60 Percent – a relic of white supremacy, a key part of America’s structural racism

By Stewart Acuff

Forget for just a moment our movement dreams of justice, democracy, equality and the rest of our agenda.

Think for this moment only about survival of our human species.

Existential threats of human extinction or deadly mayhem and random gun violence now require the literal death of the filibuster.

We know we can’t pass meaningful climate legislation, gun regulation, voting rights and workers’ rights if we must exceed the random, ridiculous, undemocratic barrier of 60 % in the US Senate.

The filibuster is a relic of white supremacy, a key part of America’s structural racism.

In fact, South Carolina Dixiecrat Senator Strom Thurmond filibustered by himself for more than 24 hours against a civil rights bill in 1957. Later, he bragged about dehydrating himself for three days so he could avoid urinating.

Seven years later, southern racist senators filibustered against the system busting, change making Civil Rights Act of 1964 for 60 working days.

Because of the filibuster we can’t pass HR 1, the omnibus voting rights bill passed in the House while GOP state legislatures are jack hammering 253 Jim Crow voter suppression bills. One bill already enacted in Georgia criminalizes giving water to registered voters standing in long lines to vote. Republicans have cut access to the ballot by limiting mail voting, absentee voting, Sunday voting, early voting, and enacting stringent voter ID laws and regulations.

HR 1 would establish a national baseline of fair and equal voting procedures to give all Americans equal access to the ballot and to democracy.

This non-Constitutional Senate rule prevents us from saving our Earth, our world, our work and our lives.

The agenda of the Democratic Left requires passage of legislation to make fundamental change. The agenda of the Authoritarian Right only requires obstruction of legislation.

The Right has the courts. If we don’t end the filibuster and acquaint the Senate with majority rule, the Right can rule with a minority of voters.

Time to kill this tool of American racism and white supremacy.

…

Strike Hard, Have Fun, Make History – Amazon general strike in Italy – March 22, 2021

By Peter Olney

On Monday, March 22 workers throughout the Amazon logistics system went on a one-day strike in Italy. This is the first time in the world that there has been a nationwide/system wide strike against Amazon.

The Stansbury Forum interviewed Leopoldo Tartaglia from the SPI CGIL – Sindacato Pensionati Italiani – Italian Pensioners Union CGIL, about the strike, Amazon operations in Italy, and the particular features of the Italian labor movement.

Stansbury Forum (SF): Thanks Leo for helping us understand this historic national strike against Amazon. Can you please give us the basic details about the strike?

Leopoldo Tartaglia (LT): It can be said with certainty that the strike was successful, especially among the drivers where participation was around 75%, with peaks of up to 90%. This probably delayed a substantial chunk of deliveries on March 22, but of course it is impossible to know how many customers were unable to receive packages from Amazon. There are around 19,000 Amazon drivers in all of Italy. For the 9000 direct employees in the warehouses (fulfillment centers) and the delivery stations participation was around 70-75% on average nationally, with peaks in the northern sites, and a little lower in the south of Italy. Among the 9000 temporary agency warehouse workers, participation in the strike was 25-30%, but that level was considered a positive by the trade unions given the total blackmail of these workers because their contracts are only temporary, and they have the minimum hope of having their employment renewed.

Even in the media, the strike was given great prominence. Newspapers, television and radio that rarely give coverage to workers’ struggles, were all over the strike and reported on the conditions of uber-exploitation and of excessive workloads both in warehouses and for the drivers. Some center-left parliamentary deputies have made demands on Amazon, and the Minister of Labor (Andrea Orlando del Democratic Party) has made it known that he intends to summon for talks Amazon Italia and Assoespressi, the employers’ association that groups together the delivery companies that work for Amazon. It is too early to see what other effects the strike will have. The three national trade unions, CGIL, Confederazione Italiana Sindicati Lavoratori (CISL) and Unione Italiana del Lavoro (UIL) aim to resume negotiations both with Amazon and Assoespressi to arrive at supplementary contracts that regulate schedules, shifts, work positions, stabilization of temporary workers. In recent months, meetings had been held with both Amazon and with Assoexpressi, but no agreements were reached, and the bosses were unwilling to continue negotiations.

SF: How long has Amazon been in Italy? How many facilities are there? What is the total employment – warehouse workers and drivers (independent contractors?).

LT: Amazon arrived in Italy in 2010 and has since invested over $5.8 Billion euros in building out its operations. There are now 8 fulfillment centers in Italy with two new centers scheduled to be opened in 2021 in Novarra and Modena. There are 2 sortation centers and 26 delivery stations for the last “kilometer”! Amazon employs 9,500 warehouse permanent employees, 2,600 of whom were new hires in 2021. Within the warehouse however there are temporary workers from temp agencies. Their numbers vary but by national labor agreements their total should not exceeed 15-20% of permanent employees. Union estimates are that there are tens of thousands of Amazon courier drivers throughout Italy. They are employed by independent contractors or are IC’s themselves.

SF: Are these workers covered by national agreements? What kind of agreements? Is it true that while these workers may be covered by a national agreement, they do not have to belong to a union?

LT: Amazon’s direct employees are covered by the national collective bargaining agreement of the logistics sector, signed by Fit Cisl, Filt Cgil and Uiltrasporti[1]. For some departments or types of work they can be covered by the national collective trade-services labor contract, signed by Filcams Cgil, Fisascat Cisl, Uiltucs.[2] Temporary workers of temporary agencies are covered by the national collective agreement of temporary employment agencies signed by Nidil Cgil[3] and by the two similar trade federations of Cisl and Uil. These contracts provide that the salary and fundamental rights of the temporary worker “on mission or same task” are equal to those of employees of the company where they are sent to work (the national collective bargaining agreement applied to Amazon, in this case).

For drivers, the situation is complicated: if they work for companies or cooperatives they are covered by the respective national collective agreements for the sector (probably most of them by that of Logistics); if they are “autonomous” they have no national collective agreement and their relationship with Amazon is purely commercial in nature.

In Italy, national collective bargaining agreements apply to all workers in the sector, regardless of whether they are members of the trade union or not. Normally, national collective labor agreements are signed by the trade federations of CGIL, CISL, UIL, which are the most representative organizations in terms of members and votes when electing Rappresentanze Sindicali Unitarie (United Trade Union Councils) in the individual workplace. In recent years, problems have arisen with what we refer to as “pirate contracts”, that is substandard contracts signed by employer organizations and minority unions but which, from a legal point of view, have the same value as those signed by the most representative unions, at least until someone appeals to the labor judge and the judge (sometimes) orders the company that has followed the “Pirate contract” to apply the one signed by CGIL, CISL, UIL.

SF: If they are already covered by national agreements, why are the workers striking? What are the demands of the unions in the strike? Was the strike successful? What are the next steps?

LT: There is a broad range of demands that the Unions are making, both for the direct employees and for the subcontractors. In fact, in recent years, at the local level, different agreements have been reached mainly to ameliorate the working conditions inside single warehouses and, in many cases, also to improve the salaries linked to local productivity, based on the minimums established by the national collective agreements.

Amazon has always refused to discuss with Unions the conditions of the subcontractors, mainly drivers, who are an essential part of the work force and of Amazon’s business model.

So, the strike was mainly motivated to force the company to act to improve the general working conditions of the subcontractors.

But the whole workforce’s conditions are at the core of the struggle. Here are some of their demands:

Reduction of fines penalties (damaged vehicles etc.) and excessive working hours

Reduction of the working time for drivers

Bargaining on the organization of internal shifts and work rotation

Stable jobs for the fixed term and temporary workers

Full respect by the company for safety and health provisions, particularly considering the present pandemic.

SF: How do multiple unions in one facility work together or compete with each other? How does that impact bargaining?

LT: This issue exists on two levels: One is the relations among the single federations/confederations which usually are both of competition (to get new members, to win workers votes for the RSU’s, and to convince workers to choose the services offered by their confederation.) and cooperation, mainly through the RSU – Workplace Councils, for collective bargaining. Obviously, the bargaining is damaged by the lack of unity among Unions.

