Straight Off Willow Street

By Robert Gumpert

Next month, the 14th of September to be exact, California’s Governor Newsom faces a recall election. A loss will mean a Republican governor with consequences for the state, the nation, and the Democratic Party, including but not limited to: a Senate appointment if Senator Feinstein takes early retirement, or dies, in turn affecting any possible Supreme Court opening.

As always, the outcome will depend on turnout.

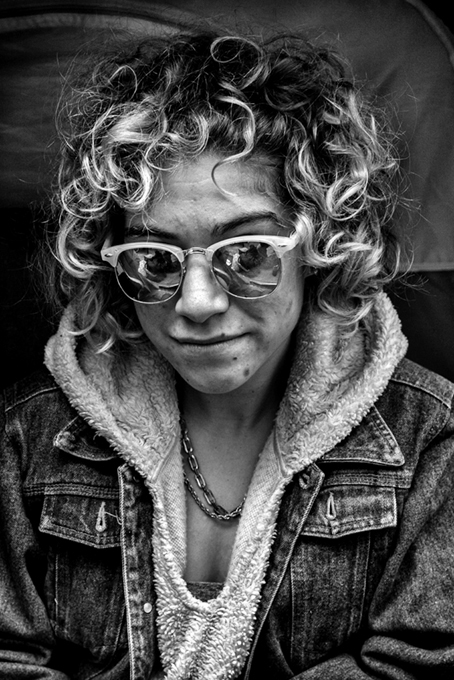

But today’s post presents three voices from the unhoused because those living on the streets of our cities, towns and roadways have been made a an issue Republicans hope to ride to victory, bringing their form of limited government for the rich to the country’s most populated state.

So instead of talking about those living on the street as the enemy in a domestic war, today take a moment to read what they have to say about their situations dealing with forms of the problems anyone without unlimited resources faces.

And remember, if you are a registered voter in California Vote No on the recall, for the your future you, the future of your kids and the type of community you want to live in.

All three folks were living on Willow Street in San Francisco’s Tenderloin district on the 25th of August when the city conducted a homeless “resolution” operation – meaning people would be offered “places”. If they refused what was offered, they would have to move on. No surprise to anyone involved with housing issues there were only five spaces, all shelter beds for women. There were more than 20 men and women living on the two blocks being worked and the operation was changed to a “cleaning”, people move all their belonging out of the way and public works come through and sweep and wash the street and sidewalks before people move back.

.

“Any type of services I’ve had to debate whether or not I’d take it or not. The people who are coming to see us, they’re asking us to leave. They’re coming with the police. They’re coming with garbage trucks telling us we got to go, tents aren’t going to be allowed up, and then they say but we’ll send you to tent city. Ok, so I can’t sleep on the streets in a tent but you’re going to put me somewhere where I can be in the street, in a tent. Then I find one of the places where they do this tent city and it’s gated in. It’s covered so no one can see in, nor out. It’s locked doors, and I have to sign in and sign out. All that reminds me of jail! And it also takes me to a point where it was the Chinese, they did that to, concentration camp. Why would I want to put myself back in a situation where I feel like I’m back in jail but I’m on the street? Why would the city want me to stay off the street in a tent but pitch me in a place where there are tents but no one can see me? Are they helping me? Or are they helping themselves? They’re helping themselves. They don’t have to see us, then they don’t have to think about us. But for some people you get out here it’s just much easier not to have to pay rent. Not to have to have the nut. Not to have to do these things.”

“I’m out here and I don’t particularly like it but my addiction say if you want to beat me you have to be about me, but know what you want to be. I’m not trying to stay in too long. I have friends out here 13, 14, 15 years, finally got a place to stay. I’m happy for them. I would like to get my own place, haven’t achieved it though I’m trying.”

“If I give in to my addiction but not give up on life, that’s the difference.”

“I can give up just living life on life’s terms and go into my addiction, and let my addiction do it’s run because it’s only a run. They always talk about “this was my bottom”, but even bottoms have bottoms. So you might stop for a moment, get it right, then find out there’s another floor to my bottom. I got to go through it because in order to understand it I got to get there. If I don’t then I keep lying to myself and putting myself in situations where everything is destroyed. If I give in to my addiction but not give up on life, that’s the difference. A lot of people are giving up on life. You talk to some people, and they say they’re dead. They’re spiritually dead. I’m not giving up because I do have things I want to live for, and I want to live. I want a better situation for myself. I know I can have a better situation for myself, but I need to go through what I need to go through. I just have to get through this the best way that I can.”

“Some things I just need around me and that keeps me human”

“Accepting help is alright when the help comes that’s really helping and not just trying to shove me out of the way. You (the city) send somebody in here to talk to us about going someplace. You ask, “them where can you go?”, and they tell you. You ask them where it is and they say, “Oh I need to call my boss to find out.”

What kind of information are you bringing me? If you ain’t got it right, what makes you think I’m going to go someplace you’re telling me to go? I’d rather stay where I’m at. At least I know what’s ahead of me. I don’t know what’s ahead of me, going where you telling me to go, cause you don’t have the information telling me how to even get there. I’m not going to something that’s half told to me. When you’re in this life you don’t want to wait. I ain’t got time to sign no paper. I need to go get mine, my drug of choice. I need to start my day even before I can even think about what you’re telling me.”

“I’ve left and came back and they’ve thrown away everything I own including my ID, Social Security card, Medicare card. Everything that you need to collect services, which takes time to get back.”

“You get thrown in this pet camp. You got people on the door telling you what you can and cannot do. They give you a place to sleep, eat, but you can only take certain items. You telling me get rid of all that and sleep on a palette, in my tent, and everything I own must be in my tent, or I can’t have it. But somethings you get attached to. Some things I just need around me and that keeps me human. Now you want me to be inhuman. I got to live in this tent, most of them are 6×9, same size as a jail cell. You can’t move around. Once you’re in, you got to stay in and stay still. That’s all jail to me. It brings it all back.”

“I’m going to get better. My run’s just about over because I’m tired. They say you got to be tired of being sick and tired, but it’s just something that they say. But if you’re tired, once you rested up you have the energy to go do it differently. That’s what happens when you relapse. It’s got to be more than being tired of being sick and tired. You got to be through with going through the door you been going through. It takes time. Everybody can’t do it the first time, you might have to do it multiple, multiple times. I’ve been called a recovery junkie because I relapse. I don’t relapse right away, I’ll be a year here, six years there, it’s all a constant fight.”

“The people that you’re (the city) sending out here, they’re not offering services, they’re just offering us to be out of the way. It’s not fair to those that really want some help, you have to wait for so many things.”

“My belongings are all I have. They’re how I survive. My clothing and you know, my knife, pepper sprays, and things like that. I use them for everything including protecting myself from weirdos. Without my cloths I couldn’t protect myself from weirdos either, and I’d be walking around naked.”

“At this point I’m desperate just to be safe and have somewhere I can go and be safe and warm, and not have my things be stolen from me everyday.”

“My belongings is like my wife. You know it’s what I have to live for, what I work for. I put a lot of effort into doing things that I need to do to keep myself going and that’s what my things are. My things aren’t just like materialistic things, they’re something that actually means something and gets me going throughout the days.”

[When they come through and take it all] “I wouldn’t say (I’m) angry, I’d probably say hurtful because people don’t know how it is for people that stay on the streets without nothin’. People don’t see or realize how much hard work we have to do to get what we need. It’s like a waste of time, that’s why it’s so hurtful because we work for what we get.”

“My dog. He’s a puppy. It’s the first time I’ve actually raised a dog with like my bare hands. You know what I mean? He’s well trained. He’s well listened and he’s someone I love. He’s not just an ordinary dog, he’s like a human. He means a lot.”

…

The political right is growing in Italy because there is no Workers Party for Socialism in the 21st century

By Maurizio Brotini and Lepoldo Tartaglia

The Stansbury Forum is proud to publish an analysis of the rise of the right in Italy by two leaders of the CGIL, the largest national Italian labor federation. This article is translated from the Italian original.

