“A Shave and a Haircut”, A User’s Guide to Door Knocking

By Nelson Perez-Olney

Last year I spent two weeks canvassing in the general election in Arizona and another three weeks canvassing in the Georgia Senate run-off election.

I’d canvassed before for local candidates in the San Francisco bay area, but never for more than a few hours maybe one, two Saturdays out of the year. On those more local campaigns the only thing I can really say I learned is that most of the time when you canvass people are not home.

But if you canvass every day for weeks at a time, you soon come to realize that there is more to it than knocking on doors that probably won’t open, dropping a flyer and moving on. You will have conversations with voters, far more than you might expect. You will have tense encounters with people who don’t want you in their neighborhood. You will probably get lost down unfamiliar streets. You will get caught in the rain. You will have someone threaten to call the cops on you.

I’m no expert on political campaigns or messaging or the strategic decisions that go into figuring out a ground game. But I have walked plenty of doors and definitely gotten into the nitty gritty of getting out the vote. I’ve seen how powerful talking to a voter face to face can be and how important it is to reach out to people in person. I worry that too many of us think a campaign can be won on advertising and the power of a sound political platform alone. That if people hear a candidate say the right things and seem competent that will be enough to send them to the polls. But often it’s much smaller things that keep people from voting for candidates. Sometimes they need practical information like where their polling place is or how they can register for an absentee ballot. Sometimes they don’t realize that just because they’re a felon doesn’t mean they can’t vote. Sometimes they just need someone to remind them every day that they are planning to go early vote this Friday, at 4pm, at the church on Greyson highway, and that their sister will be watching their kids while they vote. Sometimes they don’t realize that today is the last day to vote and they only have 2 hours left to cast their ballot! And sometimes they just need to see that someone has come from thousands of miles away to knock on their door and personally ask them to make sure they cast their vote because both of their futures hang in the balance.

So I’d like to share a few tips for new canvassers or people who have never done it before. I hope that in reading them you will get a glimpse of what political canvassing is really like and be inspired to give it a try.

The Door Knocker’s Tip Guide

First and foremost, understand why this election, this candidate, this issue is so important to you.Maybe it’s because your brother lost his health insurance and is worried about what will happen to him if he’s hospitalized with COVID, or any unforeseen event. Maybe someone in your family needs to be paid more than our paltry excuse for a minimum wage. Maybe you’re afraid that when your kids think about going to college the thought of high student debt keeps them away. Whatever your reason, keep it close to your heart. Not only will it give you the motivation and courage you need to walk for 6 hours a day, 7 days a week, talking to total strangers whose reactions to your politics you cannot predict, but your reasons are a reflection of your humanity. If you present your humanity to the person in front of you, they are far more likely to engage with you and feel solidarity.

Spend more time studying the ins and outs of voting than candidate platforms. You want to be an expert at helping people vote. Learn the voting schedule in the state you’re canvassing. Learn how to find polling places and how to register for absentee ballots. Learn how a properly filled out absentee ballot looks, where it has to be signed, how much postage it needs. Learn how to track the status of a ballot. Find out how to get a voter to the polls if they have a disability. The majority of the people you talk to are going to want to talk logistics, not politics.

Learn to use your cell phone. For those of you who haven’t canvassed since the days of paper voter sheets, you will probably be rather intimidated by the new programs being used today to track conversations with voters. You might be frustrated at first, wondering who in their right mind would think flipping back and forth between different apps is easier than a simple clipboard and pencil. But cell phones offer far more tools for the modern canvasser than sheets and sheets of paper. They streamline access to voting information, to maps, to vote tracking websites. Information you can pass directly to the voter by texting or emailing them on the spot. It’s hard enough to have a natural conversation. Don’t add fumbling around with loose papers to the mix. Which leads me to…

Backpacks. Carry one. Have your water, your hat, your sweater, your extra literature neatly stored where it won’t get in the way of your hands. The fuller your arms are the less relaxed you will betalking to a voter. I encouraged newer canvassers to assume a posture at the doors that makes you feel confident and empowered. Having your hands free while you talk helps you seem human and less like a dispassionate salesman.

Ignore no soliciting signs. People seem to forget they put those in their windows and rarely give you grief for ringing their doorbell.

Study your script. The script you are handed on your first day is a wonderful outline of all the key points you need to go over with a voter. Have they voted? Who are they voting for? Do they know their polling location, or do they plan to submit an absentee ballot? What’s their plan for getting to the polls (date, time, method of transportation)? You might walk away from a door thinking you had a great conversation with a voter about when and where they plan to vote, only to realize you forgot to ask if they were even supporting your candidates. The script will tell you every question you need to ask.

Ditch your script. Its awkward. It’s wordy. It’s probably not how you normally talk. If you try to recite your script, you’ll probably get tongue tied. If you try to read your script (even worse than reciting) you will come off as cold and impersonal, unenthusiastic. Also, its inflexible. If you’re relying on the script only to find that your voter is deviating wildly from it, you’re going to have some really awkward conversations if you try to stick to canned lines. Make the script your own. Think about what information it seeks and put that in your own words. Be flexible. Canvassing is about connection. Connection is about conversations. Good conversations are never scripted.

Gated communities are not inaccessible. Drive in after another car. Walk in when someone opens the gate walking out. Just make sure you have your team lead on speed dial. It’s possible someone might try to get you kicked out, but sometimes they can be talked down. I had a very pleasant conversation with a security guard while his boss argued with my supervisor about my right to be there. In the end he bid me good day and drove off. We’d share a friendly wave whenever we passed as I continued to canvass his residents.

Knock that door. Don’t tap. Give it a good rap with your knuckles, or else use a hard object that won’t damage their door. Houses are big and a timid tap could easily get lost beneath the sounds of the washing machine or kids playing. Ring the bell too. I mean, you want them to know you’re there, don’t you? Also, instead of three solid knocks equally spaced, try a “shave and a haircut”. You don’t want people thinking you’re the cops.

Your voter is not their demographics. Don’t assume because your voter is Black or Latino that they’ll vote Democrat. Don’t get freaked out that you’re probably talking to a Trump supporter because your voter is a fifty-year-old white male with a pickup truck in the driveway. Let the voter speak for themselves and try not to be surprised by what they say. You’ll get better at this the more doors you knock.

Be excited. If you positively ID your voter as supporting your candidates, celebrate right then and there. I like to dance a little, or else raise my fists in victory, which usually brought a smile to the voter’s lips. If you’re having fun, the voter will have fun and will probably be more willing to plan their trip to the polls with you.

Compliment voters on their dogs, their Christmas or Halloween decorations, or the giant gong they have instead of a doorbell. If you like Star Wars and the voter has an R2D2 t-shirt on ask them whether they thought “The Last Jedi” made any sense. It’ll help you find common ground and relax.

Don’t give the voter an out. If you ask, “Can you spare a moment to talk about voting,” they’ll say “No, I’m busy,” or now isn’t a good time. Instead ask “Have you voted for (whoever/whatever you are working for) yet?” Don’t ask “can I have your phone number to follow up with you on your vote plan?” Instead say “I’m going to text you the voting plan we just discussed. What’s your phone number?”

Don’t get stuck talking to undecided voters. Ask them to share what’s important to them and what their concerns are. Make a connection on those concerns. Share similar concerns of your own and say why you support progressive candidates and a progressive agenda to address those concerns. But don’t spend too long with them. If you spend half an hour with an undecided only to have them not shift at all, you could very well have wasted your time. You have other voters to talk to who will be more committed to your candidates but who could use a little help finding their polling place or navigating a specific impediment to voting. Let the undecided mull over your discussion. Let them think about what it meant that you came to their door. Get their phone number. Text them later when you have time. Keep the connection alive. But don’t wait around for them to change their mind.

Get the voter’s phone number. This may seem like a very bold ask, but it’s very important. If you text a voter reminders about a specific vote plan you discussed together, they will be less likely to forget to vote on the appointed day. Voters are busy people. Be a helpful reminder. And if they need help with something in the future, like figuring out why their absentee ballot hasn’t arrived yet, or needing to know what form of ID to bring to the polls, you can be an easy point of contact for them. Also, if you have their number you can create accountability. Tell them to send you a selfie with their “I voted” sticker. Or a shot of their entire family going to the polls. Or they can send a pic of themselves putting their absentee ballot in the mailbox. I know, it seems crazy, but it’s actually pretty effective and voters seem to enjoy it. Who doesn’t like sharing an awesome selfie? Plus, it’ll give you a boost to see people proudly following through on their promise to vote.

