John S. Bowman 1931-2023

By Robert Gumpert

“The Forum is proud to have carried three articles by writer and editor John S. Bowman who passed away on July 28th. This is the brief tribute I wrote for his memorial on August 6 at Look Park in Northampton, Massachusetts. And here is a link to his obituary published in the Hampshire Gazette.”

Christina Perez and I will not be able to make the trip from San Francisco to the memorial in Look Park, and our son Nelson is in Tokyo, but we are there in spirit to celebrate the life of my dear uncle, John Stewart Bowman. Our love goes out to Francesca, Michela, Alex and Leo, and all of John’s friends and family.

On March 31 of this year I had the good fortune to appear on Talk the Talk, a WHMP radio show, hosted by Buz Eisenberg and Bill Newman. The topic was a new book I was part of authoring called Labor Power and Strategy. In the course of introducing the book I mentioned that the book had Northampton roots because it had been carefully edited by NoHo resident John Stewart Bowman. Bill Newman quickly exclaimed, “We know John Bowman. He has been on this show many times.” This warmed my heart because I knew Uncle John was listening from Linda Manor. And of course I knew that Uncle John probably had been on the show talking baseball, opera or the history of Northampton. He was broad reaching and ecumenical in his intellectual pursuits! And he was a no nonsense editor. He would often ask me in exasperation, “Didn’t you learn basic punctuation at Harvard?”

RIP John S. Bowman, my favorite uncle!

Peter B. Olney, son of Elinor B. Olney

A Sister’s Murder Sparks Action – Tradeswomen Respond to Workplace Violence

By Molly Martin

Carpenter apprentice Outi Hicks was working on a job in Fresno, California in 2017 when she encountered continuing harassment from another worker there. She didn’t complain and no one stood up for her. Then her harasser attacked her and beat her to death.

We don’t know whether Outi (pronounced Ootee) was murdered because she was Black, lesbian, or just female. But we do know that being all three put her at greater risk. Outi was 32 and a mother of three.

Outraged tradeswomen organized Sisters United Against Workplace Violence to provide support, education, and empowerment to women in construction.

Also, in response to Outi’s murder the Ironworkers Union (IW) launched a program called “Be That One Guy”. The program’s aim is to “turn bystanders into upstanders.” Participants learn how to defuse hostile situations and gain the confidence to be able to react when they see harassment.

“Outi Hicks’ murder hit me hard,” says Vicki O’ Leary, the international IW general organizer for safety and diversity. “Companies and unions need to change the focus of their harassment policies and need to get tougher with harassers.”

Often the victim of harassment is moved to a different crew or jobsite in an effort to defuse the situation. But such a response actually punishes the victim and not the aggressor, who remains unaffected and may continue to harass other workers. O’Leary says one of the most important parts of the program is when participants take the pledge: “I will be that one guy who tells a coworker, foreman, or general foreman to knock it off.”

“It only takes one guy to talk to the harasser or to file a complaint with the crew boss. It’s even better when the whole crew stands up together to end harassment, and we are now seeing this happen on job sites around the country,” says O’Leary. She tells of an apprentice who was being harassed by a supervisor. Seeing the harassment, everyone on the crew began to treat the supervisor the same way he was treating the apprentice. His behavior changed in a day.

Training, Risk Assessment, and Support

The IW is rolling out the program through their district councils. They want to share it with other unions and, says O’Leary, they’re hoping general contractors will jump on.

Another anti-violence program started by tradeswomen and our allies also is specifically tailored to the construction industry. ANEW, the pre-apprenticeship training program in Seattle, created its program, RISE Up, to counter the number of people, and especially women, who leave the construction trades because of a hostile work environment. ANEW director, Karen Dove, developed the program after meetings with contractors who would say “women just need tougher skin.”

The program focuses on empowering workers and employers to prevent and respond to workplace violence. It offers a range of services, including training sessions, risk assessments, and support for workers who have experienced violence.

Training sessions are designed to help workers and employers identify the warning signs of workplace violence and take proactive steps to prevent it. The training covers conflict resolution, de-escalation techniques, and the importance of creating a positive work environment.

The program is concerned with psychological well-being and is now working with a union to develop mental health services for Black workers.

RISE Up also offers risk assessments to construction companies, which help them identify areas of their workplace that may be at higher risk of violence.

Marquia Wooten, director of RISE Up, says the program is designed to change the culture of construction. Wooten worked in the trades for ten years as a laborer and an operating engineer. “When I was an apprentice they yelled and screamed at me,” she says. She notes that men suffer from harassment too. “The suicide rate of construction workers is number two after vets and first responders,” she said. “Substance abuse is high in construction.”

ANEW partners with cities, public entities, unions, schools, and employers. “They do want change in the industry,” says Wooten. Less workplace violence is good for the bottom line.

But training workers is not enough. Union staff needs training in how to respond to harassment as well. Liz Skidmore recently retired as Business Representative/Organizer at North Atlantic States Regional Council of Carpenters. They created a training to help union staff members know what to do when a member complains.

“New federal regulations require that every person on the construction job who comes into contact with apprentices go through anti-harassment and discrimination training,” says Skidmore.

“Most of corporate America requires annual training about sexual harassment, but most trainers don’t know the blue-collar world,” she says. Trainers can be classist. “To be effective, the trainer has to like these guys.”

While tradeswomen have long been virtually invisible on the front lines of the Feminist and Civil Rights Movements, we still are the ones who daily confront the most aggressive kind of sexism and racism in our traditionally male jobs. For going on five decades now we have been devising strategies to counter isolation and harassment at work and to increase the numbers of women in the union construction trades. Now we are working to educate the construction industry about how to end workplace violence. Women in construction are still isolated and often the only woman on the job. We need our brothers to act as allies.

Women who have risen into leadership positions in construction unions and apprenticeship programs have changed the culture already–in ways that make the workplace safer for both men and women.

Sometimes you just have to say something.

…

For more information about the Tradeswomen Movement see the National Taskforce on Tradeswomen’s Issues.

What Causes L.A.’s Housing Crisis?

By Dick Platkin

Three new homeless studies rebut the frequent “blame the victim” claims concocted by the urban growth machine and its supporters:

- Homelessness is caused by mental illness and drug addiction. No, most people with severe mental illness are not unhoused, and many people who are unhoused succumb to mental illness and/or drug use after they become homeless.

- Homelessness is caused by people moving from cold areas to sunny California, especially Los Angeles. No. Three-quarters of the unhoused are local.

- Homelessness is caused by people who voluntarily choose to live on the streets or in a car. No, the homeless grew up in a house or apartment, and economic conditions forced them to become unhoused. Few of them impulsively decided to live outside.

- Homelessness is a police problem. No. Homeless is not a crime, and the police can only harass the unhoused to the point they relocate elsewhere.

The best of these new studies is from the University of California’s San Francisco medical school (UCSF): Toward a New Understanding: The California Statewide Study of People Experiencing Homelessness. This study determined that the main cause of homelessness in California is financial: “Even if the cause of homelessness was multifactorial, participants believed financial support could have prevented it. Seventy percent believed that a monthly rental subsidy of $300-$500 would have prevented their homelessness for a sustained period; 82% believed receiving a one-time payment of $5,000-$10,000 would have prevented their homelessness; 90% believed that receiving a Housing Choice Voucher or similar option would have done so.”

The second study is from the Los Angeles Homeless Service Authority’s (LAHSA) 2023 Greater Los Angeles Homeless Count. The LAHSA report documents that homelessness increased 9 percent in Los Angeles County and 10 percent in the city of Los Angeles over the past year. One of the report’s findings stands out :“The City and the County are on track to create approximately 8,200 affordable homes this year, but all of the leaders acknowledge the need for more affordable housing.” This is LAHSA’s politically adroit way to acknowledge that LA’s unhoused population grew faster than local programs could house them.

The third study was in the June 19, 2023, Wall Street Journal: Homeless Numbers rise in U.S. Cities. The paper reported, “Rising housing costs and the limited supply of affordable apartments are major factors contributing to homelessness around the country . . .” What the paper identifies as national trends certainly applies to California.

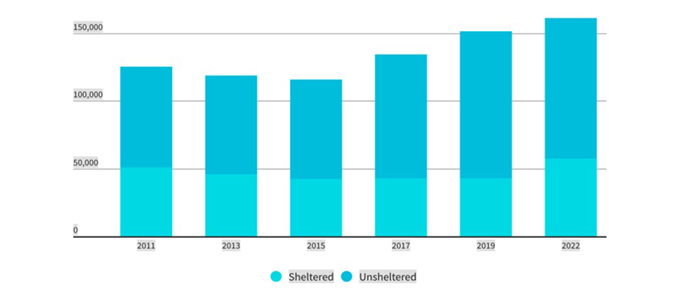

As good as these studies are in documenting the increasing numbers of unhoused people, they do not adequately examine the causes of the growth trends they describe. Like the country as a whole, in California homelessness has steadily increased since 2014, when the Great Recession finally ended.

