A call to action….

By Peter Olney and Rand Wilson

Union leaders: no deals with Uber and Lyft!

Trade union members, and everyone else supportive of workers’ rights, should be very concerned about proposed legislation in New York, Massachusetts, and other states that would allow limited bargaining rights for independent contractors of Transportation Networked Companies (TNCs) like Uber and Lyft.[1]

The New York bill (and similar legislation proposed in Connecticut and Massachusetts) establishes a framework for TNC employers and drivers to jointly participate in an industry council.[2] It proposes a “work-around” to avoid violations of the Sherman anti-trust act that will allow the TNCs to engage in what would normally be prohibited price fixing. It establishes a procedure to give a qualifying organization limited collective bargaining and representation rights pertaining to the wages and working conditions of the TNC drivers.[3],[4]

However, these bills raise some serious concerns. While Uber and Lyft claim otherwise, gig drivers are clearly their employees under “A-B-C” tests that are generally used to determine if workers are misclassified as contractors. When subjected to the test, state attorney generals are finding the TNC’s are misclassifying their drivers in violation of their state’s employment law.[5]

Sadly, these “third way” or “contractor plus” bills are backed by some unions seeking to make backroom deals with the rideshare companies to increase their membership without actually organizing workers. Both the Transport Workers Union (TWU) and Machinists union (IAM) are on record backing the New York legislation.

Giving the TNC drivers “representation” as independent contractors makes a concession to the TNCs that labor unions are prepared to accept the current violation of existing state law – contradicting the position of the courts, state legislatures, advocacy groups like the National Employment Law Project (NELP) and the national AFL-CIO.

These unions have argued that as long as the rideshare drivers are contractors, “third way” representation is necessary in order to give them a much-needed voice. They say their proposed legislation wouldn’t prohibit a change in status if the state or federal governments upgrade drivers to statutory “employees.” However, their support for a middle ground will almost certainly be used to argue that state legislatures or the federal government recognize these gig workers as independent contractors. For example, in Massachusetts, the state Supreme Judicial Court ruled in a case regarding real estate agents that another unrelated statute recognizing that agents may be independent contractors was effectively a “carve-out” for that industry from the A-B-C test in Sec. 148B.[6]

Without a doubt, the movements by gig drivers for better wages and working conditions across the country — and around the world — is motivating the companies to seek a “compromise” with labor that would give them the appearance of taking steps to make improvements. In reality, if Uber, Lyft (and some unions) have their way with these bills, the drivers’ demands for respect and compassionate treatment could never be achieved.[7]

“We California drivers know what this kind of industry supported legislation means: the companies will do anything to maintain their ability to pay us far less than minimum wage, pay nothing toward the operation of our vehicles, while maintaining no responsibility to fund the safety net needed in this precarious and often unsafe job,” said Nicole Moore, a leader of Ride Share Drivers United (RDU) in Southern California. “Under their new Prop. 22 law in California, drivers are making even less money — as little as 32 cents a mile. Sadly, now it is totally legal. The ‘flexibility’ protections the gig companies bragged about have actually led to less flexibility and less freedom to earn.”

Making any public concession recognizing the drivers as contractors now, will seriously undermine labor opposition to allowing Uber and Lyft to water-down — or eliminate — state A-B-C tests. Support for this “third way” legislation plays right into the companies’ hands, allowing them to twist this proposed legislation to confuse our elected officials and the public by showing that some unions are willing to accept classifying gig workers as independent contractors.

It’s no coincidence that Uber, Lyft and other TNCs are looking to use opportunistic unions as “allies.” This year labor, and many economic and social justice groups have begun an epic battle to strengthen labor law through the national PRO Act.

The movement against misclassification is also gaining momentum. Last January, more than 70 unions, advocacy groups and other organizations — including the National Employment Law Project, AFL-CIO, AFSCME, Teamsters and NAACP, sent a letter to Congress urging lawmakers to reject legal frameworks such as California’s Proposition 22, which exempts employers from treating gig workers as employees.[8]

The letter stated, “Millions of workers hired and managed by companies via internet apps, such as Instacart and DoorDash delivery workers, Uber drivers, and Handy home service workers, are deprived of basic labor protections that many of us take for granted… Because their employers insist on unilaterally calling them ‘independent contractors,’ these workers don’t get a minimum wage, overtime pay, workers’ compensation, unemployment, state disability insurance, or access to federal protections from discrimination, including sex harassment.”

“A proposal to supposedly provide limited benefits to some ‘independent workers’ would threaten our most fundamental understanding of what work ought to provide,” the letter added. “A federal ‘Proposition 22’-like scheme would shunt more and more workers to piecework labor, performing jobs here-and-there with neither individual security nor the possibility of collective action.”

Another serious concern regarding these third way schemes is how the unions are proposing to fund workers’ representation. Instead of members paying dues, the legislation would enact a small surcharge on passenger fares to pay for expenses incurred for representation. The surcharge makes the qualifying union organization essentially employer funded, crossing an important prohibition in the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) against employer funding or support for a labor organization.

“A passenger tax is a great way to ensure a fire hose of funding into a union,” added RDU’s Moore. “But where’s the accountability to the workforce? Where’s the guarantee that we are building real power and leading our own fights? This law acts like the union is the Social Security Administration. It’s not – dues give us independent funds to build real power. We need to be classified correctly as employees and have the protections and benefit/wage floor of employees – not something that assigns us a permanent second class worker status. We are a majority immigrant and Black Indigenous People of Color workforce. Where is the equity and power in this compromise of our rights?”

Proposed low thresholds of driver support to trigger “voluntary recognition” from the TNCs is an invitation to sweetheart deals. Majority support for a union is the underlying foundation for worker empowerment. What sort of power will a qualifying organization have with only 10% support? True worker power is built through authentic organizing by workers, their union using its collective power to take advantage of their strategic position in the economy, and existing state and federal labor protections.

Since the passage of Prop. 22 in California, other employers in health care, retail, hospitality – even the Pentagon — are openly looking to shift to managing their workers through digital apps, or outsourcing them through temp and staffing firms, to escape their employer obligations.[9] Legislation enabling this new scheme could break open the dam, incentivizing entire industries to “gig out” more jobs that once provided living wage jobs and a measure of prosperity.

Passage of this legislation could set a very dangerous precedent for Teamster drivers and UFCW grocery delivery workers.

The gig economy, epitomized by employment at Uber and Lyft and similar companies, is a segment of the labor market literally carved out of pro-worker regulation. These companies want to be exempted from an obligation to respect workers’ rights. What’s at issue here is how large we will permit it to grow. Passage of this proposed legislation will further solidify these workers’ status as independent contractors and weaken labor’s efforts at the state and national level to have these workers classified as actual workers with full benefits and real collective bargaining rights.[10]

RDU’s Moore summed it up succinctly, “We’re fighting some of the biggest union busters and richest corporations in the world. We need a real union with real app-based worker leadership to be willing to fight. What if the union isn’t representing us well? They don’t even need us to pay dues – and there is no democracy in 10% of drivers signing a card!”

“Drivers in NYC have fought hard to ensure that they are paid more than minimum wage for all of their time on type job. This bill would ensure that drivers are paid for only the part of their time while picking up a passenger. It codifies the destruction of rights agreements drivers have already won in NY. It is a way to bust the union Lyft and Uber drivers have already built in New York City – with the New York Taxi Workers Alliance.”

Unions should not support legislation creating a compromised and weak voice for independent contractors. Labor must stay united to defeat any effort to undermine the A-B-C test and fight for more workers to have access to our federal and state employment protections.