I.

From the international point of view we have been witnessing for years a crisis of US hegemony. We have gone from the inability to form a coherent Western coalition to address the so-called war on terror imposed by the Bush Administration, to the financial crash of 2008, to the election of Trump as President: all unequivocal signs of a triple crisis, of international hegemony, of the financial system’s fragility, of the legitimacy of the traditional ruling classes. China, on the other hand, presents itself as a credible international competitor, despite continuing to suffer from a deficit in the attractiveness of its model of societal organization; a deficit that the effective management of the pandemic could – the conditional is a must – at least partially satisfy.

What remains unclear is the outcome of the transition, in particular a) the willingness of the current hegemonic power (USA) to “undergo” the transition without resorting to all the weapons, even the most destructive, at its disposal and b) the capacity of the emerging power (China) to escape in turn from the temptation of unilateralism and to remain, as it has in truth done up to now, on the terrain of multilateralism. This will be the subject of the political battle by all governments and all peoples in the immediate future.

II.

From a continental point of view, the process of European construction has never really recovered from the crisis of 2008 – 2012. In recent years we have entered a phase of relative stabilization, which, however, has not been able to stop Brexit (for the first time since the 60s integration loses pieces instead of adding them) and the widening of the cracks in the mercantilist and the basically hegemonic model imposed by Germany on other European nations. Even before the outbreak of the epidemic in Germany there was an alarming slump in investment, which threatened to drag down the weaker national economies, which were subordinate to the German-driven continental value chain. Also on this front, the pandemic had an acceleration effect on an already creaking mechanism.

If in 2008 – 2012 what held the EU together was the fear of the leap into the void and the loss of security, it is possible that in the 2020s, once the epidemic is over, there will be nothing left to lose, and not even the fear card can be played to hold together what remains of the dream of continental integration.

III.

Italy has never substantially emerged from the 2012 recession. Of the top 10 Italian companies measured in annual sales, 7 are publicly run. Big industry has outsourced to pursue favorable profits and taxation. Small and medium-sized enterprises, developed since the end of the 1970s as a response to the centrality assumed by labor conflict in the large factories and to the pressure exerted by the State on profits to finance the welfare system, has been exposed to the currents of a uncontrolled global market. Luxury and tourism industries are saved, while there is a low rate of value added in production. While the phenomenon of uneven territorial (“island”) development of the country is accentuated on a national basis, the question of underdevelopment in southern Italy is re-exploding in an even more pronounced and dramatic fashion. The pandemic has played the role of accelerator of dynamics already underway.

IV.

For more than a decade now we have been in a further phase of capitalist crisis. A crisis that concentrates wealth and centralizes command, which has redistributed the productive forces on a world basis and destroyed an important slice of the industrial framework in the West (and in particular in Italy), which has led to a substantial reorganization of work: diffusion of precarious forms of work and impoverishment of subordinate work and large segments of self-employment. The institutions have unloaded the 2007-2008 crisis onto society: they had managed – at the cost of draconian measures – to save themselves, a certain unity of the European political space, discharging tensions into the depths of society. By widening the income gaps in the working class, forming areas of underemployment as a safety valve for chunks of national capitalism that needed to reduce wages in order to stay afloat. This has happened a little everywhere, in Italy even more, for many reasons. Today this crisis rises from society to institutions, puts state apparatuses in crisis, reveals the real national interests behind the rhetoric of Europeanism as a salvation from nationalisms and opportunities for growth and solidarity, especially of those countries that basically have always used Europe for what they needed: a value chain functional to their own economy. In the crisis, the materiality of the power relations literally blows up the rhetoric that has concealed their disruptive scope.

V.

“Redemption” and “work” are two central concepts in a workers’ hymn written by Italian socialist Filippo Turati in 1886. Yet they are extremely current elements, perhaps because in many ways the present situation of work, its exploitation, its problems of inadequate representation, especially the lack of political representation are similar to the nineteenth century. For too long there has been no party in Italy that adequately represents Labor – in its concrete and contemporary articulations – starting from its material needs and interests.

VI.

Up to now, the work has been divided into two major segments: 1. the people of the Abyss, the Hell of precarious, poor, black market work and the gig economy and 2. “stable and guaranteed” work, incorporated and subsumed in the regressive company-territory block, that of hierarchical participation, of workers’ self- activation, of the factory-community (where conflict and autonomous representation of work is excluded), where the principle of collaboration, loyalty, sharing the values of the company and the market is in force.

How to reunite the people of the Abyss with the workers employed within the first circle of companies, that of permanent employment contracts, company benefits and welfare? How to reunite socially, as a union and politically those who live immersed in digital neo-Taylorism and those who live entangled in the pervasive Toyotism? This is the greatest political, anthropological and values challenge that a Left of radical transformation faces. An already complex and diversified reality that will have to deal now with scenarios further opened by the impact of the pandemic.

VII.

It is widely believed that the coronavirus pandemic will have significant repercussions on global economic scenarios. It will accelerate trends already underway such as the shortening of world production chains, will deeply question the cultural-tourist consumption sector as a driving force for capitalist accumulation, and will put at the center the role of the State as a lender and employer of last resort. The virus will impact the ways of organizing work. Among the many and sometimes unprecedented issues that the Covi19 emergency is posing for workers is the problem of remote work. Smart working would allow a more harmonious combination of work and private life, and, consequently, an increase in productivity. If a more or less imminent horizon of “governance” of the workforce focuses on the evaluation of results beyond the working time, very disturbing scenarios open up, which question both the “measure” of work and the keeping of the traditional division between working time and life time (already compromised or in fact made more fluid in many professions). Smart working, instead of agile and intelligent work, could in fact result in endless work. We are probably close to a paradigm shift, which must be dealt with, from a trade union and political point of view, by updating slogans – such as reducing working hours with equal wages – and tools.

VIII.

The discussion and confrontation with the Italian government on containment measures with respect to the spread of the coronavirus have revealed the fundamental importance of manual factory work in the production of wealth. The veil of propaganda on the “disappearance of the working class” deriving from the robotization and digitization of the economy collapses in the face of the same declarations by Confindustria (the main Italian Association of entrepreneurs), which claims the loss of 100 billion euros because manufacturing activities have been restricted to solely strictly necessary services. All this is the product of remote work and the productive decentralization of value chains and logistics itself, understood as an essential segment of the production cycle. In reality we already knew that worker labor (and non-factory manual labor) had not at all disappeared quantitatively even in post-Fordist economies, but now we have proof of how central and irreplaceable it is in the creation of value. There is always living labor at the bottom of the capitalist model of social production and reproduction It is necessary to start over from a new neo-laboristic representation of Work, its needs and interests, from its factory and artisan dimension, passing from manual non-factory labor, widening the perimeter to forms of juridically autonomous but economically dependent work: a social block that is in the field not only as trade union organization but also politically, as a guarantee of the founding value that the Italian Constitution recognizes as Work.

IX.

It is necessary to develop a point of view that contrasts the ideology of the end of history, reaffirming the historicity and therefore transformability of socio-economic formations; a point of view that reaffirms the usefulness also for the social and political initiative of an idea of different and better society, as it is in the tradition of the Italian workers’ movement, communism, socialism, environmentalism, feminism and the emancipatory policies implemented by the movements in recent years. As the tradition of socialism teaches, it is necessary to reactivate millennial aspirations for redemption at the level of organization, struggles, demonstrations, widespread acculturation, emancipation from degradation and physical and moral brutalization. Because, if the perimeter that you allow yourself is only that of the varieties of possible capitalism, only the purest capitalism in its brutality will always appear on your watch.

X.

There is a lack of a political project that puts work at the center of any reconstruction’s hypothesis, and that counts on workers, young women and men, the precarious and widespread intellectuality as new recruits for the creation of new leadership groups that are up to the challenge. The Italian Left, in all its versions, has revealed itself in the course of the crisis not ready for the challenge. Both from the point of view of analysis and tools.