Don’t argue with voters. If the person is spouting QAnon theories you should thank them for their time and walk away.

Take time to regroup and breath if you had a tough door. Give yourself time to rest. You don’t have to be a perfect canvasser all the time. And don’t carry the bad door with you to the next door. The only people who know you messed up are you and the last voter. Each new door is a chance for a new first impression.

Always remember that canvassing is really hard work. You may knock eighty doors in a day, talk to only twenty people, fifteen of whom actually support your candidates, five of which have already voted, another five of which aren’t willing to tell you more than that they support your candidates. If among those last five you’re able to have inspiring conversations, help folks find their polling place, or create vote plans then you’ve had a pretty good day. This work is about getting votes one by one. Your job is to add a few drops a day to the growing wave.

…

For hope, look South

By Nelson Perez-Olney

A few years ago I went south on a whim, booking a plane ticket to Dallas and a return flight from Atlanta, giving myself two weeks to make my way across a part of the country I’d never visited before. I rode the Greyhound across the rolling hills of Texas, the forested highways of Tennessee, the moonlit interstates in Georgia. Along the way my trip gained purpose and meaning. What started as a vague stirring to see the lands indelibly branded SLAVE STATES became a solid plan to visit as many monuments and museums documenting a struggle (past and present) for the soul of the United States. Maybe it’s a California boy’s prejudice, but down there I could not but feel as if the ghosts of that struggle were to be found around the next street corner, behind the trees and veils of Spanish moss. Nowhere else has that history felt more alive to me.

Our country was reckoning very publicly once again with police violence against African Americans. Efforts to remove the confederate flag from state buildings and debates on tearing down confederate monuments were in full swing. The day before I arrived in Dallas, five police officers were killed by a sniper during a peaceful protest against the killing of Alton Sterling. I arrived in New Orleans the day after protesters spray painted “Justice 4 Alton Sterling” across the base of a monument dedicated to Robert E Lee.

Here was the land where the seeds of racism and oppression were so deeply sewn and where they manifested in their most horrific forms. Here a building where slaves were held before being sold. Here the stop where Rosa Parks boarded a bus in Montgomery. Here the plantations that grew rich off slave labor. And here Fort Sumter, the first battle ground of the civil war.

Here was the motel where Martin Luther King Jr. was killed.

Even the very busses I rode had their own story to tell, having once ferried freedom riders towards angry crowds and roadside terrorism.

Surrounded by so much evidence of oppression, past and present, it’s easy for those of us not from there to feel like the South will forever be backwards. Forever be that massive red block at the bottom of the map, intractable in its conservatism, an anchor dragging along the ocean floor. A place unworthy of hope.

Four years later I returned, this time for the Georgia Senate runoff election.

And just like last time I came without really thinking much about the greater significance of where I was and why I was there. I thought only of the race’s political importance in the present. I’d gone to Arizona to campaign for Biden in October and I wanted to complete the victory with a win in Georgia. I wanted a democratic agenda to have a fighting chance in Congress.

What came to me later was what the election represented in the arc of American and especially southern history.

On Christmas Day I met a fellow volunteer canvasser in Selma, Alabama and together we walked across the Edmund Pettus bridge. Here, in 1965, marchers including the late John Lewis were beaten and tear gassed by local police while protesting the exclusion of blacks from the polls. It seemed a fitting pilgrimage for those of us who had come all the way to Georgia to join in the long fight against voter suppression.

On New Year’s Day we had the privilege of a private visit to the legacy museum in Montgomery, Alabama, only a two-and-a-half-hour drive from Atlanta. The museum is built into a warehouse that once held slaves. And though tiny it is packed with an overwhelming and stunning display of the ways in which this country did and does wrong by millions of its people. From slavery to mass incarceration the museum documents how the oppression of blacks has evolved over the centuries. And of course, it spends considerable time recounting the terrorism used to keep blacks from exercising their civil rights, voting.

Not far from the museum is the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, a haunting tribute built for the over 4400 African Americans lynched to preserve white supremacy. Metal blocks etched with the names of the murdered and the counties in which they were killed hang from the ceiling, grim stand ins for brutalized bodies. On the walls are some of the “crimes” committed by the dead: filing a lawsuit against local whites, being the relative of someone the lynchers were looking for, not addressing whites with the right words.

Voting

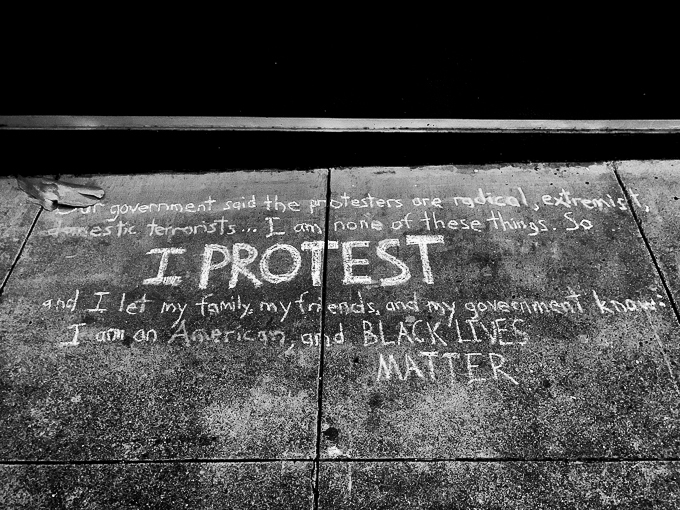

This month two Democrats won the Senate seats in Georgia, their campaigns triumphing over a runoff system designed to favor white segregationists, the purging of voter rolls that disproportionately affected the black community, stringent voter ID and signature match laws, the closing of polling places in Democrat leaning counties, and onerous barriers to voting for the formerly incarcerated. It took record turnout and continuous voter registration drives. It took lawsuits against voter purging. It took years of coalition building between many different communities. It took favorable demographic shifts. It took a failed gubernatorial campaign. It took what felt like the entire ground game of the general election descending on one state. It took voters waiting in dauntingly long lines to cast their ballots. It took every last ounce of patience from an electorate who’d had their doorbells rung and phones called multiple times a day for months and months and months as Stacey Abrams encouraged canvassers to “irritate the dickens out of them.”

In short it took maximum effort and commitment on the part of grassroots organizations, campaigns, volunteers and voters alike. They weren’t just fighting against Loeffler and Purdue, Kemp and Trump, they were fighting the segregationists of the mid-twentieth century, the white mobs of Jim Crow. The legacies of the Civil War and the system of slavery it sought to end.

Georgia On My Mind

So here is the tonic for those who despair of overcoming the weight of that history. Yes, the South is the land of the Confederacy, of slavery and Jim Crow. Home to some of the most egregious acts of oppression ever committed. But that legacy belongs to all of the United States. Every part of this country, north south east and west, owes its origin and wealth to our “peculiar institution” as well as other less notorious programs of government sanctioned/ignored exploitation and murder of the poor, immigrants, women. But growing up many (perhaps most) of us learned to identify the South as the repository of all blame. A place we can dismiss with a wave of our “clean” hands. Somewhere we can mark on the map and say, “here there be backwards, unreasonable people.”

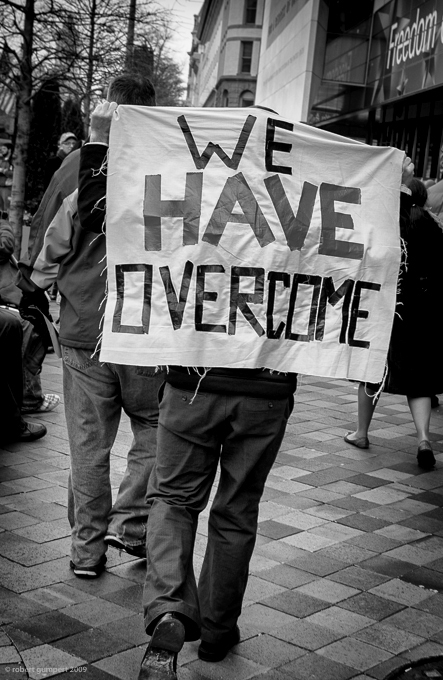

Yet in doing so we also dismiss the effort it took to bring the South to this moment. We dismiss the courageous resistance people mounted in the face of the segregation juggernaut. We dismiss the sit-ins, and marches, and court battles, the voter registration drives and public disobedience. We dismiss the planning and organization and face to face conversations and human connection. Georgia remembered those lessons. Georgia acted on those lessons, and when many northern states failed to reject Trump, Georgia did.

