Politica di Piazza OO#6

By Peter Olney

Public squares or piazzas play a central role in Italian life. When I arrived in Florence in 1972 I visited some of the small Tuscan towns on the periphery of Firenze and I was a witness to “fare la passegiata”. Literally translated this means “to make a walk”, but in practice is a public ritual in which the townspeople strut their stuff in the public square. Particularly the young engage in ritualized courtship where unattached young men and women parade around arm and arm observing members of the opposite sex. This was not something I had seen on the commons of the cities and towns of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

What happens in piazza is a reflection of the balance of power in Italian society. Poltica di Piazza has its highs and lows. Benito Mussolini was accustomed to addressing huge crowds from a window in Piazza Venezia in Rome during his glory years. Later Il Duce was strung up by his heels in Piazza Loreto in Milano by the partisans at the end of the war of liberation from fascism.

I was mesmerized by a march of 100,000 Italian workers in Rome in 1972 on May Day marching against the war in Vietnam. Workers in their Sunday best, suits and ties, wearing red carnations and carrying flags with the hammer and sickle emblazoned on a red banner filed through Piazza Navona as part of a coordinated nationwide day of protest. I saw in these marchers a physical affirmation of the possibility of radical socialist thinking among working class people. Maybe if history and traditions dictate workers could be won to visions of radical change.

Three personal experiences in “piazza” left strong impressions on a young and ingénue American.

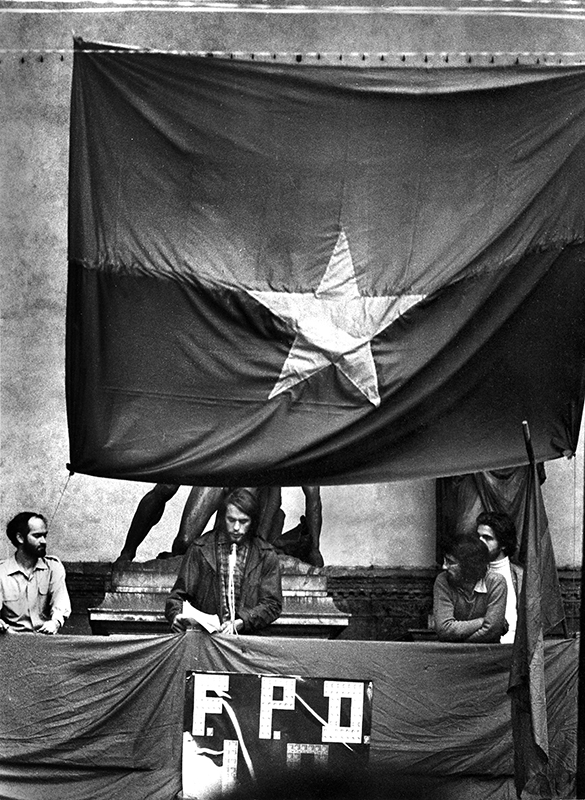

Comizio in Piazza della Signoria – In the spring of 1972 things had intensified in Vietnam both militarily and on the diplomatic front as the talks in Paris to end the war were underway albeit haltingly. In Florence the sizable American ex pat community decided that it wanted to demonstrate publically against its own government’s criminal war. We connected with an array of extra-parliamentary political forces ranging from Grupo Gramsci to Potere Operaio and enlisted their aid to stage a rally in the main square, Piazza della Signoria where the famous replica of the David statue stands in front of Loggia dei Lanzi and the Gli Uffizi. The planning meetings were a spectacle and for us Americans kind of like being a spectator at a tennis match where we would sit and watch the Italians of all different political stripes debate back and forth the merits of including this group or that in the rally.

