Wildlife

By Kate Elliott

Dateline: Greater Vancouver – BC’s Lower Mainland, Canada

I begin by offering a story — a story I heard in 2019 while standing with a group of precariously housed folks in a dimly lit empty parking lot late one winter night.

We were gazing up at the sky. Someone had mentioned something about the stars — or maybe about a satellite or the space station. We’d all tilted our heads to look. A chill wind lapped at our faces, and we shuffled our boots against the asphalt to trick our feet into warmth. Unmittened fingertips held beer cans and lit cigarettes. And then a voice from among us asked if I knew about the owls, the rats, and the yoga studio.

“We used to come here at night to watch the owls,” he said. “They would perch at the edge of the roof over there, hunting rats. Beautiful birds. They’d watch the parking lot, waiting for the rats to come out. Then they’d swoop down and grab one. Plenty of rats. Good hunting for owls. But not everybody likes rats… When they renovated that building on the other side of the lot, things changed.” He pointed to a low-rise building, kitty-corner from the roof where the owls used to roost. “They put in a yoga studio, and people would drive here for classes. I suppose they didn’t like that sometimes a rat scurried by when they walked from their car to the studio. Someone must’ve complained to the building manager. Next thing you know, they’ve put down poison. Killed the rats. … No rats, no owls. They never came back.”

Several people nodded at the end of the story, and one man gestured to his dog, “Had to be careful this one didn’t get hold of any poison.” A couple murmured softly about the loss of something rare. “They wouldn’t have known about the owls,” the storyteller explained. “No way to know the poison would affect more than the rats.”

“No way to know …” The generosity of that statement has stayed with me. It forgives a lack of imagination that seems embedded in other urban solutions, such as those offered as a cure for homelessness. The same lack of imagination that killed the rats and ignored the owls is also present in one-size-fits-all municipal decisions about what “home” means to people who appear not to have one. — It is present also in decisions regarding what makes housing “adequate” for folks who have survived sleeping rough. Such decisions often ignore greater ecologies and tend to oversimplify the targeted problem.

To examine what makes a “good” solution, and who benefits, I invite you to take a closer look at the tale of the owls, the rats, and the yoga studio. What existed before a problem was identified? An urban ecosystem of sorts: a healthy colony of rats living underground — some of the houseless folks estimated the subterranean community spanned four blocks or more — and owls attracted by an abundance of prey. What played out in that space, from the perspective of the humans who gathered to watch the nocturnal hunting grounds come alive, might have been considered the stuff of nature documentaries. So, what, then, caused the problem? The arrival of a business that attracted folks who were not so local, clients who might not associate rats with owls — nor, for that matter, associate owls with parking lots in a neighbourhood of strip malls, police presence, and various social services. The assumption of the storyteller that someone connected to the yoga studio had complained about the rats, although not proven, seems plausible. The cause-and-effect timeline observed by the nature-watchers is clear: visible natural ecology playing out nightly, followed by arrival of yoga studio and its clients, followed by extermination of rats, and disappearance of owls. But through the limited gaze of the building manager and the yoga studio clients, the timeline is clipped: first there were rodents, which was deemed inappropriate, so action was requested and taken; now the rodents have disappeared. From this latter vantage point, the solution has been “good”; but from the vantage point of the locals who understood the ecology of the space, the solution has caused multiple harms. That there was no way to know the harms caused by poisoning the rats is true, but in a very limited sense: no one sought to ask, “Was there more they should know before taking action”.

And as with rats, in this case, so with humans.

A few weeks ago, a former classmate messaged me enthusiastically about renewed plans to “end homelessness” in the city. My instant emotional response was, “Whatever.” It’s not that I don’t believe in the importance of ending homelessness, I just haven’t seen it work in a way that permanently increases quality of life for the folks who become the target of these initiatives. In many cases, what I have seen and heard makes me wonder who “solving homelessness” is for: so often, it seems to merely invisibilise those without normative houses by tucking them out of sight into over-surveiled spaces that don’t ever feel like “home” — places people don’t necessarily want to be.

In the past six years, I’ve spent time in places where stories of people’s journeys into and out of homelessness — and back into homelessness — are the norm. The single common element of all the narratives I hear is that these experiences are individual; they vary depending on personality, ability and mobility, social connection, and the amount of trauma an individual has experienced. Just like housed folks, those who are houseless are not one definable demographic. But solving homelessness would be so much easier if that were not the case: if only unhoused people were a single entity with uniform needs. The stories I’ve heard bear the scars of easy solutions: housing conditions that are far from what the already-housed population would accept, and that few homeless folks would describe as “home.”

“Tenting is a desirable adventure for the already-housed.”

A few years ago, as a “tent city” was about to be taken down, I watched on my television screen while a reporter asked a woman in the camp if she didn’t want housing. All the viewers would have understood the dominant message that a tent is not appropriate housing. We also all understood the framing of this problem: those staying in the camp were refusing some sort of normative shelter being offered. This seemed to baffle and frustrate officials making the offer of housing. The woman answered the journalist without hesitation, “Of course I want housing.” And she told the reporter that she wanted her (the reporter’s) housing, explaining that if she couldn’t live in conditions similar to those that already-housed folks had, she’d rather live in her tent, where she had at least some control over her environment. That response is what I had already heard from others, and what I continue to hear from folks who feel that what they are being offered is sub-standard. But this lack of willingness to accept a living space with gyprock or concrete walls instead of the fabric walls of a tent flummoxes municipalities and those who have always had normative housing. Why would anyone turn down an opportunity to come in from the outdoors, to get out of a tent? — After all, although one outdoor adventure advertisement for my province boasts “50 free campsites” and pictures a tent pitched in a beautiful clearing, camping is reserved for leisure, for those who can afford to fit nature-time into the vacations doled out by their employer. Tenting is a desirable adventure for the already-housed. Folks who pitch a tent for free in urban spaces are an eyesore and an uncomfortable reminder that the rights to the city are inequitably distributed. So, when more normative housing is offered and then rejected, this can be confusing to those extending such offers. It might even seem like ingratitude. In an effort to understand refusals of housing, some people have decided that the lack of comprehension lies with those who are houseless. I’ve heard stories of houseless folks being advised to come put their name on the list for temporary modular housing (TMH) when they “come to their senses.” There is a strong fibre of paternalism running through these stories: that if unhoused folks simply understood what was good for them, they would accept what was on offer.

“When you don’t have a lot of money, there’s a fine line between housing and prison”

Theo, who made his living through scavenging and informal recycling, slept rough and pushed his belongings in a grocery cart. He had resisted different forms of housing on offer after discovering restrictions that he just didn’t want to live with. If he was going to move indoors, he told me, he wanted to know he would be comfortable; if not, it just wasn’t worth it. In 2019, during weeks of sleet, he reconsidered and went to see what the proposed TMH development in his neighbourhood might be like. He spoke with me the day after he’d gone to put his name on the list. He was angry. Apparently, before he’d had much of a chance to ask about regulations and restrictions, the woman in charge had nodded toward his grocery cart. “She told me to come back when I’d downsized my belongings! I was sure steamed. Told her to go back to her home and downsize her own belongings. How did that feel?” Johnny, with whom I’d been on many scavenging trips, lost his housing through renoviction in 2019. Although looking for housing, he wanted a place he’d be comfortable, and didn’t want to have to sign in and out when leaving a place where he lived. “That’s not home,” he grumbled to me one day. He lived rough for a year before a place he could live in became available.