XI.

The moderate Left has failed because the framework within which its project was built, that of neoliberal governance, has failed. The constitutionalisation of the idea that within finally pacified societies there are no conflicts, but “problems” to which to give “technical” answers. The era is over of thinking that “real globalization” was – and would continue to be – a factor of progress for the society as a whole, and above all for a middle class that was seen as the expression of the creative sectors of finance and culture, which were regarded as the pivot of national life and as structurally capable of profiting from the opportunities of an increasingly open world market. The PD (Italian Democratic Party), therefore, presented itself to the citizens as a post-ideological, post-national and post-class party, which would have effectively guided the inclusion of Italy in the global village, while at the same time ensuring the maintenance of acceptable welfare levels for the working classes to resist the growing insecurity of their jobs.

XII.

The political and social forces defined in various ways as the radical Left, despite having immediately criticized the regressive traits of globalization, have failed to represent at the mass and popular level either a credible alternative or a useful accumulation of forces in a phase of long resistance. The mantra of autonomy (from the moderate Left) has been elevated to dogma, while every hegemonic tension and every push for social and institutional change has disappeared.

XIII.

Basic processes such as those above described are the basis of the strength and popular roots of xenophobic forces with traits directly dating back to fascism such as those of the Lega (Matteo Salvini) and Fratelli d’Italia (Giorgia Meloni). The latest opinion polls, for the first time give a plurality to a political force (Fratelli d’Italia) that has claimed roots in the experience of Italian fascism. The immediate cause of this right wing surge can be attributed to the crisis of the second Giuseppe Conte government which united together PD, Movimento 5 Stelle (5 Stars Movement), part of the left and Italia Viva, personal party of the former Prime Minister and former Secretary of the Democratic Party Matteo Renzi.

The crisis caused by Renzi for that government (Conte 2), the most advanced possible, given the political and institutional situation, has led to a government of broad agreements chaired by the former President of the European Union Bank, Mario Draghi, with only the opposition of the right-wing party of Giorgia Meloni and left fringe groups. The wear and tear of the 5 Star Movement and the PD have produced three forces that, according to the voting polls, each amount to 20%, two of these are right-wingers (Fratelli d’Italia and Lega), who with the current electoral law could alone have the majority of seats in the Lower Chamber and in the Senate.

Despite Matteo Renzi’s split, with the secretariat of Zingaretti of the PD, coming from the experience of the PCI (Italian Communist Party), much less with that of Enrico Letta, coming from the DC (Christian Democratic Party) and former Prime Minister, the PD failed to reconnect itself with the world of work and with the popular classes, assuming the trait of a substantially liberal/neoliberal force on the economic-social level defining itself positively, albeit with many contradictions, on the level of civil rights. A polarity that does not affect the consensus of the Right on the world of work and that gives it, albeit in words, the identity claim of the defense of the national interest.

This is the opposite of what appears to be Biden’s orientation. Biden is aggressive in foreign policy, shows greater attention on the domestic level to give concrete answers to the world of work, especially with respect to the demand for social protection that has grown with the pandemic.

In Italy, the lack of a significant experience on a mass level such as that represented by Bernie Sanders, capable of putting back into circulation the word socialism and the classic themes of social democratic experiences in northern Europe, consigns the political life of the country to an alternative/alternation between xenophobic and fascist Right and liberal center that completely cuts out the material needs of millions of male and female workers, handing them over to electoral abstention or voting on the Right.

…

Living With Climate Change in Farmworker Communities

By David Bacon

According to Dr. Jessica Hernandez, a Zapotec scholar and board member of Sustainable Seattle, “indigenous peoples are the first impacted by climate change.” She points to the fate of the small municipality of San Pablo Tijaltepec, high in the Sierra Mixteca of Oaxaca, in southern Mexico: “Accelerated changes to our climate due to urbanization, fossil fuel industry, etc. continues to result in devastating impacts. The heavy rains that have recently taken place in Oaxaca, Mexico, have destroyed many of the harvests Indigenous peoples depend on. For the pueblo San Pablo Tijaltepec, their milpas [corn fields] were completely destroyed. This leaves 800 Mixtec families without the communal harvest they all depend on.”

Losing the milpas and harvest is a blow that falls on people already having a hard time surviving. The Mexican government says family income in the municipality averages about $500/month, leaving half its residents in extreme poverty. In 2020 only an eighth of San Pablo Tijaltepec had access to a sewage system, and over a tenth had no electricity. The region’s Mixteco-speaking people have been leaving and searching for work for decades as a result, joining the 400,000 who leave Oaxaca for northern Mexico and the U.S. every year.

In California’s southern San Joaquin Valley, the most productive agricultural region of the world, people from San Pablo Tijaltepec have created a new home, an extension of their Oaxacan community, in the small town of Taft. For over two decades they’ve worked as farmworkers in the surrounding fields. Here, instead of torrential rains, they face another environmental danger – the summer’s heat, which can rise to over 110 degrees in July and August.

The connection between climate change and increasing summer temperatures has been dramatized by the “heat dome” that covered the Pacific Northwest in July, leading to similar temperatures in a region accustomed to lesser heat. Portland had a high of 116 degrees. In the nearby Willamette Valley one farmworker, Sebastian Francisco Perez, died as he continued to work in the heat, moving irrigation pipes, in order to pay a debt to a “coyote” who’d smuggled him across the border. Scientists, and even President Biden, attributed the heat dome to climate change and its associated drought.

In the southern San Joaquin Valley town of Poplar, extreme heat in the summer is the normal condition in which people live and work. It is one of the poorest communities in the state. Air conditioning in trailer homes or crowded houses normally consists of old swamp coolers, which hardly lower temperatures. At work people bundle up, using layers of clothing to insulate against heat and dust.

Poplar’s families are almost all immigrants or their children, who have traveled here from other parts of Mexico, or have crossed the Pacific Ocean from the Philippines. Many now are older people, long accustomed to the heat. Yet for them the danger is greater as they get older. Some already have health conditions springing from poverty and the hard conditions in the fields. “In extreme heat, the body must work extra hard to maintain a healthy temperature,” cautions health journalist Liz Seegert. “Older adults are at higher risk for heat stroke, heat cramps, heat exhaustion and other serious health issues due to poorer circulation and less effective sweating that comes with aging.”

This rural poverty of the southern San Joaquin stands in stark contrast to the enormous wealth the labor of its people produce. Poplar’s Tulare County produced $7.2 billion in fruit, nuts and vegetables last year. Yet the average income of a county resident is $17,888 per year, compared to a U.S. average of $28,555, and 123,000 of Tulare’s 453,000 residents live below the poverty line. Poverty forced farmworkers to continue working during the pandemic. Tulare County’s COVID-19 infection rate was much greater, per capita, than large cities. A year ago Tulare had 7,603 confirmed cases, and 168 deaths. Heavily urban Alameda County had 9,411 confirmed cases and 167 deaths. But Alameda County’s population is 1.67 million, over three times that of Tulare County.

Photo Home and communities #6-10

These farmworker communities have fewer resources, but they are creative and resilient. Poplar’s Larry Itliong Resource Center holds vaccination clinics and campaigns for a park where people can find shade in the heat. Legal aid workers in Taft provide counseling about labor and tenant rights in indigenous languages like Mixteco. A history of farm labor activism in the San Joaquin Valley stretches back to the great grape strike of 1965, led by Larry Itliong, for whom the Poplar center is named, as well as Cesar Chavez, Dolores Huerta and others.

Rosalinda Guillen, director of the women-led farmworker organization Community to Community in Washington State, condemns the system of corporate agriculture for treating farm workers as disposable. “The nation’s farmworkers,” she says, “should be recognized as a valuable skilled workforce, able to use their knowledge to innovate sustainable practices. Most are indigenous immigrants and have the right to maintain cultural traditions and languages, and to participate with their multicultural neighbors in building a better America.”

