Regulatory Aversion

By Anthony Flaccavento

Scott Pruitt’s first few weeks at the EPA confirms most environmentalists’ worst fears: The Trump administration intends to dramatically scale back environmental regulations, along with the staff and resources needed for enforcement of what remains. Other federal agencies, it now seems clear, will also have foxes guarding their respective hen houses. Undergirded by Trump’s Executive Order requiring the elimination of two regulations for every new one proposed, we could well see a wholesale reduction in rules intended to protect public health, consumers, worker safety and the environment.

Millions of people – a strong majority of Americans, in fact – support stronger, not weaker regulations to protect the environment and public health. But that’s only part of the picture. A 2012 Pew Research Poll found that more than half the public believes that “government regulation of business usually does more harm than good.” My own experience suggests that this sentiment is considerably stronger and more widespread among farmers and in rural communities. So, why do so many of us dislike or distrust ‘regulations’?

A little more than four years ago I was speaking with a few dozen folks in a small town in southwestern Virginia. This was one of many community stops I made in my campaign for US Congress. Following my talk, folks were lingering and chatting, including a local businesswoman who owned a small grocery and retail shop. When I introduced myself to her and the others close at hand, she said, with great emphasis, “If you get elected, I only want one thing from you: Just leave me alone. I just want the government to leave me alone.” I told her that as a farmer, I understood some of how she felt, how the government sometimes imposed too many burdens on small farms and mom and pop businesses.

What’s the point of having regulations, and regulators, if the lives of miners or the livelihoods of rural residents are so dispensable?

As she and I had begun talking about government regulation, another conversation intruded. Apparently the owner of a now-closed filling station was allowing an underground tank to leak petroleum, some of which was seeping into the soil and a nearby creek. These neighbors, including the businesswoman with whom I’d been speaking, were all upset about this. “Something has got to be done”, she said. “Somebody has got to make him fix that!”

“But don’t you think “, I said, “that he just wants the government to leave him alone?”

From the liberal point of view, regulations are prudent, a necessary check on the powers of big corporations. Before the EPA, smog enveloped many major cities, industrial plants dumped toxins directly into rivers, and Lake Erie caught fire. Before we had labor laws, ten year olds worked in factories; before OSHA more than a hundred twenty women died in the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, one of many workplace disasters of that period. And in coal regions like Appalachia, miners died by the hundreds every year from explosions, roof falls, and other preventable accidents. Regulations protect us, our health, our safety, our environment. The big mystery for liberals is why so many people just don’t seem to get that, especially in coal country and most other rural places.

I think we’re long past due for an honest debate about government regulations, …”

In her book, Strangers in Their Own Land, Arlie Hochschild describes how so many people in rural Louisiana support the very politicians that fight regulation of the chemical and pesticide companies that they know to be poisoning their land, bayous and bodies. Why would they vote for people who want to weaken laws that prevent this death-dealing pollution? Paraphrasing one of the people she interviews, “It seems like if we spill a little oil from our boats, they’ll give us a fine. But when the big companies spill thousands of gallons of poisons into the creek, nothing happens.” One factor, then, is the belief that regulations have not worked, at least not to protect the average person. The families of twenty-nine miners killed in Massey’s Upper Big Branch Mine explosion in April 2010 would surely agree. In spite of 57 citations for mine safety violations the month before the explosion, and 600 in the prior year and a half, nothing was done to protect the miners. What’s the point of having regulations, and regulators, if the lives of miners or the livelihoods of rural residents are so dispensable?

And then there are the community banks, still an important part of many small towns and rural regions. These banks, according to a study by the Institute for Local Self Reliance, do four times more small business lending, per dollar of asset, than do Wells Fargo and the other Wall Street Megabanks. In spite of their critical importance in rural communities, nearly two thousand of them have closed in the past eight years, in part at least due to the onerous requirements of the Dodd-Frank Financial Regulations. A big target for Trump and the Republican Party, this law was intended to rein in risky lending and keep financial institutions from once again becoming ‘too big to fail’. Whatever the intentions, six years out, the big banks are as big as ever; their portfolios filled with high risk financial speculations. But smaller community banks, like miners in West Virginia or fishermen in rural Louisiana, seem to be bearing the brunt of regulations while the big boys coast.

I think we’re long past due for an honest debate about government regulations, rather than continuing to simplistically call for deregulation at every turn, or on the other hand, defend the regulatory state without recognizing the downsides. We might begin that debate with three basic assertions: First, we all live downwind or downstream from others. While the owner of that abandoned service station might well consider regulations to be meddlesome and intrusive, his neighbors sought the action of government to protect their water, land and property. Fundamentally, regulations are about protecting private property and individual persons.

Second, wherever appropriate we should work to construct “scale appropriate” regulations, rather than one-size-fits-all rules and requirements. The 2014 Food Safety Modernization Act is a relatively successful example of this, providing a substantially less burdensome set of requirements for small farmers selling primarily direct to their customers, compared with large growers shipping product across many states. Small farmers still need to follow sensible procedures in how they harvest and handle food, but the monitoring, reporting and infrastructure requirements they must meet are scaled to the size and risk of their operations. More scale-appropriate regulating of family farms, small businesses, community banks and local investors would reduce the burden on these critical parts of our economy and encourage their innovation and growth.

Last, like most public policy, regulations should help level the playing field between the average person and the rich and powerful; between the worker and owner. When people go to jail for shoplifting or a few dollars of embezzlement, while the richest CEOs face no charges for defrauding millions of people, it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that there are two different sets of rules. With that comes cynicism, and in the countryside at least, the belief that regulations hurt the little guy and further the interests of elites. That they’ll fine a fella for spilling a gallon of oil, but let the corporation get away with poisoning the whole bayou. Changing that belief is going to take a while, but focusing regulations on leveling the playing field for ordinary people would surely be a place to start.

With the U.S. Working Class Under Attack… Unions Can Reclaim May Day in Solidarity with Immigrant Workers

By Peter Olney and Rand Wilson

The buzz about a Day without Immigrants on May 1, 2017 is growing. Spanish radio is already churning with calls for strikes, rallies and demonstrations on May 1. This movement recalls the giant mobilizations of May 1, 2006 that occurred in response to proposed draconian anti-immigrant federal legislation called the Sensenbrenner Immigration Bill.

May Day has its historic origins in the nineteenth century struggle for the eight-hour day. In many cities on May Day in 2006, the marches and rallies proved to be the largest in history. Industries that relied on immigrant labor were paralyzed as millions of workers responded to the call for a Day without Latinos (also called the Great American Boycott). Labor participated unevenly in these rallies and mostly in places where the membership in service unions was predominately Latino. This year, in the turmoil surrounding the Trump Presidency, May 1 could be a great opportunity for the labor movement to flex its muscles and build its future.

Labor’s participation is important to the future of American politics. For example, look at the history of politics in California. Turn back the clock 23 years to 1994 when then Republican Governor Pete Wilson faced a fierce re-election battle. He launched a “Trump-like” assault on “illegal” immigration replete with videos of masses of Mexicans streaming across the border and threatening California. It was a brazen racist ploy called Proposition 187, introduced to bolster his reelection bid. Union leaders in California faced a critical decision about whether to participate in the massive Los Angeles mobilization against Prop 187.

In a meeting of labor leadership, some union leaders argued that it was important not to participate in the Los Angeles’ May 1 march so as not to alienate “Encino Man” — the Reagan Democrats of the San Fernando Valley and elsewhere. In the midst of a heated discussion, AFL-CIO Regional Director David Sickler made a dramatic plea to Los Angeles’ trade unionists:

“If we don’t march with these Latin workers, we will lose the confidence and trust of whole generation of Latinos.”

Sickler’s argument won the day, and Los Angeles’ labor turned out for the march. That action, and many others, solidified the labor/Latino nexus. In one generation, California went from “Reagan-land” to solid Blue Democratic.