Kyle, too, had been homeless for long stretches of time. “When you don’t have a lot of money, there’s a fine line between housing and prison,” he told me. He was especially wary of the TMH units that Theo had investigated. “They’re not all the same,” he said, admitting that some TMH projects are better than others, both in design and level of surveillance. “Run by different folks. But it’s like their name: they’re “temporary.” If you give in the first time and say, ‘Okay, I’ll sign in when I want to go home, and I’ll sign out when I want to leave my home, and I’ll accept that maybe I have to have room inspections, and that maybe I don’t have a kitchen in my home and I can’t have guests spend the night — or maybe I can but only a couple of nights a month and they have to be the right kind of people, well, okay then. — If I accept those rules for my ‘home,’ okay. But then the modulars get shut down. — They’re only temporary, right? — And they’re going to move you to new housing. But maybe this new housing comes with even more rules. What are you going to do? It’s a slippery slope. Say yes now and one day find yourself living in a prison.” He described some residents as “sleepwalkers.” “You have to be,” he told me, “to accept those conditions.”

But not everyone feels that way. TMH can become home space for some who need it, and some TMH is designed with fully-contained units that do have kitchen spaces and private bathrooms. But it is temporary. Other housing, like SROs and temporary shelter living requires a sharing that can be difficult for people coming out of abuse. Several women I’ve spoken with have likened the mere experience of being homeless to an assault. “I thought to myself, ‘This is not my life. This is not my life.’ I woke up every morning and wondered how I got here. I grew up in a nice neighbourhood,” one woman told me. When she arrived at the shelter with her small child, she found it difficult to parent in public, to find alone time. “I just needed a space to myself. But there’s no privacy in these places. — I’m not ungrateful, but you just need a space to yourself. And there isn’t one.” When she had taken a few minutes to sit quietly, another woman had made an official complaint that she was neglecting her child. “I mean, how can you be a good mother if you don’t have time to take care of your own needs?” I was surprised to hear there was little support.

Ryder, an informal recycler I worked alongside during my thesis research, told me women always have a hard time. “You can’t win if you’re a mom without a home. People always look at you as if you’re a bad parent. If you give up your children to the system, you’re a bad mom, but if you try to keep them and you don’t have good housing, you’re a worse mom.” Women told me how hard it was to find housing that is deemed appropriate, especially if they have children over the age of five: according to the Canadian National Occupancy Standard (CNOS) male and female children are not to share a room. It’s possible that many families don’t know this: those of us who have always been housed are able to configure our home spaces however we like. But I’ve heard from women who are deeply concerned that breaking CNOS guidelines may put at risk their housing funding or ability to live with their children. That means finding affordable apartments with multiple rooms, a financial impossibility in British Columbia’s lower mainland. And fathers suffer, too: one of Ryder’s friends had been separated from his children and their mother because most shelter housing is not intended for families. Gender-segregated shelter space means that children stay with mothers, and fathers live apart, meeting up when they can. For families already juggling the stressors associated with precarious living (precarious employment, food insecurity, moving children to different schools, surveillance from social services, the endless bureaucracy of paperwork required to access essential services), segregated shelters place extra burdens on relationships.

In order to save their relationships, even childless couples will sometimes reject sheltered housing in order to remain together. “We’re the only thing we have,” one woman told me. “Each other. That’s it. If it’s the street or separation, I choose him.” She and her partner had lived rough for almost ten years by the time they found space in a shelter that allowed couples. I heard a similar story from a woman in her 60s who felt her husband needed a level of care that simply wasn’t offered in a shelter. She chose to live with him in a tent, packing up daily and looking for “safe spots” to spend the night along the urban periphery. “It’s important to be invisible,” she told me. “That’s the only way to stay safe.”

I couldn’t agree more: just ask the yoga studio rats.

And I say this as a person who has a deep respect for rats — for their sense of community, their ingenious ways of getting along with the humans who wish to eradicate them. And like owls, rats are intelligent. One of my former professors might observe that rats simply lack a good marketing team. Without re-branding, residents have a hard time seeing them as anything but undesirable. Rats are a sign of filth; they offend the human penchant for “clean.” In the same way that rats make us uncomfortable, so does visible homelessness. We might explain this feeling by saying we wish for others to be comfortable, to be taken care of. But if that’s really true, then why is the housing we offer so unlike that of already-housed folks? Is it that we feel our housing must be earned? That houseless folks are less deserving? I suspect this is an obvious truth. And it must feel quite comforting and virtuous of us when we see fewer homeless people on the streets. This means we — our City, our Region — are solving homelessness. But I challenge that for someone to move out of being “homeless” they have to actually find “home” — something we don’t provide with temporary, over-regulated, segregated, rights-limited housing.

A few nights after I heard the story of the owls, the rats, and the yoga studio, Kyle and I were chatting a few blocks from the parking lot. He was still unhoused by choice, waiting for something that wouldn’t break his bankbook or his soul. “I wonder about them,” he told me, as we gazed across at the new condo towers only a kilometer away. I wondered about them, too, thinking that some of the yoga studio clients likely lived there. “I wonder what they’re thinking — and if they wonder about us,” Kyle mused. “They’re so high up, they don’t close their curtains. They must think they’re invisible up there.” He chuckled and then pointed, “Did you see that? The light just changed in that window there. You can tell they’re channel surfing.” Finally, the light remained a faint green glow. Kyle wondered aloud what they were watching. I was feeling gloomy. “Probably a National Geographic program about owls,” I said. Our shoulders shook with dark laughter, and he nodded beside me. “Yup. Wildlife.”

…

Longshore Labor’s Real SF Worker-Intellectual

By Steve Early

“A new book about a Bay Area ILWU leader, whose own life as a working-class intellectual, over-lapped with Hoffer’s, presents a different view of Sixties activism and its impact on labor and society.”

In the 1950s and 60s, the best-known member of the left-led International Longshore & Warehouse Union (ILWU) was, oddly enough, a conservative writer named Eric Hoffer, whose fans included Ronald Reagan. Hailed in the mainstream media as the work of a “labor philosopher,” Hoffer’s first book, The True Believer, became a national best-seller and widely-assigned reading in colleges and high schools. In his writing, Hoffer argued that mass movements of the left and right were essentially interchangeable, and equally prone to dogmatism and extremism.

A Bay Area resident, Hoffer worked on the docks until 1967, by which time UC Berkeley had become an epicenter of student protest. He was a fierce critic of campus radicalism, warning that “for the first time in America, there is a chance that alienated intellectuals, who see our way of life as an instrument of debasement and dehumanization, might shape a new generation in their own image.” This was music to the ears of Berkeley administrators who made Hoffer an adjunct professor. In 1982, President Reagan invited his fellow cold-warrior to the White House to receive the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

