Building Trades Leadership Undercuts Activists

By Len Shindel

“[Mr. President] Your address on Friday [Inauguration Day] was a great middle class address. It hit home for the working class people who have been hurting. You said it. People here in Washington have [unintelligible]. The working class people had to hear something like that. At that venue—being up there at your inauguration and laying it down—that was a great moment for working men and women in the United States.”

–Doug McCarron, International President, Union of Carpenters and Joiners of America

Jan. 25 had to be the best day yet for Kellyanne Conway and Sean Spicer. Surrounded by some key leaders of North America’s Building Trades Unions (NABTU), their boss was relaxed and smooth. In a silken tone, Trump thanked the Sheet Metal Workers for work they did on his hotel down the street (even as an electrical contractor was suing his company for allegedly getting stiffed on the job). Union leaders clapped loudly as Trump announced he was trashing the Trans-Pacific Partnership.

Trump told the leaders their members would soon be building new Ford plants and pharmaceutical manufacturing facilities for companies like Johnson and Johnson and they would be needed to complete a load of new projects as he terminates “disastrous” trade policies that had sent jobs out of the country. The regularly combative president even cut his predecessor some slack, saying bad trade policies preceded President Obama.

According to some blogs, Sean McGarvey, president of the NABTU, asked if the new administration would continue wage protections of construction workers who work on federal projects, provisions of the Davis-Bacon Act. Nonunion contractors had sent a letter to President Trump on Jan. 10 asking him to set the law aside. Trump said he “knew a lot” about Davis-Bacon. But he made no commitment to continue to protect construction workers wages from a race to the bottom.

As participants got up to leave the room, Doug McCarron, president of the Carpenters, said he had one more message for the president. Trump said, “I love Doug.” The president called everyone back in the room, asked a member of the press covering the event to join them and handed the floor to McCarron who gushed about Trump’s inaugural address, calling it a “great moment for working men and women in the United States.” McCarron looked pleased. The meeting was over.

Conway and Spicer, sitting directly behind the president, beamed like newlyweds on a honeymoon who just rolled out of the sack to find they had hit the lottery. In short order, a Fox News anchor asked a colleague: “Did anyone ever think for a minute that a Republican president would be inviting unions into the White House on his second official day of business?”

For Sean McGarvey, visiting the White House was like a kid’s first hour at Disney World. “The respect that the President of the United States just showed us… was nothing short of incredible,” he told the media. “He took the time to take everyone into the Oval Office and show them the seat of power in the world.”

Then McGarvey went further than McCarron in giving Trump his imprimatur. A press release from NABTU stated, “In politics, there are people of words, and people of deeds. North America’s Building Trades Unions are grateful that President Trump is a man who puts actions behind his words.”

On the blogosphere, NABTU leaders were immediately criticized for praising Trump. Erik Loomis, a blogger on “Lawyers, Guns and Money,” posted a story, “Building Trades Allow Themselves to be Played Like Fools,” contending that the leaders not only failed to secure any concrete guarantees on Davis-Bacon, but—in their effusive praise of Trump—further isolated themselves from political progressives. Loomis outlined the “deeply cultural” gulf between a large swath of building trades’ members and members of the wider progressive movement on issues from immigration to the environment.

“The problem,” says Loomis, is that “McGarvey, Terry O’Sullivan (president of the Laborers) and some of these other union leaders aren’t trying to educate their members on these issues.”

Hamilton Nolan, a blogger on The Concourse, posted a story, “Unions Don’t Do This” about the White House Meeting. Nolan listed topics Trump chose not discuss with the leaders: “His avowedly anti-union Labor Secretary nominee; his stated support for ‘right to work’ laws that could decimate union membership in America; his tax plan that will primarily benefit the very rich and exacerbate economic inequality; his statement that American wages are ‘too high,’ or the actual union busting campaign that his company ran against its workers in Las Vegas.”

“Don’t credit the guy who reacted to the jamming without giving a shout-out to the jammers.”

Now, I don’t pretend for one minute any labor leader’s job is easy after the defection of so many union members to a Republican Party that has never buried its animosity toward unions.

Trump brilliantly exploited the Democratic Party’s support for neoliberal trade policies, NAFTA and the TPP and drove the stake in deep. And, since the election, Trump has even hired guys like Robert Lighthizer, who had previously worked closely with AFL-CIO economists intent on strengthening the Obama administration’s trade negotiations.

It would make a big mistake for any labor leaders who oppose the Republican’s anti-worker agenda to take pot shots at Trump’s trade agenda as Les Leopold states so well in his article, “If Progressives Want to Defeat Trump They Must Win Back Workers.”

But McGarvey’s and McCarron’s fawning over Donald Trump’s attention to trade and infrastructure mimics the Democratic Party’s failings on those issues—the illusion that by treating your adversaries well, you can bend them to your agenda. It can get ridiculous.

Members of the Laborers International Union of North America (LIUNA), have said that International President Terry O’Sullivan, who was also in the White House meeting, was very worried about LIUNA members who participated in the “Women’s March on Washington” were wearing their bright orange union T-shirts. Better, he thought, for them to bury their union identity.

And why the hell would union leaders praise Trump without simultaneously crediting the years of struggle by the nation’s best trade union activists, lawyers and economists to turn around trade policy? Trump and Pence, for instance, scored a load of points cutting a deal to keep some jobs that were destined for outsourcing at Carrier in Indiana. What was soon forgotten was the excellent media work done by the United Steelworkers (USW) and the YouTube video of union members shouting down the executive who told them their jobs were going to Mexico. Don’t credit the guy who reacted to the jamming without giving a shout-out to the jammers.

My original anger over this stuff has turned to sadness. Thirteen years ago, after 30 years as USW activist and local union leader, I went to work for the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW) hired as a communications specialist in the union’s Washington, D.C. headquarters.

I marveled at the strong identification members in the union’s construction branch had with their trade and their union. But I also learned that this pride sometimes came with the evil twin of nepotism and exclusivity. So I gained even greater respect for the inspirational and courageous IBEW activists and leaders who were working to broaden the union’s reach and diversify its base.

I was honored to write stories about former gang members in South-Central L.A. recruited by the building trades, transforming their lives and contributing to their communities. I took pride in helping promote the work of apprenticeship instructors who were incorporating the principles of solidarity and fairness into their curriculums. And, while I had deep differences with the IBEW on fossil fuel policy, I took heart in the work of locals unions that promoted jobs and training in renewable energy and working with, not against, environmental advocates.

These forward-looking IBEW activists are not alone. They exist within O’Sullivan’s LIUNA and McCarron’s Carpenters. Members of both unions have worked to reach out to and recruit tomorrow’s workforce and mentor new leaders, including large numbers of Latino workers. In fact, McCarron built his reputation supporting Latino dry-wall installers in his native California, bringing them into the Carpenters. There is so much fertile ground for growing the building trades’ density in previously ignored or excluded sectors.

When McGarvey, claiming to speak for all the trades, kowtows to a president who launched his political career attacking the legitimacy of the nation’s first black president and stereotyping Hispanics as “rapists and murderers,” he undermines the work and the morale of dedicated activists and potential members, the future of the U.S. labor movement.

I would hope a critical re-assessment of NABTU’s messaging and strategy toward the new administration might turn around these problems. But I know that will take a struggle and much courage on the part of other building trade leaders and activists.

Sometimes internal polarization is necessary for a movement to win. McGarvey and McCarron have compelled this reality.