Again the same challenge faces labor, however now it’s on a national scale. And the opportunity for the labor movement is equally huge. Supporting the upcoming May 1 protests, strikes and other actions will clearly demonstrate that unions are ready to be a champion of the rising Latino demographic. Conversely, sitting on the sidelines will mark us as bystanders to racist repression.

Recently building trades labor leaders blindly and naively embraced Trump’s agenda by meeting with him at the White House just days after his inauguration and lauding his commitment to build infrastructure and oil pipelines — but with no commitment to pro-labor codes like prevailing wage or project labor agreements. AFL-CIO President Rich Trumka — usually a strong voice for racial justice — recently embraced Trump’s talk of immigration reform after his speech to a joint session of Congress. Again, a major labor leader is blindly and naively playing into Trump’s racist rhetoric. These actions by the building trades and the leader of the AFL-CIO undermine the U.S. labor movement’s need to squarely be on the side of immigrants battling Trump’s racist rhetoric, executive orders and travel bans.

There are many possible levels of participation for labor and unions on May 1. Each union must determine what’s the most appropriate way to participate based on its members needs and consciousness. In California, SEIU’s United Service Workers West, representing over 60,000 janitors, security guards and airport service workers has announced on Facebook its support for a May 1 strike. The United Food and Commercial Workers, representing supermarket workers in Southern California and the hotel workers union (UNITE HERE) are both assessing their actions in California. California is fertile ground for these protests with a sympathetic and supportive political infrastructure and a demographic tidal wave that means that Latinos are now the largest ethnic group in the state — out numbering Anglos 39 to 38 percent.

These calls for strikes may snowball. On the hastily organized February 17 “Day without Immigrants,” tens of thousands of mostly Latin service workers in many cities and towns stayed home (in many cases with the support of their employers). Earlier in February, Comcast employees at the company’s headquarters walked out to march and rally against Trump’s immigration policies. There is no reason not to expect similar dramatic actions on May Day. The social fervor is such that strikes in certain sectors and workplaces are very possible and possible with relative impunity.

With the prospect of large rallies and marches on May 1, some other unions are talking about participating in an organized way — even if it means after work or on off shifts. Just visibly marching with banners and signs in support of immigrant rights would be important and impactful to the thousands of immigrants who will brave deportation to hit the streets. Unions at the national and local level have an opportunity to speak with one voice in defense of immigrants. In specific locations like Los Angeles, these unions and others may hold joint press conferences and public events. Equally important will be actions in the “heartland” where immigrants may feel more politically and organizationally isolated than on the coasts.

Some unions have already begun “Know Your Rights” solidarity trainings to prepare workers for Immigration Control and Enforcement (ICE) raids that could take place in the community and the workplace. Union halls could become “Sanctuary Sites” for the undocumented. And now is a timely moment for always appreciated contributions of money, materials and office space to immigrant rights groups.

In addition to SEIU’s United Service Workers West, several national political and immigrants’ rights groups are organizing for the May 1 Day Without Immigrants including: Solid (an open-source project offered by Brandworkers), Strike Core, Cosecha, and the Beyond the Moment March.

May 1 is the traditional international day of working class solidarity, a holiday born of the U.S. struggle for the eight-hour day. It can be reclaimed with gusto this year as a focused attack on the anti-immigrant policies of Trump. But more than that, it is a day to cement the alliance between labor and the immigrant working class.

THE NEW WAY TO LOS PINOS

By Joel Ochoa

On March 20 Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (Here and Here) visited San Francisco and appeared at a theater in the Mission District. His candidacy for the Mexican Presidency is gathering steam, and he is presently polling ahead of all other candidates. The Mexican election is in 2018 and retired IAM Organizer and immigrant rights activist Joel Ochoa comments on Mexican politics in the age of Trump. (Peter Olney)

The election of Donald Trump as the 45th U.S. President has affected, among many other things, the way Mexicans will elect their next President. All appearances indicate that the way to the official residence of Los Pinos, now runs thru the barrios where Mexicans reside in the United States.

Back in mid-2015 when Donald Trump announced he was seeking the nomination of the Republican Party to run for the presidency of the United States, he identified Mexico and Mexicans as the root of the moral and economic evils that, in his view, were causing the demise of American society. An extraordinary moment, it was Mexicans first; everybody else came later.

The message caught most everyone by surprise and the prediction of a short-lived campaign dominated the political discourse. However the message resonated among certain groups of voters who Trump was able to identify and target relentlessly with vicious attacks an enemy of convenience, Mexico and Mexicans, that at the end carried him to the Presidency.

Mexican leaders reacted with a nonchalance and naive attitude, giving Trump chief of state treatment in a visit to Mexico where he outshone President Pena Nieto. Once they realized Trump had painted them as incompetent and corrupt, that he was not backing down on his demand for payment of the infamous wall, and that he intended to renegotiate, or end, the terms of the North America Free Trade Agreement, NAFTA, they panicked.

On November 9, 2016 Mexico woke up to the realization that a game changer had occurred and the country was not ready to deal with it. Officially the cornerstone of the Mexican economy, NAFTA, was on Trumps “hit list” and remittances, about 28 billion annually, became a point of concern to Mexican finances.

Historically, people migrating to the north have served Mexico politically and economically. It alleviates social pressure created by lack of employment opportunities and is a source of tremendous quantities of income. Remittances, monies sent by Mexican immigrants to their families back home, are recognized by the government as a key source of income; clean money that is directly injected into the Mexican economy for which Mexico currently pays almost nothing. That is only a part of the money flowing to Mexico as a result of the hard earned income of millions of immigrants. At least that is the part that can be quantified. The other part has to do with services generated in Mexico and other countries; such as television programs, sports, publications and more. Immigrants also send money by less traditional methods utilizing a network of couriers that are expensive and not always reliable. Immigrants are part of an industry that has benefited both countries. As someone called it: “an industry with no furnaces.”

To put into perspective what kind of purchasing power the above represents, Mexican immigrants could buy, in one year, all the teams from the NBA. The entire league! And that is only the official part. We shouldn’t be surprised if there was more money available, that is sent thru non-traditional ways in addition to what is charged for services. Mexicans could probably buy up a ton of MLB or NFL franchises also!

The Mexican rich and political classes are fighting to keep the status quo created with the implementation of NAFTA. They are not ready to sacrifice and look for other markets. Their sense of patriotism doesn’t go that far. They would rather take the insult in order to keep, and sustain, what they have.

In that context, to keep their privileges, Mexican elites are projecting a more benevolent attitude towards the millions of Mexican living in the U. S. The view remains paternalistic in the sense that they still talk about “defending our paisanos” instead of recognizing how vital we are, and have been for a long time, to the Mexican way of life. Bottom line, they fear the loss of that source of revenue.

Since the election of Trump, or perhaps because of his policies, the pilgrimage of Mexican politicians to cities in the U. S. has become a constant. Governors, presidential aspirants and other functionaries are coming to “defend or protect” immigrants. The common denominator among those Mexican politicians is the lack of knowledge of what our real problems are. For most, this is no more than a photo op, something new to add to their resume.

Perhaps the exception is Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (AMLO) because he has surrounded himself with people knowledgeable of the problem. Jose Jacques Medina, a long time Los Angeles community and labor organizer is one such supporter. Lopez Obrador has been touring cities in the U. S. (his Los Angeles speech is here) but more importantly his followers have built a network of committees to facilitate civic participation.

But much more is needed. Mexicans escaped their country because of violence and the lack of opportunities. Going back to a nation in deterioration is not an option, at least not now, because there are no jobs, no special schools to train adults nor to integrate children, no security and on top of all this Mexico has to defend the very same policies of NAFTA that created the conditions that forced Mexicans to migrate.

Trump is a challenge because his policies could change the dynamics of how Mexico operates in the international market. With more than 500 billion dollars in trade flowing between both countries, the U.S. represents Mexico’s main trading partner (to the U. S. Mexico represents its third).