…

[1] “Lawmakers Look to Spruce Up Gig Work Rather Than Replace It,” by Josh Eidelson, March 18, 2021, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-03-18/lawmakers-look-to-spruce-up-gig-work-rather-than-replace-it

[2] “A Bill Requiring Regulation of Network Workers, and Providing for Their Protection and Benefits,” https://aboutblaw.com/XEJ

[3] “Labor, Gig Companies Near Bargaining Deal in N.Y.,” by Josh Eidelson and Benjamin Penn,

May 17, 2021, Bloomberg, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-05-18/labor-gig-companies-are-said-to-be-near-bargaining-deal-in-n-y

[4] “BREAKING: Draft Legislation in New York Would Put Gig Workers into Toothless ‘Unions’,”

May 21, 2021, Joe DeManuelle-Hall, Labor Notes, https://labornotes.org/2021/05/breaking-draft-legislation-new-york-would-put-gig-workers-toothless-unions

[5] AG Healey: Uber and Lyft Drivers are Employees Under Massachusetts Wage and Hour Laws, https://www.mass.gov/news/ag-healey-uber-and-lyft-drivers-are-employees-under-massachusetts-wage-and-hour-laws

[6] Monell v. Boston Pads, LLC, 471 Mass. 566 (2015)

[7] Gig Workers Demand Occupational Death Benefits, Coworker.org, https://www.coworker.org/petitions/gig-workers-demand-occupational-death-benefits

[8] https://www.nelp.org/wp-content/uploads/Letter-to-Congress-Labor-Protections-App-Based-Workers-January-2021.pdf

[9] “The Military Is Creating a ‘Gig Eagle’ App to Uber-ize Its Workforce,” by Edward Ongweso Jr, May 20, 2021, Vice, https://www.vice.com/en/article/n7bzvw/the-military-is-creating-a-gig-eagle-app-to-uber-ize-its-workforce

[10] For more along these lines see, “Sectoral Bargaining: Principles for Reform,” a statement signed by dozens of scholars endorsing six principles as starting points from which to consider sectoral bargaining reforms similar to SD 473, https://concerned-sectoral-bargaining.medium.com/sectoral-bargaining-principles-for-reform-7b7f2c945624

Living with uncertainty

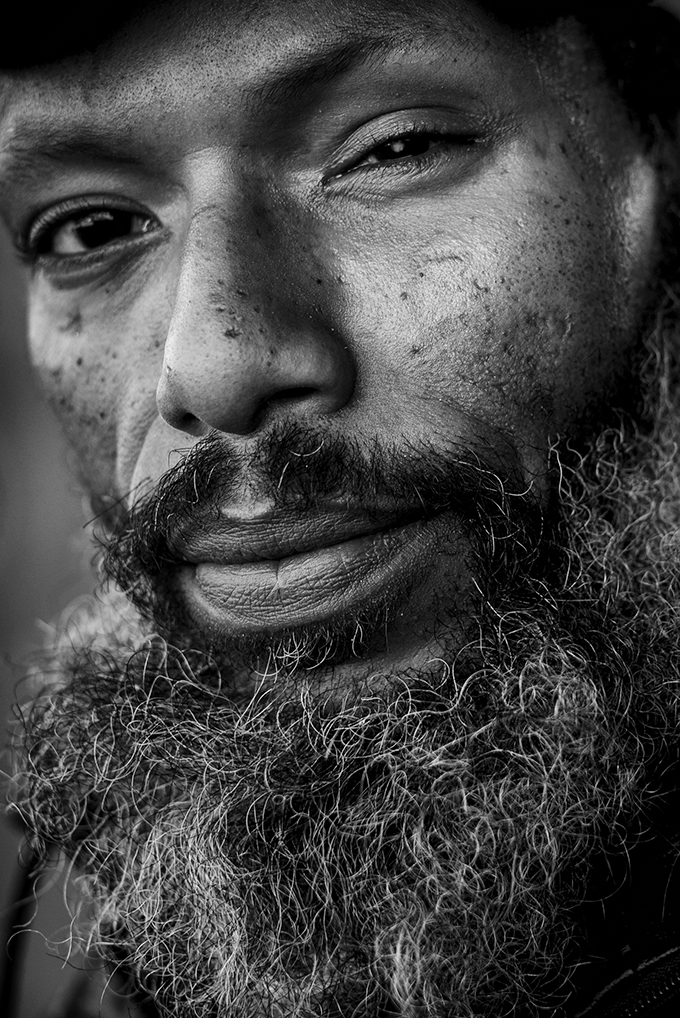

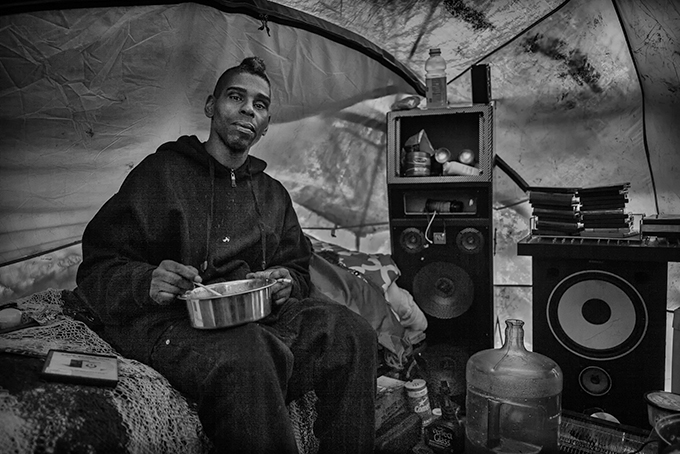

By Robert Gumpert

As is the case in all parts of the United States, indeed around the world, too many people are “unhoused”, living day to day with shelter uncertainty.

San Francisco, home to staggering amounts of wealth and innovation is also home to people who live in tents, boxes, cars, RVs. On a couch here, a couch there, or directly on the ground in sleeping bags, packing blankets, or the remnants of Amazon packing boxes.

In San Francisco tomorrow, on two parking lot between Merlin and Morris streets, about 40 people will be evicted from spaces they have “lived” at for between a few months and 5 years because … well there is always a reason. What is never answered fully is why these folks, why here, why now. The lots are owned by Caltrans and were operated by a parking contractor who went bankrupt.

Here are four of the “residents” and a few of their thoughts.

(I’ve been here) all together about 5 years. I have a place, like I said, I can’t afford a, I would have to win the Power Ball to be able to afford a house here. I’ve always had mobile homes before, a “camper”, you know. They’ve gotten towed, a couple of them, so I’m down to this (a box truck). But I’ve always had my own place where I rent or parked. I’ve rented here (a spot in a parking lot) for about 5 years until they declared bankruptcy and gave the place (the parking lot) up. I’m just looking for another place to rent space for my vehicles, a place I could but a small trailer.

That’s how I live. I’d rather live this way than in an SRO and not be as happy and secure. I like to have my own place. I can come in when I want, have my stuff, don’t have to look anybody in the eye when I come in and out, you know. And be me, just like you, you know what I’m saying.”

“Maintaining. It’s hard out here, like as far as showers and food and, security.

It (living on the street as a single woman) got to be self-sufficient and take care of myself, nobody else to do it for me.

We’re kind a like segregated down here. We got people at one end and then there’s people at the opposite end, we kind a stay to ourselves.

(I miss) being with my kids. Yeah, it sucks. Once I get my housing back my kids will be home but it’s hard. Stuff is like irritating. COVID hit and then everything just came to a halt. So now I got to wait.

They (the city) leave us here to fend for ourselves with no resources at all. The only time we do get resources is when we raise hell and cause problems for them.

“I was homeless from 2007 to 2012 and then I became housed through DAAH. I moved in there about 2012, or 2013, and when I moved in there from the very beginning it seemed as if I was targeted. The staff was very difficult to deal with, and just very unpleasant. But I stayed and I thought that maybe I needed to adjust myself. Or maybe I needed to take a step back and take a look at things further. Maybe I’m being treated fairly and I’m not giving people the benefit of the doubt. Well as a human being we’re born with certain things that tell us when something’s not right, or when something’s wrong. Bottom line is that I never felt like I was being treated right from the very beginning. The slowly but surely things started to happen with the tenants. Everybody comes with psychosis issues in those buildings, or disabilities of some sort, myself included. What happens is administration starts to personalize things, so they target you. Next thing you know you’re getting written more, you’re under a microscope. Then you’re being evicted for small reasons, things that only warrant a warning or disciplinary action. There is such a disconnection with the tenants and the staff that there’s no community. You know it’s supposed to be that kind of healthy community originated environment, (but) everybody is walking around in the SROs mad. Very angry and upset. While I’m there I’m not happy, I’ve been assaulted on multiple occasions, asked to be moved, but I was told they don’t do that. … The police downplay everything that happens in the SROs, it’s almost as if they don’t want to take the report, would rather settle it right there, but that doesn’t get anything done. Someone went in my building and killed my dog. Finally, I got fed up and I left. I just go and I pay my rent. Once COVID hit I just even didn’t go back to the building. I’ve just been living out here on the streets. I’m safer out here than I feel like I am in there. I go in my unit and I can feel like somebody’s been in my unit and when I discovered how they were getting in, they (managers) said they had remediated the problem, they didn’t. I’m in court with them Friday to determine some kind of settlement, if they’re going to put me out. If that’s what they are trying to do, what are they going to do for me for everything I’ve been through? You have rodent problems. You have staff issues. Discrimination issues going on in the building, I’ve had all those issues happen to me. I was sexually assaulted in the building, made a police report and they said they couldn’t do nothing about it. I filed reports with DPH asking to be moved. I went to City Hall, I went to the Department of Building and Inspection, I went the people who investigate if people are discriminating against you, and then I went to the rental board. All these places failed me. Nobody could help me. There was nobody to oversee what happened to me at that SRO.”