…

Amazon? There Has to be a Better Way

By Wade Rathke

Amazon, we have a problem! Jeff Bezos may be going to the moon soon, but down here on terra firma unions are trying to organize and protect Amazon workers, and we seem to be the ones lost in space.

“… unions have not successfully organized a single mass employer with more than 100,000 workers in the US in the last fifty years.”

This is an old problem, not a new one, but somehow, we continue to try the same things over and over again, no matter how poorly they are working. This new problem may be Amazon since they have now grown to more than one million workers and rising globally. In the USA, Amazon is the second largest private sector employer behind Wal-Mart, but Wal-Mart is a prime example of the old problem. The old problem, simply put, is that unions have not successfully organized a single mass employer with more than 100,000 workers in the US in the last fifty years. Or, 50,000 workers. Or, 30,000 workers. Think about any of the tech conglomerates. Think about any of the massive fast-food chains from McDonalds or Starbucks on down. Think about the fact that all of the business successes of our generation have not been labor successes.

I’m not saying that our generation of labor organizers have been nothing but losers. We have won some individual campaigns with some huge employers, but not many, and certainly not enough, as the union density in the private sector continues to plummet towards 5%.

We have also had some significant successes. The homecare industry, for example, where density is estimated at more than 25% of the workforce and constitutes more than a half-million members in the giant Service Employees International Union alone. In many areas we have also done well in the home daycare industry.

“We have also continued to practice organizing models that are not designed to organize the emerging monopolies and mass employment enterprises of these times.”

There are a host of reasons for our failures. Labor law has steadily become more regressive, favoring employers in a quasi-legalistic environment that what is left of our political leverage seems unable to impact. State legislators have continued to advance so-called right-to-work provisions for both public and private sector workers. Courts at every level have eroded our strength. Those are the facts, but not to make excuses, we have also stepped on our own feet, crippling our progress and opportunity with curious positions on jurisdiction, insufficient solidarity, inadequate democracy, strange political alliances, and uneven attention and resources devoted to new organizing, membership maintenance, and rank-and-file actions.

We have also continued to practice organizing models that are not designed to organize the emerging monopolies and mass employment enterprises of these times. NLRA-based organizing models have fallen – or been pushed, depending on your perspective – to almost record lows in terms of number of elections filed. When filed, for decades success has been in units with less than 50 workers, hardly a mass organization strategy. Substituting leverage-based organizing models held promise but depended on targets where a confluence of factors was present: some level of unionization in key places in the industry; favorable local market conditions; and a reservoir of public and political strength to create additional pressure. Where all the stars did not align in this universe, success was still rare and, when it occurred, often unsustainable.

What can we learn from our successes in industries like homecare?

We do well as union organizers when we can offset the workplace advantages of an employer by organizing a mobile workforce without a fixed workspace. We do well when we can combine community organizing and labor organizing methodology that privileges home visits, leadership development, direct actions, political flexibility, campaign and research skills, as well as strong alliances. Sadly, that’s a tendency, not a model, because it cannot be applied by rote, but must be adapted in every arena, with every industry, and for every individual company. Nonetheless, this convergence strategy has much to recommend to unions and organizers when we look at mass employers.

With 1.6 million workers, organizers know that a straight-up NLRB-based election strategy is a loser with Wal-Mart. To have any bargaining power on that model, unions would have to believe that they could win certification at a significant number of the 5000 locations the company operates in the US. Organizing 2000 of them at a pace of 20 victories per year, when we have won none in decades, would still take 100 years, and remember, that’s to represent 40% of their workers, not a majority. In the meantime, as generations of organizers and leaders lived, worked, and died, while moving up the ladder to 40% there would be decades where our bargaining power was limited, assuming the company bargained at all and didn’t close the locations as fast as we succeeded.

Amazon is a different beast

With 960,000 workers – and rising – and 110 fulfillment locations in the USA, Amazon is a different beast. Amazon claims the average workforce in these warehouses is around 1500, so roughly 165,000 workers. There are a lot of other folks working in their tech centers, on the road as drivers and delivery people, in their data farms, and more, but the centers have been the heart of the targeting discussion along with the drivers. As we saw in Bessemer, Alabama, an NLRB-based strategy is challenged here as well. The individual bargaining units would be larger than Wal-Mart’s store-based units, but that doesn’t make them easier. Organizing 40% there might mean collective units that totaled 60,000 workers. Theoretically not impossible, but definitely improbable. The number of NLRB elections over 1000 workers is now miniscule. Bargaining strength, even if successful, would be strained, especially without their drivers being organized, which would be an even higher degree of difficulty since they are not place-based in the way a physical location is. The additional Amazon lines of business are also challenging when organizers think about pressure points and leverage.

There might be other ways, as organizers found when confronting the challenges of homecare workers over the last fifty years and organizing Wal-Mart workers fifteen years ago by combining community and labor methodologies. Unfortunately, these models take time, patience, and persistence, which are often in short supply in these times of crises in the labor movement, but to organize mass industries or mass employers, we may have to go long.

“… being able to be a rock in the road to the company’s expansion could be key in building leverage”

The Teamsters, according to their Amazon project organizer, are eschewing an election strategy, which is a good move. They are proposing a mixed bag of tactics, including strikes and boycotts. A boycott seems a stretch with a lot of work for little gain that would be almost impossible to measure and easy for the company to deny. Strikes would have to be something other than what we have seen in the fast-food “narrative campaign” with few workers, but we are talking about the Teamsters, and they do know how to organize a strike. They think community support will be essential to win. They also think being able to be a rock in the road to the company’s expansion could be key in building leverage. On those two counts, I heartily agree and our experience with Wal-Mart fifteen years ago gives credence to that theory.

In 2005, I left the SEIU International board to run an organizing project directed at establishing whether we could successfully organize Wal-Mart workers on a number of fronts. This was a joint project involving ACORN, SEIU, AFL-CIO, and UFCW. SEIU was developing the Wal-Mart Watch effort based in Washington, DC, and our effort was the direct organizing component, while the Watch was the web and media side of the air war. The UFCW also began a parallel effort called Wake Up Wal-Mart centered on a bus tour that organized meetings and small rallies around the country, largely around UFCW locals.

Geographically, we focused on the Interstate-4 corridor in Florida running from roughly Orlando to Tampa – St. Petersburg, encompassing about twenty-one counties. At that time, 4% of the total revenue for Wal-Mart was coming out of that area.

“We were able to maximize action on individual and collective issues using their “open door” policy and “grievance” procedures and through direct action at the stores.”

Strategically, there were three legs to the stool: workers, store-siting in the footprint, and blocking international expansion.

First, would Wal-Mart workers join a union? We organized the Wal-Mart Workers Association to directly engage workers in the corridor, enroll them in the union, collect dues, and take direct collective action on the job. We had a team of about twenty organizers, split between labor and community work. We triggered the drive by accessing the Florida voter list and pulling all phone numbers for families making less than $50,000 per year. We used a robodialer (this was 2005!) with a two-pronged message, leading with the question of whether they, or anyone in their family, had worked for Wal-Mart, and did they know that there were rights and benefits they might not have realized. If yes, then what was their address, and we would follow-up. We would winnow out the bad calls, and the organizers would be on the doors the next day to do the visits.

We were clear that we were building a union, but that we would not file for an election, and we would win through action and campaigns, and not collective bargaining. Members joined on that basis. We signed up almost 65% of all completed visits, which was the best recruiting percentage I had ever tallied in any other union organizing drive. Wal-Mart workers wanted to organize and were ready to join the WWA on the basis presented. We surfaced the organizing committee publicly in a press conference at the point that we had committees in more than 30 stores with support ranging from 5 to 40%. We had close to 1000 members in about six months.

