Enough!

By Robert Gumpert

While Trump again played golf, isolating himself at taxpayers’ expense in the plush confines of his Florida retreat, all across the United States tens of thousands of people marched in support of “Families Belong Together” and called shame on the Trump administration and its actions.

Demonstrators called for the immediate return of children to their families and stressed the importance of the November elections if there is to be a change in the direction the country has taken.

All photos are from the June 30th San Francisco, CA. demonstration where thousands marched from Dolores Park to City Hall.

Voices from the demonstrators in SF

“I’m here today to represent all the immigrants that came before me, all the immigrants that have gone through this in the past and to say never again. What’s going on today is one of the most shameful and un-American displays governance in our country’s history and we must not stand for it. We must stand against it. At the end of the day it is our responsibility to right those wrongs. That’s why I’m out here today.”

Tim

“I’m here because I am against everything Trump is for.”

Charlotte

“It’s unfair and it’s soul crushing to know that America was founded on immigrants and for Trump to separate children from their families. We’re not going to standby and let him do whatever he wants with these children. (He’s) traumatizing the kids. We’re going to show him that we’re not going to standby let him do whatever he wants with these children.”

Adrianna

“I’m here to show support for all the organizations that are working endlessly to support the children and to learn how I can help”

Ella

“I’m here because we have to stand together to change America and make it great again. We’re losing it. We’re losing our democracy, we’re losing our freedoms. We have a person in the White House who ignores the Constitution. We just cannot be silent anymore.”

Judith

“I’m here because I just can’t watch and listen to this anymore. This (the demonstration) is what democracy looks like. We have experience, and the experience is we work together. We work to make America great. I’m sorry for the people who think they’re disenfranchised but we’re losing America to this guy.”

Mary

“Another important aspect of this march is we have to vote in people that are willing to compromise and work towards a common good. That means the Senate, the Congress; they have work towards a common good. Not just for work for reelection, but towards the common good for the American people and the global community.”

Mary

I’m here to support the many immigrants and also the countries that are affected by this ban.

Ammar

“YOU CAME HERE TO SUFFER” The H-2A Farm Worker Program creates a pipeline of cheap, disposable labor

By David Bacon

L) ROYAL CITY, WA- A sign on the gate restricting access to the barracks in central Washington housing contract workers brought to the U.S. by growers under the H2A visa program by the Green Acres company. R) YAKIMA, WA- Members of the Yakima Nation of Native Americans join farm workers and other immigrants and community and labor activists marching through Yakima to celebrate May Day. Photos copyright David Bacon

On August 6 of last year, Honesto Silva Ibarra died in a Seattle hospital. Silva was a guest worker-a Mexican farm worker brought to the United States under contract to pick blueberries. He worked first in Delano, California, and then in Sumas, Washington, next to the Canadian border. His death, and the political and legal firestorm it ignited, has unveiled a contract labor scheme reminiscent of the United States’ infamously exploitative mid-century Bracero Program.

In a suit filed January in the U.S. District Court in Washington State, the state’s rural legal aid group, Columbia Legal Services charges that Silva’s employer, Sarbanand Farms, “violated federal anti-trafficking laws through a pattern of threats and intimidation that caused its H-2A workforce to believe they would suffer serious harm unless they fully submitted to Sarbanand’s labor demands.”

Those demands, as described in the complaint, were extreme, and Silva’s coworkers believe he died as a result.

Sarbanand Farms belongs to Munger Brothers, a family corporation in Delano, California. Since 2006, the company has annually brought more than 600 workers from Mexico under the H-2A visa program to harvest 3,000 acres of blueberries in California and Washington. Munger, the largest blueberry grower in North America, is the driving force behind the growers’ cooperative that markets under the Naturipe label.

Companies using the H-2A program must apply to the U.S. Department of Labor, listing the work and living conditions and the wages workers will receive. The company must provide transportation, housing, and food. Workers are given contracts for less than one year, and must leave the country when their work is done. They can only work for the company that contracts them, and if they lose that job they must leave immediately.

According to the lawsuit complaint, workers were told that they had to pick two boxes of blueberries an hour or they’d be sent back to Mexico. In July and August, they were working twelve-hour shifts. The complaint says managers routinely threatened to send them home if they failed to meet the quota, and to blacklist them afterwards, preventing them from returning to the U.S. to work in subsequent years. One manager told them, “You came here to suffer, not for vacation.”

Laboring in the rows under the hot sun, breathing smoke in the air from wildfires, many workers complained of dizziness and headaches. Nidia Perez, a Munger supervisor, purportedly told workers that “unless they were on their death bed,” they could not miss work. Silva told a supervisor he was sick. The company, in a statement, said he had diabetes and “received the best medical care and attention possible as soon as his distress came to our attention.” But fellow worker Miguel Angel Ramirez Salazar, gave a different account: “They said if he didn’t keep working he’d be fired for ‘abandoning work,’ but after a while he couldn’t work at all.”

Silva collapsed, was taken to a local clinic, and then to the hospital where he died. CSI Visa Processing, the firm that recruited the workers in Mexico for Munger, later posted a statement on its website, saying “the compañero who is hospitalized, the cause was meningitis, an illness he suffered from before, and is not related to his work.” Nidia Perez was the liaison between Munger Farms and CSI.

While Silva was in the hospital, sixty of his coworkers decided to protest. On August 4, they stayed in the labor camp instead of leaving for work. In addition to the production quota, they were angry about the food. The complaint says they were being charged $12.07 a day for meals, but the food sometimes ran out. When workers were fed, a supervisor marked their hands with “X” so they couldn’t go back for more. They were forbidden to eat in the fields.

As the protestors sat in the camp, one worker called the Department of Labor, which sent out an inspector. The next day, when they tried to go back to work, company supervisors called out strikers by name and fired them for “insubordination.” Perez told them they had an hour to get out of the labor camp before the police and immigration authorities would be called. Supervisors stood in front of the barracks, periodically calling out how much time was left.

Workers set up an impromptu encampment nearby with the help of Washington State’s new farm worker union, Familias Unidas por la Justicia. After a few days, all eventually had to return to Mexico.

The death and firings at Sarbanand Farms highlight the explosive growth of this contract labor program. In 2006, U.S. employers were certified to recruit 59,112 workers under H-2A visas. Washington State certified only 814 H-2A positions that year. But by 2015, the numbers had mushroomed. Nationally, employers were certified to bring in 139,832 workers, including 12,081 in Washington State alone. Last year, Washington accounted for 18,535 workers out of 200,049 nationally.

Driving this growth are some very big operators. CSI (Consular Solutions Inc.), the recruiter for Munger Farms, is probably the largest single recruiter of H-2A workers from Mexico. The company, originally called Manpower of the Americas, was created to bring workers from Mexico for what is today the largest H-2A employer-the North Carolina Growers Association. The group was founded in 1989 by Stan Eury, who formerly worked for North Carolina’s unemployment office, which plays a role in H-2A certification. Eury also created the North Carolina Growers Association PAC, a political action committee that donates almost exclusively to Republicans.

Under pressure from Eury, courts have concluded that anti-discrimination laws don’t apply to H-2A workers. Employers are allowed to recruit men almost entirely. In 2001, the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the Age Discrimination in Employment Act does not cover workers recruited in other countries, leaving employers free to give preference to young workers able to meet high production quotas. In 2009, he challenged Obama Administration efforts to strengthen H-2A worker protections.

North Carolina Legal Aid battled Eury for years over complaints of wage theft, discrimination, and bad living and working conditions, until he signed a collective bargaining agreement with the Farm Labor Organizing Committee in 2004.

Despite his political clout, in 2015 Eury was forced to plead guilty to two counts of defrauding the U.S. government, fined $615,000 and was sentenced to thirteen months in prison. Nevertheless, the North Carolina Growers Association has been allowed to continue; last year, the Department of Labor approved its applications for 11,947 workers.

Meanwhile, CSI became a recruitment behemoth, supplying workers far beyond North Carolina. Its website boasts that it recruits more than 25,000 workers annually, through its network of offices in Mexico. A CSI handout for employers says “CSI has designed a system that is able to move thousands of workers through a very complicated U.S. Government program.”

Workers recruited through CSI must sign a form acknowledging that their employer can fire them for inadequate performance, in which case they will have to return to Mexico. “The boss must report me to the authorities,” it warns, “which can obviously affect my ability to return to the U.S. legally in the future.”