And then did it again.

The joy of this victory is tempered by the reality that all it delivers is some breathing room for Joe Biden. It is hardly the foundation for a strong, progressive agenda. But it is instructive for those of us on the Left who have mostly stayed out of the political and activist fray. In a year where the blue wave predicted by pollsters and demographics failed to manifest, Georgia offers a vision of how to turn polling numbers into votes.

For hope, look south.

…

The Face of the Insurrection

By Harris Gruman

Following coverage of the storming of the Capitol, I was transported back to a summer day in 2016. There I confronted the face of what is now being called a mob, a riot, an insurrection. During the dark days of the Trump presidency, I recalled this encounter over and over. Even as it haunted me as a worst-case scenario of alienated extremism, it provided a glimmer of hope.

It was in Utah, between visits to National Parks. I was in a laundromat at 1:30 on a weekday afternoon, washing our hiking clothes – a weird time to be in an empty laundromat in a mangy strip mall along the highway that ran through town, but that’s travelling. Empty, that is, until an athletic young man came in with a basket of what looked like mostly toddler’s clothing.

He was angry, banging things around, mumbling irritably. Not the most comforting companion, but I kept reading my paper.

Then he began speaking for my benefit. He was on a political tirade about that [B-word] Hillary Clinton and our [N-word] president. I now saw him clearly, close-cropped blond hair, late twenties, solid and trim. My responses, facial twitches and grunts, were non-committal. Do they have concealed carry here in Utah? Why are these machines so slow?

He was a veteran of Afghanistan and Iraq, three tours in all, and now he was unemployed, doing the washing while his wife worked down the road at Wal-Mart. The Democrats only cared about transgendered people and immigrants. Trump was his choice.

“My uncle in Wyoming thinks we should kill President Obama.” That tripped my fuse.

I leaned forward. “Soldier, that’s treason!”

For the first time, his face lost its combativeness. “Yeah?”

I explained my point in neutral, yet forceful Civics 101 terms. For the first time we were making eye contact. The conversation turned to the wars he’d seen. We both discussed them with a dispassionate eye to their dragging pointlessness. He was impressed with my knowledge of the history and situation; he probably didn’t meet many civilians who were daily readers of the “New York Times”.

Like so many soldiers before him, of whatever ideological stripe, he resented those who sent him there, and even more, those who had forgotten him since. The [F-word] “politicians.”

Now he was back on his plight and his grievances. They wouldn’t even hire a guy like him at McDonalds, because “they have all the Mexicans they can use, never mind they can’t speak English.” This went on for a while, as I returned to contemplating the slow progress of the dryers.

Suddenly he asked, “What do you do?”

“I work for a labor union.”

He released a long audible sigh. “God, I wish I had a union job!”

A new image arose, displacing the mad militia uncle, Wal-Mart and McDonalds, villainous politicians. I heard about a father who worked for the railroad, a member of the Brotherhood of Railroad Brakemen. Family life, economic security, pride. Could his dad have even voted Democrat? Did it even matter then?

And was such a thing still possible?

Back in 2016, I met a face in the rioting white supremacist crowd of January 6th, 2021. Yes, he was a racist. Yes, he was resenting people even worse off than himself. Yes, he was far too ready for murderous violence.

But don’t talk to him about white privilege (save that for people like me) or label him “a deplorable.”

Get him that union job.

…

THIS MOMENT

By Stewart Acuff

This is a huge moment in our country’s history for many reasons: the fascist assault on our democracy, undeniably evil and unstable president, the nation changing victories in Georgia, and more.

Huge events all.

But I believe this moment is most critical in our long struggle for racial justice.

I think and deeply believe it is root and branch time for racial justice. Root and branch is an old country saying about clearing land for crops as in–we will fell the timber, clear the land down to every root and branch.

It is time for us to do that to white supremacy and white nationalism.

It is time for us to get on our knees working to root out every vestige of oppressing people of color, especially Black people who’ve suffered their own unique hell in American history.

Black people and our children have been leading us to fundamentally challenge this disease on the nation’s body.

Now it is so clear what white supremacy costs us, the evidence so compelling. The domestic terrorists who assaulted our democracy for the president were all motivated by race hate.

The Violent Right is in a race war against a democratic, pluralistic, diverse, just society.

I could write for days and nights about the awful ramifications of race hate, including deluding much of the working class.

It is now very clear our nation is under internal assault in furtherance of a racial civil war.

All of us, especially us white folks got to get serious about rooting out racism.

I’m not talking about understanding one another or getting along or charity or even working together.

I mean the hard and dirty work of fighting white supremacy and nationalism with intent to destroy it root and branch.

I mean defending Black people, fighting against mass incarceration, official brutality, and fighting the Radical Right .

I mean taking leadership from Black people, supporting Black candidates, buying Black.

I mean destroying white supremacy.

…

Georgia Shows the Way, D.C. Shows the Stakes

By Editors Organizing Upgrade

This is a statement from the Editors of Organizing UpGrade, we at the Stansbury Forum thought it important to share.

Over the last 48 hours, we’ve seen a stark picture of the two paths that lie before us: a racial justice democracy or white authoritarianism. On Tuesday, a multi-racial working class bloc took to the ballot box to elect Rev. Dr. Raphael Warnock and Jon Ossoff to the Senate in Georgia. That the movement was led by Black voters, and that long-term organizing in communities of color to build independent political power played a crucial role in the victories, was no coincidence: the struggle for racial justice has always been central to the defense of democratic rights in the U.S. With Democrats now in control of the Presidency and both chambers of Congress, progressives have a significant opening to push the Democratic Party to expand our democracy and deliver material relief for working class people of all races.

But yesterday, we saw an anti-democratic, insurrectionary effort inside and outside the halls of Congress to overturn the results of the election. A dozen Republican Senators and 60 Representatives attempted to block the democratic process using arcane legislative maneuvers inside the Capitol before their violent allies stormed the building in a desperate attempt to achieve the same anti-democratic ends.

It may appear at first that the divisions within the Republican Party represent a turn to sanity. But in fact, even those Republicans opposed to a coup support voter suppression. They too want apartheid, but with a democratic cover. The split within the GOP should be widened if possible, but we cannot be lulled into seeing one wing as an ally. And within the Democratic Party, the fight for all to support racial justice and a fully inclusive democracy is far from won.

It is no accident that those storming the Capitol are carrying Confederate flags. They are launching a new round of the Civil War many have been fighting for decades: a war to return to full and open white supremacy and limited democratic rights.

We will need to remain vigilant in the days leading up to the inauguration and support movement’s calls to deal with white supremacist terrorism and the instigation of violence by Trump and his enablers as the anti-human, criminal acts that they are. The broad front we built in defense of democracy will need to stay together and grow further to create the conditions for us to fight for the future we need.

As Calvin Cheung-Miaw argued in “The Pivot of U.S. Politics: Racial Justice and Democracy,” our path is clear: we must continue to build at the base, fighting for a true inclusive democracy that this country never achieved.

…

An update from Calvin Cheung-Miaw of

Armed Trump supporters stormed the Capitol on January 6, and forced the Congress into lockdown. Five years ago, this would have been unthinkable. Today, nobody – however worried – can claim to be genuinely shocked.

How did we get here?

In the aftermath of the 2016 presidential election, commentators debated whether Trump’s supporters were motivated by racism or by declining economic fortunes. It’s difficult, however, to assign a single overarching motivation to such a large and heterogenous group of voters, which included former Obama supporters and enthusiastic white supremacists, denizens of the Rustbelt, survivors of the opioid crisis, and the high-toned Republicans of Greenwich, Connecticut.