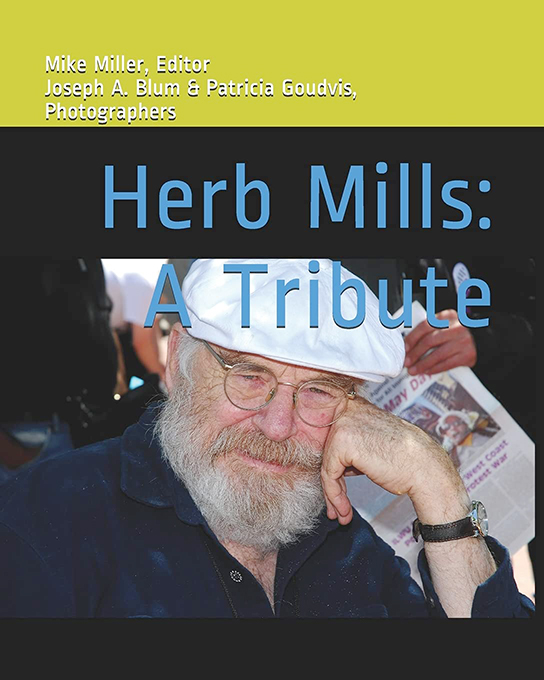

A new book about a Bay Area ILWU leader, whose own life as a working-class intellectual, over-lapped with Hoffer’s, presents a different view of Sixties activism and its impact on labor and society. Herb Mills: A Tribute (Euclid Avenue Press, 2021) is an edited collection about the unusual career of a dock worker and elected officer of ILWU Local 10, who helped shape the Berkeley student movement sixty years ago and, later, received his PhD in sociology from UC-Irvine. As recounted in this edited collection of interviews with (and articles by and about) Mills, his original migration from the world of blue-collar work to higher education began in Michigan. Born in 1930, he graduated from Dearborn High School and then went to work, at age 18, in Ford Motor’s huge River Rouge assembly plant. As Mills recounted later, “this plant was my education. River Rouge and its union changed my life.” United Auto Workers Local 600 was, at the time, under left-wing leadership, and encouraged its 40,000 members to take classes in US politics, labor economics and history at a local junior college. A professor there encouraged Mills to leave the factory and get a four-year degree at the University of Michigan, where he graduated Phi Beta Kappa.

A Foe of HUAC

After a stint in the Army, Mills moved to California, where he started graduate studies at Berkeley. He also joined SLATE, a campus political party which became nationally known for its multi-issue campaigning against racial discrimination in housing, the death penalty in California, military training on campus, and the investigative activities of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). As the ILWU Dispatcher noted when Mills died three years ago, at age 88, he “spoke to student and community groups across the country, explaining how citizens of San Francisco took action to successfully shut down HUAC, marking a shift from the anti-Communist hysteria that was used against unions, like the ILWU, during the Cold War.” According to fellow SLATE member Mike Miller, Mills was a “master strategist” for SLATE and “central to steering it through the thicket of left politics and maintaining its ability to win broad support.”

In 1963, Mills put his doctoral work on hold and became, like Eric Hoffer, a working member of ILWU Local 10. As a longshoreman, Mills was equally active on bread-and-butter issues, internal struggles to maintain the democratic character of the union, and ILWU refusals to unload military cargo destined for military dictatorships in Chile and El Salvador. He started out as a union steward, then stewards’ council chair, Local 10 business agent, and finally secretary-treasurer of the local, which remains in the forefront of Bay Area labor solidarity today. (On Juneteenth last year, the local was part of a West Coast port shutdown protesting the death of George Floyd and hosted a huge rally in Oakland featuring Professor Angela Davis, the former political prisoner who was just made an honorary ILWU member.)

For admirers of the ILWU and its legendary founder Harry Bridges, a San Francisco general strike leader in 1934, the most interesting part of Mills career will be his conflict with Bridges over implementation of the first Mechanization and Modernization (M&M) Agreement negotiated with longshore employers in 1960. As part of a “grand bargain” designed to raise wages and benefits while allowing the industry to reduce its labor-force through “containerization,” the M&M deal paved the way for a weakening of traditional union hiring hall protections. In 1971, management’s insistence on hiring some “steady workers” of their own choosing, rather than having all dispatched from an ILWU hall, triggered a 134-day walk-out. Strike action was opposed by Bridges but backed by a big membership majority.

Rebellion Against Bridges

As the Dispatcher reported fifty years later, this Mills-assisted rebellion against Bridges “tapped into a feeling among younger workers that Bridges had lost touch and was becoming too close to the industry.” In Mills’ view, “the social roots and bonds of the [longshore] community…were destined to be ripped asunder once the individual employer secured the contractual right to remove men from the functioning of the hiring hall.” Bridges, in turn, believed that strike advocates, like Mills, were “reckless and unwilling to face new realities.” In the end, the employers prevailed on the issue, a set-back which led Mills to call for Bridges’ retirement. The union founder finally stepped down in 1977, after trying to lead ILWU members back into the AFL-CIO, the Teamsters union, or the more conservative east-coast International Longshoremen’s Association, which the ILWU broke away from in 1937. A staunch defender of ILWU independence and autonomy, Mills campaigned successfully against any such affiliation or merger.

“all people should have the right and power to effectively participate in the decisions that affect their lives.”

During Mills’ own later career in Local 10, he tackled critical issues like the need for greater dock worker protection against workplace asbestos exposure. As noted above, he also helped mobilize ILWU members against shipments of military cargo to the Pinochet dictatorship in Chile and the armed forces of El Salvador, during their 1980s civil war massacres. Mills led Bay Area protests over the death of two ILWU local officials, whose opposition to the dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos led to their own assassination. He was also credited with helping to save the life of South Korean dissident Kim Dae Jung, who faced execution in 1980 for his political activities. Seventeen years later, after imprisonment and exile, Kim was inaugurated president of South Korea, with Mills and ILWU President Brian McWilliams as honored guests at the ceremony.

A Permanent Tribute

Contributors to Herb Mills: A Tribute include a number of retired ILWU members or headquarter’s staffers, along with longshore historians, sociologists, and labor archivists. Among them are ILWU Secretary-Treasurer Ed Ferris; Harvey Schwartz, curator of the ILWU’s Oral History collection at its SF headquarters on Franklin Street; Professor Peter Cole, author of Dockworker Power; former ILWU organizing director Peter Olney; Steve Stallone, the union’s ex-communications director; Sadie Williams, a member of the ILWU Local 10 pensioners Club; Ashley Lindsey, a researcher for the Waterfront Workers History Project; and Paula Johnson, who collaborated with Mills on a permanent exhibit at the Smithsonian Institution on the transformation of waterfront work.

The moving force behind this collection is Mills’ best friend for 60 years, longtime community organizer and labor educator Mike Miller, whose ORGANIZE Training Center, at 442 Vicksburg Street, San Francisco, 94114 is filling orders for the book. To order send a check for $30 to the OTC at that address or through PayPal, using the email address: theorganizermailing2@yahoo.com. In Miller’s own salute to Mills, he describes him as “a small ‘d’ democrat” who “could engage in the most esoteric political theory debates” Yet, from the Berkeley campus to local labor fights and cross-border solidarity campaigns, Mills’ core belief remained the same: “all people should have the right and power to effectively participate in the decisions that affect their lives.”

That Sixties-inspired creed and Mills’ personal example are both good guides for younger radicals making a similar post-graduate transition today– from campus or community activism to workplace organizing in unionized or non-union workplaces.

…

Biden’s PATCO Moment?

By Rand Wilson and Mark Dudzic

July 7th Update:

Today, The Labor Campaign joins MNA nurses from the St. Vincent Hospital Picket line, CWA-AFA President Sara Nelson, and a national coalition of activists to demand accountability from Tenet and support nurses’ strike for safer patient care during a 1pm ET LIVE STREAM in front of Tent Corporate Headquarters in Dallas, TX.

The demonstration in front of Tenet HQ marks the 122nd day on strike for St. Vincent nurses, making it the second longest nurses strike in Massachusetts history and the longest nurses strike nationally in more than a decade. As of that date, Tenet had spent an estimated $75 million to prolong the strike — all to avoid being held accountable for providing safer patient care.

This strike matters for all workers. Tenet has begun to permanently replace the striking nurses. This action, by a notorious healthcare profiteer has transformed a hard fought strike battle into a red line issue for the entire labor movement. It evokes the rampage of union busting that followed the Reagan Administration’s mass firing of striking air traffic controllers in the notorious PATCO strike of 1981.