While these developments are carefully documented in the LAHSA and Wall Street Journal studies, even rigorous studies, like the UCSF one, failed to answer the obvious questions. Why is homelessness increasing, and what can be done about it? Here are my answers:

Cause #1) Elimination of public housing: A major reason for the decline in the number of affordable housing units is the termination of the Federal government’s HUD (Department of Housing and Urban Development) public housing programs, beginning in the early 1970s. An obvious response is the restoration of the Federal government’s public housing programs. This won’t be cheap, and I could only find one detailed proposal for this, in Senator Sanders 2020 presidential campaign platform.

In California there is a second cause, the State Legislature dissolved all local redevelopment agencies in 2011. The State had required them to spend 20 percent of their budgets on public housing, and this legislative action eliminated a second source of funding. While older public housing still exists, like Ramona Gardens in Los Angeles, it was built over 50 years ago.

The national and local alternative to public housing is the crackpot theory that profit-driven private sector developers will build unprofitable low-priced housing. This approach, including local density bonuses ordinances, has failed to reduce homelessness, as documented in the three studies I linked to.

Cause #2) Rampant real estate speculation: A second financial approach is taming the “urban growth machine” through a vacancy tax and an end to the variances and zone changes that City Hall automatically grants to luxury, high-rise apartments.

Cause #3) Decline in real wages: In Los Angeles a tenant needs to earn $39/hour to rent a typical two bedroom apartment. Since the average salary in LA is $33/hour, many people fall through the cracks. Furthermore, inflation has widened this gap, pricing more people out of the private housing market. Some of them join the ranks of the unhoused.

Cause #4) False claims about zoning and a housing shortage: City Hall’s responses to the housing crisis make conditions worse, not better. A perfect example is LA’s 2021–2029 Housing Element. Its implementation through citywide upzoning increases property values and causes rents, housing prices, and homeless numbers to rise. This is why these upzoning programs need to be jettisoned.

The reason why these four causes of the housing crisis are glossed over in otherwise excellent studies is the misuse of the public sector to enrich private real estate speculation. Until this changes, the number of unhoused, overcrowded, and rent-gouged people will continue to grow.

…

This piece first appeared in City Watch LA where Dick Platkin writes on urban issues

Which Side Are You On?

By Steve Early

Bosses, Union Officials and Rank & Filers Debate Work from Home

Work from home arrangements proliferated during the pandemic and became very popular among white-collar workers. They are now the subject of a tug of war between labor and management because high profile bosses—like Mark Zuckerberg at Meta, Elon Musk at Twitter, Jamie Dimon at JP Morgan Chase, and Andy Jassy at Amazon–have decreed that it’s time to get back in the office.

Such mandates have triggered widespread resistance, even among workers without collective bargaining rights. At Amazon, for example, more than 20,000 employees signed a petition urging Jassy to reconsider his May 1 deadline for everyone showing up at least three days per week, with few exceptions. On May 31 in Seattle, more than 1,000 people walked off the job, for one hour during lunchtime, to protest this “harmful, unilateral decision.” Another 2,000 Amazon employees engaged in similar solidarity actions worldwide.

In the public sector, a work-stoppage earlier this year by 150,000 federal employees in Canada resulted in what three labor researchers call “important steps toward an ongoing work-from-home protocol.” These include “requiring that remote work requests be evaluated individually, not by group of employees, and the creation of joint employer-union committees in each department to oversee the future evolution of remote work practices.”

Another commentator hailed this Public Service Alliance of Canada (PSAC) side agreement as a big win in the “on-going power struggle to determine who has the authority to define work conditions.” According to this observer, “remote work…is a front on which organized labor should give its all to secure better arrangements for all workers.”

A CWA Campaign Issue

Within one major AFL-CIO union, there has been less unanimity that work-from-home/hybrid schedules are a good thing—and worth defending and extending.

In the Communications Workers of America (CWA), tens of thousands of members in telecom, the public sector, higher education, the media, and airlines all worked from home during the pandemic and got to like it. As a result, WFH became one important issue in a rare contested election for CWA national president.

That three-way race ended last Monday, July 10, in St. Louis, when 940 union convention delegates cast ballots on behalf of 360,000 members in the U.S. and Canada. They picked 71-year-old Claude Cummings Jr.,a CWA Vice-President and civil right leader from Texas, who is now the union’s first African-American president. Both Cummings and former NewsGuild organizer Sara Steffens–who was eliminated in the first round of voting but then backed Cummings in the second–pledged to defend WFH in new and old bargaining units.

“… service reps in Minneapolis had discovered that remote work “was safer, saved them money on commuting and childcare, gave them more time for rest and with their families and more control of their workspace.”

They argued that CWA would not be well-positioned to help more white-collar workers win bargaining rights and contract language on WFH if top union officials opposed remote work options. In contrast, the third candidate–CWA Vice-President Ed Mooney, a longtime telecom industry negotiator– was an internal critic of WFH agreements and objected to continuing one at Verizon. “Everybody liked work from home,” he acknowledged, in a May 15 candidate debate. But, according to Mooney, WFH has put “the companies in the driver’s seat because they are aware our members like it so much.”

Taking that contested position, while also being dogged by accusations of personal misconduct, proved fatal to Mooney’s candidacy. He lost to Cummings, in the run-off, by a margin of 59% to 41% among the delegates voting.

AT&T Worker Protest

Last September, it was thousands of AT&T call center workers who felt like losers when management ordered them back to work. According to Local 7250 President Kieran Knutson, his fellow customer service reps in Minneapolis had discovered that remote work “was safer, saved them money on commuting and childcare, gave them more time for rest and with their families and more control of their workspace.”

That’s why Knutson and leaders of other AT&T locals launched a grassroots campaign aimed at keeping Work from Home (WFH) as an option at AT&T, the most heavily unionized telecom company. They organized protests and press conferences which drew national drew media attention in outlets like CBS Evening News,Fortune, and The Guardian. They collected 8,000 rank-and-file signatures on a petition demanding WFH as a permanent option for customer service reps and teleconference specialists, communications techs, and workers in other eligible titles. The pro-WFH petitioners also expressed solidarity with fellow CWA members who “do want to work at a central business location and support keeping that option as well.”

In Knutson’s view, this grassroots initiative “didn’t get much support” from top CWA officials who negotiate with AT&T on agreements covering 70,000 workers around the country. Frustrated that the “union has gotten so used to a top-down model where leaders tell the members what’s important,” rather than the other way around, Knutson joined two ad hoc committees that challenged the presidential candidates on key issues, including WFH and, in Mooney’s case, his alleged non-compliance with CWA’s policy on “mutual respect”.

Union Strategy on WFH

Differences quickly emerged in their responses to questions posed during CWA’s first ever CWA presidential debate on May 15, organized by Knutson’s local and seven others (or a related candidate questionnaire that only Mooney ignored.) Cummings, a leading CWA negotiator with AT&T, reiterated his support for Local 7250’s petition last year because he “recognized early during the pandemic that our members were enjoying WFH.” Cummings also argued that more job flexibility can be achieved through periodic contract negotiations, so-called “effects bargaining,” and “a strong mobilization effort for WFH during negotiations.” The now-CWA president noted that rank-and-filers covered by WFH deals need a “strong and effective network” of “empowered job stewards.”

“Proper tools, training and education is essential to the success of this process,” Cummings said. “Zoom membership meetings and quarterly gatherings such as ‘Union Days’ that include educational programs along with outreach can help keep our members engaged and connected to their local unions.” While he served as CWA Vice-President and director of the union’s fourth largest district, Cummings own staff of organizers and reps worked from home, and he reported no membership complaints about that.

Drawing on her background as a media industry organizer and negotiator, Steffens called WFH “a major quality-of life benefit, as important as pay and job security, for our members in jobs where it’s possible.” She argued that CWA should do more to “collect and share best practices for work from home, including model contract language on critical issues like new hire data and orientations, remote surveillance, equipment reimbursement and callback protections.”

To deal with the internal and external organizing challenges created by remote work arrangements, Steffens called for better national union “systems to support hybrid and home-based workers and units, including funding home visits, organizing blitzes, electronic membership cards, virtual union boards and other strategies to ensure that our union density and activism remains strong.”

Remote Work Skeptics

… some rank-and-file radicals who belong to those locals [of techs felt] WFH “takes away our bargaining power, leaves people more atomized, and gives management too much control.”

Former Pennsylvania Bell technician Ed Mooney took the most critical view of WFH. During the pandemic, the CWA staff directed by Mooney in the mid-Atlantic states was ordered to return to union offices long before their counterparts elsewhere did so, according to the CWA staff union. On work-from-home in telecom, Mooney told debate listeners in May that “the whole world is trying to figure out is this a “flavor of the month” kind of thing for employers?’ Are they going to do it just to eliminate workers? Are they going pull them back and forth? So, when we go and bargain this stuff, we have to make sure we get protections.” He predicted much more “push and pull” over hybrid work schedules until “we get this to a spot where it’s mutually beneficial.”

Mooney defended his role in negotiations with Verizon over WFH last year. During those talks, other CWA bargaining committee members like Local 1400 President Don Trementozzi had to overcome Mooney’s initial opposition—voiced during union caucuses– to extending remote work opportunities for Verizon customer service reps.