After we first went public, there were reportedly 100 Wal-Mart operatives from Bentonville sent into the Florida stores to counter our efforts. They had individual and captive audience meetings for six to eight weeks. One of our leaders literally had a one-on-one meeting with a Wal-Mart labor relations guy every shift for over 50 days. After they could not find a card signing effort or any sense of a pending filing, Bentonville pulled them away. We were able to maximize action on individual and collective issues using their “open door” policy and “grievance” procedures and through direct action at the stores. We won some wage increases, reinstatements, and a slew of schedule changes, because the company was forced to empower local managers to counter our claims that scheduling was done by Bentonville, Arkansas computers. They fired no one, and we never filed an 8(a)(3) charge (National Labor Relations Act charge alleging discriminatory discharge). We pushed, and they bent.

The second leg of the stool was building a community-based organization in order to block Wal-Mart from building new supercenters. To engage that fight, we built WARN, Wal-Mart Alliance for Reform Now, as a broad coalition of unions, community and civil rights organizations (including ACORN chapters obviously), environmental groups, and civic associations in instances where they would be impacted by traffic and property values from new stores. In addition to the community organizing team, we supported this work with research reports that debunked the wages claimed by Wal-Mart in Florida (we were able to identify Wal-Mart workers from the way state unemployment data was sorted) and advance site location work. We found several experts at the University of Florida in Gainesville who specialized in developing algorithms to help stores determine future locations. They agreed to train our researchers, so once skilled adequately, we were able to determine in our target area where Wal-Mart – or generally any big box operation – would be likely to site a store for expansion. Another one of our team would reach out to every planning and zoning department in the footprint on a weekly basis to determine if there was any activity around these sites from purchases to applications.

We were able to nip some efforts in the bud. Others we had to fight from proposal to council hearings and in one case, in Sarasota Springs, through a direct ballot local initiative. We were able to bring police into the alliance because of traffic and safety concerns. We were able to bring property owner associations into the alliance in some cases on value issues. We blocked some permits on company efforts to build in wetlands and environmentally prohibited areas. During the life of the project within our footprint we blocked 32 straight Wal-Mart superstore expansion efforts. Using a community base and alliances, we were able to develop leverage we hoped would aid the organizing efforts.

Lastly, Wal-Mart had widely publicized that its huge growth in the future would be achieved by expanding in India, as it had done in China. Enlisting the support of the AFL-CIO Solidarity Center and to a lesser degree UNI Global Union, the international global federation, we quickly determined that any expansion in India would require amending the rules on foreign direct investment, which despite neoliberal revision in the country would still require modification because multi-brand retail was still restricted. We then organized the India FDI (Foreign Direct Investment) Watch Campaign, a coalition effort of unions, traders, hawkers, and others to oppose any changes in FDI for retail. It’s a long story in itself, but we were successful in blocking any changes for a decade, as ACORN continued to support the effort even after the unions had withdrawn support from the rest of the campaign. We had made promises, and they were meant to be kept. Even now, Wal-Mart has not been able to expand significantly in India and for them, or their competitors to do so, is very difficult since we were able to win significant concessions in the Parliament that the company still sees has prohibitive.

In this hybrid community-labor model applied to Wal-Mart, we established several things. Workers wanted a union and would join and pay dues, without any promise or prospect of an election or a collective bargaining agreement. We could stop expansion of Wal-Mart locally and internationally to build leverage on the company to support the workers organizing.

Nonetheless in the real politic of American labor organizing by 2008, SEIU and UFCW were involved in political and jurisdictional disagreements and part of the price of their trying to keep their alternative federation alive in Change to Win was their withdrawal from the project, forcing us to lay off most of the organizing staff. We were already at a juncture where we needed more lists to keep building and a deeper commitment, so this was crippling. We were able to keep some of the work alive for almost a year after that based on outside funding raised for the campaign. The work in India was taken over by ACORN International and absorbed as part of our Delhi office of ACORN India and continues to this day.

What does this say about other efforts to organize mass employers, like Amazon? Maybe nothing, maybe a lot.

When I met with Joe Hansen, then the president of UFCW, to give him a report on the work, I told him the good news was that we had succeeded on all of our main objectives, but the bad news is that for this model to work it would require a significant and long-term multi-year investment to get to 200,000 or more members, where the union would have enough power within the company to force de facto recognition and detente. It could take ten or twenty years, but it would work. He appreciated the point but wasn’t ready to go there.

A similar challenge faces any effort to organize Wal-Mart, or Amazon, or any mass employer. Organizers can fashion the strategies and tactics for almost any target. Workers will respond, if and when asked to act on their issues. Companies always have vulnerabilities that can be exploited.

Nonetheless without deep commitment – and pockets – to stay in it to win it, and the chance to adapt the organizing to what works and is most effective in the action and reaction of organization and workers to company response and so and so on, no plan will work no matter how good or well executed. Without that kind of commitment, it’s just dare to struggle without daring to win. Workers from time to time in different formations will be able to push Amazon and the others back in some battles, but won’t be able to win the war without putting all the pieces together and having the time and resources to engage the companies for as long as it takes.

…

Richard L. Trumka Sr. JULY 24, 1949 – AUGUST 5, 2021

By Robert Gumpert

Editor’s Note: This obituary for Richard comes by way of a group of friends and co-workers who worked in and around coal mining, the UMWA and labor starting as far back as the Miner’s for Democracy.

Richard Louis Trumka, 72, died on Thursday, August 5th, 2021. Rich, born on July 24, 1949 in Nemacolin, Pennsylvania, was a beloved son, father, grandfather, husband, friend, colleague, and leader. As the president of the AFL-CIO, Rich approached each day with a fierce passion to fight for others. When taking respite, he could be found in the great outdoors hunting, fishing, or camping with his family or with fellow members of the Union Sportsman Alliance. Rich helped usher a new generation of leaders through his service on the boards of the National Labor College, The AFL-CIO’s Solidarity Center, and The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, and many other groups. He also sat on the boards of the Economic Policy Institute and the Housing Investment Trust, and served as President Emeritus of the United Mine Workers.

Rich was preceded in death by his parents Frank and Eola (Bertugli) Trumka, his nephew Bryan Szallar, great nephew Bronson Szallar, his in-laws John and Katherine Vidovich, and brothers-in-laws John Vidovich and David Vidovich. Rich is survived by his wife Barbara, son and daughter-in-law, Rich Trumka Jr. (Jessica) of Olney, MD, sister and brother-in-law Francis Szallar (Alex) of McKees Rocks, his brother-in-law, Daniel Vidovich of Gates, his sisters-in-law Nella and Nancy, his three grandchildren Trey and Taylor Trumka and Ki Vidovich, and left to treasure his memory are his nieces and nephews, and his many other cousins. Friends and family will be received on Tuesday, August 10th from 6 to 8 pm, and on Wednesday, August 11th from 2 to 8 pm in the Behm Funeral Home, 1477 Jefferson Road, Jefferson, PA 15344, Gregory P. Rohanna, supervisor. On Thursday, August 12, 2021 at 11:00 am in the Jefferson-Morgan Middle/High School, 1351 Jefferson Road, Jefferson, PA 15344, there will be a public screening of the private memorial mass. Also a livestream of the mass can be viewed at: www.behm-funeralhomes.com or the AFL-CIO website: www.aflcio.org. In addition Mr. Trumka will lie in repose on Saturday, August 14, 2021 from 10:00 AM to 3:00 PM at the AFL-CIO Headquarters in Washington, DC, 815 16th Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20006. In the following weeks, a larger memorial service (details to be announced) will be held in the Washington, DC area. Masks will be required, and social distancing will be observed at all events. In lieu of flowers, please consider a donation to Penn State’s Scholarship Fund, which was started in Richard’s memory. The memo should reference: ‘Trumka Family Trustee Scholarship/ SCBTK’. The donation can be mailed to: Penn State Donor and Member Services, 2583 Gateway Drive, Suite 130, Bristol Place One, State College, PA 16801

DONATIONS

Penn State Scholarship Fund

Trumka Family Trustee Scholarship/SCBTK

2583 Gateway Dr., Suite 130, Bristol Place One

State College, PA 16801

Services

10 AUGUST

Visitation

6:00 pm – 8:00 pm

BEHM FUNERAL HOMES

1477 Jefferson Rd

Jefferson, Pennsylvania 15344

11 AUGUST

Visitation

2:00 pm – 8:00 pm

BEHM FUNERAL HOMES

1477 Jefferson Rd

Jefferson, Pennsylvania 15344

12 AUGUST

Live Stream of Private Mass

JEFFERSON-MORGAN HIGH SCHOOL

Auditorium

1351 Jefferson Rd.

Jefferson, PA 15344

14 AUGUST

Richard Trumka to Lie in Repose at AFL-CIO Headquarters

10 a.m. – 3 p.m.

