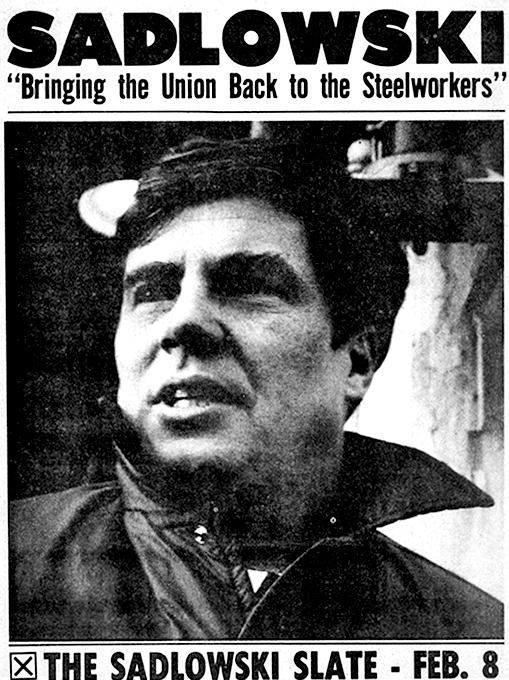

Learning and Building on the past: Notes from the Sadlowski Campaign for USWA President in 1976-77

By Garrett Brown

This is the first in a three-part Stansbury Forum posting on Steelworkers Fightback (SFB), a reform movement within the United Steelworkers Union in the 1970’s. Garrett Brown documents the issues and personalities that drove that movement. The series is of great relevance today and can help inform our understanding and appreciation of the reform movements underway in many large US unions. The International Brotherhood of Teamsters (IBT) has new leadership as does the United Auto Workers (UAW). In the United Food and Commercial Workers union (UFCW), America’s largest retail union, there is an active opposition called Essential Workers for Democracy. They had a big presence at the union’s most recent convention in April and are actively pointing toward the 2028 convention.

Peter Olney, co-editor of the Stansbury Forum

.

Introduction

In 1976, I was a member of the Socialist Workers Party wroting articles for the party’s weekly newspaper, The Militant, under the pen name of “Michael Gillespie.”. I was also the labor reporter for The Daily Calumet newspaper in southeast Chicago, in the heart of the Chicago-Gary steelmaking industry where almost 130,000 steelworkers formed a key part of the national economy and were the largest district of the United Steel Workers of America (USWA) union. I covered the numerous local unions of the USWA, which then had 1.4 million members in the Chicago-Gary region. The biggest story during my days at the newspaper was the election campaign of Ed Sadlowski and the Steelworker Fight Back (SFB) slate for international officers of the USWA leading up to the February 1977 election.

The significance of the Steelworkers Fight Back campaign was that it was part of a wave of efforts by rank-and-file union members to fight for union democracy, and to remake their unions into more militant defenders of the rights and needs of their members, including not only economic issues but also addressing historic discrimination against Black, Latino, and women steelworkers. This effort continues today – almost 50 years later – as a new generation of working class leaders seek to organize new unions in their workplaces and to reshape their existing unions as democratic and militant organizations that can defend them on the job.

Part 1 – The right moment and the right campaign

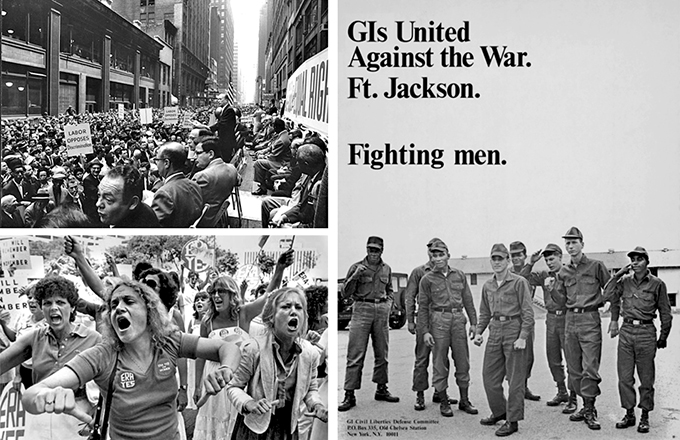

Upper Left: Charles Zimmerman speaks at a civil rights rally in the New York Garment District on 38th Street near 7th Avenue in New York City. Signs include “Labor Opposes Discrimination” May 17, 1960 Creative Commons/Kheel Center | Lower Left: Women demonstrate in favor of ERA. Tallahassee, Florida around 1979. State Library and Archives of Florida. | Right: Poster: GIs united against the war, Ft. Jackson. 1069. Library of Congress

The impact of the 1977 USWA presidential election campaign was generated by “the moment” in which it occurred. This moment included the previous decade of widespread social activism for civil rights, an end to the war in Vietnam, women’s rights, protection of the environment, and what was then called gay liberation. These social change ideas and movements had the biggest impact on young people, but also affected growing numbers of older working-class people, including steelworkers. Older workers may not have signed on to the full agenda of their children’s radical proposals, but many were more open (while some were not) to considering reforms to the “way it has always been.” The Watergate scandal culminating in Nixon’s August 1974 resignation called into question many elected institutions in the U.S. society as well.

At the same time the “social contract” in American society that existed between employers and unions between the end of the Second World War in 1945 and the bankruptcy of New York City in 1975 – in which unions were guaranteed modest improvements in wages and benefits in exchange for support for American capitalism and the U.S. government’s economic, political, and military exploitation of the rest of the world – broke down.

Even the more-protected sector of American workers (white men with unions) began to be subjected to what became known as the neo-liberal austerity regime, as maximizing the profits for corporate shareholders became the central and overriding concern of management. This meant increased wages and benefits first slowed, and then employers sought cuts; intensified productivity drives to increase output; cutting costs for protecting worker health and the environment; and squeezing the last penny of profits from operations by reducing re-investments in facilities, equipment, and preventive maintenance.

The unions’ leaderships – epitomized by the USWA – were completely unprepared and without alternative proposals when employers simply tore up the 30-year-old social contract and began dictating the terms of their newly intensified profit-maximizing regime. The pro-business unionists’ response was to seek even closer collaboration and partnerships with management – such as the management-union Experimental Negotiating Agreement (ENA) which banned strikes and required mandatory arbitration of contract issues, joint lobbying for tariffs on foreign steel, and other campaigns to raise industry profits.

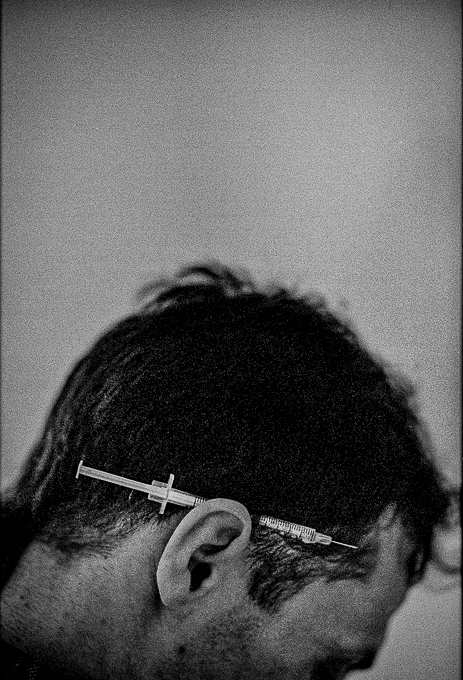

Steelworkers, like other union workers, faced worsening conditions on the job including compulsory over-time, relentless employer “productivity” programs, health and safety hazards generating immediate injuries and long-term diseases, unfair disciplines and dysfunctional grievance procedures. Moreover, the persistent racial discrimination in the mills and lack of representation in the union generated an ad hoc civil rights movement in the industry and union. Women, who were coming into the mills in greater numbers, also faced discrimination and often intense levels of harassment and assault.

This combination of factors sparked worker actions on the job, and efforts to recast their unions with greater internal democracy and militancy toward their employers. The period between 1965 and 1975 witnessed a strike wave greater than any other period after World War II, and on par with the great strike years of 1919, 1937, and 1947. There were an average of 350 “major strikes” (involving more than 1,000 workers) per year in the 1965-75 period, and some 5,000 “non-major strikes.” About 30% of the strikes were “wildcat” strikes – unofficial work stoppages organized by the workers and not sanctioned by union officials. The high point of the strike wave was 1970 when workers struck General Motors, General Electric, the railroads, and two major wildcat strikes of postal workers in New York City and Teamster union truck drivers.

The worker response to worsening conditions was reflected in their unions as well. In 1969, members of the United Mine Workers union began an effort to oust W.A. “Tony” Boyle, a corrupt and violent president, resulting in the election of the Miners for Democracy (MFD) slate in December 1972. In 1973, Sadlowski and his supporters launched their campaign to first change District 31, with plans in mind for a national change in the 1977 USWA presidential election. In 1976, members of the Teamsters union founded Teamsters for a Democratic Union (TDU), which led heroic efforts to reform the mobbed-up, Jimmy Hoffa-led union until a reform candidate won the presidency in 1991.

