How Can Workers Organize Against Capital Today?

By Benjamin Y. Fong

John Womack’s labor strategy is about workers finding the capacity to “wound capital to make it yield anything.” But the massive challenge in today’s deindustrialized economy is locating where that leverage actually lies.

Labor Power and Strategy, the new book edited by Peter Olney and Glenn Perušek, officially aims to provide “rational, radical, experience-based perspectives that help target and run smart, strategic, effective campaigns in the working class.” But by the end of it, it is difficult to avoid the sneaking suspicion that Olney and Perušek have a different goal: to make clear just how far organized labor is from having a strategic conversation about its present impasse.

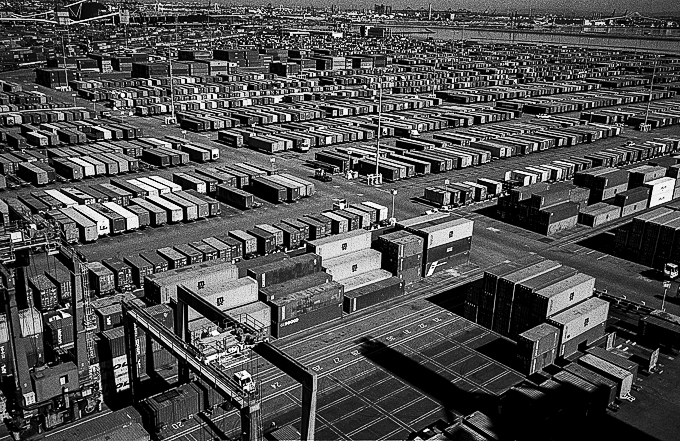

The book is organized around an interview with economist and historian John Womack about the twin needs for an analysis of the weak points (or “choke points”) in contemporary industrial technologies and for the labor movement to exploit that analysis to cause disruption and gain leverage. Womack supports the struggles of all workers to organize for better conditions, but he also believes the labor movement should focus not on raising the floor for the “most oppressed” groups of workers but rather on workers and industries where it is possible to gain the kind of leverage to bring the capitalist class to heel. In his words, labor “needs to know where the crucial industrial and technical connections are, the junctions, the intersections in space and time, to see how much workers in supply or transformation can interrupt, disrupt, where and when in their struggles they can stop the most capitalist expropriation of surplus value.” To do this effectively, he urges continual network analysis, or “grubbing,” to reveal the vulnerable seams in the fabric of modern supply chains — the places where ports and rail and warehouses meet, and thus where production and distribution can be effectively blocked.

Union power before the 1930s was drawn mainly from skill, or certain groups of workers’ specific position within the economy and the leverage it offered. The American Federation of Labor was thus a self-limiting organization at the time, and it took the challenge of the Committee of Industrial Organizations (CIO) to overcome its commitment to that limitation. In the common understanding, instead of leverage through skill, the CIO sought and gained leverage at the “point of production.” For Womack, this idea was “a mistake then, but now ignorantly, thoughtlessly used.”

At large in a nationally defined economy, in any industry, in any plant where there are technical divisions of labor there’s not one point of production, but several, multiple points, connected, coordinated in place and time to make production, not a point, but as Dunlop [John Dunlop, whose Industrial Relations Systems heavily influenced Womack’s views] called it a “web,” or as we had better call it now for the sake of analysis, a network.

For Womack, key CIO organizers like Wyndham Mortimer understood well that there was no single “point” at which power could be gained. The CIO knew it had to figure out where things connect, “where they’re materially weakest, maybe politically, legally, commercially, culturally strong, protected, defended, but technically weakest,” and the challenge today is to do the same for a deindustrialized, logistical economy.

Womack is engaging and nimble in conversation, which makes the interview a fun read, but his basic points are often ones that the labor left of previous generations would have found straightforward and uncontroversial. Here’s Womack discussing leverage:

No matter what workers are mad about, unhappy about, indignant about, feel abused about, it doesn’t matter until they can actually get real leverage over production, the leverage to make their struggle effective. You don’t get this leverage just by feelings. You get it by holding the power to cut off the capitalists’ revenue. And without that material power your struggle won’t get you very far for long.

To which I imagine leaders of the CIO responding, “Yeah, obviously.”

The interview is then followed by ten responses from leading lights of the labor movement that make Womack’s claims seem anything but obvious. Rather than think alongside Womack or extend his claims in various directions, most of the responses take issue with the priority he accords to “technically strategic power” and the kinds of workers who are in a position to wield it.

Katy Fox-Hodess, Jack Metzgar, Joel Ochoa, and Melissa Shetler all take exception in different ways to Womack’s prioritization of strategic power over the “forms of power that accrue to workers as a result of their collective organization in trade unions, works councils, and the like” — in sociologist Erik Olin Wright’s terms, his emphasis on “structural power” over “associational power.” Fox-Hodess asserts that “strategic power (or structural power) is deeply rooted in associational power”; Metzgar that Womack misses “the impracticality of focusing strictly on strategic positions that can upend capitalist power relations.” All four agree that the labor movement cannot in any way deprioritize the cultivation of associational power.

Bill Fletcher Jr and Jane McAlevey lodge a related but slightly different complaint: that Womack’s focus on strategic industries does a disservice to workers in supposedly nonstrategic industries. Fletcher, in a contribution tellingly titled “Should Spartacus Have Organized the Roman Citizenry Rather Than the Slaves?,” believes those sectors of society that are already in struggle must be supported, rather than the ones that are ostensibly more strategic. McAlevey meanwhile asserts that only “the gendered bias that power is exercised by mostly men in the dated conception of the male-dominant private sector” keeps us focused on logistics, when it is in fact “women, often if not mostly women of color” in health care and education who have shown themselves most capable of “exercising strategic power that deftly harnesses economic and social power that can’t easily be pulled apart.”

Regarding the first criticism, that Womack unjustly prioritizes structural over associational power, it should be said first that he in no way practically deprioritizes associational power. Without collective organization and the exercise of associational power at the necessary moments, he asserts, workers simply are not going to be able to take advantage of any disruptive position they hold. Metzgar points to the example of the failed 1919 steel strike, where workers “had insufficient associational power to take advantage of their structural power,” to show that you cannot have one without the other, but here he’s knocking on an open door. Womack is clear that workers cannot effectively use strategic power without associational power.

The latter should nonetheless be considered secondary, in Womack’s view, because true solidarity flows from an understanding of strategic power. Most workers, most of the time, are not going to put their own material interest on the line just to be good comrades. A culture of solidarity can and should be built within any union, but that culture is only going to attract so many; if they don’t think they can win by seizing the necessary leverage over the company, most workers are not going to engage in the requisite struggle, and if they don’t see their technical and industrial dependence on other workers, they are not going to be convinced of the urgent need for solidarity. As Womack says,

You can’t count on ding-dong lectures or jingles or pamphlets, “I’m my brother’s, I’m my sister’s keeper.” Sweet idea, but within hours at work you’ve got dirty jokes about it. But once you see the technical connections of one job with another, who can foul or ruin or stop whose work, who can in fact endanger whom, high and low, back and forth, like a team sport, a firefighter company, the armed forces, I think you get real attention to how much mutual dependence means, technical interdependence, the practice value and real advantage of comradeship at work.

The bigger objection raised by Womack’s critics, however, is that his technical emphasis privileges some groups of workers over others. Indeed, underlying the objection to his prioritization of structural over associational power is a worry that workers without the former are just being written off. Thus Metzgar’s claim that workers “cannot be counseled to simply give up because they are not strategic” and Ochoa’s hope that “organized labor can create momentum by organizing in nonstrategic sectors.”

Once again, the critics are tackling a straw man: at no point does Womack say that “nonstrategic” workers simply shouldn’t organize. When he asserts that the focus should not be on the “most oppressed” workers but rather on workers’ ability to disrupt production and distribution, his point is twofold.

First, in any economic situation, there are always going to be industries that, if left unorganized, will hurt organized labor as a whole. John L. Lewis did not start the CIO because he privileged rubber workers over carpenters; he did it because he understood that organized labor would never exert any influence in society until General Motors, Goodyear, U.S. Steel, and the other major corporations of the period came to the table. The situation is similar today with Amazon, Walmart, Target, etc.: until these companies are organized, labor as a whole is going to suffer.

Second, it is less that Womack urges the narrow organization of strategic workers than that he wants workers’ power as a whole to be more strategically exercised. Sometimes this means seeing some workers as more proximate to the nodes of disruption than others, but mainly it means viewing all workers’ power through the lens of their capacity for that disruption. This is where his central challenge to the labor movement lies, and what I want to focus on for the remainder of this review. Curiously, the challenge is relatively unexplored by his interlocutors.

Dan DiMaggio, Carey Dall, Rand Wilson, and Gene Bruskin provide more sympathetic reads of Womack than the other six respondents, but it is not clear that even these readers really want to go where he is pointing. DiMaggio sees “the bigger context for thinking about Womack’s points [to be] that any revival of the US labor movement will require the revival of the strike,” though withholding labor per se is hardly Womack’s focus. Wilson thinks “workers are almost always the most knowledgeable source of information about who is in the best position to disrupt the production processes or services and where management’s weaknesses lie,” though Womack is at pains to show that the highly complex distributional flows of the present require something like a labor institute of industrial technology to understand them.