MLK’s Advice on Strike Strategy Still Relevant Today*

By Rand Wilson

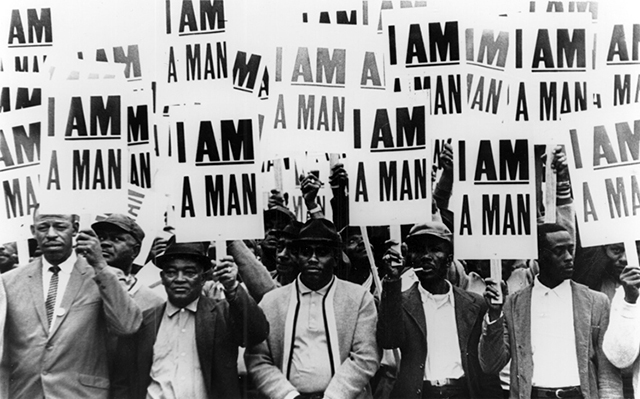

Striking members of Memphis Local 1733 hold signs whose slogan symbolized the sanitation workers’ 1968 campaign. Credit: Copley, Richard L., “I AM a Man,” I Am A Man, accessed January 18, 2017.

After 1965, Martin Luther King Jr’s thinking about poverty evolved from racial equality to more of a class perspective. He proposed a Poor People’s Campaign to challenge the government to end poverty and a broad coalition to support it. But building a coalition to back his program for economic justice proved more difficult than he imagined. It made his funders and even his closest advisors nervous. A proposed national march on Washington had to be postponed and King was growing frustrated.

Sanitation workers in Memphis, TN had been trying to get organized and win recognition from the city for years without success. After two workers were accidently crushed to death in one of the garbage trucks, a majority of the workers decided to strike on February 12, 1968 for union recognition and a contract.[1]

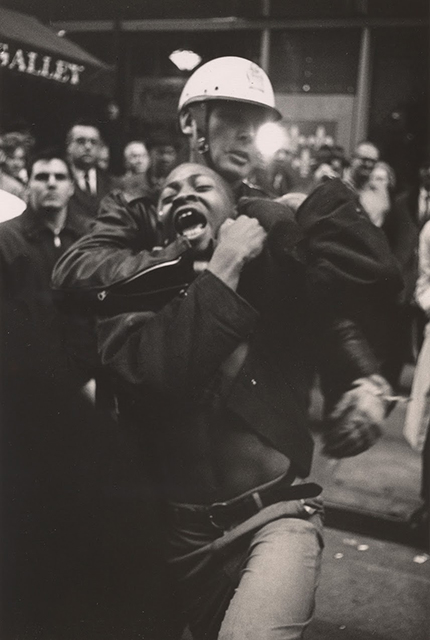

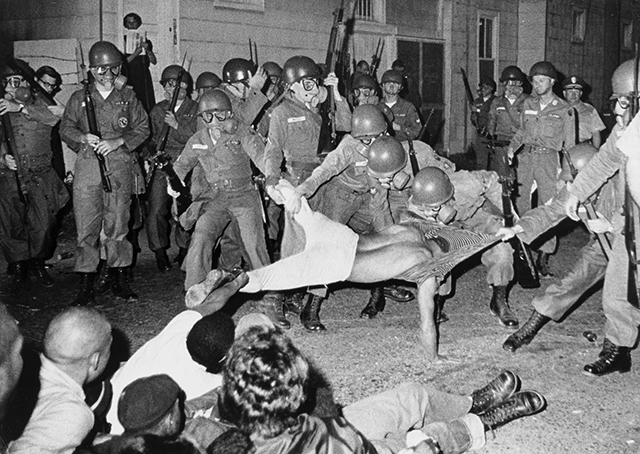

The strike had been going on for months with growing frustration. Incidents of violence were increasing, mostly provoked by the racist and brutal Memphis police.

King recognized that the strike provided with an opportunity to demonstrate how the civil rights and economic justice movements could come together at the local level. He proposed bringing the campaign to Memphis.

Expand the Strike

King first went to meet with the strikers in Memphis on March 18. He spoke to 1,500 workers and supporters. King was well received and the crowd’s mood was militant and eager for action.

King said, “If America doesn’t use her vast resource of wealth to end poverty and make it possible for all of God’s children to have the basic necessities of life, she too is going to hell.” And he went on to describe how their strike was part of new direction for the civil rights movement:

“Now our struggle is for genuine equality, which means economic equality. It isn’t enough to integrate lunch counters. What does it profit a man to be able to eat at an integrated lunch counter if he doesn’t earn enough to buy a hamburger and a cup of coffee?”

As the crowd cheered, King saw an opportunity to grow the movement by expanding the strike. He called for a general strike in the city of Memphis! Plans were made and a strike date was set. The tactical escalation was highly controversial.

Unfortunately, due to a freak snowstorm, the strike was called off. Amid growing threats to his life, King hurriedly left Memphis. However, he was not to be deterred and vowed to return.

Boycotts and economic action

King returned to Memphis on April 3, 1968 to support the strike again. At a rally with strikers and area clergy he gave his, “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech — one of his most famous and fatefully his last.[2] This is the speech where King predicted his own assassination.[3]

However, the main subject of the speech was winning the sanitation strike. King advised they should use the power of the boycott to, “Always anchor our external direct action with the power of economic withdrawal.”

“We don’t have to argue with anybody. We don’t have to curse and go around acting bad with our words. We don’t need any bricks and bottles, we don’t need any Molotov cocktails, we just need to go around to these stores, and to these massive industries in our country, and say, “God sent us by here, to say to you that you’re not treating his children right. And we’ve come by here to ask you to make the first item on your agenda fair treatment, where God’s children are concerned. Now, if you are not prepared to do that, we do have an agenda that we must follow. And our agenda calls for withdrawing economic support from you.”

Making our pain, their pain

When workers go on strike, it almost immediately involves personal sacrifice. As the weeks and months go by, that sacrifice becomes real pain inflicted on the strikers and their families. King’s quote from his last speech is particularly relevant to most every strike situation:

“Up to now, only the garbage men have been feeling pain; now we must redistribute the pain. We are choosing these companies because they haven’t been fair in their hiring policies; and we are choosing them because they can begin the process of saying, they are going to support the needs and the rights of these men who are on strike. And then they can move on downtown and tell Mayor Loeb to do what is right.”

One day longer

King knew the importance of winning, of keeping spirits up and sticking together. He said, “We’ve got to give ourselves to this struggle until the end. Nothing would be more tragic than to stop at this point, in Memphis. We’ve got to see it through.”

Solidarity forever

To the clergy and other civil rights supporters, King delivered a powerful message of solidarity: “And when we have our march, you need to be there. Be concerned about your brother. You may not be on strike. But either we go up together, or we go down together.”

Near the end of the speech, King used the “Good Samaritan” parable from the bible to implore everyone to make even greater sacrifices to help the workers win. He concluded with words that have an uncanny relevance to our time:

“Let us develop a kind of dangerous unselfishness… Let us rise up tonight with a greater readiness. Let us stand with a greater determination. And let us move on in these powerful days, these days of challenge to make America what it ought to be. We have an opportunity to make America a better nation.”

King’s strategic advice to the striking Memphis sanitation workers is still useful for workers seeking to improve their lives with direct action today. Once on strike, expand the struggle beyond the immediate company to its corporate allies and suppliers; use boycotts and economic action to involve supporters; transform the pain inflicted on strikers, to pain inflicted on executives, board members and investors; be prepared to stay in the struggle one day longer with “dangerous unselfishness”; and perhaps most importantly, winning requires placing the struggle in a larger context that challenges elected officials and government at every level to make America a better nation!

*Adapted from remarks by Rand Wilson on January 16, 2017 at the Capital District Area Labor Federation’s 20th Annual MLK Labor Celebration in Albany, NY. In nearby Waterford, NY there are 700 workers on strike at Momentive Performance Materials and in Green Island, NY, dozens of workers have been locked out at a Honeywell aerospace plant for more than nine months.

Footnotes:

[1] Memphis sanitation strike

[2] I’ve Been to the Mountaintop

[3] “Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will. And He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over. And I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land!”

