Paul, You were a great friend, comrade, and pal

By Steve Brier

“What always came through in Paul’s teaching was his abundant intellect and sheer passion for working-class history”

I met Paul in 1970-71 when I was a doctoral student in U.S. history at UCLA and Paul had just started teaching in the department as an instructor. I was soon assigned as his teaching assistant in an undergraduate U.S. history course (it might have been on southern or post-Civil War history; I can’t recall). Paul had his own distinctive teaching style then: He was a provocative lecturer, always challenging his students; he tended to favor flannel or work shirts and blue overalls as his professorial “costume.” But what always came through in Paul’s teaching was his abundant intellect and sheer passion for working-class history. Paul taught me how to be a better labor historian and how to think about the conflicted relationship between issues of race and class in U.S. history. I also learned a lot from watching Paul teach, reading his work, and listening to him engage with and encourage students (including me). He even let me lecture in his class (an “honor” for a grad student) about my own research work, which paralleled his work on interracial unionism in the coal industry (he wrote about Alabama; I did West Virginia). When I set out to do my first coal miner research work back East in 1972, Paul made a point of introducing me to the distinguished labor historian David Montgomery, his dear friend, and encouraged me to make a pilgrimage to visit with Montgomery in his Pittsburgh home and to tell him about my work. I like to think I carried over many of those lessons that Paul taught me in my own subsequent writing and teaching in what has turned out to be my four-decade long academic career.

My daughter Jennie was born in January 1971 soon after I met Paul. Since Paul and Linda had already had Catha (who is a few years older than Jennie), and were about to have Krissy, we all gravitated to the struggle to create and sustain the UCLA Child Care Center (CCC), which was an unrealized and much needed institution at UCLA in those years. One of the hallmarks of that student- and faculty-led struggle that the Briers and the “Worthpeople” (as we called them then so as to clearly indicate our opposition to patriarchy!) helped to lead was that the CCC needed to be open to all members of the campus community: students, faculty, and staff; that it be formed as a co-op in which all parents had to put in a minimum of 5 hours of work a week, not only to reduce costs for students and staff but also to encourage buy-in by the parents; and that the center accept babies as young a few months old, an important concession to young students who were starting families and going to school. The UCLA administration refused to accede to our non-negotiable demands for the CCC, including for a dedicated campus space for the center and provision of necessary support funding to pay unionized staff. When the UCLA chancellor, Chuck Young, refused to negotiate with us we decided to stage a sit-in in his office. After we took over the office we discovered that Young collected very expensive what were then called “Oriental” rugs, which covered the floors of his substantial office space. We quickly decided to reach out to student parents involved in the child care struggle who had young babies and recruited a handful of babies who were known to “projectile vomit” their formula. We brought them to Young’s office where they “did their thing”; the rugs looked polka-dotted after half a day of babies lolling on the floor! Young caved in soon after and authorized the child care center, which is still going more than half a century later. Paul, Pam Brier (my wife then) and I remained actively involved in steering the CCC through difficult times over the next three years as members of the parents’ steering committee. Paul and I even resigned in principled protest over some outrage (the exact nature of which I can’t quite seem to recall at this point). We submitted our joint letter of resignation to Pam Brier, who was then serving as the chair of the board. One thing that you learned when you did politics with Paul was there was no compromise or room for sentimentality, even when it involved a member of your own family!

That both the Brier and Worthman families had girl children was another basis for our bonding. I always admired the way Paul and Linda had raised Catha, who always acted smart, self-assured, and independent, and how they carried that approach over after Krissy was born a few years later, despite Krissy’s medical issues. Paul and Linda were my models as parents of how to raise smart, tough, and independent girls. My daughter, Jennie, is indeed that kind of adult, a fact that I attribute to the model that I observed Paul and Linda living.

Paul and Linda’s house in Mar Vista was a magnet for progressive UCLA faculty and graduate students, who gravitated to their home for meals, music and political and ideological conversations. Paul also recruited his graduate students to help with home improvement projects. He once put me in charge (or perhaps I foolishly volunteered) to build a low brick wall in their backyard that may have had something to do with creating a dedicated space for Linda’s keen gardening skills. I plunged in to the project (not knowing what the hell I was doing) and though I managed to build a “wall” with brick and mortar I can say that my one true regret is that I didn’t build a better, straighter wall in the Worthmans’ backyard, lo those many decades ago!

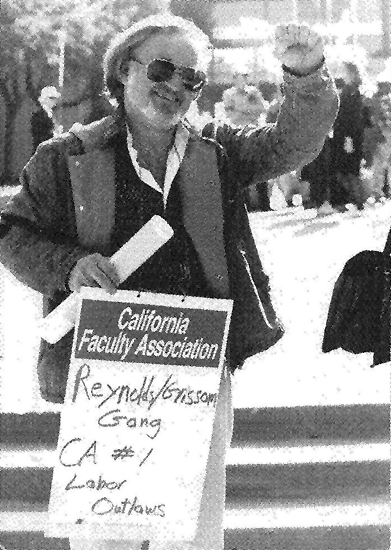

I was also involved with Paul in what proved to be the tumultuous politics of the UCLA History department, which were endless and frustrating. One moment is illustrative of how Paul approached dealing with his fellow UCLA faculty members and why he ultimately ended up leaving academia for a far more important career as a union organizer and negotiator. The department always had pretensions of becoming the Harvard or Yale of the West. In one key moment in the early 1970s the department big-wigs decided to try to recruit the old school historian and Lincoln scholar David Donald from Harvard to join the UCLA faculty. Because Paul had a well-deserved reputation as a contrarian among his faculty colleagues, they dispatched Frank Gattell, a friend and senior faculty mentor of Paul’s, to make sure that Paul would “behave” in the faculty gathering to welcome Donald to the department. Gattell was especially concerned that Paul shed his work shirt and overalls and be sure to wear a tie to the meeting. Paul assured him that he would indeed wear a tie to meet Donald. And when the time came for Paul to enter the faculty lounge late for the meeting with David Donald, he was not wearing one tie; he was wearing two ties! This was Paul’s way of assuring his faculty colleagues that he knew how to behave like a proper faculty member. Needless to say, Paul didn’t last too many years after that before he made the absolutely right decision to switch careers to his first love: labor organizing.

Paul: You were a great friend, comrade, and pal and I was glad I was able to tell you before you died how much I admired you and what you stood up for in your entire life and career. You will be missed and remembered by me and legions of other family, friends, fans, and comrades.

Your comrade in peace and power,

Steve Brier

…