarios, I will focus here on the dynamics if Biden is inaugurated President.

The fundamental reality of a Biden administration will be that it has no workable path to put its preferred agenda in place.

On top of the basic fact that Biden is aiming to re-establish a model that has run its course, he will have come to power without a mandate for his backward-looking, “just-tweak-what-we-had-before” program. If he wins, it will be because a U.S. majority rejects Trump and Trumpism, but is not yet ready to pursue an uncharted path to radical change. He may benefit from a moment of national relief, but a Biden administration’s level of popular support will likely be fragile from day one.

Pressure on the new administration will be intense. For starters, the polarization with the Trumpist right will continue. It could even intensify since it is quite possible that significant sectors of the Trump coalition will deny the legitimacy of the election result and turn to a level of resistance, including violence, that throws the U.S. into territory unseen for 150 years.

There will be voices in a Biden administration, in Congress and in the Democratic wing of the corporate elite that counsel conciliation of the racist right or even outright capitulation. But coming off a bitter, smear-filled campaign, and for reasons of partisan survival, there will be incentive to go the other direction. It is a sign of the way current political winds are blowing that a pundit as conservative as David Brooks thinks major moves to the left would be the most likely result:

“Some people are saying a Biden presidency would be a restoration or a return to normalcy. He’ll be a calming Gerald Ford after the scandal of Richard Nixon.

But I don’t see how that could be. The politics of the last four years have taught us that tens of millions of Americans feel that their institutions have completely failed them. The legitimacy of the whole system is still hanging by a thread. The core truth of a Biden administration would be, bring change or reap the whirlwind.

There would be no choice but to somehow pass his agenda: a climate plan, infrastructure spending, investments in the heartland, his $750 billion education plan and health care subsidies. If disaffected voters don’t see tangible changes in their lives over the next few years, it’s not that one party or another will lose the next election. The current political order will be upended by some future Bernie/Trump figure times 10.”

“OR REAP THE WHIRLWIND”? THAT’S WHERE THE LEFT COMES IN

Brooks gets it that big changes are on the agenda. But he is afraid of the whirlwind, while we aim to be the whirlwind.

We will need a whirlwind even to get the changes Brooks lays out. Like many pundits, Brooks dwells in the world of ideas, where a Biden administration doing those things seems a rational choice. But desired political outcomes only come when the world of ideas gets rooted in the world of power. Even to push through the items Brooks specifies — and voting rights restoration, dents in mass incarceration and a big shift in immigration policy need to be added to his racially oblivious list — will require massive pressure from organized grassroots movements; that is, from clout built up outside as well as inside the electoral arena, locality by locality, state by state, and giving due weight to the South and the Black and Latinx communities.

And we aim for more than that. We are for “upending” the current political order! That means turning these kinds of reforms into steps that increase the confidence, political sophistication and unity of a multiracial, all-inclusive working-class movement that fights for them. It means steadily growing the layers of people who view changing this country as part of an international project to make things better for people across the globe.

We have a lot to learn from the way the Trumpists captured the GOP and then won national governing power. We need to scale up in every area to win elections at every level, revitalize the labor and other social movements and build an information apparatus with a greater reach than Fox News and talk radio combined.

The coming eight months give us the chance to make progress toward those goals. And the November balloting is a possible tipping point where even replacing Trump by someone whose goals are not ours can open the door to a new political cycle.

Becoming the whirlwind means embracing a new normal. We’ve made it out of the margins and at least have a foothold in the game. Now each new stage is more challenging than the one before:

Fight for the most aggressive and socially responsible government action in response to today’s global pandemic and the human and economic hardships that fall on the global majority.

No scapegoating China or anyone else.

Stay in for Bernie as long as he does and maximize progressive influence on the 2020 campaign.

Beat Trump whoever turns out to be the Democratic nominee.

Put pressure on a new administration from day one so that the potential of 2020 to become a turning point to a new progressive cycle is realized.

Scale up our infrastructure on every level so that we move that cycle forward as fast and as far as it can go.

Listen to public health experts and stay healthy.

.

“This article is the sixth installment of Max Elbaum’s “This Is Not a Drill” column on Organizing Upgrade.

…

Biden Back from the Dead, Bernie Supporters Fight On

By Peter Olney and Rand Wilson

March 11, 2020

Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders did remarkably well in the Democratic primaries and caucus held in Iowa, New Hampshire, and Nevada in February. Joe Biden, the former Vice President under Obama, candidacy appeared to be fading. Many on the left hoped that after Sanders’ string of early primary victories he would poll strongly in South Carolina and possibly derail the Biden campaign permanently.

But then came Joe Biden’s crushing win in South Carolina on February 29 where sixty percent of the Democratic electorate is African American. Roughly 61 percent of African Americans voted for Biden. Within days, his victory united the corporate wing of the Democratic Party — and Tom Steyer, Amy Klobuchar, and Pete Buttigieg all dropped out of the race and endorsed Biden. Their support cemented the growing consensus among corporate Democrats that Biden is the best positioned candidate to stop Bernie.