The SFB election campaign was an example of “the right campaign” meeting “the right moment” with national implications for the labor movement. The campaign’s central themes of union democracy and union militancy were reflected in the slate of candidates, the program and position on critical issues, and the response of the steelworkers who joined and promoted the effort. Its significance was also seen in the extensive media coverage in national and local newspapers, national magazines, and television reporting (including formal candidate debates on a local Chicago station, national NBC’s “Meet the Press,” and the syndicated Tom Synder show).

The face of the campaign was Edward Sadlowski, born and raised in South Chicago and a third-generation steelworker. His father, also Edward but known as “Load,” had helped organize the USWA at Inland Steel in the 1930s, and Eddie’s grandfather had come over from Poland at the end of the 19th century to work in the mills. Eddie grew up fascinated by labor history, and he had a real interest in learning about not only the events and leaders of the union movement, but also the songs, stories, and culture of the multinational American working class’ efforts to organize, defend itself, and improve their lives over the course of the previous century.

In 1956, Sadlowski started as a 18-year-old machinist apprentice at US Steel South Works. He was not a much of a machinist, so he was given an oil can and told to lubricate cranes and other equipment throughout the plant. Thus was born “Oil Can Eddie” – a nickname that Sadlowski did not care for as it represented a demotion from his machinist apprenticeship – but it meant that Eddie spent his days at work talking to dozens of co-workers throughout the mill.

In 1960, Sadlowski was elected shop steward, and in 1962 was elected to the union grievance committee. In 1964, at the age of 25, Sadlowski became the youngest local union president at Local 65, representing the then 14,000 workers at the mill. Eddie was re-elected as Local 65 president in 1967. In 1970, Sadlowski was appointed as an international staff representative, one of 60 staff men in District 31 servicing the district’s 295 local unions.

In 1972, Joseph Germano, who had been District 31 Director since 1940, was required to retire by the USWA constitution. In his eight terms as district director, Germano had only faced one election challenger, and Germano had hand-picked Samuel Evett to succeed him. Evett had become a union staffer in 1936 and was Germano’s assistant director for the 32 years since 1940.

The USWA had always been a top-down organization, from the time the United Mine Workers union chief John L. Lewis assigned Phillip Murray to run the Steel Workers Organizing Committee in the 1936. Murray was USWA’s founding president from 1942 until his death in 1952 and ran a highly centralized organization. In 1973, the USWA’s international union President I.W. Abel, its Vice President and Secretary-Treasurer all ran unopposed for re-election, as did 14 of the 25 district directors. The USWA had an almost feudal dynasty feel from the Pittsburgh headquarters through the 25 districts to the 5,400 local unions.

Sadlowski decided to challenge the “Official Family” tradition of hand-picked successors, and run on a campaign of union democracy, union militancy and “social movement” unionism versus the “business unionism” represented by Evett and the union leadership in Pittsburgh.

Sadlowski announced the 1972-73 campaign for District 31 Director stating:

“I consider democracy within the union to be the most important single issue. If the steelworkers had been consulted, they never would have agreed to an International Executive Board which excluded Blacks, Latinos and women. If the steelworkers were consulted, they would insist on their right to vote on union contracts in the same manner that other unions do. They rightfully feel they are not running their own affairs and they are not being represented on the district level.”

The election was held on February 13, 1973, and at midnight Sadlowski was leading Evett by about 3,500 votes. The vote counting was halted, and when it resumed the following day, Evett was declared the winner by a margin of 2,350 votes.

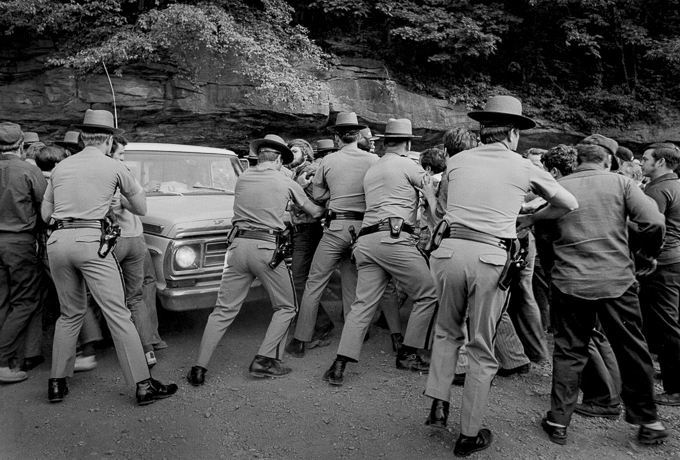

Sadlowski protested the election results, and a U.S. Department of Labor investigation found that there had been massive fraud in the election – including ballot box stuffing in Local 1014 at US Steel Gary Works – as well as misuse of union funds, and improper electioneering by international staff. A Federal court battle ensued, and in July 1974, Evett and the Pittsburgh headquarters agreed to a settlement, under pressure, for another election to be conducted by the Labor Department.

In the November 1974 re-run election, the member turn-out increased by 25% over the February 1973 vote, and Sadlowski won the re-run by 20,000 votes and a margin of 2 to 1. Sadlowski took office as District 31 Director in direct opposition to most policies of the union hierarchy and despite their best efforts to defeat him. With the centralization of power in the USWA, almost all of the reforms Sadlowski proposed during the District 31 campaign could be achieved only with a new leadership in Pittsburgh. Planning for the presidential campaign began in the wake of the 1973-74 district campaign.

Between the 1974 district director and the 1977 presidential races, there were important local union elections, and the campaign to replace Sadowski as district director since he had to give up the regional post for the national election in 1977.

Local union officer elections in April 1976 had resulted in supporters of SFB being elected by large margins. At Local 65 at South Works, SFB supporter John Chico beat Frank Mirocha by almost two to one (2,228 to 1,304 votes) with a near record turnout of the local membership. Chico’s slate of candidates won eight of the 10 other offices up for election. Mirocha was personally backed by corrupt Chicago Alderman “Fast Eddie” Vrdolyak, who was successful in installing his candidate for president, Tony Roque, in the non-USWA, company-dominated union at Wisconsin Steel. Vrdolyak intervened in the 1977 elections as well – opposing Sadlowski and District 31 Director candidate Jim Balanoff.

In April 1976, at Inland Steel across the state line in Indiana, Jim Balanoff also won by nearly two to one (6,050 to 3,067) over Hank Lopez, and the SFB supporter slate took eight of the nine other offices. The vote at Inland was also near-record with 12,000 of the 18,000 members casting ballots. During this election, as was the case with Balanoff’s previous and subsequent election campaigns, The Daily Calumet played a minor role. In 1947, when Congress was passing the Taft-Hartley Act which greatly restricted the rights of unions, Balanoff sent a letter to the Daily Cal opposing the bill, which was published and which he signed as a member and local organizer of the South Chicago branch of the Communist Party. So at every union election, Balanoff’s opponents came by the Daily Cal office to make another copy of the letter from the paper’s archives.

After his Local 1010 victory in April, Balanoff became the SFB candidate for District 31 Director in the February 1977 election. In contrast to the Joe Germano days, the district director race drew 12 candidates, five of whom garnered enough local union nominations to appear on the ballot. One of those was John D. Carey, the sitting president of the Chicago Board of Education, who had been a USWA international staffer for 15 years and a local union president for 10 years before that. Balanoff won the district director election by nearly 6,000 votes over his nearest challenger (19,108 to Harry Piasecki’s 13,442). Four of the five candidates supported McBride, which likely increased McBride’s District 31 vote with local candidates campaigning on his behalf.

The basic strategy of the 1976-77 SFB campaign was to combine the District 31 campaigns (district director and local union presidents, 1973-76) with key features of the 1972 Miners for Democracy campaign, including high-profile media work, a legal strategy to engage the federal government against fraud, and outside fundraising to counterbalance the union officialdom’s resources. There was not a national network of USWA reform organizations in existence, and not enough time (summer 1976 to February 1977) to create a new representative network, let alone conduct the years-long, patient building of local grassroots organizations of reform-minded steelworkers. So the strategy focused in building a centralized campaign organization led by trusted Chicagoans, with some outside help, that would direct and coordinate campaign volunteers.

It was clear that the SFB campaign tapped into a deep reservoir of concerns among working steelworkers and interest in hearing about alternative approaches. The slate received 521 nominations from local unions – 140 nominations were required for ballot status – despite the refusal of the Pittsburgh headquarters to provide a complete list of the USWA’s local unions. Volunteer supporters set up campaign offices and conducted plant-gate leafleting, rallies, and fundraising events around the country. Campaign events for Sadlowski in Pittsburgh, Baltimore, and numerous other steel towns had higher attendance and much more enthusiasm than the Official Family events.