Mexico could opt for opening other markets; but it will be more costly and will imply losing access, at least for some time, to the most important market in the world. It will require a great deal of sacrifice and the patriotism of Mexican elites won’t go that far. My sense is that they, the rich and most of the political class, will take the insults, rather than sacrifice the privileges.

For as long as they can get a U.S. visa the parade of Mexican politicians will continue. Mexicans residing here can’t stop it or prevent it. However, we can demand respect and ask for tangible solutions. Mexican immigrants have the right to that and more. 28 billion dollars plus annually gives us that right.

Rewriting What Was: Distorting Pastor Niemoller’s Words

By Kurt Stand

We live in a time of historical amnesia with glittering generalities used to mask a lack of understanding of what brought us to the point where we now stand. As an example, Pastor Martin Niemoller’s injunction to defend others to defend oneself, is often quoted, as it should be for it has relevance to the challenges we now face. But in the process of being popularized it has been changed. The change, accepted without correction or challenge, has now become commonplace. To understand the significance of what at first glance might appear insignificant requires moving from generalities to specifics.

By way of background, Niemoller, like most German Protestant theologians, welcomed Hitler’s accession to power. Unlike most, he soon became a determined opponent of fascism, and was imprisoned in a concentration camp in 1937 where he remained until World War II’s closing days. Soon after his release he wrote the following lines:

When the Nazis came for the communists,

I remained silent;

I was not a communist.When they locked up the social democrats,

I remained silent;

I was not a social democrat.When they came for the trade unionists,

I did not speak out;

I was not a trade unionist.When they came for the Jews,

I remained silent;

I wasn’t a Jew.When they came for me,

there was no one left to speak out.

Before he died in 1984 Niemoller reworked and modified his poem a number of times — sometimes including those in German-occupied territories, the disabled, and others to his list of victims whose victimization too many ignored or wished away. Yet there was some consistency in his words too — for he began with Communists and ended with Jews, a bookend to a list that becomes a lie if forgotten.

Yet at the Holocaust museum and elsewhere, the word “Communist” has been dropped, replaced with “socialists,” as though Niemoller had written so, though he did not (for in 1945, even anti-communists recognized that communists were targets of fascism). This might seem like a quaint point in our post-Cold War time. Perhaps the change was made by those who fear the word might “confuse” those who equate Communism with fascism, Nazi Germany with the Soviet Union, thereby ignoring a truth, also widely accepted in 1945 and not by the left alone, the intimate connection between fascism and capitalism. Although “socialists” might seem to simply indicate a more commonly recognized left radicalism, its use removes the specificity of Niemoller’s original. Distortion, after all, distorts meaning.

The change in language contributes to the sense that social conflicts past and present are morality plays: good people on one side, bad people on the other, and never the twain shall meet. The air of self-satisfaction embedded in such simplifications reduces political questions then to an easily ignored morality, much like the Christian injunction to “love thy neighbor,” repeatedly uttered without context by those whose deeds condemn countless to hunger, illness and the ravages of war (unlike Martin Luther King’s same use of that phrase which had meaning for it was always and explicitly tied to context and content).

Chronology Behind Words

Thus it might be useful to recall certain facts about Hitler’s rise to power to remember why Niemoller said what he said. Although volumes could be written on this, the chronology below should be sufficient:

1932 —

November 6: second national elections of the year, fails to produce a stable government of center, right, left in any combination. The vote totals for the Nazis, Social Democrats, Communists (the three largest of the nearly dozen parliamentary parties) were as follows:

NSDAP — 11,737,010 votes — 196 delegates — 33.1% (6% decline from previous vote)

SPD — 7,247,956 votes — 121 delegates — 20.4% (1% decline from previous vote)

KPD — 5,980,162 votes — 100 delegates — 16.8% (2% increase from previous vote)

1933 —

January 30: German President Hindenburg appoints Hitler Chancellor with parliamentary support of other conservative, business-backed parties. Nazis begin to work with and within police forces in actions directed at Communist public events and in attacks against those working-class communities in which Communists or Social Democrats were dominant politically and part of the fabric of social life. Hundreds of anti-fascists were killed in resulting street fighting; storm troopers kill about 1,000 Jews in vigilante assaults.

Feb. 27: Reichstag Fire — Approximately 10,000 KPD members and other anti-fascists arrested throughout Germany. Although the Communist party was itself still technically legal, its publications were suppressed, its public meetings repressed, and open activity all but ended.

March 5: Elections — Despite repression the KPD receives 4,800,000 votes, 12.3% of total. The SDP’s vote dropped only slightly, receiving 7,100,000 votes, 18.3% of those cast. Meanwhile the Nazi’s use of government power enabled them to grow, though they still lacked a majority — they received 43.9% of the vote (17.200,00). Even with the support of other conservative parties, they were unable to attain the two-thirds parliamentary majority required to change the Constitution.

March 6: De Facto ban on KPD, all its remaining buildings, offices, presses occupied or destroyed. No parliamentary party protested, mainline Catholic and Protestant churches support the measures.

March 9: Arrest orders for 81 Communists elected to parliament, their seats declared vacant. Thousands more Communist leaders and activists (local, regional or national) arrested; others forced into hiding or exile. Concentration camps quickly built for political opponents (more than 100 by year’s end) and filled up, again, no parliamentary protest. With the KPD removed, Hitler now has his two-thirds majority.

March 20: Germany’s Central Trade Union organization (ADGB) declares that unions must be “apolitical.” It cuts all ties or associations with the SPD and declares its willingness to work with the new Nazi government.

March 23: Enabling (Emergency Powers) Act passed. This was the legal fig leaf used by the Nazis to end Germany’s federal system and allow Hitler to rule by decree. Although Germany’s parliament was thereby rendered without power, it was twice more brought into session to renew this Act through to World War II. Catholic parliamentary parties support the Act as do the main Lutheran and Evangelical churches. The SPD was the only party in Parliament to vote against the measure.

April 1: Nazis declare national boycott of all Jewish-owned businesses and stores.

April 7: First anti-Semitic laws promulgated excluding Jews from civil service and many professions, restricting access to schools. Laws followed prohibiting religious Jewish food preparation (animal slaughtering).

April 30: ADGB begins discussions with smaller Catholic and Liberal (Protestant) union centers about possible merger.

May 1: ADGB agrees to participate in Nazi sponsored May Day celebrations.

May 2: Nazis occupy all national, regional and local trade union offices, union funds confiscated, union leaders arrested, the ADGB dissolved by government decree. No protests issued by other still legal unions

May 9: SPD offices closed, its newspapers banned, its property confiscated.

May 19: SPD votes in Parliament to support Hitler’s foreign policy

May 23: Government outlaws all collective bargaining.

June 19: SPD elects new Executive Committee, removing Jews from national leadership.

June 22: SPD banned — National leaders and parliamentary delegates arrested. No parliamentary party raises any objection.

July 4 & 5: Catholic Parties (Bavarian People’s Party and Center Party) dissolve themselves under pressure. No mainline church offers any opposition. Soon thereafter Pope signs concordat (recognition agreement) with Nazi government similar to one previously signed with Mussolini’s fascist government in Italy.

July 26: Law of Revocation of Naturalization and Annulment of German Citizenship promulgated. As all Eastern European Jews were deemed politically suspect (irrespective of whether they were politically active or not), citizenship was revoked to all who had been granted it during the Weimar Republic. Another spate of anti-Semitic laws followed, taking away land ownership rights, discriminating against non-Jews married to Jews and further restricting employment.

The above chronology is not meant to provide an analysis of who did what and why, or to assign praise or blame. Communists, Social Democrats, and unionists made many mistakes and paid for those mistakes dearly. Much of what was done that failed took place out of a misconceived attempt at preservation of some working-class space by organizational leaders unable to see a way out of the morass other than by narrowing their vision. Throughout all this, many acted heroically, including some who acted so short-sightedly in 1933. Many acted with insight, resistance never abated, and working-class opposition was never wholly overcome. That said, internal resistance within Germany was unable to overcome fascism through its own actions.

