A Libertarian Fantasy in the Tropics

By Bruce Nissen

Do you find that right-wing proposals to shred our country’s social safety net to pieces and to unburden giant corporations from regulations that protect the environment, worker’s rights, health and safety, and so forth, to be scary? If so, you should look at experiments being tried in Honduras — experiments that make anything being tried here look like half-hearted amateurish measures.

In early January 2024 I joined a delegation of U.S. and Canadian citizens on a nine-day trip to Honduras that was sponsored by the Cross Border Network and supported by other groups that were also members of the Honduras Solidarity Network (also a sponsor). The purpose of the tour was to learn about the effects that our multinational corporations and governments were having on this country, which is the poorest of all the Central American countries.

I learned a lot about Honduras and the perilous existence of many of its residents, be they laid off and injured workers in a local “maquiladora,” racial minorities, trade union leaders (the country recently earned the dubious distinction of having the highest percentage of its union leaders murdered), and in general a country traumatized by a 2009 coup by the military. But nothing I saw or heard left as lasting an impression as something I had never heard of before: special economic zones known as ZEDES (Zones for Employment and Economic Development) that are designed to bypass or evade almost any form of democratic or governmental control over the behavior of those investing in them. We visited and saw up close the country’s most advanced ZEDE, named Prὀspera, on Roatan, a Honduran island off the north coast.

WHAT IS A ZEDE?

How a ZEDE is defined seems to depend a lot on who is doing the defining. Fans of ZEDES describe them as being massive job creators and prosperity generators due to their cutting unnecessary and job-killing government regulations. Detractors tend to define them as the hyper-capitalist embodiment of right-wing fantasies that empower wealthy owners to evade taxes, mistreat workers, and despoil the environment.

The Prὀspera ZEDE is the country’s most ambitious of the three chartered under the previous government. It has the following features:

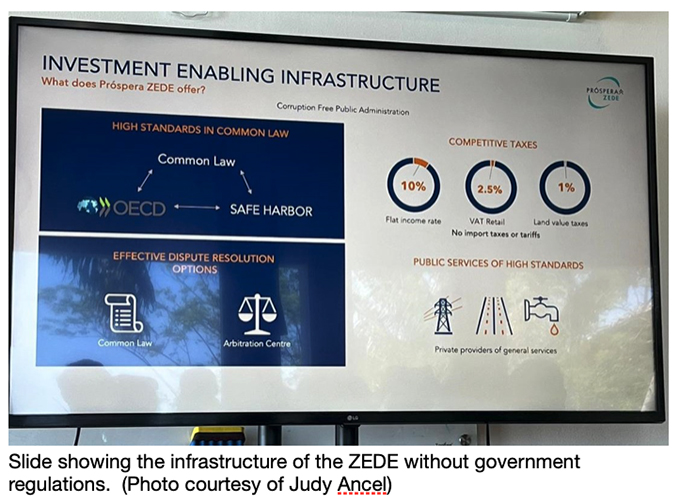

- While it remains subject to Honduras’s constitution and criminal code, for non-criminal legal matters the ZEDE has its own civil law and regulatory structure.

- The ZEDE civil disputes are handled by an extremely flexible arbitration structure designed to enforce the laws of whatever country a ZEDE business chooses to place itself under (in other words, it could be enforcing the labor laws of Slovakia or any other country from a list of permissible countries to suit the self-choice of any ZEDE enterprise).

- The administrative governance of the ZEDE is handled by a Technical Secretary (TS) who is responsible to and is overseen by a primary governing body known as the Council of Trustees (see below).

- Honduras Prὀspera, Inc. is a private company that owns the ZEDE. It sits on Prὀspera’s Council of Trustees (aka “The Council”) and has veto power over it. The Council is composed of nine individuals, five elected and four appointed by Honduras Próspera Inc. (Those “elected” are chosen by a complicated process that gives landowners more votes depending on the size of their land plot.) Decisions to change any of these arrangements must have a 2/3 majority, or 6 of the 9. (This means that Honduras Prὀspera Inc. holds a veto over any changes.) The Council is the primary governing body; it has a private police force and its own tax system, with extremely low tax rates.