Analysis of the NO vote in Italy

By Nicola Benvenuti

The Stansbury Forum has received a lot of interest in the article we ran by Leopoldo Tartaglia from the CGIL on the Italian NO vote on December 4. Many news commentators have characterized the NO vote as akin to the Trump victory in the US and the Brexitt vote in England in June of 2016. Our readers have asked for the specifics of the actual proposed constitutional amendments and the demographic character of the NO vote. Nicola Benvenuti and Leopoldo have graciously agreed to help clarify these issues for our American readers. Nicola and Leopoldo have analyses that differ on YES or NO but agree on some of the underlying social and political demographics.

We are proud to continue to present political perspectives from Italia Bella and we will be covering additional Italian national referendums to be held in the spring on labor reform.

The December 4 referendum on constitutional reform in Italy was of great importance. There was a high turnout, more in keeping with candidate elections than referendums that historically had drawn fewer voters. Commentators have attributed this turnout to the reckless gamble of Prime Minister Matteo Renzi who made the referendum a plebiscite on himself and his government. On the one hand he was counting on the fact that the reform reduced the cost of government by eliminating the salaries of the new Federal senators, and by changing the powers of the regions and reducing the salaries of elected regional councils. In truth these savings were for “populist appeal” and would have had little impact on the high cost of Italian government. On the other hand the referendum was about the unanimously recognized need to streamline political processes, in particular by reforming perfect bicameralism. At present the House and Senate have the same legislative powers – which means double the time for the approval of laws. The referendum also sought a revision of the system of checks and institutional counterweights, created in 1947 to ensure the coexistence of radically different positions such as those that emerged from the East-West conflict. These “safeguards” have now become opportunities for blackmail and the backroom deals typical of Italian politics.

“Forces that are totally antagonistic”

However a disaggregated analysis of the vote shows the social character of the result: a high percentage of young people and unemployed voted NO, with the highest NO votes in the South and on the islands (Sicily and Sardegna): a sign that the promises of Renzi to rejuvenate – or “scrap” – the ruling groups so as to make way for a new generation, new ways of thinking and new solutions to the problems of the country, had no effect on youth unemployment (in July 2016, + 2 points, reaching 39.2%), nor have his policies curbed the fall of the middle class into poverty (A decline of almost 8% of the population, with an increase of 141% in ten years). The referendum vote very dramatically highlights the separation between politics and the actual social situation.

From a political point of view the situation created by the referendum vote is as follows:

1. “YES” was supported by only the Partito Democratico (PD) despite the fact that the constitutional law (voted in Parliament) had also been supported by the opposition center-right (but not Five Stars), while “NO” was supported by: a) Five Stars, b) the right c) the left inside and outside the PD. Forces that are totally antagonistic. Hence the assessment that, politically, “NO” was not an alternative project but only a vote against Renzi and the Democratic Party government, without much real consideration of the merits of the constitutional reform. Renzi noted that the vote had meaning beyond the reform and resigned to leave the field to a very similar government to achieve electoral reform with votes in the Senate that has maintained its previous power because of the NO vote in the referendum. (In 2015 the Parliament had passed a law only in the Chamber of Deputies, anticipating the modification of the Senate on December 4).

2. This begins a period of instability and political uncertainty, something that the country does not really need given the difficult international and economic choices that lie ahead. Italy needs stability and a sense of responsibility, not political infighting. Germany achieved this stability with the Grand Coalition policy. In Italy there was a unity of purpose because of the danger of financial failure and international pressure, but only with a “technical” government, the government of Monti ( November 16, 2011 – April 28, 2013) supported by the whole parliament. The Monti government passed emergency measures, but also passed political reforms, like the one that provides for the extension of the age for retirement, that no party had the courage to make alone. The Renzi program, from the constitutional reform project and the movement of the party towards the center in an attempt to strike a deal with Berlusconi, was precisely to establish the political conditions for incisive action in this dramatic emergency situation.

3. The vote has sanctioned a fracture in the left and in the PD based in part on internal opposition and an attempt to regain control of the party more than on the merits of the legislative measures put in play. Renzi, who is also the Secretary of the PD has turned a deaf ear to corrections required by the internal opposition that voted against the reform. Even if this rift is overcome a restructuring of the left is inevitable. The former Mayor of Milan Pisapia of Sinistra Ecologia Liberta (SEL), a political organization to the left of the PD, formed an alliance between the radical left, PD and personalities of the center, and managed to maintain a center left government in that city while the PD lost the Mayor’s races in both Turin and Rome. Pisapia has proposed an independent aggregation of left forces with an explicit program of conditional support for the policies of the Democratic Party from the outside. But it is still too early to say what will happen.

Beyond political alchemy, the Italian situation is such that the public debt does not offer great margins for economic or social maneuvers, and the danger once again is that the radical differences and fracturing of political forces pushes everyone to avoid the grave and unpopular responsibilities necessary to escape the crisis.

Please scoll down to read the second article on the Italian referendum by Lepoldo Tartaglia

The Italian referendum No vote: contents and context

By Lepoldo Tartaglia

“Everyone can agree that a Constitution is the fundamental pact building a society and a State and that any change has to be evaluated carefully… That was not the case”

The Renzi government’s crisis was fixed in about ten days. A new government, led by Paolo Gentiloni, former Foreign Minister, obtained a confidence vote, from the Chamber of Deputies (the lower chamber), and the Senate (the upper chamber). Most of the ministers have been confirmed; the parliamentarian majority is the same; “continuity” is the word used most often in the policy speech of the new prime minister. None of the financial disasters predicted before the vote in the case of a No victory have happened; actually, the Milan stock exchange did better than before.

Nevertheless, the political earthquake was important and fresh elections are around the corner.

Two important events are coming. On January 11th the Constitutional Court will decide whether the three referendums that the CGIL has proposed that would delete the worst rules of the so called “Jobs Act” and previous labor market laws, can go forward. On January 24th, the same Court will decide on the electoral law pushed for by the Renzi government, in an attempt to resolve the unconstitutionality of the previous electoral law. Many predict a new negative decision, due to the fact that the so called “Italicum” (the Renzi made law) replicates the problem of too many parliamentary seats being given to the party with the largest percentage of the vote, and the fact that voters under Italicum have little chance of voting for the candidate of their choice, rather than a person decided on by the parties’ leadership.

In order to go to fresh elections, the Parliament has to approve a new law, based on the upcoming Constitutional Court decision, and establish an electoral system for both chambers, given that the Italicum assumed that only the Chamber of Deputies was elective – which would have been the case in the event of a YES victory in the December 4th referendum.

What was really at stake in the constitutional referendum? Why did a significant part of the left and the center left (including the minority of the Democratic Party, the Renzi party) and the most important leftist social mass organizations stand on the NO front? What are the linkages between the vote and the social situation of the country?

1) The reform’s contents

While the vote was charged by many political meanings (see below), there was widespread opposition to the reform’s contents. This begins with the method of its approval, which also explains why we went to the referendum.

Everyone can agree that a Constitution is the fundamental pact building a society and a State and that any change has to be evaluated carefully by searching for a large consensus in the parliament and in the country. That was not the case: the reform law had been approved only by the parliament’s majority (very narrow in the Senate), and with recourse to a confidence vote, reducing the scope of the debate also inside the majority itself.

The national referendum was not a nice democratic concession by the Renzi government: it was compulsory, according to the Constitution, because the reform didn’t reach the required two third parliamentary vote to pass directly without the need of electoral validation.