The second level is about the relations among federations who unionize different workers in the same facility (in the case of Amazon workers covered by national collective agreement of Logistics and those covered by the national collective agreement for temporary agencies). In this case, often, the different group of Unions, unfortunately, are working separately, despite the fact that everyone says that it is necessary to work together.

The March 22 strike was called by the three national federations: Cgil, Cisl and Uil. Both Amazon’s direct employees and the subcontractors – particularly drivers organized as self-employed, or by cooperatives, or both, were involved.

Also the strike was called for the temporary agency workers by the Cgil Nidil Federation (atypical workers), and the same federations of Cisl and Uil.

SF: What kind of support from US Amazon workers would be helpful?

LT: Any form of solidarity is welcome. I think in the medium term, through the Global Unions, it will be necessary to build international coordination of different Amazon’s national and local Unions all over the world.

SF: Are Italian Amazon workers talking about the union vote in Bessemer, Alabama?

LT: Frankly speaking I don’t think so. Unfortunately there is big fragmentation of the working class, and it is increased by the difficulties of information and language. I don’t know how many Italian union leaders are even aware of the Bessemer situation.

…

[1] Fit CISL – Federazione Italiana Trasporti part of Confederazione Italiana Sindacati Lavoratori – One of Italy’s 3 national federations

Filt CGIL – Federazione Italiana Lavoratori Trasporti part of CGIL – Confederazione Generale Italiana dei Lavoratori – Italy’s largest national labor federation

Uiltrasporti – Unione Italiana dei Lavoratori TRasporti part of UIL – Unione Italiana del Lavoro – Italy’s smallest national federation

[2] Filcams – Part of CGIL –Federazione Italiana Lavoratori Commercio Alberghi Mense e Servizi

Fisascat part of CISL – Federazione Italiana Sindicati Addetti Servizi Commericali Affini Turismo

Uiltucs – Part of the ZUIL – Unione Italiana Lavoratori Turismo Commercio Servizi

[3] Nidil –CGIL – Nuove Identita’ di Lavoro – A new sub federation founded in 1998 to represent atypical workers, non-traditional workers. Part of CGIL

Selena and her Fans También Lloran: The Descriptive Power of Melodrama in “Selena: The Series”

By María Luisa Ruiz, Ph.D.

In the third episode of Selena: The Series the titular character, rising Tejano singing star Selena, sits between her two siblings in backseat of her family’s sedan as they travel to Mexico for a concert. In order to pass the time, Selena recounts the tragic love story between two of her father’s relatives. She retells the story in Spanish, with exaggerated movements and impassioned (invented) dialogue. In this scene, a number of narrative threads come together: Selena, born and raised in Corpus Christi, needs to practice Spanish for her growing Spanish-speaking fans that live across the border so, prior to the trip, she ‘teaches’ herself by watching Spanish-language telenovelas (she resorts to this because, her constantly exasperated father Abraham Quintanilla, denies her request that he purchase Berlitz, the learn as you go language program. She can’t really practice her Spanish another way, since he had earlier pulled her out of school because it interfered with her burgeoning singing career). As she sits at home, waiting for her next gig, she watches telenovelas. She is captivated by the exaggerated acting, dramatic storylines and impassioned tones with which the characters speak in the telenovelas.

Abraham, clearly upset by her dramatic retelling of his relatives love story, commands her to stop. In response to her father admonishing her for her apparent disrespect, Selena responds “Come on, it [the story] does kinda sound like a telenovela”. Not a man to keep quiet, the father pontificates, “except this is not a telenovela. These are real people. Real things happen to real people and they persevere. If this story doesn’t happen, you are never born.”

“The melodramatic narrative mode is not confined to novels and the realm of fiction but rather performs to make complex realities and news events into logical and consumable stories.”

His admonition quiets everyone in the car and Selena proffers a quiet apology, the moment of levity gone. This scene seems to be a moment of unintended metatext: at the same time, he admonishes Selena, he is also reminding the audience to not take the story lightly. Instead of looking at the Selena’s story as one of joy, triumph and yes, ultimately tragedy, we are meant to connect with the morally upright family and the conservative values they embody necessary to cultivate her talent and protect her rise to stardom. In order to do this, I argue, the series relies on traditional standards of melodrama to retell the story of Selena.

Reading Selena within the melodramatic mode helps us understand how her story and person continue to fascinate new generations of fans 20 years after her tragic death. For many, melodrama, as Selena’s scene suggests, dwell on situations of intense pathos, scenarios of emotional excess nearly unmatched in any other form of narrative. Melodrama, like many cultural forms associated with female audiences – intense emotion and high sentiment – is simultaneously omnipresent in television and yet continuously undervalued. I prefer the descriptive power of melodrama as a type, a narrative style, and a cultural mode that provides a narrative structure that makes a strange story feel familiar and, as Matthew Bush suggests facilitates the understanding of artistic and actual events (2014, 15). The melodramatic narrative mode is not confined to novels and the realm of fiction but rather performs to make complex realities and news events into logical and consumable stories. And what better way than melodramatic conventions to make sense of the senseless death of a charismatic singer whose life ended at such a young age?

Since her tragic death, Selena’s life, music and legacy continues to fascinate. The 1997 film “Selena”, directed by Gregory Nava, sanctioned by her family helped construct a version of her life story. “Corpus: A Home Movie for Selena” (1998) by Lourdes Portillo presents a more introspective study of the mass adulation and explosive posthumous recognition of the singer. Thanks to social media, Nava’s film continues to hold an important place in popular culture among many in the Latinx community; iconic lines from the film like “Anything for Selenas” continue to be used in memes and gifs (indeed, that is the name of the recent podcast that traces the influence Selena has for the narrator and creator, María García). Her now iconic sparkly purple jumpsuit has been recreated by notable social media influencers like Kim Kardashian and actress America Ferrera. Beyoncé, fellow Texan and cultural icon in her own right, credits Selena as one of her artistic inspirations. Careful curation of Selena’s image by her family (her father, Abraham Quintanilla, is notoriously litigious and intensely protective of legacy) has helped expand her influence to more mainstream audiences. This includes the fan-driven MAC makeup line that was so successful that a second line was launched in 2020.

“Selena: The Series”, then, is another entry in the ever-growing corpus of narratives that shape her legacy. Totaling eight half hour long episodes, the series follows Selena’s rise to stardom. Despite less than positive reviews and critiques of the way that the main character is portrayed, a second season is set to air in May 2021. The episodes are set up as a rags-to-riches tale with Selena as the series’ Cinderella-like heroine. However, the noble, rigidly ethical, scrappy and above all, tightly knit family (ancillary characters and other family members appear abruptly without any real introduction) is at the center of the narrative. The nuclear family unit is headed and ruled over by the ambitious and controlling pater familias; the mother, the few times we see her, embodies a traditional maternal figure.

“Selena is a role model for young girls who also want to rebel but do so harmlessly, and within the confines of family honor and respect.”

While her father is the moral and authoritative center (a characteristic of melodrama), she is the sweet, generous, empathetic young girl who obediently follows the rules (any attempt at rebellion is just that, a benign attempt). Her seeming moments of rebellion are sartorial: while the show itself isn’t compelling narratively, the ever-changing outfits and hairstyles that mark the passage of time keep one slightly engaged. Selena appears to be much more concerned with fashion, magazines and of course telenovela-style romance (she practices kissing on a magazine cover) than the daily grind needed to gain fame and fortune. This innocence and talent, the show seems to suggest, must be protected and cultivated in a morally upright manner by a strong male authority figure whose strong voice and harsh realism is tempered by his wife’s gentle touch and maternal presence.

Melodrama embodies a worldview that the universe is inherently moral, and the characters within the melodrama are archetypes that exemplify specific and readily identifiable moral forces. Selena is a role model for young girls who also want to rebel but do so harmlessly, and within the confines of family honor and respect. For example, in a later episode, we are introduced to a secondary character, a teenage girl named Gabriela who works in her family’s restaurant. Gabriela badly wants to go to a Selena concert, but her mother tells her no because she is needed at the restaurant. Gabriela ends up sneaking out but does so with the tacit approval of her more indulgent father. Her small act of defiance seems to speak to Selena’s ability to inspire young girls to seek their dreams, and more importantly, to test the boundaries of, but not challenge family hierarchy.