Then and now, Mooney’s questioning of WFH resonated not only with east coast Verizon locals, dominated by technicians, but also some rank-and-file radicals who belong to those locals. Echoing Mooney’s concerns, one long-time activist and fellow Labor Notes supporter told me that WFH “takes away our bargaining power, leaves people more atomized, and gives management too much control.”

Another Verizon tech in Pennsylvania described both an upside and a downside to his experience with “home garaging” during the pandemic. Most of his co-workers really liked not having to report to a Verizon garage to pick up and return their trucks on a daily basis. With no unpaid commuting time, he found himself “actually working an 8-hour day for the first time ever.”

On the other hand, the job of CWA stewards became much harder because the “organic organizing opportunities” created by work group meetings, before and after daily shifts, no longer existed. Face-to-face contact was replaced with phone calls and much more e-mailing back and forth, in response to questions about workplace issues, management policy changes, or the status of grievances. There was, he reported, a “loss of cohesion” that might undermine “strike capacity” in the future.

Three decades ago, I was similarly ambivalent. As a national union rep between 1980 and 2007, I had much first-hand familiarity with the workplace culture of telephone company service reps and the different (and more blue-collar) world of inside and outside “plant technicians.” I also worked with cable TV and telco technicians in CWA and IBEW who had divergent views on “home garaging” many years ago. Most cable guys loved being able to take their trucks home at night and go directly to customers’ homes the next morning. Union-minded telephone techs wanted their co-workers to report to a central location every day, so they would have more regular contact with shop stewards.

After I helped a group of 1,500 customer service reps in New England get a first contract in the mid-1990s, it wasn’t long before the company now known as Verizon wanted to do a “trial” of work from home. One reason for our resistance to that proposal was the fear that collective action in newly organized call centers would be more difficult if everyone was isolated at home and not working under the same roof.

CWA’s WFH Defenders

The availability of now well-tested new tools for communication, coordination, and membership participation–that were not available back then–has convinced me that greater union flexibility on this issue is absolutely essential. One local union leader who has been most persuasive on this topic is Don Trementozzi, a former customer service rep, longtime Labor Notes supporter, and founding member of Labor for Bernie in 2015.

No stranger to union militancy, Trementozzi has been involved in two major Verizon strikes, a local work stoppage at AT&T Mobility, and the nation’s longest walkout in 2014, a successful fight by 2,000 workers against contract concessions at FairPoint Communications that lasted 131 days. Trementozzi’s fast-growing Local 1400 is based in New England and reflects the unusual occupational diversity of CWA nationally.

By the end of last year, its 2,700 members included customer service and sales reps in call centers or retail stores, media and manufacturing workers, soft-ware developers, data center staff, and local government employees. Trementozzi also helped nurture and support the Alphabet Workers Union, a self-organized group at Google, that grew to over 1,000 members while working remotely and now have their own newly-chartered Local 9009 in California, where the company is based.

According to Trementozzi, rank-and-file participation in his local actually increased during the pandemic. Because bargaining sessions, committee meetings and general membership gatherings were conducted via Zoom, they attracted people who would not have attended in person, after working all day or all week in their previous work locations. Local 1400 continued to have exceptional success recruiting new members, including those working remotely while they campaigned for union recognition.

Trementozzi believes that WFH “addresses a key quality of life issue for hundreds of thousands of workers we represent and even more we are trying to organize. In every contract survey, CWA members have told us to make this a key proposal at the bargaining table.” His experience butting heads with Mooney over the WFH extension at Verizon last year turned him into a supporter of Steffens’ candidacy, despite her non-telephone industry background.

Trementozzi ultimately became her campaign manager and, after her defeat on July 10, urged other Steffens supporters to back Cummings in the run-off, insuring the latter’s victory over Mooney. When polled before the convention, AT&T workers in Minneapolis Local 7250 overwhelmingly backed Cummings. So WFH defender Kieran Knutson and other delegates from his local voted for the eventual winner in both rounds of balloting. Both Trementozzi and Knutson hope that CWA’s unusual campaign debate over the future of work from home will contribute to more member-driven organizing and bargaining strategies in their own union and others, to the benefit of all workers.

…

(Steve Early was involved in organizing, bargaining, and strikes at AT&T and Verizon for 27 years, while serving as a Boston-based CWA International Representative. He now belongs to a NewsGuild/CWA Freelancers Unit in the Bay Area and was a supporter of Sara Steffens campaign for CWA President. A different version of this article appeared originally in In These Times.)

Gay Community and Allies Stand Up to Bullies

By Molly Martin

Dateline: Sonoma County, California: As LGBTQ people and their families in hostile states like Florida packed their bags to move to nondiscriminatory states like California, those of us who live in the Golden State braced ourselves for an onslaught of anti-queer violence during June. Yes, we worried about becoming targets of violence, but that didn’t mean that we went back into our closets. Gay Pride celebrations here in Sonoma County were more robust than ever.

On June 3, Santa Rosa hosted its biggest Sonoma County Pride march ever. This year the haters didn’t show up, but they have been targeting our libraries and drag queen (and drag king!) story hours.

Sonoma county has a large organized queer community, and our presence has had an impact on the culture here. The library is a fine example of a community institution successfully reaching out to all its patrons, including queers.

With 13 branches around our far-flung mostly rural county, the library system, in their words, “…makes an effort to be inclusive of all the different ethnic and identity groups in our communities. Programming has included drag story hours, LGBTQI teen groups and activities, Here+Queer the Sonoma County LGBTQI Archives.”

After a recent library commission meeting where vocal detractors made public comments, displayed signs, and stated that they intend to protest queer programming, the library let supporters know how we could help. They made it clear that if we wished to counter-demonstrate, we must practice nonviolence. They also suggested we could write letters to the commission. Here is what I wrote:

Dear Sonoma County Library Commission,

I’m writing to thank you for including queer books and queer programming at our Sonoma County libraries. I see books by and about LGBTQ people prominently displayed, including my own book with queer content, Wonder Woman Electric to the Rescue.

I’m a lesbian feminist who came of age in an era when books about lesbians and gays were exceedingly hard to find. Publishers and printers refused to print the books we wrote and so we started our own publishing and printing businesses. And we started our own bookstores because our libraries did not have our books.

I now use the library to check out audio books (thank you!), and so I no longer buy many books. But I had to buy Gender Queer by our own Sonoma county writer Maia Kobabe, the most banned book in the country today. I’m proud that my local library carries it.

Sincerely and Queerly,

Molly Martin

When asked how it felt to be in the midst of the national dialogue, Ray Holley, communications manager for Sonoma County Library said, “Democracy is messy and it’s complicated. And the free public library is such a good example of that. Libraries are for everyone. Not every book in the library is for every patron, but every patron is going to find a book in the library. ʺ

Queers and our allies are standing up to the bullies and book banners. A recent protest, originally organized by members of a private Facebook group called Sonoma County Parents Stand Up for Our Kids, ballooned when 130 counter protesters arrived in support of Drag Story Hour. The local newspaper reported that, “Counter protesters from Amor Para Todos, Petaluma Pride, Unitarian Universalists of Petaluma and others held signs and waved LGBTQ+ Pride flags peacefully next to five protesters from the Facebook group.” There was no threat of violence. At another protest the anti-gay contingent got aggressive, pushing one woman, calling men f****t, and screaming in people’s faces. They call drag story hours “weird, demonic and evil.”

Now we have learned that the church that organized the anti-drag protests, Victory Outreach of Santa Rosa, has been granted $400,000 under the California State Nonprofit Security Grant Program, which “helps places of worship better defend themselves against violent attacks and hate crimes.” Another local grant recipient, Calvary Chapel The Rock, is also accused of anti-LGBTQ sentiments.

Jason Newman, a Petaluma marriage and family therapist who is gay, says there is no justification for the state helping these churches, which he called hate groups. More deserving recipients of this state money might be the LGBTQ groups being attacked by these religious cults.

Feel the same? Want to let the State know? Here’s what I found online. The state office is the California Office of Emergency Services. This is the best email I found (I don’t think they want emails): Nonprofit organizations should send their Single Audits or any audited Financial Statements or Grant-Specific Audit reports electronically to Cal OES at: GMD@caloes.ca.gov

But the phone number is 916-845-8510.

…

Looking Back at the Steelworkers Fight Back Campaign – Part 3

By Garrett Brown

This is the 3rd in a three-part Stansbury Forum posting on Steelworkers Fightback (SFB), a reform movement within the United Steelworkers Union in the 1970’s. Garrett Brown documents the issues and personalities that drove that movement. The series is of great relevance today and can help inform our understanding and appreciation of the reform movements underway in many large US unions. The International Brotherhood of Teamsters (IBT) has new leadership as does the United Auto Workers (UAW). In the United Food and Commercial Workers union (UFCW), America’s largest retail union, there is an active opposition called Essential Workers for Democracy. They had a big presence at the union’s most recent convention in April and are actively pointing toward the 2028 convention. Peter Olney, co-editor of the Stansbury Forum

Part 3 – Strengths and Weaknesses of Steelworkers Fight Back

Despite SFB’s previous electoral successes in District 31, it was clear that scaling up to a national level for the 1977 international union election was a huge challenge. A challenge that was made more difficult by increasingly apparent weaknesses in the campaign strategy, a fractured national campaign office staff, and frictions between Chicago and Pittsburgh campaign offices.