Joe Morrison, an attorney with Columbia Legal Services, notes that H-2A workers are inherently vulnerable for several reasons. “Virtually all have had to get loans to support their families until they can begin sending money home, as well as to cover the cost of visas and transportation,” he explains. “That basically makes them indentured servants. They have the least amount of legal protection, even less than undocumented immigrants.”

H-2A workers are also excluded from the Migrant and Seasonal Agricultural Worker Protection Act and beholden to one employer. “Even undocumented workers can vote with their feet if they don’t like the job,” Morrison says. “If H-2A workers complain, they get fired, lose their housing, and have to leave the country.”

Many H-2A workers feel conflicted about their situation.

“We have papers, so we don’t feel in danger,” said Jose Luis Sosa Sanchez in a recent interview, at in a camp belonging to Stemilt Growers near Royal City, Washington. But he and other workers can’t buy property and establish a sense of connection to the community.

“We just come to work. That’s all,” he says. And there is no time-and-a half for working more than eight hours. “We work six days, and sometimes seven. And the work here is hard. You’re really exhausted at the end of the day.”

Sosa expressed sadness over being separated from his family, including two young daughters. “It’s hard to be far away from them, but what can I do? To move ahead I have to do this. So I talk with them on the phone. What else can I do? Every three days or so, in the afternoon after work. My wife says she feels OK, but who knows?”

Sergio Alberto Ponce Ponce, staying in the same barracks, had similar feelings. “I miss my wife. I’ve never been apart from her before. We sleep in each other’s arms, but here, no. I call her every day. She’ll send me a text, and then I’ll call her the next chance I get-in a break at work or at lunch, and when I get back after work before it gets dark.”

Ponce looked forward to going home to Mexico, but plans to return. “I’m going to keep working like this for as long as I can,” he says. “I’d like to live here, but I have my family there.”

In 2013, representatives of the Washington Farm Labor Association, originally part of the Washington State Farm Bureau now called WAFLA, showed up at a large Washington State winery, Mercer Canyons. Garrett Benton, manager of the grape department and viticulturist, was then given a plan by the company owners for hiring workers for the following season.

“The plan separated out work to be done by the H-2A workers and work to be done by the local farm workers,” Benton recalled in a declaration for a suit filed by Columbia Legal Services. “It left very little work for the local farm workers. Based on the plan and the presentation by the WAFLA people, I believed it was a done deal that the company would be bringing in H-2A workers in 2013.”

The rules governing the H-2A program require employers to first advertise the jobs among local residents. Local workers must be offered jobs at the same pay the company plans to offer H-2A workers, and the H-2A workers must be paid at a rate that supposedly will not undermine the wages of local workers. That wage rate is set by the unemployment agency in each state, and is usually slightly above minimum wage.

But there is virtually no policing of the requirement that growers demonstrate a lack of local workers, or any efforts to hire them beyond a notice at the unemployment office.

Benton said many of Mercer Canyons’ longtime local workers were told there was no work available, or were referred to jobs paying $9.88/hour while H-2A workers were being hired at $12/hour. The company, he said, even reduced the hours of those local workers it did hire in order to get them to quit.

“Working conditions got so bad for the local workers that they eventually went on strike on May 1, 2013,” Benton stated. “They felt strongly that they were being given harder, less desirable work for less pay…. Mercer Canyons was doing everything it could to discourage local farm workers from gaining employment.” The class-action lawsuit involving more than 600 farmworkers was settled a year ago, and Mercer Canyons agreed to pay workers $545,000 plus attorneys’ fees, for a total of $1.2 million.

In central Washington, the barracks springing up for H-2A workers all look the same-dusty tan prefab buildings built around a common grass area. Billboards next to rural roads advertise the services of companies including “H-2A Construction Inc.” This is a product of WAFLA’s aggressive growth strategy.

“Our goal is to have 50,000 H-2A workers on the West Coast three years from now,” WAFLA’s director Dan Fazio told Michigan apple growers in 2015. In 2016, the group took in $7.7 million in fees for its panoply of H-2A services. It handles program application and compliance, provides transportation, recruits workers and gets their visas processed, and conducts on-site meetings with them.

The premise behind the H-2A program is that it allows recruitment of workers by an individual grower who demonstrates it can’t find people to hire locally. Workers are then bound to the grower, and don’t function as a general labor pool. But a labor pool is exactly what WAFLA advertises.

L) ROYAL CITY, WA- Barracks under construction in central Washington built to house contract workers brought to the U.S. by growers under the H2A visa program. R) YAKIMA, WA- The hands of Manuel Ortiz, who came to the U.S. from Mexico as a bracero in the late 1950s and early 1960s, and spent decades working as a farm worker in California and Washington, show a life of work. Photos copyright David Bacon

WAFLA’s “shared contract model” lets multiple growers share the same group of workers during the same harvest season. Workers might work for one grower one day, and another the next, at widely separated fields. The “sequential model” lets growers bring in workers for one harvest, and then pass them on to another grower for another harvest.

In its annual report for 2014, WAFLA boasted about helping block a proposed Department of Labor rule to make employers who use the H-2A program provide housing for family members of domestic workers. “Can you imagine a worker with a family of six demanding housing for his family a month after the start of the season when nearly all beds are full?” it asked.

WAFLA has a close relationship with the Washington State Employment Security Department. Craig Carroll, the agency’s agricultural program director overseeing H-2A certification, spoke at the group’s “H-2A Workforce Summit” in January 2017, sharing the stage with numerous WAFLA staff members and Roxana Macias, CSI’s director of compliance. Macias herself worked for the department for two years, and then for WAFLA for three years, before moving to CSI.

While the Employment Security Department is charged with enforcing the rules regarding H-2A contracts, its website states: “The agriculture employment and wage report will no longer be provided beginning with the May 2014 report due to a decline in funding.” The department did request an investigation by the state attorney general into charges by Columbia Legal Services that WAFLA had tried to fix wage rates at a low level. That investigation is still pending.

Washington State also helps WAFLA by allowing it to use state subsidies for low-income farm worker housing to build barracks. This includes the ninety-six-bed Ringold Seasonal Farmworker Housing in Mesa, Washington. Subsidies were used to build another grower association’s $6 million, 200-bed complex called Brender Creek in Cashmere, Washington.

Daniel Ford at Columbia Legal Aid complained about these handouts to the Washington Department of Commerce, noting that the state’s own surveys showed that 10 percent of Washington farm workers were living outdoors in a car or in a tent, and 20 percent were living in garages, shacks, or “places not intended to serve as bedrooms.” Corina Grigoras, the department’s Housing Finance Unit managing director, responded that she couldn’t “prohibit H-2A farmworkers residing in housing funded through the Housing Assistance Program,” or even “require that housing assistance program housing be rented to H-2A employers only at market rates.”

Rosalinda Guillen, executive director of Community2Community, a farm worker advocacy organization in Bellingham, Washington, says “the impact of this system on the ability of farm workers to organize is disastrous.”

In 2013, when Sakuma Brothers Farms’ longtime resident workers went on strike for at least $14 an hour, they were told that the company would not exceed the H-2A wage rate of $12.39. In effect, the guest worker rate was used as a ceiling to keep wages from going up. Familias Unidas por la Justicia was organized during that strike. Its president, Ramon Torres, met the H-2A workers Sakuma had hired, “they said that they’d been told that if they talked with us they’d be sent back to Mexico,” he remembered.

After the 2013 harvest, strikers received form letters telling them they’d been fired. Sakuma Brothers Farms then applied for 438 H-2A workers, enough to replace its entire workforce, saying it couldn’t find local labor. Familias Unidas collected letters from the strikers saying they were available to work, and turned them in to the Department of Labor. Sakuma Brothers Farms withdrew the H-2A application, and had to rehire the strikers. Because the workers saved their jobs, the union survived and finally signed its first contract last year.

After the events last year that led to Silva’s death, workers at Sarbanand Farms reached out to the new union and joined it during their protest. But Sarbanand insists that H-2A workers have no such organizing rights, saying in a statement: “Their H-2A employment contracts specifically state that they are not covered by a collective bargaining agreement, and H-2A regulations do not otherwise allow for workers engaging in such concerted activity.” The statement added that when employees quit or are terminated, “the employer is not responsible for the worker’s return transportation or subsistence cost, and the worker is not entitled to any payment guarantees.”