WAYS TO SUPPORT

Sign and Share. Join the Labor Campaign, MNA, NUHW, and many others in calling for an investigation into Tenet and other large hospital systems. Sending a letter to your congressional delegation asking them to support an investigation is easy! Simply follow this link and add your name.

Tenet has made it very clear that they prioritize profits of patients and staff. There is ample evidence to suggest that Tenet Healthcare used COVID-relief funds to improperly expand its business, enrich its executives and shareholders, and prioritize the company’s bottom line over patients and caregivers.

Join us in calling for an investigation, today!

Join today’s demonstration– virtually. Nurses are bringing a giant, 16-foot-long petition signed by more than 700 striking nurses and will attempt to deliver the petition to Tenet’s CEO Ron Rittenmeyer. They will also call out Tenet for its blatant misuse of more than $2.6 billion in taxpayer-supported pandemic funding from the CARES Act stimulus package – funding that was supposed to be used by hospitals to provide PPE, staffing and other resources to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic, yet in Tenet’s hands was used to fund corporate expansion, pay down debt, and buy back stock for executives. Join via live stream at 1:00pm ET, today!

Donate to Strike Fund. Your donations go to helping support St. Vincent’s nurses.

- Contribute with: PayPal| Venmo

- Checks can be made payable to MNA St Vincent Nurses Strike Fund and mailed to:

MNA Nurses Strike Fund

Massachusetts Nurses Association

340 Turnpike St

Canton, MA 02021

.

Speaking on the recent National Solidarity Call in support of striking nurses at St. Vincent’s Hospital in Worcester, Massachusetts, Our Revolution leader Joseph Geevarghese characterized the situation as “Biden’s PATCO Moment.” The call was convened by the Labor Campaign for Single Payer to help mobilize national support for the 800 nurses at the Tenet Healthcare-owned hospital who are now engaged in the longest nurses strike nationally in over a decade. Tenet has spent more than $75 million to date to prolong the strike. A fraction of those funds could have easily met the nurses demands for the staffing improvements that are the sole issue driving the strike.

Now Tenet is threatening to permanently replace the striking nurses who are represented by the Massachusetts Nurses Association (MNA). This action, by a notorious healthcare profiteer (Tenet leveraged federal bailout funds intended to provide urgent relief to employees and patients to triple its profits at the height of the pandemic last summer), has transformed a hard fought strike battle into a red line issue for the entire labor movement.

For those of us old enough to remember, it evokes the rampage of union busting that followed the Reagan Administration’s mass firing of striking air traffic controllers in the notorious PATCO strike of 1981.

Busting the air traffic controllers’ union sent a signal to employers everywhere that it was acceptable for management to break strikes and bust unions. In quick order, striking workers from copper miners in Arizona to newspaper workers in Detroit found themselves permanently replaced. Even more significantly, it changed the balance of power in labor/management relations as labor’s most powerful weapon was neutralized. This ushered in a devastating period of concessionary bargaining whose consequences are still being felt today.

Reagan’s decision to fire the striking PATCO members was not some isolated act of pique by an outraged president. In fact, his administration jumped at the opportunity to give teeth to its explicit policy to weaken and undermine the considerable power of the U.S. labor movement. And it was very successful.

The U.S. labor movement was slow to respond to this provocation. Both of us can remember standing on the National Mall on Solidarity Day in 1981 with half a million other union workers. It had taken the AFL-CIO more than six weeks after the initial firings to call the rally and they chose to hold it on a Saturday when Washington was shut down tight for the weekend. As we dozed in the sun listening to endless speeches, we could see the planes taking off and landing unimpeded just across the Potomac at National Airport. What should have been a forceful exhibition of labor power had been turned into a demonstration of our impotence. Like many others who were there that day, we vowed to never let another PATCO moment go unchallenged.

Tenet is a key player in a major strategic sector of the economy. If it is able to make the threat of permanent replacement an acceptable management tool in healthcare bargaining, it will weaken the entire labor movement for decades to come.

That’s why the Labor Campaign for Single Payer and other labor groups are stepping up to support the nurses and their union. They will be joining the MNA at a rally on July 7 in front of Tenet Headquarters in Dallas. They are also circulating a petition urging members of Congress to join Reps. Katie Porter (D., CA) and Rosa DeLaura (D., CT) in requesting an investigation into the use of taxpayer-financed COVID relief funds by Tenet and other large hospital systems.

This strike could be a watershed moment for the Medicare for All movement by exposing the corrupt and anti-worker underpinnings of our for-profit healthcare system. “The simple fact is that, if we had Medicare for All, we wouldn’t even be in this fight,” said LCSP National Coordinator Rhiannon Duryea. “Nurse-to-patient ratios would be set by law, ensuring safe and effective staffing ratios across the country that protect nurses, patients, and the community. Hospitals would not be able to exploit nurses and patients to line shareholder pockets.”

This strike could also be a watershed moment for the Biden administration. Ronald Reagan reversed a 40-year policy to promote the right of workers to organize and to bargain collectively. Before Reagan, corporations feared using the permanent replacement option because the federal government had made it clear that it would not tolerate such brutal behavior in the course of labor relations. After Reagan, it was open season on workers and their unions. Inequality skyrocketed as wealth was massively redistributed upward.

President Biden, to his credit, has vowed to reverse these trends. He has made a number of statements explicitly supporting worker rights and has appointed a number of pro-union advocates to key policy positions.

This is his chance to send a message to Tenet and corporate America that there’s a new sheriff in town. We need to challenge the Biden administration to put its money where its mouth is and to intervene forcefully in this conflict. The president must make it clear that permanently replacing lawful strikers is contrary to the policy of the U.S. government.

Tenet is not alone in trying to pull the rug out from under an upsurge in labor militancy. There are a number of current and pending labor battles where management is engaging in overt union busting, including months-long strikes by coal miners in Alabama and steelworkers employed by Allegheny Industries as well as a nasty lockout of refinery workers at a giant Exxon/Mobil facility in Beaumont, Texas.

You can be sure that employers everywhere are watching how the Biden Administration reacts to these crises. As Our Revolution’s Geevarghese told the participants on the Solidarity Call, “This strike creates the opportunity for President Biden to undo what President Reagan did.” It’s an opportunity that should not be squandered.

…

2022, 2024 and Beyond, We best be talking to each other. And Organizing

By Robert Gumpert

This past week the Supreme Court ruled that suppressing voters by who they are is constitutional, as long as you don’t openly say that is what you are doing.

In 2022 and beyond it is more important than ever we find ways to bridge the gaps that seem to separate us by where we live and who we are.

For the last 4 weeks Anthony Flaccavento, Future Generations University, Liken Knowledge and Appalachian Voices have held the weekly webinar “Bridging the Rural Uban Divide”. While the series is now complete you can still watch and learn how to take part in further developments on the Forum.

You can get the guidebook to the series, “The Urban-Rural Divide: A Guidebook To Understanding The Problem And Forging Solutions”with links to resources, ideas and organizations here.

…

My Job as an Ecart Shopper

By Patrick Cummings

Editor’s Note: From time to time the Stansbury Forum invites students to write about their experiences. The following piece is about one recent graduate’s experience of “service work”.

During the winter of the Covid pandemic, after graduating with a degree in Math, I got a job at a “Chain Store” as an Ecart shopper within one day of searching. At the time, I was just glad that I had gotten a job so expediently, but perhaps I should’ve been more careful. The experience doing the job was completely different from what I had expected.