“(The hardest thing about the street), the harassment, social indifference. The way that people, you know the authorities, address you. They act like it’s my fault. I’m pretty sure, myself, and a lot of these people, if the resources were available, we would take them. Not no hotel room for a couple months and then kick us back out on the street to do this whole recycle thing again because it generates currency, it generates money. They’re getting paid off peoples’ misery.

“They moved us out of this aisle and told us to pack up, that they were sending out resources, that they were going to put us in hotel rooms. We packed on the corner and streets well into the night and no one came, and so I said let’s go in this parking lot. People still park their cars here; we don’t allow peoples’ cars to get broken into. People call the cops on us because they feel some type of social righteousness, that we’re doing something wrong because that’s how it’s portrayed through media. If social indifference continues to happen, they’re going to feel they can do whatever they want to us and not have to worry about any type of repercussions. I don’t understand how that’s right. If you’re moving us off the streets because we’re on the streets, then that means that San Francisco has an obligation to house its citizens. Not just place them in hotels, rundown hotels, that been condemned since ’89 (the earthquake) and cannot be reopened unless all the requirements of building inspections, safety codes, are met. This is not happening. Take for instance the Marathon Hotel, there’s holes in the roof and people are still living there. These are the homeless people that they take off the streets from a bad situation and put them into a worser one. It’s all designed so that you can be kicked out. San Francisco, there not addressing the homeless crisis that’s happening out here in the wealthiest city in the United States of America, and I don’t understand what’s going on. They’re moving (us) and they’re using fear of incarceration to intimidate because people on parole and that’s not right. You’re taking a hopeless person in a desperate situation; you’re provoking them to have some sort of negative episode. It’s going to drive people insane. What do they think going to happen? Now you provoke this situation and everybody’s watching. Not just Americans but other people in other countries are watching America, “home of the brave land of the free”. It don’t feel very free, don’t feel very free at all.”

…

All photos copyright Robert Gumpert 2021

A DEMOCRATIC FOOD SYSTEM MEANS UNIONS FOR FARMWORKERS

By David Bacon

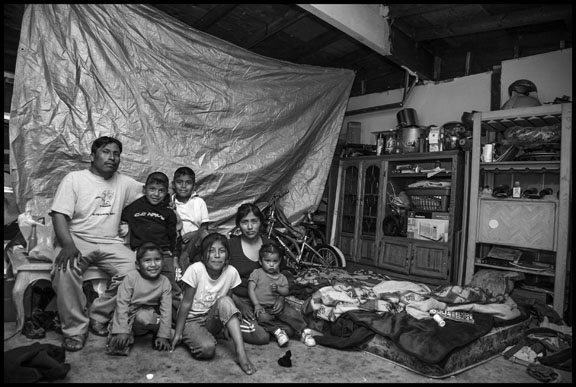

The people who labor in U.S. fields produce immense wealth, yet poverty among farmworkers is widespread and endemic. It is the most undemocratic feature of the U.S. food system. Cesar Chavez called it an irony, that despite their labor at the system’s base, farmworkers “don’t have any money or any food left for themselves.”

Enforced poverty and the racist structure of the field labor workforce go hand in hand. U.S. industrial agriculture has its roots in slavery and the brutal kidnapping of Africans, whose labor developed the plantation economy, and the subsequent semi-slave sharecropping system in the South. For over a century, especially in the West and Southwest, industrial agriculture has depended on a migrant workforce, formed from waves of Chinese, Japanese, Filipino, Mexican, South Asian, Yemeni, Puerto Rican and more recently, Central American migrants.

The dislocation of communities produces this migrant workforce, as people are forced by poverty, war and political repression to leave home to seek work and survive. Any vision for a more democratic and sustainable system must acknowledge this historic reality of poverty, forced migration and inequality, and the efforts of workers themselves to change it.

California’s Tulare County, for instance, produced $7.2 billion in fruit, nuts and vegetables in 2019, making it one of the most productive agricultural areas in the world. Yet 123,000 of Tulare’s 453,000 residents live below the poverty line. Over 32,000 county residents are farmworkers; according to the US Department of Labor the average annual income of a farmworker is between $20,000 and $24,999, less than half the median U.S. household income.

Poverty has its price. It has forced farmworkers to continue working during the COVID-19 pandemic, although they are well aware of the danger of illness and death. As the gruesome year of 2020 came to an end, Tulare County, where the United Farm Workers was born in the 1965 grape strike, had 34,479 COVID-19 cases, and 406 people had died. That gave it infection and death rates more than twice that of urban San Francisco, or Silicon Valley’s Santa Clara County. COVID rates follow income. Median family annual income in San Francisco is $112,249 and in Santa Clara it’s $124,055. Half of Tulare County families, almost all farmworkers, earn less than its median $49,687.

Democratizing the food system starts with acknowledging this disparity and seeking the means to end it. And in fact, the broader working class of California has concrete reasons for supporting farmworkers. COVID and future epidemics, for instance, do not stay neatly confined to poor rural barrios, but spread. Pesticides that poison farmworkers remain on fruit and vegetables that show up in supermarkets and dinner tables. Labor contractors and temporary jobs were features of farmworker life long before precarious employment spread to high tech and became the bane of UBER drivers.

The rural legacy of economic exploitation and racial inequality was challenged most successfully in 1965, when the grape strike began first in Coachella, and then spread to Delano. It was a product of decades of worker organizing and earlier farm worker strikes, and took place the year after civil rights and labor activists forced Congress to repeal Public Law 78 and end the bracero contract labor program.

The grape strike was a fundamental democratic movement, started by rank-and-file Filipino and Mexican workers. Although some couldn’t read or write, they were politically sophisticated, had a good understanding of their situation, and chose their action carefully. Growers had pitted Mexicans and Filipinos against each other for decades. When Filipinos acted first by going on strike, and then asked the Mexican workers, a much larger part of the workforce, to join them, they believed that workers’ common interest could overcome those divisions. Their multi-racial unity was a precondition for winning democracy in the fields.

Philip Veracruz, a Filipino grape picker who became a vice-president of the UFW, wrote during the strike’s fourth year: “The Filipino decision of the great Delano grape strike delivered the initial spark to explode the most brilliant incendiary bomb for social and political changes in U.S. rural life.”

The strike’s impact was enormous. Fifteen years after it started, farmworkers achieved the highest standard of living they’ve had in the years before or since. In the union contracts negotiated in the late 1970s the base wage was 2.5 to 3 times the minimum wage of the time, the equivalent in California of what would be $37-45 per hour today. The worst pesticides were banned, and for a decade union hiring halls kept labor contractors out of the fields.

By striking, farmworkers in 1965 were demanding the democratization of the food system. Winning the first and most basic step – a union contract – required overcoming the division between rural and urban people. Workers left the fields, traveled across the country, recruited allies, and stood in front of stores in the cities, appealing to consumers not to buy the struck grapes. Of all the achievements of the farmworkers’ movement, its most powerful and longest enduring was the boycott. It leveled the playing field in the fight with agricultural corporations over the right to form a union, and led to the most powerful and important alliance between unions and communities in modern labor history.

Farm worker strikes have traditionally been broken by strikebreakers, and all too often, drowned in blood and violence. No country has done more than the U.S. to enshrine the right of employers to break strikes. From their first picket lines in Delano, members of the new union, the United Farm Workers, watched in anger as growers brought in crews of strikebreakers to take their jobs. The boycott couldn’t end the violence, but after farm workers crossed the enormous gulf between the fields and the big cities, they didn’t have to fight by themselves.

The boycott was a participatory, democratizing strategy, and since then it has become a powerful tool for community-based union organizing. Today alliances between unions and communities are a bedrock of progressive activism. Farmworker strikes and boycotts helped develop this strategy, and gave the UFW its character as a social movement.

In 2013 farmworkers used that experience when they went on strike against the Sakuma Brothers blueberry farm in Burlington, Washington. For four years they combined strikes in the fields with a boycott of Sakuma’s main client, Driscoll’s, the world’s largest berry distributor. Their campaign succeeded in winning a union contract, and developed new ways to fight for rural democracy.