The top-down centralization of the campaign meant the Chicago office made all the decisions about strategy and priorities as well as all the policy decisions, selection of campaign issues, and campaign statements for the entire country and Canada. Local knowledge and input from outside of Chicago was not well recognized or used, leaving supporters to basically “follow orders from HQ.” Internal communication with the field, which could have inspired supporters around the country with the successes and lessons learned by others, was weak, and often campaigners relied on leftwing newspapers such as The Militant of the Socialist Workers Party and The Daily World of the Communist Party for campaign news.

Strategy

“Campaign headquarters did not recruit and promote candidates for the district director elections – outside of District 31 …”

The campaign had a decidedly basic steel focus, which did not necessarily match the key concerns of non-steel and smaller locals, which made up 75% of the membership. The SFB campaign was not well versed on issues of concern in Canada – both internal to Canada and Canadian steelworkers’ relations with the USWA based in the U.S. – nor with issues affecting local unions in “open shop” states like Texas.

The SFB campaign barely touched Canada, whose 900 local unions had a “favorite son” candidate – Lynn Williams – on the McBride slate. Over the years, Canadians have played a key role in the USWA with two being elected president – Williams, after McBride died in 1983, until 1994, and later Leo Gerard from 2001 to 2019. Gerard had worked against Sadlowski in the 1977 election. So a Canadian candidate on the SFB slate might have made a difference.

The Deep South locals saw the SFB campaign mostly in the form of traveling teams of supporters from Chicago and other parts of the country. In July 1976, one of the traveling supporters – Ben Corum – was shot through the neck while handing out SFB flyers at Hughes Tool Co. in Houston. So in these areas there was basically a clear field for the international staff and local officials to push the McBride campaign.

Campaign headquarters did not recruit and promote candidates for the district director elections – outside of District 31 – which would have created mutually beneficial electoral alliances between the Chicago SFB and local district director campaign organizations. SFB eventually won the majority of 10 of the union’s 25 districts, so there might have been additional reformers elected to the union’s International Executive Board as well increased votes in the presidential election with SFB-supported District Director campaigns.

The campaign hoped to compensate for the lack of local grassroots organizations, and the refusal of the Pittsburgh union HQ to release information until late in the campaign about the location of local unions, with a high-profile media campaign. Sadlowski had received almost universal good press in the District 31 campaigns as the “bold, young maverick,” but the national media coverage was more mixed, no doubt influenced by opposition to the SFB slate from industry and union officialdom.

Finally, the successful legal strategies to harness the power of the courts and Labor Department to overturn fraudulent elections in the Mine Workers union and District 31 campaigns was not a guarantee in the USWA presidential election conducted under a different administration. It was Republican administrations (Nixon and Ford) that had ordered the election reruns in the UMW and USW-District 31 – in part because this advanced standard Republican talking points about the corruption and violence inherent in labor unions. In January 1977, however, a new Democratic Administration, elected with the strong support of the USWA and other union officials, came to power in Washington.

Internal Conflict

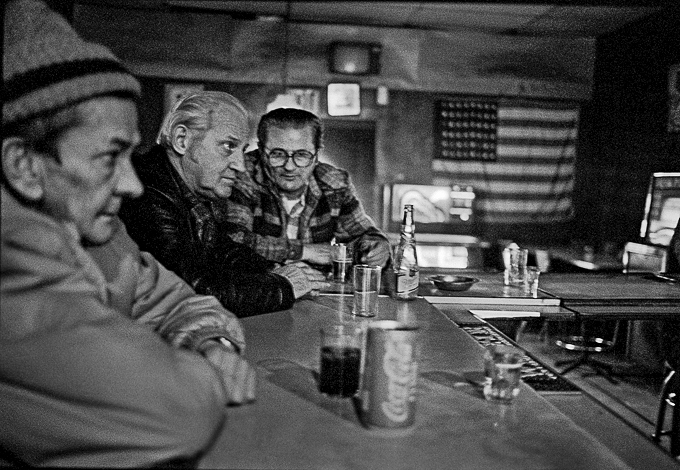

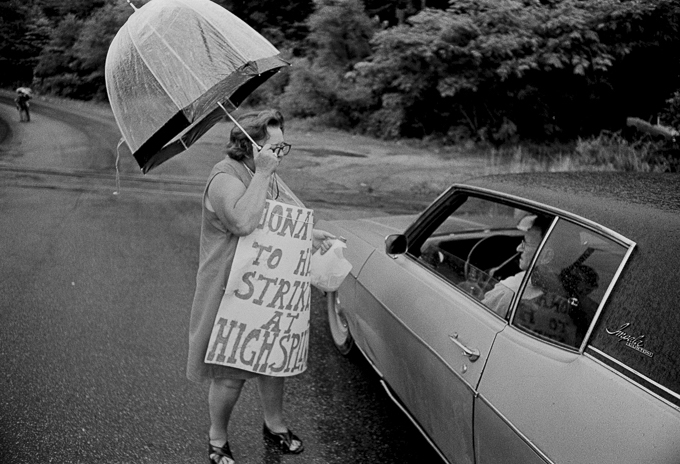

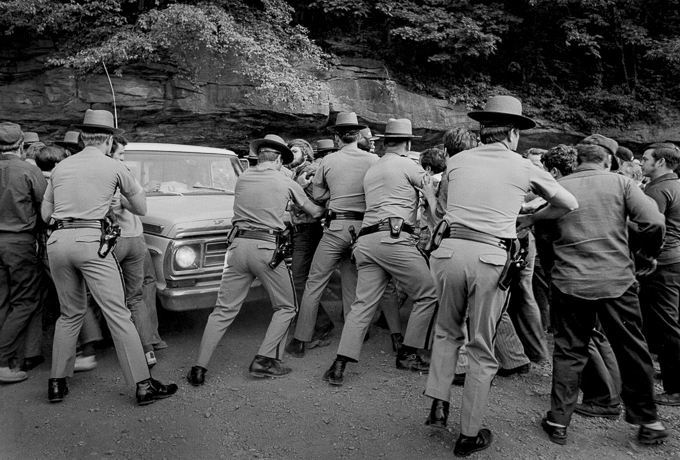

These weaknesses in strategy were compounded by a divided staff in the Chicago headquarters. The headquarters staff was basically two camps of people. The first group were locals led by Clem Balanoff – the brother of Jim Balanoff – who had been a steelworker at Youngstown Sheet and Tube in Indiana for 17 years. Clem was a longtime friend of Sadlowski who had been involved in his union election campaigns from Local 65 president through District 31 Director. The second group were “out-of-towners” who had worked together in the successful 1972 Miners For Democracy election campaign in the United Mine Workers union – including Edgar James, attorney Tom Geoghegan, financial manager Robert Hauptman. Not from the MFD, there was independent photographer Robert Gumpert and graphic artist Sandy Cate, from the West Coast.

It was not clear whether Clem Balanoff or Ed James was the actual head of the campaign – but it was clear that there was dislike and mistrust between the two groups. The locals called the MFD veterans “technocrats” who did not know the local community and personalities, and were new to the steel union. The “out-of-towners” found it increasingly intolerable that Clem and his crew were reluctant to share information and collaborate in the essential tasks of the campaign. The working styles of the two groups were completely different and a mismatch from the beginning.

Clem Balanoff got his political training as a member/supporter of the Communist Party during the Cold War and Joe McCarthy-era repression. He was secretive, trusted only a small group of people, and was personally paranoid and inclined to circulate rumors and use his friendship with Sadlowski to bolster his position in the internal debates and staff infighting. Clem had been an effective campaign manager in District 31 union elections, but he did not have the skillset needed for a national campaign where SFB had to create, inspire and lead an effective network that did not yet exist, and which could only come about with transparency, delegation of authority and initiative, flexibility, and trust and openness with others.

Fortunately, the office manager of the SFB’s headquarters was George Terrell, who not only got along with all sides, but was capable and even-tempered. There were about 20 regular paid and volunteer staff in the office every week handling work assignments like producing campaign materials, fundraising, plant-gate leafleting, union hall rallies, candidate scheduling, responding to media inquiries and to supporters calling in from around the country.

There were somewhere between 30 and 40 paid staff working at campaign offices outside Chicago, including a number of Chicagoans who were sent from HQ to organize in local areas. Part of the SFB response was to organize traveling teams of steelworkers from Chicago to go to local areas, leaflet the plant gates, and coordinate with local individual supporters. It was remarkable to see rank and file steelworkers gave up their vacation days to join these traveling teams, and use sick days and free time for local campaign activities.