- A non-elected Committee for the Adoption of Best Practices (CAMP) oversees the Council and has the power to approve all internal regulations and to provide policy guidance. It was appointed by the corrupt Honduran government that initially pushed through the ZEDE law (and whose president at the time, Juan Orlando Hernandez, has subsequently been found guilty of narcotrafficking and was sentenced to 45 years in a U.S. jail in June 2024). Nine of CAMP’s members are from the U.S.; only four come from Honduras. CAMP fills its own vacancies, ensuring no political influences can change its orientation or trajectory.

- All basic services that a government normally provides or regulates, such as water, electricity, education, healthcare, etc. are provided by private entities that contract with the ZEDE Council to provide them.

Looking at the above bullet points, it should be obvious that any normal “government” with governmental powers is basically absent in Prὀspera. Virtually everything is privatized. Anything a government would typically do is to be provided through a private contract either between private citizens and private companies or between a “private government” controlled by a for-profit company based in the U.S. (Honduras Prὀspera Inc.).

The income tax is nominally 10% but since only 10% of business income is taxed, the effective business income tax rate is 1%. Tax avoidance is a major incentive to invest in Prὀspera. Matters of justice are also addressed through contracts and a private arbitration dispute resolution system. There is no room for any kind of welfare measures of a public nature.

In other words, the Prὀspera ZEDE aims to be the embodiment of an economic libertarian’s dream: almost total absence of government and taxes, with all relationships between people and people-created organizations to be governed only by signed contracts. Market relations and enforceable contracts constitute the entirety of economic interactions. Any kind of governmental intervention to regulate the behavior of private corporations are to be eliminated or at least reduced to the maximum extent possible.

The allergy to government regulation even extends to the ZEDE’s currency: the official currency of Prὀspera is the cryptocurrency Bitcoin. Bitcoin is not issued by any government and theoretically is not subject to any regulation by any government. (This combination of Bitcoin currency, virtually non-existent regulation, and virtually no taxes would seem to make Prὀspera a perfect candidate for money laundering and other illegal financial activities.)

HOW DID ZEDES COME ABOUT?

ZEDES are a product of a military coup in 2009. In 2006 Manuel Zelaya became president following a November 2005 election. Although he came from the landed aristocracy, Zelaya increasingly moved left after his election, increasing the minimum wage by 80%, reducing bank interest rates, providing free electricity to the very poorest residents, and shifting the country’s foreign policy toward allying all Latin American countries into a common block to escape U.S. domination as well as forming friendships with Cuba’s Raul Castro and Venezuela’s Hugo Chavez. During his administration poverty declined by 10% in two years.

The Honduran elite families that owned much of the country’s land and wealth found Zelaya’s policies to be intolerable, as did the military and apparently U.S. policymakers. A military coup in June 2009 deposed Zelaya and deported him to Costa Rica. The U.S. government did not insist that he be returned to power. Instead, the U.S. supported new elections proposed by coup-leaders, and the consequent conservative/right-wing governments that were installed through widely criticized and rigged “elections” brought about the country’s ZEDE law. Porfirio Lobo Sosa, president from 2010-2014 attempted an initial ZEDE law, but it was overturned by the country’s Supreme Court as unconstitutional and a violation of Honduras’s sovereignty. A majority of the Supreme Court justices were then dismissed, and a new more pliant Supreme Court approved a second slightly amended version which was implemented under the rule of Juan Orlando Hernandez (generally known as JOH – pronounced like “hoe”), Lobo’s conservative/right-wing successor who ruled from 2014 to 2022. (As alluded to previously, JOH was convicted in the U.S. of narcotrafficking and weapons-related charges, along with Lobo’s son Fabio, JOH’s brother Tony, and JOH himself but that is a side-story to this brief history of the genesis of ZEDEs.)