To be a “Chain Store” Ecart shopper meant that it was my job to “do other people’s shopping” for them. Orders were assembled from the previous day’s requests, including a complete and thorough listing of the desired items sorted by aisle or department, and grouped chronologically according to the customer’s desired pick-up time. I was to work my way through the store searching for items on the customer’s list, using a laser scanner to verify and mark off items as I found them, and then compile them all together into a cart. Once the items were collected, I had to bag them into categories of food type, such as all the frozen items had to be kept together, the merely cold ones were separated from that, while select meats get their own plastic bag, and wine bottles either get a nifty handbag or cardboard container, and so on. All refrigerated items were stored in a cooler or freezer to match their storage requirements, and all the remaining bagged items were left in the cart.

Every day, starting early in the morning and working into overtime hours at night (very commonly, we were asked to stay late; there was always more work than we could do in a day), me and my coworkers shopped.

Despite being labeled as a “low-skilled” job, I did not find anything low-skill about my task. Shopping very different orders in an entire grocery store, with thousands and thousands of different products seemingly scattered at random throughout the store, requires memorizing tons of minutiae. I never got a clear answer why the flat tortilla shells were only located on one particular aisle cap, or why the frozen pasta was next to fruit drinks. The Deli & Meat department was a mess, with food items not only in glass cabinets but frozen bins as well. And possessing a profound knowledge of different food products and their substitutes was crucial. Whenever an item was out-of-stock, it was my responsibility to find a close substitute for it to offer to the customer instead. But not only does that require having detailed knowledge of the former food item and substitute products out on the market, but it also requires knowing where the substitutes are in the store, if they were there at all. I remember clearly the day when a boss of mine, as a demonstration, helped me find a substitute cheese… by marching me to the opposite side of the store. I couldn’t help but think to myself: How could I ever find this substitute on my own? How am I supposed to memorize not only where items were, but the entire store catalog, and which items were not currently available? Most of my coworkers knew these things from years of practice, but I was asked to perform at their level now.

Another challenge of the job was the time-management aspect. Every order was supposed to be shopped in a half hour or less, and it didn’t matter how large or small a particular order was. Now technically, most people didn’t meet this ridiculous standard, and the pros took around 45-60 minutes for an order, but I almost always was running late. For me, this meant that I was constantly stressed out about finding an item, verifying it was the right one by bar code, and taking as many copies of the item asked for as fast as I could, but commonly it would take me at least 5-10 minutes to find a certain item (or just to affirm that it, in fact, was sold out), and then either move on or spend another 10-15 min frantically looking for a substitute for an item I had little understanding of. I soon had to resort to just not looking for substitutes at all, because it was simply too time-expensive to do so, but when my bosses started noticing my trend they started giving me smaller orders. Now, to be completely honest, this was an incredibly generous and kind move on their part. They had every reason and right to be mad, for I wasn’t living up to expectations, but instead they tried to work with me, and they said I would be tested here and there till my skills improve. Sadly, though, this warning served more to discourage me, because it meant more and more of my fellow employees would start to realize I wasn’t doing as well as them, and also, I didn’t want to get “special treatment” just because I wasn’t as skilled. I didn’t think I deserved it, for one thing, but I also anticipated people might start babying me, or grow resentful at my seemingly unfair treatment, or might start to expect me to make mistakes, and jump to assuming I did something wrong if some other mishap happened. People started double-checking my orders when I arrived, interrogating me about any missing items, double-checking that what I reported was true, and so on.

Least of all did I expect the customers to be an adverse aspect of my experience. While trying to maneuver my way through the store, I had to circumvent and give courtesy to shoppers along the way, and not all of them were graceful. Everyone always expected me to know where every item was. There was one male shopper, for example, who asked me where he could find some obscure item, and once I admitted sadly that I didn’t know where it was, he scoffed at me and walked away. I soon learned to wait for customers to greet me rather than me greet them, as well, because early on I gave customers a warm welcome as they entered the store, saying “Hello! Welcome to “Chain Store”!”, but sometimes they coldly avoided contact and rushed off. Worst yet were the times when we had a mad customer outside waiting for their Ecart order. We delivered the orders, usually having been shopped by ourselves personally, to the very recipient customers in the parking lot. Every once in a while, my coworkers and I would run late on a delivery, and the customers would get pissed off, yelling at any of us they came in contact with until their order arrived. It was soon very difficult for me to feel like I had any respect or dignity as a “Chain Store” employee and couldn’t feel like my work was appreciated or even worthwhile.

Finally, the day arrived when my boss yelled at me in the middle of the store completely unexpectedly. I had to piece this together after the fact, but supposedly, a coworker of mine reported that she had asked me to stay late to help with some final orders the night prior, but I left at the end of my shift. I sure didn’t remember anyone asking me to stay, so when my boss asked me about it, I started to stutter that I didn’t recall her ever asking me, but my boss wasn’t in the mood for excuses and flatly shouted, “If we ask you to stay late, you stay, alright?!” That made it pretty clear how they felt about overtime: it wasn’t requested, it was mandatory. Once this happened, I had had the last straw. So many aspects of the job were not going well, and now I’m getting yelled at because I’m an easy target to blame. I finished out the week and quit.

I can keep going with many other aspects of the job that were difficult, such as a previous elbow injury acting up and causing me severe pain while trying to work, but I’ll try to wrap up with this last important point. One of the things I quickly learned with this job is the monotony and repetitiveness of its task. It’s a job that’s fast paced and very object oriented, and thus there’s not much space of time or memory to let your mind wander. In short, I soon realized that I couldn’t think about math questions or philosophy—topics dear to my heart—in the quiet of my mind while doing this job. The lack of focus slowed my pace and caused me to forget important details of the grocery item I was shopping for. For the first time ever I experienced what it’s like to be an automaton, a thoughtless and mindless cow, whose sole focus and capacity for attention was the very task in front of them, one moment to the next. There was no room for reflection, for active inquiry or questioning, or even remembering. This was especially difficult for me given my natural proclivity to thought. I could tell that as weeks became months, it started to feel more difficult to think like a philosopher or a mathematician, as I did only a few months earlier, even after my shift was over. Those parts of my mind and brain were atrophying very quickly from a lack of use, and that made it harder to even consider them outside of work. This helped me see how hard it could be to study math or philosophy on the side while holding a job like that, for it’s like asking a person to be a robot for 8 hours of the day and a thinking human during the off hours. You just can’t be both simultaneously.

Several months since quitting, I look back on the job as a valuable insight into the lives many people are forced to lead in the US. I have heard it said that most people spend their lives reliving the same year over and over again, my job made me see that as it was even more repetitive than that; it was the same day repeated over and over. Nothing changed about this job – no beautiful glimpses of creativity or novelty could be found. When I look back on my experience I ask myself, what sort of worker I would have needed to have been to be especially good at it. It would have been very helpful if I had been more mindless and thoughtless, less prone to the distractions of reflection and self-conscious contemplation, as these meta-level thoughts slowed down my dizzying manual labor. It also would have been good if I didn’t have any pride or dignity, as then I wouldn’t have recognized the indignation of this job or the way my customers treated me. Furthermore, we might as well rule out all emotional connection with my work, including the ideas of loving your job or yearning to feel like my efforts were making a genuine difference toward the good of society, all of these aspirations would’ve been thwarted.

But is this really the kind of people society wants to cultivate or needs? Thoughtless, servile, nihilistic, and self-erasing? No wonder the turnover is so high in this area of employment. No human being wants to be like that.

…

Overcoming the Divide – Part 3

By Robert Gumpert

Adam Serwer wrote today in his NYT opinion piece, “The Cruel Logic of the G.O.P.” there are “no Democratic proposals to disenfranchise Republicans”, not because Democrats are nicer but because “parties reliant on diverse coalitions to wield power will seek to win votes rather than suppress them.”