Since the mid-1980s a growing part of the migrant flow into U.S. fields has come from the states of southern Mexico, especially the indigenous Mixtec, Triqui and other communities of Oaxaca and the most remote parts of Mexico’s countryside. Migrants speaking the languages of these towns formed a new union in the heat of the Sakuma strike, Familias Unidas por la Justicia. Their fight for higher wages was closely bound to the right to speak Mixteco and Triqui, and to develop indigenous culture in rural Washington state towns two thousand miles from their home villages. Their struggle for cultural rights expanded the meaning of rural democracy.

The strike at Sakuma Farms started when the company made obvious its intention to replace its existing workers with a new set of migrants, recruited in Mexico and brought to the U.S. in the H2-A visa program. The union fought successfully for the rights and jobs of Sakuma’s existing employees, the Mixteco and Triqui farmworkers already living and working in the U.S. But in the years that followed their union also became the primary source of support for H2-A workers themselves, when they protested about abusive conditions.

Familias Unidas organizers came to the defense of workers at one company, who were fired and forced to leave the U.S. after protesting the death of an H2-A worker, Honesto Silva. They helped guestworkers on other farms protest exhausting production quotas. And when H2-A workers began to get sick and die after contracting the coronavirus in their crowded living quarters, Familias Unidas por la Justicia sued the state over grower-friendly regulations that allowed the virus to spread.

Sakuma Farms workers discovered in the course of their strike that the U.S. food system is a transborder system. In 2015 a similar strike movement began in Baja California, among the strawberry pickers at Driscoll’s and other growers in the San Quintin Valley. Workers there come from the same towns in Oaxaca, even the same families, as the strikers in Washington State. Both groups found that challenging the big growers, and winning the right to a voice over working and living conditions, ultimately means cooperation and solidarity across the U.S./Mexico border.

The largest agricultural employers have responded to demands by workers for economic and racial democracy by proposals to expand the H2-A contract labor system, criticized for being “close to slavery.” The largest recruiters of H-2A workers have enormous influence over immigration policy. With no limits on the number of visas issued annually, their recruitment of workers has mushroomed from 10,000 in 1992 to over 250,000 in 2020 – a tenth of the U.S. agricultural workforce.

Their principal proposal in Congress today is the Farm Workforce Modernization Act. It sets up the conditions for enormous growth in the H2-A program, and would likely lead to half the farm labor workforce in the U.S. laboring under H2-A visas within a few years. The bill will prohibit undocumented workers from working in agriculture, while implementing a restrictive and complex process in which some undocumented farmworkers could apply for legal status.

Instead of competing for domestic workers by raising wages, growers seek a supply of H2-A workers whose wages stay only slightly above the legal minimum. This system then places workers with H-2A visas into competition with a domestic labor force, depressing the wages of all farmworkers. As the program grows, domestic workers have to compete with growers for housing, and rents rise. When guest workers are pressured to speed up their work, an exhausting work pace spreads to the other farmworkers around them.

For farmworkers trying to organize and change conditions, the H2-A program creates enormous obstacles. When H-2A workers themselves try to change exploitative conditions, employers can terminate their employment and end their legal visa status, in effect deporting them. Workers are then legally blacklisted, preventing their recruitment to work in future seasons. Farmworkers living in the U.S., thinking about organizing or going on strike, have to consider the risk of being replaced.

Growers threaten that if wages rise, consumers will have to pay much higher prices for food. Yet a woman picking strawberries in a California field gets less than 20¢ for each plastic clamshell box, which sells in the supermarket for $3-4. Doubling her wage would hardly change the price in the store. Yet the food system is built on her poverty, and growers’ efforts to build a labor force of temporary workers cements that poverty into place.

Democracy in the fields is based on the idea that farmworkers belong to organic communities – that they are not just individuals without family or community, whose labor must be made available at a price growers want to pay. When Familias Unidas por la Justicia set up a coop to grow blueberries, Tierra y Libertad, it sought to create instead a new basis for community, a system in which workers could make the basic decisions as a community – about what to grow, how land should be used, and how to share the work without exploitation.

Rosalinda Guillen, the daughter of a farmworker family and founder of Communty2Community, the main support base for the strikers at Sakuma Farms, believes that a democratic system for food production can’t be achieved if farmworkers continue to be landless. “The value of what we bring to a community is blatantly waved aside,” she charges. “We’re invisible. Our contributions are invisible. That’s part of the capitalist culture in this country. We are like the dregs of slavery in this country. They’re holding onto that slave mentality to try to get value from the cheapest labor they can get. If they keep us landless, if we do not have the opportunity to root ourselves into the communities in the way we want, then it’s easy to get more value out of us with less investment in us. It’s as blunt as that.”

Organizing a union doesn’t give farmworkers land, and Guillen cautions that its goals are more immediate and limited. ” It’s not enough to say we’ve got X number of union contracts,” she say. “Those workers are still in a fight. They’re fighting everyday for their existence.”

But getting land and reorganizing production requires political power, just as raising wages does. And the food monopolies controlling land and production won’t give up their power without a fight. Unions for farmworkers, therefore, are the first, most basic step to power. Democratizing the food system without the organized power of the workers within it will remain just a dream.

All photographs and copyright: David Bacon

…

The Biggest Bust Ever: Direct Action Lessons From Three Days in May of 1971

By Steve Early

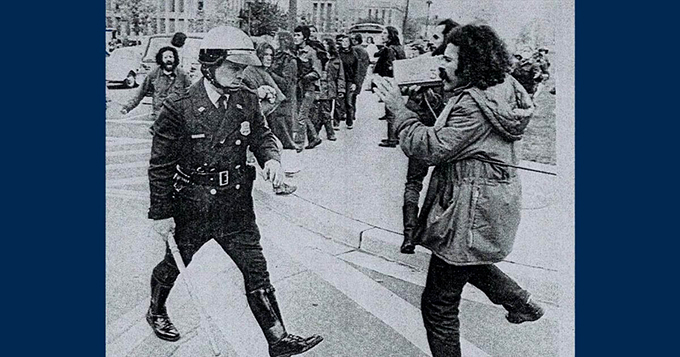

Fifty years ago this May, when the U.S. Capitol police were better at arresting large numbers of white trespassers, I watched 1,200 of my fellow anti-war demonstrators carted off to jail for just sitting on the back steps of the Capitol and listening to speeches from two House members.

That bust was the last gasp of three days of mass protest activity, in Washington, D.C. over the Vietnam War. It resulted in the largest number of civil disobedience-related detentions in U.S. history—12,000 in all, including a record-breaking single-day total of 7,000 people arrested on May 3, 1971.

To conduct this unprecedented round-up—later found to be unlawful—President Richard Nixon deployed far more law enforcement and military personnel than the Trump Administration used, in the same city, last year. Organizers of the May, 1971 anti-war actions had publicly announced their intention to shut-down the nation’s capital–by blocking its streets, bridges, and buildings. But that plan was thwarted by nearly 20,000 local, state, and federal police officers, National Guard members, U.S. Marines, paratroopers from the Army’s 82nd Airborne Division, and the Sixth Armored Cavalry from Fort Meade in Maryland.

Last June, President Trump’s threatened response to Black Lives Matter protests in triggered a major debate about the appropriateness of deploying such active-duty military personnel against civilians, in DC or anywhere else. Push back from the military itself—and members of Congress– helped stay the hand of the Nixon fan then occupying the White House.

Meanwhile, intentional law-breaking— by police brutality protestors in some cities last summer and Trump supporters on January 6—was much condemned in the mainstream media. That problematic equivalency aside, the question of how and when to organize mass protests, that are militant and disruptive, while remaining as peaceful as possible, remains a challenge the left should not ignore—if only to avoid alienating potential supporters or community members adversely impacted.

Several excellent studies of the Mayday protests, including L.A. Kauffman’s Direct Action (Verso, 2017) and Lawrence Roberts’ MayDay, 1971 (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2020), are worth consulting about these questions, on the fiftieth anniversary of the biggest bust ever. As Kauffman argues, Mayday “influenced grassroots activism for decades to come, laying the groundwork for a new kind of radicalism: decentralized, ideologically diverse, and propelled by direct action.” According to Roberts, the Nixon Administration’s response led to “consequential changes to American law and politics, including the rules governing protests in the nation’s capital, which remain in force today.”