In response to the organizing effort by Community2Community and Familias Unidas, growers launched a website to argue their case. It claims, “The guest worker program provides higher pay for guest and domestic workers, plus the highest level of protection for workers anywhere.” It features a photo of Guillen, accusing her of “outrageous lies against the Sumas farm.” It says Silva died of “untreated diabetes,” of which the company was “unaware.”

While the website conveys a certain desperate tone, most growers seem optimistic about the H2-A program’s future, due in part to the election of Donald Trump as President. While Trump has railed against some guest worker programs, especially the H-1B program used extensively by the high-tech industry, he has been conspicuously silent about H-2A. In fact, Trump’s family employs H-2A workers on its Virginia vineyard. And the H-2A program is popular among some of the most powerful Republicans in Congress, including Representative Kevin McCarthy, GOP House Majority Leader.

“We are very positive about the Trump Administration,” WAFLA head Dan Fazio said at a meeting of his group in early 2017. “I don’t think there is a person in this room who voted for President Trump who wouldn’t vote for him again tomorrow.”

Last fall, U.S. Representative Bob Goodlatte, Republican of Virginia, introduced a bill to expand the H-2A program. The bill, HR 4092, would create an H-2C visa category to replace H-2A, certifying the recruitment of 450,000 workers annually, a cap that would grow by 10 percent a year. Growers could employ workers year-round and re-enroll them for the following year while they are still in the country. Eventually up to 900,000 guest workers could be employed in the United States at any one time. Wages would be based at 115 percent of the federal or state minimum wage, or $8.34 an hour in states with the federal minimum wage of $7.25.

As the Trump Administration beefs up raids and enforcements, growers want to ensure a continued supply of cheap labor.

“ICE does audits and raids, and then growers demand changes that will make H2-A workers even cheaper by eliminating wage requirements, or the requirement that they provide housing,” charges United Farm Workers Vice-President Armando Elenes. “Reducing the available labor and the increased use of H2-A are definitely connected. Growers don’t want to look at how they can make the workplace better and attract more workers. They just want what’s cheaper.”

Published first in The Progressive, June 1, 2018

Populism in Charge in Italy

By Nicola Benvenuti

a prelude to a shift to the right of the European political axis …”

With the intervention of Italian Interior Minister Salvini to prevent the docking in Italian ports of the ship Acquarius loaded with African refugees, the Movimento 5 Stelle (M5S)-Lega government assumes a precise physiognomy. Salvini acts like the Prime Minister dictating the line to the entire government that can do nothing else but follow him (even if the transport minister denies that the ports have ever been closed to Acquarius or other mercy ships).

we must not hide …”

It is obvious for those who have the time and desire to study the affair that Salvini has acted in an irresponsible and improper manner from all points of view, but the shock message he wanted to send, of a change of course on the question of admitting immigrants, seems to have impacted the voters who have shown signs of appreciating his action. And this is also thanks to Spain which has offered to admit the refugees (which lets Salvini say something like “you have seen, if you are hard-nosed, the other countries which so far have denied any admittance, such as Spain, will yield “) French Presdient Macron has called Italian behavior, “repulsive” and has aroused the ire of all political forces in Italy because Macron makes this hard judgement from the pulpit of a country that has closed the borders with Italy to non-EU citizens in the town of Ventimiglia, creating inhumane situations. This is the France whose gendarmes in the Alps hunt down non-EU citizens – and the Italian volunteers who help them go to France. Volunteers whose actions are saving immigrants from certain death, given the freezing climatic conditions and their unpreparedness for such weather.

But we must not hide from the fact that Salvini’s position was welcomed by many voters, and not just on the Right. If the poll by Demos is accurate, 58% of Italians supported Salvini’s action. It should also be remembered that in the recent local elections in which almost 6 million voted, the Lega proved to be rapidly on the rise while the M5S appeared to be in difficulty. According to a recent poll, the Lega would get today 29.2% of the vote (it had 17% in the elections) while the M5S would fall to 29% (it had 32%). This should not be surprising to anyone. The League has been in government, has been administering cities and regions for years, and has solid links with local and national territories and powers. Moreover, having removed the mantle of right-wing leadership from Berlusconi, it is drying up his party, Forza Italia. The M5S is a protest movement, born of the activism of Comedian Beppe Grillo and the “Likes” obtained on social media. Its election victory was probably built by manipulating voters through profiling done by the Casaleggio company. In short, their electoral base is very volatile.

It is also clear that the government was formed with an absolutely contradictory program that assumes huge public spending. The main request of the League, in addition to the request for the expulsion of non-EU citizens, is a flat tax of 15% for companies, first, then for all citizens; while the M5S wants support for the unemployed in some form of citizen income. This proposal has garnered a very high percentages of votes in the southern regions. But the Minister of Finance, Giovanni Tria, almost literally reconfirmed the economic evaluations of the previous center-left government on the impossibility of loosening the public purse for increased public spending. Both Salvini and Di Maio, the parliamentary leader of M5S, have resized their respective positions on the program, but the contradiction remains, and it is very likely that sooner or later the government will suffer. Many observers expect the fall of the government after the next European elections, in May 2019, but if the racist proposals (as of yesterday the proposal to register the Roma – gypsies !!!) of Salvini find support in the population, the League will be moved to cash in on the consensus that could be gained through new elections, and therefore it is hard to imagine this government lasting beyond the autumn.

What is worrisome is the absence of effective opposition. The Partito Democratico (PD) will have to get out of its isolation imposed by Renzi, when he blocked any negotiation with the M5S for a government alliance. Even a completely symbolic discussion would have given the PD an opportunity to speak to the electorate about M5S. That policy of abstention instead has legitimized the embrace of Di Maio with Salvini. It gave up the possiblity of trying to insert a wedge between the two populisms (Right and Left), and to give the PD (whose traditional voters moved in part to the M5S) the image of a party that has passed the right measures laws and policies (A basic social income, containment of immigration, and credit in Europe) Such negotiations would have enabled the PD to position itself as a party that knows also how to engage in self-criticism.

Salvini uses his position as Minister of the Interior to campaign; the M5S, instead, both because of the poor quality of the management team and because of the onerous nature of its economic peoposals, has less visibility and effectiveness in the government. This is why the leaders of the M5S are increasingly restless in the face of the forceful actions of Salvini and fear like the plague any recourse to the polls that would electorally sanction their subordinate relationship in the balance of power with the Lega. The danger therefore is that the M5S becomes more and more under the sway of the Lega, already all powerful in the Center-Right coalition, giving life to a right-wing and authoritarian movement, completely unprecedented in scope in Italy since Liberation and, moreover, endowed with solid sympathies in the rest of Europe.

The formation of a populist government driven by La Lega is in fact strengthening a movement against Merkel and hostile to the Franco-German axis that has guided the European Community in recent years and which is charged with governing immigrant flows by increasing the political and financial engagement in North Africa and distributing that engagement among European countries. This movement, although still lacking a definite alternative platform, sees the Italian Lega-M5S government, populist Austria’s Sebastian Kurz and the Bavarian CSU of the German interior minister Seehofer, committed to a policy of closing borders – already requested by the countries of the so-called Visegrad group (Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia and Hungary) – and as a prelude to a shift to the right of the European political axis.

Requiem for a Steelworker: Mon Valley Memories of “Oil Can” Eddie

By Steve Early

The Stansbury Forum is fortunate to have several contributors who worked on the Sadlowski campaign. The two following pieces, first by Steve Early and second by Garrett Brown, are from two of them.

