Olney Odyssey #20

By Peter Olney

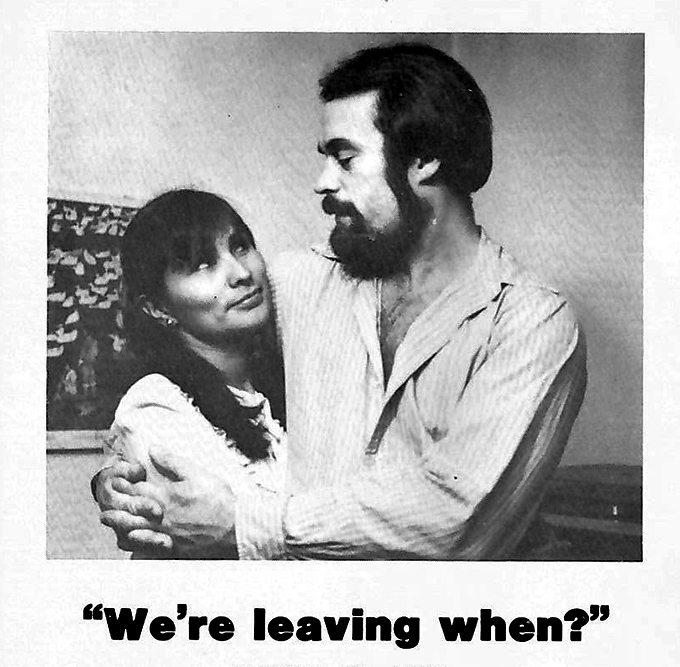

Photo Ed Warshauer March 1983.

In Olney Odyssey number 19, I met the beautiful Christina L. Pérez in San Francisco on Labor Day Weekend in 1982. I returned home to Boston and potential normalcy.

Olney Odyssey #20 traces the story of how Christina came to temporarily relocate to Boston in the winter of 1982-83 and how I decided to permanently relocate to Santa Monica, California in the spring of 1983. Writing about exciting developments in the labor movement and the urgency of fighting MAGA fascism has meant a delay in this memoir. Fortunately my dear friend and accomplished writer, Byron Laursen has rescued me from my inertia and helped me to proceed with this tale. Byron has written before for the Stansbury Forum, and he has ably captured my voice and sentiments in OO#20.

This installment was rigorously fact checked by Christina L. Perez

.

Christina Hits Beantown

I met Christina on Friday, September 3rd, 1982, in a magical moment, which I described in Olney Odyssey number 19, but I had to return to Boston on Sunday, the fifth, and get back to work.

On the flight back I thought, “That was wonderful, but I’ve got to settle down and get to business here.”

Nonetheless, I told my roommate, Ed Warshauer, about this incredible woman I had met and what an amazing connection had happened.

But when I also told him that I thought the work I had in front of me took precedence over exploring a romance, he flipped. “What?” he said, “Are you kidding? Do you think something like that comes along so often that you can just let it go? You’ve got to think about pursuing this!”

He was right! Fortunately, while I thought things over, Christina lit a fire under me on Wednesday the 8th. when she called from out in California to ask, “Do you want to go to a Mexican wedding?”

“What?”

“My cousin is getting married on September 18th. Why don’t you come? I bet you’ve never been to a REAL Mexican wedding?”

I hesitated and hemmed and hawed and finally said, “I’ll think about it, I’ll think about it.” As I hemmed and hawed Christina sensed my hesitation and blurted out “ I’ll pay half your ticket!” Charmed and embarrassed, I repeated, “I’ll think about it.” Before hanging up, she said, “you won’t be disappointed.”

As soon as I got off the phone, Ed said “Are you nuts? Get your ass out there. This lady’s obviously very special!”

After a few back and forth calls I decided to catch a flight back to the Golden State, in time to be her date for her cousin’s wedding. It took place at Quiet Cannon, a beautiful venue east of Los Angeles in Monterey Park. It was a huge, extremely festive Mexican wedding – the whole extended family, hundreds of people, and mariachi musicians in their sombreros and regalia, and trumpets, guitars and guitarrones. To this day I don’t know the names of all the relatives who were there – cousins, aunts and uncles and so on – and how all their relationships intertwine.

Her parents were very pleasant to me, but I could also tell they were feeling skeptical and bemused. “Who is this Yanqui?” I imagined them thinking. “What’s he doing here? We’ve seen a lot of boyfriends. This is probably just another one.”

The whole weekend was a tremendously special time spent together, a quantum leap from the first visit, which itself had been fantastic. We went from Friday to Sunday evening, staying at her studio apartment in Santa Monica, 11th and Washington, in the Voss Conti Apartments, a Streamline Moderne building from 1937, with all the apartments overlooking a central courtyard. It’s now on the National Register of Historic Places.