A Grand Finale

In the Spring of 1971, Mayday was the grand finale of anti-war actions that included the bombing of a Capitol Building restroom by the Weather Underground; an occupation of the Capitol Mall by Vietnam Veterans Against the War, and a mass rally in April organized by the National Peace Action Coalition (NPAC), which drew 500,000 people. This last event was similar to the huge peace demonstrations held in Washington, D.C. on weekends during the Spring of 1970 and the Fall of 1969. Each involved bussing in large crowds of people, doing a little marching around, listening to speeches and music, and then getting back on the busses to go home. For some in the anti-war movement, this familiar routine—what one critic called “dull ceremonies of dissent” — began to feel futile and too easily ignored by the Nixon Administration.

The late Rennie Davis, the mastermind and maestro of May Day, had a different idea. Tens of thousands of activists would come to Washington ready to camp out and disrupt business as usual, on a weekday when thousands of federal workers were trying to get to their jobs. As viewers of Aaron Sorkin’s flawed film about ‘The Chicago Seven” know well, Davis was no stranger to confrontational protest. A leader of Students for a Democratic Society at Oberlin College, he helped organize anti-war demonstrations at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago in 1968. This made him a defendant in the most famous political trial of the era, resulting in a 1970 conviction for incitement to riot (that was later overturned on appeal).

Davis was still facing a five-year jail term for his Chicago Seven role when he courageously hit the road to convince campus activists that if “the government won’t stop the war, the people will stop the government.” As one old SDS comrade told the New York Times when Davis died, at age 80 in February, Rennie’s style of organizing involved a lot of “smoke and mirrors.” He believed in “political salesmanship, creating a kind of myth that wasn’t quite a lie but created an image of possibility, even if it wasn’t yet true.”

The game plan developed by Davis wasn’t an easy sell among traditional practitioners of civil disobedience or NPAC. Pacifist foes of the Vietnam war tended to play by strict non-violent protest rules; if you broke the law by blocking a federal building or burning draft board records, you didn’t try to evade arrest afterwards, for either misdemeanors or felonies. You sat (or laid down) and waited to be hand-cuffed and hauled away. NPAC leaders, following the Socialist Worker Party line, didn’t favor getting busted at all. They believed that the broadest possible anti-war movement could only be built through continued reliance on massive protests, that remained peaceful and legal. “When people state they are purposely and illegally attempting to disrupt the government…they isolate themselves from the masses of American people,” argued The Militant, an SWP publication.

Affinity Groups

Ignoring such counsel, Davis and fellow members of the May Day Collective, envisioned widespread mobile civil disobedience. Protestors would come to Washington as part of small, home-grown “affinity groups” ready to disrupt and run, not damaging property or harming people but definitely trying to paralyze commuter traffic entering the District of Columbia on Monday, May 3, 1971. The staging area for this affront to public order was originally going to be Rock Creek Park. But, after negotiations with city officials, our short-lived official camping site became West Potomac Park, near the Lincoln Memorial. On May Day itself, Saturday, May 1, 50,000 people gathered there to hear a rock concert and last-minute pep talks. Among the bands playing that night were the Beach Boys, who insisted on being the opening act so, as co-founder Mike Love explained, they could leave “before any riots broke out.” Before we emerged groggy from our tents the next morning, several thousand DC police officers had surrounded the encampment and ordered its dispersal.

To avoid any premature confrontation, almost the entire crowd packed up, and left — seeking shelter in college dormitories, church basements, private homes or apartments throughout the city. By Monday, May 3, our numbers were greatly reduced but, by most estimates, still more than 25,000 strong. By mid-morning, few demonstrators had found their way to locations originally assigned to them in the “tactical manual” developed for the protest. But that didn’t matter because President Richard Nixon had stubbornly refused to give all federal employees the day off, to avoid rush hour traffic snarls. As protestors roamed downtown DC, dodging huge tear gas barrages, they created small barricades, left disabled cars in roadways, or temporarily blocked intersections with mobile sit-ins. As Roberts observes,

“The tactical advantage underpinning Mayday was now apparent, the asymmetrical warfare of a guerilla force against a standing army. It was nearly impossible to defend against small decentralized bands who could shift on a dime, tie up police or troops at one spot, and then get to another place before the authorities could adjust…”

One adjustment the authorities did make created a legal nightmare for them. DC Police Chief Jerry Wilson suspended the use of field arrest forms and accompanying Polaroid picture-taking that linked particular officers to individual arrestees. As a result, on May 3, nearly 7,000 people were detained, but with almost no information about who they were, what they had done, or who had arrested them. In addition to not being able to easily prosecute anyone nabbed in this fashion, the city quickly ran out of places to hold everyone. During my own 48-hours of detention, I never saw the inside of a jail cell, which was fortunate because they were dangerously overcrowded. Along with fellow detainees from Vermont, I was first transported, via paddy wagon, to the exercise yard of the DC city jail. Then several thousand of us were moved to the old DC Coliseum, an indoor sports arena, where members of the National Guard, bored but friendly, kept watch.

Conditions were not great but a lot better than protestors experienced, penned up over-night, in an outdoor practice field next to RFK Stadium. There, sympathetic members of the local African-American community showed up with much needed donations of food, water, and blankets that were passed over the chain link fence to detainees who were almost entirely white. One organizer of that relief caravan, civil rights activist Mary Treadwell, informed the press that she was there because anything that “can upset the oppressive machinery of government will help black people.”

Jamming the Jails

Even critics of our attempted disruption of the city—and there were many in politics and the press– soon expressed concern about the circumstances of our confinement and related militarization of the city. The use of mass preventive detention–which resulted in some non-protestors (including reporters) being swept off the street as well — paralyzed the local jail and court system. Creating that kind of crisis was very much in the tradition of free speech fights waged by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) a century ago or the civil rights protests which filled southern jails in the 1960s. In both situations, orchestrated mass arrests were used as a pressure tactic against local authorities interfering with the exercise of constitutional rights.

As word spread that our legal defense team was trying to persuade a federal judge to order an unconditional release, many detainees in the Coliseum spurned tempting offers to be finger-printed and released on $10 bonds. In the meantime, 5,000 fellow protestors, who had eluded the first day round up, descended on the Justice Department and Capitol Building on May 4 and 5, respectively. There, they sat down and got arrested in more traditional fashion. Among those hauled away was John Froines, one of two Chicago Seven defendants acquitted in that case, but now, along with Davis and Abbie Hoffman, indicted for conspiracy again, as a planner of Mayday.

In MayDay 1971, Lawrence Roberts, who became an award-winning journalist after being a detainee himself, provides a detailed account of the subsequent litigation, which continued for sixteen years. Only a handful of people were ever convicted of anything. The charges against everyone else were dropped, including the federal indictments of Davis, Froines, and Hoffman for conspiracy. “Over the years,” Roberts writes, “thanks to class action cases filed by the ACLU, as well as individual lawsuits, judges and juries awarded millions of dollars to thousands of detainees, for violations of their right to free speech, assembly, and due process…Congress acknowledged, in a backhand way, that the fault lay as much with the federal government as the police; it appropriated more than $3 million for the city to help defray the costs of settlements and damages.” In one jury trial, the plaintiffs initially won $12 million in damages, an amount later reduced on appeal.

As Roberts notes, key players in the suppression of Mayday ended up spending more time in jail, for more serious offenses, than anybody who blocked traffic to end the war in Vietnam. That’s because, 13 months later, Nixon administration operatives were caught burglarizing and bugging the Democratic National Committee, which had offices in a DC neighborhood where much Mayday skirmishing happened. The resulting Watergate scandal ended with Richard Nixon facing impeachment and forced to resign from the presidency in 1974. Among his various co-conspirators were Mayday crackdown architects like White House counsel John Dean, Nixon’s chief of staff H.R. Haldeman; his top domestic policy advisor John Ehrlichman; Attorney General John Mitchell; Assistant AG Richard Kleindienst, and White House staffer Egil Krogh. A future Supreme Court chief justice, named William Rehnquist, provided a Justice Department memo assuring Nixon that he had “inherent constitutional authority to use federal troops to ensure that Mayday demonstrations do not prevent federal employees from…carrying out their assigned government functions.”

It was the kind of green light that Donald Trump sought, but never quite got last June, when deploying the military against protestors in Washington, D.C. became a White House strategy again.