After JOH’s National Party lost the 2021 Presidential elections to Xiomara Castro, wife of ousted former president Manuel Zelaya, her new government passed legislation abolishing the ZEDE law and attempted to dismantle the three existing ZEDES. This attempt to get rid of Prὀspera and other ZEDEs is being resisted, as will be related in a later section.

WE VISIT THE PROSPERA ZEDE IN JANUARY 2024

The leaders of our delegation had arranged for us to visit Prὀspera to see for ourselves what a ZEDE actually looks like. Prὀspera carefully guards who is allowed in (the public is not necessarily allowed to enter), so we had to fill out long and detailed questionnaires about our occupations, purpose in visiting, addresses, etc. before we were allowed in. By filling out these forms, we became “e-residents” of Prὀspera – to this day I receive communiques asking me to report the income I made in the last year within the ZEDE (which for me is of course nothing) for purposes of accounting and registration.

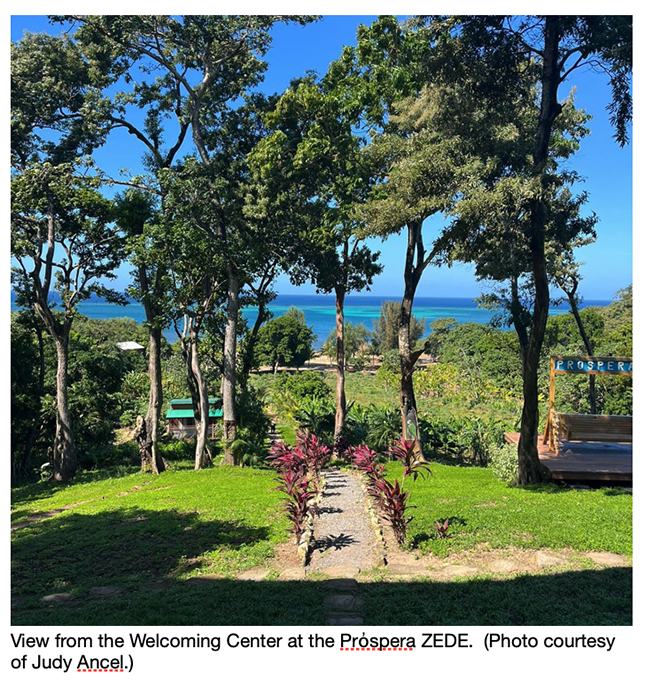

My first impression was not all that favorable. There is a very rough dirt road leading to the ZEDE; it certainly did not give the sense that a lot of commerce of a physical variety was entering or leaving the place. I know that a semi-finished resort is being constructed in Prὀspera and that residential and commercial construction is planned, but I didn’t see much of this. On the other hand, it is located on the northern coast of Honduras and has breathtakingly beautiful views of the sea, and for that reason alone could easily be a prime candidate for tourist development.

We got to meet two of the most important people involved in running Prὀspera. Ricardo Gonzalez is the Assistant ZEDE manager. And Jorge Colindres is the Technical Secretary in charge of its overall operations. Both spoke perfect English and were educated in the U.S. They both spoke to us at some length, especially Colindres.

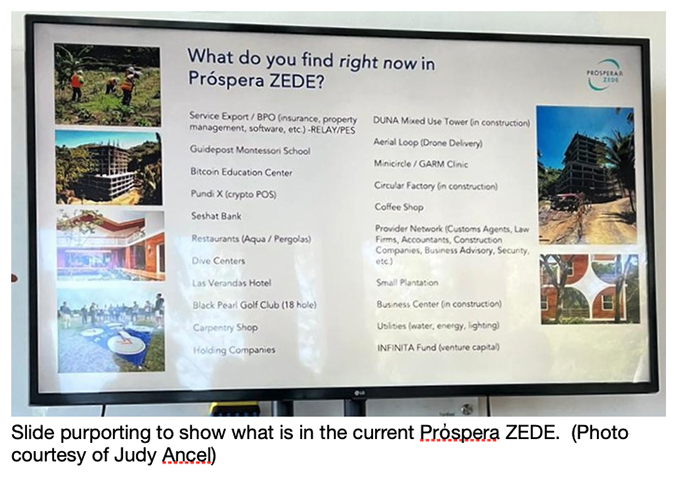

Both Gonzalez and Colindres are fervent believers in ZEDEs and the philosophy underlying them. They claimed that Prὀspera either had already or would soon attract carpentry businesses, export services, private education companies, restaurants, real estate firms, finance tech companies, medical clinics, and much more. Colindres called it a “Hong Kong in Honduras.”