815 Black Lives Matter Plaza (16th St. NW)

Washington, D.C.

Memories of Richard L. Trumka Sr.

Debbie O’Dell-Seneca

August 9, 2021

To the Trumka family,

My deepest sympathies to all of you on the loss of Rich. Such an inspiration! A man from the corner of Southwestern PA grew into a national leader who cared about people. I’ve known him since I became an attorney in the late 70s and he was always helpful, supportive, & kind to me and my family. One of my fondest memories was attending the 1984 convention with him, Lynn Williams, & Congressman Dr. Thomas E. Morgan. Thank you for sharing Rich with our nation and beyond. God bless.

Gwendolyn & Rev. Louis E. Ridgley

August 9, 2021

Extending heartfelt condolences to all that mourn the loss of this faithful, tireless “warrior”. Much that has been accomplished for members of America’s working class have been realized because of his many selfless efforts.

Gwendolyn O. Ridgley

Rev. Louis E. Ridgley, Jr.

Past Presidents

Fayette County (PA) NAACP

Ruth Stilwell

August 9, 2021

Like so many young labor leaders, Rich took me under his wing. He actively sought out women leaders in our movement to make sure we had a seat at the table. Our union was only 19,000 members, but he treated us the same as if we had a million. He did not make a show of it, he simply cared about our issues, our battle with the administration, the attacks on our profession and members were his battles. He made sure we knew that we were not alone in the fight, that the entire American labor movement had our backs.

My tribute on social media was simply this:

As I drove back to the office, I heard the news that Rich Trumka had died. I wasn’t ready for that. When I received my master’s degree, it was Rich Trumka that handed it to me. When I served on the AFL-CIO secretary treasurer’s committee, it was Rich Trumka that selected me. When I argued at the AFL Convention for seats for small unions on the executive committee, it was Rich Trumka that opposed me. When we were fighting to preserve our profession and our union against an administration that wanted to decertify us, It was Rich Trumka who counseled me. And when he was telling a story about his work at the Robena Mine, I asked my father if Uncle Frank knew him then. He told my dad, “I know Rich Trumka better than I know you, Rich Trumka saved my pension.”

Whether you knew him or not, whether you met him or not, if you are a working man or woman in America, Rich Trumka touched your life. His lifelong fight for fair wages and safe working conditions doesn’t end today, it is up to us to keep moving forward.

Rest my brother, you have earned it.

RONALD BROWN

August 9, 2021

Rich and I met at Penn State in the fall of 1968 when we both resided in North Halls. We were apartment roommates in 1970 & 1971. Rich traveled with me several times to my parents’ home in Shartlesville, Berks County, PA. I have attached 2 photos of Rich & I when he visited in 1970 or 1971 and also a photo of when he was an usher in my August 1973 wedding. We last got together in 1991 when he was still President of the United Mine Workers Union. Over the years after I often thought of contacting Rich but did not want to interrupt what I am certain was a very busy schedule with people of higher stature. As I approached retirement this year I thought about trying to reconnect with Rich when he retired, unfortunately that opportunity is now lost. We have lost a good common sense man who never forgot his roots. I truly regret not having tried sooner to reconnect.

My Condolences

Ron Brown

PSU Class of 72

Sosthenes Behn

August 9, 2021

I worked with Rich at the Nemacolin (Buckeye) mine. He was a dedicated hard worker. I met him briefly after he had assumed the leadership of the UMWA.

God Bless you Rich!

Jim Lavelle

August 9, 2021

REST IN PEACE, BROTHER!

Gregory and JanIs Kott

August 8, 2021

To the Trump Family,

We went to high school with Rick.

He was a home town young man that did so much helping others.

Our deepest sympathy for your loss.

Springfield, Va.

Bea Harris

August 8, 2021

I will always remember Rich as a visionary…. he saw how things could be and worked to see many of his visions come to life.

A great speaker and dedicated leader, Rich greeted everyone he met with a warm smile and a handshake..

I was privileged to work with the Baltimore AFL-CIO for many years, and always thought highly of Rich and his goals…..

Mary Kiger

August 8, 2021

Rich Trumka was the “local boy” that many grew up aspiring to be like . He came from a loving family and a loving town . Condolences to his family.

…

In 114 Degree Heat Farmworkers Are Still Working

By David Bacon

A sampling of headlines from June and July 2021

“Heat wave builds across West after hottest June on record in US” Washington Post

“Records torched as western US sizzles amid major heat wave” Washington Post

“Astounding heat obliterates all-time records across the Pacific Northwest and Western Canada in June 2021” Climate Gov

“The Record Temperatures Enveloping The West Are Not Your Average Heat Wave” NPR

In a field near Arvin, at the southern end of California’s San Joaquin Valley, dozens of workers arrive at 5:30 in the morning. It’s already over 80 degrees, and by midafternoon the temperature will top 114 degrees, according to my iPhone.

Is this heat normal? The southern San Joaquin is a desert like pan between the high Sierras and the Pacific Coast ranges, whose rivers have been diverted into giant irrigation projects. High temperatures are the norm. In 1933 the thermometer reached 116 degrees on July 27. The high this past July was 112.

In the summer, cars line the valley’s rural roads and highways, next to field after field. Even before daybreak, people stream from their vehicles into the rows and vines. By starting early, farmworkers can get seven or eight hours in before the heat reaches its peak. Most head home then, but some continue on, despite the temperature.

Farmworkers in the San Joaquin Valley have no choice but to treat the heat in a matter-of-fact way – laboring through the summer means survival in the rest of the year. Summer is the season with the most demand for field labor, so people get in whatever hours they can, hopefully saving enough money to weather the months when work is scarce.

It’s easy to pick up a bag of delicate small bell peppers in the supermarket, or lift a heavy watermelon out of the bin, without thinking about what it must have been like to get them from field to city in this summer’s heat. But in California, workers used to die from it.

In 2005, after four workers died from heat exposure, California began requiring growers to provide adequate water, shade, and rest breaks. But in 2008, 17-year-old Maria Isabel Vasquez Jimenez died from working in the grape harvest in 95-degree heat. That led to stricter standards and more enforcement. Nevertheless, at least 14 California farmworkers died of heat-related illness between 2005 and 2015.

A recent report by Vermont Law School’s Center for Agriculture and Food Systems, “Essentially Unprotected,” points out that only California, Minnesota, Washington and, most recently, Oregon have any requirements mandating heat protection for farmworkers. There is no federal heat standard, although unions have fought for one.

An article this year in the Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine warned, “Immigrant farmworkers will often suffer through [heat-related illness] rather than report it as they do not want to be fired for being perceived as a bad worker, lose income, or let down coworkers, especially if they are being paid by piece rate rather than by time.”

Yet, despite the heat, the immigrant workers in these photographs were out in the fields, laboring to provide the food for Los Angeles, San Francisco and the rest of this country’s cities, with their sweat earning the money their own families need to live.

…

This article and these photos first ran in Capital & Main.

We are encouraged to think like capitalists

By Maximillian Alvarez

“There are also less obvious reasons, which all of us—everyone who is invested in the mission of using independent media to change the world for the better—should reflect on.”

I’m not going to sugarcoat things: Progressive, independent media outlets like ours have made tremendous strides over the years, but in the aggregate, we are still getting our butts kicked by corporate and rightwing media. There are obvious reasons for this: one side is incredibly well funded by a host of powerful actors with a vested interest in maintaining the status quo, the other is not; one side has its coverage artificially boosted by black-boxed social media and search engine algorithms while the other is regularly downgraded or shadow-banned; etc. There are also less obvious reasons, which all of us – everyone who is invested in the mission of using independent media to change the world for the better – should reflect on.