Politics is not just about aggregating disparate groups to achieve greater numbers, however. It’s also about cohering and transforming those groups into a new social force. This was Trumpism’s project: to take a social base riven with contradictions, and reshape it in some crucial ways. First, Trumpism demanded fidelity to the personal fortunes of Trump above those of any other principle, scruple, commitment, or even the GOP party. Second, Trumpism sought to filter supporters’ understanding of the world through a set of frameworks — Sinophobia, Islamophobia, the rhetoric of law and order, anti-immigrant sentiment, anti-communism, conspiracy theories — that together reinforced racial inequality, patriarchy, and national chauvinism. This was all undergirded by the broader commitments of the GOP to delivering policies favoring untrammeled corporate power, appointing a judiciary that delighted right-wing evangelicals, rolling back civil rights protections, and – crucially – the willingness to hold onto power through white minority rule achieved via mass disenfranchisement.

In his four years in the presidency, Trump – assisted by the peculiar dynamics of social media and mass media – has been wildly successful in cohering and refashioning his social base. And no matter how disastrous we thought this development was, each week seems to prove that we actually underestimated the dangers it poses.

TURMOIL AND ESCALATION

After November 3rd, Trumpism’s demand for fidelity to Trump above all else has become the subject of fierce contention within the GOP. As Trump promoted the theory that the election had been stolen from him, indifferent to the pandemic exploding through our communities and unconcerned with the details of vaccine distribution, the top echelons of Republican leadership tried to usher Trump off the stage without a direct confrontation. Until January 6, this strategy was an utter failure. Rather than fade into the background, Trump has escalated his attack on the election, organizing a portion of the Republican party and a significant chunk of his base into being openly and explicitly the faction of overthrowing democracy. The armed mobs storming the capitol at Trump’s behest as I’m writing this are, of course, one face of this faction and certainly the most dangerous. The other are the politicians who are intent on discrediting the results of the election through more proper channels. The general anti-democratic thrust of their politics constitutes a weapon, one that is already being used by the Pennsylvania GOP state senators that have refused to seat a Democratwhose electoral victory was certified by the Pennsylvania Department of State.

This faction is opposed by another faction of the party, which has broken with Trump over the election results. The tradition of a peaceful transfer of power is of huge importance to major sections of the ruling class both ideologically and in terms of the ability to project U.S. soft power internationally. And most of the high echelon corporate capitalists in the GOP seem to have decided that allowing right-wing populists who have a base outside their control is not in their long-range interest. They would prefer to regain “institutionalist” control over the GOP and retain actual elections as mechanisms to resolve their internal differences. They are signaling (via such things as Mitch McConnel’s wife Elaine Chao resigning from Trump’s cabinet and a call for Trump’s immediate removal by the National Association of Manufacturers that they may make a real bid to reassert their primacy.

Whether these divisions will intensify into a de facto split in the Republican Party or will get patched over is not yet determined. Trump’s present factionalists in the GOP are motivated by personal opportunism, to be sure, but we can also expect them to try to tamp down (for the moment) the wildest actions of their militia and thug wing and turn the momentum behind “Stop the Steal” into renewed efforts to implement stricter voter ID laws, roll back vote-by-mail access, reduce the number of polling places in communities of color, and execute mass purges of the voting rolls. Most of the GOP politicians and corporate leaders who are currently denouncing Trump will be eager to join them if they believe the Q-Anon/Proud Boy current that surfaced under Trump can be pushed out of the limelight. It is not out of the question that most of the GOPers now fighting one another could coalesce around an alignment that preserved the GOP as an expression of white nationalist authoritarianism and all-wealth-to-the-1% economics but dispensed with personal loyalty to Trump as a defining characteristic.

That kind of joint effort to bolster white authoritarian rule would be matched by enormous funds poured into campaigns targeting voters of color in the hope that a segment can be won over to a right-wing populist worldview, enough to secure the party’s political fortunes. And however the divisions in the right play out, we are likely to see a ferocious campaign of “anti-communism” by the entire GOP against even the most modest reforms proposed by the Biden administration, with more and more politicians condoning – as Rep. Chip Roy has recently – the idea that we are effectively in a state of civil war.

HOPE AND CHANGE

When I wake up in the morning, the first question I ask myself is, “What do we need to do to stop a red wave in 2022?” A key part of our strategy has to be winning concrete improvements in people’s lives. The struggle against the right, the struggle for racial justice and democracy, needs to be intermeshed with the pitched battle to deal with the immense suffering in our communities, a battle over who will pay for reconstructing society in the wake of the carnage wrought by the pandemic.

The victories in Georgia – the fruits of a decade of effort by determined community organizing, largely rooted in communities of color – mean we have a chance to make some headway in this fight.

We still, however, face the fact that the anti-right front is heterogeneous, and the class and ideological differences pose a challenge for us being able to win the kind of bold changes we need right now. And it’s not at all clear what politics Biden is going to try to lead with.

So what do we have in our favor?

First, through the last two decades, social justice forces have grown in sophistication and capacity. This is how we were able to make an impact on the presidential election, and on the runoff elections this week. And it may allow us – if we move quickly and boldly – to take advantage of the right’s current divisions and neutralize or win over the portion of their supporters. More than a few are genuinely shocked at the storming of the Capitol by Trump supporters carrying Confederate Flags and wearing Auschwitz Camp t-shirts; others are newly open to the argument that rather than caring about their economic hardships, Trump has been running a personal-benefit con game all along.

Second, we have on our side our people’s longing for freedom and dignity. We’re still in the jaws of a crisis – of health, of housing, of hunger, layered on top of racial oppression, which will surely produce a wave of resistance. We are in the midst of a decade of upheaval – and we know that when people’s demands take the shape of mass protest it has the possibility to reshape the balance of forces and reset the agenda within the anti-Trump coalition. That’s what gives us hope.

Parts of this article draw from a talk the author gave to volunteers of Seed the Vote. Many of the ideas here originated in conversations between the author and Whitney Maxey. The author thanks Marcy Rein and Max Elbaum for feedback on an early draft.

…

FRED HIRSCH – DOING THE WORK THAT NEEDED TO BE DONE

By David Bacon

Fred Hirsch, born in 1933, died on December 15, 2020 in San Jose.

When Adriana Garcia heard about his death, it was a blow. “The whole South Bay is hurting,” she mourned. Garcia heads MAIZ, a militant organization of Latina women in Silicon Valley. For many years she and Fred co-chaired the annual May Day march from San Jose’s eastside barrio to City Hall downtown.

The recovery of May Day was one of the great political changes that took place during Fred’s lifetime. May Day commemorates the great demonstrations in Chicago in 1886 for the eight-hour day, and the execution of the Haymarket martyrs a year later for leading them. When Fred became a political activist and Communist in the 1950s, the holiday had become virtually illegal, a victim of Cold War hysteria. It was called the “Communist holiday,” celebrated everywhere in the world but here.

Fred grew up in New York, where police on horseback attacked the May Day rally in the city’s Union Square in 1952. They clubbed down mothers with strollers who were holding signs calling for justice for Willie McGee, a victim of legal lynching in Mississippi. Years later it was no surprise that Fred helped organize a local support network for the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee. SNCC fought the racism and political repression in the South that killed McGee, and its courageous student activists helped end the dark years of McCarthyism.

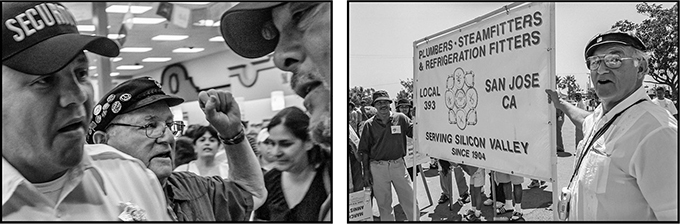

Even by the 1970s, fear of redbaiting still kept most delegates away from the May Day events Fred would organize among delegates to the Santa Clara County (now South Bay) Labor Council. In 2006, though, everything changed. Millions of immigrants chose May Day, a holiday they knew well from back home, to pour into the streets, protesting a law that would have made it a felony to lack immigration papers. Tens of thousands marched in San Jose. In the years that followed, when Fred and Adriana asked unions to come out for May Day, they’d bring banners and arrive by the busload.