In many ways, the essential reticence to accept Womack’s basic orientation is a function of the fact that labor and the Left are still both focused on the need, in Wilson’s words, “to realize labor’s potential power in the workplace.” This is a fine position to hold if power really flows through the workplace, as it did when there were tremendous amounts of fixed capital invested in gigantic factories. But today, points of leverage are very often outside workplaces, at those distributional nodes far from the shop floor, between companies, workers, and union jurisdictions.

One might say then that, for the labor left, Womack offends the basic imperative to descend into the hidden abode of production. For him, it is not the workplace as such that is important but the kinds of connections that the workplace makes possible. Some of those connections will be in the workplace, but many will not.

Wherever you put things together, there’s a seam or a zipper or a hub or a joint or a node or a link, the more technologies together, the more links, the places where it’s not integral. It is parts put together, and where the parts go together, like at a dock, at a warehouse, between the trucks and the inside, between transformers and servers and coolers, there can be a bottleneck, a choke point.

“… is it possible to mobilize workers not simply to band together and withhold their labor but to seize these choke points in coordinated action?“

Womack challenges jurisdictional boundaries (he even suggests at one point the creation of a “US Transport and General Workers’ Union” combining the ILWU, ILA, IBT, and IAM), but more generally he questions the very basics of unions’ organizing orientation (insofar as they still organize). To be very simple about it, we might see Womack as wanting to replace the model of the strike with that of the blockade. Unions, of course, are not unpracticed in the latter, but it is not the organizing fulcrum that the former is typically made out to be.

Once we get here, a whole set of fascinating questions emerge: first and foremost, if many (though not all) of the strategic disruption points have moved outside of the workplace, is it possible to mobilize workers not simply to band together and withhold their labor but to seize these choke points in coordinated action? This would mean, for instance, turning one’s attention away from organizing particular stores to getting smaller cadres of employees to occupy key distributional nodes and getting masses of other workers to support them. Right off the bat, we can see that the distinction between supposedly strategic and nonstrategic workers begins to fade: longshoremen and rail engineers are not necessarily the only ones with access to the seams in industrial technologies.

Still, they’d need to be supported by research departments that have up-to-date and sophisticated analyses of particular supply chains. Is the labor movement up for such a task? What would it need to approximate something like Womack’s proposed labor institute of industrial technology? Somehow the “Freedom Convoy” found the one bridge where 25 percent of all trade between the United States and Canada is conducted. Why wasn’t it the labor movement that took advantage of this situation?

Then there’s the question of how to support workers at such critical junctures, when historically company and state violence have been exerted. If smartphones are recording every second of a blockade, will that prevent bloodshed? What does community support look like at warehousing sites far from any affected community? Consumer boycotts? Can they be timed effectively? Would such occupations only work if multiple nodes in a supply chain were seized?

There are also further questions around internal organizing that Dall raises in his helpful response. For Dall, activating already unionized workers at ports and in rail can help set the conditions for organizing other workers: “To organize Amazon workers, we must first internally organize union transportation workers whose labor on the seams enables Amazon to get cargo of Asian origin to their hellish warehouses and finally to the consumer’s door.” In the case of rail and airline workers, there is a particular law, the Railway Labor Act, that protects these transportation workers in some ways but heavily incentivizes them not to disrupt things in others. What are those ways? How can these unions be won over to the idea that they might need to break the law, or how can particular workers be convinced not to follow their unions’ dictates?

Finally, the basics of breaking the law — how, when, where, and why to do it — must be foregrounded in any execution of a Womackian vision. From roughly the 1932 Norris-LaGuardia Act until the 1947 Taft-Hartley Act, labor had access to tools that are now off limits: recognition strikes, sit-downs, secondary boycotts. The postwar compromise was predicated on tolerating collective bargaining, provided those tools were put down for good. Experimenting with disruptive tactics again is likely to bring about forms of repression the likes of which we have not seen for a few generations. The possible benefits are enormous, but any action for which people might be put under the jail must obviously be undertaken with extreme caution.

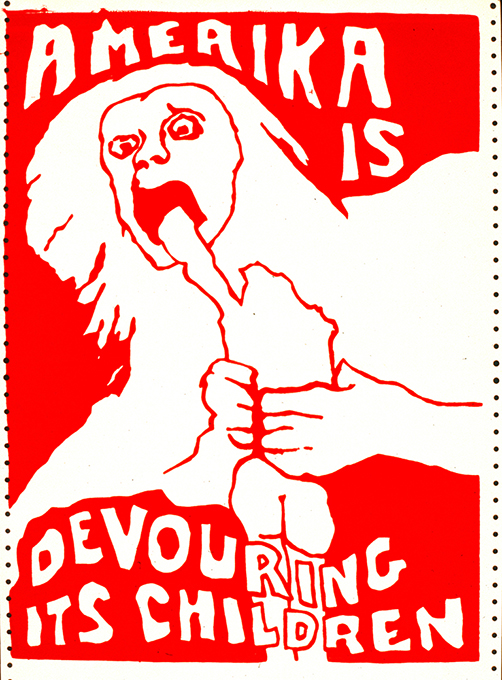

At present, the Left is rent between those who emphasize the importance of disruption, rioting, sabotage, etc., and those who encourage us to stay the democratic course. The more anarchistic emphasis on dramatic disruption can often be fantastical, but given the constraints of modern labor law, where many ways of gaining leverage are straightforwardly illegal, it does seem necessary to start some conversation about the forms of strategic illegality that labor activists might want to take up. Womack allows us to begin to broach this question in ways that move beyond the dichotomy of blowing it all up versus working within the present institutions.

These questions, difficult and speculative as they can be, all follow from Womack’s analysis, and it’s notable they receive such little discussion in the responses. I have tried to get at the substantive reason for avoidance — that Womack moves us away from thinking about workplace organizing in the typical ways — but perhaps there are more personal and institutional reasons there as well. Some of what Womack articulates bears a resemblance to the vision behind SEIU’s “comprehensive campaigns,” which produced some impressive wins but fell far short of their stated goals. Some on the labor left still bristle at the “smart” strategizing of SEIU luminaries, and maybe Womack’s speculative hipshots are too reminiscent of former president Andy Stern’s thought.

But the stakes for labor today are too high for past grudges to lead to a dismissal of the need for broad strategic reconsiderations. At root, Womack’s labor philosophy is quite basic: “You have to wound capital to make it yield anything. And you wound it painfully, grabbing its attention, when you take direct material action to stop its production, cut its profit.” But how to make good on this idea, with a stolid labor movement in a deindustrialized, logistical economy, is a tremendously complicated matter. Operationalizing Womack would take not just a set of short responses but a research team with real resources. I cannot speak at present to the feasibility of many of Womack’s proposals or the possibilities latent in his thinking, but those proposals and possibilities should at least be recognized for what they are: a massive challenge to the usual ways we think about labor organizing.

What exactly would it take to wound capital today? Womack doesn’t provide all the answers, but he should at the very least get us thinking outside the typical boxes.

…

First published in Catalyst

Labor Power and Strategy is available from PM Press

The Teamster Connection: Apartheid Israel and the IBT

By Joe Allen

At the December 17 monthly membership of Teamsters Local 705 in Chicago, a resolution was put forward by several members of the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) calling for a ceasefire in Gaza. I was told by several people present that while the resolution was voted down decisively, it was not overwhelming. They estimated on a voice vote that around 65% to 70% percent voted against it, while 35% to 40% voted for it.

While I was heartened to see that a sizable minority of the meeting was for a ceasefire, I was also saddened that my old local union couldn’t a make the smallest gesture towards opposing genocide. In sharp contrast, two decades ago, Teamsters 705 pioneered labor opposition to the Iraq War, when it passed a resolution condemning President George W. Bush’s war drive. I’ve written about this recently here.

The Teamsters 705 vote followed the tabling of a ceasefire resolution at the Teamsters for a Democratic (TDU) convention in early November, and many activists are wondering what comes next for Palestine solidarity in the Teamsters? Israel’s ongoing genocidal war shows no sign of abating. Opposition to the U.S. backed war is growing but also faces determined resistance from the Democratic and Republican Party establishments and slander from the media.

Many U.S. unions have longstanding ties to the State of Israel. What is the Teamster connection?

Jimmy Hoffa: “Critical support to a struggling Jewish state.”

One of the least known aspects of Teamster history is its long relationship with the State of Israel, right from its very origins. Something I was surprised to discover until I started looking into it over the past few weeks. During a 2008 fundraiser held in Washington, D.C. organized by the American Friends of the Yitzhak Rabin Center, the Jewish Telegraphic Agency (JTA) reported:

“A little-known chapter in the life of the legendary Teamsters leader [Jimmy Hoffa] is about to come to light in a tribute planned for Feb. 13, when the American Friends of the Yitzhak Rabin Center will have a commemorative dinner. Former President Bill Clinton will address the gathering.”