At the same time, there were tensions between the campaign headquarters in Chicago and the Pittsburgh SFB office, the two most important campaign offices. Pittsburgh was where two of the SFB slate members worked at USWA headquarters – Andy Kmec and Oliver Montgomery – and where another union staff member Pat Coyne was the key coordinator of the SFB campaign. Kmec was protected against Official Family retaliation by the independent field staff union, while Montgomery and Coyne had protection from a USWA local representing headquarters professional staff. The campaign offices in Chicago and Pittsburgh were operating in a different set of circumstances, which the Pittsburgh group felt that the Chicago headquarters did not understand and did not accommodate local initiative. Clem Balanoff’s son – Clem Jr. – was eventually dispatched to work in the Pittsburgh office, but Pittsburghers, seeing him as young and inexperienced, were not sure if this was additional support or espionage from Chicago.

Moreover, Coyne took a page from Clem Balanoff’s book and tightly controlled the Pittsburgh office, although leeway was given to some radical SFB supporters, if trusted by Coyne. In both cases, the offices were trying to prevent the campaign from being defined as “radical” or “communist” due to the high-profile participation of steelworkers in leftwing groups. At the same time the campaign wanted, needed, to tap into these groups’ networks and activism. In some locales and locals, radical steelworkers of various organizations were the best organized and most committed campaigners, and this was a resource that could not be ignored. No one on the SFB side was satisfied with this schizophrenic approach, and the McBride campaign continued to red-bait the campaign in any case.

Around Thanksgiving 1976, several months into the campaign, the “out-of-towners” had reached a breaking point, openly talking of resigning en masse. According to Bob Gumpert, the group decided not to resign after Tom Geohegan made an impassioned plea at the gathering of the “out-of-towners” that the SFB campaign – win or lose – was too important for building the momentum of union reform movement within the USWA, and other unions, for the group to walk away at this critical juncture.

Sadlowski needed both groups at headquarters – the locals and the technocrats – as well as good relations with Pittsburgh, so a plan was made to bring in Ernie Mazey for the last nine weeks of the campaign as the official head of the campaign to mediate and direct the HQ groups and relations with Pittsburgh. Mazey was a longtime leader and reformer in the United Auto Workers union, and, ironically, the brother of Emil Mazey, the UAW’s Secretary-Treasurer who was a leader of the UAW’s “Administration Caucus” – the equivalent of the USWA’s Official Family. Nonetheless, tensions continued at the Chicago campaign headquarters, and led to the departure of Ed James a month before the February 1977 election.

Important Aspects of the Vote

Only 40% of the USWA membership actually voted, despite the high profile nature of the presidential contest. This was testimony, I think, to the legacy of decades worth of hand-picked, Official Family candidates running in one-person races where the union’s ranks had nothing to say about the candidates or the results. Sadlowski was popular among young, Black and Latino union members, but it is not clear how many of them voted. One-third of USWA members were under 30 in 1977, and about 25% of USWA members were Black.

SFB strategy was the slate would roll up a huge margin in basic steel to overcome weaknesses in the smaller locals, Canada, and the Deep South. But Sadlowski received 5,500 fewer votes in the 1977 presidential election in District 31 than he did in the 1974 District Director race. The SFB margin of victory in District 31 was 61% to 39% — less than expected – and the margins in other basic steel centers were less than that in District 31. In District 31, I think, McBride’s media themes had an impact over time on individual steelworkers, as did the staff electioneering in local unions, support for McBride from four of the five District 31 Director candidates. Fewer resources for local campaigning with the recruitment and support needed for traveling national teams sent out from Chicago played as role as well.

But for me, the fact that the SFB campaign won at least 250,00 votes, or 43% of the vote, on a program of union democracy, union militancy, and social unionism – the most radical union program since the 1930s – was quite an achievement, especially given all the obstacles, including some created by the SFB campaign itself.

Lessons

There are aspects of the SFB campaign that were clear at the time that radicals seeking more democratic and militant unions today might learn from:

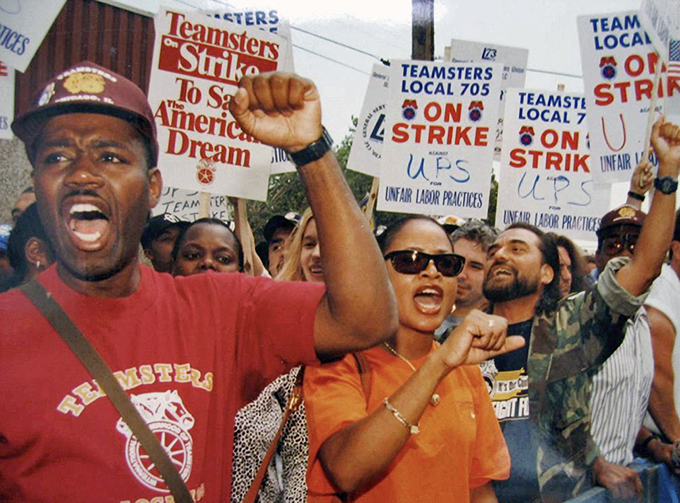

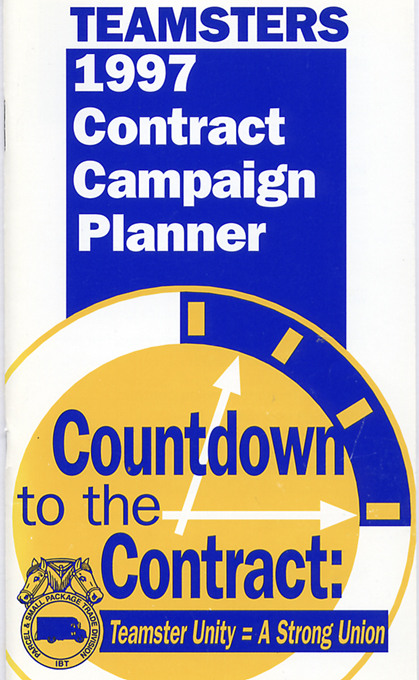

First: Campaign election organizations cannot substitute for patient, long term grassroots organizing of workers and union members, which other reform movements like Teamsters for a Democratic Union (TDU) have demonstrated in the years since the SFB campaign.

Second: Highly centralized organizations, which allow for little local initiative and participant buy-in, are not effective in organizing worker members or in winning union elections.

Third: Radicals in the union, and as non-union supporters, can play a critical role in union reform and revitalization campaigns, if they prioritize a broad, united effort to reach out to, and mobilize the membership, rather than just promoting their own organizations and perspectives.

Fourth: Ensuring that the message of the campaign gets out on its own terms is crucial, since where steelworkers heard from the SFB directly, there was a positive response. Developing a “war room” capability to effectively rebut charges like the “outsiders will control the union” theme is essential.

Fifth: Getting out the vote is critical, especially in unions like the USWA which had no tradition or practice of internal democracy, especially with key sectors like young workers, workers of color, and women.

Sixth and lastly: Incumbent officials will always cheat if allowed to do so, so preparing in advance a strong poll-watching, legal, and publicity strategy to respond to the inevitable fraud is key.

And Now

Almost 50 years later, what was the impact and legacy of the Steelworkers Fight Back campaign?

On the negative side, the promise of an ongoing, national SFB based on the campaign never materialized. This was due to two factors, in my view.

One was the physical and emotional exhaustion of the leadership of SFB in District 31 (Sadlowski in particular) and the need of District 31 Director Jim Balanoff, and SFB-affiliated local union officials, to fend off attacks from Pittsburgh while effectively administer their offices.

McBride rejected some of Balanoff’s appointments to international staff (as Abel had rejected several of Sadlowski’s proposed staff, including Ola Kennedy, who would have been the first black woman staff member in the district). To limit his influence within District 31 and nationally, Balanoff was stripped of some internal union positions. Balanoff’s strategy, in response, was to “turn down the temperature” in relations with Pittsburgh, and focus on effective management of the district. This approach ultimately failed as the McBride administration was determined to root out all officials that SFB supported.

The second factor was the swift onset of the crisis and collapse of the U.S. steel industry. In the second half of 1977 layoffs began at US Steel South Works and other mills around the country. These accelerated in 1978 and into 1979, when US Steel permanently closed 12 major facilities around the country. In 1979 alone, 57,000 steelworkers lost their jobs in plant closures, and by May 1980 the number of hourly steelworkers in the U.S. was below the previous low recorded in June 1933 at the height of the Great Depression. By 1980, the membership of the USWA had been cut in half – with basic steel taking the brunt of the cuts. These laid-off steelworkers, many of them SFB supporters, were soon to be ex-USWA members and outside the union altogether.

The argument can be made that a “fighting program” led by a national SFB to save jobs – such as demanding a massive government-funded public works program to increase the demand for steel, or cutting the work week with no reduction in pay to spread the work – might have galvanized the ranks and mitigated the crisis. But I think insurgent rank-and-file campaigns like SFB were too new to the USWA, the members too desperate for immediate solutions to their families’ intensifying economic problems, and there simply was not enough time before the industry’s collapse crashed down on the union and its members. There certainly was no support among Democrats or Republicans – either in Congress or from Presidents Carter and Reagan – for such a program.

On the positive side, the SFB campaigns from 1973 through 1977 inspired and mobilized a large swath of USWA members. Hundreds of steelworkers became involved in “taking back their union” through the SFB campaign. The 1977 presidential election with 580,000 members voting was the largest direct election ever held in the USWA and a tangible demonstration of union democracy.