Then on “Super Tuesday” March 3, Biden’s political life was truly resurrected with an impressive string of primary victories in ten states including the second largest state in the union, Texas. While Bernie captured four states including the largest in the U.S., California, his path to the nomination has narrowed.

In the space of a week, the campaign of often-doddering Joe is now on track to possibly secure the nomination on the first ballot at the July 13-16 Democratic National Convention in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. His ascendance was further confirmed on March 10 when Biden won four out of six state primary contests including the state of Michigan which was especially symbolic because of its large African American vote and because Sanders won the primary there in 2016. Sanders only won North Dakota and leads in Washington by a narrow margin.

The present delegate count is 861 for Biden and 710 for Sanders with 1991 needed to secure an outright majority and first ballot nomination at the DNC convention.[1]

There are several factors that explain this dramatic turnaround[2]:

- The African American vote. President Obama remains immensely popular in the Black community and by extension his former Vice President Biden is seen a team player who can continue Obama’s legacy. Exit polls showed that Black voters believe that at this moment in history their main enemy is Donald Trump. Because their community faces the racist backlash spearheaded by Trump’s horrible administration, they prioritize the candidate who they believe can defeat him. Black voters make up a significant portion of the Democratic Party base and helped determine Biden’s victories in many of the March 3 and March 10 primaries.[3]

- Neoliberal media assault and corporate unity behind Biden. The news media has been attacking Bernie Sanders and his mildly social democratic reforms since the primary season began. All the corporate moderates lined up behind Biden in a bid to stop Bernie. The decision by billionaire Michael Bloomberg to suspend his campaign after March 3 and offer up his personal fortune and political ground organization to Biden was the final showing of corporate unity.[4],[5]

- Bernie Sanders’ fixed base of support and concerns about beating Trump. Going into Super Tuesday, Bernie’s biggest challenge was to extend his base beyond the 18-29 age group, and the progressives and Latinos who had powered him to strong showings in the early primaries and caucuses in Iowa, New Hampshire and Nevada. Again, exit polls showed that many moderate and conservative older voters were still uncomfortable with Sanders’ social democratic policies and saw Joe Biden as the best chance to defeat Trump.[6]

- Young voters have not turned out. An expected voter surge among younger voters did not materialize and Bernie paid the price on March 3 and 10! Sanders has based much of his strategy on the hope that he could turn out large numbers of young voters. The decline is not only bad news for him, it will also make it more difficult for future-focused issues like climate change to gain political traction. According to the Harvard Institute of Politics, while raw turnout is up in all 12 of the states with competitive elections, the youth vote has only risen in four states, and is flat in two other states. Of the 14 states that held primaries on Super Tuesday, participation by voters younger than 30 didn’t exceed 20% in any state, according to exit poll analyses.[7]

Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren, whose campaign echoed many of the anti-corporate social programs and policies of the Sanders campaign, dropped out of the running on March 5 after placing third behind Biden and Sanders respectively in her home state. Warren appealed to many highly educated upper income liberals who were intrigued with her intellect and detailed policy proposals. Unfortunately, American elections are not a race for the leadership of Mensa International, and Warren failed to break out of this elite, college-educated demographic. Her supporters remain crucial to Bernie’s success going forward and certainly to the essential “popular front” needed to defeat Trump.

Warren’s exit from the presidential race heightened speculation that she could be a vice-presidential choice.

“The nomination of the vice president is about building unity and a partnership that can best govern,” said Larry Cohen, past president of the Communications Workers union and now chairman of Our Revolution, the organization that emerged from the Sanders’ 2016 presidential campaign. “The women who sought the nomination and others easily meet both criteria.” [8]

Where is the labor movement?

In 2016, Sanders garnered the support of six national unions and over one hundred union locals. In 2020 with the support of Labor for Bernie, only three of the national unions that endorsed Bernie last time supported him again and only about 30 local unions have endorsed him.[9] Joe Biden has picked up the support of six major national unions while in 2016 Hillary Clinton was endorsed by almost all major unions including the very powerful public sector unions, NEA, AFT, SEIU and AFSCME.[10]

In 2016, many union leaders felt the outrage from their members because of these early Clinton endorsements. With a very crowded field of candidates up until Super Tuesday, most leaders have had a “wait and see” attitude for the 2020 primary season. Many unions have also established a more participatory and open process for making their endorsement decisions. For example, the International Association of Machinists (IAM) had internal voting by members on endorsements in both the Democratic and Republican primaries. Sixty-six percent of the membership identified as Democrat and the vote was 36 percent for Biden and 26 percent for Sanders (other candidates polled at much lower numbers). An alarming 34 percent of the membership identified as Republican, all of whom went for Trump.[11]