What was this little known chapter? General President James P. Hoffa, Jr, son of Jimmy, told the JTA:

“They were not only fighting for working people but fighting for independence,” adding that his father was influenced by Israel’s struggle against the British and the Arabs. “He became involved in that and in facilitating arms for the struggle.”

The JTA straightforwardly commented, “Facilitating” in this case is a euphemism for “smuggling.” Stuart Davidson, of the American Friends of the Yitzhak Rabin Center, said that Jimmy Hoffa and the Teamsters “provided critical support to a struggling Jewish state rising from the ashes of the Holocaust.”

Hoffa in the late 1940s was president of Local 299 in Detroit, as well as a prominent Michigan Teamster leader well-known for his political ambitions. He was still a decade away from becoming the union’s national leader, and two decades away from going to federal prison. Yet, he already had extensive ties to organized crime in Detroit, that were well documented in the 1950s by the Senate Rackets Committee, and later popularized by Dan Moldea for a younger generation of Teamster activists in his classic book The Hoffa Wars published in the late 1970s.

It was these connections to organized crime that most likely explain how Hoffa smuggled American weapons illegally into the hands of Zionist militias and nascent Israeli military. If these claims are true, they are disturbing because they mean that Hoffa smuggled weapons to Zionist militias involved in ethnic cleansingagainst Palestinians, during what Palestinians’ call the “Nakba,” meaning catastrophe. Over 750,000 Palestinians were driven from their ancestral homes during this period of time.

Jimmy Hoffa also helped burnish Israel’s image internationally as a caring society during the 1950s, while Palestinians were struggling for their very existence in Gaza and other territories. The JTA reported:

“In 1955, Hoffa held a dinner that raised $300,000 – a phenomenal sum at the time – for an orphanage in Ein Kerem, a Jerusalem suburb. He visited Israel in 1956 to dedicate the orphanage; a year later he became Teamsters president.”

Hoffa visited the orphanage that during his 1956 visit to Israel he had his picture taken with then Minister of Labor and soon to be appointed Foreign Minister of Israel Gold Meier. Meir was a hardened Labor Zionist, who was later quoted as saying, “They [Palestinians] did not exist.” He also met with Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion, considered one of the “Founding Fathers” of Israel.

The Rabin Center: “Breaking the bones of Palestinians”

Hoffa Senior’s contributions to the creation of the Zionist state were honored in Washington by the American Friends of the Yitzhak Rabin Center. Soon after the election of Barack Obama to the presidency, Teamster General President James P. Hoffa traveled to Israel. According to the Jerusalem Post:

The Younger Hoffa raised $2.5 million for the Yitzhak Rabin Center. During his visit, a room at the center will be dedicated to the Teamsters. Hoffa said he had been looking for a way to strengthen his ties to Israel, and began to work for the Rabin Center on the advice of friends. During his time here, he plans to visit the Histadrut-run Alumim Youth Village in Kfar Saba, whose original Jerusalem facility was built by a $300,000 donation from his father.

The Rabin Center, created by an act of the Knesset, the Israeli parliament, is a favorite of American trade union leaders, including the Teamsters. What makes it possible for U.S. trade union leaders to so enthusiastically embrace the Rabin Center? Along with their general subservience to U.S. foreign policy, it also has to do the with Rabin’s affiliation with the Israeli Labor Party and the thinning gloss of “Labor Zionism” covering some of Israel’s institutions, notably the Histadrut, Israelis racist trade union federation.

John T. Coli, the former head of the Teamsters in Chicago, soon to be released from federal prison, led one union delegation to the Rabin Center in 2013, where he enthused:

“There wasn’t a nation here. Now it’s totally different. [Tel Aviv] is a modern city. People have access to health care, to education. That’s what we want to build everywhere.”

Add to this Rabin’s image as a fallen hero for peace. He was assassinated in 1995 following the signing of the now discredited Oslo Accords. J. David Cox, the president of American Federation of Government Employees, who led another union delegation in 2013, couldn’t say enough about Rabin the peace maker, his “commitment to peace in not just Israel but the world is amazing.”

However, the image and reality of Rabin the peacemaker are two different things. Israeli historian Ilan Pappé, in The Ethnic Cleansing Of Palestine, wrote of Rabin’s military and political career:

“Yitzhak Rabin who, as a young officer, had taken an active part in the 1948 cleansing [Nakba] but who had now been elected [1992] as prime minister on a platform that promised the resumption of the peace effort. Rabin’s death came too soon for anyone to assess how much he had really changed from his 1948 days; as recently as 1987, as minister of defense, he had ordered his troops to break the bones of Palestinians who confronted his tanks with stones in the first intifada ; he had deported hundreds of Palestinians as prime minister prior to the Oslo agreement, and he had also pushed for the 1994 Oslo B agreement that effectively caged the Palestinians in the West Bank into several Bantustans.”

Bantustans are a reference to one of the methods that the old Apartheid regime in South Africa used to divide and disenfranchise the majority Black population. As one online South Africa history website puts it succinctly, “Bantustans were established for the permanent removal of the Black population in White South Africa.” This was a model for the type of “peace” that Rabin offered the Palestinians.

The Times of Israel reported in 2013 that, “Members of U.S. labor unions raised $1.4 million for the Yitzhak Rabin Center in Tel Aviv last year, 45 percent of the center’s total 2012 fundraising. Since 2005, American unions have raised $12 million for the center.” It also reported, “Cox’s group met with Arab-Israeli union members, but did not meet with Palestinians despite visiting religious sites in Bethlehem, a Palestinian city in the West Bank. Coli’s delegation did not have any meetings with Palestinians or Arab-Israelis.”

A dinner in honor of Coli raised $700,000 for the Rabin Center in 2012, alone. He returned to Israel in 2015, with injury lawyer Michael Goldberg, who referred to “as a guest of the Teamsters union.” Goldberg’s firm donated a $750,00 to the Rabin Center. It should be noted that John Coli was sentenced to federal prison for extortion in 2019, and in the following year, J. David Cox resigned from office charged with misuse of unions funds and sexual harassment.

Teamster General President James P. Hoffa apparently screened a showing of a film made by Yitzhak Rabin’s daughter Dalia Rabin-Pelossof about her father to the union’s General Executive Board . He told the JTA that , “People were visibly moved by the story and the connection of the Teamsters” to the Zionist movement. At the end of the day, Hoffa’s gun running to Zionist militias may turn out to be exaggerated boasts from the Hoffa family or flattery from Israeli officials eager to curry favor, but Jimmy Hoffa established a connection that has continued for decades.

Israel Bonds: “Great PR value”

The purchase of Israel bonds have been an important method for financing construction projects, and more importantly demonstrating political support for the State of Israel. As the Israel Bonds website reports:

For 72 years, Israel Bonds has generated $50 billion worldwide. Additionally, Israel Bonds has doubled its annual global bond sales for 2023, surpassing $2 billion. Israel bonds are a smart investment, with strong rates, and are meaningful investments, serving as a symbolic connection with Israel and the people of Israel for Jews worldwide.

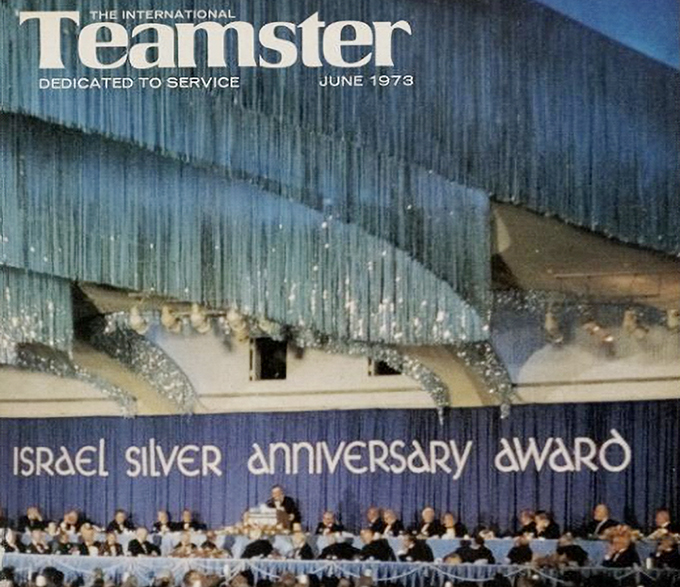

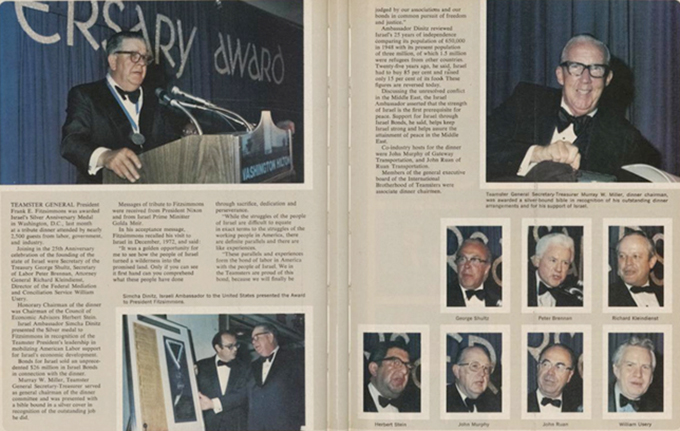

The Teamsters saw a big public relations value for themselves with purchases and selling Israel bonds beginning in the 1970s. In May 1973, then Teamster General President Frank Fitzsimmons accepted the 25th Anniversary Medal of the State of Israel on behalf of the Teamsters. The Black tie event in Washington, D.C. drew members of President Richard Nixon’s cabinet and the Israeli Ambassador to the United States, Simcha Dinitz, who presented the award to Fitzsimmons. Messages of tribute from Nixon and Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir to Frank Fitzsimmons were read.