Niemoller’s words live on because they express the human cost of self-focus at the expense of mutuality”

Content of a Loss

The pattern of developments noted above was familiar to Niemoller and others of his generation. The attacks on Communists, Social Democrats, unions, attacks on working-class institutions and communities, led each to be isolated. This was interwoven with attacks on populations (Jews, later Roma, Slavs, the disabled, gays and others) that were even more vulnerable. In the process, civil liberties were lost (including liberty of conscience) which finalized his fate and that of may others who spoke up too late.

Most people today are unfamiliar with this history except in the most general terms. Niemoller’s words live on because they express the human cost of self-focus at the expense of mutuality; they are meaningfully changed and altered over time as a reminder of the need to stand in solidarity with groups or segments of the population under attack at any given time. To the extent that this is done with a real specificity of who is named, who is under threat, so much to the good.

But when “communists” are removed by those who otherwise quote Niemoller as he wrote because they are “unwanted” victims, then a sign is given of a partial solidarity that fails the test of solidarity altogether. Perhaps an analogy can be made when defenders of vulnerable populations ignore the plight of a vulnerable population closer to hand – such as those who are (or have been) in prison, for it means the support that is given is itself contingent upon impression and circumstance. Moreover, eschewing Communists as victims is part of the process of separating defense of liberties — freedom of speech, assembly, press — from active use of liberties to create more social justice, to make use of democracy to advance popular power, social justice, and freedom through equality. Niemoller never abandoned his rejection of anti-Communism, even when it quickly resurfaced in Germany during his lifetime.

Which is, perhaps the final point — Niemoller’s words can be taken as a sentiment of good intentions or a call to action. If the later, than it is best to use it to remind us of how we should defend our rights. Communists, Social Democrats, unions were victimized because they were rooted in working-class communities and, even with all their respective weaknesses, formed the only break on the untrammeled greed of power. The Jewish community was the despised minority, human beings who served as the vehicle for hatred redirected away from the real source of oppression, as a vehicle to be used whenever the powers that be desired to whip up sentiment for war. We are not talking here of some abstract evil, we are talking about particular policies put in place for particular purposes of maintaining and expanding the power of the already powerful — a far more cold-blooded evil for that reason.

… so we see three clear targets of the right inside and outside of government.”

Our Own Time

Today’s equivalents are different from Niemoller’s time — yet the same. The targets are not left-wing groups that lack the roots and strengths they had in 1933 Germany; and though bigotry in all its ugly forms runs rampant through the Trump Administration, it is not bigotry for its own sake, but rather bigotry promoted with clear purposes in mind. If we want to build the mutual support needed to defend ourselves, if we want to build the mutual support needed to create an alternative power for social and economic justice, than we need to be clear about where the mainline of fire is being directed and why, for it is not aimed at the most radical, but at the most rooted.

And so we see three clear targets of the right inside and outside of government. This includes the AFL-CIO because it is an institution of alternative power and alternative thinking within the working class. Federal and other public worker unions are in particular on the chopping block because they represent defense of public programs, defense of the social over the individual. Unions are attacked simply because they exist, irrespective of whether they are weak or strong, conservative or progressive, self-interested or solidaristic.

So too, Planned Parenthood is a target — not because it is the only defender of reproductive justice and abortion rights (there are many others), not because it is the most progressive (it isn’t), but because it is the institution with the most widespread network of clinics for working-class and poor women, the institution able to exercise more power than others to help preserve the bodily independence that is needed to avoid social dependence.

And so is Black Lives Matter, even though it does not have millions of members or institutional strength, but rather because it stands forth as ready and able to mobilize to defend communities facing most directly institutional violence in all its forms, because it has been able to bring into action those most marginalized by the system, and because it has recognized and acted upon the intersections of all layers of discrimination and oppression.

As for the communities themselves at the knife’s edge in Trump Administration rhetoric and policy, we see two: immigrant communities (especially those from Mexico and Central America) because popular discontent over the state of the economy is being misdirected toward them. And Muslims, because attacks on them provide the most direct excuse for suppression of civil liberties, and the most direct excuse for continuation of current wars and preparation for future one.

If the spirit of Niemoller’s injunction is to serve as a warning heeded rather than nice words on a poster then we should never forget why he wrote as he did in 1945. We need to defend those under siege today with equal clarity about who is attacked and why. Opposition to repression must begin with defense of those on the frontlines of resistance to that oppression.

The Stansbury Forum Resource List 01

By Robert Gumpert

With times being what they are we at the Stansbury Forum thought a resource list might be useful. This list is neither definitive nor singular: we, with your help, will update the list periodically.

Political Action

Swing Left

Knock Every Door

Town Hall Project

The Resurgent Left

Run for Something

Our Revolution

flippable

Sister District Project

Indivisible

Training

Know Your Rights

ORGANIZE Training Center

UC Labor Center

The Worker Institute

Highlander Research and Education Center

General Interest

Democracy Now

The Texas Observer

ProPublica

The Pew Research Center

Portside

The Pump Handle

The Intercept

Yes! Magazine

The Real News

VOX Topics

Alternet

Urban Institute

Open Democracy

Narratively

Pulitzer Center

London Review of Books

Arstechnica

Quartz

The Conversation

The Guardian

NY Times

LA Times

Washington Post

Lapham’s Quarterly

In These Times

Rewire

Sport

Edge of Sports

International

Asian Correspondent

New Mandala

Soufan Group

Social Europe

Understanding Society

US Labor Against the War

Transform Europe

Red Pepper

Morning Star

Spectrezine

Il Manifesto, Global Edition

Culture and Society

Aeon

Alt.Latino

Longreads

First of the Month

Oxford American

The Blue Moment

Texas Monthly

Huck Magazine

Appalshop

Politics

Crooked Media

TomDispatch

TruthDig

TruthOut

CounterPunch

Immanuel Wallerstein Commentary

ROAR Magazine

Moyers and Company

Border Criminologies

Color Lines

Southern Poverty Law Center

Kentucky Rural-Urban Exchange

Talking Point Memo

Think Progress

Committee to Protect Journalists

Economics

Americans for Financial Reform

Institute for Policy Studies

Labor

Labor Network for Sustainability

Labor Notes

Jobs with Justice

NYCOSH

National Domestic Workers Alliance

Sexworker Open University

International Labor Organization

Migrant Sex Workers

Teamsters for a Democratic Union (TDU)

NY Taxi Drive Alliance

Show Me 15

Los Angeles Garment Worker Center

International Transport Workers Federation

Union Solidarity International

Equal Times

RankandFile.CA

Talking Union

Criminal Justice and Law

The Marshall Project

Center for Court Innovation

Center for Justice & Democracy

Vera Institute for Justice

Prison Policy Initiative

Center for Constitutional Rights

Homelessness

National Coalition for the Homeless

Street Sheet

Human Rights and Immigration Issues

Human Rights Watch

ACLU National

Amnesty International

IRIN

Beyond Slavery

End Slavery

National Council of La Raza

Immigrant Defense Project

Center for Constitutional Rights

Anti-Slavery International

Edjustice

My Undocumented Life: Up-to-date information & resources for undocumented immigrants

Immigrant Defense Project

National Council of La Raza

Health Care

Introducing Vital Signs

Planned Parenthood

How the Super Bowl Trumped the Mexican Constitution

By Álvaro Ramírez

This week The Stansbury Forum is running three posts from Professor Álvaro Ramírez’s blog “Postcards from a Postmexican” where Profressor Ramírez tries as a twentieth-century person to make sense of the twenty first century with its transnational and post-national realities that many people live today in countries such as Mexico.

18 February, 2017: How the Super Bowl Trumped the Mexican Constitution

Last Wednesday, some students studying in Cuernavaca invited me to Tónic, a local hangout, to watch the Mexico-Iceland friendly soccer match. Besides a table with eight students and myself, and a couple other tables with six men, the bar was completely empty. What a stark contrast with the scene just a few days earlier on Sunday February 5, when the same bar, as well as many other restaurants and sports bars across the city, was filled to the brim with enthusiastic Mexican fans of American football watching the Super Bowl game between the Falcons and the Patriots.