Whether we’re talking about individual voices on social media or independent podcasts, YouTube shows, magazines, and multimedia outlets like TRNN, the digital media ecology’s built-in incentive structures train us to see ourselves as competitors in a zero-sum battle royale to secure our share of viewers, listeners, donors, clout, and so on. In short, we are encouraged to think like capitalists, to see others’ successes as our failures, and to greedily lord over our own personal fiefdoms of followers while the world continues to burn. This is the oldest trick in the book: divide and conquer. It is this every mindset that has pushed so many of us to fight with and clamber over one another in our daily lives to secure whatever scarps of wealth, status, and security we can for ourselves, all while the vast majority of wealth and power is concentrated in the hands of a few. In the world of media, the situation is no different: the more we are fighting and competing with one another, the more the powers that be are able to shore up their dominance. If we – all of us – are going to pose a serious threat to the power-serving propaganda machines that have been stoking imperialist desires to invade Cuba, fomenting manufactured outrage over “voter fraud” and Critical Race Theory, providing cover for police brutality, etc., we need to get serious about pooling our resources, bringing our respective audiences together, and working collaboratively. And that is precisely what we are doing here at TRNN.

In the first installment of our six-part video series of special reports on under covered political struggles in the state of Wisconsin, we premiered our documentary on rural Wisconsinites’’ fights to protect their communities against Big Agriculture and the factory farming industry. This video series is a testament to what we in the media (and all of you who support us) can achieve if we collaborate: By teaming up with In These Times magazine for their investigative series “The Wisconsin Idea,” we have been able to create something special together that neither of us could do on our own.

We at TRNN are making a concerted effort to get our amazing, committed, and talented team out there in the media bloodstream to engage in important discussions happening beyond the confines of our website, to share our work and critical perspectives with new audiences, and to send a message that TRNN is a collaborative hub for people around the world who are serious about building a better world. For instance, TRNN Managing, and Baltimore Editor Lisa Snowden-McCray published a stirring piece on Audubon magazine about the beautiful, necessary struggle for green spaces in Baltimore’s underserved neighborhoods. Jaisal Noor has been giving powerful and incisive interviews about worker cooperatives in the age of COVID-19 on a number of radio, podcast, and YouTube shows, including FAIR’s Counterspin and Means Morning News. I spoke with the great Jacqueline Luqman and Sean Blackmon about striking Frito-Lay workers in Topeka, Kanas (the interview begins around the one-hour mark). Eddie Conway dispensed more of his legendary wisdom on the This Is Revolutionpodcast, and Police Accountability Report hosts Taya Graham and Stephen Janis have been drawing much needed attention to the injustices of the US policing system and getting much deserved acclaim for their documentary, The Friendliest Town. We are out there, and we’re only getting started.

…

This piece is from the email newsletter of The Real News Network

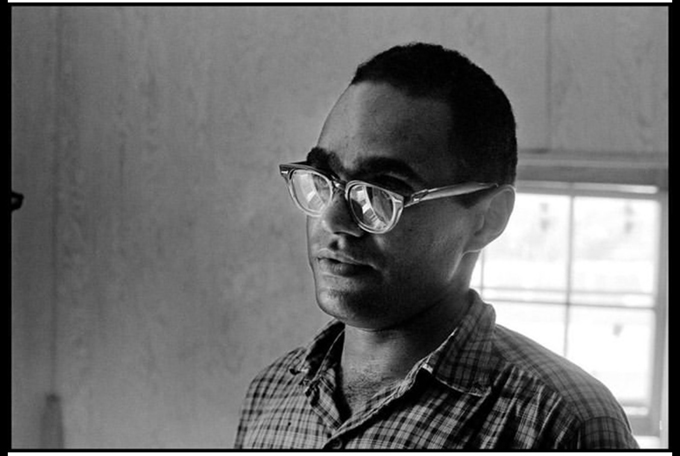

Bob Moses: 1935 – 2021.

By Mike Miller

“This is Mississippi, the middle of the iceberg…There is a tremor in the middle of the iceberg–from a stone that the builders rejected.”

Bob Moses, Letter from Magnolia, MS jail, 1962

An Unlikely Hero

In an age of plastic heroes, Bob Moses is the real thing—in large part because he did not want the role. In Mississippi, where his approach to organizing was born of a deep respect for “local people,” the work he initiated unleashed the talent, energy and power that is there waiting when small “d” democracy has the space to operate.

That space is called democratic organization: small “d” so that it is not confused with the American democratic myth that says when you choose between competing brands called political parties, and the products called candidates that they offer, you have a democratic society. “Organization” so it is not confused with the occasional uprisings of mass mobilization that take place when oppressed people rise in anger only to return to internalized anger when power structures fail to respond; or when voters massively turn out for the lesser evil (however real and necessary that might be) in the hope that it will be more. In SNCC, we thought “organization” is what we did while “mobilization” is what Martin Luther King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference did.

“… what Black Mississippians needed was the right to vote.”

Ella Baker, another genuine hero of The Movement, introduced Bob to a network of Mississippi African-Americans who in 1961 were leaders in local branches of the NAACP or independent local citizenship organizations seeking voting rights. To dare to attempt registering to vote was to put one’s life on the line, and to risk firing, eviction, foreclosure or other economic consequences.

Amzie Moore, one of those leaders in Cleveland, MS, admired the courage of young people sitting-in and engaging in freedom rides but he told Bob that what Black Mississippians needed was the right to vote. His view was repeated by others.

Wesley Hogan describes Bob’s local Mississippi introduction in Many Mind, One Heart (my additional observations are italicized):

…In July, 1961, when [Bob] Moses first arrived in McComb, Webb Owens, a retired railroad employee and treasurer of the local NAACP, picked up Moses and began making the rounds to every single black person of any kind of substance in the community. For two weeks, during each visit, Moses conversed with these leaders about his proposal to undertake a month-long voter registration project. Other SNCC staff would come to help, he promised, if the community raised money to support them.

At that point, Owens moved in as a closer. A smart, slim, cigar-smoking, cane-carrying, sharp-dressing gregarious man known in the community as “Super Cool Daddy”, liked and trusted by all, Owens solicited contributions of five to ten dollars [equal to $45 – $90 in 2021 dollars] per person. Before the rest of the SNCC staff arrived, the black community not only supported the project, it financed it as well.

Surfacing here is one of the central causal dynamics of the civil rights revolution in the South of the 1960s…Moses would approach a local leader—in this case, Webb Owens. He then listened to Owen’s ideas…

…Owens led Moses to all of the potential leaders in the community, in the process exposing himself to great risks as a local NAACP leader. When he extended himself on behalf of Moses and asked citizens to financially support a voter registration drive, things began to happen. The quality of the local person that you go to work with is everything in terms of whether the project can get off the ground, Moses later explained. The McComb voter registration drive would not have taken off without someone like Owens.

Too many discussions of “grassroots organizing” and “top-down versus bottom up organizing” ignore the lessons that are taught by Moses’ experience. Respected local leaders introduced him into the local communities in which voter registration projects started and asked the local community to financially support the work that Moses and other SNCC field secretaries were going to do. To the question, “Who sent you?” that might be asked of a SNCC worker, the answer was Webb Owens or Amzie Moore or CC Bryant or any of a number of respected local people who legitimized SNCC’s presence in their community.

Where that beginning legitimacy was lacking, the SNCC worker had to “earn the right to meddle” by gaining the trust of locally respected people. Field secretary Charles McLauren wrote a SNCC staff working paper on invited and uninvited organizers, and what the latter had to do to earn the trust that was the precondition for engaging local people in “Movement” activity.