Colindres noted that Honduras Prὀspera Inc. is a private U.S. company that created the ZEDE as a “platform for investment.” And he claimed that those investments would create prosperity for all and lessen or eradicate poverty. He (correctly) noted the widespread corruption in Honduran society and (dubiously) claimed that the ZEDEs would somehow be immune to such corruption. Everything is to be governed by binding contracts that individuals voluntarily sign, and these are enforceable by arbitration proceedings taken to the Prὀspera Arbitration Center (PAC) or else the business-oriented International Centre for Dispute Resolution (ICDR). This he claimed would settle disputes in a clean way that ordinary laws and regulations would not.

When pressed on the need for some form of regulation to prevent harmful “negative externalities” to others, he did concede that some form of controls is necessary and mentioned that according to the ZEDE’s charter ten industries in Prὀspera are not entirely free of oversight. I got five of these down in my notes: banking, healthcare, education, restaurants, and construction. How are these regulated? A company operating in any of these industries can choose its own regulations from those of 36 different countries. Thus, you could have a restaurant operating under the laws and regulations of, say, Estonia, while a restaurant across the street was governed by the laws and regulations of Brazil. It would be up to the owners of each restaurant to decide. Enforcement would be strictly by arbitrators deciding any disputes. Outside of the 10 industries there would be no regulatory control over the behavior of businesses or investors beyond any individual contracts they may sign.

Our delegation peppered Mr. Colindres with skeptical questions about the absence of regulatory control over especially big businesses. The most interesting thing about his answers is that they fell into two categories. The first category was a variant of the “trust me” justification. Since he is the Technical Secretary and hence the chief administrator of Prὀspera, he had the power to see that things were done properly, and he would never allow any violations of human rights or undue power for moneyed interests: we could count on it.

Second, he claimed (oddly enough for someone praising freedom from government) that many of our worries were addressed by Honduran government regulations that do apply to the ZEDEs. For example, he stated that the Honduran minimum wage (currently ranging from $1.94 US to $2.77 US per hour in manufacturing depending on the number of workers) applied to Prὀspera, so workers could not receive egregiously low payment. (He also claimed that Prὀspera’s charter requires payment 10% above the minimum wage.) Finally, he stated that if no other law or regulation applied to a business or industry, the prevailing standard would be “common law” enforced by the arbitrators, so the absence of firm written laws or rules should not be troubling.

A final guarantor of fairness is the fact that businesses operating in Prὀspera have to have insurance, he claimed. Since insurance companies do not like to make big payouts, they will protect worker rights, the environment, and the like, by refusing to insure companies taking shortcuts in these and other areas. (I found this claim to be especially ludicrous given the track record of U.S. medical insurance companies that raise their premium rates if they have to make a big payout, rather than cancelling coverage or pushing a company to reduce risk.)