You would think that now that so many are calling for Mexican national unity during these times of uncertainty brought on by the Trump menace, that Mexicans would be unified behind the national team that, as usual, was playing a friendly game in the United States and not in el Estadio Azteca (much more lucrative to play in Gringolandia). But no, Mexicans gave their team the cold shoulder, they didn’t come out in droves to watch the game (unlike the paisanos in the USA) and went about their normal daily lives, leaving my Mexican American students from California and Oregon disappointed and baffled.

Why so much enthusiasm for American football and so little for el fútbol mexicano? This attitude is peculiar to say the least since for weeks now the Mexican media has been pummeling Trump and his supporters. Everyday newspapers, radio, television, and all social media blare out negative stories: no to the deportation of immigrants, no to the Beautiful Wall, and we’re not paying por el pinche muro! Says Mr. Fox. The frenzy has been bewildering. Then, the sacred day, Super Bowl Sunday, arrived and everyone calmed down and for a day forgot about that damn wall and the paisanos that are suffering persecution on the other side of the border. Mexicans with the means to do so made reservations in restaurants and bars, some had parties at home, and still others somehow found time to sit in front of a modest television set to watch the game and root for…The Patriots! I could handle all of this if at least the majority had been on the side of the Falcons, but no, most of the Mexicans wanted Tom Brady and his coach, Bill Belichick (both Trumpers) to lead the Patriots to victory. Go figure.

What’s really comical is that as the Mexican fanatics jumped up and down with joy at the end of the thrilling game and talked about how great Brady was, I wondered how many of them knew that that same day Mexico was celebrating the one-hundred anniversary of the country’s constitution. Probably not many cared since to most Mexicans la Magna Carta has the value of a roll of Charmin paper. Few of them, I’m sure, had watched earlier in the day, around noon, as President Peña Nieto, his cabinet and all the other politicos representing the motley crew of useless political parties praised the equally useless, patched-up quilt of paper that is La Constitución Mexicana. The same pomp and baroque circumstance and discursos tan refritos that only give us lots of gas (y no del gasolinazo!).

But these fake Mexican patriots made sure to schedule the boring ceremonies early enough not to conflict with the true celebration that all of their non-compatriots were waiting for. So well before 5:00 pm, they put away the banda de guerra that had played the national anthem in front of el Teatro de la República in the city of Querétaro, where all these stale political theatrics took place. Then, the President, his cabinet and his generals, and the minions of the PRI, PAN, PRD, Morena and, let’s not forget the powerful, Partido Verde, they all scurried out of the theater and probably ran as fast as they could to their rich, confortable homes to sit in front of giant plasma televisions, surrounded by the best food and drink imported from the USA, and watched the football game and rooted and hollered for … The Patriots!

18 February, 2017: The Appearance of Mexican National Unity

Since the inauguration of Donald Trump, it has been great to see how the people of Mexico, from all walks of life, have suddenly found a reason to finally unite under a common cause other than when our national selection (some call it deception) soccer team plays a match against its despised American counterpart. Trump gave us the perfect pretext to create solidarity across the country. His negative image and words have penetrated deep within every aspect of Mexican society. How deep? Well, the other day some of my students who volunteer at a local primary school, La Esperanza, told me than when they met the children, who are indigenous and from the poorest sections of Cuernavaca, they asked the school kids if they knew any English words. The children quickly began to count from one to ten in English. And when my students asked if they knew any other words: many of the indigenous kids immediately yelled out, TRUMP!

Yes, Trump has made his way into the collective Mexican unconscious and has brought to the fore once again that anti-American sentiment which every generation that grew up under the PRI’s seventy-year regime learned well in school, a sentiment that has been disappearing with the NAFTA Generation who aspires to be American in cultural terms. It would seem, then, that Mexico has rediscovered its “other,” and it is none other than Trump and his republican followers.

Taking advantage of this newfound solidarity, some politicians and activists called for a national day of demonstration with the catchy name, “Vibra México,” that took place yesterday, February 12, in several cities across the country. The goal was to show the country’s repudiation of the Trump policies that, if implemented, will damage Mexicans, such as deportation of undocumented immigrants and the repeal of NAFTA. Pero, México no vibró, the people stayed home, only some 20,000 participated in Mexico City, a paltry turnout when you take into account that the metropolis has over 20 million people. The rest of the country did not see any larger turnouts either.

So, what went wrong? From the start some critics pointed out that the demonstration was way too late since in other parts of the world that are less directly affected by the new American president have shown their disagreement by demonstrating against Trump’s ideology since January 20, the day of his inauguration. Others asked: why not clean our house first? That is, protest against the violence, poverty, and corruption that have brought the country to its knees. Still others, didn’t want to participate for to do so, they argued, would amount to support Peña Nieto who is even less popular than the members of Congress in the United States.

So while Mexicans appear to have found the “other” that has reawakened their dormant nationalism, it seems that Trump does not have to worry much, at least for now. As usual, Mexican unity has proved to be an ephemeral event that last as long as a juego de fútbol. Even worse, as in other occasions such as during the Mexican Revolution, Mexicans have the tendency to unite momentarily against a common enemy, but that unity quickly disintegrates as they realize that the enemy, that is, the “other,” is also within. Poor Mexico, so far from God and so close to the “other.”

25 February, 2017: The Apotheosis of the Mexican Emigrant

A hundred years ago, as the Mexican government was unveiling its touted new constitution with lots of fanfare, hundreds of thousands of its citizens were desperately trying to reach the USA. By some estimates by the late 1920s, ten percent of the population of Mexico resided in El Norte. As such, the revolutionary state was born in a deformed state. One of its vital and most productive parts was, let’s say, delivered separately to the wrong national home. Maybe the stork got a bit confused because only 69 years earlier, the American Southwest was the Mexican Northwest. Be that as it may, the fact is that ever since, with the exception of the 1930s, roughly ten percent of the Mexican population has made the United States its permanent home.

It’s quite embarrassing when a so-called revolutionary state can’t entice its people to remain within the nation’s geographical limits. What pissed-off the Mexican government the most was that they were losing people mainly to the United States, which was supposed to be our rival and enemy, the threat that helped to coalesce the new, national, revolutionary society. Several strategies were used to stop the hemorrhage of people, but much to the chagrin of the government, the tactics failed and massive waves of migration ended up establishing two Mexicos: México de Adentro and México de Afuera. The first more or less bound to the Revolución, the second trying to bound itself to the USA.

The relations between these two Mexicos were strained through most of the twentieth century with the Mexicanos de Afuera often being portrayed in Mexican literature and film as pochos, traitors, and malinchistas. The image during the Bracero Era (1942-1964) was perhaps less negative since most of these workers kept Mexico as their main home; but as soon as they were able to get their green cards after the program ended, these former braceros quickly moved their families to El Norte and were followed by another massive wave of circular migration, both legal and illegal, in the decades of the seventies and eighties. Most of these new emigrants established roots throughout the American Union after Ronald Reagan granted the undocumented amnesty in 1986, not out of his goodness but because he knew the Capitalist Machine needed them as workers and consumers. Los Mexicanos de Afuera had attained an economic clout that made us somewhat desirable in Gringolandia, not yet ready for primetime citizenship pero ya teníamos nuestro encanto económico.

In Mexico, the Mexicanos de Afuera began to show their newly acquired clout by transforming white adobe villages into reddish tabique towns. Tile floors and cement roofs with water tinacos became the sign of progress. Brand new cars and trucks of all makes with placas from many American states roamed the dusty streets of the Mexican countryside. Campesinos dressed in Gap clothes attended quinceañeras, bodas and bautizos. Our hard-earned dollars pumped new life into the sending towns and small cities of los Estados Unidos Mexicanos, but socially México de Adentro was ambivalent toward the flaunting of our migrant dollars: many viewed us with a bit of envy and refused to acknowledged we had made good in El Norte: “Todo ese dinero no nos quita lo naco, they said.” Naco (low-class, ghetto) the new adjective directed at us con desprecio, the new word that Mexicanos de Adentro flung at us along with the old favorites, pochos y malinchistas.