“… this would lead to dysfunction in the regulation and management of essential public services …”

Renzi propagated a myth that the “old” Constitution had never been modified in 70 years. In fact, the Italian Constitution was promulgated in 1948 and has been changed many times. The last change, in 2012 happened with a practically unanimous parliamentary vote, under the Monti government and it changed Article 81, introducing the obligation to balance the State’s annual budget. In 2001 and 2006 people were called to vote on constitutional referendums, again because the majority coalition changed the Constitution without the necessary parliamentarian approval. In 2001, the reform was backed by the center left, and the majority of voters confirmed it (with a very low turnout, about 30%). In 2006, the popular vote defeated the reform that had been approved in Parliament only by the Berlusconi majority (turnout 52%).

The Renzi reform was the largest one, so far, regarding 47 articles of the second part of the Constitution (institutional organization of the State). The core of the reform was to fix the present “perfectly bicameral” system, where the parliament upper and lower houses have equal legislative powers. Renzi wanted to replace the directly elected Senate of 315 seats, with a smaller chamber of 100 members, chosen by the Regional Councils from among their members.

Along with many other constitutional changes, the second most important “reform” regarded the relations between the central State and the Regions; taking away much of the authority of local governments that the 2001 center left reform had given them. And in the opinion of many constitutional scholars (including many former members and presidents of the Constitutional Court – most of whom stood on the NO front), this would lead to dysfunction in the regulation and management of essential public services delegated to the Region, and to a huge increase in authority disputes between the Regions and the Italian State.

“ … the majority of the population, particularly young people, workers and those living in southern Italy, has not seen any positive change …”

Also the supposed elimination of “perfect bicameralism” was unclear, due to the confusing nature of the proposed new regulation and the capacity of the Senate to call for the review of any proposed law it wanted to examine. The only clear new rule on the relation between the two chambers was that a confidence vote in the government was given by the reform solely to the Chamber of Deputies – leaving Italy with a parliamentary system, not a presidential one.

There is an important institutional question that also fueled the NO position, even if it was not directly included in the reform: the linkage between the new role of the Chamber of Deputies and the new electoral law. The electoral law called “Italicum” states that the party that wins the election (with 40% of the vote in the first ballot; or wins the second ballot between the first two parties, regardless the percentage of vote in the first run) gains the 54% of the seats (332 out of 615). So, due to the Italian institutional system, as a result of the reform, that party (which might be very small in terms of real representation), would have been able not only to elect the prime minister and the government, but the President of the Republic and the Constitutional Judges (elected by members of both the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate).

So, the constitutional reform was seen by the leftist opposition (and not only) as a big concentration of powers: from Regions and local authorities to the central State; from Parliament to Government; from Government to the party winner of the elections (in a context of reduced representation, given the very high majority premium guaranteed by the new electoral law).

In the opinion of those on the left who opposed the reform, there was a clear continuity with the last institutional and electoral reforms in Italy, that were mainly pushed by the center-right parties and international financial powers, and aimed to concentrate political power, reduce the representativeness of the parliament and reduce the space of the opposition in order to sterilize the voice of the working class. In fact, in the last 25 years, several changes to the electoral laws and a push toward a “de facto” presidential system, denied by the Constitution, contributed to the restriction of the people’s political participation and, particularly, to the progressive exclusion of the radical left from the parliament (obviously, with a huge assist from the litigious leftist organizations themselves).

2) The vote’s political meanings

In a normal scenario, a constitutional reform is an issue largely in the hands of Parliament, with the Government less involved, or not involved at all. However, in this case, it was the Renzi Government playing the game, with two clear objectives: build up a more centralized institutional system and give more power to the government; realize a resounding victory in the referendum as electoral validation for a government and a leadership never chosen through a popular election. As you might remember, Renzi was not a parliamentarian and he became prime minister after his victory in the internal primary vote for the Democratic Party’s leadership and he pushed his own party parliamentarians to withdraw the confidence in then Prime Minister Enrico Letta, member of his same Partito Democratico (PD).

However, despite the clear signals of popular discontent – particularly in the June 2016 municipal elections, when the PD lost 19 out of 20 second ballots – Renzi launched the referendum campaign as a vote on him and his government, claiming that his government had obtained amazing results on the economy, employment, political renewal and so on.

Yes, the effect was truly amazing: he was able to coalesce not only previous voters of the opposition parties – those of the divided centre right, the small far left and, over all, the Five Star Movement, which actually was the largest vote getter in the 2013 political elections – but also a large number of people disaffected from politics, who in recent years had deserted the polling stations.

The popular rejection of the government and its policies and the opposition to the reform’s contents added up reaching together more than 19 million votes.

3) The demography of the vote: a class “revolt”?

Is there a social configuration of the vote? Yes, off course.

Firstly, it’s worth noting that, despite the Renzi propaganda on the “new”, on the YES vote “for the future” against the NO as the return to the past, the NO vote was particularly large among the young generations. While the YES prevailed only among the over 65 years old (56% against 44%), the largest NO vote was among the 25 – 34 years old voters (72% against 28%).

The YES vote won with a narrow margin only in three regions out of twenty (Trentino Alto Adige 53.9%; Tuscany 52.5%; Emilia Romagna 50.4%) which are regions traditionally on the centre left and PD side, but also among the better off regions in Italy. On the contrary, the largest NO results came from the southern Italy regions (Sardinia 72.2%, Sicily 71.6%, Campania 68.5%), notoriously the poorest part of the country, affected by a huge level of unemployment, and a high gap in terms of incomes and living conditions in comparison with the center and the north of Italy.

According to a survey of the Istituto Cattaneo, a think tank based in Bologna, specializing in opinion polls and research on electoral behavior, there was an apparent link between the vote and income. Considering that Bologna itself was one of the few towns were the YES vote prevailed, the difference in the NO vote there ranged from 51.3% for people earning less than 18,000 euros yearly to 40.1% for people earning more than 25,000 euros yearly.

In many districts, particularly in the largest towns and in regions where there was strong support for the rightist parties there was an apparent link between the NO vote and the presence of a relatively large number of migrants, meaning also a rejection of government policy perceived as too open to immigration.

So, what all the commentators argue – and, at the end, Renzi himself admitted before the steering committee of his party, is that the vote was largely a vote against the social and economic policies carried out by his government. Despite the optimism enthusiastically spread by Renzi, Italy is still in the midst of the crisis, with a very low rate of growth, large unemployment, particularly among the youth, a rising rate of poverty and inequality. Nor was Renzi’s attempt to distinguish himself from the unpopular austerity policies led by the European Commission seen as authentic.

The major social reforms the government claimed – particularly the so called “Jobs Act” (Renzi titled the law in the English language) – resulted, as unions and Cgil in particular said from the beginning, in making work more precarious, without any visible growth in jobs.

In general, in a stagnant economic landscape, the majority of the population, particularly young people, workers and those living in southern Italy, has not seen any positive change in its situation and doesn’t have any confidence in the political establishment, although the rulers attempted to disguise themselves as anti-casta (anti establishment).

The Sanders’ Campaign: A Local Perspective

By Peter Haberfeld

The Stansbury Forum is proud to publish organizer and labor attorney Peter Haberfeld’s diagnostic of the Bernie Sander’s ground game in Berkeley/Oakland in the run-up to the California primary in June of 2016. This is a longer piece than The Stansbury Forum normally publishes, but we make an exception here because of the rich detail of the challenges of building grass roots political power that Haberfeld presents. Haberfeld contrasts the “organizing” work that he and his comrades attempted to do with the “mobilizing” approach of many in the national Sanders campaign, and their over reliance on social media and barnstorming meetings. It is useful however to remember that the work that Haberfeld describes is all in the context of a “movement moment” that electrified the country, particularly the millennials. Readers who are interested in contrasting styles of thinking about base building and power will enjoy, and learn much from Mark and Paul Engler’s book, “This is an Uprising” published by Nation Books, and soon to be reviewed on The Forum. Many thanks to Peter Haberfeld for being willing to publish such a compelling organizer’s tale. We hope that discussion and comments will flow. The Editors

“The ‘warmer’ the contact, the stronger the relationship.”