By the time she saw me off at LAX I had invited her to Boston for a long weekend during Oktoberfest where she could enjoy one of her passions at the time, long-distance running, and run the Bonnie Bell 10K race. And, I could introduce her to MY family! Not to be outdone, I stepped up to the plate and offered to pay half her ticket and she didn’t hesitate one bit. Christina was coming to visit Boston. It was another era in terms of travel in 1982. Family and friends could meet each other at the airline gate and that is what I did. Unbeknownst to Christina, the actor and Boston native Ray Bolger – the Scarecrow in the Wizard of Oz – was on her flight so there was a bit of pandemonium when she was exiting the plane that added a touch more excitement to her arrival. If she was nervous there were no outward signs.

I filled her in on the plans for the weekend: hooking up with good friends, the Bonnie Bell, meeting my parents and siblings and a trip with good friends to Northampton where more family including my grandmother were hosting a late lunch. As planned, she ran the Bonnie Bell and literally ran into a rude welcome by a young boy standing at the sidelines who pointed at Christina and yelled in apparent disbelief “Look mommy, an Indian!” She was aware of Boston’s racist reputation, but this was a kid, wow! Of course, she had to chalk it up to ‘out of the mouth of babes’ and ignorant parenting. Her own large extended family had often proudly praised her indigenous features as being like those of her maternal grandmother from Mexico. This kid’s comment felt weird. “Where was she?” she asked.

I’ve always told Christina that she was an exotic sight in Boston because pale-faced people like me were most of what there was to see. Whereas her gene pool features, and dramatic cheekbones are pretty common in L.A. Still, she rolls her eyes.

All in all, it was a great weekend. As it was winding down it became obvious that our feelings for each other had escalated. We knew we wanted to make it as a couple. But one of us would have move so we could be together. We devised our plan the day before Christina was to return to Los Angeles.

It was as we drove back from Northampton with our friends Ilene Handler and Bruce Fleischer that we decided, with their help, that it made more sense for Christina to move to Boston. My heating and air conditioning training program was finishing the following April, and because Christina had interstate reciprocity with her nursing license there were many job opportunities open to her. We reasoned I could finish my training and be more marketable if I decided I wanted to try living in Los Angeles. There was always the possibility, she would remind me, “we’re crazy about each other now, but maybe our relationship won’t work out.”

Up to then we had only been with each other a total of eight days across three months. Now we were to move in together across the country, and across cultures. But she would hold onto her Santa Monica apartment. “Just in case.”

I flew out to L.A. approximately four weeks later on World Airways. It was the cheapest flight across country and a nightmare! I guessed that they only had one plane that flew back and forth from Boston to L.A. In any case, there were flight delays. I was scheduled to arrive in LA at six PM but didn’t arrive until just before midnight!

Unbeknownst to me Rita, Christina’s older sister and her husband, Bahman, had at least 25 friends and family members waiting to meet me. They hung around eating dinner as the night got late! Later, Rita told me, laughing, that she had to discourage one of Christina’s ex-boyfriends from waiting around for me to arrive from LAX. It seems he got more nervous about meeting me as the hours ticked by.

When she and I finally got to Rita’s house it was the Mexican wedding all over again. with lots of people who cheered as Christina ushered me in. I didn’t know what to expect but it was clear I was the main event! Welcome to the Perez Family!

Early the next morning it took no time to load Christina’s belongings into her two-door Toyota Celica. She had gotten the dark brown beauty tuned up recently and because it was only three years old, we didn’t expect any trouble crossing the US of A. We had one stop however before heading East on Route 66, and that was to have a quick breakfast with her mother and father, Ramona and David, in El Monte. We received the traditional “despedida,” the Mexican blessing, which I would learn to appreciate culturally as I grew to understand Christina and her family.

After a couple of hours, we were east bound on Interstate 10, heading for Boston through Arizona, New Mexico, Texas and beyond. We had to get me back in time for me to go to work early Monday at Boston City Hospital, where I was a refrigeration mechanic. We crossed North America in three days, almost non-stop, only staying in a motel for five hours in New Mexico and another in Maryland for six hours. We took turns catnapping on long stretches. We kept each other awake by talking and listening to the radio waves of the southwest. Sports, news and music kept us focused.

I was exhausted but ready to clock in at “City.” We also arrived in time for Christina to experience the crisp November Boston weather and to see her first morning snowfall. She moved into my third-floor attic room in a friend’s house on Perkins Street in Jamaica Plain, right down the street from the beautiful Jamaica Pond and Way, part of the “Emerald Necklace”, a 7-mile-long network of parks and parkways that civic visionary Frederick Law Olmsted laid out for the Boston Parks Department between 1878 and 1896.