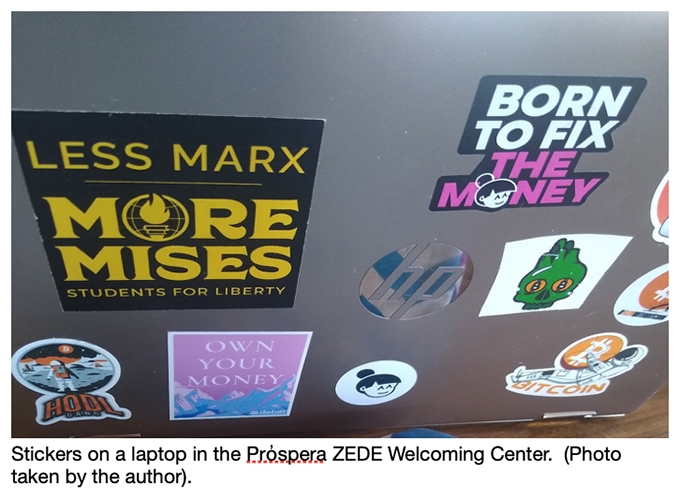

Wandering around the room where we were given the lecture by Colindres, I found some interesting things. One was a money changing machine to convert other currencies into bitcoin and vice versa. (I regret I did not get a picture of this machine.) Also interesting were posters and books for sale that were inside bookcases. For example, here are some stickers photographed from one of the laptop computers sitting around the room:

Note the many stickers boosting bitcoin currency as well as the “Less Marx, More Mises” sticker. Karl Marx is of course well known; the “Mises” refers to Ludwig Von Mises, the libertarian Austrian American thinker who argued that any governmental intervention in the economy would inevitably be for the worse.

The books for sale that were inside wall cabinets were also interesting. I’ll start with two children’s books which are take-offs from well-known children’s books in the U.S.:

Goodnight Bitcoin imitates one of the best-known children’s books of all time: Goodnight Moon. If you Give a Monster a Bitcoin emulates the beloved children’s book If You Give a Mouse a Cookie. I guess it’s never too early to begin inculcating into the mind of a child the individualist libertarian mindset necessary to make a currency free from any government seem plausible.

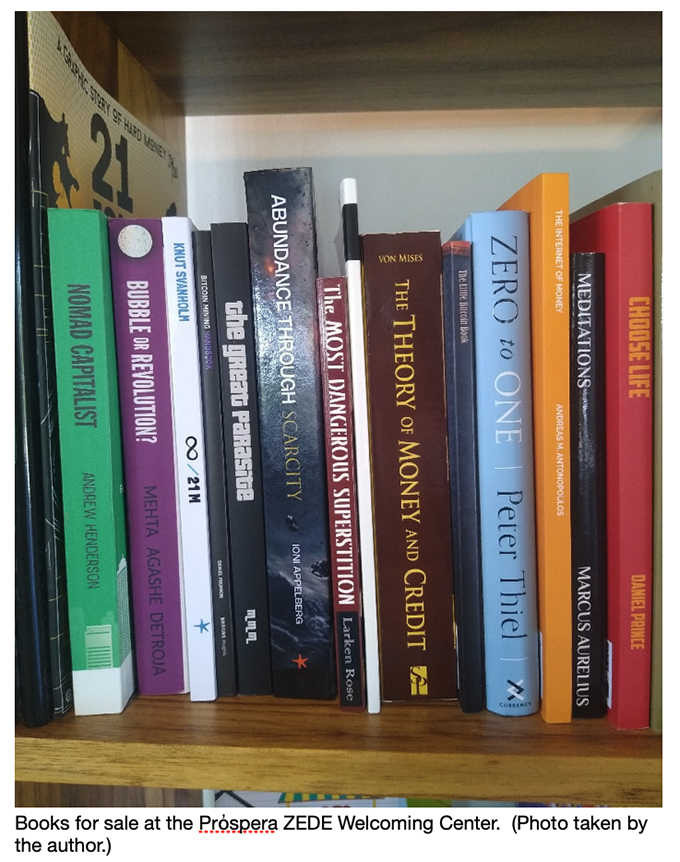

Then we come to the adult books. As you might suspect, they were all right-wing libertarian tracts. Here are a few pictures:

Note especially both the foundational book of this type, Von Mises’ The Theory of Money and Credit and a very recent book by modern billionaire and well-known anti-government crank Peter Thiel, Zero to One.