“I got to spend a weekend in Torino and met all of the ten Trotskyists in Italy”

Each planning meeting would open with a salute to the “Compagni Americani” and then degenerate into a heated debate over their domestic differences. It was agreed that an American should make one of the speeches in English and I was designated to speak. I found a poster on the walls of the Universita di Firenze and copied down the demands from the poster and incorporated them into my written speech. My time came and I spoke in English from the stage and looked at a Piazza full of Italians sitting in the square with the American contingent huddled in the back of the square as giant water tanks were massed with helmeted caranbinieri to deal with crowd control. I delivered my speech and arrived at my dramatic climax proclaiming the demands I had pulled off the agitational poster: No more guns, no more bombs, troops out now! There was dead silence from the crowd, which I of course attributed to language difficulties so I awaited the translator’s work and figured my punch line would yield explosive cheering and applause. Instead there was again dead silence even after my words were delivered in Italian. I was befuddled but as I was climbing down from the stage two Italian men approached me. They rushed to me and exclaimed, “Compagno de la Quarta Internazionale”! They hugged me and invited me to visit the headquarters in Torino later that month. Evidently I had purloined my punch line from a Trotskyist poster in the university and they had identified me as an American Trotskyist. I got to spend a weekend in Torino and met all of the ten Trotskyists in Italy. I also learned that the level of Italian political sophistication was way beyond anything I had heretofore experienced. Finally I learned that in public speaking it helps to know your audience.

Festa dell’ Unita – Unita was the paper of the Italian Communist Party (PCI). It was a daily newspaper replete with sports, culture and coverage of world events and local happenings. Each year in the late spring the Communist Party would hold Feste del’Unita to flex their public muscle in piazza and raise funds. That spring I was invited (my political missteps in La Signoria notwithstanding) along with another American to address a Festa event in Pontasieve, a working class suburb of Firenze. Pontasieve like many of the Tuscan towns was as stronghold of the PCI and like many of the comparable hill towns had a street named Via della Resistenza in honor of the partisan fighters against Mussolini. My American companion was asked to sing and broke out “Where have All the Flowers Gone?” I said a few words about the fight for peace. Then an Italian worker and PCI member addressed the crowd and thanked us for our interventions. He then went on to describe in detail the troop movements of the National Liberation Front (NLF) in Vietnam and the military victories they were winning over the over the Americans and the ARVN. Again I was astounded at the level of training and political sophistication and the radically different world view of these Italian workers.

Chain Gang a Roma – In June of 1972 I traveled to Rome to visit some friends who lived near the University. It was a warm Roman day and I was wearing what is referred to as a guinea tee shirt. On one side of the shirt I was wearing a large Lenin pin and I was carrying a copy of the daily paper of Lotta Continua. I was walking in the section of the University where the Law Faculty was located which I l quickly discovered later was a home base for fascist student groups. Evidently the day I found myself at the law school, a communist in Salerno in Southern Italy had attacked and killed a fascist in a street protest. This was a national event and so the fascist gangs were out for revenge. As I walked the sidewalk I was approached by a group of ten Italian men carry chains. They spotted me and began to shout derisively, “Ciao Compagno.! I hurriedly crossed street into traffic to cut off a part of the gang, but when I got to the other side of the Viale there were still five of them coming at me. One of them must have been designated for this assignment as he started to twirl a heavy motorcycle chain over his head as he moved on me. My adrenaline was rushing so I marched right at the man held up my arm and managed to block the chain and wrest it away from him. I was left there standing holding the chain as the carabinieri approached us. The fascists started to shout that the Communist had assaulted them and that I should be arrested. I will never forget watching a young Italian father with his wife and baby in a carriage rush at the police and start yelling at them to pursue the fascists and arrest them because he had been a witness to everything that had happened. The police backed off as a crowd started to gather, and the family man harangued them. I was allowed to go on my way.

My experience in the public square, my politica di piazza left me admiring the courage and potential sophistication of the working class. I was ready to go home and see whether we could add some Italian sugo to the American political mix.

Next: Living with the Lumpen and making NECCO Wafers

Peter, This is amazing. I love all the details. It’s like you put us right there . This writing is the best so far.

It must have been very exiting days for you. People used to get together in the streets during the “cold war” days and vent their opinions about local and world politics. We still practice it electronically which unfortunately is not able to deliver the passion of a live gathering. As societies become more affluent we have no time for these live meetings and are unable to experience its outcomes. Passion is missing.

Peter these are really a treat-after knowing you for years I realize that I have never gotten the full flavor (the pic is outrageous!) I really see a book here-there is something about the casual flow of the prose, the humor and adventure and the politics that really works. All I can say is that I am glad that you plan to keep writing–I plan to keep reading

Peter,

Such an exciting life in Italy. Lucky we didn’t have to bail you out.

I’m enjoying your posts.