Candidate Sanders remains the clear choice for labor based on his proposed policies for comprehensive labor law reform, fair trade agreements, Medicare for All, and his legacy of vigorous support for organizing and contract campaigns. Election results so far show that Sanders wins Democrats in working class districts. According to the New York Times, “Polling throughout the campaign has shown Mr. Sanders drawing some of his strongest support from voters with household incomes under $50,000; his numbers taper off as incomes rise. A month ago, when he was leading in the polls, people with household incomes of $50,000 and under supported Mr. Sanders twice as much as any other candidate.”[12]

Yet despite his strong base of support in the working class and despite a number of opinion polls showing Sanders beating Trump, many U.S. unions believe that Biden is the best candidate to defeat him.[13] Exit polls coming out of Super Tuesday showed voters siding with Sanders on policy, but voting based on whom they believed could beat Trump.[14]

After his poor showing in Michigan on March 10, the path for Bernie to achieve the nomination now looks unlikely. Hopefully Sanders will continue his campaign, if not for the Democratic presidential nomination, then for a party platform that represents labor’s issues and for the appointment of the top officials who reflect his values. Progressives working on his campaign will continue our fight for the signature issues so well-articulated by Senator Sanders as the Democrats nominating convention approaches in July.

But clearly, if Biden is the nominee, then the vast majority of progressives and most union members will pivot to support him to defeat Trump.

“I’ve said throughout this entire process that what is so important is that we ultimately unite behind who that Democratic nominee is,” said Alexandra Occasio Cortez, Congresswoman from New York who is seen as a leader and rising star of the left wing of the Democratic Party.

The basis of that unity will be the subject of intense negotiations. As Larry Cohen has repeatedly said, “Going forward, we must keep building on our base while finding a way for the two wings of the Democratic Party to work together. If the corporate Democrats are determined to just be anti-Bernie, it will mean a Trump victory. Millions of voters, particularly young voters, are demanding a different United States; they know it’s time we joined the rest of the democracies of the world. We are going to continue to fight for real change in our health care system and real change to address the climate crisis. We won’t surrender our values in the campaign to defeat Donald Trump.” [15]

.

This article on the recent Democratic primaries appeared first in the Italian publication “Sinistra Sindicale”.

[1] “Live results: March 11 primaries,” https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2020-presidential-delegates-tracker/

[2] For excellent post Super Tuesday Analysis see “Organizing Upgrade,” https://organizingupgrade.com/make-a-hard-nosed-assessment-adjust-strategy-and-fight/. Particularly incisive is the analysis of the African American vote by Libero della Piana.

[3] “Exit polls from the 2020 Democratic Super Tuesday contests,” by Brittany Renee Mayes, Leslie Shapiro, Kevin Schaul, Kevin Uhrmacher, Emily Guskin, Scott Clement and Dan Keating, March 4, The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/politics/exit-polls-2020-super-tuesday-primary/

[4] “Corporate Democrats Are Already Punching Left Ahead of 2020,” by Norman Solomon, Truthdig, Dec. 26, 2018, https://www.truthdig.com/articles/corporate-democrats-are-already-punching-left-ahead-of-2020/

[5] “Mike Bloomberg is suspending his presidential campaign, says he’s endorsing Biden,” by Amy B Wang and

Michael Scherer, The Washington Post, March 4, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/mike-bloomberg-drops-out-of-presidential-race/2020/03/04/62eaa54a-5743-11ea-9000-f3cffee23036_story.html

[6] “Exit polls from the 2020 Democratic Super Tuesday contests,” by Brittany Renee Mayes, Leslie Shapiro, Kevin Schaul, Kevin Uhrmacher, Emily Guskin, Scott Clement and Dan Keating, March 4, The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/politics/exit-polls-2020-super-tuesday-primary/

[7] “The youth vote goes missing in 2020 Democratic primaries,” by Bryan Walsh, Axios, Mar 7, 2020, https://www.axios.com/youth-vote-2020-democratic-primaries-db5dbbf3-1295-44ae-9d2a-2283c06fbf02.html

[8] “Democrats Eye a Vice-Presidential Consolation Prize for Women,” by Lisa Lerer and Reid J. Epstein, New York Times, March 9, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/09/us/politics/democrats-women-vice-president.html

[9] See www.LaborforBernie2020.org

[10] For an up-to-date list of union endorsements see:https://intercom.help/unionbase/en/articles/3782859-who-has-endorsed-who

[11] “Joe Biden Wins Endorsement of Machinists Union After Rare Rank-And-File Vote,” by Dave Jamieson, HuffPost, March 9, 2020, https://www.yahoo.com/huffpost/joe-biden-endorsement-machinists-union-163609983.html

[12] “The People Who See Bernie Sanders as Their Only Hope,” by Jennifer Medina and Sydney Ember, New York Times, March 9, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/09/us/politics/bernie-sanders-voters.html

[13] “Biden expands support among unions,” by Alex Gangitano, The Hill, 03/10/20, https://thehill.com/homenews/campaign/486723-biden-expands-support-among-unions