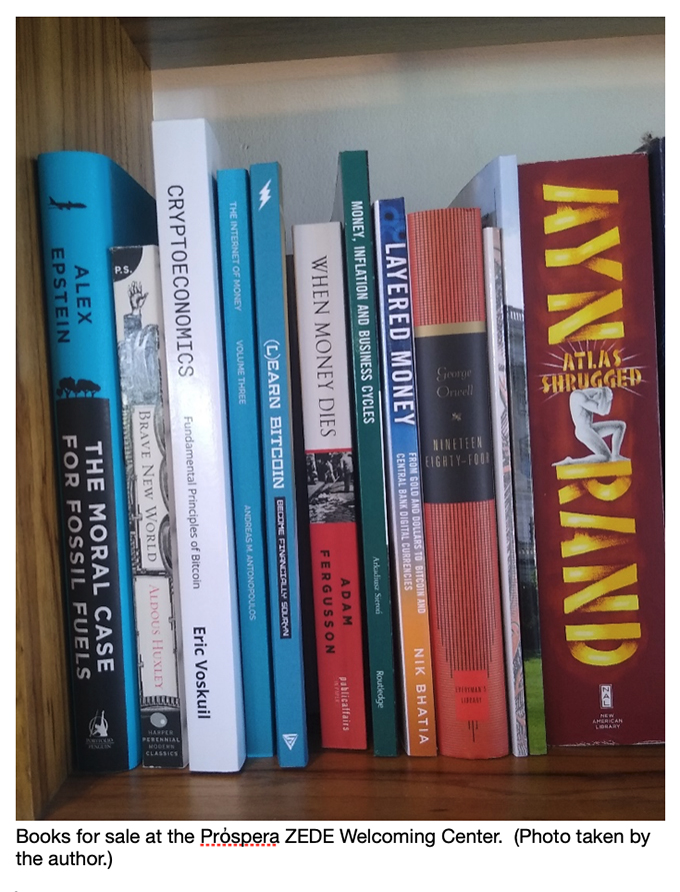

One more picture gives you the flavor of the books favored by and hawked by the Prὀspera ZEDE:

I had to include this picture because it shows perhaps the most famous individualist/libertarian book of all time: Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged. This book has sold many millions and is still selling briskly 70 years after it was published. I also found the title of the book on the far left to be astounding: making a moral case for maintaining fossil fuels.

Our delegation’s trip into the libertarian paradise came at a time when it was in peril, as it still is. This is the subject of the next section.

NEW GOVERNMENT FOLLOWING A GENUINE ELECTION MOVES TO ELIMINATE ZEDES

As noted previously, a reform government led by former first lady Xiomara Castro took power in January 2022 after a November 2021 election. Castro immediately reversed the trajectory of her conservative predecessors. She stopped a wealthy landowner from evicting indigenous people from land south of the capital, citing indigenous rights. She banned new open pit mining to protect the environment, introduced reforms to the tax system that close tax loopholes for the very richest (these tax reforms have not yet passed Congress), made electricity free to the poorest residents who used small amounts of it by billing the biggest users, and took other measures favoring those less well off.

In May 2022 she presented to the Honduran Congress legislation abolishing the ZEDE law. It passed unanimously, with parties from the left, right, and center all supporting it. This move was immensely popular in the country; mass demonstrations had been held opposing the existence of ZEDEs.

Amnesty International of the Americas lauded Castro’s move because they asserted that ZEDEs threatened the human rights of Honduran residents. But Honduras Prὀspera Inc. immediately filed a charge against Castro’s government with the International Centre for the Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), a business-oriented arbitration mechanism set up by the World Bank to protect foreign investors as an Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) mechanism for cases like this. They demanded $10.8 billion for the estimated loss of expected future profits from the Prὀspera ZEDE. That amount equals approximately two-thirds of Honduras’s annual state budget; it would cripple the country if the plaintiffs should prevail.