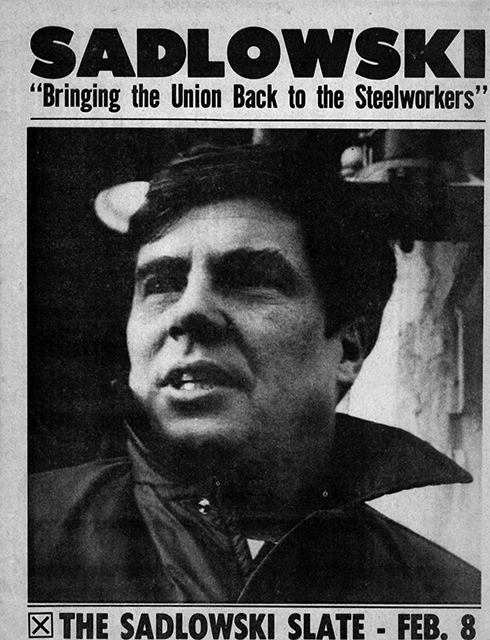

Ed campaigning in Gary, Indiana. Photo copyright: Earl Dotter

In progressive circles in the upper mid-west today, if you’ve heard the name Sadlowski, it’s probably because you were involved in the Wisconsin labor uprising of 2011, where you might have linked arms with AFSCME organizer and state capitol occupier Edward A. Sadlowski. Or maybe you applauded the electoral victory of his sister, Susan Sadlowski Garza, when she won a Chicago city council seat four years later, as a standard bearer for her union, the Chicago Teachers.

Ed, Susie, and their union comrades were up against two would-be union busters, Republican Governor Scott Walker in Wisconsin and Rahm Emanuel, the corporate Democrat who is mayor of Chicago. Now both Sadlowskis are mourning the death of 80-year old Edward Eugene Sadlowski, after what his son calls “a hard struggle” of a different sort. The cause of death, on June 10, was Lewy body dementia, a condition that drove Robin Williams to suicide.

Four decades ago, their father was a really big name in the United Steelworkers (then the USWA), well-known throughout organized labor, and a hero of the labor left. As director of USWA District 31, covering Chicago and Gary, Ed Sadlowski was the elected leader of 130,000 blue-collar workers, part of a USWA membership then totaling 1.4 million, about twice what it is today. In a challenge to authority rare among union officials of his rank, Sadlowski broke with top USWA leaders in Pittsburgh who were too cozy with management. Backed by a campaign network called Steelworkers Fight Back (SFB), he ran for international president on a controversial platform calling for greater union democracy, shop floor militancy, protection of black workers’ rights, and the right to strike.

In the mid-1970s, Mid-western cities were still ringed with the glowing hearths of steel mills instead of their post-industrial rubble (or, in the case of US Steel’s fabled Homestead (Pa.) Works, a shopping mall built on top of it). Donald Trump’s delusional aspirations for the coal industry today were a reality then; our nation had more than two hundred thousand underground miners. Unions like the United Mine Workers and the much larger USWA and Teamsters negotiated master contracts that were industry-wide. Owners of steel mills and trucking companies signed agreements covering half a million workers at the same time.

In the era before de-regulation, de-industrialization, and corporate globalization, such union density and bargaining clout produced good wages and benefits. But discontent, among blue-collar workers, over poor working conditions was too often ignored. Problems like compulsory over-time, job safety and health hazards, unfair discipline, and relentless management pressure for greater productivity spawned dissident activity, which took the form of unauthorized strikes or internal union election challenges.

Revolt From Below

At the local level, if union officials failed to provide proper representation, aggrieved members often took matters into their own hands. They by-passed grievance-arbitration procedures that were frustrating and overly legalistic. Risking injunctions, fines, and even jail time, they flouted the “no strike” clauses found in almost every U.S. labor agreement. In 1972, a slate of rank-and-file coal miners, with just that kind of wildcat strike experience, made U.S. labor history when they toppled the corrupt and thuggish national leadership of the UMWA. Inspired in part by these Miners for Democratic, restive truckers and warehouse workers formed Teamsters for a Democratic Union (TDU) a few years later, with much help from socialists among them.

In an era when rank-and-file rebellion was the wave to ride, young Ed Sadlowski was a pretty good surfer. His father, known as “Load,” worked for Inland Steel in East Chicago, joined the Steel Workers Organizing Committee in the 1930’s and became a founding member of USWA Local 1010. Eddie’s own nickname—“Oil Can”—came from his job oiling equipment at US Steel’s South Works in 1956.

For a budding, second-generation union activist, this relatively low-status position proved to be an in-plant organizer’s dream. He was able to circulate widely and connect with disgruntled co-workers throughout a mill employing 14,000 members of USWA Local 65. In 1964, when Sadlowski was only 26, he led a local reform slate to victory, against much older incumbents, and became president of Local 65. (In today’s labor movement, local union presidents under the age of thirty are exceedingly rare.)

An Official Family

Less than a decade later, after a brief stint on the District 31 staff, Sadlowski found out how much his union (and others, in that period) welcomed promising new leaders. When he tried to run for District 31 director, the union’s “official family,” as it was called, rallied around his better-connected opponent. The election was stolen but the US Department of Labor ordered a re-run under federal-supervision. Backed by USWA pioneers like George Patterson, a picket captain who survived Republic Steel’s massacre of strikers in 1937, Sadlowski won that vote by a 2 to 1 margin. In 1975, he became a most unwelcome addition to an international executive board then headed by USWA President I.W. Abel, a 68-year old gent fond of black-tie dinner soirees with Big Steel management.

Abel’s strategy, as a “labor statesman” nearing retirement, involved not just discouraging grievance strikes, but also promising, in advance, that steelworkers wouldn’t strike when their national contract expired. This questionable approach, allegedly dictated by industry conditions, was dubbed the Experimental Negotiating Agreement (ENA). Sadlowski became the USWA’s leading critic of Abel’s experiment because ENA replaced the right to strike with binding arbitration and was negotiated, in secret, without any membership vote approving it. (When his deal was challenged in court, Abel claimed a bargaining black-out was necessary because, with any advance publicity, ENA “might have been rejected.”)

Sadlowski decided to take his case, against the ENA and other manifestations of “tuxedo unionism,” directly to the membership, in a February, 1977 election to choose Abel’s successor. Abel, his e-board colleagues, and USWA headquarters staff cobbled together an establishment ticket headed by Lloyd McBride, the union’s bland but loyal District 34 director from St. Louis. McBride strongly defended the ENA and accused Sadlowski of promoting an “impractical kind of pure democracy that would lead to chaos.”

A Civil Rights Struggle

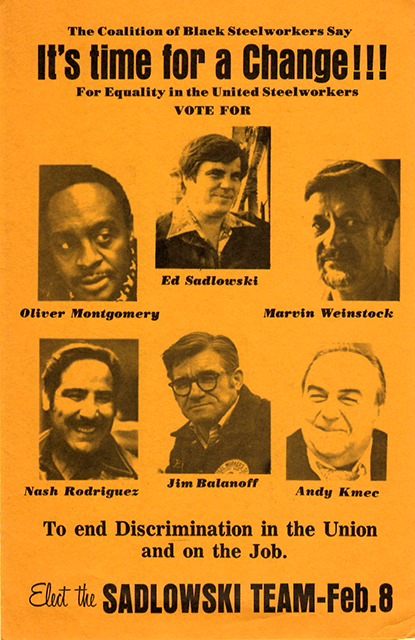

Long before bumper stickers appeared on Volvos urging us to “Celebrate Diversity,” Sadlowski did just that when he assembled his own insurgent slate. In addition to himself, a Polish-American, the Fight Back slate included a Chicano, a Croatian-American, a Jew of Eastern European origin, and an African-American. (This rainbow coalition made for quite a mouthful on lunch-pail and helmet stickers—“Elect Sadlowski, Rodriques, Kmec, Weinstock, and Montgomery!”)

As of 1976, no African-American had ever made it to the top ranks of America’s second largest industrial, during the first four decades of its existence. In the 1960s, persistent racial discrimination in the mills and under-representation of black members in the USWA bureaucracy spawned a civil rights movement within the union. One of its leaders was Oliver Montgomery from Youngstown, who became Fight Back’s most articulate spokesman (out-shining even the presidential candidate himself on many occasions). To undercut Sadlowski’s appeal to minority workers, with a formidable ally like Montgomery, USWA headquarters created a new vice-presidency for “human rights.” The position was filled by an Abel Administration loyalist, whose main qualification was not being part of past civil rights agitation within the union.

On the ground, the Fight Back campaign swarmed with lefties, young and old. Most were “colonizers,” toiling in difficult and dirty steel mill jobs. This gave them essential shop-floor access to potential Sadlowski voters, most importantly in locals controlled by supporters of Lloyd McBride. Each competing political sect—from the old Communist Party to the Revolutionary Communist Party to the Socialist Workers Party and the International Socialists—had a different “line,” leading to much jockeying for position among their respective cadres. Only the Chairman Mao-inspired October League dismissed the USWA election as “a trick by the bourgeoisie to channel the revolutionary aspirations and strivings of the masses into reformism.”

