OO # 8 Mass Machine and the United Electrical Workers (UE)

By Peter Olney

“The litmus test appears to be whether they are perceived as champions and organizers around the rank and file’s basic needs or not”

Massachusetts Machine Shop, Inc. was a small metal stamping factory on Albany Street opposite Boston City Hospital in the heart of Roxbury, Massachusetts. The company manufactured washers, burrs and shims of all shapes and sizes. The Knight family of Marblehead had owned the company for generations. Total employment was 60 workers toiling in an old four-story brick factory building whose parking lot abutted the giant Stride Rite shoe corporation across the street.

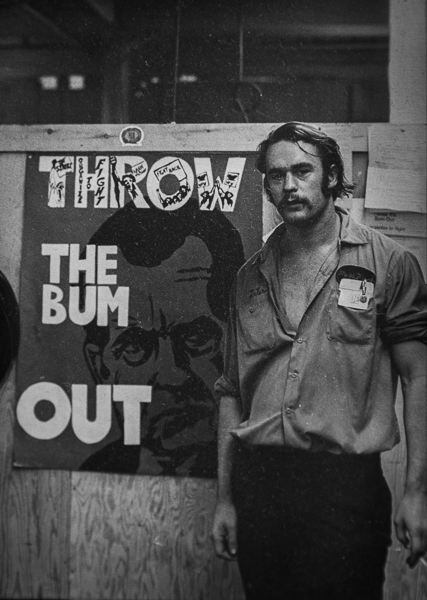

Mass Machine was not a citadel of capitalism at the commanding heights of the economy, but a lot happened in the three years that I worked there from 1973-75. Our organizing there generated a lot of lessons and also a lot of illusions. I say our organizing because the factory was “salted” by four of us, all with different political outlooks. Salting is an old term that refers to the practice of politically conscious organizers going to work in a factory, mill, mine, hospital or other service workplace to organize a union or strengthen the existing union. The metaphor comes from “salting” a mine to bring out the richness of the ores or “salting” a wound to exacerbate the sores. Salting is the richest term, but “industrializing” or “colonizing” are oft used descriptors for this political practice which has a long history on the American left. There is a fine biography of Hapgood Powers entitled “From Harvard to the Ranks of Labor” by Robert Bussell, that recounts the odyssey of a Harvard student who participates in some of the most epic battles of labor in the 20’s and 30’s as a worker and an organizer.

My choice of Mass Machine as a place to “salt” was not the product of any deep reflection on strategy or any thought of paralyzing capitalism by striking at key sectors of the economy. At the time if I had been in one of the many Maoist political formations I would have been directed to seek work at one of the three “Generals” in the greater Boston area. General Electric has a massive manufacturing operation (albeit downsized today) that makes giant gears and jet engines in Lynn. General Motors had an assembly plant in Framingham. The Fore River in Quincy was home to the giant ship builder, General Dynamics. All these facilities were well stocked with left wing agitators. At the time I was working at NECCO in the fall of 1972 I was part of the Red Lantern Collective in Cambridge. The collective took its name from the title of a revolutionary Peking Opera performed on May 1, 1970. We were all radicals out of Harvard grappling with how to be revolutionaries. One thing that was respected and exalted was the process of transforming yourself, betraying your class background by becoming a worker and organizing. So when I met up with some left-wingers working at Mass Machine who were committed to organizing a union there, I jumped on board. They were welcoming of me as my command of Italian was considered a big asset, a third of the workforce was from the region of Catania and the cities of Avellino and Benevento.

In late January of 1973 I began my employment at Mass Machine Shop. I was hired as a punch press man. I fed sheets of metal under a cutting tool that cycled up and down when operated by a foot pedal clutch. My press was manual and I was handling heavy metal stock that was cut into washers. Other presses at Mass Machine were automatic, running thinner stock off of coils. The presses all had individual electric motors, but the old overhead belts that had been driven by a universal shaft were still hanging from the ceiling. The problem with the presses was that the clutches were not precise and the cutting tool would sometimes cycle on its own creating the possibility of danger to the digits. My first week on the job, the punch repeated on me when I had my left thumb in the die area. I escaped with a slight wound, but the scar reminds me of Mass Machine to this day. One of my fellow workers was not so lucky. The small factory was abuzz when Pat Caizzi our foreman commanded Salvatore Masi, the long time maintenance mechanic to clean up the blood and skin from the die area after an employee’s finger was chopped off. Sal was upset and let everyone know that he did not like being forced to confront the gore of the unfortunate accident. In an industrial setting, the maintenance mechanics play a key role because workers rely on them to keep their machines running, and they have the run of the factory so they become message carriers. Sal had been a loyal Knight family guy, but now he was talking union.