“He viewed his long activity, not as the work of one person alone, but as the product of a history, of a set of ideas, and of a collective of people fighting together”

To Fred, May Day wasn’t merely a radical symbol. It was a chance to connect union and community activists in San Jose to people far beyond the country’s borders, and to talk about a shared set of politics. Making those connections, seeing the world joined by the bonds of a common class struggle, was the thread that ran through Fred’s politics throughout his life.

I interviewed Fred not long before his death, to understand the political history of Silicon Valley, and his own work that helped shape it. Because Fred had been a “big C” Communist for most of his life, and a “little c” communist to its end, he viewed his long activity, not as the work of one person alone, but as the product of a history, of a set of ideas, and of a collective of people fighting together.

‘LITTLE OCCURRED SPONTANEOUSLY’

“A thread runs through Santa Clara Valley’s history of labor and community organizing,” he explained, “from the days of the canneries up through the heyday of industrial production in the high tech industry. Very little organizing or political activity occurred spontaneously. There was always a small group of left-wing, class-conscious, Marxist-oriented workers who met regularly, exchanged experiences, and planned campaigns.

“It was not one single group. New people came in and others moved on. Many simply got old, retired and died. Through much of the time an important strand of that thread was the Communist Party and the many friends with whom its members worked. But other groups with similar left ideas also organized and sought to influence people.”

Fred spent his working life as a plumber and pipefitter, after joining the union in New York in 1953. Being in the union brought political responsibilities – to defend it and the labor movement, and at the same time to fight for politics that represented the real interests of workers. At 20 that meant opposing the Korean War, calling for peace with the Soviet Union, and opening the union’s doors to Black workers. The local’s leaders told him plainly that once he passed his apprenticeship, they wanted him out.

He left New York with his wife Ginny and migrated to California. Leftwing politics kept him from getting work in Los Angeles as well, so they moved north. In San Jose Fred still faced redbaiting, but Communists hadn’t been driven out of the local labor movement and their presence helped the family survive. Fred also knew that survival depended on winning the respect of the plumbers he worked with. In a tribute to him after he’d been a member of United Association (UA) Local 393 for 50 years, Fred was called “a good mechanic” – plumber-speak for a worker who knows his job.

Transforming the labor movement – making it not just more militant, but anti-racist and even socialist – was the ever-present idea. Sometimes it meant organizing a trip with other unionists to show support for newspaper strikers in Detroit. Sometimes it meant going to Colombia to expose U.S. support for a murderous government and paramilitaries out to obliterate the union for oil workers. Sometimes it just meant showing up at a farmworkers boycott picket line in front of Safeway, in his VW van full of copies of the Communist newspaper, the People’s World.

Transforming the labor movement was part of Fred’s hope when he, Ginny and their daughter Liza moved to Delano in 1967, after the grape strike had been going on for two years. “The work they were doing in Delano,” he later remembered, “led me to hope that one day farmworkers could stimulate a transformation of our rather moribund AFL-CIO into a real labor movement. It seemed achievable. The organization of ill-fed, ill-housed, and ill-clothed agricultural workers, who truly had ‘nothing to lose but their chains and a world to win’ could change the shape of the workers’ struggle in California. Farmworkers, in their hundreds of thousands, could potentially provide a model of workers’ power that could lead organized labor into a new and militant era.”

Fred was physically courageous, and was beaten by foremen and strikebreakers as he went into fields, ostensibly to serve legal papers, but in reality to organize. Having been roughed up in his own union by fearful and angry right-wingers, someone should have told the scabs it would only make him more determined, and it did. But even in Delano he faced redbaiting, when the leaders of the then-called United Farm Workers Organizing Committee wouldn’t give him a real assignment. He called it “an anti-ideological hand-me-down from the prejudices of Saul Alinsky.”

But soon he was working with older Filipino workers, the “manongs,” chasing railroad cars shipping struck grapes out of Delano and the San Joaquin Valley. In order to track their movements and stop them, “We were to call a special number and report our whereabouts to our Filipino brothers, who would move pins on the map to follow the progress of the grapes.” In these old men Fred knew he’d found veterans of decades of strikes in the fields, going all the way back to the 1930s. He also knew he’d found a group of workers, Communists among them, who despite their age brought radical politics into the early United Farm Workers.

POWER COMES FROM THE BASE

Fred always had his eyes on the workers at the base of any union. He pinpointed early on the problems in the UFW’s structure that would ultimately weaken it. “There was a weakness in what I saw in Delano,” he recalled later, “that kept gnawing at me. Yes, the workers were getting organized, but they were not necessarily organizing themselves.” Fred’s politics inherited a set of principles from the Communist, socialist and anarchist traditions in the U.S. labor movement – that the power in the union comes from workers at the base who should control it, and that the more politically conscious those workers are, the greater capacity for fighting the union will have.

Finally, he and Ginny left Delano when Robert F. Kennedy won the union’s support for his presidential campaign. Fred later acknowledged that if Kennedy hadn’t been assassinated, the union would have won crucial support it needed in Washington. But he and Ginny remembered Kennedy as an aide to Senator Joe McCarthy, and later as the author of deregulation that destroyed much of the power of organized truckers. Even though Liza was later brutally redbaited and purged from the UFW, Fred continued to support the efforts of farmworkers themselves. “The UFW helped shape the life of our family,” he said. “Whatever its failings or accomplishments, it nurtured and developed a generation of organizers and activists who continue to make a positive impact on trade unionism and the political life of our nation.”

ORGANIZING IN THE COMMUNITY

Back in San Jose Fred was a key organizer of the huge upsurge of the civil rights and anti-war movements that transformed the politics of the Santa Clara Valley. His comrade-in-arms was Sofia Mendoza, who with her husband Gil and other Chicano community activists in the San Jose barrio began organizing against the Vietnam War.

The first of the student blowouts, which helped launch the Chicano movement, took place at San Jose’s Roosevelt Junior High in 1968. That led to student walkouts in Los Angeles, and eventually to the huge Chicano Moratorium march against the Vietnam War up Whittier Boulevard. In San Jose the movement began organizing marches on City Hall, and formed a committee to stop police brutality, the Community Alert Patrol(CAP). “The police had guns, mace and billy clubs,” Mendoza remembered. “They were always ready to attack us. It seemed as if nobody could stop what the police were doing.”

But CAP did stop them. Its members monitored police activity, much as the Black Panthers were doing in Oakland, documenting police beatings and arrests. Students organizing for ethnic studies classes at San Jose State University became some of CAP’s most active members, at the same time fighting to get military recruiters off the campus. CAP had the participation of Communists, socialists, Chicano nationalists and other leftwing groups.

Sofia, Fred and others believed San Jose needed a multi-issue organization to confront the many problems people faced in the barrios – discriminatory education, lack of medical services, poor housing, and of course the police. “We wanted an organization that was not limited to one ethnic group, that would organize our entire community,” she later recalled. “We called ourselves United People Arriba – United People Upward -because it got the idea across that people from different ethnic backgrounds were coming together in San Jose to work for social change – Blacks, Mexicans, Puerto Ricans and whites working together in one organization.” Today Silicon Valley De-Bug’s Albert Covarrubias Justice Project, the community organizing of Somos Mayfair, and the Services, Immigrant Rights and Education Network all carry on the legacy of CAP and UP Arriba.

In 1972 Angela Davis, African American revolutionary feminist and then-leader of the Communist Party (CP), went on trial in San Jose, charged with kidnapping and murder, accused of providing the guns used by Jonathan Jackson in an attempt to free his brother, George, a leader of the Black political prisoners’ movement. Davis’ historic acquittal was the product of an international campaign that succeeded because a strong local committee mobilized support. Ginny Hirsch, assisted by Fred, researched every person named as a potential juror, work that ensured the jury included people open and fair about the prosecution’s false accusations. This kind of community research has since become a powerful tool in other trials of political activists.