[14] Bernie Sanders Vows To Keep Fighting For Democratic Nomination,” by Amanda Terkel and Tara Golshan, 03/04/2020, HuffPost Politics, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/bernie-sanders-super-tuesday_n_5e5ff8dcc5b6985ec91a5a7f

[15] Author interview with Larry Cohen on March 10, 2020 and comments made in an interview “After Super Tuesday, What Is the State of The Democratic Primary?” by Meghna Chakrabarti and Anna Bauman, On Point, NPR Radio, March 04, 2020, https://www.wbur.org/onpoint/2020/03/04/super-tuesday-state-of-the-primary

International Women’s Day – 1934: Remembrance and History for Today

By Kurt Stand

A Nazi woman-leader declared at a Congress that children’s homes and nurseries should disappear as soon as possible. According to her, “the abolition of children’s homes would promote ‘family life,’ for the woman would be occupied only with rearing children, attending to the needs and well-being of her husband and would not take part in any public activity.”

Such are the blessings which fascism has in store for the German woman. In addition to worsening her economic position, fascism is heaping disgrace upon the women, pushing them back into the position from which they have emancipated themselves through long and hard struggles some decades ago.

Elimination from all public offices and leaving for her only the 3Ks (Kinder, Kirche, Kueche), the children, church, and the kitchen, the double enslavement of the women, by the capitalist state and male superiority, are the gifts which Hitler brought the woman in his Third Reich.

Those words are from an article my Oma wrote in 1934 for Working Woman, a monthly publication of the Communist Party, for the March 8 celebration of International Women’s Day. A friend found it while helping in a search for family immigration records of old – I had never seen this but the words brought back the person who meant so much to me while growing up. Her article was important then, for the true nature of what Nazism represented was not yet fully appreciated so soon after Hitler came to power. And it is important today, because too few remember how central suppression of women was to the fascist project. The nature of women’s oppression and resistance she describes speaks to a continuum visible in current movements to resist the particular burdens on women posed by capitalism in its neo-liberal phase as well as against the use of strident and overt appeals to patriarchal domination of women by right-wing authoritarians.

A review of that 1934 issue gives a sense of what that struggle for women’s liberation looked like when the Depression was still a reality. The combination of desperation for any kind of job, speed-up, dangerous work conditions and low pay was acute in the textile industry – one of the few centers for women’s jobs in industrial towns in New England and in the South. The result: spontaneous and organized protests. The violent suppression of a 1929 strike in Gastonia, North Carolina was a recent memory as was the death at the hands of armed vigilantes of worker/organizer and song writer Ella Mae Wiggins (her story has been memorialized by several novels, including Grace Lumpkin’s To Make my Daily Bread, which was excerpted in that issue of Working Woman). Worker discontent was to boil over a few months later in a national strike as 400,000 workers – mostly women – walked off the job in one of the largest national work stoppages in the U.S. to that point. This was one of the precipitating events of 1934 that was to culminate in mass unionism and the creation of the CIO. Unfortunately, though, the textile workers suffered a defeat that they were unable to overcome – the defeat in the South due to state-sanctioned and permitted extra-legal violence was to prove the Achilles heel for labor going forward. The violence of lynching – nominally done to “protect” women – fed into the culture that led to violence against the largely white women workers who sought to organize.

There was also an article about the miners strikes and the role of women in them. From the mid-1920s through the mid-1930s mining suffered from overproduction and layoffs. The United Mine Workers was divided and split while engaged in bloody strikes as sheriffs’ deputies patrolled mining towns as if an occupying army. A photo of Albino Cumerlato, a miner’s wife active in the Women’s Auxiliary who was killed during a strike in Southern Illinois, speaks to the war-zone atmosphere each time miners organized to assert their rights. And because those strikes pitted entire communities against surrounding authorities, miners’ women’s committees played a far more central role than in urban industry with a mainly male workforce. The article describes how women would rotate among themselves shared work in caring for children and cooking in the strike camps so that they could also rotate participation on picket lines and in meetings. The immediate battles described all ended in miner defeats (including the one in Harlan Country, Kentucky during which Florence Reece, a wife and daughter of coal miners, wrote Which Side are You On?) – but unlike textile workers, the years ahead would see a revival of union strength as the United Miners Workers (no longer at war with itself) regained lost ground and played a key role in the birth of the CIO.

As women were central to the life of mining communities, so women functioned as leaders in building community in struggle amongst the unemployed. Highlighted therefore in that issue was the demand of Unemployed Councils for passage of a bill for unemployment insurance, which had been a central demand of Communists and Socialists (but strongly opposed by old-line leaders of the AFL) since the Stock Market crash of 1929. Working Woman’s account focused on the black women from the South who took part in a conference in DC as part of that campaign to push a Congress that refused to budge. The legislation failed to pass but the agitation continued and contributed to the passage in 1935 of legislation that provided for the unemployed (through the Social Security Act and Federal Emergency Relief). The gains, even if not as far-reaching as initially proposed, made an enormous difference in people’s lives.