Mr Serwer points out that the Republican brand of White identity politics is not new. Starting in the 30’s those same politics were the stock and trade of the Democratic Party, the party was remade by “a coalition of labor unions, Northern Black voters and urban liberals.”

To have such a coalition now we must bridge the urban – rural divide. To that end Future Generations University, Liken Knowledge and Appalachian Voices has sponsored a webinar series “The Rural-Urban Divide: How We Got into This Mess, How We’ll Get out”, hosted by Anthony Flaccavento, Virginia famer, activist, and occasional writer for the Stansbury Forum, with a series of guest speakers.

You can listen/watch the first 3 sessions on the Forum (1, 2, 3rd is below) and register here for the fourth and final session on strategies for overcoming the divide.

.

The 3rd session begins the discussion on solutions for bridging the gap between rural and urban communities. Special guest speaker: Ericka Etelson, author of “BEYOND CONTEMPT – HOW LIBERALS CAN COMMUNICATE ACROSS THE GREAT DIVIDE”.

…

Can rural and urban communities be united? A Beginning

By Robert Gumpert

“Most of the mines, most of the coal and mineral rights, in Harlan Kentucky and all of East Kentucky, is owned by outside interests, big oil and utility companies. I’ve been to several foreign lands, but this is, I believe, the first colony in North America that I’ve ever visited. They come in here, they take everything out, they don’t put anything back in. They don’t pay their fair share of taxes. The roads they haul the coal over are in real bad shape because of the overloaded coal trucks. They own the company houses. They own the stores that people trade in. They own the towns they live in. Their water supply is furnished by the company. Their electrical supply is furnished by the company. These people are completely dominated and dependent on the whims of the coal operators.” Huston Elmore, UMWA head of the organizing drive at the Brookside and Highsplint coal mines during the 1973-1974 strike.

In 2021 can rural and urban communities say things are that different? The corporate names have changed, but the business is the same, extraction, of minerals, goods, and workers’ wealth and health.

The Stansbury Forum is posting the latest sessions of the Rural-Urban Divide Webinar Series, last Tuesday’s 2nd talk is below.

After watching find out how to ask questions stemming from the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd sessions here

The 3rd session will begin the discussion on solutions for bridging the gap between rural and urban communities. Special guest speaker: Ericka Etelson, author of “BEYOND CONTEMPT – HOW LIBERALS CAN COMMUNICATE ACROSS THE GREAT DIVIDE”.

…

Volvo Workers Back on Strike at Virginia Trucks Plant

By Ben Solidaridad

Some 2,900 auto workers at the Volvo trucks plant in Dublin, Virginia are once again on strike after walking off the job for nearly two weeks in April, returning to work, and then voting down by wide margins two contracts negotiated by their union, the United Auto Workers (UAW). The current struggle at Volvo has been ongoing since February, when contract negotiations between the company and union began. Throughout this entire period, workers have maintained their solidarity and steadfast determination to win a better deal from the bosses and beat back years of concessions from previous contracts, including a much-hated two-tier wage structure in place at the plant.

Compared to the 13-day strike in April, this time around management has adopted a harder line against the strike. The bosses have cut off workers’ healthcare and are actively encouraging workers to cross the picket line. In addition, the company has carried out a “survey” of property lines around the plant and marked these lines in front of the facility. The point of this is to push the striking workers closer to the road and undermine the workers’ ability to stage an effective picket line. In the process, this has also made the picket line more dangerous for strikers. Beyond that, Virginia State Police have pressured and threatened the union to stop workers from blocking scabs from entering the plant. A Tuesday post on the UAW Local 2069 Facebook page notes that, “The State Police has informed us to not block the entrances of the plant. We do not want to see anyone get in trouble and we want law enforcement to stay neutral in this process. Do not cross the picket line. Many places are hiring. Take care of your union brothers and sisters on the line and make sure they do not overheat.”

In response to this, it must be said that law enforcement is never neutral when workers enter into struggle. The police are on the side of the bosses, and their efforts to facilitate scabbing at the Volvo plant are just the latest example in a long history of strikebreaking and other attacks on workers.

As it is, Volvo workers are now once again in the middle of a high-stakes struggle with a multi-billion-dollar company. The entire labor movement and the socialist movement have an obligation to support these workers and shine a light on their vitally important fight, which has ramifications for the entire class struggle.

On Sunday, June 6, the workers voted for the second time in less than a month to reject a tentative agreement negotiated by the company and the International UAW by a margin of 91 percent for salary language and 90 percent for common language. This surpassed the previous rejection of a tentative agreement on May 16, when workers turned down that contract’s salary language by 83 percent.

Following the most recent contract rejection, UAW Secretary-Treasurer and director of the union’s Heavy Duty truck department, Ray Curry, sent a public letter to Volvo management on Monday declaring that the union would walk off the job later that day.

The strike targets a critical point in Volvo’s supply chain, with the April walkoff shutting down production at what is Volvo’s only truck production facility in all of North America at a time of booming demand for Volvo trucks and commercial vehicles more generally. The initial strike at Volvo ended on April 30 when UAW officials announced that the union had reached a new tentative agreement with the company and that workers would return to work the following week. As reported in last month’s edition of On the Picket Line, this arrangement was made despite the fact that striking workers had not been allowed to see or discuss, let alone vote upon, the tentative agreement negotiated on their behalf.

As it turned out, the initial tentative agreement that followed April’s strike was filled with what many workers felt were unacceptable concessions and failed to address the core grievances that led workers to strike in the first place. Notably, the problematic content of the contract was only brought to light as a result of the organized efforts of rank-and-file members. The proposed contract was not put online, but members obtained copies of the agreement from the union hall and circulated the proposal to their coworkers in the plant, according to a report from Labor Notes.

In terms of the content of the tentative agreement, workers were angered to learn that the deal failed to abolish the hated two-tier wage system in place at the plant. In addition, the contract included significant increases to out-of-pocket health care costs for workers. Language in the contract also enabled union officials to agree to a so-called Alternative Work Schedule, including “four 10-hour days, alternative shift operations, or other alternative schedules based on the needs of business.” This proposed scheme may abolish time-and-a-half pay for work after eight hours. Notably, such alternative schedules – which have already been implemented at many Big 3 auto plants across the country – are beneficial to management as they allow companies to boost productivity and cut wage costs by paying less in overtime.

According to a worker interviewed by Labor Notes, the successful “no” vote was largely organized through word of mouth and face-to-face discussions by workers. In addition, online discussions and campaigning in a private Facebook group with some 1,900 members also factored into the contract rejection.

Following the initial “no” vote, the next development in the contract struggle came just four days later when, on May 20, the UAW announced that it had arrived at a new tentative agreement with the company. In the press release published by the union international, Ray Curry heralded the new deal and declared that, “the agreement addresses [the] concerns” of rank-and-file members that voted down the previous contract. Many rank-and-file members, in contrast, argued that the new contract did not meaningfully improve on the previous deal. This point was made clear in a rank-and-file petition released the same day as the announcement of the new tentative agreement. The petition – which was circulated as a flyer, posted online, and subsequently reported on in a news segment by the local Fox affiliate, WFXR – denounced the proposed agreement as “almost identical to the previous agreement.” The petition also called for the recall and replacement of union officials.

The resounding contract rejection on June 6 made it clear that workers are not willing to give up their struggle and accept the company’s terms for a new contract. Thus, by their determination, members have pressured their union to continue the fight. This success was made possible by a vigorous rank-and-file movement within the union that, at times, has come to take on the character of a struggle for union democracy. This dynamic will undoubtedly persist as the union fights the company on the picket line.