Liberal Cult Figure?

Meanwhile, anti-communists were attacking Sadlowski with more impact than the October League. Anonymous plant gate flyers in the Mon Valley, where I was a SFB volunteer, claimed that our candidate favored a ban on all gun ownership—not exactly a popular position in (I)Deer Hunter country. Our many external critics included right-wing social democrats allied with conservative AFL-CIO president George Meany. Their aggressive red-baiting focused on Old Left friends and allies of Sadlowski in Chicago and former staffers of the United Mine Workers in Washington, DC. Under new UMW leadership, the latter had already ruined labor relations in the coalfields. Now, these same “outsiders” (of whom I was one) were trying to disrupt USWA functioning too.

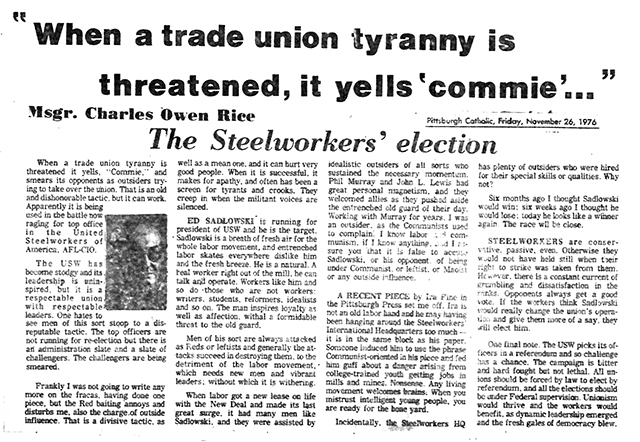

In Pittsburgh, we sought to counter such smears by enlisting one of the nation’s premier labor priests (before that breed became nearly extinct). At his dark-paneled Pittsburgh office, Msgr. Charles Owen Rice expressed some pastoral regret about having been a red-baiter himself in the 1950s, doing much local damage to left-wing unions like the United Electrical Workers. Perhaps as an act of personal penance, Rice soon penned a column in the Pittsburgh Catholic that we quickly reprinted and distributed widely at shift change in the mills.

The old monsignor sadly observed that the USWA had become “stodgy and its leadership uninspired.” According to Rice, Ed Sadlowski was “a breath of fresh air for the whole labor movement…Workers like him and so do those who are not workers—students, writers, reformers, and idealists of all sorts. The man inspires loyalty as well as affection and thus represents a formidable threat to the old guard.”

As he barnstormed around the country, giving rousing speeches in every available working class meeting place, Sadlowski received some supportive media coverage. But business-oriented scribes like the young David Ignatius, then at the Wall Street Journal, found lots of reasons to prefer “the old guard.” According to Ignatius, Sadlowski was just “an engaging young union official unsullied by the experience of major responsibility…a momentary liberal cult figure…with a short and un-distinguished record.” Why, Ignatius wondered, should anyone be drawn to romantic invocation of past-industrial union glory when modern-day steel workers should be content with “actual organized power and stability, as evoked by Lloyd McBride.”

Inside the union, USWA headquarters deployed an army of appointed “staff men”—International Union reps who were then almost entirely male—to ensure McBride’s victory in February, 1977. Only four of these 800 full-time pay-rollers dared to endorse Sadlowski (and two of those were members of his own slate!) USWA field staff wielded much influence over elected officers and stewards in the thousands of smaller USWA shops they serviced. Many used their workplace visits—ostensibly for grievance handling or contract negotiations–to do heavy campaigning for McBride, a misappropriation of union resources often hard to document in post-election complaints.

After a grueling contest, with all the trappings of an electoral campaign for public office, about 580,000 USWA members trooped to the polls in hundreds of local union halls. Balloting on this scale made Sadlowski vs McBride the biggest direct election ever held by a U.S. union. Of course, competition in that category is virtually non-existent today. Only the Teamsters—as part of a court-approved racketeering case settlement—regularly hold contested referendum votes for top officers, after grassroots campaigning by incumbents and TDU-backed candidates every five years. Most national union leaders are chosen at more easily controlled conventions of several thousand delegates, or fewer.

Unfortunately, 57% of those voting on February 8, 1977, embraced Lloyd McBride, rather than the “breath of fresh air” represented by Sadlowski and SFB. The Association for Union Democracy, which organized and funded poll watching for Sadlowski, suspected that election fraud tainted the outcome. This time, the Department of Labor didn’t agree that the Landrum-Griffin Act had been violated.

A Changed Union Culture

After Sadlowski lost, he returned to his old District 31 staff job, kept his head down, and beavered away, for many years, as a servicing rep. He was shielded from headquarters retaliation, initially, by the fact that his elected successor, as district director, was Jim Balanoff, a longtime friend, ally, and SFB stalwart. Steelworkers Fight Back did not become a long-distance runner like TDU. But, even as it was disappearing as a formal oppositional network, Sadlowski campaign veterans in Ohio, Pennsylvania, Illinois, and Indiana put their organizing skills to use in the bitter plant-closing fights of the 1980s, when the steel industry cratered.

Left-leaning Sadlowski supporters like Dave Patterson and Dave Foster won district director elections in other parts of the union. Foster played a key role in getting the USWA involved in the Blue-Green Alliance, which tries to unite industrial workers and environmentalists. The Alliance continues to receive strong backing from current USW President Leo Girard, a socialist-minded Canadian who didn’t back Sadlowski in 1977 (or Bernie Sanders two years ago). As Sadlowski’s son noted on June 10, “the Steel Workers Fight Back movement, without question, changed the culture of the USW and the labor movement for the better.”

In two decades of retirement, “Oil Can” Eddie did not become a golfer, although Florida was a seasonal refuge from the Windy City for him and his wife Marlene, a pillar of their family for 58 years. Sadlowski remained active in many labor-related causes, including the Association for Union Democracy in New York. Just a few years ago, out here in California, I found myself on the same team with him again, during a National Union of Healthcare Workers campaign to help 45,000 Kaiser workers escape from a dysfunctional and undemocratic SEIU local. In his seventies, Sadlowski was still sharing advice, handing out leaflets, knocking on doors, and making phone calls to workers in what proved to be, for the time being, a lost cause.

Suffering an election setback, after a rancorous debate about labor-management partnering, was not a new experience for this NUHW volunteer. Better than anyone active in labor over the last half century, Ed Sadlowski knew that today’s “losers” can become tomorrow’s winners, if we stick together and keep organizing. If his failing body and mind hadn’t made that impossible, he would have been applauding the red state labor rebels responsible for recent public school walkouts. Whether it was steel workers, hospital workers, under-paid educators, or other public employees fighting back, you could count on Brother Sadlowski being there, in person or in spirit. His gruff, but caring, presence will be missed on many a picket line now.

An earlier version of this piece appeared in MROnline

Addendum to Early article: The legacy of the Sadlowski campaign was swamped by the tsunami of the 1980s steel industry crisis

By Garrett Brown

Officially, Ed Sadlowski lost the 1977 election for president of the United Steel Workers of America (USWA) by a margin of 43% to 57% to the candidate of the union’s officialdom, Lloyd McBride. Some Sadlowski supporters in his rank and file organization, Steelworkers Fight Back (SFB), believed that he actually won the contest, but voter fraud in Canada (more votes than local union members) led to the electoral loss. The SFB campaign in Canada was simply not strong enough to prevent that kind of fraud, if that’s what happened.

But Canadian irregularities may not have been necessary as the officialdom’s mobilization of its 800 appointed “international staff” to threaten local union officers and members that if they voted for Sadlowski, then the international’s staff at local, regional and national levels would turn its back on the local unions when it came to grievance hearings, local contract bargaining, or other support from the international union, was anything but an idle threat.

The fact that SFB was credited with 43% of a national union election was remarkable in documenting the ferment in the union and the openness to a new, more radical approach by working steelworkers.

But within a few short years this potential was swamped by the collapse of the steel industry, and the inability of the SFB leaders to generate an alternative program to the union officialdom’s complicity with management’s slow-motion suicide.

