The Black Freedom Movement and Tradeswomen History

By Molly Martin

I want to take us back in time and imagine a world, a culture, in which job categories were firmly divided between MEN and WOMEN. Women were restricted to pink collar jobs that paid too little to raise a family on or even to live without a man’s support. Even doing the same jobs, women were legally paid less than men. Married women were not allowed to work outside the home. Single women who found jobs as teachers or secretaries were fired as soon as they married. Black people were only allowed to work as laborers or house cleaners.

This was the world we fought to change.

Tradeswomen who have jobs today must thank Black workers who began the fight for jobs and justice.

The Black Freedom Movement has advocated for workplace equity since the end of the Civil War.

The movement gained power during and after WWII. A. Philip Randolph headed the sleeping car porters union, the leading Black trade union in the US. In 1940 he threatened to march on Washington with ten thousand demonstrators if the government did not act to end job discrimination in federal war contracts. FDR capitulated and signed executive order 8802, the first presidential order to benefit Blacks since reconstruction. It outlawed discrimination by companies and unions engaged in war work on government contracts. This executive order marked the start of affirmative action.

The fight to desegregate the workforce continued.

In the early 1960s in the San Francisco Bay Area, protesters organized successful picket campaigns against businesses that refused to hire Blacks, including the Palace hotel, car dealerships and Mel’s Drive-In. Many of the protesters were white students at UC Berkeley.

In August 1963, the march on Washington brought 200,000 people to the capitol to protest racial discrimination and show support for civil rights legislation. The civil rights act of 1964, signed into law by President Johnson, is the legal structure that women and POC have used to put nondiscrimination into practice.

But change did not come quickly or easily.

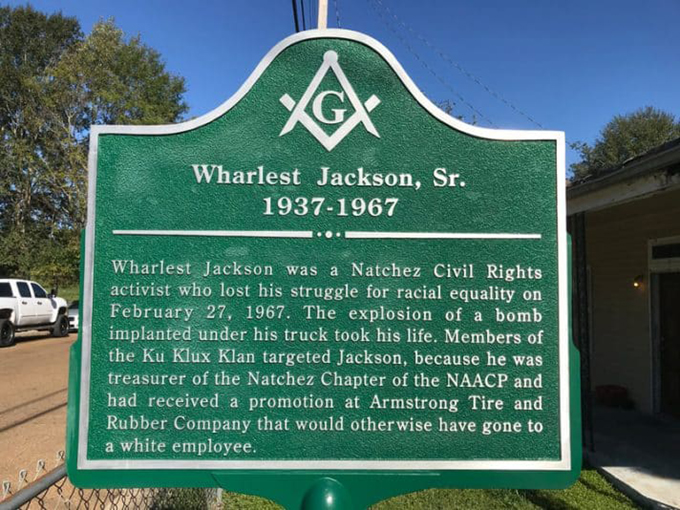

Black workers at a tire plant in Natchez Mississippi were organizing to desegregate jobs. The CIO, Congress of Industrial Organizations, supported them in this fight. In 1967, three years after the civil rights act became law, a Black man, Wharlest Jackson, who had won a promotion to a previously “white” job in the tire plant, was murdered by the KKK. They blew up his truck as he was driving home from work. No one was ever arrested or prosecuted for this crime.

Wharlest Jackson was the father of five. His wife, Exerlina, was among those arrested for peacefully insisting on equal treatment during a boycott of the town of Natchez’s white businesses. She was sent to Parchman penitentiary.

Jackson was just one of many who died for our right to be treated equally at work.

Tradeswomen are part of the feminist, civil rights and union movements. We continue to seek allies because we are few.

Discrimination has not ended, but, because of decades of organizing, our work lives have improved. We owe much to the Black workers who sought equity in employment for decades before us.

…