Christina expected to eventually find a similar job as a nurse practitioner in women’s’ health, the work she had in L.A. But when she went looking she got a surprise: there was an unofficial, unstated hiring freeze for nurses throughout all of Boston’s hospitals and clinics.

She also realized competition was stiff for nursing jobs. HR people at the places she applied told her the competition for the jobs had bachelors, masters and PhD’s in nursing! She had none of the above, just a state license and national certificate in Women’s Health. She saw the writing on the wall, after practicing for 17 years without a bachelor’s degree it was time to go back to school.

One day, walking back from a job interview, she happened to walk into the Boston Indian Council (B.I.C.) near our home. She casually asked the friendly woman sitting at the front desk “What is the Boston Indian Council?’ An hour or so later, after a friendly exchange of information, Christina was offered a job there as a nurse. The woman at the desk turned out to be the director, and their friendly conversation had turned into a job interview. She was to be Nurse Case Manager for the Native American patient population of the B.I.C.

It was a very satisfying job, though she had some interesting encounters along the way. At one point a very elderly woman tried sizing her up over morning coffee and donuts and she asked Christina,

“Where are you from?”

“Los Angeles, California.”

“No,” the woman repeated, WHERE ARE YOU FROM?”

Realizing the elder woman was wanting to know the name of her ‘tribe, ’ Christina said,

“Chichimeca, Aztec.”

Without skipping a beat, the women looked at Christina with her good eye and said,

“Never heard of them!” End of conversation.

Christina was really impressed by the cold weather of Boston. In fact, she still hates it to this day. Among Christina’s friends I met at Rita’s gathering was her close friend Theresa Laursen, a film costumer. Theresa had spent her first two college years at Endicott College, in Beverly, Massachusetts, so she knew about winters in the Boston area. As a gift she mailed Christina a pair of electrified socks, designed for hunters and fishermen. She had to stow its batteries in her jacket pocket and run the wires down her trouser legs, and she had to endure merciless teasing. But on days when even the native Beantowners were complaining about their feet being cold, Christina had her secret weapon. Before long, people started asking her where they could get a pair.

When Thanksgiving came around, we went out to Andover, to my old family home, where my parents were still living. Not only did Christina get to meet my extended family, she played in our annual touch football game. As New Englanders we aspired to be at least a little bit like the Kennedys. She caught a couple of passes and made a great impression. Though I did find out later that some of my relatives were concerned that she might be a gold digger.

Not only was this as far as possible from the truth, it also begged some follow-up questions, such as: “What gold?” “Where is it?”

As a Californian, she had never dealt with a real winter. When the winter of ‘82-83 arrived,

she not only made use of her electric socks, but also began cooking up a storm. It was a great way to keep warm, and her fame began spreading for doing great things in the kitchen.

One of the people who benefitted was a newly acquired friend named Ginny Zanger, whom Christina met through a mutual friend. Ginny was the wife of Mark Zanger, the model for Megaphone Mark in the Doonesbury comic strip. Mark had gone to Yale and had been a frequent, prominent protestor and campus radical.

At the time we met the Zangers, Mark was working as a food writer for the Hearst paper in Boston, The Boston Herald. The Herald is a tabloid format paper you can conveniently read on the subway. With Ginny’s encouragement, Christina cooked a Mexican meal for Ginny, Mark and me. The Herald ended up running a centerfold feature on Christina with a stunning photo of her and some recipes, which she attributed to cooking skills learned from her father.

As soon as the Herald ran the feature, Mark alerted Christina that he got a phone call from a guy who wanted to know who this woman was and how they could get in touch with her because he was interested in putting her face on his can of products! Needless to say, Mark thankfully batted those types of calls away.

I have a wonderful picture of her standing over a hot stove and wearing a sizable woolen knit hat and a wool scarf which was her ruse for staying warm.

She also put a myth she had heard about shots of whiskey to the test. She was surprised to see that neighbors helped shovel snow out of each other’s driveways before heading off to work. The first morning she jumped in to assist the bone-chilling cold froze her brain. She had to run back into the house. Then she remembered hearing that people sometimes took a shot of whiskey to feel warm, so she drank a shot of whiskey and returned to the cold. Of course that didn’t work!

It was a demanding experience, but she got through the adversities of a Boston winter. However, we agreed that more such winters would be overdoing it. So I told her, “Since you’ve shown you’re willing to undergo hardship, I can face the challenge of being in Santa Monica.”