An Organization of Organizers

Moses also recruited young people to become organizers and developed in them an understanding of the role that was controversial within SNCC. For Jim Forman, SNCC’s executive director, SNCC was an organization of organizers and itself a leadership organization, a “vanguard”. To use a spatial image, SNCC would be internally democratic as would groups it created, but it would be in front of a growing body of affiliates from across the south.

For Bob and his Mississippi full-time organizer recruits, SNCC was alongside. It was this understanding of the organizer’s role that created the space for people like sharecropper Fannie Lou Hamer to emerge as major Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party leaders. For the alongside organizer there is a continuing tension between, on the one hand, the greater vision an initial organizing effort offers and the belief in it that develops in its rank-and-file and secondary leaders, and, on the other, the egos and selfish interests that might emerge at various levels of leadership, and the realities of power relationships that necessarily force compromise upon the vision if it is to move forward.

The projection of local people led Bob to support the revival of the Council of Federated Organization (COFO), an umbrella organization in which the major civil rights organizations could develop a common strategy and implementation plan to break Mississippi’s iron wall of segregation. Under COFO’s auspices, the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) was created. These were necessary steps to advance the cause, though a deep sacrifice organizationally for SNCC which was providing 90% of the full-time staff in the state and would no longer be able to raise funds in the name of its Mississippi Project. The sacrifice was necessary. That’s how Bob thought.

The Mississippi Summer Project

The idea of bringing the country to Mississippi was circulating in the state as early as mid-1963. Let America see Mississippi for what it is and surely it will reject it and demand change was the underlying premise. Moses was quiet during the increasingly intense discussion that followed. Local people generally liked the idea. Many of SNCC’s young Black staff feared what the presence of an overwhelmingly White, elite-college educated, group would do both to local leadership and to their own roles. The fears were legitimate, and Moses didn’t want to lend his weight to one or another point of view.

Then yet another murder of a Black local activist took place. Louis Allen, witness to the murder by a state legislator of local Black leader Herbert Lee, initially told a lie that made the murder appear to be self-defense. Allen changed his mind and told the FBI that he would testify. Explaining why, he said, “I did not want to tell no story about the dead, because you can’t ask the dead for forgiveness.” Allen was gunned down on his farm.

The Allen murder ended Moses’ silence. He threw his considerable weight behind the Summer Project.

Just before completion of training for the second group of summer volunteers, three more Movement people were murdered: a Black Mississippian and two northern White volunteers. Moses addressed the volunteers, inviting them to go home if the news of these murders created any doubts for them. The accounts vary as to how many left, and there may have been none, but it was fewer than the fingers on one hand.

Later, Moses said of them, “[I]t turned out they had within them, individually and collectively, some kind of moral toughness that they were able to call upon. And God knows they needed it, because it was not just the Mississippi government, it was also the issue that the space in the Black community was really not a completely welcome space. There were some elements there which were welcoming them and bringing them in as family…, but then there was this resentment also, so they had to figure out how to walk through that. It is to their everlasting credit that they did.”

The Algebra Project (TAP)

How The Algebra Project teaches algebra to its students who had been tracked out of studying math in most of the schools they attended remains a mystery to me. To say the least, algebra is not one of my strengths. Bob once said to me, “anyone can learn algebra.” When I challenged him to teach me, we gave up because our time for humoring me had run out—a meeting beckoned. The evidence is that those who thought they couldn’t learn it can!

What I do understand is some of its core concepts, and they are really organizing concepts: begin with people’s experience; tap into their curiosity; engage them and their families in the process; go step-by-step, establishing self-confidence and building from one experience to the next. TAP makes demands on those who would participate in it: you have to do extra studying, including a summer. And you have to make demands upon the education system. The element of demand is central. Change comes from below.

TAP is also more complicated than voting. School districts, superintendents and “downtown” math divisions, principals, math department heads, classroom teachers and others have to buy in. Bob’s organizing talent put together a national organization of school people, including university math departments, school superintendents and districts, school reformers and others to pursue its goals.

Across the country, in Black inner-city schools and in Appalachian hollers, TAP is working. It contributed an appreciation of social class to Bob’s thinking that I don’t think was previously there. In relation to their education, he told me he didn’t see much to differentiate poor White students in TAP classes in southeast Ohio and those in Black inner-city schools.

His Meaning To Me

Bob was closest to me in age of the three people who most influenced my life as a community organizer. (The others were political theorist/longshoremen’s union leader Herb Mills, my best friend for 60 years who died in 2018, and Saul Alinsky, who died in 1972, for whom I directed a Black community organizing project in Kansas City, MO 1966/1967.) Bob was born in 1935, two years before me. Like me, he grew up in a public housing project—he in Manhattan, I in San Francisco.

We first met when he came to the San Francisco Bay Area on a fundraising tour I organized as SNCC’s field secretary in the area. We got to know one another better when I worked out of the Greenwood, MS SNCC freedom house during the summer of 1963. Dick Frey and I were the first Whites to be assigned to the Mississippi Delta. I got to watch him work up close.

Our friendship renewed when Bob started traveling with The Algebra Project. He came to the Bay Area where I connected him with local community organizations that were interested in getting TAP introduced in their school districts. He invited me to come to Broward County, FL where the school district was adopting TAP as part of its curriculum. We developed a plan for an organizing project that would organize parents and their communities; unfortunately it never got off the ground.

In 2012, I organized a trip to the Bay Area by Bob to raise funds for the defense of Ron Bridgeforth, a former SNCC field secretary who’d gotten himself in trouble with the law when he used a gun to steal materials for a Black children’s tutorial program and got in an exchange of shots with a cop who was attempting to arrest him. (Bridgeforth escaped and went underground for 40+ years. We’d been friends before that incident when he was still a SNCC worker.)

Bob often stayed at my place when he came to the Bay Area. We got to have serious discussions about the things we cared most deeply about. I got to know him as a person.

What stands out about Bob is the quiet that surrounded him—a quality of serenity that made him a rock of steadfastness no matter what turmoil surrounded him.

We think of charisma as associated with dramatic speeches made to tens or hundreds of thousands: Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., John L. Lewis and other great orators. Bob’s charisma was different. He spoke softly, often using questions to get others talking with each other in small groups and listened carefully. But there was no question: when he was in a room, he was usually the center of attention.

For Bob, there were no nobodies. That created a deep bond between him and sharecroppers, day laborers, domestics and other otherwise nobodies in the dominant culture. The other side of this coin was that nobody intimidated him: not a Mississippi sheriff with a gun pointed at him or U. S. Senator Hubert Humphrey trying to persuade him of the honorary at-large two-seats “compromise” at the 1964 Democratic Party Convention.

Bob imagined a national constitutional amendment making education a right like voting and promoted the idea across the country when possibilities for ideas like that still seemed real. And he could return to a Mississippi classroom to teach his new algebra to make sure that it worked. The global and local were always interconnected in his theory and practice.

Bob, rest in peace. The country is a better place because of your presence. I miss you.

…

Power Despite Precarity: How Contingent Faculty Organizing Can Succeed in Higher Education

By Steve Early

“Adjuncts need to develop the “capacity to speak as an independent collective voice within whatever over-arching organization” they choose to affiliate with.”

Despite recent organizing gains among some contingent faculty members, the adjunctification of higher education has left hundreds of thousands of college and university teachers with low pay, spotty benefit coverage, and little job security. As former adjuncts Joe Berry and Helena Worthen report in their new book, Power Despite Precarity: Strategies for the Contingent Movement in Higher Education (Pluto Press, 2021), an estimated 70 to 80 percent of all contingent faculty in the U.S. still lack union representation.

The rapid, pandemic related expansion of on-line education threatens to further erode employment conditions for the two-thirds to three-fourths of all faculty members who are contingent. (For an analysis of OLE and its impact, see Robert Ovetz’s “Conscious Linkage: The Proletarianization of Academic Labor in the Algorithmic University,” New Politics, Summer, 2021.) In the next few years, Berry and Worthen predict, “the institutions of higher education will be more globalized, more on-line” and “and most will try to eliminate tenure and universalize contingency.”