…

Taking a stand in Massachusetts: Gig economy workers are employees, not independent contractors

By Peter Olney and Rand Wilson

On Saturday, May 1st at 10:45 AM (PT), Rand Wilson and Peter Olney took part in the panel “Organizing Workers in the Gig Economy”. Watch the recorded discussion HERE

Of course, after winning in California, we knew they wouldn’t stop there. Their big win on Proposition 22 last November has emboldened Uber, Lyft, and the whole constellation of gig economy companies to undermine employment standards and workers’ rights in other states.[1]

The hyper exploitation of ride share drivers by Uber and Lyft and other gig companies is premised on using a cell phone application (or “app”) to enlist workers as drivers or delivery workers. The companies claim that the drivers are not their employees but instead are independent contractors. With this reasoning, management is not obligated to comply with wage and hour laws, or pay into workers’ compensation, unemployment, and state disability insurance funds. And by classifying their employees as independent contractors, drivers do not have access to federal protections from discrimination or collective bargaining and other worker rights under the National Labor Relations Act.[2]

The gig economy companies mobilized after a 2018 California State Supreme Court decision, “Dynamex,” ruled that a simple “ABC test” should be applied to determine whether an individual is an employee or a contractor. California codified that decision when it enacted Assembly Bill 5 (AB 5) in September 2019 and tightened the criteria for worker classification.[3]

Under the ABC test, a worker is considered an employee and not an independent contractor, unless the hiring entity satisfies all three of the following conditions:

- The worker is free from the control and direction of the hiring entity in connection with the performance of the work, both under the contract for the performance of the work and in fact;

- The worker performs work that is outside the usual course of the hiring entity’s business; and

- The worker is customarily engaged in an independently established trade, occupation, or business of the same nature as that involved in the work performed.[4]

The Dynamex decision and California’s AB 5 law fundamentally threatened the rideshare companies’ business model. The companies responded with a ballot initiative, Proposition 22, to pass a law carving out rideshare drivers from AB 5’s regulations.

Uber, Lyft, and DoorDash claimed that if their ballot initiative passed drivers would receive guaranteed pay equal to 120% of the minimum wage plus 30 cents per mile to cover expenses, as well as access to health insurance. However, after considering multiple loopholes in the initiative, a research study estimated that the promised pay guarantee for Uber and Lyft drivers is actually equivalent to a wage of only $5.64 per hour.[5]

Rideshare Drivers United (RDU),[6] a grass roots organization of Uber and Lyft drivers based in Southern California, campaigned valiantly against Proposition 22. RDU was joined by the California Labor Federation and its affiliates in officially opposing Prop 22.[7] But they were outgunned, out messaged, and outspent $205 million to $14 million.[8] The unions decided not to canvass voters at their doors during the pandemic –surrendering their most powerful weapon: an organized ground game.

The pro Prop 22 forces developed a slick media campaign that showcased immigrants and people of color at the wheel of their cars talking about their desire for “flexibility” and the great benefits of driving for Uber or Lyft. The meager anti Prop 22 budget could not come close to matching the media campaign and the lack of a door-knocking program meant the corporations carried the day, winning 58.63% to 41.37%.[9]

While the gig companies are looking at campaigns in Colorado, Illinois, and New Jersey, Massachusetts appears to be where the next high profile battleground will take place.[10] Uber and Lyft have created a “grass-tops” coalition, the Massachusetts Coalition for Independent Work,[11] to push several bills in the state legislature that would undo the state’s ABC test.[12] Most observers believe their bills will die in committee on Beacon Hill. However, like California, Uber and Lyft will likely resort to placing a referendum question similar to Prop 22 on the state ballot in November 2022.

The definitive margin for Prop 22 in California shows just how hard it will be to win in Massachusetts. And we know in advance that the campaign to preserve the ABC classification test will be heavily outspent by the gig industry. However, a smaller media market, the 2022 governor’s race, other ballot initiatives, and the lessons of California may help equal the playing field. There are four keys to a different outcome in Massachusetts:

- Doors, doors, doors – Pandemic or no pandemic the campaign needs to mask up, stay socially distant, but knock on voters’ doors;

- California dreaming? – Immediately after the passage of Prop 22 the gig companies in California began slicing promises they made to drivers for health insurance and higher income. And in the wake of Prop 22, other companies like Albertsons and Vons began to take advantage of the law by firing their employees and hiring DoorDash to make deliveries. The campaign must be about all workers, not just drivers.

- Powerful pathos – The motives and consequences of gig employment must be exposed! Hundreds of gig drivers will need to be recruited and trained to tell their stories contradicting the paid media narrative.

- Unity and solidarity – the campaign must be about uniting working people against powerful corporations and the greed behind their initiative. We will need many heartrending stories of employees denied their FLSA protections and employee rights because of misclassification.

The simultaneous 2022 ballot to amend the state constitution allowing a special tax on millionaires and a hotly contested race for governor will also create a grassroots advantage. Combined these campaigns should yield a very large progressive turnout. However, it remains to be seen if suburban liberals and the intelligentsia that has historically been snowed by the “new economy” discourse will be open to a critique of the false promises of the gig economy.

On the one hand, we saw how liberal Democrats folded when the hospital industry spent $25 million to defeat the nurses’ union ballot for staffing ratios in 2018.[13] On the other hand, a proposal to expand charter schools backed by a $26 million campaign was soundly defeated in 2016.[14] Let’s be optimistic, if Robert Reich can go from being a pro NAFTA and new economy guru as Secretary of Labor to a staunch defender of worker rights, then there is hope that liberal opinion leaders and state elected leaders will be on our side.

Stopping Uber and Lyft cold in Massachusetts would be of enormous significance nationally. A defeat for the ride share driver companies could propel broad federal legislation making worker mis-classification much harder and undoing toxic state measures like Proposition 22 in California. Imagine a Bay State banner that reads, “Yes Uber and Lyft: Blame me, I’m from Massachusetts!”

…

Watch the recorded discussion here

[1] “2020 California Proposition 22,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2020_California_Proposition_22, “California Proposition 22, App-Based Drivers as Contractors and Labor Policies Initiative,” https://ballotpedia.org/California_Proposition_22,_App-Based_Drivers_as_Contractors_and_Labor_Policies_Initiative_(2020)

[2] “Uber Was Designed to Exploit Drivers,” Ankita Rao, Vice, https://www.vice.com/en/article/3k3kdn/uber-was-designed-to-exploit-drivers

[3] https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billTextClient.xhtml?bill_id=201920200AB5

[4] “Independent contractor versus employee,” State of California, Dept. of Industrial Relations, https://www.dir.ca.gov/dlse/faq_independentcontractor.htm

[5] “The Uber/Lyft Ballot Initiative Guarantees only $5.64 an Hour,” Ken Jacobs and Michael Reich, October 31, 2019, https://laborcenter.berkeley.edu/the-uber-lyft-ballot-initiative-guarantees-only-5-64-an-hour-2/

[6] https://www.drivers-united.org/

[7] “NO ON PROP 22 FACT SHEET, California Labor Federation, “https://calaborfed.org/no-on-prop-22-faq/

[8] “Uber And Lyft Spent Hundreds Of Millions To Win Their Fight Over Workers’ Rights. It Worked.” Caroline O’Donovan, BuzzFeed, November 21, 2020, https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/carolineodonovan/uber-lyft-proposition-22-workers-rights

[9] “2020 California Proposition 22,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2020_California_Proposition_22

[10] “The Gig Economy Is Coming for Millions of American Jobs,” by Josh Eidelson, Bloomberg, February 17, 2021, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2021-02-17/gig-economy-coming-for-millions-of-u-s-jobs-after-california-s-uber-lyft-vote

[11] In a January 28 email to community and religious groups, it stated, “The coalition’s goal is to help develop a modern legislative framework that can protect workers’ ability to choose their schedules and earn income on their terms, while also gaining benefits and protections. Overall, the coalition aims to expand opportunities for workers across all demographics, ethnicities, and backgrounds; strengthen transportation and delivery equity that helps all communities grow and thrive; help brick-and-mortar small businesses, restaurants, and retailers compete in an increasingly online economy; and protect those communities that rely on independent workers and app-based services for their essential needs.”

[12] House Docket 2901, “An Act relative to the definition of an independent contractor,” and House Docket 2904, “An Act relative to independent contractors.”

[13] “Hospitals spend record $25M to defeat nurse patient ratio ballot question,” By Jessica Bartlett – Reporter, Boston Business Journal, Feb 25, 2019, https://www.bizjournals.com/boston/news/2019/02/25/hospitals-spend-record-25m-to-defeat-nurse-patient.html

[14] “Massachusetts votes against expanding charter schools, saying no to Question 2,” by Shira Schoenberg, Jan 07, 2019, MassLive, https://www.masslive.com/politics/2016/11/massachusetts_votes_against_ex.html

“The Wandering Habit” — Two Cheers For Nomadland

By Hardy Green

She called them “the suitcase crowd.”