Notably, workers’ eagerness to fight the company is connected to the fortuitous economic situation at Volvo right now. While Volvo, like all multinational auto companies, has been impacted by the global shortage of semiconductor chips used as component parts at assembly plants, production demand for new heavy duty trucks is currently skyrocketing. The trade publication FleetOwner has reported that, as of March, monthly North American orders for the Class 8 truck produced at the plant had exceeded the company’s productive capacity for the previous six months. Meanwhile, the head of the commercial transportation consulting firm ACT Research has declared that “Demand for commercial vehicles in North America is about as good as we’ve seen in 35 years of monitoring heavy-duty market conditions. Times are so good that demand is far outrunning the industry’s ability to supply right now, and that will likely remain the case into the autumn and perhaps even through the winter.”

Volvo is also making money hand over fist. On June 1, Volvo announced that it would be providing a $2.3 billion dividend payment to the company’s investors. As Volvo CEO Martin Lundstedt announced in a statement, “The board believes that the Volvo Group’s improved profitability, resilience in downturns and strong financial position enable a distribution of the proceeds. Even after the distribution, the group is financially strong with resources to invest in future technology.” Clearly, the bosses have the money to meet workers’ demands – and their claims of poverty during contract negotiations have been entirely fraudulent.

On top of these conditions, the Volvo plant in Virginia has been massively expanding in recent years. According to statements by the company, the Volvo trucks plant is in the middle of a $400 million expansion and upgrade. Since 2016, the plant has added some 1,100 additional jobs – and it plans to add some 600 more during the course of 2021. As already noted, the Virginia plant is Volvo’s only North American production facility, which means that a protracted strike at the plant could completely choke off the sale and delivery of new Volvo trucks for the entire continent.

Within this context, some workers have asked: If not now, then when? If we don’t fight to win back previous concessions and smash the two-tier wage system right now, then when in the future will be a better time?

Notably, what happens with the struggle at Volvo has implications not only for the thousands of workers employed at Volvo, but potentially for the broader workers’ movement, as well.

In the past several years, a movement for union democracy and a full-scale revival of the UAW’s proud tradition of militancy has developed within the ranks of the union. This movement has taken shape within the context of a protracted federal investigation into widespread corruption within the top ranks of the UAW bureaucracy. On top of this, UAW workers have grown weary of international union officials’ propensity for cozying up to the bosses and implementing company demands for concessions.

An internal caucus, Unite All Workers for Democracy (UAWD) has been organized by rank-and-file members with the goal of rebuilding the type of militant, class-conscious movement of auto workers that is capable of taking on the auto bosses. The UAWD is campaigning for members to vote yes in a referendum, which will take place within the next six months, that would allow rank-and-file members to directly elect the union’s executive board and president. The upcoming vote is stipulated in a consent decree agreement between federal prosecutors and UAW officials stemming from the corruption probe. UAWD activists have portrayed the campaign to win a “One member, One vote” election system as a fight to “win a more democratic system of electing our International officers [that] would allow for every member’s voice to be equally heard.”

On a political level, the fight for trade union democracy is inseparable from the struggle to transform the unions into fighting organs of the working class. This is a point long upheld within the Marxist movement. In his incisive 1940 essay “Trade Unions in the Epoch of Imperialist Decay,” Leon Trotsky argues that “It is necessary to adapt ourselves to the concrete conditions existing in the trade unions of every given country in order to mobilize the masses not only against the bourgeoisie but also against the totalitarian regime within the trade unions themselves and against the leaders enforcing this regime.” He adds, “The primary slogan for this struggle is: complete and unconditional independence of the trade unions in relation to the capitalist state. This means a struggle to turn the trade unions into the organs of the broad exploited masses and not the organs of a labor aristocracy.”

…

Orginally published in: Workers’ Voice/La Voz de los Trabajadores

To win in 2022 and 2024 we must connect the rural and the urban – find out how

By Robert Gumpert and Peter Olney

Last Tuesday, the 8th of June, the co-editors of the Stansbury Forum “attended” the first of four webinars on bridging the urban-rural divide. The remaining three run on consecutive Tuesdays, starting on the 15th of June.

The 2022 elections are coming on fast, the time to start organizing is now. They will be overwhelmingly important to working folks – their jobs, income, health, freedoms – and to the democratic process of the country.

We must find a way to engage all in these coming fights, to connect people of common interests in both the urban and rural communities.

Anthony Flaccavento, a Virginia farmer, activist, and occasional writer for the Stansbury Forum, is hosting a series of four webinars on how we can best connect people in these two settings.

Below you will find a brief description of the series, a link for registration to the remaining three sessions and a video of the first section. Anthony has requested, recommended, that the video should be watched first if you did not attend the first seccsion.

Peter and I hope to “see” you there.

.

Future Generations University, LiKEN Knowledge, and Appalachian Voices invite you to join Anthony Flaccavento and some of the best thinkers and doers from across the nation in a deep discussion of the underlying causes of this divide and how it can be overcome. You’ll learn:

- Six underlying causes of the divide and how they reinforce each other

- How the neglect of rural development has enabled the divide and how effective, bottom-up rural development strategies can help reverse it

- Better, more accurate ways of understanding rural perspectives on regulations, the environment, and the role of government

- Much better ways to talk about and talk to rural communities

- Other tools and strategies for overcoming the divide

The rural-urban divide is deep, it’s widespread, and it’s getting worse. Liberal people from cities and suburbs think most rural folks are ignorant, racist, stuck in the past, their communities heading towards oblivion. Many in the countryside view urban people, academics, and the government as elitist, contemptuous of rural ways, and dismissive of the people living there. While race and racial resentment play major roles in this polarization, the divide between urban and rural is perhaps the most poorly understood component of our divisions. And it’s killing us, enabling the richest people and biggest corporations to dominate our democracy while the great majority of us fight amongst ourselves.How did we get here, and how do we begin to overcome the divide? More to the point, what role has those who espouse a fair and just world played in exacerbating the divide, and what must we do differently?

The Rural-Urban Divide:

How We Got into This Mess, How We’ll Get Out

Register – Here.

…

Labor Must ‘Block and Build’ to Defend Democracy

By Rand Wilson and Peter Olney

In “The White Republic and The Struggle for Racial Justice,” Bob Wing contended that the U.S. state is racist to the core, and this has specific implications for our movements’ work going forward, especially the need to replace this racist state with an anti-racist state. Organizing Upgrade is publishing a series of commentaries on this piece, and we invite readers to respond as well. In this response, Peter Olney and Rand Wilson look at the role that labor unions can play in building the cross-class front against what Wing calls “the re-entrenchment of the white republic.” From their long experience as union organizers, they draw the lesson “thatunity and awareness of our shared enemy is built among trade unionists and allies in the trenches of common struggle.”

Bob Wing argues in “The White Republic” that American capitalism is firmly rooted in the appropriation of the lands and labor of native peoples and African slaves. Throughout U.S. history this system has been one of white supremacy and racial oppression, not only of Native peoples and Blacks, but also of other exploited peoples like Asian Pacific Islanders and Latinos.

The 2020 Presidential election, the battle for the Senate in Georgia, and the January 6 Capitol insurrection illustrated the white supremacist forces at play, Democracy and majority rule are in the cross-hairs. Republicans are moving in lockstep to suppress and oppress the votes of people of color to preserve minority rule. The recent spate of state legislative initiatives to restrict voting is the closest thing to the “Jim Crow” era since before the Civil Rights Act of 1965.