The father’s words on the way to the concert in Mexico seem to cast a shadow over the series. In much the same way the father tried to enclose Selena’s effervescence and charisma, the series’ narrative tries to contain audience reactions. Using Abraham Quintanilla’s authoritative and paternalistic voice, “Selena: The Series”, seems to make determined and deliberate overtures toward fans, attempting simultaneously to acknowledge and manipulate a complex affective relationship. The audience is Selena, sitting in the back seat of a stuffy car, wanting to break out but are told to contain and stifle their emotions in order to respect her life. The audience is to treat the narrative and the character reverently; the show is an effort to control the founding myth of Selena, her family and her legacy.

…

A Woman’s Work Chronicles the Fight Fight Fight for Decent Treatment by NFL Cheerleaders

By Molly Martin

I admit I was prejudiced. I was one of those feminists who thought cheerleaders were the antithesis of feminism, sucking up to powerful men and athletes, embodying or seeking to embody the male ideal of woman.

But then I saw the PBS film A Woman’s Work (unfortunately the film is no longer on PBS), about the struggle of the NFL cheerleaders for better wages and working conditions. Now I think some cheerleaders are feminist heroes.

The film documents their years-long campaign against wage theft by their employer, the National Football League. The NFL and its 32 franchises are worth $80 billion and yet, rather than do the right thing and pay their workers a decent wage, they round up their corporate lawyers and fight to keep women down. The industry, run by rich conservative old, white men, still views itself as untouchable. Now the cheerleaders are on the front line in the feminist struggle against male chauvinism, male privilege and toxic masculinity.

I’m a retired electrician who has fought for the last half-century to insure women’s entry to the skilled trades. The construction industry is the other side of the gendered employment coin. We were kept out of lucrative union construction jobs because of our gender. The bosses said we were not strong enough to do the work and they’re still saying it, even though we’ve been doing the work for decades. Of course, just because the job is physically difficult does not mean a worker makes better pay. Quite the contrary. Plenty of women (and men) work at hard jobs for low pay. Union construction workers make good money because of union contracts.

Women wanted to work in construction for many reasons: We wanted to build something valuable, to learn a craft and take pride in it. Many of us chafed at being required to wear dresses, pantyhose and makeup to work. But the big reason was money. Men working in “men’s” jobs make way more money than women working in “women’s” jobs.

Watching this film I felt an immediate sisterhood with the cheerleaders. Their plight brought up questions for me: What do they, working in a “woman’s job” have in common with us women who work in the construction trades? The film asks “What is women’s work? What is men’s work?” Cheerleading was once the domain of men, that is until team owners realized sexy women shaking their booties could make money for them.

I didn’t know how bad it has been for cheerleaders. Maybe no one did. They were traditionally paid less than minimum wage and not paid for much of the work they did. Some teams paid them nothing at all. They were required to practice—wage free—for nine months before the season. And they were fined when late to practice. They were constantly scrutinized for body fat and rated on the size of body parts.

The film introduces us to three women from different NFL teams who chose to fight the NFL’s sexism. Lacy’s story is compelling. The product of a poor family in small town Alabama, she had always wanted to be a dancer and she began winning dance contests early on. The first to file a lawsuit, in 2014, she worked for the Oakland Raiders. A cheerleader in high school and college, Lacy was used to being paid for her work; “Louisiana Tech compensated us well,” she says. So it was a shock to find out the Raiders and the NFL didn’t value the cheerleaders even enough to pay minimum wage. The women didn’t get paid till the end of the year, and then not at all for the nine months of required practice sessions. Hair, nails, tan and required travel were out-of-pocket expenses. Waiting for her first paycheck to come, Lacy says she didn’t know all this.

Lacy retained the San Francisco law firm Levy Vinick Burrell Hyams, known for taking on major employment discrimination cases. I was pleased that the film includes interviews with the lawyers, all women. The firm’s symbol is Rosie the Riveter, and their motto is “Who would Rosie hire?” I was delighted when the camera zoomed in on a picture of attorney Mary Dunlap, a civil rights hero in the San Francisco Bay Area. A well-known feminist and gay activist who died in 2003 at 54, Mary was a founder of Equal Rights Advocates, a law firm that we tradeswomen have worked with since the 1970s. Without our dedicated lawyers we could never have succeeded in integrating the construction trades. As with the cheerleaders, class action lawsuits were the basis of our ongoing struggle.

“cheerleaders for the Saints can’t have players follow them on social media, must have private social media accounts and are required to leave parties or restaurants if players are there. The company says the rules are in place to prevent cheerleaders from being preyed on by players.”

Also profiled is Maria who, along with five other cheerleaders, filed suit against the Buffalo Bills, a team that expected its cheerleading squad, the Buffalo Jills, to work for free. In response the NFL used tactics that employers typically use to fight unions. The Buffalo Bills team simply abolished its cheer squad. Then they blamed the women who filed the suit, using the divide and conquer tactic and bullying the others to opt out of the suit, which has still not been resolved.

Bailey Davis is the third cheerleader profiled in the film. She filed an EEOC complaint against the New Orleans Saints. Davis was one of the Saintsations, the Saints’ cheerleading squad. That is, until she posted a photo of herself in a one-piece lace bodysuit on her private Instagram account. The Saints fired the 22-year-old in 2018 for violating a code of conduct that prohibits cheerleaders from appearing nude, seminude or in lingerie. It wasn’t the only strict rule that Davis and her former colleagues had to follow—cheerleaders for the Saints can’t have players follow them on social media, must have private social media accounts and are required to leave parties or restaurants if players are there. The company says the rules are in place to prevent cheerleaders from being preyed on by players.

“The players have the freedom to post whatever they want to on social media,” Davis told the press. “They can promote themselves, but we can’t post anything on our social media about being a Saintsation. We can’t have it in our profile picture, we can’t use our last name for media, we can’t promote ourselves, but the players don’t have the same restrictions.”

The women who filed suit against the NFL were attacked mercilessly. “I just kept telling myself I’m doing the right thing,” says Lacy.

At the same time as it keeps a tight reign on the cheerleaders’ behavior, the NFL protects players charged with domestic violence. There’s a connection here. “Wage theft, sexual harassment and domestic violence are all about power,” say the lawyers.

Scenes later in the film show these women at home taking care of kids and husbands with a not-so-subtle message that all women’s work is undervalued. Here these women work for free and there is no time off.

Another issue, the sexual harassment and pimping of cheerleaders is only hinted at in the film, which focuses on labor issues like wages and working conditions. In 2018 Washington Redskins cheerleaders complained of being pimped out to male donors. “I don’t think they viewed us as people,” said one.

Football reeks of toxic masculinity. And having a posse of sexy females ready to do your bidding and totally under your control is just part of the deal. Women are seen by these men as sexual objects. Decades ago the Dallas Cowboys led the way in selling sex on the sidelines while paying the cheerleaders next to nothing. “It was a business,” said members of the squad. “And we were the merchandise.”

In the construction trades, after decades of fighting for equal treatment, our efforts are paying off. It took years to get our unions on board, but now they are partnering with women to improve working conditions. Because of our advances, when the #Metoo movement erupted I was shocked—not that sexual harassment existed in Hollywood and elsewhere, but that it was so widespread and institutionalized. The world of construction is changing, if slowly, and we are ahead of some industries.

The world of cheerleading is changing too. It’s now seen as a competitive sport that incorporates gymnastics with athletic dance. Millions of people watch and participate in worldwide competitions. The NFL needs to get with the program.

Lacy won her lawsuit, after four years of fighting, but many more lawsuits are in process. Ten teams have been sued so far. The NFL has met its match in cheerleaders. Lacy, who had not considered herself a feminist, now says, “I realize feminism is everything I’m fighting for—equal rights, equal pay, equal treatment.”

The film is available to rent/buy through links HERE.

…

Published in Work History News, the newsletter of the New York Labor History Association.