Coming out of the Second World War, the U.S. steel industry was the industry world leader and steel towns around the country boasted some of the best jobs and most stable, well-resourced working class communities anywhere. Forty-five years later, the industry was in crisis and steel towns were well down the road of ruin and abandoned rubble, a la Bruce Springsteen’s Youngstown.

This happened because the owners and managers of American steel made two big decisions:

1) Instead of continuing the industry’s traditional reinvestment of a percentage of profits into renovation and technology, they opted to follow the siren call of Wall Street’s “go-go 1980s” sending nearly all profits to the “coupon-clipper” shareholders

2) Industry managers stubbornly refused to adopt new, more efficient technologies being installed by Europe’s steelmakers (rebuilding from the ashes of WWII) and new steelmakers like Korea and Brazil. Instead of investing in the basic oxygen process (“BOP shops”) and expanding electric arc furnaces to remelt and reuse recycled steel, the U.S. industry relied for way too long on the century-old open hearth, integrated steel process.

The result was that “foreign competition” ate the U.S. industry’s lunch over several decades, while management paid out millions to stockholders and invested in other industries by way of asset diversification, leaving the mills and steel towns in terminal decline, and gutting the pensions and lives of tens of thousands of steelworkers and their families.

The industry’s answer was the still ongoing campaign (30+ years later) against “unfair foreign competition,” often centered on China and frequently with racial overtones.

With the industry’s self-looting and union officials’ connivance, despite the Sadlowski campaign, USWA members were trapped on the Titanic headed into the iceberg fields. The response of the USWA officialdom – always following the lead of management – was to become the choir in the “church of trade sanctions against unfair foreign competition.”

Unfortunately, the activists of SFB and the Sadlowski campaign were not able to offer an alternative and credible alternative to steelworkers who became increasing desperate to save their jobs and their communities from the catastrophe looming ever larger on the horizon.

Sadlowski himself never again ran for elective office in the USWA – a lost opportunity in my view, but it was his decision to make. Rank and file activists in SFB were not able to follow the example of the long-term organizers of Teamsters for a Democratic Union (TDU) – a development itself worthy of more discussion about why. Steel towns around the country in the 1980s and 1990s became hollowed-out shells where young people had no future, and many left.

Given the many challenges facing the labor left in the 21st century, it is worth thinking about what would have been an accessible, attractive and “feasible” alternative plan to save the U.S. steel industry in the 1980-90s that could have galvanized and inspired the steelworkers who voted for Sadlowski.

Would nationalization of the steel industry – or worker-run cooperatives – or coops run by boards including environmentalists and community members as well as workers – won the hearts and minds of steelworkers and steel towns in the era of President Reagan – or now in the era of President Trump?

How can we turn the unrealized potential of the Sadlowski campaign and legacy of hard-working SFB activists for a democratic, member-run union with radical program into a reality in an economy and labor movement that is so seemingly different from the 1970s? Yet the underlying problems are basically the same.

It is another of the ironies of American labor history that the union and workers that almost elected Ed Sadlowski international president should (40 years later) still be the cheerleaders of trade sanctions against steelworkers in other countries, and, according to USW officials, that voted 40% for a billionaire con-man grifter in the 2016 election.

Garrett Brown wrote extensively about the Sadlowski campaign as a reporter for The Daily Calumet newspaper in South Chicago in 1976-77. He was also a not-so-secret supporter of Steelworkers Fight Back and the election campaign during his free time on nights and weekends.

The Valley

By Enrico Deaglio

The long story of the highspeed train in the Susa Valley is a symbol, a paradox and a tragedy.

The boots of history have marched dramatically through the Val di Susa; therefore it’s no surprise that modern ones do the same. It was 218 BC when the powerful army of the Carthago general Hannibal crossed the Alps with 50000 soldiers and 37 elephants. He was heading south and wanted to conquer Roma in the most difficult way. A genius, but he didn’t succeed. Roma – lazy, already corrupt – instead, flourished and conquered the northern part of the peninsula. In 58 BC, Julius Caesar, reversing Hannibal invaded this time from the south, marching victoriously through the Val di Susa to arrive Gallia – France. He acted quickly, and his assessment, “veni, vidi, vici”, has become a catch phrase for swift victory.

Val di Susa – Susa is it’s magnificent Roman capital – is a broad, green and spectacular valley. From the outskirts of Torino it runs northwest 90 km to the French border. High and steep mountains with vast glaciers border The Valley on the left and on the right. Being one of the main passages of continental Europe, centuries have provided The Valley with castles, monumental fortresses, churches, abbeys, and fascinating legends of warriors and bandits. Extensive use of dynamite occurred here in the mid nineteen century when the very modern Frejus gallery was built unifying Italy and France via a 50 km long tunnel across the border.

In WW2 The Valley forged a strong anti-fascist guerrilla movement, remembered today in monuments and songs. The post war economy has seen The Valley prosper with ski resorts, tourism, textile industry, and new markets for wines and cheeses. Many of the 100,000 residents commute to industrial Torino, and many Turinese have second homes here.

The idyllic scene was broken when in 1991, out of the blue, a pantagruelic (a gigantic prince, noted for his ironical buffoonery, in Rabelais’ satire Gargantua and Pantagruel (1534)) state plan for The Valley was announced for a highspeed train (TAV, Treno Alta Velocità) running from Torino to Lyon. A colossal jobs venture between France and Italy; sponsored by the European Union and financed with 20 billion euros. The planned line would devastate The Valley. New tracks, 230 km of new tracks, and a huge 57 km tunnel would perforate The Valley, carrying passengers and goods. The “Grande Opera” was going to take decades, bringing in foreign workers and giving the natives nothing. (Being that the Mafia is the main force for the building business in Italy, residents felt that the Mafia would pollute their clean woods and rivers). Why all this? The plan was said to be of “strategic interest”, to improve business, tourism and trade between northern Italy and France, an indispensable link in the new futuristic railway network meant to link Lisbon to Kiev. In 1991, the plan said half a million people traveled from Turin to Lyon each year. The Promotion Committee forecast that by 2002 passenger numbers would increase fivefold to 7.7 million. The project was also supposed to take away trucks from congested highways, and decrease the pollution in The Valley.

It looked like a good, modern project that would transform a peripheral valley into a sort of thriving center of the new Europe. Well, it was all wrong. Other studies, no less scientific, explained that commercial traffic through the valley was going to decrease, not increase, the environmental hazards were huge, and costs would inevitably rise. Simply the big project made no sense. They were right. Twenty-five years later, the Susa Valley sits on the biggest social, environmental and political disaster, probably in all Europe. The Italian Army has deployed thousands of soldiers to protect useless building sites creating a sort of police state; fences and controls are everywhere, as are secret service agents. Hundreds of people have been incarcerated, indicted for “subversion”, and national politics has been affected in the worst way.

How did this disaster happened? Hard to say. But a mysterious story, always remembered, is said to have started everything. In 1996, while the first opposition to the high speed train was beginning to take shape, the Torino judiciary ordered the imprisonment of three young anarchists and accused them of conspiracy against the TAV. One of them, Edoardo Massari, nicknamed “Baleno”, was found hung in the Torino prison. His girlfriend, a 21 year old Argentinian named Maria “Sole”Soledad Rosas, was under house arrest, when she was found hung in the house. The third man, Silvano Pellissero, a young man of The Valley, whom the prosecutor said there was “gigantic evidence” against, was declared innocent. The tragic episode of the three supposed “ecological terrorists” had a big impact in Torino and The Valley, creating an atmoshpere of mystery and suspicion over the whole high-speed train affair. The Valley people, with dozens of mayors leading the protest, rejected the plan. A march of 70,000 people was attacked by the police. In the years since, the highway to France has been blocked dozens of times. All the political parties, and especially the left, defended the project, claiming that there were no enviromental risks, that the whole business would have been Mafia free, and an economic opportunity for The Valley. The opposition to TAV produced studies about the risk of asbestos and uranium in excavating the gallery, predicting at least twenty years of devastating works, all for a project that fullfilled no needed purpose. The high-speed train would reduce the schedule from Torino to Lyon by only by 20 minutes, having little impact on the transportation of goods. As a matter of fact – as a highly respected Politechnic Univerity study showed, it would have been much more ecologically sound, and cheaper, to use private airplanes instead of trains or trucks.