We accept the veracity of Wing’s analysis, and the need for a “united front” to defeat and destroy the white supremacist forces in the long term. Our challenge in trying to bring the labor movement into that front is to operationalize a perspective that builds antiracist practice, tackles white supremacy and fights capitalism – and to do that among a membership that is not rooted in a shared identity or philosophy.

It’s no easy matter. Demographics are not destiny – at least not fast enough. The country remains 62 percent non-Hispanic white. And as we saw in the last election, Trump’s racist, proto-fascist appeals garnered 73 million votes, and his vote totals increased in both Latinx and Black communities.

As lifelong trade unionists, we embrace the challenge of building the broad united front between labor and communities of color to defeat white supremacy. But how best is that elusive unity built? Imagine going to a union meeting and denouncing the “white republic” when many cars and trucks in the parking lot sport “Blue Lives Matter” bumper stickers. It’s a recipe for a very heated exchange, or worse, a brawl! What’s really needed are ways to open discussions with members that don’t condescend or polarize, and do involve deep listening and identifying common values.

Many union leaders have begun this process by centering racial justice in membership education programs, organizing campaigns and bargaining. “Labor organizations are taking up the fight for racial justice in many ways,” wrote Stephanie Luce in a profile of contemporary efforts by union leaders. “They’re developing in-depth member education on racial capitalism. They are using bargaining to address structural racism and developing new leaders.” Luce also cites SEIU 1199 in New England which has used Bargaining for the Common Good to build relationships and common demands with racial justice organizations. This is one approach.

Bonding Through Common Work

Experience tells us that unity and awareness of our shared enemy is built among trade unionists and allies in the trenches of common struggle. We are inspired by the work of UNITE HERE and other unions in battleground states like Arizona, Nevada, Pennsylvania and later the Senate race in Georgia in 2020-21. The bold decision by a few union leaders to recruit and support their members to canvass on the doors during the pandemic built lasting relationships and respect with the organizations of Blacks, Latinos and Asian Americans already deeply engaged in those battleground situations.

The union banners, T-shirts, and buttons (we do bling well!) were welcomed in action, as was the experience and courage of these able trade unionists of all colors. Nothing bonds people better than working together in 95-degree heat, with a mask, a visor, and the determination to knock on every door. That joint work is worth a thousand educational sessions.

The great Italian Marxist philosopher and organizer Antonio Gramsci points to the limits of education and intellectual argument in this passage on “Philosophy, Common Sense, Language and Folklore” from his famous Prison Notebooks:

“Imagine the intellectual position of the man of the people: he has formed his own opinions, convictions, criteria of discrimination, standards of conduct. Anyone with a superior intellectual formation with a point of view opposed to his can put forward arguments better than he and really tear him to pieces logically and so on. But should the man of the people change his opinions just because of this? Just because he cannot impose himself in a bout of argument? In that case he might find himself having to change every day, or every time he meets an ideological adversary who is his intellectual superior. On what elements, therefore, can his philosophy be founded? And in particular his philosophy in the form which has the greatest importance for his standards of conduct?”

The 2022 midterm elections offer an excellent opportunity for the “men [and women] of the people” to forge new convictions and standards of conduct.

2022: Next Battleground, Foundation for Change

Maintaining the momentum to win progressive legislation and beat back the far right and the “big lie” requires a broad commitment to win seats in the 2022 midterm elections on November 8 – and win big. It’s no easy task. The political system is rigged against Democrats who got five million more votes in their 2020 races for the U.S. House of Representatives yet lost 11 seats in Congress.

Can we defy history and increase Democratic margins in the House and Senate? Can we afford not to? The 1934 midterms during Roosevelt’s first term in the midst of the Great Depression are inspiring. Gains were made in both the House and Senate that enabled the passage of key legislation like the National Labor Relations Act, which encouraged millions of workers to fight for and form new unions.

The 2022 midterms are perhaps more monumental. The Trump forces will be determined to recapture both houses of Congress and stymie any positive Biden initiatives in the second two years of his presidency. They will have all the advantages of their voter suppression laws and gerrymandered districts. But the ground forces on the front lines in the last election will not be deterred. They will be out again, and with even more gusto.

LUCHA in Arizona will fight to keep Democrat Mark Kelly in the Senate. The New Georgia Project and Stacey Abrams will be rolling up their sleeves to defend the Senate seat of Rev. Raphael Warnock. All the battleground locations will see healthy mobilizations of activists from all over the country eager to defeat the right. These are the battles that labor must join, and these are the flashpoints where multi-racial unity will be forged in the common struggle to preserve the forward march of the pro-labor Biden agenda and stem the racist right.

Time is Running Short

Prior to the midterms, there will be important primary challenges by progressive Democrats running to win against corporate Democrats. Nina Turner’s primary campaign for the recently vacated seat in Ohio’s 11th congressional district is a great example. These pro-labor/pro-racial justice candidates need support, especially where Democrats have safe seats. But once the 2022 primaries are over, labor must focus on competitive races where congressional seats need to be defended or where seats can be gained. In addition to the seats held by Senators Kelly and Warnock, there are six more Senate seats where Republicans are resigning or are vulnerable, in North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Wisconsin, Florida, and Missouri.

The labor movement can draw much inspiration from the experience and energy of 2020 combined with the surprisingly good performance of President Biden. The new administration’s taming of the pandemic and its robust stimulus and infrastructure bills should create the foundation to peel away many of the estimated forty percent of trade unionists who voted for Trump. Particularly in the more conservative building trades, funding for infrastructure is something to fight to preserve and extend. Biden’s shutdown of the Keystone XL pipeline, a big issue that many building trades leaders railed against under Obama, is being overshadowed by the massive infrastructure proposals.

After detailing the billions of dollars of infrastructure spending that Biden is proposing in an editorial to the membership, International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW) President Lonnie R. Stephenson wrote, “This is enough work to last from apprenticeship to retirement not just for you, but for tens of thousands of new union members in our brotherhood alone…This bill means hundreds of thousands of jobs for construction members, but also for our members in utility, telecom, railroad and broadcasting.”

Stephenson knows “A Lifetime of Work” is what will motivate IBEW members to support the plan regardless of how they voted. And that is what will motivate the IBEW and other unions to recruit and send members to preserve the possibility of anti-austerity measures like the infrastructure bills that have a direct benefit to working people. Few IBEW members will ever embrace the notion of a “white republic” or “racial capitalism,” but when those members are in the trenches (or on the doors) with Blacks, Latinos and Asian Americans with a common purpose, they will come much closer to supporting Wing’s call for “a powerful antiracist movement of people of color and whites” to “defeat the white supremacist right, transform or replace the racist institutions that dominate the country, and to reconstruct society based on peace, sustainability, and justice.”

We can think of our strategy going forward as “Blocking and Building,” as laid out by Tarso Ramos of Political Research Associates. “We need to block the Right Wing…and build relationships, strategies, and campaigns of deep solidarity and shared power across the communities that together will build real multi-racial democracy,” Ramos said. For us in the labor movement, this looks like blocking white supremacy, preserving a pro-labor agenda, and building our power. Funding and supporting union members for the ballot brigades in the key 2022 election races will be the most concrete way to dovetail labor and race in the trenches.

In the run-up to the November 2020 election, Labor Action to Defend Democracy (LADD) was formed to protect the election from being stolen. It was an exciting and relatively broad formation supported by many union leaders. Combined with the energy and resources of other progressive labor initiatives, LADD could be reassembled in some form to support activist union members in the key battleground states to work alongside local organizations battling the Trumpista white supremacists.

Bob Wing’s work is theoretically sound. The Block and Build labor brigades are one example of how to put that vision into concrete strategic practice. It is time to get cracking, as we are only 17 months out from our day of reckoning: November 8, 2022.

…