The government, on the other hand, wised up quickly when they realized that la gallina naca was laying lots of golden eggs in the form of dollar remittances and money spent on Christmas vacations, among other things. They had to find a way to keep us laying the golden eggs, that is, they wanted us emigrants to continue sending the monthly checks and coming back to our hometowns, even if it was only for a couple of weeks each year; so they launched an aggressive campaign under Salinas de Gortari: El Programa Paisano. Oh yeah!

First on the list, was to get rid of all the vampires at the border, that replica of Transylvania that made our life a big hellish mordida, and that we had to cross to get into Mexico. Now we were the paisanos that had to be protected at all costs from these Mexican border harpies and leeches. The change of attitude made it patently obvious that the government was trying to bring together the two Mexicos, to create a good relationship between its two peoples: no more pochos and malinchistas. Now, Mexicanos de Adentro y de Afuera were all paisanos. We could feel the love, but it wasn’t all there yet, something was still missing.

We could feel the love, but also the silence of México de Adentro when in 1994 Pete Wilson kicked Mexican immigrants around like a world-cup soccer ball. We could feel the love, but also the silence of our compatriotas mexicanos when the Clinton Wall went up at many border cities of the Southwest as part of the infamous Operation Gatekeeper policy forcing emigrants to cross through the gates of a hellish desert where thousands perished. We could feel a lot of love when in 2001 Vicente Fox and Jorge Castañeda were on the verge of negotiating the whole immigrant reform enchilada, which unfortunately ended up buried under los escombros de las Torres Gemelas de Nueva York.

Yes, we, the Mexicanos de Afuera, are now the darlings of the press and of the fake políticos of Mexico, we’re hailed everywhere as heroes of la Madre Patria.

In 2006, los paisanos living in the U.S. demonstrated that they not only had economic clout but also political power when they came out by the hundreds of thousands to protest and demand a just immigration reform. These actions forced los Mexicanos de Adentro to end their silence and finally show their full support for the other México. Suddenly, we were the object of lots of positive chatter in Mexican political circles and commentary in television programs and major national newspapers. We were no longer referred to as los emigrantes que se van al norte, now we were nuestros emigrantes para acá y nuestros emigrantes para allá.

The truth may be that Mexicanos de Adentro had no other choice but to accept us with our naquedad or naco-ness and all. It’s not just that a large percentage of México de Adentro has a relative in México de Afuera. No, what many have realized, especially government officials of all stripes, is the fact that los emigrantes form one of the important pillars of the Mexican economy. Hell, we may even be part of two main pillars: yearly remittances (27 billion dollars in 2016) and tourism (19.5 billion in 2016), for who knows how many billions of dollars we spend on our vacations in México throughout the year.

So, it’s only right that Mexican emigrants be treated with great respect in our country of birth. Gone are the days when many said that “sólo lo peor de México se va al Norte.” When Trump expressed similar sentiments, lots of Mexicans were pissed to the max. The reaction in Mexico’s press and political circles was to put us even higher on the pedestal: This man is offending “nuestros compatriotas, nuestros paisanos que trabajan muy duro del otro lado. We must unify behind our migrantes and protect them from los pinches gringos racistas.”

Yes, we, the Mexicanos de Afuera, are now the darlings of the press and of the fake políticos of Mexico, we’re hailed everywhere as heroes of la Madre Patria. Estamos de moda, trendy, the flavor of the month, but I got a feeling that this hero worship is due more to the fact that Trump is threatening the pillars of the Mexican economy that we represent. The Tasmanian Orange Devil’s immigration policies might kill the gallina que pone los huevos de oro, and the Mexican government is scared shitless and doesn’t know how to counter the move. For now they have only resorted to having Peña Nieto welcome repatriates at the airport: “Bienvenidos a su casa,” he says. “Here you’ll find lots of spaces for opportunities,” but we know this is all a political show.

Today, Mexicanos de Afuera are definitely on the hero pedestal. México celebrates us on December 18, “El Día del Migrante,” and soon there will be statues of us everywhere. I suggest that since Mexicanos de Adentro love monuments so much, what the government should do is erect one at the border similar to the Statue of Liberty; for instance, a giant China Poblana facing Gringolandia that welcomes returning migrants with an inscription that says:

“Send me my hard-working migrants to visit their land of birth, send me their huddled masses of children yearning to rediscover their roots on our teeming shores of Cancún, Cabo San Lucas, Ixtapa-Zihuatanejo, Puerto Vallarta and good old Acapulco, but don’t forget to come with your pockets full of money to spend, and, above all, don’t forget to send to me your billions of dollars every month for without them, México shall perish.”

Talking with a friend about Trump voters and how to reach them

By Garrett Brown

Dear Garrett: Yes. I’ve been having this nagging thought that while it’s important to resist, we’re still not getting the message that an awful lot of people voted for Trump and think he is doing a swell job. I still can’t see them. My former brother in law is one, but I have no idea how one would find common ground with him. But clearly, we lost all three branches of government, so what’s the message?

Abrazos, S

February 26, 2017

Dear S: Sorry for the radio silence – I have been tied up with various little projects that always seem to grow once you get into them.

Also I was thinking of how best to respond because I have been thinking about all this, the same as everyone. So, I will try not to go on and on, but I did want to reply about a couple issues.

I think there are multiple groups among the 63 million Trump voters. About half – 30 million or 10% of the US population – are straight-up racists or white supremacists or male supremacists or neo-fascists. These people are unreachable for us, and I am not that worried about that 10% of the population. If your former brother-in-law is in this camp, then I don’t think there is anything to say to him.

But the other half of Trump’s voters – another 30 million people – include various groups including people who voted once or twice for Obama and people who voted for Bernie. I do not consider these people to be white supremacists or neo-fascists, as much as I disagree with their votes.

What they did do was to overlook, tolerate or excuse-away the racist/misogynist/xenophobic campaign Trump ran. It is something worth pondering: how is it that things we think are automatically disqualifying and completely unacceptable, are somehow not that way for millions of people “who should know better.”

Reality is always 100 times more complex than theory, and we all know people who can and do hold conflicting ideas and attitudes in their head at the same time, which they often act on as well.

Having read 20-plus different articles and profiles on Trump voters, especially white working class voters rather than the right-wing ideologues, I think I had not really appreciated what the last 20-25 years of corporate globalization has meant for millions of working people in the “Rust Belt” and rural areas.

With the plant closures (due to automation and technology as well as “free trade”), with the decline of the union movement to its current 7% of the private sector, with the absence of any jobs with decent pay and benefits, and the tax base to pay for government social service – formerly Democratic working class people have seen their own lives, their families and their communities torn apart at the seams.

Moreover, all these communities were completely abandoned by the political class – Democratic as well as Republican – for years and years; left to twist slowly in the wind and told it was their fault that they were missing out. Some of the people interviewed said that they might have accepted that for themselves, but the thought that their children would have worse lives and a bleaker future than them was too much.

All they were promised by Democrats in this election was more of the same, with a slight technocratic tweaking that would do nothing to change the trajectory of corporate globalization that is immiserating working people in both developing and developed countries. Clinton epitomized the privileged, corrupt elite that is responsible for the destruction of their own lives, families and communities – which are now consumed by drug addiction, economic stagnation and early deaths.

It rang out from all the interviews that these people – Trump’s 30 million “reachable” voters – that they were convinced they are screwed, no matter which candidate won the election, so they might as well vote for the non-politician, “successful businessman,” who had the entire establishment lined up against him. This was a “hail Mary pass in the 4th quarter” – as one of them said – that was the “last, best chance” for a revival of their communities and families.