The potential impact of a successful SFB campaign on the labor movement and industrial relations in general was not lost on the many affected parties. Sadlowski was vociferously denounced by union officials including I.W. Abel, former AFL-CIO leader George Mean and his successor Lane Kirkland, and national teachers union president Albert Shanker, among others. Steel industry officials, including lead contract negotiator J. Bruce Johnson of US Steel, warned of “chaos” should Sadlowski become president. Newspapers like the Wall Street Journal, New York Times and Chicago Tribune all editorialized against a SFB victory. The newspapers’ labor reporters – anxious to maintain good relations with labor officialdom – routinely belittled SFB’s prospects, while also drawing a dark picture of a Sadlowski presidency.

At the same time, the SFB campaign became a pole of attraction not only for steelworkers wanting change in their union and mills, but also for rank and file members of other unions, and those seeking social change for people of color and women in society at large. Radicals, and liberals with money, were excited by, and contributed to, the latest labor battle of David versus Goliath.

Next: Part 2 – David v. Goliath in the USWA

…

The Teamsters’ UPS Strike of 1997: Building a New Labor Movement

By Rand Wilson and Matt Witt

The Forum revisits the August 1997 strike at UPS by republishing an article written by two former Teamster staffers. Rand Wilson and Matt Witt worked in the Communications Department at the International Brotherhood of Teamsters (IBT) and played major roles in helping members to build unity and wage a successful two week strike. Over 25 years later, what lessons can be learned as over 340,000 Teamster members at Big Brown are negotiating for a new agreement and preparing for a strike if necessary when the contract expires on July 31, 2023? – Peter B. Olney

.

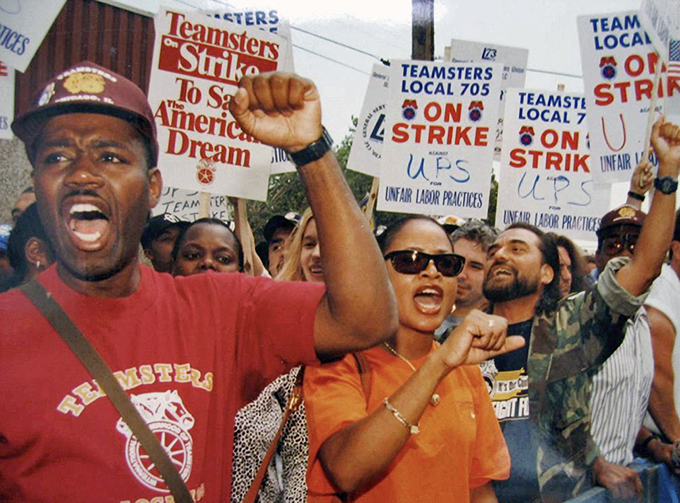

At a time when the American labor movement is struggling to reverse its decline in membership and strength, the Teamsters’ nine-month contract campaign at United Parcel Service in 1997 demonstrated that labor can rebuild its power by involving its members, reaching out for public support, and challenging corporate power on behalf of all working people.

Twelve days into the two-week, nationwide United Parcel Service strike in August 1997, fifty workers at the RDS package delivery company in Cincinnati voted to join the Teamsters Union. The company tried to talk them out of it, asking why they would want to join an organization that had led 185,000 people out on the street with only $55 per week strike benefits. But even without knowing what the strike’s outcome would be, the RDS workers were attracted, not repelled, by the UPS Teamsters’ strong stand. “UPS workers came down in the mornings and afternoons and talked to us about why they were on strike and how they were fighting to stop the company from contracting out their work,” said RDS driver Daniel Jordan. “They showed that they were behind us, and we saw what we can do when we’re united” (The Teamster, October 1997).

Soon after the strike, workers ranging from retail department store employees in Orange County, California, to manufacturing workers and public employees in Pittsburgh began to call local unions in their areas, wanting information about organizing. In Washington State, 4,000 corrections officers who had an ineffective, unaffiliated association voted to become Teamsters. “A lot of us watched the UPS strike, and it gave us a major push toward the Teamsters,” said corrections officer Jim Paulino. In Ohio and in Canada, part-time, low-wage workers at McDonald’s were inspired to try to organize (The Teamster, March 1998; Vancouver Province, March 1998).

In all, the Teamsters Union had more organizing success in 1997 than in any year in recent memory, and the UPS victory inspired unorganized workers to contact many other unions as well (The Teamster Organizer, Spring 1998). “The UPS strike directly connected bargaining to organizing,” commented AFL-CIO President John Sweeney. “You could make a million house calls, run a thousand television commercials, stage a hundred straw- berry rallies, and still not come close to doing what the UPS strike did for organizing” (Sweeney, 1997, 8).

Far from scaring away workers from “irresponsible” unions, the Teamsters’ UPS victory drew the broadest public support the labor movement has enjoyed in years. Of the 185,000 UPS workers covered by Teamster representation, more than 184,000 took part in the strike. Thousands of members of other unions joined in the picketing and other events. Polls showed that the general public supported the strikers by more than two to one (Field, August 15, 1997; Greenhouse, August 17, 1997).

At a time when the labor movement is struggling to reverse its decline in membership, power, and relevance in American life, the nine-month UPS contract campaign that led up to the strike provided some valuable lessons. The campaign proved that working people will be attracted to a labor movement that is:

- a movement of workers, not just officials;

- a movement for all workers, not just its members; and

- a fighting force for working people, not just a bureaucratic service institution or a junior partner with management.

A Movement of Workers

Like most historic victories, the seeds of the rank-and-file contract campaign at UPS were planted many years before. In the 1970s, UPS workers began to organize in reform groups like UPSurge and Teamsters for a Democratic Union (TDU) to challenge a union culture that discouraged membership participation and was based on backroom deals between top union officials and management (La Botz, 1990, 61).

Reformers argued that weak contracts and a failure to enforce members’ rights were a direct result of a lack of union democracy. A typical example was the shift at UPS to lower-wage, part-time jobs. The shift had started in 1962 under a deal between Jimmy Hoffa, Sr., and UPS to allow the company to use part-time workers. Then, in 1982, Hoffa’s old-guard successors agreed to freeze the starting part-time wage at $8 per hour (The Teamster, November/December 1996). By 1990, about half of all UPS workers were part-timers, with the percentage growing fast (Teamsters Research Department, June 1997, 3).

In 1991, Teamster members had their first chance in history to directly elect their top International Union leadership. The result was a victory for a reform slate headed by Ron Carey, a twelve-year UPS driver and longtime elected local union leader (Crowe, 1993). Despite unrelenting opposition from many old-guard local union officials who benefited from the traditional top-down culture, the reformers began to change “contract negotiations” conducted by union representatives and management into “contract campaigns” that involved members at every step. Like progressive leaders in other unions, Teamster reformers understood that the power of a huge multinational company like UPS cannot be challenged just by a few officials sitting at a negotiating table (Center for Labor Education, 1990; Service Employees, 1988).

The 1997 struggle for a new contract with UPS became a prime example of the new-style contract campaign. It was designed to overcome a management contract campaign that had several key strategic elements.

First, the company demanded givebacks, even though it was making more than a billion dollars per year in profits. UPS proposed shifting even more work to lower-wage part-timers. It wanted to expand subcontracting, which would reduce promotion opportunities for UPS workers. It offered lower wage increases than in the past, with no special raises to help close the pay gap between part-time and full-time workers (UPS Contract Proposals, March 27, 1997). Even if management’s demands didn’t prove successful, they would help the company in negotiations to counterbalance any worker proposals for improvements.

Second, the company expected to take advantage of divisions between reformers and old-guard local union officials. This strategy was based in part on management’s reading of a one-day national safety walkout at UPS called by reform leaders in February 1994, when the company unilaterally raised the package weight limit from 70 to 150 pounds. While the safety action forced the company to provide greater protection when handling the heavier packages, many old-guard local leaders urged their members not to walk out (Associated Press, February 8, 1994). The lesson management drew was that the top union leadership did not have the support of old-guard locals and could not call or win a national contract strike (Blackmon and Burkins, August 21, 1997).

Third, UPS sought to exploit the division in the work force between part-timers and full-timers. Management assumed that full-timers wouldn’t fight for more full-time opportunities and better pay for part-time workers, while the younger part-time work force wouldn’t fight for better pensions or reduced subcontracting of full-time jobs.

Fourth, UPS unilaterally launched a so-called “Team Concept” program two years before contract expiration in order to further divide worker from worker. Like many similar programs established by other employers, UPS’s Team Concept scheme used words like “cooperation” and “trust” to appeal to workers’ natural desire for peace on the job (Nissen, 1997; Parker and Slaughter, 1994; Wells, 1987; Witt, 1979). But the scheme’s fine print allowed the company to replace the seniority system with management favoritism and set up “team steering committees” that could change working conditions without negotiation with the union. Teams would take on some functions of supervision, pitting union members against each other over issues like job assignments and work loads (Teamsters UPS Update, November 1995; Walpole-Hofmeister, 1996).