The articles about women in the unemployed movement and in the miners’ struggles emerged out of the reality that women were the primary care givers in most families. But International Woman’s Day was about the whole person – and so there was also an article about birth control and the effort to make it legal, alongside the demand for free medical care for women in labor. The need for women to decide how many and whether to have children was part and parcel to the demand for women to be treated with dignity and respect while giving birth, and to be able to do so safely and thus avoid all too common maternal deaths. The class arrogance of many doctors when treating working-class women was harshly criticized.

Yet there was another dimension of women’s rights highlighted– their full participation in the overall struggle for justice and socialism. The life and legacy of Louise Mitchell, one of the leaders of the Paris Commune in 1871, was commemorated as representative of the meaning of International Women’s Day past, as were the women who joined with her to fight alongside men on the barricades in its defense. Bringing that legacy to the then present, the women who joined men in the Socialist-led armed resistance in Austria to the imposition of a clerical fascism were honored. The victory of a form of clerical fascism closely aligned to Mussolini’s Italy (imposition of German fascism was still four years away) was one of the many global defeats of working people in the early 1930s and contributed to the mix of fear, anger and hope of the time. The dangers of war and of the need for peace – peace which the victory of German fascism put in jeopardy in a manner clear to many from the moment the Nazis came to power – was also written about in that issue. The articles reflected the anti-New Deal bias of Communists (and many Socialists) in the early years of FDR’s administration, but they also spoke to and reflected the radical upsurge and a broadening understanding of what could be possible that was to help propel the United States to the left in a decade when much of the rest of the world fell to reaction.

Taken as a whole what we see in the above was the legacy of International Socialist Women’s Congress which first called for the celebration of International Women’s Day rooted in the demand of equality – defined as respect for the rights of women as workers, and as full participants in the life of society; as the right of a woman to control her own body within and outside the family and the right to raise children with food on the table in a world without war; as the right for full participation in the struggle for freedom, for equality, for socialism. The language used and how these were understood were couched differently from today — many in the socialist and labor movements only gave lip service in their support while others did not hide their acceptance of women’s subordination – but the underlying struggle for equality in society and within the socialist movement never ceased. And, for its part, right-wing power never ceased to denounce socialism for the possibility it offered for equality.

Which gets us back to my Oma’s article. She and my Opa had come to the U.S. in the mid-1920s; a coal miner, he was blacklisted in Germany after the union suffered a bitter defeat in one of the struggles between capital and labor in a Weimar Republic that was always on the edge of civil war. He next worked the mines in Western Pennsylvania (and was blacklisted after another lost strike). They moved to New York where my Oma worked as a house cleaner – a common occupation for working-class German immigrants in those years. They had, however, every intention of returning to Germany where my mother had stayed, being raised by her grandparents. But then Hitler came to power, my Oma’s father and brothers were arrested. Thus, instead of their going home, my mother came here early in 1934. The article quoted must have been written shortly thereafter when the impossibility of a return became manifest – neither were to go back to Germany until we went as a family in 1958.

My Oma had become a Communist as a young person following the horrors of World War I and in the conditions of poverty and deprivation which hit mining communities especially hard in the years that immediately followed. In the course of that – or perhaps inherent to that – she also became a strong advocate for women’s rights. One of the substantial achievements of the Weimar Republic under Social Democratic influence was the dissemination of sex education in public schools and legalization of some forms of birth control. In that atmosphere, a campaign emerged to pass legislation to end the prohibition on abortion, which became a core element in the German Communist Party’s work among women, especially in the urban slums where too many faced the desperate choice of another hungry mouth to feed or a dangerous back alley procedure. One of the central planks of the Nazis during the years before they came to power was an assault on “bourgeois feminism,” an attack on Social Democratic educational reform and fear mongering about “godless Communism” and the “dangers” of free love and the abolition of the family that, it was claimed, Marxists were to impose on all women. Once they took power the fascists acted swiftly to roll back women’s rights, force them out of the workforce and ban birth control. As Margaret Atwood imagines for a possibly dystopian future in A Handmaid’s Tale, women in Nazi Germany were consigned to breed men for the war machine.

Something of my Oma’s bitterness at what transpired comes through in what she wrote – I can still hear her voice through all these years telling me as a child that Hitler wanted to limit women’s lives to “Kinder, Kirche, Kueche.” All this is not too far from Trump and Pence’s program today; the dual sides of how women are devalued as human beings reflect not just their twisted personalities, they speak to the core of their reactionary politics aimed as suppressing democratic rights for all by putting women in their “place” as sex object or mother.

And in the struggles that she and so many others were going though in the 1920s and ‘30s we see what too many immigrant women face today – fleeing from war and repression, children and parents separated from each other by poverty and violence, exploitation at work all the worse because of a lack of rights, the need for peace with justice so as to have a home rather than live with an ever-present sense of loss. Absent that, women migrants remain the most vulnerable to the dangers around them, yet are relied upon for their strength to hold families together in the face of a hostile society. We should celebrate International Women’s Day in that spirit of resistance and hope that helped transform U.S. society after 1934, that helped defeat fascism a decade later, as we confront the urgent need in our present to create a world in which such sacrifices are no longer necessary.