The following month, Fitzsimmons boasted in his column in the June 1973 Teamster magazine:

“In conjunction with the dinner, $26 million in Israeli Bonds were sold. The money is an Investment in Israel’s ability to defend its freedom, and it is an investment that provides a secure return in interest paid on the bonds.”

Jackie Presser, the mobbed-up leader of the Cleveland Teamsters and future General President, was placed in charge of a public relations campaign by Teamsters to combat its negative image in the media with Israel Bonds. Steve Brill in his classic book The Teamsters recounted a 1975 dinner in Cleveland, Ohio,

“honoring Jackie Presser for his extraordinary work in selling Israel bonds. Supporting Israel had been a favorite, if not the only, Teamsters public relation strategy since the night in 1956 when [St. Louis Teamster leader] Harold Gibbons convinced Hoffa that $265,000 collected at a testimonial dinner should be donated for the construction of a children’s home in Israel. Since then [Brill’s book was published in 1978] the Teamsters have been the biggest union buyers of Israel bonds. By 1977, they had bought $26,000,000 worth out of a total of American union purchases of $100,000,000.”

Meyer Steinglass, an Israel Bonds spokesperson, said, the bonds had “great PR value…these people [the Teamsters] are looking for respectability and this is one way to get it…And, in this union the guys at the top can make the locals buy the bonds. I mean, you know what they say, ‘You can find yourself under a truck if you don’t obey.’”

All of this enhanced the reputation of Jackie Presser. “Just about everyone who was anyone in Cleveland politics or business turned out,” Brill wrote. “At the dinner, Israeli Ambassador Simcha Dinitz inducted the guest of honor into the Prime Minister’s Club, a group made up of people who personally (or in Presser’s case, through his union) bought more than $25,000 worth of bonds.” At one point, the Teamsters owned more than a quarter of all Israel bonds held by U.S. unions.

Today

There is a lot we don’t know about the current relationship between the Teamsters and the State of Israel. Educating the Teamster membership on the long relationship between the U.S. labor movement, including the Teamsters, and Israel will be vitally important. Researching the financial investments that the Teamsters and its many pension funds may hold in U.S. based corporations and State of Israel Bonds that support Israeli Apartheid will also be crucial. There will be further opportunities to put forward for ceasefire resolutions in local union meetings in the months to come across the country.

…

This piece originally ran in Counter Punch

Senate Hearings On the U.S. and Israel

By Mike Miller

Among major nations, only the U.S. and Israel voted against a UN General Assembly vote criticizing Israel’s action in Gaza. The U.S. is alone among major nations in its one-sided actual (as distinct from rhetorical) support for Israel, no matter what it does. U.S. policy now threatens regional and perhaps wider war. In some circles in the U.S. now, to be critical of Israel is to be anti-Semitic. This charge, once enough to silence many critics, is losing its impact.

AIPAC is gearing up its formidable fundraising apparatus to raise money for primary challengers to Democrats who are critical of Israel’s present war against Hamas and its unwillingness to come to terms with Palestine. These primaries will be an important test of whether there is a shift in American public opinion on this conflict—both viewpoint and salience to the voter of the issue.

On October 27, 2023, the Assembly overwhelmingly adopted a resolution offered by an Arab group of nations. The 193-member world body adopted the resolution by a vote of 120-14 with 45 abstentions after rejecting a Canadian amendment backed by the United States to unequivocally condemn the Oct. 7 “terrorist attacks” by Hamas and demand the immediate release of hostages taken by Hamas.

Then on December 12, the UN General Assembly voted overwhelmingly to demand a humanitarian cease-fire in Gaza.

The U.S. had to veto the UN Security Council resolution condemning all violence against civilians in the Israel-Hamas war. This is not the first time our country has used its veto power to support Israel.

What is now different is that the almost-automatic favoring of Israel in the U.S. is shaken. Remembering the Holocaust and supporting Israel as a homeland for the Jewish people is not the same as uncritical support for Israel no matter what it does. Netanyahu’s disproportionate violence in response to the horrible Hamas attack of October 7 is leading to second thoughts on the part of many Americans.

Only the U.S. is in a position to effectively put pressure on Israel’s policymakers by placing a hold on arms funding and shipments until a cease-fire takes place. Following that, the U.S., along with others, must then play an honest broker role in bringing about negotiations between the parties that ends in a solution supported by each.

The question is whether those supporting a just settlement to the conflict between Israel and Palestine will develop a focus on what U.S. foreign policy toward that conflict will be, or will continue to argue about the attack of October 7 and Israel’s response to it. That is a no-win argument. People on either side of it can endlessly draw upon history going back to pre-Christian times to support Israel or Palestine.

Precedent: Vietnam Hearings. January 24, 1966

Here’s the Official Senate Report on the periodic Fulbright hearings on the Vietnam War.

Early in 1966, a journalist who had interviewed more than 200 U.S. troops in Vietnam wrote to Senate Foreign Relations Committee chairman J. William Fulbright. The reporter explained, “The war is not going well. The situation is worse than reported in the press and worse, I believe, than indicated in intelligence reports.” A recent military buildup seemed to be having little effect. One officer told the reporter, “If there is a God, and he is very kind to us, and given a million men, and five years, and a miracle in making the South Vietnamese people like us, we stand an outside chance—of a stalemate.”

On January 24, 1966, Secretary of State Dean Rusk appeared before a closed hearing of Fulbright’s committee. His assessment: “If the U.S. and its allies remained firm, the communists would eventually give up in Vietnam.” Rusk’s testimony convinced Fulbright that the administration of President Lyndon Johnson was blinded by its “anticommunist assumptions.”

Attempting to forestall a buildup of American forces, Fulbright launched a high-profile series of widely televised public “educational” hearings in February 1966. The all-star cast of witnesses included retired generals and respected foreign policy analyst George Kennan.

Kennan advised that the United States withdraw “as soon as this could be done without inordinate damage to our prestige or stability in the area” to avoid risking war with China. His testimony prompted an angry President Johnson to order FBI director J. Edgar Hoover to investigate whether Fulbright was “either a communist agent or a dupe of the communists.”

Conducted in the Senate Caucus Room, the hearings reached their most dramatic phase when Secretary Rusk and General Maxwell Taylor arrived to lay out the administration’s case. Fulbright shifted from his earlier role as a benign questioner of supportive witnesses to a grim prosecutor, his dark glasses set resolutely against the glare of television lights.

The February hearings did not immediately erode Senate support for Johnson’s war policies. They did, however, begin a significant shift in public opinion. In the four weeks that spanned the hearings, the president’s ratings for handling the war dropped from 63 percent to 49 percent. The testimony of George Kennan and other establishment figures had made it respectable to question the war.

Fulbright’s biographer concludes that the hearings “opened a psychological door for the great American middle class. It was Fulbright’s ability to relate to this group, as well as his capacity for building bridges to conservative Senate opponents of the war, such as Richard Russell, that would make him important to the antiwar movement.

Now

Now is the time for a broadly-based group of labor, professional, religious, political, business and civic leaders, joined by notables, scholars, athletes and celebrities, to call for hearings on the efficacy of American foreign policy. A statement they sign could read something like this:

The United States Senate should hold hearings on the efficacy of United States post-Cold War and post-9/11 foreign policy. Having defeated the Communist bloc and its allies in the Cold war, U.S. political leaders promised an era of peace, freedom and economic development. We have seen little to fulfill that promise.

The United States is the single-most militarily powerful nation in the world. Our war and peace policy may outweigh in its consequences the policies of the rest of the world put together. It is time for a public review, discussion and debate on those policies.

We, the undersigned, call upon the US Senate to initiate such hearings, asking the question, “Is It time for a New American Foreign Policy?”

The first round of hearings could be on Israel-Hamas-Palestine. But the broader question now has an opportunity to be raised as left, right and center critics of our role in both Ukraine and Palestine, are now challenging the post-9/11 foreign policy consensus.