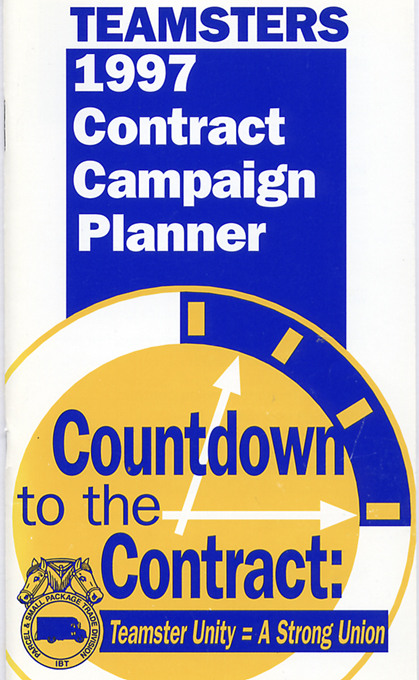

For the union, the key to countering management’s strategy was to build membership unity (The Teamster, March/April 1997). Nine months before the contract was set to expire on July 31, 1997, the International Union sent a contract survey to all UPS Teamsters’ homes. The survey asked them not only to rank their priorities but also to mark activities in which they would participate in order to get a good contract: “Wear buttons or T-shirts,” “Pass out leaflets,” “Ask coworkers to sign petitions supporting our bargaining demands,” “Conduct parking lot meetings with coworkers,” “Phone bank members about contract issues,” and “Attend special UPS local union meetings” (1996 UPS Teamster Bargaining Survey; Greenhouse, August 25, 1997).

Local union officials, stewards, and rank-and-file activists were provided with leaflets and an eight-minute video, Make UPS Deliver, to help them use the survey as an organizing tool to talk to members about the importance of getting involved in the contract campaign.

In these materials, members and reform leaders emphasized the common interests of part-time and full-time workers. For example, part-time workers would benefit if full-timers’ pensions were improved because that would lead to more early retirements, which in turn would open up more full-time promotional opportunities for part-time workers. Meanwhile, said Teamsters Parcel Division Director Ken Hall in the video, “It’s important to full-time employees that part-time employees get their fair treatment in this contract because if they do, there’s going to be less incentive for UPS to continually erode full-time jobs and replace them with part-time jobs.”

To help organize membership involvement in the 206 Teamsters locals with UPS members, the International’s Education Department provided training on how to set up “member-to-member” communication networks. These networks made each steward or other volunteer responsible for staying in touch with approximately twenty workers—giving them information, answering their questions, and listening to their views (Countdown to the Contract, July 1996). The networks counteracted UPS management’s systematic communication system that provided frequent messages for supervisors to review with employees in “Pre-Work Communication Meetings.” Management’s messages typically were about competitiveness, productivity, and the need to avoid a strike or community outreach campaign by the union that would drive customers to other companies.

The International assigned nineteen field staff, including some rank- and-file UPS workers, to help locals set up their networks and get members involved. In cases where old-guard local officials refused to take part in the campaign, the field staff worked directly with rank-and-file activists and stewards to build membership unity (Moberg, 1997).

In the months before contract expiration, the networks were used by some locals to organize membership participation in a series of escalating actions that built unity among full-timers and part-timers:

- On the day before union and company negotiators exchanged proposals, Teamster members held worksite rallies in seven targeted cities. The next day, UPS negotiators complained that rallies like that had never been held so long before the contract expired. Their complaints encouraged Teamster leaders to double the number of rallies held before the next bargaining session two weeks later (Greenhouse, August 25, 1997).

- The union provided members with the tools to document the company’s record as one of the nation’s worst job safety violators (Drew, 1995). More than 5,000 members filled out special “EZ” safety and health grievance forms. The grievances became the centerpiece of local “Don’t Break Our Backs” rallies where injured UPS workers spoke (Teamsters UPS Update, May 30, 1997).

- Another, larger round of rallies focused on job security. Tens of thousands of members blew high-pitched whistles both inside and outside UPS facilities to show management their determination to win gains on issues such as subcontracting (Mitchell, 1997).

- About six weeks before contract expiration, the organization and unity built by the member-to-member networks paid off as more than 100,000 Teamsters signed petitions telling UPS that “We’ll Fight for More Full-time Jobs” Teamsters UPS Update, July 7, 1997). Part-time package sorters and full-time drivers marched together in public demonstrations in cities like Memphis and San Francisco and held rallies throughout the country {The Teamster, August/September 1997). “In years before, we weren’t as unified,” said part-timer Brad Hessling in St. Louis. “Feeder drivers would sit over here and have their own break room and package car drivers would sit over there and part-timers over there. But early on this year we were talking together and I learned about other people’s issues. By the end, we had enough reasons that we could all stick together.”

As workers united, they began to see their own power. At UPS’s distribution center in Jonesboro, Arkansas, Teamster members came to work wearing contract campaign stickers. Their supervisor fired the union steward and told the other workers to take their stickers off or leave. They left—to talk to a local television station. Late that night, higher management called to apologize and assure the workers that if they came back to work they would be fully paid for the time they missed (Convoy Dispatch, August 1997).

In coordination with the union’s field organization, the Teamsters communications strategy was geared toward building a contract campaign that got workers involved. While UPS spent more than a million dollars on newspaper advertising containing pronouncements from corporate headquarters, the union spent no money on advertising at all. Instead, the union concentrated on organizing rallies and other actions that attracted the news media and where rank-and-file workers were among the featured speakers (Nagoumey, 1997; Candaele, 1997). Bulletins, videos, and other materials featured both full-timers and part-timers telling why they were getting involved in actions to win a better contract for all. To help members speak for themselves, the union provided a steady stream of information through a toll-free hotline, the Teamsters Internet web page, a special electronic “listserv” mailing list for rank-and-file activists, and national conference calls that could be heard at every local union hall.

When the union obtained an audio tape that top UPS negotiator Dave Murray had sent to all supervisors, it prepared its own tape for Teamster stewards to share with rank-and-file workers (Business News Network for UPS Managers, March 1997). Instead of featuring union officials debating the UPS executive, the union’s tape alternated excerpts of Murray’s tape with responses from UPS workers. Murray said that not only was $8 an hour an adequate part-time wage, but in many areas it would be “a fine full-time wage.” Part-timer Adrian Herrera from southern California responded, “I know that they’re making money on our backs. Even if they would give us raises, they’d still make a hell of a good profit” (From the Horse’s Mouth, 1997).

Murray’s taped message also criticized Teamster leaders for keeping members informed on the progress of negotiations. “In the past,” he said, “commitments were made to not speak to the members or the employees for whom the contract is being negotiated. The reason this was usually viewed as a wise position for both parties was that the communication of positions taken during negotiations often raises the expectations of those people who ultimately could be voting on the ratification of the agreement.” Herrera disagreed, saying that “as long as we can make our people aware of what’s going on in the contract, I think we’re better off.”

A Movement for All Workers

From the beginning, the union’s contract campaign at UPS was designed to build the broad public support that would be needed to either win a good contract without a strike or win a strike if that became necessary. For nine months, union communications stressed that the campaign was not just about more cents per hour for Teamster members but about the very future of the good jobs that communities need. Teamster members, in turn, emphasized the same message when talking to the news media and to family, friends, and neighbors.

Local union leaders and activists were encouraged to invite community organizations to rallies and other activities. Many locals organized “Family Days” that symbolized the importance of good jobs for working families. UPS pilots, who belong to a separate union, and Teamster members from other industries took part in many campaign activities (The Teamster, August/September 1997).

The importance of the fight for good jobs in today’s global economy was highlighted by a day of rallies by UPS workers not only in the U.S. but in seven European countries, where the company had invested billions of dollars in trying to expand its operations (Teamsters UPS Update, May 30, 1997; Wall Street Journal, May 22, 1997). At the UPS center in Gustavsburg, Germany, workers handed out leaflets and stickers, wore white socks as a symbolic show of unity, and blew whistles like those being used by Teamster members at actions in the U.S. “The management obviously was alarmed,” reported German shop steward Bruno Hingott, “but I don’t know if because of the international UPS action day, or because of the presence of the district manager who was watching what his most dangerous works council and union group were doing.”

With the groundwork laid for community support, activities to show that Teamster families were fighting for all workers escalated once the strike started. A story that ran on the Reuters wire a few hours after picket lines went up quoted a rank-and-file UPS driver, Randy Walls from Atlanta, saying, “We’re striking for every worker in America. We can’t have only low service-industry wages in this country.” In some areas, striking UPS drivers traveled their regular routes by car, sometimes accompanied by a part-timer, to explain to their customers the broad significance of the strike (Greenhouse, August 25, 1997; Teamsters UPS Update, August 8, 1997). In Seattle, 2,000 people formed a human chain around a UPS hub (Teamsters UPS Update, August 13, 1997). More than 2,000 telephone workers marched in Manhattan to show their support (‘Teamsters UPS Update, August 11, 1997). U.S. Senator Paul Wellstone of Minnesota, Reverend Jesse Jackson, and other national and local politicians walked picket lines (Cassidy, August 9, 1997).