Despite the national loss, supporters of the SFB message registered victories on a District and local level. In District 31, Sadlowski was elected Director in 1974 and Jim Balanoff in 1977. In in the north central states” District 33, SFB supporter Linus Wampler was elected Director in 1977. In Districts 9 (Bethlehem), 20 (Pennsylvania) and 38 (western states), reformers ran strong campaigns in 1977 against Official Family candidates. In 1981, Local 6500 President Dave Patterson, who organized the SFB campaign rally in Sudbury, was elected Director of District 6 in Ontario, Canada.

In the 1979 local union elections, SFB supporter and women’s rights defender Alice Peurala became the first and only women to became president of a basic steel union at US Steel South Works. In Local 1010, Inland Steel in Indiana, the “Rank and File Caucus” candidate, African-American Bill Andrews, became a four-term president on a platform of democratic and militant unionism. In Local 1397, US Steel Homestead Works, another “Rank and File Caucus” swept the officer positions and implemented new systems of contract bargaining and grievance handling based on substantial member participation.

Union activists in the SFB campaign went on to lead the fight against plant closures and the related community impacts in Illinois, Indiana, Ohio and Pennsylvania. In particular, Local 1397 in Homestead played a critical role regionally throughout western Pennsylvania. Even after the steel mills were bulldozed into rubble, individual SFB supporters inspired by the campaign continued the work of promoting the ideas of democratic, militant unionism, supporting union reform efforts and election campaigns in other unions, organized alternative labor education centers, and supported community-labor coalitions on a variety of issues.

The SFB campaign was a building block of a historic process in the American labor movement that started in the United Mine Workers and the Miners for Democracy in 1969, through the 1970s USWA campaigns, to the Teamsters for a Democratic Union and the election of Ron Carey as the Teamsters union president in 1991, and then Sean O’Brien in 2021; and continues with the reform movement in the United Auto Workers union, which elected Shawn Fain as president in 2023.

The themes of all these successful efforts have been the same: membership participation and mobilization; defense and support of those discriminated against and harassed; coalition building within the union; strengthening links between labor and other social movements; and strong action, including strikes, to protect members on the job.

Perhaps the most important legacy of the Steelworkers Fight Back campaign of 1976-77 is that today’s “failure” can make an essential contribution to “success” later on.

…

Note:

Among the labor history books that provide important background on the Steelworkers Fight Back campaign and its legacy are:

· “Rebel Rank and File: Labor militancy and revolt from below during the long 1970s,” editors Aaron Brenner, Robert Brenner and Cal Winslow

· “Black Freedom Fighters in Steel,” by Ruth Needleman

· “Homestead Steel Mill; The final ten years,” by Mike Stout

…

Notes from the Sadlowski Campaign for USWA President in 1976-77Part 2 – David v. Goliath in the USWA

By Garrett Brown

This is the 2nd in a three-part Stansbury Forum posting on Steelworkers Fightback (SFB), a reform movement within the United Steelworkers Union in the 1970’s. Garrett Brown documents the issues and personalities that drove that movement. The series is of great relevance today and can help inform our understanding and appreciation of the reform movements underway in many large US unions. The International Brotherhood of Teamsters (IBT) has new leadership as does the United Auto Workers (UAW). In the United Food and Commercial Workers union (UFCW), America’s largest retail union, there is an active opposition called Essential Workers for Democracy. They had a big presence at the union’s most recent convention in April and are actively pointing toward the 2028 convention.

Peter Olney, co-editor of the Stansbury Forum

Part 2 – David v. Goliath in the USWA

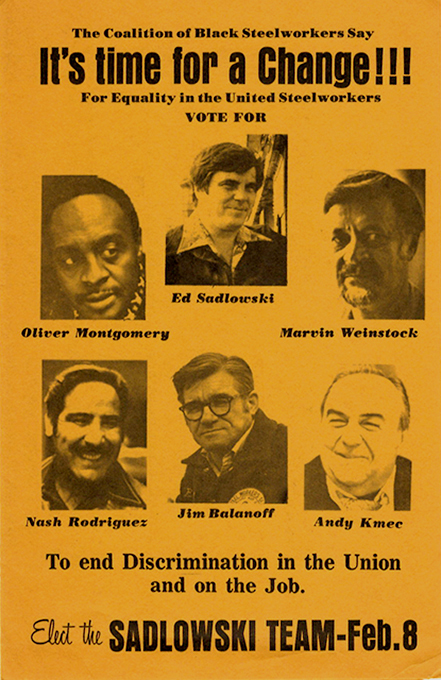

Since the Steelworkers union’s founding in 1942, there had been three top officers – President, Vice-President and Secretary-Treasurer – as well as a National Director for Canada and 24 District Directors, who together made up the union’s policy-setting International Executive Board (IEB). Despite a Black membership of about 25%, there had never been an African-American international officer and there were only a handful of Black international staff representatives or employees at the union’s Pittsburgh headquarters.

At the 1970 USWA convention, delegates rejected a proposal from the union’s internal civil rights “National Ad Hoc Committee” to increase the number of vice-presidents by two, or add three more national directors, as a means of adding Black and Latino representation to the IEB. As the SFB campaign began to take shape, with significant support from Black and Latino steelworkers, the Official Family reshuffled the international officers to create a group of five – President, Secretary, Treasurer, Vice President for Administration, and Vice President for Human Affairs. The VP for Human Affairs was tacitly designated for an African-American officer.

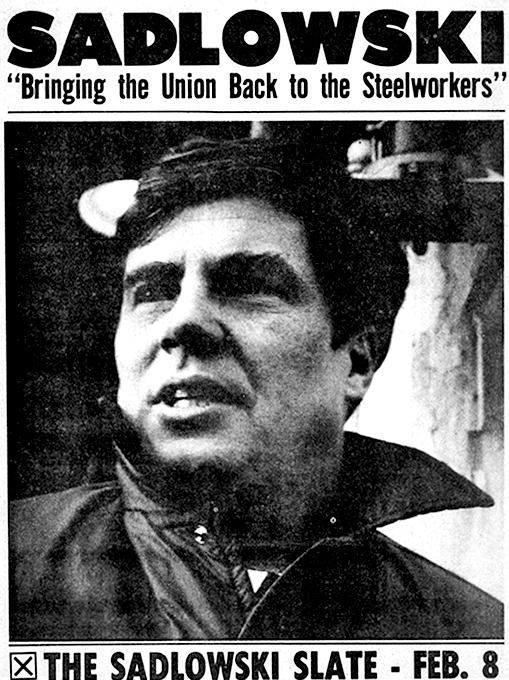

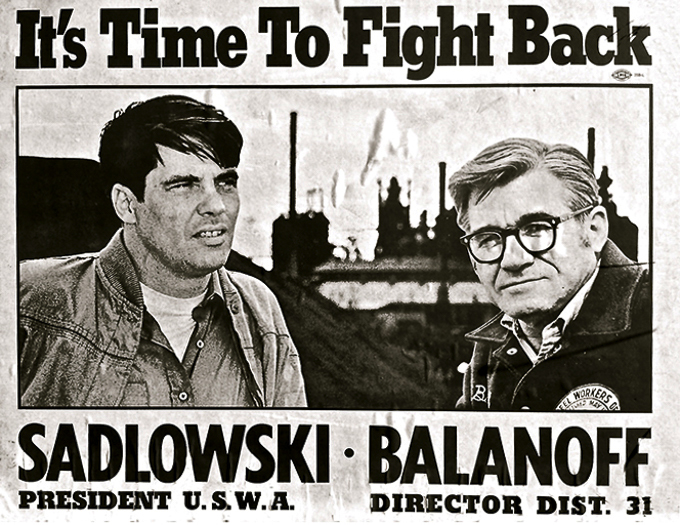

Based on the success of Sadlowski and others in District 31, the effort for a new kind of unionism in steel went national in the February 1977 election. The SFB slate for international union officers were candidates who had spent years working on the factory floor before becoming local union officers and then international staff, and who had distinguished themselves from other union officials by their support of democratic and militant unionism.

The slate was headed by Sadlowski as the presidential candidate. The Treasurer candidate was Andrew Kmec, an oil worker and steelworker at US Steel before joining the USWA staff where he organized the independent union for the 600 international staff representatives. The Secretary candidate was Ignacio “Nash” Rodriguez, with 27 years experience as a copper miner in Arizona and later worker at American Can in Los Angeles. The Vice President for Administration candidate was Marvin Weinstock of Youngstown, OH, who worked 28 years in steel mills before becoming an international staffer, and who was a member/supporter of the Socialist Workers Party in his younger days. The Vice President for Human Affairs was Oliver Montgomery, who worked in steel for 20 years before joining the union contract research department. Montgomery, an African America, was a leader of the National Ad Hoc Civil Rights organization within the USWA, as well as a leader in the national Coalition of Black Trade Unionists.