In April of 1983 we again packed up her Celica, this time with my belongings included. I didn’t have many. In fact, if there was a gold digger in the relationship, it probably had to be me.

We again made near-record time because she was due to go back to one of her jobs at a women’s’ health clinic in Santa Monica.

When we got past the Arizona border and were officially in California, Christina was so happy that she stopped the car so she could kneel down and kiss the pavement.

The way things worked out for both of us in the years since, there were no more Boston winters. I moved in with her at her little studio apartment on 11th Street, and then began wondering what I was going to do for work. I had worked as a refrigeration mechanic for a couple of years, using the skill set I’d learned in a technical school. But, frankly, I was a total klutz and I knew I was not going to make a career out of that trade. For starters, I never really got proficient at one of the baseline skills any refrigeration mechanic needs to have: soldering copper pipes.

I understood the science behind refrigeration, the heat and the pressure, but the touch required for soldering a joint was something that I couldn’t ever master.

Even so, I tried for work in that line, and put in applications at places like La Boulangerie in Westwood, as well as other restaurants in Santa Monica and Venice. Luckily for everyone’s sake, I didn’t get any of those jobs.

Instead, I met up with an old friend whom I’d known in Boston. David had worked in a machine shop that was organized by the United Electrical Workers, the union that I had organized into at Mass Machine shop. He’d relocated to L.A. a few years earlier. He knew my history of working at factories in Cambridge and Boston that had closed down and moved to New Hampshire. He knew that I had experience fighting against these factory closures.

“Peter,” he said, “there’s a job as the organizer with the Los Angeles Coalition Against Plant Shut-Downs (LACAPS). They’re fighting the closure of the General Motors plant in South Gate, the General Electric plant in Ontario, and the UniRoyal Tires plant on the 5 Freeway, and they need an organizer.

The Coalition was involved in various communities to fight these closures, so I interviewed for the job, and they hired me. I’d done plenty of protesting before, but this was my invitation to be a professional. The Coalition set me on the career path that has remained my focus ever since.

The office I reported to was at the First Unitarian Church on 8th street at Vermont. I met several union leaders and all these community leaders all at once. I made some lifelong friends as a result, including our friends Gary Phillips and Gilda Hass. She was on the board of the LACAPS.

On top of being a kick-start into a labor movement career, this job took me all over the Los Angeles Basin. It was how I learned up close about a city that was the polar opposite of Boston.

I was fascinated by Los Angeles. In terms of size, scope and layout, I don’t think you could find a city anywhere in the USA that’s more different than where I had grown up. In Boston, an historical house might be from 1683. In Los Angeles it might be 50 years old or less, and designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, Richard Neutra, Richard Schindler or any of the other numerous architects who evolved the modernism of Southern California, which spread around the world.

Because the history of Los Angeles was more recent, in some ways it was more compelling, and more part of the national discourse because of Hollywood and all the other media that radiate from L.A.

I was fascinated. I read everything Carey McWilliams wrote about California politics and culture and the history of the state’s labor movement.

I was so happy to be plugged into all this energy. I don’t think I would’ve ever gotten so deeply into the labor movement if I’d stayed in Boston. So that’s one more reason that my old roommate Ed was right when he said “Are you nuts? Get your ass out there.”

This is the story I tell to illustrate how the two places, Beantown and Shaky Town, are so different. As an organizer with this Coalition Against Plant Shut-Downs, I got involved in fighting the closure of a community hospital in Long Beach. I think it was called Long Beach County Hospital. Residents of Long Beach were doing all they could to keep it open. I was invited to come to one of their meetings. I came with a proposal I’d sketched out on how to fight this closure. They gave me the floor and they let me present what I had in mind. The chair said, “What do some of you feel about what he said?”

People said, “Those are great ideas. I think we should do that.”

I almost fell out of my chair. In Boston the reaction would have been “Who are you, anyway” and “which parish were you baptized in?”

Two months later I was invited back to a meeting. The chair was a wonderful man who was a retired pharmacist from New York, a Jewish-American guy who had helped found one of the great unions of America, 1199, a very progressive health care union based in New York City. He announced, “My wife Emma and I are leaving to go on vacation in Europe for a month and we need an interim chair for this group. What are we going to do?”

A woman raised her hand and pointed at me. “He’s got a lot of good ideas. Let’s make him the chair!”

For a second time I came close to actually falling out of my seat. Because again, coming from a parochial, small, insulated place like Boston, I found the openness of L.A. very liberating. As for Christina, she got back to her prior working life with ease, and our relationship – even in a small apartment – kept growing too.

…

Love this!!!