It was while working as a secretary in the Memphis public schools, beginning in the 1960s, that my mother became acquainted with a frequently moving slice of humanity.

One of her duties at the school was to register incoming students, particularly those who appeared not on the first day of school but later, in the middle of a term perhaps. Some of these late-arriving students might show up in mid-November and then one day disappear, only to reappear sometime in the spring. Generally, they resided for a period at a nearby public housing project. What caused them to come and go? Probably their parents’ uncertain employment, perhaps talk of opportunity elsewhere combined with what some historians of southern textile-mill villages have termed “the wandering habit”—a tendency of formerly rural people to pick up at a moment’s notice and move away.

When I first heard about the film Nomadland, I thought it must concern “the suitcase crowd.” And maybe that’s right: The availability or unavailability of work does induce Fern—the character played by actress Frances McDormand—and her chums to move about. But Fern’s group seems a little less down-and-out—and a little more Age of Aquarius-inspired—than I recall my mother’s “suitcase crowd” as being.

As the movie awards season approaches its climax with the late-April Academy Awards, we’ll be hearing more and more about Nomadland. And that gives me pause. There’s lots to like about the picturesque, often touching film—and certain things to question, particularly the very positive image of work at Amazon.

What first prompts Fern’s roaming is the 2011 closure of U.S. Gypsum’s mine and sheetrock factory at the company town of Empire, Nevada, where her husband had worked. Employees and their families were permitted to continue living in their company-owned homes for only five months after the closure. Then, Empire became a ghost town and even its zip code gotdiscontinued.

Thereafter, we see Fern taking on various stints of work and long drives in her camper van. She has gigs at an Amazon warehouse, at a national park, and at a beet processing plant. She wanders around Badlands National Park in South Dakota and, in deepest winter, hangs out with other migrant van dwellers at the real-life Rubber Tramp Rendezvous at Quartzsite, Arizona, which every year draws thousands of attendees.

The movie was inspired by a book of the same name by journalist Jessica Bruder. That account covered five years and interviews with some 50 aging post-recession refugees from the middle class and working class. They include a former long-haul truck driver and taxi drivers, McDonald’s and software company executives, an IRS phone representative, and a chain store cashier.

To call these people nomads is a misuse of the term. “The word nomad derives from the Greek nomos—a pasture,” travel writer Bruce Chatwin informs us in his essay “Nomad Invasions.” “A nomad proper is a mobile pastoralist, the owner and breeder of domesticated animals…. Nomads never roam aimlessly from place to place, as one dictionary would have it. A nomadic migration is a guided tour of animals around a predictable sequence of pastures.”

Chatwin also tells us that nomads, with their grazing animals, and farmers, with their crops, live in a symbiotic relationship, exchanging hides, meat, and dairy products for grains and vegetables. In like manner, the wanderers of Nomadland depend upon stable capitalist outposts including Amazon. But these “nomads” have no animal products to trade—only their labor power.

Perhaps coincidentally—and perhaps not—Amazon has been in other news lately due to a unionization vote at a warehouse in Bessemer, Alabama. (That’s another former company town; you really can’t get away from them in working-class America.) The union drive featured reports of denied bathroom breaks and repetitive-stress injuries due to workers’ slogging around heavy boxes for hour after hour.

In the movie, we see Fern and her co-workers performing these tasks at a similar Amazon “fulfillment” center. But the work seems far from hellish: At one point, we see McDormand casually walking a package from one area of the warehouse to another. And later when questioned about how she’s getting along economically, she reports that Amazon’s good pay is key to her survival.

Perhaps there can be a sequel in which Fran develops back trouble and can no longer endure long drives in her van. Nomadland has been praised for its use of non-professional actors including true-life itinerants. But a more true-life picture would examine just why unionization became an issue at the Bessemer warehouse. Life for “the suitcase crowd” is a long way from that of the jet set.

…

From My Backyard in Hackney – It’s all about the money

By Neil Burgess

On Sunday the 20th of April we sat in the sunshine in our garden drinking tea with a very nice young couple who are buying the house next door. London is just coming out of Covid lockdown and we’re now allowed to meet people in the open air. She’s an architect and immediately bonded with my partner of the same profession. His response that he was a lawyer, didn’t immediately seem promising, but questioned closer, it turns out that he specialises in Sports Law and not only that but he supports Liverpool FC. Well, these are going to be nice neighbours! I remember commenting that it must be great being lawyers working for the top football teams: who is going to argue over £1000 an hour fees when the top players are earning north of £200,000 a week?

Towards the end of the afternoon as they were leaving the lawyer hinted that there was a big football news story about that I might be interested in, he couldn’t tell me what, but it was about to break. Immediately they were gone I looked up on Google and found a short report suggesting a group proposing a new European Super League. Interesting? Well, yes, but it’s been talked about before and there was little detail, so I didn’t think about it again until I heard the news the next morning by which time all hell had broken loose. It was top of the national radio and TV news and headlining the front of all the newspapers and websites.

The four top teams in England and a couple of others had joined with the top teams in Spain and Italy to form a new European Super League that would be best of the best, but everyone was against it, they were going mad. Not just the fans, but the managers and the players knew nothing about it, they hadn’t been consulted. Not just the Chairmen of the other teams who hadn’t been invited. Not only the leaders of the English Football Association and the European Football Association, but the bloody Prime Minister Boris Johnston was wading in. By eleven o’ clock Monday morning Prince William expressed his displeasure, and I was waiting for the announcement from the Vatican that the Pope wasn’t happy, then we’d have the full set.

The sight of this Prime Minister accusing these clubs of greed, was, to use a very English expression gob-smacking.

To say that the kick back against this idea was ferocious is an understatement. What was all the fuss? Apparently this new league would be fixed: win or lose the founding teams would remain in it. Apparently this offended the British sense of fair play, the egalitarian, the meritocracy, the very democratic tradition, that made the Empire great…, er okay, not the last bit. So, in theory, a small team from some backwater can join a local league and by topping that league win promotion the next level of football. If they do that about seven or eight times they might join the English Premiership; election to the Premiership is the biggest cash prize in world sport, it guarantees additional income of over £130 million pounds over the following season. But of course it’s not about the money, no. Naturally, the royals, the politicians, the Chairmen of the Associations and of the lesser clubs and the journalists and the fans and their spokes-people all agreed, it’s about the very nature of sportsmanship, sorry, sportspersonship.

Bollocks. It’s all about the money. The sight of this Prime Minister accusing these clubs of greed, was, to use a very English expression gob-smacking. The previous week he’d been reported claiming that it was greed that motivated the vaccine manufacturers that had saved us from the pandemic. So that greed was good, but football’s greed is bad. Confused? Well, I am for sure. Professional football (yes, I know you guys in America call it soccer, but everywhere else it’s football. I mean, in the American variety they don’t even use a ball, it’s some sort of egg thing, someone should tell them, it’s not a ball.) is worth many billions of pounds and even more dollars. It has attracted Russian Oligarchs, Saudi and other Arab Princes and American sports Mogols, plus other more disreputable types, but all genuine football fans, who now own the entire English league. What, because they love our sense of gamesmanship? Maybe, but also the game is a huge cash cow and so badly regulated that owners can cream off large amounts of money in all sorts of imaginative ways. And what about the people who run the competitions, the World Cup, the Champions League, Series A, the Premiership? Well they’ve all got their snouts in the trough and are gobbling up their share too. This new Super League was about break the status quo and threaten their livelihoods.

Now, the break-away teams have all with-drawn from the Super League and apologised. It was all over in a matter of days. But I remain suspicious about what was really happening. If the Super League was serious, where were the PR consultants and press secretaries briefed to sell the super league idea to the fans? The promise of seeing the world’s top players and teams playing each other on a regular basis and without having to buy a yearly subscription to SKY TV or their UK competitors BT, is an attractive proposition. Why didn’t the Super League group have their considerable media teams behind the idea from the start to counter all the negative stuff? Maybe they are just stupid and hadn’t thought it through? Or maybe there is something else going on and this was just an opening skirmish? Whatever the case I can feel confident that my new neighbour is going to be kept very busy in the coming months.

