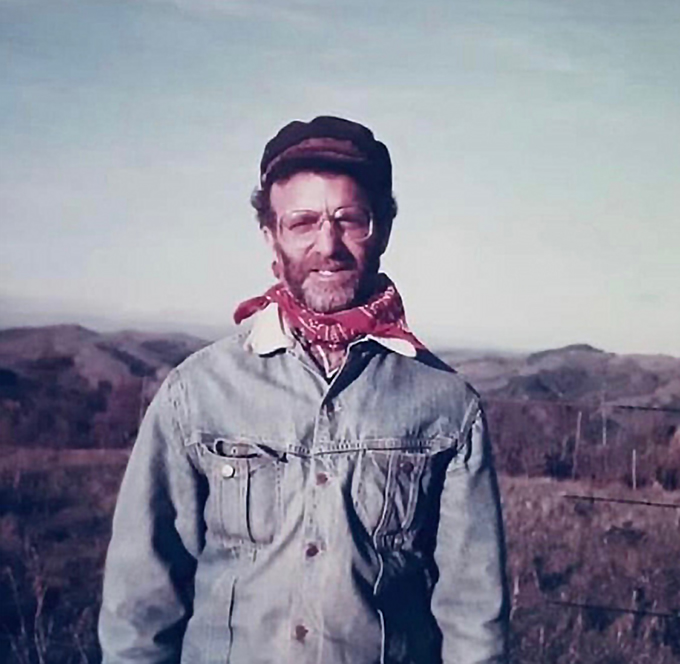

Peter Haberfeld (1941-2021)

By Steve Bingham

Peter Haberfeld, a lawyer for the people and community organizer, died of a heart attack at his home in Oakland on December 1, 2021. He was 80 years old. After earning a law degree at the University of California, Berkeley, Peter embarked on a life of activism as a lawyer and labor and political organizer.

As a law student in 1966, Peter worked in Albany GA for C.B. King, the pioneering civil rights attorney and only Black lawyer in Southwest Georgia. King deeply influenced Peter, firming up his determination to use the tool of the law to defend those who are marginalized, abandoned and powerless.

Between 1968 and 1975 Peter was an attorney and organizer in the California Central Valley, providing legal aid to Latino youth and farmworkers. In 1975, he joined the United Farm Workers legal staff, part of the legendary battle for farm worker union recognition. He was influenced by iconic leaders Cesar Chavez, Dolores Huerta and his mentor, renowned union organizer Fred Ross, Sr. Peter helped win the landmark, Murgia v. Municipal Court, which successfully limited racially discriminatory prosecution of defendant UFW members.

Peter was the first staff person hired to run the new office of the San Francisco Bay Area Chapter of the National Lawyers Guild. He worked at the Youth Law Center, California Rural Legal Assistance and the Bar Sinister legal collective in Los Angeles. His audacious combination of lawyering and organizing incurred the wrath of the conservative legal and political establishment everywhere he went. When Governor Ronald Reagan tried to defund CRLA, he specifically cited Peter’s legal work, including his involvement with the Black Panther Party in Marysville.

Peter later organized and advocated for back-to-the-land folks in Shasta County. He was a lawyer for the California Department of Industrial Relations, the state Occupational Safety and Health Agency, and the Public Employment Relations Board. He later became a union organizer for teachers in Fremont, Oakland (Oakland Education Association) and Vallejo. He then worked for the Oakland Community Organization, organizing teachers and parents for school reform in Oakland. Peter fought his final court battles at the law firm of Siegel & Yee including an epic case that ensured the survival of the National Union of Healthcare Workers.

Peter was proud of his record of four arrests:

– During the 1964 Berkeley Free Speech Movement

– While serving as a poll watcher during the election campaign of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party to elect candidates to the state’s legislature in 1967

– At People’s Park in 1969

– And with his wife Victoria Griffith in San Francisco protesting the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq

Throughout his life, Peter was always ‘presente’ to ‘fight the good fight’ against abuses of power – in occupational safety, school reform, civil rights and more. Peter worked well into retirement, volunteering on Barak Obama’s and Bernie Sanders’ presidential campaigns as well as helping friends and family with legal needs.

Peter, whose Swiss and Austrian parents escaped the rise of Nazism, was born in Portland, OR on October 23, 1941 eight minutes before his identical twin and grew up on his family’s farms in Oregon and rural Los Angeles. He attended Reed College and the University of California Berkeley School of Law. He was admitted to the California Bar in 1968.

Peter was a lifelong learner — deeply engaged with the world and people around him. In recent years, he and his wife Tory traveled and lived in South America. He wrote until the very end of his life on political issues in Cuba, Venezuela, Ecuador, Bolivia, Argentina, Peru and most recently France where he and Tory spent a very special time together in Montpellier and on a small farm.

Peter, whose early years were spent on his family’s farm, returned to farming in France – harvesting olives, caring for sheep and horses and milking cows while “Wwoofing” (World Wide Opportunities on Organic Farms). Peter and Tory lived off and on in France for the last four years of his life. He spent time with his two daughters and granddaughters there, which delighted him.

Peter summed up why he wrote this past year a detailed unpublished memoir of his lifelong engagement in ‘good trouble.’ With modesty, he wrote: “If [it] …appears as though I consider myself a hero or a major player in any way, I do not. I have described my experiences merely to convey what was happening during the period and how I participated.”

