May Day 2025: The current installment of an annual remembrance (1)

By Robert J.S. Ross, PhD

Dear friends, comrades and colleagues

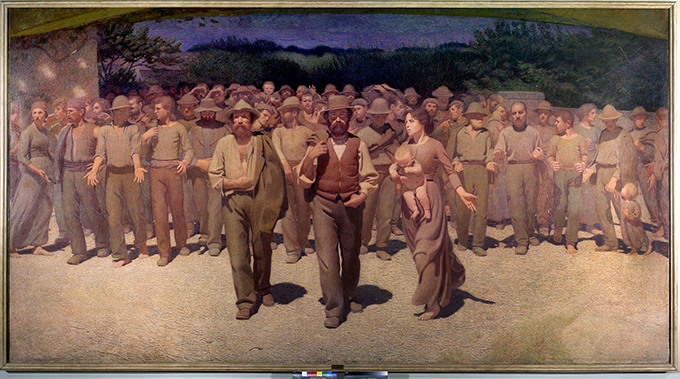

The story of May Day as an international worker’s holiday has its distant origin in Chicago in 1886. And it finds its relevance in the current Administration’s full throated attack on trade unions and standards of working conditions.

Since late in the eighteenth century American workers had sought to protect their lives and families –their humanity — by limiting the hours of the workday. As early as 1844 John Cluers led a labor federation calling for July 4 of that year to be declared a Second Independence Day in support of the ten-hour day.

Later, in the fall of 1885, the predecessor to the American Federation of Labor (AFL) decided upon May 1886 as the start of a series of strikes for the eight-hour day. They called for demonstrations declaring that after May 1 the working day would be de facto eight hours. Hundreds of thousands did demonstrate and strike that day, and tens of thousands won shorter hours.

The most memorable and tragic events of the 1886 struggle occurred in the days directly after what Samuel Gompers had also grandly called the Second Independence Day.

In Chicago, the May 1st rally in Chicago had been gigantic, and the city was tense. The Lumber Shovers union of 10,000 was on strike for the eight-hour day. They held a rally on May 3rd near the McCormick Harvester works, which was then gripped in a bitter lock-out and strike. As the workday ended at Harvester, strikebreakers came through the gates and some of the six thousand rallying workers protested against them. Police shot at the rallying lumber shovers and killed four on May 3rd.

On the next day, May 4, the leaders of the Chicago Eight-hour movement, anarcho-syndicalists of exceptional leadership ability, most of whom were immigrants, called for a protest of the shootings and a demonstration of resolve. It was rainy and there were numerous neighborhood rallies that day. The crowd was small. It dwindled from three thousand when the charismatic Albert Spies spoke, followed by his comrade Albert Parsons. By the time Samuel Fielden began his address the crowd had become only 300.

Then, 180 armed police, who had been waiting in a side street, marched into Haymarket Square, surrounded the small throng, and ordered the crowd to disperse. Fielden defended his right to speak. The police approached the platform and a bomb was thrown at them. One officer died there and six later. Later research showed that five of the six police who later died were shot by friendly fire as a result of police indiscriminately firing into the crowd. [Eighty-four years later, on May 4th, six Kent State University students protesting Nixon’s invasion of Cambodia, were shot and killed by National Guardsmen firing indiscriminately into a crowd of demonstrators.]

With scant evidence, the leaders of the eight-hour movement were tried and convicted of the murder of one of the police. Four were eventually hanged in November 1887; years later a courageous governor of Illinois, John Peter Altgeld pardoned three who were still in jail. One of the eight died in prison (a suicide).

After the convictions of the Haymarket leaders a worldwide movement in their defense spread through the labor and socialist camps. Thus, the American struggle for an eight-hour day was internationalized by the trial of the Haymarket martyrs.

The Haymarket bombing sparked the first Red Scare. Police around the country hounded labor leaders and socialist and anarchist groups. The defense efforts were not successful – although three of the eight eventually had their death sentences commuted and they were later pardoned.

However, by 1888, Gompers and the AFL were ready to launch once again a militant movement for the eight-hour day. The AFL called for a series of demonstrations, including Washington’s Birthday and July 4th 1889, and May 1, 1890.

“… it is a good time, as attacks on our rights and benefits mount, to celebrate and experience solidarity”

In the summer of 1889, the (Second) Socialist International was being re-founded in Paris. A representative from the AFL read a letter from Gompers to the Socialist Congress asking for support for worldwide demonstrations in favor of the eight-hour day. The French representative LaVigne inserted into a prior resolution on the eight hour day support for the American demonstrations on May 1st 1890. And so, around the world on May 1, 1890, workers called for the eight-hour workday – and many struck and achieved it or shorter hours. In Vienna, the entire working class called the day off. In the United States, the Carpenters, leaders in the struggle, won shorter hours for 75,000 workers. By the next year, 1891, it appeared that the May 1st demonstrations for a shorter workday had become an international and regular practice, becoming also a call for universal peace and a celebration of working class power.

Eventually, the conservative wing of the AFL would cause that labor federation to give up ownership of May Day and instead to preserve Labor Day in September as a more conventional American celebration. Around the world, though, both socialists and communists treat May Day as workers’ celebrations.

In the last few years the mainstream labor movement, i.e., the AFL-CIO, has come to acknowledge May 1 as “Workers Memorial Day.” And it is a good time, as attacks on our rights and benefits mount, to celebrate and experience solidarity.

The precious time workers wrenched from the grasp of employers and courts is embodied in our Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938. It requires overtime pay past eight hours in a day or forty hours in a week, as well as giving Congress the authority to set a minimum wage. Its companion was the Wagner Act, the National Labor Relations Act of 1935, committing the nation to support unions and the right to collective bargaining. Each of these is a pillar of decency and support for the dignity of work and labor; and each is now under attack.

There will be broadly based demonstrations on May 1, here in the USA defying Trump and his band of bumbling fascists, and elsewhere wherever working people are able.

I’ll be on Boston Common; perhaps we will greet each other there..

Solidarity

Bob Ross

1)Emended annually, the basic historic narrative is culled from May Day: A Short History of the International Workers’ Holiday, 1886-1986 Paperback – January 1, 1986 – by Philip Sheldon Foner

…