Time to Defy History, Win in 2022

By Peter Olney and Rand Wilson

There is no rest for the weary. The 2020 election triumph in the battleground states and the historic victory in the Georgia Senate races is fast becoming a fleeting memory. With the disappointing, but expected, results of the Senate impeachment trial, the public focus shifts to the Biden agenda for the pandemic and economic justice. If politics is the “art of the possible,” this is a tough moment for the dreams and aspirations of so many of us.

Lulled by media incantations about an expected Blue Wave, many progressives yearned for the legislative possibility that with a strong push from the left, the Biden administration would champion and pass the Green New Deal (GND), Medicare for All (M4A) and the Protect Our Right to Organize Act (PRO Act). Instead, all three initiatives are substantially dead on arrival in this Congress. Even if Biden championed these landmark bills, there are not the votes in Congress to send them to his desk for signature. The PRO Act, which he has pledged to support, passed the House in 2019 with 218 votes including two Republicans. These were “free” or easy votes because corporate lobbyists knew that the law had no chance to pass in the Senate or to be signed by #45. Neither the GND nor M4A had enough support in the last Congress to even get to a vote in the House.

So we should continue celebrating our efforts in battleground states, and we should salute the grassroots efforts (especially by people of color) in Georgia. But it’s not too soon to start planning for the 2022 Congressional midterm elections. Should Peter be renting a beachside cottage in Orange County to work on flipping two House seats that Democrats won in 2018 but lost to Republicans in 2020? Should Rand be plotting to help defend a potentially endangered New Hampshire House seat?

DEFY HISTORY?

The incumbent President’s party historically takes a shellacking in the midterms. One exception was in 1934 when FDR’s Democratic Party triumphed with Congressional gains two years into his first term, which enabled passage of the most progressive New Deal legislation.

However, the 2020 election results in both the House and Senate do not bode well – in fact, increasing the Democrats’ margin looks near impossible! What could the Biden administration and the Congress, barely controlled by Democrats, do now to give us any hope of defying history?

Better not leave it to the liberals! We’ve got to go all out to pressure Biden and Congress to give us enough good stuff to fire up working-class families to once again believe in “change” and restore “hope” for what could be achieved with bigger margins in the House and Senate. Some near-term achievable goals are:

– Fully-funded stimulus package (through budget reconciliation)

– Cancellation of $50,000 in student loans (executive order)

– $1.4 trillion funding for infrastructure (bipartisan support likely)

– $15 minimum wage on a fast track

GOALS WE CAN MEET

The $1.9 trillion stimulus has already passed the House and the Senate. Democrats can proudly run on the passage of this package – even if they fail to raise the Federal minimum wage to $15. Can Republicans afford to campaign against the $1,400 in direct payment per adult and child in a family? $350 billion in aid to state and local governments? $300 per week to enhance unemployment benefits? A child tax credit? $50 billion for vaccine distribution and $200 billion for schools?

Many believe that Biden has the executive authority to unilaterally forgive student debt under the Higher Education Act and have urged him to forgive up to $50,000. Biden has resisted calls for executive action and has claimed that he does not have authority to forgive that amount without Congressional action. He has, however, put a pause on repayment through September 30, 2021. Hopefully another delay after that could extend relief to those burdened by student debt.

On his third day in office in 2017, Trump invited the North American Building Trades Unions (NABTU) to the White House. Afterwards, they showered him with praise because they expected he would spend on infrastructure and put thousands of union construction workers to work. Instead they got no infrastructure, and a potentially crippling attack on their apprenticeship programs and their hold on Davis-Bacon prevailing wage construction work.

In contrast, Biden has nominated Boston Mayor Marty Walsh as Secretary of Labor. Walsh comes out of the Laborers Union and was head of the Boston Building Trades while serving as a state representative in Massachusetts. He has fought for affirmative action in hiring and drivers’ licenses for undocumented immigrants. Walsh strongly appeals to the white working class. If Biden makes good on his $1.4 trillion infrastructure proposal, there is the potential to mobilize hundreds of building trades unionists as “ballot brigadiers” in the 2022 midterms.

The $15 minimum wage is a no-brainer and it polls well across all constituencies. Despite losing the vote on Bernie Sanders’ amendment to add the $15 minimum to the $1.9 trillion coronavirus relief package (with eight Democrats voting against it), hopefully movement pressure will continue to build, and the raise will come to the floor again. Win or lose, politicians from either party who opposed it should face serious consequences in the midterms.

2022 IS CLOSER THAN YOU THINK

November 2022 is less than two years away. In some districts there will be primary challenges from the left. In some open primary districts, as in California, we need to avoid primary challenges that end up with two Republicans on the ballot. Many of the auxiliary GOTV and coalition groups like Swing Left and Seed the Vote are already thinking this way.

But what about labor? Members of IBEW Local 1245 – the giant PGE utility workers local in California and Nevada – were knocking on doors in battleground states. UNITE HERE members mobilizing in several swing states became the symbol of daring and aggressive grassroots organizing that saved the day for the Democrats. SEIU had leaders and a significant number of lost-time members in several swing states. We’ve seen that unions deploying their members to canvass has repeatedly proven to be highly successful. Now that strategy needs to be amplified. Union “ballot brigades” must be recruited and sent wherever needed to reinforce existing labor-backed campaigns so Democrats pick up the needed seats in Congress. With enough vaccine and better management of the pandemic, door-knocking will hopefully be even more feasible.

Some might call it a “carpet bagging“ strategy. Well-funded labor organizations train, and then use, lost time or other financing to send their most motivated leaders and members to swing districts to engage in conversations about the election with other union members and other working families. Member-to-member canvasses are ideally hosted by the union’s local counterpart or the broader labor movement. There is no better way to build alliances with community and particularly communities of color than to be side-by-side wearing our union colors and carrying our banners. “Labor On the March!”

Success on a large scale will require beginning recruitment and planning now. The effervescent mix of union members, youth and people of color of 2020 must be revived in 2022. Failure to do so risks a “Trumpist” revanchment.

PUSH REFORMS, RECRUIT VOLUNTEERS

Our ability to be effective in 2022 depends on our ability to push the Biden administration now to make the necessary economic reforms to give us ammo to convince millions to desert the talons of Republican extremism. Stewart Acuff, retired Organizing Director of the AFL-CIO, put it well in a recent column in The Stansbury Forum:

“If we want to defeat domestic terrorism, hamstring the authoritarian impulse, and strengthen democracy; we must address income inequality and economic injustice….

“This is a real test for Democrats, and they can’t afford to lose. The party must welcome any breaks with the financial elite and corporations that put excessive profits and wealth above the good of the country.

“And such an economic program, if structured correctly, will cut across all American demographics to improve our quality of life and promote the old ephemeral unity so hard to achieve.”

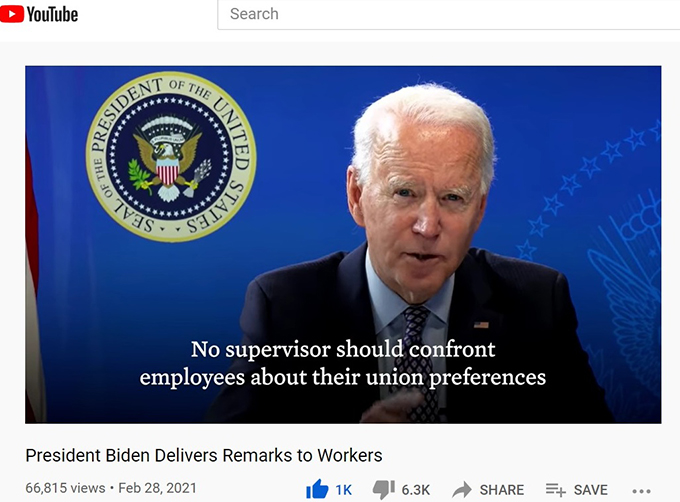

In an extraordinary step, President Biden gave Amazon warehouse workers in Alabama fighting to join a union their biggest support yet. He tweeted a White House video saying workers should be able to make their decision in union elections without pressure from their supervisors or management.

His support was obviously aimed for the Amazon workers voting in an NLRB certification election at a giant distribution center in Bessemer, Alabama. Although Biden did not mention Amazon by name, he referenced “workers in Alabama” facing a “vitally important” vote over the coming weeks. He said unions “lift up workers, both union and non-union, and especially Black and Brown workers.”