Introduction:

Let’s present the question simply as we confront a situation of growing urgency. How can the 99% defend themselves against the power of the 1% that have purchased the political system, continue to enrich themselves at our expense, and can be expected to stop at nothing as they seek to repress those who challenge their domination? How do we organize ourselves to alter that imbalance of power?

Together, we have to develop many different organizing strategies. The assumption here is that some of us have develop ways to win election campaigns at the local, state and national level. The following comments describe the “nuts and bolts” of election organizing: building a volunteer base, phone banks, house meetings, one-on-ones, canvassing door-to-door, voter registration, social media, forming alliances, the difference between mobilizing and organizing, and some ideas about how to continue fighting for the agenda past the election.

These are some post-election reflections from Berkeley and Oakland about trying to win the California Democratic Party primary for Bernie Sanders, a small but important part of his national campaign. The comments also point out some shortcomings of Bernie’s campaign in our area.

We can learn from the “elders”:

We did not invent these techniques of welding together a volunteer force capable of winning elections. Collectively, we learned, directly and indirectly, from the disciples of legendary organizer Fred Ross Sr.—whose story is well-told by Gabriel Thompson in the biography America’s Social Arsonist: Fred Ross and Grassroots Community Organizing in the Twentieth Century. Also deserving mention are: Cesar Chavez, Marshall Ganz, Fred Ross Jr., Larry Tramutola, Paul Milne, Glenn Schneider.

Creating a volunteer base:

My partner Tory Griffith, Carla Woodworth and I combined forces, beginning in October 2015, as we witnessed Bernie’s campaign pick up steam across the country. We prepared for the national campaign’s arrival and its hoped-for-success in the Berkeley-Oakland area.

Our first task was to begin creating the volunteer base. We printed a volunteer card, set a goal of 1000 volunteers by the end of December, and began to attend events to talk with people one-to-one about Bernie’s campaign. The volunteer card asked for contact information and listed campaign tasks: hold house meeting, talk to voters by telephone and house to house, staff office, distribute signs….

We asked questions. Had the person heard about his campaign? What did they think about it? We asked whether we could keep in touch with them and, together, find something they would like to do at a time that was convenient for them.

During one week-end, we went to a street fair, an event on Shattuck Avenue, one of Berkeley’s main arteries. We were surprised, and excited, by the cross section of people who were politically well-informed, and how many were ready to talk and willing to fill out the volunteer card. Some came from Walnut Creek, a mostly white, middle-class suburb about 20 minutes east from Oakland/Berkeley.

Listening, we quickly understood that there is widespread dissatisfaction. People want change, big change. Bernie’s message had hit a responsive chord.

Combining with young allies:

A few days later, we went to a meeting of students on the UC campus and connected with some “tech-savy”, motivated people who had visions of organizing the campus. They said that they wanted to run phone banks. (It is more productive and more social to call for three hours with other people than it is amid numerous distractions at home.) I told them that was our next step as well. They filled out cards. We agreed to collaborate.

Phone banks:

Carla found an art gallery on University Avenue, Berkeley’s other main street. She talked the owner into letting us use it for free. It was a good space for a phone bank.

The UC students helped connect with the national Sanders campaign. It asked us to call voters in States that were about to hold their primary. Our volunteers were able to log-on and download phone numbers, instructions and scripts. We scheduled them to call in three-hour shifts and asked that they bring a cell phone, a lap top and a charger.

We began recruiting volunteers to attend the phone bank on Saturdays from 10 to 3, a time period that enabled them to reach the voters whose names and numbers were supplied by the national campaign. As the California primary approached, we called California voters.

Building an organization on the foundation of individual relationships:

We did everything possible to begin developing a relationship with each volunteer. Tory greeted people, had them sign in, gave them a name tag, set them up with a student assistant if they needed help, and pointed out the food and the location of the rest rooms. She captured them as they completed their shift to ask about their experience on the telephone, thank them, and sign them up for the following week on butcher paper at the exit. We promised to contact them at their phone number and email address a day before their next scheduled participation on the phone bank to remind them of their commitment. Tory quickly memorized everyone’s name, and treated each like a comrade.

During the phone bank session, we called people who had signed up the previous week but had not showed up. We had two purposes: reschedule “no-shows” and hold them accountable. We let them know that we noticed that they missed their shift, assured them that we knew they were committed to Bernie’s victory, and pointed out that they had a continuing opportunity to succeed. We signed them up for another day.

Our attendance grew. Several times we had over 95 callers on a Saturday. On one day we had 105. Together, we called thousands of voters in other States and enjoyed believing that we helped produce some wins.

In the words of Fred Ross Sr.: “Short cuts are always detours.”

House meetings, a building block:

Tory and I began doing house meetings. Aggie Rose Chavez, David Weintraub and Stu Flashman, three experienced organizers, helped by leading those we were unable to cover. Building a grassroots movement with house meetings is a technique that was created by Fred Ross Sr. and Cesar Chavez as they organized the farm workers union. It has been used since in many organizing drives throughout the US. Bernie’s national campaign did not do house meetings.

We began by meeting one-to-one with people who were interested in inviting relatives, friends, acquaintances, neighbors to a Bernie meeting at their home. We did not soft-sell the task. Instead, we were very clear with prospective hosts that to produce a decent house meeting, attended by12 to 20 guests, you have to make 60 to 80 calls, get firm commitments instead of “maybe”, and do a round of reminder calls a day before the event. (Our experience demonstrates that failure to do reminder calls results in a 30% loss of attendance.) Emails and phone messages help focus busy people on an event, but do not substitute for a person-to-person conversation that yields a clear commitment. In the words of Fred Ross Sr.: “Short cuts are always detours.”

The prospective hosts agreed that we check with them several times before the meeting about their progress getting firm commitments from potential guests. Our support would also include directing people to their meeting. But we would call off their meeting if they were unable to get at least ten. A number of potential hosts decided not to hold a house meeting. We cancelled some house meetings in order to avoid failures.

At the house meeting, we began with a welcome from the host who also explained what it was about Bernie and his campaign that motivated them to do the work of convening a house meeting. Then, we asked each person to introduce themselves and explain their interest in Bernie’s campaign. People were no longer anonymous. They could teach and learn from each other. Listeners acquired a sense about what they had in common with other guests and heard several perspectives about the importance of the campaign. Guests began to be aware that they were not alone. Some began to sense the possibility of collective power, an important part of creating organization.

We began the meeting by explaining the agenda and promising that the meeting would be completed in less than one and a half hours. That promise justified a rigorous adherence to the agenda and the time allotted to each item.

We showed some Bernie videos we got off the web, told our respective stories (some biography and why the campaign was personally important to us), held a brief discussion, explained the campaign, filled out volunteer cards, and made a pitch for money. We signed guests up to participate at the phone bank. Others volunteered to hold a house meeting. We raised about $10,000 that we sent to Bernie and cash that we used to pay for the food and drinks we made available to volunteers.

Our best organizers, as usual, turned out to be the people who held the most successful house meetings. We enlisted them to help us call the local campaign’s volunteer base to schedule volunteers for phone banking and the canvassing that took place in the neighborhoods contacting voters at their residence.

One-to-ones:

Our initial meeting with the prospective house meeting host resembled an additional technique that is used by organizers of grass roots movements. The organizer asks questions designed to get to know the person’s interests and values. What is it, in the individual’s view about their background and hopes that causes them to respond positively to Bernie’s campaign? The interchange encourages the person to think about, and act on, their aspirations for a better world, for themselves, their children, and their community. The one-to-one is a respectful and somewhat probing exchange that evolves into an invitation by the organizer to act with like-minded individuals.