FIGHTING DEPORTATIONS

The South Bay’s first fights against deportations began with the government’s effort to deport Lucio Bernabe, a cannery worker organizer. His defense was mounted by the American Committee for the Protection of the Foreign Born, put on the Attorney General’s list of “subversive organizations.” Further fights against raids in Silicon Valley electronic plants like Solectron, and garment factories like Levi’s, led Fred and other activists to oppose the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986. Although the law provided amnesty to undocumented people, which they supported, activists warned that the law’s prohibition on hiring workers without papers would lead to massive firings and attacks on unions. The law also reinstituted the hated “bracero” contract labor program, which Fred’s compañeros Bert Corona and Ernesto Galarza had fought all through the McCarthyite years.

In fighting IRCA, Fred challenged the AFL-CIO’s support for the bill, along with other beltway advocacy groups in Washington DC. They argued that if undocumented people were driven from their jobs and couldn’t work, they’d go home and leave the jobs to “us.” Fred and his cohorts lost the battle when the law passed in 1986, but continued to organize until they succeeded in 1998, when the AFL-CIO reversed its position, and called for amnesty and labor rights for immigrants. When similar immigration bills were introduced in years afterwards, Fred again defied the liberal Washington DC establishment and supported instead the Dignity Campaign for an immigration policy based on immigrant and labor rights.

UNMASKING AFL-CIO/CIA TIES

In 1973 Chileans began to arrive in San Jose, and Father Cuchulainn Moriarty made Sacred Heart church on Alma Street the resettlement center for those who fled the fascist coup. Enraged, not just at the CIA’s organization of the coup, but at the deep complicity of the AFL-CIO’s International Department, Fred wrote one of the most damning exposes of its work, “An Analysis of our AFL-CIO Role in Latin America, or Under the Covers with the CIA.”

In just a relatively few pages, he did more than document the sordid history of the AFL-CIO’s support for fascism in Chile. The small pamphlet became the tool used by leftwing labor activists for many years, in the long struggle to cut the ties between the U.S. labor movement and the anti-communist intelligence apparatus of the government.

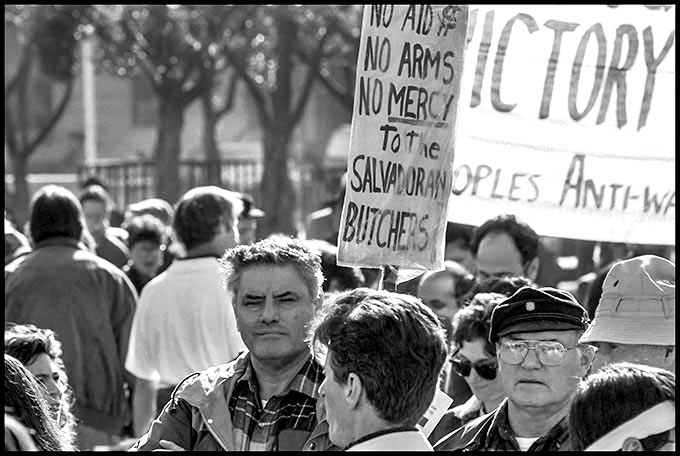

It was a long fight. In 1978 the first Salvadoran Communists and trade unionists appeared in San Jose, looking for help after the U.S. supported the Salvadoran government, and trained its death squads at the School of the Americas. It was the beginning of the Salvadoran civil war, and over the next decade two million Salvadorans sought refuge in the U.S., ironically, for what the U.S. itself was doing to their country. The first Salvadorans fleeing the death squads deployed against unions in the late 1970s sought out the Hirsch home on 16th Street. To expose what had made them flee, Fred and his comrades organized the Labor Action Committee on El Salvador, a forerunner of CISPES, the Committee in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador. Their work was so effective that when they invited Salvadoran leftwing trade unionists to come to the U.S. as guests of the South Bay Labor Council, the AFL-CIO’s president George Meany threatened to throw the council into trusteeship.

Mexican miners came north during a bitter strike at the huge Nacozari copper mine in Sonora, finding money and friends in San Jose. Fred went to Colombia and came back with another long report. He told labor council delegates, “I’m a retired plumber who’s been around the block a few times. I’m not easily moved, but in Colombia I saw a daily life reality I’d only glimpsed before, mostly in nightmares … We have to stop sending our taxes and soldiers to protect corporate interests in Colombia.” And when unions were pressured to supporting President George H.W. Bush’s invasion of Iraq, he responded by convincing his plumber’s local to send money to start U.S. Labor Against the War.

These were all solidarity actions from below, not only intended to provide support for workers themselves, but to show to the members of his own union the consequences of the actions of U.S. corporations, and the imperial system from which they profit. In Fred’s way of organizing, solidarity was a way to help his fellow pipefitters understand that the unions of Mexico, Chile or El Salvador were their true allies, and to reject the idea that unions here should defend a system that attacked them.

These were all solidarity actions from below, not only intended to provide support for workers themselves, but to show to the members of his own union the consequences of the actions of U.S. corporations, and the imperial system from which they profit. In Fred’s way of organizing, solidarity was a way to help his fellow pipefitters understand that the unions of Mexico, Chile or El Salvador were their true allies, and to reject the idea that unions here should defend a system that attacked them.

ORGANIZATION IS VITAL

Fred was not a voice in the wilderness, however, speaking out by himself. He saw a common interest between immigrants and native-born, between workers of color and white workers, between unions in the U.S. and those around the world. He never stopped trying to explain that class gave them something in common, and he found effective ways to convince white workers in particular that fighting racism and imperialism was in their own interest. Whether organizing for a progressive immigration policy or for solidarity with leftwing unions in El Salvador, Colombia and Iraq, he brought his own union’s members with him, along with delegates to his labor council, progressive elected officials, and many others.

Fred supported every significant social movement that arose in the South Bay for over six decades, but he never believed that a spontaneous upsurge would suddenly defeat capitalism. He believed in organization, not just of unions and communities, but of political activists. For many years he thought those activists could find a political home and education in the Communist Party, and an organization capable of planning a lifetime struggle to win socialism. At the end of his life he was no longer sure that the party was that organization, but if not the CP, some organization would have to play that role, he thought.

“It would have to have a clear focus on a socialist and democratic future in a world without war,” he told me at the end of our conversation. “It would have to fight injustice in our communities and worksites, our nation and our planet, promote serious education about the process for social change and organize people to take to the streets.”

Real revolutionaries in his beloved labor movement, he thought, need to band together to fight racism and sexism “all through the institutions and culture of our society.” And in doing all this, they should be humble, willing to do the work that needs doing, and glad to take leadership from the people around them. In short, Fred wanted “an organization like the Communist Party we dreamed and worked for so many years ago, but more effective than we were. Without it wonderful working class leftists will continue making enormous efforts to build progressive movements that ebb and flow, but won’t develop a strategy and build a base of their own.”

In the outpouring of messages from activists hearing of his death, it was apparent that plenty of people had absorbed Fred’s ideas. Virginia Rodriguez, the daughter of farmworkers and a lifetime labor organizer like him, passed away before he did. But she shared his confidence in a vision of an ongoing core of politically committed activists. “I came to believe,” she said, “that there will always be those individuals who will respond to the outer edges of what needs to be done, and who will step forward to take up responsibility for what is called for if change is to take place. In so doing, these people help move others to come along. It underscores the principle that if enough of us carry out a piece of what needs to be done, then change will most certainly come.”

.

Thanks to the Farmworker Movement Documentation Project for preserving the memories of Fred Hirsch, Virginia Rodriguez and many others of their experiences working with the United Farm Workers.

All photos and copyright: David Bacon

…

This tribute and remembrance of Fred Hirsch is being published jointly with our friends at Organizing Upgrade, a great site to checkout.

Evictions and the Road To Homelessness

By Harry Brill

Because national and local anti-eviction laws will expire on December 31 million tenants could face eviction. According to the Census Bureau 11.6 million tenants would not even be able to pay their rent the following month nor their mortgage payment if they are homeowners. Particularly troubling, the number of tenants struggling to meet their obligations has been increasing in the last several months,

The major problem is not only that the coronavirus is impacting people’s lives. Also, many millions of working people are being deprived of their livelihood. Particularly worrisome has been the considerable increase in long term unemployment. Just recently the number of workers unemployed for at least six months has tripled in one month from 1.2 million to 3.6 million. This huge jump is very rare and also quite ominous.