Lloyd McBride, District 34 Director in St. Louis, was the Official Family’s candidate, with the blessing of outgoing president I.W. Abel. The McBride slate included three other District Directors – Frank McGee, Joseph Odorcich, and Lynn Williams of Canada, as well as an African American, Leon Lynch (to match Oliver Montgomery on the SFB slate).

At the end of August 1976, the USWA held its convention of 4,000 delegates in Las Vegas. The convention delegates were overwhelmingly members and supporters of the Official Family, so it was no surprise that the motions from District 31 delegates to end the ENA, to establish membership ratification for basic steel contracts, and to roll back individual member dues and the high salaries of district and national union officers all failed. The convention highlighted the main themes of the SFB campaign and showed that the SFB candidates were not intimidated or afraid of the Official Family. Ten days after the convention, Sadlowski officially announced his slate’s campaign for international officers.

The SFB program was defined not so much by written materials – although those were generated and distributed as widely as there were volunteers to hand them out – but even more by the speeches and interviews of Sadlowski and slate members on a very wide range of issues, not just the standard “bread and butter” contract items like wages, pensions, speed-ups, layoffs, and grievance procedures. SFB events around the country were characterized by short initial presentations and then lengthy – often 1 to 2 hours – question and answer segments where hundreds of steelworkers got their say and got to hear what the SFB stood for.

The overall themes of union democracy and militant defense of the union membership were fleshed out in discussions of the right to strike, the right to ratify contracts, racism in the mills and in the union, women workers’ rights on the job and in the union hall, safety and health, pollution control, the salaries and perks of the union bureaucracy, the needs of small plants and their union locals, and national politics like an independent labor party and opposition to wars like the Vietnam war, which had just ended.

Sadlowski and his running mates framed their remarks as part of American working class history and the decades of efforts by native and foreign-born workers to defend their rights and improve their lives through member-controlled unions. The SFB program was one of the social movement unionism of the 1930s rather than the employer-centered business unionism of the Official Family.

Abel and the Official Family took particular offense to Sadlowsi’s mocking of them as “tuxedo unionists,” based on their high salaries. As USWA president, Abel received $75,000 annually, and District Director pay was raised from $25,000 to $35,000 at the August 1976 union convention, while the average steelworker was earning $17,000 a year.

Sadlowski was the real deal in terms of working class leaders. He was a third generation steelworker from an working class neighborhood in an industrial city. He studied labor history on his own, and was conversant in the trials and tribulations of the previous century’s worth of efforts by workers to establish unions and improve their communities. He also reveled in working class culture, such as the songs of the Industrial Workers of the World (Wobblies). Despite growing up in an insular community, and without using explicitly Marxist language, Sadlowski explained the world in class terms, from the point of view of the working class and its role in society.

This was one of the reasons that he was a very effective speaker in front of steelworkers and other workers. At the SFB campaign rallies, Sadlowski was in his element and relished the opportunity to spend literally hours answering questions and connecting his proposals to those of previous generations of unionists. At campaign events, Sadlowski was able to make a genuine connection with not only “white, male ethnic” steelworkers, but also Black and Latino workers as well.

Other members of the SFB slate were also excellent speakers and perhaps more disciplined – particularly Oliver Montgomery. Steve Early, a SFB volunteer in the Pittsburgh area, remembers Montgomery as “by far, the most fiery, articulate, and focused speaker on the SFB slate, almost Malcolm X like on the stump, due to his mix of personal cool, furious disdain, and scathing mockery of the ‘Official Family’ and its steel industry friends.”

In South Chicago, the SFB campaign was an endless whirlwind of events. These included regular leafleting, often pre-dawn, at the gates of the numerous steel mills, fabrication shops, can factories, and other USWA-represented workplaces. Rallies were held at USWA local union halls, including at US Steel South Works, Republic Steel, and Inland Steel. When the other members of the SFB slate came through town, I would usually sit down with them for interviews that would make their way into The Daily Calumet. There were grassroots fundraising events like the weekly mostaccioli pasta dinners on the East Side, numerous sales of raffle tickets for prizes, or the weekly bingo games sponsored the USWA local at Danley Machine on Chicago’s West Side. In December 1976, Sadlowski held a three-day holiday party at his home to allow for the greatest number of steelworkers to come by.

On a national level, similar activities were happening in the steel centers around the country: Pittsburgh, Youngstown, Bethlehem, Cleveland, Detroit, Baltimore, Philadelphia, Houston, St. Louis, Milwaukee, Bridgeport, CT, and Pueblo, CO. In Canada, a major rally was held with the SFB slate at USWA Local 6500 representing 15,000 nickel miners at Inco in Sudbury, Ontario. Rallies with one or more of the candidates frequently drew large audiences, often preceded by plant-gate leafleting, and generated an enthusiastic response. In areas where the SFB had few contacts, particularly in the South and Southwest, campaign headquarters in Chicago formed traveling teams of steelworkers and volunteers who used their vacation time to leaflet plant gates and make house calls with potential supporters.

On a local level, SFB committees generally consisted of individual steelworkers inspired by the campaign, and members of various leftwing organizations. SFB supporters included members of the Communist Party, Socialist Workers Party, International Socialists, and Revolutionary Communist Party, among others. Several organizations, including the Spartacist League and October League, opposed the SFB campaign as nothing more than an internal faction fight between union bureaucrats.

Radicals of the various tendencies played an important role as committed activists for the SFB campaign at plant gates, house meetings, fundraising, rallies, and outreach. Depending on the organization and individual members, radicals were effective campaigners to the degree that they prioritized broadening support for the SFB campaign message of union democracy and militancy, rather than promotion of their own organization.

Meanwhile, the McBride campaign, the Official Family, and USWA HQ were pulling out all the stops to prevent a SFB victory.

The 600 international staff representatives – only a handful endorsed Sadlowski – were coerced into making financial contributions to the McBride campaign to stay in the good graces of their supervisors. The staff spread throughout the US and Canada used their critical role at the local union level – handling grievances and contract negotiations, especially in small shops and locals – to pressure local union officers and members to support McBride. The staff conducted open electioneering for the Official Family slate at local union meetings and other gatherings.

The McBride campaign enjoyed full use of the union’s resources, including union facilities and staff time by the union’s lawyers and public relations personnel. The national union magazine, Steel Labor, campaigned so openly for McBride that late in the campaign a judge approved a settlement in a SFB lawsuit which required the magazine editors to provide SFB with the intended copy before it was published so that the SFB could object and propose alternatives to the text.

One huge advantage for McBride was that the union illegally denied SFB a complete membership roll, their contact information, and the location and officers of the union’s 5,400 local unions until late in the campaign period. This was only partially overcome when the SFB lawsuit settlement required one pre-election mailing to the entire USWA membership with SFB literature.

At the same time outside union officials – like the AFL-CIO’s George Meany and Lane Kirkland, among others – contributed resources and endorsements to McBride while denouncing Sadlowski and his slate.

The steel industry also got involved in the campaign, putting its thumb on the scale for McBride. J. Bruce Johnson from US Steel, and the lead industry negotiator in contract talks, gave interviews indicating overturning the ENA no-strike agreement (which Sadlowski opposed) would lead to “chaos” in the industry. At a local level, supervisors harassed SFB supporters on the shop floor in an attempt to intimidate steelworkers, and at US Steel Gary Works steelworkers leafleting the plant gate for Sadlowski were arrested by police called by the company (no charges were ultimately filed).

Using the media resources of the union, the McBride campaign were able to generate ongoing stories in its favor from the country’s labor beat reporters (anxious to maintain their sources at the USWA), from newspaper editorial writers, and from conservative columnists like nationally-syndicated “Evans and Novak.” One exception to the rule was a column written in January 1977 by famed “labor priest” Msgr. Charles Owen Rice in the Pittsburgh Catholic, which supported Sadlowski and noted “workers like him and so do those who are not workers – students, writers, reformed, and idealists of all sorts. The man inspires loyalty as well as affection and thus represents a formidable threat to the old guard.”

The McBride campaign pounded away in the media with their key talking points about the SFB campaign: that it was a “threat to the union and members’ livelihoods;” that the slate was inexperienced and incompetent; that a SFB presidency would bring the “chaos and collapse” the Miners for Democracy leaders supposedly brought to the UMWA; and that the SFB campaign was controlled by “outsiders“ (wealthy liberals, communists, and employers).

Some of this media campaign and adverse coverage had an impact on Sadowski’s image and raised questions for some steelworkers. For example, Penthouse magazine published a long interview with Sadlowski where he noted that some mill jobs (like those working on coke ovens) were too poisonous and dangerous to be safely done by anyone, and he waxed poetic about how he would rather see steelworkers be doctors than industrial workers. The McBride campaign spun the interview as an indication that Sadlowski wanted to eliminate steel jobs, and that he was belittling steelworkers and their contribution to American society.

In the final weeks of the campaign, it was the “outsiders” charge that got the most media attention. The SFB pushed back, pointing out all of the outside support that the McBride campaign had received directly and indirectly from non-USWA union officials, media, and steel industry, as well as the coerced donations and misuse of resources internally. But on January 9, 1977, SFB felt compelled to release information on its fundraising, which provided grist for yet another round of stories in the media.