Peter is survived by his wife, Victoria (Tory) Griffith with whom he shared a passion for political organizing, his daughters Demetria (Demi) Rhine of Oakland and Selena Haberfeld Rhine of New York; two granddaughters, Marina and Alexa Escobar; the mother of his daughters, Barbara Rhine of Oakland; his ex-wife Dorothy Bender of Palo Alto; his brother Steven (Rena), living in Israel; his sister Mimi Haberfeld, living in Mexico; many nieces and his mother-in-law Marilyn Griffith of Redwood City.

Peter was dearly loved and will be terribly missed by legions of people who admired his gutsy and creative lawyering and organizing as well as the many who considered him central to their lives, for both personal and political reasons. A memorial will be planned for the spring. Donations may be made to The East Oakland Collective, an organization that Peter supported which addresses the needs of unhoused people in East Oakland.

Peter beautifully summed up what motivated him to be the always-engaged political person that he was in this letter he wrote to the son of one of his oldest friends. It’s well worth the read, especially for young advocates wondering whether anything they do in life will make a difference in people’s lives.

Dear Dylan:

What I say here is not to try to convince you that you and your dad are wrong to articulate doomsday visions of our future. I do not know how things will turn out and I will be long gone as all the evidence comes in. Simply, I will tell you what motivates me.

Something in my background has caused me to be an activist. Perhaps it is because my parents taught us that if an injustice exists, big or small, do something about it.

My involvement has always made me optimistic. I stood alongside many of my generation who fought for civil liberties, civil rights, and an end to injustices. I met people who were courageous, who dared speak and fight for a better future. I felt our collective power and saw that positive change can come about without a majority being mobilized. It was sufficient that well-intentioned, hard-working activists took a stand.

The Civil Rights Movement sacrifices led to improvements, growing consciousness, and access by young people to the college education that prepared them to become important scholars, writers, commentators. It is they who are developing a new and improved narrative for the present Movement and that which will come.

The Farm Workers Movement awakened the Chicano Youth. It put in motion the Latino leadership that has taken over in California to make it a Democrat-run State. Our State, as deficient as it is, is still a beacon to the residents of Mississippi and other slave states as well as the fly-over states.

The Women’s Movement has transformed the consciousness about women’s equality. It has led young women to become doctors, lawyers, leaders in all spheres, who have begun to influence how people perceive their living conditions. It still has a way to go to bring about wage equality and an end to physical and sexual abuse. But you cannot deny the progress that came about because people fought for something better.

You can say the same about the LBGT Movement and same sex marriage. The quote from Frederick Douglass about “not getting anything unless you fight for it” is still relevant. The totalitarian control and exploitation of millions of slaves would be with us today if it had not been for the minority of the population who fought it and moved the country to a new, although still unacceptable, stage.

The anti-War movement trained activists to understand the dangers of a fascist takeover of the US, now in police departments. Hopefully, soon they will oppose US Imperialism. We helped stop the imperialist expansion in Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, and other places our misleaders would have taken young US soldiers had it not been for the “Vietnam Syndrome”, had it not been for the people my twin brother now refers to as the “peaceniks” who thwarted the glorious war mongers.

My association with activists has made me an optimist. I have learned to combat my cynicism and pessimism by going to work with people who share my perspective. Recently, for example, as I sat in a meeting of 25 people on a Sunday morning talking about what brought us to go into the precincts to talk with voters about Bernie, I was excited to be connected to intelligent, well-informed, life affirming people who dared to win and risked to lose.

People like us who have grown up in bourgeois settings, satisfying our desires with material goods, embrace a mentality that is less prevalent farther down the economic ladder. We expect that all we have to do is make up our minds and become the person we imagine. We believe that there will always be progress. Our view is very short term. We have come to expect immediate solutions. We have a rough time adjusting to negative events. We have to, instead, see that history plays out over a long period, and that what is important in our lives is to be pushing for change to happen as quickly as possible.

Handwringing gets us nowhere. In fact, it is too often a pastime people use to excuse their lack of courage to fight for something better. It is appealing to reach a negative conclusion. If it is all bad, has always been bad, and will always be bad, only stupid (or unrealistic) people get involved in the struggle for something better. And they miss the exhilarating experiences of joining others who have the courage to face the negative forces by marching, petitioning, talking with others, and organizing collective power among the people to confront the wealth and military power of the fascists.

I have organized teachers strikes among other actions. This takes a long time. People must develop a consciousness about what is bad and what could be better. Then, they must conclude that there is no other acceptable choice but that of fighting for what is right, risking losing, losing pay, being scared, offending people who decide to break the strike. The job of the organizer is to lead people through a set of experiences that develops that consciousness.

It teaches us to view current political events through the lens of an organizer. We have to look at what is going on in the US as a consciousness-building experience. We challenge the police for what they do to unarmed young men and women of color. They respond by revealing their violence-prone nature. A shift is occurring, and the participants see that it is a product of their effort. They want more victories. Their demands become more far-reaching. Their analysis of the problem becomes more profound. Others, initially bystanders, join the effort. There is a payoff from viewing the glass as half filled, not half empty: we see what works, where we have to go from here, and we enjoy being hopeful, even if the next turn in the road is negative.

The only alternative is the unacceptable one of going passively to the slaughterhouse. That does not appeal to me as a fulfilling way to live.

(Have you read “the People’s History of the US” by Howard Zinn and “People’s History of France” by Gerard Noiriel? I think that they make the point much better than I can ever hope to do.)

You have talent and skills to help tell the story that combats the narrative of the forces in power. I look forward to a film that makes that kind of mark and to Jean’s advertising campaign that raises people to a higher level of consciousness and greater readiness to take on the people’s enemies.

Love to you dear comrades

Peter

…