There were four of us who were the industrial salts all with differing political perspectives, but when it became clear that there was “heat” among the workers, a desire to organize, we had to figure out what union to work with. We knew that the International Association of Machinists (IAM) and the United Steelworkers (USW) represented metal manufacturing facilities. However we found that there was a Local 262 of the United Electrical Workers with small manufacturing facilities in the Boston area. This was an amalgamated local with many smaller to mid size shops in its membership unlike a giant single corporation/single plant local like the unions at the 3 “Generals”. The winter meeting of District 2 of the United Electrical workers was to be held on a weekend in February at a hotel in Framingham. We asked the union if we could attend and were invited to meet the delegates from all over New England. After the usual formal agenda issues of new business, old business and Good and Welfare were dealt with, International Representative Don Tormey was asked to make his report to the District. Tormey was a legendary organizer and leftist who had traveled all over the country and Canada (hence the designation International Rep) organizing and representing workers. Tormey must have known that we, young impressionable leftists, were in the audience. He launched into a denunciation of capitalism and its evils. He linked it to the challenges that UE members were facing in their workplaces. We were heating up! Then he wrapped up his remarks by blasting the control that capital and the government exercise over workers and concluded by declaring that, “We need a dictatorship of the proletariat.” We decided there was no need to interview any other unions. We drove east back to Boston warming to the task of organizing our fellow workers into the United Electrical Workers, the UE.

I have often wondered thinking back on Tormey’s speech as to whether he was regularly accustomed to reveal his politics so openly to all the members of the UE District Council and the rank and file. After all even in the ranks of the UE like any other trade union in the United States there is a huge spectrum of political opinion. Did Brother Tormey fear that being so open about his socialist politics would make him prone to attacks and possible retribution? He certainly must have experienced the challenges of the Red Scare McCarthy period in this country when Communist labor leaders and unions were public enemy number one. In studying history though it appears that many Reds have been open about their politics and still held in high esteem by more conservative union sistren and brethren. The litmus test appears to be whether they are perceived as champions and organizers around the rank and file’s basic needs or not. I have seen other union leaders who have openly displayed their left politics but forgotten to tend to the needs of their rank and file, savaged by worthless opportunist opponents who fill that vacuum in leadership of the day-to-day struggles.

The most famous example of this dynamic in the UE was the case of Bill Sentner (here and here) who was the leader of the UE District based in St Louis during the red scare of the early fifties. Try as they might the local power structure, politicians and employers could not dislodge the open communist, Sentner. The rank and file supported him and was not surprised about his political affiliations because they had never been a secret. It was only when the UE national leadership perceived his presence as a problem that he stepped down. The same is true for the legendary leader of the March Inland in Hawaii that organized all the plantation sugar and pineapple workers into the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU) in the 40’s and 50”s. Crew cut Okie Jack Hall was an open communist and yet no amount of red baiting including directly from the US Senate that was to approve statehood for Hawaii could dislodge him from the favor of ILWU members. There is something to be said for sinking deep roots with the workers, sharing their lives and fighting with them for better conditions of life and work. It does wonders for one’s credibility on a host of issues including socialist ideas.

Next OO#9 – Winning the UE at Mass Machine and a first labor contract in three languages

Peter,

FYI – Don Tormey’s rabble rousing speech was not delivered because he knew you and your lefty friends were there checking out the union. He regularly offered his marxist analysis at UE council meetings, staff meetings, local meetings and in private conversation. When I was hired by UE in 1972, Don was my supervisor and mentor. He took me through first contract negotiations at a shop I organized about 3 months after being hired. There was no better teacher, mentor, comrade and friend than Don. He was and remains my working class hero and inspiration.

Great stuff as always, old buddy. What a different time, both politically and economically. I was an 18-year new arrival, a student, in Cambridge. I had three unionized jobs during my time at dear old Harvard. These days, young people – hell, older people too – have their choice of minimum wage jobs! I worked for the garbage company (Teamsters) that collected at the campus – which I foolishly gave to my freshman classmate Tom Bailey, when he got thrown out of school for some Progressive Labor Party/Worker Student Alliance action; at the General Motors Assembly Division in Framingham (UAW); and at Boston Gas in Jamaica Plains (Steelworkers). What was most amazing was how easy it was to get the jobs – I just applied. The one at GMAD I hustled through a relationship I developed with a UAW Business Agent while writing a labor history paper. But GMAD were hiring. The worst jobs I had were cleaning offices at night, and selling newspapers in Harvard Square with Tommie. No union, low pay.

I made $8.60 a hour at GMAD. That was a lot of money in 1972-3. I still remember how hard it was to keep up with the assembly line. At one spot welding station, I think I made 50% of the required welds – I likely caused fenders to fall off of GMAD products all over the nation. My fellow workers – almost all men – hipped me the safety hazards of wearing my long hair down, or having bracelets I did however join in revolutionary worker struggles. Our first job action was over the foreman raiding a brother unions members locker and stealing his alcohol and uppers! The union, through our shop stewards, did engage in running battles with the foremen over line speed and safety conditions. As a spot welder, I wore fire proof coveralls. And they never caught on fire. But I kept a bottle of water at my station to put out the embers that landed on my outfit, if and when they burned through to my skin. I was in the prima physical condition of my life, and could barely keep up with the line.

The work at GMAD reinforced for me lessons I’d learned growing up, working in a cemetery, and a Coca-Cola Bottling Plant, earlier in my life. I did not want to be a blue-collar worker. I didn’t want to spend my life on such physically demanding, stultifyingly boring jobs. I was going to attend and graduate from college. I wanted to be a professional. I was a Leftist, but I wasn’t crazy.