…

Olney Odyssey #20

By Peter Olney

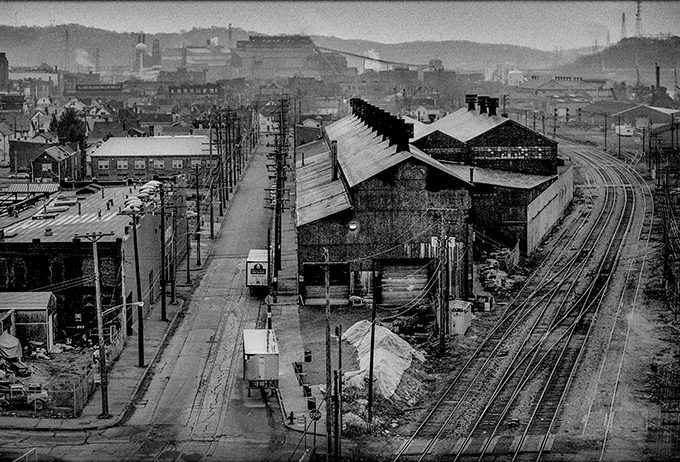

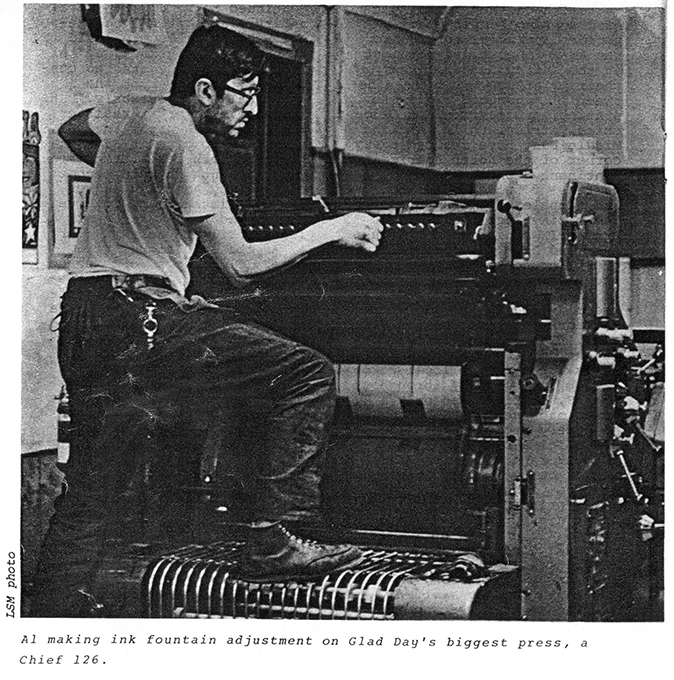

Photo Ed Warshauer March 1983.

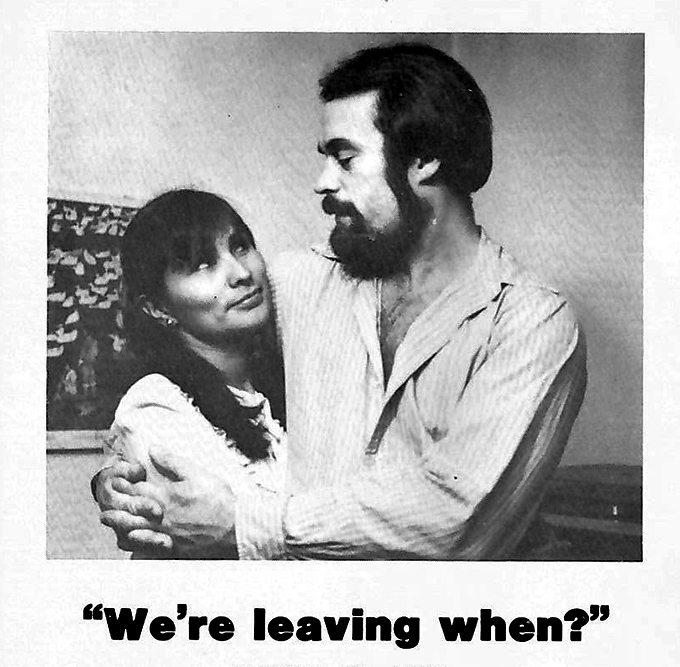

In Olney Odyssey number 19, I met the beautiful Christina L. Pérez in San Francisco on Labor Day Weekend in 1982. I returned home to Boston and potential normalcy.

Olney Odyssey #20 traces the story of how Christina came to temporarily relocate to Boston in the winter of 1982-83 and how I decided to permanently relocate to Santa Monica, California in the spring of 1983. Writing about exciting developments in the labor movement and the urgency of fighting MAGA fascism has meant a delay in this memoir. Fortunately my dear friend and accomplished writer, Byron Laursen has rescued me from my inertia and helped me to proceed with this tale. Byron has written before for the Stansbury Forum, and he has ably captured my voice and sentiments in OO#20.

This installment was rigorously fact checked by Christina L. Perez

.

Christina Hits Beantown

I met Christina on Friday, September 3rd, 1982, in a magical moment, which I described in Olney Odyssey number 19, but I had to return to Boston on Sunday, the fifth, and get back to work.

On the flight back I thought, “That was wonderful, but I’ve got to settle down and get to business here.”

Nonetheless, I told my roommate, Ed Warshauer, about this incredible woman I had met and what an amazing connection had happened.

But when I also told him that I thought the work I had in front of me took precedence over exploring a romance, he flipped. “What?” he said, “Are you kidding? Do you think something like that comes along so often that you can just let it go? You’ve got to think about pursuing this!”

He was right! Fortunately, while I thought things over, Christina lit a fire under me on Wednesday the 8th. when she called from out in California to ask, “Do you want to go to a Mexican wedding?”

“What?”

“My cousin is getting married on September 18th. Why don’t you come? I bet you’ve never been to a REAL Mexican wedding?”

I hesitated and hemmed and hawed and finally said, “I’ll think about it, I’ll think about it.” As I hemmed and hawed Christina sensed my hesitation and blurted out “ I’ll pay half your ticket!” Charmed and embarrassed, I repeated, “I’ll think about it.” Before hanging up, she said, “you won’t be disappointed.”

As soon as I got off the phone, Ed said “Are you nuts? Get your ass out there. This lady’s obviously very special!”

After a few back and forth calls I decided to catch a flight back to the Golden State, in time to be her date for her cousin’s wedding. It took place at Quiet Cannon, a beautiful venue east of Los Angeles in Monterey Park. It was a huge, extremely festive Mexican wedding – the whole extended family, hundreds of people, and mariachi musicians in their sombreros and regalia, and trumpets, guitars and guitarrones. To this day I don’t know the names of all the relatives who were there – cousins, aunts and uncles and so on – and how all their relationships intertwine.

Her parents were very pleasant to me, but I could also tell they were feeling skeptical and bemused. “Who is this Yanqui?” I imagined them thinking. “What’s he doing here? We’ve seen a lot of boyfriends. This is probably just another one.”

The whole weekend was a tremendously special time spent together, a quantum leap from the first visit, which itself had been fantastic. We went from Friday to Sunday evening, staying at her studio apartment in Santa Monica, 11th and Washington, in the Voss Conti Apartments, a Streamline Moderne building from 1937, with all the apartments overlooking a central courtyard. It’s now on the National Register of Historic Places.

By the time she saw me off at LAX I had invited her to Boston for a long weekend during Oktoberfest where she could enjoy one of her passions at the time, long-distance running, and run the Bonnie Bell 10K race. And, I could introduce her to MY family! Not to be outdone, I stepped up to the plate and offered to pay half her ticket and she didn’t hesitate one bit. Christina was coming to visit Boston. It was another era in terms of travel in 1982. Family and friends could meet each other at the airline gate and that is what I did. Unbeknownst to Christina, the actor and Boston native Ray Bolger – the Scarecrow in the Wizard of Oz – was on her flight so there was a bit of pandemonium when she was exiting the plane that added a touch more excitement to her arrival. If she was nervous there were no outward signs.

I filled her in on the plans for the weekend: hooking up with good friends, the Bonnie Bell, meeting my parents and siblings and a trip with good friends to Northampton where more family including my grandmother were hosting a late lunch. As planned, she ran the Bonnie Bell and literally ran into a rude welcome by a young boy standing at the sidelines who pointed at Christina and yelled in apparent disbelief “Look mommy, an Indian!” She was aware of Boston’s racist reputation, but this was a kid, wow! Of course, she had to chalk it up to ‘out of the mouth of babes’ and ignorant parenting. Her own large extended family had often proudly praised her indigenous features as being like those of her maternal grandmother from Mexico. This kid’s comment felt weird. “Where was she?” she asked.

I’ve always told Christina that she was an exotic sight in Boston because pale-faced people like me were most of what there was to see. Whereas her gene pool features, and dramatic cheekbones are pretty common in L.A. Still, she rolls her eyes.

All in all, it was a great weekend. As it was winding down it became obvious that our feelings for each other had escalated. We knew we wanted to make it as a couple. But one of us would have move so we could be together. We devised our plan the day before Christina was to return to Los Angeles.