It was the strongest support from a sitting president in our lifetimes. Hopefully Biden will repeat it many times between now and November 2022! His doing so will make it easier for us to recruit union members to canvass and convince voters that their votes will actually help create different outcomes.

Let’s start forming the “Union Ballot Brigades” now! Pack your bags, rent the apartments and break in your walking shoes. As Bernie Sanders said, to win “a future you can believe in,” we must defy history in 2022!

This article is being published jointly by Organizing Upgrade and The Stansbury Forum.

…

In Our Country, a Test

By Stewart Acuff

In our country’s coming long fight with the Violent Right, democracy’s best weapon is economic justice.

The roots of the radical right are as old as the American colonies founded on genocide and slavery evolving into a culture of domination and a national doctrine of Manifest Destiny.

But under the immediate ex-president the Violent Right has experienced an upsurge.

When about a hundred of us joined local community activists in Berkeley Springs, West Virginia to hold a BLACK LIVES MATTER rally; we were drowned out, shouted down, all but shut down by more than 400 right-wing bikers, armed and aggressive veterans, and old fashioned peckerwoods. Many of them tried to pick fights or create a riot of violence against us. Law enforcement was dangerously lax and uninterested. I was shocked at how many the right-wing could turn out in a rural community. This all happened only about 100 miles from Washington, D.C.

The fight is real, ongoing, and it must be won. Winning will require a mix of strategies including active engagement of the Department of Justice to pursue and investigate every police shooting, investigate ALL illegal activities of the Violent Right, and take advantage of every opportunity to interrupt their activities. Hell, just investigating active threats would require major investigations.

But that will yield only a long domestic and dangerous guerilla war without eliminating the cause of the of the rise of the Violent Right.

America hasn’t worked for the working class for 40 years, since Ronald Reagan very effectively declared war on working people, breaking unions, privatizing, de-industrializing the heartland, ripping regulations, gutting labor law. In those 40 years Reagan’s war has produced stagnant wages, a labor movement weaker than before the Great Depression, and exploding healthcare costs.

Far from being “Morning in America”, it has been the dimming of the American Dream.

If we want to defeat domestic terrorism, hamstring the authoritarian impulse, and strengthen democracy; we must address income inequality and economic injustice.

America must re-create an American Dream of financial security, adequate income, worker rights, worker power in labor markets and the broader economy, and retirement, free from fear, with dignity and comfort.

This is a real test for Democrats, and they can’t afford to lose. The party must welcome any breaks with the financial elite and corporations that put excessive profits and wealth above the good of the country.

And such an economic program, if structured correctly, will cut across all American demographics to improve our quality of life and promote the old ephemeral unity so hard to achieve.

…

From the Bottom UP

By Stewart Acuff

“Every policy in the package should serve to lift the living standards and conditions of work and life for everyone who works in America.”

Even though he was acquitted in his second impeachment trial, trump is greatly weakened.

Effectively, McConnell and Liz Cheney have split the Republican Party. The factionalizing, the splitting, the back biting, and the ugly underbelly of political knife fighting high up are beginning for real right now.

The GOP hasn’t been so weak since Obama won in 2008.

With his street drag racing start, it’s clear Biden knows the Democratic Party with its hands on all the levers of power must press fundamental change.

Now, early in his first term, the President must drive even harder on pro-worker economic policy. As the GOP reels and exchanges childish insults, Biden should use this moment to unite the Democratic Party, win back more of the working class, and re-orient the building back of the economy focused on its needs.

The President should rollout a comprehensive workers economic agenda with resources and muscle behind it with the expectation the entire party will be on board. The economy is a mess because American workers haven’t had a real raise in wages in 40 years.

An unabashedly pro-worker economic policy might cost the party corporate cash, but it will win votes.

HEADER American economic policy is literally killing workers and their families.

FDR framed his economic policy as an “Economic Bill of Rights”. Message and package the policies any way you want, but every policy in the package should serve to lift the living standards and conditions of work, and quality of life for working families.

There is no better way to demonstrate the contrast with the GOP and attract workers, votes, and power than by economic policy that benefits everyone.

First, we must start at the bottom. So, we must have a plan to raise the minimum wage to $15 an hour and index it to the cost of living so it rises with inflation.

Passing the “Pro Act” should be primary to restore and create a rock-solid right to form unions and bargain collectively. The most efficient, lean, and inexpensive way to reduce wage and wealth inequality is by giving Americans the same workers’ rights as in every other developed nation.

Green energy development is a massive jobs program that is an investment in our future, a sustainable economy, and a healthy and beautiful environment. Green energy and all other infrastructure work must be done union with craft training, safety and health, and prevailing wages.

President Biden can win back more workers in the once industrial Midwest with trade policy that includes enforceable standards on wages, working conditions, and environmental protections. The life of a nine-year-old making shoes or soccer balls must be as important as intellectual property rights. We cannot compete in trade with countries that treat workers as disposable.

In education, making higher education affordable again is critical to working class mobility and opportunity. Eliminating college debt would explode consumer purchasing power amongst the working class.

Gender equality, paid sick leave, and childcare are issues of both social and economic justice.

Beyond economics, there is so much to be done.

We must rebuild democracy with a tough and comprehensive crack down on the Violent Right; Department of Justice Civil Rights investigations of EVERY POLICE SHOOTING, and universal voting rights legislation.

But nothing is more important than a worker first economic policy. It is essential to our democracy.

…

A Firefighter Election: Can a Veteran of Wisconsin Uprising Rescue the IAFF?

By Steve Early

A rare contested race for president of the International Association of Fire Fighters (IAFF) has given its members a clear choice between a union traditionalist from Boston and a progressive activist who backed massive labor protests against Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker a decade ago—and then joined electoral efforts to oust the anti-union Republican.

In mail balloting already underway local union delegates are casting votes on behalf of 320,000 IAFF members throughout the U.S. and Canada. They are choosing a replacement for 75-year old Harold Schaitberger, a full-time union official for more than four decades and a longtime mover-and-shaker in national Democratic Party circles, who announced his retirement last fall. Vying to succeed him are IAFF Secretary-Treasurer Edward Kelly, a 47- year old Air Force veteran and former leader of the union’s Massachusetts branch, and Mahlon Mitchell, a 43- year old African-American from Madison, who heads the Professional Fire Fighters of Wisconsin

Both are energetic, ambitious, and young—by US labor leader standards. But Kelly more strongly reflects the insular “old school” culture of this public sector craft union, while Mitchell, a 2016 Democratic National Convention delegate for Bernie Sanders, has favored Fire Fighter alliances with other public workers facing budget cuts or loss of their workplace rights. Advocating the latter approach put Mitchell in the national spotlight for the first time ten years ago this month. That’s when Walker, Wisconsin’s right-wing governor and the Republican dominated state legislature were pushing Act 10, a law designed to weaken public sector unions—other than those representing police and fire-fighters. Under the strong local leadership of Madison Firefighter president Joe Conway, and with Mitchell newly installed as the union’s statewide leader, the IAFF refused to be part of Walker’s divide-and-conquer strategy.

Instead, Fire Fighters united with other public workers, who were not granted any Act 10 exemption. At rallies and marches involving up to 100,100 people, the charismatic Mitchell was a frequent speaker, attired, as always in his dress uniform. “I saw first-hand his ability to bring people together and make us stronger,” says Justin Pluess, a white fire fighter from Wisconsin Rapids, a small paper mill town in the middle of the state. “His willingness to take on one of the worst union-busting governors ever helped rekindle the labor movement in Wisconsin. He made union members proud to be union again.”

When Act 10 was passed in March, 2011, despite weeks of protests and a peaceful occupation of the state Capitol building, Conway was among the trade union militants calling for a general strike, industrial action which Mitchell did not favor. But Mitchell soon became part of the Wisconsin Democratic Party’s attempt to recall Walker and his Republican Lieutenant Governor Rebecca Kleefisch. In that 2012 recall vote, the governor defeated Milwaukee mayor Tom Barrett by a 53 to 46 percent margin. Running for Lieutenant Governor against Kleefisch, Mitchell received more than 1,150,000 votes and lost by a closer margin than Barrett. Six years later, the Fire Fighter leader finished second in a crowded field of Democrats competing for the chance to oust Walker in the state’s 2018 general election. The primary winner, current Wisconsin Governor Tony Evers, ended up driving the architect of Act 10 from office by less than 30,000 votes out of 2. 5 million cast.