Alliances:

A local Democratic Club served as the sponsor of the phone bank and fronted the money for signs, buttons and later lawn signs. Merely a few of its members showed up at the phone banks and held a house meeting. Some prefer the realm of ideas to building collective power, the labor intensive, person-to-person contact with voters.

A few people who show up at phone banks, canvassing, and house meetings prefer to talk, give advice about what else should be done, and speculate about the various candidates’ chances of winning. Try as you may, you can’t get them to commit to a specific task. Unless you are careful, they will waste the time you have to spend with active volunteers.

Why didn’t more people who had gone out of their way to sign-up on the national web site feel they had made a commitment and honor it by returning another volunteer’s phone call, signing up for a shift, and then showing up to do their part?

The new technology:

We discovered a treasure trove of potential volunteers. One of the UC students “accessed” the Sanders national web site and downloaded about one thousand of the 7000 names of people who had signed up from the Berkeley area to volunteer in Bernie’s campaign.

We made cards for the new people and began calling them. (Later we developed a data base for all volunteers and listed the results of our various contacts.) It was difficult to reach them. Despite our pleasant, sensitive, caring messages, hardly anyone called back. We found some good people, but very few out of the number we called. It was like “cold calling,” a term used by telemarketers.

Why didn’t more people who had gone out of their way to sign-up on the national web site feel they had made a commitment and honor it by returning another volunteer’s phone call, signing up for a shift, and then showing up to do their part? One reason was that it is always best to find something for the new volunteer to do immediately. Unfortunately, the new list was “cold”: they had signed up weeks before and had not received a call or contact.

An additional reason has to do in some way with the limitation of social media. Those communications, alone, do not produce the kind of personal relationships which in turn can produce mutual commitments. I recall Cesar Chavez teaching his organizers about how to deliver the union’s newspaper El Macriado: “Don’t leave a stack of them on the counter in the union office. Don’t leave them where people live. Hand them to people individually and have a face to face conversation. The ‘warmer’ the contact, the stronger the relationship.”

Neither signing up on a web site, nor communicating by email is warm enough. It does not create the powerful bond needed to weld together a community of mutually committed activists. In our local experience, the national campaign’s approach relied too much on social media and was weak on relationship building.

There may be an additional factor operating. Our society has become more and more atomistic. Fewer people live in areas they grew up in, with familial ties, as part of communities they depend on. The new technologies and the demands of a person’s job(s) isolate them further. Although there appears to be yearning for community, people are accountable at most to immediate family. They find it difficult to commit to others even for something they believe in. These obstacles may be overcome as worsening conditions give more and more people an urgent, personal stake in confronting what Bernie has aptly described as a rigged economic and political system.

The national campaign’s “barnstorm”:

One day, we learned that two volunteers from San Leandro would use our space in Berkeley to conduct a “barnstorm” on a Friday evening That is a Sanders campaign invention that puts out an invitation on social media, asks for confirmation and hopes for the best. We did not ask permission, but had eight of our people greeting guests at the door with pens and volunteer cards. We collected 383 cards.

“We lost an experienced organizer.”

The meeting had a good spirit but a totally chaotic way of recruiting people to work. Individuals were encouraged to stand up and invite people to their house, office, a local café, or wherever, to make calls, in other words to organize an impromptu phone bank. The do-your-own-thing approach did not urge the hosts to get the contact information from people who wanted to come, and there was no organized way to give reminder calls–a fatal flaw. Also, the national campaign encouraged people to log-in and begin making calls from their homes, but it had no way of knowing who was doing what. It had no on-going contact with those potentially active volunteers.

On the day following the “barn-storm”, we began using the completed cards to call people and urge them to come to our phone bank on Saturday. Later, after the national campaign people came to Oakland, they did another “barnstorm,” but they refused our offer to connect with people individually at the entrance, fill out cards, and get contact information. Instead, people stood in line to sign-in at a computer.

Carla considered the national organizers inexperienced and viewed their campaign structure as ill-conceived. She wanted a full time office for the Berkeley campaign and a precinct operation in which captains were recruited and trained to take responsibility for contacting voters in a particular geographical area. She finally quit over disagreements. We lost an experienced organizer.

Precinct captain structure:

We tried to negotiate with the staff an opportunity to put together a precinct captain structure. The Sanders people had claimed they were building an organization as opposed to merely mobilizing. We argued that without a structure in which people take ongoing responsibility for part of the campaign, in this case contacting a certain number of voters in the precinct to which they were assigned, preferably in their own neighborhood, the campaign was reduced to mobilizing volunteers each week from square one. The campaign seemed to agree with our request but did not want us to do anything different and made it all so complicated that it became impossible.

We went along with their structure. Our volunteers wanted to work with the campaign rather than quit.

Mobilizing for each week-end continued to be difficult and frustrating. We were not building an organization of shared responsibility and leadership.

To illustrate how this contrasts with a more effective organizing campaign, let me explain briefly how to set up a precinct captain model. The county registrar of voters has divided the electoral district into precincts, and produces lists of voters’ names, addresses, phone numbers, political party, and age, that can be obtained in hard copy or on the computer. The organizer approaches the most energetic and reliable volunteers and asks them to be responsible for contacting voters in a particular geographical area, the precinct, to identify Bernie supporters and later turn them out to vote. The captain is responsible for figuring out how to be most productive, namely making the contact when the voter is most likely to be home.

The organizer and precinct captain set a realistic goal for the precinct and schedule phone conversations to take place during the week when the captain will report numbers of voters contacted and responses. The organizer explains that s/he is there to help the captain, to suggest ways to overcome any difficulties and to send other volunteers to help form a team under the direction of the captain. A strong, on-going connection is forged between the organizer and her/his captains. The campaign is clear what it needs and encourages the captain to use her/his creativity how to accomplish the goal.

The Sanders campaign did not venture into our suggested realm of organizing. It even refused to take its list of supposedly 7000 people from the Berkeley-Oakland area who had signed up on the national web site and match their addresses with precinct numbers. We had explained that such a list would enable us to interest potential captains in assuming responsibility for working their particular neighborhood. Staff members told us that the national campaign wanted to keep that list separate for fund-raising.

The staff person assigned to our office had launched a Bernie student group at UC Davis and worked in another State’s primary before California’s election. She had good computer skills and worked hard to implement her campaign’s program. She was encouraged about our capacity to turn out more people for phone banking and precinct walking than “any other office in the State,” a fact that, if true, reflected badly on what was going on elsewhere.

There was no effort to figure out whether to attribute our “success” to the relationships we built or to Berkeley’s political history. The national campaign’s East Bay “headquarters”, located in upscale Rockridge, had the reputation as an unfriendly place run by an in-group of staff members. Some of that office’s refugees preferred to work out of our office in Berkeley.

Voter registration:

Immediately, after their arrival in the East Bay, the national staff asked us to register voters at supermarkets and other locations of high volume pedestrian traffic. We approached passers-by and offered to register those who had never voted. We offered to re-register those who recently had moved or changed their name, or who were registered in another Party (primarily Peace and Freedom and Green Party members) and would have to re-register as Democrats to vote for Bernie in the primary.

Although this kind of voter registration gave the campaign visibility, it did not focus on the campaign’s main objective. We were legally obligated to, and did, register people whatever their party affiliation, which included the Republican Party and the further right American Independent Party. We had no idea whether the person we signed up to vote was a Bernie supporter. We were not necessarily going to have further contact, to persuade the Bernie supporters to vote on Election Day.

Later the staff agreed that it was best to register voters as we canvassed neighborhoods, a task that was focused, in contrast, on the campaign’s main objective: contact voters, get a commitment to vote for Bernie, turn Bernie supporters out on Election Day.