It was as we drove back from Northampton with our friends Ilene Handler and Bruce Fleischer that we decided, with their help, that it made more sense for Christina to move to Boston. My heating and air conditioning training program was finishing the following April, and because Christina had interstate reciprocity with her nursing license there were many job opportunities open to her. We reasoned I could finish my training and be more marketable if I decided I wanted to try living in Los Angeles. There was always the possibility, she would remind me, “we’re crazy about each other now, but maybe our relationship won’t work out.”

Up to then we had only been with each other a total of eight days across three months. Now we were to move in together across the country, and across cultures. But she would hold onto her Santa Monica apartment. “Just in case.”

I flew out to L.A. approximately four weeks later on World Airways. It was the cheapest flight across country and a nightmare! I guessed that they only had one plane that flew back and forth from Boston to L.A. In any case, there were flight delays. I was scheduled to arrive in LA at six PM but didn’t arrive until just before midnight!

Unbeknownst to me Rita, Christina’s older sister and her husband, Bahman, had at least 25 friends and family members waiting to meet me. They hung around eating dinner as the night got late! Later, Rita told me, laughing, that she had to discourage one of Christina’s ex-boyfriends from waiting around for me to arrive from LAX. It seems he got more nervous about meeting me as the hours ticked by.

When she and I finally got to Rita’s house it was the Mexican wedding all over again. with lots of people who cheered as Christina ushered me in. I didn’t know what to expect but it was clear I was the main event! Welcome to the Perez Family!

Early the next morning it took no time to load Christina’s belongings into her two-door Toyota Celica. She had gotten the dark brown beauty tuned up recently and because it was only three years old, we didn’t expect any trouble crossing the US of A. We had one stop however before heading East on Route 66, and that was to have a quick breakfast with her mother and father, Ramona and David, in El Monte. We received the traditional “despedida,” the Mexican blessing, which I would learn to appreciate culturally as I grew to understand Christina and her family.

After a couple of hours, we were east bound on Interstate 10, heading for Boston through Arizona, New Mexico, Texas and beyond. We had to get me back in time for me to go to work early Monday at Boston City Hospital, where I was a refrigeration mechanic. We crossed North America in three days, almost non-stop, only staying in a motel for five hours in New Mexico and another in Maryland for six hours. We took turns catnapping on long stretches. We kept each other awake by talking and listening to the radio waves of the southwest. Sports, news and music kept us focused.

I was exhausted but ready to clock in at “City.” We also arrived in time for Christina to experience the crisp November Boston weather and to see her first morning snowfall. She moved into my third-floor attic room in a friend’s house on Perkins Street in Jamaica Plain, right down the street from the beautiful Jamaica Pond and Way, part of the “Emerald Necklace”, a 7-mile-long network of parks and parkways that civic visionary Frederick Law Olmsted laid out for the Boston Parks Department between 1878 and 1896.

Christina expected to eventually find a similar job as a nurse practitioner in women’s’ health, the work she had in L.A. But when she went looking she got a surprise: there was an unofficial, unstated hiring freeze for nurses throughout all of Boston’s hospitals and clinics.

She also realized competition was stiff for nursing jobs. HR people at the places she applied told her the competition for the jobs had bachelors, masters and PhD’s in nursing! She had none of the above, just a state license and national certificate in Women’s Health. She saw the writing on the wall, after practicing for 17 years without a bachelor’s degree it was time to go back to school.

One day, walking back from a job interview, she happened to walk into the Boston Indian Council (B.I.C.) near our home. She casually asked the friendly woman sitting at the front desk “What is the Boston Indian Council?’ An hour or so later, after a friendly exchange of information, Christina was offered a job there as a nurse. The woman at the desk turned out to be the director, and their friendly conversation had turned into a job interview. She was to be Nurse Case Manager for the Native American patient population of the B.I.C.

It was a very satisfying job, though she had some interesting encounters along the way. At one point a very elderly woman tried sizing her up over morning coffee and donuts and she asked Christina,

“Where are you from?”

“Los Angeles, California.”

“No,” the woman repeated, WHERE ARE YOU FROM?”

Realizing the elder woman was wanting to know the name of her ‘tribe, ’ Christina said,

“Chichimeca, Aztec.”

Without skipping a beat, the women looked at Christina with her good eye and said,

“Never heard of them!” End of conversation.

Christina was really impressed by the cold weather of Boston. In fact, she still hates it to this day. Among Christina’s friends I met at Rita’s gathering was her close friend Theresa Laursen, a film costumer. Theresa had spent her first two college years at Endicott College, in Beverly, Massachusetts, so she knew about winters in the Boston area. As a gift she mailed Christina a pair of electrified socks, designed for hunters and fishermen. She had to stow its batteries in her jacket pocket and run the wires down her trouser legs, and she had to endure merciless teasing. But on days when even the native Beantowners were complaining about their feet being cold, Christina had her secret weapon. Before long, people started asking her where they could get a pair.

When Thanksgiving came around, we went out to Andover, to my old family home, where my parents were still living. Not only did Christina get to meet my extended family, she played in our annual touch football game. As New Englanders we aspired to be at least a little bit like the Kennedys. She caught a couple of passes and made a great impression. Though I did find out later that some of my relatives were concerned that she might be a gold digger.

Not only was this as far as possible from the truth, it also begged some follow-up questions, such as: “What gold?” “Where is it?”

As a Californian, she had never dealt with a real winter. When the winter of ‘82-83 arrived,

she not only made use of her electric socks, but also began cooking up a storm. It was a great way to keep warm, and her fame began spreading for doing great things in the kitchen.

One of the people who benefitted was a newly acquired friend named Ginny Zanger, whom Christina met through a mutual friend. Ginny was the wife of Mark Zanger, the model for Megaphone Mark in the Doonesbury comic strip. Mark had gone to Yale and had been a frequent, prominent protestor and campus radical.

At the time we met the Zangers, Mark was working as a food writer for the Hearst paper in Boston, The Boston Herald. The Herald is a tabloid format paper you can conveniently read on the subway. With Ginny’s encouragement, Christina cooked a Mexican meal for Ginny, Mark and me. The Herald ended up running a centerfold feature on Christina with a stunning photo of her and some recipes, which she attributed to cooking skills learned from her father.

As soon as the Herald ran the feature, Mark alerted Christina that he got a phone call from a guy who wanted to know who this woman was and how they could get in touch with her because he was interested in putting her face on his can of products! Needless to say, Mark thankfully batted those types of calls away.

I have a wonderful picture of her standing over a hot stove and wearing a sizable woolen knit hat and a wool scarf which was her ruse for staying warm.

She also put a myth she had heard about shots of whiskey to the test. She was surprised to see that neighbors helped shovel snow out of each other’s driveways before heading off to work. The first morning she jumped in to assist the bone-chilling cold froze her brain. She had to run back into the house. Then she remembered hearing that people sometimes took a shot of whiskey to feel warm, so she drank a shot of whiskey and returned to the cold. Of course that didn’t work!

It was a demanding experience, but she got through the adversities of a Boston winter. However, we agreed that more such winters would be overdoing it. So I told her, “Since you’ve shown you’re willing to undergo hardship, I can face the challenge of being in Santa Monica.”

In April of 1983 we again packed up her Celica, this time with my belongings included. I didn’t have many. In fact, if there was a gold digger in the relationship, it probably had to be me.

We again made near-record time because she was due to go back to one of her jobs at a women’s’ health clinic in Santa Monica.

When we got past the Arizona border and were officially in California, Christina was so happy that she stopped the car so she could kneel down and kiss the pavement.

The way things worked out for both of us in the years since, there were no more Boston winters. I moved in with her at her little studio apartment on 11th Street, and then began wondering what I was going to do for work. I had worked as a refrigeration mechanic for a couple of years, using the skill set I’d learned in a technical school. But, frankly, I was a total klutz and I knew I was not going to make a career out of that trade. For starters, I never really got proficient at one of the baseline skills any refrigeration mechanic needs to have: soldering copper pipes.

I understood the science behind refrigeration, the heat and the pressure, but the touch required for soldering a joint was something that I couldn’t ever master.

Even so, I tried for work in that line, and put in applications at places like La Boulangerie in Westwood, as well as other restaurants in Santa Monica and Venice. Luckily for everyone’s sake, I didn’t get any of those jobs.

Instead, I met up with an old friend whom I’d known in Boston. David had worked in a machine shop that was organized by the United Electrical Workers, the union that I had organized into at Mass Machine shop. He’d relocated to L.A. a few years earlier. He knew my history of working at factories in Cambridge and Boston that had closed down and moved to New Hampshire. He knew that I had experience fighting against these factory closures.

“Peter,” he said, “there’s a job as the organizer with the Los Angeles Coalition Against Plant Shut-Downs (LACAPS). They’re fighting the closure of the General Motors plant in South Gate, the General Electric plant in Ontario, and the UniRoyal Tires plant on the 5 Freeway, and they need an organizer.

The Coalition was involved in various communities to fight these closures, so I interviewed for the job, and they hired me. I’d done plenty of protesting before, but this was my invitation to be a professional. The Coalition set me on the career path that has remained my focus ever since.