Two treaties with the United States commit Honduras to use this ISDS arbitration system to settle disputes with investors: the Dominican /Republic-Central America Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR) and a U.S.-Honduras Bilateral Investment Treaty (BIT). Castro had declared in her campaign that Honduras would withdraw from these two treaties, but the government has not left either CAFTA or BIT to date. She resisted sending a government representative to the arbitration proceedings that were set up to hear the Prὀspera claim before the ICSID. But eventually she was forced to send a lawyer to the proceedings to represent Honduras. This lawyer argued that private companies had to exhaust national legal remedies before coming to the ICSID tribunal, but this argument has not been accepted.

Eighty-five prominent international economists signed a letter in support of Castro’s move to withdraw from the ICSID, stating,

We economists from institutions across the world welcome the decision by the Honduran government to withdraw from the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID). We view the withdrawal as a critical defence of Honduran democracy and an important step toward its sustainable development.

U.S. politicians have weighed in on both sides of the dispute. Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-Massachusetts) and U.S. Representative Lloyd Doggett (D-Texas) rallied over 30 Congressmen to write U.S. Secretary of State Anthony Blinken asking that he intervene on the anti-ZEDE side. U.S. Senators Bill Haggerty (R-Tennessee) and Ben Cardin (D-Maryland) asked Blinken to do the exact opposite.

Legally the case is tangled and murky: Can Castro unilaterally (without congressional authorization) pull out of these treaties? Can the Prὀspera ZEDE lock in its own existence because it signed a 50-year treaty with Singapore while existing Honduran law guarantees protection of such treaties for a decade? While new ZEDEs are clearly illegal since the ZEDE law was rescinded, can existing ZEDEs also be eliminated retroactively? Answers to these questions are ambiguous at the present time.

Even more important, where does the U.S. government stand on the issue? Since the U.S. has almost-complete hegemony over what happens in a small and poor Central American country like Honduras, where it stands is crucially important. The Biden regime has talked out of both sides of its mouth. Former president Biden fulminated against Investor-State Dispute Settlements (ISDSs) and vowed to not include them in any future trade agreements. In contrast, Laura Dogu, the U.S. ambassador to Honduras, has strongly endorsed ZEDEs and Prὀspera in particular. She sharply criticized Xiomara Castro’s abolition of the ZEDE law, stating that such “actions are sending a clear message to companies that they should invest elsewhere, not in Honduras.” The U.S. State Department issued a similar statement, criticizing Honduras for having an uncertain “commitment to investment protections required by international treaties.”

WHAT IS THE LESSON FROM PROSPERA? WHAT CAN WE DO?

Rightwing libertarians around the world are attempting to erode and virtually erase governmental measures that protect both people and the environment from corporate misconduct and unrestrained capitalism. Thus, the most important lesson we can learn from the Prὀspera case is that we must remain vigilant worldwide.

To fight the good fight only domestically is to leave us all more vulnerable on a worldwide scale to a dystopian future of unrestrained selfishness, ever-growing inequality, and the consequent authoritarianism and militarism needed to hold down the subject peoples and to keep them from emigrating to wealthier countries like the U.S. In addition, Honduras and similar countries are laboratories for what might be done domestically in the future. This battle must be fought especially sharply in those areas of the world most lacking in resources needed to fight for and sustain a more humane cooperative and people-oriented society. Places like Honduras.

Here in the United States an urgent need is to demand that the administration not only vow to keep ISDS measures out of all future trade agreements (as the President has pledged to do) but take them out of all existing trade agreements. Fortunately, there is already action being taken by citizen groups and members of Congress to do just that. This move could use our help.

Congressmembers Linda T. Sanchez (D-California) and Lloyd Doggett (D-Texas) have marshalled 47 members of the House of Representatives to sign a letter to Secretary of State Anthony Blinken and U.S. Trade Representative Katherine Tai demanding that ISDS measures be taken out of CAFTA-DR and other such economic and trade agreements. This letter has been endorsed by Public Citizen, AFL-CIO, Greenpeace, Sierra Club, Pride at Work, Unitarian Universalists for a Just Economic Community, Honduras Solidarity Network, Oxfam America, Progressive Democrats of America, and a number of other groups.