This piece first ran in the The Washington Socialist

…

Keys to 2020: Antarctica 69.3°, Bernie in Nevada 46%, Union Density 10.3%

By Max Elbaum

This article, written and posted on Organizing Upgrade before the South Carolina primary, has been updated to reflect Bernie Sanders’ loss in that state on Saturday, 29 Feb 2020

.

As we approach Super Tuesday, three numbers capture the stakes, the dynamics and the limits of the 2020 election.

The first is the temperature recorded in Antarctica on February 9: 69.3 degrees. This is the highest temperature ever recorded in the Antarctic Meteorological Region.

Antarctica has warmed by about five degrees Fahrenheit over the last 50 years; 87% of the glaciers on its western coast have retreated. The region just recorded its warmest January on record and this month an iceberg the size of Atlanta broke off from one its fastest-retreating glaciers.

This is as vivid as evidence can get that climate change is an accelerating global emergency.

HOAX OR TOP PRIORITY ISSUE?

This November the country’s response to this emergency is on the line. The Trump and anti-Trump camps are all but completely polarized on this issue.

Trump and his key advisers are climate change denialists. Numerous influential Republicans have called climate change a hoax. Trump has pulled the U.S. out of the Paris Agreements “leaving global climate diplomats to plot a way forward without the cooperation of the world’s largest economy.” The administration has steadily rolled back previously adopted environmental protections. The fossil fuel industry “has more clout than ever under Trump.” Trump’s base is on-board: less than 25% of Republicans say addressing climate change should be a top priority issue and less than half even think human actions are significantly responsible for global warming.

On the Democratic side, every remaining candidate except Michael Bloomberg supports some version of a Green New Deal, and even he gets a C+ rating from Greenpeace compared to Trump’s F. (Bernie gets an A+, Tom Steyer and Elizabeth Warren each get an A.) At least equally important, 78% of Democrats think fighting climate change should be a top policy priority in 2020. The semi-formal alliance between Democrats in Congress such as AOC and Senator Ed Markey with militant, often youth-led grassroots organizations has given this sentiment legislative shape and clout.

BIGGEST SOURCE OF SEA-LEVEL RISE

Climate change is hardly the only issue on which the Trump and anti-Trump camps are so sharply polarized. (Think race and racism, immigration, reproductive rights, the list could go on.) But it is one where the scientific consensus tells us we have already wasted too much time and decisive action in the next few years is crucial.

A Trump victory in 2020 means going even further backward: more rollback of environmental protections and more climate change denialism from the White House bully pulpit. Defeating Trump does not mean we can relax. But it would put in place an administration that is inclined (or in Bernie or Warren’s case, determined) to act. Any Democratic administration would be somewhere between susceptible to and enthusiastic about pressure from grassroots partisans of a Green New Deal on the scale the world requires. Further, if concrete steps forward are made, the 25% of GOPers who currently see a need to act on climate change could be peeled away from the Trump coalition.

The Antarctic glacier from which the Atlanta-sized iceberg has just broken off is the biggest single contributor to global sea-level rise of any glacier on earth. It has the capacity to raise global sea levels by four feet. But if sea levels rise even a few inches, low-lying communities worldwide are going to start flooding. November will decide if we do something about that or not.

IT COULD BE BERNIE!!

The second key-to-2020 number is 46.8%, the percentage of the vote won by Bernie Sanders in Nevada, more than double that of his closest rival. His victory, acknowledged the New York Times, was powered by “a multiracial coalition of immigrants, college students, Latina mothers, younger Black voters, white liberals and even some moderates who embraced his idea of radical change.” That victory catapulted Bernie into front-runner status, which he will maintain through Super Tuesday even in face of Biden’s big victory in South Carolina. Despite that setback Nate Silver’s 538 analysis still gives him a 28% chance of winning a majority of pledged delegates (more than double Biden’s 11% chance) and suggests he has a good chance of getting the nomination even if he only (only!) wins a substantial plurality. Most polls show Bernie doing significantly better than Biden in the pivotal contests two days from now, but this is a volatile year and anything can happen.

Bernie’s campaign still faces immense challenges. An avalanche of attacks is starting; it’s time for all of us to take a new or refresher course in how to deal with red baiting. (A set of Talking Points from Organizing Upgrade is coming soon.) It’s been a tough fight to get Bernie this far, but there is a kernel of truth in the conservative whine that Bernie “has been treated with kid gloves” by rival campaigns. They believed he couldn’t win and didn’t want to alienate his supporters by going after him with all rhetorical guns blazing. That period is over.

The Bernie camp must and will fight back. But this is not the time to go into a defensive crouch or demonize everyone who currently opposes or expresses doubts about Bernie winning the nomination. A large percentage of those who now hold those views (including elected officials as well as “ordinary” voters) are motivated mainly by fear of Donald Trump winning re-election and have been swayed by the endlessly propounded “conventional wisdom” that Bernie is “too radical” to do the job.