The SFB records indicated that of the $150,000 raised ($795,000 in 2023 dollars), 80% of it came from steelworkers ($120,000) with $26,000 coming from non-USWA donors. None of these were employer donations, but rather $100 to $500 contributions from a spectrum of wealthy liberals, Democratic politicians, academics, labor attorneys, and cultural figures like author Studs Terkel ($800 donation). The largest contributor was Frank Fried at $4,000 ($21,200 in 2023 dollars).

Fried, was a successful music impresario who ran the tours of well-known folk and rock music bands from the 1960s onwards. Fried, who had been a member/supporter of the Socialist Workers Party in the 1940s and 1950s, never lost his pro-worker and pro-union beliefs and was proud to share his “ill-gotten gains” from the music world to support efforts for a democratic and militant union. Fried was the kind of guy who had been “around the block once or twice” and played a key role in the non-USWA fundraising activities designed to counterbalance the McBride’s dunning of the USWA staff and financial support from officials from other unions.

The Election

“No one will ever know for certain whether the election was stolen from Sadlowski, but there is enough evidence to raise serious questions.”

Given the unequal resources available to the opposing campaigns, the official results were not a surprise. In April 1977, the USWA International Tellers reported that McBride received 328,861 votes (57%) to Sadlowski’s 249,281 votes (43%), with McBride having an 80,000 vote margin. Sadlowski won a majority of the members in basic steel locals, a majority in two of the three Pittsburgh-area districts, a majority in locals with more than 1,000 members, and a majority in 10 of the union’s 25 Districts.

But there were enough reports of fraud that Sadlowski filed a series of appeals and lawsuits that went on for almost a year following the February 8, 1977 election. On February 18th, Sadlowski filed an internal challenge within the 10-day limit set by the union (before all reports had been received from the field) for both pre-election misuse of union resources and election day fraud. The union’s International Executive Board rejected the challenge in May 1977. Sadlowski then filed a complaint with the U.S. Labor Department on June 17, 1977. After four extensions to receive a report from the Canadian Labor Department’s investigator (who was a contract lawyer working for the USWA in Canada), the Labor Department rejected Sadlowski’s challenge in November 1977. Sadowski’s attorney Joseph Rauh then filed a suit in U.S. District Court in Washington, DC, to overturn the election and order a new one, but the suit failed.

No one will ever know for certain whether the election was stolen from Sadlowski, but there is enough evidence to raise serious questions. The Labor Department investigation discounted thousands of McBride’s votes, and the Canadian results were suspicious, not to mention all the pre-election misuse of union resources, refusal to provide membership rolls and local union locations, and extensive outside support to McBride.

Sadlowski had majority support in the basic steel locals, but these represented only 25% of the USWA membership. Sadlowski won the majority of locals with more than a 1,000 members, but there were only 192 locals of that size in the union’s 5,400 local unions. Seventy-five percent of locals had less than 250 members, which were dependent on the international staff for their basic functioning, and SFB won the majority in only 38% of these locals. Overall, SFB had poll watchers in only about 800 of the union’s 5,400 locals.

Joseph Rauh, Sadlowski’s veteran labor lawyer in Washington, pointed out that Labor Secretaries in Democratic Party administrations have almost invariably favored the officialdom of America’s labor unions, the incumbent decision-makers who decide where future campaign contributions and logistical support will go. Hence a favorable decision for Sadlowski in the election challenge was always a long shot, although that was a key part of the SFB strategy, and especially with the limited investigation conducted by the Labor Department. In the 1974 re-run of the District 31 race, the Labor Department had 200 election observers in the Chicago-Gary, Indiana district alone, but in February 1977, the Labor Department dispatched only two observers per district, for a total of less than 50 for the entire United States

Fraud

Nonetheless, the November 1977 Labor Department findings discounted more than 17,000 votes that had been credited to McBride. This represented almost 25% of McBride’s 80,000 vote margin, and was 40% of McBride’s margin in the United States. The report also confirmed instances of fraud that Sadlowski had documented in the February 1977 internal challenge and later complaints to the Labor Department and federal courts. This evidence included prohibited electioneering by staff and local union officials; locals that held no election but reported landslide results for McBride; lack of secret ballots in some locals; and vote totals which showed more McBride votes than there were members in the local. In Districts 36 and 37 in the Deep South, there were 150 local unions which reported zero votes for Sadlowski, not even one by accident.

The Labor Department refused to order a new election because the 17,000 discounted votes did not exceed 80,000 – McBride’s overall margin in the US and Canada – and the Labor Department also declined to conduct any additional investigation of the voting.

Canada, of course, is not subject to U.S. labor law, and was home to 163,000 USWA members in 900 local unions. During the campaign, former USWA president David McDonald (president from 1952 to 1965) told the news media: “Sadlowski will have to win the U.S. by a large margin because they will steal it from him up in Canada. I know, I stole four elections up there myself.”

The Canadian Labor Department responded to Sadlowski’s challenge to the election results there by contracting a local lawyer to investigate who was regularly employed by the USWA in local union grievance hearings, and whose future business dependent on the incumbent administration. McBride’s victory margin in Canada was almost 40,000 votes – half of his entire election margin in both countries. The Canadian investigator reported no irregularities that would require a new election, despite instances like District 5 in Quebec where there were 70 local unions without a single vote for Sadlowski. In District 5, McBride’s district-wide margin was 22,000 votes (24,655 votes to SFB’s 2,769), and Sadlowski officially received only 10.1% of the vote in the district while he registered 31% and 37% of the vote in the two other Canadian districts.

So it is possible that Sadlowski – if he had been able to obtain a second, supervised election as occurred with his 1973-74 elections for District 31 Director – could have won the USWA presidency.

Next: Part 3 – Strengths and Weakness of Steelworkers Fight Back

…

Learning and Building on the past: Notes from the Sadlowski Campaign for USWA President in 1976-77

By Garrett Brown

This is the first in a three-part Stansbury Forum posting on Steelworkers Fightback (SFB), a reform movement within the United Steelworkers Union in the 1970’s. Garrett Brown documents the issues and personalities that drove that movement. The series is of great relevance today and can help inform our understanding and appreciation of the reform movements underway in many large US unions. The International Brotherhood of Teamsters (IBT) has new leadership as does the United Auto Workers (UAW). In the United Food and Commercial Workers union (UFCW), America’s largest retail union, there is an active opposition called Essential Workers for Democracy. They had a big presence at the union’s most recent convention in April and are actively pointing toward the 2028 convention.

Peter Olney, co-editor of the Stansbury Forum

.

Introduction

In 1976, I was a member of the Socialist Workers Party wroting articles for the party’s weekly newspaper, The Militant, under the pen name of “Michael Gillespie.”. I was also the labor reporter for The Daily Calumet newspaper in southeast Chicago, in the heart of the Chicago-Gary steelmaking industry where almost 130,000 steelworkers formed a key part of the national economy and were the largest district of the United Steel Workers of America (USWA) union. I covered the numerous local unions of the USWA, which then had 1.4 million members in the Chicago-Gary region. The biggest story during my days at the newspaper was the election campaign of Ed Sadlowski and the Steelworker Fight Back (SFB) slate for international officers of the USWA leading up to the February 1977 election.

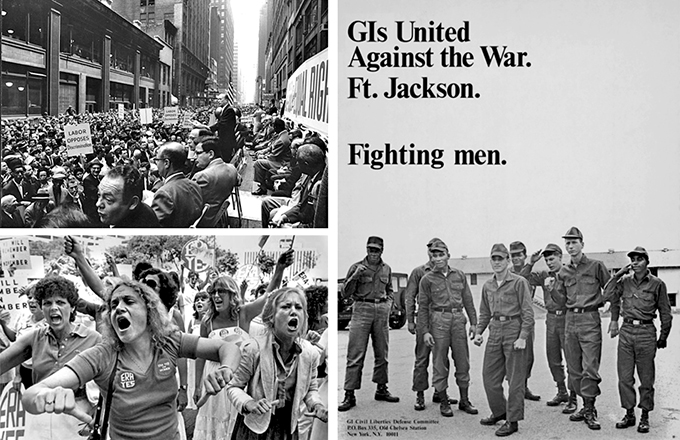

The significance of the Steelworkers Fight Back campaign was that it was part of a wave of efforts by rank-and-file union members to fight for union democracy, and to remake their unions into more militant defenders of the rights and needs of their members, including not only economic issues but also addressing historic discrimination against Black, Latino, and women steelworkers. This effort continues today – almost 50 years later – as a new generation of working class leaders seek to organize new unions in their workplaces and to reshape their existing unions as democratic and militant organizations that can defend them on the job.

Part 1 – The right moment and the right campaign

Upper Left: Charles Zimmerman speaks at a civil rights rally in the New York Garment District on 38th Street near 7th Avenue in New York City. Signs include “Labor Opposes Discrimination” May 17, 1960 Creative Commons/Kheel Center | Lower Left: Women demonstrate in favor of ERA. Tallahassee, Florida around 1979. State Library and Archives of Florida. | Right: Poster: GIs united against the war, Ft. Jackson. 1069. Library of Congress