In the union’s national news conferences, rank-and-file workers were

visible spokespeople, emphasizing the importance of the strike issues to all working families. For example, at a news conference in which John Sweeney announced millions of dollars in loan pledges from other unions to maintain strike benefits, part-timer Rachel Howard and veteran driver Ezekiel Wineglass were featured speakers, talking from the heart about America’s need for good full-time jobs and pensions (America’s Victory, 1997).

On August 15—twelve days into the strike—the union announced a major escalation of community activities that would show that the UPS workers’ fight was “America’s fight” (Greenhouse, August 16, 1997; Swoboda, August 16, 1997). Labor-community coalitions such as Jobs With Justice planned actions in some cities to target retail companies such as Kmart and Toys-R-Us that had called on President Clinton to end the strike—not surprising since retail companies are prime abusers of part-time, lower-wage workers. Local Coalitions for Occupational Safety and Health (COSHs) planned news conferences and demonstrations highlighting how UPS had paid academics to help attack federal job safety rights for all workers (National Network of Committees on Occupational Safety and Health, Summer 1997). National women’s groups geared up a series of actions focusing on the effect on women workers when good jobs with pension and health benefits are destroyed.

“If I had known that it was going to go from negotiating for UPS to negotiating for part-time America, we would’ve approached it differently,” UPS vice chair John Alden later told Business Week (Magnusson, 1997).

A Fighting Force for Working People

While some argue that unions must shun the “militant” image of the past in order to maintain support from members and the public, the UPS experience shows the broad appeal of a labor movement that is a fighter for workers’ interests. The union showed its members and the public that it sought solutions to problems, not confrontation for confrontation’s sake. But it also showed that it was willing to stand up to corporate greed when push came to shove.

The first signals came in the one-day safety walkout in February 1994, when Carey drew the line after weeks of seeking a reasonable solution to the company’s demand to raise the package weight limit from 70 to 150 pounds without necessary precautions to protect workers’ safety. It was a rare, if not unprecedented, national union job action over a safety and health issue. Within hours, the company signed an agreement it had been unwilling to make before the walkout (Settlement Agreement, 1994).

Two months later, in April 1994, the International Union led a three- week strike against the major trucking companies in the freight hauling industry in order to stop management from creating $9 per hour part-time positions. The message could not have been more clear: the “throwaway worker” strategy that old-guard officials had permitted for years at UPS would not be allowed to spread to the freight companies by the new International Union leadership (Teamsters Freight Bulletin, April 29, 1994).

Then, in 1995, Teamsters mounted another apparently unprecedented national union campaign—this time to defeat the labor-management “cooperation” scheme that UPS management tried to establish to weaken the union before the 1997 contract talks. The International Union coordinated a major membership education campaign highlighting the differences between the company’s promises of “partnership” and the program’s attack on rights under the union contract (The Teamster, January/February 1996). In addition to conducting training sessions at local unions, the International encouraged every union steward to share with other members a video and educational materials on the theme, “Actions Speak Louder Than Words.” Members were urged to ask the company why it didn’t demonstrate its commitment to “teamwork” by working with the union to create more full-time jobs, stop subcontracting, and improve job safety. A program that was supposed to divide Teamster members was turned by the union into an opportunity to build unity heading into national contract negotiations. In fact, the campaign against the Team Concept was so successful that in early 1998 UPS agreed in writing to terminate the program altogether (Parker, 1997; Schultz, 1998).

When bargaining for the 1997 contract began, top Teamster negotiators inspired members with a strategy for staying on offense. It had become common during the 1980s for union leaders to start negotiations by sounding the alarm to members about management demands for major concessions. “Victory” could then be measured not by gains won, but by giveback demands that were defeated. But when UPS management tried to set up that same dynamic by proposing big concessions, Teamster leaders broke off negotiations to show they weren’t willing to play along (Why Won’t Management Listen?, undated).

“This billion-dollar company must be living on another planet to waste our time with proposals like these,” Carey told members in a contract campaign bulletin. “These negotiations are about only one thing—and that is making improvements that will give our members the security, opportunities, safety, and standard of living that they deserve” (Teamsters UPS Update, May 30, 1997).

Union leaders also stood up to UPS’s proposal to take over workers’ health and retirement funds. The company proposed to leave the regional or local Teamster pension plans that cover union members from a variety of companies. Instead, UPS would set up its own pension fund that it would control. The pitch to UPS workers was that, as a younger work force, they could enjoy better benefits in their own plan. “By establishing a plan exclusively for UPS people, our hard-earned dollars would no longer subsidize the pensions of non-UPS employees,” management wrote in a letter to employees (Shipley, 1997).

UPS had raised the same proposal in past negotiations as a bargaining chip, taking it off the table at the last minute in return for union acceptance of other concessions (Teamsters UPS Contract Update, October 1, 1993)

But in 1997 the union refused to play that game, instead confronting the issue head on. Union leaders explained to members that by pooling retirement money from a large number of employers, Teamster plans provide better benefits and more security. When the stock market rises and pension funds earn extra investment income, that money stays in the Teamster plans to help raise benefits and provide protection for the future. In contrast, management’s plan would give the company the right to skim off extra investment income and use it for executive bonuses or any other purpose. With nine days to go before the contract would expire on July 31, 1997, Teamster leaders sent another clear signal that the union had become a fighting force for change. Management was demanding that the union accept a “final offer” and agree to a contract extension while details were worked out—arguing that customers would shift to other delivery services without immediate assurances that there would be no strike (UPS, Inc.’s Last, Best and Final Offer, 1997). But once again, the union refused to be put on the defensive. It ridiculed the idea that bargaining was over and continued to make counter proposals.

On July 30, management tried again, making another “final offer” and demanding that it be put to a membership vote. Again, the union stood firm. There would be a membership vote when the union committee had negotiated an agreement that met the needs of working families, and not before. At the request of a federal mediator, Teamsters negotiators bargained for three days past the deadline in a good-faith effort to reach a settlement. When management still wouldn’t budge, union members had no alternative but to strike.

During the walkout, the union showed it was a fighting force for working people by standing up not only to one of the biggest employers in the world but also to a variety of politicians trying to bring pressure for a settlement. Republican leaders such as House Speaker Newt Gingrich called on President Clinton to order the strikers back to work without a contract. The Clinton Administration tried to jawbone both sides. But Teamster leaders made it clear that the strike would not end until an agreement was reached that provided the good jobs that America needed (Greenhouse, August 11, 1997; Swoboda, August 12, 1997).

Seeing that the strike was building momentum as it headed into the third week and that public support was growing in both the U.S. and Europe, UPS management caved in on every major issue. The company agreed to create 10,000 new full-time jobs by combining existing part-time positions—not the 1,000 they had insisted on in their July 30 “last, best, and final” offer. They would raise pensions by as much as 50 percent—and do so within the Teamster plans, not under a new company-controlled plan. Subcontracting, instead of being expanded, would be eliminated except during peak season, and then only with local union approval. Wage increases would be the highest in the company’s history, with extra increases to help close the pay gap for part-timers. The only compromise by the union was to accept a contract term of five years instead of the four-year term of the previous agreement (Greenhouse, August 19, 1997).

The Teamsters 1997 campaign at UPS, like any contract fight, was affected by specific circumstances that wouldn’t always be present in other situations (Greenhouse, August 20, 1997). Years of rank-and-file organizing by TDU had laid the groundwork for effective contract campaign networks on the job. UPS controlled about 80 percent of the ground package delivery business, which ensured that a strike would have significant economic impact and bring pressure on the company to settle. The company was not a conglomerate with other major lines of business that could help it withstand the walkout. Because UPS delivers to every address in the U.S., the strike was a hometown story in nearly every city and town. Because it took place during August, when Congress was out of session in a non-election year, it was easier to generate maximum attention from the national news media.

Despite these particular factors, the campaign clearly demonstrated the importance of worker involvement and community outreach in building labor power, and that lesson was underscored when the union allowed its new power to slip away by abandoning those approaches after the strike. Three days after the strike was settled, federal overseers overturned Carey’s 1996 reelection victory, and three months later they forced Carey out of office because of campaign finance violations.

Sensing an opportunity to take advantage of a leadership vacuum, UPS management refused to combine part-time positions to create the 2,000 new full-time jobs required in the first year of the contract (Blackmon, 1998; Mitchell, 1998). With Carey no longer on the scene to lead a rank-and-file campaign, old-guard leaders who controlled most local unions reverted to their traditional “don’t-rock-the-boat” relationship with the company and did nothing to enforce the agreement. After one half-hearted round of public demonstrations, the International let old-guard locals and the company off the hook by seeking a solution only through the contract’s grievance procedure, a legalistic process whose outcome would depend on a decision by a neutral arbitrator after many months or even years of delay.