Their vote was in spite of the things that Trump said that were automatically disqualifying, unacceptable for us. So, while I understand the rationale for voting Trump – it ends up with a regime that will be worse for everybody, including the white working class voters who once belonged to a union, or who voted once or twice for the first black president, or voted for a self-described socialist.

On another point you raised, I also don’t think that the 30 million reachable Trump voters think he is “doing a swell job” – the racists, misogynists and fascist wannabes no doubt think he is not evil enough. But the polls – with whatever caveats are necessary – indicate:

• Trump’s transition had only a 45% approval rating;

• Trump started out his presidency with a 42% approval rating – the lowest of any president in the polling era;

• Trump made history again in generating a majority disapproval rating – again the polls may not perfect but the same questions have been tracked over years – in only 8 days as president. It took Bill Clinton 573 days, Reagan 727 days, Obama 936 days and George W. Bush 1,205 days to slip below 50% approval rating; and

• a majority of people polled from both parties (59% of Republicans and 76% of Democrats) say they are “stressed” about the future of the country under Trump.

At the same time, the Resistance is getting majority approval for both activities and issues:

• 60% approved of the women’s marches, with 33% strongly approving;

• 60% are opposed to building a wall on the southern border;

• 53% are opposed to halting refugee arrivals;

• 70% are in favor of offering illegal immigrants a chance to apply for legal status;

• more than 60% want the EPA’s regulatory powers maintained or strengthened; and

• 56% believe Wall Street is still a threat to the US economy.

Also the “bet” that the 30 million reachable voters made that their lives are going to get better with Trump is clearly not going to work out for them. Trump’s Cabinet of millionaries and billionaries are interested only in more inequality, and their policies can only bring more poverty, illnesses, and lives with no future.

A few thousand new manufacturing jobs – at reduced pay and minimal benefits – is not going to replace the 8 million good manufacturing jobs with decent pay and benefits that have disappeared over the last 20 years. Their families and communities will still be in the race to the bottom, invisible and abandoned – all so that corporate profits continue ever-upward.

So, for me the question about the 30 million reachable Trump voters is how long does it take for them to realize they have been snookered, who do they blame (could work our way or the other way), and what do they do about it.

Part of having it go our way when the Great Disillusionment occurs for the 30 million, I think is for us to pay more attention to and look for common ground with these 30 million and their families.

Obviously, we have to fight to protect all those vulnerable, and to fight every “turn back the clock” proposal out of the White House and Congress. But I think if we do not adopt the smug, patronizing, condescending attitude of the liberal elite toward working people, we can find common ground for discussion (for a start) and perhaps joint action on issues like:

• decent jobs with livable wages and benefits;

• access to quality health care, especially for diseases affecting rural and working class communities (of various colors);

• real retirement and pensions so people don’t have to work until their dying day;

• quality care of veterans (who are mostly working class of various colors in the “volunteer” military) – in terms of health care and jobs and homelessness; and

• the future of their and our children – most people care more about their kids than themselves, and this is something we can try to connect on in terms of the items above but also the environment and climate change (for those who have not gone back to the 13th century on science).

Sorry for being so long-winded, but I think we should not give in to the “fake news” that we lost, or that all Trump voters are unreachable, or that we cannot expand our majority with people (regardless of their 2016 vote) whom we actually share common ground, and need to win over if the country we want to live in and pass on to our children is to come about.

Un gran abrazo,

Garrett

Debating the Working Class 50 Years Ago in SDS: Lessons for Today?

By Joe Allen

Fifty years ago in August 1966 delegates from across the United States attended the annual Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) Convention in Clear Lake, Iowa. Located in north central Iowa and held at a local Methodist camp, it provided a bucolic setting to debate its future.

SDS was at a crossroads in 1966. It had evolved into the largest radical student organization in the United States and was going through a major membership and political transformation, according to SDS historian Kirkpatrick Sale.

For attendees, Clear Lake convention—350 delegates from 140 chapters meeting from August 29 to September 2—was symbolic. Leadership was now transferred from the original members to the newer ones; from those born in the left-wing traditions of the Coasts, to the middle-American activists. It was the ascendance of ‘prairie power.’

The biggest topic at the convention was what direction SDS should take.

The small delegation from the Independent Socialist Clubs (forerunner of the 1970s International Socialists) made a quite radical proposal to the convention.

“The socialist view of the working class as a potentially revolutionary class is based upon the most obvious fact about the working class, that it is socially situated at the heart of modern capitalism’s basic, and in fact defining institution, industry,” wrote Kim Moody, Fred Eppsteiner and Mike Pflug in Towards the Working Class: An SDS Convention Position Paper (TTWC).

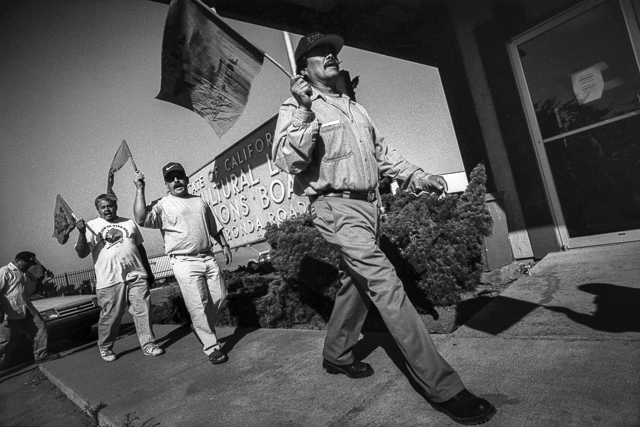

It was one of the first attempts to orient the New Left around the rank and file struggles of U.S. workers. Stan Wier’s pamphlet USA: The Labor Revolt was the road map that socialists used to understand the burgeoning rank and file rebellion that began in the mid-1950s away from the media spotlight but by the mid-1960s was visible for all to see. It was front-page news.

The settings are very different, but are the debates from a half-century ago relevant today?

The year 1966 may best remembered as the year in which during the “Meredith March Against Fear” in Mississippi, SNCC leader Stokely Carmichael (later known as Kwame Toure) declared, “What we need is black power.” That slogan captured the imagination of a generation of young Black revolutionaries frustrated by the broken promises of U.S. liberalism who demanded a radical transformation of society.

Many other long oppressed peoples followed—Women, Chicanos, Native Americans, Gays and Lesbians, for example—took up the demand for “power” to liberate their communities.

Moody, Eppsteiner, and Pflug were no less interested in the questions of power and liberation. All three were veterans of the civil rights movement in Baltimore, and active in or around the Baltimore SDS at Johns Hopkins University. Moody was also active in the Baltimore SDS’s community project, U-Join (Union for Jobs and Income Now). Moody and Eppsteiner were members of the Independent Socialist Clubs (ISC) while Pfug was a member of “News and Letters”.

The ISC emerged out of a split in the rightwing of the Socialist Party led by the aging Norman Thomas. The political inspiration for the ISC was Hal Draper, a veteran revolutionary socialist and author of the extremely popular pamphlet “The Mind of Clark Kerr.” It was an examination of the president of the University of California system, and his ideas for the modern university. It became the bible of the Free Speech movement at Berkeley.

Later Draper also popularized the term “socialism from below” in the magazine New Politics, reclaiming the revolutionary democratic spirit of Karl Marx’s belief that socialism could only be achieved through the “self-emancipation of the working class.” “Socialism from below” was a quick and clear phrase to distinguish revolutionary socialist politics from the “socialism from above” of Social Democracy and Stalinism.

In an era when a revolutionary was thought of as a guerilla fighter with an AK-47 fighting in the jungles of a distant country, support for such “classical” Marxism was certainly going against the current.

