Womack’s Labor Power and Strategy

By John Bowman

Labor Power and Strategy, order from: PM Press

Let me start with a confession. I am not affiliated in any way with organized labor or the labor movement. I have spent over 60 years as an editor of non-fiction works—American history, baseball history, art books, photography books, etc. That said, starting in my early teens I was expected to work at household chores (rolling coal ash can out to curbside, hanging storm windows). On my college vacations, one year I worked at a summer resort, another at the Monsanto chemical plant (then in Everett, Massachusetts, where the Encore casino now is), and another summer at a leather tannery in Woburn, Massachusetts (later charged with pollution—told in the book and movie, A Civil Action). And meantime, as a devoted reader of newspapers all my life, I have certainly kept up with the labor movement in our country.

In fact, indulge me in a personal tale that involves two items on my cv above. For some reason the tannery workers seemed to belong to the United Electrical Workers union (UE), then regarded as one of the more leftish, more radical unions. Every Friday a big stack of the union’s newspaper would appear. I watched to see if the workers would take an interest in the paper, but no—they grabbed a copy and wrapped their dirty clothes in it to take home to be laundered. I seemed to be the only guy who read it. So let’s say I write this as a fairly well informed American with a more than passing interest in the subject matter of the book under discussion.

The book is Labor Power and Strategy by John Womack Jr.—the highly respected Harvard professor and authority on the Mexican revolution. But although he is credited as the author, its two editors—Peter Olney and Glenn Perusek—played a major role in assembling the book, first by interviewing Womack for his contribution. Since the interviews took place in the Foundry, a restaurant in Somerville, MA, they are sometimes referred to as “The Foundry Interviews.” The editors then enlisted the ten individuals who contribute their responses to Womack’s extensive thoughts on the book’s subject—how to identify union power and use it—almost all with firsthand experience as union organizers and union actions. And by the way, not always agreeing with Womack—which is what makes this book especially engaging–and relevant. It is not just some Harvard professor’s highfalutin theoretical treatise.

It is a relatively small book –both in its page-size and page-numbers—but it is full of stimulating–and often provocative–ideas about the labor movement in our country over the last century and—above all– where it should be heading in the present century. If the book can be briefly characterized, I can do no better than quote the words of the historian Nelson Lichtenstein in the front of the book, where he poses the question at the heart of the book: “Are workers with vital skills and strategic leverage the key to a labor resurgence, or should organizers wager upon a mobilization of working people whose relationship to the economy’s commanding heights is more diffuse?”

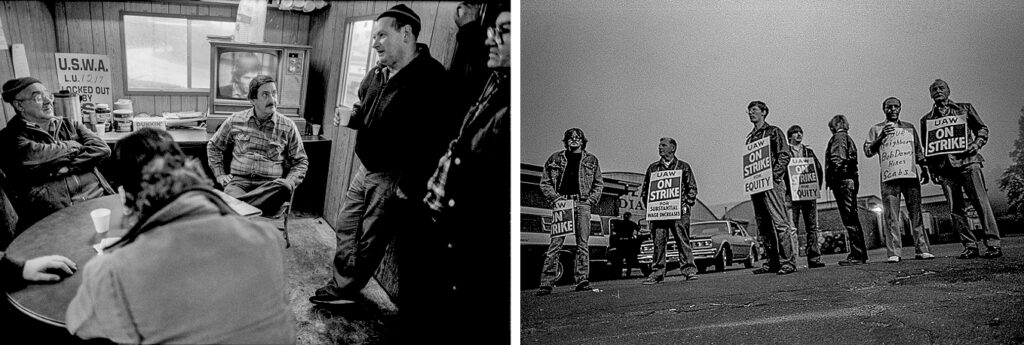

In the course of the book, this is sometimes compressed to the structural vs. associational approach, and if Womack comes down on one side, it is the former. Structural in this instance refers to labor activists, union organizers, primarily going into the actual workplaces and seeking out what are called “choke points” — those crucial locations or processes that if stopped would bring the entire factory, workplace, delivery service, whatever, to a halt. The most prominent example of this is actually cited by one of the responders to the book—Gene Bruskin, who headed the campaign to advance the union’s demands at the Smithfield pork processing plant in Tar Heel, North Carolina. He describes how they identified a particular “choke point” in the process of converting live pigs into pork products and by ceasing to work there, a contingent of workers brought the whole operation to a halt. Their secondary demand focused on another “choke point” – where the trucks delivering the live pigs had to be unloaded.

A ”Womackian” analysis of the Smithfield case would stress that what was at work here was a structural approach: you just go straight into the workplace and disrupt the operation. But Bruskin explains that he also involved elements of the associational approach, launching a field campaign in the surrounding communities, seeking broad public support. And in fact, neither Womack himself nor any of the ten responders is an absolutist—all concede something to the opposing approach. Bruskin’s account of the Smithfield case—2005-2009—is the most detailed account of a specific union action, but numerous examples of such are cited, from the 1919 steelworkers strike to the 1930s automakers strikes, to the more recent strikes by West Virginia teachers and organizing among Nissan workers in Canton, Mississippi, and casino workers in Las Vegas.

I myself have a minor quibble with the book—or rather to Womack’s responses to the interviewer. He does go on, despite what I say above, with his theoretical ideas. And I might have wished that he discussed in a bit more “grounded” detail five of the factors that I, at least, see as bearing greatly on the labor movement in the decades ahead: the role of the waves of uneducated immigrants, the role of robots, the role of the Chinese, the role of electronification of work, and the role of the “gig” economy. But that’s for a different book–and perhaps a different author. This is Womack’s book. And if I, the individual described at the outset, can find it so enlightening and so engaging, then I think that anyone should appreciate reading it

.…

Please join us at one of a number of Labor Power and Strategy upcoming events with John Womack Jr. and contributors

Pingback: Womack’s Labor Power and Strategy - PM Press