The office I reported to was at the First Unitarian Church on 8th street at Vermont. I met several union leaders and all these community leaders all at once. I made some lifelong friends as a result, including our friends Gary Phillips and Gilda Hass. She was on the board of the LACAPS.

On top of being a kick-start into a labor movement career, this job took me all over the Los Angeles Basin. It was how I learned up close about a city that was the polar opposite of Boston.

I was fascinated by Los Angeles. In terms of size, scope and layout, I don’t think you could find a city anywhere in the USA that’s more different than where I had grown up. In Boston, an historical house might be from 1683. In Los Angeles it might be 50 years old or less, and designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, Richard Neutra, Richard Schindler or any of the other numerous architects who evolved the modernism of Southern California, which spread around the world.

Because the history of Los Angeles was more recent, in some ways it was more compelling, and more part of the national discourse because of Hollywood and all the other media that radiate from L.A.

I was fascinated. I read everything Carey McWilliams wrote about California politics and culture and the history of the state’s labor movement.

I was so happy to be plugged into all this energy. I don’t think I would’ve ever gotten so deeply into the labor movement if I’d stayed in Boston. So that’s one more reason that my old roommate Ed was right when he said “Are you nuts? Get your ass out there.”

This is the story I tell to illustrate how the two places, Beantown and Shaky Town, are so different. As an organizer with this Coalition Against Plant Shut-Downs, I got involved in fighting the closure of a community hospital in Long Beach. I think it was called Long Beach County Hospital. Residents of Long Beach were doing all they could to keep it open. I was invited to come to one of their meetings. I came with a proposal I’d sketched out on how to fight this closure. They gave me the floor and they let me present what I had in mind. The chair said, “What do some of you feel about what he said?”

People said, “Those are great ideas. I think we should do that.”

I almost fell out of my chair. In Boston the reaction would have been “Who are you, anyway” and “which parish were you baptized in?”

Two months later I was invited back to a meeting. The chair was a wonderful man who was a retired pharmacist from New York, a Jewish-American guy who had helped found one of the great unions of America, 1199, a very progressive health care union based in New York City. He announced, “My wife Emma and I are leaving to go on vacation in Europe for a month and we need an interim chair for this group. What are we going to do?”

A woman raised her hand and pointed at me. “He’s got a lot of good ideas. Let’s make him the chair!”

For a second time I came close to actually falling out of my seat. Because again, coming from a parochial, small, insulated place like Boston, I found the openness of L.A. very liberating. As for Christina, she got back to her prior working life with ease, and our relationship – even in a small apartment – kept growing too.

…

In W. Va. and Nebraska: Can Two Working Class Candidates Crash a Multi-Millionaire’s Club in Washington, DC?

By Steve Early

Both major parties on Capitol Hill like to boast about how much more “representative” their Congressional delegations have become in recent years. But that’s only in the most discussed categories of diversity—such as race, age, gender, ethnicity, or sexual orientation. Working class Americans rarely end up in the halls of Congress. Fewer than two percent of Congress members had working class jobs at the time they were elected.

Two working class candidates hope to improve those numbers next year, by winning U.S. Senate seats in Nebraska and West Virginia, states currently represented by anti-labor politicians, but which were once bastions of a more populist, pro-worker politics.

In Nebraska, Dan Osborn is challenging two-term Republican Deb Fischer. Osborn is a steamfitter from Omaha who helped lead a successful strike by 1,500 Kellogg’s workers. They shut down plants in four states for 11 weeks in 2021.

In West Virginia, Zach Shrewsbury is also running for Senate. He’s a military veteran (as is Osborn) and a community organizer, and the grandson of a coal miner. Shrewsbury hopes to replace multi-millionaire Joe Manchin and prevent governor Jim Justice, a billionaire coal baron, from claiming the seat that the corporate Democrat is vacating.

Populist Voices

In their respective campaign launches this fall, both candidates sounded themes once familiar to voters in their home states in the heyday of progressive populism, but not heard much lately.

While picketing with General Motors workers in Martinsburg in October, Shrewsbury explained that he’s “running to win and show that working class people can run for office, even high office. We can’t be ruled by the wealthy elite who don’t understand everyday American life.”

At a campaign kick-off event in late September, Osborn denounced “the monopolistic corporations… that actually run this country” and pledged to “bring together workers, farmers, ranchers and small business owners across Nebraska around bread-and-butter issues that appeal across party lines.”

Unlike Shrewsbury, who plans to compete next year’s Democratic primary, Osborn is currently collecting the 4,000 signatures necessary to get on the November 2024 ballot as an independent. He hopes to avoid unhelpful association with the national Democratic Party in a state which chose Donald Trump over Joe Biden by 19 points in 2020 (and Trump over Hillary Clinton by an even larger margin four years earlier).

Osborn admirers in Nebraska unions, and even the state Democratic Party, believe his non-partisan stance may be helpful. According to Jeff Cooley, a railroad union official who leads the Midwest Nebraska Central Labor Council, Osborn’s focus on issues like rail safety and the PRO Act, paid leave time, minimum wage increases and misclassification of workers as independent contractors “offers hope to all workers in Nebraska regardless of political party.” Osborn’s platform also highlights the need to curb corporate misbehavior ranging from routine consumer rip-offs to Big Pharma price gouging and monopolistic practices in the meat-packing industry which favor big agriculture over small family farmers and ranchers.

A Troubled Brand

Jane Kleeb, a past Bernie Sanders delegate who chairs the Nebraska Democratic Party and serves as an Our Revolution board member, told the local media “it would be very interesting for Democrats, Libertarians, and Independents to all come together with the one goal of breaking up the one-party rule at the top of the tickets in our state.” She acknowledged to Labor Notes that, at the moment, “the brand of the Democrats is not the best when it comes to working class and communities of color voters.” Meanwhile, in rural communities like her own, “people think Democrats are wimpy, just want to tax us, and take away our guns.”

Neither Osborn nor Shrewsbury look or sound very wimpy. Before going to work for Kellogg’s as an industrial mechanic and becoming president of Bakery, Confectionary, Tobacco Workers and Grain Millers Local 50G, Osborn served in the Navy and two state national guard units. Shrewsbury was in the Marine Corps for five years. After his discharge, he joined Common Defense to rally fellow veterans against what that group calls “Trump’s corrupt agenda of hate” and “the entrenched power of greedy billionaires who have rigged our economy.”

Shrewsbury has been an organizer for Citizen Action and the New Jobs Coalition, where he met retired AFL-CIO organizing director Steward Acuff, now a resident of West Virginia. Acuff hopes to enlist national union backing for Shrewsbury’s campaign. The two of them bonded while canvassing to build grassroots support for federally-funded green jobs, environmental clean-ups, and infrastructure projects employing union labor. Acuff believes that Shrewsbury is uniquely equipped to challenge the “corporate colonialism that is still robbing a people and their state of much-needed resources.”

Shrewsbury wants to use his campaign “to help revitalize labor here and everywhere, like Bernie did.” Like Sanders, who won West Virginia’s Democratic presidential primary in 2016, Shrewsbury isn’t afraid of being red-baited either. “If caring about working-class people, caring about people having bodily autonomy, water rights, workers’ rights, makes you a socialist, then call me whatever you want. Doesn’t bother me,” he told The Guardian recently.

Fundraising Disadvantage

Osborn has raised more than $100,000 in small donations so far. Next November, Nebraska voters will also consider a ballot measure backed the Nebraska State Education Association. It would repeal the Republican-dominated state legislature’s authorization of a tax scheme that threatens financing of public education and aids private schools instead.

Osborn favors repeal, further illustrating what Kleeb calls “a real contrast between Dan and Deb Fischer,” who has built a $2.7 million re-election campaign war-chest. According to Fischer’s website, her top donors include “fellow Senate Republicans, the American Israeli PAC, the construction industry and defense contractors.”

Osborn believes that his Senate race could be “the most viable independent campaign in America” next year, particularly if Nebraska’s Democratic primary produces no serious competition for Fischer’s seat. Meanwhile, he is spending 40 hours a week doing boiler maintenance and repair work at Boys Town in Omaha, as a member of Steamfitters and Plumbers Local 464.

Osborn hopes to take more time off, from his day job soon to campaign around the state, with backers like Nebraska Railroaders for Public Safety. This advocacy group just conducted a favorable poll and then endorsed him.

Their survey of 1,048 likely voters revealed considerable discontent with Fischer, who promised to serve only two terms but is now seeking a third. Despite Osborn’s lack of name recognition, he had a slight lead over Fischer, which grew larger when survey participants were informed about the biographies and positions of both candidates.

The Nebraska Railroaders are taking that as an encouraging sign that their state still has an independent streak that could help “elect a next-generation representative of the working class instead of continuing to send out-of-touch millionaires back to Washington to fail us.”

…

Editor’s note:

Shewbury has put out a statement regarding the war being waged in Gaza between Hamas and Israel – it is included below.

“Hear me out. This email will be a bit long, but I need to share this with you.