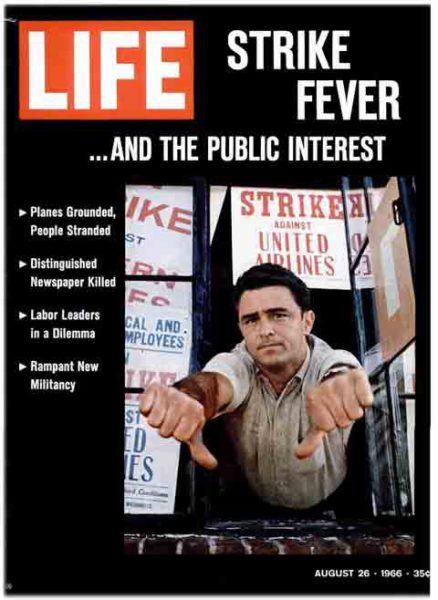

The TTWC authors called themselves “radicals who support the concept of Black Power” but looked at the question of power and liberation from a different angle. “We, socialists and radicals, look to the rank-and-file workers as our potential allies,” they declared. A powerful example of this potential was the machinists’ strike that crippled passenger airline travel across the United States.

The TTWC authors wrote, “For those who have doubts,” about the willingness of workers to struggle for progressive ends, take a look at the recent airline strike of the International Association of Machinists (IAM). Not only did the strike hold out against the threats of a congressional injunction; but the rank and file had the guts to flatly reject a settlement pushed by President Johnson himself. A interesting political side light is that four IAM locals have recently called for a break with the Democratic Party and the formation of a third party.”

They emphasized, “Keep in mind that this was a struggle that occurred without the benefit of radical organizers; it was, in many ways, a spontaneous act.”

Relating to the labor movement but almost exclusively as outside supporters had its limits, according to the ISC authors:

“We believe that supporting strikes and organizing workers for independent unions or even existing unions is good, but it is not enough. Furthermore, there is a sort of hierarchy of value in these activities. Working on a union staff may provide good experience for a student or ex-student, but it cannot be a place from which political work can be done.”

They wanted to make clear to the delegates that they weren’t denigrating union organizing “but that you cannot do serious radical political work from that position.”

The TTWC authors argued, “SDS, as an organization, and SDS members should orient towards the working class as the decisive social sector in bringing about the transformation of American society.”

This was serious work that the TTWC authors didn’t want “romanticized” or seen as a “moral virtue” for those willing to organize in the industrial workplaces.

The setting was very different in 1966 for debating a rank and file perspective than today. Unions were major institutions—‘Big Labor,’ as it was called then—in U.S. economic and political life. The rank and file rebellion was causing major political concern and a crisis for the entrenched leaders of the U.S. trade unions.

The front cover of Life magazine captured the setting well with a headline of “Strike Fever” with a picture of a striker voting no with two thumbs and a side bar decrying “Labor Leaders in Dilemma” and “Rampant New Militancy.”

Despite the favorable circumstances, TTWC co-author Kim Moody told me, “Our position paper received little attention as the main underlying business was the transition from the ‘old guard’ leadership to the new ‘generation’ that was flooding SDS. We had hoped to influence some of the younger people entering SDS. “Toward the Working Class” actually appeared in New Left Notes in the Sept 9 issue –after the convention.”

It lost out to Carl Davidson’s proposal for a new student syndicalist movement that emphasized SDS’s focus primarily on the campuses. TTWC has almost been entirely ignored by historians of the New Left with the notable exception of Peter Levy’s “The New Left and Labor in the 1960s”.

While it was wrong to expect SDS to completely reorient itself in such a short period of time—there was still plenty of reason for a student movement to grow especially with the burgeoning antiwar movement on the campuses that SDS was in the thick of— yet, one cannot help but look back and feel that there was a lost opportunity here.

When the various communist and socialist organizations (that emerged from the New Left in the late 1960s and early 1970s) made a turn towards organizing in the industrial working class during the 1970s, was it too late?

During the last four decades the gut-wrenching changes to the industrial working class significantly weakened, if not destroyed, the once mighty industrial unions in many parts of the U.S. industrial economy. The left that attempted to build in the industrial unions were marginalized, if not destroyed by these changes.

However, one of the offspring of the political work of the International Socialists was a reform movement within the Teamsters in the 1970’s. Teamsters for Democratic Union (TDU) played a major role in the election of the Teamsters first reform president in 1991, the UPS strike of 1997, and the recent near-defeat of incumbent Teamster general president James P. Hoffa.

Today, once again a new generation of radicals is discussing the question of oppression, power and radical change. How do we have a similar debate today that SDS had in 1966 but with a broader audience?

The absence of even a small left in the industrial unions in the upper Midwest is part of the reason that Trump triumphed in the Electoral College. The popularity of Bernie Sanders among industrial workers and the victories of Zuckerman’s reform campaign in the Midwest, I think demonstrates this.

As I wrote in Jacobin of last December:

“For the broader labor movement and left in the United States, the Teamsters’ elections should counter some of the impact of Trump’s victory and with it much inane discussion of the American working class. A befuddled Paul Krugman wrote in his most recent column, “To be honest, I don’t fully understand this resentment [that elected Trump].” Yet the states that gave Trump the presidency also voted overwhelmingly to toss out Hoffa.”

Today the modern industrial economy revolves around the logistics industry. As Kim Moody wrote last year:

“Eighty-five percent of the nearly three-and-a-half million workers employed in logistics in the United States are located in large metropolitan areas–inadvertently recreating huge concentrations of workers in many of those areas that were supposed to be “emptied” of industrial workers. There are about 60 such “clusters” in the United States, but it is the major sites in Los Angeles, Chicago, and New York-New Jersey, each of which employs at least 100,000 workers and others such as UPS’s Louisville “Worldport” and FedEx’s Memphis cluster that exemplify the trend.”

If Amazon makes good on its promise, by 2018 it will add another 100,000 workers to its U.S. workforce bringing the total number to over 200,000. It will be one of the largest employers in the United States and one of the largest non-union employers. A new generation socialist activists have to learn how to organize these workplaces.

A New Left is emerging in the United States. The millions who participated in the huge demonstrations that greeted Trump’s first weeks in office is the most visible and spectacular sign of this. The rapid growth of the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) is one of the most visible signs of this along with widespread interest in general socialist ideas, history, and organizations. Moshe Marvit and Leo Gertner in the Washington Post capture the spirit of rebellion at the moment and advocate its spread to the workplace, “Though often overlooked in America, the workplace can be as much a focal point of resistance and protest as the streets.”

However, we shouldn’t underestimate the obstacles we face. We are challenged with the daunting task of creating a new socialist movement and a new industrial union movement virtually from scratch.

While I believe that the politics of “socialism from below” will be the most important political contribution to the formation of next New Left, we need to bury the legacy of Stalinism once and for all. I would argue that we need to begin modest campaigns advocating socialist ideas and organizing in the logistics industry in select cities.

Such an effort must begin modestly but they must begin. Trump’s triumph in the Electoral College demonstrates the peril of an absence of socialism in the industrial working class.

Former SDS Chicago organizer and ISC member Wayne Heimbach warns us about lost opportunities. “In 1966 it was the ISC people who had the high ground in SDS on working class politics. Within a year or two this would transfer over to Progressive Labor and its Worker/Student Alliance,” he told me. PL’s cartoonish and thuggish politics were one brand of the many varieties of Stalinism that came to dominate and wreck the post-1960s left in the United States.

Looking back on the debates at the 1966 SDS convention SDS leader Jeff Shero told Kirkpatrick Sale, “We wanted to build an American left, and nothing less than that”. The question today is the same, but I would add, What kind of American left do we want to build?

After a Trump Month, a Few Thoughts…

By Mike Miller

The outpouring of anger and frustration in the present period is understandable, and necessary. It provides a sense of solidarity that, one hopes, will help people for the long march through the institutions that lies ahead.

The success of the Right is not new, nor is it particularly American. We need to understand why that is. To blame it on xenophobia, racism, sexism or any other “ism” is insufficient. Why are people voting against their economic interests? Why are people voting against government programs that often serve them, their neighbors and their children? Why are people enthralled with the visible display of wealth rather than considering it morally repugnant?