Could it be the dark cloud before the thunderstorm? Perhaps, because too many job seekers are crowding the job market. So even working people who have been fortunate enough to have a job have been forced to accept lower pay. Among the consequences is that a larger percentage of their income must be allocated to paying rent.

“In Los Angeles county 600,000 residents spend 90 percent of their income on rent.”

How much rent is just right? We have been told that affordable rent is about 30 percent of income. But this rule of thumb certainly does not apply to poor tenants because it would yield very little to the landlord. But unfortunately for tenants, the high rents that property owners charge leaves very little to renters.

According to researchers, a substantial number of poor tenants must pay at least 80 percent of their income to retain their apartments. In Los Angeles county 600,000 residents spend 90 percent of their income on rent. Clearly, the high rents do not leave much, if anything, for food and medical expenses. And since almost two thirds have children, their low income can be very problematic and even dangerous.

Moreover, when tenants face eviction they are often summoned to court. Think for a moment of the legal obligations of the judge. It is not their job to put pressure on the landlord to charge a more reasonable rent to protect the health of the tenant. Instead, their task is to do what they can to compel the tenant to meet financial obligations regardless of the adverse impact on the well-being of the family.

Some evicted tenants may have family members, friends, or an available facility to provide shelter to evicted families. But most tenants are not so lucky. And of course, for the same financial reasons they were evicted, they are unable to pay the rent for another apartment. So it is not surprising to learn that eviction is the main reason why evicted tenants are homeless.

What we have learned about the connection between eviction and homelessness is very disturbing. According to research in Seattle, 37 percent of evicted tenants are homeless. Also, according to the US Census Bureau, 26.4 percent who were interviewed claimed that they were unable to pay their rent.

The number of individuals and families living in the streets is substantially larger than the public realizes. That’s because of how the statistics are often reported. For example, according to a report on homelessness 12 percent of the residents in New York City are homeless. That doesn’t seem like much unless we know how many residents the 12 percent encompasses. So, it may surprise you that aside from those who live in shelters every night 4,000 New Yorkers live on the streets, in the subway system, and other public places.

Although the problems of the homeless are immense, it would be a serious mistake to assume that the rest of us are thriving. As a result of the downward slide in the economy and other nasty problems, there is a growing number of Americans who are in serious trouble. Since June almost 8 million Americans have joined the ranks of the poor. Cutbacks in government spending is part of the problem. It is immensely important that the government change its course by developing and funding programs that will improve the standard of living and the quality of life of all of us.

A good beginning is to pay serious attention to the advice and wisdom of Bernie Sanders. Unlike proposals that the federal government is seriously considering, which are both ungenerous and temporary, Bernie’s proposals seek to make both substantial and permanent improvements in the political landscape.

First, Bernie proposes that the federal government enact a federal program that guarantees stable jobs to everyone who wants to work. As Bernie correctly notes “There is more than enough work to be done in this country”.

Second, Medicare for All should be adopted as soon as possible. As Bernie notes, it would not only save billions of dollars that are paid to the private sector. It would prevent 68,000 unnecessary deaths a year.

Third, Bernie wants to guarantee housing as a human right and to eliminate homelessness. It would be paid for by a wealth tax on the top one-tenth of one percent. Don’t you agree that those who have a net worth of at least $32 million can afford it?

Clearly, we need to act on Bernie’s proposals. Words are not enough. So as Bernie insists “LET’S DO IT”

…

On the Sidelines: DSA’s Abstentionism on Biden vs. Trump

By Peter Olney and Rand Wilson

Both the Stansbury Forum and Organizing Upgrade felt it important to maximize the exposure of this piece and are co-publishing.

The results are in: Trump was defeated and Joe Biden will be sworn in as the 46th president on January 20, 2021. This victory is the product of a broad, popular united front. Popular, because there was an alliance of cross-class forces that opposed Trump. United, in that these forces agreed on a shared objective – electing Biden and Harris – to remove him from office. In such a broad front, the reasons for uniting to throw out Trump were varied. Many were offended and outraged by his anti-democratic rhetoric and conduct. He repulsed millions with his overt racist, jingoist and sexist behavior, and his cultivation and encouragement of white supremacists.

Activists in the labor movement saw his attacks as weakening our already feeble bargaining power and ability to fight for our members. Regulations protecting everything from air quality and wilderness areas to labor and occupational health standards were gutted. The left clearly understood that four more years of Trump and his deepening authoritarianism would make it nearly impossible to realize progressive reforms like Medicare for All, a Green New Deal and the much needed labor law reforms proposed in the Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) Act.

The heroes of this election victory are the thousands of grassroots political activists who busted their butts to defeat Trump by working for Biden, particularly in the key battleground states. Thousands of our comrades in the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) and other socialists worked side-by-side with leaders and activists in black and brown organizations, women’s organizations, and labor unions like UNITE-HERE and SEIU. Because of our collective participation in this struggle to elect Biden and Harris we have forged new or deeper ties with organizations and individuals open to discussion and struggle over the way forward in the future Biden administration.

Few, if any, of the comrades we campaigned with had illusions about the reality of who Biden actually is or what he represents. They can recite chapter and verse his personal flaws and long history of complicity with the neo-liberal project. Nevertheless, there was a broad understanding that Trump had to go — and that our efforts would be key to an electoral victory.

BERNIE OR BUST

But where was DSA — the largest socialist organization in the U.S. — during this Presidential election? While many members individually were leaders in the work to elect Biden — as an organization, we sat on the sidelines. This was the result of a “Bernie or Bust” position requiring DSA to abstain from supporting Biden pushed through by a narrow majority of delegates at DSA’s 2019 convention.

That puts DSA in the embarrassing position of now advancing a program and promoting actions for the first 100 days of the Biden administration, while as an organization it played no formal role in achieving that opportunity. Are we to understand that it would have been an equally useful result to be heading into the first 100 days of a Trump administration? Of course not! As long time trade unionists, we view this refusal to come off the sidelines as analogous to a faction within the union deciding that they don’t like the leaders of a strike or their politics. The faction doesn’t participate in picketing, or the strike kitchen, or the mass demonstrations. Then, these “do nothings” who essentially sat out the strike, come to the union hall insisting on a major role in determining the terms of the strike settlement.

A SOCIALIST’S PLACE IS IN THE STRUGGLE

DSA’s formal abstention from the Biden campaign reflects a larger ideological issue that plagues the organization: a flawed understanding of the “special role of socialists.” The constant refrain from many members is, “We are socialists and we have a special role!” Yes, socialists do have a special role to play in leading popular movements by being the most active and dedicated fighters in the struggle. That dedication and commitment — not pontificating about the problems with the “misleaders/sheepherders” or the neo-liberal from Delaware — is what opens up the opportunity to win the “uninitiated” to our socialist ideas and class analysis.

If this simple concept needs political window dressing from the socialist liturgy, here is a quote from Karl Marx from 1875 in a letter to Wilhelm Bracke: “Every step of real movement is more important than a dozen programmes.”

Bernie Sanders’s entrance onto the national election stage as a Democratic Socialist in the 2016 Democratic primaries was one of the principal causes of DSA’s rapid growth. Instead of choosing a third party route, Sanders wisely jumped into the admittedly murky swamp of Democratic Party politics. And by doing so, his socialist message and working class perspective blossomed and flourished in the mainstream in ways that were hitherto unimaginable.

Again in 2020, Sanders ran as a Democrat in a much more complicated candidate field. Bernie’s campaign forced the other candidates to contend with his programmatic initiatives addressing a rigged economy and our broken democracy. After the Democratic Party consolidated its support behind Biden and Bernie withdrew, he clearly understood what was at stake. Facing “the most dangerous president in US history,” he actively campaigned to get his base to support Biden and Harris.

DSA’s experience in the 2020 election can be a teachable moment. It’s time to acknowledge that “Bernie or Bust” was a major tactical and strategic error. Now, with critical reflection, it can lead to a more mature approach to our electoral politics. That maturation should begin with a disavowal of the position taken by many DSA chapters in local races that they can only support self-proclaimed socialist candidates. This too has again led to the isolation of socialists from the actual struggle over the needs and interests of our class. Many candidates stand with us on the issues. They stand for positions that will benefit the lot of working people and people of color. Their successful election would result in policies benefiting the lives of the working class. Again, this abstention is contradictory to the needs and interests of the people we purport to fight for. It just isolates us from the potential to make gains, win reforms and win respect for our analysis and ideas.