A Class Speaker at Harvard

Mitchell’s current opponent, Ed Kelly advertises himself as the son, grandson, brother, nephew and cousin of fire fighters, in a union where family connections count for a lot. In 1997, he joined the Boston Fire Department, which has been described as the city’s “whitest public safety agency,” despite its now majority minority population. Four years later, Kelly was among the hundreds of out-of-town fire-fighters dispatched to the World Trade Center site in Manhattan after the 9/11 attacks. Kelly was also a first responder to the Boston Marathon bombing in 2013. He was elected president of the IAFF’s Boston local, then its 12,000-member state federation, on whose behalf he did legislative lobbying. In 2015, his union sent “Edzo,” as he’s known, to the prestigious Harvard Trade Union Program, where fellow students chose him to be their class speaker.

Kelly’s dedication to fellow veterans has led, however, to controversial political endorsements and hiring decisions. Last year, in the Bay State, he helped arrange Fire Fighter backing for a former police officer and two-time Trump supporter running for state rep on Cape Cod. West Barnstable, Mass. Republican Steven Xiarhos, who lost a son in Afghanistan, defeated Jim Dever, a labor-backed Democrat who works for NAGE/SEIU, one the state’s larger public employee unions. A Massachusetts labor leader calls that IAFF intervention “a disaster” and describes Kelly as someone who has “gotten a break-and-a-half just to end up where he is now in the union.” After his election as IAFF Secretary-Treasurer in 2016, Kelly hired former Green Beret major Matt Golsteyn, who served with his brother in Afghanistan. A month later, Golsteyn admitted to committing a war crime during a Fox News interview and was charged with murder by the Army. This made him a conservative cause celebre and candidate for White House clemency. In late 2019, Trump pardoned Golsteyn, who then joined the president onstage at a Florida fundraiser that generated $3.5 million for Republican re-election efforts. This was eight months after the IAFF, under Schaitberger’s leadership, had made an early endorsement of Joe Biden’s candidacy. Golsteyn remains at his $236,000 a year union headquarters post as Kelly’s chief of operations.

Kelly’s relationship with Schaitberger worsened last year due to his own covert maneuvering to replace the IAFF president when his term of office ended this winter. Conservative news outlets like The Free Beacon and Wall Street Journal ran embarrassing articles about Schaitberger’s pension benefits and handling of union funds, based on records obtained from Kelly’s office. In an interview with the Intercept, Brian Rice, president of the California Professional Firefighters, described these leaks as a “a veiled coup, a power struggle, aimed at the IAFF leadership,” which threatened to tarnish its organizational reputation. To Kelly critics, like Bryan Jeffries, head of the Professional Fire Fighters of Arizona, they also seemed to be the work of “some very right-leaning elements within our union.” Instead of running for re-election, Schaitberger decided to retire, leaving the field open for a contested race for the union’s top job, which pays $371,000 a year, five or six times more than the average fire-fighter earns.

Local Endorsements

Because of the pandemic, the IAFF held a virtual convention in late January, which enabled many more of its small locals to participate. About 70% of all IAFF affiliates have fewer than 50 members, but the union’s internal politics tend to be dominated by its bigger city locals. The 3,323 delegates now casting weighted ballots, based on their local’s membership size, have been wooed on-line and in person by both the Kelly and Mitchell campaigns. Neither candidate has been endorsed by a majority of IAFF locals. Kelly has his strongest support in his native northeast, although after union officials in Philadelphia endorsed him without sufficient rank-and-file in-put, angry members forced a re-vote which revealed nearly equal support for the two candidates. In northern California, Mitchell is backed by the 30,000-member state Fire Fighters organization, plus San Francisco Local 798, Oakland Local 55, and other IAFF affiliates in Berkeley, Hayward, Milpitas, San Jose, and Sacramento.

Both candidates have campaign websites showcasing their latest endorsement videos. But Mitchell has twice as many Facebook followers as Kelly, and he posts links to substantive discussions, conducted via Zoom, with rank-and-filers around the country. Kelly has rejected Mitchell’s repeated demand for a “face-to-face” debate—despite no shortage of issues to discuss. While fire fighters have won good pay and benefits in parts of the country with strong public sector bargaining laws, those working in some “right-to-work” states lag far behind. Many are able to retire early but then lack affordable pre-Medicare age health coverage. As the New York Times reported recently, “the safety of firefighters has become an urgent concern amid the worsening effects of climate change, which bring rising temperatures that prime the nation for increasingly devastating fires.” Adding to that threat is on-the-job exposure to carcinogenic chemicals in the protective equipment that firefighters have worn for years; in 2019, cancer caused 75 percent of all active duty firefighter deaths. During his campaign, Mitchell has made such occupational hazards and better mental health coverage a major focus. And, his backers believe, he will be a far better strategist in the union’s upcoming fight to protect fire services from a cascade of Covid-19 related state and local budget cuts.

A Toxic Workplace?

While some Mitchell supporters rate the contest as “neck and neck,” the candidate representing greater diversity and change is competing on tough electoral terrain. The workforce represented by the IAFF is more predominantly white and male than the U.S. military and even local police forces. Fewer than 8 percent of all U.S. fire fighters are African-American and few have risen, like Mitchell, to leadership positions. Even in Canada, where the IAFF has 23,000 members, an increasingly diverse city like Calgary (which has a Muslim mayor) has few women firefighters and its black or indigenous ones have been subjected to years of hazing, harassment, and racial slurs.

Although the IAFF backed Biden last year and Hillary Clinton in 2016, one official from another union who spoke at a Fire Fighters national convention just a few years ago was warned beforehand that his audience was heavily Republican. When Mitchell himself addressed IAFF convention delegates, during his 2018 bid to become Wisconsin’s Democratic gubernatorial nominee, he criticized his home-state for having the highest African-American incarceration rate in the country. It was not a big applause line before a largely white crowd otherwise sympathetic to his political advocacy for the union and its job-related causes.

One IAFF member who’s definitely rooting for Mahlon Mitchell, when the ballots are counted on March 4, is Andrea Hall. She’s the first-ever African-American female fire captain from Fulton County, Georgia, who now serves as president of IAFF Local 3920. On January 20, she impressed millions of U.S. presidential inauguration viewers by reciting the Pledge of Allegiance, while providing her own American Sign Language version while she spoke. Similar dexterity, in addressing multiple audiences, has been a key part of Mitchell’s own past success as a IAFF trail-blazer. It remains to be seen whether it will get him to the top of the union ladder this time around.

…

“A fascinating fight for a man’s place in our time”

By Ousmane Power-Greene

Book Review

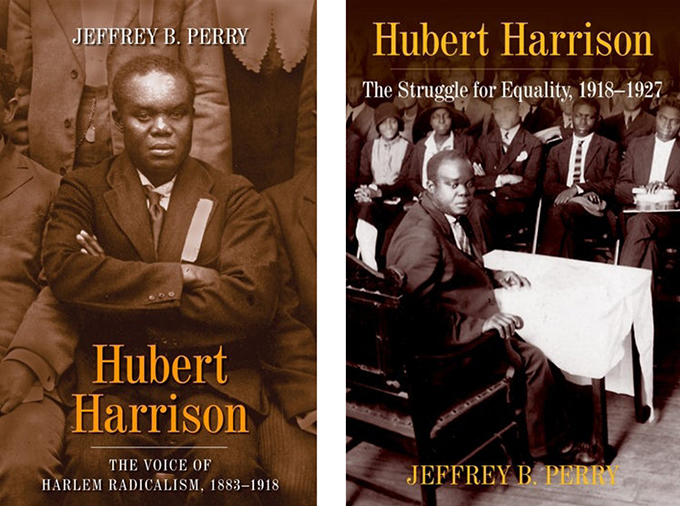

Jeffrey B. Perry, Hubert Harrison: The Voice of Harlem Radicalism, 1883 – 1918. New York: Columbia University Press, 2008.