…

Teacher Unions and the Struggle for Racial and Economic Justice

By Heath Madom

A recent study published in the American Journal of Political Science entitled “Labor Unions and White Racial Politics” makes a compelling case that unions reduce the racist beliefs of white workers. Drawing upon a trove of survey data, authors Paul Frymer and Jacob M. Grumbach found that union membership tends to lessen white racial resentment due to “long-term cooperative intergroup relations.” In other words, belonging to a union helps white workers form deep relationships and develop solidarity with nonwhite workers, which in turn makes them—unsurprisingly—less racist. This news was celebrated on the Left, and for good reason. In a racist and rampantly unequal society, any evidence that demonstrates the effectiveness of unions at diminishing racism while organizing the working class is welcome news indeed.

Yet as a public school teacher, my initial enthusiasm about the study soon gave way to a troubling realization: the conditions described in the study as necessary for improving racial attitudes don’t exist for most public school teachers. From a purely demographic standpoint, the teaching profession in the United States is overwhelmingly white. In the face of this reality, it is difficult to imagine the amelioratory effects described by the study actually taking place inside most public schools, which have few teachers of color. Even in Oakland, the city where I teach, where just under fifty percent of the teachers are either Black, Latinx, or Asian, making it commonplace for white teachers to work alongside teachers of color, the culture of “deeper and more cooperative” contact—which Frymer and Grumbach argue is both a common feature of unionized workplaces and a key to breaking down racial resentment—just does not exist. The lack of contact and cooperation among teachers in public schools is not due to any fault of teachers. It is, unfortunately, a feature of public schooling, and one that has serious implications for the potential of schools and teachers to advance antiracist ends.

The question of what teachers can and should do to end racism—both in our schools and society at-large—is on the mind of many educators right now. As we reflect on our pedagogy and practice, it is clear that we have to do more to make our classrooms more equitable for all our students, particularly our Black and Brown students. But as we engage in that necessary internal work, we must also set our sights on larger policy objectives. Ending racism will require collective action, and so we must also act collectively, through our unions, to push for deeper, more fundamental changes in how we relate to our students, to the communities we serve, and to one another. Many teacher unions have already endorsed initiatives like Black Lives Matter at School as well as efforts to remove police from schools, which is a promising start. Yet in this moment of potential reckoning, teacher unions have an opportunity to advance a more far-reaching vision, one that transforms the prevailing culture of schools and, more importantly, helps win economic policy change capable of remedying the racial and the economic inequality that characterizes so much of American society.

To realize this vision, we have to first understand how the current structure of schooling hampers efforts to address, and ultimately end, systemic racism.

A Lonely Profession

Teaching, as it is generally practiced in the United States, transpires in structural isolation. As David Labaree has noted, most teachers “teach under conditions where they are the only professional in the room, left to their own devices to figure out a way to manage a group of 30 students and move them through the required curriculum.” Or as one of my colleagues once ruefully described it, when you’re a teacher, you’re an “an army of one.”

While there is a certain seductiveness to the autonomy given to teachers, teaching in this manner leads to harmful outcomes. For starters, it undermines efforts by school faculty to establish common pedagogy and shared professional culture. Instead of talking to our colleagues, sharing best practices, and engaging in lesson study, we’re forced to spend most of our time hunkered down in our classrooms, desperately trying to attend to the countless number of tasks that are routinely dumped on our laps. Our daily interactions with colleagues are often limited to trading pleasantries in the hallways or commiserating over the fact that the copier has broken down yet again, even though we would much rather spend an hour at the end of each day talking, planing and reflecting with those same colleagues. Yet the unceasing demands of the job—which are the result of deliberate policy choices—work against that desire at every turn.

Even worse than the lack of collaboration is how our isolation encourages us to conceptualize teaching as an individual endeavor—what Dan Lortie notably called, “a private ordeal”; it is a task that you simply have to figure out on your own. This conception of teaching, which so many of us unwittingly accept, dampens any instinct that would push us towards deeper connections with our colleagues—the kind that Frymer and Gumbach argue dismantle racist beliefs.

This is not to say teachers never act out of shared interest; the recent surge in teacher strikesproves that educators both feel and act out of genuine solidarity. But while teachers might practice solidarity in a fight against austerity or a campaign for better learning conditions, too often we fail to acknowledge or confront our complicity in replicating a reality that, for the most part, does not benefit poor Black and Brown students. We organize ourselves against the budget cuts that come down on us like clockwork, but can we say the same about the racial inequities our classrooms churn out year after year? While these inequities are unquestionably intertwined with poverty and economic class, that doesn’t excuse us from taking action to address them.

The school to prison pipeline, one the most oft-cited examples of racial inequity in public education, is a prime example of this: Black students are routinely suspended and expelled at significantly higher rates than white students. This disproportionate discipline becomes a pathway to prison as students who are subjected to harsh school penalties face a higher likelihood of being arrested and incarcerated as an adult. And despite the progress made in places like California, which has reduced the number of suspensions and expulsions across the board, the racial disparity in discipline persists.

What’s often lost in discussions of the school to prison pipeline is the hand that sets the wheel in motion. Last summer, one of my colleagues suggested that when it comes to Black students, there’s not much difference between cops and teachers. This was in early June, at the height of the protests over the murder of George Floyd, which might explain why I initially dismissed his suggestion as utterly out of hand. How could any harm done by a teacher to a Black student ever come close to the harm done that has been done to Black people and the Black community by the racist machinery of policing and mass incarceration? The very suggestion struck me as absurd.

Some months later, I’m no longer so sure. Labaree writes that in order to “rise to [the] challenge” of teaching (i.e. survive the ordeal) many teachers “turn [their] classroom into a personal fiefdom, a little duchy complete with its own set of rules and its own local customs.” As teachers, we must face the fact that these rules and local customs of our classrooms are the tools with which Black and Brown students are disproportionately targeted and punished (something that is often true of our grading and assessment as well). And with no one there to break through our isolation and hold us accountable for our actions, or suggest that there might be a better way, one that is not instinctively punitive, these small injustices build into a greater one, even as it remains mostly invisible. Whatever personal price the private ordeal of teaching exacts, it unquestionably inflicts far greater harm on the lives of too many Black and Latinx students.

We should not, therefore, automatically assume the mere existence of teacher unions will magically erase racist beliefs, or more importantly, lead to changes in behavior that would eliminate racial inequities in our classrooms. If that were true, the school to prison pipeline and the achievement gap would have been erased a long time ago. Schools are structurally unique workplaces where the experience of isolation—not to mention decades of systematic underfunding—make it incredibly difficult to avoid replicating the racially biased outcomes rooted in the larger society. For schools to ultimately become spaces that help achieve antiracist ends, we must demand more collaboration time, change our approach to student discipline, and then, most importantly, organize our communities in a larger political struggle to achieve a more equitable distribution of economic resources.

Towards Collaborative and Restorative-Based School Cultures

Unlike most other professions, K-12 teachers do not spend much time around other adult colleagues; instead, nearly all of our time is spent with children and young adults. In and of itself, there is nothing wrong with this. The work of educating young people is important, meaningful, and deeply rewarding, and is the primary reason most teachers choose the profession in the first place. Teachers should spend most of their day working with their students.

The problem, as outlined above, is that teachers are given very little time to collaborate with other teachers. If you teach at a relatively large school, it is not uncommon to go weeks, if not months, without speaking to some of your fellow colleagues, let alone meeting with them to plan curriculum and/or experiences for students. This needs to change. We must shift the structure of the school day so teachers spend more of the school day working in teams with their colleagues on curriculum. To that end, teacher unions should prioritize winning increased prep time during the school day for teachers to engage in such collaboration, along with the corresponding resources and increased staffing to make such an arrangement possible. Giving teachers increased collaboration time would not only lead to better student outcomes, it would also help foster healthier, more collaborative school cultures where teachers feel more supported. These efforts must also be paired with a similar push to bring more teachers of color i[1] nto the profession. Breaking teachers out of their forced isolation is all well and good, but it is critical that teacher workspaces are populated with diverse and divergent voices, especially if we want to mitigate white racism in both belief and deed. For that reason, it is just as important for teacher unions to demand more funding for pathways and programs aimed at diversifying the overall teaching workforce.

Much as teachers need a more collaborative stance towards each other, we also need a less punitive approach towards our students. Without a change in our approach to discipline, one can easily imagine a diverse team of teachers collaborating harmoniously (to plan a culturally responsive curriculum no less!) and yet still perpetuate racist disciplinary practices. That is why in addition to shifting towards a more collective practice of teaching, we also have to rethink how we relate to our students.