Let’s learn from 2020. Now it’s time to fight for two Senate seats in Georgia to create the most favorable playing field on which to challenge — and push — the neo-liberal President-elect Joe Biden.

…

Peter Olney is on the Steering Committee of DSA’s Labor Commission and a lifelong union organizer. In 2020, he volunteered with Seed the Vote (STV) to work on the Biden campaign in Maricopa County Arizona. Rand Wilson, also a lifelong union organizer, has been a member of DSA since 1986. After Sanders declared for the Democratic nomination in 2015, Wilson registered as a Democrat for the first time. He was elected a delegate to the 2016 DNC convention and was a member of the DNC Credentials Committee for the 2020 convention.

“If we forget where we’ve been we can get lost again.”

By Hardy Green

Medgar Evers’ house is a festive green—a color that an upscale clothing catalog might term “sea foam” or “island reef.” The concrete driveway has a pronounced crack right down the middle, and you can look down it and right through the carport into the back yard. The lawn is just clover and the kind of weedy, junk grass that will grow anywhere.

You might not imagine that one of the civil rights movement’s true heroes lived in this unprepossessing, one-story structure. If you drove past the house, you might not give it a second thought.

He lived here and died here. For in 1963, Evers returned to this house from a movement meeting, got out of his car, and was shot and killed. His ghost still lingers.

What is a ghost anyway? A sudden, surprising movement glimpsed out of the corner of one eye? A hair-prickling sensation that makes you flinch and say: “God, what was that?” Or a presence not seen at all?

Many of the latter sort of ghosts appear in the exhibit of Rich Frishman’s photos, “Ghosts of Segregation”, where you can take in the entire scoop of this amazing project. Frishman’s work, which has won him two Sony World Photography Awards, is also in the collections of numerous institutions including Houston’s Museum of Fine Arts and the New Orleans Museum of Art. Frishman’s other major project, “American Splendor”, can be seen here and Frishman talks about the project “Ghost of Segregation” here.

Medgar Evers died eleven years after he’d joined the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. in 1952. He spent the intervening period traveling from his home in Jackson, across the state of Mississippi, encouraging other people of color to register to vote, to integrate schools and public facilities, and to join in the resistance against racial injustice.

The other ghosts among Frishman’s images are not so well-known. There are lovely but haunted trees and river scenes; crumbling, collapsed, and totally vanished buildings; sharecropper shacks; and lonely gravestones. The people who passed this way—strung up on a Golead, Texas hanging tree, firebombed in a Opelousas, Louisiana church, dumped into the Black Bayou from a bridge in Glendora, Mississippi, or partying at a rundown Merigold, Mississippi juke joint—are long gone.

I have childhood memories of that peculiar time: The Memphis department-store water fountains tagged “whites only.” The hardscrabble, Third World shacks in Pike County Mississippi where you couldn’t imagine anyone actually living. The white-neighborhood dogs barking like fury whenever any dark-skinned person dared venture onto their turf. The red-dirt-road country stores with their Moon Pies and Nehi peach sodas. A conversation with a gangly blonde girl who couldn’t tell whether she was ashamed or proud that her uncle was an officer in the Ku Klux Klan. Dressing up in white sheets and threatening violence in the name of white supremacy? That’s just not something anyone at the country club would do. Still, it was probably the only bit of fame anyone in her family would ever have.

Frishman’s shots of little roadside restaurants are to me the most evocative of the time and place. A now apparently abandoned “Tastee Shack” must have tempted passersby with its fragrance of burgers and onions sputtering on the griddle. Frishman’s caption tells us that it was from this place in 1964 that two Mississippi teenagers were abducted, driven into a woods, tortured, and dropped alive into the Mississippi River to die.

Edd’s Drive-In in Pascagoula, Mississippi glows Hopper-like in the late-evening dark. At its front window, two African American youths consider a menu, as white and black workers bustle inside. All are likely oblivious to the side window, from which customers of color were once required to place their orders. But the drive-in’s proprietors remember the window’s original purpose, Frishman tells us. “If we forget where we’ve been,” one owner has told him, “we can get lost again.”

…

Overcoming the Urban-Rural Divide, Part 2

By Anthony Flaccavento

“Overcoming the Urban-Rural Divide, Part 1” is linked here

The four-week period since the November 3rd election has demonstrated more than Donald Trump’s complete self-absorption and utter contempt for Democracy. Far more disturbing has been the willingness of nearly half of Americans to support him and to readily accept his lies that the election ‘was stolen’. Trump voters, we now know, include white women and men; the very rich and working- and middle-class people; suburban and rural. For some of these folks, Trump’s appeal is obvious, from lower taxes on the wealthy to reduced regulations on banks and businesses to the choice of judges aligned with the values of the Christian religious right.

But what about rural people? With the exception of a relatively small number of large-scale farmers who have benefitted from Trump’s massive subsidies (instituted to compensate for their Trump-driven loss in export markets), most rural communities have seen little to no benefit these past four years. The coal industry has continued its decline, new jobs in manufacturing have largely been offset by factory closings, and long-standing problems of underfunded schools, declining infrastructure and opioid addiction have been given only fleeting attention. So why is Trump’s support so strong in the countryside?

Here’s what I think: A lot of folks love Trump because of who and what he hates. The media. Academics and experts. The ‘liberal consensus’ and the language of inclusion. The Washington establishment and its insiders. And all the snooty liberals who embrace these things. These people, these norms and institutions have, in the view of many rural people, dissed and marginalized them for decades. Seeing belief systems and ways of life ridiculed for so long, and new ideas and other people embraced by the same liberal elite, many have come to feel like strangers in their own land, as Arlie Hochschild explains in her book of the same name. This deep sense of alienation constitutes our fourth underlying cause of the urban-rural divide.

I’m not arguing here that the confederate flag is about “heritage, not hate” as some bumper stickers in my area proclaim. Nor do I contend that the neglect of rural needs and communities is somehow greater than what many historically marginalized people have faced across our history. Rather, as Ms Hochschild shows through the testimony of rural Louisianans, their own lived history is one of declining incomes and wealth, increasing health and social problems, and a steady march by the wider, dominant culture away from many of their core beliefs and values. Is their plight comparable to that of the native peoples of the Americas, or of African Americans who’ve lived through enslavement, Jim Crow, federal policies of intentional exclusion, and mass incarceration? Certainly not. Rural, mostly white people have been privileged by comparison. But the history of their own lifetimes is, mostly, quite the opposite: steadily declining fortunes, stature and privilege. Rural people have never been at the front of the line in this country, but now that they see themselves falling further back in the line (paraphrasing Ms Hochshild), they’re pissed.

The broad sense of alienation from the mainstream has been furthered by two shifts among Democrats and liberals more broadly: An embrace of wealthy elites and their priorities and culture; and the steady growth in contempt for those outside the elite liberal consensus. This dramatic shift among liberal leaders, pundits, media and organizations has fueled and justified the deep sense of alienation and the “us vs them” outrage it has spawned. This is our fifth underlying cause.

For more than a decade, Thomas Frank has been documenting this shift in the culture and priorities of Democrats. In Listen Liberal, he details the more than four-decade long march that has transformed the Democrats from the party of the working class (primarily) to the party of the professional class. In Frank’s analysis, liberals and Dems have too often minimized the collateral damage of a growth-obsessed global economy of transnational corporations, instead embracing the academic and technological superstars who have either justified or been enriched by this transition. Michael Lind goes a step further, characterizing the professional class as a “managerial overclass” of bureaucrats, academics and assorted experts whose job it is to make and enforce the rules that the rest of us must live by.

For liberals who can’t fathom why so many rural people dismiss the warnings of experts – whether about climate change or pandemics – part of the answer is that they do not trust those whom they see as spokespersons for liberal elites. And their skepticism is not always unfounded. We need look no further than the promises of Bill Clinton and his top economists that NAFTA would create a million net jobs within five years. The experts aren’t always right.