Nerve Centers

By Nicola Benvenuti

My initial contact with a powerful and class concious labor movement came in 1971-72 when I was studying at the University of Florence in Tuscany, Italy. I witnessed massive marches of workers protesting the war in Vietnam and carrying the red banners of the Italian Communist Party! I also played on an Italian rugby team in Florence. One of my teammates was Nicola Benvenuti, at the time a miltant in the PCI – Partito Communista Italiano. He has remained a lifelong family friend, and I always go to him for interpretation of Italian current events. When we published Labor Power and Strategy, I immediately sent him a review copy because I value his wisdom on these matters. What follows are his observations on the book from the perspective of someone who has particpated in working class politics in a society where the PCI commanded the loyalty of the working class and polled 34.4% of the vote in 1976.

Peter Olney, Co-Editor of the Stansbury Forum and

Labor Power and Strategy

.

Labor Power and Strategy PM Press 2023 – A Review from an Italian Comrade, Nicola Benvenuti

The first thing that strikes me about this book is its title. It reminds me of political literature published in the year 1968. Two of the expressions it contains come across as especially reminiscent of those times: “Worker Power” and “Strategy”.

Workers’ Power (Potere Operaio) [1] was also the name of an extra-parliamentary self defined revolutionary student and workers’ organzation, that like other left political groups and parties, traced its roots back to an original Marxism, the concept of the working class as the general class embodying the values and principles for a radical reorganization of society. Worker Power was the vehicle for the socialist revolution: laborers could blockade the whole of society by choosing to abstain from work. The method of struggle deriving from that idea was the general strike, which presupposed the overall organization of the working class, or at least the majority of it, at both the union and the political level.

Everyone in those years associated the word “Strategy” with the effects of the workers’ actions. In this view, workers’ material needs, as theorized by the spontaneists, were leveraged to foster a natural class consciousness. Others emphasized the role of the revolutionary party as a collective intellectual capable of blocking the mechanisms of capitalist production and power, thus actualizing the workers’ power in new institutions and organisms.

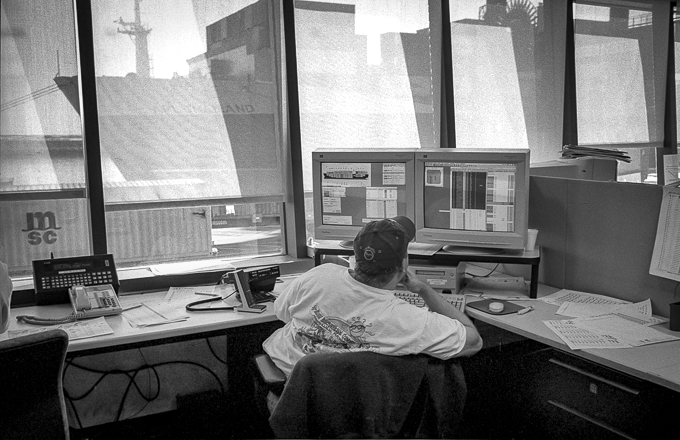

This book, on the other hand, sets out to analyze a different type of workers’ “power” that concerns the ability to block the vital nerve centers of production in order to bend managerial resistance to wage and regulatory demands. In a situation of low unionization, the issue becomes whether a minority of workers in crucial positions can stop both production and profit-making processes. Emphasizing the term minority is hereby essential because this theme plays a central role in the history of all trade union movements.

In pre-Fordist factories, not only did the worker sell their brute physical force but also their skills and competencies, to the point that the more trained and qualified the workers were, the more they became valuable for production. In many cases, this category of workers was seen as a working-class aristocracy with better wages and greater accomodation toward their superiors. Consequently, they were generally viewed as the natural conveyors of reformist consciousness.

Although not entirely, in those years the decision to go on strike depended mainly on the workers’ self-awareness. The German unions, for instance, always kept a keen eye on the exchange market of local goods to understand when their company would receive new orders and become unable to afford a strike that would jam production. This power of the “worker aristocracy” certainly failed within the Fordist organization of production when a new type of worker was established. Such laborers, referred to in Italy as the “mass worker”, did not possess any particular qualifications but exhibited a solid work discipline. As recently as the 50s and 60s, in Piedmont, vast groups of workers who had immigrated from the south to work on the FIAT assembly line fled the factory because they could not bear the rhythms and constraints – i.e., its discipline – and would often end up pursuing a life of crime. Therefore, the laborer’s power depended on their being part of a mass rather than on personal skills. It was the time of large mass unions capable of mobilizing entire industrial sectors and exercising notable political influence.

Today the entire process of valorization of goods has been restructured in keeping with the global market to overcome market bottlenecks by customizing the product, relocating to take advantage of wage gaps, and outsourcing non-productive functions that have become increasingly important. Another effect of this process is the re-employment of workers previously expelled from production in functions such as those indicated above, e.g., in logistics, transforming employees into self-employed workers, and offloading the cost of labor through indiscriminate tax evasion. This reconversion often constitutes a defeat for the trade unions as well as for the political left, as proven by the outcome of several local political elections.

Although the book analyzes many of these points, the interview format does not appear to be the most suitable for expanding the themes dealt with. As global as its vision may be, some ideas within it have unfortunately yet to be developed. Even so, the book’s value and intent primarily suggest effective methods for a trade-union struggle. This also applies to active minorities that are essential to encourage workers to join organized labor. As well as highlighting the need for an accurate analysis of the work processes, with specific reference to the worker’s substantial experience, there comes a solid suggestion to adopt the Network Analysis Methodology typical of the Internet. This approach can accentuate the weight of the connections between the various centers involved in the articulated value chains, i.e., the hubs on which the operation of many nodes depends. Among these, the logistics node emerges pre-eminently, as shown during the historic 1934 strike of the stevedores in the port of San Francisco. Logistics also plays a vital role within the Amazon corporation, i.e., the true bete noire of US trade unionism, both inside the company and in distribution to external customers.

The research on the junctions and bottlenecks on which the unions can act to put the company in difficulty and force it to improve wages and regulations is therefore crucial. It is also interesting that the interventions reported underline the value of involving local communities and organizations. In this regard, I would add that winning a trade-union battle is certainly important but often not enough for the purpose of building a stable and solid support front for labor. The victories of the workers in the crucial nodes must be extended to all workers to prevent the formation of a privileged elite and ensure the continuity of the achievements acquired. The struggles and organizations must aim at the industrial level, not just the professional and the sectoral dimension, ultimately involving the other industries of the sector to contrast the competition coming from companies in the same sector with lower wages. Transitioning from the local to the national level means taking a crucial political step which can grant concreteness to the power of labor making it an active part of industrial policy.

[1] Workers’ Power (Potere Operaio), or PO, rejected the parliamentary politics of the Italian Communist Party (PCI).

Pingback: Nerve Centers - PM Press