But Bernie being ahead opens a huge opportunity to persuade important new constituencies that the “conventional wisdom” is dead wrong. That is accomplished by insisting that we share their sense of urgency about beating Trump, and that we will work hard to build the broadest possible unity to make it happen.

Bernie himself is taking that tack. He knows that he cannot win the nomination, much less the presidency, if he only gets votes from people who agree with his full program. Rather, the route to victory requires both animating his base and convincing millions who disagree with him on many issues that their shared commitment to inclusive democracy is more important, and that he will defend their rights and interests far better than Donald Trump. And Bernie consistently stresses the need for broad anti-Trump unity while making the case that that he is the best candidate to beat Trump. Super Tuesday will be the next big test of whether this approach can widen his base.

The underlying strategic point here goes beyond this election. U.S. society is huge and complex; millions see all kinds of things in different ways and are rarely models of political consistency. The radical left cannot set the national agenda if it is supported only by those who back our views 100%. We need to become the leadership of a coalition that goes beyond our own ranks. One of the most exciting things about the way this primary season is unfolding is that it may give us a chance to learn how to do this on a scale few imagined possible even a year ago.

LOWEST UNION DENSITY IN 80 YEARS

We not only have a lot to learn, it is urgent that we build our muscle. The most telling single indicator of where we stand relative to the far right and establishment “center-left” in terms of on-the-ground strength is that trade union density today stands at 10.3%. This is less than one third of labor’s strength in the late 1940s/early 50s and the lowest figure since the early 1930s.

There is no comparable single number that indicates for other battlefronts and forms of organization how far we have to go. But even a cursory look at the landscape shows that resurgent movements for racial justice still lack the deep roots and organizational breadth of the 1960s upsurge; the peace movement and degree of internationalism in progressive circles generally come nowhere matching today’s threats of war and aggression; and coordination across different movement “silos” is only slowly breaking down. Even concerning electoral action, where the gains by progressive are most visible, we still lack a unified vehicle which all or even most progressives use to coordinate our efforts.

JANUARY 2021 AND AFTER

No matter who wins the White House, the impact of these weaknesses will come crashing in on us within hours of the inauguration. That’s true even in our “best case scenario”: Bernie (or what now seems like a very long shot, Warren) wins the White House and the Democrats regain control of the Senate and expand their majority in the House. There still will not be a majority for a far-reaching progressive program in Congress – and conservatives retain control of the Supreme Court. That means there is no way to implement deep structural reforms (much less the more radical changes sought by the far left) via the machinery of government alone.

What does and doesn’t get done will largely be determined by pressure from the “outside.” The out-for-vengeance Trumpist right will deploy its billions of dollars, its well-oiled disinformation machine, its army of lobbyists, and its phalanx of haters to block every attempted step forward. The wing of the elite that opposed Trump will mobilize its financial and media resources and its experience in “working the system” to keep the most far-reaching initiatives pushed by the left within what they consider safe bounds.

Coming off a victory over Trump and the leaps forward in numbers and sophistication social justice groups have made since 2016, our side will have lots of people power to throw into the fray. But we are likely to get a sharp reminder of the difference between winning an election and having a sufficiently organized and consolidated base, level of institutional strength and unity across sectoral divides to turn our agenda into facts on the ground.

Going all-out in the 2020 electoral fight, and especially focusing our efforts on key sections of the multiracial working class, expands our connections with millions who are discontent and open to hearing about a different path. It gives us a chance to bring large numbers of new people into our political orbit and expand the ranks of progressive and left organizations.

But we are in a long-term fight for political power and the results on election day will be only one test, if a decisive one, of how much we have accomplished. Another will come in the months and years immediately following November 2020. Can we double and then triple union density and make comparable gains in building organizations focused on racial justice, gender justice, environmental justice and peace. If ever there was a “both/and” moment, this is it. Only if we expand our muscle on the ground by orders of magnitude in addition to building a powerful electoral machine can we gain the power we need to make the changes we want.

For starters, keeping Antarctica from melting away.

…

The January 2020 Regional Elections in Emilia Romagna and the Movimento delle Sardine: Lessons for the US?

By Nicola Benvenuti

The victory of Stefano Bonaccini, Presidential candidate for the Partito Democratico (PD), in the regional elections in Emilia Romagna on January 26 has been a breath of fresh air for the PD. Indeed, it was preceded by defeats for the PD in other regions, most recently in Umbria. To also lose in Emilia Romagna would have been politically disastrous because since the end of the war the region was governed by the Partito Communista Italiano (PCI) and has remained to this day the principal electoral bastion of the left.

The right, led by Matteo Salvini, aimed to strike at the heart of the PD, the mainstay of the Yellow-Red government (Movimiento Cinque Stelle+ PD) born out of the crisis provoked by Matteo Salvini in August 2019. Indeed the M5S, after becoming the leading Italian Party in the last elections, in the months that followed has suffered a steady dwindling of approval, and lost every semblance of unity between its many factions, to the point that three days before the elections in Emilia e Romagna the leader of the M5S, Luigi Di Maio, was relieved of his post as General Coordinator.