I did not grow up in an environment where conversations about Israel and Palestine were commonplace. We were a working-class family in a small community, and foreign policy issues were not frequently discussed. We were neither Jews nor Arabs. My family has been in West Virginia for centuries, and our world was insulated. I didn’t have access to the kind of liberal arts education where history is examined from different perspectives. In the Marines, my training did not include a deep dive into the events that led to Nakba in 1948, which, by the way, means “the catastrophe” in Arabic.

I am from the same cloth as most Americans; I am a working West Virginian.

As a future U.S. Senator, I’m dedicated to deepening my knowledge and understanding of current events’ historical and legal context because the responsibility to and the influence this country has over millions of people in faraway lands is enormous. I don’t take this power lightly.

Our media industry often sensationalizes terms like war, self-defense, and human shields to mold public opinion toward the monied interests of their advertisers and influential stakeholders and the system that allows them to rake in incredible profit at the expense of truth and balanced reporting. As I broaden my context, I’m learning what these terms mean under the International Human Rights Law that we as a country claim to support and yet so rarely honor.

· The term “war” is used intentionally to create the impression that what is going on between Israel and Palestinians is a conflict between two autonomous states. That cannot be further from the truth, as Israel is the occupier, and Hamas is the governing body of the occupied territory but not a sovereign government.

· Israel has obligations under international law to provide services and ensure the safety of its occupied population. On October 7th, when Hamas attacked, they had the right to use police powers to apprehend the criminals and prosecute them but not to use their massive military might against an essentially defenseless people. We cannot use the “right to defense” language describing Israel’s revenge that has so far killed approximately 18,000 Palestinians, two-thirds of whom are women and children.

· In the context of international law, using human shields means actually putting a civilian in front of a military vehicle or combatants while advancing on the enemy. It doesn’t mean having combatants living or even operating in the areas civilians occupy. Using human shields is a war crime. Israel uses the human shield argument to justify their illegal, immoral, massive-scale attacks on civilians and civilian infrastructure. Israel wants to drive the Palestinians out of Gaza.”

…

Who Are These Nice People Who Want Me to Get a Raise?

By Tom Gallagher

One day, I received a very nice card in the mail. It had a picture of Uncle Sam pointing out at me over the words “Give yourself a raise,” and included a tear-off mailer addressed to “UESF Membership Specialist.” It read, “Effective immediately, I resign any membership I may have in all levels of United Educators of San Francisco (UESF).” All I needed to do to get my raise was sign it and send it back to that membership specialist, c/o Freedom Foundation in Orange, California.

Just who were these nice people, I wondered, who were looking out for my financial well-being—and even had a specialist devoted to my local union? The answer turned out to be quite the story.

Heading to the Freedom Foundation website, I found a prominently placed video telling how “Los Angeles high school teacher, Glenn Laird, reached his breaking point after his teacher (UTLA) demanded we defund the police.” Given that Glenn is a teacher himself, I gathered that the questionable grammar and the mistake of referring to United Teachers of Los Angeles as a “teacher” rather than a union were likely typos on the part of the freedom folks. Odd though, I thought, that such an obviously well-funded organization would not employ the services of a proofreader, but then the website quickly makes it quite clear that it’s not the education business that these folks are in.

The business they are in is union-busting. In their words: “The Freedom Foundation is more than a think tank. We’re more than an action tank. We’re a battle tank that’s battering the entrenched power of left-wing government union bosses who represent a permanent lobby for bigger government, higher taxes, and radical social agendas.”

“Why We Fight,” the organization’s statement of purpose, proclaims that “government unions are a root cause of every growing national dysfunction in America.” (Every one of them!) And the mailing I had received, I learned, was part of the organization’s Nationwide Opt Out Project, aimed at “taking on government union bosses and defunding their radical unconstitutional agenda” because “GOVERNMENT UNIONS ARE THE SINGLE GREATEST OBSTACLE TO A FREE AMERICA” (All caps on the website) that “REPRESENT NOTHING LESS THAN A LOBBY FOR NATIONAL DECLINE AND DESTRUCTION. WE MUST DEFEAT THEM FIRST BEFORE THEY DESTROY OUR COUNTRY.” The website’s interactive 50-state map will allow you to locate the specific local union that the foundation would like you to leave, and its “dues calculator” allows you to compute how much you will have saved in union dues—compounded at 6%—by the time of your retirement.

While government employee unions are the organization’s particular bugbear, they’re not really too keen on unions of any sort. While conceding that “organized labor began as a way for workers to improve their standing in our country,” the foundation believes that “slowly it transformed into a weapon to destroy it.” And then there’s those darned “Liberal state governments” that are “like cockroaches eking out survival amid the fallout of a nuclear war.”

The freedom folks find evidence of this “national decline” pervasive throughout American society, extending to the “fiscal crisis” that “has forced government to take increasingly perverse actions to keep the system afloat, including multi-trillion bailouts of state government in the form of ‘Covid Emergency’ funds that were airdropped across America in 2020 at the height of mass hysteria over the virus.” For their part, they look forward to “a day when opportunity, responsible self-governance, and free markets flourish in America because its citizens understand and defend the principles from which freedom is derived.” As far as the foundation itself goes, “We accept no government support.”

What never? Well, hardly ever. It would appear that even these hardcore free marketeers were not immune to the Covid “mass hysteria.” Noting that at the time “unions specifically weren’t eligible for the paycheck protection program, so they were left to fend for themselves,” the July 8, 2020, Seattle Times reported, “Not so the Freedom Foundation, though—it got between $350,000 to $1 million from the federal relief fund, records show.” ProPublica reports the exact figure was a $644,125 Paycheck Protection Program loan given to protect the jobs of 82 campaigners against excess government spending. (The amount subsequently forgiven the resolutely anti-government bailout organization was $651,157, the difference representing accrued interest.)

To be fair, though, this government “airdrop” by no means represents the core of the organization’s funding. The June 28, 2018, Los Angeles Times reported that although the group’s labor policy director “declined to identify any of the group’s donors, which he said include businesses, foundations, and individuals ‘from all different walks of life,’” the group’s “tax filings reveal a who’s-who of wealthy conservative groups. Among them are the Sarah Scaife Foundation, backed by the estate of right-wing billionaire Richard Mellon Scaife; Donors Trust, which has gotten millions of dollars from a charity backed by conservative billionaire brothers Charles and David Koch; from the Richard and Helen DeVos Foundation, backed by the family of U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos; and the State Policy Network, which has received funding from Donors Trust and is chaired by a vice president of the Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation.”

Who are these individuals and organizations? According to SourceWatch, a project of the Center for Media and Democracy, the Sarah Scaife Foundation gives “tens of millions of dollars annually to fund right-wing organizations such as the American Legislative Exchange Council, the American Enterprise Institute, and the Heritage Foundation, and anti-immigrant and islamophobic organizations such as the Center for Immigration Studies and the David Horowitz Freedom Center.”

In her August 23, 2010, New Yorker article “Covert Operations,” Jane Mayer described the billionaire Koch brothers as “longtime libertarians who believe in drastically lower personal and corporate taxes, minimal social services for the needy, and much less oversight of industry—especially environmental regulation.” DeVos, of course, we know from the Trump administration, as well by association with her brother Eric Prince, who founded the mercenary organization formerly known as Blackwater. SourceWatch says that “Harry Bradley was one of the original charter members of the far right-wing John Birch Society, along with another Birch Society board member, Fred Koch, the father of Koch Industries’ billionaire brothers and owners, Charles and David Koch.”

In other words, the Freedom Foundation is hardwired to hard-right money. In a 2016 fundraising letter, Tracy Sharp, president and CEO of the State Policy Network—which counts the Freedom Foundation as an affiliate—was quite clear as to the orientation and policy goals of these organizations: “The Big Government unions are the #1 obstacle to freedom in the states” because, among other things, they support “a universal $15 minimum wage” and “defend Obamacare at all costs,” and—here we cut to the prime motivation behind the expenditure of all this hard right money—“They want to redistribute wealth.” She concludes, “And yes, they are the funding arm of the Progressive Left.”

The letter also touts the network’s victories in defunding the left in a number of states including Wisconsin and Michigan. Close followers of the Electoral College map will remember that in 2016 Donald Trump won Wisconsin by 23,000 votes and Michigan by 11,000, as well as the fact that his failure to repeat those narrow wins caused his eviction from the White House four years later. (State Policy Network donors include Philip Morris, Kraft Foods, Facebook, Microsoft, AT&T, Time Warner Cable, Verizon, and Comcast. Its Indiana affiliate was once headed by former Vice President Mike Pence.)

Although the Freedom Foundation operates as a tax-exempt 501(c)(3) charitable organization, a status requiring abstention from partisan politics, it’s not shy about expressing its views in the political arena. The 2018 Supreme Court decision in the case of Janus v. AFSCME ended the ability of public sector unions to collect “agency fees” from non-members, a practice designed to reimburse a union for the costs accrued in their representation of non-members as part of the bargaining unit. This decision, long sought by right-wing organizations, would not have happened had Donald Trump not recently appointed Neil Gorsuch to the court, an appointment with a specific political history.