We can aid this cause. If your Congressperson in the House has not signed on to this letter, we can pressure them to do so. If they have signed it, we can thank them for doing so and also write to our Senators to demand that they also sign on to this or an identical letter in the Senate. We can also ask the organizations we know and are affiliated with to endorse this letter, get their members to publicize it and contact their congresspersons, and so on.

Here are the materials you need to take action:

- First, you can go to the webpage that explains the issue and contains the letter: https://lindasanchez.house.gov/media-center/press-releases/sanchez-doggett-call-biden-administration-reform-cafta-dr-trade

- Second, you can download, circulate and publicize the letter itself, which is at this link: https://lindasanchez.house.gov/sites/evo-subsites/lindasanchez.house.gov/files/evo-media-document/ISDS%20Letter.pdf

- Finally, publicize all of this on social media!

I’m enclosing the entire letter below (minus the 47 Congressional signatories), just for those who lack online access and are only able to read from paper copies.

March 21, 2024

The Honorable Anthony Blinken The Honorable Katherine Tai

Secretary of State U.S. Trade Representative

Department of State Office of the U.S. Trade Representative

2201 C Street N.W. 600 17th Street N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20520 Washington, D.C. 20508

Dear Secretary Blinken and Ambassador Tai,

We commend the administration’s commitment to a “worker-centered” trade agenda that uplifts people in the United States and around the world and helps promote our humanitarian and foreign policy goals. We particularly appreciate President Biden’s opposition to including investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) mechanisms in trade and investment agreements, which enable foreign companies to sue the U.S. and our trading partners through international arbitration.

On a bipartisan basis, Congress drastically reduced ISDS liability from the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) because ISDS incentivizes offshoring, fuels a global race to the bottom for worker and environmental protections, and undermines the sovereignty of democratic governments. However, the U.S. has more than 50 existing trade and investment agreements on the books, most containing ISDS, including the U.S.-Central America Dominican Republic Agreement (CAFTA-DR) which entered into force in 2006. We urge you to offer CAFTA-DR governments the opportunity to work with the U.S. government to remove CAFTA-DR’s ISDS mechanism.

While there is no evidence that ISDS significantly promotes foreign direct investment, there is ample evidence that the abuse of the ISDS process harmed the Central America and Caribbean region. Multinational corporations have used ISDS to demand compensation for policies instituted by governments in CAFTA countries, undermining their democratic sovereignty and, often, harming the public good. For example, foreign companies have targeted labor rights, environmental protection, and public health policies.This ultimately works to counteract U.S. government assistance intended to address the root causes of migration from the region.

For certain Central American and Caribbean countries, even a single ISDS award (with some claims in the hundreds of millions or billions of dollars) could destabilize their economy, as limited fiscal revenues are diverted from critical domestic priorities to cover legal defense expenses, tribunal costs and damages. According to public sources, taxpayers in CAFTA-DR countries paid at least $58.9 million to foreign corporations in ISDS awards, with at least $14.5 billionin pending ISDS claims.Notably, the lack oftransparency in ISDS arbitration makes it impossible to know the full extent of ISDS liability. There are also concerns regarding the fairness of ISDS proceedings as ISDS arbitrators can appear as counsel before tribunals composed of arbitrators with whom they previously served in different ISDS proceedings.

Accordingly, we are eager to work with you to remove ISDS liability from CAFTA-DR and all other trade or investment agreements with countries in Central America and the Caribbean. This would send a powerful signal that the U.S. government is committed to a new model of partnership in the region — a model that uplifts and protects democracy, rule of law, human rights, and the environment. We look forward to working alongside you to bring the CAFTA-DR more into alignment with the current trade agenda and prevent harmful corporate overreach in emerging economies.

#

Special thanks to Judy Ancel and Karen Spring for judicious edits and corrections on earlier versions of this article.

###

Excellent, detailed informative article about the dangers of Zedes for the workers of Honduras.

There seems to be no end to the clever way capitalism and corporations can harm workers..