GOTV (Get out the Vote):

On the last week-end before the election, the staff sent us to houses of voters we supposedly had identified as Bernie supporters. We could increase turnout by motivating them to vote the following Tuesday, Election Day. Most of the people on the list, to our surprise, had not been contacted before. Many had voted absentee and others intended to vote for Hillary. The campaign was wasting our time. More importantly, it risked motivating Hillary supporters to go to the polls.

I do not know how widespread the problem was. California had been expected to vote for Bernie but the turn-out was surprisingly low. Perhaps that was because voters assumed by that time that Hillary was the winner. Her campaign was implying that Bernie was a bad sport by not conceding the California race.

“The organizer has an obligation to explain, without letting anyone off the hook, how that hard work can and must be accomplished.”

Relationship to Bernie’s national campaign organization:

Although we began by running a separate operation before the national campaign arrived in the Bay Area, it affected our work before and after its arrival. The national campaign engendered a “do your own thing” mentality. People interpreted the on-line “how to” suggestions as encouragement to do whatever. As a consequence, undirected volunteerism was a problem.

One self-appointed volunteer-recruiter encouraged people to act in ways that were really a waste of their time, for example to wave Bernie signs at passing motorists from freeway overpasses. She was not aware of, and therefore did not explain, the campaign’s priorities at the little barnstorm meeting she convened in her friend’s back yard.

The “disorganizer” and the local director argued that the campaign did not want to discourage anyone who was inclined to volunteer. That orientation, in my mind, fails to meet the organizer’s responsibility to potential volunteers. They wanted Bernie to win. The organizer has an obligation to explain, without letting anyone off the hook, how that hard work can and must be accomplished.

The “do you own thing” approach was related to another shortcoming of the campaign. If it had numerical goals for the State and our local operation, they were not communicated to the volunteers. If the campaign kept track of the State campaign’s progress and the contributions local groups were making toward meeting its goals, the information was never published to the volunteer base. That presented a big problem. We did not know what we, or any of the other local operations, had to do to meet goals and whether we were doing our share or better. Meeting goals did not become every participant’s project. We were not empowered by knowing what we were accomplishing collectively.

Some self-criticism is in order:

Our phone banks could have been more systematic. Although we spoke with callers on an ad hoc basis, we should have conducted an orientation at the beginning of each shift that explained the stages of the voter contact: national calling, and then local calling, house-to-house canvassing, and getting Bernie supporters to the polls. We could have calculated the average number of voters contacted per hour and asked the caller to adopt that number as a personal goal and to keep track of the total calls made. We could have included an explanation how each caller’s results, although they may have appeared insignificant because voters did not answer most of the calls, combined with others to make an impact.

Our difficulty arose from the fact that callers arrived at different times between 10 and 3. But we could have conducted trainings every 10 or 15 minutes.

They also left at different times. That made it difficult to bring them together for their comments and our summary of what people accomplished collectively. We could have presented that tally if we had insisted that each caller maintain an accurate count of their calls (voters contacted and voters reached).

Top-down:

Some potential volunteers pushback against a campaign that is directed from the top. There is apprehension about structure, authority, organizers rallying them to produce numbers. They resist clear goals and continual measurement. They are unwilling to be personally accountable for their part of the campaign. We saw that tendency in the Occupy movement as well as, to some degree, during Bernie’s campaign.

To elect a candidate, the labor-intensive work of contacting voters has to be done thoroughly, in a finite amount of time. Of course, you have to have a hard working candidate who has no illusions about what it takes to win and helps focus the volunteers on meeting the campaign’s goals. Mail is important, and some endorsements help, but it is the superiority of the ground operation that makes the difference.

As many people as possible deserve the opportunity to participate in a well-functioning organizational structure that wins improvements in people’s lives. That happens on an election campaign when the candidate defeats her/his opponents. It is the experience of doing one’s part with others, building that kind of collective power, that increases the probability that volunteers will continue on grass roots campaigns.

Your relationship with the candidate:

Bernie explained to his supporters that an election campaign has to be about more than electing a candidate to office. It has to be part of an ongoing campaign to bring about significant improvements in our lives. It’s about organizing for a specific agenda before and after Election Day.

Sander’s biography demonstrates that his success in Vermont has depended on the on-going organization of his constituents. He meets with them periodically throughout the State to discuss the issues that affect their lives. He invites them to tell their personal stories at public forums, to formal bodies, to the media. The 80% support he received in Vermont’s last senatorial election is a product of many years of relationship building.

Even the best-intentioned office holder with the most progressive agenda is relatively powerless without the continuing activism of supporters. Yet, unlike Bernie Sanders, most of them make no effort to develop it. They fear that it would complicate their life. They depend, instead, on their limited power of persuasion and deal-making with other elected officials. They are drawn to the pomp, perks, and flattery that surround them. Typical office holders become isolated and remote from the average constituent. Their relationships are almost exclusively with (1) the campaign donors who can be persuaded to help them remain in office, and (2) the heads of, or legislative representatives of, key endorsing organizations that have a large presence in their districts (like big public employee unions). In addition, they count on their staff members to provide individual services to constituents whose loyalty they expect in return at the time of the following election.

“Before signing up to help a candidate get elected, insist on a specific agreement about the relationship that will continue after the election.”

What can you do to ensure that your candidate remains loyal to the constituents and to those of you who personally contacted voters to build support for a progressive agenda? Will the candidate take steps to continually expand her/his base among the voters throughout the electoral district? Will the voters be enlisted to present testimony to, and lobby, elected officials in support of the campaign’s agenda? Does the candidate agree that the data base of volunteers and supporters that you built during the campaign belongs to the organization that put it together to fight for the progressive agenda, that it is not the private property of the candidate? Will there be periodic meetings with the campaign organizers who fought to ensure the candidate’s election?

According to Dolores Huerta, Cesar Chavez referred to elected officials as “public servants,” to make clear that they are to serve their constituents, not the other way around. Before signing up to help a candidate get elected, insist on a specific agreement about the relationship that will continue after the election. Your effort to secure an agreement may reveal that you have chosen the wrong candidate.

Did the campaign produce a lasting organization?

From the time Bernie announced his candidacy, there was discussion about building an organization that would have a life beyond the campaign. That remains an open question.

A few days after the June primary in California, we convened a meeting of the people who showed up to do the work of contacting voters. Forty- five people attended and expressed their desire to have an ongoing impact on Bernie’s agenda, locally and nationally.

Anna Callahan, who emerged the most talented and energetic organizer, made the calls and ran the meeting. Her subsequent efforts to keep something going, however, have not had the desired success. It could be because there has been no agreement that everyone choose one project instead of dispersing to various campaigns. That is the problem that the 2008 Obama campaign invited after its victory when it urged people essentially to “do their own thing.”

Hopefully, Bernie will help focus the work of his followers. There should be only one or two options at a time. The project, or projects, should be about implementing the agenda that was central to his Presidential campaign. The appeal should be directive: this is what we need to accomplish by this date. Although top-down, it should be clear where individual and local creativity is in order.

Conclusion: What does all of this mean for the future?

First, reliance on social media is insufficient.

Second, there are models that combine the benefits of social media with organizing principles. Obama’s 2008 campaign built an organization out of personal relationships, trained leaders, and gave participants a role in the organization and an experience of collective power. That campaign was designed by Marshall Ganz, one of Cesar Chavez’s key organizers. Use of the new technology should be incorporated into that refined model.

Third, it is vital that thousands of people across the country learn the difference between effective organizing and mobilizing, between people who call themselves organizers and those who really are capable of building the power necessary to shift the power balance and create a vital democracy and just society. It is a set-back when campaigns waste the time of well-meaning people. They deserve better.

We have urgent and exciting work to do. Bernie’s Revolution is not a tea party. Only organizations built on the foundation of strong and respectful personal relationships can match the 1%’s monopoly power of money, military and media.