While the return to old ways demoralized many workers, others drew the same conclusions from the 1997 contract campaign that academic observers have drawn about the critical role played by rank-and-file unionism in revitalizing labor power (Clark, 1981; Mantsios, 1998; Moody, 1998).

“The whole experience started my hunger for knowledge about the labor movement in general, about the Teamsters in particular, and about what role I might have in changing the shop in which I work,” said driver Rick Stahl of Boston. “We now need to work on building a rank-and-file unity in this local that understands the importance of union representation and what democracy can mean to that process” (Convoy Dispatch, April 1998).

“People are just now learning what a union can do for them,” said UPS part-timer Kathy Gedeon. “We now feel like we have a say-so” (Johnson, August 6, 1997).

Gloria Harris, a UPS worker in Chicago where workers from diverse backgrounds joined together on picket lines, added that “we now feel more like brothers and sisters than coworkers.” “We all learned something about color,” she said. “It comes down to green” (Johnson, August 20, 1997).

Contact the authors at: rand.wilson@gmail.com

References

Actions Speak Louder than Words (1995). Teamsters videotape.

America’s Victory. The UPS Strike of 1997 (1997). Teamsters videotape.

“An Interview with UPS Corporate Labor Relations Manager Dave Murray” (1997). Labor Relations Update. Business News Network for UP5 Managers Special Edition (March).

Associated Press (1994). “Teamsters Union Ends Strike Against UPS.” Kansas City Star (February 8).

Blackmon, Douglas (1998). “UPS Nullifies Part of Teamsters Contract.” hell Street Journal

(July 10).

Blackmon, Douglas, and Glenn Burkins (1997). “UPS’s Early Missteps in Assessing the Teamsters Help Explain How Union Won Gains in Fight.” Wall Street Journal (August 21).

Candaele, Kelly (1997). “Teamsters Go for Public’s Heart.” Los Angeles Times (August 17). Cassidy, Tina (1997). “Omcials Join Teamsters at Rally.” Boston Globe (August 9).

Clark, Paul F. (1981). The Miners’ Fight for Democracy. Ithaca: Cornell ILR Press.

Countdown to the Contract: 199O—1997 Teamsters Contract Campaign Planner (1996). International Brotherhood of Teamsters pamphlet (July).

Crowe, Kenneth C. (1993). Collision: How the Rank and File Took Back the Teamsters. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Drew, Christopher (1995). “In the Productivity Push, How Much is Too Much?” New York Times (December 17).

Field, David (1997). “Poll: 55’7o Support Strikers at UPS.” USA Today (August 15).

From the Horse’s Mouth. UPS Management Debates Teamster Members on Our Next Contract (1997). Teamsters audiotape.

“Good Time to Help Organize” (1997). The Teamster Magazine (October): 4.

Greenhouse, Steven (1997). “United Parcel Asks Clinton to Intervene in Walkout.” New York Times (August 11).

Greenhouse, Steven (1997). “Long Hours Fail to Budge UPS Talks, Carey Says.” New York Times (August 16).

Greenhouse, Steven (1997). “In Shift to Labor, Public Supports UPS Strikers.” New York Times (August 17).

Greenhouse, Steven (1997). “Teamster Officials Report a Tentative Pact With UPS to End Strike after 15 Days.” New York Times (August 19).

Greenhouse, Steven (1997). “A Victory for Labor, But How Far Will it Go?” New York Times

(August 20).

Greenhouse, Steven (1997). “Yearlong Effort Key to Success for Teamsters.” New York Times

(August 25).

Half a Job Is Not Enough. How the Shift to More Part-time Employment Undermines Good Jobs at UPS (1997). Teamsters Research Department (June).

Holding the Line in ’89: Lessons of the NYNEX Strike (1990). Boston: Center for Labor Education Research.

Johnson, Dirk (1997). “Angry Voices on Pickets Reflect Sense of Concern.” New York Times

(August 6).

Johnson, Dirk (1997). “Rank-and-File’s Verdict: A Walkout Well Waged.” New York Times

(August 20).

La Botz, Dan (1990). Rank and File Rebellion. New York: Verso.

Magnusson, Paul (1997). “A Wake-Up Call for Business.” Business Week (September 1).

Make UPS Deliver (1996). Teamsters videotape.

Mantsios, Gregory (ed.) (1998). A New Labor Movement For the New Century. New York: Monthly Review Press.

Mitchell, Cynthia (1997). “Teamsters Break Off Talks, Criticize UPS.” Atlanta Constitution-Journal (May 23).

Mitchell, Cynthia (1998). “The UPS Strike Revisited: What Lessons Did They Learn?” Atlanta Constitution-Journal (August 2).

Moberg, David (1997). “The UPS Strike: Lessons for Labor.” Working USA (September/October).

Moody, Kim (1988). An Injury to All. The Decline of American Unionism. New York: Verso.

Nagourney, Adam (1997). “In Strike Battle, Teamsters Use Political Tack.” New York Times

(August 16).

Nissen, Bruce (ed.) (1997). Unions and Workplace Reorganization. Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

Parker, Mike, and Jane Slaughter (1994). Working Smart: A Union Guide to Participation Programs and Reengineering.Detroit: Labor Notes Books.

Parker, Mike (1997). “Fighting UPS ‘Teamwork’ Prepared Union to Win the Big Strike.” Labor Notes 224.

“One of the Best Organized Centers in the U.S.” (1997). Convoy Dispatch 161 (August).

“Over 30,000 Win Teamster Representation in 1997” (1998). The Teamster Organizer, Newsletter (Spring).

“Part Time, Full Time, Union Time” (1997). The Teamster Magazine (March/April): 6.

Schultz, John (1998). “Coercion or Cooperation?” Traffic World (March 2): 19.

SEIU Contract Campaign Manual (1988). Service Employees International Union and American Labor Education Center.

Settlement Agreement on Handling Over 70 Pound Packages (1994). International Brotherhood of Teamsters (February 7).

Shipley, Harry (1997). Letter to employees from UPS District Manager Harry Shipley (August 11).

“Strength In Numbers” (1998). The Teamster Magazine (March): 12.

Sweeney, John (1997). Keynote address at 22nd Constitutional Convention, AFL-CIO, Pittsburgh, PA (September 22).

Swoboda, Frank (1997). “Labor Official Calls in Vain for New Talks.” Washington Post (August 12).

Swoboda, Frank (1997). “Carey Says UPS Talks Making No Progress—Teamsters Call for Stepped-Up Strike Activities.” Washington Post (August 16).

Teamster Magazine (1997) (August/September): 3.

Teamsters Freight Bulletin (1994) (April 29).

“Teamsters Roaring Down on McD’s” (1998). Vancouver Province (March 19).

“Teamsters to Pressure UPS Through Rallies in U.S. and Europe” (1997). Wall Street Journal (May 22).

“Teamsters Uniting to Make UPS Deliver” (1996). The Teamster Magazine (November/December): 8.

Teamsters UPS Contract Update (1993) (October 1).

Teamsters UPS Update (1995) (November).

Teamsters UPS Update (1997) (May 30).

Teamsters UPS Update (1997) (July 7).

Tilly, Chris (1996). Half a Job.’ Bad and Good Part-time Jobs in a Changing Labor Market. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

UPS Contract Proposals (1997) (March 27).

UPS, Inc.’s Last, Best and Final Offer of Settlement for the National Master Agreement (1997) (July 22).

UPS’s Stealth Campaign Against OSHA: The Link to Scientists and Think Tanks (1997). National Network of Committees on Occupational Safety and Health (COSH) and the AFL-CIO Health and Safety Department (Summer).

“UPS Strike Showed Need For Union” (1998). Letter to the editor from Rick Stahl. Convoy Dispatch 167 (April): 11.

Walpole-Hofmeister, Elizabeth (1996). “UPS Establishes Teamwork Program: Encounters Resistance From Teamsters.” Daily Labor Report. Bureau of National Affairs (February 5).

Wells, Donald M. (1987). Empty Promises. Quality of Working Life Programs and the Labor Movement. New York: Monthly Review Press.

Why Won’t Management Listen? (undated). Teamster contract campaign leaflet.

Witt, Matt (1979). In Our Blood. New Market, TN: Highlander Center.

“Workers in Wonderland” (1996). The Teamster Magazine (January/February): 12.