But the victory of the PD is only partial. The same day the right won in Calabria, stripping it from the PD, even though the significance of that vote is due less to political instability and more to the fact that during the previous elections the region was a stronghold for the M5S (43.3% in 2018) who have now garnered only a paltry 6.2%.

In addition to the wavering light of the Party’s star and the weakness of its political structure (the delusion that regional structure could be replaced by networks), the M5S has been outplayed by the Lega of Matteo Salvini, which, adopting behaviors more common to a movement than a political party (a continuous presence in the streets, the use of a simplified, demagogic and aggressive political language in lieu of a discussion of its programs, the cult of “The Boss” – Salvini is called “Il comandante”) and inspired by Trump (with wide appeal to social media), undermined the “trasversalismo” (that is, the claim of being neither of the left nor of the right) of the M5S by inciting conflict between the Lega and the M5S, to the point that it doubled, in the polls, the support it gained in the previous election. Factoring in the withering away of the electorate of the now ancient Berlusconi’s Forza Italia, the Lega has cast itself as Italy’s prime party: hence its attempt to undermine the legitimacy of the government and the calls for early elections.

The PD, Having fallen close to 18% of the valid votes in the elections of 2018 and suffering a profound identity crisis, after the exit of ex Premier Matteo Renzi (who founded his own personal party, Italia Viva) it is creating a role for itself in the Yellow/Red government, presenting itself as the trustworthy, unitary government party. But when it presented itself during the elections in Emilia Romagna, it presented itself as a party defeated in Umbria (another once red region), of uncertain identity, with abandoned territories, confused leading groups, and incapable of sending clear signals to the country. But…

But in December 4 young people engaged in social media, of the left but unrepresentative of any party, invited the citizens of Bologna to a march in Piazza Maggiore, without symbols or party flags, to protest the violent and simplifying language of Salvini and the right, inviting the citizens to get personally involved (given the inability of the political parties) and defend the civil gains and welfare of the region: their only symbol a sardine, a fish neither aggressive nor predatory that doesn’t shout but moves in unison without the need of leaders. The march was an enormous success and since then the movement has spread like wild fire, accompanying every electoral appointment of Salvini with piazzas crowded with people of all ages as the national anthem and “Bella ciao” sound. The example was such that movements inspired by the “Sardines” have sprung up all over Italy, and in Rome they filled Piazza San Giovanni In Laterano in which a few weeks prior the united right made a mighty display of offering itself as candidate for the government of Italy: The sardines have taken the Piazzas from Salvini!

Thanks to the “Sardines” the regrouping of the center left around the PD has now become possible and the regional elections have seen a doubling in voter turnout, 67% as opposed to 30.89% previously, and in favor of the PD and local candidates allied with PD candidates.

Certainly Salvini’s unending propaganda, made up of violent simplifications, of hours of selfies with fans, handshakes and hugs, were starting to unsettle parts of the moderate right, while there grew in associated parties an intolerance for the solitary direction of the “Commandante.”

.

From the Editor’s Desk:

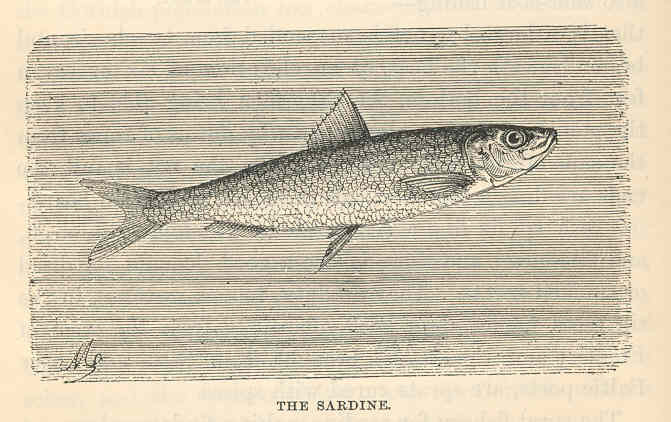

The sardine is a non-predatory and non-aggressive fish whose schools have no leaders.

The Italian “Movimento delle Sardine” has given new life to the left and resulted in increased turnout at Italian polls, and for now has enabled the Partito Democratico to hold on to power in Emilia Romagna, one of the historic “Red” regions of Italy. The left has been under extreme duress at the hands of the Trumpian demagogue, Mateo Salvini who employs many of Trump’s tactics of hate mongering, online insults and mass rallies of his supporters in key electoral battleground states. In fact Salvini appeared at a MAGA rally in New Jersey during the 2016 campaign to rally Italian American voters to Trump.

Wherever Salvini goes or holds his rallies, the “Sardines” counter with non-partisan, endorsing no candidate, rallies denouncing his hate, xenophobia and politics of fear.