In twenty years many things have happened in The Valley. People’s opposition to the TAV has grown with a considerable show of militancy including marches, pickets, some sabotage actions, and clashes with the police on dozens of occasions. The Italian State has never conceded anything. Instead police, carabinieri and finally the Army, have been sent to protect the slow and very expensive construction works. On the political side, The Valley, always a leftist bedrock, ceased to be so. Lots of people refused to vote in regional or national elections. Many others supported the Five Star Movement led by the comedian Beppe Grillo (the only character who came to The Valley in solidarity with the residents). The “No TAV” movement also became the symbol of social antagonism nationwide, supported by the radical left everywhere. It’s still amazing to find “No TAV” signs even in deep Sicily. (As a matter of fact, the “No TAV” movement is the only radical event, not only in Italy but in Europe). A very famous lefitst author, Erri De Luca, was indicted for “promoting sabotage”, the charge stemming from a few generic words he made during a public speech. In the name of freedom of speech the author was acquitted at the trial.

The recent national elections may mean change for The Valley. Amazingly the Five Star Movement and Lega parties won a majority and formed the first populist goverment in Europe. However the problem in regards to the Susa Valley is Five Star Movement wants to stop the project, Lega wants to go on, and it’s too early to undestand what will happen.

The long story of the highspeed train in the Susa Valley is a symbol, a paradox and a tragedy. It has challenged the concept of democracy. Can a local community oppose a national will? Can a powerful state enforce its will on a dissident community? What is the role of science, experts, and intellectuals in the decision making? Can a wrong decision be changed by a peaceful movement?

So far nobody has found an answers.

Meanwhile history plays again its symphony. In the cold shadows of the high mountains, in the glittering sun of the glaciers, another army is moving through the Valle di Susa. Thousands of migrants coming from North Africa or Syria, from Yemen or Ethiopia, survivors of the Mediterranean sea wrecks pushing their way north through The Valley on the same route the highspeed train promised to use for a fast and confortable trip to Paris. They have never seen the snow in their young lifes. They camp in the ski resort of Bardonecchia. Some “passeur” shows them the old routes of smugglers and partisans to get to Nevache or Briancon. They buy a windbreaker, a pair of sneakers and they try to cross the border. Italian and French police chase them, and the good people who try to help them, or just to feed them, are inprisoned by the authorities.

When the winter ends the dead bodies of these African and Middle Eastern “soldiers” without elephants will appear again.

Vacancy control is the only realistic answer to San Francisco’s housing crisis

By Buck Bagot

SF doesn’t have many remaining sites for development of any kind. We should reserve those that remain for affordable housing development.

The cost of housing is transforming – destroying – San Francisco and the Bay Area. The crisis is so bad that the even the ruling elite is forced to address it. True to form, all of their proposals are shaped by their self-interest. Ditto local governments responses. Some people – and sadly not just the wealthy – believe that we can lower or stabilize housing costs in SF by building more market rate housing. I don’t. The housing market hasn’t worked for most San Franciscans for decades. I have no faith in market-based solutions. The monthly rent for a typical unit is $4650. The lower-end price to buy a home in the entire Bay Area is over $500,000. In a city like SF, with an international housing market, market rate housing may make the cost of housing even higher, not lower. But most importantly, the debate over market rate housing, and new housing development in general, misses the most important solution – strong rent control, or vacancy control. Vacancy control is the only way to save SF as a mixed-income and multi-ethnic, diverse City. The housing development debate gets far more attention than it deserves. Development is part of the answer, but it is more and more beside the point, as is even the building of affordable housing. The only reform worthy of discussion is strong rent control/vacancy control.

Earlier this year, State Senator Scott Weiner introduced SB 827 – ‘planning and zoning – transit rich housing bonus’. His legislation embodies the corporate elite’s solution – more market rate housing. Weiner’s bill is a gift to for-profit market rate developers, with the false ‘common sense’ rationale that more/denser market rate development will lower housing costs in SF. People on the Left opposed it for my reasons. People on the West side of SF opposed it because they oppose any and all additional development in their neighborhoods. They would oppose affordable housing even more strongly. It stalled in the CA legislature in 2018. He will reintroduce it next year.

SF doesn’t have many remaining sites for development of any kind. We should reserve those that remain for affordable housing development. Prop I – the Mission moratorium – called for declaring a moratorium on market rate housing development in the Mission. It was an effort to preserve any remaining Mission sites for affordable housing development. Development of new housing, affordable or not, will play a relatively small part in the fight to preserve the City as mixed income and multi-ethnic. The only way to save SF is with strong rent control – vacancy control.

The Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci’s concept of cultural hegemony is useful in understanding why the affordable housing debate is so skewed, and why both the corporate elite and local government refuse to pursue the only realistic solution. What serves the interests of the class in power is taken as common sense and a given, and what challenges it is viewed as irrational or blasphemy. That’s the best way to understand the politics of the market rate housing vs. strong rent control debate.

The belief that more market rate housing will lower the cost of housing is straight up supply side Reaganomics. How much housing of any kind gets built in SF every year? And even if folks built on every available site, how many units are we talking about? The City is 2/3s renters. We need changes that stabilize their rents and permanently lower the cost of rental housing. There’s only one solution – vacancy control.

With the passage of the Costa-Hawkins Act in 1995, landlords and developers got the California legislature to preempt a locality’s ability to institute vacancy control. (I wish there were a more people-friendly term than vacancy control. ‘Strong rent control’ isn’t sufficient, especially for areas where there is no form of even weak rent control). Berkeley and Santa Monica had passed strong rent control, and San Francisco came within one vote of over-riding then-Mayor Dianne Feinstein’s veto to pass it. The Costa-Hawkins Act limits local rent control to vacancy decontrol – controls only on occupied units. A landlord can raise the rent whenever a unit becomes vacant. Over time, the increase in rents remains the same, with periodic unit-by-unit stabilization. Vacancy decontrol also gives landlords a tremendous incentive to evict people, especially longer-term renters who have stabilized rents.

The good news is that a California Alliance of Californians for Community Empowerment (ACCE) led coalition has gathered enough signatures to place repeal of Costa-Hawkins on the November 2018 ballot. If passed, it would remove the Costa-Hawkins preemption and return authority to decide on rent control to the local level.

The only ‘market’ based solution I believe would work is universal Section 8 or deep rental subsidy.

California’s tenant organizations had assumed that folks around the state wouldn’t understand the need for vacancy control unless and until they had experienced vacancy decontrol, and realized its limitations. They have worked, with mixed success, in smaller cities and in the San Joaquin Valley, to win vacancy decontrol. Statewide tenant leaders have felt that it didn’t make sense to go to the ballot statewide until more cities had experienced vacancy decontrol, like SF, Oakland and LA. But – and it’s too long a story to relate here – the Executive Director of the SF AIDS Foundation bankrolled a statewide effort to place Costa-Hawkins repeal on the statewide ballot. He failed to confer with tenant organizations. He had the money to pay signature gatherers. The tenant groups joined in. So repeal has qualified for the November 2018 ballot. CA ACCE, which has a strong base of members in cities statewide, has stepped up to try to provide leadership for the campaign.

It does make sense for nonprofits to build 100% affordable housing anywhere they can. They view any ‘underutilized’ site as a potential development site – parking lots (like the one in front of your local Safeway, one story warehouses, etc. Yet most local governments, like San Francisco, fail to pursue the development of new affordable housing wherever possible. Why don’t they? And why does local government cling to the false notion that ‘inclusionary zoning’ is the solution?

Affordable housing development comes down to two factors – sites, and ‘subsidy’. The primary impediment to creating affordable housing isn’t lack of sites, or Not In My Back Yards resistance. It’s the enormous amount of subsidy required to develop – by new construction or acquisition of existing multiunit buildings – affordable rental housing. Subsidy is the term for the amount of money needed to close the gap between the cost of housing and what a poor, working or middle class person can afford to pay. Even with the federal low income housing tax credit, every unit of affordable housing requires from $3-400,000 in local cash subsidy. The federal government long ago abandoned funding new affordable housing. The State has never provided much support. The City has shied away from passing the enormous general operating bonds required to provide the necessary subsidy.

‘Inclusionary zoning’ is the term to describe when government forces a market rate developer to provide the internal or non-public subsidy to produce a percentage of affordable units. I believe inclusionary zoning is like getting to roast a marshmallow while you’re burning at the stake. Whatever the percentage of ‘inclusionary’ units per development – 15, 20, 25% – it’s still a very small drop in the bucket.