1996 UPS Teamster Bargaining Survey (1996).

Cornel West: The primaries call

By Tom Gallagher

“The unfortunate fact is that a third party campaign in America just won’t add up”

Shortly after Cornel West announced his intent to run for president as the candidate of the People’s Party, The Nation’s John Nichols reported encountering some who “expressed sympathy for a third-party run, but suggested that West should forgo a People’s Party bid and, instead, campaign on the ticket of the Green Party—which has secured many state ballot lines across the country and has an established network of backers.” And voila, before the proverbial ink on that article could dry, West had announced his intention to seek that party’s nomination. Where some may see this rapid change as a sign of a poorly thought-out effort, others may applaud the campaign’s flexibility, but either way, here’s hoping this demonstrated malleability can extend to the suggestion of Ben Burgis’s Jacobin article: “Cornel West Should Challenge Biden in the Democratic Primaries.” History, specifically the starkly different experiences of the Ralph Nader and Bernie Sanders candidacies – and maybe even that of Eugene Debs – suggests the wisdom of the shift, but it’s the math of the situation that demands it. The unfortunate fact is that a third party campaign in America just won’t add up.

In announcing that “We’re talking about empowering those who have been pushed to the margins because neither political party wants to tell the truth about Wall Street, about Ukraine, about the Pentagon, about Big Tech,” West expresses a quite understandable “plague on both your houses” perspective of the sort that generally underlies third party efforts – and not just in the U.S. But what may be a viable political option in one country might not be one in another; it all depends upon the rules and laws that govern politics in the respective nations. Nothing illustrates the importance of the differences better than the contrasting experiences of the aforementioned Greens, who find themselves continuously embroiled in defending against charges of facilitating Republican presidencies, and that of their German namesake, arguably the foreign “third party” most familiar to Americans, a party that has successfully entered governments – on both the state and national level – on numerous occasions. Put in the most basic terms, we could say that the difference lies in the fact that where Germans operate within an “additive” political system, we Americans live in a “subtractive” one.

In the German system, generally described as “parliamentary,” while there is a president, the office is largely ceremonial, the real head of government being the prime minister who is chosen by a majority of the members of parliament, a majority that may, and usually does require the support of more than one party. So, after running an independent campaign, if the German Greens do not come in first or second – as they never have on the national level – recognizing that their members will consider one of the top two parties to be preferable to the other, or at least not as bad (for most that preference would be the Socialists over the Christian Democrats), they will try to work out a compromise with that party, with Green party leaders playing a minority role in a resulting government coalition, as Joschka Fischer famously did as foreign minister from 1998-2005. So, in the end, the effect will be that the votes cast for the Greens are added to those cast for the Socialists, thereby preventing the outcome least desirable to most of both parties’ voters – the Christian Democrats coming to power.

In our case, on the other hand, should West persist in running a third party presidential campaign, his potential voters will have no such option. Whether West actually considers a second Biden term as bad an outcome as a second for Trump – or a first for DeSantis – I can’t say, but I feel fairly certain that most voters open to his ideas do not. However, under our plurality-winner-take-all system of apportioning a state’s share of the Electoral College, after the voters have cast their votes for different parties there is no way that they can be recombined to block a Trump return. And while a third-party West vote might contribute to an anti-Republican majority in a particular state, it could also contribute to creating a Trump (or DeSantis) plurality in that same time. The system is in that sense “subtractive,” in that a voter who considers Trump (or DeSantis) the worst possible outcome but opts for a third-party subtracts a vote from the only anti-Trump vote count that matters in the end – that of the largest non-Republican party, which will be the Democrats, however welcome or unwelcome that may be to said voter.

And, in the end, should West be on a ballot line in a final election that results in a Republican presidency, the damage done to his reputation – and much more importantly, to the causes he champions – won’t be a matter of anyone proving his culpability. Ralph Nader has found himself embattled and subjected to abuse by people who couldn’t carry his briefcase, lo these last twenty-plus years, not because anyone can actually prove his candidacy enabled George W. Bush’s election. Defeat generally has numerous contributors and in this case the Democrats’ ill-advised Florida recount strategy and the Clinton Administration’s decision to shut down online efforts to match up potential vote swaps between Nader supporters in “battleground” states with Gore supporters in non-battleground states are factors often conveniently forgotten. But as anyone involved knows, or at least should know, in politics, perception counts for a great deal. And just as government employees are prohibited not only from actually having a conflict of interest, but from giving the appearance of conflict of interest as well, the wise political actor will realize that it can be just as important to avoid the appearance of causing an undesirable outcome as it is to avoid actually causing it.

At the same time, while the so-called “two party system” that governs our presidential elections looks like it will be in place for the foreseeable future, the two parties are not themselves immutable. Just a month before the West announcement, Peter Beinart made just that point in a New York Times opinion piece, “Imagine if Another Bernie Sanders Challenges Joe Biden,” arguing that the profound effect of the Sanders candidacy has been a major factor in Biden becoming “the most progressive president since Lyndon Johnson.” Pointing to the joint Biden-Sanders campaign working groups that shaped the 2020 Democratic National Platform, he notes that there was none devoted to foreign policy and that with “rare exceptions, Mr. Biden hasn’t challenged the hawkish conventional wisdom that permeates Washington; he’s embodied it. He’s largely ignored progressives, who, polls suggest, want a fundamentally different approach to the world. And he’ll keep ignoring them until a challenger turns progressive discontent into votes.”

To be sure, as Beinart notes, “A primary opponent would risk the Democratic establishment’s wrath.” And we quickly got a taste of that – in the generally left-wing Nation, no less – where, in her article “Cornel West Should Not Be Running for President,” Joan Walsh argued that even if West “were to run as a Democrat, like [Marianne] Williamson and the deeply off Robert F. Kennedy Jr., he would still hurt Biden, because a primary gives the bored, supine media a reason to hype “Dems in disarray” stories.” Walsh’s argument unfortunately is the type of thinking that held that Bernie Sanders should have minded his own business in 2016 and leave things to those who had already decided on Hillary Clinton, a nominee whose, shall we say, arms-length relationship with the working class resulted in the Trump presidency.

And, oh yes, there will be character assassination: For Walsh, “Williamson, West, and Kennedy are all, sadly, narcissists looking for the spotlight.” While we can reasonably ask people to be aware enough of the workings of the system so as to avoid possibly unintended outcomes, we cannot reasonably ask them to be silent. Perhaps a West primary candidacy would be useful, perhaps it wouldn’t, but running out new and different ideas is precisely what the primaries are for. Disagreement does not imply narcissism – or any other character flaw.

And what about Debs? Although his presidential efforts are now a hundred years past, the sterling reputation that his name still carries on the American left contributes to a lingering reluctance to engage with the Democratic Party that he left behind in favor of the Socialist Party. In 1912, the year of Debs’s greatest electoral success (his 1920 campaign from a cell in the Atlanta Penitentiary resulted in a greater number of votes, but a lower percentage, as it was the first year women had the vote), the Republicans’ 1856 supplanting of the Whigs in the national political duopoly was an event within the living memory of some. And indeed, that year the Republicans would be pushed out of the duo for the first time, as their former President Theodore Roosevelt ran a third-party challenge to their sitting President William Howard Taft and dropped him to third place. Debs actually beat Taft in three states and Roosevelt in two, and although he only had 6 percent of the total national vote, it was the first race where four different candidates exceeded 5 percent since the first Republican victory in 1860. It seemed that a big electoral shakeup might be on the horizon. It wasn’t. Neither of these anomalies has repeated. The third party impulse is all too understandable: It’s not just foreign policy where there is a serious critique of Biden to be made. The fact that it is legitimate to speak of him as the most pro-labor president since FDR is largely a statement about just how low the bar has been set. And remember, this is a man who said he’d veto a “medicare-for-all” bill if it came to his desk. But we are not living in a parliamentary system and we cannot simply wish one into existence. Hopefully, West’s supporters will prevail upon him to undertake his fight in the most effective arena that currently exists, where the greatest light-to-heat potential lies – the primaries.

…

A Few Recommended Books For The Summer

By Neil Burgess, Sandra Cate, Stuart Freedman, Peter Olney, Molly Martin, Gary Phillips, Myrna Santiago and Jay Youngdahl

Neil Burgess:

Black Sun (Photobook)

By Soren Solker | Edition Circle, Denmark 2021.

Ancient peoples thought you could read the future in the movement of birds. Solker’s astonishing pictures of murmurations might revive the idea. These are not photoshopped images, he says not a single bird has been added or excluded.

A life in Parts (Biography)

By Brian Cranson | Seven Dials 2017.

I’m not big on biography, but this is a straight-forward, down to earth memoire from an actor who knows how lucky he is to have got the parts he’s had. From a difficult family upbringing to Malcolm in the Middle’s Dad, to Breaking Bads, Walter White he expresses himself with warmth, humour and humility.

Sandra Cate

Free: A Child and a Country at the End of History

By Lea Ypi | W. W. Norton 2021

A young Albanian woman comes of age as her country breaks from its authoritarian, socialist past as a Soviet satellite to attempt a “free” capitalist path forward. With humor, compassion and keen observations, Ypi learns of the lies that shaped her worldview and yet opened her future, to confront the many shaded meanings of freedom.