Jeffrey B. Perry, Hubert Harrison: The Struggle for Equality, 1918-1926. New York: Columbia University Press, 2020.

.

As black socialist Frank Crosswaith once wrote, “The story of the New Negro’s fascinating fight for a man’s place in our time is the story of Hubert H. Harrison. And when the impartial historian writes the history of the black man’s bid for a square deal, he will be building, with the written word, a monument to Dr. Harrison which will stand for all time as a symbol of inspiration to the men and women of the Negro race as they move forward to positions of power, prestige and pride.” With the publication of Jeffrey Perry’s groundbreaking two-volume biography, Hubert Harrison: The Voice of Harlem Radicalism (2008) and Hubert Harrison: The Struggle for Equality(2020), scholars, activists, and community organizers have a study of the life and ideas of one of the most important black radical intellectuals of the twentieth century. For over forty years, Jeffrey Perry has been researching and writing about Hubert H. Harrison despite his marginalization among those scholars who research the New Negro movement or “Harlem Renaissance”. Thus, readers have only a glimpse of Harrison’s importance in works, such as Phillip S. Foner’s classic, American Socialism and Black Americans: From the Age of Jackson to World War II and Winston James, Holding Aloft the Banner of Ethiopia: Caribbean Radicalism in Twentieth-Century America. Since 2000, however, Harrison’s writings and speeches have appeared in edited collections, such as Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Gene Andrew Jarrett, The New Negro: Readings on Race, Representation, and African American Culture, 1892-1938 (2007).

Simply put, Perry’s Hubert Harrison demonstrates Harrison is the key link between early twentieth century black radicalism and the Marxist tradition that shaped the ideological vision of leaders, such as Marcus Garvey and A. Philip Randolph.

“Harrison’s public criticism of Booker T. Washington brought the Wizard of Tuskegee, as Washington was known then, to use his influence to have Harrison fired from his job”

Born in 1883, Hubert Harrison immigrated to America from the Caribbean island of St. Croix as a seventeen-year-old orphan in 1900. Without much evidence about Harrison’s early life, Perry provides a thorough examination of the key events in the Danish Caribbean that influenced the young Harrison to leave his home for the United States. When Harrison arrived in New York in 1900, he entered a city where blacks were limited to menial jobs and lived in the worst tenements. The oppressive conditions blacks endured in Manhattan did not discourage Harrison, and he soon found his way to the lyceums at St. Benedict’s and St. Mark’s where he met other black working-class intellectuals such as John Bruce, a lay historian and journalist, and Arthur Schomburg, the legendary bibliophile and collector of African artifacts. Within this context, Harrison refined his oratory skills by overcoming a lisp and developed his ideas about the role of race and class in American history.

Eager to earn a living through his writings, Harrison published book reviews in newspapers, such as the New York Times, making him one of the earliest African Americans to do so. While Harrison’s intellectual gifts were apparent in his book reviews and lectures, he struggled to earn a decent living from his writings, and this forced him to seek other means to support himself. Harrison took a position as a postal worker in 1907, and Perry explains that such role was one of the best paying jobs for African Americans at that time. By linking up with fellow postal workers, Harrison joined a study circle to discuss, among other things, the challenges black people faced in New York City and the nation. In this context, Harrison found a satisfying space to develop his ideas and share his own historical work on the Reconstruction era, which he hoped to have published.

Harrison’s companionship with other black postal workers would end, however, when Harrison’s public criticism of Booker T. Washington brought the Wizard of Tuskegee, as Washington was known then, to use his influence to have Harrison fired from his job at the Post Office. As Perry recounts in startling detail, Harrison was fired for writing several letters to local papers that criticized Booker T. Washington’s statements abroad, which Harrison believed had downplayed African Americans’ plight in the United States. On the surface, it would appear that Harrison’s removal was a consequence of complaints he had made over an unjustified reduction of his salary, but, as Perry proves, Booker T. Washington’s friend Charles W. Anderson bragged about how he orchestrated Harrison’s termination in a letter to Washington in September 1911. By the end of the month, Harrison would be removed from his position at the Post Office, and this would cause turmoil for Harrison’s family, forcing him into poverty.

Although losing his job at the post office caused his family financial hardship, Harrison used this bleak circumstance to pursue full-time employment with the Socialist Party as a lecturer. Although there is tremendous uncertainty surrounding the date when Harrison actually joined the Socialist Party, Perry argues that it most likely happened in 1911 after he was fired from the Post Office. Between 1911 and 1912, Harrison became “Local New York’s foremost Black speaker, its leading Black organizer and theoretician, and the head of the Colored Socialist Club,” according to Perry (173). Yet, Harrison’s efforts to recruit more blacks into the Socialist Party were challenged, as Perry explains, by “conservative party leaders” who at the local and national level failed to adequately deal with the question of how to bring black people en masse into the Socialist Party, while changing white supremacist attitudes rampant among many of its members.

“We say Race First, because you have all along insisted on Race First and class after when you didn’t need our help.”

By the end of 1912, Harrison had gravitated toward the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) brand of socialism. Yet, when the Socialist Party rejected the IWW’s advocacy of a more militant politics, Harrison found himself, once again, at odds with party heads. In fact, Perry writes that, “Harrison found that support of his work by leadership of Local New York was waning,” (175) and this has been linked to W.E.B. Du Bois’s vocal criticism of Harrison’s quest to form socialist branches within predominately black New York communities. This ideological riff with those who supported Du Bois’s position would soon drive Harrison from the Socialist Party.

The specific circumstances surrounding Harrison’s departure from the Socialist Party surrounded his negative response to an Executive Committee command for him to forgo a debate with a well-known anti-socialist speaker named Frank Urban. Perry writes that “the ideological break, followed by the suspension, marked a major turning point” in Harrison’s life. Yet, this re-orientation away from the Socialist Party did not mean that Harrison renounced socialism, and Harrison continued to view himself as a socialist throughout his life.

Perry points out that Harrison’s break from the Socialist Party led him to focus on organizing African Americans in opposition to race-based oppression in the United States and abroad. Harrison’s shift from a “class first” position to “race first” position was distinct for this time period. In his oft-cited essay, “Race First versus Class First” Harrison explained: “We can respect the Socialists of Scandinavia, France, Germany or England on their record. But your record so far does not entitle you to the respect of those of us who can see all around a subject. We say Race First, because you have all along insisted on Race First and class after when you didn’t need our help.”[1] By 1915 he would become one of the leading New Negro radicals, coining the phrase “Race First,” and emerging as its most influential and visible leaders.

Over the next three years, Harrison provided black Harlemites with an unfettered voice that called out all who opposed militant action against racism in the court of public opinion. Harrison’s outdoor lectures established him as one of the most visible public orators, who, as his contemporaries pointed out, had earned near icon status for his “encyclopedic” grasp of a wide variety of social, political, and scientific topics. Those who listened to his soap box orations walked away enlightened, humored, and aware of a new strain of race radicalism that sought to include the masses, rather than a talented tenth, in the struggle for civil rights, political power, and economic independence.

In 1917, Harrison founded the Liberty League of Negro Americans and became the editor of its organ, The Voice. This organization was the first of its kind in Harlem, and Harrison used mass meetings and editorials in The Voice to call for “equal justice before the law and equal opportunity” regardless whether or not such demands bumped up against the social norms or powerful leaders. One of the organization’s central aims was to “Stop Lynching and Disenfranchisement in the Land Which We Love and Make the South ‘Safe For Democracy’” (282). The Liberty League boasted a broad array of African Americans from various backgrounds, political affiliations, and class positions. Several of the Liberty League’s most notable members were Marcus Garvey, Reverend Adam Clayton Powell Sr., and Madame C. J. Walker.