The only ‘market’ based solution I believe would work is universal Section 8 or deep rental subsidy. Section 8 provides a landlord a set ‘contract’ rent. The tenant pays 30% of their income toward that rent – NOT 30% of the rent. The federal government provides the difference. A state or city could provide deep rental subsidy to replace federal Section 8, but the cost would be even greater than providing the subsidy necessary to maximize affordable housing development.

Teachers revolt in the USA bodes well for the future of labor

By Peter Olney and Rand Wilson

The expected Supreme Court decision in the Janus vs AFSCME case will deny public service unions the ability to collect representation fees from workers the union is obligated to represent. Once “open shop” goes into effect, the billionaire class and their media sycophants are hoping it will cripple the power of the public unions they despise.(1) But even before the decision, signs of renaissance and insurrection from public employees are coming from unexpected places. Teachers in U.S. states where collective bargaining and strikes are illegal have risen up in mass strikes resulting in significant gains.

Surprisingly, these strikes have happened in so-called “red” states where Donald Trump easily won in the 2016 Presidential election. In the Trump era’s unpredictable political environment , this is not as inexplicable as it might seem. The strikes are all in states where the conservative anti-taxation agenda has resulted in deep cuts to education funding and poor pay and working conditions for teachers. Overcrowded classrooms and a shortage of basic teaching materials and textbooks are widespread. History teachers describe their textbooks still featuring George W. Bush as the incumbent president. In many cases, teachers expend their own funds to buy notebooks and other essential school supplies that their students need.(2)

The most dramatic and successful strike to date was launched by 22,000 teachers and support staff in all 55 counties of West Virginia on February 22. Before the strike, members participated in district-by-district, face-to-face meetings and voted democratically to walk out. Social media played an important role, but as with all effective labor actions, personal contact was the key to cementing a commitment to action.(3)

The West Virginia strike action was particularly strong because many teachers built effective alliances with approximately 9,000 other school employees and with parents and students. In many schools, teachers packed student backpacks with food to take home during the strike, knowing full well that students and their families relied on school lunches for daily nourishment in impoverished communities. In many cases, sympathetic school superintendents and administrators canceled school, effectively shielding teachers from the state’s ban on striking.

The striking teachers and educational support staff flooded the state capital and openly challenged West Virginia’s right-wing Republican Governor Jim Justice. It was a very successful tactic. When an initial brokered settlement by their statewide leadership that fell short of their demands, rank and file strikers openly defied their leaders and voted to continue their job action until their goals were met.

Gov. Justice eventually caved-in to their demands and granted a five percent increase to all state employees. Finally victorious, they returned to work on March 7th.

The West Virginia strikers inspired similar actions in Oklahoma, Colorado, Kentucky, Arizona and North Carolina, all states, except for Colorado, that Trump carried in the 2016 Presidential election. While many strikers undoubtedly voted for Trump, their class allegiances were significantly sharpened as the struggle for quality education, and better pay and benefits intensified.

Strike fever appears to be spreading. Inspired by the teachers, 22,000 University of California service workers engaged in a statewide strike for three days from April 30 to May 2.(4) Presently 228,000 Teamsters are in negotiations for a new contract with giant United Parcel Service. Their contract expires July 31 and a strike vote has already been taken.(5)

The American labor movement is learning lessons that are crucial to labor’s survival in an environment where union rights are increasingly being taken away by a hostile Trump administration and its Republican majority in both houses of Congress.(6)

Ellen David Friedman has been organizing teachers for decades and is working with some of the most innovative teacher unions in the country. In an excellent analysis of the political and economic dynamics of the teacher strikes, she observed, “When there is no effective access to meaningful channels for change, workers resort naturally to the only power no one can steal from them—the power to withhold their labor. This spontaneous chain of wildcat strikes may be the only recourse left for the teachers when the unions and the politicians fail them, but they are also facilitated by the very weakness of the union bureaucratic environment around them.”(7)

This historic strike wave has strategic implications in both the union movement’s approaches to industrial action and labor-backed political action. As the authors have previously observed, when union members engage in mass actions – especially strikes – workers’ class consciousness rises and politically they move to the left.

Notes

(1) The Crimson

(2) How Much Do Teachers Spend On Classroom Supplies? National Public Radio (NPR)

(3) “A Crowdsourced Look at the 2018 West Virginia Teacher Strike,” Charleston Gazette-Mail, Part 1; Part 2

(4) “University of California workers start 3-day strike,” The Mercury

News, May 7, 2018

(5) “Striking Big Brown,” by Joe Allen, Jacobin, May 17, 2018

(6) “The West Virginia Teachers Strike Shows That Winning Big Requires Creating a Crisis,” Jane McAlevey, The Nation, April 9, 2018

(7) “What’s Behind the Teachers’ Strikes, The Labor-Movement Dynamic of Teacher Insurgencies,” Ellen David Friedman, Dollars & Sense Magazine, May/June 2018

Also published in Italy Sinistra Sindicale

Heart in Place: Kwasi Boyd-Bouldin

By Roger May

Orignially posted 21 May 2018 on Walk Your Camera with permission of Roger May and Kwasi Boyd-Bouldin

You might be wondering why you’re looking at pictures of Los Angeles on a blog that deal primarily with work from Appalachia. From my desk in Charleston, West Virginia, Los Angeles is more than 2,300 miles away, but there is a proximity of heart for place I find in Kwasi Boyd-Bouldin’s photographs that I’d like to share.

I first learned of Boyd-Bouldin’s work via Twitter, though I can’t remember exactly who shared it. I scrolled through some of his images online and was drawn in by his straightforward manner of looking. His compositions suggested an eye of someone looking beyond the surface and beyond the stereotype of place. This is not the Los Angeles you’ve often been shown.

After several months of following Boyd-Bouldin’s work on Twitter, and later Instagram, it occurred to me that he is looking at his corner of Los Angeles in a very similar way I’m making work in West Virginia and Appalachia. Despite the geographical differences, there is a common thread of love for place, a desire to show a more realistic portrayal of that place through critical looking and thinking, and to document the impact of the physical changes in the landscape of one’s home.

For all the things I detest about social media, every now and again, there are redeeming qualities. Had it not been for social media, I might have never known about Boyd-Bouldin’s work. I might have never had the chance to reach out to him to tell him how much I appreciate what he’s doing and why he’s doing it. I might never have had the chance to ask him about his work and to share some of that work here.

Boyd-Bouldin’s work is becoming more widely visible. In February of last year, he was included in TIME’s 12 African American Photographers You Should Follow Right Now and in November of last year, the New York Times LENS blog featured some of his photographs and a brief interview. One of the things he said in that piece illuminated a foundational element in the work he makes and made me think about the work I make: “In part, he says, the project is his intention to document a vanishing L.A. Few who live outside it even know it exists. He wants “to present a portrait of the city that reflects the lives of people who live in Los Angeles, as opposed to the glossy fictional version that dominates the mainstream narrative.” Just substitute Los Angeles with Appalachia or West Virginia or Kentucky.

In his series The Displacement Engine, in which he provides much needed critical thinking and viewing on the issue of gentrification, he writes, “The effort to push vulnerable populations to the margins may seem to be organic but it is often an organized campaign. Perpetual, neighborhood wide rent increases coupled with a total sustained lack of local infrastructure (grocery stores, good public schools, etc…) are the ingredients needed to initiate the desired effect.” In West Virginia it isn’t the same type of gentrification but it is systematic erasure. Apply this lens to look at the organized campaign of the coal industry to keep an already vulnerable population marginalized. In Mingo County, West Virginia, there isn’t a single grocery store in the entire county. Likewise, four of the county’s five high schools (Burch, Gilbert, Matewan, and Williamson) closed their doors in 2011 before consolidating into one school, Mingo Central, which is built on a reclaimed surface mine site.

I trust you’ll enjoy Boyd-Bouldin’s work and his thoughtful approach to place. Scroll through for our brief conversation, including a list of photographers he recommends following. You can see more of Boyd-Bouldin’s work at his website Kwasi Boyd-Bouldin and The Los Angeles Recordings. You can also follow him on Instagram and Twitter.

Roger May (RM): Can you talk about the importance of photographing the place you’re from and how that informs your pictures?