Go Red! – Thoughts on the Labor Movement in the age of Trump – Response to Fletcher and Wing – Portside December 5, 2016

By Peter Olney

Bill Fletcher and Bob Wing have written an important post election analytical essay with many excellent recommendations on the path forward. “Fighting Back Against the White Revolt” is a must read for all people of good will concerned about the future of humanity. Throughout the election period, both authors provided clear and clarion voices on the importance of uniting all to vote for Hillary to stop Trump and did education on the left to convince skeptics in the movement to vote for the lesser of two evils to stop the racist, misogynist, xenophobic, authoritarian Donald Trump. Everything in Trump’s behavior since November 8 upholds the wisdom of that advice.

Serious engagement in electoral politics is not the sum total of the struggle, but as we are witnessing in the aftermath of November 8, elections do have real consequences. Therefore any strategy must take into account the winner take all and electoral college features of our politic. As Fletcher and Wing point out, Trump won the election by a razor thin margin in three battleground states: Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania by the margin of 77,000, the size of a large union local. Labor’s turnout effort and union household votes clearly could have made an enormous difference in the outcome. That’s why it is so important to critically examine how organized labor failed to carry union households to the degree that Barack Obama did in either 2008 or 2012.

I argue that a defection of working class voters to Trump was key to the loss of historic battleground states, and thus the election. The change in Ohio is stunning: from a 23% margin for Barack in 2012 to a Trump margin of 8% in 2016 among union households. These are voters who have been voting for change at least since 2008 and they haven’t gotten it from a corporatist Democratic party.

The problem in Fletcher and Wing’s analysis of working class support for Trump is that they resort to income as a proxy for class. The working class is a many splendored thing, but the traditional Marxist definition of someone who works for a wage and does not own the means of production still resonates for me. But let’s put any doctrinaire disputes aside and look at the income argument. Fletcher and Wing assert that there was no massive defection of working class voters to Trump by pointing to the fact that Clinton won the majority of voters earning under $30,000 and under $50,000. By that line of reasoning, half the unionized workers in American would be cut out of the working class! My son, a fourth-year IBEW apprentice has just been displaced from the proletariat because his income is $30,000 over the threshold that Wing and Fletcher use. The pollster Nate Silver used the figure of $70,000 to debunk the working class support for Trump argument. Do the math. Divide $70,000 by 2087 annual work hours and you get $32 dollars per hour, hardly an outrageous hourly rate and not even a labor aristocrat’s rate! The defection of union households is an important number and accounts for the marginal shifts that proved definitive in those mid Western states.

The distinction is important because going forward there is plenty of work to be done among these workers who voted for Trump, many of them good union members. Fletcher and Wing acknowledge that: “A key starting point (in combating racism) will be to amplify the organization and influence of whites who already reject Trumpism. Unions will be one of the key forces in this effort.” There is cause for hope in the fact that the largest group in the more than 100 local unions that broke with their parent bodies to support Bernie Sanders were IBEW locals, (the union my son belongs to) where a journeyman in the Bay Area can make $125,220 a year. Of the thirty-six IBEW locals that endorsed Bernie, twenty-eight were construction locals.

None of this means that the points that Fletcher and Wing raise are to be negated, but it does mean that there is potential on the margins to shift significant sections of the electorate as the Trump anti-worker, anti-union realities set in.

Below is a slightly different and more narrowly focused trade union-based program. I modestly call it “Go Red!”

“Without re-establishing an allegiance with members who supported Trump, progressive electoral victories backed by working class union members will be much harder to achieve”

Organizers must go to the Red states, the Red counties, and to the Red members! “Organize or Die!” doesn’t just refer to external organization; it also applies to the singularly important task of organizing our existing members. Ignoring this challenge led us to the colossal disaster of a Trump presidency.

Look at the electoral map. We see slivers of blue on the coasts. And while there are a few exceptional inland pockets of blue, they are surrounded by a sea of red. What is to be done in these massive areas of Trump and Republican dominance in the most recent election? Unions have members who span the entire political spectrum. This is especially true in 25 states that are not yet “Right to Work,” where membership is a condition of employment.

The first part of “Going Red” is being willing to work in the “red” states, that is, those that Trump carried. Many of those who voted for Trump are good and loyal trade unionists. Before the hammer of legislative and court initiatives (ala “Friedrichs Two”) shatter compulsory membership, we have a superb opportunity to speak to the sons and daughters of New Deal Democrats who voted in key electoral states like Ohio, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin for Trump and helped him carry those states. These discussions cannot be approached as rectification and remedial sessions with “wayward” members, but must be part and parcel of massive internal organizing involving their issues, their contracts and their concerns. It’s time to come home and patiently build organization from the bottom up. And when union leaders and activists do, they should be prepared to hear some harsh critiques and serious questions.

This internal organizing cannot be accomplished by inviting members to meetings. Rather, we need to embed newly trained worker leaders into our work sites. Those leaders (Business Agents, Field Reps, Shop Stewards) responsible for contract enforcement cannot carry out this task. New armies of internal organizers are needed to talk to their sister and brother members about unions, politics, and the future of the working class. This internal organization on a massive scale must begin immediately to move this program because the resources for it may be considerably diminished within a year after the onslaught of “right to work” under the NLRA and the Railway Labor Act.

The second part of “Going Red” is labor’s new political project. Union leaders’ comfort with — and access to — the Democratic Party’s neo-liberal establishment just isn’t going to cut it. Our future lies with the exciting political movement within labor that we witnessed in support for Senator Bernie Sanders, the Democratic Socialist from Vermont. Not since Eugene Debs and his 1920 race from prison for President has there been a candidate who espoused our anti-corporate, pro-working class values like Senator Sanders. He captured 13 million votes, won the endorsement of six major unions and was supported by more than one hundred local unions — many of whom defied their International’s support for Clinton. Many Clinton supporters now realize that Bernie, with his “outsider” message, an uncompromising record, and decades of political integrity, would have been a far better choice to beat Trump.

Bernie Sander’s new Our Revolution organization needs a strong union core in order to sustain itself financially and organizationally. Unions that supported Bernie should consider coalescing in a new formation around Our Revolution. Unions that didn’t support Bernie should do some serious self-examination, consider a new path forward, and hopefully join with the Bernie unions. A new “Labor for Our Revolution” could be a network of national and local unions that actively engage their members in electoral politics at both the primary and general election levels to support Our Revolution endorsed candidates who reflect labor’s values. The Labor for Our Revolution network could link its political work with member mobilization around local and national labor struggles to defend workers’ rights and contribute to building a broader movement for social and economic justice.

“Going Red” by having a face-to-face conversation with all our members and launching a new political project are two tasks bound up with each other. Without re-establishing an allegiance with members who supported Trump, progressive electoral victories backed by working class union members will be much harder to achieve. Without giving those members an alternative political vision, like that of Bernie Sanders, there is no moving them politically. That alternative political vision must include the fight for multi-racial unity by recognizing and combating the pervasive effects of systemic racism.

Finally and perhaps most importantly, “Going Red” means being ready to make sacrifices to defend our brother and sister immigrant workers, Muslims, People of Color and all those who are hatefully targeted by the Trump administration. We can take inspiration from the recent efforts of thousands of veterans to stand with the Standing Rock native peoples. We can take inspiration from unions like the ILWU that sent their members to the Dakotas to stand in defiance of the energy companies. More of these kinds of sacrifices will be necessary to win the allegiance of all people to the cause of labor and the defeat of Trump.

“Go Red” to grow and win power!

This piece originally ran in the 26 December 2016 issue of Portside

More Than I Bargained For

By Gene Bruskin

It was 1978 at the swank Boston Park Plaza Hotel. The company was late. Our team sat in a fancy conference room with crystal chandeliers and a long dark wooden table with leather chairs around it. A gold-plated tray with ceramic coffee cups and a brass water pitcher sat in the middle of the table.