By 1918, Harrison’s influence had extended beyond Harlem and into a national arena. The Boston-based newspaper editor and racial agitator William Monroe Trotter (also a member of the Liberty League) found in Harrison an able ally in the struggle against white supremacy in America and throughout the world. Jeffrey Perry illustrates Harrison’s rise to national prominence through his role at the Liberty Congress in Washington, D.C. in June 1918. Attended by 115 delegates from 35 states, the Liberty Congress, as Perry explains, “was a precursor to the March on Washington Movement during World War II (led by A. Philip Randolph) and the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom during the Vietnam War (led by Randolph and Martin Luther King, Jr.) (381). Those in attendance called on lawmakers to make lynching a federal crime, to enforce the Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, and to compel the President and Congress to recognize the link between justifications for U.S. involvement in the war in slogans, such as “to make the world safe for democracy,” and the just treatment of African Americans who endured race riots, lynching, and discrimination. Having been nominated unanimously as president of the congress, Harrison now had a national constituency, and he used his platform to challenge the leadership of other African Americans, such as Du Bois’s whose “Close the Ranks” editorial in The Crisis magazine called for patriotism during the height of racist mob violence against black people in cities throughout the nation.

“With more wit and wisdom than Marcus Garvey, and deeper roots in the black community than Alain Locke, Harrison straddled white leftist intellectual circles and black radical street corner politics in ways that were unmatched by his contemporaries.”

Through Perry’s prodigious research we have a portrait of a committed man, unwavering in his struggle to eradicate racial prejudice in America and abroad, who provided others with a theory for race advancement in his time and for future generations. There were three pillars of Harrison’s efforts: First, a race consciousness rooted in a class consciousness that depended on community engagement. Second, the central role the black intellectual and critic in shaping the way black and white people interpreted literature and culture. Finally, a program, based in black communities, that approached the struggle for racial justice through an international lens. Perry not only documents in careful detail Harrison’s effort towards these ends, he shows the ways Harrison’s visibility within the Harlem community broadened his base of supporters.

With more wit and wisdom than Marcus Garvey, and deeper roots in the black community than Alain Locke, Harrison straddled white leftist intellectual circles and black radical street corner politics in ways that were unmatched by his contemporaries. Although A. Phillip Randolph, and Marcus Garvey had been known to criticize nearly all black rivals, these two giants of black nationalism and labor radicalism never committed one printed word of condemnation toward Harrison. Beyond activists, Harrison also earned the respect of white critics H.L. Mencken, playwright Eugene O’Neil, and black poets and artists often associated with the “Harlem Renaissance,” such as Claude McKay, Augusta Savage, and the actor Charles Gilpin.

Jeffrey Perry’s biography shows that Harrison was no closet intellectual, fomenting self-indulgent ramblings about racial injustice, the oppressive nature of capitalism, or the failure of the American dream. Always a man of the people, Harrison was in fact the consummate public intellectual, and for much of his life, as Perry explains, he remained dedicated to advocating in behalf of those who lacked power not for his personal benefit, but for the broader public good. As a public intellectual for and among poor black people, Harrison’s life has much to teach us about the dignity of working on behalf of those without jobs, political clout, or formal education. Whether lecturing on a Wall Street corner, or in Harlem, Harrison used his extraordinary intellectual gift to encourage those less educated to join in the conversation, to become informed, to be free thinkers, to agitate for rights, to stand up to so-called leaders and demand more. He called on those with power and influence to put aside pettiness, and to unite for a common cause.

Perry’s primary accomplishment, then, is that he presents readers with a thorough rendering of the Harrison’s life within a community of black and white activists intellectuals, striving to organize toward race and class equality. Not only does Perry’s biography chronicle Harrison’s efforts, it also places Harrison squarely within the major Progressive movements and New Negro Movement in the early twentieth century. Harrison’s broad array of admirers, from opposing political camps and various intellectual persuasions, attests to Harrison’s significance, and, indeed, as Perry shows in this excellent biography, his commitment to the struggle for equality made him the voice of Harlem radicalism.

Over the past five years, several other biographies of central figures of the early twentieth century, most notably Jeffrey C. Stewart, The New Negro, The Life of Alain Locke (2018) and Kerri Greenidge, Black Radical: The Life and Times of William Monroe Trotter (2019), have provided greater attention to figures who dominated the era often identified as the “Harlem Renaissance” or “New Negro Renaissance.” For this reason, Jeffrey Perry’s two-volume biography fits squarely within the context of revived interest in early black radicalism on the one hand and art, literature, and intellectualism on the other hand. Yet, Perry’s biographical treatment shows Harrison’s centrality within, and among, radicals, artists, intellectuals, who have come to understand this monumental Afro-American, Afro-Caribbean radical intellectual.

…

[1] Hubert Henry Harrison, When Africa Awakes, Baltimore, MD: Black Classic Press, 1997), 81.

Remembering Frank Soracco

By Mike Miller

Frank Soracco was a friend of mine. He died from heart failure at the end of 2020. We met during my late 1962 to end of 1966 days as Bay Area regional representative for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

In 1964, Frank, son of a Placerville, CA, Republican doctor, a high school teacher and football coach, showed up at our “Snick” office to volunteer. For a couple of months, he participated in fund-raising, education about the Deep South civil rights movement, political pressure on the Federal Government, and volunteer recruitment activities. By the Fall, as had happened to me the year before, the compelling drama of what was happening in the South drew Frank to go. He packed his VW Bug and headed for Selma, Alabama. He participated in door-to-door canvassing to convince local people to attempt to register to vote—which in those days could lead to firing, eviction, denial of loan applications, home firebombing, beating and death. Frank earned the trust of local people and SNCC staff.

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) was invited by the local Dallas County Black political/citizenship organization to come to Selma. That caused resentment among SNCC people; Frank wasn’t one of them. He fully participated with SCLC in the organizing work for the important Selma marches. Those marches, the largely SNCC-organized Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party’s challenge to the 1964 Democratic Party Convention seating of its racist Mississippi state party, and challenge to the January, 1965, Congressional seating of the State’s racist House delegation, led to passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

There were several marches, some accompanied by police violence, others protected by a federal presence. Frank was so respected by that time that he was named co-marshal for the marches with SNCC’s Ivanhoe Donaldson.

During the violence of “Bloody Sunday” march Frank was attacked with cattle prods and billy-clubs as he ran from the police. He came upon Rachel West, a local nine-year-old frozen in place and crying, swept her up in one arm, like he was picking up a football, and rescued her.

She later wrote her story in Selma, Lord, Selma, which became a Disney film, and was interviewed by the producers of Eyes on the Prize, the classic PBS documentary on the period: “If he hadn’t grabbed me,” she said, “I don’t think I’d be here today.”

On one occasion Frank was arrested by Selma police and thrown in jail with Martin Luther King. Therein lies an illustration of Frank’s character.

It is important to know that the law enforcement mix in Selma included Police Chief Wilson Baker, intent on avoiding the kind of violence erupting elsewhere in police encounters with civil rights activity and convinced it was the strategic way to kill “The Movement”, and the brutality (baton beatings, intimidation with police horses, use of cattle prods) of County Sheriff Jim Clark and State Trooper Director Al Lingo.

Recognizing their differences, Frank started talking with Baker, hoping to develop some kind of relationship with him that might help civil rights. Frank was one of the most relational people I’ve ever known, so this was not out of character.

Frank, Martin Luther King and hundreds of others were arrested because they violated a local law requiring permits for public marches. Baker put Frank in a cell with King; that was illegal. Like everything else in Alabama, jails were segregated. I thought a lot about that incident. The only thing that explains it is that Baker knew Frank would be badly beaten in the white cell and didn’t want that to happen.

About 20 years later, when Taylor Branch was working on Pillar of Fire, the second volume of his important trilogy The King Years, he interviewed Frank, and asked him who he might talk with to get a Selma white’s view of those times. Frank proposed Baker’s widow, set up the interview and accompanied Branch to meet her. That’s the kind of person Frank was.

Frank left SNCC in the mid-1960s, moved to Los Angeles, used his SNCC organizing skills and contacts with “friends of SNCC” to raise the startup money for what became the successful Marina Del Rey restaurant, The Fiasco. He built a small apartment underneath the restaurant where he hosted SNCC and other friends who traveled to LA, often with free meals upstairs for people far less financially successful (me among them) than he had become.

He was a generous donor to ORGANIZE Training Center, the nonprofit I direct.

Frank made the world a better place.

…