When the Mountains Dance: Love, Loss and Hope in the Heart of Italy

By Christine Toomey | Weidenfeld & Nicolson 2023 (Amazon)

How do communities survive, thrive, or even disintegrate after major earthquakes? Christine Toomey considers these questions through a very personal lens — her beloved home in Amadola, Italy, damaged by the 2016 earthquake and the former home of a priest who asked the same questions of earlier earthquake tragedies. Her moving account, graceful and profound, encourages those living in earthquake-prone areas to meditate on their risks and consequences.

Stuart Freedman

Caste Matters

By Suraj Yendge. India Viking 2019 (Powell’s Books)

A really disturbing but important work on Dalits in India by a young Dalit scholar. Might be tricky to get because it’s published in India by Penguin/Viking but I finally got a copy

The Bell of Old Tokyo

By Anna Sherman. Picador USA 2020 (Powell’s Books)

A bit of a masterpiece in that it weaves reportage about Tokyo in with interviews about the bells at different points (usually temples) of the city and as such is a discussion about the wider and changing Japanese culture.

The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida

By Shehan Karuntilaka. W. W. Norton 2022 (Powell’s Books)

Won the Booker – A story told from beyond the grave by a Sri Lankan photojournalist. I can’t really say more because it’ll give the game an away – but it’s cracking.

Weaponsing Anti-Semitism: How the Israel Lobby Brought Down Jeremy Corbnyn

By Asa Winstanley OR Books 2023. (Powell’s Books)

Now, out of all the books, I think as a scholarly work of journalism this is the stand out. Absolutely forensic detailing of Israeli government interference in the democratic process (it also touches on Bernie). I read this in one sitting. TBH, I am only half Jewish and I don’t know how you feel about Israel or the Zionist project (you can probably guess my views) but this is a story that touches us all and it’s important.

Peter Olney

Our Migrant Souls: A Meditation on Race and the Meanings and Myths of “Latino”

Hector Tobar Farrar | Straus and Giroux 2023

A wonderful exposition on Latinos in the USA written by the son of Guatemalan immigrants, a prominent journalist in California. As its title suggests, it is a meditation not a political diatribe.

Mussolini’s Grandchildren – Fascism in Contemporary Italy

David Broder | Pluto Press 2023

Giorgia Melloni is the Prime Minister of Italy. Georgia Melloni traces her political roots to the Movimento Sociale Italiano, a direct descendant parliamentary party of Mussolini’s brownshirts. What does her election in 2022 mean for the future of democracy and politics in contemporary Italy? Broder, an astute observer of Italian history and politics, gives us a comprehensive analysis.

Molly Martin*

Half American: The Epic Story of African Americans Fighting World War II at Home and Abroad

By Matthew F. Delmont | Viking 2022 (Powell’s Books)

The US Army and military services were white supremacist organizations (they put it in writing). How Black soldiers, harassed and murdered in the South, fought for fair treatment and won.

God, Human, Animal, Machine

By Meghan O’Gieblyn | Penguin Random House 2021

What does it mean to be human in a world with AI? Philosophical but never boring.

Mr. Know-it-all: The Tarnished Wisdom of a Filth Elder

By John Waters | Macmillan 2019

Sometimes we just need a good laugh. Hilarious.

We Don’t Know Ourselves: A Personal History of Modern Ireland

By Fintan O’Toole | Bloomsbury Publishing 2021 (Powell’s Books)

How Ireland has remade itself.

Gary Phillips**

Fixit

By Joe Ide | Hachette Book Group 2023 To order

Joe Ide’s Fixit is the sixth outing of his unlicensed cerebral private eye, Isiah Quintabe, (IQ) a young Black man based out of East Long Beach, California. Isiah in his young life has faced down the likes of white supremacists, a serial killer, members of a triad, hunted down his brother’s murderer, and for his troubles earned a $25,000 bounty on his head leveled by another ‘hood gangster. As Ide realistically posits in this new outing, IQ is understandably exhausted and suffering from PTSD. The story starts with a bang when another whackjob from IQ’s past, a psycho hitman named Skip Hanson kidnaps his girlfriend Grace Monarova.

Hanson of course has captured Grace to draw IQ, or Q Fuck as he likes to refer to him, out to kill him. Utilizing this minimalist plot, the propulsive narrative doesn’t let up. There’s plenty of twists and turns, backtracks and backstabbing, and most importantly, illumination of character and edgy humor as the writer physically and psychologically challenges IQ, his running buddy Juanell Dodson and the villains too before he brings the reader to a slam-bam satisfying conclusion. You don’t have to read the previous books in this series to jump onboard the IQ train. Get your ticket now and ride.

Queenie: Godmother of Harlem (graphic novel)

By writer Elizabeth Colomba and artist Aurélie Levy | Sistah SciFi 2023

In the graphic novel Queenie: Godmother of Harlem by writer Elizabeth Colomba and artist Aurélie Levy the thrust of the main plot is her often bloody battle with Arthur “Dutch Schultz” Flegenheimer in 1933 New York City as he tries to muscle in on her action. While she also has to deal with crooked cops. For Stephanie “Queenie” St. Clair, born in Martinique, was a boss of the numbers racket in Harlem.

On any given morning for as little as a nickel denizens bet on what would be the ending three-digit number derived from the tabulation of the daily New York Clearinghouse total, arrived at as the result of trading among banks. The last two numbers from the millions column of the exchange’s total plus the last number from the balance’s total — both published in the late afternoon newspapers. In that way, no one could dispute what the winning numbers were. Dream books, soothsayers, a pigeon flying by an address over a doorway and so on were called upon to derive what might be the winning number combination. In the graphic novel there’s a two-page layout called “How to Run a Lottery Numbers Operation.”Throughout the story, which also includes flashbacks to St. Clair’s early days and the harrowing experiences that shaped her, Columba and Levy drop in other real life historical figures such as heavyweight champ Jack Johnson and conman spiritualist George Baker better known as Father Devine. St. Clair was more than a clever gangster as an opening scene depicts when various Harlemites comes to call at her office asking for a loan at a decent interest rate to seeking street justice. A deed possibly her erudite right-hand man Elsworth Raymond “Bumpy” Johnson (recently portrayed by Forest Whitaker in the Godfather of Harlem streaming series set in the early ‘60s with him and his friend Malcolm X) would dispense. As this graphic novel demonstrates, as well as prose efforts such as The World of Stephanie St. Clair: An Entrepreneur, Race Woman and Outlaw in the Early Twentieth Century Harlem by Shirley Stewart, Queenie’s life and times will reach a larger audience via her own TV series.

Myrna Santiago:

The Great Earthquake Debate: The Crusader, the Skeptic, and the Rise of Modern Seismology

Susan Hough | U of Washington 2022

This book focuses on the history of earthquake science in Southern California through the biographies of the two men most involved in the debates about whether Los Angeles was going to experience a devastating quake like the one in 1906 in San Francisco. It is a book about the history of earthquake science in the early 1930s, but by focusing on the two competing geologists, the author makes it lively and easy to digest. And you do learn a lot about what scientists thought they knew about earthquakes then. Spoiler alert: the big one IS coming.

Vagina Obscura: An Anatomical Voyage.

Rachel E. Gross | W. W. Norton 2023

If you ever wondered why women’s reproductive and sexual health still makes headlines because it is so bad, this book will give you a glimpse about why that is the case. The author reviews the many ways in which medical profession, medical schools, and researchers have failed to study basic female anatomy and the social reasons for it. And this is not ancient history, folks. This is today.

Jay Youngdahl:

The South: JIM CROW AND ITS AFTERLIVES

By Adolph L. Reed, Jr., from Verso

This is a personal book by Mr. Reed. It details experiences in Arkansas and Louisiana, during a time I lived in those states. Anything by him is important in trying to understand the confusion on the left today, especially for those living in fauxgressive enclaves in the US.

After Black Lives Matter

By Cedric Johnson | Verso 2023

Here is a new book I just bought and am starting to read which was written by one of the most important writers on class and race in the US (along with Mr. Reed).

…

* Wonder Woman Electric to the Rescue, by Molly Martin. Memoir, Essays, and Short Stories by a trailblazing tradeswoman. All proceeds from the sale of this book benefit Shaping San Francisco a quarter-century old project dedicated to the public sharing of lost, forgotten, overlooked, and suppressed histories of San Francisco and the Bay Area. The project hosts a digital archive, and conducts public walking tours, bicycle tours, and even has a monthly Bay Cruise covering alternating routes of shoreline history with FishEmeryville.com. Our motto is that “history is a creative act in the present,” underscoring our commitment to the ongoing improvement and refinement of our knowledge and understandings of history, a process that is both contentious and necessary, as well as loads of fun!

**One-Shot Harry, “The latest mystery novel from Gary Phillips puts a spin on classic Golden Age noir” The Washington Post

RAND AT 70

By Gene Bruskin